Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

23 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

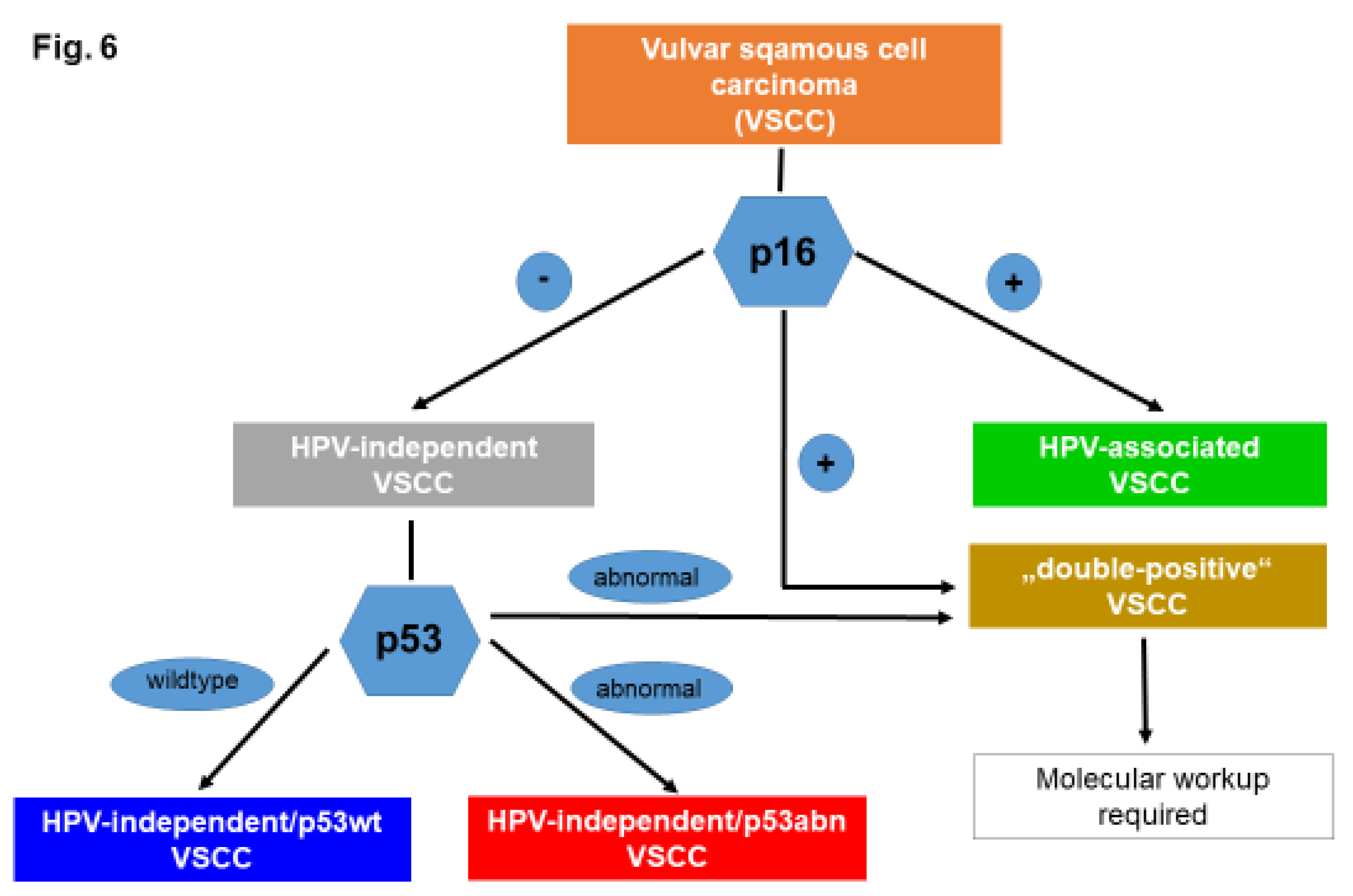

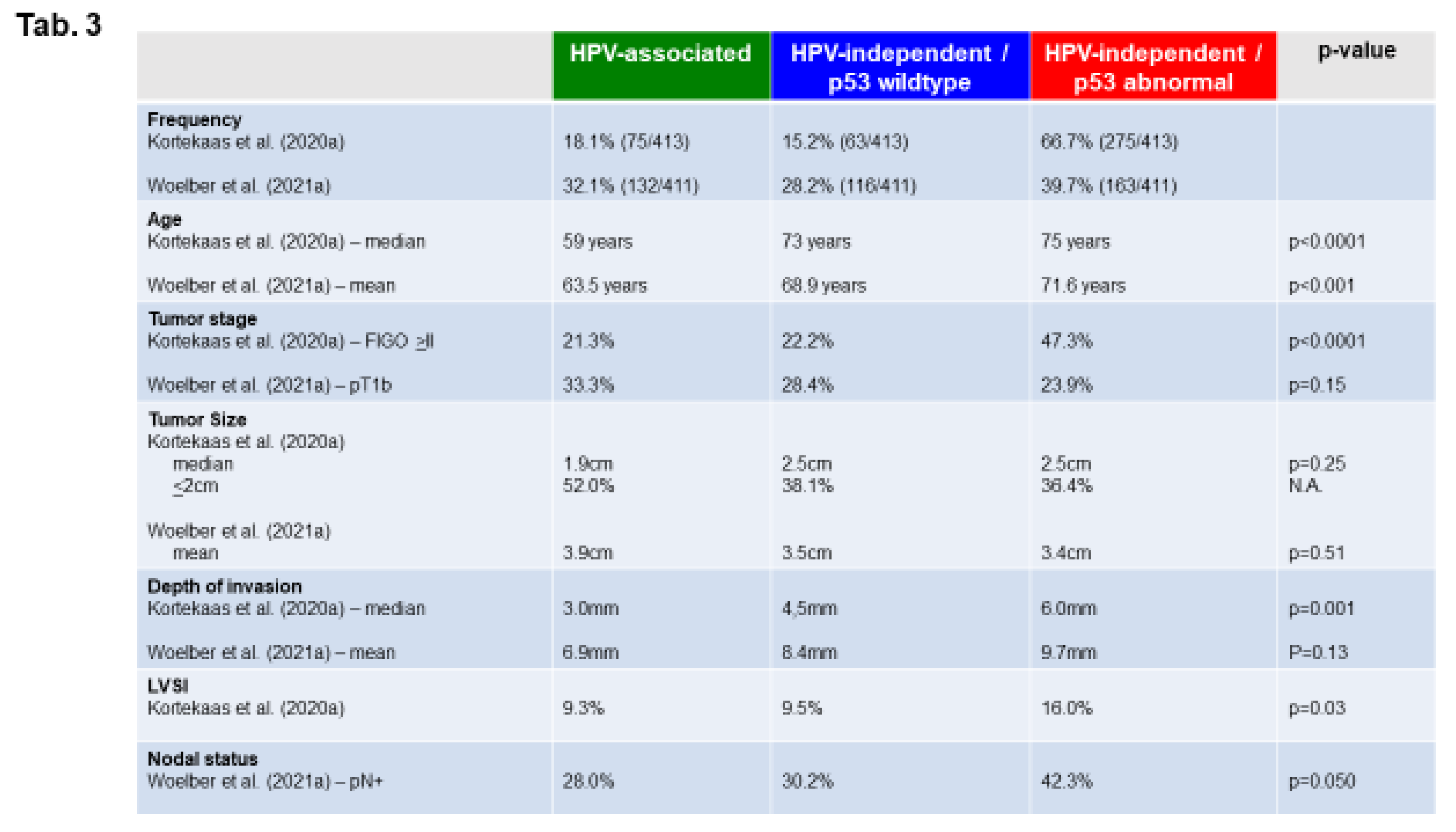

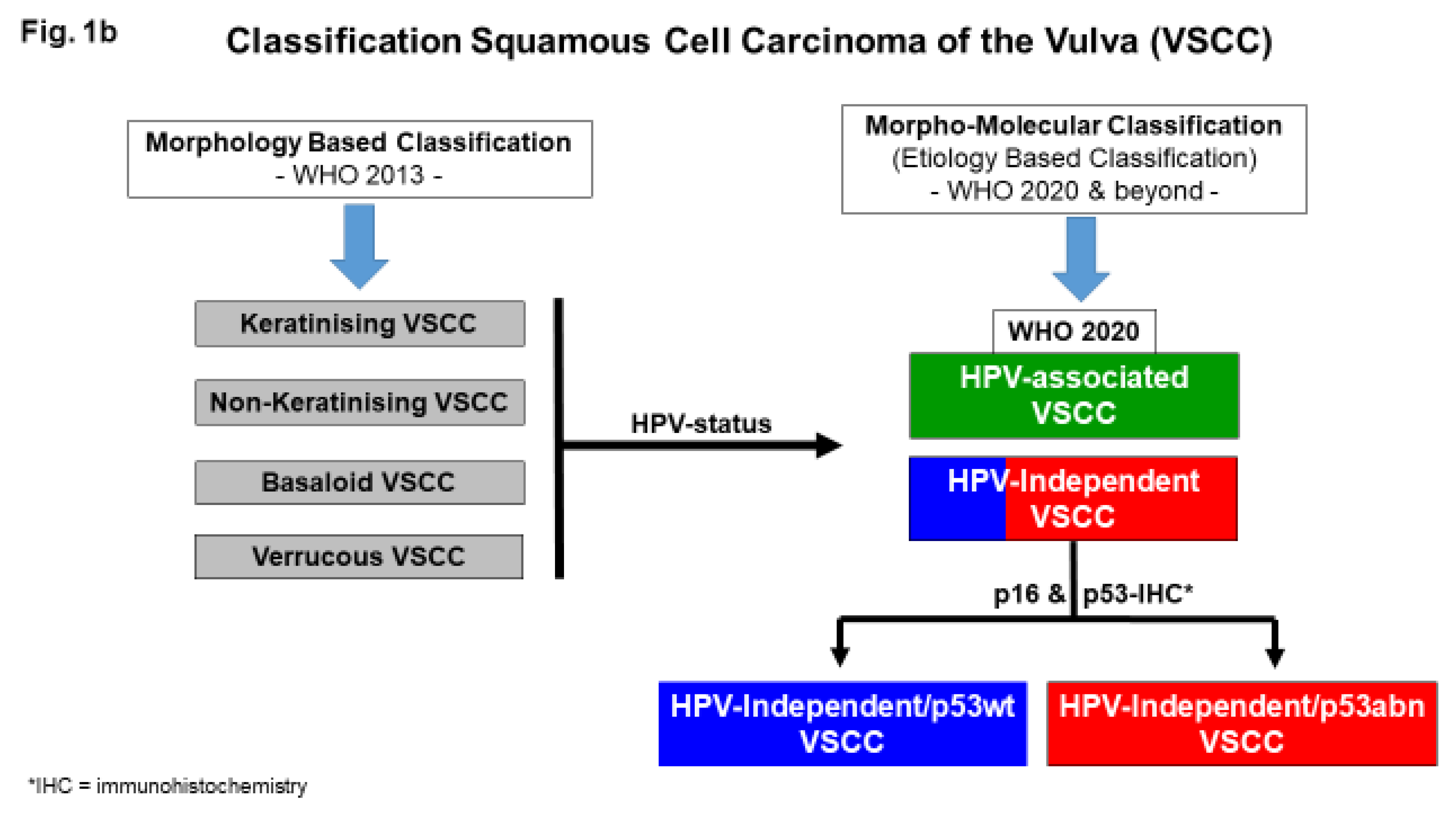

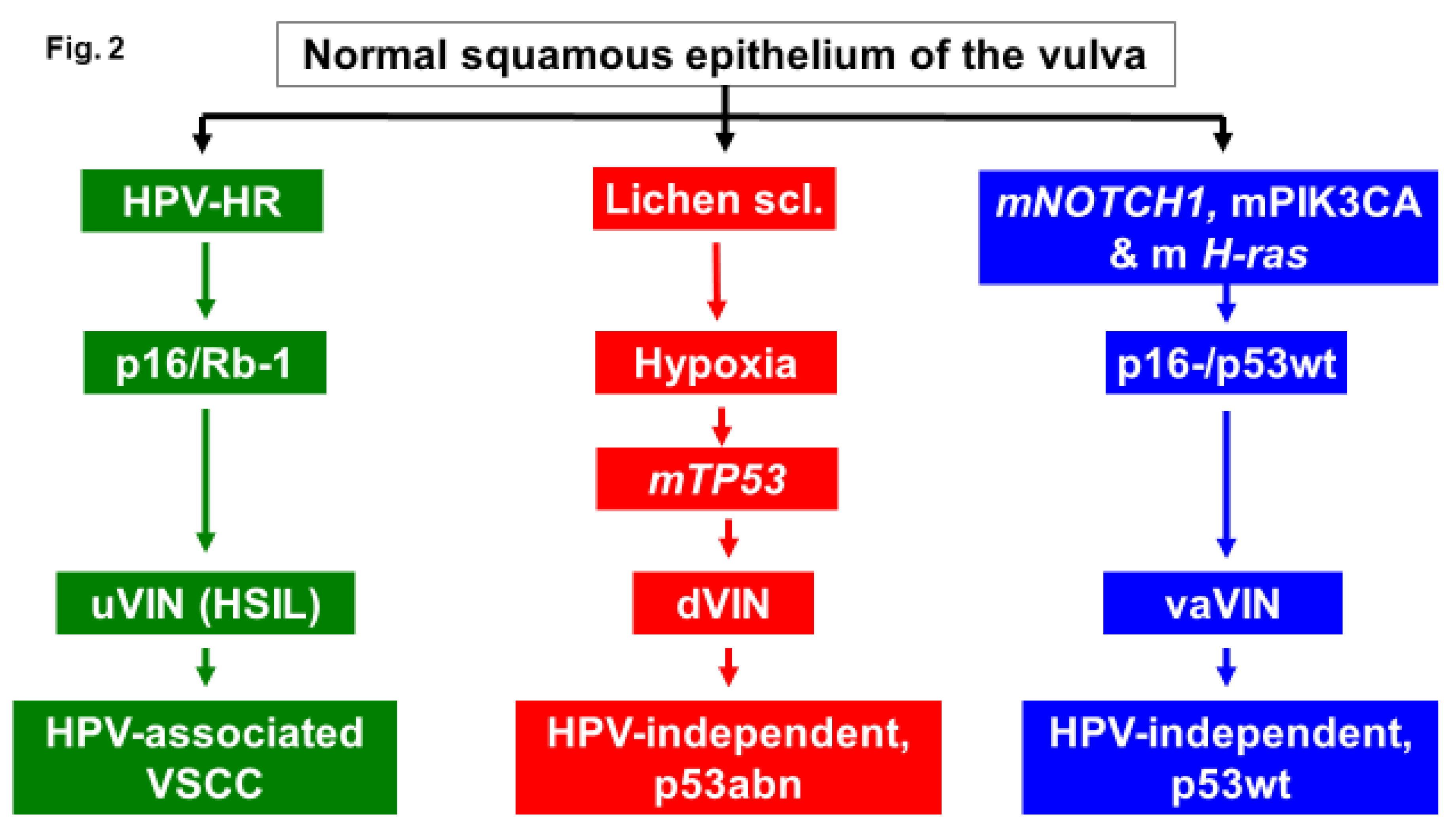

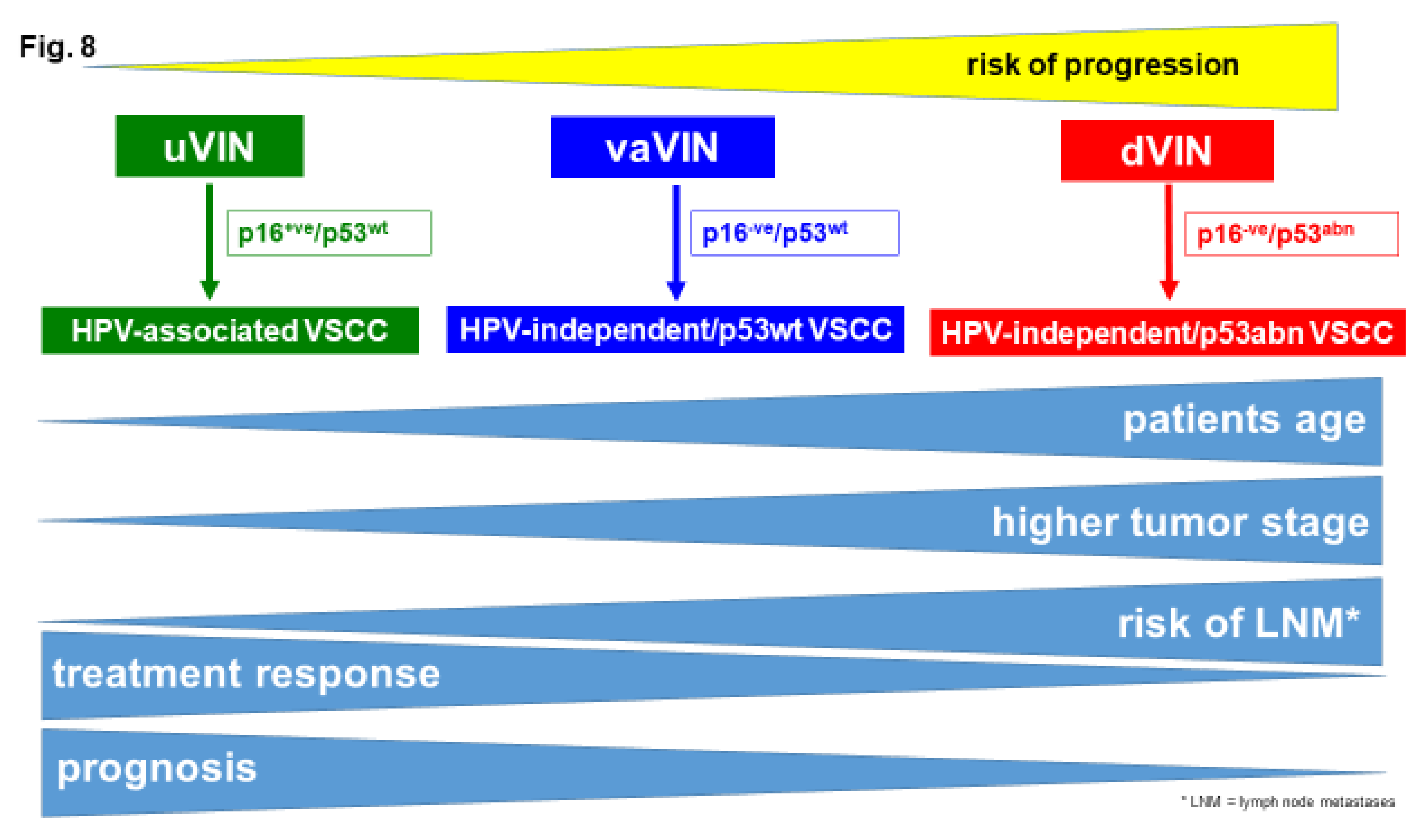

Molecular Subtypes of VSCC

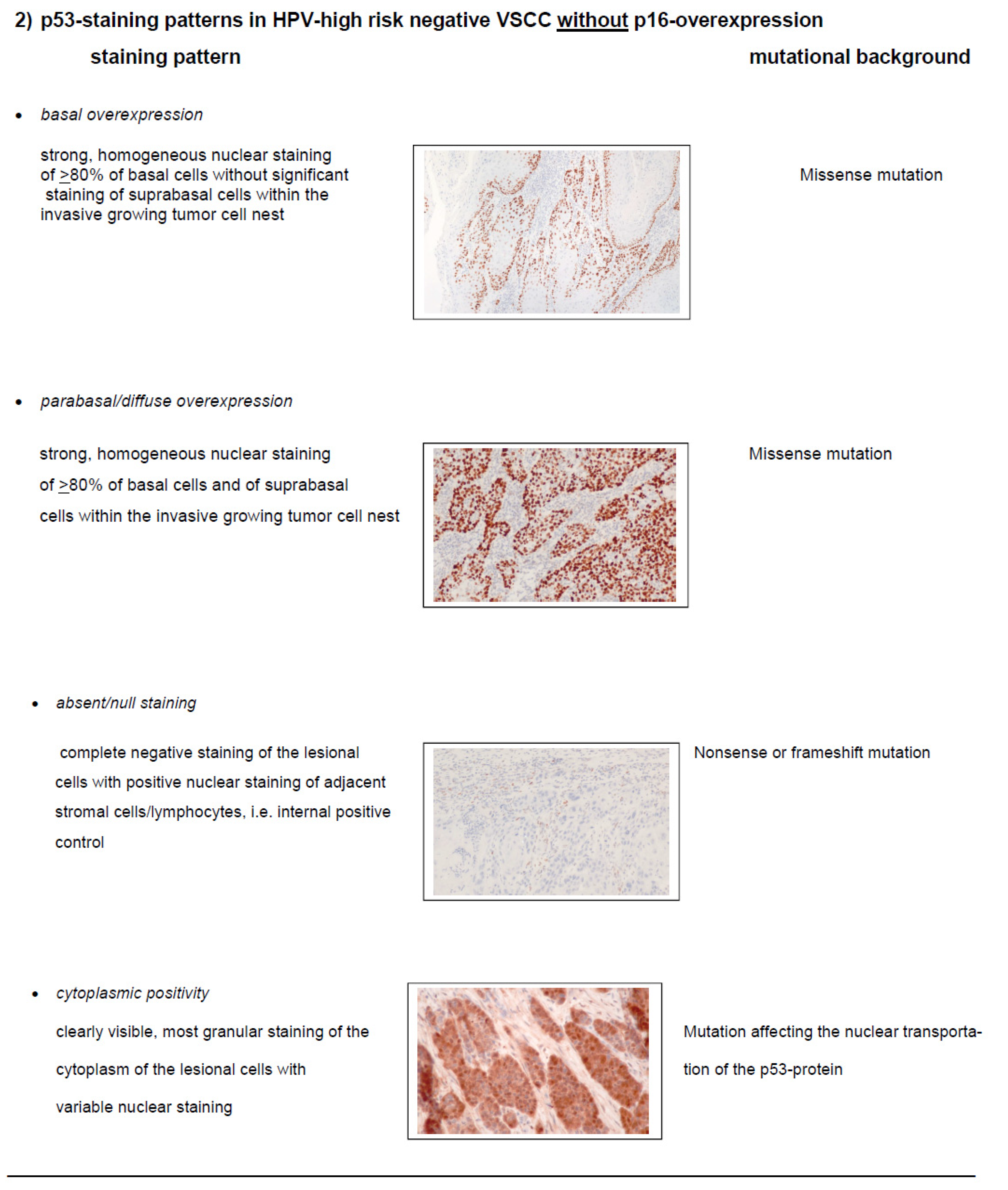

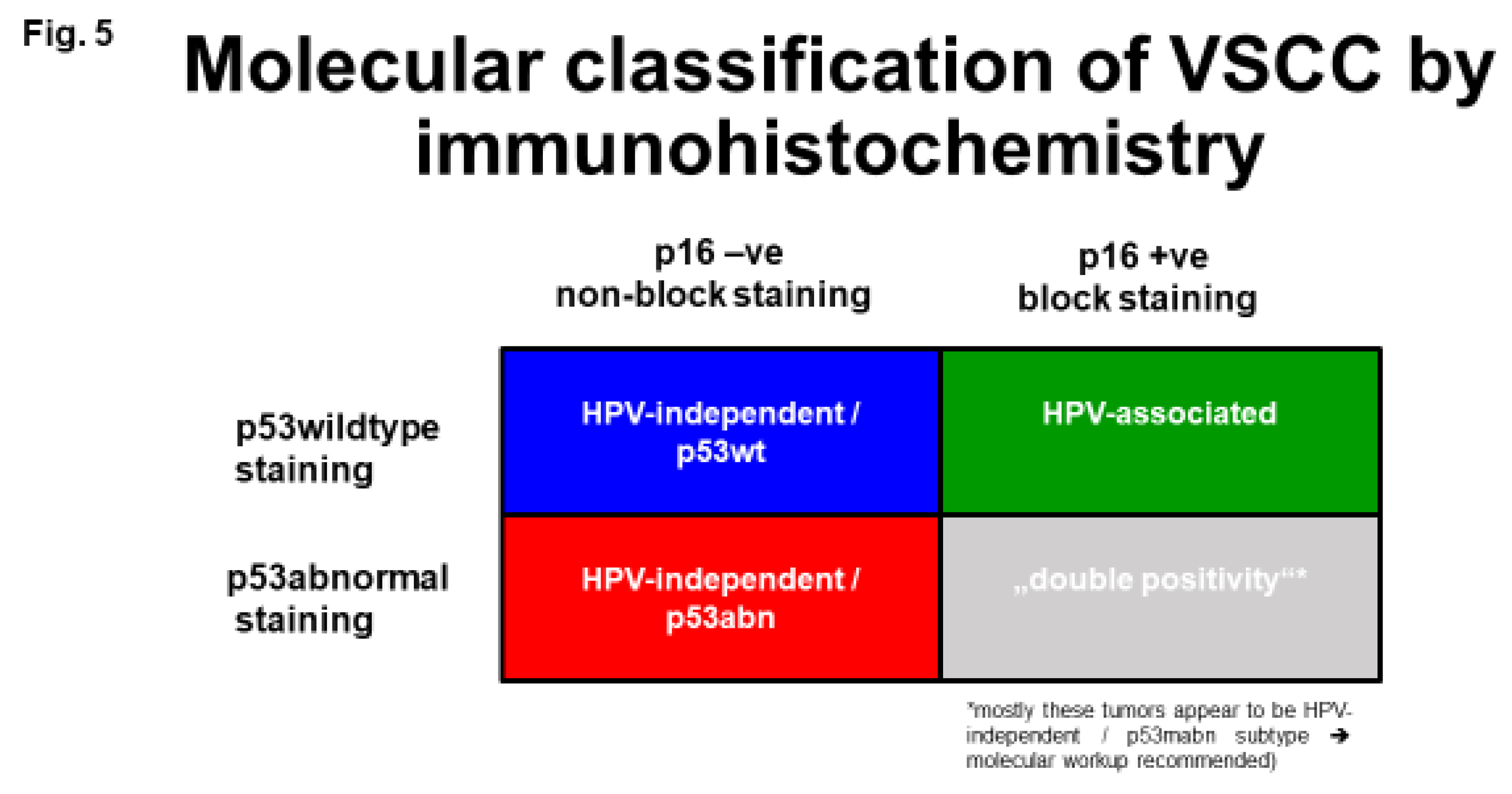

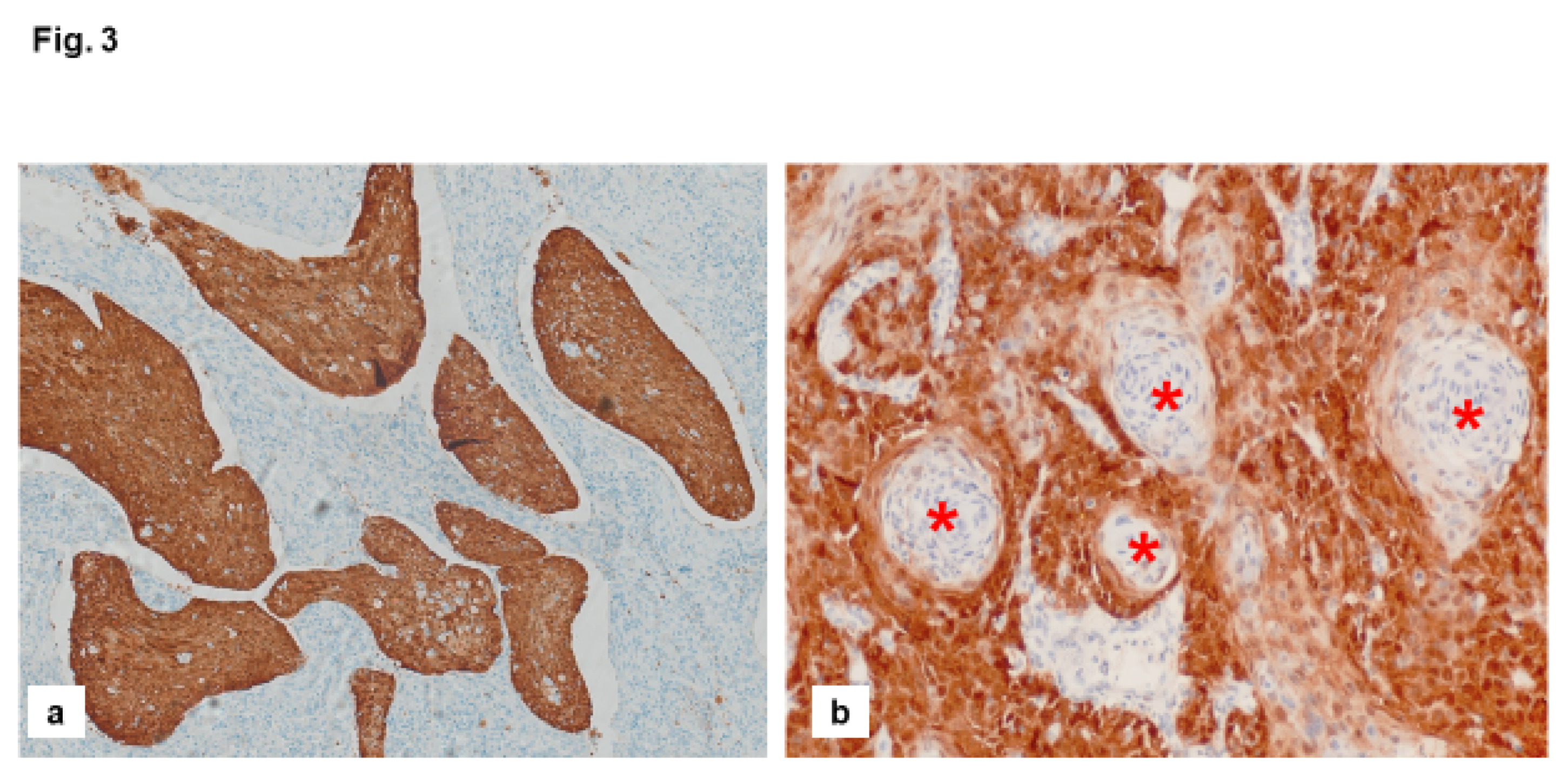

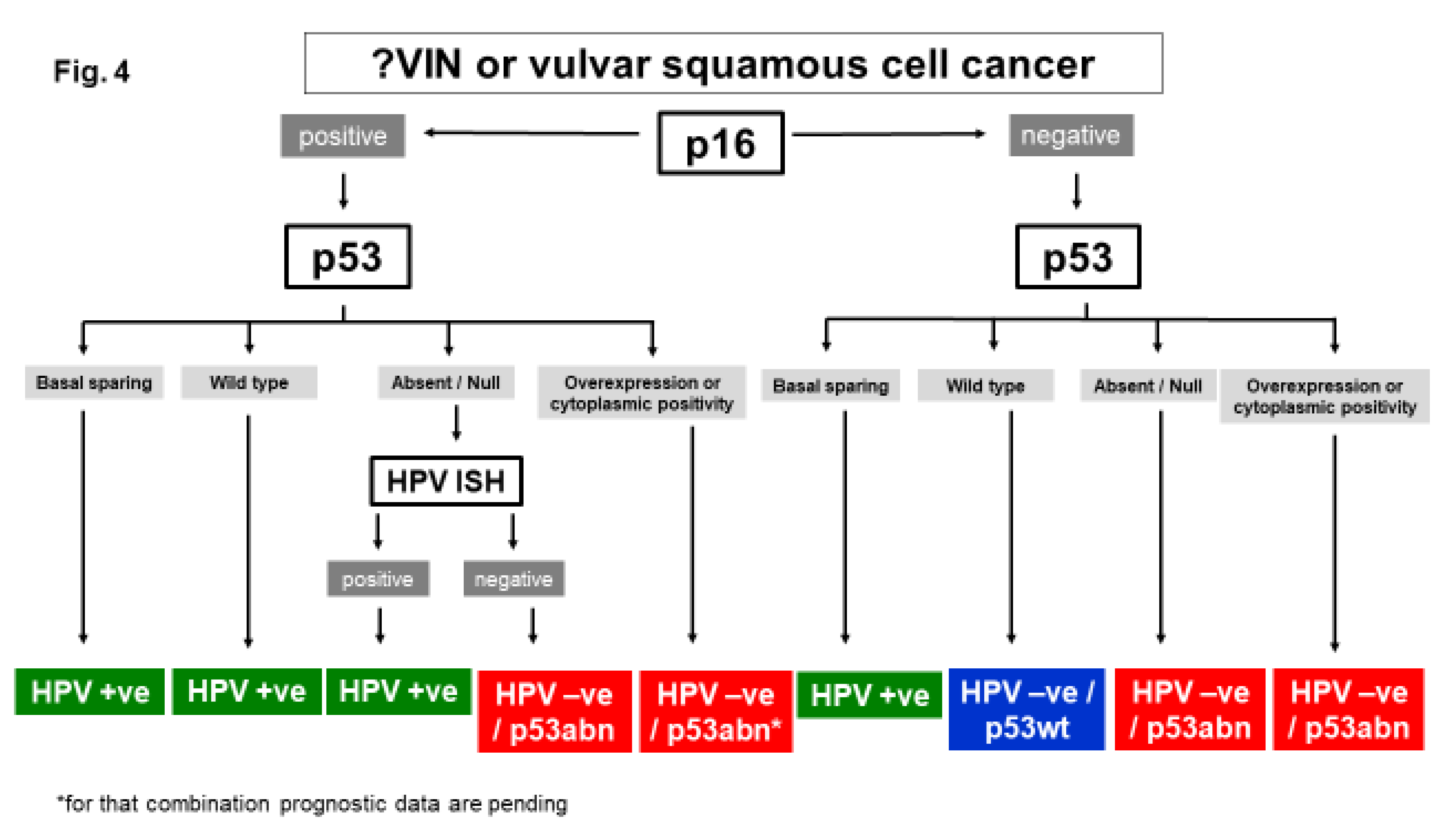

Diagnosis of Molecular Subtypes of VSCC

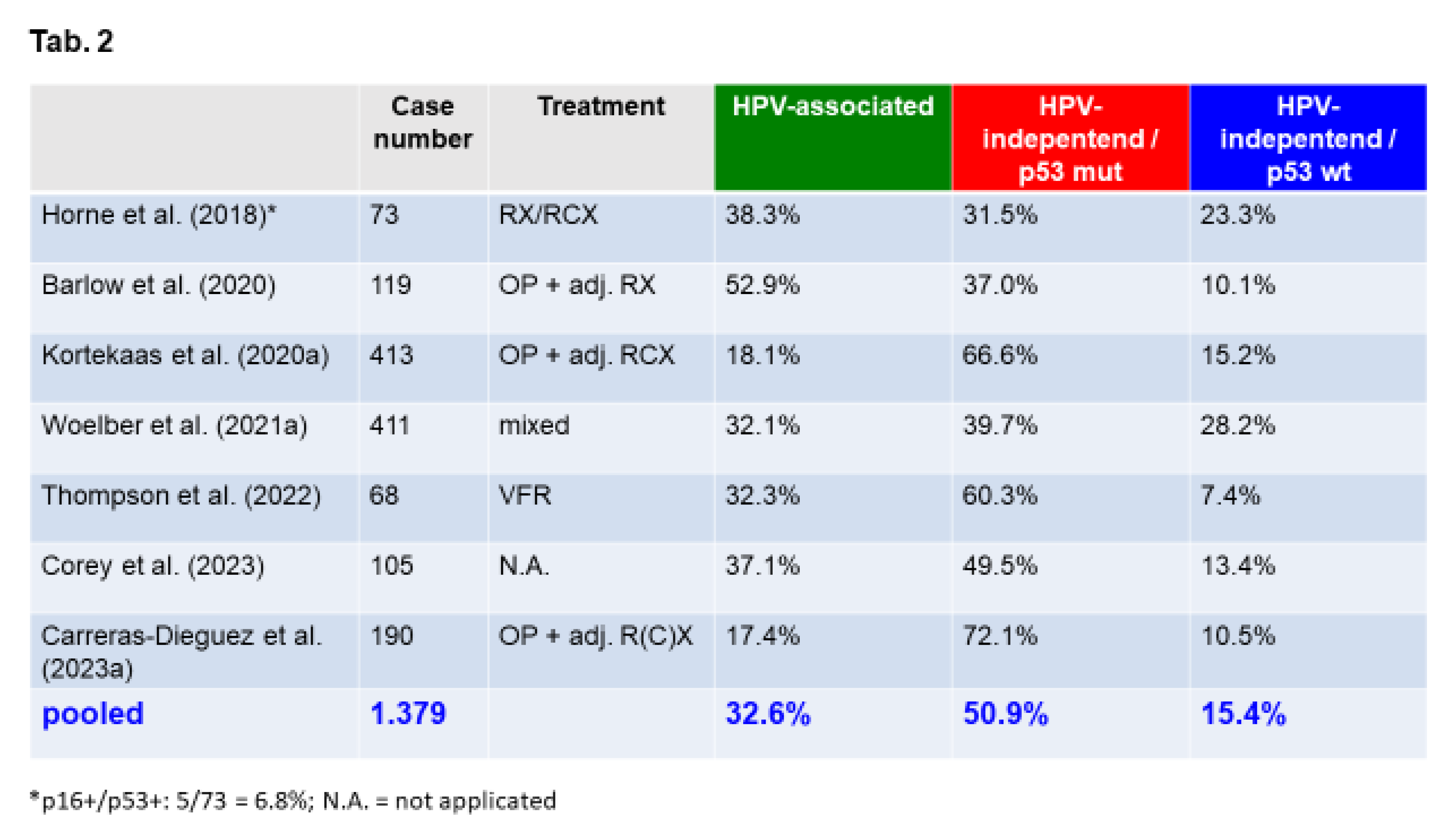

Accuracy of Molecular Subclassification of VSCC

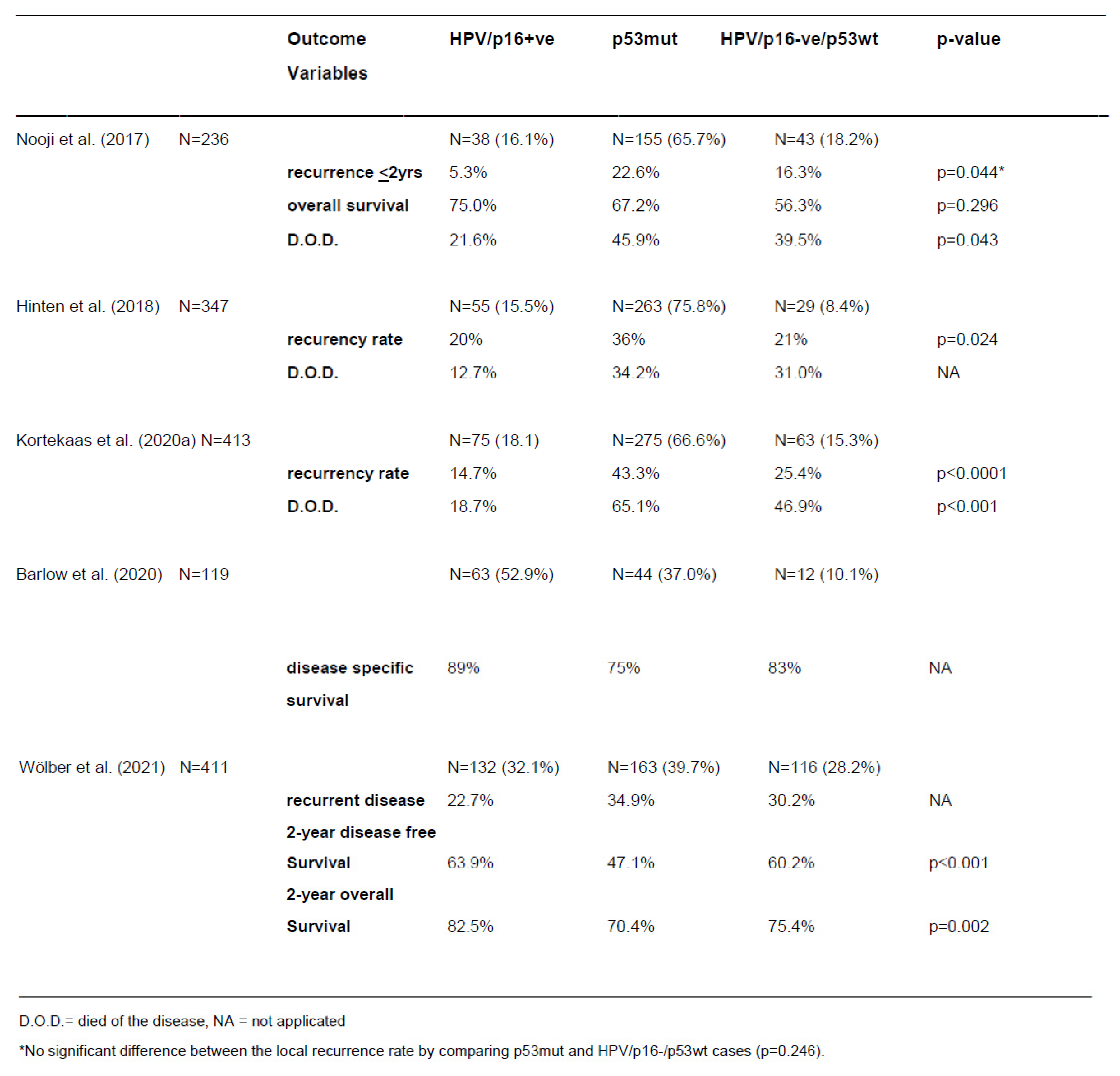

Prognostic Impact of Molecular Subtyping

HPV-Independent, p53 Wild Type VSCC: Clinical Features

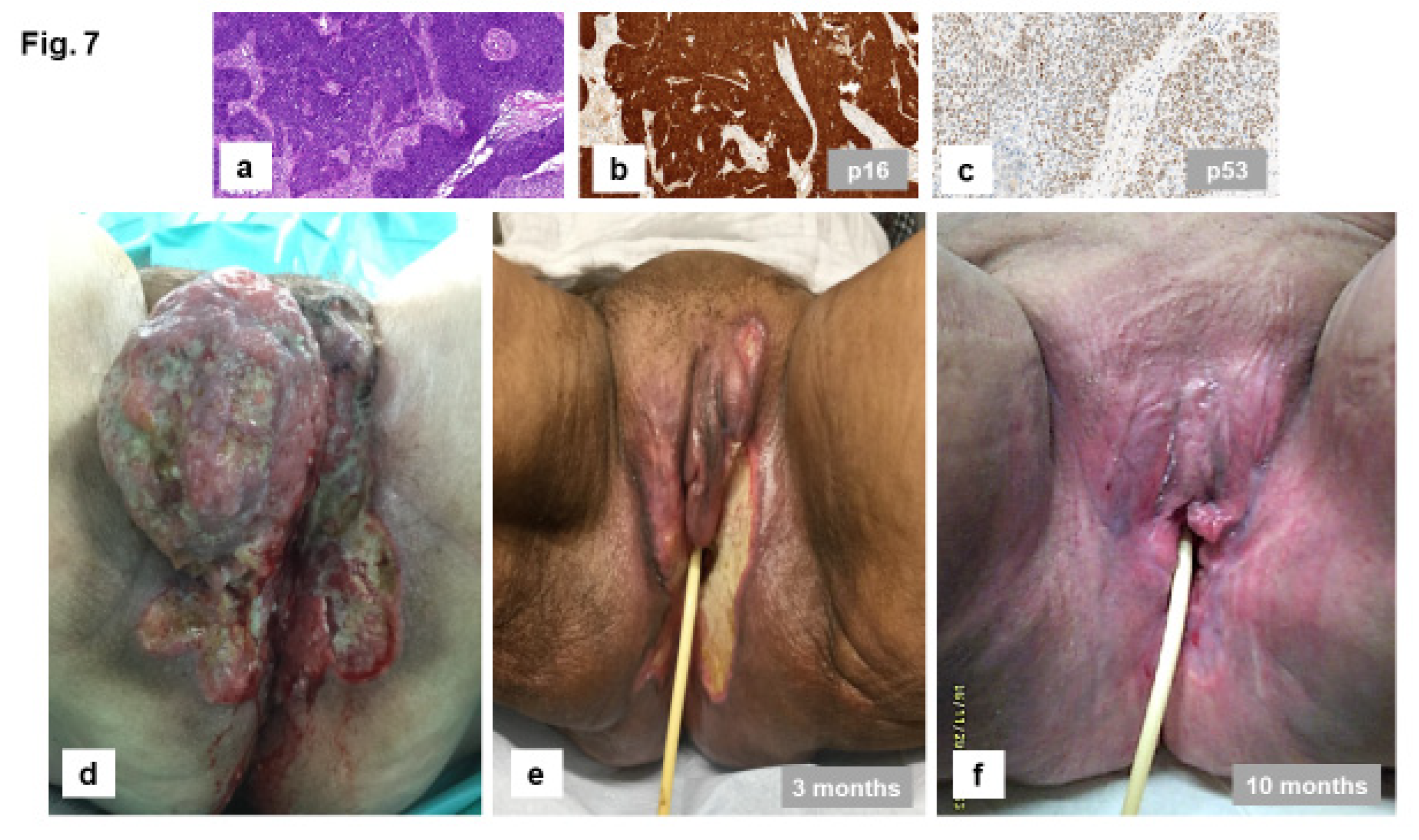

Future Directions

Conclusions

References

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Cuello, M.A.; Rogers, L.J. Cancer of the vulva: 2021 update. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 155 Suppl 1, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, G.; Capocaccia, R.; Trama, A.; Martínez-García, C. The burden of rare cancers in Europe. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 686, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslick, G.D. What is a Rare Cancer? Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2012, 26, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, E.L.; Kang, Y.-J.; Hacker, N.F.; Canfell, K. Changing Trends in Vulvar Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates in Australia Since 1982. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-J.; Smith, M.; Barlow, E.; Coffey, K.; Hacker, N.; Canfell, K. Vulvar cancer in high-income countries: Increasing burden of disease. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Bucchi, L.; Zamagni, F.; Baldacchini, F.; Crocetti, E.; Giuliani, O.; Ravaioli, A.; Vattiato, R.; Preti, M.; Tumino, R.; et al. Trends in Net Survival from Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Italy (1990-2015). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scampa, M.; Kalbermatten, D.F.; Oranges, C.M. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva: A Survival and Epidemiologic Study with Focus on Surgery and Radiotherapy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gilks, C.B. Vulval squamous cell carcinoma and its precursors. Histopathology 2020, 76, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.X.; Hoang, L.N. Squamous and Glandular Lesions of the Vulva and Vagina: What's New and What Remains Unanswered? Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2022, 15, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinten, F.; Molijn, A.; Eckhardt, L.; Massuger, L.F.A.G.; Quint, W.; Bult, P.; Bulten, J.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Hullu, J.A. de. Vulvar cancer: Two pathways with different localization and prognosis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 149, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortekaas, K.E.; Bastiaannet, E.; van Doorn, H.C.; van Vos Steenwijk, P.J. de; Ewing-Graham, P.C.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Akdeniz, K.; Nooij, L.S.; van der Burg, S.H.; Bosse, T.; et al. Vulvar cancer subclassification by HPV and p53 status results in three clinically distinct subtypes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Almadani, N.; Thompson, E.F.; Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Chen, J.; Ho, J.; Senz, J.; McConechy, M.K.; Chow, C.; Ta, M.; et al. Classification of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Precursor Lesions by p16 and p53 Immunohistochemistry: Considerations, Caveats, and an Algorithmic Approach. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, A.M.; Momeni-Boroujeni, A.; Vanderbilt, C.; Ladanyi, M.; Soslow, R. Molecular landscape of vulvovaginal squamous cell carcinoma: new insights into molecular mechanisms of HPV-associated and HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Pors, J.; Thompson, E.; Ho, J.; Prentice, L.; McConechy, M.; Aguirre-Hernandez, R.; Miller, R.; Leung, S.; Proctor, L.; et al. Molecular characterization of invasive and in situ squamous neoplasia of the vulva and implications for morphologic diagnosis and outcome. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allo, G.; Yap, M.L.; Cuartero, J.; Milosevic, M.; Ferguson, S.; Mackay, H.; Kamel-Reid, S.; Weinreb, I.; Ghazarian, D.; Pintilie, M.; et al. HPV-independent Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma is Associated With Significantly Worse Prognosis Compared With HPV-associated Tumors. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2020, 39, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, E.L.; Lambie, N.; Donoghoe, M.W.; Naing, Z.; Hacker, N.F. The Clinical Relevance of p16 and p53 Status in Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 3739075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, J.N.; Leung, S.C.Y.; Cheng, A.; Miller, D.; Talhouk, A.; Gilks, C.B.; Karnezis, A.N. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-independent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma has a worse prognosis than HPV-associated disease: a retrospective cohort study. Histopathology 2017, 71, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.F.; Hoang, L.; Höhn, A.K.; Palicelli, A.; Talia, K.L.; Tchrakian, N.; Senz, J.; Rusike, R.; Jordan, S.; Jamieson, A.; et al. Molecular subclassification of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: reproducibility and prognostic significance of a novel surgical technique. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras-Dieguez, N.; Saco, A.; del Pino, M.; Pumarola, C.; Del Campo, R.L.; Manzotti, C.; Garcia, A.; Marimon, L.; Diaz-Mercedes, S.; Fuste, P.; et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma arising on human papillomavirus-independent precursors mimicking high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion: a distinct and highly recurrent subtype of vulvar cancer. Histopathology 2023, 82, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, L.; Wallbillich, J.J.; Wu, S.; Farrell, A.; Hodges, K.; Xiu, J.; Nabhan, C.; Guastella, A.; Kheil, M.; Gogoi, R.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2023, 42, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurman, R.J.; Toki, T.; Schiffman, M.H. Basaloid and warty carcinomas of the vulva. Distinctive types of squamous cell carcinoma frequently associated with human papillomaviruses. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1993, 17, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toki, T.; Kurman, R.J.; Park, J.S.; Kessis, T.; Daniel, R.W.; Shah, K.V. Probable nonpapillomavirus etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva in older women: a clinicopathologic study using in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1991, 10, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannella, L.; Di Giuseppe, J.; Delli Carpini, G.; Grelloni, C.; Fichera, M.; Sartini, G.; Caimmi, S.; Natalini, L.; Ciavattini, A. HPV-Negative Adenocarcinomas of the Uterine Cervix: From Molecular Characterization to Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhry, C.; Lacchetti, C.; Rooper, L.M.; Jordan, R.C.; Rischin, D.; Sturgis, E.M.; Bell, D.; Lingen, M.W.; Harichand-Herdt, S.; Thibo, J.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Testing in Head and Neck Carcinomas: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement of the College of American Pathologists Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3152–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, F.; Longo, F.; Caponigro, F.; Sandomenico, F.; Guida, A.; Della Vittoria Scarpati, G.; Ottaiano, A.; Muto, P.; Ionna, F. Management of HPV-Related Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: Pitfalls and Caveat. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuhetty, D.; White, V.A.; Watanabe, R. Female genital tumours, 5. edition, 2020, ISBN 9789283245049.

- Hoang, L.; Webster, F.; Bosse, T.; Focchi, G.; Gilks, C.B.; Howitt, B.E.; McAlpine, J.N.; Ordi, J.; Singh, N.; Wong, R.W.-C.; et al. Data Set for the Reporting of Carcinomas of the Vulva: Recommendations From the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR). Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2022, 41, S8–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, U.G.; Crothers, B.A.; Otis, C.N.; Birdsong, G.G.; Movahedi-Lankarani, S.; Klepeis, V. Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Primary Carcinoma of the Vulva. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://documents.cap.org/protocols/Vulva_4.2.0.0.REL_CAPCP.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Oonk, M.H.M.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Mahner, S.; Mirza, M.R.; Fischerová, D.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Guillot, E.; Garganese, G.; Lax, S.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer - Update 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, F.L.; Rasmussen, C.L.; Frederiksen, M.H.; Andersen, K.K.; Kjaer, S.K. Prognostic Significance of HPV and p16 Status in Men Diagnosed with Penile Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2018, 27, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.-W.; Kwak, Y.-K. Current Evidence of a Deintensification Strategy for Patients with HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnaes, E.; Frederiksen, K.; Kiss, K.; Andersen, L.; Therkildsen, M.H.; Franzmann, M.B.; Specht, L.; Andersen, E.; Norrild, B.; Kjaer, S.K.; et al. Double positivity for HPV DNA/p16 in tonsillar and base of tongue cancer improves prognostication: Insights from a large population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 2598–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, C.G.; Jensen, D.H.; Carlander, A.-L.F.; Kiss, K.; Andersen, L.; Olsen, C.H.; Andersen, E.; Garnæs, E.; Cilius, F.; Specht, L.; et al. Novel nomograms for survival and progression in HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal cancer: a population-based study of 1,542 consecutive patients. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 71761–71772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, F.L.; Nielsen, D.M.B.; Frederiksen, M.H.; Rasmussen, C.L.; Kjaer, S.K. The prognostic value of p16 and p53 expression for survival after vulvar cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 152, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooij, L.S.; Haar, N.T. ter; Ruano, D.; Rakislova, N.; van Wezel, T.; Smit, V.T.H.B.M.; Trimbos, B.J.B.M.Z.; Ordi, J.; van Poelgeest, M.I.E.; Bosse, T. Genomic Characterization of Vulvar (Pre)cancers Identifies Distinct Molecular Subtypes with Prognostic Significance. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 6781–6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahoud, J.; Gleber-Netto, F.O.; McCormick, B.Z.; Rao, P.; Lu, X.; Guo, M.; Morgan, M.B.; Chu, R.A.; Martinez-Ferrer, M.; Eterovic, A.K.; et al. Whole-exome Sequencing in Penile Squamous Cell Carcinoma Uncovers Novel Prognostic Categorization and Drug Targets Similar to Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2021, 27, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelber, L.; Prieske, K.; Eulenburg, C.; Oliveira-Ferrer, L.; Gregorio, N. de; Klapdor, R.; Kalder, M.; Braicu, I.; Fuerst, S.; Klar, M.; et al. p53 and p16 expression profiles in vulvar cancer: a translational analysis by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie Chemo and Radiotherapy in Epithelial Vulvar Cancer study group. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 595.e1–595.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.S.; Karnezis, A.N.; Jordan, S.; Singh, N.; McAlpine, J.N.; Gilks, C.B. p16 Immunostaining Allows for Accurate Subclassification of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma Into HPV-Associated and HPV-Independent Cases. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2016, 35, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.; Landolfi, S.; Olivella, A.; Lloveras, B.; Klaustermeier, J.; Suárez, H.; Alòs, L.; Puig-Tintoré, L.M.; Campo, E.; Ordi, J. p16 overexpression identifies HPV-positive vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, T.M.; Colgan, T.J.; Thomas Cox, J.; Heller, D.S.; Henry, M.R.; Luff, R.D.; McCalmont, T.; Nayar, R.; Palefsky, J.M.; Stoler, M.H.; et al. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2013, 32, 76–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh N, Gilks B, Wong RWC, McCluggage WG, Herrington C. Interpretation of p16 Immunohistochemistry In Lower Anogenital Tract Neoplasia. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bgcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final-BAGP-UKNEQAS-cIQC-project-p16-interpretation-guide-2018.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Jordan, R.C.; Lingen, M.W.; Perez-Ordonez, B.; He, X.; Pickard, R.; Koluder, M.; Jiang, B.; Wakely, P.; Xiao, W.; Gillison, M.L. Validation of methods for oropharyngeal cancer HPV status determination in US cooperative group trials. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigge, E.-S.; Arbyn, M.; Knebel Doeberitz, M. von; Reuschenbach, M. Diagnostic accuracy of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolás, I.; Saco, A.; Barnadas, E.; Marimon, L.; Rakislova, N.; Fusté, P.; Rovirosa, A.; Gaba, L.; Buñesch, L.; Gil-Ibañez, B.; et al. Prognostic implications of genotyping and p16 immunostaining in HPV-positive tumors of the uterine cervix. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poetsch, M.; Schuart, B.-J.; Schwesinger, G.; Kleist, B.; Protzel, C. Screening of microsatellite markers in penile cancer reveals differences between metastatic and nonmetastatic carcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 2007, 20, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poetsch, M.; Hemmerich, M.; Kakies, C.; Kleist, B.; Wolf, E.; vom Dorp, F.; Hakenberg, O.W.; Protzel, C. Alterations in the tumor suppressor gene p16(INK4A) are associated with aggressive behavior of penile carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2011, 458, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortekaas, K.E.; Solleveld-Westerink, N.; Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Rutten, T.A.; Poelgeest, M.I.E.; Gilks, C.B.; Hoang, L.N.; Bosse, T. Performance of the pattern-based interpretation of p53 immunohistochemistry as a surrogate for TP53 mutations in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology 2020, 77, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakislova, N.; Clavero, O.; Alemany, L.; Saco, A.; Quirós, B.; Lloveras, B.; Alejo, M.; Pawlita, M.; Quint, W.; del Pino, M.; et al. "Histological characteristics of HPV-associated and -independent squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva: A study of 1,594 cases". Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras-Dieguez, N.; Saco, A.; del Pino, M.; Marimon, L.; Del López Campo, R.; Manzotti, C.; Fusté, P.; Pumarola, C.; Torné, A.; Garcia, A.; et al. Human papillomavirus and p53 status define three types of vulvar squamous cell carcinomas with distinct clinical, pathological, and prognostic features. Histopathology 2023, 83, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, Z.D.; Dohopolski, M.J.; Pradhan, D.; Bhargava, R.; Edwards, R.P.; Kelley, J.L.; Comerci, J.T.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Courtney-Brooks, M.B.; Bockmeier, M.M.; et al. Human papillomavirus infection mediates response and outcome of vulvar squamous cell carcinomas treated with radiation therapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 151, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier-Cloutier, B.; Kortekaas, K.E.; Thompson, E.; Pors, J.; Chen, J.; Ho, J.; Prentice, L.M.; McConechy, M.K.; Chow, C.; Proctor, L.; et al. Major p53 immunohistochemical patterns in in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva and correlation with TP53 mutation status. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, L.; Hoang, L.; Moore, J.; Thompson, E.; Leung, S.; Natesan, D.; Chino, J.; Gilks, B.; McAlpine, J.N. Association of human papilloma virus status and response to radiotherapy in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelber, L.; Prieske, K.; Eulenburg, C. zu; Corradini, S.; Petersen, C.; Bommert, M.; Blankenstein, T.; Hilpert, F.; Gregorio, N. de; Iborra, S.; et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and local recurrence in vulvar cancer - a subset analysis of the AGO-CaRE-1 study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 164, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lou, J. Prognostic Value of Overexpressed p16INK4a in Vulvar Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohopolski, M.J.; Horne, Z.D.; Pradhan, D.; Bhargava, R.; Edwards, R.P.; Kelley, J.L.; Comerci, J.T.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Courtney-Brooks, M.; Berger, J.L.; et al. The Prognostic Significance of p16 Status in Patients With Vulvar Cancer Treated With Vulvectomy and Adjuvant Radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, M.L.; Allo, G.; Cuartero, J.; Pintilie, M.; Kamel-Reid, S.; Murphy, J.; Mackay, H.; Clarke, B.; Fyles, A.; Milosevic, M. Prognostic Significance of Human Papilloma Virus and p16 Expression in Patients with Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma who Received Radiotherapy. Clin. Oncol. (R Coll. Radiol) 2018, 30, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.J.; Howitt, B.; Catalano, P.; Tanaka, C.; Murphy, R.; Cimbak, N.; DeMaria, R.; Bu, P.; Crum, C.; Horowitz, N.; et al. Prognostic importance of human papillomavirus (HPV) and p16 positivity in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva treated with radiotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, G.; Näsman, A.; Jonsson, C.; Ehrsson, R.J.; Jacobsson, H.; Danielsson, K.G.; Dalianis, T.; Källström, B.N.; Larson, B. Presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) and sentinel node. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 117, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooij, L.S.; Brand, F.A.M.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Hullu, J.A. de; van Poelgeest, M.I.E. Risk factors and treatment for recurrent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 106, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, L.; Mathey, S.; Prieske, K.; Kuerti, S.; Hillen, C.; Burandt, E.; Coym, A.; Mueller, V.; Schmalfeldt, B.; Jaeger, A. Targeted Therapeutic Approaches in Vulvar Squamous Cell Cancer (VSCC): Case Series and Review of the Literature. Oncol. Res. 2021, 28, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, G.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Inzani, F.; Fagotti, A.; Della Corte, L.; Gentileschi, S.; Tagliaferri, L.; Zannoni, G.F.; Scambia, G.; Garganese, G. Molecular pathways in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: implications for target therapeutic strategies. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, L.; Marchesini, M.; Roti, G. Targeting oncogenic Notch signaling with SERCA inhibitors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribera-Cortada, I.; Guerrero-Pineda, J.; Trias, I.; Veloza, L.; Garcia, A.; Marimon, L.; Diaz-Mercedes, S.; Alamo, J.R.; Rodrigo-Calvo, M.T.; Vega, N.; et al. Pathogenesis of Penile Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Molecular Update and Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Gilks, C.B.; Wong Wing-Cheuk, R.; McCluggage, W.G.; Herrington, C.S. Final-BAGP-UKNEQAS-cIQC-project-p16-interpretation-guide-2018 2018.

- Köbel, M.; Kang, E.Y. The Many Uses of p53 Immunohistochemistry in Gynecological Pathology: Proceedings of the ISGyP Companion Society Session at the 2020 USCAP Annual9 Meeting. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2021, 40, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).