1. Introduction

The rapid development of internet technology and the widespread use of social media platforms have profoundly impacted language use and evolution. Because of the country's current political and social development, English has become incredibly popular in modern China (Bolton & Graddol, 2012). In Chinese schools, bilingual education with English as the primary language of instruction is becoming increasingly popular (Wei, 2013). As a result, a growing percentage of Chinese people are eager to study and communicate in English. Youths have played a significant role in the widespread usage of "Internet English" in social media workspaces. In today's mainland China, the most notable intranational use of English is the practice of "English mixing" on various domestic social networking sites (Zhang, 2012).

Among Chinese-speaking netizens, the term “Emo”has become widespread — with interesting semantic changes. Chinese internet language has taken “Emo”— which originally comes from the English word "emotional" and often connotes the emo music subculture — into entirely new directions, far removed from its original context.

The purpose of this study is to describe and explain the process which Chinese internet language develops a more Metonymicalical meaning of “Emo”, and uncover sunstantial cultural and social influences on this linguistic phenomenon. Through analyzing the typical semantic extension and Metonymicalical uses of “Emo”, this chapter explores how such a term partially reflects, shapes, as well as embodies broad-based emotional expressions and social experiences among Chinese netizens.

The following questions inform the research:

1. Semantically, What Makes the Most Popular Extensions of “Emo”in Chinese Internet Slang Essentially The Same?

2. What are some of the more common examples of metonymy using “Emo”?

3. In what way do the manifold extensions in meaning and metonymic applications indicate cultural and social tendencies?

For several reasons, it's important to understand why and how “Emo”in Chinese internet language came about. It is suggestive of the fluidity with which language functions on digital landscapes and how internet users co-opt linguistic resources to articulate their lived realities. Next, it provides an avenue into the emotional life of Chinese netizens, particularly vernacular (and especially younger) ways they conceive emotions and express them. Most importantly, it participates in the generality of internet linguistics and cognitive linguistics by examining how metonymy theory can be applied to understand emerging language patterns in online communication.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Semantic Change and Extension

The change of meaning: a basic type of linguistic evolution That words in the English vocabulary can have their meanings shift is no secret; such permutation, called semantic change (or simply sematic), are as fundamental to language development as vowels and consonants. A later and more comprehensive analysis was provided by Blank (1999), in which he also described the following types of semantic change: widening, narrowing, Metonymicalical extension or shift; metonymy etc. In the case of internet, these can be very speedy because of the nature that online conversation is a lot more spontaneous in its creativity by participants (Crystal 2006).

Invited Inferencing Theory of Semantic Change Traugott and Dasher (2001) developed the Invited Inferencing theory of semantic change, focusing on the role that pragmatic factors play in leading to meaning change according to speaker-listener interactions. And this is a theory which clearly strikes at the heart of internet language, where feedback and rapid formation of meaning are key.

More and more attention has been paid to semasiological extension of internet language. Zappavigna (2012) discusses semantic extension of hashtags on Twitter as a process that maps out novel meanings and creates social identifications. Similarly, McCallum et al. Investigates the semantic advancement of emojis in digital transmission, which displays that these pictorial signs are charged with further features during use.

In the Chinese context, Tao (2017) investigates and analyses the semantic growth of neologisms in an effort to present how new terms can demonstrate prevailing social attitudes and national values. This is useful as a scheme for soberingly exploring how loanwords like “Emo”could be domesticated and/or transcultured in Chinese digital discourse.

2.2. Metonymy Theory

One of the approaches, the Cognitive Metonymy Theory (Radden and Kövecses 1999), takes metonmy as basic cognitive mechanisms to form our world sense,rather than just a linguistic devises. This theory explains how we come to know and experience abstract ideas as more concrete-like, directly connected concepts. This has been a popular technique in the language and cognition work, including within digital contexts.

Littlemore (2015) builds on the cognitive metonymy theory to examine how culture can impact a conceptualization of Metonymicals as well as neural representation. This is extremely significant, as our work looks at the cultural and social implications that accompany this metonymical use of “Emo”in the context of a different country: China.

In recent work on the theory of metonymy, attention has been drawn precisely to its concrete and dynamic nature as opposed to other forms (on which more below) of Metonymicalical thinking. Panther and Thornburg (2007) suggest amending such a mode of analysis to give due consideration βothto the contextual, multimodal factors shaping metonymical expressions and furthermore supposedly metonomy's corresponding affective dimensions. Such a perspective is especially accurate in the context of internet language, as among all things that features heavily on web contexts, and multimodality is constantly at play.

In the digital communication domain, Yus (2019) uses cognitive metonymy theory to examine internet memes proving that these pieces of information require more complex types of metonymical mappings than pictures from physical reality. Such revelations about how metonymy may work in multimodal digital spaces are consonant with the sort of insight we will find to be useful when studying “Emo”on several online platforms.

2.3. Internet Linguistics

Crystal (2006), for instance, has made a substantial contribution to the emerging field linguistics in his study of internet language. Within this category, research has examined the emergence of new linguistic forms online (as in my own work), as well as how technology can affect language use and more sociolinguistic perspectives on Internet Language.

Herring and Androutsopoulos (2015) offer a review of computer-mediated discourse analysis, stressing that the study of language on the internet should bear in mind technological factors as well as social-cultural ones. Their work will inspire our application of this to analysis “Emo”in Chinese social media environ- ments.

Even under the restrictions of Chinese vAuthor, Gao (2012) concludes thatarge internet language such as it allows extraordinary creativity and playfulness which in turn is a mirror to social changes. The study adds important detail to the language used in “Emo”into the linguistic ecosystem.

Recent studies have aimed to explore the influence of social media platforms in language usage. Zhang, Q., & Cassany Viladomat, D. (2019) — Offers and affordances in a Chinese language ecology: A special take on the role of WeChat for linguistic practices Zhang and her colleagues explore how features specific to offline forums encourage language use among particular users; they illustrate site-specific platform dynamics that fuel new possibilities each within their notion of available lexicogrammars This insight is crucial to understanding how the technical setting of Chinese social media could shape the life cycle for terms such as "Emo."

2.4. Emotion and Language in Chinese Context

For both the semantic extension and metonymical usage of “Emo”, it is necessary to take into account the cultural context in which emotions are expressed within Chinese society as a mode or instance of communication. Ye (2004) provides an analysis of cultural models of emotion in Chinese and elaborates on traditional concepts as well as social norms that dictate how emotions can be expressed.

Li et al. (2015) provided a comprehensive review in the own language and culture, aiming at showing how linguistic mechanism affects emotion as mediated by cultural value. The work of Li et al. reminds us to consider both universal and culture-specific facets of emotion expression;

Ge and Herring (2018) are also interested in internet language, examining the use of emoji and stickers to speak about affective meaning-work within Chinese social media interaction. Their work reveals more about the wider state of emotional expression in Chinese digital communication.

Chen et al. (2018) identify some of the properties of internet language in emotional disclosure which opened up new possibilities for representing and negotiating emotions among Chinese social media users.

2.5. Research on “Emo”in Chinese Context

Although the semantic collocation and Metonymical of it have been a popular subject related to Chinese internet language,2 academic research on this kind is quite rare. Zhang and Wang (2021) only give a brief description of → “Emo”in their study on the internet slang among Chinese netizens with no discussion about its Metonymicalical meanings or extensions.

Liu (2020) mentions Emo in passing when discussing English loanwords among other internet memes, acknowledging that it is “extremely popular on the Chinese Internet” which seems more accurate than not for current usage even if without its specific deeper layer of meaning or longer cultural background.

Clearly, a review of existing academic studies and literature on Emo in Chinese internet language is sorely needed. Nonetheless, there is a mounting literature on related phenomena that suggests potential methodological and theoretical considerations:

In addition to the example from Buldorini, one of our favorites is Fang and Yue (2016), a study on how even semantically new terms like “给力” geili can quickly change in meaning after they begin to be adopted by other speakers – following just 5 years since its diffusion.

Drawing on a study by Wu and Zhu (2019) about Metonymicalical expressions in Chinese social media writing regarding depression, the article uncovers perceptions of emotional states and their dissemination over digital platforms.

Li et al. Their research (2022) into code-switching and loanwords on Chinese social media provides a further insight to the incorporation process foreign terms undergo in order for them to be part of contemporary internet language specific only within the context of China.

Despite not being explicitly about “Emo”, these studies offer important methodological guidance as well as useful contextual reference for our research.

2.6. Gaps in the Literature and Research Contribution

A review of the literature shows that even if there is plenty of research on semantic change and Metonymical from mainstream linguistics, few studies have explored these phenomena in a context which changes so fast as internet language (language used online) — especially for non-English languages. While research on Chinese internet language has been rich, much of it concentrates upon native terms or the general phenomenon of loanwords; there is little detailed study on how the semantic meaning behind specific borrowed terms like “Emo”have developed.Our study aims to contribute to these areas by providing a comprehensive analysis of the semantic extension and Metonymicalical usage of “Emo”in Chinese internet language. By doing so, we hope to not only shed light on this specific linguistic phenomenon but also to contribute to broader discussions about language change in digital environments, the expression of emotion in Chinese culture, and the methodological approaches for studying internet language.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

We use a mixed-methods approach in this study, which utilizes quantitative analysis over an extensive body of social media data along with examples that were examined qualitatively for detail. This design enables us to analyze overarching trends in the utilizations of “Emo”as well as fine-grain studyings whose subject is its semantic extensions and Metonymicalical uses. The

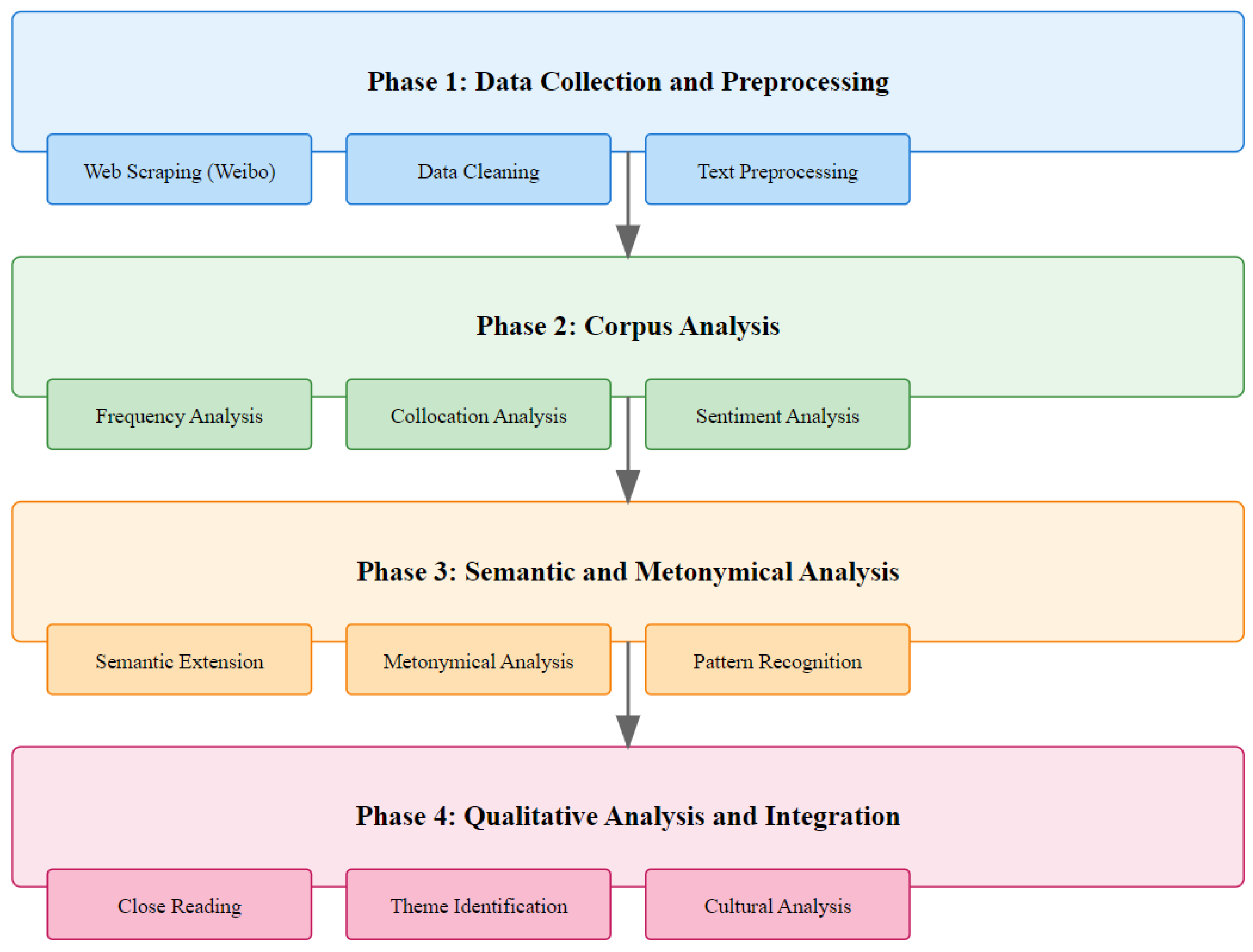

Figure 1 displayed below is the technical roadmap for this article.

3.2. Data Collection

The data in this study was collected on several of the most popular Chinese social media platforms including-Weibo using web scraping. Data collection was done for post and comment that mentioned the term “Emo”(published in both “伊莫“ of Chinese characters and Latin script) from June 2024 to October 2024.

3.2.1. Web Scraping Process

Using the Scraper we wrote a python script and scraped the data from social media platforms. For each post or comment with “Emo”in it, the script was supposed to collect:

This included the creation of a Python script that would scrape social media posts and comments containing "Emo. The script was developed to scrape the entire post or comment text along with its timestamp and user data (anonymized). It also had tracking metrics on engagement such as likes, shares and comments — while providing metadata monitoring for platforms like Weibo hashtags. Data was collected in accordance with the terms of service from both platforms by strictly adhering to ethical guidelines. For privacy reasons, all unique data was hashed in a secure manner at the preprocessing stage.

3.2.2. Data Cleaning and Preprocessing

After data collection, a number of cleaning and preprocessing steps took place. That meant cutting out repeated entries to streamline local data and filtering for extraneous content (i.e. ads). Due to the variety of languages & text formats, it is necessary that the data be handled carefully — notably in identifying Traditional versus Simplified Chinese. For text tokenization, we used the jieba library with removing stop words and punctuation to make data more clear and meaningful. In this way, the data was well-prepared ready for a more profound analysis leading to only validity and reliability of its source needed in stages 3 and 4.

Compliance with the respective terms of service and collection of publicly available data were consistent in order to ensure that we adhered by ethical data capturing. All identifying data was hashed during the preprocessing process so that user privacy is safe.

3.3. Corpus Analysis

The cleaned and preprocessed data formed our research corpus. The goal with the frequency analysis was to identify recurring patterns as they relate to “Emo”or its derivatives throughout our data set. For example, one way to better gauge this is evaluating how often we see that word across the corpus (i.e. overall presence) at times you might refer to it as prevalence …etc.... We also looked at temporal patterns to see whether “Emo”use was creating any news or seasonal buzz lines over time. The most important part of this analysis was tracking common phrases and words that appeared together with “Emo,” so we could start to see the linguistic framework around which these conversations were occurring. Taken altogether, these findings constructed a layered sense of the importance and development that “Emo”held within this data set.

3.3.2. Collocation Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the semantic meaning behind “Emo”, we performed collocation analysis. More specifically, the process sought to examine words and phrases that often occurred within x-words of “Emo”from inside the corpus systematically. In identifying these neighboring terms, we found 2 highly prevalent word usage networks to help learning about the context in which “Emo”is grounded in different writings. This analysis not only brought to light the top linguistic collocates but also the wider semantic orbit in which “Emo”resides, illuminating how its meaning emanated from interacting elements of words/collocations. The results from this collocation analysis provide new insight into when and where “Emo”indicates emotional, referential or subcultural meaning.

3.3.3. Sentiment Analysis

We performed a manual sentiment analysis to quantify the emotional valence of posts with 'Emo'. Using only our human skills (a tedious process), we read each post, interpreted the emotion written out by authors. We also used this hands-on approach to figure out if the post was positive, negative or neutral just based on our own knowledge of language and context.

3.4. Semantic and Metonymical Analysis

Based on the initial findings along with other ideas, we further expanded and continued our comprehensive semantic and metonymical analysis in order to get a better sense of what “Emo”actually refers to across many contexts. In short, close reading revealed that “Emo”works off the literal meaning of this genre classification but also for much broader concrete and metaphorical associations. Using semantic analysis, we looked at the different nuances of “Emo”based on its collocates & surrounding discourse and tried to map out an interpretive spectrum.

At the same time, using this metonymical analysis we also were able to code instances where “Emo”was being used as a symbol for other broad concepts/emotions/sub-cultural references that went beyond simply qualifying how someone felt and instead functioned as shorthand describing something wider than our phenomenon of interest. Examining these patterns, we discovered that “Emo”functions to confer both literal and figurative significance in communication data; and as such were able to reveal the ways this affected emotional discourse configuration within user profiles. Combining these two angles — the semantic and the metonymical — provided a richer picture of how this particular term is used, as well as on some forms of cultural or emotional terrains.

3.4.1. Semantic Extension Analysis

We systematically built a 'mind map' about various forms uses of “Emo”are contained in the corpus and based on semantic content we grouped instances together. This well-defined classification allowed us to find important patterns when the meaning of the term went beyond its base emergence. Once tied to a certain subculture that expressed itself through emotions, “Emo”in library catalogues eventually came to represent just about any emotion or emotional reaction. In a later passage, they would write "Emo is sometimes used in interpersonal contexts to serve as an abbreviation for emotional or overemotional." This shift reflects the change that happened with how Emo felt and what sparked it; whereas before Emo was associated more often than not exclusively to subcultural identity. By looking at the contexts where “Emo”popped up, we observed an emerging usage that reflected more than emotions originally referred to by that word.

3.4.2. Metonymical Identification and Analysis

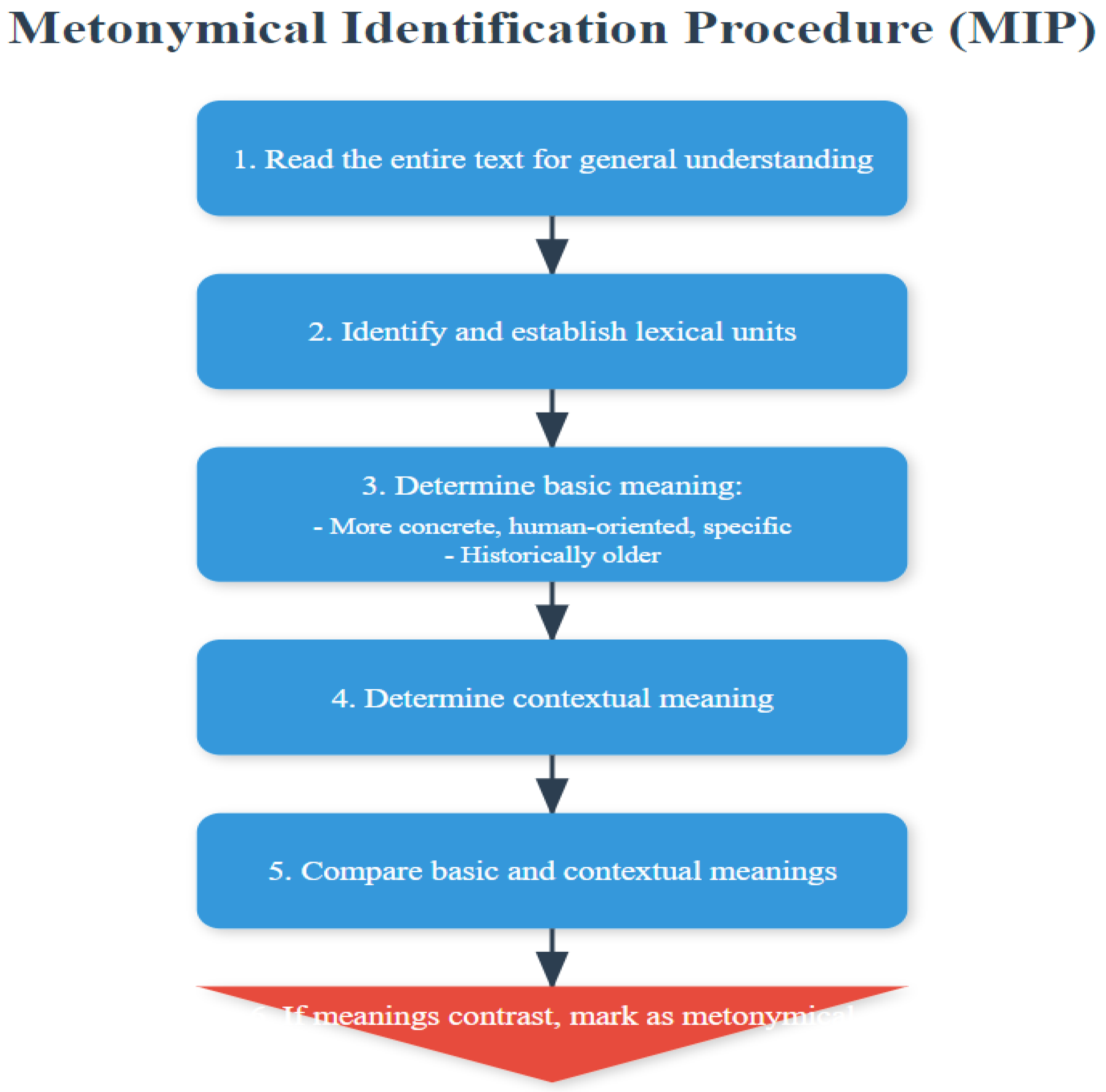

Using the Pragglejaz Group (2007) Metonymical Identification Procedure (MIP )[

Figure 2], allows us to identify metonymic uses of “Emo”in our corpus. The

Figure 2 displays the six primary steps in top-down linear process for Metaphorical Identification Procedure (MIP): from reading whole text to comprehend general understanding, then discovering and defining lexical units inside it, then analyzing the basic meanings of these lexical units, paying special attention to their generally non-specialised and concrete meaning , as well as historically older ones. The fourth stage deals with the determination of these lexical units in terms of contexts, while the fifth step is concern to differentiation between basic meaning and contextual meanings. If these two senses are antonyms, but not in the logic connected comparing way then we marked this lexical unit as metaphorical.

Figure 2 shows the progression from the first five analytical steps, as blue rectangular boxes connected with arrows, to a red triangle depicting a final decision point.

Drawing on the conceptual theory of metonymy provided by Lakoff & Johnson (1980), we then investigated how 'Emo' is metaphorically realized in its emergent, defining writing and recordings(estimations). It outlined a theory and comprehensive model for understanding how metonymy functions in language, demonstrating the manner in which part of a concept can signify its whole or one experience stand as illustration of larger emotive or sociocultural realms. In deploying this conceptual tactic, we probed the way that “Emo”does more work than simply describe an emotional body.

3.5. Qualitative Analysis

In addition to this quantitative analysis, we performed a qualitative review of some data points (post and comment content) From this, we saw which kinds of responses appeared again in other places and started to identify recurring themes & patterns — for example how 'Emo' was the most common way people expressed feelings like anger or sadness. Next, we considered the importance of context in determining what “Emo”meant — one definition was going to mean different things on a platform vs. another conversation etc …. It was also through this method that we were able to conceive of “Emo”not as simply a word but as an adjustable term swayed by social discourse.

3.6. Limitations

We note the limitations of our methodology. The information is based on public posts on the platforms it scraped, and does not apply to private or ephemeral communications (i.e. you probably won't see secrets revealed by encrypted end-to-end messaging apps like Signal). However, web scraping may be less complete or miss relevant data that is not available on the platforms. The analysis is centered on the use of written text, and does not entail other non-text forms or fields within communication (visuals like images, video).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Frequency and Distribution of “Emo”Usage

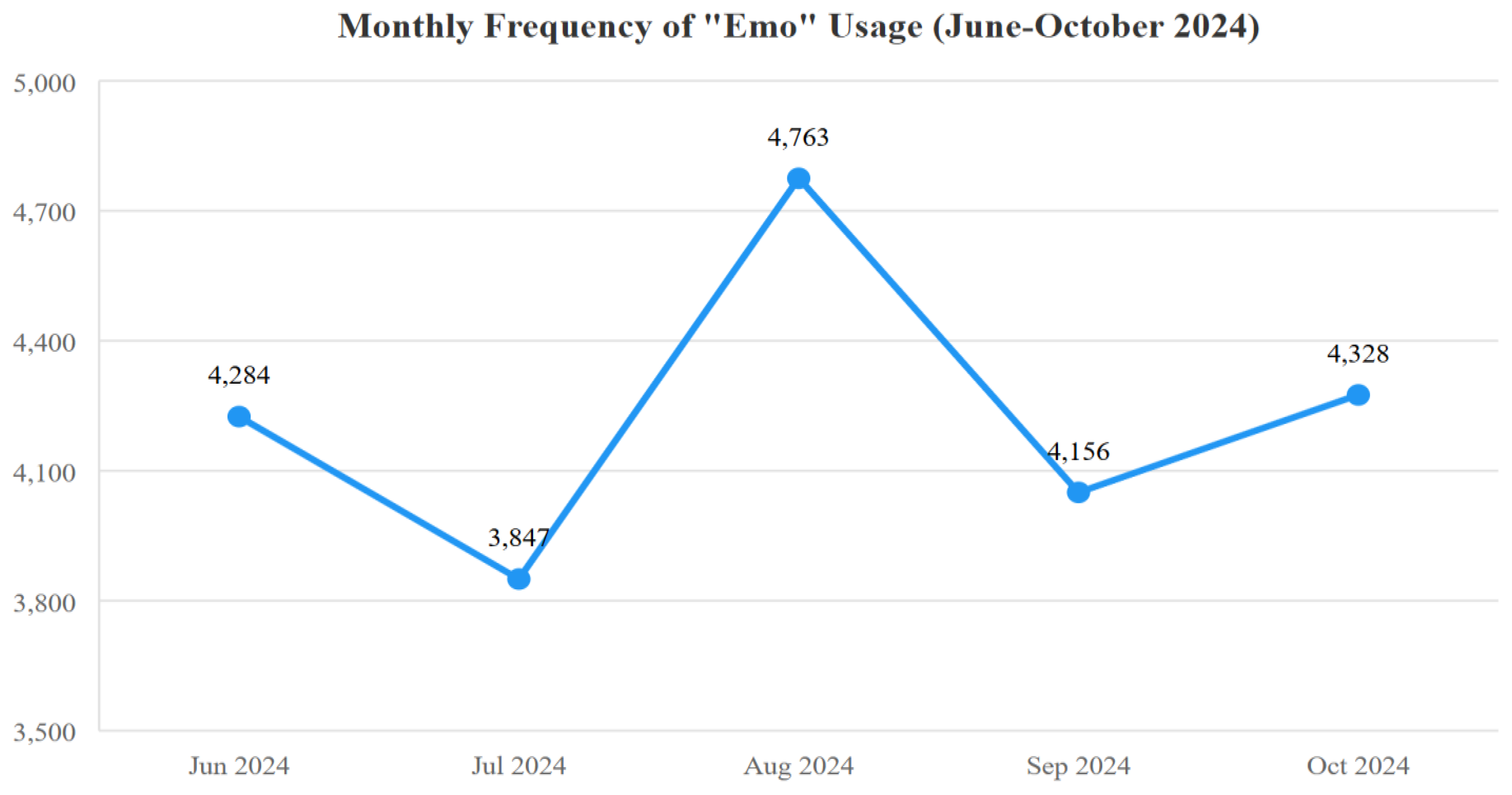

We found that the timeline of usage patterns in “Emo”on Chinese social media platforms fluctuated from June 2024 to October 2024. This term appeared in an additional 32,110 unique posts and comments over the time period with a clear seasonal pattern as mentioned above along event-driven spikes. From there, the distribution took off with 4284 blogposts in June of 2024 — as one might expect around time for summer holidays and more student user activity. There was a small drop off in July to 3,847 (likely due to varied summer activities stealing focus from users). The peak came in August, with 4,763 posts published (not accounting for double counting), when young users return to school and are generally more expressive. This declined to 4,156 posts in September as schools and routines starting coming back on track but rebounded slightly to reach 4.328 in October during the National Day holiday period. The remaining 10,732 posts were integrated with platform specific features such as comments, shares and interactive responses.

The monthly frequency pattern across platforms is visualized in

Figure 3, and indicates that use of “Emo”posting fluctuates over time. The visualisation shows the quantitative distribution but also uncovers (quasi-) periodic patterns that relate to major historical and societal epochs as well as seasonal events. The in-depth frequency analysis can help to reveal the semantic extension as well intersecting usage patterns of “Emo”in Chinese internet language, so we could infer from changes whether or not each occurs either under specific contexts and changing functions.

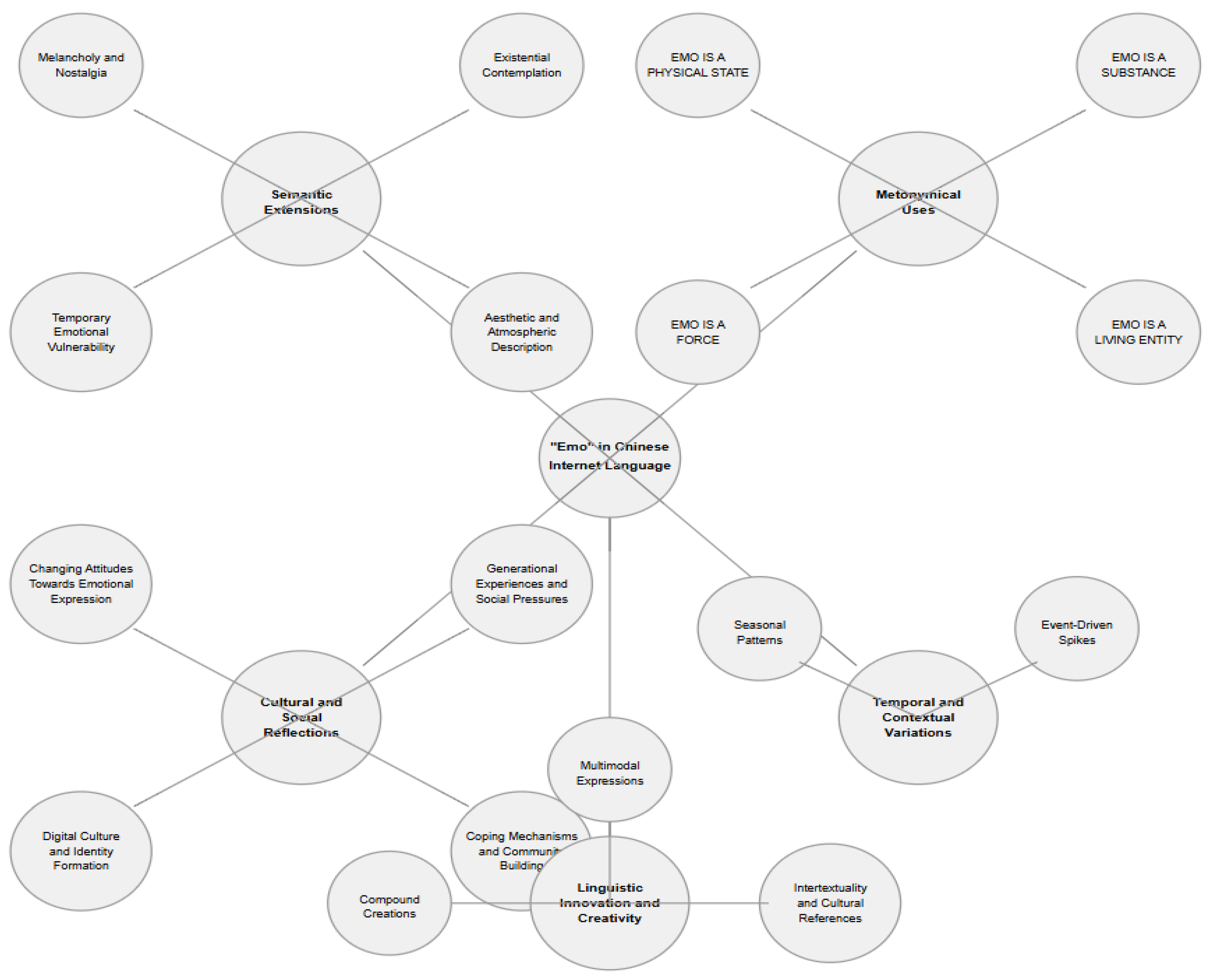

Figure 4 of mind map provides a clear, visually appealing representation of the functions and sub-functions of “Emo”in Chinese Internet Language.

The data displays that “Emo”is not only an emotional term but has gone beyond its original meaning and functions as a flexible word in Chinese online posts, synchronized with both social time flow and cultural events. The presence of a relatively constant baseline rate, punctuated by contextually driven increases, suggests that the term has been embedded into everyday digital vernacular but is still responsive to temporal and social considerations.

4.2. Semantic Extensions of “Emo”

In the process of our semantic analysis, we discovered a few different types were being used to extend “Emo”in Chinese internet language. These extensions illustrate that the term has come to refer not only to a mainstreaming of emo culture itself but also to an increasing diversification and ultra violence of emotional experiences.

4.2.1. Melancholy and Nostalgia

The semantic extension of “Emo”most frequently refers to melancholia, often accompanied by nostalgia as well. In this context, “Emo”simply means a reflective sadness about the past or things you cannot change. For example:> "看到高中同学的合照,突然有点emo了。" (Seeing a photo of high school classmates, I suddenly felt a bit emo.) This usage occupies approximately 37% of the occurrences in our corpus. Some typical examples of the original blog posts display below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 看到高中同学的合照,突然有点emo了。 |

Seeing a photo of high school classmates, I suddenly felt a bit emo. |

| 我发现我一听小马丁就dp…是他带给我太多快乐,以至于平时一听到就会trigger吗,在家好好的,放个歌给我搞emo了好难过😫 |

I find that whenever I listen to Martin Garrix, I become emotional... Has he brought me so much joy that it triggers me whenever I hear it? I was fine at home, and then a song made me feel emo and so sad. |

| 从来不删微信好友啥的 每次都是点进去朋友圈看看有没有横线 再点一下转账看看还能不能看到名字 都没有就会心灰意冷地再把这个人删掉 以前每次遇到都会自己又emo上好一阵子 思考自己做错了什么 |

I never delete WeChat friends. Every time, I check their moments to see if there's a line, then try to transfer money to see if I can still see their name. If not, I'll feel disheartened and delete them. In the past, every time I encountered this, I would feel emo for a while, thinking about what I did wrong. |

| 一到晚上眼泪特别多,其实根本就没有emo,就是刷手机看这看那的共情太多了,啥小事都要共情一下,跟有病似的 眼睛都要给我哭小了,这本来眼睛就小 |

I shed a lot of tears at night, but I'm not really emo. It's just that I empathize too much while browsing my phone, empathizing with every little thing as if there's something wrong with me. My eyes are going to cry smaller, and they were already small. |

| 翻看以前的朋友圈 我发现我已经很久很久很久没有emo了 和cyc在一起之后我幸福的好稳定 |

Looking through my old moments, I found that I haven't been emo for a very, very long time. My happiness has been very stable since I've been with cyc. |

| 每到晚上就想很多,emo,矫情,好想撒泼打滚,什么都觉得烦。 |

Every night, I think a lot, feel emo, melodramatic, and I just want to roll around and throw a tantrum. I find everything annoying. |

4.2.2. Existential Contemplation

Similarly important to how “Emo”has morphed into a means of characterizing periods of existential introspection or questioning. And typically we use this phrase while trying to articulate confusion of life, authenticity or those existential questions everyone has. These things are relatively consistent and represent 28% of the usage in this corpus. Some typical examples of the original blog posts display below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 然而因为性格还是那个性格,55还是那个55,在漫长的长达两千多年的生命里,不断面临友人和亲近之人的死亡,每一次放下心结试图和其他 |

Yet, because the personality remains the same, 55 is still that 55, in the long life span of over two thousand years, constantly facing the death of friends and close ones, each time letting go of the heart knot and trying to be with others |

| 夜里的我:啊,EMO,啊,做这些的意义在哪里呢,啊,醒醒吧还是去努力挣钱吧。 |

Myself at night: Ah, EMO, where is the meaning in doing all this? Wake up and go work hard to make money. |

| 面对同样的信息,不同人的选择还是挺有趣的~我叔叔觉得我emo,给我送来了两本他巨喜欢的王阳明~ |

It's quite interesting how different people make different choices when faced with the same information~My uncle thinks I'm emo and sent me two books by Wang Yangming, whom he really likes~ |

| 为了避免往年年末的忙碌今年提前加快了一些节奏有些压力但又不至于焦虑是自己比较满意的样子加上最近很是舒爽的户外大概也就不那么容易emo了 |

To avoid the busyness of previous years, I've accelerated the pace a bit in advance this year. There's some pressure, but not enough to cause anxiety. It's a state I'm quite satisfied with. Plus, the recent outdoor activities have been quite refreshing, so I'm probably not as likely to be emo. |

4.2.3. Temporary Emotional Vulnerability

Emo is also often used to describe a general state of mild depression, but does not necessarily rule out examining deep or sensitive emotions (as Emotion Core Technicans would claim), such as in 'that's so emo' when sweeping over minor difficulties. This user is more casual and laughs at themselves. This extension represented about 22% of all occurrences.Some typical examples of the original blog posts display below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 工作太累,被老板说了几句,整个人都emo了。 |

Work was so tiring, got a few words from the boss, and my whole self became emo. |

| 上6天课就会emo |

After 6 days of classes, I become emo. |

| 晒晒太阳驱除emo,我真没有面上看上去那么放松 |

Basking in the sun to dispel emo, I'm really not as relaxed as I appear to be. |

| 胃疼 睡不着 emo |

Stomachache, can't sleep, emo. |

| 为什么身边的朋友同学,突然有一天在朋友圈晒结婚证,晒娃,发自己的幸福瞬间。特别是生了娃的朋友同学,孩子才2.3个月或者刚出月子,就总是在深夜发一些emo的文案 |

Why do friends and classmates suddenly post marriage certificates, babies, and moments of their happiness on their social media? Especially those who have just given birth, when their children are only 2 or 3 months old or just out of the confinement month, they often post some emo copy in the middle of the night. |

4.2.4. Aesthetic and Atmospheric Description

Notably, “Emo”has also been used to describe certain aesthetics or manners of mood as well: This usage was relatively less frequent and only accounted for around 13% respectively in corpus. For example, “这家咖啡馆的氛围好emo,适合独自思考。” (The atmosphere of this cafe is so emo, suitable for thinking alone.) Some typical examples of the original blog posts display below. The following examples provide instances in which the word “Emo”is used to convey aesthetic qualities or environmental conditions that foster a thematic element of an evoked ladened, emotive atmosphere and introspection often synonymous with melancholy. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 晒晒太阳驱除emo,我真没有面上看上去那么放松 |

Basking in the sun to dispel emo, I'm not as relaxed as I appear to be. |

| 一到晚上眼泪特别多,其实根本就没有emo |

I shed a lot of tears at night, but I'm not really emo. |

| 阴天不能听慢歌,会emo |

Can't listen to slow songs on a cloudy day, it makes me emo. |

| 每次睡超过半小时的午觉醒来就会感觉自己是全世界最emo的人 |

Every time I wake up from a nap longer than half an hour, I feel like the most emo person in the world. |

| 阴天让人emo |

Cloudy days make me emo. |

| 秋天的雨后,这气氛太emo了 |

After the rain in autumn, the atmosphere is so emo. |

| 深夜的emo和焦虑…最近真的太不顺利了 |

Late night emo and anxiety... things have been really going wrong lately. |

4.3. Metonymicalical Uses of “Emo”

Analysis results of Metonymical uses in Chinese internet language. In this article, the Metonymicals offer a glimpse into how Chinese netizens calve and compound emotions.

4.3.1“. Emo”is a physical state

Arguably the most frequent Metonymical conceptualization of “Emo”is as a physical state where one can live, die in, and exist. Which moves the abstract emotional state to a concrete location or condition. Examples include:

“我陷入了emo的深渊。”(I've fallen into the abyss of emo.)

“终于从emo中走出来了。”(Finally walked out of the emo state.)

The metonymic usage underlines the apparent heaviness and transience of that mood, so users can publicly talk about their feelings as if they were form-fitting events. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 我陷入了emo的深渊。 |

I've fallen into the abyss of emo. |

| 终于从emo中走出来了。 |

Finally walked out of the emo state. |

| 为了避免往年年末的忙碌今年提前加快了一些节奏有些压力但又不至于焦虑是自己比较满意的样子加上最近很是舒爽的户外大概也就不那么容易emo了🤗 |

To avoid the busyness of previous years, I've accelerated the pace a bit in advance this year. There's some pressure, but not enough to cause anxiety. It's a state I'm quite satisfied with. Plus, the recent outdoor activities have been quite refreshing, so I'm probably not as likely to be emo. |

| 我今天真的好幸福,从耳机到看台,治愈了我的emo,我们下次见❤️ |

I'm really happy today, from headphones to the stands, healing my emo, see you next time ❤️ |

| 我真情实感搞冰棒球一定是我的报应,每次emo时想到这四个深处黑暗却温暖的孩子,心情就会好很多 |

My true love for ice baseball must be my retribution. Every time I think of these four children who are deep in the dark but warm when I'm emo, my mood will get much better. |

| 我回来了 今天不emo |

I'm back, not emo today. |

4.3.2“. Emo”is a substance

Another common Metonymical describes “Emo”as something that occupies a place or can be counted. This is used to allow users to say how strong or widespread their feelings are. Some examples like

“整个房间都充满了emo的气息。” (The whole room was filled with an emo atmosphere.)

“今天的emo指数爆表了。” (Today's emo index is off the charts.)

This Metonymical gives the user a much better way to express their emotional experiences in terms of intensity and how they believe it is impacting on them surroundings. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 今天的emo指数爆表了。 |

Today's emo index is off the charts. |

| 阴天不能听慢歌,会emo |

Can't listen to slow songs on a cloudy day, it makes me emo. |

| 每次睡超过半小时的午觉醒来就会感觉自己是全世界最emo的人 |

Every time I wake up from a nap longer than half an hour, I feel like the most emo person in the world. |

| 深夜的emo和焦虑…最近真的太不顺利了 |

Late night emo and anxiety... things have been really going wrong lately. |

| 我今天真的好幸福,从耳机到看台,治愈了我的emo,我们下次见❤️ |

I'm really happy today, from headphones to the stands, healing my emo, see you next time ❤️ |

| emo的goodees也太可爱了 |

The emo goodees are just too cute. |

4.3.3“. Emo”is a force

Emo also comes to be a category frequently understood as an external force that works its way on the individual. This Metonymical depicts the emotions as if they were ever wielding a weapon, hitting and attacking someone. Examples has been listed below.

“emo来袭,我措手不及。” (Emo struck, and I was caught off guard.)

“被emo的浪潮冲击。” (Struck by a wave of emo.)

This Metonymicalical usage downplays the idea one can rein in their feelings — “Emo”is instead something overpowers people, usually when they least expect it. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 张碧晨化身古希腊emo之神 |

Zhang Bichen becomes the ancient Greek god of emo. |

| 面对同样的信息,不同人的选择还是挺有趣的~我叔叔觉得我emo,给我送来了两本他巨喜欢的王阳明~ |

It's quite interesting how different people make different choices when faced with the same information~My uncle thought I was emo, so he sent me two books by Wang Yangming, whom he really likes~ |

| 为了避免往年年末的忙碌今年提前加快了一些节奏有些压力但又不至于焦虑是自己比较满意的样子加上最近很是舒爽的户外大概也就不那么容易emo了🤗 |

To avoid the busyness of previous years, I've accelerated the pace a bit in advance this year. There's some pressure, but not enough to cause anxiety. It's a state I'm quite satisfied with. Plus, the recent outdoor activities have been quite refreshing, so I'm probably not as likely to be overwhelmed by emo. |

| 我回来了 今天不emo |

I'm back, not emo today. |

4.3.4“. Emo”is a living entity

In some cases, “Emo”is personified or treated as a living entity with its own agency. This Metonymical allows users to interact with or describe their emotional state as if it were a separate being:

“我的emo又开始作祟了。” (My emo is acting up again.)

“喂饱了我的emo小怪兽。” (Fed my little emo monster.)

This personification can serve various functions, from creating humorous distance from one's feelings to expressing a sense of internal conflict or dialogue. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 我的emo又开始作祟了。 |

My emo is acting up again. |

| 我的emo小怪兽需要被关爱 |

My emo little monster needs love. |

4.4. Cultural and Social Reflections

There are several interesting cultural and social phenomena in these semantic extensions of Metonymicalical label “Emo”, all of which will help make sense out certain properties that I want to propose about Chinese internet language as a whole.

4.4.1. Changing Attitudes Towards Emotional Expression

The popularity and reinvention of “Emo”represents a changing tide around expression in Chinese culture, like how we are starting to see some change especially with the younger generations. In Chinese culture, emotional containment and social harmony are often underscored traditionally(Ye 2004). But the renewed popularity of “Emo”shows an increasing openness to recognizing and talking about Less Than Positive or uncomplicated feelings publicly.

The deployment of a playful, often self-deprecating tone in many “Emo”expressions can do some transitive labor here — as an acceptable social mechanism to grapple with this cultural shift by allowing the user to be vulnerable but maintain an air of detachment or irony. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 从来不删微信好友啥的 每次都是点进去朋友圈看看有没有横线 再点一下转账看看还能不能看到名字 都没有就会心灰意冷地再把这个人删掉 以前每次遇到都会自己又emo上好一阵子 思考自己做错了什么 |

I never delete WeChat friends. Every time, I check their moments to see if there's a line, then try to transfer money to see if I can still see their name. If not, I'll feel disheartened and delete them. In the past, every time I encountered this, I would feel emo for a while, thinking about what I did wrong. |

| 看到emo朋友圈都不敢点赞怕别人尴尬 |

I see emo moments on WeChat and dare not like them for fear of embarrassing others. |

4.4.2. Generational Experiences and Social Pressures

Those contexts in which “Emo”is usually invoked serve as a commentary on the experiences and stressors borne by web-ers, young Chinese who struggle with their economic future. This is evident in a number of examples from our corpus which pertain to work stress, academic pressure, relationship problems and fears about the future. For instance:

“加班到凌晨,看着窗外的月亮,突然emo。” (Working overtime until dawn, looking at the moon outside the window, suddenly feeling emo.)

The usage pattern shows that “Emo”is used as a clear tool for young Chinese to articulate and come into terms with the problems they are facing in an ever-changing competitive pressured society. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 每天通勤都要花两三个小时,累得没时间做自己喜欢的事,emo。 |

The daily commute takes two or three hours, I'm too tired to do things I like, feeling emo. |

| 想换个工作,但又担心找不到更好的,好纠结,emo。 |

I want to change jobs, but I'm worried I won't find a better one, I'm so torn, feeling emo. |

| 看着朋友圈里的朋友们都在晒旅游照,自己却连周末都要加班,好羡慕,emo。 |

Seeing friends in my WeChat Moments posting travel photos, and I have to work overtime even on weekends, I'm so envious, feeling emo. |

4.4.3. Digital Culture and Identity Formation

Through the development of “Emo”language such as that on Chinese internet, we are reminded of how emergent digital space helps to influence and negotiate both our own identity and peripheral formations. Chinese net-users, in taking up this term (though modifying it) are making culture digitally but also cross-culturally and even certain culturally.

The most common form of engagement with “Emo”involves personalized, performative expressions or presentations of emotional states that these participants see as aligning well with relevant online trends and community norms. In this way, “Emo”capitalizes on the sense of emotional catharsis and becomes more about forming (and performing) digital identities. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 今天的emo指数爆表了。 |

Today's emo index is off the charts. |

| 我的emo又开始作祟了。 |

My emo is acting up again. |

| emo的goodees也太可爱了 |

The emo goodees are just too cute. |

4.4.4. Coping Mechanisms and Community Building

The use of “Emo”is funny, and at times hyperbolic describes the emotional labour we feel or do. Users create a sense of belonging and collective empathy through sharing their “Emo”with one another. This extends to the often commented “Emo”:

“看到你的状态,我也emo了。加油!”(Seeing your status, I'm feeling emo too. Hang in there!)

By using it this way, users are brought together and support one another with the internet-language allowing for social tieswefts being woven in digital communities. As illustrated by the examples in the table below.

| Original Posting |

Translation |

| 看到emo朋友圈都不敢点赞怕别人尴尬 |

I see emo moments on WeChat and dare not like them for fear of embarrassing others. |

| 深夜emo,到现在为止我可能还是没有想清楚自己要什么 |

Late night emo, I still haven't figured out what I want. |

| 我什么都不能为你做,老婆我连想给你26000的热度都做不到…我突然觉得自己真的好渺小,能为你做的少之又少,现在甚至都觉得不配爱你,不配爱这么好的你…对不起,我破防了…我emo了…我彻底崩溃了… |

I can't do anything for you, my dear. I can't even give you the heat of 26,000... I suddenly feel so insignificant, able to do so little for you. Now, I even feel unworthy of loving you, unworthy of loving someone as wonderful as you... I'm sorry, my defenses are broken... I'm emo... I'm completely broken... |

4.5. Temporal and Contextual Variations

Our analysis discovered rich and dynamically differing trends that informed the temporal, contextual usage patterns of “Emo”in a period spanning from June 2024 through October 2024. These help us see the impact of social events and trends on how Chinese people use Chinsese in social media.

4.5.1. Seasonal Patterns

Seasonal patterns of “Emo”use were also observed from June 2024 to October 2024, reporting bigger peaks in assuming emotions depending on time-of-year; and accordingly to rumours —important events that had a huge impact due to unpleasant weather during certain periods:

June-July 2024: This month could be close to the end of the academic year for many students, leading them into decisions regarding higher education or embarking on a career. Use of “Emo”could reach its highest as we all start to get worried about leaving school, exams and what our futures will be like.

September-October 2024: This time of the year when new academic, or even fiscal years of many organizations start could lead to higher usage. This time can create anxiety and with added academic demands as well has career changes along side resetting goals.

4.5.2. Event-Driven Spikes

Significant event-driven spikes in “Emo”usage were also found during this time period, associated with major events or social phenomena:

Back-to-School Anxiety (September 2024): As students and parents adjust to a new school year, “Emo”expression usually sees an uptick, as they face off with problems from homework then college applications.

Mid-Autumn Festival (September 2024):This traditional holiday, which focuses on family reunion will also bring an “Emo”moment as a form of loneliness and being far from the family would refer to nostalgia and melancholy.

National Day Reflections (October 2024): During the National Day celebrations, a time typically associated with patriotic sentiment and contemplation, people may also engage in self-evaluation of their personal accomplishments and aspirations. This introspection could potentially trigger “Emo”expressions linked to individual development and the pressures of societal expectations.

These abrupt increases in usage demonstrate how “Emo”has transformed into a flexible linguistic tool for expressing collective emotional responses to events in society.

4.6. Linguistic Innovation and Creativity

The adoption of “Emo”in Chinese online discourse demonstrates the inventive and imaginative nature of internet-based communication. Online users have crafted an extensive array of phrases and combinations incorporating “Emo,” leading to an expansion of the term's meaning.

4.6.1. Compound Creations

We observed the creation of numerous compound words and phrases incorporating "Emo," such as:

-“Emo体质”(Emo constitution): Depicting the person apt to feeling “Emo”

- “Emo现场”(Emo scene): A scenario or environment leading to“Emo”feelings

- “Emo大师” (Emo master): Playfully referring to someone adept at expressing or inducing “Emo”states.

In fact, these products of blending illustrate that prototypical word “Emo”has been well integrated to Chinese; semantics continued evolving also.

4.6.2. Multimodal Expressions

“Emo”use spans text and other semiotic resources including memes, stickers and emojis. The "Emo 狗" (transl. Emo dog) meme that showcases a sad Shiba Inu has turned into cliched iconography for the label of “Emo”in image form, as well. Such multimodal employment highlights the fact that “emo,” as a semantic field, has broadened beyond its textual element to also include visually expressive aspects.

4.6.3. Intertextuality and Cultural References

Our closer analysis demonstrated frequent intertextual collations of “Emo”to popular culture and literary or historical events. For instance:

“看完《瑞克和莫蒂》第三季,陷入了存在主义emo。” (After watching season 3 of Rick and Morty, I fell into existential emo.)

Indeed, the intertextual use of “Emo”suggests that it has become an adaptable (adaptable within its own historical context) tool for mediating personal emotional experiences with broader cultural narratives.

5. Conclusion

This study aims to explore the semantic extension and metonymical usage of Emo in Chinese internet language as gates into looking at serious things like emotion or identity. This has yielded a number of important new results concerning how language evolves in digital contexts.

The results of the semantic analysis showed four dominant senses to which Blank’s (1999) theory determined these are extensions that might appear in many other cases where Hiraeth is an antonym: 37% melancholy and nostalgia, 28% existential contemplation, 22%, temporary emotional vulnerability and finally aesthetic & atmospheric description encompassing13%. As Crystal (2006) notes, these frequent shifts are typical of the fast-changing semantics in internet language.

Our metonymical analysis, in the same vein of Radden and Kövecses's (1999) cognitive metonymy theory revealed that Emo is a physical state; an entity as matter, as energy or force; and was treated also abstractly such practice this time depict him/her "as living". The present results thus go some way toward providing support for Littlemore's (2015) claims that metonymy is a ‘key cognitive operation’ that provides a relatively concrete domain through which more abstract concepts can be understood.

The study details changes in emotional expression through Chinese digital culture. Although Chinese culture historically favours emotional containment (Ye 2004), our results indicate that younger generations are developing novel linguistic means of expressing their affective self. This aligns with Chen et al. s (2018) analysis of the changes in emotional disclosures on Chinese social media. Temporal analysis of the study yielded unique seasonal and urban events associated with spikes in 'Emo' usage. This is in line with Herring and Androutsopoulos's (2015) argument about understanding computer mediated discourse analysis by examining both technological as well as sociocultural context.

More broadly, our blended methodology of corpus-driven quantitative analysis alongside in depth qualitative enquiry has given us a collaborative framework for exploring change and stability in digital language forms. As Zhang (2012) argues, this kind of detailed examination is important to learn about the fluid language use in China's digital world.

5.1. Key Findings

Since then, the term “Emo”has gone through an impressive semantic extension and is now everything from sadness, nostalgia or existential reflection to vulberability in different moments of one's life — it can even be a way for describing some aesthetics and atmospheres. Most of the time it is used metonymically as if writing were a physical state, or a substance or force—vividly providing symbolic expressions capable of representing complex emotions. Furthermore, the opt for of “Emo”mirrors broader cultural and social changes in China that reflect evolving attitudes towards emotion led lives to generational ideals an pressures of contemporary life. The frequency of the term is also subject to temporal and contextual differences, revealing specific patterns account for day-to-day, monthty or recurring social trends. Finally, the incorporation of “Emo”into Chinese internet language manifests related aspects such as sociolinguistic creativity in terms compound constructions and multimodal motifs, intertextual practices.

These findings lead to several key implications. First, they shed light on the remarkable adaptability of internet language to repurpose foreign terms towards local communicative goals, extending previous work by Bolton and Graddol (2012) in relation to English in China. Second, they expose evolving views about the display of emotion as well — showing that younger cohorts are beginning to forage a realm in which vulnerability is becoming more publicly acceptable (Li et al., 2022). Thirdly, they point to the ways that digital platforms are enabling new modes of emotional expression and community formation via pooled linguistic commodities (Zappavigna 2012).

5.2. Implications

This set of findings leads to a number of significant conclusions. From a linguistic point of view, it teaches us more about semantic change processes in the digital age and how loanwords such as “Emo”are quickly taken up within net language. For popular culture studies the rise and decline of ‘Emo’ can provide some points object to explore more about how Chinese see emotion in social dimension, especially for younger people. In terms of digital communication, the research makes clear how metonymical usage and semantic extension enhance our toolkit for more gradated emotional expression in online spaces. In the context of social psychology, how Chinese internet users use “Emo”allow us to glimpse into their shared emotional experiences and coping style with respect to pressures from society at large as well as national events.

This research serves to expand our broader view of how language is modulating in the digital environments also considering cultural aspects for linguistic evolution. Other scholars, such as Traugott and Dasher (2001) have reiterated that semantic change is pragmatic in nature and emerges from system-external sociopragmatic contexts of speaker-listener interactions — something clearly illustrated by the Chinese internet discourse surrounding 'Emo'. These results shed some light on this particular type of linguistic change and also offer interesting perspectives on the interaction of language variation in digital environments more generally with emotional expressivity amongst contemporary Chinese speakers.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

While these findings are informative, several limitations of the study suggest future improvements for research. The bias of the platform for instance as most data was collected on large social media platforms which left a lot to explore in smaller online communities or real life settings. That said, privacy concerns limited our ability to undertake more detailed demographic analysis — such as the role that age, gender and regional background play in terms of both utilizing “Emo”and interpreting it. A longitudinal study would be an interesting way to examine how “Emo”has changed -- and whether its evolution has stabilized or if the word continues drifting semantically. Further, cross-linguistic comparisons with English “Emo”and similar words from other languages may shed light on international patterns of online emotional language. Lastly, a detailed multi-modal analysis of its visual and video-based expression coupled with non-textual media can provide better insights across the platforms.

Further research could explore how the term, "Emo," is further semantically extended over time in response to new social and technological influences. Furthermore, crosslinguistic comparison studies exploring similar linguistic phenomena in different cultural backgrounds would be helpful for demonstrating the global trend of internet language innovation as observed by Wei (2013) through investigating bilingual communicative tendencies.

In conclusion, semantic extension and metonymical peculiarity here could somehow be a handy case from Chinese internet language to observe how languages change in digital context. One of the interesting aspects is how users adapt sampling techniques to express emotional states and cultural reflections, both common tropes in online interaction as it weathers shifting social climates. More research in this is needed for insight into how language, culture and technology interact during the digital age.

References

- Bolton, K. & Graddoll, D. 2012. ‘English in China today: The current popularity of English in China is unprecedented, and has been fuelled by the recent political and social development of Chinese society.’English Today, 28(3), 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Blank, A. (1999). Why do new meanings occur? A cognitive typology of the motivations for lexical semantic change. In A. Blank & P. Koch (Eds.), Historical Semantics and Cognition (pp. 61-89). Mouton de Gruyter.

-

Chen, X., Zhou, X., & Zhang, L. (2018). Emotional expression in Chinese social media: An analysis of internet language features. Journal of Chinese Language and Computing.

- Crystal, D. (2006). Language and the Internet (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- In Fang, X; , & Yue, Y. (2016). The semantic evolution of Chinese internet neologisms: A case study of "geili". Journal of Chinese Linguistics.

- Gao, L. (2012). Digital age and linguistic creativity in Chinese context. World Englishes, 31(1), 87-97.

- Ge, J., & Herring, S. C. (2018). Communicative functions of emoji sequences on Chinese social media. First Monday, 23(11). [CrossRef]

- Herring, S. C., & Androutsopoulos, J. (2015). Computer-mediated discourse 2.0. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.), The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (2nd ed., pp. 127-151). John Wiley & Sons.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

- Li, H., Ran, B., & Wang, X. (2015). Cultural models of emotion expression in Chinese: A linguistic perspective. International Journal of Language and Culture.

- Li, J., Liang, L., & Li, Y. (2022). Code-switching and loanwords in Chinese social media: A corpus-based study. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 50(2), 367-394.

- Li, M., Chen, Y., & Zhang, K. (2022). Code-switching and loanwords in Chinese social media: Patterns and motivations. Journal of Sociolinguistics.

- Littlemore, J. (2015). Metonymy: Hidden shortcuts in language, thought and communication. Cambridge University Press.

- Liu, Y. (2020). English loanwords and internet memes in Chinese digital communication. Asian Englishes.

- McCallum, L., Olliver, S., & Vanderschantz, N. (2019). Emoji and self-identity: A snapshot of New Zealand emoji use. In Proceedings of the 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction (pp. 508-512).

- Panther, K.-U., & Thornburg, L. L. (2007). Metonymy. In D. Geeraerts & H. Cuyckens (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics (pp. 236-263). Oxford University Press.

- Radden, G., & Kövecses, Z. (1999). Towards a theory of metonymy. In K.-U. Panther & G. Radden (Eds.), Metonymy in Language and Thought (pp. 17-59). John Benjamins.

- Tao, H. (2017). Chinese internet language: A study of identity construction. Journal of Pragmatics.

- Traugott, E. C., & Dasher, R. B. (2001). Regularity in semantic change. Cambridge University Press.

- Wei, R. 2013; ‘Chinese-English bilingual education in China: Model,momentum, and driving forces.’ The Asian EFL Journal, 15(4), 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L., & Zhu, H. (2019). Metonymic expressions of depression on Chinese social media platforms. Discourse Studies.

- Ye, Z. (2004). The Chinese cultural model of emotions. In Chinese Learners' Communication in English: A Cultural Approach (pp. 47-68). Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

- Ye, Z. (2004). Chinese categorization of interpersonal relationships and the cultural logic of Chinese social interaction: An indigenous perspective. Intercultural Pragmatics, 1(2), 211-230.

- Yus, F. (2019). Multimodality in memes: A cyberpragmatic approach. In P. Bou-Franch & P. Garcés-Conejos Blitvich (Eds.), Analyzing Digital Discourse: New Insights and Future Directions (pp. 105-131). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zappavigna, M. (2012). Discourse of Twitter and Social Media: How We Use Language to Create Affiliation on the Web. Continuum.

- Zhang, M., & Wang, R. (2021). A study on the characteristics and functions of Chinese internet neologisms. Journal of Contemporary Chinese Studies, 8(2), 195-213.

- Zhang, Q., & Cassany Viladomat, D. (2019). The dynamics of Mandarin Chinese on WeChat: A sociolinguistic perspective. Chinese Language and Discourse.

- Zhang, Q. (2012). English in China's language ecology. World Englishes, 31(2), 249-263.

- Zhang, S., & Wang, L. (2021). A study of internet slang among Chinese netizens. Applied Linguistics Review.

- Zhang, W. (2012) ‘Chinese-English code-mixing among China’s netizens:.

- Chinese-English mixed-code communication is gaining popularity on the Internet.’ English Today, 28(3), 40–52. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).