1. Introduction

Obesity is a chronic disease that can cause various health problems due to excessive fat deposition in the body. In the World Obesity Atlas 2023 report, 38% of the global population is overweight or obese, and this proportion is expected to rise rapidly over time [

1]. Obesity is a major contributor to cancer, cardiovascular disease, and early death and significantly affects various organs. One of the significant consequences of obesity is its crucial role in the development of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [

2,

3,

4].

MASLD is a broad-spectrum liver disease characterized by fat accumulation in the liver in the absence of alcohol. It starts from hepatic steatosis (HS), a condition in which there are only fat deposits in the liver tissue, and when liver function is deteriorated and an inflammatory response occurs, it becomes metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). When fibrosis worsens and scarring occurs in the tissue, it progresses to hepatofibrosis (HF) and eventually progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

5]. MASLD is also strongly associated with various metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. MASLD is known to occur in more than 65% of obese individuals, and its prevalence is rising in parallel with increasing obesity rates [

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying the occurrence and progression of MASLD are not yet known. Therefore, no therapeutic drugs have been developed.

Ferroptosis is a ferrous (Fe

2+)-dependent cell death process that is bioenergetically distinct from apoptosis. Ferroptosis is closely related to several diseases such as oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and autophagy [

10]. Numerous studies have revealed its involvement in the occurrence and progression of various diseases such as stroke, cancer, chronic mental illness, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes [

10,

11,

12]. Excessive intracellular iron accumulation and lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) are required to initiate ferroptosis. ROS generated by the catalytic action of iron initiate lipid peroxidation and cause ferroptosis [

10]. The liver is the primary organ that regulates lipid metabolism and iron homeostasis [

13,

14]. If adipose tissue accumulates in the liver, lipid ROS levels can increase, and iron accumulation can also occur. Therefore, lipid accumulation and iron imbalance caused by obesity can be considered as conditions that promote ferroptosis in the liver [

15,

16,

17]. Two previous studies demonstrated that ferroptosis plays an important role in the progression and worsening of MASH [

18,

19]; however, these studies were conducted in mouse models already induced with MASH. Specific research investigating the role of ferroptosis in the development of hepatic steatosis and its progression to MASH has not yet been conducted.

As simple hepatic steatosis progresses to MASH, the incidence of liver cirrhosis increases along with the risk of progression to liver failure and liver cancer. Therefore, prevention of hepatic steatosis and its progression to MASH is critical. Although oxidative stress is thought to play an important role in liver cell damage and the progression to MASH, the exact mechanisms involved in the development of hepatic steatosis and its progression to MASH remain unclear. In the present study, we investigated the role of ferroptosis in the development of hepatic steatosis and its progression to MASH in the context of obesity. Additionally, we aimed to determine whether the modulation of ferroptosis could prevent or facilitate recovery from hepatic steatosis and MASH.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals & Experimental Design

Six-week-old female C57BL/6J-Jms Slc wild-type mice (n = 8) and six-week-old female C57BL/6J ob/ob mice (n = 16) were used. Female C57BL/6J-ob/ob and wild-type mice were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). After a two-week adaptation period, mice were divided into three groups that included C57BL/6 (n=8), ob/ob (n = 8), and ob/ob + ferrostatin-1 (FER) (n = 8). The mice were maintained on a standard chow diet. The ob/ob + FER group was administered ferrostatin-1 for 8 weeks (intraperitoneal injection, 5 μM/kg/day) at 3 days per week. C57BL/6 and ob/ob mice were injected with equal volumes of normal saline solution using the same injection schedule. The ob/ob group underwent tests at the start of the experiment (ob/ob 8wks) and at 8 weeks (ob/ob 16wks) to observe the progression of fatty liver and hepatitis as obesity progressed. Eight weeks after drug injection, the animals were respiratory-anesthetized, blood was collected from the inferior vena cava for biomarker testing, and they were then sacrificed. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of our hospital (No. PNUH-2022-200)

2.2. Serum and Tissue Collection

Blood samples were extracted from the inferior vena cava using a 1 ml syringe and coagulated for 2 h at room temperature. After centrifugation, serum samples were removed and stored at -80°C until analysis. Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total cholesterol, and blood glucose levels were measured.

2.3. Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation in the liver tissue was evaluated by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) levels using a Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit (Abcam, UK) as previously described. Briefly, liver tissue was homogenized in TBA solution, and samples and standards were prepared. These were incubated at 95°C for 60 min and then cooled in an ice bath for 10 min. The lipid peroxidation assay of malondialdehyde (MDA) with TBA produced TBA-MDA with a colorimetric (532 nm) readout. This assay colorimetrically detects MDA levels as low as 1 nmol/well.

2.4. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

Liver samples were isolated from each rat and fixed overnight in 4% formalin. An automatic tissue processor was used for paraffin embedding (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany; Leica, TP1020, a semi-enclosed benchtop tissue processor) and dispensing (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany; Leica EG1150H, a heated paraffin embedding module). Cross-sections (8-μm thick) of livers were placed on glass slides, and sections were prepared for hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. For staining analyses, the slides were deparaffinized with xylene and then hydrated through a series of washes in 100%, 85%, 75%, and 50% ethanol mixed with water. The central part of the tissue was selected for representative figures using 200x images acquired by light microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany, Leica DM4000/600M, versatile upright microscope for material analysis).

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Liver tissue RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, USA). A reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used at 42 ℃ for 60 min and 95℃ for 10min according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The qPCR was performed according to the SYBR® Green PCR protocol (Applied Biosystems). Gene-specific PCR products were continuously analyzed using an ABI PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems, USA). Primer sequences were synthesized by Macrogen.

Normalization was performed based on the differences between the target gene cycle thresholds (Ct) and Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression level to calculate the Ct:target gene Ct ration (Δ Ct). The primer sequences are listed in

Table 1.

2.6. Western Blot

The protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose (NC) blotting membrane (Amersham, Germany), and this was followed by incubation with 5% phospho-blocker at room temperature for 1 h.

The membrane was incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with primary antibodies that included anti-LC3B antibody (1:1000), anti-NCOA4 antibody (1:1000) and β-actin antibody. The next day, the NC membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibodies (1:5000) for 2 h at room temperature and developed using an ECL kit (Amersham, Germany).

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight, Food Intake, and Serum Glucose Level

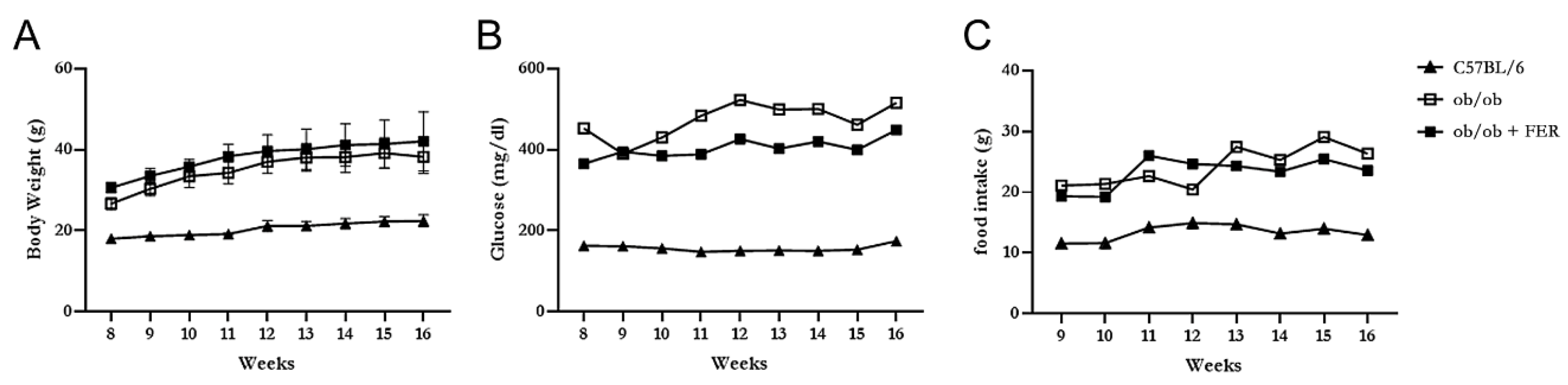

The C57BL/6, ob/ob, and ob/ob + FER groups were monitored weekly for food intake, body weight, and serum glucose levels for 8 weeks. The C57BL/6 group maintained a relatively stable food intake without significant changes from the start of the experiment through week 8, with body weight exhibiting a slight increase and remaining in the 20 g range. In contrast, both the ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups exhibited nearly double the food intake compared to that of the C57BL/6 group, with the body weight gradually increasing to approximately 40 g. Both groups exhibited significant differences in food intake and body weight compared to that of the C57BL/6 group (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 1 A and C). The serum glucose level in the C57BL/6 group remained consistently below 200 mg/dl throughout the 8 weeks, whereas the ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups exhibited significantly higher levels that exceeded 400 mg/dl (

p < 0.05), with more variability than that of the C57BL/6 group during the same period (

Figure 1B). No significant differences in food intake, body weight, or serum glucose levels were observed between the ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups. These data confirmed that the ob/ob group serves as a suitable obese mouse model, and consistent administration of ferrostatin for 8 weeks did not significantly affect body weight or serum glucose levels, indicating that ferrostatin does not exert a direct influence on obesity.

3.2. Lipogenesis and Steatosis in Obese Mice and Inhibitory Effect of Ferroptosis Inhibitor

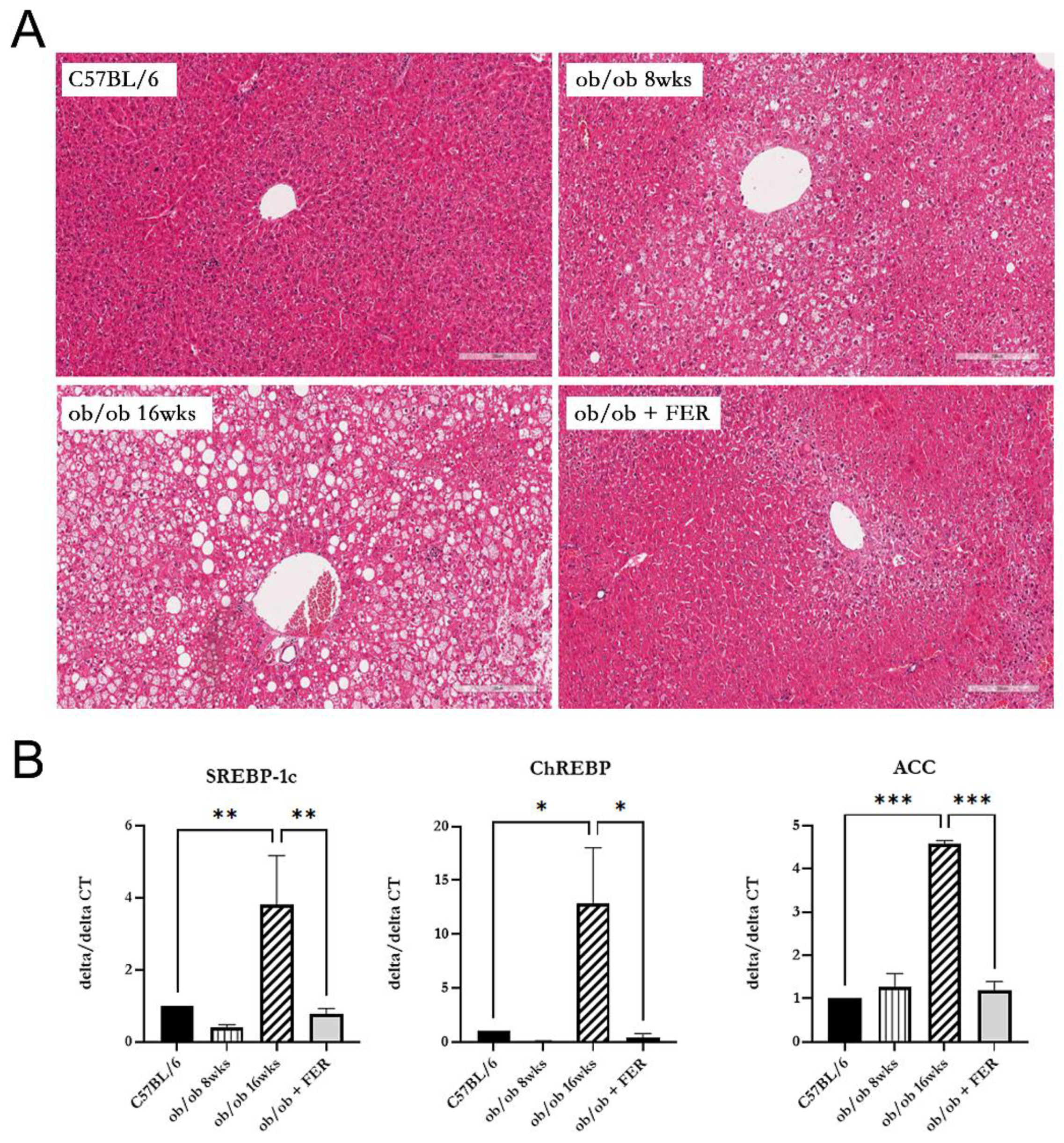

We compared lipogenesis and steatosis in the livers of the three groups. The liver morphology of C57BL/6 mice was normal. The ob/ob group exhibited pre-existing lipid droplets at the start of the experiment, and significant steatosis was evident by week 8 The ob/ob + FER group, treated with the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 for eight weeks, exhibited liver tissue similar to that of the control C57BL/6 mice, with nearly all lipid droplets eliminated compared to those of the initial ob/ob mice (

Figure 2A).

To assess the degree of lipogenesis in the livers of the three groups, we compared the expression levels of the lipogenesis-related markers SREBP-1c, ChREBP, and ACC. At 8 weeks, the expression levels of SREBP-1c and ChREBP in the ob/ob group were slightly lower than those in the C57BL/6 and ob/ob + FER groups, although no significant differences were observed. However, at 16 weeks, these levels significantly increased compared to the other two groups, exhibiting over three-fold and ten-fold increases (

p < 0.01 and < 0.05, respectively). ACC exhibited similar levels in the C57BL/6 and ob/ob + FER groups at 8 weeks, but at 16 weeks, it exhibited a more than four-fold increase compared to levels in the other groups, indicating a significant difference (

p < 0.001). Importantly, the ob/ob + FER group maintained levels of SREBP-1c, ChREBP, and ACC similar to those in the normal control C57BL/6 group (

Figure 2B).

Comparing the data regarding steatosis and lipogenesis across the three groups, the obese ob/ob model mice initially exhibited no significant differences from the C57BL/6 group. However, by week 16, both steatosis and lipogenesis had progressed significantly, diverging from those in the C57BL/6 group. Remarkably, administration of ferrostatin-1 to ob/ob mice for 8 weeks normalized both steatosis and lipogenesis to levels comparable to those in the C57BL/6 group.

3.3. Progression of Ferroptosis in Obese Mice and Evaluation of the Efficacy of Ferrostatin for Attenuating Ferroptosis

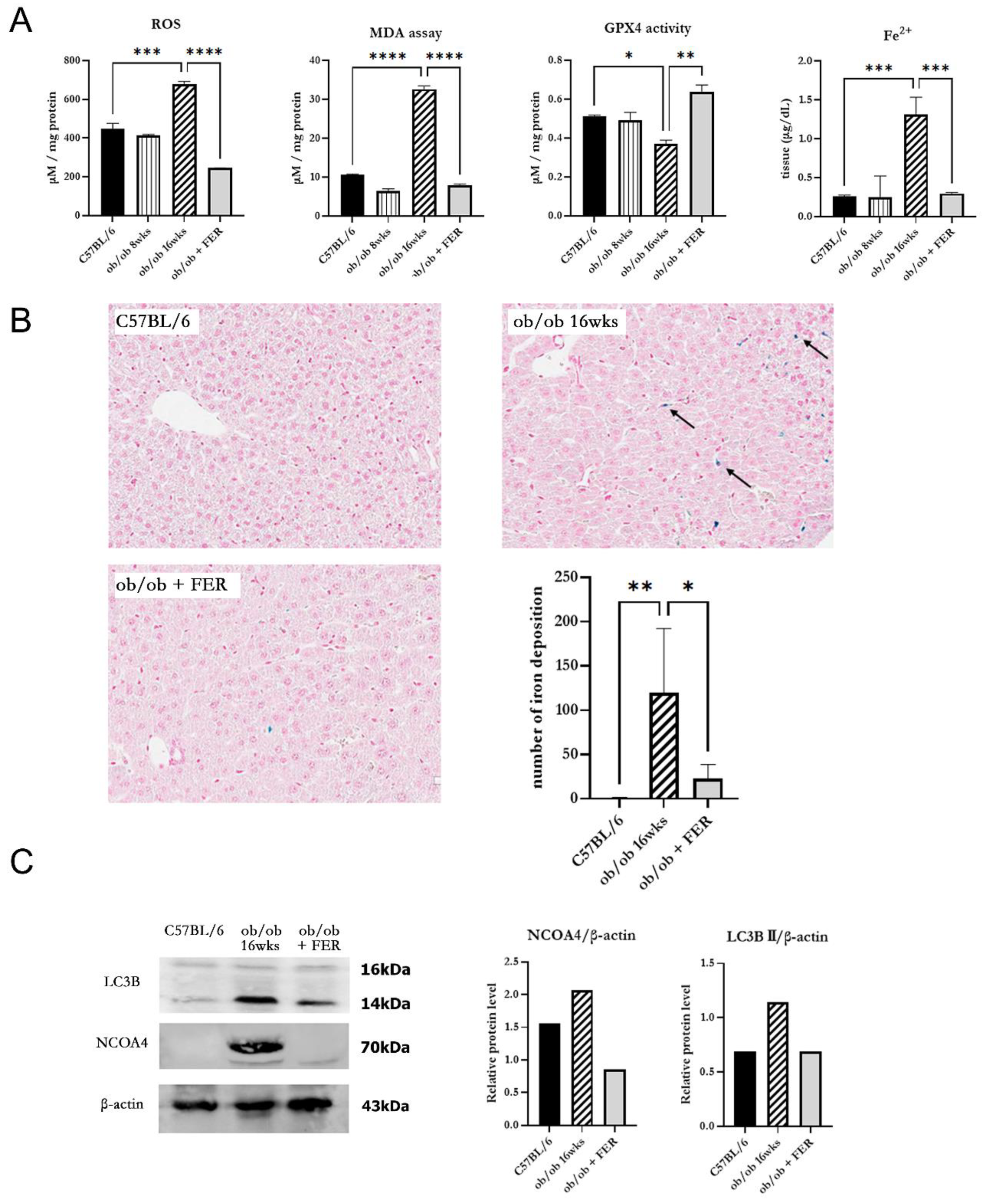

To investigate changes in oxidative stress due to obesity, we examined intracellular ROS generation in the three groups. The ROS levels in the ob/ob mouse group were similar to those in the C57BL/6 group at 8 weeks but were significantly increased by 16 weeks (

p < 0.05). Conversely, the ob/ob + FER group demonstrated a significant reduction in ROS levels that were lower than those in the C57BL/6 and 8-week ob/ob groups. MDA, a product of lipid peroxidation, is an indicator of ferroptosis. At 8 weeks, the MDA concentration in ob/ob mice did not differ significantly from that in the C57BL/6 group, but by 16 weeks, it was significantly elevated, exhibiting levels that were three-fold higher than those in the C57BL/6 group (

p < 0.001). In contrast, ob/ob mice treated with ferrostatin-1 exhibited a return to normal MDA levels (

p < 0.001). GPX4 is a critical regulator of ferroptosis. The activity of GPX4, a key ferroptosis biomarker, was significantly lower in the 16-week ob/ob group than it was in the C57BL/6 group. GPX4 activity was significantly higher in the ob/ob + FER group than it was in the ob/ob group (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 3A).

To assess iron overload, another axis of ferroptosis, we measured intracellular ferrous iron (Fe2

+) levels and used Prussian blue iron staining to detect iron accumulation in the liver tissues of the three groups. The levels of intracellular ferrous iron were similar across the C57BL/6, 8-week ob/ob, and ob/ob + FER groups, with significant elevation observed only in the 16-week ob/ob mice (

p < 0.001). Prussian blue staining confirmed iron accumulation in tissues exclusively from 16-week ob/ob mice (

Figure 3B).

NCOA4 is a selective cargo receptor that mediates autophagic turnover of ferritin into ferrous iron. NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy ultimately increases oxidative iron levels and promotes lipid peroxidation. Western blot analysis revealed that LC3B and NCOA4 were expressed in 16-week ob/ob mice, whereas their expression was significantly reduced in the ob/ob + FER group (

Figure 3C).

These results indicate that as obesity progresses, intracellular oxidative iron levels increase, driven by NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy. Additionally, ferrostatin suppressed the expression of NCOA4, thereby attenuating the accumulation of intra cellular Fe2+.

3.4. Effect of Ferrostatin on the Progress of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) in Obese Mice

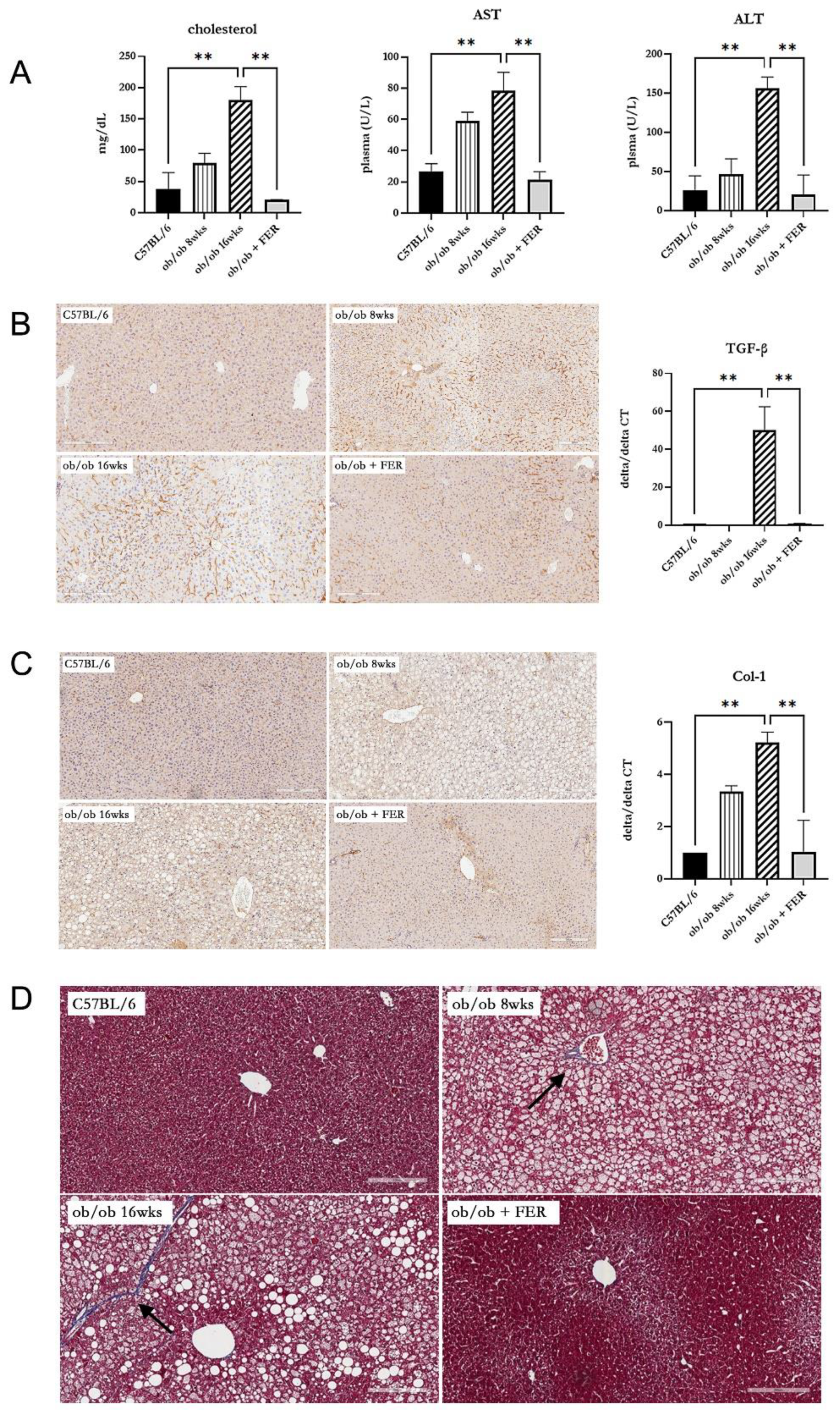

To assess the impact of the duration of obesity on the liver, we evaluated liver function, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver tissues of the three groups. Serum cholesterol, AST, and ALT measurements revealed that the ob/ob group at 8 weeks exhibited higher levels than did C57BL/6 mice, with the 16-week ob/ob group exhibiting even more significant increases. The levels in the ob/ob + FER group were similar to those in the C57BL/6 group (

p < 0.01). (

Figure 4A). These findings suggest that prolonged obesity worsens liver function and that treatment with ferrostatin-1 can normalize liver function, even in the context of long-term obesity. To confirm inflammatory responses in liver tissues, TGF- immunohistochemical staining revealed increased staining intensity from 8 to 16 weeks in the ob/ob group, while staining decreased in the ob/ob + FER group. The mRNA expression of TGF- was also significantly elevated in the 16-week ob/ob group, but it became normalized in the ob/ob + FER group (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 4B). Collagen type I staining also indicated heightened expression in the ob/ob group compared to that in the C57BL/6 group, with greater levels observed at 16 weeks than at 8 weeks. The ob/ob + FER group returned to levels similar to those observed in the C57BL/6 group. The mRNA expression of collagen type I was also significantly elevated in the 16-week ob/ob group but was normalized in the ob/ob + FER group (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 4C). Masson’s trichrome staining, used to assess the degree of fibrosis in the liver tissue, exhibited a similar pattern. No staining was observed in the C57BL/6 group, whereas the ob/ob group exhibited weak staining at 8 weeks that intensified at 16 weeks. No staining was observed in the ob/ob + FER group (

Figure 4D).

Collectively, these three immunohistochemical staining results indicate that liver inflammation and fibrosis in obese mice progressed over time, whereas treatment with ferrostatin effectively normalized both inflammation and fibrosis.

3.5. Induction of the Polarization from M1 to M2 Macrophages by Ferrostatin

After confirming that inflammation in the liver of obese mice improved with ferrostatin treatment, we investigated the changes in macrophage types across the three groups. We measured the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-2, and IL-4) indicative of M1-type macrophages and anti-inflammatory cytokines (Fizz1, Arg-1, and CD11b) produced by M2-type macrophages. The 16-week ob/ob group exhibited significantly higher expression levels of TNF-alpha, IL-2, and IL-4 compared to those of the other groups, while Fizz1, Arg-1, and CD11b exhibited levels similar to those of the C57BL/6 group (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 5A). Conversely, treatment with ferrostatin shifted M1 inflammatory macrophages to M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages in the livers of ob/ob mice by inhibiting TNF-alpha, IL-2, and IL-4 while increasing Fizz1, Arg-1, and CD11b (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 5B).

When correlating these results with the immunohistochemical staining findings presented in

Figure 4, we observed that as obesity progressed, M1 macrophages became activated, leading to chronic inflammation and subsequent fibrosis. However, treatment with ferrostatin resulted in the repolarization of M1 to M2 macrophages, facilitating recovery from liver inflammation and fibrosis.

3.6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Obese Mice

We investigated the morphology and function of mitochondria in hepatic cells of obese mice. Electron microscopy of 16-week ob/ob mice revealed mitochondria with increased membrane density, loss of cristae, and overall contraction compared to those in the C57BL/6 group. In contrast, the ob/ob + FER group exhibited mitochondria with a normalized membrane structure and cristae levels comparable to those of the C57BL/6 group (

Figure 6A). Additionally, the activities of GSH and SOD that assess mitochondrial function were significantly decreased in the 16-week ob/ob mice but were restored to normal levels in the ferrostatin-treated group (

p < 0.001) (

Figure 6B).

4. Discussion

In this study, we elucidated the critical role of ferroptosis at each stage of the progression from hepatic steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) in obese mice, revealing that the inhibition of ferroptosis can serve as an effective strategy to prevent the progression of fatty liver and MASH. Research on the role of ferroptosis in metabolic liver diseases has recently gained attention [

15,

16,

17,

20,

21,

22]. Due to the characteristics of the liver, where lipid peroxidation occurs readily, the hepatic cellular environment is inherently conducive to ferroptosis. Therefore, ferroptosis significantly contributes to hepatocyte damage and inflammatory responses in MASLD. Studies conducted in MASH mouse models have emphasized that ferroptosis contributes to liver inflammation and fibrosis progression, thereby exacerbating the disease. Additionally, it possesses the potential to delay liver disease progression and improve therapeutic outcomes by regulating ferroptosis [

18,

19]. However, as previous studies were conducted in mouse models that induced MASH, ferroptosis could only be observed in the process of worsening hepatitis when hepatitis had already occurred, and the role of ferroptosis in the development of hepatic steatosis and hepatitis in obesity remains unknown. There is a definite difference between the starting point of this study and those of previous studies. In this study, we directly observed the process of developing obesity into hepatic steatosis and hepatitis using an ob/ob mouse model that induces obesity due to the mutation of the leptin gene. We confirmed for the first time that ferroptosis plays an important role in the occurrence of hepatic steatosis and hepatitis and that this process can be prevented by inhibiting ferroptosis.

In the ob/ob mouse model, ferroptosis is associated with increased oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by elevated levels of MDA and reduced GPX4 activity. These results align with existing literature highlighting the role of oxidative stress in liver pathology [

18,

19]. The significant increase in lipid peroxidation markers in the ob/ob group suggests that as hepatic steatosis progresses, the liver becomes more susceptible to ferroptosis, exacerbating metabolic dysfunction. Importantly, ferrostatin administration mitigated these effects, normalized lipid peroxidation and GPX4 activity, and significantly improved liver histology. These results indicate that the inhibition of ferroptosis can prevent the progression of hepatic steatosis to the more severe stages of MASLD. This finding is crucial, as it suggests a potential therapeutic avenue for managing obesity-related liver diseases.

Furthermore, the results demonstrate a clear relationship between iron overload and ferroptosis. Ferroptosis, a unique form of iron-related cell death, is critically dependent on iron metabolism and is promoted by intracellular iron accumulation promotes this process [

23,

24,

25]. Consequently, understanding iron metabolism is crucial for understanding the mechanisms underlying ferroptosis. However, previous studies investigating ferroptosis in MASH have not adequately analyzed iron metabolism [

18,

19]. In the present study, the increased levels of intracellular ferrous iron in ob/ob mice, coupled with the expression of NCOA4, highlighted the role of ferritinophagy in the accumulation of reactive iron species. The reduced expression of NCOA4 following ferrostatin treatment underscores the potential of targeting this pathway to limit oxidative damage and subsequent cell death.

Inflammation observed in the liver tissues of ob/ob mice is indicative of a chronic inflammatory state associated with obesity. During the immune response, M1 macrophages are initially activated to address foreign materials, and this is followed by M2 macrophage activation to facilitate tissue recovery [

26]. However, if M1 to M2 polarization does not occur, continuous activation of M1 macrophages leads to inadequate tissue repair and fibrosis. This phenomenon has been observed in various chronic inflammatory diseases [

27,

28], and previous studies have confirmed an increased M1/M2 ratio in obese mice [

29]. Our finding of a shift from M1 to M2 macrophage polarization following ferrostatin treatment suggests that ferroptosis influences the inflammatory microenvironment of the liver. M1 macrophages promote inflammation, whereas M2 macrophages exhibit anti-inflammatory effects. The decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines along with the increase in anti-inflammatory markers further supports the notion that ferroptosis modulation can have systemic anti-inflammatory effects that are critical for liver health.

In terms of mitochondrial health, ob/ob mice exhibited significant mitochondrial dysfunction characterized by structural abnormalities and decreased enzyme activity. Ferrostatin treatment not only restored mitochondrial morphology but also improved mitochondrial function, suggesting that ferroptosis contributes to mitochondrial impairment in obesity. This restoration of mitochondrial function could play a role in the recovery of liver health and reversal of MASLD [

30,

31].

The improvement in fibrosis observed in ferrostatin-treated mice, as evidenced by Masson's trichrome staining, is a significant and encouraging finding of our study. This result suggests that ferroptosis inhibition may not only prevent the progression of fibrosis but also can reverse existing fibrosis in the context of MASLD. The ability to attenuate or reverse fibrosis represents a major breakthrough in the treatment of chronic liver diseases. Although these results are promising, caution should be exercised while interpreting their broader implications. Further research is necessary to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which ferroptosis inhibition affects fibrosis and to determine the extent and durability of its antifibrotic effects. Future studies should consider incorporating quantitative analysis of fibrosis markers such as hydroxyproline content and gene expression analysis of fibrosis-related genes [

32,

33]. This study possessed another limitation. It remains unclear whether ferrostatin inhibits all subsequent stages by blocking steatosis and lipogenesis or whether it directly intervenes at each individual stage. More rigorously designed studies are needed to clarify this issue. Additionally, this study can be used to determine whether ferrostatin can prevent progression to subsequent steps by only inhibiting steatosis and lipogenesis or whether it directly intervenes at each individual stage. Further research using a more robust experimental design is required to address this issue.

By integrating these experimental results, we can infer the mechanisms that lead from obesity to fatty liver disease and hepatitis (

Figure 7). Obesity induces steatosis and lipogenesis in the liver tissue, resulting in increased intracellular ROS levels. Elevated oxidative stress leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and ferritinophagy, and this decreases GPX4 activity and increases ferrous iron levels, respectively, thereby promoting lipid peroxidation and initiating ferroptosis. As ferroptosis progresses, inflammation in the liver worsens and fibrosis develops over time. Importantly, ferrostatin administration can inhibit steatosis and lipogenesis and prevent both ferritinophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, ferrostatin restored GPX4 activity, ultimately blocking the progression of ferroptosis. It can also recover preexisting inflammation and prevent the progression of fibrosis.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the dual role of ferroptosis in obesity that contributes to the development and progression of MASLD and represents a viable therapeutic target. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity-related liver diseases, targeting ferroptosis may represent a novel approach for the prevention and treatment of MASLD. Future studies should focus on elucidating the molecular pathways involved in ferroptosis within the liver and exploring the therapeutic potential of ferroptosis inhibitors in clinical settings.

Author Contributions

G.C.P. and B-.J.L. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. S-.Y.B., J.M.K., S.-C.S., and K.M.K. performed experiments and analyses. H.P., Y-.I.C., E-.S.S., M.L., and J-.C.L. provided technical support and conceptual advice. B-.J.L. supervised the project, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (no. NRF-2022R1A2C2006697).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Pusan National University Hospital (No. PNUH-2022-200).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Eunsol Cho of the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University, for graphical support in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Koliaki, C.; Dalamaga, M.; Liatis, S. Update on the Obesity Epidemic: After the Sudden Rise, Is the Upward Trajectory Beginning to Flatten? Curr Obes Rep 2023, 12, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, P.; Hellerbrand, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2014, 28, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milić, S.; Lulić, D.; Štimac, D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity: biochemical, metabolic and clinical presentations. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 9330–9337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbrini, E.; Sullivan, S.; Klein, S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 2010, 51, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Ann Hepatol 2024, 29, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divella, R.; Mazzocca, A.; Daniele, A.; Sabbà, C.; Paradiso, A. Obesity, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Adipocytokines Network in Promotion of Cancer. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V.; Bellentani, S.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Day, C.; Marchesini, G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol 2010, 53, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.K.; Chuah, K.H.; Rajaram, R.B.; Lim, L.L.; Ratnasingam, J.; Vethakkan, S.R. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J Obes Metab Syndr 2023, 32, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.L.; Ng, C.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Chan, K.E.; Tan, D.J.; Lim, W.H.; Yang, J.D.; Tan, E.; Muthiah, M.D. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023, 29, S32–s42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Ardehali, H.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023, 20, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.L.; Huang, Z.J.; Lin, Z.T.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.R.; Shah, Y.M. Iron homeostasis in the liver. Compr Physiol 2013, 3, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.; Leray, V.; Diez, M.; Serisier, S.; Le Bloc'h, J.; Siliart, B.; Dumon, H. Liver lipid metabolism. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2008, 92, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Geng, J.; Li, L.; Feng, X. An overview of ferroptosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 153, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, E.; Hu, H. Role of Ferroptosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Its Implications for Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Xue, R.; Yin, X.; Wu, M.; Meng, Q. Ferroptosis in liver disease: new insights into disease mechanisms. Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurusaki, S.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Koumura, T.; Nakasone, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Imai, H.; Yuet-Yin Kok, C.; Okochi, H.; Nakano, H.; et al. Hepatic ferroptosis plays an important role as the trigger for initiating inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Kim, J.W.; Zhou, Z.; Lim, C.W.; Kim, B. Ferroptosis Affects the Progression of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis via the Modulation of Lipid Peroxidation-Mediated Cell Death in Mice. Am J Pathol 2020, 190, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Ge, C.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The multifaceted role of ferroptosis in liver disease. Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G.; Wang, F.; Zheng, M.H. Ferroptosis and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: Is there a link? Liver Int 2022, 42, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Chu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, L. Ferroptosis in non-alcoholic liver disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1090338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochette, L.; Dogon, G.; Rigal, E.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Metabolism: Two Corner Stones in the Homeostasis Control of Ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Miao, R.; Zhong, J. Targeting Iron Metabolism and Ferroptosis as Novel Therapeutic Approaches in Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomao, M.A. Pathology of Hepatic Iron Overload. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2021, 17, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur J Pharmacol 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Chun, W.; Lee, H.J.; Min, J.H.; Kim, S.M.; Seo, J.Y.; Ahn, K.S.; Oh, S.R. The Role of Macrophages in the Development of Acute and Chronic Inflammatory Lung Diseases. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.H.; Li, D.Y.; Liang, S.; Yang, C.; Tang, J.X.; Liu, H.F. Macrophage autophagy in macrophage polarization, chronic inflammation and organ fibrosis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 946832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoral Monibas, R.; Johnson, A.M.; Osborn, O.; Traves, P.G.; Mahata, S.K. Distinct Hepatic Macrophage Populations in Lean and Obese Mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, G. Mitochondria regulation in ferroptosis. Eur J Cell Biol 2020, 99, 151058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, B. Mitochondrial regulation of ferroptosis. J Cell Biol 2021, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enomoto, H.; Bando, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Nishiguchi, S.; Koga, M. Liver fibrosis markers of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 7427–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, A.; Olson, M.C.; Samir, A.E.; Venkatesh, S.K. Liver fibrosis assessment: MR and US elastography. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022, 47, 3037–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Body weight, food intake, and serum glucose levels in C57BL/6, ob/ob, and ob/ob + FER groups over 8 weeks. (A) Body weight increased to approximately 40g in ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups, while the C57BL/6 group remained at approximately 20g (p < 0.05). (B) Serum glucose levels were consistently below 200mg/dl in C57BL/6, whereas ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups exceeded 400mg/dl (p < 0.05). (A) Food intake was significantly higher in ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups compared to that in the C57BL/6 group (p < 0.05). .

Figure 1.

Body weight, food intake, and serum glucose levels in C57BL/6, ob/ob, and ob/ob + FER groups over 8 weeks. (A) Body weight increased to approximately 40g in ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups, while the C57BL/6 group remained at approximately 20g (p < 0.05). (B) Serum glucose levels were consistently below 200mg/dl in C57BL/6, whereas ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups exceeded 400mg/dl (p < 0.05). (A) Food intake was significantly higher in ob/ob and ob/ob + FER groups compared to that in the C57BL/6 group (p < 0.05). .

Figure 2.

Lipogenesis and steatosis in the livers of C57BL/6, ob/ob, and ob/ob + FER groups. (A) C57BL/6 livers exhibited normal morphology, while the ob/ob group displayed significant steatosis by week 8. The FER group treated with ferrostatin possessed liver tissue resembling that of C57BL/6, with nearly all lipid droplets eliminated. Scale bar = 200 μm. (B) At 8 weeks, SREBP-1c, ChREBP, and ACC levels were lower in the ob/ob group but were significantly increased by 16 weeks. The ob/ob + FER group maintained levels similar to those of the C57BL/6 group, indicating that ferrostatin normalizes lipogenesis and steatosis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Lipogenesis and steatosis in the livers of C57BL/6, ob/ob, and ob/ob + FER groups. (A) C57BL/6 livers exhibited normal morphology, while the ob/ob group displayed significant steatosis by week 8. The FER group treated with ferrostatin possessed liver tissue resembling that of C57BL/6, with nearly all lipid droplets eliminated. Scale bar = 200 μm. (B) At 8 weeks, SREBP-1c, ChREBP, and ACC levels were lower in the ob/ob group but were significantly increased by 16 weeks. The ob/ob + FER group maintained levels similar to those of the C57BL/6 group, indicating that ferrostatin normalizes lipogenesis and steatosis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Oxidative stress and iron accumulation in obese mice and the efficacy of ferrostatin treatment. (A) Intracellular ROS levels in ob/ob group were similar to those in the C57BL/6 group at 8 weeks but were significantly increased by 16 weeks. The ob/ob + FER group exhibited lower ROS levels than did both C57BL/6 and ob/ob groups. MDA levels exhibited a three-fold increase at 16 weeks in the ob/ob group compared to levels in the C57BL/6 group, while the ob/ob + FER group returned to normal MDA levels. GPX4 activity decreased significantly in the ob/ob group but was preserved in the ob/ob + FER group. Ferrous iron (Fe2+) levels were significantly elevated only in the 16-week ob/ob group. (B) Prussian blue staining revealed iron accumulation (arrow) solely in the 16-week ob/ob group. (C) According to western blot analysis, NCOA4 and LC3B expression was present in the 16-week ob/ob group but was reduced in the ob/ob + FER group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Oxidative stress and iron accumulation in obese mice and the efficacy of ferrostatin treatment. (A) Intracellular ROS levels in ob/ob group were similar to those in the C57BL/6 group at 8 weeks but were significantly increased by 16 weeks. The ob/ob + FER group exhibited lower ROS levels than did both C57BL/6 and ob/ob groups. MDA levels exhibited a three-fold increase at 16 weeks in the ob/ob group compared to levels in the C57BL/6 group, while the ob/ob + FER group returned to normal MDA levels. GPX4 activity decreased significantly in the ob/ob group but was preserved in the ob/ob + FER group. Ferrous iron (Fe2+) levels were significantly elevated only in the 16-week ob/ob group. (B) Prussian blue staining revealed iron accumulation (arrow) solely in the 16-week ob/ob group. (C) According to western blot analysis, NCOA4 and LC3B expression was present in the 16-week ob/ob group but was reduced in the ob/ob + FER group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Impact of ferrostatin on liver function, inflammation, and fibrosis in obese mice. (A) Serum cholesterol, AST, and ALT levels were significantly higher in the 16-week ob/ob group compared to those in the C57BL/6 group. In contrast, levels in the ob/ob + FER group returned to baseline levels similar to those of the C57BL/6 group. (B) TGF-β staining intensity increased in the ob/ob group from 8 to 16 weeks, while it decreased in the ob/ob + FER group. (C) Collagen type I expression was higher in the ob/ob group, peaking at 16 weeks, but became normalized in the ob/ob + FER group. (D) Masson’s trichrome staining revealed no fibrosis in C57BL/6 group, weak staining in the ob/ob group at 8 weeks, and intensified staining in the ob/ob group at 16 weeks (arrow). No staining was present in the ob/ob + FER group. Scale bar = 200 μm. **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Impact of ferrostatin on liver function, inflammation, and fibrosis in obese mice. (A) Serum cholesterol, AST, and ALT levels were significantly higher in the 16-week ob/ob group compared to those in the C57BL/6 group. In contrast, levels in the ob/ob + FER group returned to baseline levels similar to those of the C57BL/6 group. (B) TGF-β staining intensity increased in the ob/ob group from 8 to 16 weeks, while it decreased in the ob/ob + FER group. (C) Collagen type I expression was higher in the ob/ob group, peaking at 16 weeks, but became normalized in the ob/ob + FER group. (D) Masson’s trichrome staining revealed no fibrosis in C57BL/6 group, weak staining in the ob/ob group at 8 weeks, and intensified staining in the ob/ob group at 16 weeks (arrow). No staining was present in the ob/ob + FER group. Scale bar = 200 μm. **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Macrophage polarization changes in response to ferrostatin treatment. Analysis of mRNA expression revealed significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (A) in 16-week ob/ob mice compared to those in the other groups, while levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (B) were similar to those in the control group. Ferrostatin treatment in ob/ob mice inhibits M1 cytokines and increases M2 cytokines, promoting a shift from M1 to M2 macrophages. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Macrophage polarization changes in response to ferrostatin treatment. Analysis of mRNA expression revealed significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (A) in 16-week ob/ob mice compared to those in the other groups, while levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (B) were similar to those in the control group. Ferrostatin treatment in ob/ob mice inhibits M1 cytokines and increases M2 cytokines, promoting a shift from M1 to M2 macrophages. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 6.

Restoration of mitochondrial structure and function by ferrostatin in obese mice. (A) Electron microscopy revealed that mitochondria in 16-week ob/ob group displayed increased membrane density, loss of cristae, and contraction compared to these characteristics in the C57BL/6 group. In contrast, the ob/ob + FER group exhibited normalized mitochondrial morphology, with cristae levels comparable to those of the C57BL/6 group. M, mitochondria; LD, lipid droplet. (B) The activities of GSH and SOD significantly decreased in 16-week ob/ob group but were restored to normal levels in the ob/ob + FER group. ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 6.

Restoration of mitochondrial structure and function by ferrostatin in obese mice. (A) Electron microscopy revealed that mitochondria in 16-week ob/ob group displayed increased membrane density, loss of cristae, and contraction compared to these characteristics in the C57BL/6 group. In contrast, the ob/ob + FER group exhibited normalized mitochondrial morphology, with cristae levels comparable to those of the C57BL/6 group. M, mitochondria; LD, lipid droplet. (B) The activities of GSH and SOD significantly decreased in 16-week ob/ob group but were restored to normal levels in the ob/ob + FER group. ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 7.

Mechanisms linking obesity to fatty liver and hepatitis mediated by ferroptosis. Obesity induces hepatic steatosis and lipogenesis, leading to increased intracellular ROS levels. Elevated oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and ferritinophagy that decrease GPX4 activity and increase intracellular ferrous iron levels. This signaling cascade promotes lipid peroxidation and initiates ferroptosis. As ferroptosis progresses, liver inflammation worsens, resulting in fibrosis. Importantly, ferrostatin treatment inhibited steatosis and lipogenesis, prevented ferritinophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction, and restored GPX4 activity, ultimately blocking the progression to ferroptosis. Additionally, ferrostatin aids in the recovery of pre-existing inflammation and prevents further development of fibrosis.

Figure 7.

Mechanisms linking obesity to fatty liver and hepatitis mediated by ferroptosis. Obesity induces hepatic steatosis and lipogenesis, leading to increased intracellular ROS levels. Elevated oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and ferritinophagy that decrease GPX4 activity and increase intracellular ferrous iron levels. This signaling cascade promotes lipid peroxidation and initiates ferroptosis. As ferroptosis progresses, liver inflammation worsens, resulting in fibrosis. Importantly, ferrostatin treatment inhibited steatosis and lipogenesis, prevented ferritinophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction, and restored GPX4 activity, ultimately blocking the progression to ferroptosis. Additionally, ferrostatin aids in the recovery of pre-existing inflammation and prevents further development of fibrosis.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers.

| Gene |

Sequence (5‘-3‘) |

| Forward |

Reverse |

| GAPDH |

AGCCCAAGATGCCCTTCAGT |

CCGTGTTCCTACCCCCAATG |

| SREBP-1c |

ACGGAGCCATGGATTGCACA |

AAGGGTGCAGGTGTCACCTT |

| ChREBP |

CTGGGGACCTAAACAGGAGC |

GAAGCCACCCTATAGCTCCC |

| ACC |

ATGGGCGGAATGGTCTCTTTC |

TGGGGACCTTGTCTTCATCAT |

| TGF-β1 |

GTGTGGAGCAACATGTGGAACTCTA |

TTGGTTCAGCCACTGCCGTA |

| Col1 |

CCTCAGGGTATTGCTGGACAAC |

CAGAAGGACCTTGTTTGCCAGG |

| TNF-α |

GGTGCCTATGTCTCAGCCTCTT |

GCCATAGAACTGATGAGAGGGAG |

| IL-4 |

GGTCACAGGAGAAGGGACGCC |

TGCGAAGCACCTTGGAAGCCC |

| Fizz1 |

CTG CCC TGC TGG GAT GAC T |

CAT CAT ATC AAA GCT GGG TTC TCC |

| Arg-1 |

GGA ATC TGC ATG GGC AAC CTG TGT |

AGG GTC TAC GTC TCG CAA GCC A |

| CD11b |

CCA CAG TTC ACA CTT CTT TCA G |

TGT CCA GAT TGA AGC CAT GA |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).