1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have revolutionized many domains, from image recognition to natural language processing, by enabling machines to learn and generalize from large datasets. However, the majority of these networks rely on floating-point precision, which demands significant computational resources, memory, and power. This requirements becomes problematic in resource-constrained environments, where energy efficiency and hardware limitations are crucial factors. Binary Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), which operate using binary weights and activations, offer a solution by drastically reducing memory footprints and computational overhead. Despite their efficiency, binary networks struggle to extract fine-grained details due to the limitations imposed by discrete integer operations, particularly in stride-based feature extraction in convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

Traditionally, CNNs rely on fixed, integer strides to control the movement of convolutional filters across an input. While effective, fixed strides limit the network’s adaptability to extract features at multiple scales, especially in binary networks where precision is inherently lower. Stride is the number of rows and columns that the convolution kernel slides over the input matrix in order from left to right and top to bottom, starting from the top left of the input martix [7] This presents a challenge when attempting to capture granular features in binary networks without increasing network depth, or complexity.

1.2. dynamic Stride Adjustment for Fractional Strides

To address these challenges, we propose a novel method to simulate fractional stride decreases in binary ANNs by dynamically adjusting strides using exponential or logarithmic decay functions. This dynamic stride mechanism allows the stride to decrease progressively over time, approximating fractional strides, which enables the network to capture increasingly fine-grained spatial details at deeper layers. Traditionally, when evaluating the output at every position, its termed as a stride of one [5]. This study is challenging this limitation. The ability to simulate fractional strides in binary ANNs without requiring more layers or neurons enhances the spatial resolution and feature extraction capability of the network, while maintaining the efficiency advantages of binary networks promises to enhance attention functions,

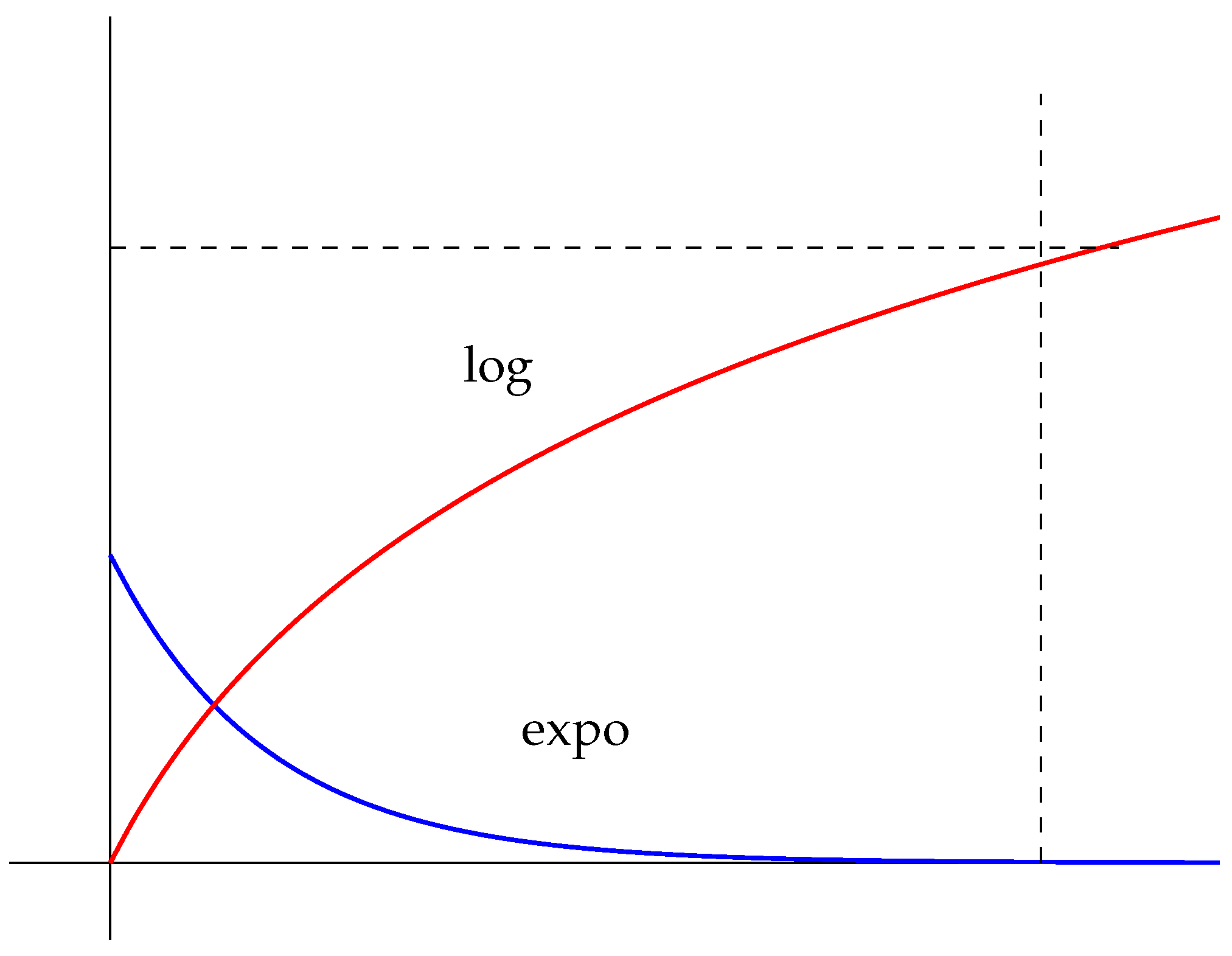

Dynamic stride adjustment operates by progressively reducing the stride from larger values to smaller ones as the network proceeds through its layers. Two decay functions are explored:

Exponential decay, which reduces the stride rapidly at first, capturing fine details earlier in the network’s operation.

Logarithmic decay, which offers a slower, more gradual decrease, allowing for more controlled refinement of the network’s feature extraction capabilities over time.

By utilizing these decay functions, we simulate the behavior of fractional strides typically seen in floating-point networks, but in a binary context, where such precise control over strides would otherwise be infeasible. This offers the flexibility needed to perform multiscale feature extraction without adding computational complexity, which is particularly advantageous in environments requiring low power and real-time processing.

A study on exponential decay by Fukaya et al., justified the adoption of an indefinite integral function to provide a theoretical foundation for continuous functionality of rapid image resolutions within an imposed limit based on a minimum stride as zero is approached asymptotically. The exponential decay estimate is proved as a theorem [8]. In their paper ’Exponential Decay Estimates and Smoothness of the Moduli Space of Pseudoholomorphic Curves’, Theorem 6.4 on page 42 provide a foundation to simplify the stride function into a prospective engineered component of an experimental neural network design.

In regards to logarithmic decay, the study developed function that gradual increase image resolution over time, opposite of the rapid function of exponential decay. The use of a minimum stride is still critical within the scope of the experiment, even if the function rate of decay is gradual instead of a rapid zoom effect on the image. In the paper ’On the Stieltjes Approximation Error to Logarithmic Integral’ by Gomez et al., determines the optimal truncation point of the asymptotic approximation series [9], which allowed for the development of the indefinite integral approach. The minimum stride limit would serve as the optimal truncation point to avoid potential failures of the function as the asymptotic function continues numerical reduction.

1.3. Binary Neural Networks and Applications

Binary neural networks (BNNs) are well-suited for resource-limited systems, including applications in edge computing, embedded systems, and real-time processing where energy efficiency is crucial. In BNN, all layers are binarized except the first and the last layers to keep the model accurate. BNN uses simple binary operations instead of the complex operations used in the full-precision counterpart [10]. By binarizing weights and activations, these networks can drastically reduce both memory usage and computation, allowing them to run on low-power device. One example is inefficient resource allocations, the numbers of channels or depths of blocks that may not be configured properly to meet their real needs [ 6 ]. However, binary ANNs are often seen as inferior in tasks requiring high precision, particularly when it comes to capturing subtle patterns or fine details in input data.

This approach to dynamic stride adjustment addresses limitations. Due to the inaccurate gradients and lower fitting ability, the training phase of BNNs requires more iterations than full-precision networks to reach convergence [11]. Simulating fractional strides potentially enables binary networks to extract features more effectively as broad implications for applications in computer vision, such as anomaly detection, segmentation, and image super-resolution where capture granular spatial details is essential.

In parallel, this method has potential applications in autonomous systems, particularly in domains like autonomous spacecraft navigation and hazard detection, where efficiency, adaptability, and low power consumption are critical. However, there is a trad-off between BNN’s accuracy and hardware effiiency [12]. Space missions, which demand highly efficient, real-time processing with minimal power consumption, would benefit from such an approach, modifying components of the BNN’s architecture. This method can be applied to autonomous systems, particularly in domains like autonomous spacecraft navigation, where efficiency, adaptability, and low-power consumption are critical. Space missions, which demands highly efficient real-time processing with minimal power consumption, would benefit from such an approach. Autonomous spacecraft systems require low-latency decision-making for tasks such as terrain mapping, object tracking, and anomaly detection. Dynamic stride methods offers a balance between high-resolution feature extraction, making it promising for space exploration research.

1.4. Contribution and Paper Outline

In this paper, we present a novel approach to simulating fractional stride decreases in BNNs using dynamic stride adjustment based on exponential and logarithmic decay. The mathematical function describes the time-dependent decay of stability coefficients as it tests whether stability asymptotically approaches zero or a nonzero value across long test-retest intervals [13]. We conduct comparative experiments using synthetic data to explore the impact of each decay function on the network’s ability to extract spatial details and adapt to varying input scales. Our contributions include:

A detailed formulation of exponential and logarithmic stride decay functions to simulate fractional strides in binary ANNs.

An attention mechanism integrated into the network to emphasize important spatial regions during feature extraction, enhancing the quality of the output feature maps.

A comparative analysis of the two decay methods, exploring their trade-offs in terms of resolution growth and computational overhead.

Application insights into areas such as computer vision tasks and autonomous spacecraft systems, highlighting the flexibility and adaptability of dynamic stride adjustment for energy-efficient ANN design.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: It provides a background on binary ANNs and related work on fractional strides and dynamic stride mechanisms; presents the mathematical framework for exponential and logarithmic decay functions, including an interpretation using indefinite integrals; describes the experimental setup and the results obtained from comparative testing; discusses the implications of our findings and potential applications. Finally, insights on future directions for this research will be presented.

2. Literature Review

The paper by Meng et al. addresses the issue of fractionally-strided convolutions (FSC) in terms of hardware inefficiencies, specifically focusing on the problem of zero-spacing in feature maps when implemented on FPGAs. Fractionally Strided Convolution operation, when expressed as matrix multiplication, introduces additional zero-insertions within the features and zero-paddings on the edge of the feature maps [1]. Their solution involves a hardware-algorithm co-design that eliminates redundant computations caused by zero-insertions using methods like kn2row and pipeline optimizations. In contrast, our approach focuses on improving the algorithmic efficiency of binary artificial neural networks (ANNs) by introducing a dynamic stride adjustment mechanism based on exponential and logarithmic decay functions, simulating fractional strides without increasing network complexity. While both methods aim to optimize fractional stride behavior, theirs is specific to FPGA hardware accelerators, whereas our approach is more generalized and applies to binary networks across different platforms. Despite this difference, both methods share a focus on improving efficiency, with their work targeting hardware utilization and ours focusing on enhancing feature extraction in binary networks. While the paper’s focus on hardware co-design may appear more complex, it is tightly bound to specific hardware limitations, whereas our method is more adaptable across various systems. In summary, both approaches address fractional stride efficiency from different levels, with theirs focused on hardware optimization and ours on network-level adaptability.

The paper, Dynamic Neural Networks: A Survey, written by Han et al., primarily focuses on dynamic neural networks that adapt their architectures or parameters in response to input data. The authors review three main types: sample-wise, spatial-wise, and temporal-wise dynamic networks. The recent research on neural architecture searh (NAS) further speeds up the process of designing more powerful structures [2]. These dynamic networks are shown to improve efficiency, adaptability, and representation power by adjusting computation based on the complexity of the input. This contrasts with our approach, where the focus was on simulating fractional stride decreases in binary artificial neural networks using exponential and logarithmic decay functions. While their work broadly covers dynamic computation at multiple levels, including early exiting and layer skipping for adaptive depth, our work specifically targets enhancing feature extraction by simulating fractional strides to improve spatial resolution in binary ANNs. Although both approaches aim at computational efficiency, theirs is a more general review of dynamic models, while ours is focused on binary networks with dynamic stride adjustment as a novel mechanism for multi-scale feature extraction. The surveyed methods could potentially complement our approach by offering dynamic adjustment at other levels such as network depth or width. The focus remains primarily on stride decay for feature enhancement.

The paper Learning Strides in Convolutional Neural Networks, by Riad et al. introduces DiffStride, a downsampling layer that learns stride values through backpropagation. The nature of strides as hyperparameters –rather than trainable parameters –hinders the discovery of convolutional architectures and learning strides by backpropagation would unlock a virtually infinite search space [3]. Their method allows strides to be trainable parameters instead of fixed hyperparameters, which are typically optimized through cross-validation. This contrasts with our approach, where we use dynamic stride adjustment via exponential and logarithmic decay functions to simulate fractional strides in binary artificial neural networks (ANNs). While both methods aim to improve flexibility and efficiency in convolutional layers, their approach emphasizes learning stride values to adapt to tasks, whereas ours focuses on progressively reducing stride values over time to enhance feature extraction in binary networks. The paper’s solution targets optimizing downsampling for tasks like audio and image classification, which could complement our method, but it adds complexity by learning strides through backpropagation and regularization, whereas our approach is simpler and predefined.

The paper Smart Camera Aware Crowd Counting via Multiple Task Fractional Stride Deep Learning, by Tong et al., focuses on improving crowd counting using smart cameras by leveraging a combination of dilated convolutions and fractional stride convolutions (FSC). Their model, CAFN, addresses issues of reduced resolution and feature loss in downsampling by applying fractional stride layers to up-sample and restore spatial details in crowd density maps. The traditional methods are hampered in dense crowds, and the performance is far from expected [4] They also extend this method to a multi-task learning framework (MTCAFN) for both crowd density regression and classification. In contrast, our approach targets general binary artificial neural networks (ANNs), using dynamic stride adjustments through logarithmic and exponential decay functions to simulate fractional strides for fine-grained feature extraction in a resource-efficient manner. While both methods deal with fractional stride convolutions, their focus is on enhancing crowd counting for smart surveillance systems, whereas our work emphasizes adaptability and computational efficiency in binary neural networks without the specific application focus on surveillance.

The paper How to Avoid Zero-Spacing in Fractionally-Strided Convolution: A Hardware-Algorithm Co-Design Methodology by Meng et al., focuses on optimizing fractionally-strided convolutions (FSC) by addressing inefficiencies caused by zero-padding in upsampling processes. The challenge of hardware under-utilization due to zero-spacing is especially severe in layers with large kernels and high strides, which are common in the early layers of down-sampling CNNs and all the up-sampling (decoding and generative) CNNs [1]. Therefore, the authors introduce a novel kn2row algorithm that eliminates zero-computations in FSC, significantly improving hardware utilization on FPGA platforms. The approach contrasts with our work, which leverages logarithmic and exponential decay functions to simulate fractional strides within binary artificial neural networks (ANNs). While both methods aim to optimize fractional strides, their focus on hardware efficiency for specific platforms, such as FPGAs, differs from our algorithmic approach aimed at improving feature extraction resolution in a resource-constrained binary network. Fundamentally, our method is more generalized and applicable across different architectures, as their approach is hardware-centric, offering targeted improvements for FPGA-based implementations. Despite these differences, both methodologies contribute to reducing computation inefficiencies, although in fundamentally different domains—hardware optimization versus network design.

3. Mathematical Foundation of Dynamic Stride Adjustment

3.1 Stride in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

In traditional CNNs, the stride determines how far the convolutional filter moves over the input data. For a given stride S, the filter shifts by S units in each vector, controlling the spatial resolution of the output feature map. Larger strides reduce the feature map size, leading to faster computation but finer feature extraction, while smaller strides increase resolution but come at a higher computational cost. In the past few years, numerous studies have been carried out to narrow the accuracy gap between BNN and its corresponding floating-point CNN using various optimization strategies, including minimizing the quantization error, improving the network loss function, and reducing the gradient error [14]. In BNN’s, strides are typically constrained to positive integer values, which limits their adaptability in capturing fine details. To overcome this, we introduce dynamic stride adjustment, where the stride decreases over time, simulating fractional strides and enhancing the network’s ability to extract multi-scale features.

Figure 1.

The logarithmic and exponential decay curves.

Figure 1.

The logarithmic and exponential decay curves.

3.2 Dynamic Stride Adjustment

The dynamic stride adjustment mechanism allows the stride to decrease with each layer or step n. Two decay functions—exponential and logarithmic—are used to control the rate at which the stride decreases. This approach potentially enables the network to progressively capture finer spatial details without the need for deeper layers or more neurons.

3.2.1 Exponential Decay Function

The exponential decay function for stride is defined as:

Where:

is the stride at step n.

is a decay constant controlling how quickly the stride decreases.

ensures that the stride does not fall below a certain threshold.

The exponential decay function ensures that the stride decreases rapidly at first, capturing finer details earlier in the network, and asymptotically approaches the minimum stride over time.

3.2.2 Logarithmic Decay Function

The logarithmic decay function is defined as:

Where:

Logarithmic decay results in a slower and more controlled decrease, allowing the stride to adapt gradually as the network deepens, leading to more stable feature extraction.

3.3 Indefinite Integral Interpretation

The behavior of the dynamic stride adjustment can be interpreted using indefinite integrals. For the exponential decay:

This integral shows that as , the cumulative effect of stride decay approaches a constant, ensuring the stride asymptotically approaches zero but never reaches it. Asymptote always refers to a line that is approached by points on a branch of a curve as x or y becomes unbounded. [15]. This is why the minimum stride limit was added to the function to prevent runaway decaying which can potential compromise results.

For logarithmic decay, the integral is:

While this integral does not have a simple closed form, it represents the gradual accumulation of stride changes, with a slower rate of decay compared to exponential. The reason for utilizing an indefinite integral for the theory is the allow for experiments without minimum stride in computer graphical experimental test, which potentially allows for infinite decay.

3.4 Simulating Fractional Strides

Since binary networks operate with discrete values, directly implementing fractional strides is not feasible. Instead, we simulate fractional strides by upsampling the input. The upsampling factor is derived from the inverse of the stride:

This allows the input feature map to be enlarged, mimicking the effect of fractional strides and enabling the network to capture finer spatial details. Osborne et al.,paper ’Upsampling Monte Carlo neutron transport simulation tallies using a convolutional neural network’ states he potential for deep learning based upsampling for accelerating reactor simulations, however, has not been explored [16]. This approach is beyond the scope of this experiment, yet future research on the integration of these functions with a BNN requiring a method of upsample factor. However, the success of this experiment allows for further experimentation.

3.5 Attention Mechanism

To further enhance feature extraction, an attention mechanism is applied after each convolutional layer. Methods for diverting attention to the most important regions of an image and disregarding irrelevant parts are called attention mechanism [17]. The attention mechanism uses global average pooling to capture important spatial regions, followed by a 1x1 convolution and a sigmoid activation to generate attention weights. These weights are applied to the feature maps, emphasizing important areas and improving the network’s focus during feature extraction.

4. Logarithmic Stride Function Test

The first experiment evaluates the behavior of a small convolutional model with a logarithmic stride decay function. The test was designed to demonstrate the output size grows as the stride decays logarithmically over time. Incremental increases in the number of steps allowed for the observation of the progression of the model’s attention on finer details.

4.1. Setup and Parameters

In this experiment, the model applies a dynamic stride based on the following logarithmic decay function:

where

represents the stride at step

n, the scale factor controls the rate of decay, and the minimum stride is set to avoid extremely small values. For this test, the input consists of synthetic data of size

(representing a batch of 4 images, each with 3 channels and

resolution). The convolution kernel size is

, and the stride decays with each step.

4.2. Results

Table 1 summarizes the output sizes for different steps. The model demonstrates a steady increase in output size as the stride decays logarithmically. The results show that the output size grows significantly during the first 10 steps, after which the growth rate decreases as the stride approaches the minimum threshold.

4.3. Analysis

The results demonstrate that the logarithmic decay function allows the model to progressively focus on finer details by increasing the output resolution. The most substantial growth occurs within the first 10 steps, where the output size increases rapidly. Beyond step 10, the output size continues to grow, but at a slower rate, indicating that the stride approaches the minimum stride value asymptotically.

This behavior is consistent with the nature of logarithmic decay, where the stride decreases sharply in the early steps and then slows down. The model continues to refine its feature maps, but with diminishing returns in terms of output size growth beyond step 20.

Key observation: The logarithmic stride function proves effective for tasks where progressively finer detail extraction is necessary. However, beyond a certain step count (around step 20), the growth in output size slows significantly, potentially making additional steps less effective in terms of resolution improvement.

5. Exponential Stride Function Test

In this experiment, we evaluate the behavior of a small convolutional model with an exponentially decaying stride function. In, observation, the output size changes as the stride decreases exponentially over time, leading to rapid growth in output resolution at early steps. Further observation found that the output size stabilizes at after a certain number of steps.

5.1. Setup and Parameters

The dynamic stride function follows the form:

where

represents the stride at step

n. As in the logarithmic decay test, the input consists of synthetic data of size

(representing a batch of 4 images, each with 3 channels and

resolution). The convolution kernel size is

, and the stride decays exponentially over successive steps.

5.2. Results

Table 2 presents the output sizes at various steps. In this experiment, the output size grows quickly at the beginning, as the exponential decay in stride leads to large increases in the spatial resolution. Beyond step 20, the output size reaches the upper limit of

, which is determined by the input size and the minimum possible stride.

5.3. Analysis

The results highlight the behavior of the exponentially decaying stride function. Initially, the stride decays rapidly, leading to a significant increase in the output size. For instance, the output grows from at step 1 to by step 10. By step 20, the output reaches , and after step 25, it stabilizes at , which is the maximum size that can be achieved with the given input.

Why the output size stops growing: The output size stabilizes at because the input size () and the minimum stride value limit the extent to which the model can upsample the input. As the stride reaches the minimum threshold, the upsampling factor no longer increases, causing the output size to plateau at the maximum possible resolution for this input size. This behavior is a natural consequence of the upsampling process, which is constrained by the resolution of the input data.

This rapid increase in output size reflects the nature of exponential decay, where the stride quickly approaches the minimum stride value. Once the minimum stride is reached, further increases in step count no longer affect the output size, resulting in the plateau observed in steps 25 to 30.

Key observation: The exponential stride function allows for fast resolution growth, making it ideal for tasks that require quick focusing on finer details. However, as the stride reaches its minimum, the output size stabilizes, and additional steps become less effective.

6. Discussion

The experimental results from both the logarithmic and exponential stride function tests provide key insights into how dynamic stride manipulation can impact neural network design, specifically in the context of attention mechanisms and artificial cognitive systems. Both functions offer potential advantages in terms of how they progressively refine spatial resolution, but they also exhibit limitations in terms of computational efficiency and scalability.

6.1. Logarithmic vs. Exponential Stride Behavior

The two stride functions demonstrate different growth patterns and rates of change in output size:

Logarithmic Decay: In the logarithmic stride function, the output size grows gradually, with more significant changes occurring in the early steps and slower growth as the stride approaches its minimum value. This behavior is advantageous for tasks that require a more conservative, fine-grained focus over time. The logarithmic function allows the network to slowly zoom in on details, which may be beneficial in scenarios where gradual feature extraction is crucial, such as in progressive learning or multi-stage image processing tasks.

Exponential Decay: The exponential stride function, in contrast, results in rapid growth in output size, particularly in the early steps. This function quickly increases the resolution, allowing the model to focus on finer details much faster. While this is useful for tasks requiring rapid feature refinement, the output size stabilizes once the stride reaches its minimum threshold. The exponential function is ideal for applications where a fast and aggressive resolution increase is needed, but it also demonstrates diminishing returns in terms of detail extraction as it quickly reaches the maximum possible output size.

6.2. Implications for Artificial Neural Network Design

The results suggest that dynamic stride manipulation—whether logarithmic or exponential—can be an effective strategy for designing more flexible and adaptive neural networks. By controlling the rate at which the model focuses on finer details, these functions allow for better multi-scale feature extraction. In practice, this means that models can be designed to adaptively focus on coarse features in early stages and progressively zoom in on finer details, leading to more efficient learning and inference.

Hybrid Approaches: Future studies could explore hybrid stride functions, which combine both logarithmic and exponential behaviors to allow for both rapid and gradual resolution increases in different stages of the model’s operation. For example, an initial exponential stride decay could enable fast detail extraction, followed by a logarithmic decay for finer adjustments.

Computational Efficiency: One of the challenges highlighted by the experiments is the computational cost associated with increased output sizes, particularly in the exponential model where the output grows rapidly. Addressing this issue may involve introducing adaptive mechanisms that automatically adjust the stride based on the task complexity or computational resource availability. Such mechanisms could ensure that the model focuses on important features without overburdening computational resources.

6.3. Enhancing Attention Mechanisms

The coupling of dynamic stride functions with attention mechanisms offers significant potential for improving attention focus in artificial neural networks. The attention mechanism, acting as a spotter, benefits from the increased resolution provided by stride decay. As the stride decreases, the attention mechanism can focus more effectively on smaller, finer details in the input.

Improved Feature Prioritization: With dynamic strides, attention mechanisms can prioritize features at varying resolutions, making the network more adaptable in environments where both coarse and fine details are important. For example, in object detection, the attention mechanism can first focus on general object boundaries and then progressively refine its focus to detect small details such as texture or edges.

Multi-Resolution Attention: Dynamic stride functions can lead to the development of multi-resolution attention mechanisms where attention dynamically adjusts based on the current level of detail. This opens up new possibilities for tasks requiring contextual awareness at multiple scales, such as anomaly detection, image segmentation, and even language processing in hierarchical data structures.

6.4. Artificial Cognitive Systems and Future Research

In artificial cognitive systems, where attention and adaptability are critical, dynamic stride functions represent a promising direction for improving cognitive focus. The ability to modulate stride based on input complexity mimics how human cognition focuses on coarse details before zooming in on finer aspects of a problem. Dynamic strides could enable artificial cognitive systems to handle multi-tasking environments more efficiently by dynamically adjusting their focus based on task importance or urgency.

Adaptive Cognitive Models: The findings suggest that neural networks in cognitive systems could be designed to self-regulate [18] their focus by dynamically adjusting strides in response to changing environmental stimuli. This would create more robust and responsive systems that can handle complex tasks without requiring human intervention to fine-tune stride parameters.

Dynamic Task-Specific Attention: Another area of future research involves combining dynamic strides with multi-task-specific attention mechanisms, where the network can determine which stride function (logarithmic or exponential) to apply based on the nature of the task. A common multi-task learning design is to have a large amount of parameters shared among tasks while keeping certain private parameters for individual ones [19]. For instance, for tasks requiring quick pattern recognition, exponential strides might be preferable, whereas for more detailed, iterative tasks, logarithmic strides could allow for slower, more deliberate feature extraction.

6.5. Challenges and Opportunities

While dynamic strides offer flexibility, they also introduce challenges, particularly in terms of computational complexity and model interpretability. The rapid growth in output size in the exponential model can lead to memory bottlenecks, especially in resource-constrained environments. Developing methods to optimize stride decay while maintaining computational efficiency will be critical for making these approaches practical in large-scale systems.

On the other hand, the potential for combining dynamic strides with reinforcement learning or self-supervised learning opens new avenues for creating truly adaptive systems. These systems could learn to adjust their stride functions autonomously based on performance feedback, further improving the efficiency and accuracy of attention mechanisms in artificial cognitive systems.

6.6. Resolution

The comparative analysis of logarithmic and exponential stride functions reveals that both approaches have unique advantages in enhancing feature extraction and attention mechanisms. Logarithmic strides provide gradual refinement of details, while exponential strides enable rapid zooming into features. By incorporating these functions into artificial neural networks, we can create more adaptive models capable of handling tasks at multiple scales with improved focus and attention. Further research into hybrid approaches, task-specific adjustments, and computational optimizations will be essential to fully realize the potential of dynamic stride functions in future artificial cognitive systems.

7. Conclusion

This study explored the potential of using logarithmic and exponential stride functions to dynamically manipulate the focus of attention mechanisms in artificial neural networks. The results demonstrate that both approaches offer distinct, yet potential advantages for refining feature extraction and improving attention-based processing. Theoretically, logarithmic function provides gradual, fine-grained refinement of details, while the exponential function enables rapid zooming into finer features, allowing networks to adjust their focus dynamically depending on the task at hand.

7.1. Future Studies in Artificial Neural Network Design

The findings from this study open the door for future experimental research aimed at integrating these dynamic stride functions into the design of artificial neural networks for cognitive systems. Future work should focus on experimenting with computer vision models, where logarithmic and exponential strides can be applied in tandem or sequentially to maximize the benefits of both approaches. Such experiments could explore how the dynamic adjustment of stride functions enhances the ability of artificial systems to mimic cognitive functions, such as attention shifting and adaptive learning.

Further studies should also investigate the application of reinforcement learning or self-supervised learning to dynamically adjust the stride functions during training. This would enable networks to autonomously regulate their focus based on task complexity, performance, or environmental stimuli, further advancing the field of adaptive cognitive models in artificial intelligence.

7.2. Application of Real Data in Computer Vision Tasks

While this study used synthetic data to validate the theoretical and experimental performance of dynamic stride functions, future research should aim to test these methods using real-world datasets, particularly in computer vision tasks. Potential applications include:

Object Detection and Recognition: Dynamic stride functions could be used to enhance object detection models by allowing the network to quickly focus on regions of interest and then progressively refine its focus on fine details, such as textures or edges. This would improve the model’s ability to detect small objects in cluttered scenes or identify specific features in high-resolution images.

Image Segmentation: By adjusting the stride to focus on different spatial scales, models could better identify and segment objects from the background, improving the accuracy of medical imaging, autonomous driving systems, or satellite imagery analysis.

Action Recognition and Tracking: In video analysis, dynamic strides could help networks focus on movement patterns, tracking objects across frames more effectively by dynamically adjusting resolution based on the motion’s scale and speed.

Real-world datasets such as ImageNet, COCO, and Cityscapes would provide a meaningful testbed for evaluating how well these models generalize and perform on complex, high-dimensional data, further validating their practical utility in computer vision.

7.3. Applications in Robotics for Environmental Awareness and Object Identification

The integration of dynamic stride functions into robotic systems presents an opportunity to enhance environmental awareness and improve the accuracy of object, area, and movement identification. In robotics, the ability to adaptively focus on different spatial resolutions is crucial for tasks like navigation, object manipulation, and human-robot interaction.

Environmental Awareness: Dynamic stride functions can help robots better understand and interact with their environment by adjusting their focus on different regions in the field of view. For instance, a robot could first identify general obstacles or landmarks in the environment and then focus more closely on the details of objects it needs to interact with, such as tools, components, or manipulatable items.

Object Identification: The use of dynamic strides could improve object recognition in dynamic and cluttered environments. As the robot navigates through an unknown space, it could rapidly detect and classify objects from afar using a coarse focus and then progressively refine its understanding of these objects as it approaches them.

Movement Detection and Tracking: In scenarios where detecting and tracking motion is critical, such as in surveillance, human-robot interaction, or autonomous vehicles, dynamic strides could allow the robot to adjust its focus on objects that are moving at varying speeds, enhancing its ability to track objects, avoid obstacles, or engage with moving targets.

Future studies should explore the integration of these stride functions into real-time robotic systems, using embedded sensors and cameras to capture environmental data. This would allow for real-world testing of the effectiveness of dynamic strides in improving robotic perception and interaction.

7.4. Synopsis

In conclusion, the study demonstrates the potential of logarithmic and exponential stride functions to improve attention mechanisms and feature extraction in artificial neural networks. Future work should focus on extending experimental designs to real-world spacecraft applications in computer vision and robotics, where dynamic focus is essential for tackling complex, multi-scale tasks. By integrating these methods into the design of cognitive systems and autonomous robots, researchers can push the boundaries of adaptive intelligence, enhancing both the efficiency and capability of artificial agents in diverse environments..

8. Patents

There are not patents pending for works reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Dr. Jonathan Lancelot, Assistant Professor of the Cyber Sciences at Dakota State University is the sole contributor.

Funding

No funding was awarded for this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable

Data Availability Statement

Synthetic tensor data from Pytorch Library was utilized for this study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dakota State University Beacom School of Computer and Cyber Sciences for challenging me to think outside the box, and to my parents Vincent and Norma.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meng, Y.; Kuppannagari, S.; Kannan, R.; Prasanna, V. How to Avoid Zero-Spacing in Fractionally-Strided Convolution? A Hardware-Algorithm Co-Design Methodology. IEEE 28th International Conference on High Performance Computing, Data, and Analytics, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Huang, G.; song, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Dynamic Neural Networks: A Survey. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riad, R.; Olivier, T.; Grangier, D.; Zeghidour, N. Learning Strides in Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.01653. [Google Scholar]

- Minglei, T.; Lyuyuan, F.; Hao, N.; Zhao, Y. Smart Camera Aware Crowd Counting via Multiple Task Fractional Stride Deep Learning. Sensor 2019, 19, 1346. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, S. Understanding Deep Learning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Qiao, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yuille, A. Neural Rejuvenation: Improving Deep Network Training by Enhancing Computational Resource Utilization. Computer Vision Foundation, IEEE 2019.

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xuming, H.; Muhammet, D. A review of convolutional neural network in computer. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukaya, K.; Yong-Geun, O.; Hiroshi, O.; Kaoru, O. Exponential Decay Estimates and Smoothness of the Moduli Space of Pseudoholomorphic Curves. arXiv 2024, arXiv:1603.07026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J. On the Stieltjes Approximation Error to Logarithmic Integral. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12152. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, R.; Azmi, H.; Shawkey, H.; Khalil, A.; Refky, M. A Systematic Literature Review on Binary Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 27546–27578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chu, X.; Ling, H. NAS-BNN: Neural Architecture Search for Binary Neural Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.15484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Bethge, J.; Yang, H.; Zhong, K.; Ning, X.; Meinel, C.; Wang, Y. Boolnet: Minimizing the Energy Consumption of Binary Neural Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.06991. [Google Scholar]

- Kuster, F.; Orth, U. The Long-Term Stability of Self-Esteem: Its Time-Dependent Decay and Nonzero Asymptote. University of Basel 2013. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Lei, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, W. HyBNN: Quantifying and Optimizing Hardware Efficiency of Binary Neural Networks. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2024, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunemacher, J. Asymptotes, Cubic Curves, and the Projective Plane. Mathematics Magazine, STOR 1999.

- Osborne, A.; Dorville, J.; Romano, P. Upsampling Monte Carlo neutron transport simulation tallies using a convolutional neural network. Energy and AI, Elsevier 2023.

- Guo, M.; Xu, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Jiang, P.; Mu, T.; Zhang, S.; Martin, R.; Cheng, M.; Hu, S. Attention mechanisms in computer vision: A survey. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 331–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Pan, Y.; Pan, X.; Hoi, S.; Yi, Z.; Xu, Z. RegNet: Self-Regulated Network for Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 9562–9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, I.; Vu, T.; Charette, R. Cross-task Attention Mechanism for Dense Multi-task Learning. Computer Vision Foundation 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).