1. Introduction

Maximal oxygen uptake (

O

2max) is one of the most studied indicators of physical fitness across different approaches and age groups [

1,

2]. It has been used to categorize levels of physical activity and its relationship with coronary heart disease mortality [

3]. From a sports perspective,

O

2max has been used to compare athletes and different sports, monitor performance, and verify changes among other applications [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Typically, treadmill or cycle ergometer are used to access

O

2max, allowing for the dynamic analysis of cardiopulmonary responses [

1]. In fact, it delivers information of

O

2max related variables (e.g., velocity at maximal oxygen uptake—v

O

2max), ventilatory thresholds, heart rate, and respiratory quotient, among others [

1].

We are observing an increasing interest in this physiological parameter among pediatric and adolescent populations [

2,

9]. Nevertheless, some studies involve quite heterogeneous populations, including school-aged youth, young athletes in training, and young athletes with professional prospects [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Baquet et al. [

10] analyzed the response to seven weeks of high-intensity endurance training in schoolchildren aged 9 to 10 years. The authors measured

O

2max on-field using the 20-meter shuttle run test (20m-SRT), where the schoolchildren improved their

O

2max by ~8% [

10]. Ruiz et al. [

12] compared values of

O

2max from schoolchildren when applying the 20m-SRT, and observed excellent correlation (r = 0.97) between on-field measured and estimated

O

2max values [

12]. Ramírez et al. applied the 20m-SRT with gas analysis in adolescents to study the association between

O

2max and physical activity levels [

11]. Bruzzese et al. [

13] analyzed

O

2 kinetics during a simulated competition in adolescent tennis players. All these studies have something in common, they employed on-field tests using portable or wearable equipment for gas exchange assessment, allowing researchers explore

O

2 response and related variables among different scenarios [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Despite that, studies measuring

O

2max in youth and/or adolescent soccer players are scarce. Chamari et al. [

5] reported average

O

2max values of 4.3 ± 0.4 L·min

−1 (61.1 ± 0.4 mL·kg

−1·min

−1) adolescent soccer players. Gomez-Piqueras et al. [

6] measured

O

2max in soccer players under 15 years old, reporting average values of 56 mL·kg

−1·min

−1, however, they do not report data in absolute terms (L·min

−1). In younger age categories, scientific evidence in soccer is limited [

14]. However, these studies have directly measured

O

2max by applying protocols on treadmills. While

O

2max values should not differ from those obtained in field tests, a significant disparity in the velocity at which

O

2max is reached (v

O

2max) would be expected, with lower values observed in field tests [

8,

15]. The v

O

2max is typically used by coaches to segment training loads at these ages [

8,

16].

Argentina being the current and three-time World Cup champion, as well as the current and most successful team in Copa América history, but there are no cardiopulmonary related studies on this population. On-field tests, particularly if using portable or wearable equipment for gas exchange assessment, are valuable to better understand the cardiopulmonary response in soccer players, providing relevant health and performance related information for the development of youth and professional athletes. Thus, the primary aim was to identify on-field cardiopulmonary fitness profile of youth players from the Argentine Football Association (AFA). Our hypothesis was that youth players from AFA have lower cardiopulmonary fitness than elite first-division soccer players.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study population consisted of ten (N = 10) highly trained youth Argentine soccer players participating in the first league of the Argentine Football Association (AFA) in the youth categories. Regarding inclusion criteria, participants should be federated AFA soccer player, actively competing, and having trained continuously for at least two years. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee while adhering to Resolution 1480/11 of the Ministry of Public Health of Argentina. All players received medical clearance from the club's physician, including a physical fitness certification, and parental approval was obtained.

2.2. Procedures

The experimental protocol took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in November 2022, during the break for the Qatar 2022 World Cup. The players were scheduled to arrive at 9:00am. Measurements were taken on the training field with the players wearing their competition attire (

Figure 1). Each volunteer completed one testing session under similar atmospheric conditions. Each session comprised anthropometric assessments, baseline measurements (5 min of passive rest), 5 min on-field warm-up at a moderate intensity followed by 5 min of passive recovery, and an on-field 20m-SRT while coupled with a wearable metabolic system for cardiopulmonary assessment.

2.3. Anthropometric Component

Body mass and standing height were measured according to the protocols established by the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry. The players were weighed without shoes using a portable electronic scale (TANITA) with a resolution of 0.1 kg. Height was measured with a stadiometer (SECA 206). Body Mass Index (BMI; kg·m

-²) was calculated. Peak height velocity (PHV) was estimated [

17].

2.4. Cardiopulmonary Component and 20-Meter Shuttle Run Test

The cardiopulmonary exercise test was conducted on-field using the 20-meter shuttle run test (20m-SRT) [

16,

18]. This test involves running back and forth between two lines set 20 meters apart, following the pace set by an audio signal. The test starts at a running velocity of 8.5 km·h

-1 and increases by 0.5 km·h

-1 each minute. The average temperature during the test ranged from 22 to 24°C.

All participants used a portable gas-analyzer for cardiopulmonary assessment, the K5 wearable metabolic system® (Cosmed K5, Cosmed, Rome, Italy), Initially, preliminary warm-up and calibration routines were applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Pulmonary gas exchange was continuously measured using the mixed chamber method, at rest (2 min) and during the 20-mSRT. The mixing chamber option applied to K5, involves a dynamic micro-mixing chamber technology (IntelliMET™, Patent US 9581539) where proportional fractions of expired gas of some breaths are sampled inside a small chamber of ~2 mL (a conventional mixing chamber has 6–8 L), thus a moving average of gas fractions is obtained to calculate mean O2 and carbon dioxide production (CO2) values.

First (VT1) and second ventilatory thresholds (VT2), their respective running velocities (vVT1 and vVT2), as well as the respiratory exchange ratio (RER), were calculated (19). The O2max and respective velocity (vO2max) was accepted when at least two of the following criteria were met: a) flattening off O2max despite an increase in running velocity (ΔO2 < 150 ml O2), b) reaching an RER of 1.09 or higher, and c) inability to continue running. All participants avoided vigorous exercise in the previous 24 h, were well-fed and hydrated, and abstained from caffeine, alcohol, or any stimulant drink the day prior to and on test days. Similar meals 24 hours before both tests were recommended for the participants.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The sample size was selected by convenience, focusing on highly trained Argentine soccer players participating in the first league of the Argentine Football Association (AFA) in the youth categories. Normality was verified and confirmed with the Shapiro–Wilk’s Test, with alpha significance level established at 0.05. A descriptive analysis was applied and reported for all variables.

3. Results

A total of 10 male youth soccer players were measured on-field. The average maturational age was at the point of peak height velocity (PHV). However, the minimum and maximum values found indicate that there were children who were -2.17 years and +2.16 years from PHV, suggesting they were between Tanner stages 2 and 5.

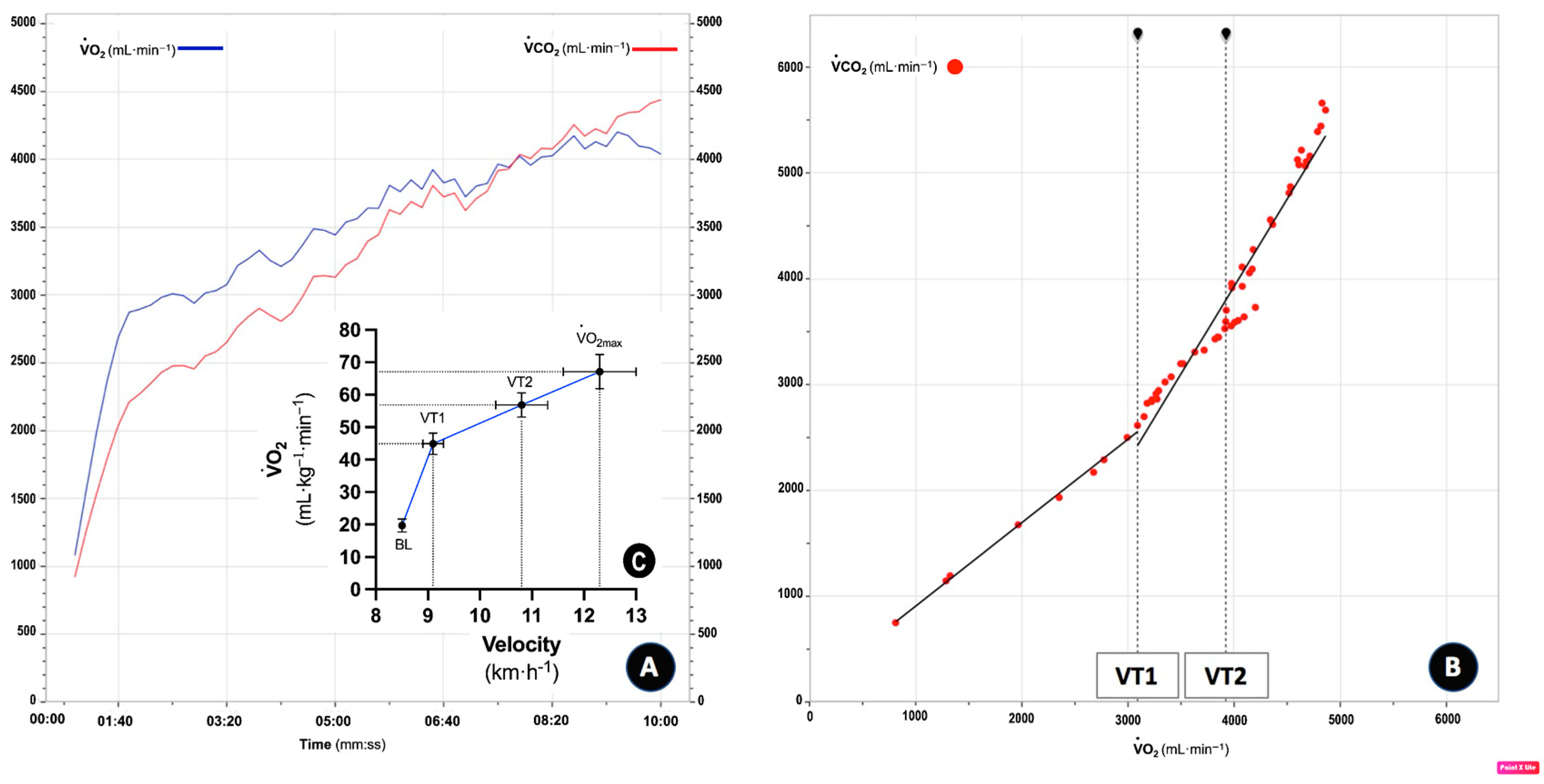

Figure 2 (Panel A and B) displays the

O

2 and

CO

2 kinetics, along with the identification of the ventilatory thresholds VT1 and VT2 of a single participant.

Figure 2 panel C shows mean values and standard deviations for

O

2 at VT1,

O at VT2 and

O

2max, and respective velocities during the 20m-SRT.

O2 and CO2 vs time during a 20m-SRT (Panel A), and ventilatory thresholds VT1 and VT2 (panel B); Panel C shows mean values and standard deviations for O2 at VT1, O at VT2 and O2max, and respective velocities during the 20-meter shuttle run test (20m-SRT; N=10).

4. Discussion

The main aim of the current study was to identify on-field cardiopulmonary fitness profile of youth players from the Argentine Football Association (AFA). This was the first time such on-field measurements were conducted at in Argentina with youth soccer players (see

Table 1 and

Figure 2).

In our study, mean

O

2max during the 20m-SRT was 67.1 ± 5.3 mL·kg

−1·min

−1, similar to those found in professional adult soccer players [

4], which is consistent with several previously published studies. Chamari et al. [

5] measured

O

2max in 34 youth soccer players from Tunisia and reported average values of 61.1±4.6 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. The same research group measured

O

2max in ten youth soccer players from Norway [20] and reported average values of 65.4 ± 5.0 mL·kg

−1·min

−1 and 70.7±4.3 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. On the other hand, McMillan et al. [21] measured

O

2max in eleven youth soccer players from Scotland and reported average values of 63.4 ± 5.6 mL·kg

−1·min

−1.

Other studies have reported lower values than those found in the present work for youth soccer players. Sperlich et al. [22] measured

O

2max in nine German soccer players and reported average values of 55.1 ± 4.9 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. Sporis et al. [23] measured fourteen Croatian soccer players and reported average values of 57.9 ± 4.7 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. Gómez-Piqueras et al. [

6] evaluated three categories of Spanish soccer players aged 15 to 17 years and reported average values of 56.0 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. Vänttinen et al. [24] measured three youth categories in Finnish soccer and reported average values of 52.3 ± 3.1, 53.1 ± 3.0, and 55.0 ± 3.9 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. Wong et al. [25] measured forty-six Chinese soccer players and reported average values of 54.9 ± 0.9 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. The only Argentine study [

14] reported average values of 49.8 ± 7.4 and 53.0 ± 5.5 mL·kg

−1·min

−1. As can be seen, the values found are like or higher than those reported in other leagues. However, none of the cited studies measured

O

2max in an ecological condition, i.e., on-field. Another contribution of this current on-field approach was the analysis of ventilatory thresholds (VT1 and VT2) in this population (youth soccer players), which were assessed on-field, which is scarce in the literature. In fact, we are not similar studies in youth soccer players.

One important reason for on-field evaluations is that certain physiological variables respond differently in the field compared to a treadmill. Although

O

2max does not differ between treadmill and field conditions in adults [

15], the v

O

2max is affected when comparing treadmill versus field conditions [

8]. Additionally, ventilatory thresholds and respective velocities may differ between the two environments [

7,

8]. Currently, there are no studies in children and youth that compare physiological responses on a treadmill (laboratory) versus the field. This makes comparison with other studies challenging. Although young athletes train and compete on the field, making it important to assess physiological responses in that setting, most sports centers in Argentina lack portable analyzers.

Thus, the most cost-effective way to study cardiopulmonary behavior in youth athletes is by measuring the final velocity achieved in an indirect field test. The most used test, due to its validity, reliability, safety, and sensitivity, is the 20m-SRT [

16]. This is the only aerobic test with international standards for global comparisons [25]. In Argentina, there is scientific evidence using the 20m-SRT indirectly in school populations [26,27]. However, until the present study, no direct

O

2max measurements during the 20m-SRT had been conducted in our country. The aerobic performance level of the Argentine soccer players in this study was above the 80

th percentile when compared with international standards [28] or national data [26,27]. It is important to note that the reference tables were created in a school setting. Therefore, it would be valuable in the future to establish aerobic performance norms for youth soccer players in the AFA (Argentine Football Association).

The high

O

2max values found may be due to several factors. Typically, in AFAs’ clubs, players are selected at early ages through a series of ball-focused tests, choosing those who perform best during gameplay. Subsequently, they are exposed to three weekly sessions of high-intensity exercise. It is well reported that high-intensity training produces significant improvements in

O

2max [

4,

10] Weekend matches also present a significant workload (external and internal). It is important to be aware that the same field dimensions of adults are used at these categories, i.e., considering that the playing field is the same as that for adults, and the stride length is shorter the younger the age, they end up taking a greater number of steps. There is a higher exertion level. Castagna et al. monitored soccer players with an average age of 11 years during competitive matches and found they covered an average of 6175 m per match [29]. Algroy et al. (2021) monitored 14-year-old soccer players in 23 official Norwegian league matches and found they covered an average of 7645 meters [30]. Bucheitt et al. (2010) measured players from six youth categories and found they covered between 6549 meters (13 years) and 8707 meters (18 years) [31]. The high

O

2max values obtained can be explained by the weekly training stimuli and the demands of competition.

We acknowledge some shortcomings and potential limitations in our study. A small sample size is typical in research involving athletes of this caliber, compounded by the complexities of the sports calendar and the use of portable gas analyzers in the field. Nonetheless, the results obtained provide a significant contribution to pediatric medicine, physical education, and sports science.

The 20m-SRT is the most widely used field test globally. If a gas analyzer is not available, the alternative is to identify test velocity as a performance indicator. If the club has a wearable gas analyzer with oxygen and carbon dioxide cells inside (breath-by-breath or mix-chamber mode), the staff can apply the 20m-SRT to measure performance with cardiopulmonary responses of players during on-field test.

5. Conclusions

We reported the cardiopulmonary fitness of Argentine youth soccer players, which exceeds those reported in other related studies, but comparable to those found in soccer players from the Argentine first division. Youth Argentine soccer players exhibit similar traits to professional athletes, highlighting their potential for high performance. Support staff, fitness or health professionals, and researchers can now compare cardiopulmonary differences between Argentine youth soccer players and other populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.B., G.C.G. and R.Z.; methodology, M.F.B., and R.Z.; validation, M.F.B., and R.Z.; formal analysis, M.F.B., and R.Z.; investigation, M.F.B., G.C.G., C.R.A., M.D.S., J.D.S and R.Z; resources, M.F.B.; data curation, M.F.B. and R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.B., G.C.G., J.A.R.S and R.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.F.B., G.C.G., J.A.R.S and R.Z.; visualization, J.A.R.S and R.Z.; supervision, R.Z.; project administration, M.F.B., and R.Z.; funding acquisition, J.A.R.S and R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

R.Z. was supported by The Research Center in Physical Activity, Health and Leisure (CIAFEL), Faculty of Sport, University of Porto (FADEUP), which is part of the Laboratory for Integrative and Translational Research in Population Health (ITR); both are funded by the Fundação Para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT; grants UIDB/00617/2020

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00617/2020; UIDP/00617/2020

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/00617/2020 and LA/P/0064/2020, respectively).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee while adhering to Resolution 1480/11 of the Ministry of Public Health of Argentina.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are only available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of the study participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Herdy AH, Ritt LE, Stein R, Araújo CG, Milani M, Meneghelo RS, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise test: background, applicability and interpretation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;107:467-81.

- van der Steeg GE, Takken T. Reference values for maximum oxygen uptake relative to body mass in Dutch/Flemish subjects aged 6-65 years: the LowLands Fitness Registry. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021;121(4):1189-1196. [CrossRef]

- Paffenbarger RS, Hale WE. Work activity and coronary heart mortality. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(11):545-550. [CrossRef]

- Helgerud J, Engen LC, Wisloff U, Hoff J. Aerobic endurance training improves soccer performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1925-31. [CrossRef]

- Chamari K, Hachana Y, Ahmed YB, et al. Field and laboratory testing in young elite soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(2):191-196. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Piqueras P, Malavés, RA, y López VF. (2010).Seguimiento longitudinal de la evolución en la condición aeróbica en jóvenes futbolistas. Apunts Med Esport, 45(168), 227-234. [CrossRef]

- Cappa DF, García GC, Secchi JD, Maddigan ME. The relationship between an athlete's maximal aerobic speed determined in a laboratory and their final speed reached during a field test (UNCa Test). J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2014;54(4):424-431.

- Bruzzesse MF, Bazan NE, Echandia NA, Vilarino LG, Tinti HA y García GC. Evaluación de jugadores argentinos en futbol profesional utilizando el UNCa test. Arch Med Deporte 2021;38:327-31.

- Amedro P, Matecki S, Pereira Dos Santos T, Guillaumont S, Rhodes J, Yin SM, Hager A, et al. Reference Values of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test Parameters in the Contemporary Paediatric Population. Sports Med Open. 2023;9(1):68. [CrossRef]

- Baquet G, Berthoin S, Dupont G, Blondel N, Fabre C, y van Praagh E. Effects of high intensity intermittent training on peak VO2 in prepubertal children. Int J Sports Med. 2002;23(6):439-444. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Lechuga J, Muros Molina JJ, Morente Sánchez J, Sánchez Muñoz C, Femia Marzo P, Zabala Díaz M. Efecto de un programa de entrenamiento aeróbico de 8 semanas durante las clases de educación física en adolescentes. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(3):747-754. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz JR, Ramirez-Lechuga J, Ortega FB, Castro-Piñero J, Benitez JM, Arauzo-Azofra A, et al. Artificial neural network-based equation for estimating VO2max from the 20 m shuttle run test in adolescents. Artif Intell Med. 2008;44(3):233-245. [CrossRef]

- Bruzzesse MF, Bazan NE, Laiño F, Santa María C. Functional VO2 considerations on young tennis players. Journal of Medicien and Science in Tennis. 2016;21:19-23.

- Leveroni AF, Abella IT, Pintos LF, y Coronel AR. Medición del consumo de oxígeno durnate una prueba ergométrica en futbolistas infantiles. Rev Hosp Niños (B. Aires), 2017;59(266):171-76.

- Meyer T, Welter JP, Scharhag J, Kindermann W. Maximal oxygen uptake during field running does not exceed that measured during treadmill exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;88(4-5):387-389. [CrossRef]

- García GC, y Secchi JD. Test de ida y vuelta en 20 metros con etapas de 1 minuto. Una idea original que perdura hace 30 años. Apunts Med Esport. 2014;49:93-103. [CrossRef]

- Malina RM, Kozieł SM, Králik M, Chrzanowska M, Suder A. Prediction of maturity offset and age at peak height velocity in a longitudinal series of boys and girls. Am J Hum Biol. 2021;33(6):e23551. [CrossRef]

- Léger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6(2):93-101. [CrossRef]

- Gaskill SE, Ruby BC, Walker AJ, Sanchez OA, Serfass RC, Leon AS. Validity and reliability of combining three methods to determine ventilatory threshold. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1841-1848. [CrossRef]

- Chamari K, Hachana Y, Kaouech F, Jeddi R, Moussa-Chamari I, Wisløff U. Endurance training and testing with the ball in young elite soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2005 Jan;39(1):24-8. [CrossRef]

- McMillan K, Helgerud J, Macdonald R, Hoff J. Physiological adaptations to soccer specific endurance training in professional youth soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(5):273-277. [CrossRef]

- Sperlich B, De Marées M, Koehler K, Linville J, Holmberg HC, Mester J. Effects of 5 weeks of high-intensity interval training vs. volume training in 14-year-old soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(5):1271-1278. [CrossRef]

- Sporis G, Ruzic L, Leko G. Effects of a new experimental training program on VO2max and running performance. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2008;48(2):158-165.

- Vänttinen T, Blomqvist M, Nyman K, Häkkinen K. Changes in body composition, hormonal status, and physical fitness in 11-, 13-, and 15-year-old Finnish regional youth soccer players during a two-year follow-up. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(12):3342-3351. [CrossRef]

- Wong del P, Carling C, Chaouachi A, Dellal A, Castagna C, Chamari K, Behm DG. Estimation of oxygen uptake from heart rate and ratings of perceived exertion in young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(7):1983-1988. [CrossRef]

- Secchi JD, García GC, España-Romero V, y Castro-Piñero J. Physical fitness and future cardiovascular risk in argentine children and adolescents: an introduction to the ALPHA test battery. Arch Argen Pediatr. 2014;112:132–140.

- Santander MD, García GC, Secchi JD, Zuñiga M, Gutiérrez M, Salas N, et al. Valores normativos de condición física en escolares argentinos de la provincia de Neuquén: estudio Plan de Evaluación de la Condición Física. Arch Argen Pediatr. 2019;117:e568–e575.

- Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay MS, et al. International normative 20 m shuttle run values from 1 142 026 children and youth representing 50 countries. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(21):1545-1554. [CrossRef]

- Castagna C, D'Ottavio S, Abt G. Activity profile of young soccer players during actual match play. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17(4):775-780. [CrossRef]

- Algrøy EA, Hetlelid KJ, Seiler S, Stray Pedersen JI. Quantifying training intensity distribution in a group of Norwegian professional soccer players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6(1):70-81. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit M, Mendez-Villanueva A, Simpson BM, Bourdon PC. Match running performance and fitness in youth soccer. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(11):818-825 . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).