Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

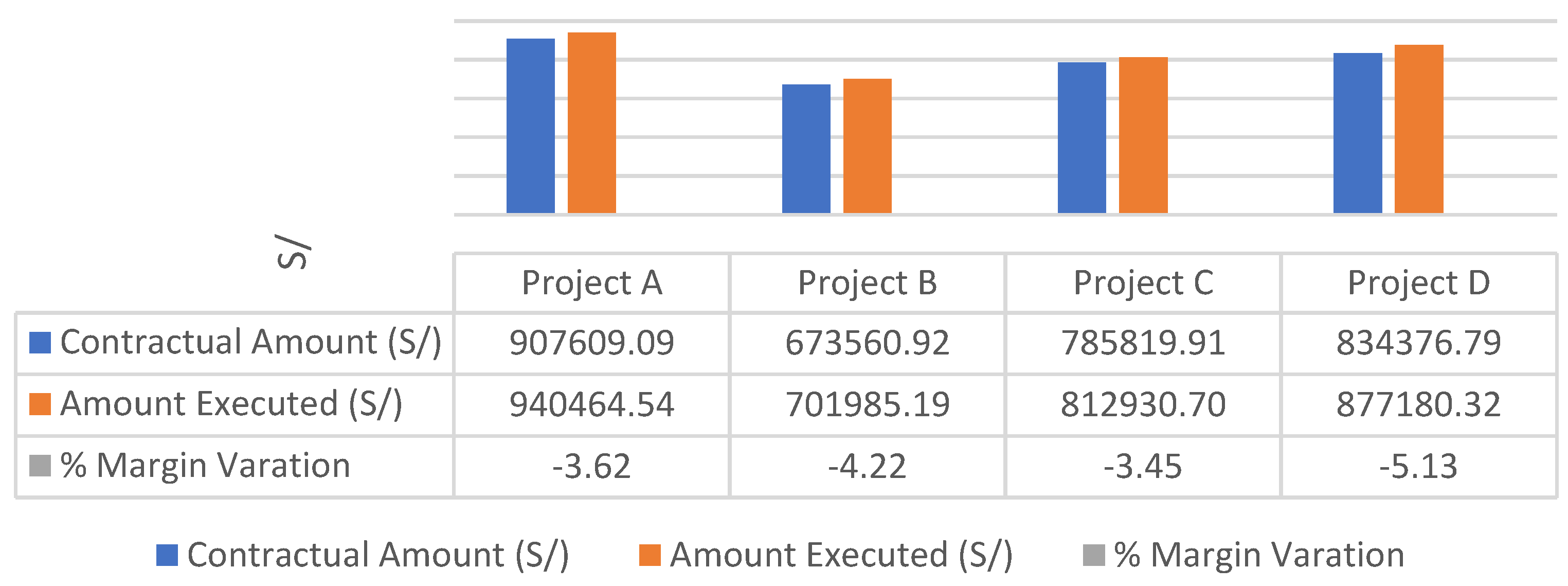

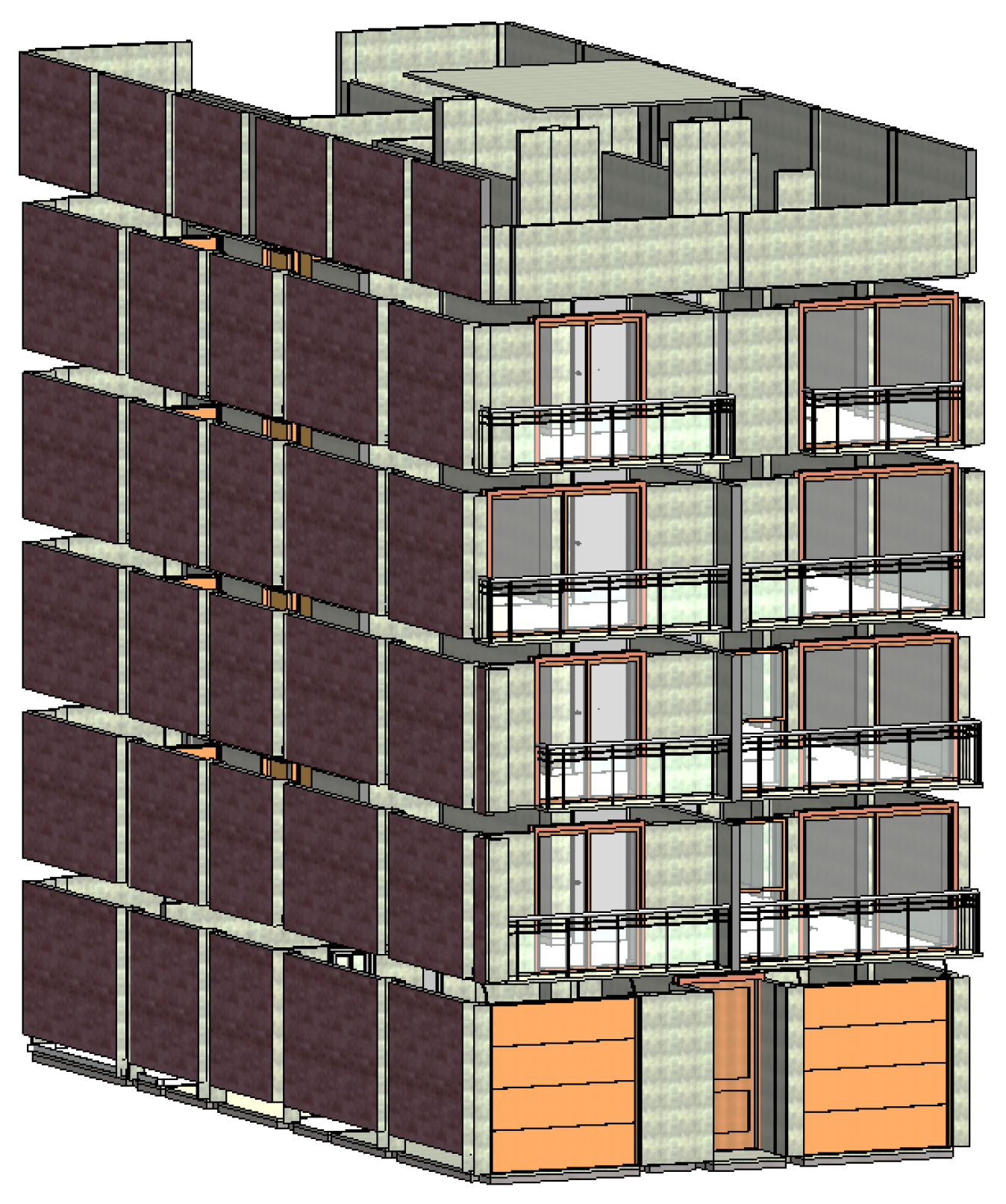

4. Results

4.1. Diagnosis

4.1.1. SME Description

4.1.2. Description of the case study

4.1.2. Typical management problems

- P1: Deficiencies in the blueprints.

- P2: Deficiencies in the measurement and budget.

- P3: Weak team communication, coordination, and collaboration.

- P4: Modifications and/or reworks.

- P5: Existence of hidden flaws that generate additional work.

- P6: Cost overruns in the construction process.

- P7: Delays due to poor planning in material supply and errors in material purchasing.

- P8: Lack of clarity and transparency in the contract and its clauses.

- P9: Lack of incentives for good practices.

4.2. Optimization Proposals

4.2.1. H1: Contractual Management – Standardized Contract

- Communication (X13).

- Early Warnings (X15).

- Compensation Events (Core Clause 6).

- Incentives.

- Dispute Avoidance Board (W3).

4.2.2. H2: Common Data Environment (CDE)

4.2.3. H3: Software

4.2.4. H4: Work Teams

4.2.5. H5: ICE Sessions

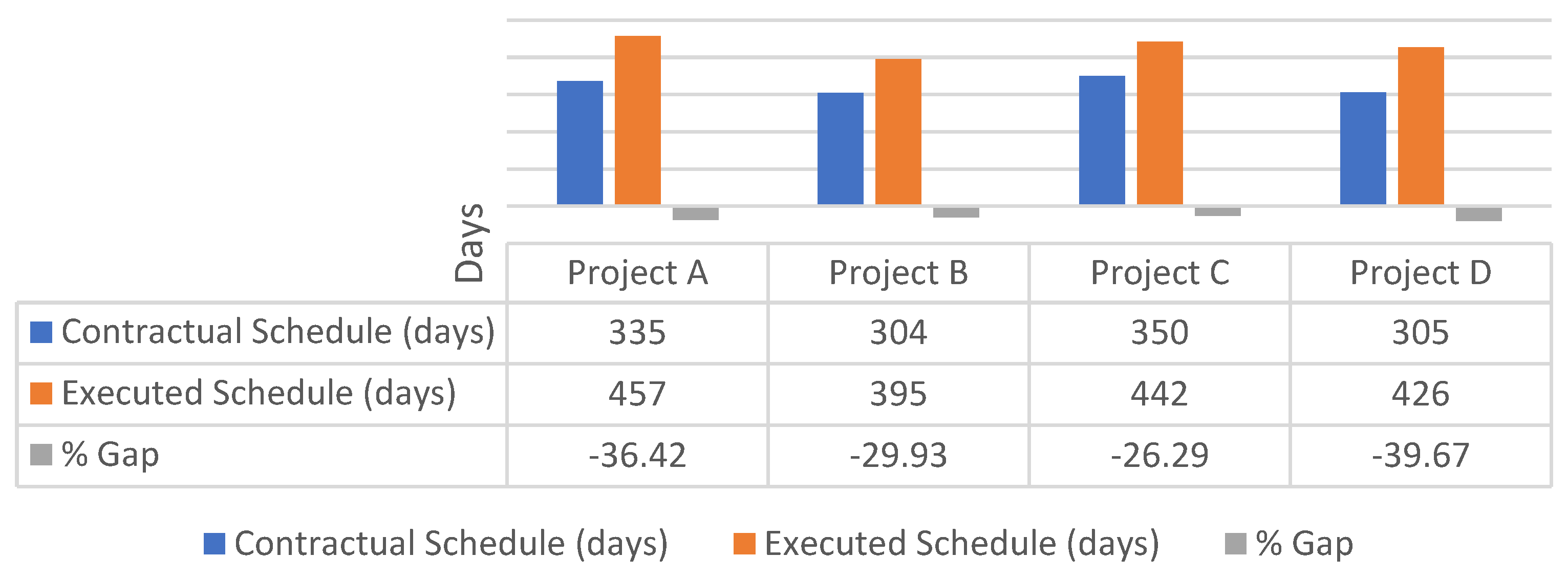

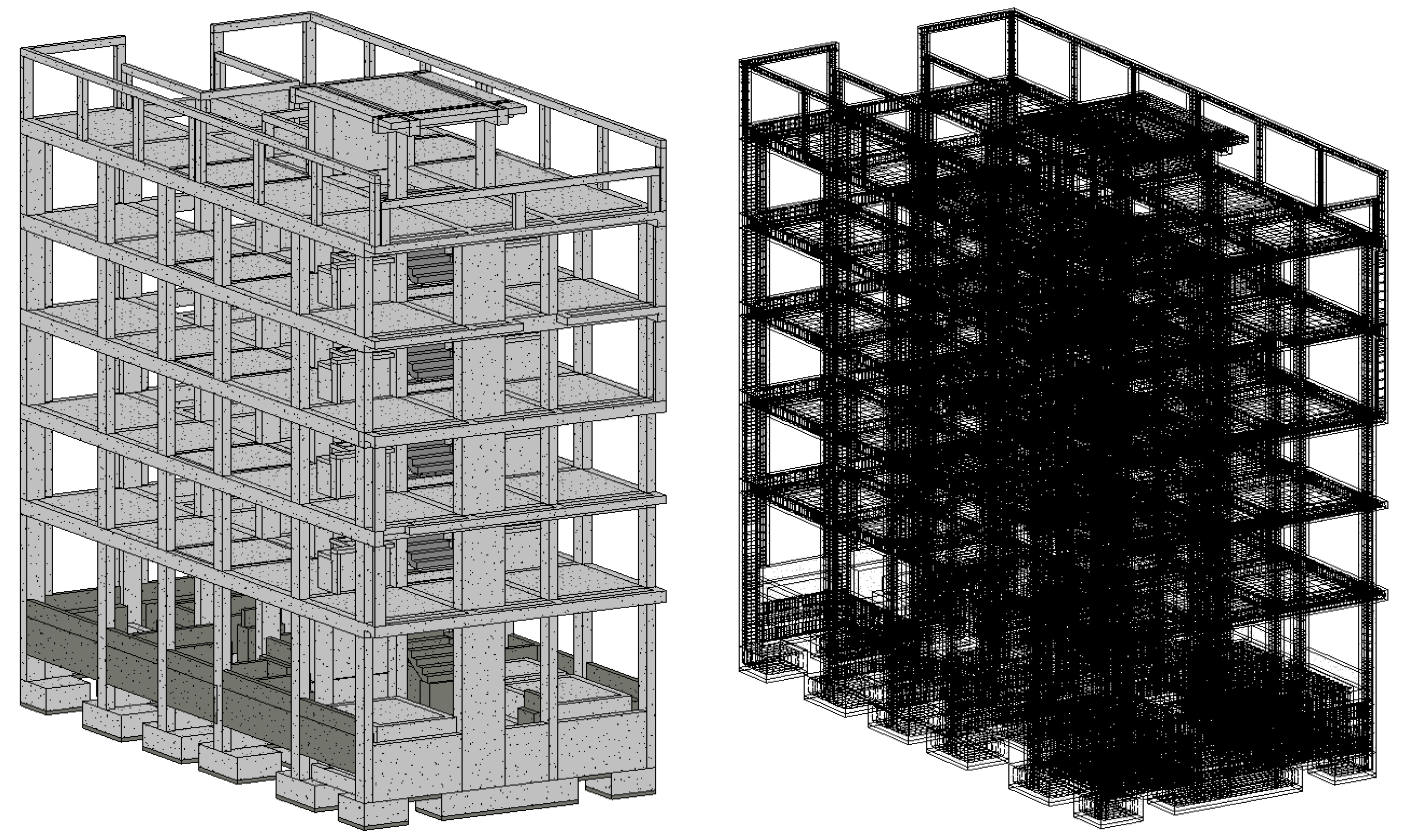

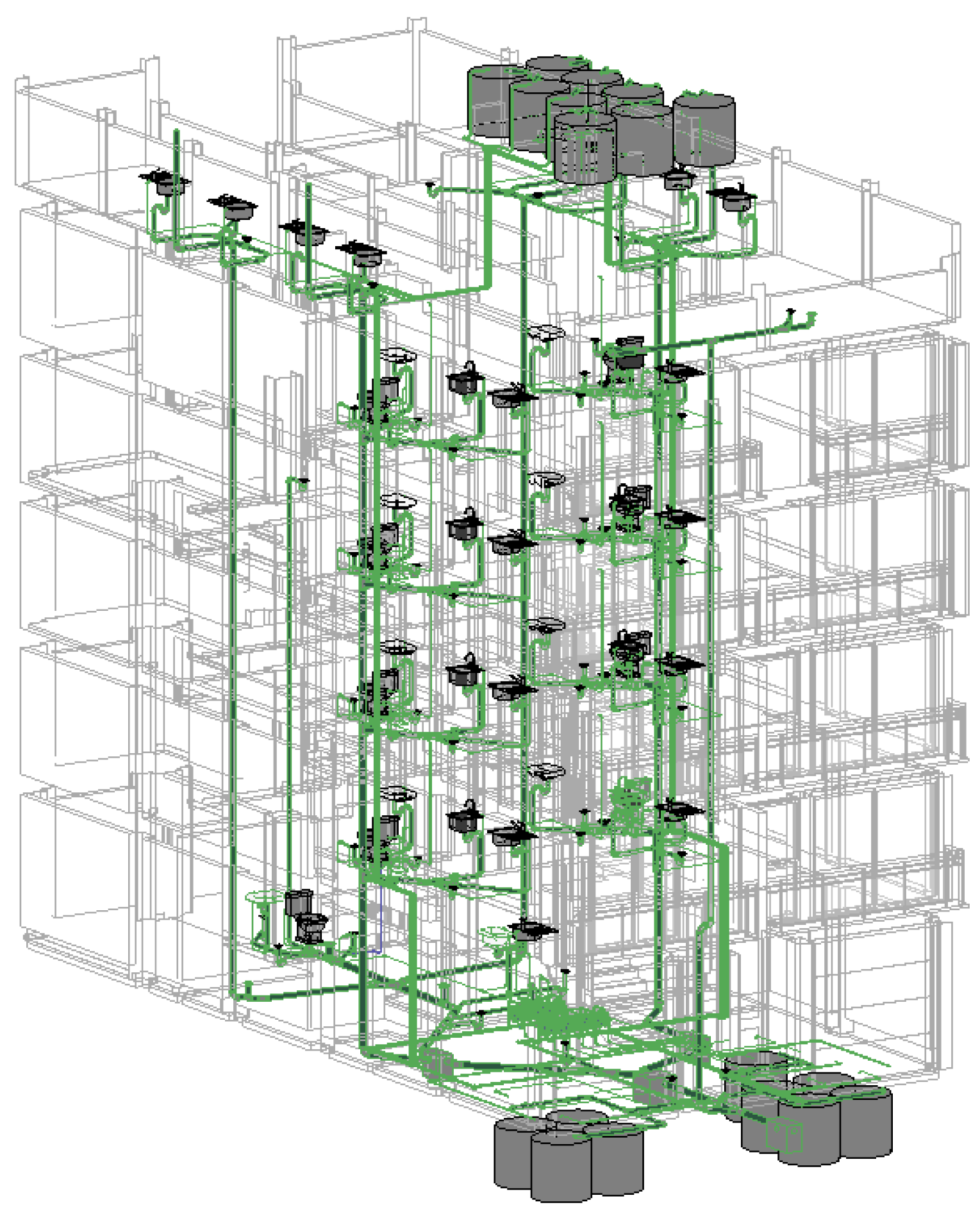

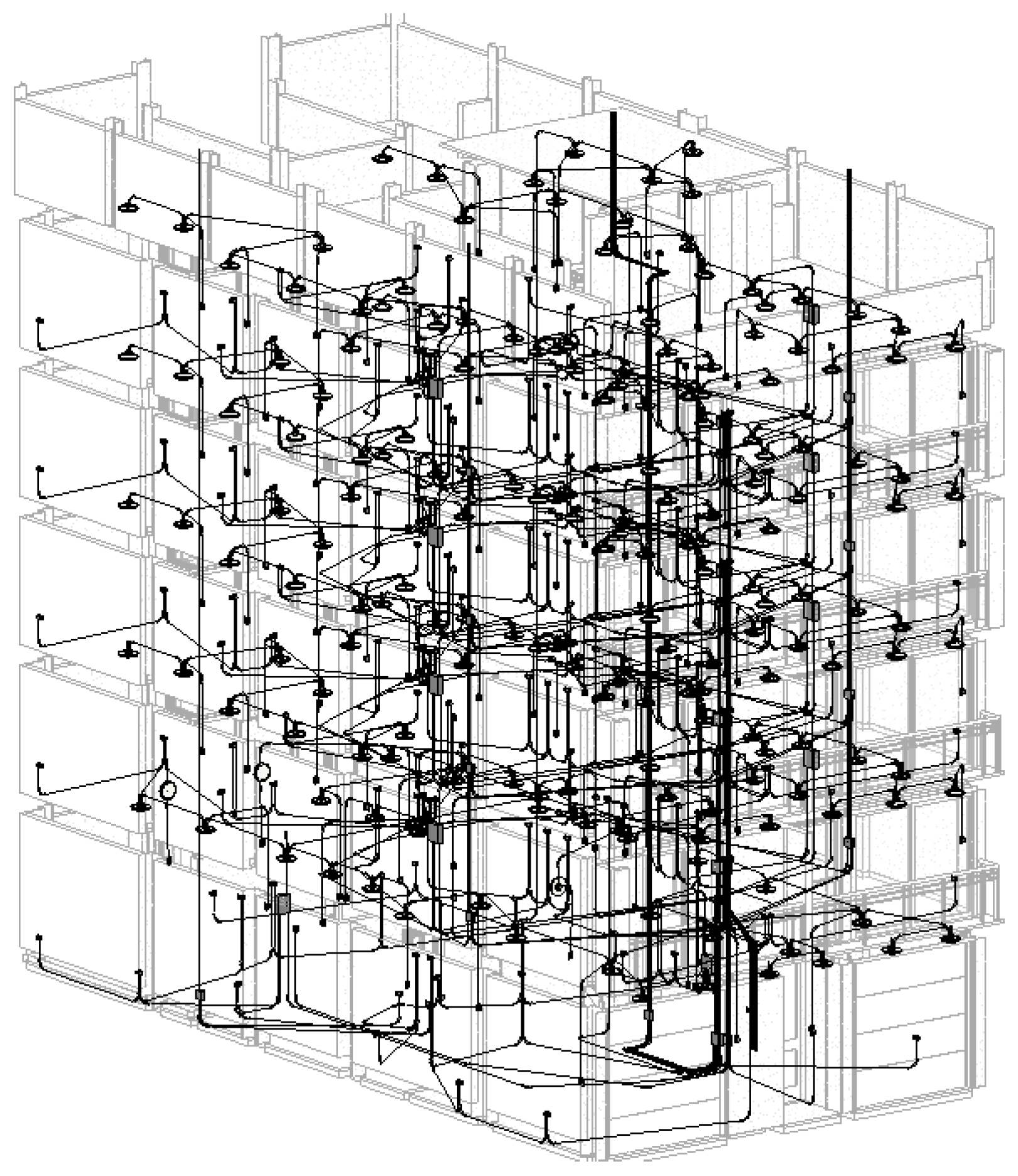

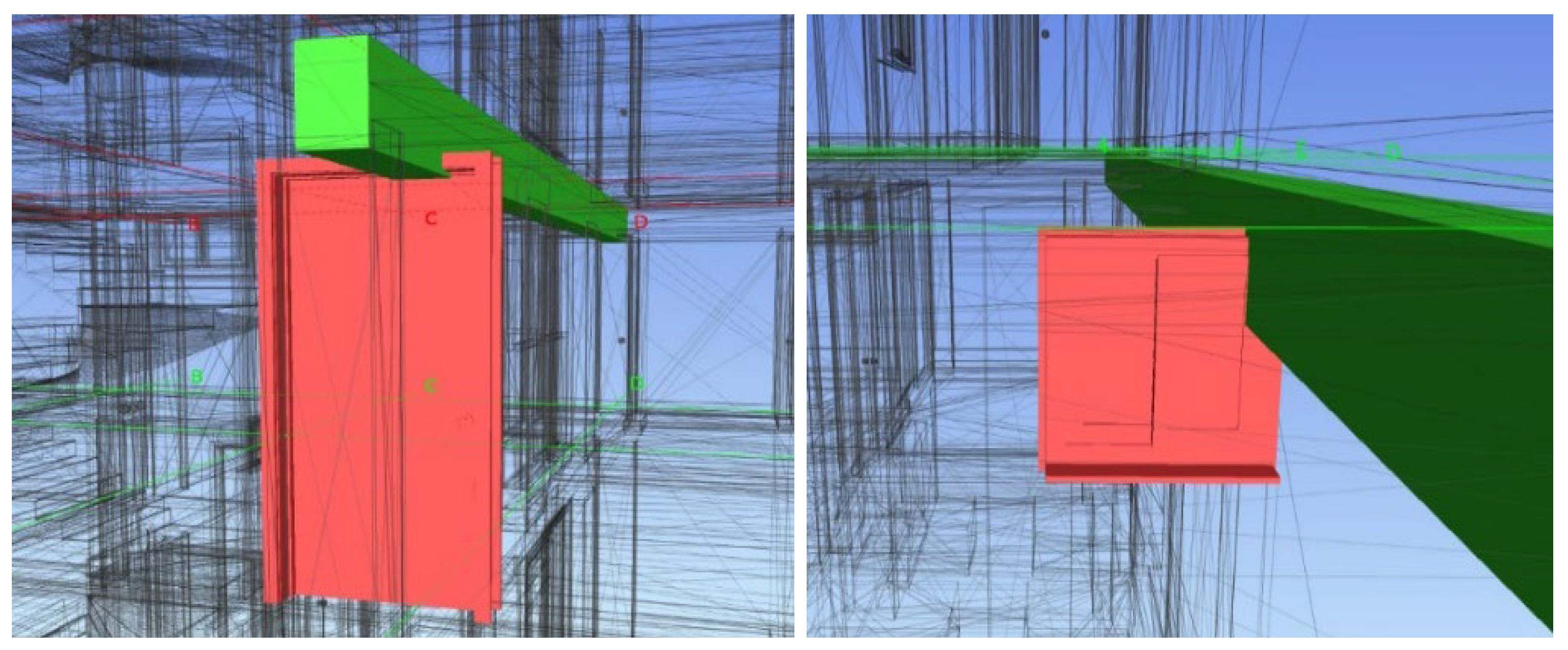

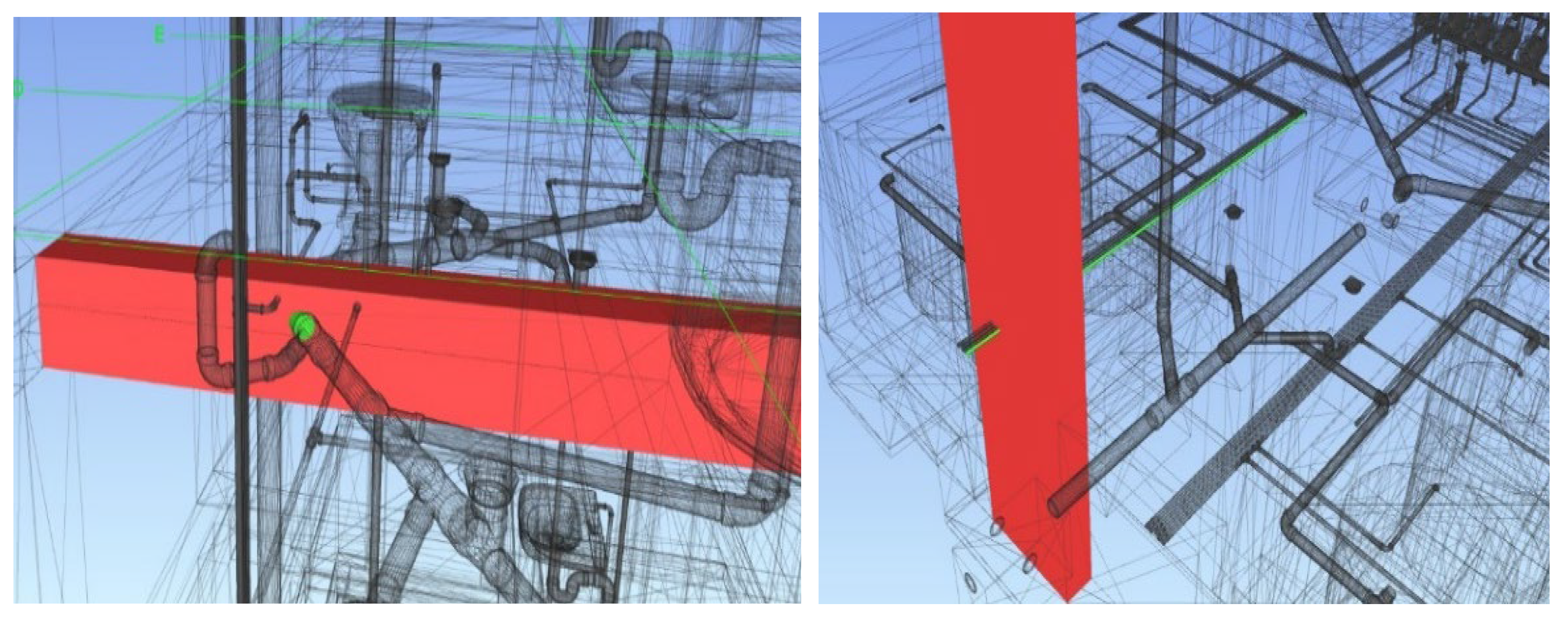

4.2.6. H6: 3D Model

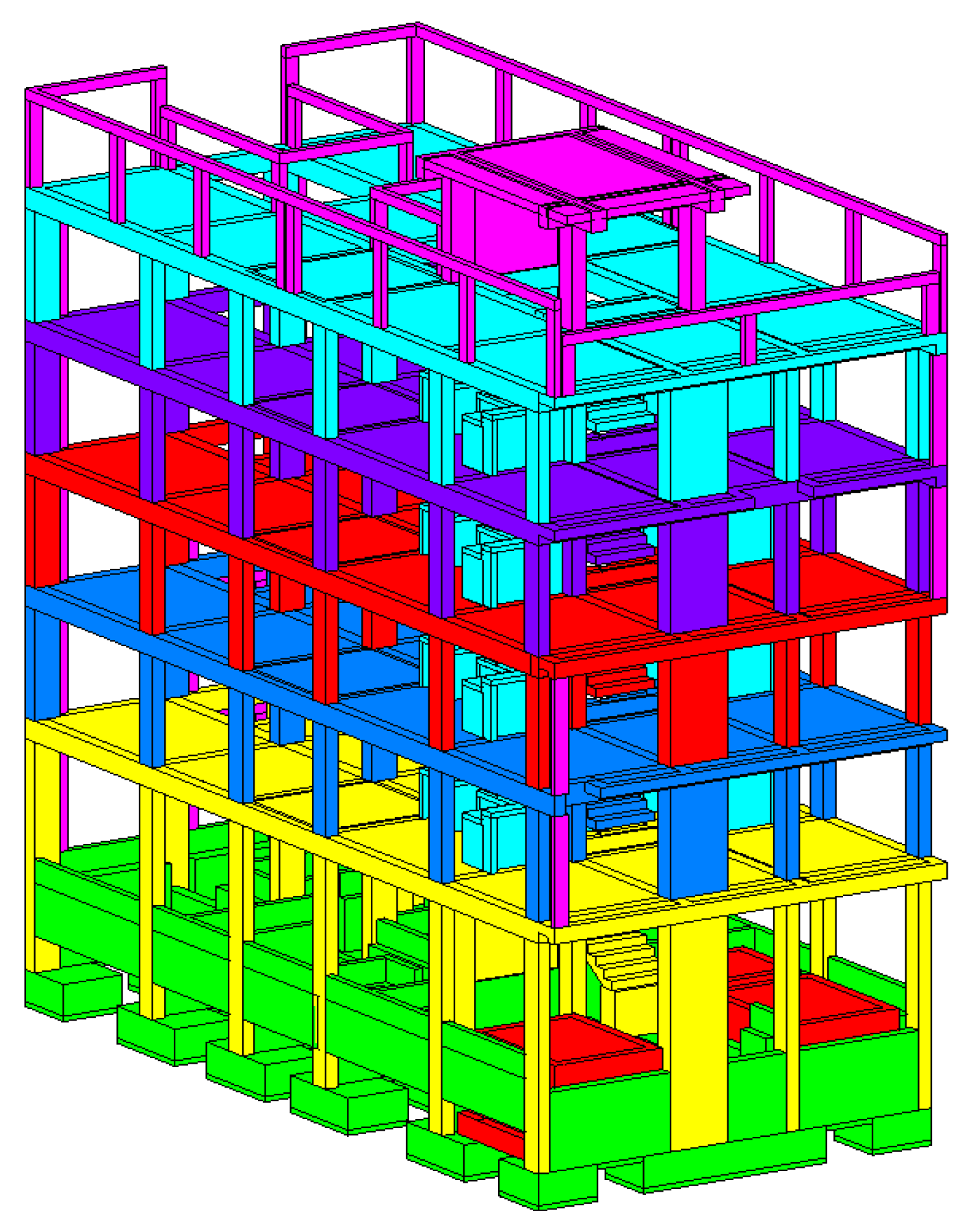

- Structural Modeling.

- Architectural Modeling.

- Sanitary Installations Modeling.

- Electrical Installations Modeling.

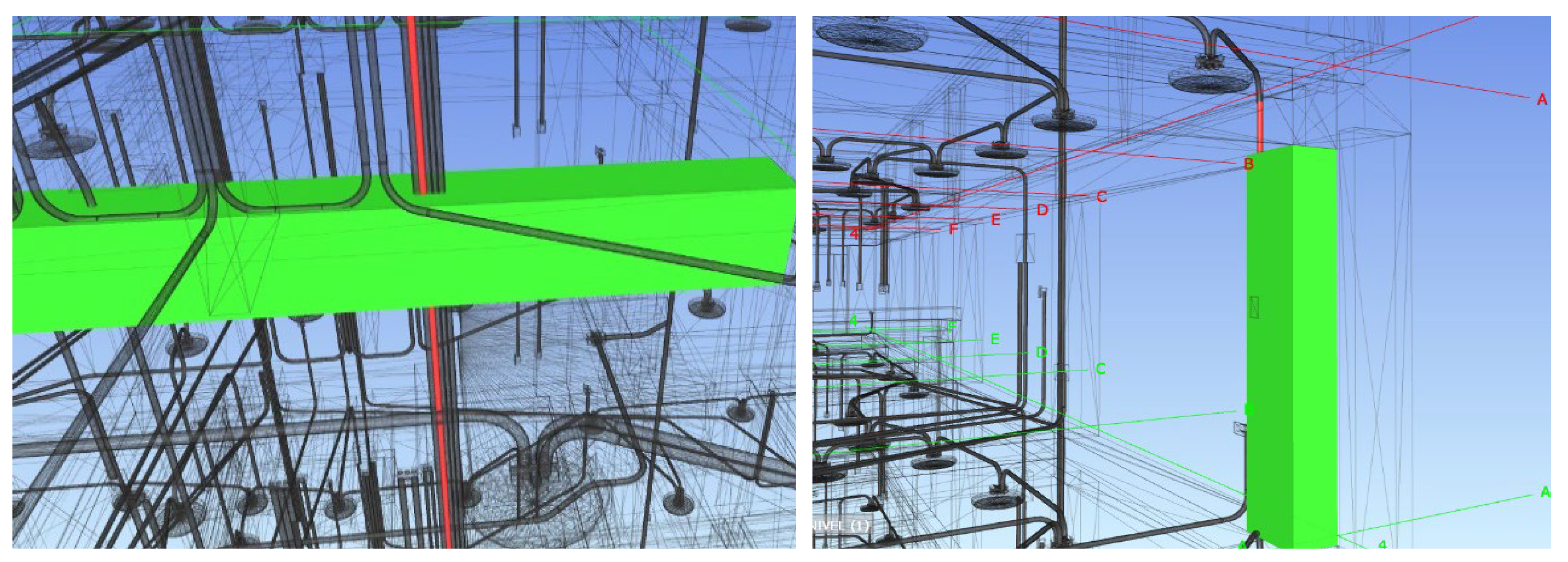

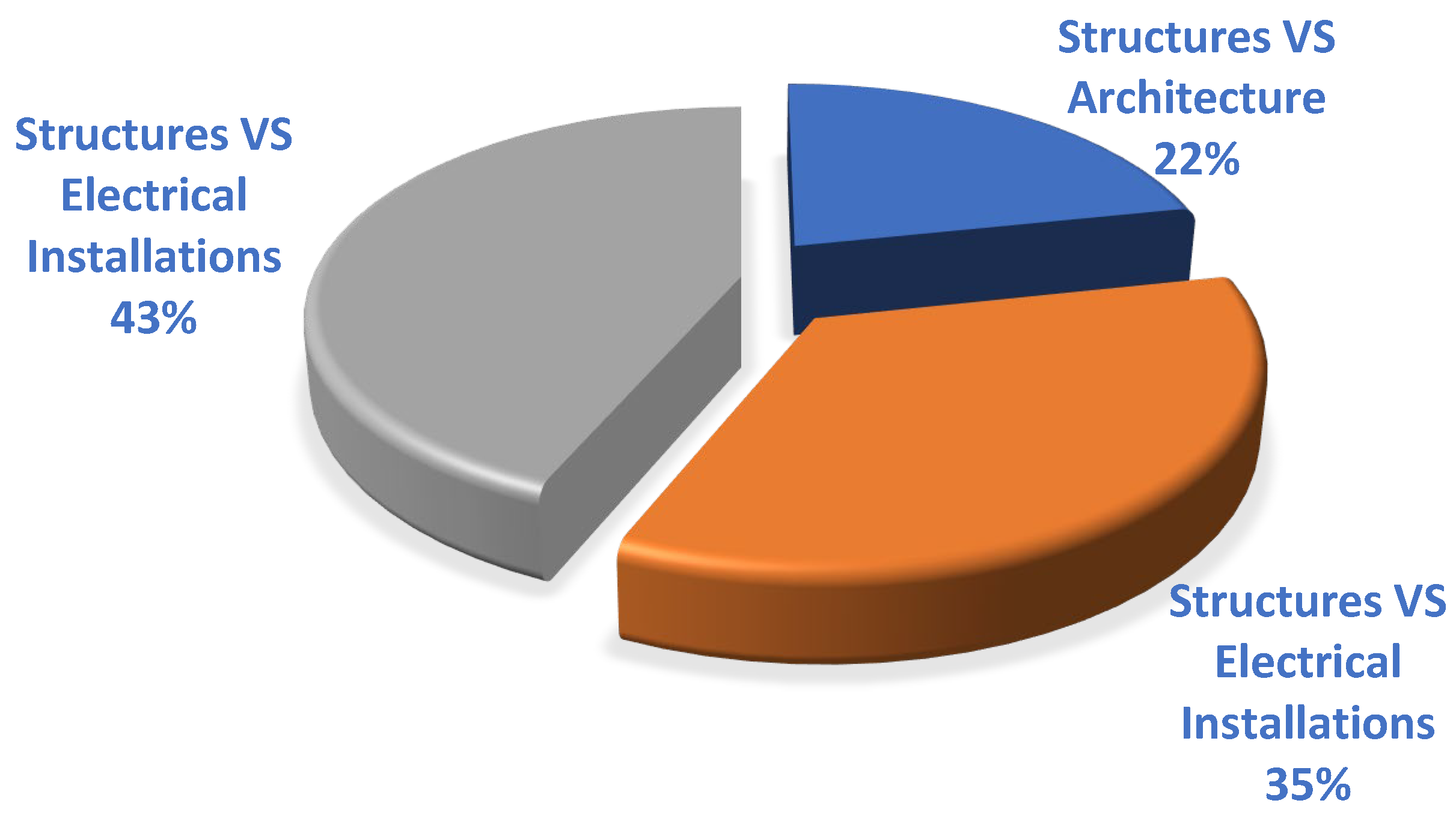

- Interference Detection.

4.2.7. H7: 4D Model

4.2.8. H8: 5D Model

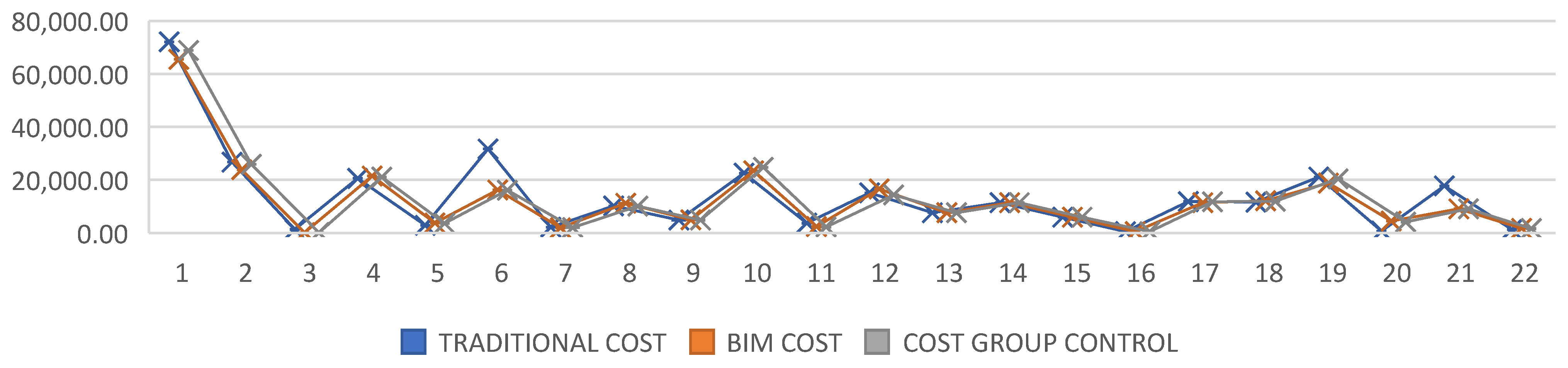

- Structures.

- Architecture.

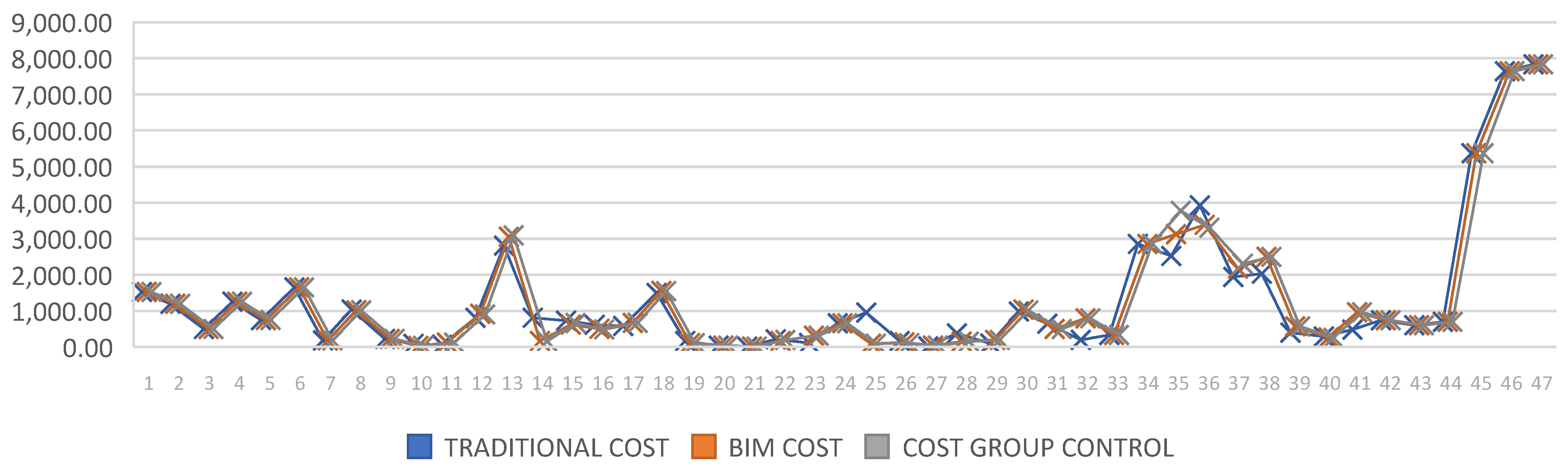

- Sanitary Installations.

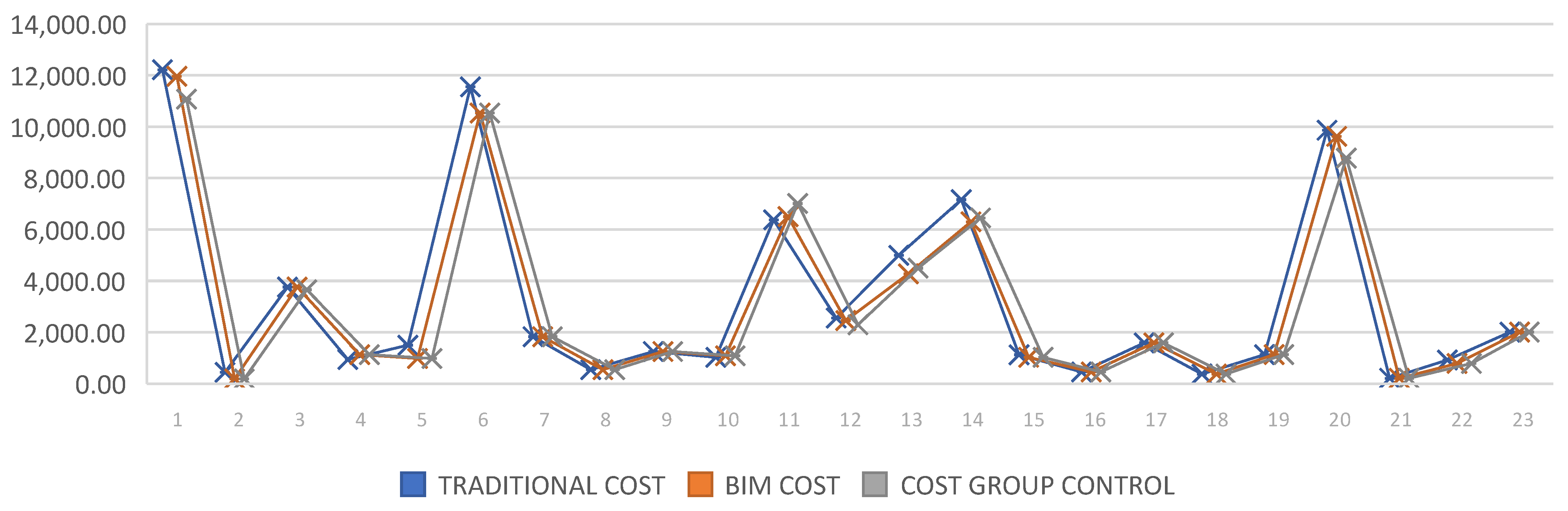

- Electrical Installations.

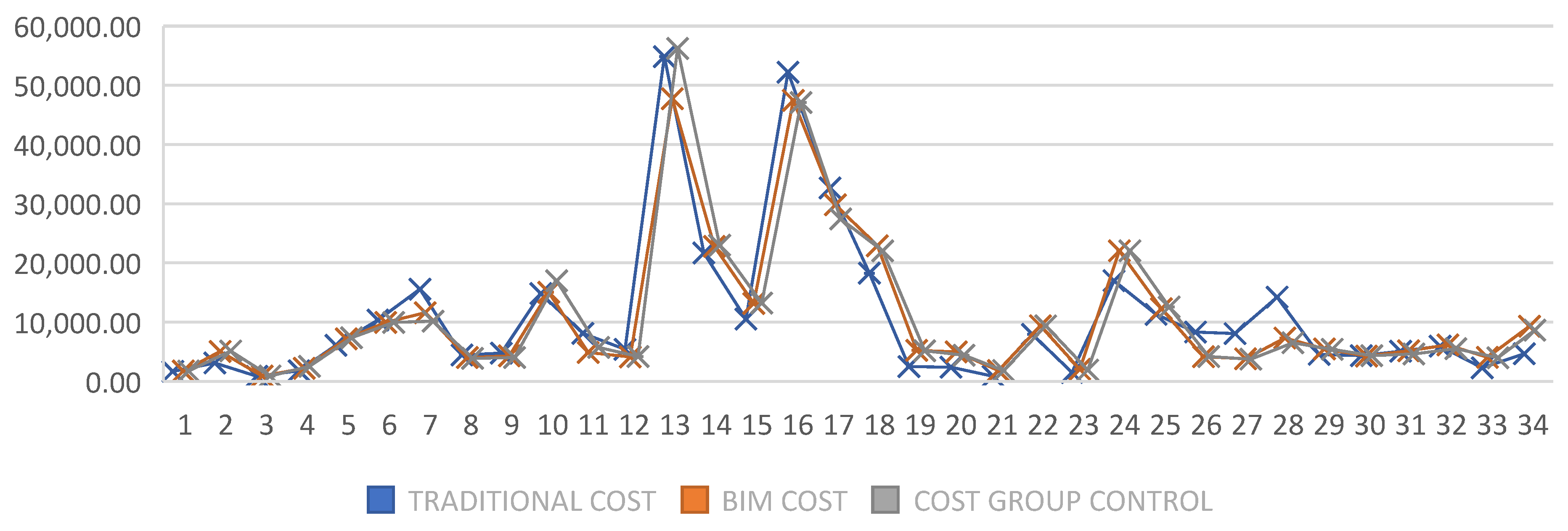

- Analysis of item variation.

- Cost Comparison.

- BIM and IPD Profitability Analysis.

4.3. Validation

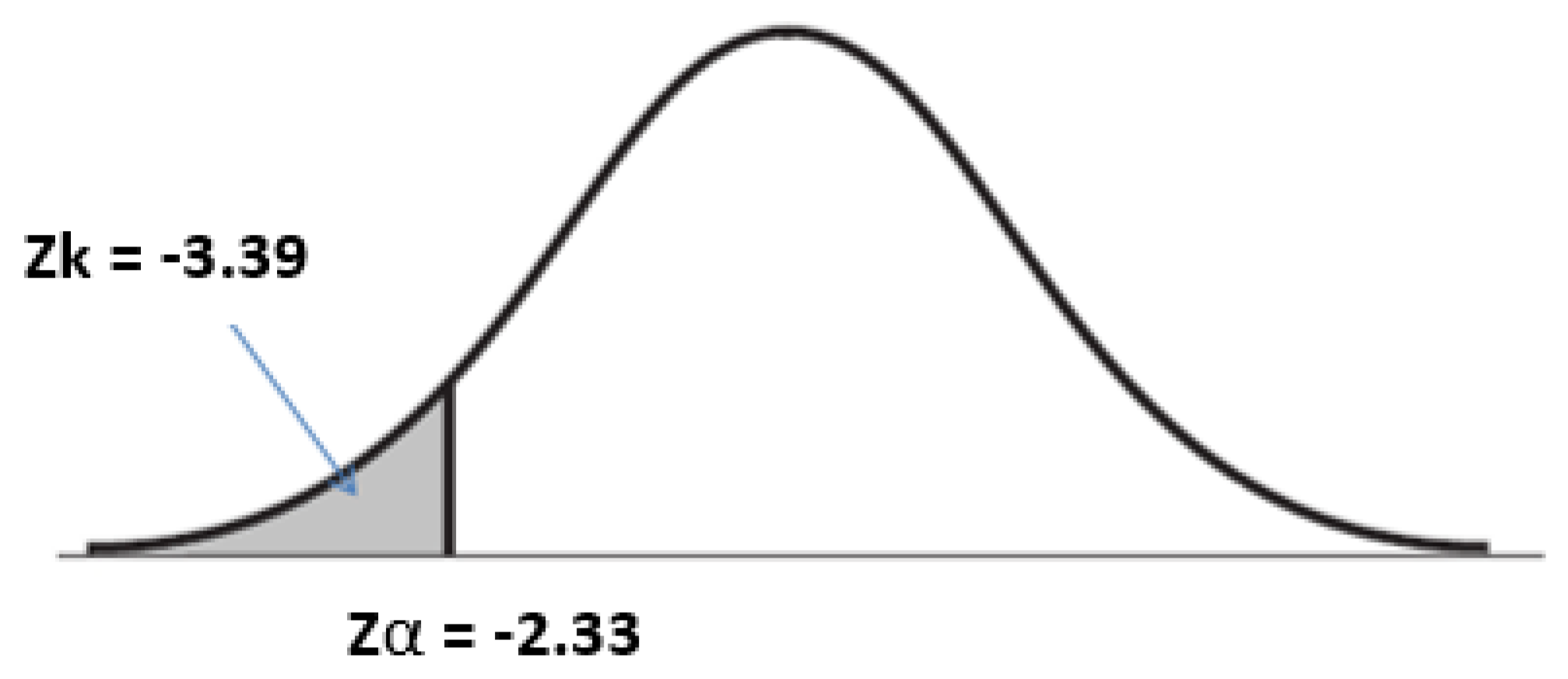

4.3.1. Statistical Analysis

| Hypothesis | Symbol | Description | Expression | Decision rule |

| Alternative H. | Ha | With BIM methodology, costs are optimized. | µ1 < µ2 1 | IF REJECTED Ho Si: Zk < Zα |

| Null H. | H0 | With the BIM methodology, costs are not optimized. | µ1 ≥ µ2 1 | IF ACCEPTED Ho Si = Zk ≥ Zα |

| Sample | No. | Media | Standard Deviation |

| % Variation BIM / G.C. | 126 | x1 = 3.04 % | σ1 = 40.15 % |

| % Variation E.T. / G.C. | 126 | x2 = 40.15 % | σ2 = 122.90 % |

4.3.2. Validation Matrix

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asvadurov, S.; Varilla, R.; Brindado, T.; Brown, T.; Knox, D.; Ellis, M. The art of project leadership: Delivering the world's largest projects; 2017.

- Buk'hail, R.; Al-Sabah, R.S. Exploring the Barriers to Implementing the Integrated Project Delivery Method. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, H.A.; Molenaar, K.R.; Alarcon, L.F. Exploring performance of the integrated project delivery process on complex building projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, P. Metodología para minimizar las deficiencias de diseño basada en la construcción virtual usando tecnologías BIM. 2013.

- Maciel, A.C.F.; de Souza, D.A.; Oliveira, P.H. Detection of design incompatibilities between traditional 2D and bim methodology: A comparative study. Rev. Gest. Proj. 2022, 13, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza Vigil, A.J.; Carhart, N.J. Local infrastructure governance in Peru: A systems thinking appraisal. Infrastructure Asset Management 2024, 11, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Contraloría General de la República del Perú. Reporte de obras paralizadas en el territorio Nacional a mayo 2023. 2023.

- Tapia, E. Hay más de S/ 29 mil millones en obras, paralizados por malos expedientes técnicos. Voces 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Acero, Y. Consejero regional anuncia reanudar obras paralizadas en Tacna. Radio Uno 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J.; El Asmar, M.; Chalhoub, J.; Obeid, H. Two Decades of Performance Comparisons for Design-Build, Construction Manager at Risk, and Design-Bid-Build: Quantitative Analysis of the State of Knowledge on Project Cost, Schedule, and Quality. J Constr Eng Manage 2017, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIA. AIA California Council. Integrated Project Delivery A Guide. 2007.

- Ahmed, M.M.; Lotfy, S.M.; Othman, A.A.E.; Hammad, H.A. An Analytical Study of the Current Status of Managing Change Orders during the Construction Phase of Governmental Projects in Egypt. MEJ Mansoura Engineering Journal 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Architects, Engineers and Contractors; 2008.

- Kent, D.C.; Becerik-Gerber, B. Understanding construction industry experience and attitudes toward integrated project delivery. J Constr Eng Manage 2010, 136, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M.; Elghaish, F.F.; McIlwaine, S.; Brooks, T. Feasibility of implementing ipd approach for infrastructure projects in developing countries. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 902–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez, D.S. Retos de la implementacion de BIM durante la etapa de diseño de infraestructura de salud. 2023.

- Murguía, D. Tercer estudio de adopcion BIM en proyectos de edificacion en Lima; Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Perú: Lima, Perú, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MEF. Plan de implementación y Hoja de Ruta del Plan BIM Perú. 2021.

- Franz, B.; Leicht, R.; Molenaar, K.; Messner, J. Impact of Team Integration and Group Cohesion on Project Delivery Performance. J Constr Eng Manage 2017, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, J.; Leicht, R.M. Practices for Designing Cross-Functional Teams for Integrated Project Delivery. J Constr Eng Manage 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Teo, P.X.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Q. Adoption of Integrated Project Delivery Practices for Superior Project Performance. J. Legal Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Construction 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.A.E.; Youssef, L.Y.W. A framework for implementing integrated project delivery in architecture design firms in Egypt. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 19, 721–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.K.; Alsanad, A.; Alsadan, A.; Sherif, M.; Mohamed, A.G. Scrutinizing the Adoption of Integrated Project Delivery in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Construction Sector. Buildings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinezhad, M.; Saghatforoush, E.; Kahvandi, Z.; Preece, C. Analysis of the Benefits of Implementation of IPD for Construction Project Stakeholders. CIVIL ENGINEERING JOURNAL-TEHRAN 2020, 6, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Rajasekaran, C. Comparison of Afghanistan’s Construction and Engineering Contract with International Contracts of FIDIC RED BOOK (2017) and NEC4—ECC. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 2023; pp. 299–313.

- Yabar-Ardiles, O.; Sanchez-Carigga, C.; Vigil, A.J.E.; Málaga, M.S.G.; Zevallos, A.A.M. Seeking the Optimisation of Public Infrastructure Procurement with NEC4 ECC: A Peruvian Case Study. BUILDINGS 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.H.; Mesthrige, J.W.; Lam, P.T.I.; Javed, A.A. The challenges of adopting new engineering contract: A Hong Kong study. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2019, 26, 2389–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.J.; Mendoza, J.C. Propuesta de un método de integración basado en las herramientas de Integrated Project Delivery y Virtual Design and Construction para reducir el impacto de las incompatibilidades en la etapa de diseño de edificios residenciales de alto desempeño en Lima Metropolitana. 2019.

- El Asmar, M.; Hanna, A.S.; Loh, W.Y. Quantifying Performance for the Integrated Project Delivery System as Compared to Established Delivery Systems. J Constr Eng Manage 2013, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, H.D.; Eduardo, R.C.; Rodrigues, K.C.; de Paula, H.M. Case study of analysis of interferences between the discipline of a building with conventional designs (re) modeling in BIM. Mater. Rio De Jan. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, D.F.A.; Ferreira, M.E.C.; Ferreira, M.P. Compatibility of design through BIM methodology. REVISTA INGENIERIA DE CONSTRUCCION 2023, 38, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, J.; Datta, S.D.; Islam, M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Sraboni, S.A.; Das, N. Assessment and analysis of the effects of implementing building information modelling as a lean management tool in construction management. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.; Trebes, B. Managing Reality: Book One; 2017.

- Chirinos Santander, L.R.; Pecho Llacta, J.C. Implementación de la metodología BIM en la construcción del proyecto multifamiliar DUPLO para optimizar el costo establecido. Implementation of the BIM methodology in the construction of the DUPLO multifamily project to optimize the established cost 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, J.; Quiroz, L. Análisis del retorno de inversión al aplicar Building Information Modeling (BIM) en un proyecto inmobiliario. (Lima - Perú). 2020.

- Ureta, D.D.; Chileno, J.O. Analisis comparativo de la rentabilidad entre el modelo convencional CAD y el BIM en la etapa de planificacion del bloque de administración de la escuela técnico superior PNP - Arequipa. 2022.

- Wright, J.N.; Fergusson, W. Benefits of the NEC ECC form of contract: A New Zealand case study. International Journal of Project Management 2009, 27, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehry, F.; Lloyd, M.; Shelden, D. Empowering Design: Gehry Partners, Gehry Technologies and Architect-Led Industry Change. Architectural Design 2020, 90, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.S.; Evangelista, A.C.J.; Hammad, A.W.A.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Haddad, A. Evaluation of 4D BIM tools applicability in construction planning efficiency. International Journal of Construction Management 2022, 22, 2987–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Importance or Relevance | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Franz, et al. [19] | Analyzes how team integration and group cohesion influence project performance in the U.S., using different execution methods. | Surveys. |

| Laurent and Leicht [20] | Identifies organizational practices for the use of cross-functional teams in IPD projects in the USA. | Surveys, Case study. |

| Ling, et al. [21] | Examines the effect of the application of IPD practices on the performance of traditional projects in Singapore. | Case study, Questionnaires. |

| Buk'hail and Al-Sabah [2] | Examines the willingness to implement IPD in Kuwait's construction industry. | Literature review, Questionnaires. |

| Othman and Youssef [22] | Develops a framework for the implementation of IPD approach at the design stage for ADF in Egypt. | Literature review, Case study, Questionnaires. |

| Alqahtani et al. [23] | Investigates the bidding process and procurement regulation in Saudi Arabia for IPD implementation. | Literature review, Surveys. |

| Alinezhad et al. [24] | Identifies the benefits of implementing the IPD approach in U.S. building projects. | Literature review, Case study. |

| Ajmal and Rajasekaran [25] | Examines and compares Afghanistan's construction and engineering contracts with NEC4 ECC standardized contracts. | Literature review, Case study. |

| Yabar-Ardiles, et al. [26] | Examines and compares public building and construction contracts in Peru with the NEC4 ECC standardized contract. | Literature review, Case study. |

| Lau, et al. [27] | Identifies the challenges that hinder the widespread implementation of NEC in Hong Kong. | Surveys, Semi-structured interviews. |

| Khanna, Elghaish, McIlwaine and Brooks [15] | Investigate the viability of implementing IPD along with BIM and ICT in projects in India. | Literature review, Interviews. |

| Bravo and Mendoza [28] | Design an integration proposal to reduce the causes of losses in the design stage, using IPD and VDC tools in Peruvian projects. | Surveys, Case study. |

| El Asmar, et al. [29] | Examines the performance of IPD projects compared to non-IPD projects in the US. | Literature review, Surveys, Case study. |

| Mesquita, et al. [30] | Demonstrates the use of BIM for modeling and interference analysis on a project in Brazil. | Case study. |

| Dos Santos, et al. [31] | Analyzes how BIM methodology is used to ensure project compatibility in Brazil. | Case study. |

| Yañez [16] | Determines the challenges associated with the implementation of BIM in the design of healthcare projects in Peru. | Literature review, Case study, Interviews. |

| Akter, et al. [32] | Investigates and evaluates the impacts of using BIM as a construction management tool in Bangladesh. | Surveys, Case study. |

| Section | Objectives | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| 4.1 | To conduct a diagnosis on the management of residential building projects for the SME. | Analysis of management practices in SME residential building projects through documentation review and semi-structured interviews. Analysis of an SME residential project through documentation review and semi-structured interviews. Identification of typical issues in the SME. |

| 4.2 | to propose an optimization of the SME by integrating IPD and BIM. | Literature review on BIM and IPD tools that can be implemented to improve management and a description of their application. |

| 4.3 | To validate the proposal for optimization of IPD and BIM integration. | Validation statistical analysis via Z-test. Elaboration of a validation matrix for the implementation of improvement tools integrating BIM and IPD. |

| Indicator | SME Case Study Contract |

| Clarity and simplicity | Specifications |

| Number of clauses | The contract stipulates seven clauses. |

| Linguistic level | The contract primarily uses legal language. |

| Contract parties | The contract only mentions the Client, which is the SME, and the contractor. There is no direct mention of the other parties and their responsibilities under the contract; only the construction manager is mentioned in the sixth clause. |

| Stimulus for good management | Specifications |

| Payment | The contract establishes monthly appraisals as a form of payment. |

| Incentives | The contract does not stipulate any incentives for good practices on behalf of the contractor or other contract agents, only penalties for unjustified delays. |

| Communication systems | The contract does not mention any type of communication system or mechanism that requires the parties to make notifications through the contract. |

| Early warnings | The contract does not stipulate any early warning mechanism. |

| Conflict resolution | Two dispute resolution mechanisms are contemplated, conciliation or arbitration. |

| Risk allocation | The contract does not stipulate risk allocation. |

| Data | |

| Roofed area (m2) | 617.87 |

| Interferences (No.) | 295 |

| Interferences (m2) | 0.48 |

| Specialty | Total items | P. with variation | P. without variation | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. with variation | P. without variation | ||||

| Structures | 34 | 34 | 0 | 100.00% | 0.00% |

| Architecture | 22 | 18 | 4 | 81.82% | 18.18% |

| Sanitary Installations | 47 | 28 | 19 | 59.57% | 40.43% |

| Electrical Installations | 23 | 13 | 10 | 56.52% | 43.48% |

| Total | 126 | 93 | 33 | 73.81% | 26.19% |

| Item | Und | Nº of Items | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total project items analyzed | und | 126 | 100.00% |

| Total items with variation | und | 93 | 73.81% |

| Total items without variation | und | 33 | 26.19% |

| Specialty | Traditional methodology | BIM Methodology | Difference |

| Structures | S/ 367,773.24 | S/ 362,032.92 | S/ 5,740.32 |

| Architecture | S/ 304,190.49 | S/ 275,158.84 | S/ 29,031.65 |

| Sanitary | S/ 58,642.92 | S/ 59,213.74 | -S/ 570.81 |

| Electrical | S/ 73,823.83 | S/ 69,987.36 | S/ 3,836.47 |

| Total | S/ 804,430.48 | S/ 766,392.86 | S/ 38,037.63 |

| Description | Quantity |

| Training Cost | S/ 4,247.36 |

| Modeling and management cost | S/ 4,350.00 |

| BIM and IPD implementation cost | S/ 8,597.36 |

| Description | Quantity |

| Direct Cost Adjustment with BIM | S/ 38,037.63 |

| BIM and IPD Implementation Cost | S/ 8,597.36 |

| Net income | S /29,440.27 |

| ROI | 342.43% |

| Proposed Tools | Problem to be solved | |||||||||

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | ||

| H1 | Standardized Contract: NEC4 ECC | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| H2 | CDE – Trimble Connect | X | X | X | X | |||||

| H3 | Software: Revit and Navisworks | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| H4 | Work Teams | X | X | X | ||||||

| H5 | ICE Sessions | X | X | X | X | |||||

| H6 | 3D BIM Model | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| H7 | 4D BIM model | X | X | X | ||||||

| H8 | 5D BIM model | X | X | X | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).