1. Introduction

The meningioma embolization procedure was first described more than 50 years ago by a team of French researchers led by Manelfe et al. [

1]. Despite a long history of use of this technique, and the obvious benefits of preoperative embolization in "softening" the tumor and reducing blood loss during resection, the outcomes remain controversial [

2]. Along with the positive effects of occlusion of the middle meningeal artery (MMA), there are potential complications such as bleeding and stroke [

2,

3]. Due to these risks, endovascular embolization of meningiomas is not routinely used and remains an optional procedure. However, there is evidence of successful use of embolization as an independent method of treatment, leading to up to a 60% reduction in meningioma size [

4]. In 2024, a complete resolution of a meningioma was reported 2 years after bilateral embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA)performed for chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH) using a non-adhesive composition [

5].

Several authors suggest a possible link between migraines and meningiomas [

6,

7,

8], noting in their observations that migraine pain disappeared after successful treatment for this neoplasm. In addition to the positive results of MMA embolization in treating meningiomas and CSDH, some reports in the current literature describe a decrease in headache intensity after MMA embolization in patients with CSDH and migraines. However, there are currently no reports of a decrease in migraine pain intensity after MMA embolization specifically for meningiomas.

The above clinical observation shows a decrease in the frequency and intensity of chronic migraines, as well as the complete resolution of small meningiomas, after embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA)and its branches. This case study was conducted in accordance with the CARE guidelines. [

9,

10]

2. Case Presentation

A 49-year-old european patient with a parasagittal meningioma in the left frontoparietal region admitted to Vascular Neurosurgery Department, Polenov Neurosurgical Research Institute in May 2023. In addition to the primary diagnosis, the patient had the following comorbid conditions: diffuse toxic goiter, which was managed with hormone replacement therapy (L-thyroxine 100 micrograms), resulting in euthyroidism; a condition following radioiodinetherapy on 2015; bronchial asthma; a polyallergic condition; and surgical menopause since 2021 following extirpation of the uterus and ovaries due to adenomyosis.

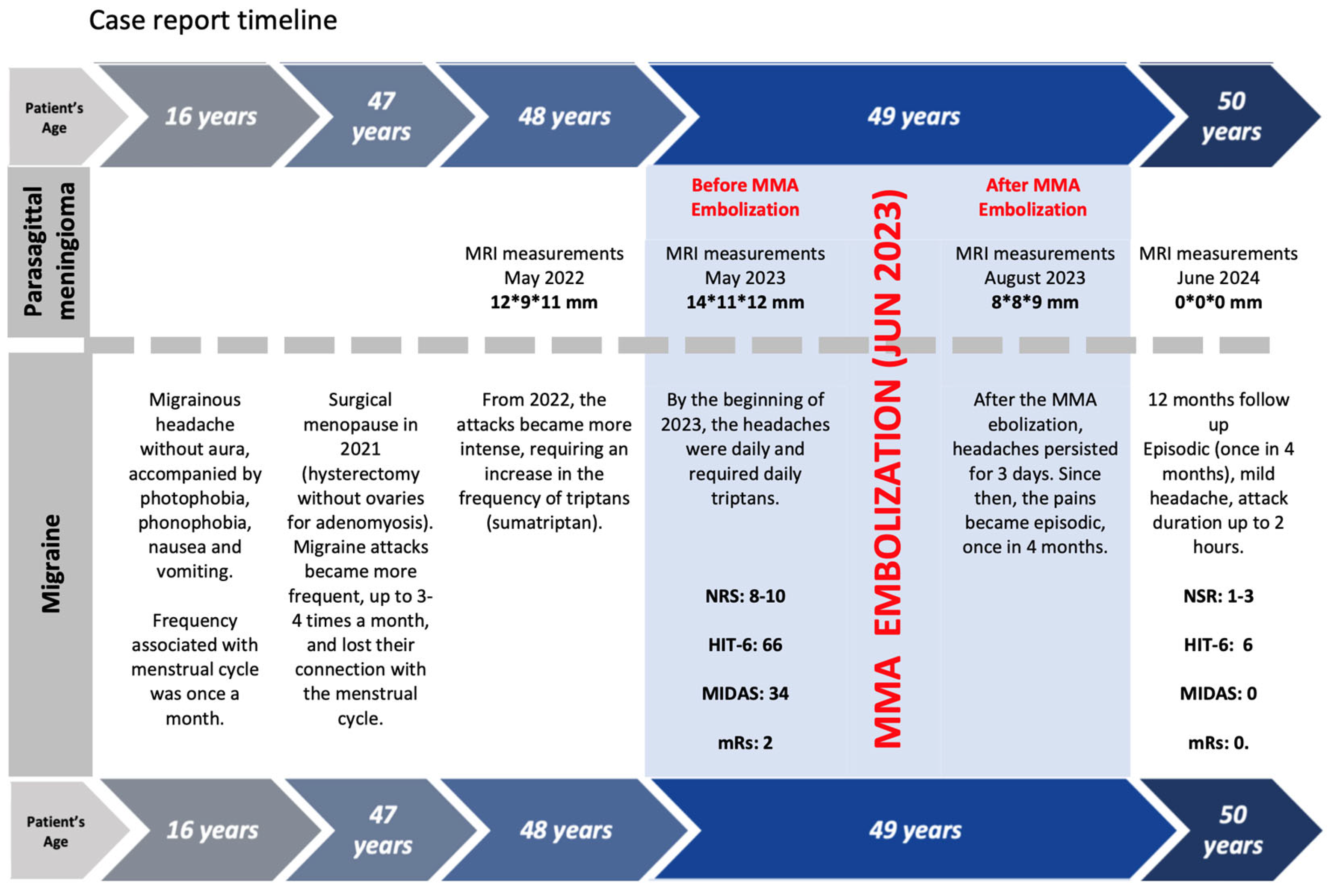

The patient’s medical history does not include any mentions of hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, or type 2 diabetes. She had no smoking or alcohol consumption history, and her tolerance for physical activity was good. In addition to the aforementioned concurrent pathology, the patient had experienced migraine headaches since the age of 16. The headaches were without aura and were accompanied by photophobia, nausea, and vomiting. Prior to2021, migraine attacks were associated with the menstrual cycle.After surgical menopause occurred, from 2022 headache attacks became more severe and required an increase in triptan intake frequency (A migrenin and Sumatriptan). By the beginning of 2023, headaches had become daily and required daily triptan administration. According to the criteria of the European Headache Federation, this course could be classified as chronic migraine.

During the brain MRI in May 2022, a small parasagittal meningioma (12.9 x 11 mm) was detected in the left frontal region without brain compression or perifocal edema, and it was not invading the upper sagittal sinus.

Figure 1a,b provide a visual representation of this finding.

Considering the size of the lesion and the absence of any perifocal complications, radiosurgical treatment was recommended using the Lexell Gamma Knife. However, the patient declined radiation therapy. A repeat MRI scan of the brain conducted in May 2023 (

Figure 1 c and d) showed an increase in the size of the lesion by 2 millimeters (14*11*12 mm). The patient continued to decline radiation therapy, and therefore, the medical expert panel recommended proceeding with the first stage of embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) and its branches with a follow-up. And to perform surgical removal of the tumor if it would be necessary.

At the time of admission, the patient’s overall condition was considered satisfactory. Weighed 58 kilograms and 170 centimeters tall, with a body mass index of 20.1, indicating a good level of physical stability. There were no neurological deficits noted. However, the main complaints of the patient were related to daily migraine headaches, which were rated between 8 and 10 on a numerical rating scale (NRS), causing a decrease in the patient’s quality of life. This was evident by a headache impact index (HIT-6) score of 66, indicating a significant impact. Assessment of the effect of migraines on daily activities using the MIDAS (Migraine Disability Assessment) scale resulted in a score of 34, corresponding to severe pain, significantly reducing daily activities. As a result, the patient was unable to attend work and perform household chores, resulting in a modified Rankin Scale(mRs) score of 2.

In June 2023, a procedure known as embolization was performed on the left middle meningeal artery (L-MMA) and its branches. This procedure involved the use of a combination of different non-adhesive materials with varying viscosities, including Squid 12 and Squid 18, to achieve the desired result. The embolic agent, which was chosen due to its low viscosity and good performance in previous MMA embolizations, successfully distributed [

11,

12,

13,

14] itself through out the arteries, reaching both collateral vessels on the opposite side and the dural venous system. This distribution was achieved through a careful and precise application of the material, ensuring that it reached all necessary areas while minimizing any potential complications.

2.1. Meningioma Embolisation

Under general anesthesia, a right femoral transarterial approach was performed. A 7F introducer was inserted, and 2.5 milliliters of heparin solution was administered. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was then performed from the right and left internal carotid arteries, external carotid arteries, and the right vertebral artery to reveal the vascular network of the tumor in the left frontal region. Afferent vessels were found to originate from the frontal and parietal branches of the left middle meningeal artery (MMA)and also from collateral vessels from the opposite (right)MMA (

Figure 2a,b). A 7 Fr Guide Softip guiding catheter (Boston Scientific) was inserted in to the left external carotid artery, and the frontal branch of the left MMA was catheterized distally using a Headway 17 microcatheter (MicroVention) with a guide wire Asahi Chikai 0.010-inch (Asahi Intecc).

Figure 2c,d show DSA images obtained through the microcatheter. Embolization was performed using non-adhesive, minimally viscosity Squid 12 (Balt) material, with an injection volume of 0.6 mL. The distribution of the embolic agent after the initial injection is shown in

Figure 2e,f. After achieving the limit of the embolic agent’s penetration into the tumor vascular system through this afferent pathway, the microcatheter was removed and the ipsilateral parietal branch of the MMA was catheterized, followed by DSA (

Figure 2g,h). Partial contrast was observed in the remaining vascular network of the lesion from this afferent artery. The tip of the microcatheter was positioned as distally as possible along the ipsilateral parietal MMA. With this positioning, a second injection of Squid 12 (Balt) was administered, which extended well into collateral vessels, including the contralateral MMA. However, the injection was halted when the embolic material started to spread into dural veins and the injection volume was increased to 0.7 mL (

Figure 2i,j). Then, the embolic agent with the lowest viscosity was substituted with a standard viscosity (Squid 18 (Balt)), which was administered in a volume of 0.4 mL. In the craniograms without subtraction, the embolized area is clearly visible, reproducing the afferent blood supply of the vascular network of the tumor (

Figure 2k,l). Therefore, during the embolization procedure, the dura mater was extensively deprived of blood vessels on both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides.

2.2. Outcomes and Follow-Up

Two months after embolization, a follow-up MRI of the brain showed a reduction in the size of the meningioma to 8x8x9 mm (

Figure 3a,b). Complete resolution of the tumor was observed on MRI one year later (

Figure 3c,d).

For the first 3 days after the embolization procedure, the patient experienced severe headaches, which resolved within 5 days. After that, the pain has become episodic, occurring only once every 4 months. The patient did not often experience headaches and had not noticed them in a long time. During a follow-up exam 12 months after the embolization of the MMA, the patient reported a significant decrease in the frequency and intensity of migraines, which became mild and quickly relieved by taking triptans. The duration of these episodes was up to 2 hours and the intensity was up to 3 on the scale. Headaches occurred very rarely, once in 4 months and were almost unnoticeable. The patient’s MRI scan showed a decrease in the size of the parasagittal meningioma in the left frontal region, and the characteristics of the migraine headaches are presented in

Figure 4.

2.3. Patient Perspective

"I am very grateful that I chose the embolization method for the treatment of my meningioma. This method not only allowed me to get rid of the tumor, but also of headaches. I remember the day before surgery, when I had an attack of migraine. Perhaps hunger was the trigger. I also experienced headaches due to hunger (but now I can comfortly starve all the day), but I was taken for surgery after 5 pm. I realized that if I didn’t have it now, I didn’t know when surgery would take place. I hoped anesthesia would help, but the headache didn’t go away after surgery, plus some throbbing joined in, and flashes of lightning appeared in my head. After 2-3 days, everything was gone. Now,I can say that my life is divided into "before"and "after". I lead an active life style and do not experience difficulties at work or in daily activities.".And the "constant companion", Amegrinin, has disappeared from my purse. I would like to thank you for the opportunity to enjoy life.”

3. Discussion

Meningioma embolization is a treatment option that can be used before surgical removal of the tumor [

15] or as the first step before radiosurgery with a gamma knife [

16,

17]. However, this procedure is not widely used due to the risk of complications. The incidence of complications after preoperative embolization for meningioma varies from 21% in older studies to 6% in more recent studies where more advanced techniques were used [

2,

3,

18,

19].

The main adverse events associated with embolization include hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsy, tumor edema, ischemia, hemorrhage, and necrosis in the scalp. Other minor neurological complications may include headache, dizziness, and vomiting. In addition, there are other undesirable phenomena that are not directly related to MMA embolization but are related to common complications of endovascular procedures, such as the formation of a hematoma or an arteriovenous fistula in the vascular access area [

3]. A more controversial issue is the possibility of using meningioma embolization as an independent method for tumor control and treatment. There have been isolated observations [

4,

20] and small case series that have shown a decrease in meningioma volume after embolization ranging from 10%to 70% [

21], and even one case of complete resolution [

5]. However, to date, only one clinical trial has been conducted on the topic of therapeutic embolization for meningiomas [

22], and itis currently recruiting participants. Nevertheless, the widespread use of non-adhesive embolizing materials in clinical practice, with their high degree of penetration and good control, opens up new opportunities for solving this problem [

23]. In our case, we initially used meningioma embolization as an independent treatment option to control its growth and reduce its volume. We achieved complete resolution of the tumor within a year. Although the limited observation period does not allow us to draw a definitive conclusion about a complete cure, it demonstrates the potential of embolization with non-adhesive materials as a treatment option. Due to the small size of the meningioma, the patient was not a candidate for surgical removal. However, the tumor’s growth over the year prompted us to seek alternative treatments.

In our case, the meningioma had multiple feeders, both from the ipsilateral (same side) and contralateral (opposite side) middle meningeal arteries (MMA), which required a sufficiently wide dissection of the dura mater on both sides. We propose that the widespread dissection of dura was associated with relief of chronic migraines, as observed in the patient after the procedure over the course of a year. It is known that dura arteries play a significant role in the development of migraine headaches. Many researchers have noted that migraine triggers could be vasodilators, while most effective treatments(triptans) for migraines are vasoconstrictors. [

24] According to researchers, the constriction of vessels in the meninges and brain may contribute to the effects of medications used to relieve migraine attacks [

25]. In our case, we noticed that it was the steadily increasing doses of triptans that helped to prevent headache attacks. However, after embolization, they were needed only sporadically every 4 months.

The significance of the dural blood flow in the development of migraine headaches is also indirectly supported by the fact that migraines disappear after MMA surgery, as described in the literature. Thus, in 10 patients aged 29to 70 with prolonged severe migraines, MMA ligation and disruption of the large superficial nerve contributed to the relief of headaches and long-term remission of the disease for up to 18 years after treatment [

26].

A prospective study of migraines in patients after surgery for an aneurysm clipping compared to endovascular occlusion using coils for acute subarachnoid hemorrhage found that stopping blood flow through the middle meningeal artery (MMA)and dissecting the concomitant branches of the trigeminal nerve significantly and permanently relieved migraine headaches after surgery [

27].

After the diagnosis of acute subarachnoid hemorrhage, 21 patients underwent surgical clipping and 12 underwent endovascular occlusion with coils. For surgical clipping, a frontotemporal craniotomy was performed, including coagulation and division of the MMA and its branches during dural opening. Patients who underwent endovascular occlusion served as a control group. After craniotomy, 77.4% of patients who initially experienced migraines reported no longer having migraine headaches, while19.4% experienced a reduction in headache frequency of more than 50%. Among patients who did not receive craniotomy, 46.7% reported no further migraines, and 20% experienced a decrease in attack frequency by more than 50%.

Limitations of this study include the lack of randomization, loss of some follow-up patients, and retrospective nature of the migraine data. Additionally, some patients may have had cognitive impairments that affected their ability to provide accurate information. Despite these limitations, the findings suggest a potential role for MMA in reducing pain symptoms associated with migraines.

Headache after MMA embolization was also assessed among migraine patients who underwent this procedure to eliminate chronic subdural hematomas [

28]. Of the 9 patients aged 45 to 77 who had headaches for at least 2 years prior to surgery with a frequency of at least 2 days per month, 8 experienced improvements in their headache, and 7 had complete resolution. The average score on the HIT-6 questionnaire after surgery was significantly lower than before, indicating a reduction in headache severity.

There is a category of patients who do not respond well to standard migraine medication. In these cases, migraine is said to be resistant or refractory [

29,

30]. Chronic migraines can significantly disrupt normal functioning and lead to the overuse of painkillers, which can contribute to mental health issues such as depression [

31].

Refractory and resistant migraines are severe forms of the condition, and there are many unanswered questions about them. The main challenge for the patients is that standard anti-migraine medications are either ineffective or have minimal impact, whether for preventing seizures or relieving them in the case of refractory migraines, or when at least three different types of preventive medications are ineffective or not tolerated in the case of resistant migraines. According to surveys conducted among doctors at specialized headache treatment centers in Europe, the United States, and Asia, approximately75% of doctors often encounter patients with resistant migraines in their practice [

32]. Experts estimate that in 3-14% of patients with episodic migraines, the condition progresses and becomes a chronic daily headache [

33]. This was also observed in the case of our patient.

To assist these patients, the effectiveness of microsurgical procedures for decompressing nerves in the frontal, temporal, and occipital areas of the head, which are associated with migraine pain foci, was considered [

34,

35]. In a study conducted by Pietramaggiori et al., microsurgical surgery was performed to decompress the auricular nerve and superficial temporal artery in 57 patients with temporal region migraines that were resistant to drug treatment [

36].

Against this background, the study "Efficacy and Safety of Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization for Treatment of Intractable Migraine" (FAST-EM) [

37], conducted in China, looks very interesting. In this study, detachable coils were used as an embolic agent.

To date, the data collected in the framework of this research is limited. However, based on these data, it can be assumed that migraines may become less severe or disappear after the blood flow through the MMA is interrupted. One of the modern and safe methods for such an intervention is embolization of the MMA with non-adhesive compositions. [

11,

12,

38].

The above clinical observation suggests that embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA)with non-adhesive materials can lead to both the resolution of small meningiomas and the relief of chronic migraines, as well as improvement in the quality of life for patients. We assume that this effect was achieved through the widespread and deep distributions of embolic agent of various viscosities in the middle meningeal artery branches ipsilateral and contralateral to the meningioma.

5. Conclusions

Embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA)and the vascular network surrounding meningioma has the potential to lead to complete resolution of the tumor and may be an effective treatment option. This procedure has been shown to provide relief from chronic migraine and improve the quality of life for patients. However, due to a lack of sufficient data in the current literature, further research is needed. It is important to consider this potential side effect and conduct studies on the efficacy of MMA embolization both for treating meningiomas and chronic migraines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. (Andrey Petrov) and A.I.; data curation, E.S., A.I., A.P. (Andrey Petrov), A.I. and A.P. (Anna Petrova); formal analysis, J.S., and A.P. (Anna Petrova); investigation, A.P. (Andrey Petrov), A.P. (Anna Petrova) and A.I.; methodology, L.R., K.S.; project administration, A.I. and A.P. (Andrey Petrov); supervision, L.R. and A.P. (Andrey Petrov); writing—original draft, A.P. (Andrey Petrov), J.S., and A.I.; writing—review and editing, E.S., A.P. (Andrey Petrov), A.I. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from subject involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of the patients who assisted in the research.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Manelfe, C.; Guiraud, B.; David, J.; Eymeri, J.C.; Tremoulet, M.; Espagno, J.; Rascol, A.; Géraud, J. [Embolization by Catheterization of Intracranial Meningiomas]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1973, 128, 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Singla, A.; Deshaies, E.M.; Melnyk, V.; Toshkezi, G.; Swarnkar, A.; Choi, H.; Chin, L.S. Controversies in the Role of Preoperative Embolization in Meningioma Management. Neurosurg. Focus. 2013, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumah, F.; AbuRmilah, A.; Raju, B.; Jaber, S.; Adeeb, N.; Narayan, V.; Sun, H.; Cuellar, H.; Gupta, G.; Nanda, A. Does Preoperative Embolization Improve Outcomes of Meningioma Resection? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 3151–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, T.; Sasaki, O.; Tanaka, R.; Arai, H. Long-Term Results in a Case of Meningioma Treated by Embolization Alone--Case Report. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 1990, 30, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, E.; Larson, E.; Tierney, M.; Elias, A.E.; Figueroa, B.E.; Siddiqui, F.M.; Pandey, A.S. Complete Meningioma Resolution Following Endovascular Embolization of Chronic Subdural Hematoma. J. Neurointerv Surg. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Yamane, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Sato, K.; Yamaguchi, K. [A Case of Migraine with Aura Associated with Meningioma]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 1993, 33, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.W.; Timm, J.S.; Baskin, D.S. A Left Frontal Secretory Meningioma Can Mimic Transformed Migraine With and Without Aura. Headache 2015, 55, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meningioma Mimicking Late-Onset Migraine with Sensory Aura. Headache 2004, 44, 289. [CrossRef]

- Riley, D.S.; Barber, M.S.; Kienle, G.S.; Aronson, J.K.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Tugwell, P.; Kiene, H.; Helfand, M.; Altman, D.G.; Sox, H.; et al. CARE Guidelines for Case Reports: Explanation and Elaboration Document. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rison, R.A. A Guide to Writing Case Reports for the Journal of Medical Case Reports and BioMed Central Research Notes. J. Med. Case Rep. 2013, 7, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, A.; Ivanov, A.; Rozhchenko, L.; Petrova, A.; Bhogal, P.; Cimpoca, A.; Henkes, H. Endovascular Treatment of Chronic Subdural Hematomas through Embolization: A Pilot Study with a Non-Adhesive Liquid Embolic Agent of Minimal Viscosity (Squid). J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, A.E.; Rozhchenko, L.V.; Ivanov, A.A.; Bobinov, V.V.; Henkes, H. The First Experience of Endovascular Treatment of Chronic Subdural Hematomas with Non-Adhesive Embolization Materials of Various Viscosities: Squid 12 and 18. Voprosy neirokhirurgii imeni N.N. Burdenko 2021, 85, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, A.; Ivanov, A.; Dryagina, N.; Petrova, A.; Samochernykh, K.; Rozhchenko, L. Angiogenetic Factors in Chronic Subdural Hematoma Development. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, A.; Kashevnik, A.; Haleev, M.; Ali, A.; Ivanov, A.; Samochernykh, K.; Rozhchenko, L.; Bobinov, V. AI-Based Approach to One-Click Chronic Subdural Hematoma Segmentation Using Computed Tomography Images. Sensors 2024, 24, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mufti, F.; Gandhi, C.D.; Couldwell, W.T.; Rybkin, I.; Abou-Al-Shaar, H.; Dodson, V.; Amin, A.G.; Wainwright, J.V.; Cohen, E.; Schmidt, M.H.; et al. Preoperative Meningioma Embolization Reduces Perioperative Blood Loss: A Multi-Center Retrospective Matched Case-Control Study. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 37, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Suda, Y.; Fushimi, S.; Shibata, K.; Kondo, R.; Oda, M.; Shimizu, H. Endovascular Stenting Following Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Meningioma Involving the Superior Sagittal Sinus. J. Neuroendovascular Ther. 2020, 14, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, T.; Yokote, H.; Tsuura, M.; Kinoshita, Y.; Takehara, R.; Kubo, K.; Nakai, K.; Itakura, T. Presumed Intraventricular Meningioma Treated by Embolisation and the Gamma Knife. Neuroradiology 1999, 41, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubel, G.J.; Ahn, S.H.; Soares, G.M. Contemporary Endovascular Embolotherapy for Meningioma. Semin. Intervent Radiol. 2013, 30, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaka, H.; Sakata, K.; Tatezuki, J.; Shinohara, T.; Shimohigoshi, W.; Yamamoto, T. Safety and Efficacy of Preoperative Embolization in Patients with Meningioma. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2018, 79, S328–S333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, D.; Singh, V. A Sphenoid Wing Meningioma Presenting with Intraparenchymal and Intraventricular Hemorrhage Treated with Endovascular Embolization Alone: Case Report and Radiologic Follow-Up. J. Neurointerv Surg. 2012, 4, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, N.; Fukuda, H.; Adachi, H.; Sasaki, N.; Yamaguchi, M.; Mitsuno, Y.; Kitagawa, M.; Horikawa, F.; Murao, K.; Yamada, K. Long-Term Volume Reduction Effects of Endovascular Embolization for Intracranial Meningioma: Preliminary Experience of 5 Cases. World Neurosurg. 2017, 105, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embolization for Meningioma (e-Men) (ClinicalTrials.Gov ID NCT05416567)). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05416567?cond=Meningioma&intr=Embolization&rank=1&tab=history (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Petrov, A.; Ivanov, A.; Kolomin, E.; Tukanov, N.; Petrova, A.; Rozhchenko, L.; Suvorova, J. The Advantages of Non-Adhesive Gel-like Embolic Materials in the Endovascular Treatment of Benign Hypervascularized Lesions of the Head and Neck. Gels 2023, 9, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J. Personal View: Modelling Pain Mechanisms of Migraine without Aura. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benemei, S.; Cortese, F.; Labastida-Ramírez, A.; Marchese, F.; Pellesi, L.; Romoli, M.; Vollesen, A.L.; Lampl, C.; Ashina, M. School of Advanced Studies of the European Headache Federation (EHF-SAS) Triptans and CGRP Blockade—Impact on the Cranial Vasculature. J. Headache Pain. 2017, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Fan, Z.; Wang, H. New Surgical Approach for Migraine. Otol. Neurotol. 2006, 27, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdueza, J.M.; Dreier, J.P.; Woitzik, J.; Dohmen, C.; Sakowitz, O.; Platz, J.; Leistner-Glaess, S.; Witt, V.D. Course of Preexisting Migraine Following Spontaneous Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 880856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catapano, J.S.; Karahalios, K.; Srinivasan, V.M.; Baranoski, J.F.; Rutledge, C.; Cole, T.S.; Ducruet, A.F.; Albuquerque, F.C.; Jadhav, A.P. Chronic Headaches and Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization. J. Neurointerv Surg. 2022, 14, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, E.A.; Lake, A.E.; Goadsby, P.J.; Peterlin, B.L.; Siegel, S.E.; Markley, H.G.; Lipton, R.B. Defining Refractory Migraine and Refractory Chronic Migraine: Proposed Criteria from the Refractory Headache Special Interest Section of the American Headache Society. Headache 2008, 48, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, S.; Braschinsky, M.; Ducros, A.; Lampl, C.; Little, P.; van den Brink, A.M.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Reuter, U.; de la Torre, E.R.; Sanchez Del Rio, M.; et al. European Headache Federation Consensus on the Definition of Resistant and Refractory Migraine: Developed with the Endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance (EMHA). J. Headache Pain. 2020, 21, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwart, J.-A.; Dyb, G.; Hagen, K.; Ødegård, K.J.; Dahl, A.A.; Bovim, G.; Stovner, L.J. Depression and Anxiety Disorders Associated with Headache Frequency. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2003, 10, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, S.; Lampl, C.; Maassen van den Brink, A.; Caponnetto, V.; Braschinsky, M.; Ducros, A.; Little, P.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Reuter, U.; Ruiz de la Torre, E.; et al. Burden and Attitude to Resistant and Refractory Migraine: A Survey from the European Headache Federation with the Endorsement of the European Migraine & Headache Alliance. J. Headache Pain. 2021, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarava, Z.; Schneeweiss, S.; Kurth, T.; Kroener, U.; Fritsche, G.; Eikermann, A.; Diener, H.-C.; Limmroth, V. Incidence and Predictors for Chronicity of Headache in Patients with Episodic Migraine. Neurology 2004, 62, 788–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposio, G.; Raposio, E. Principles and Techniques of Migraine Surgery. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 6110–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olla, D.R.; Kemper, K.M.; Brown, A.L.; Mailey, B.A. Single Midline Incision Approach for Decompression of Greater, Lesser and Third Occipital Nerves in Migraine Surgery. BMC Surg. 2022, 22, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietramaggiori, G.; Bastin, A.; Ricci, F.; Bassetto, F.; Scherer, S. Minimally Invasive Nerve and Artery Sparing Surgical Approach for Temporal Migraines. JPRAS Open 2024, 39, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficacy and Safety of Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization for Treatment of Intractable Migraine (FAST-EM) (ClinicalTrials.Gov ID NCT06029153). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06029153?cond=Embolization%20%20Migraine&rank=1 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- IP1887 [IPG779] IP Overview: Middle Meningeal Artery Embolisation for Chronic Subdural Haematomas Interventional Procedure Overview of Middle Meningeal Artery Embolisation for Chronic Subdural Haematomas Contents; 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).