Submitted:

26 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characteristics of Cells Used in Research

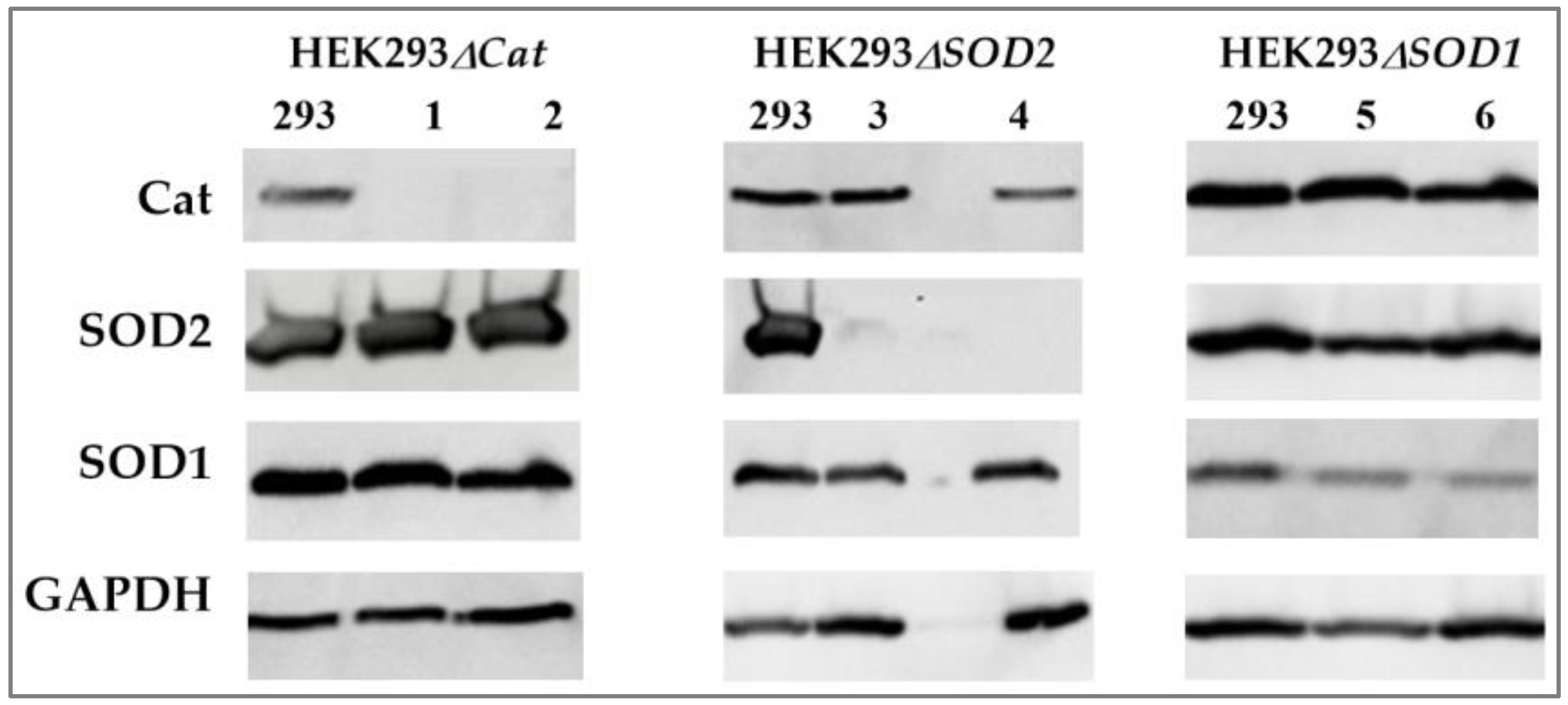

2.1.1. Application of the CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing System for Genome Modification of Human HEK293 Cells

2.2. Optimization of Yeast Cell Culture Conditions under Oxidative Stress

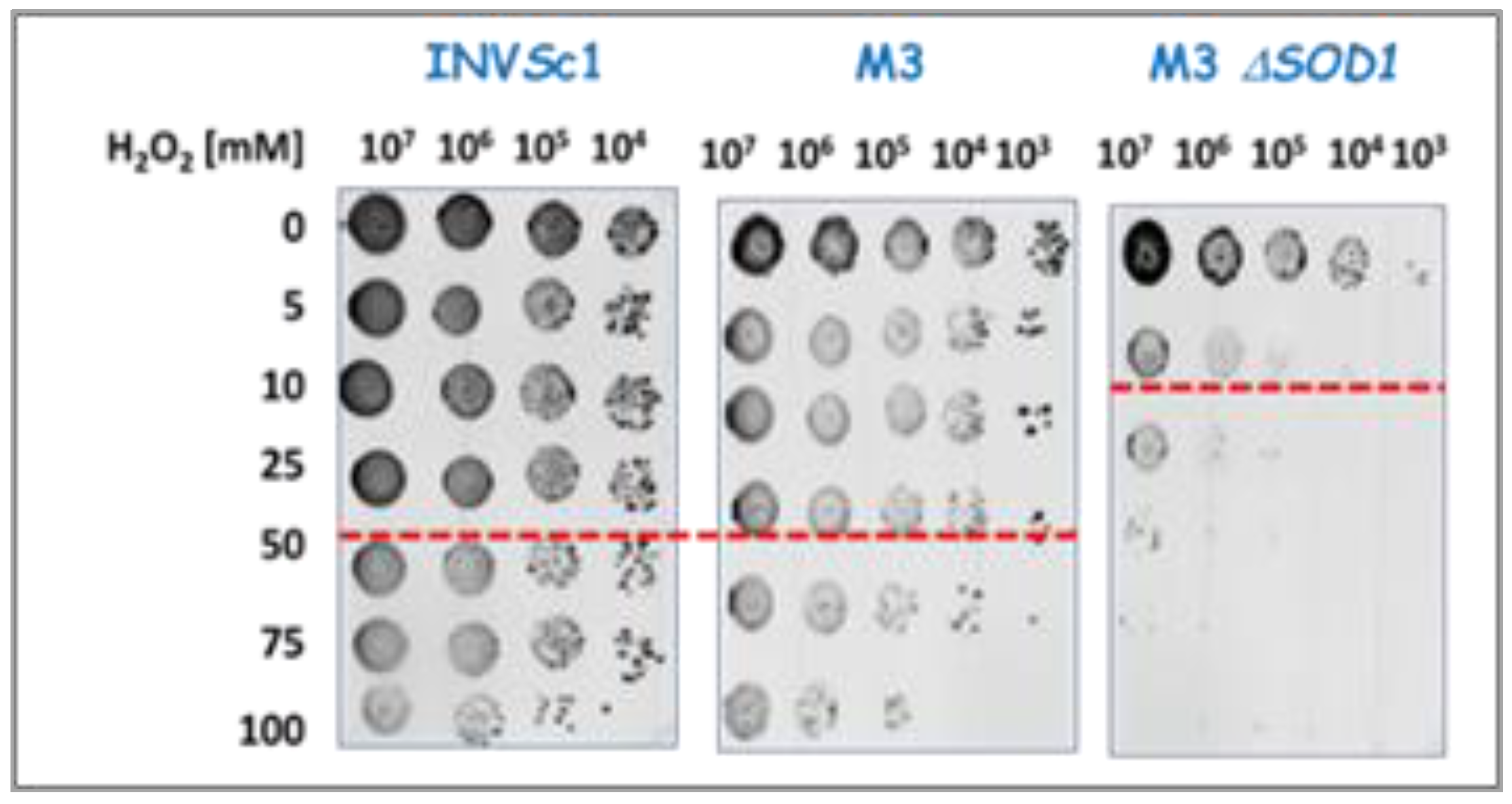

2.2.1. Evaluation of Yeast Viability in the Presence of Oxidative Stress-Inducing Reagents

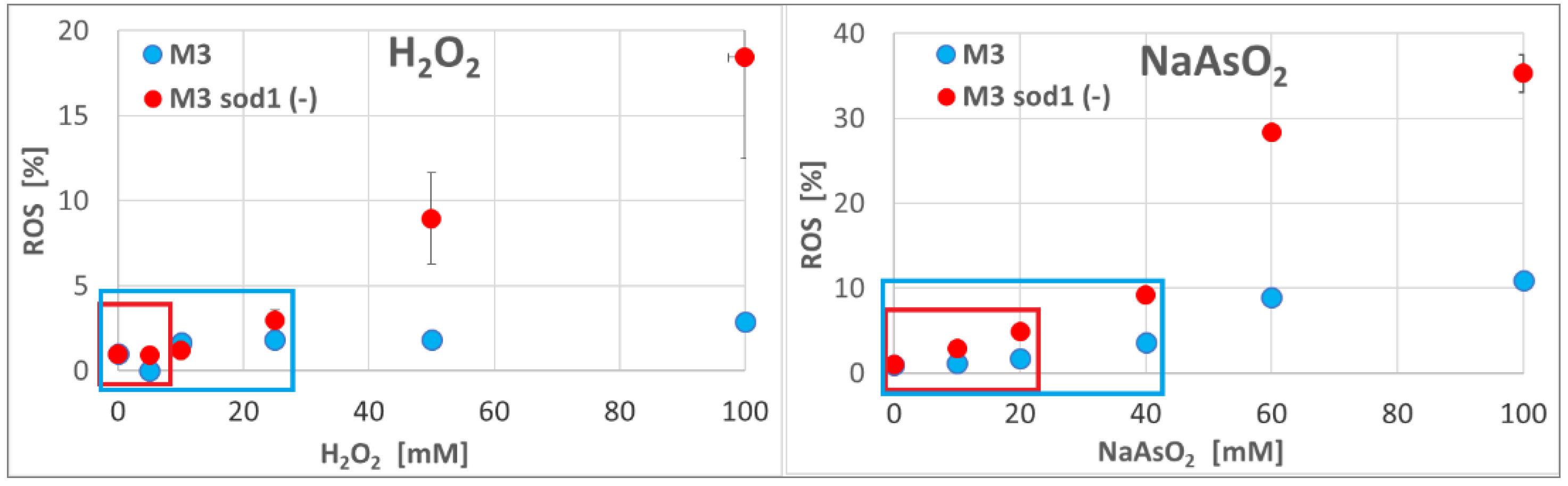

2.2.2. Determination of the ROS Level in Yeast Cells after Incubation with H2O2, NaAsO2 or NaClO

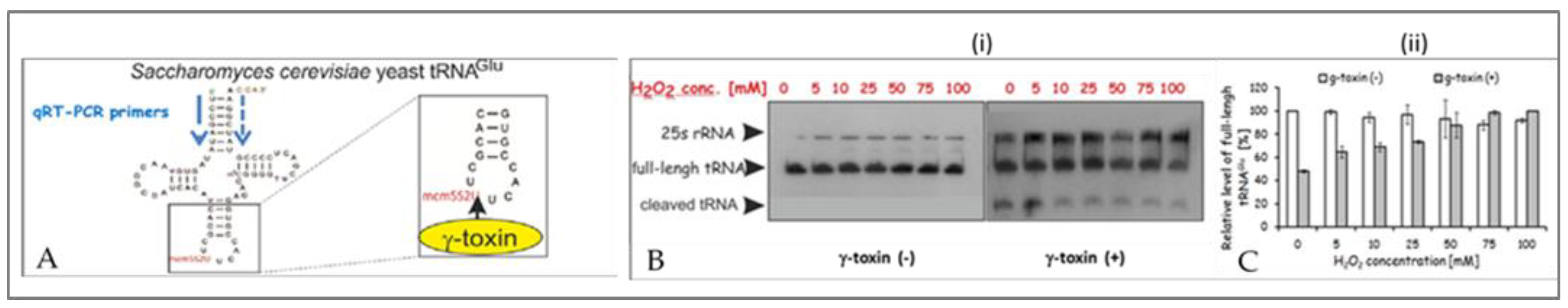

2.2.3. Monitoring the Reduction in the Amount of mcm5S2U-tRNA in Yeast Treated with H2O2, the γ-Toxin Assay

2.3. Optimization of Culture Conditions for Human Cancer Cells under Oxidative Stress

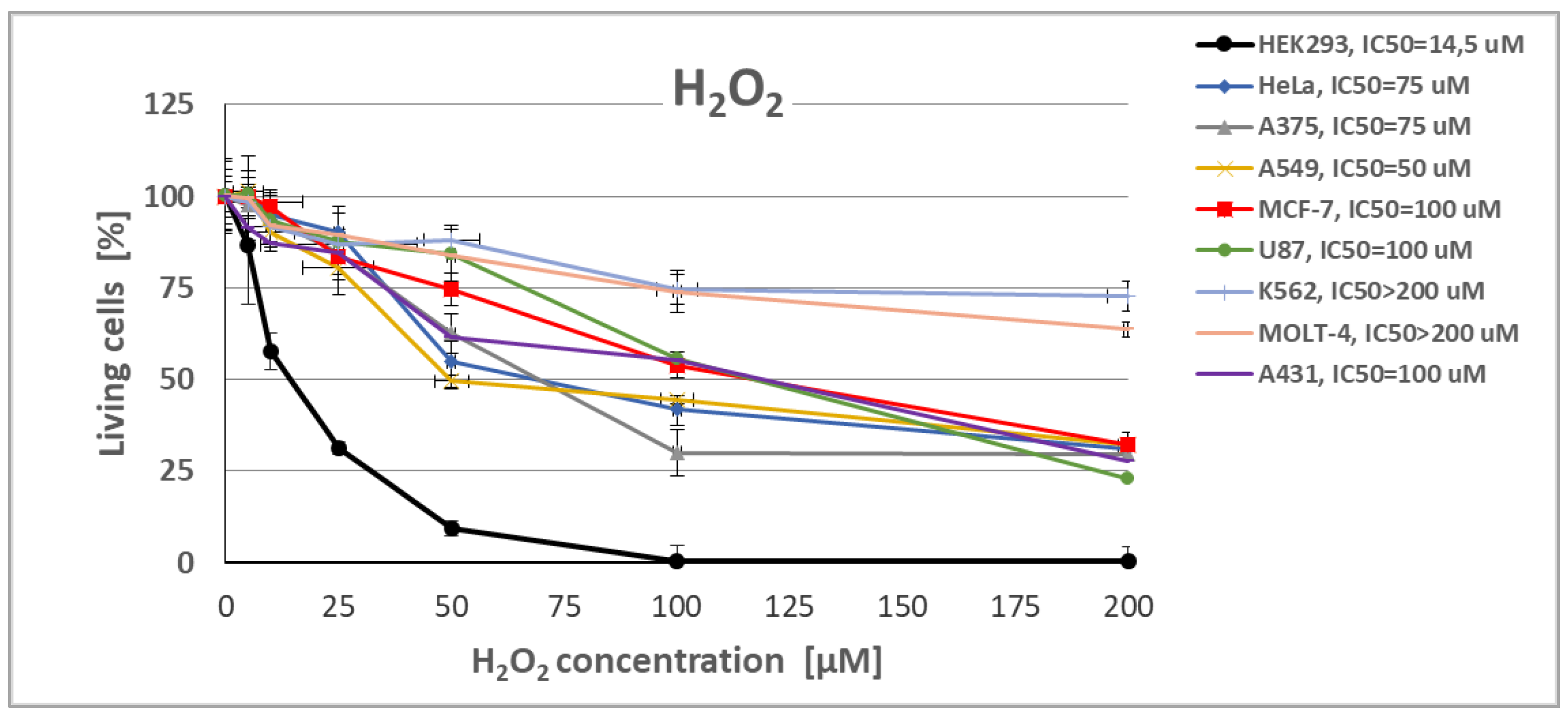

2.3.1. Evaluation of Human Cells Viability and Intracellular ROS Level

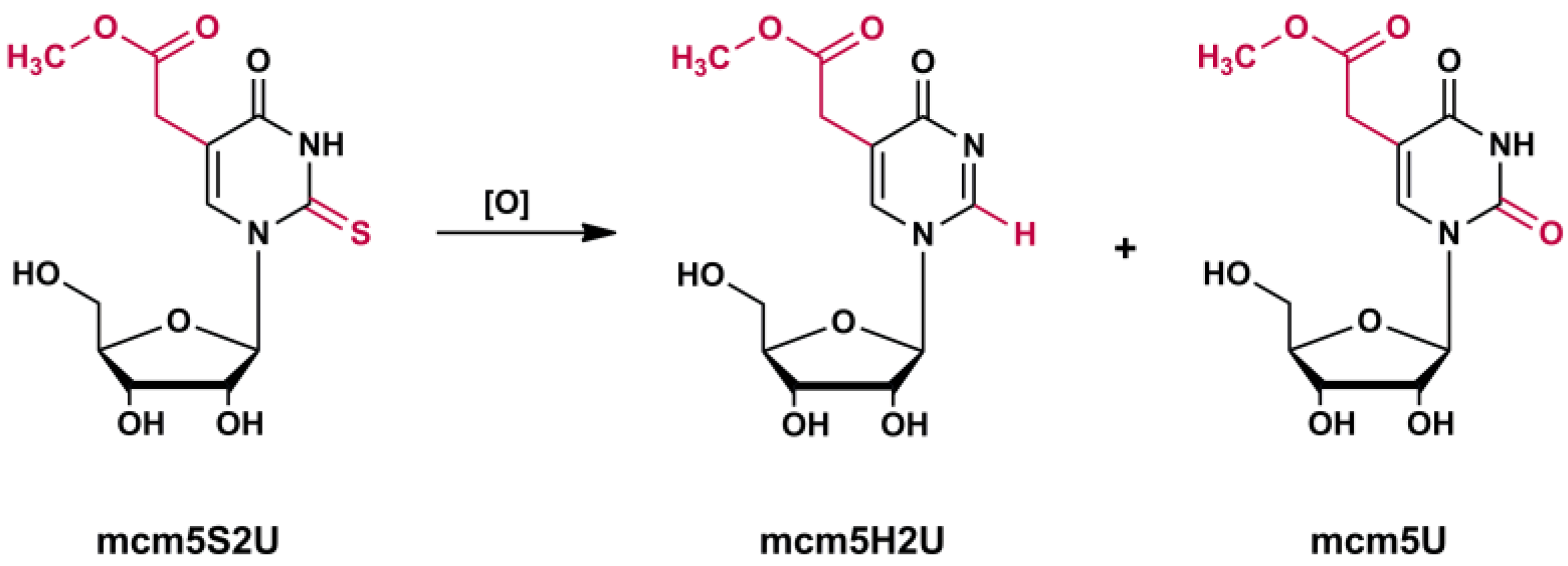

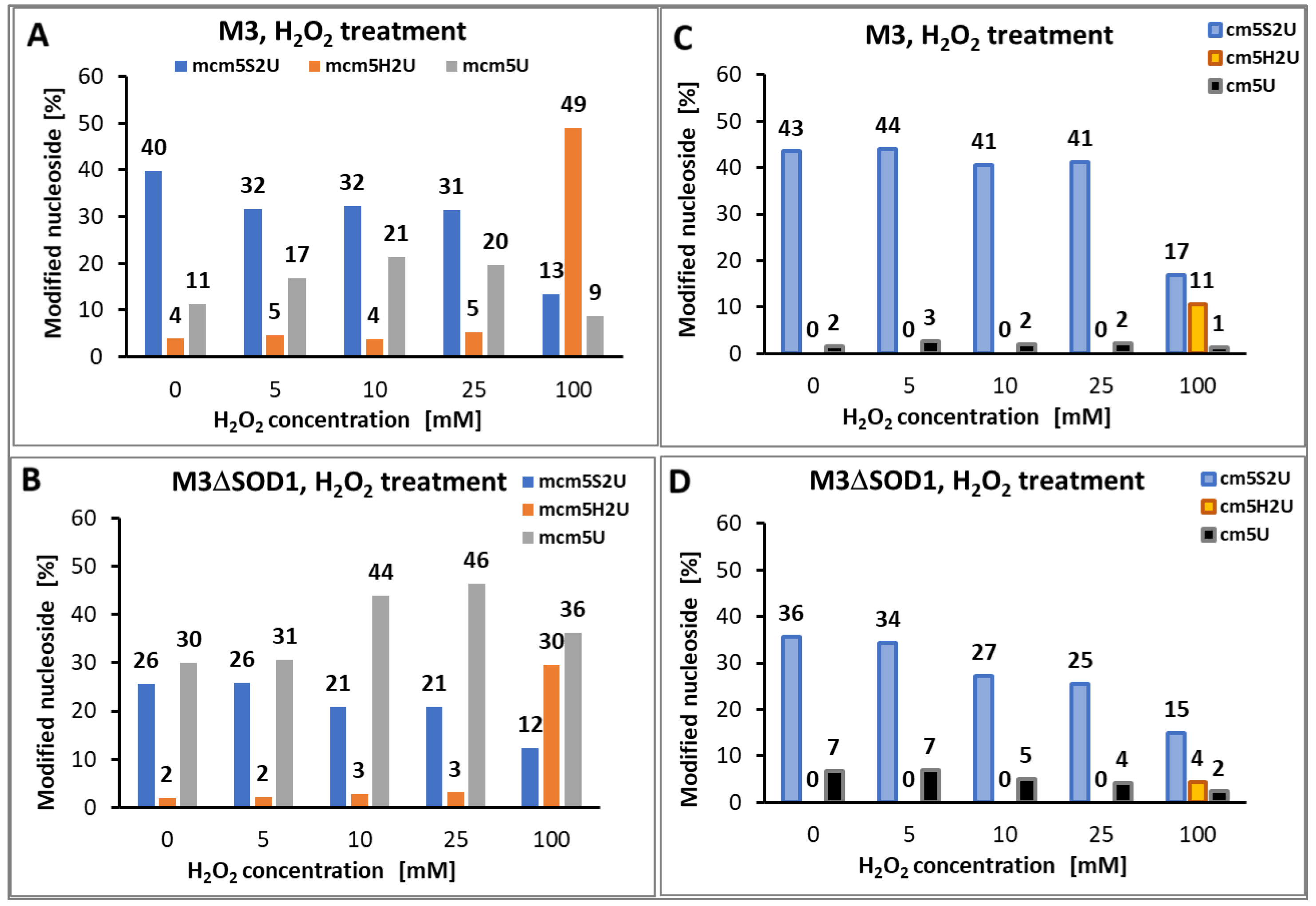

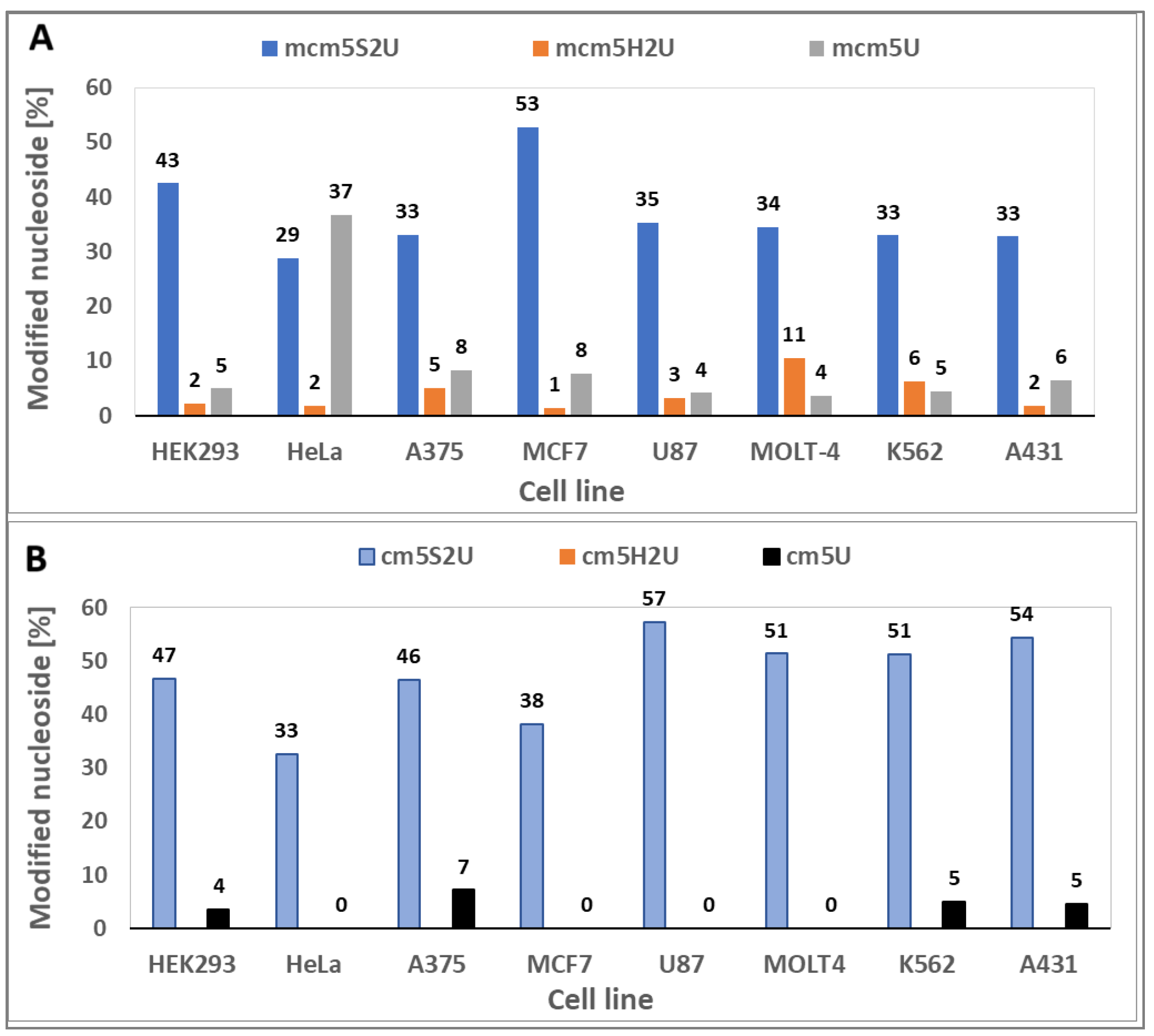

2.4. Identification of R5S2U Desulfuration Products by LC-MS/MS (MRMhr) Analysis

2.4.1. R5S2U Desulfuration in Yeast tRNAGlu

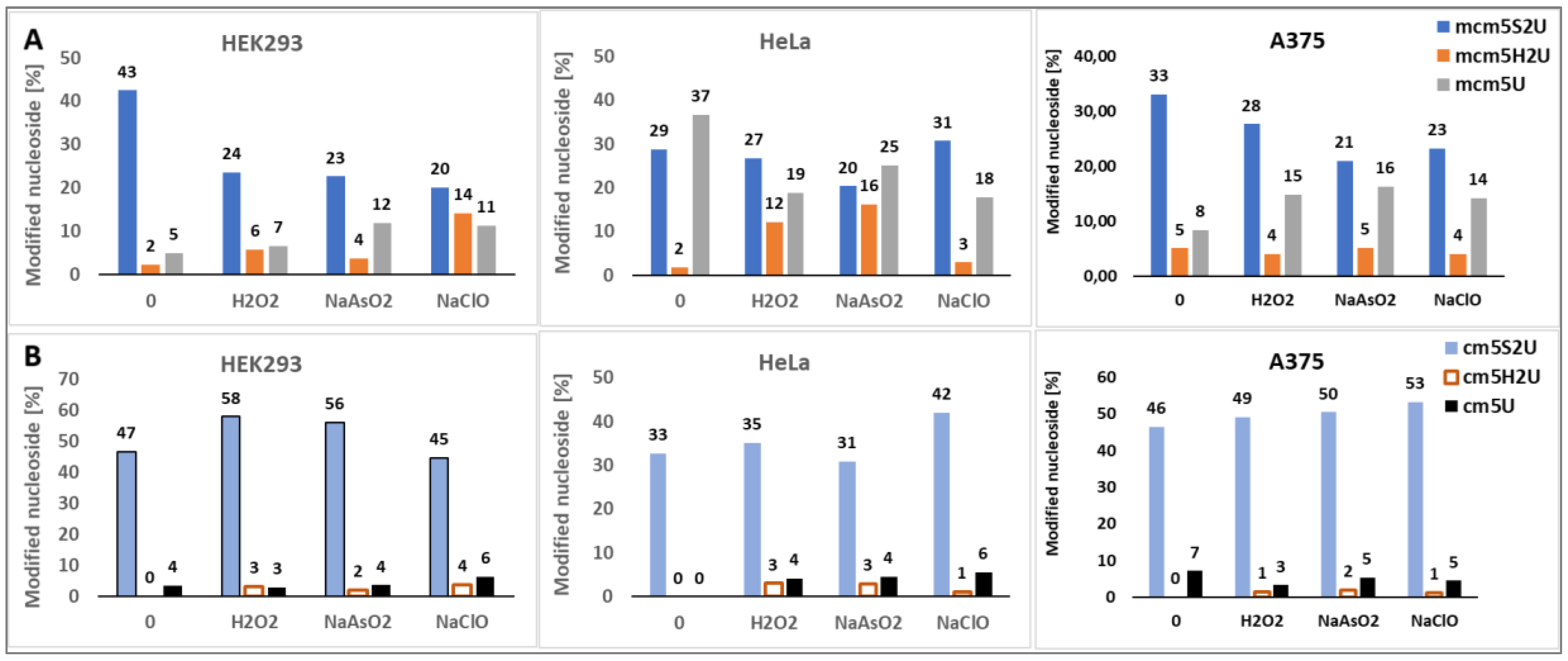

2.4.2. Search for mcm5S2U Desulfuration Products in the tRNA Fraction of Cancer Cells

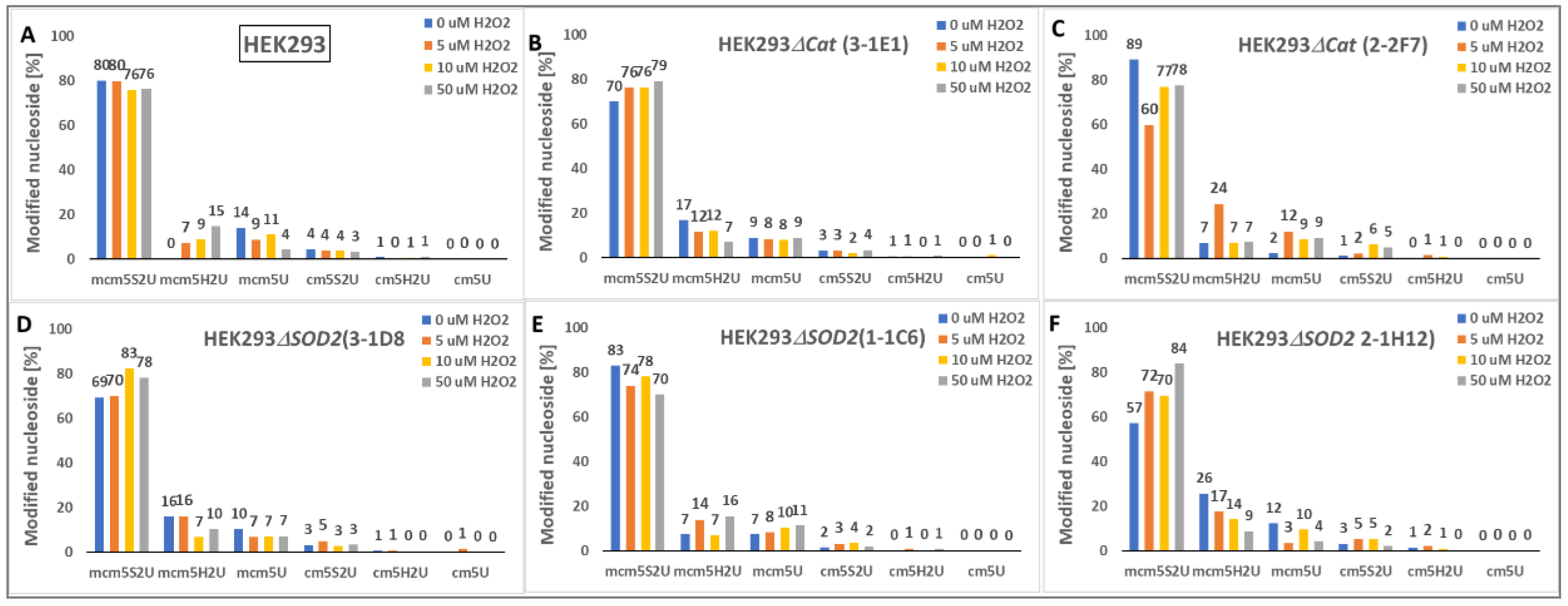

2.4.3. Analysis of HEK293ΔSOD2 and HEK293ΔCat tRNA Fraction Content

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Synthesis of a R5-Substituted-2-Thiouridines and Derivatives

3.2. Protocols for Yeast

3.2.1. Yeast Cell Culture

3.2.2. Yeast Viability Assay

3.2.3. Yeast Intracellular ROS Level

3.2.4. γ-Toxin Preparation

3.2.5. γ-toxin tRNA digestion

3.2.6. Northern Blot (NB) Analysis

3.2.7. qRT-PCR Analysis

3.2.8. Yeast Total RNA Preparation and Pull-Down of tRNAGlu

3.3. Protocols for Human Cells

3.3.1. Human Cells Culture

3.3.2. Cytotoxicity Assay

3.3.3. Intracellular ROS Level Determination

3.3.4. Isolation of Total Cellular RNA and the Total Cellular tRNA Fraction

3.4. CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing Experiments

3.4.1. Transfection

3.4.2. Western Blot

3.4.3. T7 Endonuclease I Based Mutation Detection

3.5. Analysis of tRNA Derived Nucleosides by LC-MS/MS

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, G.; Qin, Y.; Clark, W.C.; Dai, Q.; Yi, C.; He, C.; Lambow;itz, A.M.; Pan, T. Efficient and quantitative high-throughput tRNA sequencing. Nat Methods. 2015, 12, 835-837. [CrossRef]

- Yoluc, Y.; van de Logt, E.; Kellner-Kaiser, S. The Stress-Dependent Dynamics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA and rRNA Modification Profiles. Genes (Basel). 2021, 28, 1344. [CrossRef]

- Yoluç, Y.; Ammann, G.; Barraud, P.; Jora, M.; Limbach, PA. Motorin, Y.; Marchand, V.; Tisné, C.; Borland, K.; Kellner, S. Instrumental analysis of RNA modifications. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2021, 56, 178-204. [CrossRef]

- Sarin, L.P.; Kienast, S.D.; Leufken, J.; Ross, R.L; Dziergowska A.; Debiec, K.; Sochacka, E.; Limbach, P.A.; Fufezan, C.; Drexler, H.C.A.; Leidel, S.A. Nano LC-MS using capillary columns enables accurate quantification of modified ribonucleosides at low femtomol levels. RNA 2018, 24, 1403-1417. [CrossRef]

- Heiss, M.; Hagelskamp, F.; Marchand, V.; Motorin, Y.; Kellner, S. Cell culture NAIL-MS allows insight into human tRNA and rRNA modification dynamics in vivo. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 89. [CrossRef]

- Amalric, A.; Bastide, A.; Attina, A.; Choquet, A.; Vialaret, J.; Lehmann, S.; David, A.; Hirtz, C. Quantifying RNA modifications by mass spectrometry: a novel source of biomarkers in oncology. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2022, 59, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Boccaletto, P.; Manglebrg, C.G.; Sharma, P.; Lowe, T.M.; Leidel, S.A.; Bujnicki, J.M. Matching tRNA modifications in humans to their known and predicted enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 2143-2159. [CrossRef]

- Boccaletto, P.; Stefaniak, F.; Ray, A.; Cappannini, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Purta, E.; Kurkowska, M.; Shirvanizadeh, N.; Destefanis, E.; Groza, P.; Avşar, G.; Romitelli, A.; Pir, P.; Dassi, E.; Conticello, S.G.; Aguilo, F.; Bujnicki, J.M. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D231-D235. [CrossRef]

- Cantara, W.A.; Crain, P.F.; Rozenski, J.; McCloskey, J.A.; Harris, K.A.; Zhang, X.; Vendeix, F.A.; Fabris, D.; Agris, P.F. 2011, The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D195-201. [CrossRef]

- McCown, P.J.; Ruszkowska, A.; Kunkler, C.N., Breger, K.; Hulewicz, J.P.; Wang, M.C.; Springer, N.A.; Brown, J.A. Naturally occurring modified ribonucleosides. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2020, 11, e1595. [CrossRef]

- Machnicka, M.A.; Olchowik, A.; Grosjean, H.; Bujnicki, J.M. Distribution and frequencies of post-transcriptional modifications in tRNAs. RNA Biol. 2014, 11, 1619-1629. [CrossRef]

- Pan, T. Modifications and functional genomics of human transfer RNA. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, H.; de Crecy-Lagard, V.; Marck, C. Deciphering synonymous codons in the three domains of life: Co-evolution with specific tRNA modification enzymes. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 252–264.

- Agris, P.F.; Eruysal, E.R.; Narendran, A.; Väre, V.Y.P.; Vangaveti, S.; Ranganathan, S.V. Celebrating wobble decoding: Half a century and still much is new. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 537-553. [CrossRef]

- Agris, P.F.; Narendran, A.; Sarachan, K.; Väre, V.Y.P.; Eruysal, E. The Importance of Being Modified: The Role of RNA Modifications in Translational Fidelity. Enzymes, 2017, 41, 1-50. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, C.; Lünse, C.E.; Mörl, M. tRNA Modifications: Impact on Structure and Thermal Adaptation. Biomolecules, 2017, 7, 35. [CrossRef]

- Chanfreau, G.F. Impact of RNA Modifications and RNA-Modifying Enzymes on Eukaryotic Ribonucleases. Enzymes, 2017, 41, 299-329. [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, K.L.; Scharf, D.H.; Litomska, A.; Hertweck, C. Enzymatic Carbon-Sulfur Bond Formation in Natural Product Biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 2017, 117, 5521-5577. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y; Wu, Y.; Begley, T.J.; Sheng, J. Sulfur modification in natural RNA and therapeutic oligonucleotides. RSC Chem Biol. 2021, 2, 990-1003. [CrossRef]

- El Yacoubi, B.; Bailly, M.; de Crécy-Lagard, V. Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs. Annu Rev Genet. 2012, 46, 69-95. [CrossRef]

- Tomikawa, C.; Ohira, T.; Inoue, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Yamagishi, A.; Suzuki, T.; Hori, H. Distinct tRNA modifications in the thermo-acidophilic archaeon, Thermoplasma acidophilum. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 3575–3580.

- Björk, G.R.; Hagervall, T.G. Transfer RNA modification: Presence, synthesis, and function. EcoSal Plus 2014, 6.

- Durant, P.C.; Bajji, A.C.; Sundaram, M.; Kumar, R.K.; Davis, D.R. Structural effects of hypermodified nucleosides in the Escherichia coli and human tRNALys anticodon loop: the effect of nucleosides s2U, mcm5U, mcm5s2U, mnm5s2U, t6A, and ms2t6A. Biochemistry. 2005, 44, 8078-8089. [CrossRef]

- Nawrot, B.; Sierant, M.; Szczupak, P. Selenium modified bacterial tRNAs. In: Sugimoto, N. (eds) Handbook of Chemical Biology of Nucleic Acids. Springer, Singapore. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shigi, N. Biosynthesis and functions of sulfur modifications in tRNA. Front Genet. 2014, 5, 67. [CrossRef]

- Madore, E.; Florentz, C.; Giegé, R.; Sekine, S.; Yokoyama, S.; Lapointe, J. Effect of modified nucleotides on Escherichia coli tRNAGlu structure and on its aminoacylation by glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Predominant and distinct roles of the mnm5 and s2 modifications of U34. Eur J Biochem. 1999, 266, 1128-1135. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, A.; Spears, J.L.; Gaston, K.W.; Limbach, P.A.; Gamper, H.; Hou, Y.M.; Kaiser, R.; Agris, P.F.; Perona, J.J. Structural and mechanistic basis for enhanced translational efficiency by 2-thiouridine at the tRNA anticodon wobble position. J Mol Biol. 2013, 425, 3888-3906. [CrossRef]

- Urbonavicius, J.; Stahl, G.; Durand, J.M.; Ben Salem, S.N.; Qian, Q.; Farabaugh, P.J.; Björk, G.R. Transfer RNA modifications that alter +1 frameshifting in general fail to affect -1 frameshifting. RNA, 2003, 9, 760-768. [CrossRef]

- Brégeon, D.; Colot, V.; Radman, M.; Taddei, F. Translational misreading: a tRNA modification counteracts a +2 ribosomal frameshift. Genes Dev., 2001, 15, 2295-2306. [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, A.; Pistara, V. Conversion of the Thiocarbonyl Group into the Carbonyl Group. Tetrahedron 1998, 54:15027-15062.

- Sochacka, E.; Kraszewska, K.; Sochacki, M.; Sobczak, M.; Janicka, M.; Nawrot, B. The 2-thiouridine unit in the RNA strand is desulfured predominantly to 4-pyrimidinone nucleoside under in vitro oxidative stress conditions. Chem Commun (Camb). 2011, 47, 4914-4916. [CrossRef]

- Sochacka, E.; Bartos, P.; Kraszewska, K., Nawrot, B. Desulfuration of 2-thiouridine with hydrogen peroxide in the physiological pH range 6.6-7.6 is pH-dependent and results in two distinct products. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013, 23, 5803-5805. [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A., Wielgus, E.; Leszczynska, G.; Sobczak, M.; Mikolajczyk, B.; Sochacka, E.; Nawrot B. An efficient approach for conversion of 5-substituted 2-thiouridines built in RNA oligomers into corresponding desulfured 4-pyrimidinone products. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015, 25, 3100-3104. [CrossRef]

- Bartos, P.; Ebenryter-Olbinska, K.; Sochacka, E.; Nawrot, B. The influence of the C5 substituent on the 2-thiouridine desulfuration pathway and the conformational analysis of the resulting 4-pyrimidinone products. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015, 23, 5587-5594. [CrossRef]

- Sochacka, E.; Szczepanowski, R.H.; Cypryk, M.; Sobczak, M.; Janicka, M.; Kraszewska, K.; Bartos, P.; Chwialkowska; A.; Nawrot B. 2-Thiouracil deprived of thiocarbonyl function preferentially base pairs with guanine rather than adenine in RNA and DNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 2499-2512. [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Chan, C.T.; Gu, C.; Lim, K.S.; Chionh, Y.H.; McBee, M.E.; Russell, B.S.; Babu, I.R.; Begley, T.J.; Dedon, P.C. Quantitative analysis of ribonucleoside modifications in tRNA by HPLC-coupled mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2014 9, 828-841. [CrossRef]

- Blachly-Dyson, E.; Peng, S.; Colombini, M.; Forte, M. Selectivity changes in site-directed mutants of the VDAC ion channel: structural implications. Science 1990, 247, 1233-1236. [CrossRef]

- Blachly-Dyson, E.; Peng, S.Z.; Colombini, M.; Forte, M. Probing the structure of the mitochondrial channel, VDAC, by site-directed mutagenesis: a progress report. J Bioenerg Biomembr 1989, 21, 471-483. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, D.; Zhao, Y. Manganese superoxide dismutase in cancer prevention. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1628-1645. [CrossRef]

- Scibior-Bentkowska, D.; Czeczot, H. Cancer cells and oxidative stress. Postepy Hig Med Dosw, 2009; 63, 58-72. e-ISSN 1732-2693.

- Lentini, J.M.; Ramos, J.; Fu, D. Monitoring the 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine (mcm5s2U) modification in eukaryotic tRNAs via the γ-toxin endonuclease. RNA. 2018 24, 749-758. [CrossRef]

- Vorbruggen, .H.; Strehlke, P. Nucleosidsynthesen, VII. Eine einfache Synthese von 2-Thiopyrimidin-nucleosiden. Chem.Ber. 1973, 106, 3039-3061. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, W,; Ren, J.; Pan, T.; He, C. The AlkB domain of mammalian ABH8 catalyzes hydroxylation of 5-methoxycarbonylmethyluridine at the wobble position of tRNA. Angew Chem I,nt Ed Engl. 2010, 49, 8885-8888. [CrossRef]

- Kwolek-Mirek M, Zadrag-Tecza R. Comparison of methods used for assessing the via-bility and vitality of yeast cells. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014 Nov;14(7):1068-79. [CrossRef]

- Szczupak, P.; Sierant, M.; Wielgus, E.; Radzikowska-Cieciura, E.; Kulik, K.; Krakowiak, A.; Kuwerska, P.; Leszczynska, G.; Nawrot, B. Escherichia coli tRNA 2-Selenouridine Synthase (SelU): Elucidation of Substrate Specificity to Understand the Role of S-Geranyl-tRNA in the Conversion of 2-Thio- into 2-Selenouridines in Bacterial tRNA. Cells 2022, 11, 1522. [CrossRef]

- Boveris, A. Determination of the production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide in mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 429-435. [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E., Davies, K.J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000, 29, 222-230. [CrossRef]

- Nohl, H. Generation of superoxide radicals as byproduct of cellular respiration. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 1994, 52, 199-204.

| Yeast strain | H2O2 [mM] |

NaAsO2 [mM] |

NaClO [mM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| INVSc1 | 50 | 100 | 10 |

| M3 | 25 | 40 | 7 |

| M3Δsod1 | 5 | 20 | 7 |

| Cell lines | H2O2 IC50 [µM] |

NaAsO2 IC50 [µM] |

NaClO IC50 [µM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293 | 14,5 | 200 | 100 |

| HEK293ΔSOD2 | 10 | nd | nd |

| HEK293ΔCat | 10 | nd | nd |

| HeLa | 50 | >200 | >100 |

| A375 | 70 | >200 | >100 |

| A549 | 50 | >200 | >200 |

| MCF-7 | 100 | 200 | 100 |

| U-87 MG | 100 | 200 | 100 |

| K562 | >200 | >200 | >100 |

| MOLT-4 | >200 | >200 | >100 |

| A431 | 100 | 200 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).