1. Introduction

Water along with cement are the world’s two most consumed materials. Self-sensing cement-based materials are currently at the frontier of the research on Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) and damage detection of concrete and masonry structures [

1,

2,

3]. Self-sensing mortars and concretes can self-measure their strain conditions thus providing key information for SHM [

4]. They can be fabricated through dispersing conductive fillers or fibers into composite materials exploiting the filler’s capability to monitor the mechanical strain with electrical resistance variation [

5,

6,

7]. Carbon nanotubes, carbon nanofibers, graphene oxide and other carbon-based fillers are nowadays the best candidates for this application due to the long-term durability, reliability and good performance in cement-based pastes [

8,

9,

10]. However, the sensing mechanism of these carbon nanomaterials relies on electron transport, which leads to significant challenges. Temperature fluctuations and other environmental factors often cause resistivity variations that exceed those induced by strain, complicating the signal processing [

11,

12]. Other issues related to the use of carbon-based fillers for sensing applications are associated to the difficult dispersion of the inclusions in a water-based admixture, as cement-based ones: the occurrence of bundles or agglomerations could determine nucleation points and weak areas of initiation of cracks or reduced strength [

13,

14]. The homogeneity of the material and the easiness of the production at different scales, up to the real ones, are crucial, essential and mandatory for the effective use of this innovative monitoring approach in constructions [

15]. Regenerated silk fibroin (SF) is one of most studied biomaterials, which considering the most common redissolution method of such polypeptide in water and metal ions (Ca

2+) inspired scientists to develop soft ionic conductors [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Regenerated SF prepared by the dissolution in formic acid (FA) with the addition of calcium chloride (CaCl

2) exhibits the silk I secondary structure, which rapidly dissolves in water. In SF films prepared from Ca

2+/FA solution Ca

2+ ions can capture water from the atmosphere coordinating and trapping water molecules via the oxygen atoms [

16,

20]. Moreover, the secondary structural change of SF controls the sol-gel transition from a disordered state in solution to a

-sheet-rich conformation in the gel state. Thus, despite the silk I and silk II secondary conformation, it is possible to obtain SF hydrogels with a high content of water molecules.

Ionic-conductive hydrogels are perfectly suited for integration in multifunctional structures because of their liquid-like transport behavior and solid-like mechanical properties [

21]. The movements of ions in a fluid material (e.g. ionic liquids) are found to be responsible for a capacitive and resistive switching behavior [

22,

23]. Cement mortars that naturally combine water and cement via hydration reaction can be used to dissolve water soluble SF leading to the formation of Ca ions paths. The polymorphic nature of SF indicated that the silk I structure is the key secondary structure that promotes the dissolution of SF for the regeneration of (i) water stable and ionic conductor silk biomaterials with

-sheet content, making them processable to obtain (ii) cement mortar composites. In this study, we developed water-soluble SF films containing Ca

2+ ions, which can be directed towards the electrodes, and used them to fabricate SF-cement mortars (SFm). We then introduced this novel cement-based composite, highlighting its significant piezoresistive and piezocapacitive properties, which make it highly suitable for self-strain-sensing in concrete and masonry structures. Finally, we demonstrated the memcapacitive state of these cement mortar composites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of SF Solutions

Silk cocoons were supplied by a local farm (Fimo srl, Milano, Italy). Black phosphorous, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), CaCl

2, FA and NaHCO

3 were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. Silk solutions were prepared as reported elsewhere [

24]. Briefly, silk cocoons were degummed with NaHCO

3 and dispersed into 5 ml FA/CaCl

2 solution (CaCl

2 was in weight ratio of 70/30 with respect to the silk amount (0.70 g)). SF films were produced by leaving the SF solutions to evaporate onto Petri dishes overnight with subsequent annealing at 40°C for 2 hours. SF films were stirred and dissolved in PBS 1X (pH 7.4) with a concentration of 50, 100 and 200 mg/ml, respectively. SF films were produced by leaving the SF solutions to evaporate onto Petri dishes for 12 hours. To monitor sol-gel transition, the SF solutions prepared at different concentrations were cast into optically transparent bottles separately, followed by a resting times of 0, 2, 24, 168 and 720 hours. The sol–gel transition was determined when the sample vial appeared white and did not flow from the vial wall [

25].

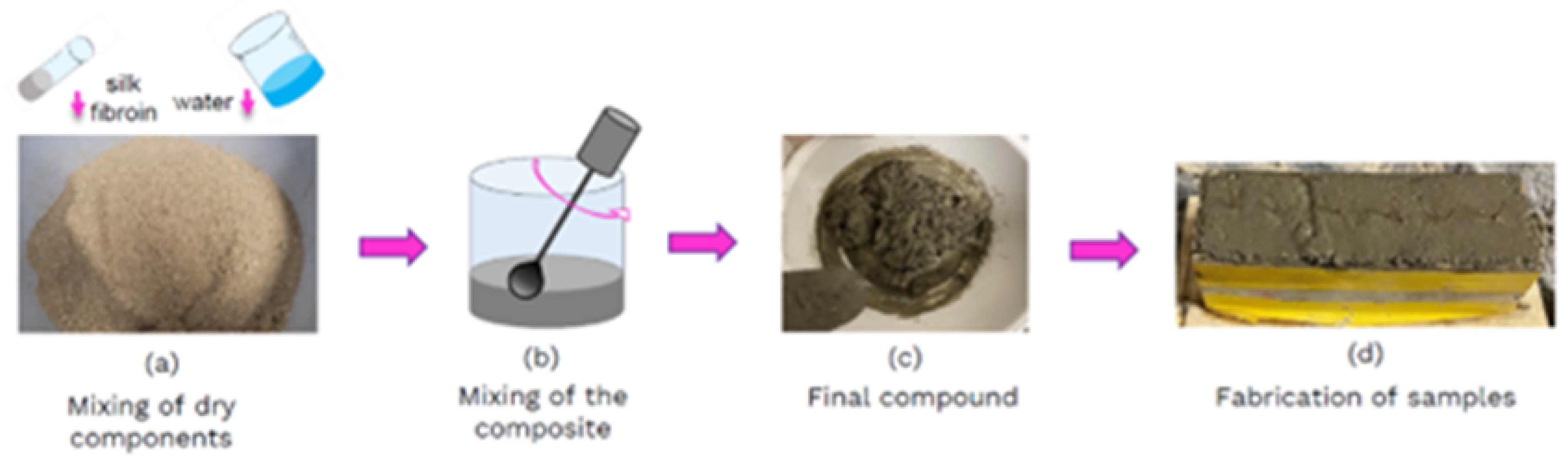

2.2. Preparation of the SF-Cement Mortars

The SF was added to normal cement mortars constituted by Portland cement type 42.5R, quarry aggregates (sized 0 ÷ 4 mm), and water. The dry components were initially mixed (

Figure 1a), then the SF solutions, with different SF concentrations, and the water were added to obtain a composite material with suitable workability properties (

Figure 1b). The compositions of the prepared samples are reported in

Table 1. The sand volume was 3.5 time the cement volume, as common mortar composites used in the field of construction engineering [

5]. The water-to-cement ratio (w/c) of 0.5 was adopted for all the mixes.

After a mixing time of about five minutes (

Figure 1c), standard cubes with the side of 4 cm were casted with the final mixtures, and two copper wires with a diameter of 0.8 mm embedded for 3/4 of the height, at a distance of 20 mm (

Figure 1d). The samples were cured at laboratory conditions for 28 days before electrical and electromechanical testing.

2.3. Characterization of SF Solutions

Infrared spectra were recorded using a Fourier transform spectrometer from Jasco equipped with its diamond ATR (attenuated total reflection) module. The spectra were recorded in the 4000-400 cm−1 spectral range at a resolution of 2 cm−1. Each measured spectrum was averaged from 300 scans. A background spectrum without a sample was acquired using the same number of scans before each measurement. Spectral data were pre-processed by tracing a straight baseline from 1740 to 1560 cm−1. To estimate the different components of amide I spectral profiles, a curve-fitting procedure was employed. Each component was assigned a Gaussian line shape, a full width at half height (FWHH) fixed at 20 cm−1, and the weight was determined without constraints. The capacitance as well as the I–V characterization of the SF films were measured with a Keythley 4200 SCS source measurement unit; the films were sandwiched between the two Cu adhesive tapes to extract the electrical signal. The relative humidity was controlled by putting the SF films into a climatic chamber at room temperature.

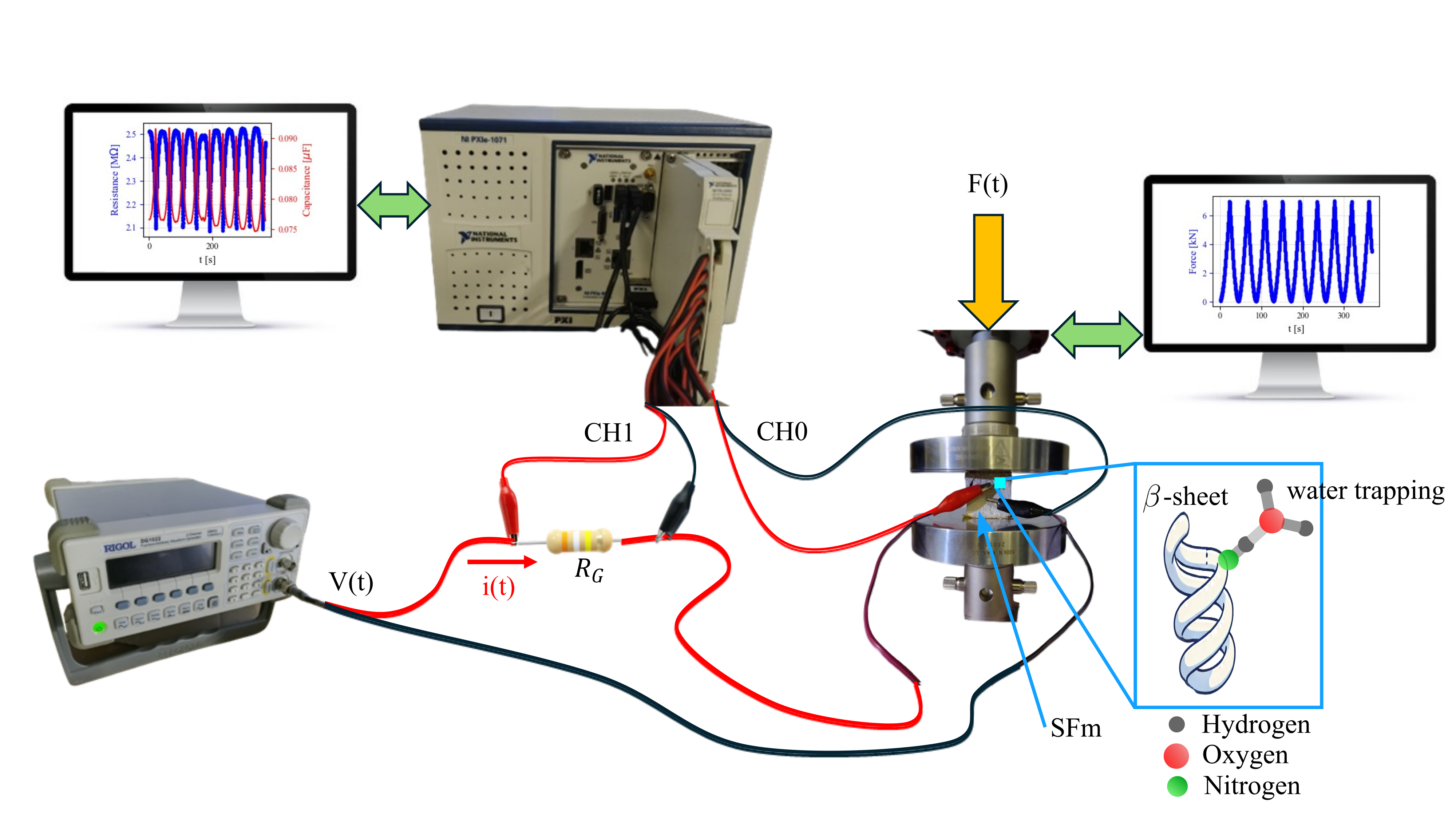

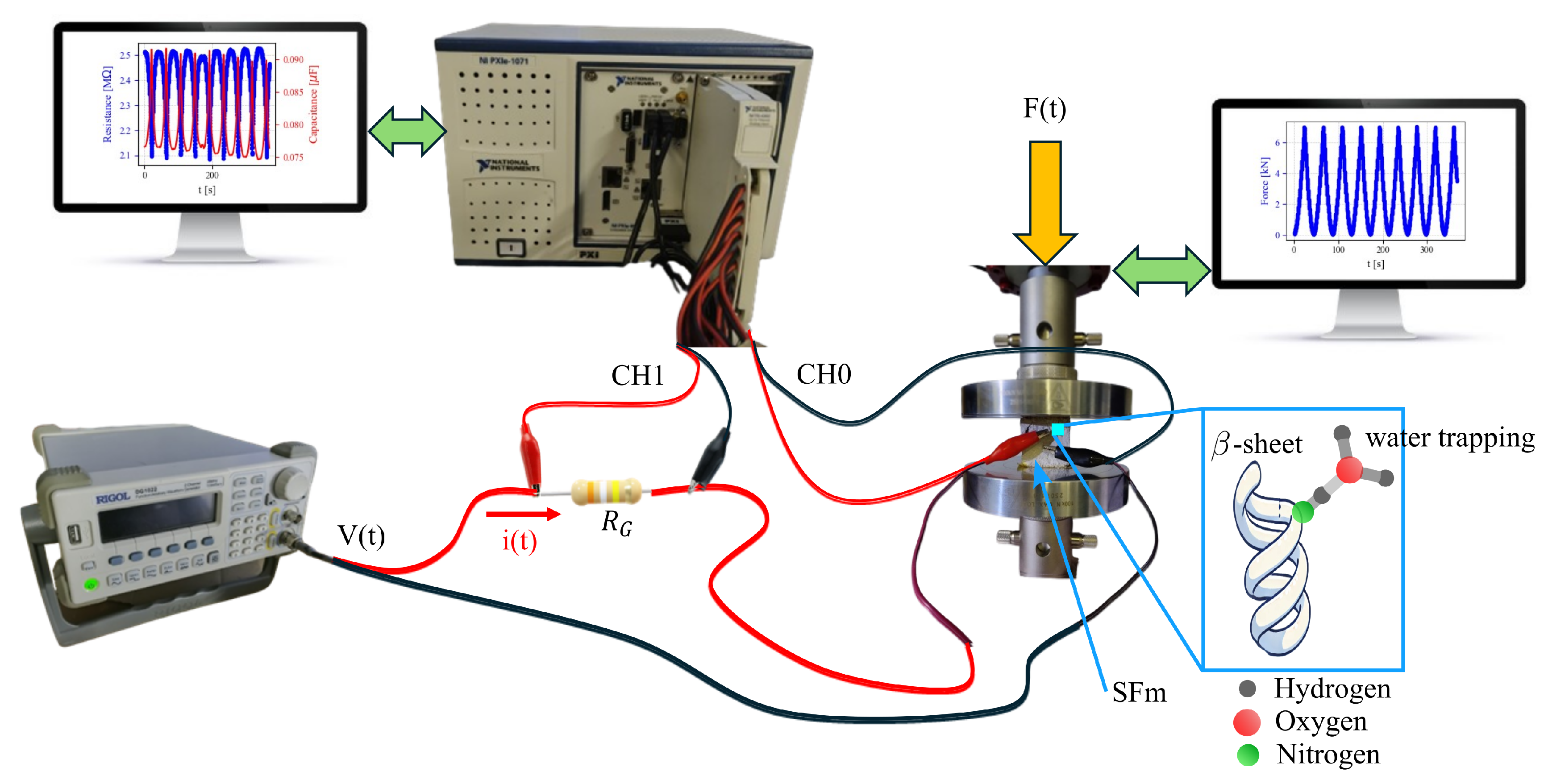

2.4. Electromechanical Characterization of SF-Cement Mortars

Electrical measurements were carried out using an acquisition system PXIe by National Instruments (NI). The PXIe-1092 contains two removable modules, the first is the controller card PXIe-8840, which supports desktop operating systems, and the second is a multiplexer card PXIe-4313, capable of acquiring up to 13 analog channels. Specifically, the PXIe-4313 was employed to acquire the voltage (channel 1) from the gain resistor, which becomes the electrical current dividing this voltage by the gain resistor; simultaneously, the acquisition system measures the applied voltage to the cement-based composites through channel 0. With regard to SFm concentrated at 50 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 200 mg/mL, a gain resistor of 1 M

was used, whereas for the mortars without SF a gain resistor of 10 k

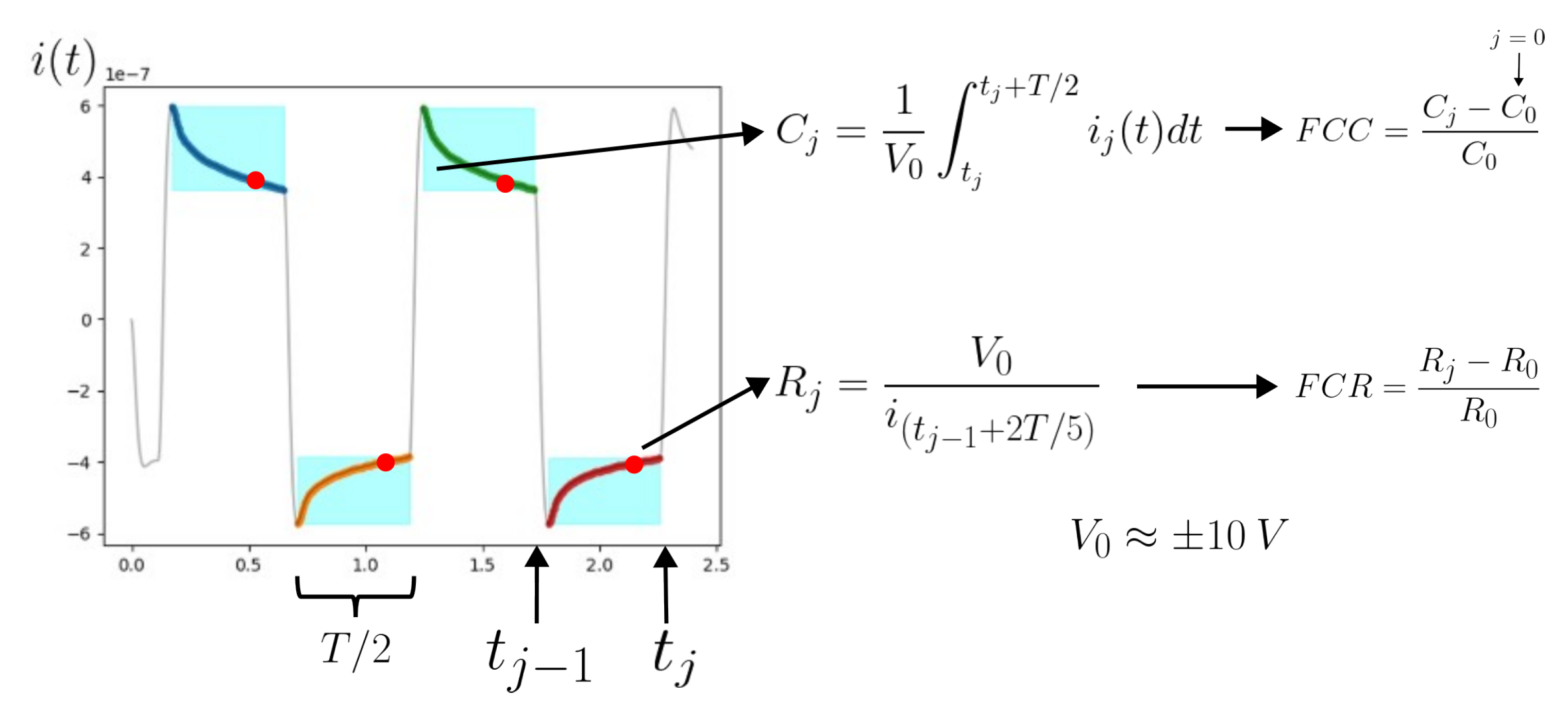

was implemented. Both the gain resistor and SFm were connected in series and powered by a signal-wave generator (model Rigol DG-1022), which provided a square voltage signal of ±10 V hereinafter referred to as the biphasic signal, as presented

Figure 2. On the other hand, cyclic voltammetry was performed on the SFm modifying shape and frequency in the signal generator to obtain a ±10 V triangular signal at 2.5 mHz. These frequency and amplitude values correspond to a ramp with scan rate at 100 mV/s. Furthermore, the triangular signal was also tested at 10 mHz, which means a scan rate at 400 mV/s. To investigate the electromechanical coupling between biphasic and compressive tests, these techniques were conducted at the same time. Then, compressive tests were performed using an universal testing system model 68TM-50 by INSTRON. In that sense, compressive cyclic loads at 0.5 mm/min from 0.02 kN up to 7 kN were applied to each specimen. Previously, the compression platens were isolated from the specimes by interposition of kapton tape.

3. Results and Discussion

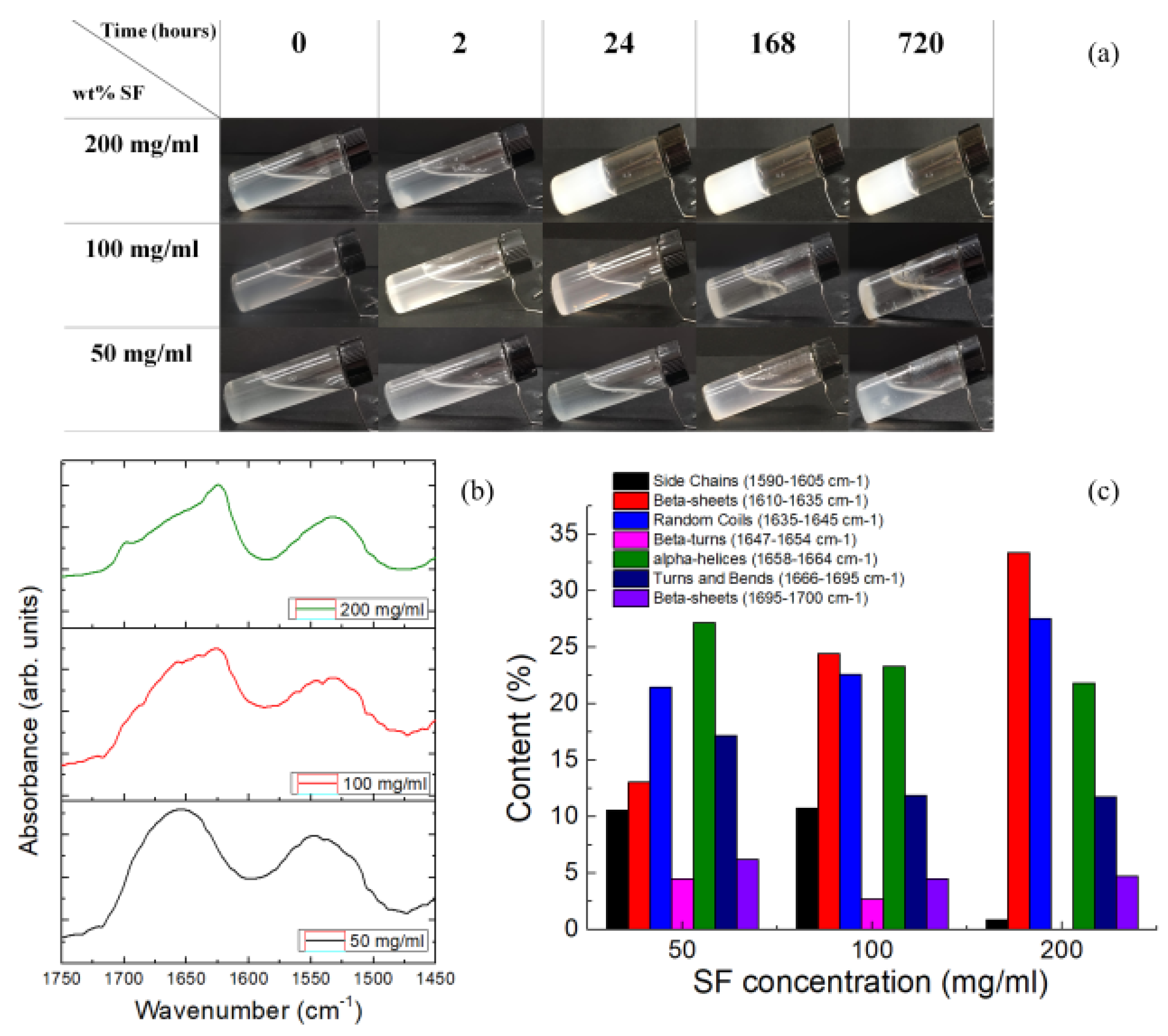

3.1. Characterization of the SF Dispersions

Silk gels form with treatments such as shearing (spinning) solvent exposure, or heating. Gels are stabilized due to the formation of thermodynamically stable

-sheets, which serve as physical cross-links to stabilize gels [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. By increasing the concentration in PBS, SF yielded an opaque white color (

Figure 1a) due to the heterogeneous microstructure of the fibroin gel causing light scattering under visible light. During early stages (e. g. after 2 hours) SF precipitates appear and the sizes of these precipitates increase leading to a gelled state. This state is stable even after 1 month. Structural changes were analyzed by ATR-FTIR as reported in

Figure 1b. The secondary structure changes of SF protein were investigated by monitoring absorptions in the 1750–1450 cm

−1 spectral region, and particularly the amide I (1700–1600 cm

−1) and amide II (1600–1500 cm

−1) bands. The peaks at ≈1622 cm

−1 (amide I) and ≈1530 cm

−1 (amide II) are characteristic of silk II secondary structure [

31]. Silk I type II

-turns show a signature in the range 1647–1654 cm

−1. SF films showed also a peak at 1644 cm

−1, corresponding to random coil [

32]. SF obtained from the solution with lowest SF concentration indicated a secondary hydrated silk I structure that can be triggered by increasing the concentration. Increasing the SF concentration in PBS, the silk II structure is forming (

Figure 3b and

Figure 3c). This is substantiated by the observation of an additional peak in the amide I profile around 1622 cm

−1, which is indicative of

-sheet conformations [

33].

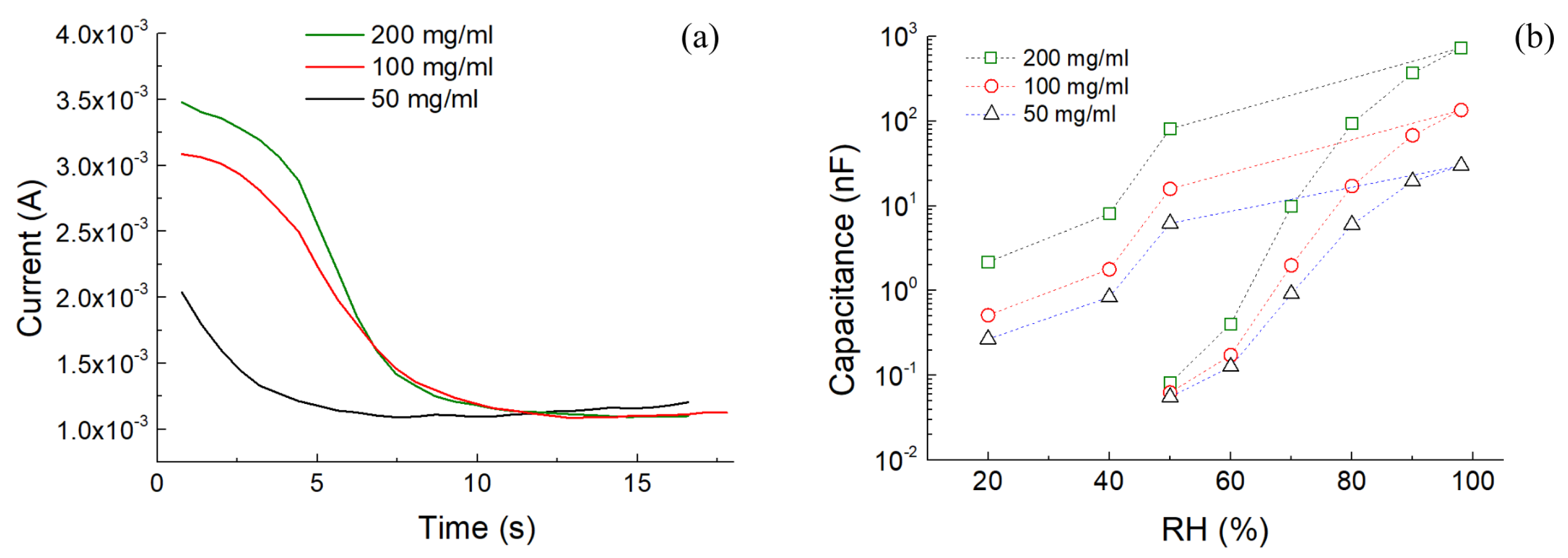

The electrical properties of the SF solutions were studied by the change of the current versus time with an applied external voltage of 3V (

Figure 4a). The solutions were positioned between two plastic wells with adhesive Cu electrodes positioned at the bottom at a distance of 1 mm. In all cases the current started to decrease with time; this phenomenon occurred due to ionic diffusion which provides a change in current. The electrical current decreases at a certain time since the ions are depleted on the Cu electrode, resulting in the creation of a higher resistance value (metallization) [

34]. It was found that SF 200 mg/ml had a higher optimal water content than SF 50 mg/ml and showed the highest ionic conductivity at the same CaCl

2 content (

Figure 4b). This behavior may be caused by the tortuous network formed by silk proteins, which inhibits the movement of ions [

35]. To test the capacitive behavior, the capacitance-relative humidity measurements were performed at 10 kHz (

Figure 4b). The capacitance at 50%RH is close to 0.06 nF. When the RH increases, the capacitance starts to rise. During the reverse cycle (e.g. from 98%RH to 50%RH), the capacitance gradually decays without reaching the initial value. The hysteretic capacitance–relative humidity curve revealed the charge trapping/detrapping effect of water [

36].

3.2. Characterization of SFm

In this subsection, we begin by presenting the electrical characterization of cementitious mortars added with aqueous solutions of silk fibroin, prepared according to the method described in

Figure 1, and whose compositions are shown in

Table 1 (see Experimental section and Supporting information). The results of electrical characterization were presented using both cyclic voltammetry and biphasic square signals, with and without mechanical compression. Then, non-symmetrical and non-linear behaviors in voltammograms are revealed, while electromechanical measurements demonstrate that silk fibroin mortar (SFm) have the potential to be used as a strain sensor.

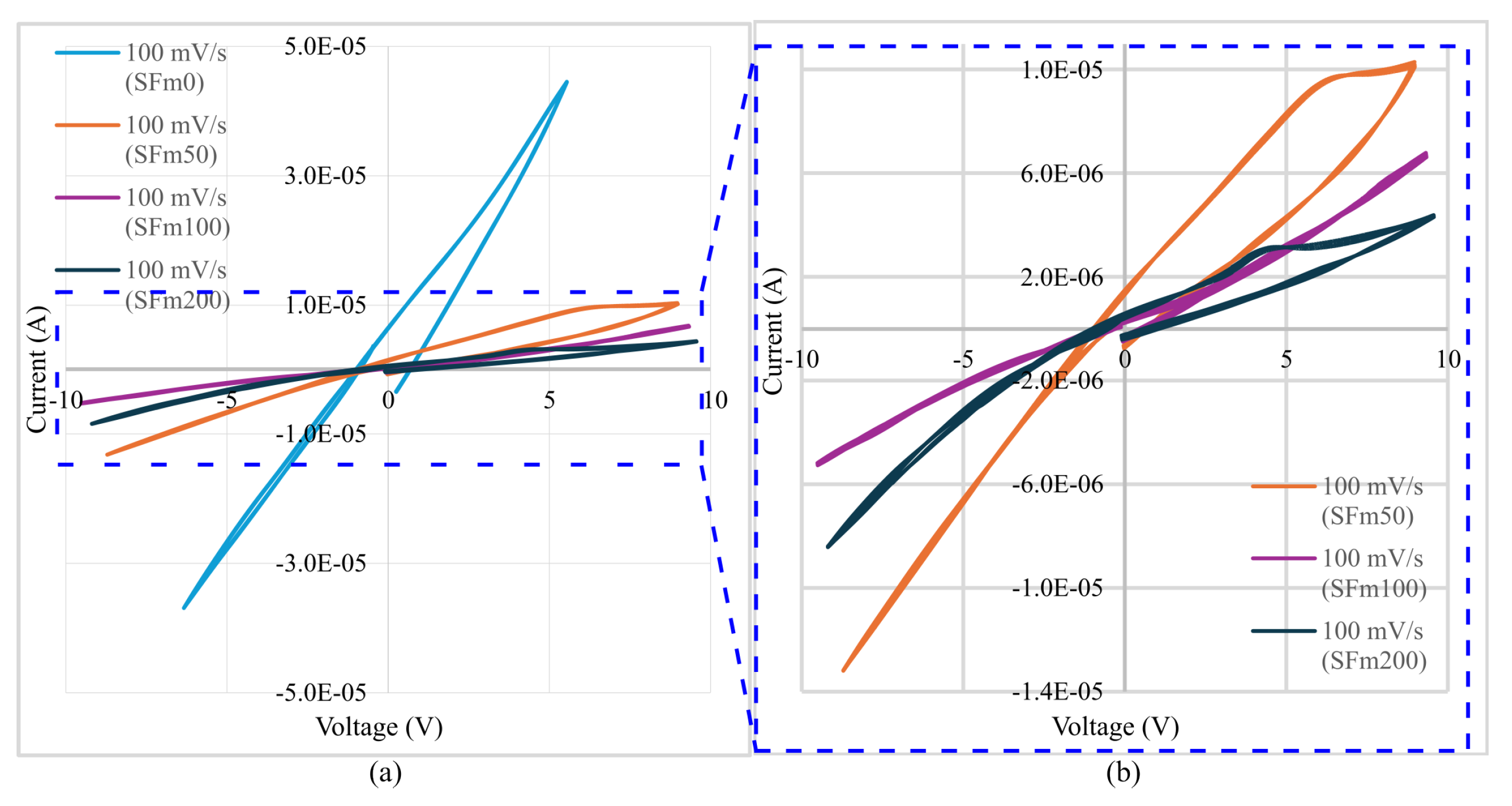

3.2.1. Cyclic Voltammetry Study of SFms

The highest electrical current was found in cement mortars without SF, higher than 10

A, and these specimens have shown a quasi-linear behavior as showed

Figure 5a. The affinity of SF with water molecules and surrounding ions [

37] produces a fast reduction in the first days of water contents in SFm. In that sense, SFm100 and SFm200 hold the lowest electrical current around the potential window ±10 V.

Voltammograms in

Figure 5b show the presence of oxidation peaks for positive voltages in SFm containing 50 mg/mL (SFm50) and 200 mg/mL (SFm200) of SF, respectively. The peaks are located at 6.4 V and 4.0 V, respectively. Moreover, these oxidation peaks occur when the voltage is dropping after it has risen to its maximum value at +10 V indicating a capacitive discharge phenomenon instead of a Faradaic process [

38,

39]. On the other hand, the negative voltage region shows a linear behavior for SFm50 specimens, but as the concentration of SF increases, the SFm100 and SFm200 curves exhibit an elbow shape, with the inflection point occurring at −2.5 V for both. Consequently, by controlling the amount of SF close to the electrodes it is possible to create an avalanche breakdown when the SFm is reverse-biased. This result is particularly promising for the development of neural cement-based materials, as it imparts semiconductor properties to cementitious materials, opening new possibilities for integrating smart sensing and adaptive capabilities into structural engineering components [

40].

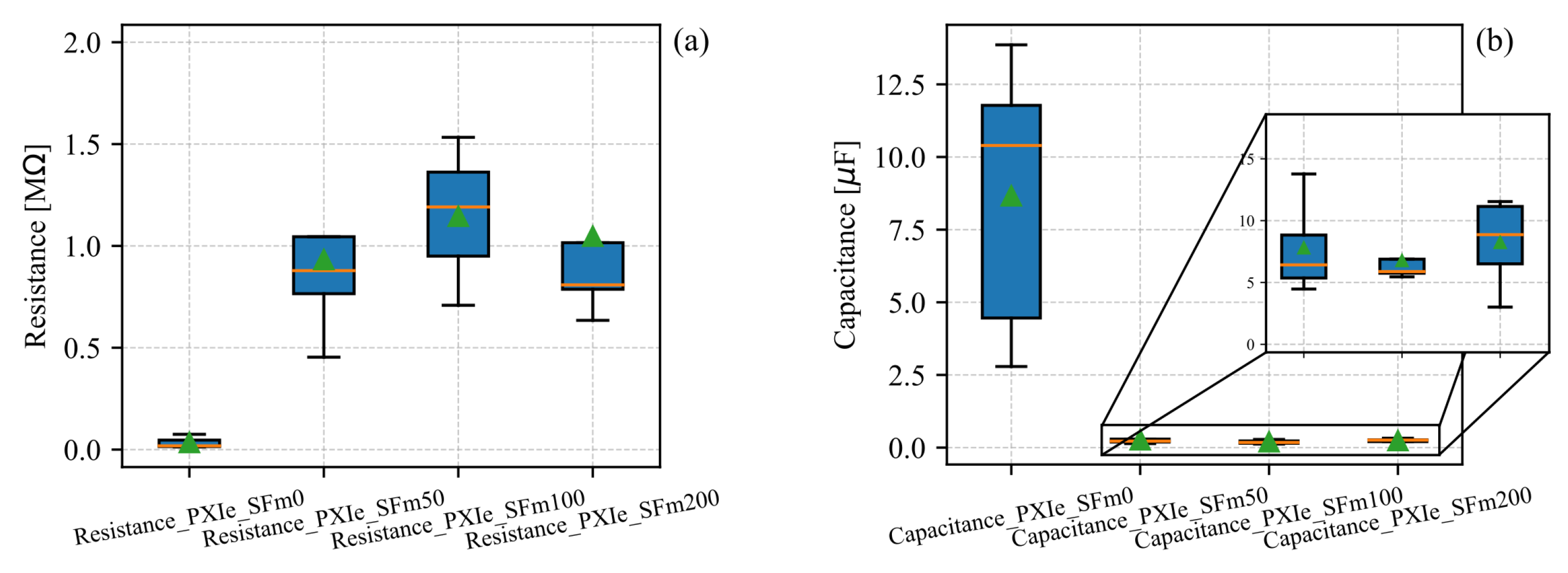

3.2.2. Electromechanical Properties of SFms

The biphasic characterization reveals a lower electrical resistance in the reference specimens (SFm0) compared to the SFm samples, as observed in

Figure 6a. This outcome was previously predicted in the voltammetric study and is correlated to the water trapping effect of the SF [

41]. Conversely, the capacitance is increased due to the high dielectric permittivity of the water present in SFm0, as delved in

Figure 6b. Furthermore, the specimens at an early age, 5 days after the 28-day curing period, exhibit similar electrical resistance values around 1 M

. However, the SFm200 samples exhibit greater precision in electrical resistance compared to the other SFm samples, whereas

Figure 6b shows that the SFm100 specimens have the highest precision in capacitance measurements, reaching 6.5

F.

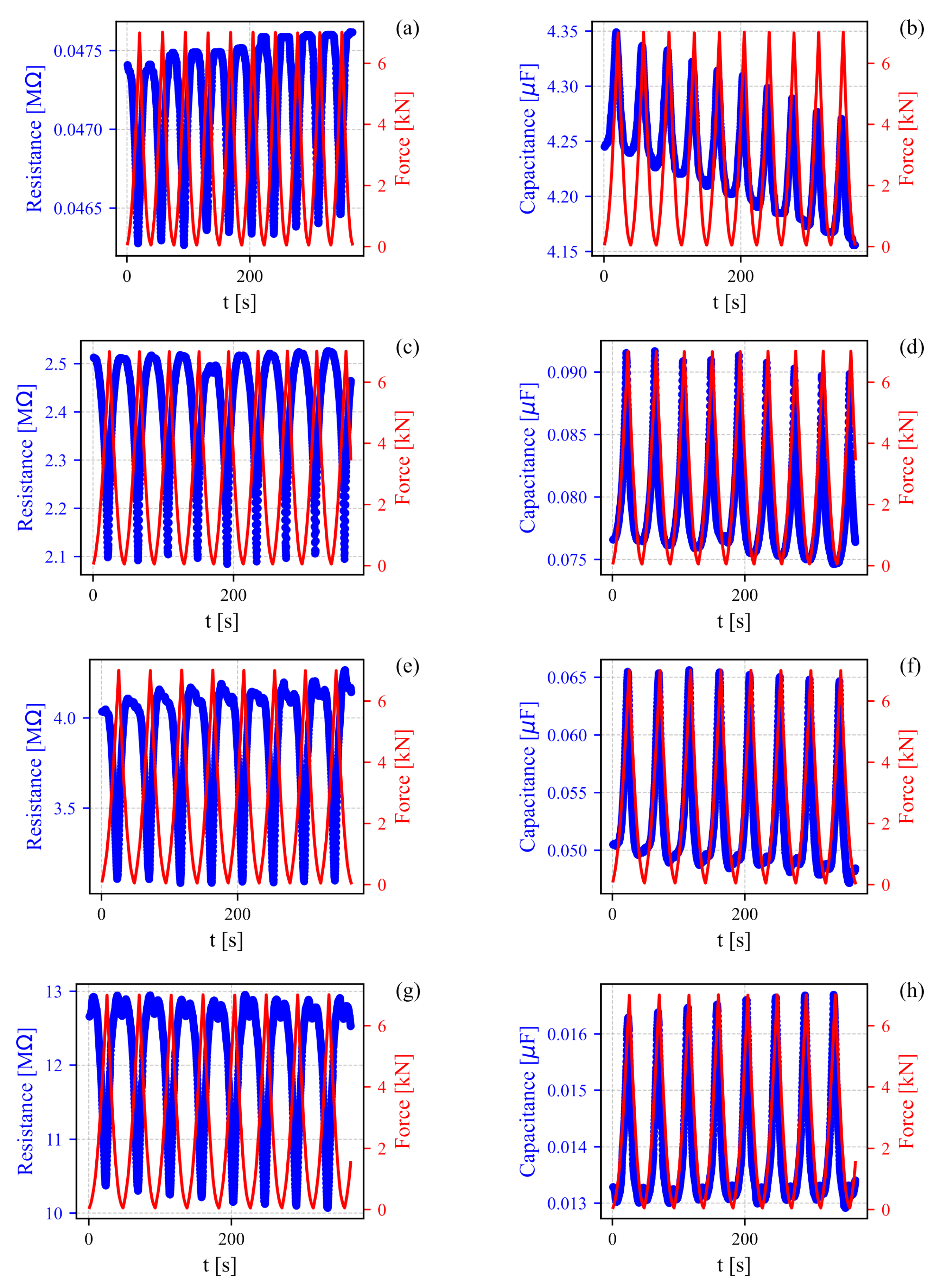

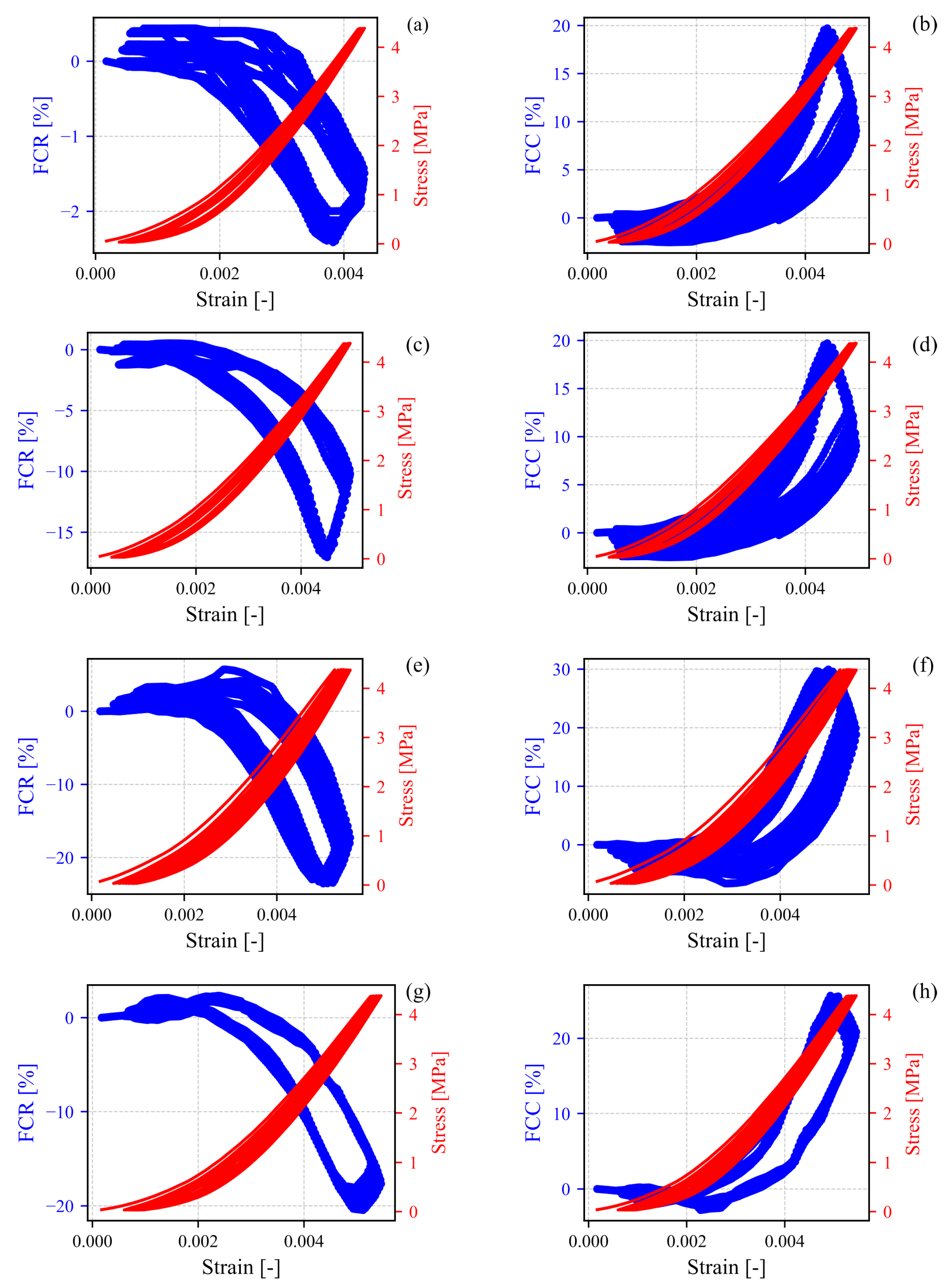

Subsequently, the results of electromechanical characterization are shown in

Figure 7. Herein, it is demonstrated how electrical resistance and capacitance plots adjust because of the changes in compressive force on the SFm specimens. SFm0 specimens (

Figure 7a and

Figure 7b) demonstrate both piezoresistive and piezocapacitive properties, while maintaining the same response profile observed during the unloading phase of the electrical tests, i.e., low resistance, and high capacitance. Furthermore, Electrical resistance and capacitance signals in SFm0 are superimposed on a linear trend, which persists in SFm50 (

Figure 7c and

Figure 7d), but becomes attenuated in SFm100 and SFm200. Another notable observation during the unloading cycles at lower force values is the damping of electrical resistance, suggesting a memory effect [

39]. Thus, the electrical properties remain relatively stable in this low-strain regime. This phenomenon is particularly striking in SFm100 and SFm200, as highlighted by both the piezoresistive and piezocapacitive curves in

Figure 7e-h.

Piezocapacitance, is not exclusive of cementitious materials based on microfibers or nanofibers, as illustrated in

Figure 8a and

Figure 8b and supported by existing literature [

42]. However, these piezocapacitance properties are significantly enhanced by mitigating hysteresis effects, besides increasing the sensibility and linearity as demonstrated in

Figure 8c -

Figure 8h. Specifically, the fractional change in resistance (FCR) achieved a maximum magnitude of 25% for SFm100 specimens, whereas the fractional change in capacitance (FCC) reached up to 30%. The methodology to compute FCR and FCC is illustrated in the diagram shown in

Figure 9.

It is also important to note that the linearity observed in both fractional changes of electrical properties emerges after a strain (positive in compression)

, at which point the mechanical behavior also exhibits linear characteristics. Following this breakpoint, gauge Young’s modulus

E and gauge factors

were calculated and presented in

Table 2. Subscript

R indicate gauge factors derived from the material’s resistance, whereas subscript

C depicts those extracted from capacitance. Gauge factor allowed to assess the SFm’s sensitivity and reproducibility after subjecting them to cyclic strain conditions. These values were determined using the following equations:

Young’s modulus of SFm100 presented a slight decrease of 18.7% compared to reference specimens SFm0, because of SF capturing water molecules, avoiding that new hydration products are formed. On the other hand, SFm concentrations of 50 mg/mL and 200 mg/mL exhibited an approximate 12% reduction in Young’s modulus. Concerning electromechanical properties, SFm100 presented the greatest enhancement in resistive and capacitive gauge factors of 90% and 92%, respectively. These results are prominent, especially when compared to graphene/cement-based composites [

43], which have shown an increasing trend with graphene concentrations below the percolation threshold, which is equal to 4% in the above reference. What is more, the theoretical gauge factor exceeds 90 [

44]. In comparison to non-carbon fibers, this work presents SFm samples subjected to compression up to 4.5 MPa, achieving a capacitive gauge factor of up to 156. For instance, Fan et al. [

44] reported a maximum compressive strength of approximately 6 MPa and an experimental gauge factor around 50, while Lian et al. [

6] observed a gauge factor of 107 for aligned copper-coated steel fibers concentrated at 1.5%, by using a maximum compressive strength of 20 MPa.

4. Conclusions

In summary, our design of silk fibroin/cement mortar composites offers a novel approach to smart sensing in cement-based materials, unlocking significant potential for SHM of masonry and concrete structures. Key to processability with cement paste is the water solubility of SF, which originates from the unique conformational transitions of secondary structures. This intrinsic nature of regenerated proteins allows us to mix SF in the cement mortar and to control the ions mobility due to the different hydration state of SF. More specifically, the results indicated the piezoresistive, piezocapacitive and memcapacitive properties of SF/cement mortar composites. We expect that the availability and sustainability of SF as a sensing material open perspectives on the design of multifunctional concrete and masonry structures with self-sensing properties.

Author Contributions

DanielAndresTriana-Camacho: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Antonella D’Alessandro: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original Draft. Silvia Bittolo Bon: Data curation, Investigation: Equal. Rocco Malaspina Data curation, Investigation. Filippo Ubertini: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Luca Valentini: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This work has been partly funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU under the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) National Innovation Ecosystem grant ECS00000041 - VITALITY - CUP J97G22000170005 and CUP B43C22000470005. The work has been also funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) via the FIS2021 Advanced Grant “SMS-SAFEST - Smart Masonry enabling SAFE-ty-assessing STructures after earthquakes” (FIS00001797).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Han, B.; Yu, X.; Ou, J. Self-sensing concrete in smart structures; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Thomoglou, A.K.; Falara, M.G.; Gkountakou, F.I.; Elenas, A.; Chalioris, C.E. Smart Cementitious Sensors with Nano-, Micro-, and Hybrid-Modified Reinforcement: Mechanical and Electrical Properties. Sens. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Sun, M. Pressure-Sensitive Capability of AgNPs Self-Sensing Cementitious Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glisic, B. Concise Historic Overview of Strain Sensors Used in the Monitoring of Civil Structures: The First One Hundred Years. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Coffetti, D.; Crotti, E.; Coppola, L.; Meoni, A.; Ubertini, F. Self-Sensing Properties of Green Alkali-Activated Binders with Carbon-Based Nanoinclusions. Sust. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Liu, X.; Lyu, X.; Yang, Q.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zuo, J.; Shah, S.P. Research on the conductivity and self-sensing properties of high strength cement-based material with oriented copper-coated steel fibers. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannat, T.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, D. Influences of CNT Dispersion Methods, W/C Ratios, and Concrete Constituents on Piezoelectric Properties of CNT-Modified Smart Cementitious Materials. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D. A critical review of electrical-resistance-based self-sensing in conductive cement-based materials. Carbon 2023, 203, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, B.; Vlachakis, C.; Al-Tabbaa, A.; Haigh, S.K. Characterization and piezo-resistivity studies on graphite-enabled self-sensing cementitious composites with high stress and strain sensitivity. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 142, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanut, N.; Stefaniuk, D.; Weaver, J.C.; Zhu, Y.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Masic, A.; Ulm, F.J. Carbon–cement supercapacitors as a scalable bulk energy storage solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2304318120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adresi, M.; Pakhirehzan, F. Evaluating the performance of Self-Sensing concrete sensors under temperature and moisture variations- a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 132923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, X.; Liu, J. Effects of salt freeze-thaw cycles and cyclic loading on the piezoresistive properties of carbon nanofibers mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 177, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, S.; Ahmed, R.; Zhang, L.; Han, B. Improving the mechanical characteristics of well cement using botryoid hybrid nano-carbon materials with proper dispersion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhangar, K.; Kumar, M.; Aouad, M.; Mahlknecht, J.; Raval, N.P. Aggregation behaviour of black carbon in aquatic solution: Effect of ionic strength and coexisting metals. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 137088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Zhang, J.; Chang, J.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Huang, J. Research on the Properties and Mechanism of Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Low-Carbon Ecological Cement-Based Materials. Mater. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, S.; Ren, J.; Ling, S. Flame-Retardant and Sustainable Silk Ionotronic Skin for Fire Alarm Systems. ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 2, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, Q.; Da, G.; Yao, J.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X. A highly stretchable and anti-freezing silk-based conductive hydrogel for application as a self-adhesive and transparent ionotronic skin. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 8955–8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, Q.; Ren, J.; Chen, W.; Pei, Y.; Kaplan, D.L.; Ling, S. Electro-Blown Spun Silk/Graphene Nanoionotronic Skin for Multifunctional Fire Protection and Alarm. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Tang, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Yao, J.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X. Silk-based pressure/temperature sensing bimodal ionotronic skin with stimulus discriminability and low temperature workability. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 422, 130091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strynadka, N.C.; James, M.N. Crystal structures of the helix-loop-helix calcium-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989, 58, 951–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partlow, B.P.; Hanna, C.W.; Rnjak-Kovacina, J.; Moreau, J.E.; Applegate, M.B.; Burke, K.A.; Marelli, B.; Mitropoulos, A.N.; Omenetto, F.G.; Kaplan, D.L. Highly Tunable Elastomeric Silk Biomaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 4615–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Xia, M.; Zhuge, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, B.; Fu, Y.; Yang, K.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Scheicher, R.H.; Miao, X.S. Nanochannel-Based Transport in an Interfacial Memristor Can Emulate the Analog Weight Modulation of Synapses. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 4279–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, A.P.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, K.; Qin, C.; Wang, G.; Pei, Y.; Li, H.; Ren, D.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q. Vacancy-Induced Synaptic Behavior in 2D WS2 Nanosheet–Based Memristor for Low-Power Neuromorphic Computing. Small 2019, 15, 1901423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libera, V.; Malaspina, R.; Bittolo Bon, S.; Cardinali, M.A.; Chiesa, I.; De Maria, C.; Paciaroni, A.; Petrillo, C.; Comez, L.; Sassi, P.; Valentini, L. Conformational transitions in redissolved silk fibroin films and application for printable self-powered multistate resistive memory biomaterials. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 22393–22402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.; Wu, F.; Xing, T.; Yadavalli, V.K.; Kundu, S.C.; Lu, S. A silk fibroin hydrogel with reversible sol–gel transition. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24085–24096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, K.R.; Park, K. Biodegradable hydrogels in drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 1993, 11, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.J.; Kaplan, D.L. Mechanism of silk processing in insects and spiders. Nature 2003, 424, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Chen, J.; Collette, A.L.; Kim, U.J.; Altman, G.H.; Cebe, P.; Kaplan, D.L. Mechanisms of Silk Fibroin Sol−Gel Transitions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 21630–21638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, S.; Kundu, S.C. Silk protein-based hydrogels: Promising advanced materials for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2016, 31, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ren, Q.; Chen, X.; Shao, Z. Injectable thixotropic hydrogel comprising regenerated silk fibroin and hydroxypropylcellulose. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 2875–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Kluge, J.A.; Lu, S.; Cebe, P.; Kaplan, D.L. Water-insoluble silk films with silk I structure. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Kaplan, D.; Cebe, P. Determining Beta-Sheet Crystallinity in Fibrous Proteins by Thermal Analysis and Infrared Spectroscopy. Macromol. 2006, 39, 6161–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.W.; Tonelli, A.E.; Hudson, S.M. Structural Studies of Bombyx mori Silk Fibroin during Regeneration from Solutions and Wet Fiber Spinning. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.; Hassan, G.; Bae, J. Soft ionic liquid based resistive memory characteristics in a two terminal discrete polydimethylsiloxane cylindrical microchannel. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 13368–13374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougale, M.; Patil, S.; Shinde, S.; Khot, S.; Patil, A.; Khot, A.; S. S, C.; Volos, C.; Kim, S.; Dongale, D.T. Memristive switching in ionic liquid–based two-terminal discrete devices. Ionics 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hu, Y.; Shi, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Lyu, H.; Xia, J.; Meng, J.; Lu, X.; Yeo, J.; Lu, Q.; Guo, C. Molecular Design and Preparation of Protein-Based Soft Ionic Conductors with Tunable Properties. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2022, 14, 48061–48071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Hu, Y.; Shi, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Lyu, H.; Xia, J.; Meng, J.; Lu, X.; Yeo, J.; Lu, Q.; Guo, C. Molecular Design and Preparation of Protein-Based Soft Ionic Conductors with Tunable Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 48061–48071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Xie, Y. Matching Faradaic reaction of multi-transition metal compounds as supercapacitor electrode materials: A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, M.K.; Bera, M.K.; Kundu, B.; Kundu, S.C.; Maiti, C.K. A Natural Silk Fibroin Protein-Based Transparent Bio-Memristor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4493–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przyczyna, D.; Suchecki, M.; Adamatzky, A.; Szaciłowski, K. Towards Embedded Computation with Building Materials. Mater. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, J.; Liu, H.; Shi, L.; Welch, K.; Wang, Z.; Strømme, M. Electrochemically Active, Compressible, and Conducting Silk Fibroin Hydrogels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 9310–9317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Wang, Y. Capacitance-based stress self-sensing in cement paste without requiring any admixture. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 94, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.G.; Awol, J.F.; Chen, S.; Jiang, J.; Pu, X.; Jia, X.; Xu, X. Experimental study of the electrical resistance of graphene oxide-reinforced cement-based composites with notch or rebar. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, J.; Ni, Z.; Hang, Z.; Feng, C.; Yang, J.; Su, Y.; Weng, G.J. A two-step homogenization micromechanical model for strain-sensing of graphene reinforced porous cement composites. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Preparation of specimens based on silk fibroin.

Figure 1.

Preparation of specimens based on silk fibroin.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup to obtain electromechanical properties of SFm.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup to obtain electromechanical properties of SFm.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of SF sol–gel transition: (a) dynamic optical morphology, (b) FTIR spectra and (c) relative weight of components obtained by curve-fitting procedure of FTIR spectra of SF prepared by different concentrations.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of SF sol–gel transition: (a) dynamic optical morphology, (b) FTIR spectra and (c) relative weight of components obtained by curve-fitting procedure of FTIR spectra of SF prepared by different concentrations.

Figure 4.

(a) Current transients of SF dispersions. (b) Capacitance-relative humidity curve of the prepared SF dispersions with sweeping RH 20%→98%→50%.

Figure 4.

(a) Current transients of SF dispersions. (b) Capacitance-relative humidity curve of the prepared SF dispersions with sweeping RH 20%→98%→50%.

Figure 5.

(a) Cyclic voltammetry of SFm specimens with SF concentrations of 0 mg/mL, 50 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 200 mg/mL performed at a scan rate of 100 mV/s, and (b) magnification of SFm specimens with concentration at 50 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 200 mg/mL, respectively.

Figure 5.

(a) Cyclic voltammetry of SFm specimens with SF concentrations of 0 mg/mL, 50 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 200 mg/mL performed at a scan rate of 100 mV/s, and (b) magnification of SFm specimens with concentration at 50 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 200 mg/mL, respectively.

Figure 6.

(a) Electrical resistance and (b) capacitance of SFm samples as a function to the SF concentrations.

Figure 6.

(a) Electrical resistance and (b) capacitance of SFm samples as a function to the SF concentrations.

Figure 7.

Variation of resistance and capacitance of SFm specimens with SF concentrations of (a-b) 0 mg/mL, (c-d) 50 mg/mL, (e-f) 100 mg/mL, and (g-h) 200 mg/mL subjected under cyclic compressive force from 0.02 to 7 kN.

Figure 7.

Variation of resistance and capacitance of SFm specimens with SF concentrations of (a-b) 0 mg/mL, (c-d) 50 mg/mL, (e-f) 100 mg/mL, and (g-h) 200 mg/mL subjected under cyclic compressive force from 0.02 to 7 kN.

Figure 8.

Correlation between FCR and FCC and compressive strain of SFm specimens with SF concentrations of (a-b) 0 mg/mL, (c-d) 50 mg/mL, (e-f) 100 mg/mL, and (g-h) 200 mg/mL. The whole specimens were subjected to cyclic compressive force from 0.02 to 7 kN.

Figure 8.

Correlation between FCR and FCC and compressive strain of SFm specimens with SF concentrations of (a-b) 0 mg/mL, (c-d) 50 mg/mL, (e-f) 100 mg/mL, and (g-h) 200 mg/mL. The whole specimens were subjected to cyclic compressive force from 0.02 to 7 kN.

Figure 9.

Diagram illustrating the definition of fractional change in resistance (FCR) and fractional change in capacitance (FCC) based on biphasic measurements.

Figure 9.

Diagram illustrating the definition of fractional change in resistance (FCR) and fractional change in capacitance (FCC) based on biphasic measurements.

Table 1.

Composition of SF based mortars.

Table 1.

Composition of SF based mortars.

| Specimens |

Cement (c) |

Sand |

Water (w) |

SF |

Ratio w/c |

| |

(g) |

(g) |

(g) |

(mg/ml) |

|

| SFm0 |

172 |

602 |

86 |

0 |

0.5 |

| SFm50 |

172 |

602 |

86 |

50 |

0.5 |

| SFm100 |

172 |

602 |

86 |

100 |

0.5 |

| SFm200 |

172 |

602 |

86 |

200 |

0.5 |

Table 2.

Young’s modulus (E) and gauge factors resistive () and capacitive () of SFm specimens.

Table 2.

Young’s modulus (E) and gauge factors resistive () and capacitive () of SFm specimens.

| Specimens |

E (MPa) |

|

|

| SFm0 |

1455.340 ± 39.314 |

-13.171 ± 0.847 |

13.326 ± 0.750 |

| SFm50 |

1281.305 ± 21.562 |

-92.265 ± 1.371 |

103.616 ± 1.465 |

| SFm100 |

1182.487 ± 19.265 |

-131.844 ± 7.710 |

156.698 ± 8.120 |

| SFm200 |

1272.149 ± 11.847 |

-115.676 ± 5.863 |

136.722 ± 9.728 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).