Submitted:

28 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

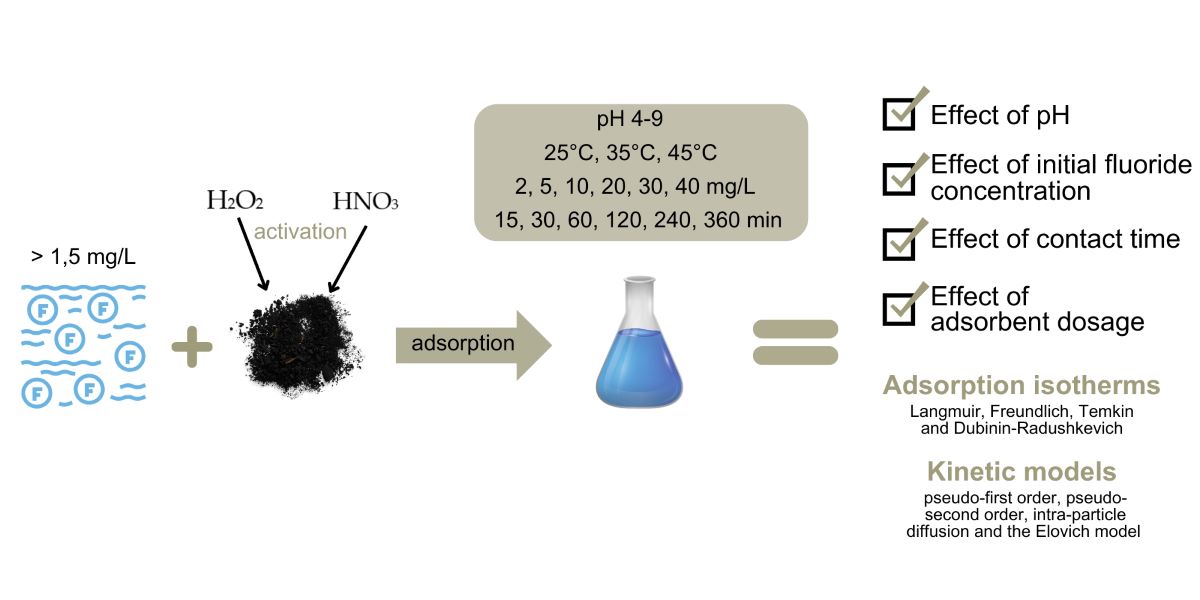

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of adsorbents

2.2. Fluoride Adsorption Experiments

2.3. Adsorption isotherm and kinetic analysis

3. Results and Discussion

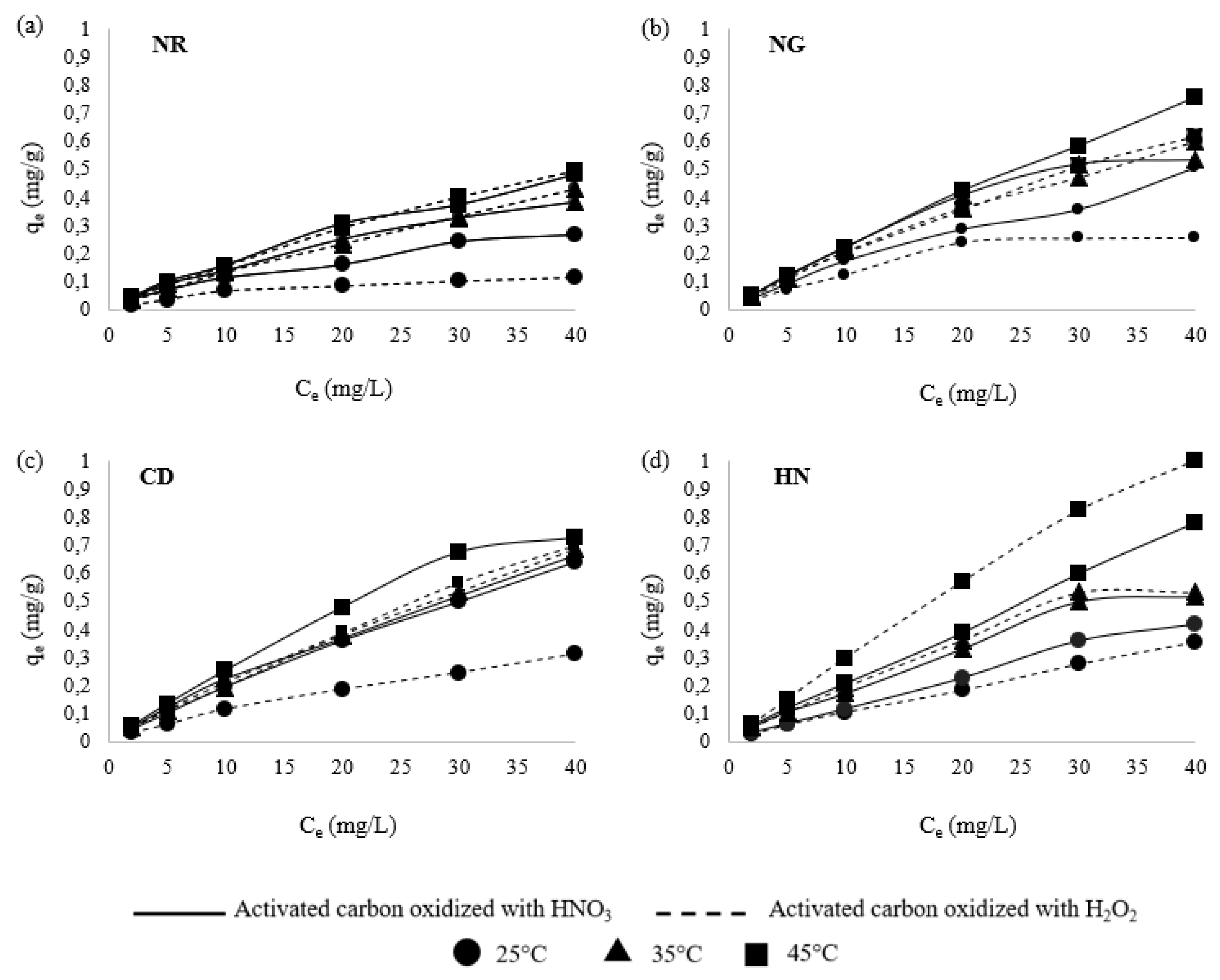

3.1. Effect of Initial Fluoride Concentration

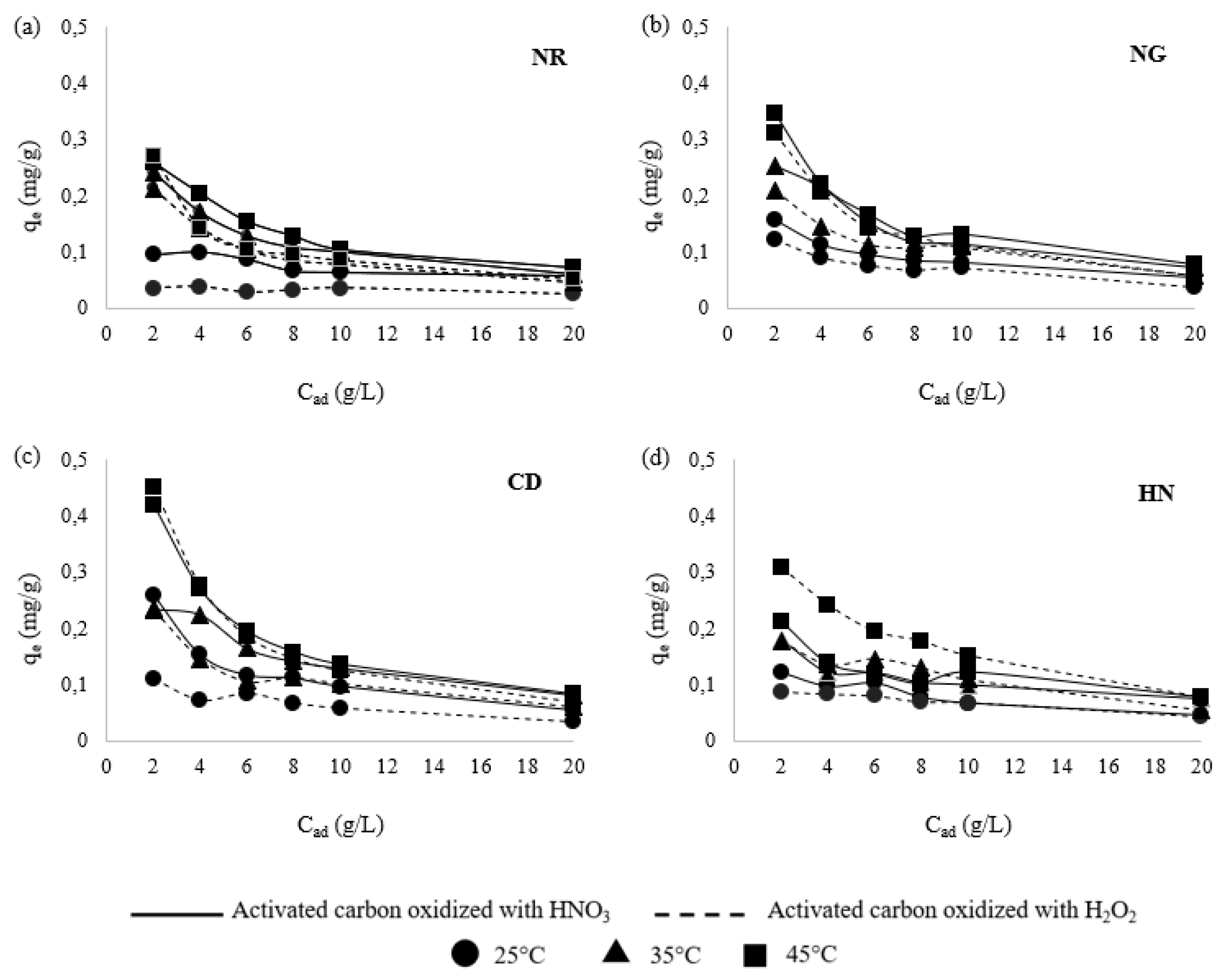

3.2. Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

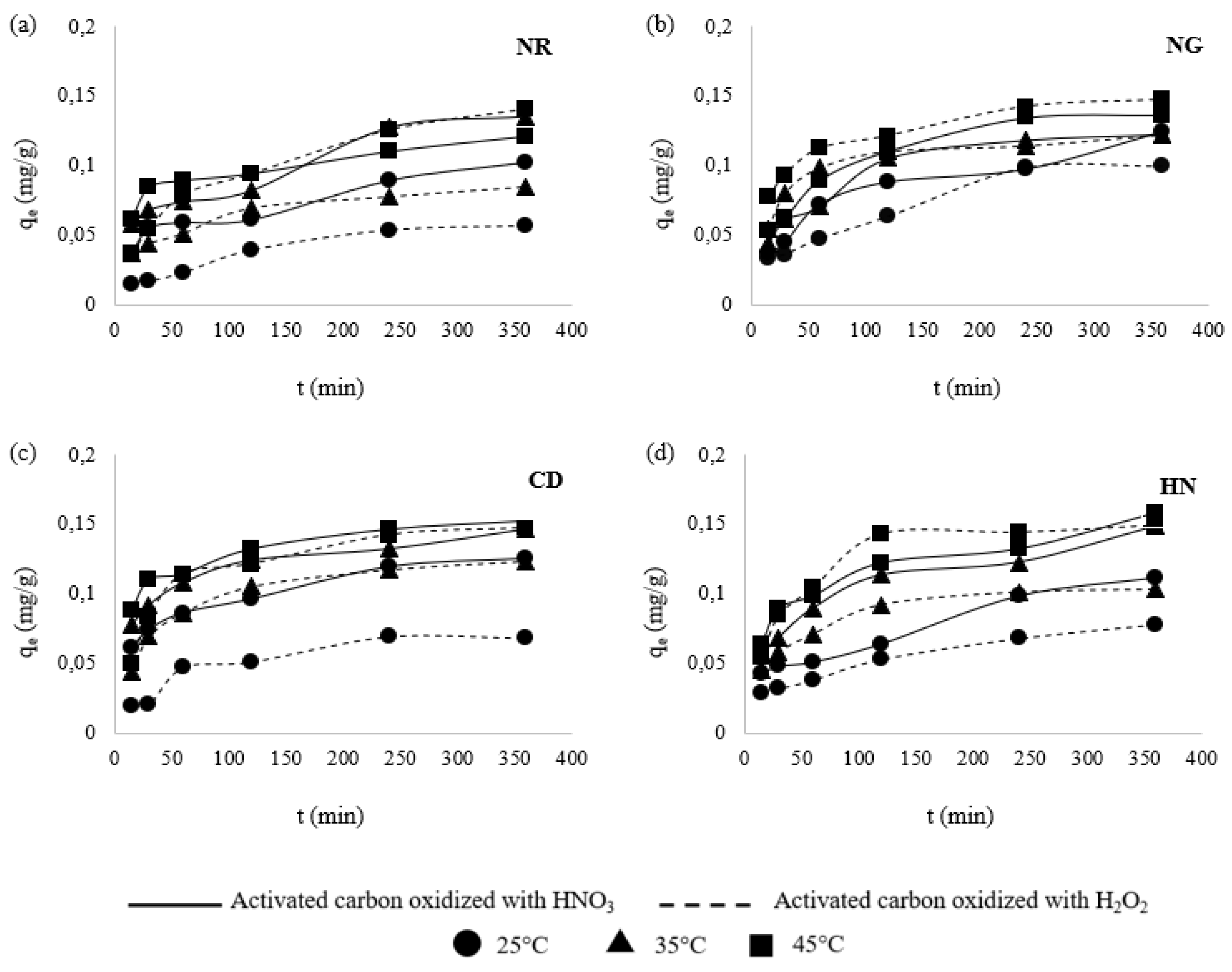

3.3. Effect of Contact Time

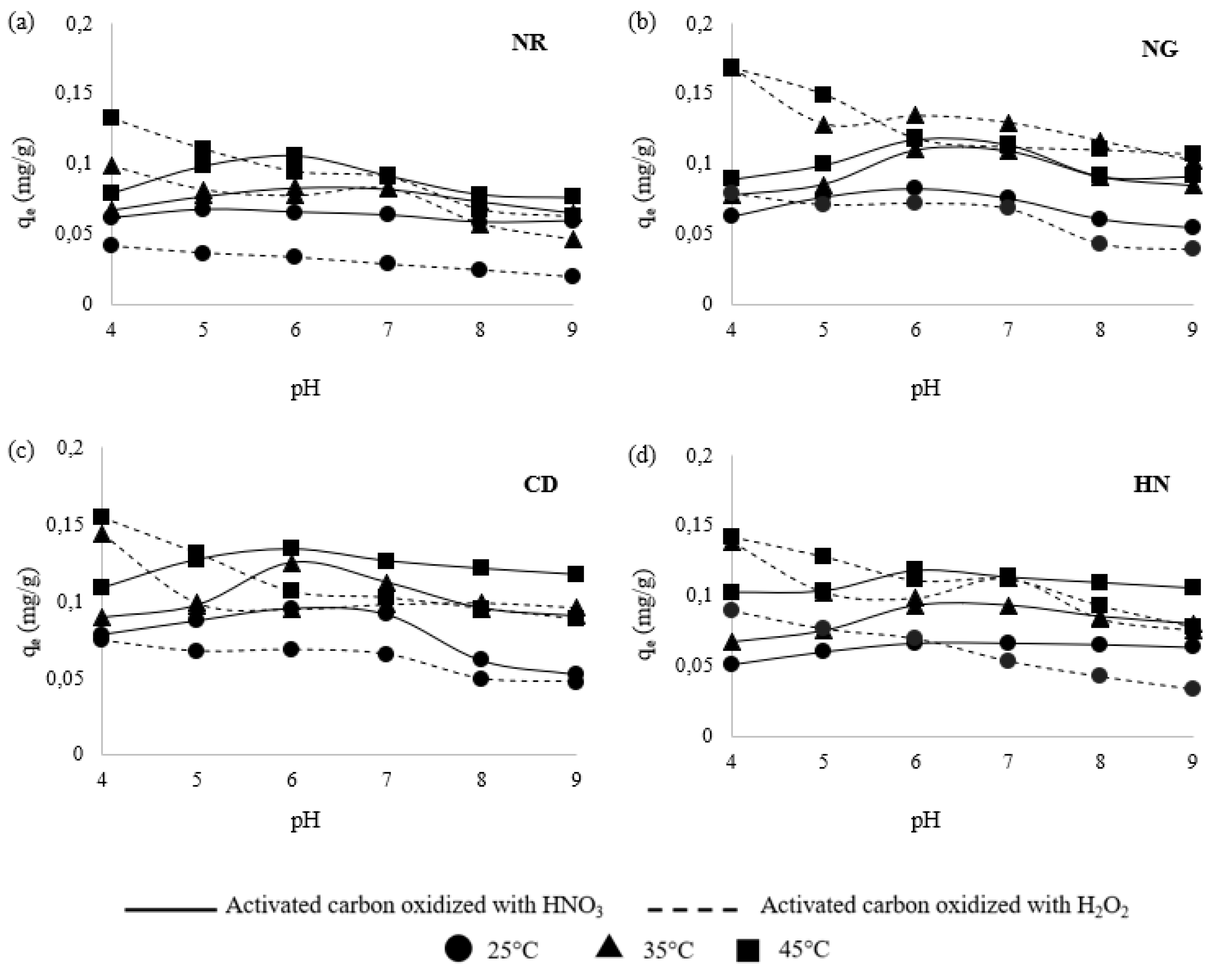

3.4. Effect of pH

3.5. Adsorption Isotherms

3.6. Kinetic Models

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fluoride in Drinking-water. IWA Publishing, London, United Kingdom, 2006.

- Gebrewold, B.D.; Kijjanapanich, P.; Rene, E.R.; Lens, P.N.L.; Annachhatre, A.P. Fluoride removal from groundwater using chemically modified rice husk and corn cob activated carbon. Environ. Technol. 2019, 40(22), 2913–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar. S; Murugesh, S.; Sivasankar, V.; Darchen, A.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Chaabane, T. Low-cost fluoride adsorbents prepared from a renewable biowaste: Syntheses, characterization and modeling. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 3004–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhta, S.; Sadaoui, Z.; Bouazizi, N.; Samir, B.; Allalou, O.; Devouge-Boyer, C.; Mignot, M.; Vieillar, J. Functional activated carbon: from synthesis to groundwater fluoride removal. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 2332–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Mishra, P.C.; Patel, R. Fluoride adsorption from aqueous solution by a hybrid thorium phosphate composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A. Removal of fluoride from drinking water using aluminum hydroxide coated activated carbon prepared from bark of Morinda tinctorial. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 2653–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; De, S. Adsorptive removal of fluoride by activated alumina doped cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) mixed matrix membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 125, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Guan, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Lin, M.; You, G.; Tan, S.; Yu, X.; Ge, M. Enhanced fluoride removal behavior and mechanism by dicalcium phosphate from aqueous solution. Environ. Technol. 2019, 40(28), 3668–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, W.Z.; Deng, Z.Y. A comprehensive review of adsorbents for fluoride removal from water: performance, water quality assessment and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 1362–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Yan, W.; Feng, J. Synergistic fluoride adsorption by composite adsorbents synthesized from different types of materials—A review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medikondu, K. Potable water defluoridation by lowcost adsorbents from Mimosideae family fruit carbons: A comparative study. Int. Lett. Chem. Phys. Astron. 2015, 56, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Q.; Krua, L.S.N.; Yi, R.; Zou, R.; Li, X.; Huang, P. Application Progress of New Adsorption Materials for Removing Fluorine from Water. Water, 2023, 15, 646.

- Asaithambi, P.; Beyene, D.; Raman, A.; Alemyehu, E. Removal of pollutants with determination of power consumption from landfill leachate wastewater using an electrocoagulation process: optimization using response surface methodology (RSM). Appl. Water Sci. 2015, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, N.; Mulualem, Y.; Fito, J. Adsorption of fluoride from aqueous solution and groundwater onto activated carbon of avocado seeds. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2020, 5, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J., Zhang, C. Preparation of nitric acid modified powder activated carbon to remove trace amount of Ni(II) in aqueous solution. Water Sci. Technol. 2019, 80(1), 86-97.

- Yao, S.; Zhang, J.; Shen, D.; Xiao, R.; Gu, S.; Zhao, M.; Liang, J. Removal of Pb(II) from water by the activated carbon modified by nitric acid under microwave heating. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 463, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, A.; Park, M.; Park, S.J. Current progress on the surface chemical modification of carbonaceous materials. Coatings. 2019, 9(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Park, S.W.; Su, J.F.; Yu, Y.H.; Heo, J.E; Kim, K.D.; Huang, C.P. The adsorption characteristics of fluoride on commercial activated carbon treated with quaternary ammonium salts (Quats). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingombe, P.; Saha, B.; Wakeman, R.J. Surface modification and characterization of a coal-based activated carbon. Carbon. 2005, 43, 3132–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar. A., Minocha, A.K. Conventional and non-conventional adsorbens for removal of pollutants from water-A review. Indian J. Chem.Technol. 2006, 13, 2013-2017.

- Yin, C.Y.; Aroua, M.K.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Review of modifications of activated carbon for enhancing contaminant uptakes from aqueous solutions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 52, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmy, R., Indraneel, P., Viswanathan, B. Surface functionalities of nitric acid treated carbon – A density functional theory based vibrational analysis. Indian J. Chem. 2009, 48, 352-356.

- Ho, S.M. A Review of chemical activating agent on the properties of activated carbon. Int. J. Chem. Res. 2022, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Senewirathna, D.S.G.D.; Thuraisingam, S.; Prabagar, S.; Prabagar, J. Fluoride removal in drinking water using activated carbonpreparedfrom palmyrah (Borassusflabellifer) nutshells. CRGSC, 2022, 5(2022), 100304.

- Ergović Ravančić, M.; Habuda-Stanić, M. Equilibrium and kinetics studies for the adsorption of fluoride onto commercial activated carbons using fluoride ion-selective electrode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 8137–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, H.; Pangeni, B.; Ghimire, K.N.; Inoue, K.; Ohto, K.; Kawakita, H.; Alam, S. Adsorption behavior of orange waste gel for some rare earth ions and its application to the removal of fluoride from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 195-196, 289-296.

- Swain, S.K.; Mishra, S.; Patnaik, T.; Patel, R.; Jha, U.; Dey, R. Fluoride removal performance of a new hybrid sorbent of Zr(IV)-ethylenediamine. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 184, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.J.; Wang, N.X.; Tan, J.; Chen, J.Q.; Zhong, W.Y. Kinetic and equilibrium of cafradine adsorption onto peanut husk. Desalin. Water Treat. 2012, 37, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeivelni, K.; Khodadoust, A.P. Adsorption of fluoride onto crystalline titanium dioxide: Effect of pH, ionic strength and co-existing ions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 394, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivasankar, V.; Murugesh, S.; Rajkumar, S.; Darchen, A. Cerium dispersed in carbon (CeDC) and its adsorption behavior: A first example of tailored adsorbent for fluoride removal from drinking water. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 214, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.C.; Forster, C.F. Removal of hexavalent chromium using sphagnum moss peat. Water Res. 1993, 27(7), 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özacar, M.; Şengil, I.A. Adsorption of metal complex dyes from aqueous solutions by pine sawdust. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96(7), 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.K.; Mishra, S.; Patnaik, T.; Patel, R.; Jha, U.; Dey, R. Fluoride removal performance of a new hybrid sorbent od Zr(IV)-ethylenediamine. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 184, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K., Kaushik, C.P.; Haritash, A.K.; Kansal, A.; Rani, N. Defluoridation of groundwater using brick power as an adsorbent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 128(2-3), 289-293.

- Onyango, M.S.; Kojima, Y.; Aoyi, O.; Bernardo, E.C.; Matsuda, H. Adsorption equilibrium modeling and solution chemistry dependence of fluoride removal from water by trivalent-cation-exchanged zeolite F-9. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 279(2), 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandarpour, A.; Onyango, M.; Ochieng, A.; Asai, S. Removal of fluoride ions from aqueous solution at low pH using schwertmannite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152(2), 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujana, M.G.; Pradhan, H.K.; Anand, S. Studies on sorption of some geomaterials for fluoride removal from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161(1), 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoob, S.; Gupta, A.K. Insights into isotherm making in the sorptive removal of fluoride from drinking water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152(3), 976–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, R.; Mondal, N.K.; Das, B.; Roy, P.; Pal, K.C.; Das, C.; Baneerjee, A.; Datta, J.K. Eggshell powder as an adsorbent for removal of fluoride from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J. Chem. 2012, 9, 1457–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.J.; McGinley, P.M.; Katz, L.E. A distributed reactivity model for sorption by soils and sediments – Conceptual basis and equilibrium assessments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1992, 26(10), 1955–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehr, M.N.; Sivasankar, V.; Zarrabi, M.; Kumar, M.S. Surface modification of pumice enhancing its fluoride adsorption capacity: An insight into kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, Y.; Lin, X.; Su, X.; Zhang, Y. Removal of fluoride from groundwater by adsorption onto La(III)-Al(III) loaded scoria adsorbent. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 303, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activated carbon | Activated carbon oxidized with HNO3 | Activated carbon oxidized with H2O2 |

|---|---|---|

| Norit ROW 0,8 SUPRA | NR-HNO3 | NR-H2O2 |

| Norit GAC 1240 | NG-HNO3 | NG-H2O2 |

| Cullar D | CD-HNO3 | CD-H2O2 |

| Hidraffyn 30 N | HN-HNO3 | HN-H2O2 |

| Isotherm | Langmuir | Freundlich | Temkin | Dubinin- Radushkevich |

| Equation | ||||

| qe = equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g); qm = maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g); KL = Langmuir isotherm constant(L/mg); Ce = equilibrium concentration of adsorbate (mg/L); n = Freundlich adsorption intensity; KF = Freundlich isotherm constant (mg/g)(mg/L)1/n; R = universal gas constant (J/molK); T= temperature (K); AT= Temkin equilibrium binding constant (L/g); KDR – Dubinin-Raduschkevich constant (mol2/kJ2); ε – Polanyi potential | ||||

| Kinetic model | Pseudo-first order | Pseudo-second order | Intra-particle diffusion | Elovich |

| Equation | ||||

| qm1 – equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g); qt – adsorption capacity in time t (mg/g); t – time (min); k1 – pseudo-first-order adsorption rate constant (min-1); qm2 – equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g); k2 – pseudo-second-order adsorption rate constant (g/mg min); kid – interparticle diffusion rate constant (mg/g min1/2); C – thickness of the boundary layer; α – initial adsorption rate (mg/g min); β – desorption constant (g/mg) | ||||

| Isotherm | |||||||||||||

| Langmuir | Freundlich | Temkin | Dubinin- Radushkevich | ||||||||||

| qm (mg/ g) | KL (L/ mg) | R2 | n | KF (mg/g) (L/mg)1/n | R2 | AT (L/ g) | BT | R2 | qm (mg/ g) | KDR (mol2/kJ) | R2 | ||

| 25°C | NR-HNO3 | 0,417 | 0,044 | 0,889 | 1,554 | 0,026 | 0,986 | 0,686 | 0,075 | 0,911 | 0,164 | 1·10-6 | 0,653 |

| NG-HNO3 | 1,089 | 0,021 | 0,863 | 1,257 | 0,027 | 0,993 | 0,554 | 0,141 | 0,903 | 0,738 | 2·10-7 | 0,458 | |

| CD-HNO3 | 2,112 | 0,012 | 0,739 | 1,151 | 0,030 | 0,998 | 0,523 | 0,189 | 0,886 | 0,337 | 1·10-6 | 0,709 | |

| HN-HNO3 | 1,565 | 0,010 | 0,588 | 1,146 | 0,019 | 0,995 | 0,461 | 0,129 | 0,877 | 0,221 | 2·10-6 | 0,672 | |

| NR-H2O2 | 0,153 | 0,067 | 0,852 | 1,492 | 0,012 | 0,904 | 0,779 | 0,034 | 0,864 | 0,087 | 2·10-6 | 0,849 | |

| NG-H2O2 | 0,271 | 0,103 | 0,835 | 1,542 | 0,026 | 0,935 | 0,865 | 0,068 | 0,809 | 0,178 | 1·10-6 | 0,808 | |

| CD-H2O2 | 0,578 | 0,028 | 0,931 | 1,327 | 0,021 | 0,997 | 0,569 | 0,088 | 0,922 | 0,178 | 1·10-6 | 0,718 | |

| HN-H2O2 | 0,983 | 0,014 | 0,809 | 1,888 | 0,016 | 0,999 | 0,486 | 0,103 | 0,881 | 0,188 | 2·10-6 | 0,714 | |

| 35°C | NR-HNO3 | 0,656 | 0,037 | 0,961 | 1,375 | 0,029 | 0,993 | 0,642 | 0,111 | 0,939 | 0,239 | 1·10-6 | 0,776 |

| NG-HNO3 | 1,047 | 0,034 | 0,937 | 1,224 | 0,035 | 0,981 | 0,653 | 0,170 | 0,957 | 0,677 | 2·10-7 | 0,539 | |

| CD-HNO3 | 1,557 | 0,021 | 0,948 | 1,199 | 0,036 | 0,996 | 0,579 | 0,191 | 0,914 | 0,371 | 1·10-6 | 0,773 | |

| HN-HNO3 | 1,129 | 0,025 | 0,847 | 1,275 | 0,035 | 0,993 | 0,596 | 0,160 | 0,903 | 0,313 | 1·10-6 | 0,710 | |

| NR-H2O2 | 1,010 | 0,018 | 0,866 | 1,232 | 0,023 | 0,999 | 0,526 | 0,122 | 0,897 | 0,229 | 1·10-6 | 0,706 | |

| NG-H2O2 | 1,327 | 0,023 | 0,986 | 1,203 | 0,035 | 0,998 | 0,639 | 0,159 | 0,911 | 0,352 | 1·10-6 | 0,759 | |

| CD-H2O2 | 1,197 | 0,016 | 0,861 | 1,178 | 0,032 | 0,999 | 0,534 | 0,201 | 0,891 | 0,362 | 1·10-6 | 0,719 | |

| HN-H2O2 | 1,263 | 0,024 | 0,867 | 1,213 | 0,033 | 0,991 | 0,584 | 0,172 | 0,919 | 0,333 | 1·10-6 | 0,731 | |

| 45°C | NR-HNO3 | 0,927 | 0,028 | 0,927 | 1,294 | 0,031 | 0,995 | 0,599 | 0,128 | 0,922 | 0,280 | 1·10-6 | 0,759 |

| NG-HNO3 | 2,465 | 0,013 | 0,959 | 1,129 | 0,036 | 0,991 | 0,545 | 0,223 | 0,902 | 0,631 | 3·10-7 | 0,447 | |

| CD-HNO3 | 1,929 | 0,021 | 0,911 | 1,158 | 0,042 | 0,992 | 0,601 | 0,232 | 0,935 | 0,449 | 1·10-6 | 0,771 | |

| HN-HNO3 | 2,409 | 0,013 | 0,609 | 1,182 | 0,039 | 0,996 | 0,551 | 0,222 | 0,855 | 0,390 | 1·10-6 | 0,682 | |

| NR-H2O2 | 1,367 | 0,015 | 0,970 | 1,167 | 0,025 | 0,999 | 0,522 | 0,147 | 0,914 | 0,276 | 1·10-6 | 0,745 | |

| NG-H2O2 | 1,496 | 0,021 | 0,959 | 1,203 | 0,035 | 0,998 | 0,639 | 0,159 | 0,911 | 0,352 | 1·10-6 | 0,759 | |

| CD-H2O2 | 1,950 | 0,013 | 0,902 | 1,148 | 0,036 | 0,999 | 0,556 | 0,206 | 0,898 | 0,378 | 1·10-6 | 0,721 | |

| HN-H2O2 | 4,570 | 0,009 | 0,950 | 1,076 | 0,046 | 0,998 | 0,574 | 0,310 | 0,911 | 0,554 | 1·10-6 | 0,755 | |

| Kinetic model | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudo-first order | Pseudo-second order | Intra-particle diffusion | Elovich | |||||||||||||||||

| qm1 (mg/g) | k1(g/mg min) | R2 | qm2 (mg/g) | k2(g/mg min | R2 | ki(mg/gmin1/2) | C | R2 | α (mg/g min) | β (g/mg) | R2 | |||||||||

| 25°C | NR-HNO3 | 0,068 | 0,006 | 0,921 | 0,110 | 0,131 | 0,966 | 0,004 | 0,026 | 0,949 | 0,823 | 54,05 | 0,906 | |||||||

| NG-HNO3 | 0,083 | 0,005 | 0,889 | 0,135 | 0,133 | 0,977 | 0,005 | 0,021 | 0,851 | 0,670 | 38,02 | 0,966 | ||||||||

| CD-HNO3 | 0,064 | 0,007 | 0,979 | 0,133 | 0,261 | 0,995 | 0,004 | 0,049 | 0,974 | 0,952 | 48,02 | 0,987 | ||||||||

| HN-HNO3 | 0,086 | 0,007 | 0,936 | 0,126 | 0,118 | 0,989 | 0,004 | 0,192 | 0,966 | 0,723 | 45,66 | 0,867 | ||||||||

| NR-H2O2 | 0,059 | 0,012 | 0,978 | 0,069 | 0,158 | 0,982 | 0,003 | 0,002 | 0,963 | 0,614 | 69,44 | 0,942 | ||||||||

| NG-H2O2 | 0,052 | 0,021 | 0,890 | 0,120 | 0,116 | 0,977 | 0,005 | 0,011 | 0,963 | 0,633 | 42,55 | 0,918 | ||||||||

| CD-H2O2 | 0,047 | 0,007 | 0,888 | 0,077 | 0,211 | 0,983 | 0,003 | 0,010 | 0,881 | 0,667 | 62,11 | 0,938 | ||||||||

| HN-H2O2 | 0,058 | 0,007 | 0,996 | 0,087 | 0,198 | 0,991 | 0,003 | 0,014 | 0,993 | 0,933 | 62,89 | 0,944 | ||||||||

| 35°C | NR-HNO3 | 0,106 | 0,009 | 0,903 | 0,125 | 0,184 | 0,964 | 0,005 | 0,034 | 0,953 | 0,818 | 40,32 | 0,876 | |||||||

| NG-HNO3 | 0,095 | 0,013 | 0,990 | 0,151 | 0,137 | 0,996 | 0,005 | 0,031 | 0,919 | 0,742 | 38,17 | 0,969 | ||||||||

| CD-HNO3 | 0,066 | 0,009 | 0,936 | 0,151 | 0,312 | 0,996 | 0,004 | 0,069 | 0,944 | 0,761 | 48,08 | 0,993 | ||||||||

| HN-HNO3 | 0,087 | 0,006 | 0,902 | 0,157 | 0,155 | 0,985 | 0,005 | 0,039 | 0,960 | 0,793 | 35,84 | 0,974 | ||||||||

| NR-H2O2 | 0,051 | 0,009 | 0,977 | 0,091 | 0,321 | 0,995 | 0,004 | 0,003 | 0,964 | 0,890 | 64,52 | 0,982 | ||||||||

| NG-H2O2 | 0,058 | 0,009 | 0,873 | 0,127 | 0,295 | 0,999 | 0,004 | 0,056 | 0,806 | 0,891 | 50,25 | 0,937 | ||||||||

| CD-H2O2 | 0,077 | 0,011 | 0,981 | 0,132 | 0,246 | 0,999 | 0,005 | 0,040 | 0,884 | 0,826 | 40,65 | 0,981 | ||||||||

| HN-H2O2 | 0,076 | 0,016 | 0,998 | 0,111 | 0,227 | 0,999 | 0,004 | 0,038 | 0,896 | 0,914 | 51,54 | 0,977 | ||||||||

| 45°C | NR-HNO3 | 0,054 | 0,006 | 0,933 | 0,149 | 0,337 | 0,993 | 0,004 | 0,057 | 0,915 | 0,752 | 59,52 | 0,945 | |||||||

| NG-HNO3 | 0,129 | 0,016 | 0,975 | 0,188 | 0,172 | 0,997 | 0,006 | 0,036 | 0,935 | 0,748 | 34,60 | 0,981 | ||||||||

| CD-HNO3 | 0,074 | 0,010 | 0,988 | 0,158 | 0,355 | 0,998 | 0,004 | 0,081 | 0,932 | 0,634 | 50,51 | 0,981 | ||||||||

| HN-HNO3 | 0,085 | 0,006 | 0,911 | 0,165 | 0,173 | 0,986 | 0,005 | 0,051 | 0,953 | 0,908 | 36,63 | 0,969 | ||||||||

| NR-H2O2 | 0,112 | 0,008 | 0,989 | 0,160 | 0,399 | 0,992 | 0,007 | 0,002 | 0,979 | 0,164 | 30,84 | 0,989 | ||||||||

| NG-H2O2 | 0,078 | 0,010 | 0,981 | 0,155 | 0,413 | 0,998 | 0,005 | 0,068 | 0,939 | 0,808 | 45,05 | 0,992 | ||||||||

| CD-H2O2 | 0,095 | 0,013 | 0,965 | 0,159 | 0,299 | 0,999 | 0,006 | 0,049 | 0,835 | 0,817 | 33,56 | 0,949 | ||||||||

| HN-H2O2 | 0,086 | 0,014 | 0,821 | 0,161 | 0,342 | 0,998 | 0,006 | 0,051 | 0,814 | 0,810 | 32,36 | 0,936 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).