Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Archaeological Context

3. Materials and Methods

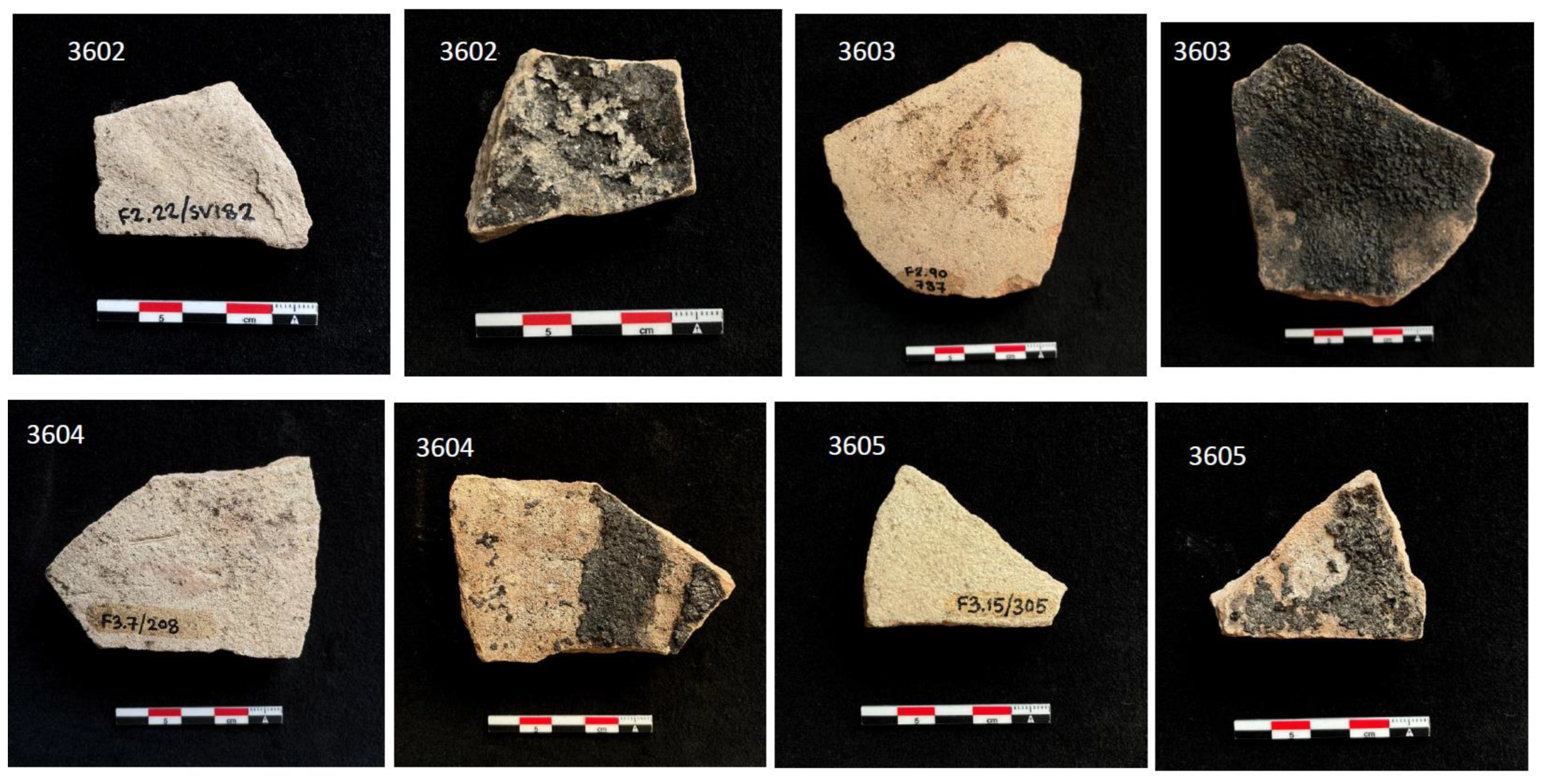

3.1. Samples

3. Analytical Procedures

3.2.1. Bitumen Analysis

3.2.2. Wine Detection

4. Results

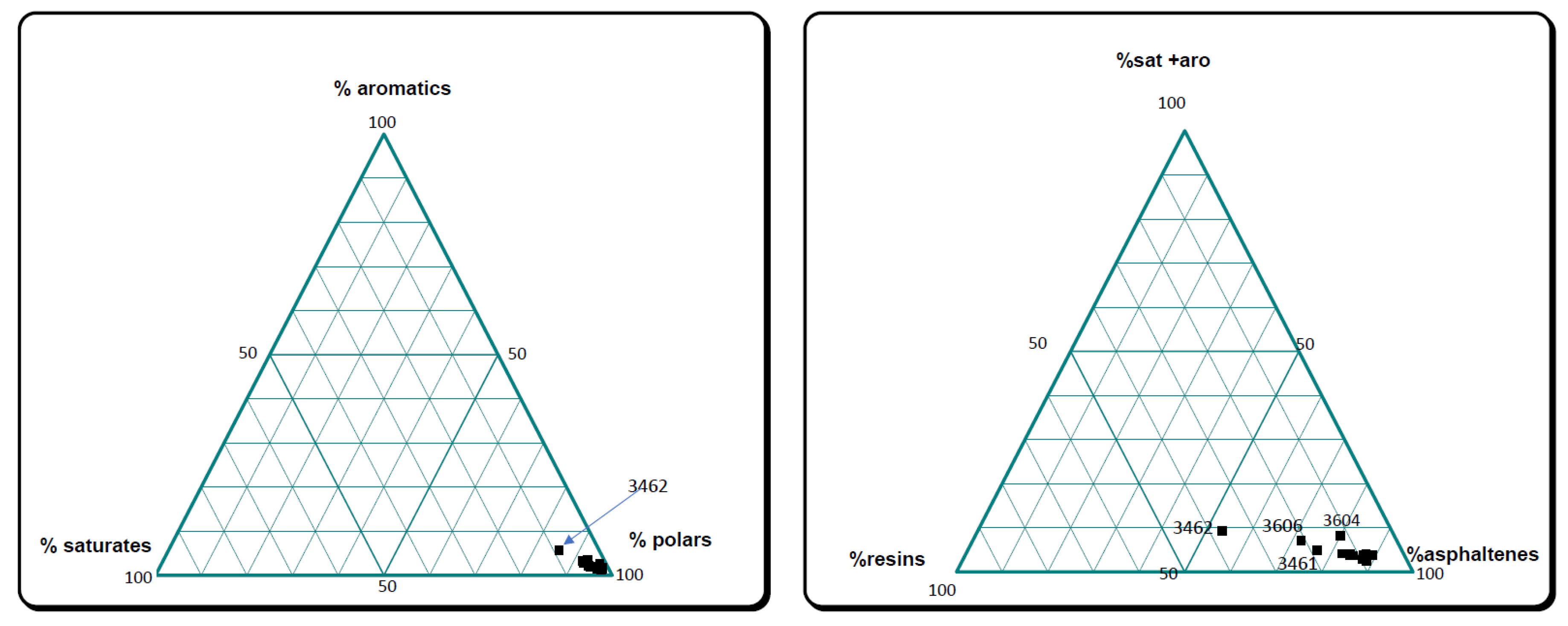

4.1. Gross Composition

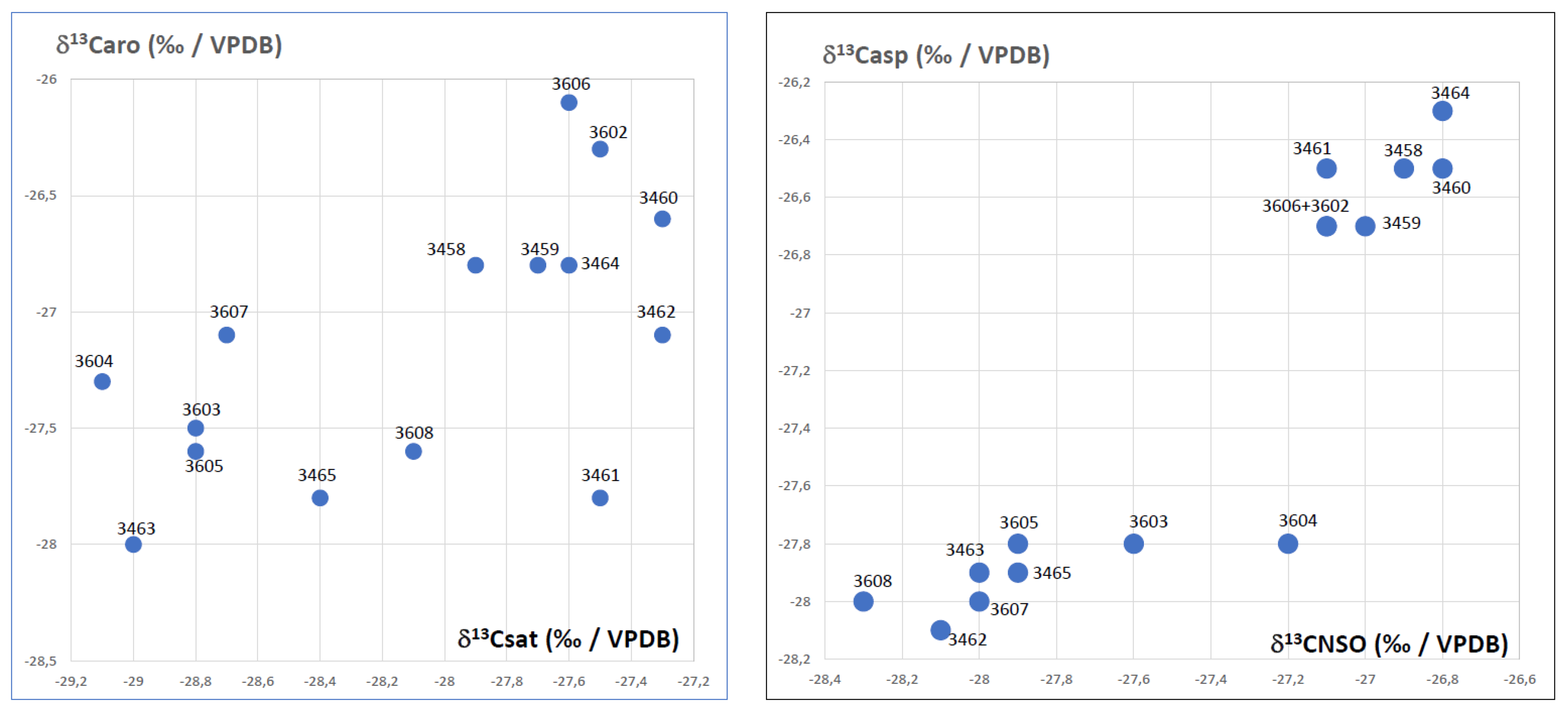

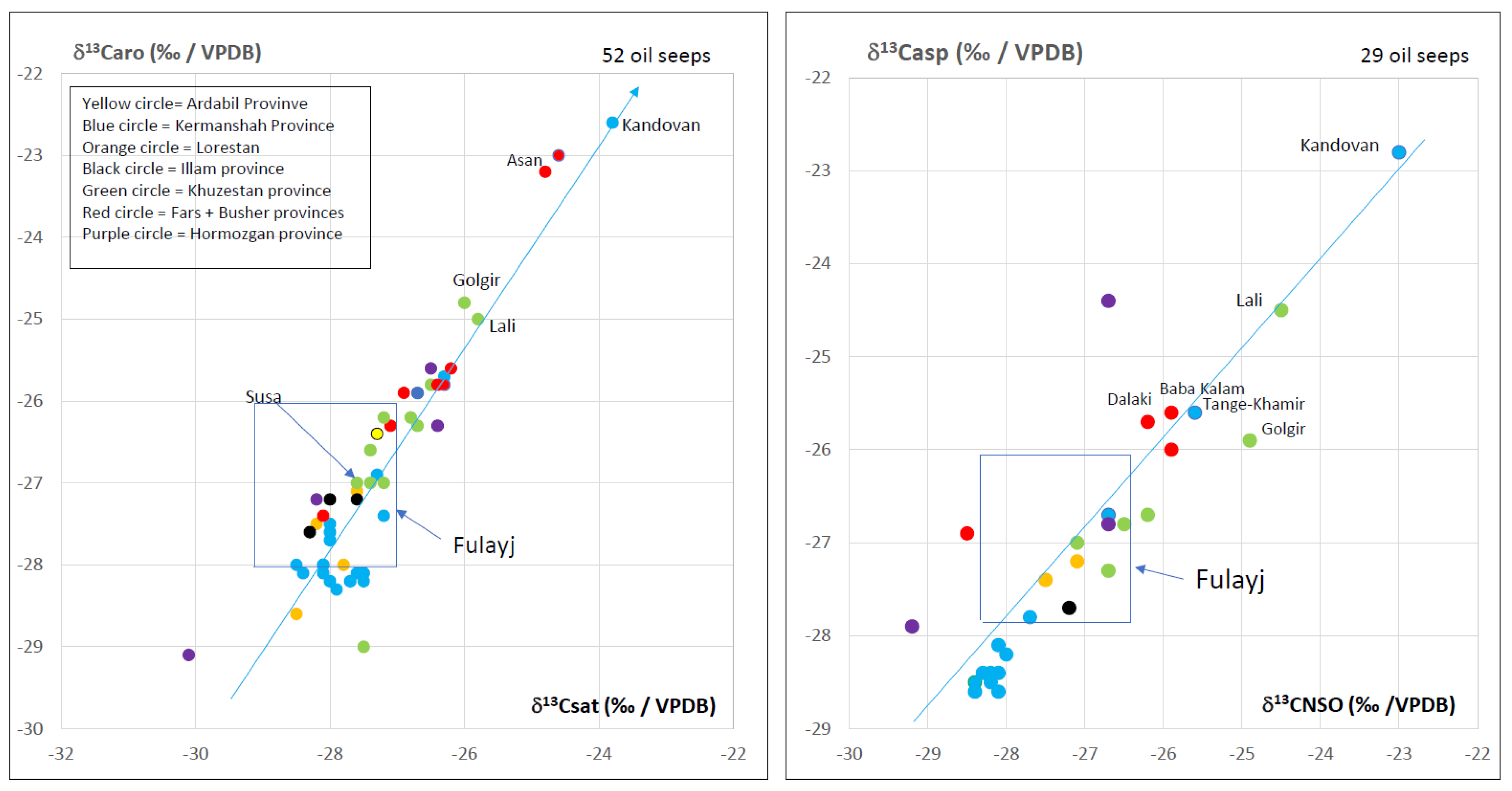

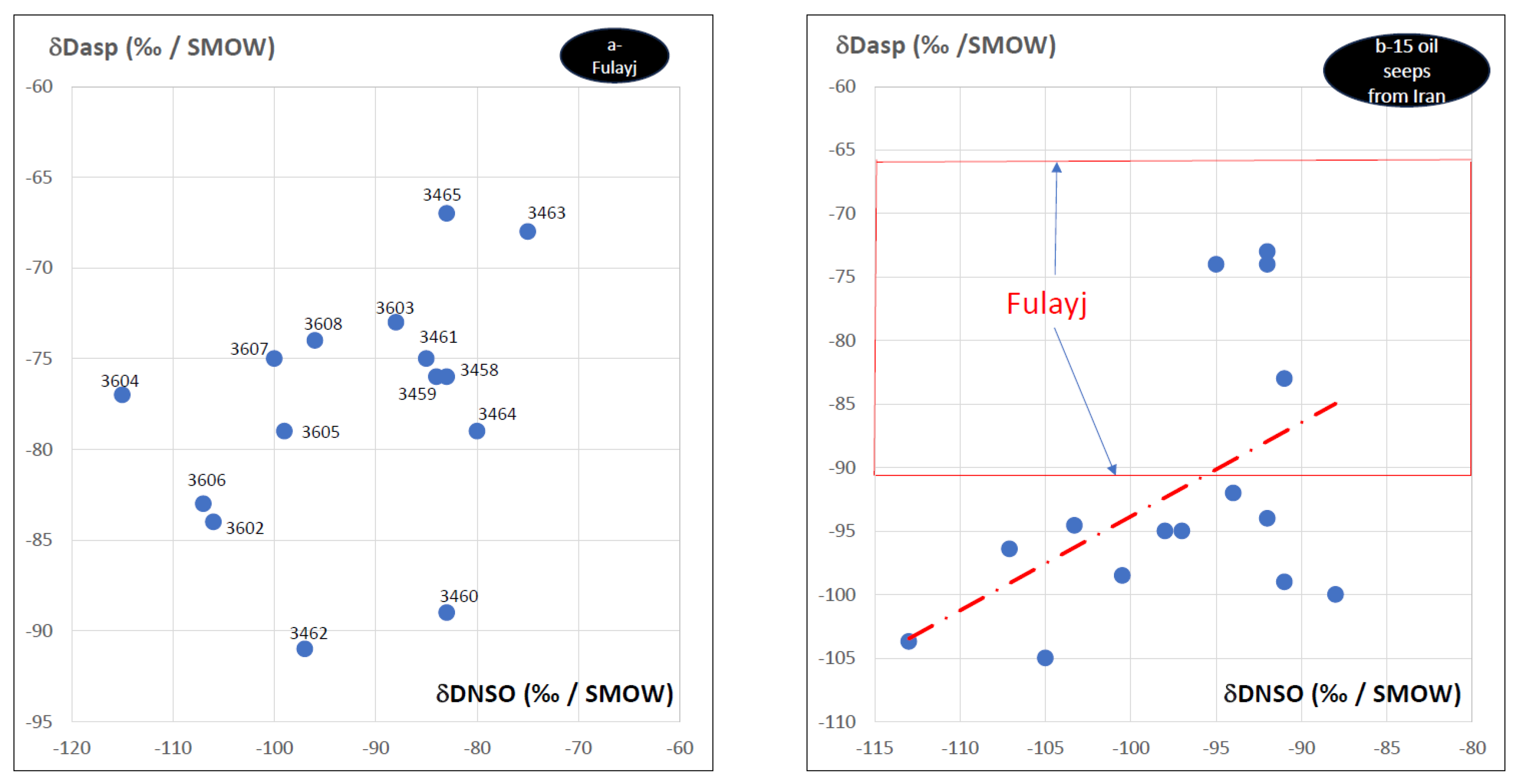

4.2. Isotope Data

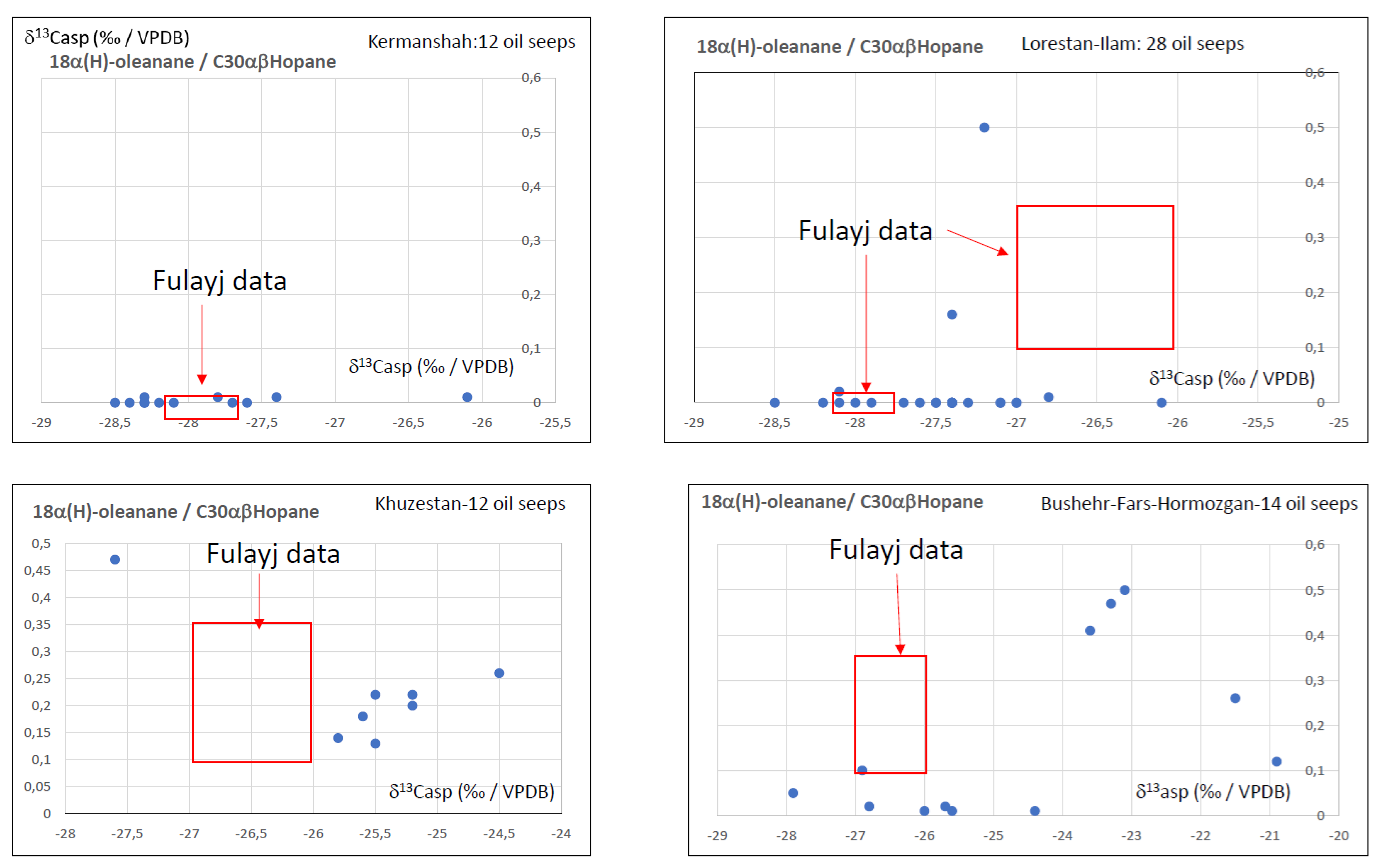

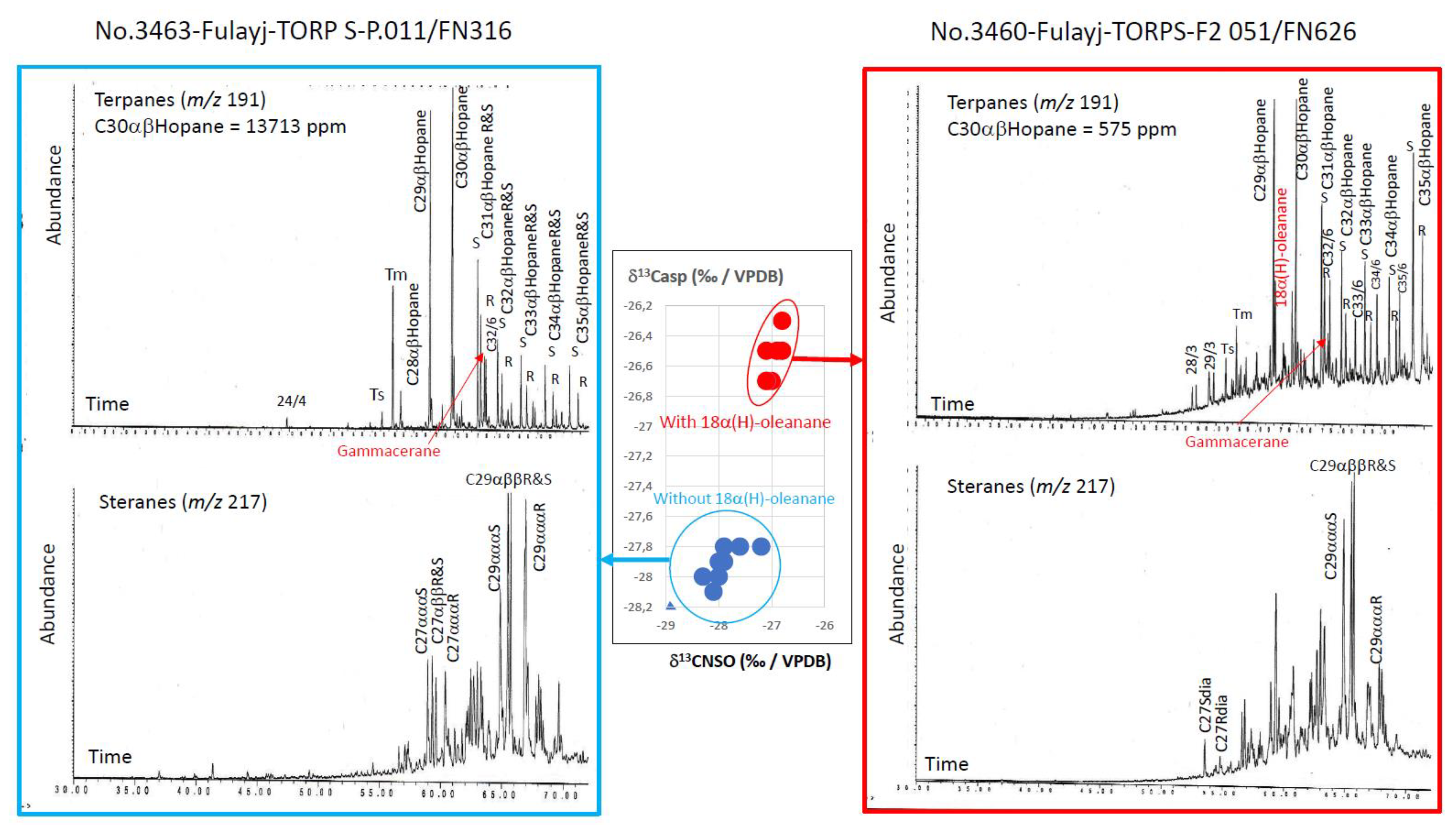

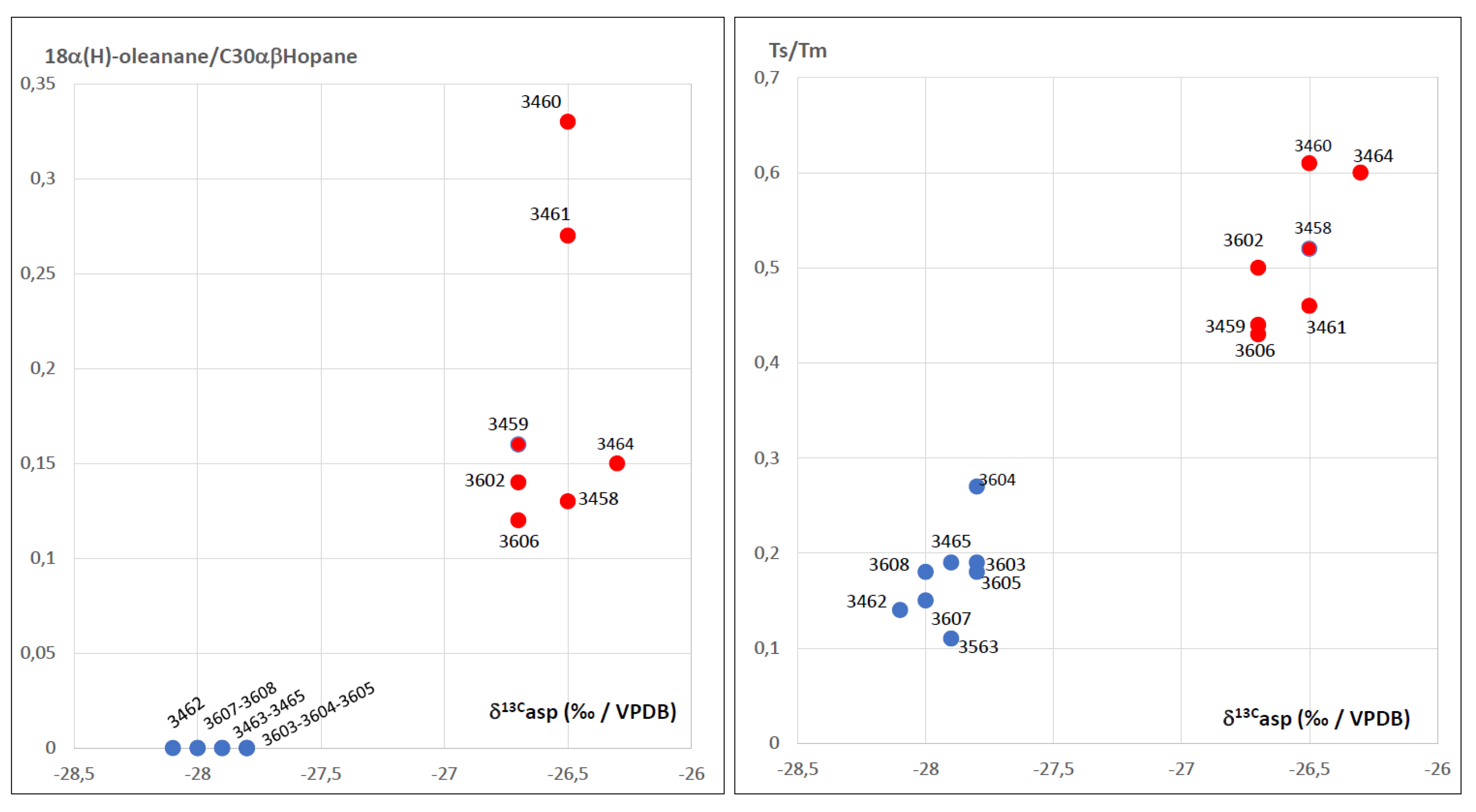

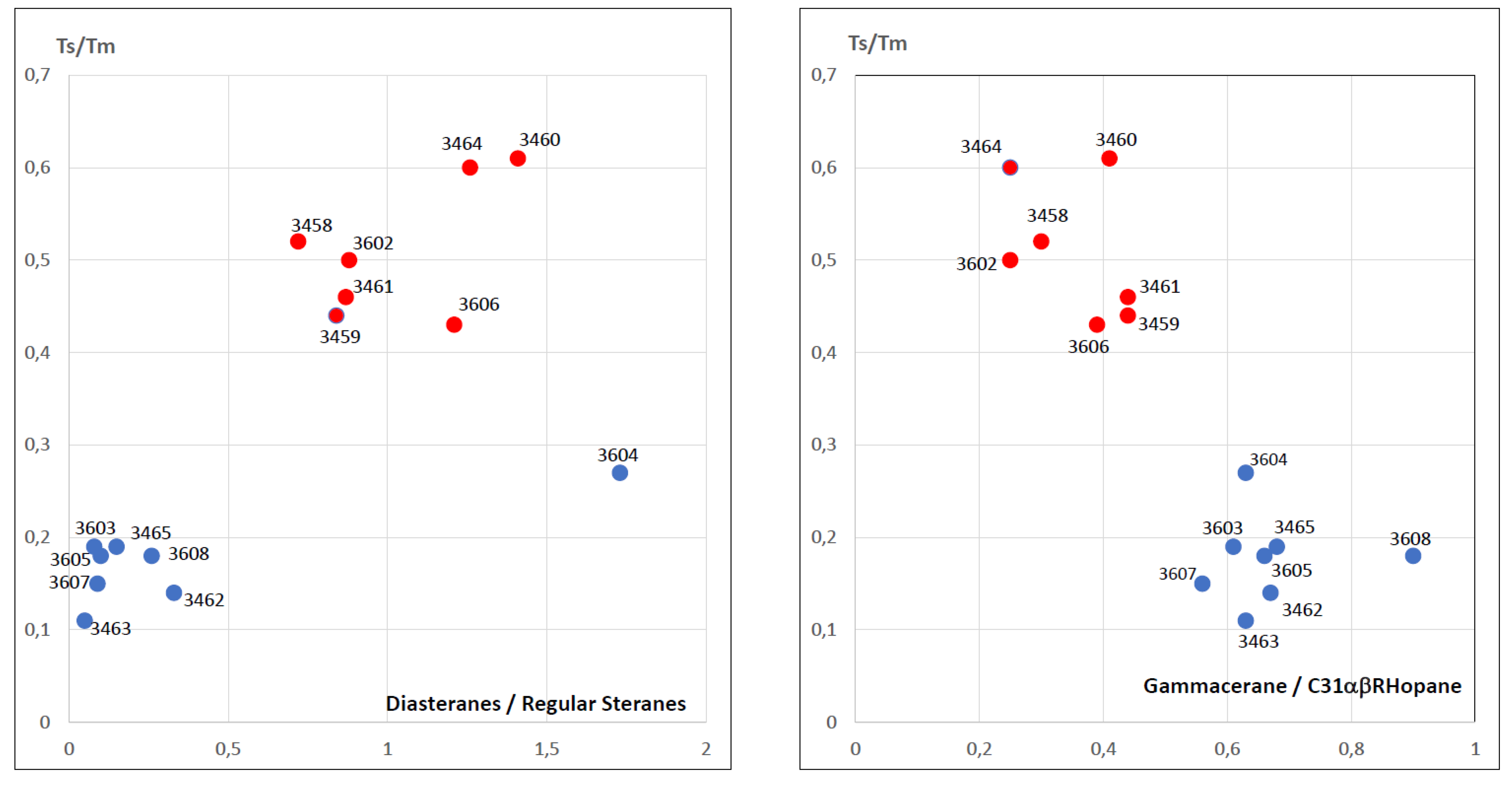

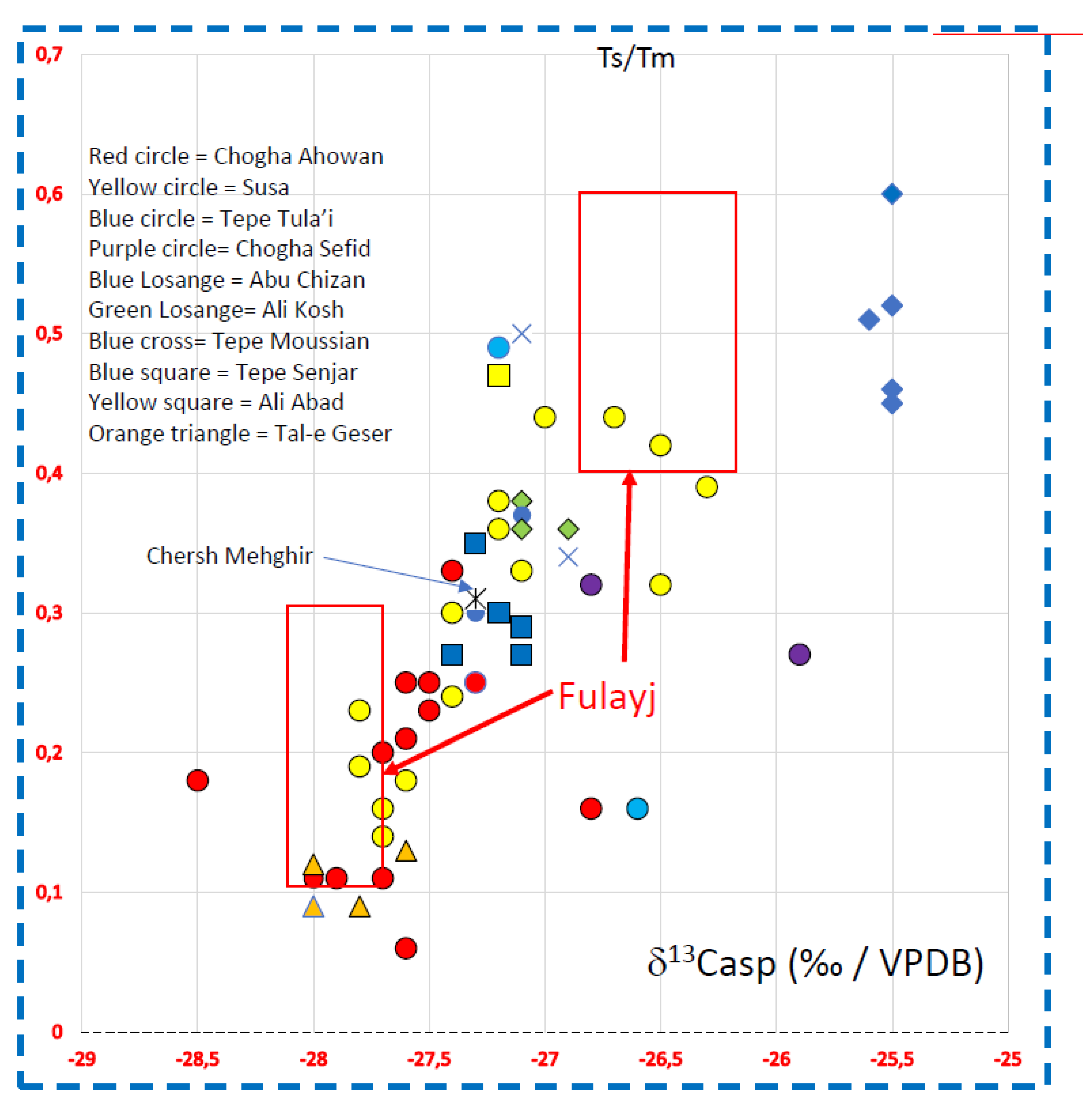

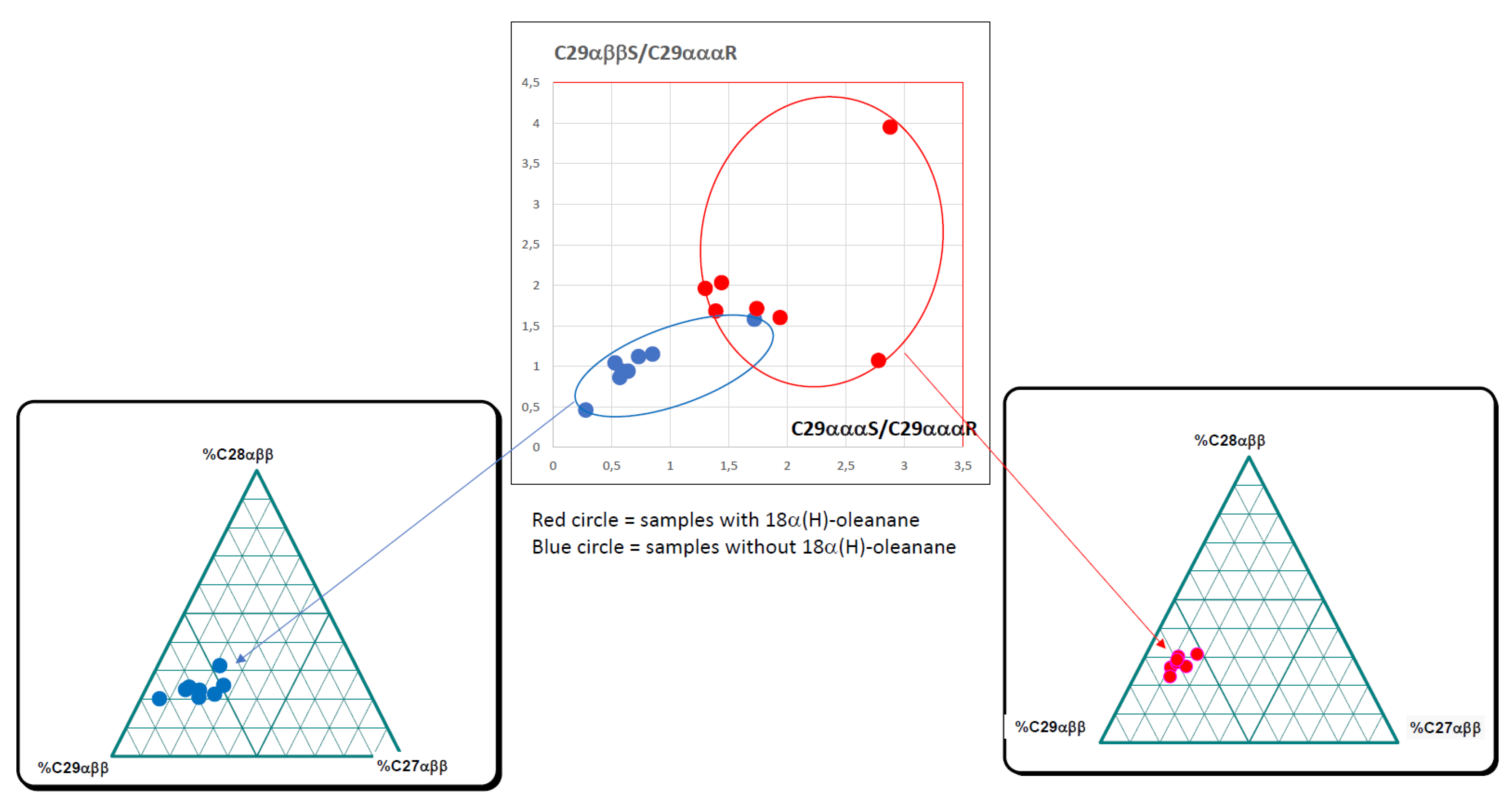

4.3. Steranes and Terpanes

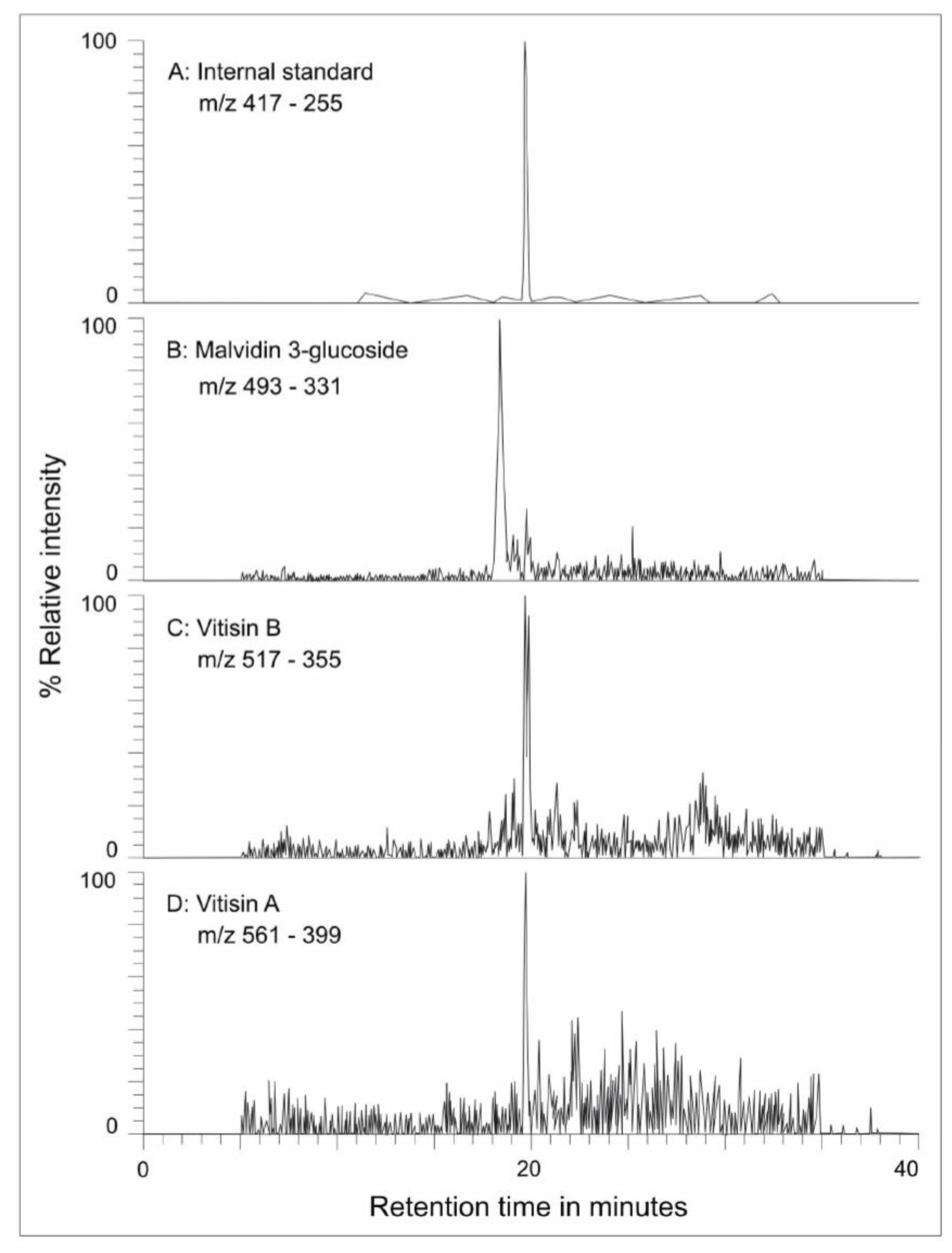

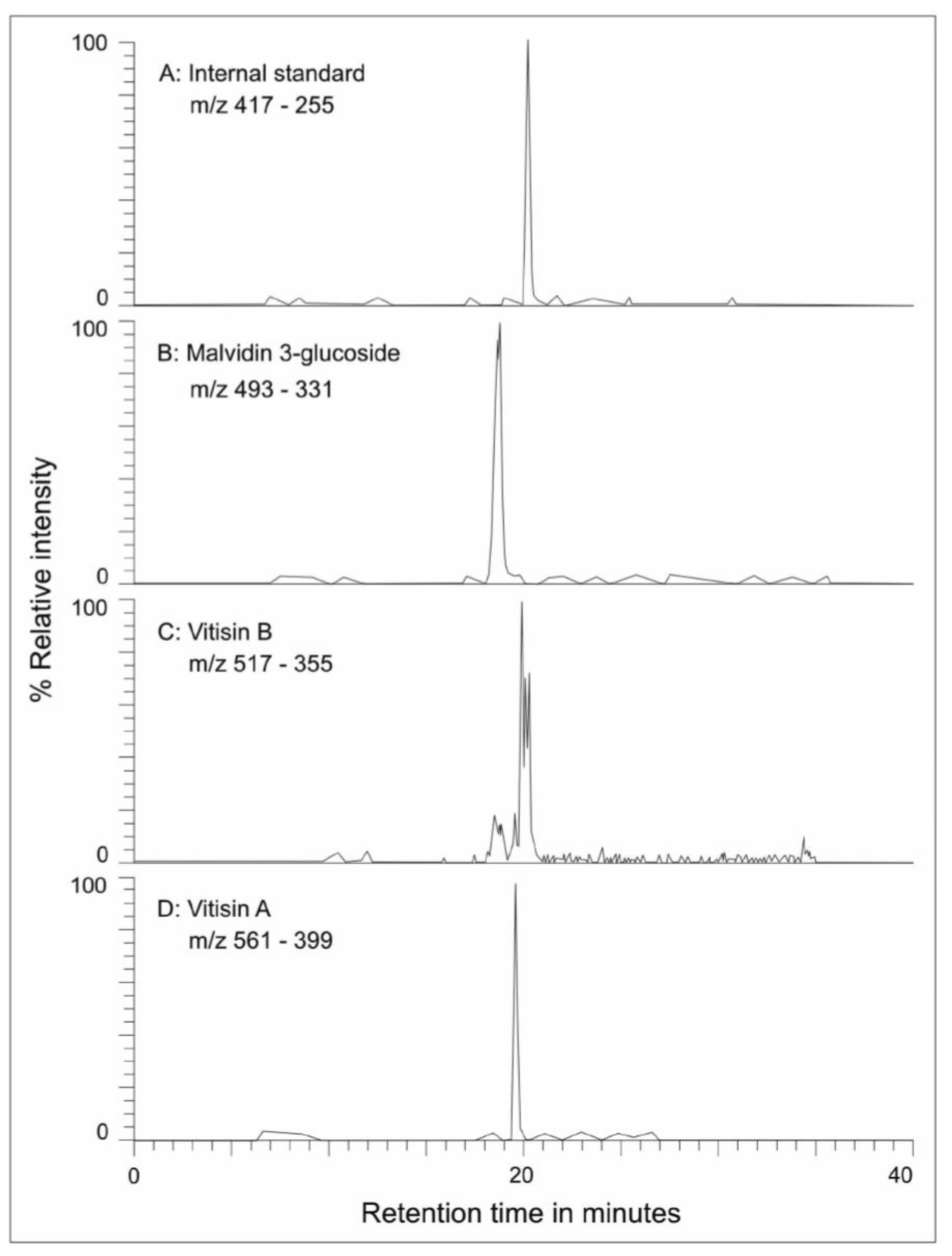

4.5. Identification of Wine

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Stern, B.; Connan, J.; Blakelock, E.; Jackman, R.; Coningham, R.A.E.; Heron, C. From Susa to Anuradhapura: reconstructing aspects of trade and exchange in bitumen-coated ceramic vessels between Iran and Sri Lanka in the Third to the Ninth centuries AD. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Priestman, S.; Vosmer, T.; Komoot, A.; Tofighian, H.; Ghorbani, B.; Engel, M.H.; Zumberge, A.; Van de Velde, T. Geochemical analysis of bitumen from West Asian torpedo jars from the c. 8th century Phanom-Surin shipwreck in Thailand. Journal of Archaeological Science 2020, 117, 105111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Engel, M.H.; Jackson, R.; Priestman, S.; Vosmer, T.; Zumberge, A. Geochemical Analysis of Two Samples of Bitumen from Jars Discovered on Muhut and Masirah Islands (Oman). Separations 2021, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomber, R.; Spataro, M.; Priestman, S. Early Islamic Torpedo Jars from Siraf: Scientific Analyses of the Clay Fabric and Source of Indian Ocean Transport Containers. Iran 2022, 60, 240–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestman, S.; al-Jahwari, N.; MacDonald, E.; Kennet, D.; Alzeidi, K.; Andrews, M.; Dabrowski, V.; Kenkadze, V.; MacDonald, R.; Mamalashvili, T.; Al-Maqbali, I.; Naskidashvili, D.; Rossi, D. Fulayj: A Sasanian to Early Islamic Fort in the Sohar Hinterland. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 2023, 52, 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- al-Jahwari, N. , Kennet, D. Priestman, S., Sauer, E. Fulayj: A Late Sasanian Fort on the Arabian Coast. Antiquity 2018, 92, 724–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestman, S.M.N. The archaeology of Early Islam in Oman: Recent Discoveries from Fulayj on the Batinah. The Anglo-Omani Society Review 2019, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Connan, J.; Adelsberger, K.A.; Engel, M.; Zumberge, A. Bitumens from Tell Yarmuth (Israel) from 2800 BCE to 1100 BCE : A unique case history for the study of degradation effects on the Dead Sea bitumen. Organic Geochemistry 2022, 168, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elezi, G.; H Barnard, H. , Whitelegge, J. Novel method for the detection of ancient wine biomarkers in archaeological pottery, In preparation.

- Forbes, R.J. Studies in Ancient Technology. Volume 1: Bitumen and Petroleum in Antiquity. 1955, Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Marschner, R.F.; Wright, H.T. Asphalt from Middle Eastern Archaeological Sites. Archaeological Chemistry 1, Advances in Chemistry Series, 1978, Chicago, 97-112.

- Connan, J. Le bitume dans l’Antiquité. 2012, Arles: Errance, Actes Sud.

- Connan, J.; Nissenbaum, A.; Dessort, D. Molecular archaeology: Export of Dead Sea asphalt to Canaan and Egypt in the Chalcolithic-Early Bronze Age (4th-3rd millennium BC). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1992, 56, 2743–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Nishiaki, Y. The bituminous mixtures of Tell Kosak Shamali on the Upper Euphrates (Syria) from the Early Ubaid to the Post Ubaid: Composition of mixtures and origin of bitumen. In: Nishiaki, Y., Matsutani, T. (Eds.), Tell Kosak Shamali-The Archaeological Investigations on the Upper Euphrates, Syria, Chalcolithic Technology and Subsistence. The University Museum and The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan, 2003, Vol.II, Chapter 18, pp. 283–306.

- Connan, J.; Nissenbaum, A.; Imbus, K.; Zumberge, J.; Macko, S. Asphalt in iron age excavations from the Philistine Tel Miqne-Ekron city (Israel) : Origin and trade routes. Organic Geochemistry 2006, 37, 1768–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Carter, R. A geochemical study of bituminous mixtures from Failaka and Umm an-Namel (Kuwait), from the Early Dilmun to the Early Islamic period. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 2007, 18, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Kavak, O.; Sağlamtimur, H.; Engel, M.; Zumberge, A.; Zumberge, J. A geochemical study of bitumen residues on ceramics excavated from Early Bronze graves (3000-2900 BCE) at Başur Höyük in SE Turkey. Organic Geochemistry 2018, 115, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Adelsberger, K.A.; Engels, M.H.; Zumberge, A. Bitumens from Tell Yarmuth (Israel) form 2800 BCE to 1100 BCE: A unique case history for the study of degradation effects on the Dead Sea bitumen. Organic Geochemistry 2022, 168, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissenbaum, A.; Connan, J. Application of organic geochemistry to the study of Dead Sea asphalt in archaeological sites from Israel and Egypt. In: Pike, S., Gitin, S. (Eds.), The Practical Impact of Science on Near Eastern and Aegean Archaeology., Wiener laboratory Publication, 3, 1999, Archetype Publications Ltd, London, 91-98.

- Schwartz, M.; Hollander, D. The Uruk expansion as dynamic process: A reconstruction of Middle to Late Uruk exchange patterns from bulk isotope analyses of bitumen artifacts. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2016, 7, 884–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.; Hollander, D.; Stein, G.J. Reconstructing Mesopotamian exchange networks in the 4th millenium BC: geochemical and archaeological analyses of bitumen artifacts from Hacinebi Tepe, Turkey. Paléorient 2000, 25, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Connan, J.; Poister, K.M.; Vellanoweth, R.L.; Zumberge, J.; Engel, M.H. Sourcing archaeological asphaltum (bitumen) from the California Channel Islands to submarine seeps. Journal of Archaeological Science 2014, 43, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneels, A.; Romo de Vivar-Romo, A.; Linares-Jurado, A.; Reyes-Lezama, M.; Tapia-Mendoza, E.; Morales-Puente, P.; Cienfuegos-Alvarado, E.; Otero-Trujano, F.J. Chemical analysis of bitumen paint on classic period Central Veracruz ceramics, Mexico. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2018, 17, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, C.J.; Lu, S.-T. Sourcing archaeological bitumen in the Olmec region. Journal of Archaeological Science 2006, 33, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrié-Duhaut, A.; Lemoine, S.; Adam, P.; Connan, J.; Albrecht, P. Abiotic oxidation of bitumens under natural conditions. Org.Geochem. 2000, 31, 977–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkan, S.A.M. Geochimie organique des roches mères et des huiles du basin de Zagros (Iran). Thèse, Université Henri Poincaré, Nancy I, 1998.

- Moldowan, J.M.; Seifert, W.K.; Gallegos, E.J. Relationship between petroleum composition and depositional environment of petroleum source rocks. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin 1985, 69, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Sheng, G.; Peng, P.; Brassell, S.C.; Eglinton, G.; Jigang, J. Peculiarities of salt lake sediments as potential source rocks in China. Organic Geochemisty 1986, 10, 119–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Connan, J. , Genç, E., Kavak, O., Engel, M.H., Zumberge, A. Geochemistry and origin of bituminous samples of Kuriki Höyük (SE Turkey) from 4000 BCE to 200 CE: comparison with Kavuşan Höyük, Hakemi Use and Salat Tepe. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2022, 41, 103348. [Google Scholar]

- Connan, J. , Lombard, P., Killick, R., Højlund, F., Salles, J.F., Kalaf; A.The archaeological bitumen of Bahrain from the early Dilmun period (c. 2200 BC) to the sixteenth century AD: a problem of source and trade. Arab. Archeol.Epigr 1998, 9, 141–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boëda, E. , Connan, J., Muhesen, S. Bitumen as hafting material on Middle Paleolithic artefacts from the El Kown Basin, Syria. In: Akazawa, T., Aoki, K., Bar Yosef, O. (Eds.), Neanderthals and Modern Humans in Western Asia, Plenum, New York, 1998, pp.181-204.

- 32 Seifert, W. , Moldowan, M., Demaison, G., Source correlation of biodegraded oils. Org.Geochem. 1984, 6, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chosson, P.; Connan, J.; Dessort, D.; Lanau, C. In vitro biodegradation of steranes and terpanes: a clue to understanding geological situations. In Albrecht P., Moldowan, M., Philp, P. (Eds.). Biological markers in sediments and petroleum, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1991a, pp.320-349.

- Chosson, P.; Lanau, C.; Connan, J.; Dessort, D. Biodegradation of refractory hydrocarbons from petroleum under laboratory conditions. Nature 1991, 351, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morata, A. , Calderón, F. , González, M. C., Gómez-Cordovés, M.C., Suárez., J.A. “Formation of the Highly Stable Pyranoanthocyanins (Vitisins A and B) in Red Wines by the Addition of Pyruvic Acid and Acetaldehyde.”. Food Chemistry 2007, 100, 1144–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, V. , Mateus., N. Formation of pyranoanthocyanins in red wines: a new and diverse class of anthocyanin derivatives. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Country | Archaeological Reference | Phase | Date Range | Wine Biomarkers | Bitumen Source | Lab Number | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fulayj | Oman | F2.041/FN405 | 2a | Mid-3rd - mid-6thC | Kermanshah | 3458 | 1 | |

| F2.051/FN626 | 2a | Mid-3rd - mid-6thC | Yes | Kermanshah | 3460 | 3 | ||

| F2.059/FN596 | 2a | Mid-3rd - mid-6thC | Kermanshah | 3461 | 4 | |||

| F2.059/FN610 | 2a | Mid-3rd - mid-6thC | Khuzistan | 3462 | 5 | |||

| F3.022/FN475 | 2a | Mid-3rd - mid-6thC | Kermanshah | 3606 | 13 | |||

| F3.023/FN512 | 2a | Mid-3rd - mid-6thC | Khuzistan | 3607 | 14 | |||

| P.012/FN423 | 2c | Early 5th - mid-6thC | Yes | Khuzistan | 3465 | 8 | ||

| F2.090/FN787 | 2c | Early 5th - mid-6thC | Khuzistan | 3603 | 10 | |||

| F2.042/FN513 | 3 | Mid-6th - late 7thC | Yes | Kermanshah | 3459 | 2 | ||

| F3.015/FN305 | 3 | Mid-6th - late 7thC | Khuzistan | 3605 | 12 | |||

| P.011/FN316 | 4a | Residual post 7thC | Yes | Khuzistan | 3463 | 6 | ||

| P.011/FN338 | 4a | Residual post 7thC | Yes | Kermanshah | 3464 | 7 | ||

| F2.022/SV182 | 4a | Residual post 7thC | Kermanshah | 3602 | 9 | |||

| F3.007/FN208 | 4a | Residual post 7thC | Khuzistan | 3604 | 11 | |||

| R.003/FN123 | 4b | Residual post 7thC | Khuzistan | 3608 | 15 |

| sample number | Geomark reference | location | country | EO %/sample | %sat | %aro | %HC | %NSO | %asp | %pol | total | d13Csat | d13Caro | d13CNSO | d13Casp | dDNSO average | dDasp average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3458 | UNK0934 | Fulayj | Oman | 50.5 | 1.8 | 2 | 3.8 | 9 | 87.2 | 96.2 | 100 | -27.9 | -26.8 | -26.9 | -26.5 | -83 | -76 | oleanana | ||

| 3459 | UNK0935 | 39.4 | 1.7 | 2 | 3.7 | 11.3 | 85 | 96.3 | 100 | -27.7 | -26.8 | -27 | -26.7 | -84 | -76 | pas d'oleanane | ||||

| 3460 | UNK0936 | 43.7 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 8.2 | 87.7 | 95.9 | 100 | -27.3 | -26.6 | -26.8 | -26.5 | -83 | -89 | |||||

| 3461 | UNK0937 | 40.8 | 2 | 2.9 | 4.9 | 18.6 | 76.5 | 95.1 | 100 | -27.5 | -27.8 | -27.1 | -26.5 | -85 | -75 | |||||

| 3462 | UNK0938 | 15.1 | 3.3 | 6 | 9.3 | 37.1 | 53.6 | 90.7 | 100 | -27.3 | -27.1 | -28.1 | -28.1 | -97 | -91 | |||||

| 3463 | UNK0939 | 38.0 | 1 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 9 | 88.4 | 97.4 | 100 | -29 | -28 | -28 | -27.9 | -75 | -68 | |||||

| 3464 | UNK0940 | 58.9 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 7 | 89.2 | 96.2 | 100 | -27.6 | -26.8 | -26.8 | -26.3 | -80 | -79 | |||||

| 3465 | UNK0941 | 35.4 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 4 | 11.7 | 84.3 | 96 | 100 | -28.4 | -27.8 | -27.9 | -27.9 | -83 | -67 | |||||

| 3602 | UNK1119 | 47.8 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 13.4 | 82.4 | 95.8 | 100 | -27.5 | -26.3 | -27.1 | -26.7 | -106 | -84 | |||||

| 3603 | UNK1120 | 39.6 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 8.6 | 88.3 | 96.9 | 100 | -28.8 | -27.5 | -27.6 | -27.8 | -88 | -73 | |||||

| 3604 | UNK1121 | 45.6 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 8.2 | 11.8 | 80.1 | 91.8 | 100 | -29.1 | -27.3 | -27.2 | -27.8 | -115 | -77 | |||||

| 3605 | UNK1122 | 37.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 8.9 | 88.6 | 97.5 | 100 | -28.8 | -27.6 | -27.9 | -27.8 | -99 | -79 | |||||

| 3606 | UNK1123 | 9.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 7.2 | 20.9 | 71.9 | 92.8 | 100 | -27.6 | -26.1 | -27.1 | -26.7 | -107 | -83 | |||||

| 3607 | UNK1124 | 43.7 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 11.9 | 84.3 | 96.3 | 100 | -28.7 | -27.1 | -28 | -28 | -100 | -75 | |||||

| 3608 | UNK1125 | 23.1 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 9.5 | 87.6 | 97.1 | 100 | -28.1 | -27.6 | -28.3 | -28 | -96 | -74 | |||||

| 13.01921 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 37.9 |

| lab number | GeoMark number | site | C30Hppm | Tet/C23 | C29/H | OL/H | C31R/H | GA/C31R | GA/H | C35S/C34S | ster/Terp | Dia/Reg | %C27 | %C28 | %C29 | C2920S/R | C29abb/C29aaaR | Ts/Tm | tricyclics | terpanes | steranes | C27diasteranes | c29aaaRsterane |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3458 | UNK0934 | Fulayj | 2001 | 2.01 | 0.96 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.3 | 0.11 | 1.3 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 11.1 | 30.2 | 58.7 | 1.39 | 1.68 | 0.52 | almost absent | well preserved | biodegraded | present | altered |

| 3459 | UNK0935 | Fulayj | 642 | 1.08 | 0.93 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 1.94 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 10.4 | 26.4 | 63.2 | 1.94 | 1.6 | 0.44 | almost absent | slightly biodegraded? | biodegraded | present | altered |

| 3460 | UNK0936 | Fulayj | 575 | 1.35 | 1.02 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 2.14 | 0.65 | 1.41 | 11.6 | 28.1 | 60.2 | 2.88 | 3.95 | 0.61 | almost absent | biodegraded | biodegraded | present | altered |

| 3461 | UNK0937 | Fulayj | 157 | 0.94 | 1.13 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 3.47 | 0,,18 | 0.87 | 15.5 | 26.7 | 57.8 | 2.78 | 1.07 | 0.46 | almost absent | biodegraded | biodegraded | traces | altered |

| 3462 | UNK0938 | Fulayj | 1632 | 1.09 | 1 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.25 | 1.11 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 18.7 | 23.1 | 58.2 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.14 | almost absent | well preserved | preserved | traces | preserved |

| 3463 | UNK0939 | Fulayj | 13716 | 6.63 | 0.93 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 19.8 | 20.6 | 59.6 | 0.64 | 0.94 | 0.11 | almost absent | well preserved | preserved | absent | preserved |

| 3464 | UNK0940 | Fulayj | 1321 | 1.06 | 0.96 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 1.51 | 0.57 | 1.26 | 17 | 31 | 52 | 1.44 | 2.03 | 0.6 | almost absent | well preserved | slighly biodegraded? | abundant | altered |

| 3465 | UNK0941 | Fulayj | 5556 | 3.57 | 1.24 | 0 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 1.18 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 13.8 | 23.3 | 62.9 | 0.85 | 1.15 | 0.19 | almost absent | well preserved | preserved? | traces | preserved |

| 3602 | UNK1119 | Fulayj | 2536 | 1.55 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.1 | 1.19 | 0.2 | 0.88 | 11.2 | 29.1 | 59.8 | 1.3 | 1.96 | 0.5 | absent | well preserved | biodegraded | low present | biodegraded |

| 3603 | UNK1120 | Fulayj | 11306 | 3.21 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 1.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 26.2 | 24.8 | 49 | 0.53 | 1.04 | 0.19 | almost absent | well preserved | well preserved?? | almost absent | preserved |

| 3604 | UNK1121 | Fulayj | 2424 | 1.94 | 1.18 | 0 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.73 | 21.4 | 31.7 | 46.9 | 0.73 | 1.12 | 0.27 | absent | well preserved | preserved | abundant | preserved |

| 3605 | UNK1122 | Fulayj | 9480 | 5.72 | 1.14 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 1.88 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 14.6 | 24.2 | 61.2 | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.18 | absent | well preserved | biodegraded | traces | preserved |

| 3606 | UNK1123 | Fulayj | 1617 | 1.12 | 0.9 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 1.81 | 0.14 | 1.21 | 11.8 | 23.2 | 65 | 1.74 | 1.71 | 0.43 | absent | well preserved? | biodegraded | present | biodegraded |

| 3607 | UNK1124 | Fulayj | 16149 | 3.66 | 1.04 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.19 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 24.6 | 21.7 | 53.7 | 0.59 | 0.94 | 0.15 | almost absent | well preserved | biodegraded? | traces | preserved |

| 3608 | UNK1125 | Fulayj | 1723 | 1.35 | 1.19 | 0 | 0.31 | 0.9 | 0.28 | 2.78 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 6.4 | 20.1 | 73.5 | 1.72 | 1.58 | 0.18 | almost absent | well preserved? | biodegraded | traces | bioegraded |

| lab number | site | Malvidin 3-Glucoside | Vitisin A | Vitisin B | Daidzin (Internal standard) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3458 | Fulayj | absent | absent | absent | present |

| 3459 | Fulayj | absent | absent | present | present |

| 3460 | Fulayj | absent | absent | present | present |

| 3461 | Fulayj | absent | absent | absent | present |

| 3462 | Fulayj | absent | absent | absent | present |

| 3463 | Fulayj | present | absent | present | present |

| 3464 | Fulayj | present | absent | present | present |

| 3465 | Fulayj | present | absent | present | present |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).