1. Introduction

In recent years, solid propellants have been widely used in aerospace. Some scholars have improved their performance by adjusting compositions and optimizing preparation processes, while others have enhanced their performance by using additives [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The commonly used propellant is ammonium perchlorate (AP), which plays a crucial role as a high-energy oxidizer in propellants, and its thermal decomposition performance directly determines the combustion performance of the propellant [

6,

7,

8]. Common methods to regulate the thermal decomposition characteristics of AP include refining the particle size of AP and introducing catalysts [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, due to the risks associated with refining AP, more and more control over pyrolysis performance is achieved by introducing catalysts into AP.

Carbon black (CB), due to its low production cost, significant performance, and wide availability and ease of modification, has been widely used in the field of catalysts [

15,

16]. The types of CB (conductive CB, acetylene black, coal-based CB, specialty CB, etc.) and the structure of CB (particle size, oil absorption value, iodine absorption value, specific surface area, etc.) have different effects on the combustion performance of propellants. For example, acetylene black helps stabilize the burning rate, while medium-superior CB may lead to a decrease in burning rate. The finer the CB particle size, the higher the platform burning rate of the propellant, which can even trigger platform or Maisha combustion phenomena [

17]. CB with a high specific surface area can provide more active sites, promoting the thermal decomposition of the propellant [

18]. The raw materials for CB production are mainly divided into three categories such as coal, petroleum, and biomass [

19]. Coal tar is a byproduct of the coal processing process, containing a high level of aromatics and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. CB produced from coal tar has characteristics such as high hardness, high density, large specific surface area, and environmental friendliness [

20,

21,

22]. Although CB has been proven to be an effective combustion catalyst for AP thermal decomposition, there has been little research on the structural properties of coal-based CB and their impact on AP thermal decomposition, and the reported methods for preparing CB suitable for catalytic performance are often complex and uneconomical. Therefore, studying the relationship between the structural properties of coal-based CB and AP combustion performance is meaningful, as it can provide reference data for the selection and development of efficient catalysts in AP-based propellants. Simultaneously researching simple and economical methods to achieve stable preparation of CB with excellent catalytic performance has enormous economic value.

In this paper, we first studies the functional relationships between the oil absorption value, compression oil absorption value, oxygen content, and the catalytic pyrolysis of nine types of CB [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. On these basis, we further uses coal tar as the raw material to prepare five types of coal-based CB1-CB5 at pyrolysis temperatures of 1000-1800 ℃. This study finds that a suitable CB quality index system can provide theoretical support for stabilizing propellant performance, establishes the structure-activity relationship between CB structure and catalytic performance, promotes the application of coal-based CB in catalysts, and demonstrates its advantages in catalytic performance regulation, providing feasible suggestions for its actual production and process optimization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

CBa, SJR-30, Shanghai Coking Co., Ltd.; CBb, ST-Special, Suzhou Baohua Carbon Black Co., Ltd.; CBc, Special Black-1#, Suzhou Baohua Carbon Black Co., Ltd.; CBd, Zhongchao; CBe, C111, Shanghai Coking Co., Ltd.; CBf, Zhongxiang 550, Shandong Zhongxiang New Materials Co., Ltd.; CBg, Cabot 550, Wuhan Jinqiu New Materials Co., Ltd.; CBh, Tower Two Chemical 770, Jiangxi Black Cat Carbon Black Co., Ltd.; CBi, Bola 660, Liaoning Bola Carbon Black Co., Ltd.; Coal tar A, Ma’anshan Iron and Steel Co., Ltd.; Ammonium perchlorate, analytical grade, Xi’an Modern Chemical Research Institute; Anhydrous ethanol, analytical grade, Shandong Yivi Chemical Co., Ltd.

Electronic balance FA2004N Shanghai Precision Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd.; Infrared analyzer NICOLET6700FT-IR ThermoFisher, USA; Elemental analyzer Vario ELⅢ Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Germany; Mercury porosimeter Autopore Ⅳ 9510 Micromeritics, USA; Laser confocal Raman spectrometer inVia Renishaw, UK; Thermogravimetric analyzer STA-2500, Netzsch Scientific Instruments Trading (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.; Laser particle size analyzer MS2000 Scirouo Mu Malvern Instruments; Scanning electron microscope JSM-6490, JEOL Ltd.; X-ray diffractometer D&ADVANCE from Bruker, Germany; Tubular furnace 801000 mm Nanjing Boyun Tong Instrument.

2.2. Model Selection

Using SPSS 27 software to fit curve estimation models, perform model selection, prediction, and evaluation. Statistical methods include moving average method, curve estimation, etc., with a significance level of α=0.1.

Curve models include linear models

secondary models

composite models

growth models

logarithmic models

cubic models

S-type models

exponential models

inverse models

power models

Indicator coefficient of determination R

2: 0 ≤ R

2 ≤ 1, the closer to 1, the better the fitting effect of the model; P-value: P < 0.1 indicates that the fitted model has statistical significance. Select the best curve model through the P and R

2 [

23].

2.3. Calculation

(1) Calculation of the maximum filling rate of CB. The maximum filling rate is defined as the maximum volume fraction of particles in a given matrix, which can be calculated using the following relationship for the maximum volume fraction in a random medium [

28]:

Where ρ is the density of CB, D is the oil absorption value, and in this study, the density of all types of CB is taken as 1.80 g·cm

-3, and the Φ value is related to the yield stress of the CB suspension.

(2) Calculation of CB particle size analysis. The particle size analysis of CB was conducted using a laser particle size analyzer, where D50 represents the particle size at which the cumulative particle size distribution reaches 50%, indicating the average particle size of the powder; D97 represents the particle size corresponding to the cumulative particle size distribution reaching 97%, indicating the particle size index of the coarse end of the powder.

2.4. CB Preparation Methods

Coal tar A serves as the carbon source, and compressed air is used as the carrier gas. Special CB is prepared using the incomplete combustion method, with suspended CB particles in the gas collected using cold water and the tail gas filtered. First, the coal tar is placed in the constant temperature zone of the tube furnace, with both ends sealed. Compressed air is continuously introduced for 30 mins to create a closed turbulent system inside the tube furnace and to evacuate other gases [

29,

30]. Turn on the tube furnace and temperature controller, set the heating program of the tube furnace from room temperature to 1000, 1200, 1400, 1600, 1800 ℃ with a heating rate of 5 ℃·min

-1. After reaching the set temperature, maintain it for 120 mins, stop the heating program and wait for the furnace temperature to cool down to room temperature. Collect the reaction products, which will be filtered and washed, and dry them at 60 ℃ for 12 h. The completely dried products are named CB1, CB2, CB3, CB4, and CB5.

2.5. Testing of the Catalytic Performance of CB

Mix CB with AP in a mass ratio of 5:100, disperse in an appropriate amount of ethanol solution, and sonicate for 30 mins. Dry the sample in a 70 °C oven until the ethanol is completely evaporated, resulting in a dry sample. Take 5-10 mg of the mixed sample and measure it on the thermogravimetric differential thermal analyzer (DTG-60) with the heating rate of 20 ℃·min-1. To ensure the reliability of the catalytic performance, each sample was subjected to three DTG and DTA tests.

2.6. Characterizations

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements were performed with JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope at 100 kV [

31,

32]. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed on D&ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation and operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. Nitrogen adsorption/desorption measurements were determined by Micromeritics. The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum was recorded using a NICOLET 6700 Fourier transform spectrometer in the range 4000-500 cm

-1 [

32,

33,

34]. Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis was carried out using a STA-2500 TG/DSC instruments in a temperature range from 25 to 500 °C with a rate of 20 °C·min

-1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed with an American Thermo ESCALAB250 electron spectrometer using Al K irradiation [

31]. The Micromeritics ASAP 2020 nitrogen adsorption apparatus was used to measure the N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms at -195 °C. The specific surface area and the pore size distribution of the sample were determined using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) equation and the Barrett-Joyner-Halendar (BJH) method. Crystal phase of the sample was analyzed by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Cu Kα radiation within the 2θ range of 20-80°.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Physicochemical Parameters of CB

3.1.1. Analysis of the Structural Parameters of CB

The commonly used methods for determining the specific surface area and structural degree of CB are the measurement of iodine absorption value and oil absorption value (DBP), where the measured iodine absorption value is directly proportional to the specific surface area of CB, and the measured oil absorption value is directly proportional to the structural degree of CB [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. From

Table S1, it can be seen that the iodine absorption value of CBa-CBj ranges from 119 to 161 g·kg

-1, the oil absorption value ranges from 110×10

5 to 140×10

5 m

3·kg

-1, the compression oil absorption value ranges from 93×10

5 to 110×10

5 m

3·kg

-1, the nitrogen adsorption specific surface area ranges from 98×10

-3 to 135×10

-3 m

2·kg

-1, and the oxygen content ranges from 0.7% to 5.1%. The iodine absorption value of CB decreases, and the oil absorption value decreases accordingly. The reason is that the smaller the particle size of CB, the larger its specific surface area, which can adsorb more iodine. The measured iodine absorption value is higher, and the smaller the particle size of CB, the higher its surface energy and stronger surface adsorption, making it easier for CB to aggregate together and form a structurally higher CB [

40].

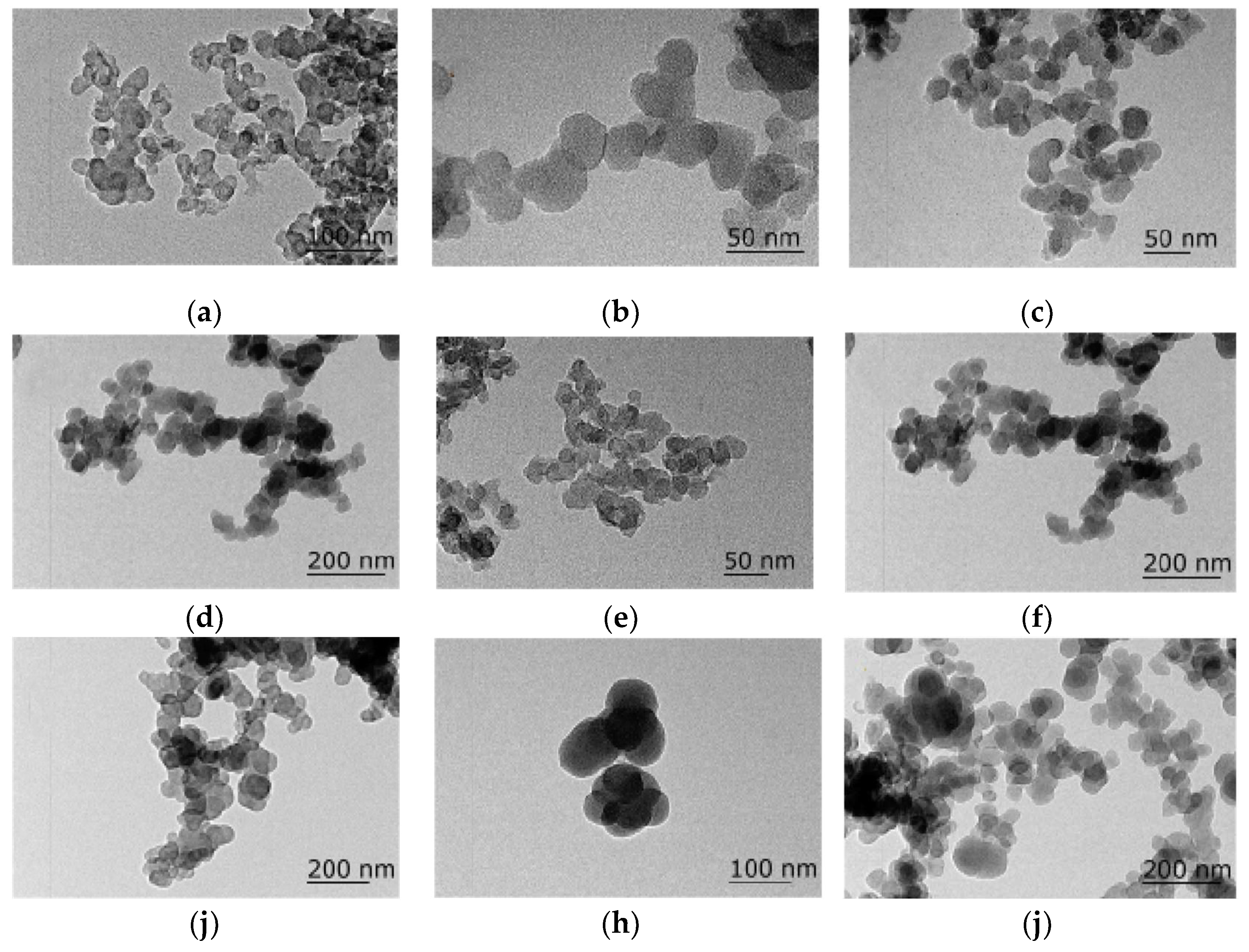

Figure S1 shows the particle size distribution and cumulative particle size distribution curves of nine types of CB, with D50 of CBa-CBj ranging from 0.23 to 5.93 μm, and D97 ranging from 4.01 to 14.95 μm. As shown in

Figure 1, computer image analysis of the TEM photos of CB indicates that the size of CB aggregates ranges from 60 to 300 nm, and the particle size range of CB is between 1 μm and 10 μm.

3.1.2. Analysis of the Combustion Catalytic Performance of CB

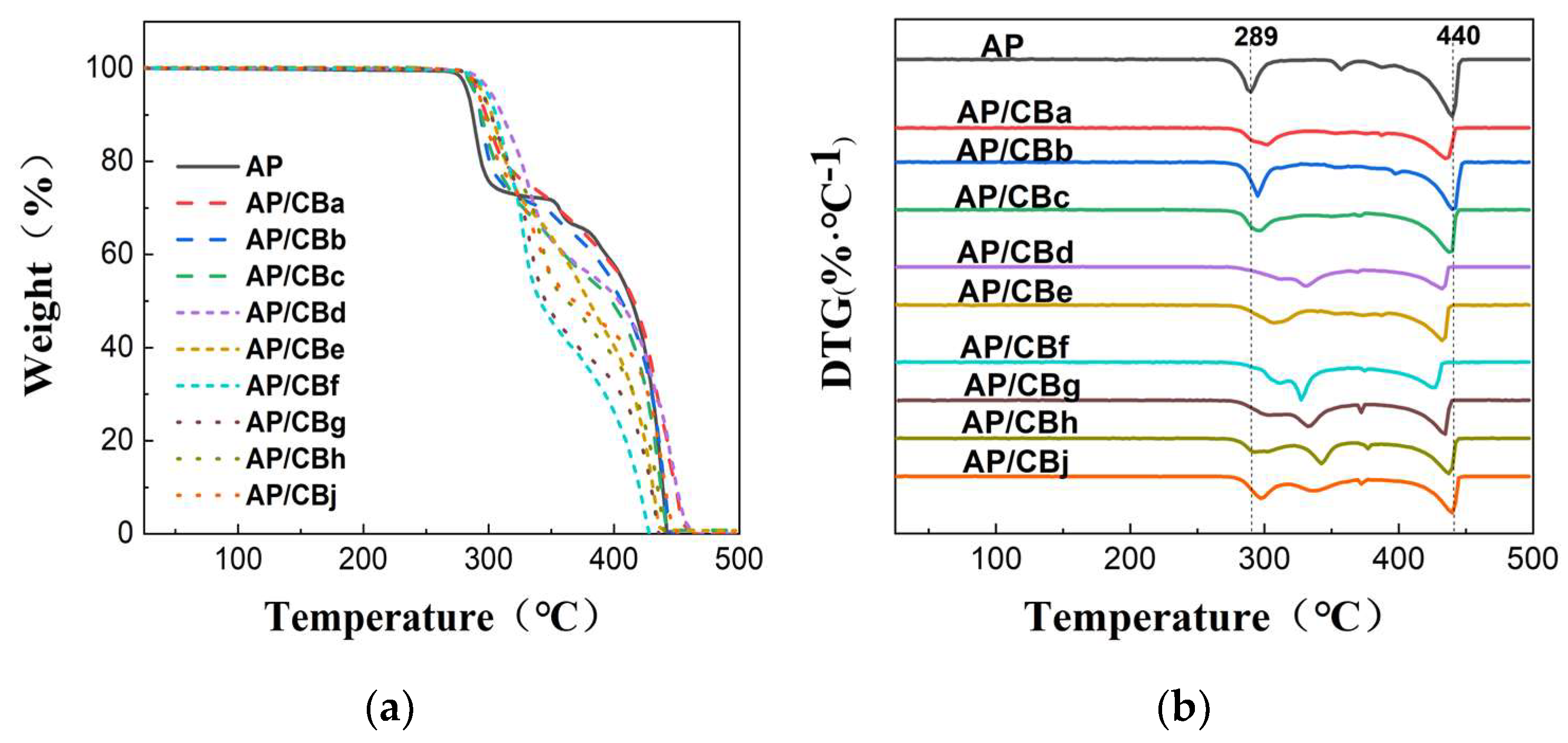

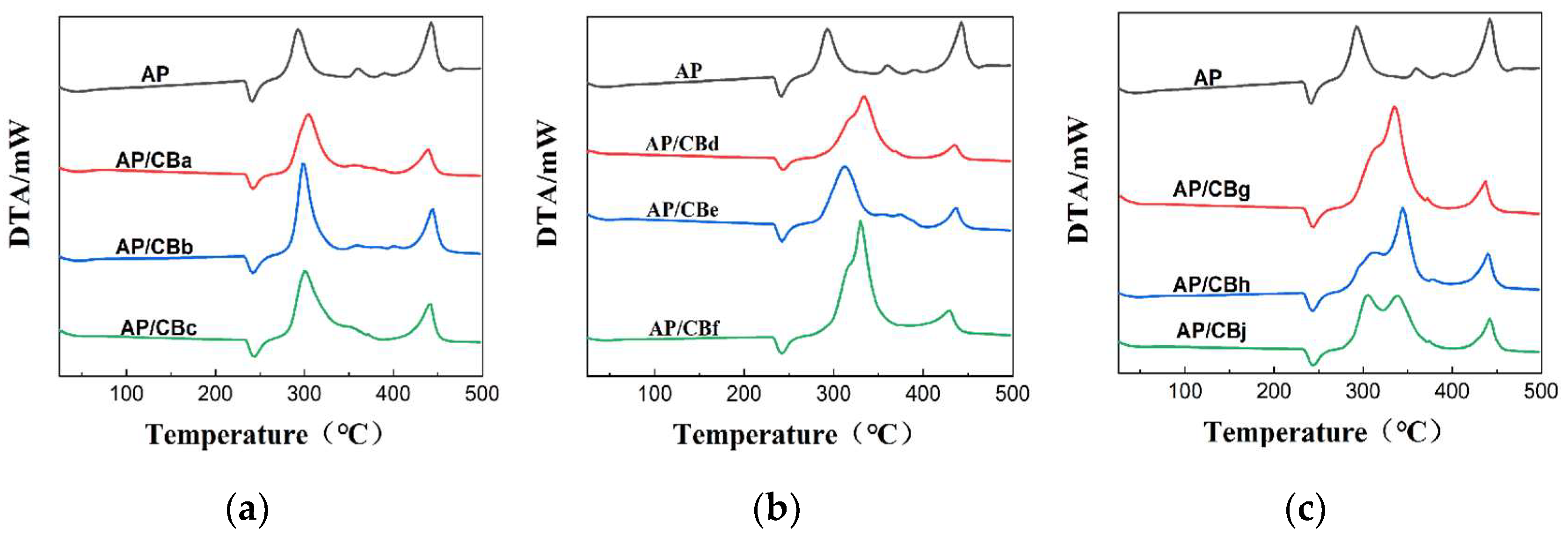

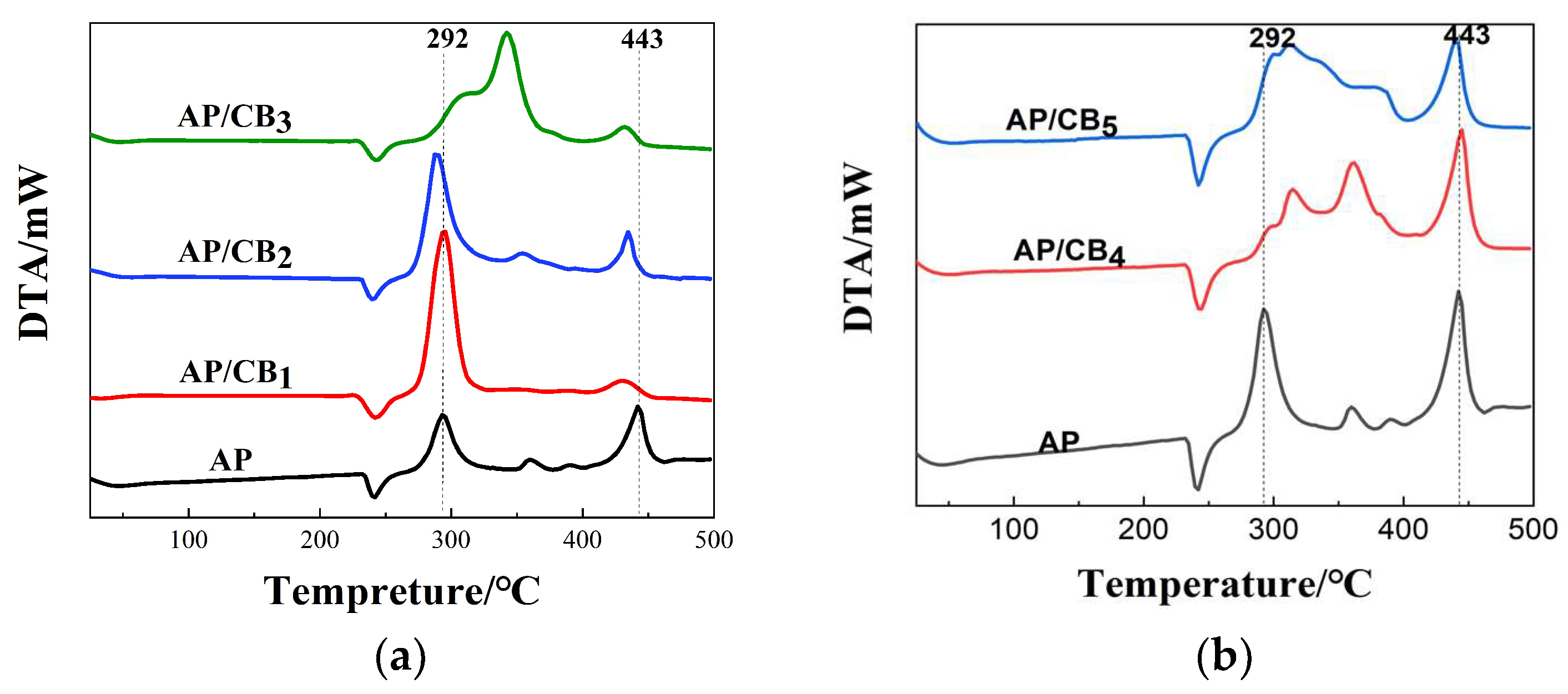

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, to analyze the thermal decomposition performance of CB/AP composite particles, the TG, DTG, and DTA thermal decomposition curves of nine CB samples mixed with AP were determined. Pure AP exhibits a typical absorption peak around 241 ℃, which corresponds to the phase transition process of AP. A typical exothermic peak appeared around 293 ℃, which is the low-temperature decomposition peak of AP, where AP partially decomposes into NH

3 and HClO

4. A typical exothermic peak appeared around 443 ℃, which is the high-temperature decomposition peak of AP, where intermediate products generate volatile gases such as N

2O, NO, H

2O, NO

2, ClO, ClO

3, and HCl.

As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 1, the addition of a small amount of CB has no significant effect on the crystal transformation of AP. The effects on the low-temperature decomposition of AP varies, among which CBd, CBf, CBg, and CBh increase the low-temperature peak and exhibit the best catalytic performance, rising by 90, 86, 92, and 101 ℃, respectively. The nine CB samples all reduced the high-temperature decomposition peak, among which CBd, CBe, and CBf exhibited the best catalytic performance, reducing by 12, 12, and 18 ℃, respectively. It can be concluded that CB can enhance the catalytic performance of AP thermal decomposition.

3.1.3. Analysis of CB Quality Index System

1. First item

Curve estimation

Based on the data from

Table S1 and

Table 1, the iodine absorption value, oil absorption value, compression oil absorption value, nitrogen adsorption specific surface area, O content,

Φ value, etc., were used as independent variables, while the low-temperature peak temperature and high-temperature peak temperature were used as dependent variables. Curve estimation was utilized to fit the equations relating the peak temperature of CB/AP composite particles to the physicochemical properties of CB, as shown in

Table S2 [

23].

The fitting results show that the curve model with oil absorption value as the independent variable and high-temperature peak as the dependent variable has a coefficient of determination between 0.5 and 1 with R

2 and the P<0.1. The optimal model is the secondary model:

The compression oil absorption value as the independent variable and high-temperature peak as the dependent variable has a coefficient of determination between 0.5 and 1 with R

2 and P<0.01. The optimal model is the logarithmic model:

The O content as the independent variable and high-temperature peak as the dependent variable has a coefficient of determination between 0.5 and 1 with R

2 and P<0.05. The optimal model is the S-type model:

From

Table S2, it can be seen that there is a significant correlation between the oil absorption value, compression oil absorption value, and the O content with the catalytic performance of CB/AP composite particles.

Second item

Key factor analysis

Based on the above results, an analysis of the structural parameters of nine types of CB was conducted. It can be concluded that CB samples with larger specific surface areas and smaller particle sizes exhibit better catalytic pyrolysis and acceleration effects. The increase in primary structural native particles, reduction in particle aggregates, and increase in surface O-containing functional groups significantly enhance their catalytic combustion effect, which is a key factor in promoting the CB platform effect and reducing the pressure index. The pressure index Y value of CBa-CBj on the combustion performance measurement platform was analyzed by polynomial fitting with the physical structure parameters of CB samples, such as iodine absorption value, oil absorption value, specific surface area, O content, etc. [

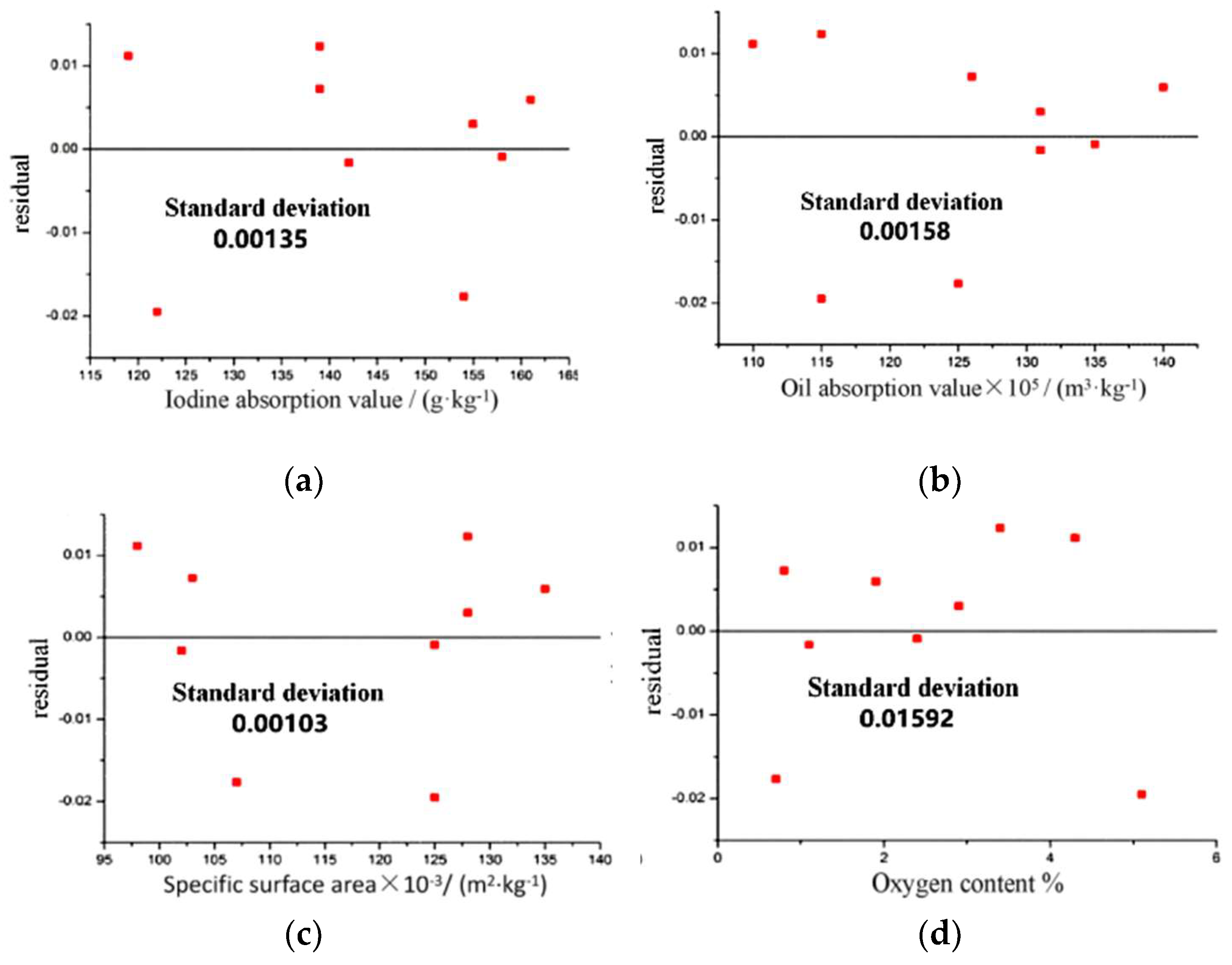

23], and the correlation deviation was as follows: As shown in

Figure 4, the standard deviations of the iodine absorption value, oil absorption value, specific surface area, and O content of the CB samples with respect to the platform pressure index are 0.00135, 0.00158, 0.00103, and 0.01592, respectively. Therefore, the correlation of the platform pressure index of the CB samples with CB is: specific surface area > iodine absorption value > oil absorption value > O content.

3.2. Analysis of CB Preparation Process

This paper uses the furnace method to prepare CB, with the newly generated CB particles suspended in the flue gas, and after cooling, washing, filtering, drying, and collecting, the finished product is obtained [

41,

42,

43,

44]. According to study the relationship between the pyrolysis temperature and structural parameters of homemade CB to construct a regression equation, and derive the optimal reaction temperature for furnace preparation.

3.2.1. Determination of Coal Tar Properties

CB is produced from C-containing materials through incomplete combustion or thermal cracking reactions. The higher the content of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the raw oil, the better the quality and yield of CB [

45,

46]. Therefore, it is essential to select raw oil with a high content of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

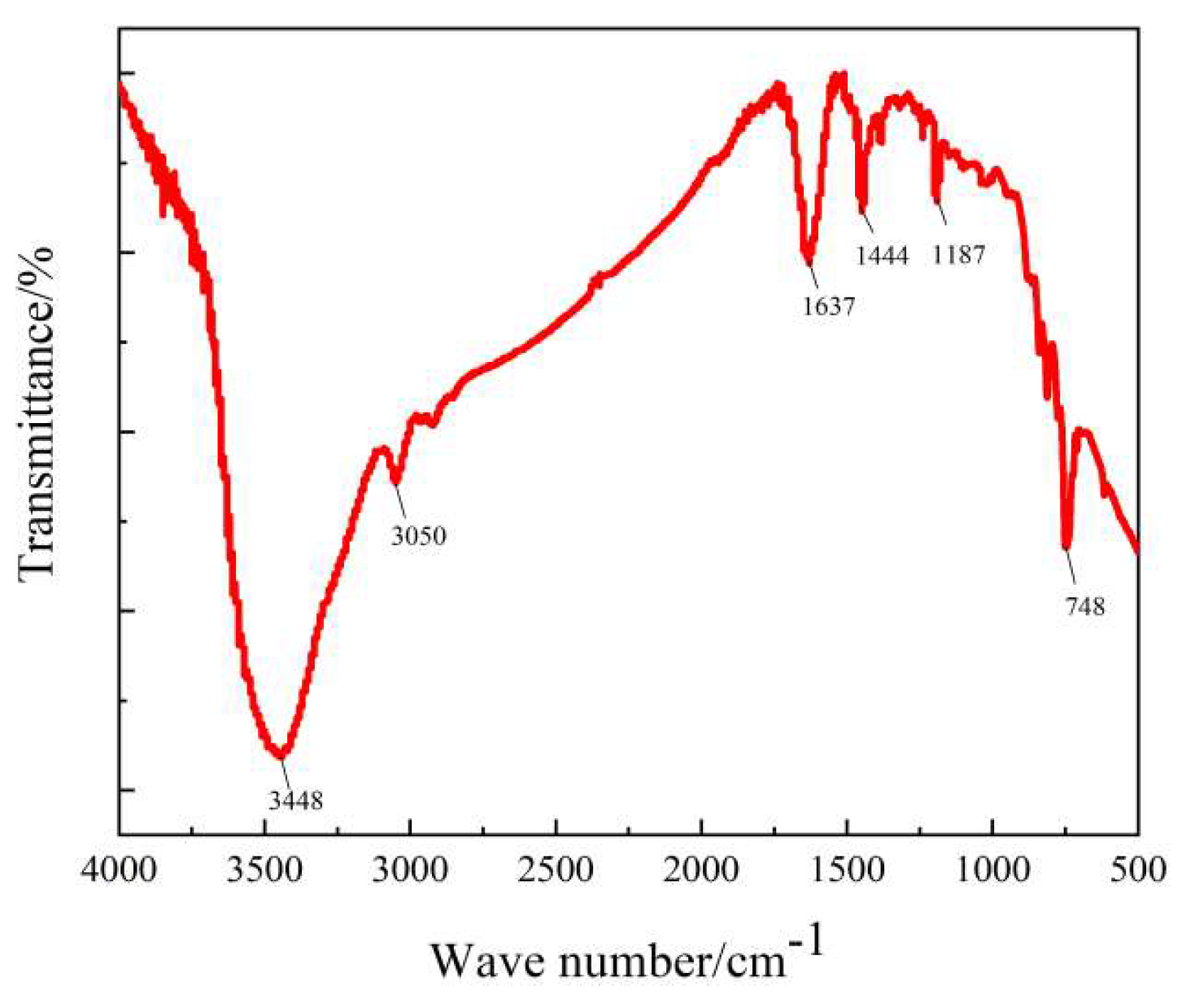

The FT-IR of coal tar A is shown in

Figure 5. The absorption peak generated at 3448 cm

-1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the O-H. The absorption peak generated around 3050 cm

-1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the C-H on the aromatic ring. An absorption peak for the skeletal vibration of the aromatic ring appears around 1444 cm

-1, and the multiple absorption peaks related to the out-of-plane bending vibrations of the C-H on the aromatic ring are generated in the range of 900 to 650 cm

-1, indicating the structural complexity and diversity of aromatic compounds in coal tar. The absorption peak at 1637 cm

-1 generated in the surroundings corresponds to the stretching vibrations of C=C and C=O on the aromatic ring. The absorption peak at 1187 cm

-1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of C-O-C bonds in ether and ester O-containing functional groups. The absorption peaks generated at 748 cm

-1 and 733 cm

-1 correspond to the -(CH 2) n- in-plane rocking vibrations.

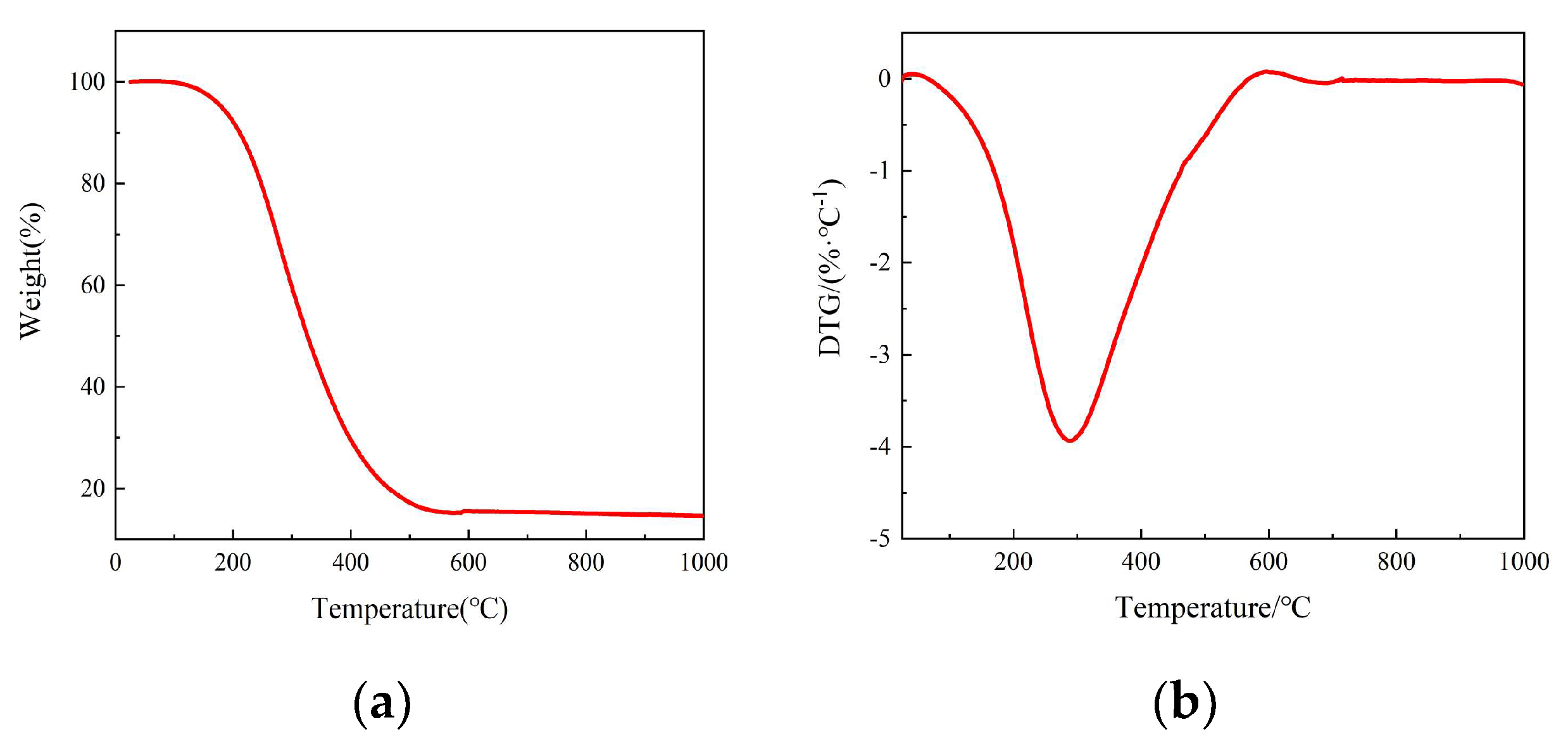

As shown in

Figure 6, the pyrolysis process of coal tar A mainly includes three stages. The first stage is the precipitation process, where the weight loss rate of coal tar A is 2.1% due to the evaporation of surface adsorbed free water and small molecule aromatic compounds from room temperature to 140 ℃. The second stage is the active thermal decomposition stage, because the hydrocarbons, carboxylic acids, aromatics, phenols and other organic compounds in the coal tar components decompose in large quantities at this time, the weight loss rate reaches the peak, and the weight loss rate of coal tar A is 82.4% from 140 to 650 ℃. The temperature range for the third stage is 650-1000 ℃, which is the high-temperature polycondensation stage, where the main products are CO2, CO, and a small amount of CH4, with a weight loss rate of 0.9%. The residual content is around 10% with most substances decomposed, leaving only a small amount that cannot be decomposed at 800 ℃. The CB prepared from coal tar contains 18% ash, 75% volatile matter, and 7% fixed carbon.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Structural Parameters of CB

Coal tar A is selected as the carbon source, with compressed air as the carrier gas, to prepare special CB using the incomplete combustion method. As shown in

Table 2, with the increase of the preparation pyrolysis temperature, the iodine absorption value first increases and then decreases, reaching a maximum at 1600 ℃, indicating a higher primary structure and the largest specific surface area. With the increase of the preparation pyrolysis temperature, the oil absorption value shows a general increasing trend, reaching a maximum at 1800 ℃ with the highest structural degree [

47]. With the increase of the preparation pyrolysis temperature, the O content shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, reaching a maximum at 1600 ℃.

Figure S2 shows the particle size distribution of CB samples prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures. The particle size of the prepared samples mainly ranges from 5-10 μm, with the average particle size CB5 > CB1 > CB2 > CB3 > CB4, which is directly proportional to their iodine absorption value. CB5 has the smallest specific surface area, the highest structural degree, and the largest particle size. CB4 has the largest specific surface area, a relatively large structural degree, and the smallest particle size. Therefore, CB4 with a lower particle size and larger specific surface area was selected as the sample for acid-base activation treatment in subsequent studies.

3.2.3. Analysis of the Thermal Catalytic Performance of CB

By substituting the structural parameter values of CB1-CB5 from

Table 2 into the formulas in

Table S2, the high-temperature peak values of the CB/AP composite particles can be simulated and calculated, with high-temperature peaks of 441.73 ℃, 429.15 ℃, 424.83 ℃, 425.25 ℃, and 430.95 ℃, and high-temperature peaks of 427.54 ℃, 418.82 ℃, 435.18 ℃, 432.74 ℃, and 436.37 ℃, and high-temperature peaks of 426.85 ℃, 431.96 ℃, 433.76 ℃, 436.48 ℃, and 435.57 ℃.

Figure 7 shows the DTA images of pure AP and CB/AP composite particles. The experimental results indicate that the first endothermic peak of all particles appears at nearly the same temperature, approximately 243 ℃, corresponding to the polymorphic transition of AP, which suggests that the addition of a small amount of homemade CB has no significant effect on the polymorphic transition of AP. All particles exhibit both low-temperature exothermic peaks and high-temperature exothermic peaks, with significant differences in the low-temperature exothermic peaks, indicating that homemade CB has a varying impact on the low-temperature decomposition of AP. The low-temperature exothermic peaks of CB/AP composite particles appear at 295 ℃, 288 ℃, 341℃, 313 ℃, 361 ℃, 311 ℃, and 384 ℃, respectively. The differences in high-temperature exothermic peaks are relatively small, indicating that the homemade CB has a minor impact on the high-temperature decomposition of AP. The high-temperature exothermic peaks of CB/AP composite particles appear at 429 ℃, 433 ℃, 433 ℃, 439 ℃, and 435 ℃.

As shown in

Table 4, the relative error between the actual values and theoretical values of the high-temperature peaks of CB/AP composite particles is small, indicating that the peak temperature model formula for CB/AP composite particles can be used to guide the actual production of CB.

3.2.4. CB Preparation Process and Structural Parameter Regression Analysis

Based on the data from

Table 2 and

Table 3, the pyrolysis temperature is taken as the independent variable, while the iodine absorption value, oil absorption value, compression oil absorption value, nitrogen adsorption specific surface area, and

Φ value are taken as dependent variables. The equation relating pyrolysis temperature to the structural parameters of CB is fitted using curve estimation, as shown in

Table S3 [

23]. The fitting results show that the optimal model for the oil absorption value is the S-type model, while the optimal model for the

Φ value is the logarithmic model. The determination coefficient R

2 of the curve model fitted with oil absorption value and

Φ value is between 0.8 and 1, with P < 0.05.

As showen in

Table 3,

Table 4and

Table S3, there is a significant correlation between the pyrolysis temperature and the oil absorption value and

Φ value in the range of 1000 ℃ to 1800 ℃. With the increase of the preparation pyrolysis temperature, the iodine absorption value shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. The oil absorption value roughly exhibits an S-type function trend with

and the

Φ value roughly exhibits a logarithmic function trend with

4. Discussion

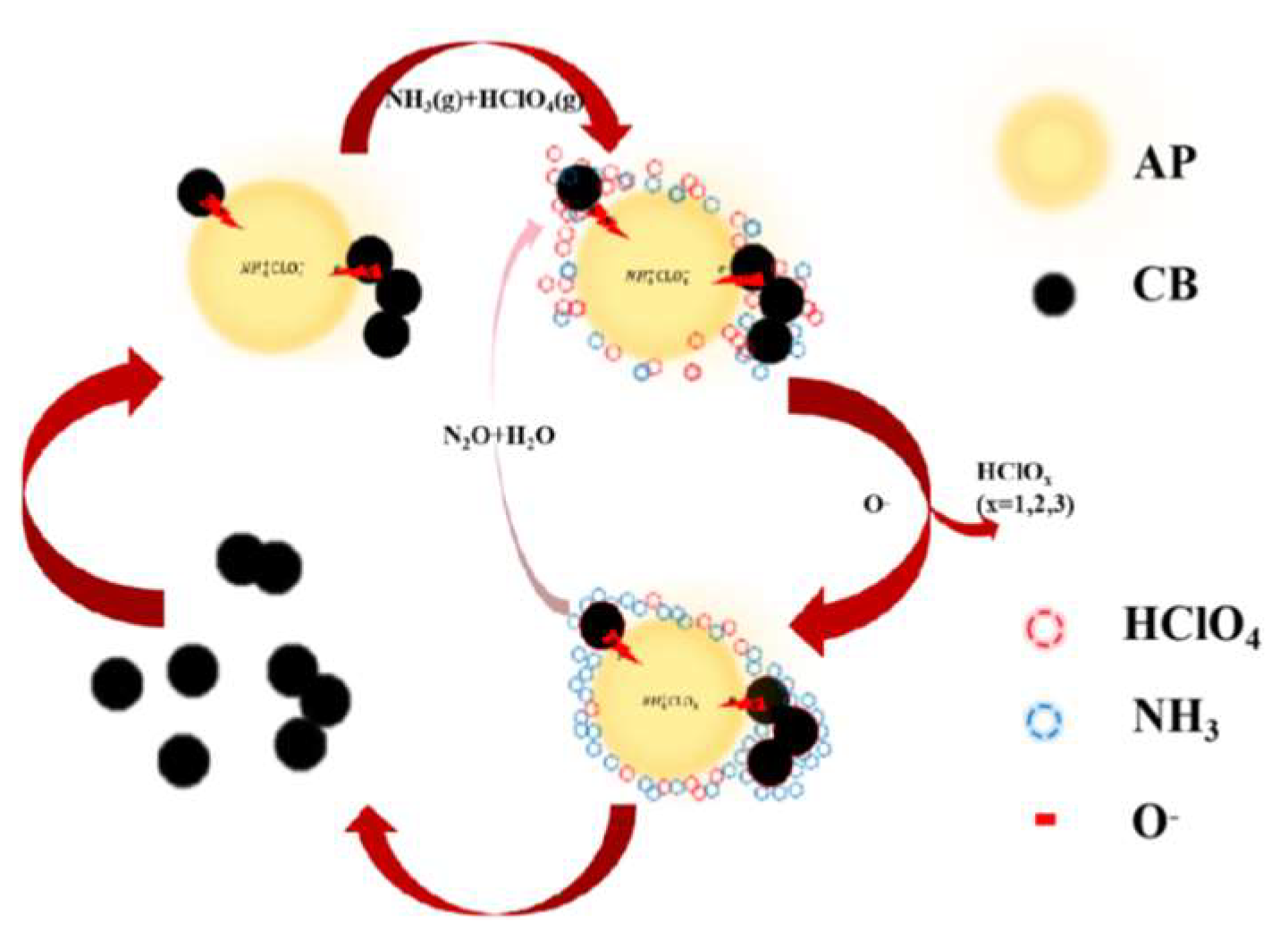

The gas phase decomposition of AP involves an electron transfer mechanism, resulting in the dissociation to produce NH

3 and HClO

4. Under low temperature conditions, NH

3 and HClO

4 adsorbed on the surface of AP crystals react, causing large crystals to fracture into multiple smaller crystals, and the reaction restarts on the surface of the small crystals, increasing the reaction surface area and accelerating the reaction rate. When the reaction centers on the surface of AP are fully covered by NH

3, NH

3 cannot be completely oxidized, and the decomposition reaction ends. Under high temperature conditions, NH

3 desorbs releasing the covered reaction centers, and the decomposition reaction restarts [

48,

49].

The solid phase AP particles are relatively small, and NH

3 will cover the crystal surface at a very fast rate, hindering the decomposition reaction, thus the low-temperature decomposition stage cannot be observed. Under high-temperature conditions, NH

3 and HClO

4 desorb into the gas phase, generating gaseous NH

3(g) and HClO

4(g). HClO

4(g) then reacts with NH

3(g) to produce the final product. It can be concluded that the controlling step of the decomposition reaction under high-temperature conditions is the gas phase reaction [

50].

From the thermal analysis structure, it can be seen that CB particles and particle aggregates have a large number of open pore structures, which are beneficial for the gas phase reaction products after AP decomposition to contact the active sites of the catalyst, thereby inducing reactions and promoting the thermal decomposition performance of AP.

Figure 8.

Thermal decomposition mechanism diagram of CB/AP composite particles.

Figure 8.

Thermal decomposition mechanism diagram of CB/AP composite particles.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the structure-activity relationship between the physicochemical properties of nine types of CB with oil absorption values, compression oil absorption values, O content, etc., in the particle size range of 1-15 μm, and catalytic pyrolysis of AP. It was found that the specific surface area, iodine absorption value, oil absorption value, and O content of CB are key factors affecting its catalytic AP pyrolysis performance. Consequently, the function relationship between oil absorption value and high-temperature peak is Y1=1032.67-9.618x+0.038x2, the function relationship between compression oil absorption value and high-temperature peak is Y2=145.537+62.365ln(x), and the function relationship between oxygen content and high-temperature peak is Y3=e(6.085-0.02/x). The correlation degree between the platform pressure index of CB samples and the structural parameters of CB is specific surface area > iodine absorption value > oil absorption value > O content. Using coal tar as raw material, five types of coal-based CB were prepared at pyrolysis temperatures of 1000-1800 ℃, and the relative error between the actual and predicted values of the high-temperature peak of CB/AP composite particles is less than 5%, proving that the CB/AP composite particle peak temperature model can guide actual production. At pyrolysis temperatures of 1000-1800 ℃, as the preparation pyrolysis temperature increases, the iodine absorption value of coal-based CB shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, while the oil absorption value roughly exhibits an S-shaped function trend with Y=e(0.952-0.089/x). Therefore, this study contributes to guiding the actual production and process optimization of CB, further promoting its application in improving the catalytic pyrolysis performance of AP and enhancing the high added value utilization of coal-derived products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: The particle size distribution and cumulative particle size distribution curve of CB(a-j); Figure S2: Particle size distribution of CB samples prepared at different cracking temperatures; Table S1: Physical and chemical analysis results of different CB; Table S2. CB/AP composite particle peak temperature model formula; Table S3. Self-made CB structural parameter model formula.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Wenjie Shao and Hailong Mei; methodology, Ziguo He; software, Hailong Mei; validation, Zhiyong Fang; formal analysis, Zhiyong Fang; investigation, Wenjie Shao; resources, Wenjie Shao; data curation, Wenjie Shao; writing—original draft preparation, Wenjie Shao; writing—review and editing, Ziguo He; visualization, Wenjie Shao; supervision, Zhiyong Fang; project administration, Ping Cui; funding acquisition, Qiang Ling, Ping Cui. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NATIONAL NATURAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION of CHINA, grant number 22004003.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (21976002), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (2008085J11), Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Universities (KJ2020A0228, 2023AH051663), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation Youth Fund (2408085QE150),Excellent Research and Innovation Team in Anhui Province (2024AH010031), Outstanding Young Teachers Cultivation Key Project (YQZD2024044), Platform Construction Collaborative Innovation Project (GXXT-2022-090), Open Research Funds of Key Laboratory of Wind Energy and Solar Energy Technology (2020ZC01), Tongling University Talent Research Initiation Fund Project (2023tlxyrc42), and Tongling University Horizontal Research Project (2024tlxyxdz052, 2024tlxyxdz054, 2024tlxyxdz065).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chaturvedi, S.; Dave, P.N. Solid propellants: AP/HTPB composite propellants. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 2061-2068.

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, X.; Tang, G.; Guo, X.; Pang, A. Differences of thermal decomposition behaviors and combustion properties between CL-20-based propellants and HMX-based solid propellants. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 140, 2529-2540. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Hu, R.; Zheng, L.; Yan, G.; Yan, W. Fabrication and investigation of 3D-printed gun propellants. Mater. Des. 2020, 192, 108761. [CrossRef]

- Assovskiy, I.G.; Kuznetsov, G.P.; Melik-Gaikazov, G.V. Energetic water compositions as rocket propellants. Acta Astronautica. 2021, 181, 643-648. [CrossRef]

- Padwal, M.B.; Castaneda, D.A.; Natan, B. Hypergolic combustion of boron based propellants. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 6703-6711. [CrossRef]

- Gallier, S.; Ferrand, A.; Plaud, M. Three-dimensional simulations of ignition of composite solid propellants. Combust. Flame. 2016, 173, 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Buchheiser, S.; Kistner, F.; Rhein, F.; Nirschl, H. Spray flame synthesis and multiscale characterization of carbon black–silica hetero-aggregates. Nanomaterials. 2023, 13(12), 1893. [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.X.; Yang, X.J.; Liu, Bo.; Song, R.D.; Xiao, F.; Yang, Y.J.; Wang, D.; Dong, M.Y.; Ren, J.; Xu, B.B.; Algadi, H.; Yang, Y.Y. Ammonium perchlorate@graphene oxide/Cu-MOF composites for efficiently catalyzing the thermal decomposition of ammonium perchlorate. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2023, 6, 67. [CrossRef]

- Kakavas-Papaniaros, P. A. On the distribution of particles in propellant solids. Acta. Mech. 2019, 231, 863-875. [CrossRef]

- Dolgoborodov, A.Y.; Streletskii, A.N.; Shevchenko, A.A.; Vorobieva, G.A.; Val’yano, G.E. Thermal decomposition of mechanoactivated ammonium perchlorate. Thermochim. Acta. 2018, 669, 60-65. [CrossRef]

- Eslami, A.; Juibari, N.M.; Hosseini, S.G. Fabrication of ammonium perchlorate/copper-chromium oxides core-shell nanocomposites for catalytic thermal decomposition of ammonium perchlorate. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 181, 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Elbasuney, S.; Yehia, M. Thermal decomposition of ammonium perchlorate catalyzed with CuO nanoparticles. Def. Technol. 2019, 15, 868-874. [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, F.; Bai, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T. New energetic complexes as catalysts for ammonium perchlorate thermal decomposition. Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 1193-1198. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Jin, B.; Hao, W.J.; Song, Y.L.; Hou, C.J.; Huang, T.; Peng, R.F. Catalytic thermal decomposition of ammonium perchlorate by a series of lanthanide EMOFs. J. Rare Earths. 2022, 41, 516-522. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, Z.Y.; Du, Z.M.; Li, Z.Y.; Cong, X.M. Preparation and performance of environmental friendly sulphur-free propellant for fireworks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 126, 987-996. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, S.F. Approach to the catalytic mechanism of fullerene in propellants. J. Energ. Mater. 2003, 21(1), 33-41.

- Ren, H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Jiao, Q.J.; Fu, X.F.; Yang, T.T. Preparation of nanocomposite PbO·CuO/CNTs via microemulsion process and its catalysis on thermal decomposition of RDX. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2010, 71, 149-152. [CrossRef]

- Sizov, V.A.; Denisyuk, A.P.; Demidova, L.A. Various carbon materials action on the burning rate modifiers of low-calorie double-base propellant. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2021, 195, 2327-2339. [CrossRef]

- Aprianti, N.; Kismanto, Agus.; Supriatna, N.K.; Yarsono, S.; Nainggolan, L.M.T.; Purawiardi, R.L.; Fariza, O.; Ermada, F.J.; Zuldian, P.; Raksodewanto, A.A.; Alamsyah, R. Prospect and challenges of producing carbon black from oil palm biomass: A review. Bioresource Technology Reports. 2023, 23, 101587. [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Zhu, M.M.; Jones, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Zhang, D.K.; An investigation into the preparation of carbon black by partial oxidation of spent tyre pyrolysis oil. Waste Manag. 2022, 137, 110-120. [CrossRef]

- Yantaboot, K.; Amornsakchai, T. Effect of preparation methods and carbon black distribution on mechanical properties of short pineapple leaf fiber-carbon black reinforced natural rubber hybrid composites. Polym. Test. 2017, 61, 223-228. [CrossRef]

- Albright, T.; Hobeck, J. Investigating the electromechanical properties of carbon black-based conductive polymer composites via Stochastic modeling. Nanomaterials. 2023, 13(10), 1641. [CrossRef]

- Albright, T.; Hobeck, J. Characterization of carbon-black-based nanocomposite mixtures of varying dispersion for improving stochastic model fidelity. Nanomaterials. 2023, 13(5), 916. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhao, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H. L-histidine-functionalized carbon black pigment with zwitterionic property: Preparation, characterization and application. Dyes Pigments. 2020, 173, 107992. [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, S. Preparation of fly-ash-modified bamboo-shell carbon black and its mercury removal performance in simulated flue gases. Energy Fuels. 2016, 30, 4191-4196. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Meng, S.; Tao, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Guan, J.; Fu, H.; Dai, C.; Liu, H. Preparation and application of modified carbon black nanofluid as a novel flooding system in ultralow permeability reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122099. [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X. Preparation of Pt catalysts supported on polyaniline modified carbon black and electrocatalytic methanol oxidation. Synth. Met. 2023, 293, 117256. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chung, D. D. L. Effect of carbon black structure on the effectiveness of carbon black thermal interface pastes. Carbon. 2007, 45, 2922-2931. [CrossRef]

- Gerspacher, M.; O’Farrell, C.P.; Nikiel, L.; Yang, H.H. Furnace carbon black characterization: continuing caga. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1996, 69(3), 569-576.

- Lockwood, F.C.; Niekerk, J.E.V.; Parametric study of a carbon black oil furnace. Combust. Flame. 1995, 103, 76-90. [CrossRef]

- Asokan, V.; Kosinski, P.; Skodvin, T.; Myrseth, V. Characterization of carbon black modified by maleic acid. Front. Mater. Sci. 2013, 7, 302-307. [CrossRef]

- Borah, D.; Satokawa, S.; Kato, S.; Kojima, T. Characterization of chemically modified carbon black for sorption application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 3049-3056. [CrossRef]

- Heidarian, J.; Hassan, A. Characterization and comparison of fluoroelastomer unfilled, filled with carbon nanotube (unmodified, acid or base surface modified) and carbon black using TGA-GCMS. J. Elastom. Plast. 2021, 53, 861-885. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.Y.; Ao, G.Y.; Kim, M.S. Properties of carbon black/SBR rubber composites filled by surface modified carbon blacks. Carbon Lett. 2007, 8, 115-119. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Guo, Q.; Shi, Z.; Pei, J. Effects of conductive carbon black on PZT/PVDF composites. Ferroelectrics. 2018, 526, 176-186. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Guel, M.; Reyes-Rodríguez, P.Y.; Cabello-Alvarado, C.J.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Ávila-Orta, C.A. Influence of modified carbon black on nylon 6 nonwoven fabric and performance as adsorbent material. Nanomaterials. 2022, 12(23), 4247. [CrossRef]

- Prioglio, G.; Naddeo, S.; Giese, U.; Barbera, V.; Galimberti, M. Bio-based pyrrole compounds containing sulfur atoms as coupling agents of carbon black with unsaturated elastomers. Nanomaterials. 2023, 13(20), 2761. [CrossRef]

- Klyne, R.A.; Simpson, B.D.; Studebaker, M.L. A comparison of methods for determining surface areas of carbon black. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1973, 46(1), 192-203. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, H.N.; Boyer, A.H.; Bhusky, P.L.; Deviney, M.L. The third dimension of carbon black structure. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1976, 49(4), 1068-1075. [CrossRef]

- Voet, A.; Aboytes, P. Measurement of chain structure in carbon blacks. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1970, 43(6), 1359-1366. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, H.; Dasappa, S.; Sabado, K. D.; Camacho, J. Production of carbon black in turbulent spray flames of coal tar distillates. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11(21), 10001. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.G.; Chung, D.D.L. Effect of carbon black structure on the effectiveness of carbon black thermal interface pastes. Carbon. 2007, 45, 2922-2931. [CrossRef]

- Goeringer, S.; Tacconi, N.R.D.; Chenthamarakshan, C.R.; Rajeshwar, K.; Wampler, W.A. Redox characterization of furnace carbon black surfaces. Carbon. 2001, 39, 515-522. [CrossRef]

- Ishola, F.A.; Inegbenebor, A.O.; Oyawale, F.A. Thermal modelling for a pilot scale pyrolytic furnace for production of carbon black. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1378, 032089. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Ni, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X. Boosting the ORR performance of modified carbon black via C-O bonds. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2118-2123.

- Zhao, G.; Liang, L.H.; Lv, D.F.; Ji, W.J.; You, Q.; Dai, C.L. A novel nanofluid of modified carbon black nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery in low permeability reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 1598-1607. [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Yanaka, M.; Tanaka, S.; Saito, Y.; Aoki, H.; Fukuda, O.; Aoki, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Influence of furnace temperature and residence time on configurations of carbon black. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 200-202, 541-548. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Wang, Z.H.; Liang, H.W.; Wu, R.; Lei, Zhao.; Zhao, Z.G.; Ke, Q.P.; Xie, R.L.; Liu, X.C.; Zhang, N.; Cui, P. Fluorinated graphene and its catalytic performance for AP pyrolysis: the promotion of F doping. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2023, 31(9), 888-896.

- Wang, C.A.; Xu, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, R.; Ye, Y. Probing the reaction mechanism of Al/CuO nanocomposites doped with ammonium perchlorate. Nanotechnology. 2020, 31, 255401. [CrossRef]

- Bernigaud, P.; Davidenko, D.; Catoire, L. A revised model of ammonium perchlorate combustion with detailed kinetics. Cobust. Flame. 2023, 255, 112891. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).