1. Introduction

Today, the disposal of radioactive waste has become a serious environmental problem, since its storage requires hundreds and thousands of years of aging until the level of radioactivity of the waste reaches a safe level (Kautsky et al., 2016; Rebolledo et al., 2023; Zou and Cvetkovic, 2023; Kim et al., 2024; McCloy et al., 2024; Tan et al., 2024). In addition to the constant increase in the volume of this waste produced by nuclear power plants, research institutes, medical centers, military facilities, etc., they pose a danger in the future to being used for terrorist purposes or to being causing environmental disasters due to man-made accidents. The ideas proposed in the last century to launch radioactive waste into space as passive ballast require large capital investments. On the other hand, it can be assumed that, being an element of the design of automatic spacecraft, radioactive materials made from RW will not have a detrimental effect on the operation of space equipment due to its radioactivity, since this equipment is already designed to operate in conditions of cosmic ionizing radiation.

It is known that additions of powders from crushed rocks improve the physical properties of polymers (Mamedov and Musayevа, 2022; Ramesh et al., 2022; Elsafi et al., 2023). Cement for immobilization of radioactive waste can be considered as artificial calcite, since its composition, wt.%: 64 - 67 – CaO, 21 - 25 – SiO2, 4 - 8 – Al2O3, 2 - 4 – Fe2O3 and small number of other compounds: Na2O, K2O, MgO, TiO2, P2O5 (Gafarova and Kulagina, 2016). Radioactive material weighing up to 30% of the cement weight is encapsulated/immobilized into cement. Glasses for immobilization of RW are close in composition to aluminosilicate rocks. Thus, one of the most frequently used glasses is borosilicate glass, which has the composition, wt.%: 60 - 80 – SiO2, 4 - 8 – Na2O (or K2O), 7 - 27 – B2O3, 2 - 8 – Al2O3 (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2016). RW weighing up to less than 20% of the glass weight is encapsulated/immobilized in glass. Basalt, granite, calcite and industrial ash used as fillers in composites have the same content of compounds as cement and glass for RW immobilization. Radioactive material immobilized into cement or glass can be radioactive soil, shell rock, textiles, paper, and so on. After grinding cemented or vitrified RW, the radioactive material is evenly distributed throughout the resulting powder, and this powder can be considered as a potential filler.

Ionizing radiation acts in different ways - it can improve, worsen or not affect the properties of the composite at all, which depends on the dose (Haque et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2010; Seo et al., 2012; Visakh et al., 2017; Aldhuhaibat et al., 2021). Therefore, a radioactive composite with fillers made from radioactive waste may have unique properties that we know nothing about, since there is no scientific data on the properties of composites containing internal radioactive sources. It is also known that crushed industrial and agricultural waste is added to polymer and metal matrices: slag from metal smelting (Barczewski et al., 2022), various types of steel (Gobetti et al., 2024), ash from wood burning (Mamedov and Musayevа, 2022), husks and shells of various agricultural crops (Oyewo et al., 2024). It will be natural if supplement this waste with radioactive waste.

2. Review of Composites with Fillers from Rocks, Industrial and Agricultural Waste and the Effect of Radiation on the Properties of Composites

2.1. Properties of Composites Under Radiation Exposure

In (Wu et al., 2010), the radiation properties of a composite made of an epoxy matrix and glass fiber filler were studied. The mechanical properties of this composite at a liquid nitrogen temperature of 77 K were measured before and after γ-irradiation with Co60 at a dose of 1 MGy. γ-radiation had virtually no effect on the properties of the composite. Such composites are used in superconducting magnetic systems operating under radiation conditions at cryogenic temperatures.

In the study (Seo et al., 2012), electron beam irradiation was applied to composites of a blend of high-density polyethylene and ethylene propylene monomer, both containing nano or micro particles of B2O3 and/or PbO. The tensile strength increased more than twofold and the elongation increased more than fivefold when irradiated by dose 150 kGy of electron beam with electron energy of 10 MeV. Further improvement of mechanical properties was achieved by adding 1 wt.% of the crosslinking agent - triallyl cyanurate to the mixture and again electron beam irradiation. The fire resistance of this polymer composite significantly improves without the use of any fire-retardant additives. These composites are used as radiation protection against neutron irradiation under high temperature conditions.

Composites based on an epoxy matrix with various fillers are used as radiation protection. Thus, in (Aldhuhaibat et al., 2021) a study was conducted on the effectiveness of protection against gamma radiation of nanocomposites based on epoxy resin with aluminum oxide or iron oxide nanopowders in various concentrations: 10–15 wt.%. The samples were irradiated with radioactive sources Cs137 (1.05 kBq with a single gamma-ray energy of 0.662 MeV) and Co60 (74 kBq with two gamma-ray energies of 1.173 and 1.333 MeV). Epoxy nanocomposites have been found to be potential gamma-ray shields with improved performance. In (Haque et al., 2003), epoxy matrix was reinforced with layered nano-silicate particles at very low concentrations (1 wt.%) and found that the flexural strength, impact toughness, decomposition temperature and interlaminar shear strength of S2-glass/epoxy resin composites were improved.

In (Visakh et al., 2017), the effect of electron beam irradiation on the thermal and mechanical properties of epoxy composites filled with aluminum nanoparticles in a percentage ratio of 0.35 wt.% was studied. Epoxy resin/nano metal powder composites are widely used in nuclear and aerospace industries. Epoxy composites were exposed to electron beam irradiation at doses of 30, 100 and 300 kGy. The results of measuments showed that the studied epoxy composites exhibited good radiation resistance. Thermal and mechanical properties of aluminum-based epoxy composites improve with increasing radiation dose up to 100 kGy and then deteriorate with further increase in dose.

2.2. Composites with Filler from Industrial Waste

The main components of blast furnace slag (aluminosilicate) are aluminum oxide, silicon dioxide, calcium oxide and magnesium oxide, and small traces of manganese oxide and sulfur. A suitable method for the disposal of this waste may be to use this material as filler for polymer composites. In (Sawlani et al., 2023), a hybrid composite of polypropylene/short glass fiber/blast furnace slag was studied. The glass fiber content was kept constant at 20 wt.%, and the slag content was varied from 10 to 30 wt.%. Mechanical properties and erosion properties were significantly better compared to non-hybrid polypropylene/blast furnace slag composites or pure polypropylene. The physical and mechanical properties of the polyester/blast furnace slag composite material with a filler content of 5 to 20 wt.% were also studied. The most suitable combination of composites was polyester with 10 wt.% blast furnace slag, which showed the greatest improvement in mechanical properties compared to pure polymer.

Copper slag (metallurgical waste) was introduced into a polylactide matrix (a heat-resistant polymer used as a housing for electronic devices) in quantities of 5, 10, 20 and 35 wt.% (Barczewski et al., 2022). Improvement in mechanical properties was observed for composites with a slag filler content not exceeding 20 wt.% compared to pure polymer. Copper slag is a non-ferrous metal slag formed during the smelting of ores. The chemical composition of copper slag is in many ways similar to the composition of fossil minerals such as basalt, wt.%: 41,2 - SiO2, 19,1 - Al2O3, 13,1 - CaO, 12,0 - Fe2O3 + FeO, 4,9 - MgO, 1,1 - Cu. The slag particles, as a filler of the polymer matrix, had an average size of 200 µm.

Steel slag from electric arc furnaces (metallurgical waste) is used as filler in a matrix of nitrile butadiene rubber used in machine parts (Gobetti et al., 2024). Composition of steel slag, wt.%: 33,8 - Fe2O3, 30,2 - CaO, 9,4 - SiO2, 6,9 - MnO, 6,4 - Al2O3, 6,1 - Cr2O3, and a small number of other compounds. The physical and chemical properties of such a composite are better than those of pure rubber and are not inferior to the carbon black/rubber composite, which it was developed to replace due to environmental concerns.

2.3. Rock Filled Composites

Article (Mamedov and Musayevа, 2022) indicates the possibility of using basalt as a filler for an epoxy compound – epoxy resin grade ED-20, a hardener for polyethylene polyamine and a multifunctional modifier – trichloroethyl phosphate. Preparation of basalt consisted of its crushing and fractionation. Composition of basalt (aluminosilicate), wt.%: 50 - SiO2, 16 - Al2O3, 10 - CaO, 8 - FeO, 6 - MgO, 4 - Fe2O3, 2 - Na2O, and a small number of other compounds. An improvement in mechanical properties was observed - Brinell hardness, resistance to static and dynamic bending (impact) more than twice, and physical and chemical heat resistance also increases in comparison with unfilled polymer.

In (Mamedov and Musayevа, 2022), a composite based on epoxy resin with kaolin (from 2 to 20 wt.%) was also investigated. Kaolin clay formula: Al2O3·2SiO2·2H2O. Improvement in mechanical properties and fire resistance of the polymer was observed.

Hybrid composites based on epoxy resin reinforced with glass fiber and granite nanopowder are used in the space industry and mechanical engineering (Ramesh et al., 2022). Chemical composition of granite (aluminosilicate), wt.%: SiO2 68 - 73; Al2O3 12,0 - 15,5; Na2O 3,0 - 6,0; CaO 1,5 - 4,0; FeO 0,5 - 3,0; Fe2O3 0,5 - 2,5; К2О 0,5 - 3,0; MgO 0,1 - 1,5; ТіO2 0,1 - 0,6; ThO2 0,001 - 0,004; UO2 0,0002 - 0,001.

In (Elsafi et al., 2023), the radiation-protective properties of various composites against gamma radiation were compared: epoxy resin + marble waste + nano-WO3, epoxy resin + nano-MgO, silicone rubber + nano-WO3. The best shielding properties were demonstrated by a composite with marble waste and nano-WO3. Chemical composition of fine marble waste (particle size no more than 50 microns), wt.%: 45 - CaO, 0.5 - Al2O3, 1.4 - MgO, 23.5 - SiO2, 9 - Fe2O3, and a small number of other compounds. The marble content in the composite varied from 25% to 50% by weight.

2.4. Composites with Fillers from Agricultural Waste

Adding wood ash to epoxy oligomer increases elasticity, impact resistance, and compressive strength (Mamedov and Musayevа, 2022). Composition of wood ash, wt.%: 49 - CaO, 26 - K2O, 9 - SiO2, 3.4 - MnO, 3.3 - P2O5, and a small number of other compounds. Physical analysis showed 100% increase in impact strength, 40% increase in elongation during stretching of epoxy resin-based composite materials.

To improve the mechanical properties of aluminum alloys used in the aerospace industry, they are reinforced with various ceramic inclusions - mainly alumina Al2O3 and silicon carbide SiC, as well as coconut shell ash, bagasse and peanut shells from agricultural waste (Oyewo et al., 2024). Composition of coconut ash, wt.%: 40 – 50 - SiO2, 12 - Fe2O3, 11 - CaO, 12 - K2O, and a small number of other compounds. In this way, hybrid composites are obtained (with primary reinforcement, for example, alumina and secondary reinforcement - ash) based on an aluminum matrix with high operational, thermal and wear-resistant characteristics compared to conventional aluminum alloys.

2.5. Radiation Irradiation of Rock-Filled Composites

In (Li et al., 2015), the properties of a composite based on epoxy resin reinforced with basalt fiber were studied under γ-irradiation from a 60Co source with doses up to 2.0 MGy. Basalt fiber weakened the aging effect (increased service life) of the composite matrix due to γ-irradiation. The mechanical properties of the composite remained unchanged at this dose, and the interlaminar shear strength increased at an irradiation dose of 0 – 1.5 MGy. For pure epoxy resin (without filler), polymer chain scission and oxidation induced by irradiation were observed. Basalt fiber, derived from volcanic rock, exhibits equivalent tensile strength, higher modulus of elasticity and better alkali resistance than fiberglass. Compared with carbon fiber, basalt fiber has lower cost, higher fire resistance and better thermal insulation.

2.6. Conclusion

From the above review, it is clear that concrete or aluminosilicate and borosilicate glass containing radioactive waste are equivalent in composition to marble, wood ash or metallurgical slag, granite, kaolin clay, coconut ash, respectively, which are used as fillers in composite matrices. This means that we can assume that filler made from crushed cemented or vitrified RW can also be used to improve the properties of composite materials. The intrinsic radioactivity of the filler can also improve the characteristics of the composite, as is observed when composites with fillers made of substances similar in composition to radioactive waste are irradiated with external sources.

3. Description of the Technological Process for Creating Radioactive Composites

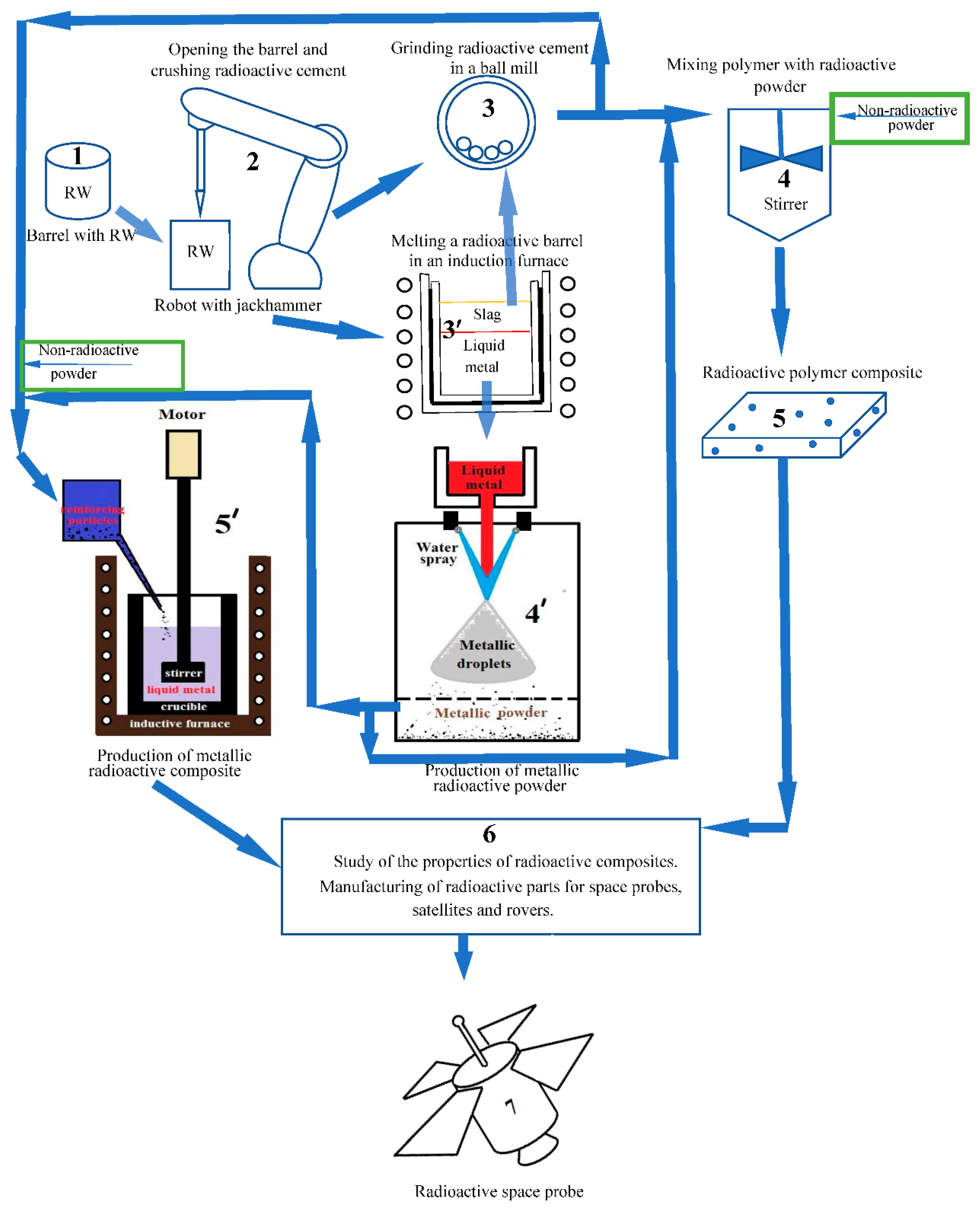

At the first stage, barrels with radioactive waste from radioactive waste storage facilities are transported to sealed closed premises (

Figure 1, stage 1). Sealed premises are necessary to prevent radioactive dust generated during work with radioactive waste from entering the environment. In these rooms, barrels with radioactive waste are opened, their contents – radioactive glass, Portland cement or another immobilizing matrix – are crushed into pieces about 2 cm in size (

Figure 1, stage 2). Remote-controlled robots can be used to crush radioactive cement or glass.

The crushed radioactive material is then loaded into ball mills (the mills must also be located in the same sealed room), where it is ground to micro or nanosizes (

Figure 1, step 3). All further operations are carried out in a sealed room. The steel barrel from which the radioactive waste has been removed must be loaded, possibly after being cut into pieces, into an arc, induction or vacuum melting furnace (

Figure 1, step 3′), where it is remelted.

In

Figure 1, the stage 4′ shows a jet method for producing steel micro or nanopowder, when liquid metal is poured from a tundish with molten metal into a volume in which a high-pressure water jet interacts with the liquid metal, splashes it, which leads to rapid cooling of micro or nanodroplets of metal, which, falling, solidify and settle in a collector, in the lower part of the volume (Asgarian et al., 2022). The resulting steel micro or nanopowder is sent to stage 5′. The slag from the remelting of the barrel, obtained at stage 3′, is planned to be ground in a ball mill in the same way as radioactive waste (radioactive glass, concrete, etc.) – indicated by the arrow between stages 3′ and 3.

At stage 4, it is proposed to mix the polymer, which is the matrix of the polymer composite, with micro or nanopowders obtained in a ball mill (crushed cement, or glass, or slag) or with steel micro or nanopowders obtained at stage 4′. At stage 5, the mixture of polymer and filler after mixer 4 is poured into the mold and hardens, resulting in a composite.

Figure 1.

Simplified flow chart of radioactive waste immobilization into composite materials. The numbers indicate the stages of the technological process described in the text. The numbers indicate the stages of the technological process described in the text.

Figure 1.

Simplified flow chart of radioactive waste immobilization into composite materials. The numbers indicate the stages of the technological process described in the text. The numbers indicate the stages of the technological process described in the text.

As step 5′ in

Figure 1, the process of mixing the liquid metal or alloy used as the matrix of the metal composite with the steel nanopowder obtained from remelting the radioactive barrel in step 4′ or with the powder obtained in the ball mill is shown. That is, a metal or alloy used in the aerospace industry (usually aluminum alloys) is melted in a crucible in an induction furnace and reinforcing micro- or nanoparticles are added to it, which can be steel, cement, slag, glass, etc. Reinforcing particles – micro or nanosized particles that improve the properties of the material (Singh and Kumar, 2022; Yan et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). The mixture is stirred with a stirrer and poured into a mold (not shown in the figure), resulting in a metal composite that differs from the original metal in a number of improved characteristics.

After stages 5 and 5′, polymer and metal composites go to stage 6 – studying the properties of manufactured radioactive composites, manufacturing parts and structural elements of space automatic devices and systems from them. The resulting radioactive composites are expected to belong to the class of very low-radioactive materials, which will allow technical personnel to work with them without the use of remote-controlled robots. To achieve such low radioactivity the following procedure is proposed.

The amount of powder added to the composite is approximately 2% to 70% by weight, depending on the matrix and the desired properties. Since the radioactive powder material is widely available in non-radioactive form – cement, glass, steel, etc., then in order to reduce the specific activity of the composite, it is planned to add non-radioactive powders to the composite, which is indicated in stages 4 and 5′ of

Figure 1 (highlighted in green). The quantities of mixed radioactive and non-radioactive powders for a given matrix mass required to achieve the desired level of radioactivity in the final composite are easily calculated. Reducing the radioactivity of the composite to a very low radioactive class will facilitate its transportation, manufacture of probe parts, and ground testing of the radioactive space probe (Step 7 of

Figure 1) before it is sent into space.

4. Conclusion

We hypothesized that cemented and vitrified RW, ground to a nano or micropowder state, could be used as a filler in polymer, metal and other matrices. As a result, it is possible to obtain the same positive effect as for composites with fillers made from natural rock, industrial and agricultural waste. Thus, in the long term, taking into account the development of technologies and the reduction in the cost of sending cargo into space, we will be able to solve the problem of burying in space the huge amount of radioactive waste already accumulated around the world as the payload of space probes, rovers and other devices. It is also possible that radioactive powders and composites will turn out to be materials with unique properties and no analogues, which could offset the costs of their production.

References

- Aldhuhaibat, M.; Amana, M.; Jubier, N.; Salim, A. Improved gamma radiation shielding traits of epoxy composites: Evaluation of mass attenuation coefficient, effective atomic and electron number. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2021, 179, 109183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarian, A.; Morales, R.; Bussmann, M.; Chattopadhyay, K. Water atomisation of molten metals: A mathematical model for a water spray. Powder Metallurgy 2022, 65(1), 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczewski, M.; Hejna, A.; Aniśko, J.; Andrzejewski, J.; Piasecki, A.; Mysiukiewicz, O.; Bąk, M.; Gapiński, B.; Ortega, Z. Rotational molding of polylactide (PLA) composites filled with copper slag as a waste filler from metallurgical industry. Polymer Testing 2022, 106, 107449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafi, M.; Almousa, N.; Al-Harbi, N.; Almutiri, M.; Yasmin, S.; Sayyed, M. Ecofriendly and radiation shielding properties of newly developed epoxy with waste marble and WO3 nanoparticles. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 22, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafarova, V.; Kulagina, T. Safe methods of radioactive waste utilization. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Eng. Technol. 2016, 9(4), 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobetti, A.; Cornacchia, G.; Agnelli, S.; Ramini, M.; Ramorino, G. A novel and sustainable rubber composite prepared from electric arc furnace slag as carbon black replacement. Carbon Resources Conversion 2024, 7(4), 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Shamsuzzoha, M.; Hussain, F.; Dean, D. S2-Glass/Epoxy Polymer Nanocomposites: Manufacturing, Structures, Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Journal of Composite Materials 2003, 37(20), 1821–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rafferty, A.; Sajjia, M.; Olabi, A. Properties of Glass Materials. Encyclopedia of Materials: Technical Ceramics and Glasses 2016, 2, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautsky, U.; Saetre, P.; Berglund, S.; Jaeschke, B.; Nordén, S.; Brandefelt, J.; Keesmann, S.; Näslund, J.; Andersson, E. The impact of low and intermediate-level radioactive waste on humans and the environment over the next one hundred thousand years. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 2016, 151(2), 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Han, S.; Yun, J. Effect of supplementary cementitious materials on the degradation of cement-based barriers in radioactive waste repository: A case study in Korea. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2024, 56(9), 3942–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, T. A review of mesoscopic modeling and constitutive equations of particle-reinforced metals matrix composites based on finite element method. Heliyon 2024, 10(5), 2405–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Gu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. Effect of γ irradiation on the properties of basalt fiber reinforced epoxy resin matrix composite. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2015, 466, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamedov, B.; Musayevа, A. Compositions based on epoxy resins are filled with different fillers (Overview). The Scientific Heritage 2022, 88, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloy, J.; et al. International perspectives on glass waste form development for low-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste. Materials Today 2024, 1369–7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewo, A.; Oluwole, O.; Ajide, O.; Omoniyi, T.; Hussain, M. A summary of current advancements in hybrid composites based on aluminium matrix in aerospace applications. Hybrid Advances 2024, 5, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, B.; Kumar, S.; Elsheikh, A.; Mayakannan, S.; Sivakumar, K.; Duraithilagar, S. Optimization and experimental analysis of drilling process parameters in radial drilling machine for glass fiber/nano granite particle reinforced epoxy composites. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 62(2), 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo, N.; Torres, J.; Chinchón-Payá, S.; Sánchez, J.; de Gregorio, S.; Ordóñez, M.; López, I. Monitoring in a reinforced concrete structure for storing low and intermediate level radioactive waste. Lessons learnt after 25 years. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2023, 55(4), 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawlani, P.; Tyagi, D.; Rajput, V.; Sahu, M.; Gupta, G.; Jha, A.; Agrawal, A. Physical and mechanical behaviour of polyester-based composites with micro-sized blast furnace slag as filler material. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023, 2214–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.; Kim, J.; Kang, P.; Seo, C.; Lee, J.; Kim, H. Enhancement of flame retardancy and mechanical properties of HDPE/EPM based radiation shielding composites by electron beam irradiation. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2012, 429((1–3)), 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, A. A literature survey on effect of various types of reinforcement particles on the mechanical and tribological properties of aluminium alloy matrix hybrid nano composite. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 56(1), 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, P. Effect of drying cracks on swelling and self-healing of bentonite-sand blocks used as engineered barriers for radioactive waste disposal. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering 2024, 16(5), 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visakh, P.; Nazarenko, O.; Chandran, C.; Melnikova, T.; Nazarenko, S.; Kim, J. Effect of electron beam irradiation on thermal and mechanical properties of aluminum based epoxy composites. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2017, 136, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Chu, X.; Li, L. Novel radiation-resistant glass fiber/epoxy composite for cryogenic insulation system. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2010, 403((1–3)), 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Kou, S.; Yang, H.; Shu, S.; Shi, F.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Q. Microstructure-based simulation on the mechanical behavior of particle reinforced metal matrix composites with varying particle characteristics. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 26, 3629–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Cvetkovic, V. Disposal of high-level radioactive waste in crystalline rock: On coupled processes and site development. Rock Mechanics Bulletin 2023, 2(3), 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).