Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

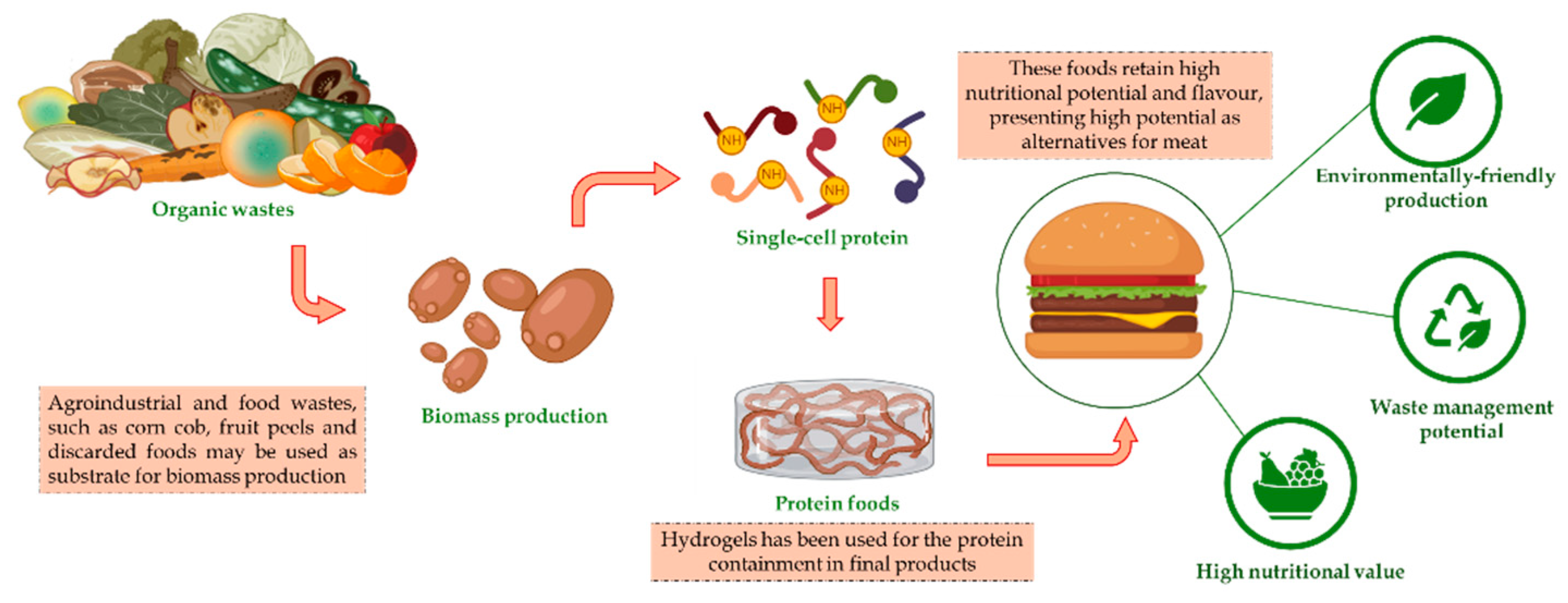

2. Alternative to Meat Proteins

3. Biotechnological Configurations and Processes for Protein Production

3.1. Fermentation Processes for Single-Cell Protein Production

| Microorganism | Bioreactor | Substrate | Volume (L) | Protein production | Temperature (°C) | pH | Stirring (rpm) | Oxygenation | Time | References |

| Methylococcus capsulatus MIR | Bioreactor | Methane | 1.5 | 4.72 g/L | 42 | 6.3 | 1000 | 18000 cm³ de ar/h | 10-14 days | [53] |

| Methylococcus capsulatus | Fixed-film anaerobic digester | Biological waste | 17.5 | 52% (w/w) | 45 | 7.0-8.0 | - | 0% | 12.25 days | [54] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Bioreactor | Food waste | 15 | 2.2 g/mL | - | 3.0-3.5 | - | - | 4 days | [55] |

| Fusarium venenatum KACC | Pressure cycle reactor | Malt extract broth | 150.000 | 300-350 kg biomass/h | 28-30 | 6.0 | - | - | Continuous | [56,57] |

| Fusarium venenatum | Stirred bioreactor | Glucose | 3.5 | 9.53 g/L | 28 | 6.0 | 100 up to 300 | 1 vvm | 72 h | [58] |

| Fusarium venenatum IR372C | Laboratory bioreactor | Modified date syrup in Vogel medium | 3.0 | 55% (w/w) | 28 | 5.6 | 400 | 1 vvm | 72 h | [59] |

| Fusarium venenatum CGMCC | Stirred bioreactor | Glucose | 3.7 | 10.2 g/L (61,9 %, m/m) | 29 | 6.0 | 100 up to 300 | 1 vvm | 48 h | [60] |

| Chlorella sorokiniana GT-1 | Pilot fermenter | Glucose | 1000 | 73.5 g/L/d | 30 | 6.0 | 180 | DO = 20% | 6 days | [61] |

| Spirulina platensis | Photobioreactor | Beet sugar extraction cake | 0.4 | 0.56 g/L (52.5%, m/m) | 26 | 8.0 | - | - | 7 days | [62] |

3.2. Application of Enzymes to Obtain Protein Compounds

3. Biotechnological Configurations and Processes for Protein Production

4.1. Production of SCP from Sludge and Organic Waste

4.2. Production of SCP from Industrial Effluents

4.3. Production of SCP from Plant Residues

4.3. Production of SCP from Food Waste

5. Technological, Regulatory, and Consumer Acceptance Challenges Regarding Non-Meat Proteins

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cavaliere, V.N.; Mindiola, D.J. Methane: A New Frontier in Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačėninaitė, D.; Džermeikaitė, K.; Antanaitis, R. Global Warming and Dairy Cattle: How to Control and Reduce Methane Emission. Animals 2022, 12, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, I.A.; Valappil, G.; Dutta, B.; Imbeault-Tétreault, H.; Ominski, K.H.; Cordeiro, M.R.C.; Kröbel, R.; Pogue, S.J.; McAllister, T.A. An Assessment of the Environmental Sustainability of Beef Production in Canada. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 104, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, H.; Whaley, J.E.; Kim, Y.K. Do Consumers Perceive Cultivated Meat as a Sustainable Substitute to Conventional Meat? Assessing the Facilitators and Inhibitors of Cultivated Meat Acceptance. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Osorio, P.D.; Ramírez-Mejía, J.M.; Mejía-Avellaneda, L.F.; Mesa, L.; Bautista, E.J. Agro-Industrial Residues for Microbial Bioproducts: A Key Booster for Bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2022, 20, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Almeida, A.P.; Infante Neta, A.A.; de Andrade-Lima, M.; de Albuquerque, T.L. Plant-Based Probiotic Foods: Current State and Future Trends. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, T.; Mattila, A.S. The Impact of Environmental Messages on Consumer Responses to Plant-Based Meat: Does Language Style Matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Liu, S.; Gao, L.; Hong, K.; Liu, S.; Wu, X. Economical Production of Pichia Pastoris Single Cell Protein from Methanol at Industrial Pilot Scale. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Qi, H. Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Heterologous Protein Production by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, X.; Yin, Y. Synthetic Biology-Driven Customization of Functional Feed Resources. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühl, S.; Schäfer, A.; Kircher, C.; Mehlhose, C. Beyond the Cow: Consumer Perceptions and Information Impact on Acceptance of Precision Fermentation-Produced Cheese in Germany. Futur. Foods 2024, 10, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsuk, N.; Laohakunjit, N.; Sanporkha, P.; Kaisangsri, N.; Selamassakul, O.; Ratanakhanokchai, K.; Uthairatanakij, A.; Waeonukul, R. Comparative Physicochemical Characteristics and in Vitro Protein Digestibility of Alginate/Calcium Salt Restructured Pork Steak Hydrolyzed with Bromelain and Addition of Various Hydrocolloids (Low Acyl Gellan, Low Methoxy Pectin and κ-Carrageenan). Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang-O’Dwyer, M.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pulse Proteins as a Tool to Improve Techno-Functional Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, G.; Goksen, G.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Plant-Based Protein Modification Strategies towards Challenges. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Maloney, K.; Drake, M.; Zheng, H. Synergistic Functionality of Transglutaminase and Protease on Modulating Texture of Pea Protein Based Yogurt Alternative: From Rheological and Tribological Characterizations to Sensory Perception. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, M.; Trusinska, M.; Chraniuk, P.; Drudi, F.; Lukasiewicz, J.; Nguyen, N.P.; Przybyszewska, A.; Pobiega, K.; Tappi, S.; Tylewicz, U.; et al. Developments in Plant Proteins Production for Meat and Fish Analogues. Molecules 2023, 28, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, E.A.; Shaw, R.E.; Reynolds, C.R. Prediction of Strain Engineerings That Amplify Recombinant Protein Secretion through the Machine Learning Approach MaLPHAS. Eng. Biol. 2022, 6, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinestock, T.; Short, M.; Ward, K.; Guo, M. Computer-Aided Chemical Engineering Research Advances in Precision Fermentation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2024, 58, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F.; Ganeshan, S.; Wang, Y.; Tülbek, M.Ç.; Nickerson, M.T. Bioengineered Enzymes and Precision Fermentation in the Food Industry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colarusso, A. V.; Goodchild-Michelman, I.; Rayle, M.; Zomorrodi, A.R. Computational Modeling of Metabolism in Microbial Communities on a Genome-Scale. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2021, 26, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, J.; Brightwell, G. Safety of Alternative Proteins: Technological, Environmental and Regulatory Aspects of Cultured Meat, Plant-Based Meat, Insect Protein and Single-Cell Protein. Foods 2021, 10, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyola-Altamirano, B.; Méndez-Lagunas, L.L.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Sandoval-Torres, S.; Aquino-González, L.V.; Barriada-Bernal, L.G. Techno-Functional Properties and Antioxidant Capacity of the Concentrate and Protein Fractions of Leucaena Spp. Seeds. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2022, 72, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famuwagun, A.A.; Alashi, A.M.; Gbadamosi, S.O.; Taiwo, K.A.; Oyedele, D.J.; Adebooye, O.C.; Aluko, R.E. Comparative Study of the Structural and Functional Properties of Protein Isolates Prepared from Edible Vegetable Leaves. Int. J. Food Prop. 2020, 23, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.-H.; Green-Johnson, J.M.; Buckley, N.D.; Lin, Q.-Y. Bioactivity of Soy-Based Fermented Foods: A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Consalvo, S.; Esposito, C.; Tammaro, D. Tailoring Texture and Functionality of Vegetable Protein Meat Analogues through 3D Printed Porous Structures. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 159, 110611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.; Brauer, P.; Yi, S. Meat Reduction among Post-Secondary Students: Exploration of Motives, Barriers, Diets and Preferences for Meals with Partial and Full Meat Substitution. Appetite 2023, 188, 106977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, J. V.; Nugent, A.P.; Moore, R.E.; McKinley, M.C. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption as a Preventative Strategy for Non-Communicable Diseases. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A.; Rumpold, B.A.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Tomberlin, J.K. Advancing Edible Insects as Food and Feed in a Circular Economy. J. Insects as Food Feed 2021, 7, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Baró, M.; Sánchez-Socarrás, V.; Santos-Pagès, M.; Bach-Faig, A.; Aguilar-Martínez, A. Consumers’ Acceptability and Perception of Edible Insects as an Emerging Protein Source. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Navia, D.M.; Dueñas-Rivadeneira, A.A.; Dueñas-Rivadeneira, J.P.; Aransiola, S.A.; Maddela, N.R.; Prasad, R. Bioactive Compounds of Insects for Food Use: Potentialities and Risks. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejczyk, B.; Łobacz, A.; Ziajka, J.; Lis, A.; Małkowska-Kowalczyk, M. Comprehensive Analysis of Yoghurt Made with the Addition of Yellow Mealworm Powder (Tenebrio Molitor). Foods 2024, 13, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwinkels, J.; Wolkers-Rooijackers, J.; Smid, E.J. Solid-State Fungal Fermentation Transforms Low-Quality Plant-Based Foods into Products with Improved Protein Quality. Lwt 2023, 184, 114979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R. ichiro; Sakaguchi, K.; Yoshida, A.; Takahashi, H.; Shimizu, T. Efficient Expansion Culture of Bovine Myogenic Cells with Differentiation Capacity Using Muscle Extract-Supplemented Medium. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhu, X.; Sun, R.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Sun, B. Sensory Attributes and Characterization of Aroma Profiles of Fermented Sausages Based on Fibrous-like Meat Substitute from Soybean Protein and Coprinus Comatus. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaibam, B.; da Silva, M.F.; de Mélo, A.H.F.; Carvalho, P.H.; Galland, F.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Goldbeck, R. Non-Animal Protein Hydrolysates from Agro-Industrial Wastes: A Prospect of Alternative Inputs for Cultured Meat. Food Chem. 2024, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedeli, R.; Mazza, I.; Perini, C.; Salerni, E.; Loppi, S. New Frontiers in the Cultivation of Edible Fungi: The Application of Biostimulants Enhances the Nutritional Characteristics of Pleurotus Eryngii (DC.) Quél. Agric. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gómez, L.M.; Molina-Gilarranz, I.; Fontes-Candia, C.; Cebrián-Lloret, V.; Recio, I.; Martínez-Sanz, M. Production of Hybrid Protein-Polysaccharide Extracts from Ulva Spp. Seaweed with Potential as Food Ingredients. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, F.; Khandi, S.A.; Aadil, R.M.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A.; Abdi, G.; Bhat, Z.F. What Do Meat Scientists Think about Cultured Meat? Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, J.; Vasas, D.; Kalocsai, R.; Szakál, T.; Ahmed, M.H. Production of Single Cell Protein by the Fermentation Biotechnology for Animal Feeding. Elelmiszervizsgalati Kozlemenyek 2022, 68, 3896–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.I.; Asif, M.; Razzaq, Z.U.; Nazir, A.; Maan, A.A. Sustainable Food Industrial Waste Management through Single Cell Protein Production and Characterization of Protein Enriched Bread. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hu, W.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y. Valorization of Food Waste Fermentation Liquid into Single Cell Protein by Photosynthetic Bacteria via Stimulating Carbon Metabolic Pathway and Environmental Behaviour. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertasini, D.; Binati, R.L.; Bolzonella, D.; Battista, F. Single Cell Proteins Production from Food Processing Effluents and Digestate. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 134076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Valadares, A.C.F.; de Almeida, A.B.; Valencia-Mejia, E.; Fernandes, K.F.; Lemes, A.C.; Alves, C.C.F.; Sousa, H.A. de F.; da Silva, E.R.; et al. Bioactive Properties of Protein Hydrolysate of Cottonseed Byproduct: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Activities. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopplin, B.W.; Bernardo, B. da S.; Moraes, G.P.; Goettems, T.L.; Clerici, N.J.; Lermen, A.M.; Daroit, D.J. Production of Antioxidant Hydrolysates from Bovine Caseinate and Soy Protein Using Three Non-Commercial Bacterial Proteases. Biocatal. Biotransformation 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhodko, D. V.; Krasnoshtanova, A.A. Using Casein and Gluten Protein Fractions to Obtain Functional Ingredients. Foods Raw Mater. 2023, 11, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Peteghem, L.; Sakarika, M.; Matassa, S.; Rabaey, K. The Role of Microorganisms and Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratios for Microbial Protein Production from Bioethanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezarjaribi, M.; Ardestani, F.; Ghorbani, H.R. Single Cell Protein Production by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Using an Optimized Culture Medium Composition in a Batch Submerged Bioprocess. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 179, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, X.; Su, Y.; Angelidaki, I.; Zhang, Y. Biogas Upgrading and Valorization to Single-Cell Protein in a Bioinorganic Electrosynthesis System. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knychala, M.M.; Boing, L.A.; Ienczak, J.L.; Trichez, D.; Stambuk, B.U. Precision Fermentation as an Alternative to Animal Protein, a Review. Fermentation 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsing, F.; Sullivan, R.; Truong, H.; Rombenso, A.; Sangster, C.R.; Bannister, J.; Longshaw, M.; Becker, J.A. Replacement of Fishmeal with a Microbial Single-Cell Protein Induced Enteropathy and Poor Growth Outcomes in Barramundi (Lates Calcarifer) Fry. J. Fish Dis. 2024, 47, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.Y.; Kee, P.E.; Abdullah, R.; Lan, J.C.; Ling, T.C.; Jiang, J.; Lim, J.W.; Khoo, K.S. Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass Waste into Mycoprotein : Current Status and Future Directions for Sustainable Protein Production. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutilainen, E.; Pihlajaniemi, V.; Parviainen, T. Economic Comparison of Food Protein Production with Single-Cell Organisms from Lignocellulose Side-Streams. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2021, 14, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- But, S.Y.; Suleimanov, R.Z.; Oshkin, I.Y.; Rozova, O.N.; Mustakhimov, I.I.; Pimenov, N. V.; Dedysh, S.N.; Khmelenina, V.N. New Solutions in Single-Cell Protein Production from Methane: Construction of Glycogen-Deficient Mutants of Methylococcus Capsulatus MIR. Fermentation 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.M.; Kronyak, R.E.; House, C.H. Coupling of Anaerobic Waste Treatment to Produce Protein- and Lipid-Rich Bacterial Biomass. Life Sci. Sp. Res. 2017, 15, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervasi, T.; Pellizzeri, V.; Calabrese, G.; Di Bella, G.; Cicero, N.; Dugo, G. Production of Single Cell Protein (SCP) from Food and Agricultural Waste by Using Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Kang, A.N.; Lee, J.; Kwak, M.; Mun, D.; Lee, D.; Oh, S.; Kim, Y. Molecular Characterization of Fusarium Venenatum- Based Microbial Protein in Animal Models of Obesity Using Multi-Omics Analysis. 2024, 7, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, M.G. Myco-Protein from Fusarium Venenatum : A Well-Established Product for Human Consumption. 2002, 2684, 421–427. [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Hong, R.; Chen, W.; Chai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, D. Synchronous Bioproduction of Betanin and Mycoprotein in the Engineered Edible Fungus Fusarium Venenatum. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hashempour-Baltork, F.; Hosseini, S.M.; Assarehzadegan, M.A.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Hosseini, H. Safety Assays and Nutritional Values of Mycoprotein Produced by Fusarium Venenatum IR372C from Date Waste as Substrate. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4433–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.; Chen, W.; Hong, R.; Chai, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, D. Efficient Mycoprotein Production with Low CO 2 Emissions through Metabolic Engineering and Fermentation Optimization of Fusarium Venenatum. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Chuai, W.; Li, K.; Hou, G.; Wu, M.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Jia, J.; Han, D.; Hu, Q. Ultrahigh-Cell-Density Heterotrophic Cultivation of the Unicellular Green Alga Chlorella Sorokiniana for Biomass Production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 4138–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.; Hussien, M.H.; Abou-ElWafa, G.S.; Aldesuquy, H.S.; Eltanahy, E. Filter Cake Extract from the Beet Sugar Industry as an Economic Growth Medium for the Production of Spirulina Platensis as a Microbial Cell Factory for Protein. Microb. Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gome, G.; Chak, B.; Tawil, S.; Shpatz, D.; Giron, J.; Brajzblat, I.; Weizman, C.; Grishko, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Shoseyov, O. Cultivation of Bovine Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Plant-Based Scaffolds in a Macrofluidic Single-Use Bioreactor for Cultured Meat. Foods 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Kermani, A.S.; Huynh, M.J.; Baar, K.; Leach, J.K.; Block, D.E. Edible Mycelium as Proliferation and Differentiation Support for Anchorage-Dependent Animal Cells in Cultivated Meat Production. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirvaresi, A.; Ovissipour, R. Evaluation of Plant- and Microbial-Derived Protein Hydrolysates as Substitutes for Fetal Bovine Serum in Cultivated Seafood Cell Culture Media. bioRxiv 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikandari, R.; Tanugraha, D.R.; Yastanto, A.J.; Manikharda; Gmoser, R. ; Teixeira, J.A. Development of Meat Substitutes from Filamentous Fungi Cultivated on Residual Water of Tempeh Factories. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanillas, B.; Pedrosa, M.M.; Rodríguez, J.; Muzquiz, M.; Maleki, S.J.; Cuadrado, C.; Burbano, C.; Crespo, J.F. Influence of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Allergenicity of Roasted Peanut Protein Extract. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 157, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaibam, B.; Goldbeck, R. Effects of Enzymes on Protein Extraction and Post-Extraction Hydrolysis of Non-Animal Agro-Industrial Wastes to Obtain Inputs for Cultured Meat. Food Bioprod. Process. 2024, 143, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batish, I.; Brits, D.; Valencia, P.; Miyai, C.; Rafeeq, S.; Xu, Y.; Galanopoulos, M.; Sismour, E.; Ovissipour, R. Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Functional Properties, Antioxidant Activity and Protein Structure of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) Protein. Insects 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaibam, B.; Goldbeck, R. Food and Bioproducts Processing Effects of Enzymes on Protein Extraction and Post-Extraction Hydrolysis of Non-Animal Agro-Industrial Wastes to Obtain Inputs for Cultured Meat. 2024, 143, 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, L.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, H. Structure Characterization and Bioactivities of Protein Hydrolysates of Chia Seed Expeller Processed with Different Proteases in Silico and in Vitro. Food Biosci. 2023, 55, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumby, N.; Zhong, Y.; Naczk, M.; Shahidi, F. Antioxidant Activity and Water-Holding Capacity of Canola Protein Hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinlschmidt, P.; Sussmann, D.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P. Enzymatic Treatment of Soy Protein Isolates: Effects on the Potential Allergenicity, Technofunctionality, and Sensory Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhou, H.; Qian, H. Enzymatic Preparation and Functional Properties of Wheat Gluten Hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, A.; Vioque, J.; Sánchez-Vioque, R.; Pedroche, J.; Bautista, J.; Millán, F. Protein Quality of Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L.) Protein Hydrolysates. Food Chem. 1999, 67, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaštag, Ž.; Popović, L.; Popović, S.; Krimer, V.; Peričin, D. Production of Enzymatic Hydrolysates with Antioxidant and Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity from Pumpkin Oil Cake Protein Isolate. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Mohtar, W.A.A.-Q.I.; Hamid, A.A.; Abd-Aziz, S.; Muhamad, S.K.S.; Saari, N. Preparation of Bioactive Peptides with High Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity from Winged Bean [Psophocarpus Tetragonolobus (L.) DC.] Seed. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsa, P.; Yuenyongrattanakorn, K.; Pongvachirint, W.; Auntalarok, A. Improving Anti-Hypertensive Properties of Plant-Based Alternatives to Yogurt Fortified with Rice Protein Hydrolysate. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokni Ghribi, A.; Maklouf Gafsi, I.; Sila, A.; Blecker, C.; Danthine, S.; Attia, H.; Bougatef, A.; Besbes, S. Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on Conformational and Functional Properties of Chickpea Protein Isolate. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yust, M. del M.; Pedroche, J.; Millán-Linares, M. del C.; Alcaide-Hidalgo, J.M.; Millán, F. Improvement of Functional Properties of Chickpea Proteins by Hydrolysis with Immobilised Alcalase. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgil, P.; Omar, L.S.; Kamal, H.; Kilari, B.P.; Maqsood, S. Multi-Functional Bioactive Properties of Intact and Enzymatically Hydrolysed Quinoa and Amaranth Proteins. LWT 2019, 110, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Mudgil, P.; Bhaskar, B.; Fisayo, A.F.; Gan, C.-Y.; Maqsood, S. Amaranth Proteins as Potential Source of Bioactive Peptides with Enhanced Inhibition of Enzymatic Markers Linked with Hypertension and Diabetes. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 101, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Z.; Logan, A.; Terry, S.; Spear, J.R. Microbial Response to Single-Cell Protein Production and Brewery Wastewater Treatment. Microb. Biotechnol. 2015, 8, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, L.; Dong, J.; Yang, Q. Production of Single-Cell Protein with Two-Step Fermentation for Treatment of Potato Starch Processing Waste. Cellulose 2014, 21, 3637–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Zhao, S.; He, M.; Hu, G.; Ge, X.; Peng, N. Single-Cell Protein and Xylitol Production by a Novel Yeast Strain Candida Intermedia FL023 from Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates and Xylose. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 185, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Tsapekos, P.; Zhu, X.; Khoshnevisan, B.; Lu, X.; Angelidaki, I. Bioconversion of Wastewater to Single Cell Protein by Methanotrophic Bacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwineza, C.; Sar, T.; Mahboubi, A.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Evaluation of the Cultivation of Aspergillus Oryzae on Organic Waste-Derived Vfa Effluents and Its Potential Application as Alternative Sustainable Nutrient Source for Animal Feed. Sustain. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnevisan, B.; Tsapekos, P.; Zhang, Y.; Valverde-Pérez, B.; Angelidaki, I. Urban Biowaste Valorization by Coupling Anaerobic Digestion and Single Cell Protein Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 290, 121743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Yin, H.; Lai, H.; Xiao, R.; He, S.; Yang, Z.; He, Y. Process Optimization, Amino Acid Composition, and Antioxidant Activities of Protein and Polypeptide Extracted from Waste Beer Yeast. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurcz, A.; Błażejak, S.; Kot, A.M.; Bzducha-Wróbel, A.; Kieliszek, M. Application of Industrial Wastes for the Production of Microbial Single-Cell Protein by Fodder Yeast Candida Utilis. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, H.M.A.; Asim, Z.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Abdelhadi, O.M.A.; Almomani, F.; Rasool, K. Optimizing Cultural Conditions and Pretreatment for High-Value Single-Cell Protein from Vegetable Waste. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 189, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rages, A.A.; Haider, M.M.; Aydin, M. Alkaline Hydrolysis of Olive Fruits Wastes for the Production of Single Cell Protein by Candida Lipolytica. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 33, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umesh, M.; Priyanka, K.; Thazeem, B.; Preethi, K. Production of Single Cell Protein and Polyhydroxyalkanoate from Carica Papaya Waste. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 2361–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.; Al-Qahtani, M.S.; Alamri, S.A.; Moustafa, Y.S.; Lyberatos, G.; Ntaikou, I. Valorizing Food Wastes: Assessment of Novel Yeast Strains for Enhanced Production of Single-Cell Protein from Wasted Date Molasses. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 4491–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornochalert, N.; Kantachote, D.; Chaiprapat, S.; Techkarnjanaruk, S. Use of Rhodopseudomonas Palustris P1 Stimulated Growth by Fermented Pineapple Extract to Treat Latex Rubber Sheet Wastewater to Obtain Single Cell Protein. Ann. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggelopoulos, T.; Katsieris, K.; Bekatorou, A.; Pandey, A.; Banat, I.M.; Koutinas, A.A. Solid State Fermentation of Food Waste Mixtures for Single Cell Protein, Aroma Volatiles and Fat Production. Food Chem. 2014, 145, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tropea, A.; Ferracane, A.; Albergamo, A.; Potortì, A.G.; Turco, V. Lo; Di Bella, G. Single Cell Protein Production through Multi Food-Waste Substrate Fermentation. Fermentation 2022, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.I.; Asif, M.; Razzaq, Z.U.; Nazir, A.; Maan, A.A. Sustainable Food Industrial Waste Management through Single Cell Protein Production and Characterization of Protein Enriched Bread. Food Biosci. 2022, 46, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Alireza, K. Methods and Systems of Preparing Cultivated Meat From Blood or Cellular Biomass 2022, 75.

- Bubner, P.; Daley, L.; Levesque-Tremblay, G. Using Organoids And/or Spheroids to Cultivate Meat 2024, 51.

- Reed, J.; Robertson, D.; Rao, K. STRUCTURED HIGH - PROTEIN MEAT ANALOGUE COMPOSITIONS 2021.

- Simpson, S.; Allen, W.E.; Conrado, R.J.; Molloy, S. GAS FERMENTATION FOR THE PRODUCTION OF PROTEIN OR FEED 2020.

- Macur, R.E.; Avniel, Y.C.; Black, R.U.; Hamilton, M.D.; Harney, M.J.; Eckstrom, E.B.; Kozubal, M.A. FOOD MATERIALS COMPRISING FILAMENTOUS FUNGAL PARTICLES AND MEMBRANE BIOREACTOR DESIGN 2024.

- Pearlman, P.S.; Rojas, H.F.C.; Smith, G.; Kirby, G.S. Nutritive Compositions and Methods Related Thereto 2022.

- Kragh, K.M.; Haaning, S.; Meihjohanns, E.; Degn, P.E.; Bak, S.Y.; Eisele, T. METHOD FOR PRODUCING A PROTEIN Publication Classification HYDROLYSATE EMPLOYING AN ASPERGILLUS FUMIGATUS TRIPEPTIDYL PEPTIDASE 2021.

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A Systematic Review on Consumer Acceptance of Alternative Proteins: Pulses, Algae, Insects, Plant-Based Meat Alternatives, and Cultured Meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, A.; Orkan, Ş.; Aral, Y.; İplikçioğlu Aral, G. A Comprehensive Outlook on Cultured Meat and Conventional Meat Production. Ankara Üniversitesi Vet. Fakültesi Derg. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hanan, F.A.; Karim, S.A.; Aziz, Y.A.; Ishak, F.A.C.; Sumarjan, N. Consumer’s Cultured Meat Perception and Acceptance Determinants: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, B.; Majoo, F.; Öztürkcan, A. Consumer Acceptance, Attitude and Knowledge Studies on Alternative Protein Sources: Insight Review. Gıda 2024, 49, 682–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild-Mancinelli, K.; Germann, S.M.; Andersen, M.R. Bottlenecks and Future Outlooks for High-Throughput Technologies for Filamentous Fungi; 2020; ISBN 9783030295400.

- Finnigan, T.J.A.; Wall, B.T.; Wilde, P.J.; Stephens, F.B.; Taylor, S.L.; Freedman, M.R. Mycoprotein: The Future of Nutritious Nonmeat Protein, a Symposium Review. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrate used | Protein type | Microorganism/Enzyme | Growing conditions | Sensory analysis | Ref. |

| Soy protein blend with Coprinus comatus powder, distilled water, cornstarch, sunflower oil, konjac flour, carrageenan, egg white powder, etc. | Soy and fungal protein | Coprinus comatus (edible fungi) | 30 °C, 70% relative humidity, for 18h in a fermentation room | Sensory evaluation with 29 participants. The product obtained good scores in texture, flavor, and odor, surpassing other variations processed with different starters | [34] |

| Basmati rice, pearled barley | Fungal (Aspergillus oryzae, Rhizopus microsporus) | Aspergillus oryzae, Rhizopus microsporus | Solid state fermentation, 28-30 °C, 7-10 days. | - | [32] |

| DMEM medium supplemented with Fetal Bovine Serum and penicillin-streptomycin | Fungal (single cell protein) + alginate fiber | Mycelium (fungi) + alginate fiber | Humidified medium with 5% CO2 at 37 °C | Made to simulate meat in a hybrid burger with texture and viability analysis | [33] |

| Soy flour, peanut flour, and residual brewer's yeast | Protein from agro-industrial waste | Alcalase 2.4L and Neutrase 0.8L | Enzymatic hydrolysis at 50 °C and 200 rpm | - | [35] |

| Agricultural waste: wheat straw, beet pulp | Pleurotus eryngii (edible fungi) | Pleurotus eryngii | Temperature of 26 °C for 60 days with 70% hydration | - | [36] |

| Biomass of Ulva spp. collected from the Atlantic Ocean | Algae protein | Proteins from Ulva spp. (green seaweed) | Application of ultrasonic pretreatment (5 min) followed by pH adjustment for protein solubilization and precipitation (pH 12 and 3, respectively | - | [37] |

| Enzyme | Source | Substrate | Pretreatment | Buffer | Conditions | Separation | Yield (%, w/w) | Reference |

| Alcalase | Bacillus licheniformis | Cottonseed meal | thermal pretreatment | 0.1 M TRIS-HCl | 55º C, pH 8.0 for 100 min | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 40.3-47.2% | [43] |

| Black soldier fly larvae | sodium hydroxide | - | 60 ºC and pH 6.85 | Centrifugation (2500 g for 5 min) | 51.4 | [69] | ||

| Soybean protein | - | 0.1 M TRIS-HCl | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, 200 rpm for 120 min | Centrifugation (5000 g for 20 min) | 22.44 | [70] | ||

| Peanut protein | - | 0.1 M TRIS-HCl | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, 200 rpm for 120 min | Centrifugation (5000 g for 20 min) | 16.44 | [70] | ||

| Chia seed expeller | Protein extraction by organic and enzymatic extraction | 45 ºC, pH 9.0 | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 15% | [71] | |||

| Canola protein | Grinding and hexane pretreatment | 50 ºC, pH 8.0 | Filtration |

20.6 | [72] | |||

| Soy protein | n-hexane extraction | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 13,0% | [73] | |||

| Wheat gluten protein | 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.5) | 60 ºC, pH 8,5, for 360 minutes | Centrifugation (10000 g for 20 minutes) | DH: 16% | [74] | |||

| Chickpea protein | 100 mM phosphate buffer | 50 ºC, pH 8.0 | Centrifugation (4000 g for 30 minutes) | DH: 27% | [75] | |||

| Protein isolate from pumpkin oil cake | Extraction with hexane | Tris/HCl 0,1 mol/L pH 8.00 | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, For 60 minutes |

- | DH: 53.3% | [76] | ||

| winged bean seed | Extraction with petroleum ether | 60 ºC, pH 8.0, for 300 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 20 minutes) | DH: 16.1% | [77] | |||

| rice protein | sodium citrate (pH 7.0) | 60 ºC, pH 7.0, for 180 minutes |

Centrifugation (15000 g for 15 minutes) | DH: 33.96%, |

[78] | |||

| chickpea protein | Extraction with hexane | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 210 minutes |

Centrifugation (5000 g for 20 minutes) | DH: 14.7% |

[79] | |||

| chickpea seed protein | Treatment with sodium sulphite | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 10,50,150 e 300 minutes |

Filtration | DH: 10% |

[80] | |||

| Alcalase + Flavourzyme | Bacillus licheniformis+ Aspergillus oryzae | Canola protein | Grinding and hexane pretreatment | 50 ºC, pH 7.0/8,0 | Filtration |

18.9% | [72] | |

| Chickpea protein | 100 mM phosphate buffer | 50 ºC, pH 8.0 e 50 ºC, pH 7.0 | Centrifugation (4000 g for 30 minutes) | DH: 52% | [75] | |||

| Protein isolate from pumpkin oil cake | Extraction with hexane | Tris/HCl 0,1 mol/L pH 8.00 | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, For 60 minutes |

- | DH: 53.2% | [76] | ||

| Flavourzyme | Aspergillus oryzae | Cottonseed meal | thermal pretreatment | 0.1 M phosphate buffer | 60 ºC, pH 7.0 for 100 min | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 27.2-27.5% | [43] |

| Chia seed expeller | Protein extraction by organic and enzymatic extraction | 50 ºC, pH 7.0 | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH:11% | [71] | |||

| Canola protein | Grinding and hexane pretreatment | 50 ºC, pH 7.0 | Filtration |

6.33 | [72] | |||

| Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 6.0, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | 8.5% | [73] | |||

| Chickpea protein | - | 100 mM phosphate buffer | 50 ºC, pH 7.0 | Centrifugation (4000 g for 30 minutes) | DH: 27% | [75] | ||

| Protein isolate from pumpkin oil cake | Extraction by hexane | Tris/HCl 0,1 mol/L pH 8,00 | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, For 60 minutes |

- | DH: 37.2% | [76] | ||

| Winged bean seed | Extraction by petroleum ether | 55 ºC, pH 8.0, for 300 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 20 minutes) | DH: 23.1% | [77] | |||

| rice protein | sodium citrate (pH 7.0) | 50ºC, pH 7.0, for 180 minutes |

Centrifugation (15000 g for 15 minutes) |

DH: 33.94%, |

[78] | |||

| Neutrase | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Cottonseed meal | thermal pretreatment | 0.1 M phosphate buffer | 60 ºC, pH 7.0 for 100 min | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 29.7-36.4% | [43] |

| Chia seed expeller | Protein extraction by organic and enzymatic extraction | 45 ºC, pH 7.0 | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 15% | [71] | |||

| Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 6,5, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 6.3% | [73] | |||

| Protamex | Bacillus licheniformis e Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 60 ºC, pH 8.0, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 5.4% | [73] | |

| Chia seed expeller | Protein extraction by organic and enzymatic extraction | 55 ºC, pH 8.0 | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 8% | [71] | |||

| Corolase ® 7089 | Bacillus subtilis | Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 55 ºC, pH 7.0, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 6.8% | [73] | |

| Corolase ® 2TS | Bacillus stearothermophilus | Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 70 ºC, pH 7.0, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 7.8% | [73] | |

| N-01 | Bacillus subtilis | Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 55 ºC, pH 7.2, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 4.8% | [73] | |

| Protease | Streptomyces griseus | Amaranth protein |

Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 360 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 10 minutes) | DH: 20% | [81] | |

| Quinoa protein | Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 360 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 10 minutes) | DH: 78% | [81] | |||

| Papain | Carica papaya | Black soldier fly larvae | sodium hydroxide | 60 ºC and pH 6.85 | Centrifugation (2500 g for 5 min) | 37.8% | [69] | |

| Chia seed expeller | Protein extraction by organic and enzymatic extraction | 55 ºC, pH 7.0 | Centrifugation (5000 g for 10 min) | DH: 6.5% | [71] | |||

| Soy protein | Extraction by hexane | 80 ºC, pH 7.0, for 120 minutes | Centrifugation (5600 g for 130 minutes) | DH: 4.6% | [73] | |||

| Winged bean seed | Extraction by Petroleum ether | 70 ºC, pH 6,5, for 300 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 20 minutes) | DH: 94.8% | [77] | |||

| Bromelain | Pineapple stem | Winged bean seed | Extraction by Petroleum ether | 45 ºC, pH 6,5, for 300 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 20 minutes) | DH: 74.1% | [77] | |

| Amaranth protein |

Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 360 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 10 minutes) | DH: 46% | [81] | |||

| Quinoa protein | Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 8.0, for 360 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 10 minutes) | DH: 76% | [81] | |||

| Amaranth protein |

Extraction by hexane | 50 ºC, pH 7.0, For 120 minutes |

Centrifugation (10000 g for 10 minutes) | DH: 35.4% | [82] |

| Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Scalability | Fermentation processes can be easily scaled in industrial bioreactors, increasing productivity. | The transition from lab to industrial scale may face challenges in optimization and cost. |

| Growth Rate | Microorganisms grow rapidly under controlled conditions, allowing for short production cycles. | Some microorganisms may require specific and challenging conditions to maintain at large scales. |

| Use of Diverse Substrates | Can utilize agro-industrial residues as substrates, promoting sustainability. | Specific residues require expensive and complex pretreatments to be utilized by microorganisms. |

| Conversion Efficiency | High efficiency in converting substrates into protein-rich biomass. | The presence of inhibitory compounds in the substrate may hinder conversion. |

| Process Control | Fermentation in a controlled environment (pH, temperature, oxygen) ensures product quality and standardization. | Requires constant monitoring and sophisticated equipment, raising operational costs. |

| Production Versatility | Various microorganisms (fungi, yeast, algae, bacteria) can be used to produce different types of SCP. | Regulations or infrastructure needs may limit the selection of the appropriate microorganism. |

| Sustainability | Lower land and water usage compared to traditional agriculture. | Energy consumption in industrial fermentation can be significant, depending on scale and technology. |

| Contamination | Contamination can be prevented through effective sterilization processes. | If sterility control fails, there is a high risk of cross-contamination with other microorganisms. |

| Final Product Flexibility | SCP can be tailored for different nutritional or textural profiles to meet market needs. | The process to modify product characteristics may be expensive and complex. |

| Regulations | Fermentation production models already have established regulatory guidelines for food safety. | New fermented products may face stricter or slower regulatory approval processes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).