1. Introduction

Radiotherapy using X-rays and chemotherapy provided by anticancer agents are the primary cancer treatment modalities. The abscopal effect, a phenomenon in which non-irradiated tumors, such as metastases, shrink and/or disappear, rarely occurs in radiotherapy [

1,

2]. Although the mechanism of the abscopal effect has not been fully elucidated, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from irradiated cancer cells are thought to be involved [

3]. These DAMPs could be released by stressed cancer cells when they are damaged by radiation or anticancer agents [

3,

4]. Some DAMPs activate immunity whereas others suppress it [

5,

6]. Dendritic cells activated by immunostimulatory proteins phagocytose deceased cancer cells, recognize cancer antigens, and activate cytotoxic T cells to attack cancer cells [

7]. However, the cytotoxic T-cell attacks on cancer cells that cause the abscopal effect are easily inhibited by combining the PD-1 receptor on the surface of immune cells with the PD-L1 ligands on the cell membranes of cancer cells [

8]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and durvalumab, have attracted attention because they inhibit these immune checkpoints (PD-1 or PD-L1), maintain immune activity by preventing PD-1 or PD-L1 binding, and restore antitumor effects [

9,

10]. To enhance the abscopal effect, it is crucial to release more immunostimulatory proteins in DAMPs, activate more immune cells, and develop more effective immune checkpoint inhibitors.

DAMPs that activate immunity include adenosine triphosphate (ATP), calreticulin (CRT), and high mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) [

11]. Extracellular ATP binds to the P2X7 purinoreceptor expressed on immune cell membranes and activates immune cells [

12]. CRT exposed on cancer-cell membranes signals dendritic cells and others via CD91, contributing to immune activation [

13]. Therefore, ATP and CRT primarily contribute to cancer immunity by binding to specific receptors. In contrast, HMGB1 has affinity for various receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLR)2, TLR4, and the receptor for advanced glycation end-products and can activate immune cells through multiple pathways [

14]. In addition, external irradiation of cancer has been shown to damage cells and increase the release of HMGB1 [

15]. In radiotherapy for cancer, ideally only cancer cells should be irradiated, but even with certain techniques, such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy, it is difficult to achieve no damage to all tissue, and studies are underway to reduce toxicity to normal tissue [

16,

17]. Although it has been shown that HMGB1 is released in irradiated skin cells in mice [

18], it is not clear if HMGB1 is released from normal cells in humans.

In addition to external irradiation, radiopharmaceutical therapy has received attention in recent years [

19]. Radioimmunotherapy using the internal radiopharmaceutical agents

177Lu-DOTATATE and

223RaCl

2 has been conducted in preclinical studies and shown to give better cancer treatment than treatment with

177Lu-DOTATATE and

223RaCl

2 alone [

20]. Iodine-131-labeled

m-iodobenzylguanidine (

131I-MIBG), an internal radiopharmaceutical therapy agent, is frequently used to treat neuroblastoma and is effective against refractory or recurrent neuroblastomas [

21,

22]. Nevertheless, there are side effects, such as diminished bone marrow function and limited therapeutic effectiveness in specific patient populations [

21,

23]. In radioimmunotherapy using internal radiopharmaceutical therapy, the release of DAMPs, including HMGB1, from damaged cancer and normal cells has not been examined in comparison with that observed for radioimmunotherapy using external radiotherapy. The study aim was to determine if HMGB1 can be released from damaged human-derived cancer and normal cells after administration of

131I-MIBG. The release of HMGB1 from damaged cancer cells may lead to improved cancer treatment, but HMGB1 released from damaged normal cells may contribute to or cause side effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cancer Cell Lines

The human-derived lung adenocarcinoma cell line H441 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, United States) and the human-derived neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y were used as cancer cells in this study along with the human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT) as normal cells. H441 was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (RPMI, FUJIFILM Wako Chemical, Osaka, Japan), SH-SY5Y was cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals), and Ham’s F-12 (Ham’s, FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals) and HaCaT were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals). RPMI and DMEM were mixed with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin, and 1% sodium pyruvate. EMEM was added to Ham’s mixed with 15% FBS, 1% penicillin, and 1% sodium pyruvate. All cells were cultured in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

2.2. X-Ray Irradiation of H441 and HaCaT

H441 and HaCaT were seeded into 12-well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells/well, and approximately 1 day later, the cells were irradiated with 2-Gy and 10-Gy X-rays from X-ray irradiation equipment (MBR1520R-3; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Administration and Accumulation of 131I-MIBG in SH-SY5Y and HaCaT Cells

SH-SY5Y and HaCaT were seeded into 12-well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells/well, and approximately 1 day later, the cells were pre-incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for approximately 5 min. After pre-incubation, the cells were incubated in 131I-MIBG (0.37, 1.85, 3.7 MBq/well) for 60 min at 37℃ and then the cells were washed twice with PBS (n = 4). The cells were lysed with 0.1 N NaOH, and a gamma counter (AccuFLEX γ7000, Hitachi Aloka Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure intracellular radioactivity. The results were expressed as percentage injected dose (%ID) / number of living cells determined by an automatic cell counter (LUNA FX7TM; Logo Biosystems, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea).

2.4. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay

An LDH assay kit (Nacalai Tesque, Tokyo, Japan) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol (n = 4) to measure the extracellular LDH released from H441 and HaCaT 1 day after X-ray irradiation. Similarly, the extracellular LDH released from SH-SY5Y and HaCaT 1 day after 131I-MIBG administration was measured (n = 4).

2.5. HMGB1 Assay

An HMGB1 ELISA Kit Exp (Shino-Test, Tokyo, Japan) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to measure extracellular HMGB1 from H441 and HaCaT after 1 day of X-ray irradiation (n = 4) and to measure the extracellular HMGB1 from SH-SY5Y and HaCaT after 1 day of 131I-MIBG administration (n = 4).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 8 statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to for comparisons between the two groups. Values of p ≤ 0.01 or ≤0.05 were accepted as indicating statistical significance.

3. Results

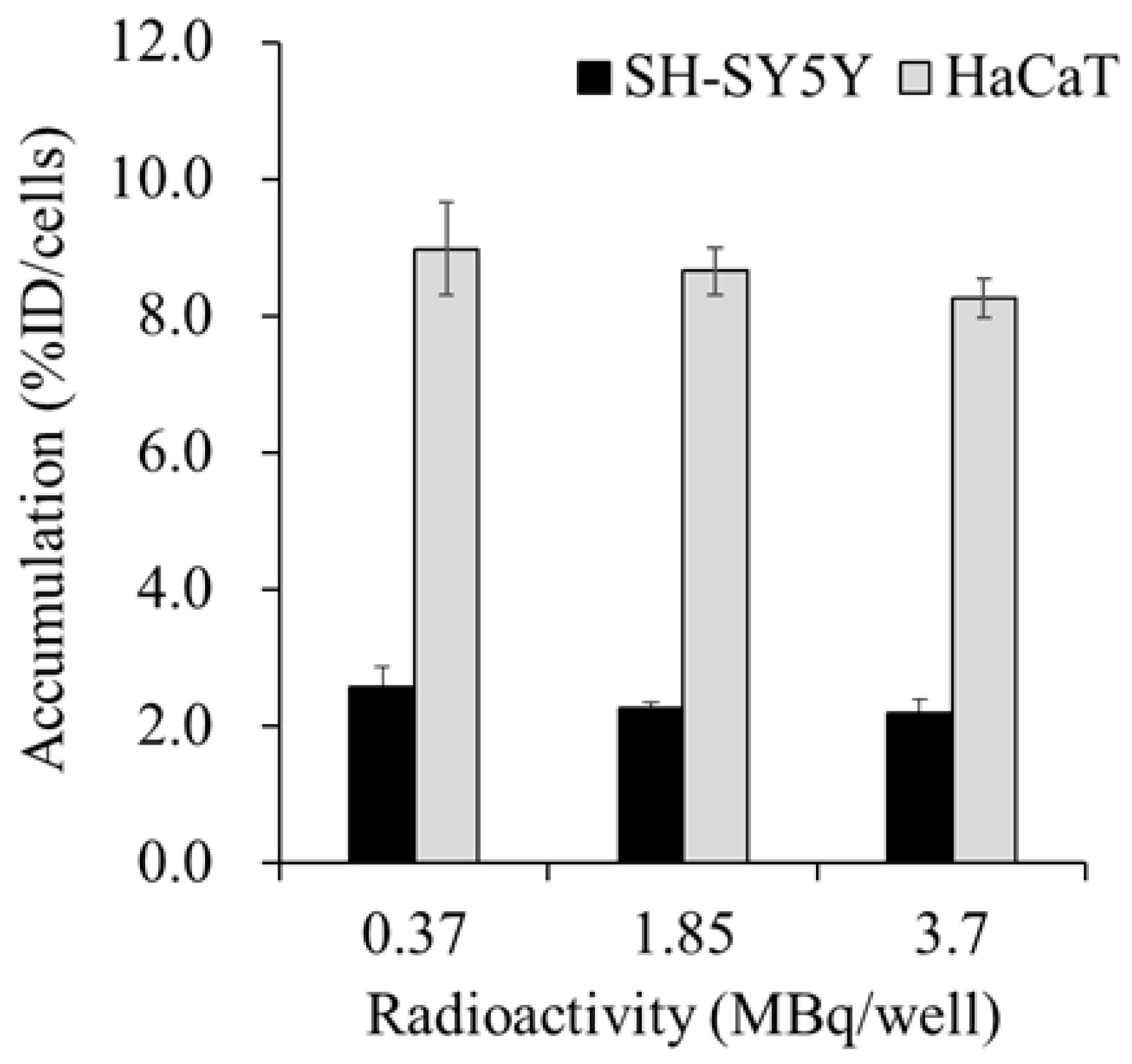

Figure 1 shows the accumulation of

131I-MIBG in the SH-SY5Y and HaCaT cells at 60 min after administration.

131I-MIBG accumulated more in the HaCaT cells than in the SH-SY5Y cells, and the accumulation of

131I-MIBG in both the SH-SY5Y and HaCaT cells was not significantly affected by the radioactivity of the administered

131I-MIBG.

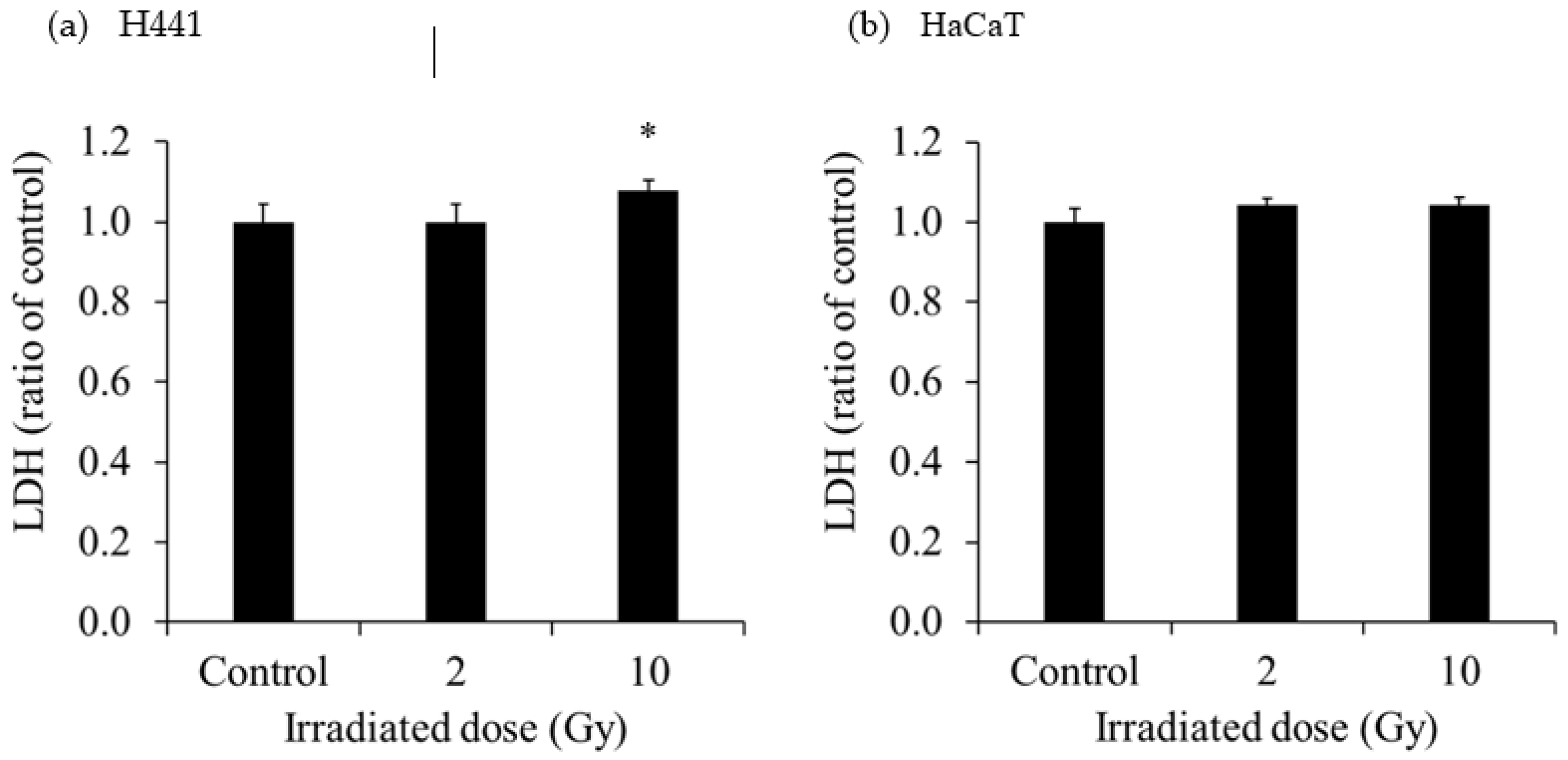

The extracellular LDH released in the culture medium of each cell is shown in

Figure 2. The extracellular LDH released from H441 was increased at 1 day after 10-Gy X-ray irradiation. However, the extracellular LDH released from HaCaT was not increased at 1 day after 2- and 10-Gy X-ray irradiation. The extracellular LDH released from SH-SY5Y was significantly increased after administration of 0.37 MBq

131I-MIBG, and the increase was greater with the higher radioactivity. On the other hand, the extracellular LDH released from HaCaT was not increased after administration of 0.37 MBq

131I-MIBG but was predominantly increased at 1.85 MBq and 3.7 MBq

131I-MIBG. The degree of increase in the release of LDH was much greater in HaCaT than in SH-SY5Y.

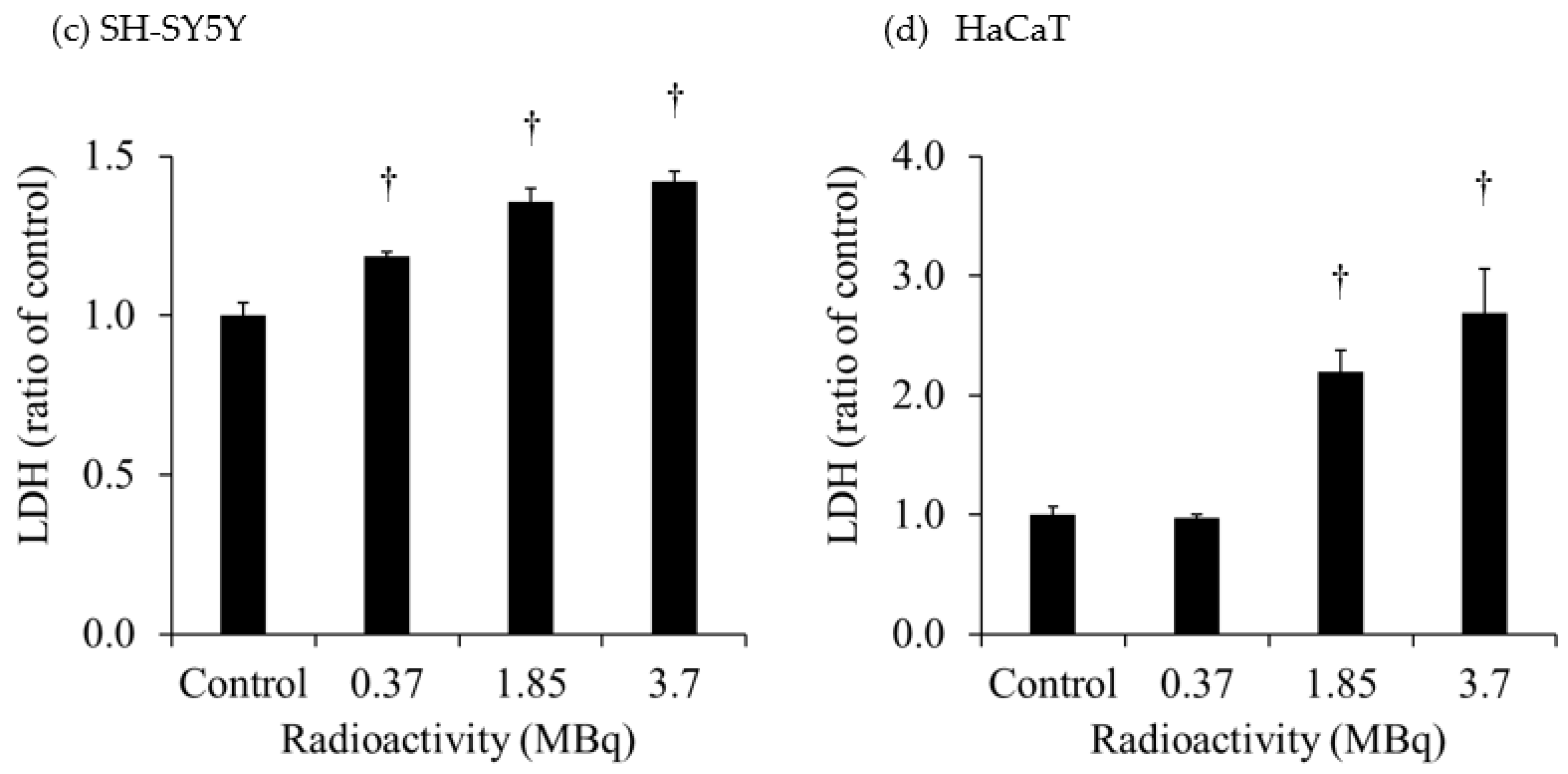

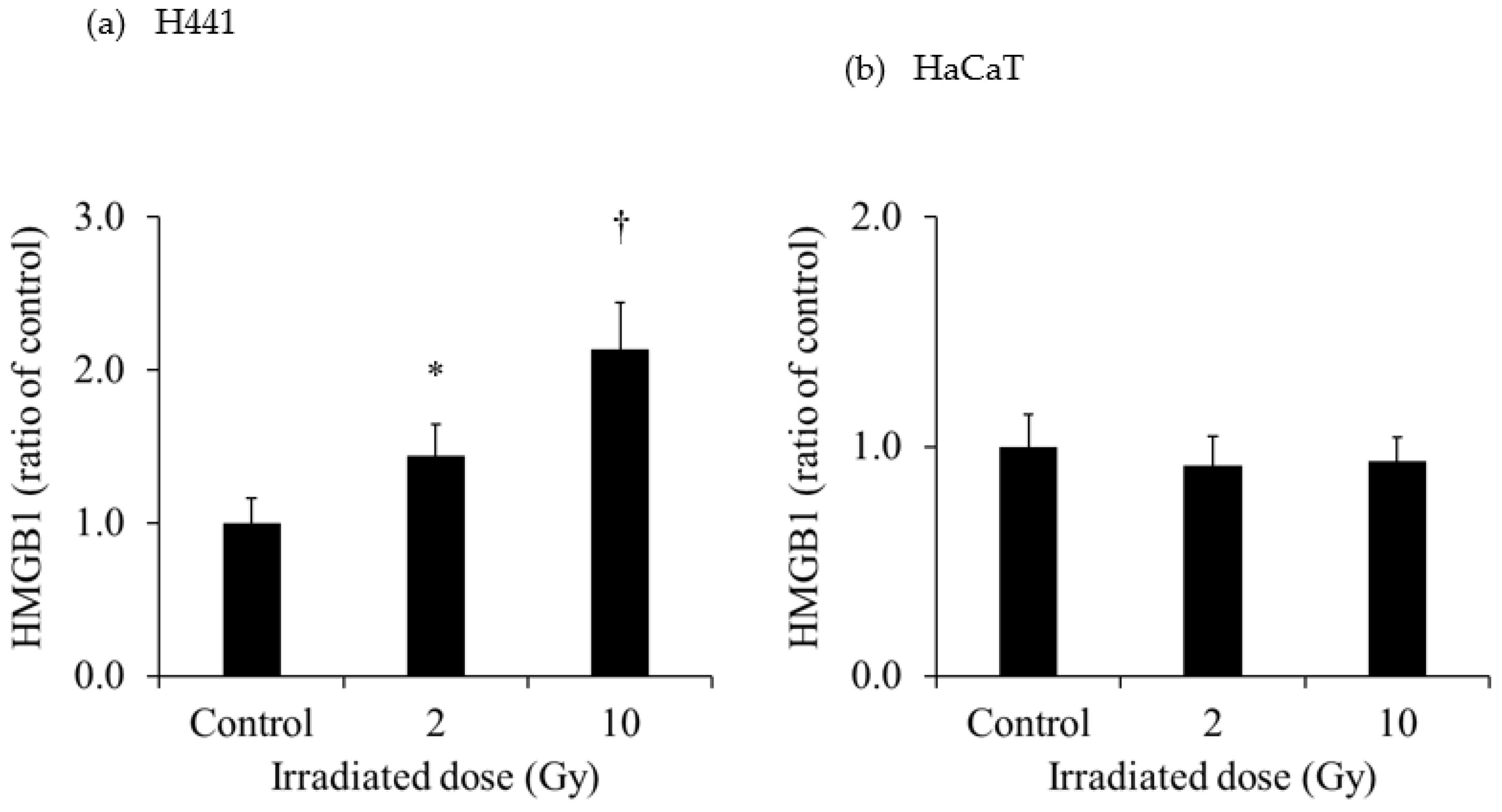

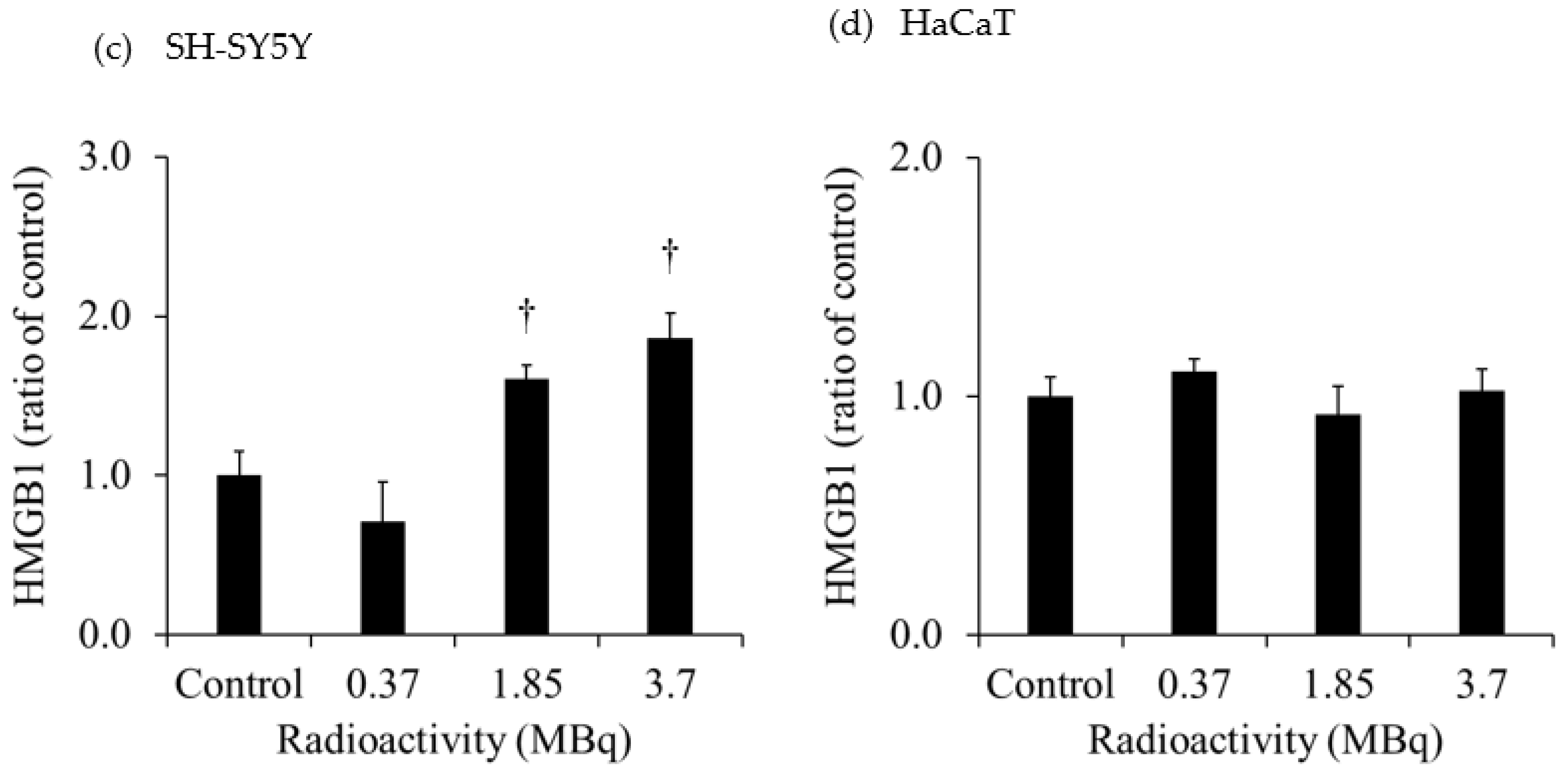

Figure 3 shows the extracellular HMGB1 in the culture medium of each cell line. The release of HMGB1 from H441 was significantly increased for both 2- and 10-Gy X-ray irradiation. Moreover, the release of HMGB1 from H441 was higher after 10-Gy than after 2-Gy X-ray irradiation. In contrast, there was no change in HMGB1 release in HaCaT after X-ray irradiation. Although there was no change in the HMGB1 release from SH-SY5Y administered 0.37 MBq of

131I-MIBG, HMGB1 release was significantly increased with 1.85 MBq and 3.7 MBq of

131I-MIBG. However, there was no change in HMGB1 release in HaCaT administered

131I-MIBG at any radioactivity dose.

4. Discussion

Although the use of radioimmunotherapy, which combines external radiotherapy with immunotherapy, is a known treatment option, only a few studies have combined immunotherapy with radiopharmaceutical therapy. Immunotherapy is initiated by the release of immunostimulatory DAMPs from cancer cells, but it has not been known if radiopharmaceutical therapy causes the release of immunostimulatory DAMPs from cancer cells. This study aimed to determine if HMGB1 would be released from human-derived cancer cells and normal cells after

131I-MIBG administration, with the goal of establishing useful radioimmunotherapy in the form of immunotherapy combined with

131I-MIBG, which has rarely been studied. Therefore, H441, a human-derived lung adenocarcinoma cell line that is an indication for radiotherapy [

24], and SH-SY5Y, a human-derived neuroblastoma cell line that is an indication for radiopharmaceutical therapy using

131I-MIBG, were selected on the basis of previous research [

19,

21] as the cancer cell lines in the present study. HaCaT cells established from adult male skin were used as the normal cell line because normal cells are difficult to culture [

25].

Assuming conventional external radiotherapy, we selected a 2-Gy X-ray dose, which is often used for single-dose conventional therapy. Additionally, assuming stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) with a higher single-dose of radiation, we selected 10-Gy as the X-ray dose, which is commonly used in SBRT [

26,

27]. SBRT is frequently used to treat lung cancer [

28]. In the present study, we observed that the extracellular LDH released from H441 was increased at 1 day after 10-Gy X-ray irradiation (

Figure 2). However, the extracellular LDH released from HaCaT was not increased at 1 day after 2- and 10-Gy X-ray irradiation. LDH is an enzyme that catalyzes conversion of pyruvate to lactate in the glycolytic process [

29]. Normally, LDH remains in the cytoplasm, but when the cell membrane is damaged, LDH is excreted out of the cell [

30]. Hence, measurement of LDH release is a good method for detecting cell death. In our study, extracellular HMGB1 release from H441 was significantly increased at 1 day after 2- and 10-Gy X-ray irradiation (

Figure 3). Moreover, the increase was more pronounced for 10-Gy than for 2-Gy irradiation. However, the amount of HMGB1 released from the HaCaT cells by irradiation did not change for both 2-Gy and 10-Gy X-ray irradiation. These results suggest that 10-Gy X-ray irradiation disrupted the cell membranes of H441 cells and released HMGB1. In addition, HaCaT cell death was not observed at 1 day after X-ray irradiation, and HMGB1 release did not occur. In actual clinical radiotherapy, irradiating lung cancer with 10 Gy (assuming SBRT) does not necessarily mean that the skin is exposed to 10-Gy of X-ray irradiation. Immune cells activated by DAMPs, such as HMGB1, recognize the cells from which it was released and attack living cells. Therefore, by maximizing the HMGB1 released only from cancer cells, it could be possible to suppress damage to the skin and inflict further damage only to the tumor.

In the present study, we observed that the radiopharmaceutical therapeutic agent

131I-MIBG had accumulated more in HaCaT cells than in SH-SY5Y cells at 60 min after administration (

Figure 1).

131I-MIBG is mainly taken up into cells via the norepinephrine transporter, which has been shown to be abundantly expressed in neuroblastoma cells [

31]. In addition,

131I-MIBG has an affinity for the influx drug transporter organic cation / carnitine transporter (OCTN)1, OCTN2, organic cation transporter (OCT)1–3, and the efflux drug transporter multidrug resistance proteins (MRP)1 and MRP4 [

32,

33]. Therefore, the high accumulation of

131I-MIBG in HaCaT cells may be due to the high expression of OCTNs and OCTs. It is also possible that the expression of MRPs is higher in SH-SY5Y than in HaCaT cells.

The extracellular HMGB1 released from SH-SY5Y was significantly increased after administration of 1.85 MBq and 3.7 MBq 131I-MIBG. Similarly, the extracellular LDH significantly increased after administration of 1.85 MBq and 3.7 MBq 131I-MIBG. These results suggest that 131I-MIBG administration caused cell death and the release of HMGB1. In HaCaT, the extracellular LDH was also significantly increased after administration of 1.85 MBq and 3.7 MBq 131I-MIBG, and the degree of increase in the release of LDH was much greater in HaCaT than in SH-SY5Y. The accumulation of 131I-MIBG also was greater in HaCaT than in SH-SY5Y, suggesting that more cell death and LDH release occurred in HaCaT. However, no HMGB1 was released from HaCaT after the administration of 131I-MIBG. Although this study focused on HMGB1, one of the DAMPs that activate immunity through various pathways, other DMAPs, such as adenosine 5'-triphosphate and calreticulin, possible were released in increased amounts in HaCaT.

It was shown that reducing the radioactivity of administered 131I-MIBG may help reduce side effects by minimizing damage to normal cells caused by attacking cancer cells, not only because of the damage caused by β-ray radiation, but also because of the damage caused by activation of immune cells induced by HMGB1 release. However, elucidation of the mechanism by which HMGB1 release is caused by X-ray irradiation and the radiopharmaceutical therapeutic agent dose is not clear and requires further investigation.

5. Conclusion

HMGB1 was released in human-derived lung cancer cells after X-ray irradiation and in human-derived neuroblastoma cells after 131I-MIBG administration, but HMGB1 was not released in normal human epidermal keratinocyte cells under the same conditions. These findings indicate that the abscopal effect that can occur after X-ray irradiation and 131I-MIBG administration possibly enhances the cancer therapeutic effect without causing excessive damage to normal cells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S., M.K.; Methodology, A.M, M.K.; Investigation, K.S, R.H, J.Y, Y.H, Y.H, J.Y, T.W; Resources, R.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, K.S.; Writing—review and editing, K.K., M.K.; and Supervision, K.K., M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 22K19504, 22H03016, 23K21423, 23K24277) and the Network-type Joint Usage/Research Center for Radiation Disaster Medical Science.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mikie Ohtake and the other staff of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Kanazawa University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brix, N.; Tiefenthaller, A.; Anders, H.; Belka, C.; Lauber, K. Abscopal, immunological effects of radiotherapy: Narrowing the gap between clinical and preclinical experiences. Immunol Rev 2017, 280, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.E.; Adashek, J.J.; Lin, S.H.; Subbiah, V. The abscopal effect in patients with cancer receiving immunotherapy. Medicine 2023, 4, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Farhood, B.; Eleojo Musa, A.; Taeb, S.; Najafi, M. Damage-associated molecular patterns in tumor radiotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 86, 106761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, J.; Vacchelli, E.; Aranda, F.; Castoldi, F.; Eggermont, A.; Cremer, I.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Fucikova, J.; Galon, J.; Spisek, R.; Tartour, E.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Trial watch: Immunogenic cell death inducers for anticancer chemotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e1008866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysko, D.V.; Garg, A.D.; Kaczmarek, A.; Krysko, O.; Agostinis, P.; Vandenabeele, P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, E.; Lord, J.M.; Hazeldine, J. The immune suppressive properties of damage associated molecular patterns in the setting of sterile traumatic injury. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1239683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ji, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Shi, L.; Zhou, F.; Chen, W.R.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Stimulation of dendritic cells by DAMPs in ALA-PDT treated SCC tumor cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 44688–44702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.H.; Chan, L.C.; Li, C.W.; Hsu, J.L.; Hung, M.C. Mechanisms controlling PD-L1 expression in cancer. Mol Cell 2019, 76, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, R.; Zietse, M.; Dumoulin, D.W.; Hendrikx, J.J.M.A.; Aerts, J.G.J.V.; van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Koch, B.C.P.; Sleijfer, S.; van Leeuwen, R.W.F. Alternative dosing strategies for immune checkpoint inhibitors to improve cost-effectiveness: a special focus on nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Lancet Oncol 2022, 23, e552–e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Unceta, N.; Burgueño, I.; Jiménez, E.; Paz-Ares, L. Durvalumab in NSCLC: Latest evidence and clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2018, 10, 1758835918804151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Tait, S.W.G. Targeting immunogenic cell death in cancer. Mol Oncol 2020, 14, 2994–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janho Dit Hreich, S.; Benzaquen, J.; Hofman, P.; Vouret-Craviari, V. To inhibit or to boost the ATP/P2RX7 pathway to fight cancer—that is the question. Purinergic Signal 2021, 17, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysko, D.V.; Garg, A.D.; Kaczmarek, A.; Krysko, O.; Agostinis, P.; Vandenabeele, P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, G.P.; Rowe, D.C.; Rietdijk, S.T.; Herbst, R.; Coyle, A.J. HMGB1 and RAGE in Inflammation and Cancer. Annu Rev Immunol 2010, 28, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkopf, P.; Frey, B.; Mantel, F.; Ott, O.J.; Weiss, E.M.; Sieber, R.; Janko, C.; Sauer, R.; Fietkau, R.; Gaipl, U.S. Application of hyperthermia in addition to ionizing irradiation fosters necrotic cell death and HMGB1 release of colorectal tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 391, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashnamoorthy, S.; Jeyasingh, E.; Rajamanickam, K. Validation of esophageal cancer treatment methods from 3D-CRT, IMRT, and Rapid Arc plans using custom Python software to compare radiobiological plans to normal tissue integral dosage. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 2023, 28, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Alfonso, J.C.; Parsai, S.; Joshi, N.; Godley, A.; Shah, C.; Koyfman, S.A.; Caudell, J.J.; Fuller, C.D.; Enderling, H.; Scott, J.G. Temporally feathered intensity-modulated radiation therapy: A planning technique to reduce normal tissue toxicity. Med Phys 2018, 45, 3466–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, K.H.; Ren, W.; Han, R.Y.; Xiao, L.H.; Yu, J.; Tan, R.Z.; Wang, L.; Liao, D.Z. Huanglian Jiedu plaster ameliorated X-ray-induced radiation dermatitis injury by inhibiting HMGB1-mediated macrophage-inflammatory interaction. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 302, 115917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; Bodei, L.; McDevitt, M.R.; Nedrow, J.R. Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: clinical advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, M.C.; Patel, R.B.; Anderson, C.J. Combined. targeted radiopharmaceutical therapy and immune checkpoint blockade: From preclinical advances to the clinic. J Nucl Med 2022, 63, 1636–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, S.G.; Matthay, K.K. Radiolabeled metaiodobenzylguanidine for the treatment of neuroblastoma. Nucl Med Biol 2008, Suppl 1, S35–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.S.; Gains, J.E.; Moroz, V.; Wheatley, K.; Gaze, M.N. A systematic review of 131I-meta iodobenzylguanidine molecular radiotherapy for neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer 2014, 50, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, J. Current status and future perspective on molecular imaging and treatment of neuroblastoma. Semin Nucl Med 2023, 53, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, S.K.; Hau, E. Radiotherapy treatment for lung cancer: Current status and future directions. Respirology 2020, 25, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, P.; Petrussevska, R.T.; Breitkreutz, D.; Hornung, J.; Markham, A.; Fusenig, N.E. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol 1988, 106, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarudis, S.; Karlsson, A.; Bäck, A. Surface guided frameless positioning for lung stereotactic body radiation therapy. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2021, 22, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, T.; Zhang, J.; Wolf, J.; Kayode, O.; Higgins, K.A.; Bradley, J.; Yang, X.; Schreibmann, E.; Roper, J. Lung SBRT treatment planning: a study of VMAT arc selection guided by collision check software. Med Dosim 2023, 48, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, E.K.; Swaminath, A. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in the management of non-small-cell lung cancer: Clinical impact and patient perspectives. Lung Cancer 2018, 9, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Qiao, T.; Li, X.; Jia, L.; Han, Y. Lactate dehydrogenase A: A key player in carcinogenesis and potential target in cancer therapy. Cancer Med 2018, 7, 6124–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.S.; Groß, C.J.; Dreier, R.F.; Saller, B.S.; Mishra, R.; Gorka, O.; Heilig, R.; Meunier, E.; Dick, M.S.; Ćiković, T.; Sodenkamp, J.; Médard, G.; Naumann, R.; Ruland, J.; Kuster, B.; Broz, P.; Groß, O. The inflammasome drives GSDMD-independent secondary pyroptosis and IL-1 release in the absence of caspase-1 protease activity. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 3846–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit-Taskar., N.; Modak, S. Pandit-Taskar. N.; Modak, S. Norepinephrine transporter as a target for imaging and therapy. J Nucl Med 2017, 58, 39S–53S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Mizutani, A.; Muranaka, Y.; Nishi, K.; Komori, H.; Nishii, R.; Shikano, N.; Nakanishi, T.; Tamai, I.; Kawai, K. Biological distribution of orally administered [123I]MIBG for estimating gastrointestinal tract absorption. Pharmaceutics 2021, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Mizutani, A.; Nishi, K.; Muranaka, Y.; Nishii, R.; Shikano, N.; Nakanishi, T.; Tamai, I.; Kleinerman, E.S.; Kawai, K. [131I]MIBG exports via MRP transporters and inhibition of the MRP transporters improves accumulation of [131I]MIBG in neuroblastoma. Nucl Med Biol 2020, 90–91, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).