Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study presents a predictive maintenance system designed for industrial IoT environ- 1 ments, focusing on resource efficiency and adaptability. The system utilizes Nicla Sense ME sensors, 2 a Raspberry Pi-based concentrator for real-time monitoring, and an LSTM machine-learning model 3 for predictive analysis. Notably, the LSTM algorithm is an example of how the system’s sandbox 4 environment can be used, allowing external users to easily integrate custom models without altering 5 the core platform. In the laboratory, the system achieved a Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 6 0.0156, with high accuracy across all sensors, detecting intentional anomalies with a 99.81% accuracy 7 rate. In the real-world phase, the system maintained robust performance, with sensors recording 8maximum Mean Absolute Errors (MAE) of 0.1821, an R-squared value of 0.8898, and a Mean Absolute 9 Percentage Error (MAPE) of 0.72%, demonstrating precision even in the presence of environmental 10 interferences. Additionally, the architecture supports scalability, accommodating up to 64 sensor 11 nodes without compromising performance. The sandbox environment enhances the platform’s 12 versatility, enabling customization for diverse industrial applications. The results highlight the 13 significant benefits of predictive maintenance in industrial contexts, including reduced downtime, 14 optimized resource use, and improved operational efficiency. These findings underscore the potential 15 of integrating AI-driven predictive maintenance into constrained environments, offering a reliable 16 solution for dynamic, real-time industrial operations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The development and deployment of Concentrator in a real-world industrial setting.

- Customization capabilities for integrating specific sensors and algorithms.

- The application of LSTM models to enhance predictive maintenance and reduce downtime.

2. State of Art

- Model Pruning and Quantization: Reducing the size of the LSTM model through pruning unnecessary parameters and applying quantization techniques helps decrease the memory footprint and computational load, making the model more suitable for embedded systems [47].

- Knowledge Distillation: This involves training a smaller, less complex model (student model) to mimic the behavior of a larger, more complex LSTM model (teacher model). The smaller model can then be deployed on resource-constrained devices without significant loss of accuracy [48].

- Hardware Acceleration: Utilizing specialized hardware, such as Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) or Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), can significantly accelerate the computation of LSTM models on embedded devices, enabling real-time processing [49].

- Edge AI Frameworks: Using edge AI frameworks like TensorFlow Lite or ONNX Runtime helps convert and optimize LSTM models for execution on embedded systems, ensuring efficient performance while maintaining high accuracy [50].

3. Methodology and Architecture

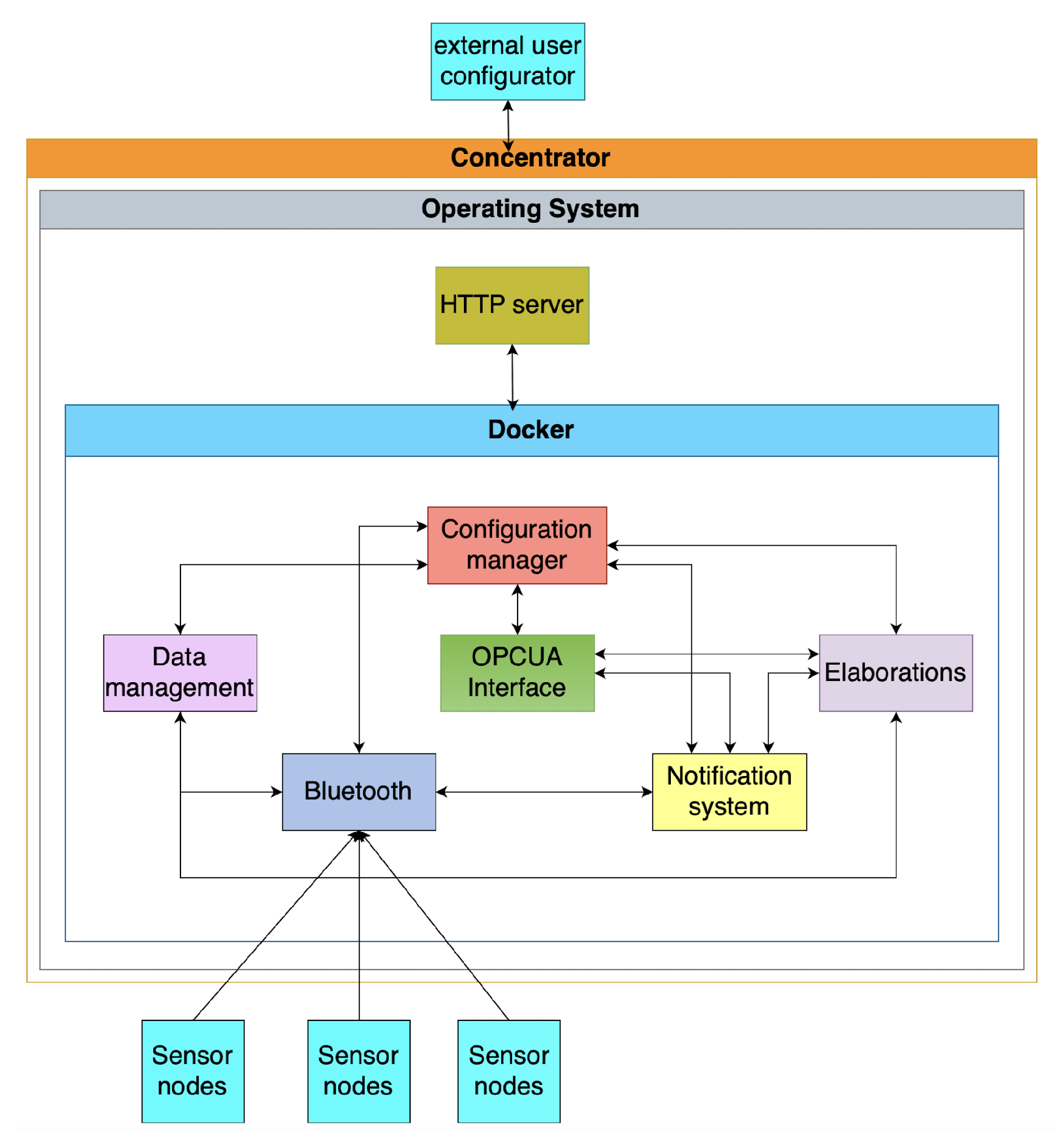

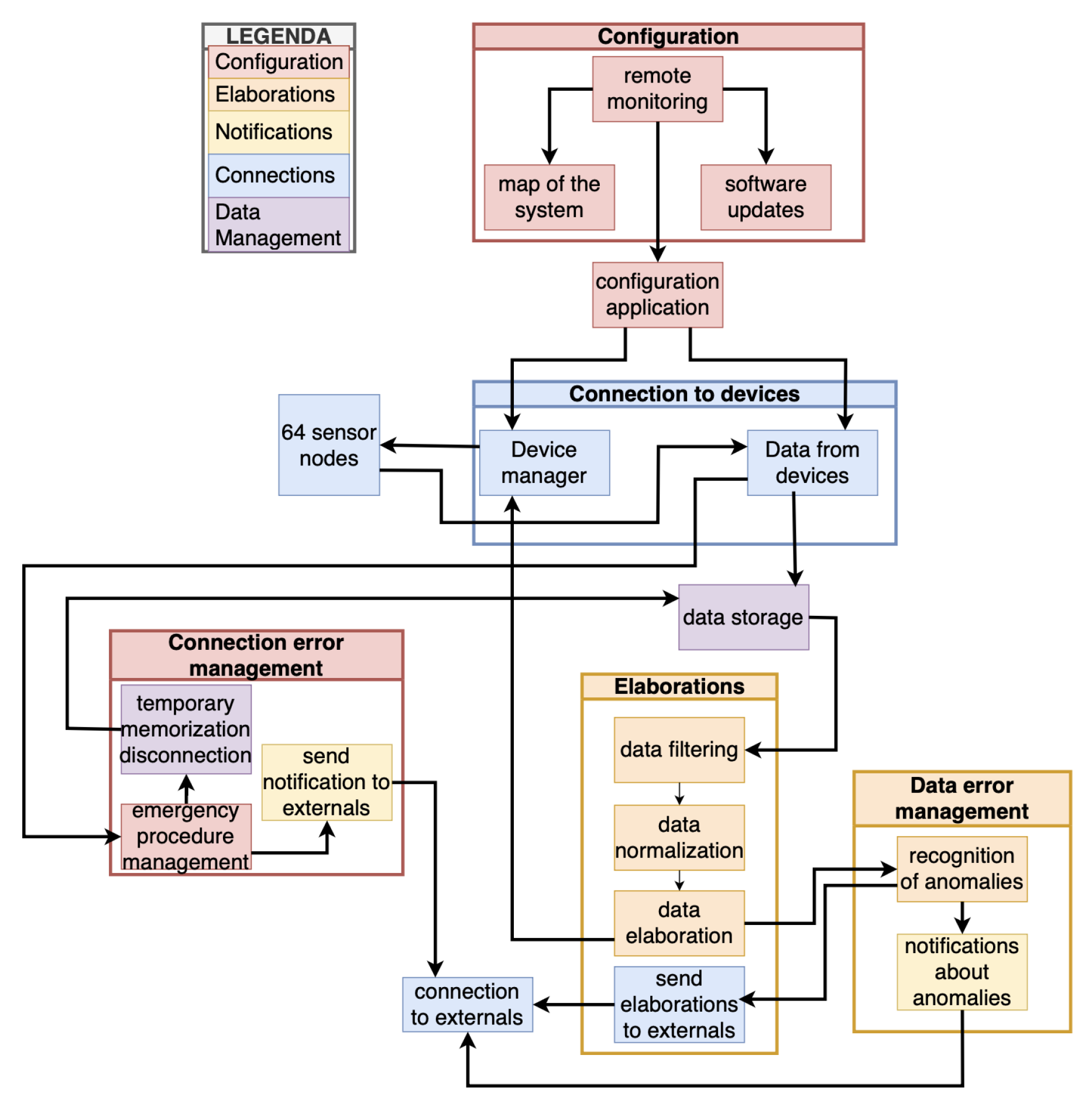

3.1. The Native System

- -

- UC.1: wireless data retrieval from sensors and devices

- -

- UC.2: versatile handling of process data from AROL and external systems

- -

- UC.3: rigorous technical data processing for real-time monitoring and optimization

- -

- UC.4: prompt anomaly detection with effective user notification

- -

- UC.5: multi-device connectivity for holistic monitoring

-

Protocols requirementsThe Concentrator system employs robust communication protocols tailored for seamless interaction with IoT and operational technology (OT) systems in industrial settings. For IoT device communication, it utilizes wireless connectivity, supporting protocols like Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) version 4.0 and Wi-Fi. The Wi-Fi capability enables transmission using various protocols such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP), and Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) [55]. Notably, the platform handles multiple connections from IoT devices, handling connection establishment, maintenance, and termination while automatically reconnecting during temporary disruptions. While communication with OT systems is pending development, the Concentrator will interface with Modbus Transmission Control Protocol (Modbus/TCP) and OPC Unified Architecture (OPCUA) protocols, facilitating data exchange with industrial automation devices such as Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems. Additionally, it features synchronization inputs for the temporal alignment of devices or actions, ensuring precise coordination within industrial processes. Moreover, potential integration of Ethernet-based protocols may be necessary to accommodate client-specific devices, highlighting the Concentrator’s adaptability to diverse industrial environments.

-

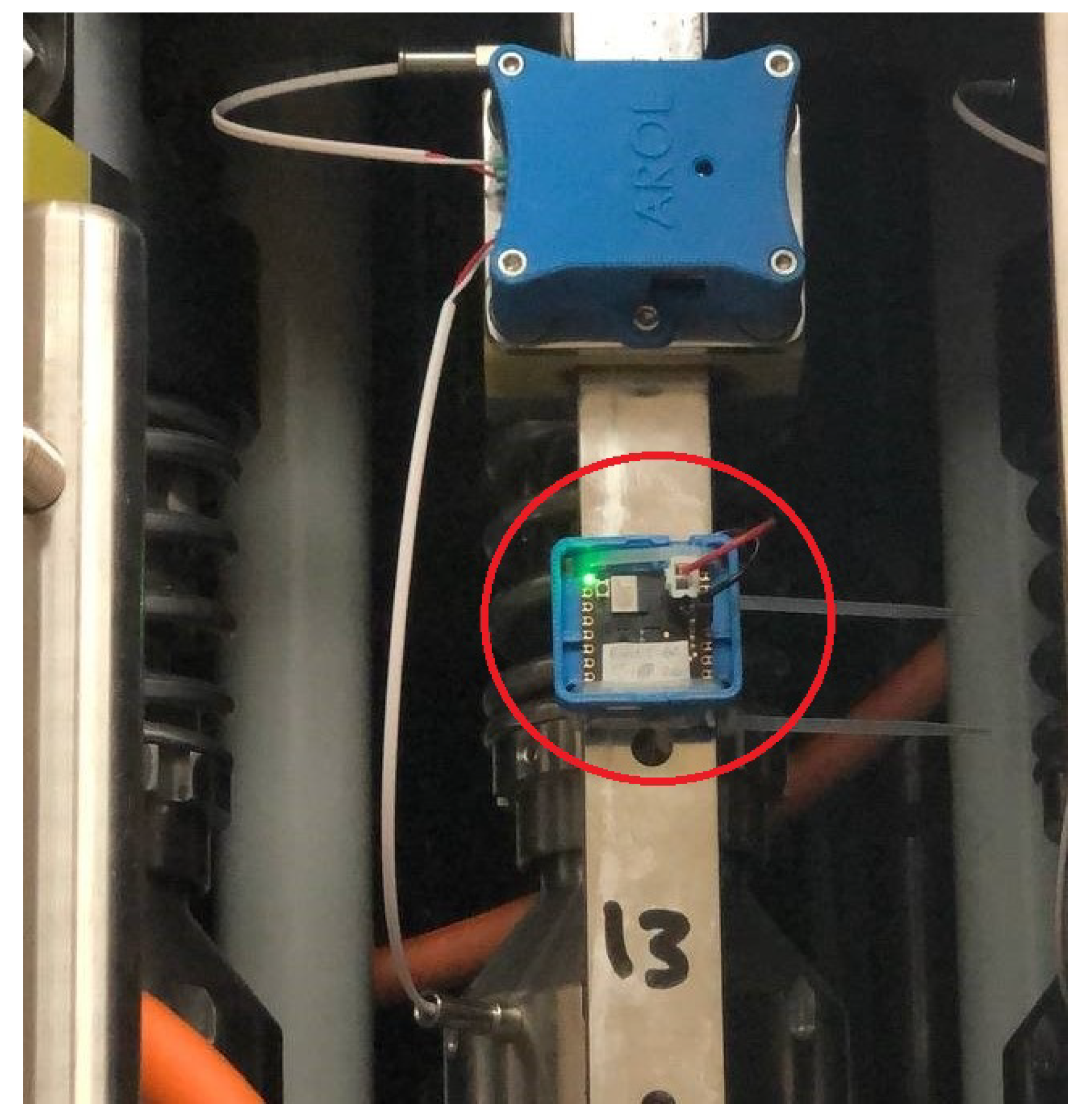

Functional requirementsThe Concentrator system has various functionalities essential to operate within industrial contexts. Firstly, the system addresses the platform power management requirement, including startup, shutdown, and configuration procedures. The Concentrator then establishes robust connections with various external systems regarding system communication. Notably, the Concentrator can communicate simultaneously with a maximum of 64 sensor node devices (usually mounted on a capping machine) while maintaining connectivity to additional devices as required. Moreover, to ensure future scalability and adaptability, compatibility with diverse IoT devices can be possible as long as the hardware limitations permit it.

-

Data ProcessingThe Concentrator system plays a crucial role in enhancing the quality and utility of data received from IoT devices. Initially, it performs preprocessing on data from IoT devices to ensure compatibility and efficiency before transmitting it to external systems. Depending on the user’s configuration, it also filters data based on specific criteria, potentially removing invalid, out-of-range, or non-compliant data to maintain data integrity and relevance. Additionally, the system aggregates data from various IoT devices to offer a comprehensive overview of collected information, aiding informed decision-making. It can also apply calibrations or normalizations to ensure data aligns with external system standards, improving interoperability.

-

Error ManagementThe Concentrator is responsible for robust error detection and mitigation to maintain operational reliability and data integrity. It identifies errors and anomalies like connection failures, transmission errors, out-of-range data, or invalid values. Once detected, the system communicates these errors via messages, system logs, or other notifications for timely intervention and resolution. Additionally, it can address critical errors through emergency procedures such as system shutdown or activating safety modes to prevent potential hazards. Moreover, the Concentrator supports temporary data storage during system disconnection, ensuring uninterrupted data transmission upon reconnection.

-

Cybersecurity and Updates and MaintenanceThe primary responsibility of the Concentrator is to authenticate IoT devices, ensuring that only authorized devices can communicate with the network. This authentication process is pivotal in safeguarding sensitive data from unauthorized access, thereby preserving the confidentiality and integrity of the system. Moreover, the platform manages data access dynamically, preventing potential data breaches and ensuring that only permitted users or devices can interact with sensitive information.In addition to authentication and access control, the system supports remote administration and monitoring, enabling the continuous execution of system updates and maintenance. This capability ensures the platform remains up-to-date with the latest security patches, protecting it from emerging vulnerabilities. The system can proactively identify issues and optimize performance through remote monitoring, maintaining robust security and functionality. This approach to remote control also facilitates timely intervention for system enhancements and problem resolution, ensuring and introducing continuous security measures to address evolving cyber threats.

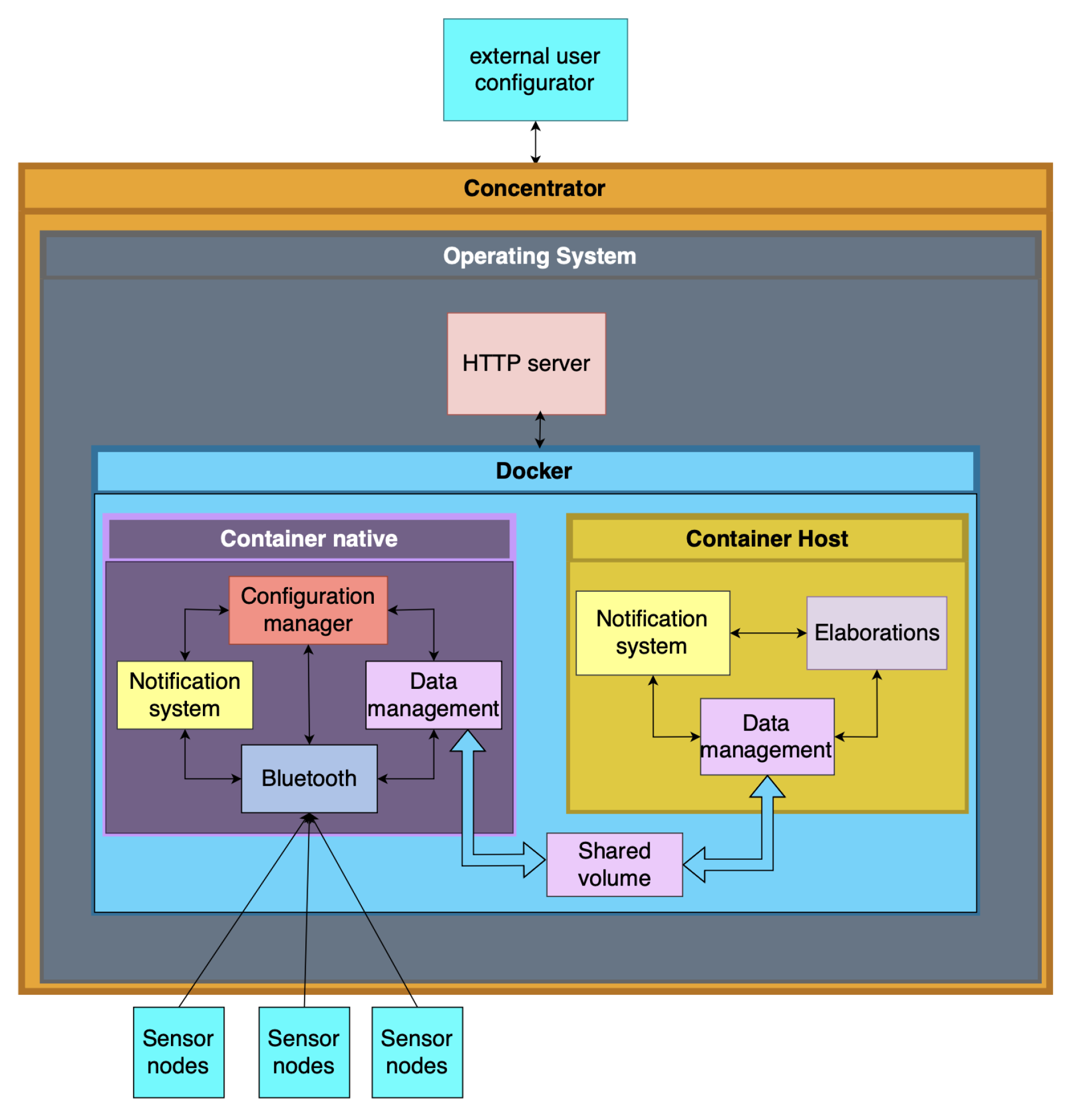

3.2. The Host System

-

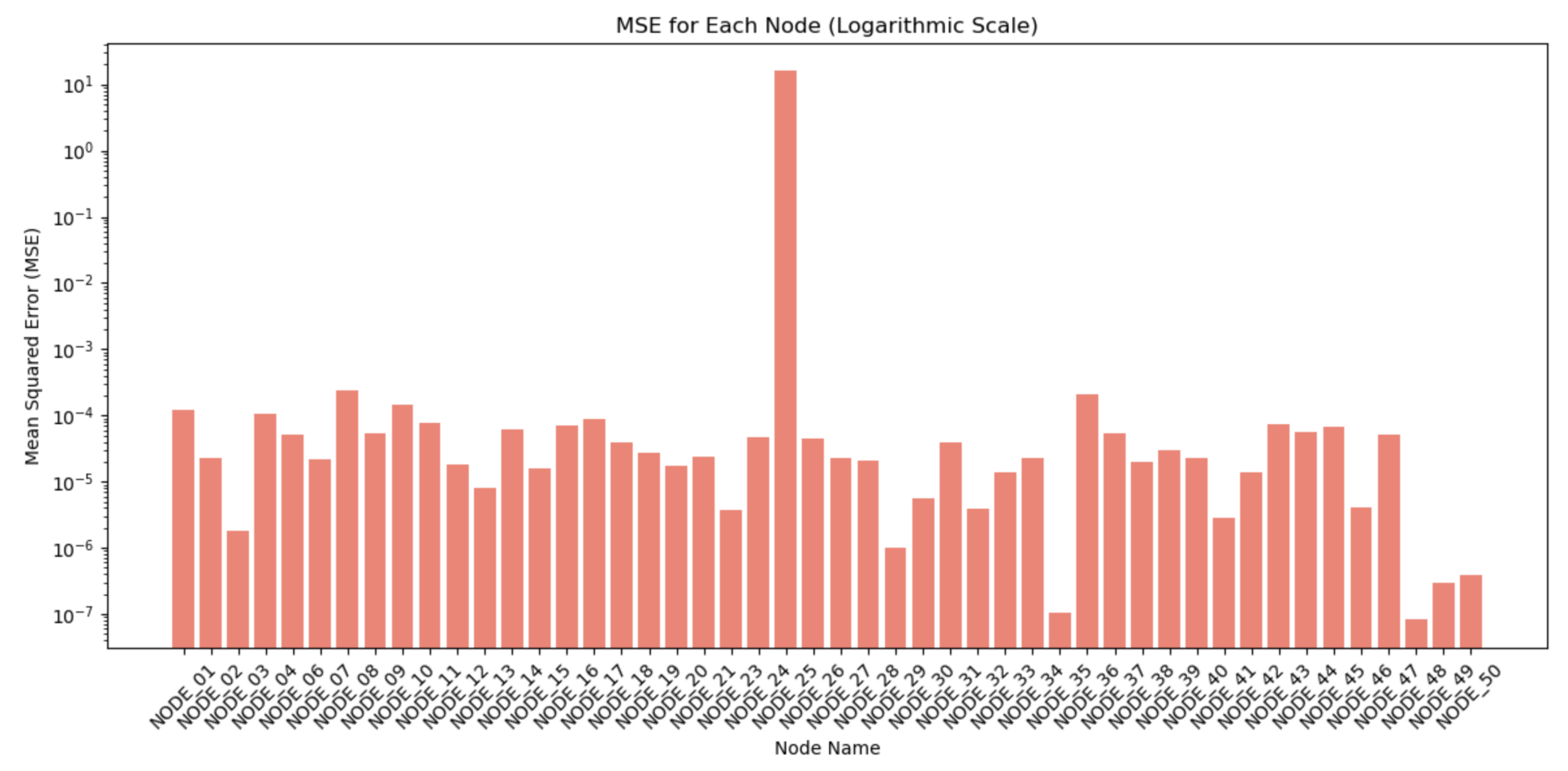

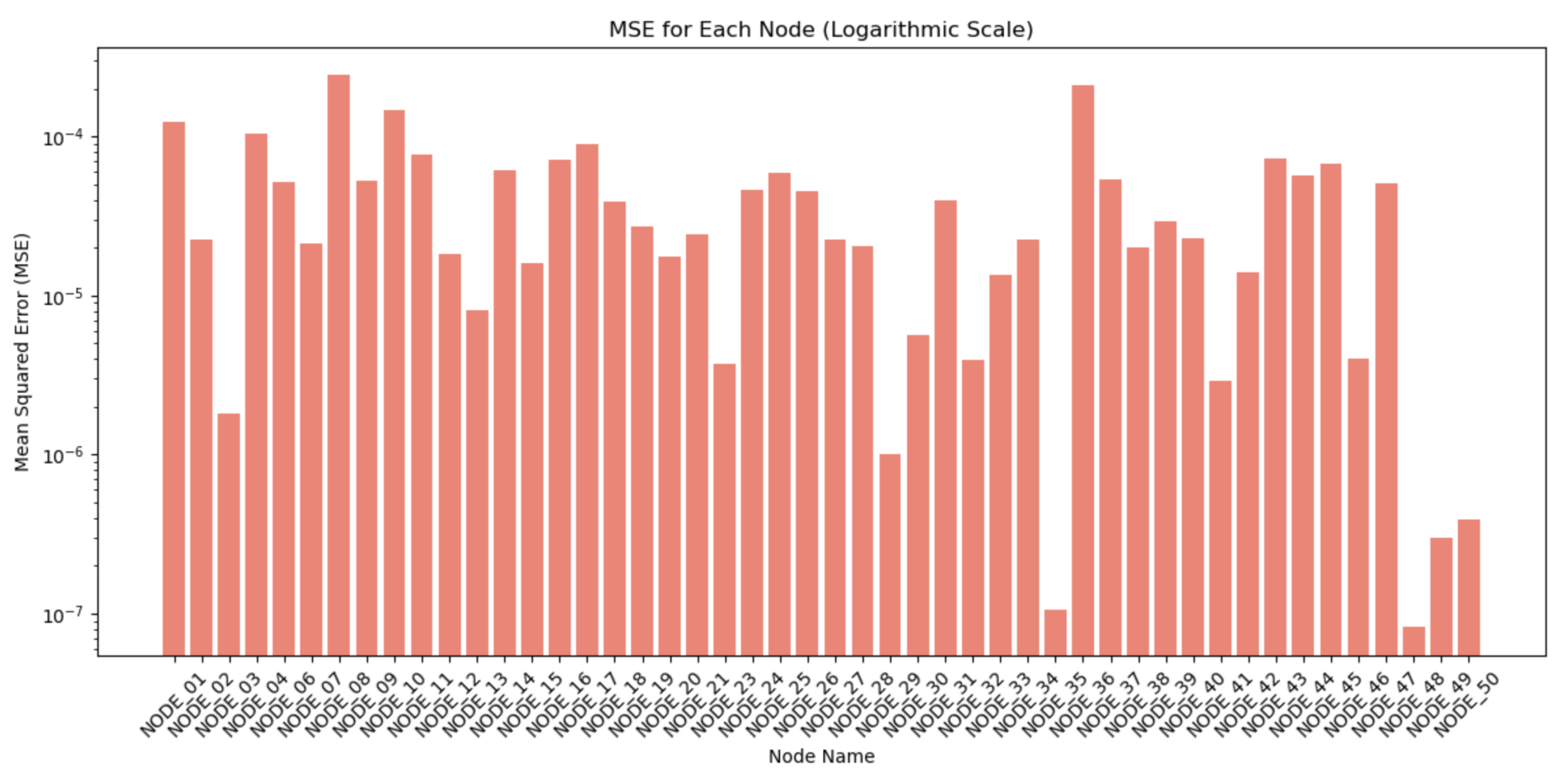

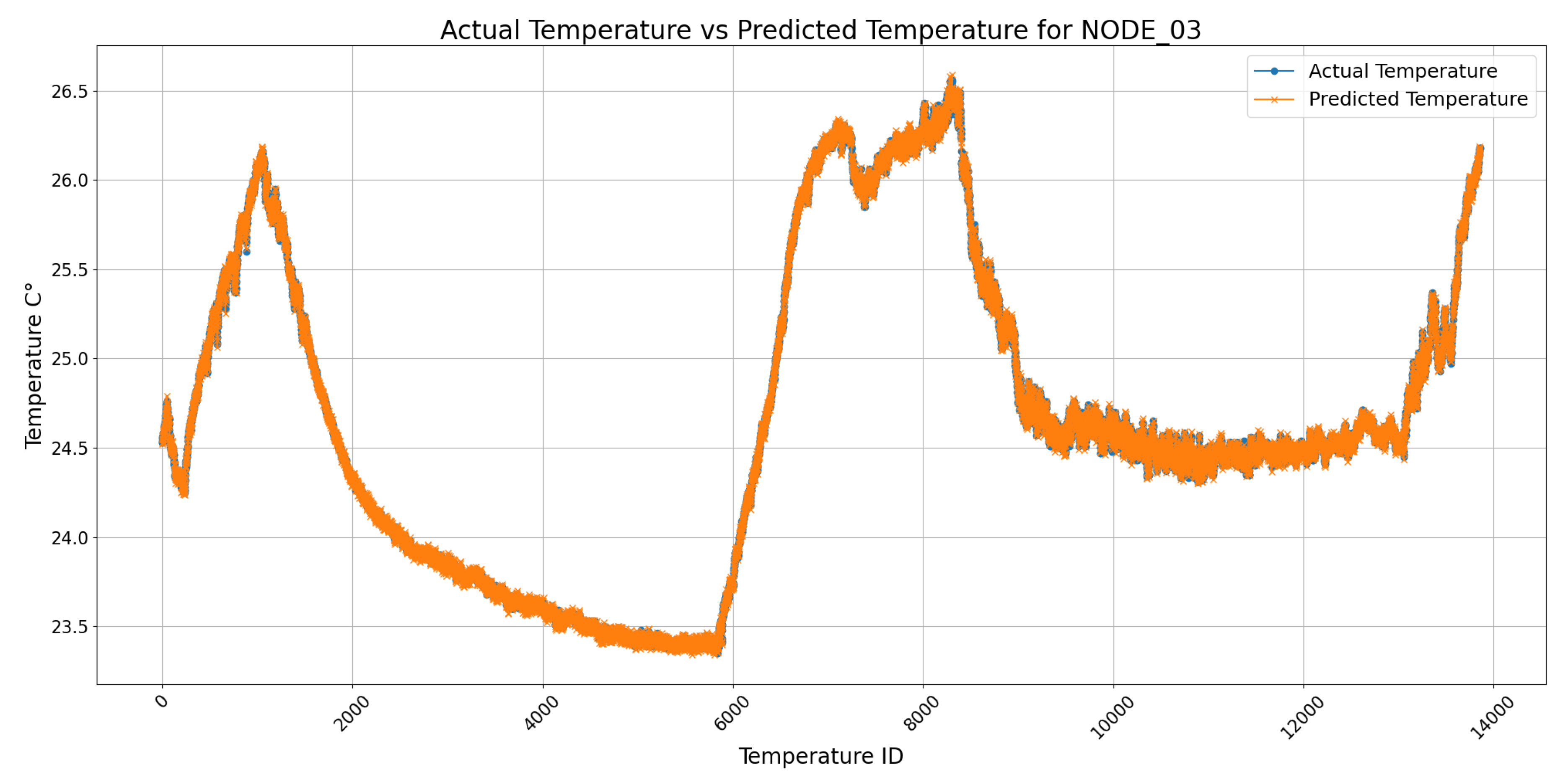

Model DevelopmentThe development of the LSTM-based temperature prediction model followed a systematic process involving data preprocessing, model architecture design, training, evaluation, and deployment. The primary goal was to predict future temperatures based on historical sensor data from multiple nodes while ensuring the model’s compatibility with edge devices such as the Raspberry Pi. The dataset consisted of over one million temperature readings from 50 sensor nodes stored in a CSV file. The dataset was then split into training, validation, and test sets using an 80-10-10 ratio. The data was normalized to a range of [0, 1] using MinMax scaling to enhance training efficiency.Sequences of 20-time steps were generated using a sliding window approach for time series modeling. Each sequence provided the input for the model to predict the temperature for the subsequent hour. This preparation enabled the LSTM model to capture temporal dependencies and patterns within the data.The LSTM model architecture was designed to balance predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. The model comprised two LSTM layers with 50 units capable of processing sequential input and capturing long-term dependencies inherent in the temperature data. Two Dense output layers, one with 50 neurons and one with a single neuron, were used to predict the temperature for the next hour. The input shape for the model was defined as , where represents the number of historical time steps (20) and corresponds to the number of sensor nodes. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with a root mean squared error (RMSE) loss function.The training process was conducted over 20 epochs with a batch size of 30. Early stopping was implemented with a patience of 5 epochs to mitigate overfitting by halting training when the validation loss ceased to improve. Model performance was evaluated on the test set, with root mean squared error (RMSE) as the primary metric for assessing prediction accuracy, obtaining a result of 0.1838, and a prediction time of approximately 200 ms.Following training, the model was prepared for deployment on edge devices. The trained LSTM model was saved in TensorFlow’s SavedModel format and converted to TensorFlow Lite format using the TFLiteConverter. The TensorFlow Lite interpreter validated the converted model’s performance, ensuring compatibility and consistent predictions.This structured approach enabled the LSTM model to leverage the computational capabilities of the Raspberry Pi effectively, providing robust and scalable temperature forecasts while adhering to the constraints of resource-constrained edge environments.

-

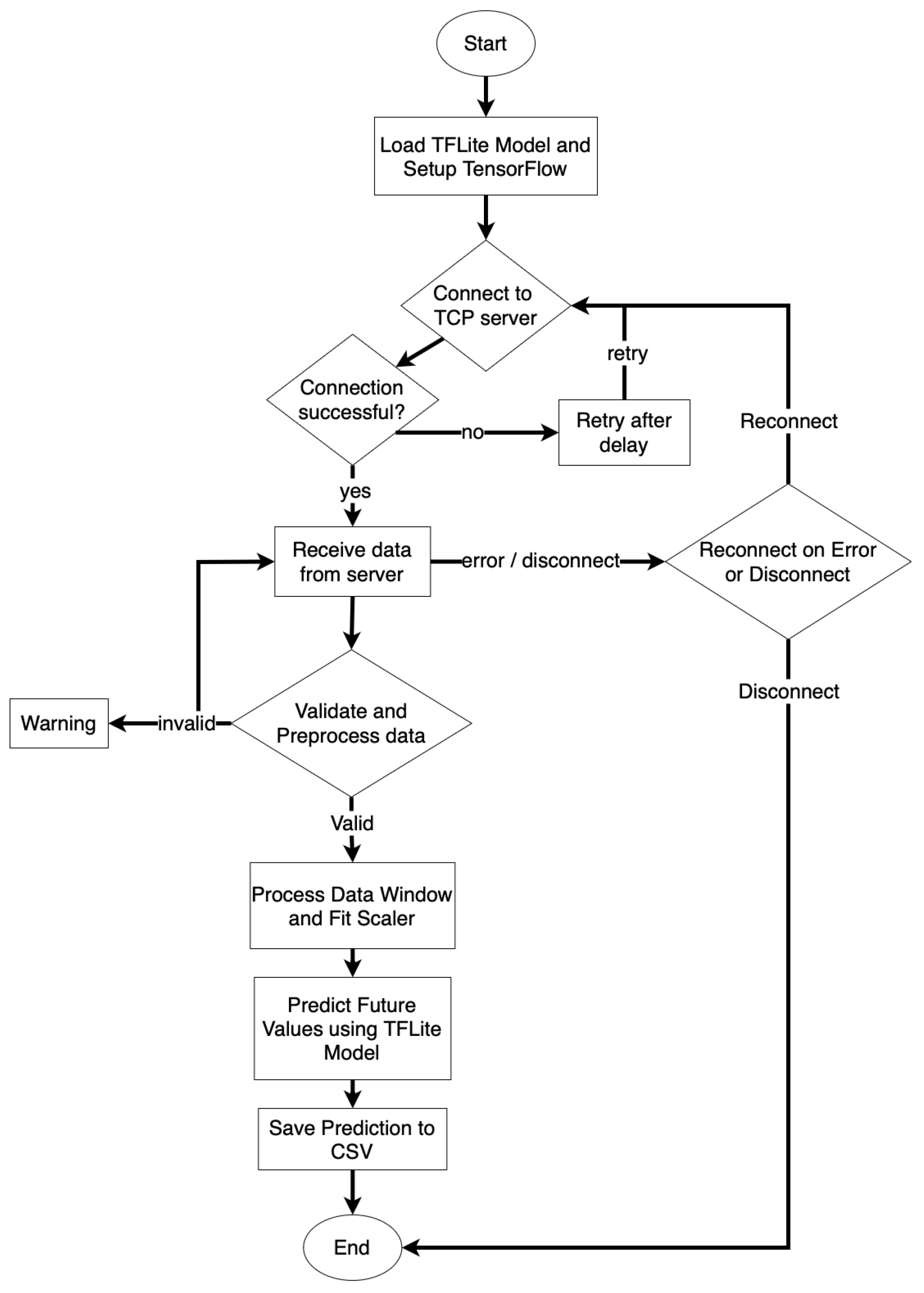

The inference codeThe software for the inference is based on Python 3.11, leveraging libraries such as Numpy 1.26.3, Pandas 2.1.4, Ujson 5.4.0, TensorFlow 2.15.0, and Sci-kit learn 1.2.2.Data acquisition begins with readings from a TCP server, which are preprocessed to eliminate erroneous values or measurements outside the acceptable range. Values exceeding this range trigger a warning, which the notification system records. Similarly, if the model predicts a value that is too high or too low, a warning is also triggered to signal potential anomalies. For error values (e.g., NaN), the algorithm ignores them to prevent distortion in the data. In the event of a disconnection from the TCP server, the program automatically attempts to reconnect after one second. After collecting enough valid measurements, the pre-trained model is loaded, and predictions are generated using a sliding window approach with a span of 20 values. This method ensures that each new measurement dynamically updates the forecast, providing precise and timely insights into sensor behavior while maintaining accuracy and detecting potential anomalies in real-time. To tailor predictions to the unique characteristics of each node, a personalized MinMax Scaler is trained for every sensor. This personalized scaling not only enhances the accuracy of the predictions but also facilitates the monitoring and maintenance of individual nodes, ensuring consistent performance across the network.

-

Requirements of the Host systemThe Host system must:

- −

-

Provide a sandbox environment for effortless integration of custom algorithms, empowering users to adapt the platform to diverse industrial needs. In our specific case:

- ∗

- Receive data from the Concentrator via TCP connection and process the raw data files generated by the container

- ∗

- Ensure real-time data processing, perform data cleaning, and apply integrated models or algorithms

- ∗

- Manage a sliding window of 20 values for accurate predictions of future data points

- ∗

- Provide updated predictions with each new data input to enhance monitoring and process optimization

- −

- Integrate easily with external systems for data analysis and industrial management

4. Experiment and Discussion

- RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error): This metric quantifies the square root of the average squared differences between the observed and predicted values. It is calculated as:where are the observed values, are the predicted values, and n is the number of data points.

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error): MAE represents the average absolute difference between predicted values and actual values. It is given by:where are the observed values, are the predicted values, and n is the number of data points.

- MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error): This metric expresses the average absolute percentage difference between predicted and actual values, offering a relative measure of prediction accuracy. It is calculated as:where are the observed values, are the predicted values, and n is the number of data points.

- Accuracy: Accuracy is defined as the percentage of correct predictions made by the model out of all predictions. It can be calculated as:where the number of correct predictions refers to the instances where and n is the total number of predictions.

- R2 (R-squared): R-squared measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variables in the model. It is computed as:where are the observed values, are the predicted values, is the mean of the observed values, and n is the number of data points. A higher value indicates a better fit of the model to the data.

4.1. Controlled Laboratory Results

| Container | Number of nodes | Memory | CPU |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0 | 570MB | 0% |

| Only Native | 1 | 671MB | 10% |

| Only Native | 50 | 700MB | 17% |

| Only Host | 1 | 800MB | 10% |

| Only Host | 50 | 1GB | 20% |

| Docker Compose | 1 | 1,2GB | 35% |

| Docker Compose | 50 | 1,4GB | 55% |

4.2. Real Machine Results

5. Comparison with Existing Approaches

5.1. Comparison with FDPR [44]

5.2. Comparison with the FAQMP [45]

5.3. Comparison with the DeepFogAQ [45]

6. Conclusions and Future Works

Acknowledgments

References

- Saeed, A.; Khattak, M.A.K.; Rashid, S. Role of Big Data Analytics and Edge Computing in Modern IoT Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Digital Futures and Transformative Technologies (ICoDT2) 2022, 1-5. [CrossRef]

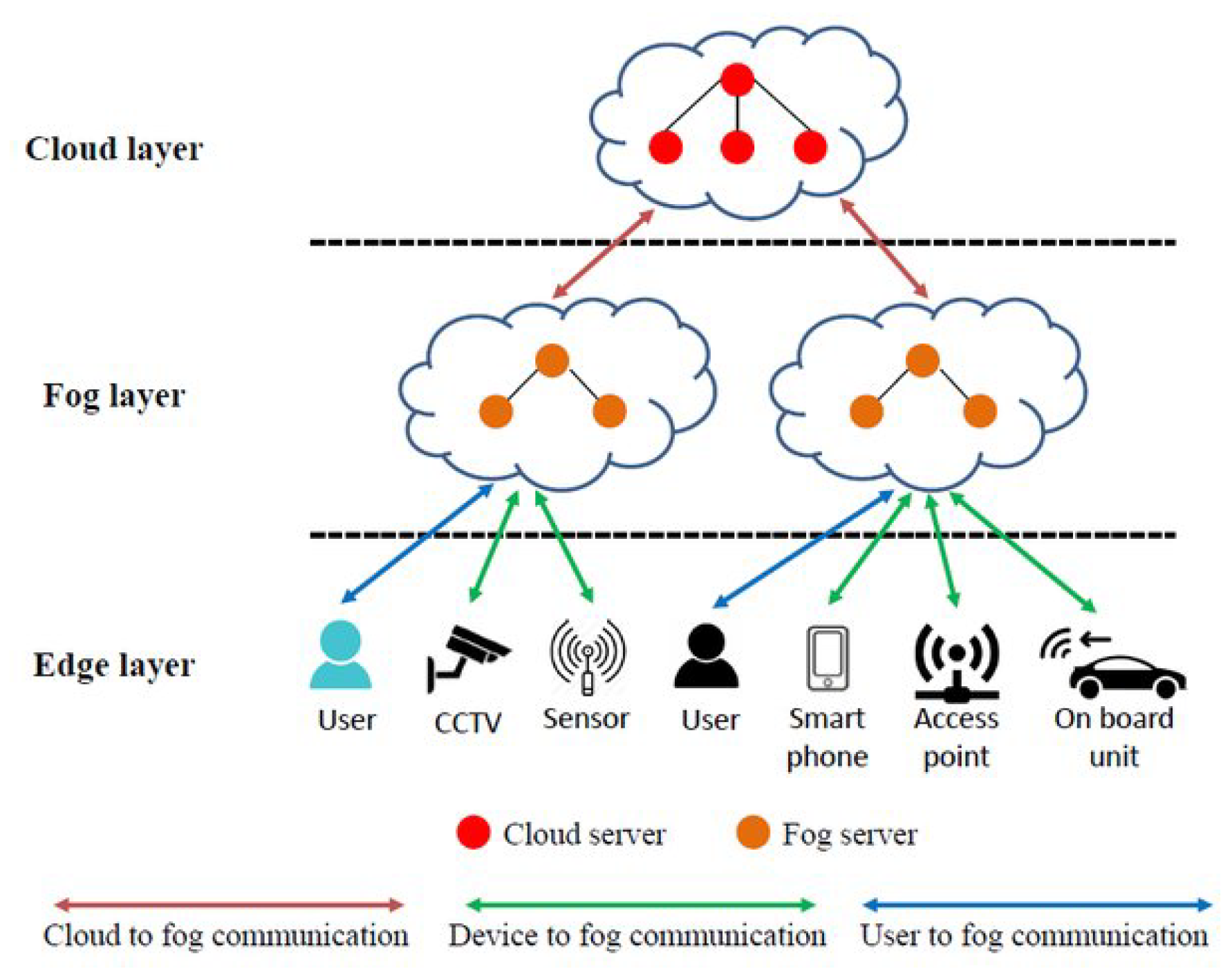

- Mathur, S.; Verma, A.; Srivastav, G. Analysis of the Three Layers of Computing: Cloud, Fog, and Edge. 2023 International Conference on Computational Intelligence, Communication Technology and Networking (CICTN) 2023, pp. 463-466. [CrossRef]

- Forsström, S.; Lindqvist, H. Evaluating Scalable Work Distribution Using IoT Devices in Fog Computing Scenarios. Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT) 2023, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Aziz, I.A.; Osman, N.A.B.; Ullah, I. A Review on Task Scheduling Techniques in Cloud and Fog Computing: Taxonomy, Tools, Open Issues, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 143417-143445. [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.-Y.; et al. A Lightweight Anonymous Authentication and Secure Communication Scheme for Fog Computing Services. IEEE Access 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tianfield, H. Towards Edge-Cloud Computing. Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) 2018, 4883-4885. [CrossRef]

- Rajanikanth, A. Fog Computing: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Journal of Autonomous Intelligence 2023, 24, 5. [CrossRef]

- Atlam, H.F.; Walters, R.J.; Wills, G.B. Fog Computing and the Internet of Things: A Review. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2018, 10, 2. [CrossRef]

- Mouradian, C.; Naboulsi, D.; Yangui, S.; Glitho, R.; Morrow, M.; Polakos, P. A Comprehensive Survey on Fog Computing: State-of-the-Art and Research Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2017. [CrossRef]

- Abdali, T.-A.N.; Hassan, R.; Aman, A.H.M.; Nguyen, Q.N. Fog Computing Advancement: Concept, Architecture, Applications, Advantages, and Open Issues. IEEE Access 2021. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, P.; Gill, S.S. Fog Computing: A Taxonomy, Systematic Review, Current Trends and Research Challenges. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2021, 157, 6. [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.; Walia, K.; Kaur, A. Challenges in Conglomerating Fog Computing with IoT for Building Smart City. Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Methods in Science & Technology (ICCMST) 2021, 2, 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, R.; Basha, S.M.; Praveen, M.; Reddy, P. Internet of Things and Fog Computing Applications in Intelligent Transportation Systems. In IGI Global 2019, Chapter 008.

- Stephen, V. K.; Udinookkaran, P.; De Vera, R. P.; Al-Harthy, F. R. A. Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) Fog-Based Smart Health Monitoring. 2023 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI) 2023, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.; Saleem, J.; Hudabia, M.; Hafiz, T.; Mannan, R.; Mishaal, A. A Survey on Fog Computing in IoT. VFAST Transactions on Software Engineering 2021, 9, 4. [CrossRef]

- IEEE. IEEE Guide for General Requirements of Mass Customization. IEEE Std 2672-2023 2023, 1-52. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Zeebaree, S. Resource Allocation in Fog Computing: A Review. 2020 Fifth International Conference on Fog and Mobile Edge Computing (FMEC) 2021, 10, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Matam, R.; Shu, L.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.A.; Choudhury, N.; Kumar, V. Security and Privacy in Fog Computing: Challenges. IEEE Access 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dwivedi, M.; Kumar, M.; Gill, S. S. A Comprehensive Review of Vulnerabilities and AI-Enabled Defense against DDoS Attacks for Securing Cloud Services. Computer Science Review 2023, 53, 100661. ISSN 1574-0137. [CrossRef]

- Kolevski, D.; Michael, K. Edge Computing and IoT Data Breaches: Security, Privacy, Trust, and Regulation. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine 2024, 43, no. 1, pp. 22-32. [CrossRef]

- Pakmehr, A.; Aßmuth, A.; Taheri, N.; Ghaffari, A. DDoS Attack Detection Techniques in IoT Networks: A Survey. Cluster Computing 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alsadie, D. Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Securing Fog Computing Environments: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 151598-151648. [CrossRef]

- Marchang, J.; McDonald, J.; Keishing, S.; Zoughalian, K.; Mawanda, R.; Delhon-Bugard, C.; Bouillet, N.; Sanders, B. Secure-by-Design Real-Time Internet of Medical Things Architecture: e-Health Population Monitoring (RTPM). Telecom 2024, 5, 609-631. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; et al. A Robust and Secure User Authentication Scheme Based on Multifactor and Multi-Gateway in IoT-Enabled Sensor Networks. Security and Privacy 2024, 7, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Krishna, C. R.; Patil, N. V. IoT Traffic-Based DDoS Attacks Detection Mechanisms: A Comprehensive Review. The Journal of Supercomputing 2024, 1573-0484. [CrossRef]

- d’Agostino, P.; Violante, M.; Macario, G. A User-Extensible Solution for Deploying Fog Computing in Industrial Applications. Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 32nd International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE) 2023, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Fava, F.B.; et al. Assessing the Performance of Docker in Docker Containers for Microservice-Based Architectures. Proceedings of the 2024 32nd Euromicro International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Network-Based Processing (PDP) 2024, 137-142. [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, P.; Violante, M.; Macario, G. An Embedded Low-Cost Solution for a Fog Computing Device on the Internet of Things. Proceedings of the 2023 Eighth International Conference on Fog and Mobile Edge Computing (FMEC) 2023, 284-291. [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, P.; Violante, M.; Macario, G. Optimizing LSTM-Based Temperature Prediction Algorithm for Embedded System Deployment. Proceedings of Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA) 2024, 01-07. [CrossRef]

- Masini, et al. Machine Learning Advances for Time Series Forecasting. J Econ Surv 2023, 37, 76-111. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jung, J.J. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series: Approaches, Applications, and Challenges. Information Fusion 2023, 81, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yao, L.; Xie, Y.; Sui, J.; Liao, Q. Deep-learning Approach for Predicting Performance in Fog Computing Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2024, 20, 2. [CrossRef]

- Lera, I.; Guerrero, C.; Juiz, C. YAFS: A Simulator for IoT Scenarios in Fog Computing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 91745-91758. [CrossRef]

- Wöbker, C.; Seitz, A.; Mueller, H.; Bruegge, B. Fogernetes: Deployment and Management of Fog Computing Applications. Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium (NOMS) 2018, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Gunderson, W.; Staten, E.; Donastien, Y.K.; Rodriguez, P.; Bailey, R. Integrating Modularity for Mass Customization of IoT Wireless Sensor Systems. Proceedings of the 2021 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS) 2021, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, R.; Toosi, A.N. Con-Pi: A Distributed Container-Based Edge and Fog Computing Framework. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 6, 4125-4138. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.; Gaikwad, R.; Patekar, T.; Dighe, S.; Shaikh, B.; Patankar, N.S. Predictive Maintenance of Industrial Equipment Using IoT and Machine Learning. Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computation, Automation and Knowledge Management (ICCAKM) 2023, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Dhanraj, D.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, G.; Mishra, S.; Naik, P.; Singh, A. Comparison of Different Machine Learning Algorithms for Predictive Maintenance. Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT) 2023, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.; Mohamed, H.K.; Badr Monir Mansour, M. Predictive Maintenance by Machine Learning Methods. Proceedings of the 2023 Eleventh International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems (ICICIS) 2023, 58-66. [CrossRef]

- Laganà, F.; Pratticò, D.; Angiulli, G.; Oliva, G.; Pullano, S.A.; Versaci, M.; La Foresta, F. Development of an Integrated System of sEMG Signal Acquisition, Processing, and Analysis with AI Techniques. Signals 2024, 5, 476-493. [CrossRef]

- Jouini, O.; Sethom, K.; Namoun, A.; Aljohani, N.; Alanazi, M.H.; Alanazi, M.N. A Survey of Machine Learning in Edge Computing: Techniques, Frameworks, Applications, Issues, and Research Directions. Technologies 2024, 12, 81. [CrossRef]

- Sergio Trilles, Sahibzada Saadoon Hammad, Ditsuhi Iskandaryan, Anomaly detection based on Artificial Intelligence of Things: A Systematic Literature Mapping, Internet of Things 2024 25. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Abdulazeez and S. K. Askar, Offloading Mechanisms Based on Reinforcement Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms in the Fog Computing Environment. IEEE Access 2023 11, 12555-12586. [CrossRef]

- M. A. P. Putra, A. P. Hermawan, C. I. Nwakanma, D. -S. Kim and J. -M. Lee, FDPR: A Novel Fog Data Prediction and Recovery Using Efficient DL in IoT Networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 16895-16906. [CrossRef]

- Pazhanivel, D.B.; Velu, A.N.; Palaniappan, B.S. Design and Enhancement of a Fog-Enabled Air Quality Monitoring and Prediction System: An Optimized Lightweight Deep Learning Model for a Smart Fog Environmental Gateway. Sensors 2024, 24, 5069. [CrossRef]

- Mehmet Ulvi Şimsek, İbrahim Kök, Suat Özdemir, DeepFogAQ: A fog-assisted decentralized air quality prediction and event detection system, Expert Systems with Applications 2024 251. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, W. Unified Modeling for Multiple-Energy Coupling Device of Industrial Integrated Energy System. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2023, 70, 1, 1005-1015. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wu, K.; Wang, C.; Wu, M.; Li, X. KDnet-RUL: A Knowledge Distillation Framework to Compress Deep Neural Networks for Machine Remaining Useful Life Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2022, 69, 2, 2022-2032. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Yakopcic, C.; Wu, Q.; Barnell, M.; Khan, S.; Taha, T.M. Survey of Deep Learning Accelerators for Edge and Emerging Computing. Electronics 2024, 13, 2988. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Guo, L.; Gao, H.; He, Y.; You, Z.; Duan, A. FedCAE: A New Federated Learning Framework for Edge-Cloud Collaboration Based Machine Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2024, 71, 4, 4108-4119. [CrossRef]

- Tufail, S.; Riggs, H.; Tariq, M.; Sarwat, A.I. Advancements and Challenges in Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review of Models, Libraries, Applications, and Algorithms. Electronics 2023, 12, 1789. [CrossRef]

- Ayankoso, S.; Olejnik, P. Time-Series Machine Learning Techniques for Modeling and Identification of Mechatronic Systems with Friction: A Review and Real Application. Electronics 2023, 12, 3669. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, et al. Benchmarking Algorithms for Time Series Classification. Data Science and Knowledge Engineering 2023, 48, 63-77. [CrossRef]

- Alex Sherstinsky, Fundamentals of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, Volume 404, 2020, 132306, ISSN 0167-2789. [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, E.; Kalyanam, K.R.; Batts, J.; Kim, J.; Singh, S.; Vo, T.; Yan, C. Investigating Messaging Protocols for the Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Access 2020, 8, 94880-94911. [CrossRef]

- Robert H. Shumway and David S. Stoffer, ARIMA Models, Time Series Analysis and Its Applications: With R Examples,Springer International Publishing 2017, 75–163. [CrossRef]

- A. Anand, D. Srivastava, and L. Rani, Anomaly Detection and Time Series Analysis, 2023 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology (ICICAT) 2023, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Farhan Aslam, Advancing Credit Card Fraud Detection: A Review of Machine Learning Algorithms and the Power of Light Gradient Boosting American Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2024 7, 9–12. [CrossRef]

- Elhanashi, A.; Dini, P.; Saponara, S.; Zheng, Q. Advancements in TinyML: Applications, Limitations, and Impact on IoT Devices. Electronics 2024, 13, 3562. [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Node | MAE | RMSE | Accuracy | R² | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory | NODE_36 | 0.0126 | 0.0156 | 99.81% | 0.9970 | 0.0441 |

| Laboratory | NODE_25 (Anomaly) | 2.3526 | 11.5418 | 45% | -6211580.9 | 55 |

| Real Machine | NODE_08 | 0.1821 | 0.2880 | 99.2% | 0.8898 | 0.7227 |

| Metric | The Concentrator (LSTM-TFLite model) | FDPR (DC-MLP) |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | 0.1821 | 0.06 |

| RMSE | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| MAPE | 0.7 | 0.002 |

| Prediction Accuracy (%) | 99.2 | 99.86 |

| Inference Time (ms) | 200 | 0.05 |

| Metric | The Concentrator (LSTM-TFLite Model) | FDPR (Seq2Seq GRU Attention-TFLite Model) |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | 0.1821 | 4.385 |

| RMSE | 0.28 | 7.9016 |

| MAPE | 0.7 | 22.0133 |

| R2 | 0.8898 | 0.6566 |

| Inference Time (ms) | 200 | 52671.8 |

| Metric | The Concentrator (LSTM-TFLite Model) | DeepFogAQ (Transformers) |

|---|---|---|

| MAE | 0.1821 | 3.15 |

| RMSE | 0.28 | 3.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).