Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

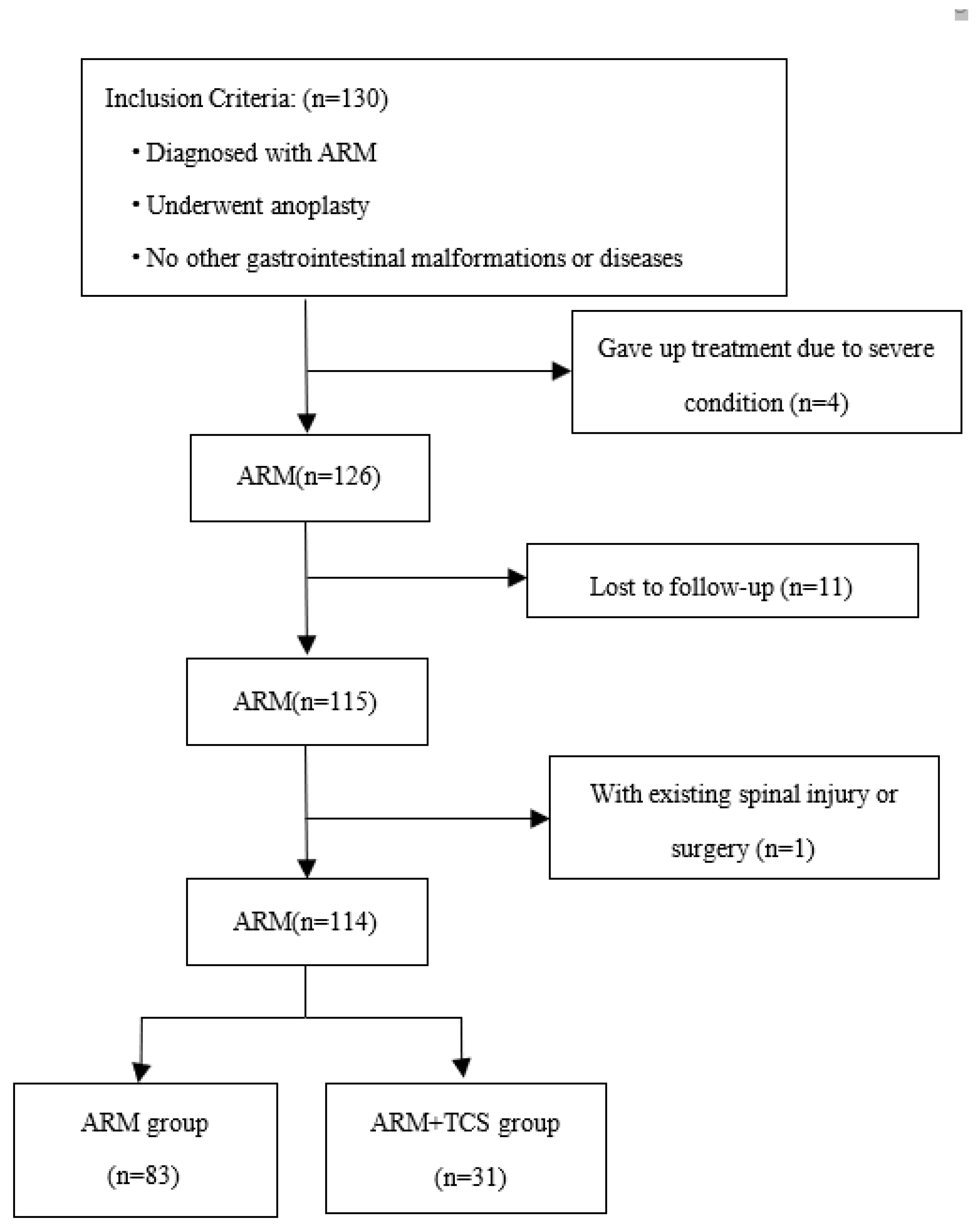

2.1 Patients

2.2 Data Collection

2.2.1 Research Design

2.2.2 Statistical analysis

2.2.3 Results

3. Results

3.1. Risk factors for ARMs associated with TCS

| Variables | ARM group(n=83) | ARM+TCS group(n=31) | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 32(38.55) | 12(38.71) | 0.332 | (0.072-1.540) | 0.159 |

| Male | 51(61.45) | 19(61.29) | |||

| Maternal age at childbirth (years) | |||||

| <35 | 62(74.70) | 26(83.87) | 1.949 | (0.155-7.334) | 0.545 |

| >=35 | 21(25.30) | 5(16.13) | |||

| Paternal age at childbirth (years) | |||||

| <35 | 51(61.45) | 24(77.42) | 1.065 | (0.155-7.334) | 0.949 |

| >=35 | 32(38.55) | 7(22.58) | |||

| Education level of mother | |||||

| Elementary school | 6(7.23) | 3(9.68) | Ref | Ref | 0.722 |

| Junior high school | 24(28.92) | 9(29.03) | 0.402 | (0.059-2.741) | 0.352 |

| High school | 21(25.30) | 5(16.13) | 0.616 | (0.074-5.117) | 0.654 |

| University or Above | 32(38.55) | 14(45.16) | 0.818 | (0.117-5.725) | 0.839 |

| Active smoking or passive smoking | |||||

| Yes | 22(26.51) | 11(35.48) | 2.431 | (0.737-8.021) | 0.145 |

| No | 61(73.49) | 20(64.52) | |||

| Taking folic acid on time | |||||

| Yes | 34(40.96) | 6(19.35) | 2.640 | (0.679-10.268) | 0.161 |

| No | 49(59.04) | 25(80.65) | |||

| Abnormal pregnancy history | |||||

| Yes | 23(27.71) | 6(19.35) | 0.627 | (0.181-2.175) | 0.462 |

| No | 60(72.29) | 25(80.65) | |||

| Mode of conception | |||||

| Natural | 77(92.77) | 28(90.32) | 0.380 | (0.047-5.117) | 0.365 |

| Assisted | 6(7.23) | 3(9.68) | |||

| Multiple pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 2(2.41) | 1(3.23) | 1.317 | (0.051-34.285) | 0.869 |

| No | 81(97.59) | 30(96.77) | |||

| Infection in early pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 17(20.48) | 12(38.71) | 0.379 | (0.102-1.412) | 0.148 |

| No | 66(79.52) | 19(61.29) | |||

| Maternal diseases | |||||

| Yes | 15(18.07) | 4(12.90) | 0.954 | (0.174-5.226) | 0.957 |

| No | 68(81.93) | 27(87.10) | |||

| Gestational age(weeks) | |||||

| <37 | 17(20.48) | 4(12.90) | 0.378 | (0.076-1.875) | 0.234 |

| >=37 | 66(79.52) | 27(87.10) | |||

| Labor |

|||||

| Vaginal birth |

50(60.24) | 19(61.29) | 0.726 | (0.213-2.476) | 0.609 |

| Cesarean section |

33(39.76) | 12(38.71) | |||

| Wingspread classification | |||||

| Low | 66(79.52) | 14(45.16) | 0.117 | (0.029-0.468) | 0.002 |

| Intermediate or high | 17(20.48) | 17(54.84) | |||

| Krickenberger classification | |||||

| Rectourethral fistula | 13(15.66) | 7(22.58) | Ref | Ref | 0.966 |

| Rectovesical fistula | 3(3.61) | 3(9.68) | 0.998 | ||

| Rectovaginal fistula | 2(2.41) | 1(3.23) | 0.998 | ||

| Anal stenosis | 9(10.84) | 3(9.68) | 0.998 | ||

| Perineal fistula | 30(36.14) | 7(22.58) | 0.999 | ||

| Rectourethrovaginal fistula | 25(30.12) | 8(25.81) | 0.999 | ||

| Rectal atresia | 1(1.20) | 2(6.45) | 0.999 | ||

| Presence of other malformations | |||||

| No | 36(43.37) | 3(9.68) | Ref | Ref | 0.014 |

| One type | 32(38.55) | 15(48.39) | 6.528 | (1.571-27.130) | 0.010 |

| Two types or more | 15(18.07) | 13(41.94) | 7.701 | (1.686-35.171) | 0.008 |

| Variables | B | SE | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Wingspread classification | 1.273 | 0.495 | 3.571 | (0.106-0.738) | 0.010 |

| Presence of other malformations | |||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | 0.026 |

| One type | 1.335 | 0.615 | 3.801 | (1.139-12.688) | 0.030 |

| Two types or more | 1.743 | 0.669 | 5.716 | (1.541-21.210) | 0.009 |

3.2 Anorectal function with an ARM combined with TCS after untethering surgery

| Variables | ARM group(n=65) | ARM+TCS group (n=14) |

χ2/Z | p |

| Soiling | ||||

| No | 35(53.85) | 9(64.28) | -0.589 | 0.556 |

| Grade 1 once or twice per week | 12(18.46) | 2(14.29) | ||

| Grade 2 Every day, no social problem | 10(15.38) | 1(7.14) | ||

| Grade 3 Constant, social problem | 8(12.31) | 2(14.29) | ||

| Constipation | ||||

| No | 21(32.31) | 9(64.28) | -2.020 | 0.043 |

| Grade 1 Manageable by changes in diet | 19(29.23) | 2(14.29) | ||

| Grade 2 Requires laxatives | 11(16.92) | 2(14.29) | ||

| Grade 3 Resistant to diet and laxatives | 14(21.54) | 1(7.14) | ||

| Voluntary bowel movements | ||||

| No | 22(33.85) | 3(21.43) | 0.821 | 0.365 |

| Feeling of urge、 Capacity to verbalize、Hold defecation | 43(66.15) | 11(78.57) |

| Variables | ARM group(n=18) | ARM+TCS group (n=17) |

χ2/Z | p |

| Soiling | ||||

| No | 8(44.44) | 6(35.29) | -0.434 | 0.665 |

| Grade 1 once or twice per week | 5(27.78) | 5(29.41) | ||

| Grade 2 Every day, no social problem | 2(11.11) | 4(23.53) | ||

| Grade 3 Constant, social problem | 3(16.67) | 2(11.77) | ||

| Constipation | ||||

| No | 5(27.78) | 7(41.18) | -0.326 | 0.744 |

| Grade 1 Manageable by changes in diet | 7(38.88) | 3(17.65) | ||

| Grade 2 Requires laxatives | 3(16.67) | 5(29.41) | ||

| Grade 3 Resistant to diet and laxatives | 3(16.67) | 2(11.76) | ||

| Voluntary bowel movements | ||||

| No | 12(66.67) | 7(41.18) | 2.289 | 0.130 |

| Feeling of urge、 Capacity to verbalize、Hold defecation | 6(33.33) | 10(58.82) |

4. Discussion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MIYAKE Y, LANE G J, YAMATAKA A. Embryology and anatomy of anorectal malformations [J]. Semin Pediatr Surg, 2022, 31(6): 151226.

- LENA F, PELLEGRINO C, ZACCARA A M, et al. Anorectal malformation, urethral duplication, occult spinal dysraphism (ARM-UD-OSD): a challenging uncommon association [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2022, 38(10): 1487-94.

- LIAQAT N, WOOD R, FUCHS M. Hypospadias and anorectal malformation: A difficult combination [J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2023, 58(2): 228-30.

- DE BEAUFORT C M C, VAN DEN AKKER A C M, KUIJPER C F, et al. The Importance of Screening for Additional Anomalies in Patients with Anorectal Malformations: A Retrospective Cohort Study [J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2023, 58(9): 1699-707.

- ESPOSITO G, TOTONELLI G, MORINI F, et al. Predictive value of spinal bone anomalies for spinal cord abnormalities in patients with anorectal malformations [J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2021, 56(10): 1803-10.

- FANJUL M, SAMUK I, BAGOLAN P, et al. Tethered cord in patients affected by anorectal malformations: a survey from the ARM-Net Consortium [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2017, 33(8): 849-54.

- WEISBROD L J, THORELL W. Tethered Cord Syndrome (TCS) [M]. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: William Thorell declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. 2024.

- CATMULL S, ASHURST J. Tethered Cord Syndrome [J]. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med, 2019, 3(3): 297-8.

- TSUDA T, IWAI N, KIMURA O, et al. Bowel function after surgery for anorectal malformations in patients with tethered spinal cord [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2007, 23(12): 1171-4.

- DE BEAUFORT C M C, GROENVELD J C, MACKAY T M, et al. Spinal cord anomalies in children with anorectal malformations: a retrospective cohort study [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2023, 39(1): 153.

- INOUE M, UCHIDA K, OTAKE K, et al. Long-term functional outcome after untethering surgery for a tethered spinal cord in patients with anorectal malformations [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2017, 33(9): 995-9.

- LI J, GAO W, LIU X, et al. Clinical characteristics, prognosis, and its risk factors of anorectal malformations: a retrospective study of 332 cases in Anhui Province of China [J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2020, 33(4): 547-52.

- FARIA D J, SIMOES MDE J, TEIXEIRA L C, et al. Effect of folic acid in a modified experimental model of anorectal malformations adriamycin-induced in rats [J]. Acta Cir Bras, 2016, 31(1): 22-7.

- WU F, WANG Z, BI Y, et al. Investigation of the risk factors of anorectal malformations [J]. Birth Defects Res, 2022, 114(3-4): 136-44.

- DEWBERRY L, PENA A, MIRSKY D, et al. Sacral agenesis and fecal incontinence: how to increase the index of suspicion [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2019, 35(2): 239-42.

- RINTALA R J. Congenital anorectal malformations: anything new? [J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2009, 48 Suppl 2: S79-82.

- UCHIDA K, INOUE M, MATSUBARA T, et al. Evaluation and treatment for spinal cord tethering in patients with anorectal malformations [J]. Eur J Pediatr Surg, 2007, 17(6): 408-11.

- BISCHOFF A, PENA A, KETZER J, et al. The conus medullaris ratio: A new way to identify tethered cord on MRI [J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2019, 54(2): 280-4.

- METZGER G, COOPER J N, KABRE R S, et al. Inter-rater Reliability of Sacral Ratio Measurements in Patients with Anorectal Malformations [J]. J Surg Res, 2020, 256: 272-81.

- JEHANGIR S, ADAMS S, ONG T, et al. Spinal cord anomalies in children with anorectal malformations: Ultrasound is a good screening test [J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2020, 55(7): 1286-91.

- TOMINEY S, KALIAPERUMAL C, GALLO P. External validation of a new classification of spinal lipomas based on embryonic stage [J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2020, 25(4): 394-401.

- MOROTA N, IHARA S, OGIWARA H. New classification of spinal lipomas based on embryonic stage [J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2017, 19(4): 428-39.

- HERTZLER D A, 2ND, DEPOWELL J J, STEVENSON C B, et al. Tethered cord syndrome: a review of the literature from embryology to adult presentation [J]. Neurosurg Focus, 2010, 29(1): E1.

- SCHMITT F, SCALABRE A, MURE P Y, et al. Long-Term Functional Outcomes of an Anorectal Malformation French National Cohort [J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2022, 74(6): 782-7.

- TOTONELLI G, MESSINA R, MORINI F, et al. Impact of the associated anorectal malformation on the outcome of spinal dysraphism after untethering surgery [J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2019, 35(2): 227-31.

- VILANOVA-SANCHEZ A, RECK C A, SEBASTIAO Y V, et al. Can sacral development as a marker for caudal regression help identify associated urologic anomalies in patients with anorectal malformation? [J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2018, 53(11): 2178-82.

- YANG Z, LI X, JIA H, et al. BMP7 is Downregulated in Lumbosacral Spinal Cord of Rat Embryos With Anorectal Malformation [J]. J Surg Res, 2020, 251: 202-10.

- HAN X, YUE X, WANG G, et al. Successfully treatment of tethered-cord syndrome secondary to progressive-development giant myelomeningocele by surgical repair with intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in an infant [J]. Asian J Surg, 2023, 46(4): 1830-1.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).