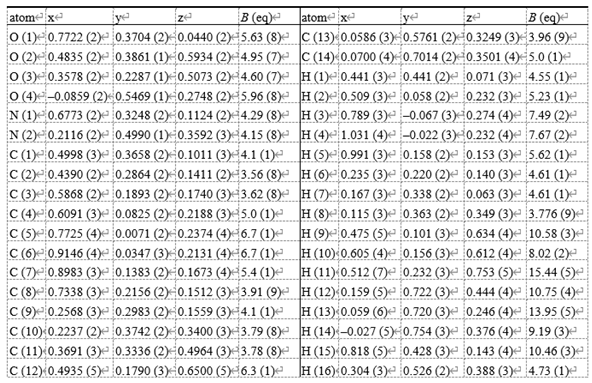

Melting points were determined on a Yanagimoto micro melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Infrared (IR) spectra with a Shimadzu IR-420, a Shimadzu IR-460, and a Horiba FT-720 spectrophotometers, UV spectra with a Shimadzu UV 2400 PC spectrophotometer, and 1H-NMR spectra with JEOL FX-100, JEOL EX 270, and JEOL GSX 500 spectrometers, with tetramethyl silane as an internal standard. Mass spectra (MS) were recorded on a Hitachi M-80 or JEOL SX-102A spectrometer. Preparative thin-layer chromatography (p-TLC) was performed on Merck Kiesel-gel GF254 (Type 60) (SiO2) or Merck Aluminum Oxide GF254 (Type 60/E) (Al2O3). Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (SiO2, 100—200 mesh, from Kanto Chemical Co. Inc.) or activated alumina (Al2O3, 300 meshes, from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.) throughout the present study.

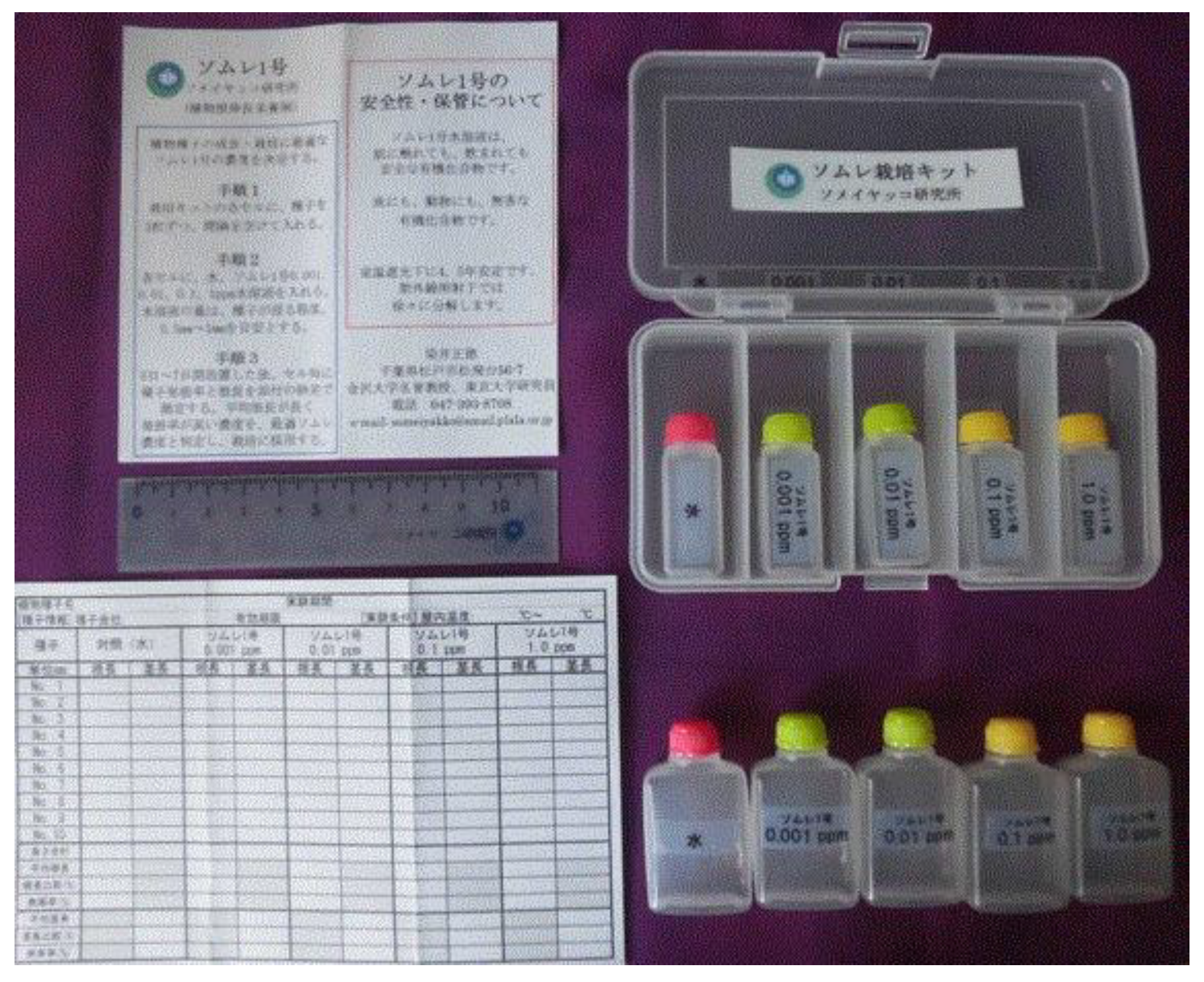

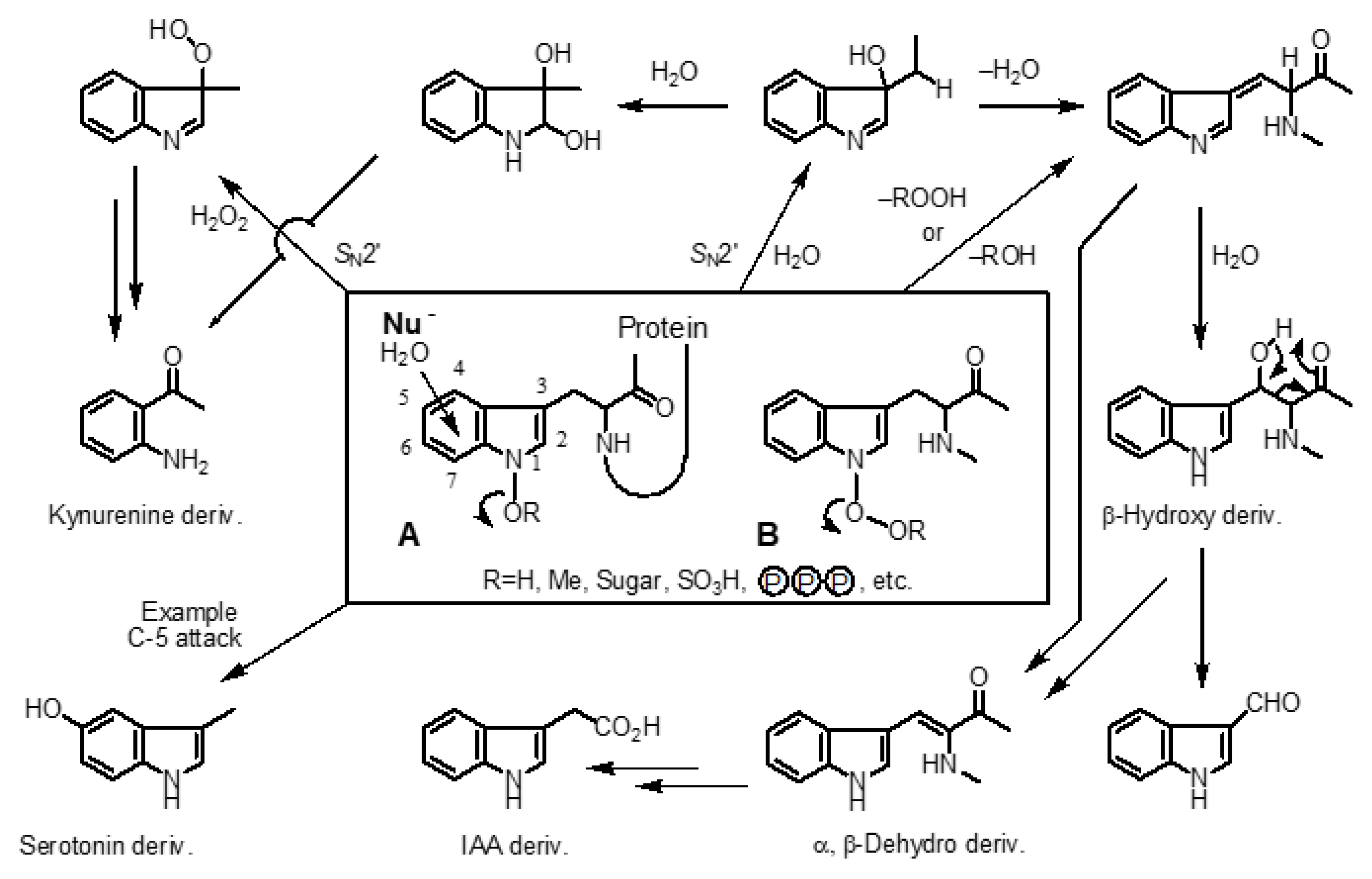

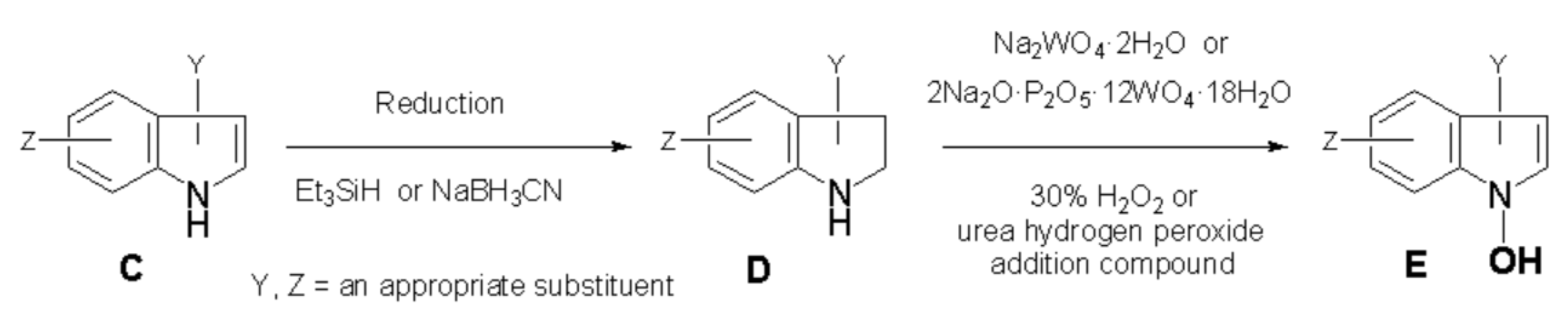

23.1. Synthesis of SOMRE and Related Derivatives Based on the 1-Hydroxyindole Chemistry

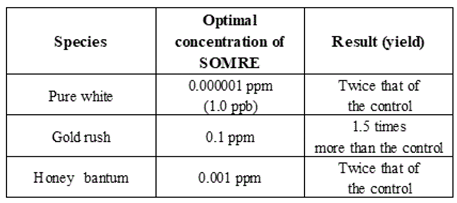

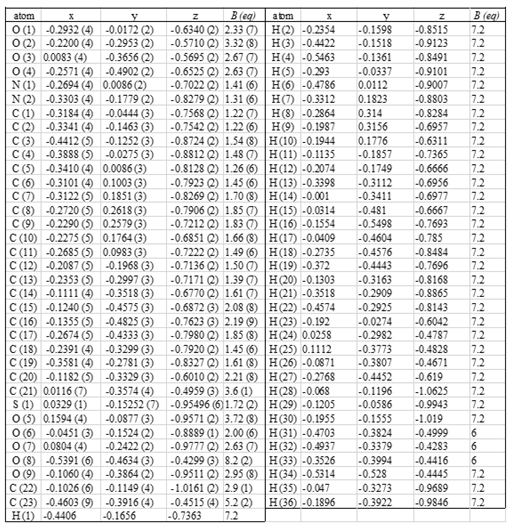

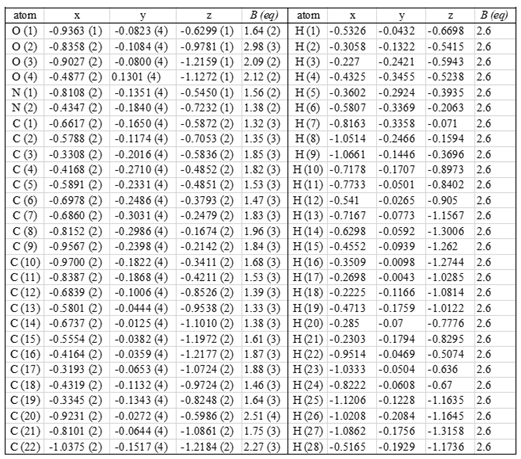

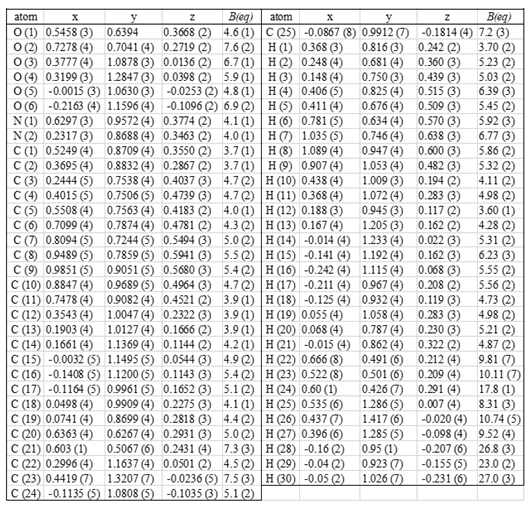

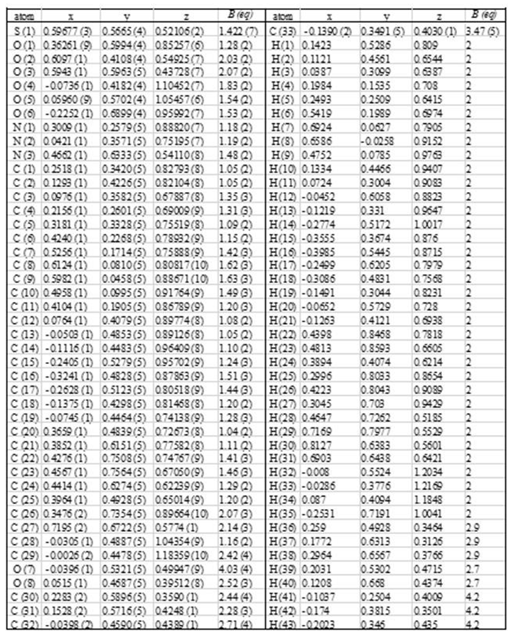

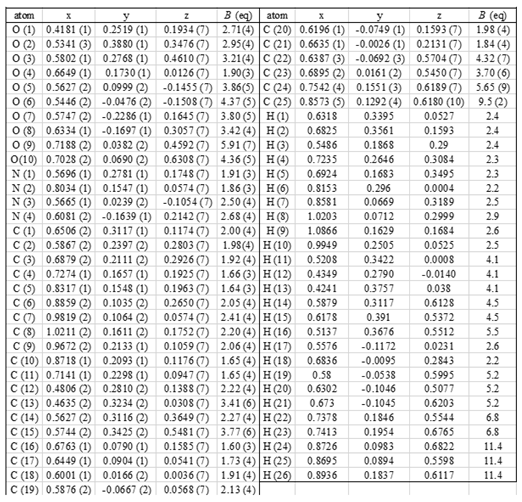

Table 30.

Preparation of 1-methxyindole (6) from 2,3-dihydroindole (3)[54]..

Table 30.

Preparation of 1-methxyindole (6) from 2,3-dihydroindole (3)[54]..

1-Methoxyindole (6) from 2,3-dihydroindole (3)[

54] —

General method A (Table 30, Entry 1) :

A solution of Na

2WO

4·2H

2O[

70] (2.834 g, 8.42 mmol) in H

2O (40.0 mL) was added to a solution of

3 (5.015 g, 42.1 mmol) in MeOH (375 mL). 30% H

2O

2 (47.657 g, 421 mmol) was added to the resultant solution at 0 °C with stirring. After stirring for 15 min at rt (16 °C), K

2CO

3 (20.456 g, 147 mmol) and a solution of Me

2SO

4 (7.972 g, 631 mmol) in MeOH (25.0 mL) were added to the reaction mixture. After stirring for 90 min at rt (16 °C), brine (330 mL) was added and the whole was extracted with CHCl

3 (200 mL x 3). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a black oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with CHCl

3–hexane (1:4, v/v) to give

6 (3.361 g, 15%). [

12,

61]

6: colorless oil. Mass and all spectral data are identical with those reported by Acheson et al.[

62]

General method B (Table 1, Entry 3): A solution of Na2WO4·2H2O (13.2 mg, 0.04 mmol) in H2O (0.5 mL) was added to a solution of 3 (47.5 mg, 0.39 mmol) in MeOH (4.0 mL). 30% H2O2 (452.5 mg, 4.0 mmol) was added to the resultant solution at 0 °C with stirring. After stirring for 30 min at rt (17 °C), ethereal CH2N2 (excess) was added to the reaction mixture with stirring at rt until the starting material was not detected on tlc monitoring. Brine was added and the whole was extracted with CH2Cl2. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave oil, which was purified by p-TLC on SiO2 with CH2Cl2–hexane (7:3, v/v) as a developing solvent. Extraction of a band having an Rf value of 0.92–0.79 with CH2Cl2 afforded 6 (29.6 mg, 50%).

Entry 6: In the same procedure for Entry 3, Na2WO4·2H2O (27.0 mg, 0.08 mmol), 3 (48.8 mg, 0.41 mmol), 30% H2O2 (464.9 mg, 4.10 mmol) were used. And the same work-up as Entry 3 afforded 6 (31.1 mg, 52%).

Entry 12: In the same procedure for Entry 3, 2Na2O·P2O5·12WO4·18H2O (23.8 mg, 0.007 mmol), 3 (50.3 mg, 0.42 mmol), 30% H2O2 (479.2 mg, 4.22 mmol) were used. And the same work-up as Entry 3 afforded 6 (35.9 mg, 58%).

General method C (Table 1, Entry 13): A solution of Na2WO4·2H2O (591.4 mg, 1.79 mmol) in H2O (10.0 mL) and urea·H2O2 compound (8.437 g, 89.64 mmol) were added to a solution of 3 (1.068 g, 8.96 mmol) in MeOH (100.0 mL) at 0 °C with stirring. After stirring at rt for 15 min, K2CO3 (22.300 g, 161.3 mmol) and then a solution of Me2SO4 (3.391 g, 26.9 mmol) in MeOH (10.0 mL) were added to the reaction mixture. After the same work-up as Entry 3, 6 (717.5 mg, 54%) was obtained.

Entry 14: m-Chloroperbenzoic acid (231.6 mg, 0.94 mmol), (n-Bu)4NHSO4 (7.1 mg, 0.02 mmol) and sat. aq. NaHCO3 (5.0 mL) were added to a solution of 3 (111.4 mg, 0.94 mmol) in acetone–CH2Cl2 (1:1, v/v, 5.0 mL) at 0 °C with stirring. After stirring for 5 min, brine was added. The whole was extracted with CH2Cl2 and ethereal CH2N2 (excess) was added to the extract. After stirring for 3 min, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to leave oil, which was purified by column-chromatography on SiO2 to afford 6 (47.5 mg, 35%).

Entry 15: In the same procedure as Entry 14, solvent was changed to CH2Cl2 (5.0 mL) only, where m-chloroperbenzoic acid (223.2 mg, 0.90 mmol), (n-Bu)4NHSO4 (7.2 mg, 0.02 mmol), 3 (107.0 mg, 0.90 mmol), and sat. aq. NaHCO3 (5.0 mL) were used. After usual work-up, 6 (52.9 mg, 40%) was obtained.

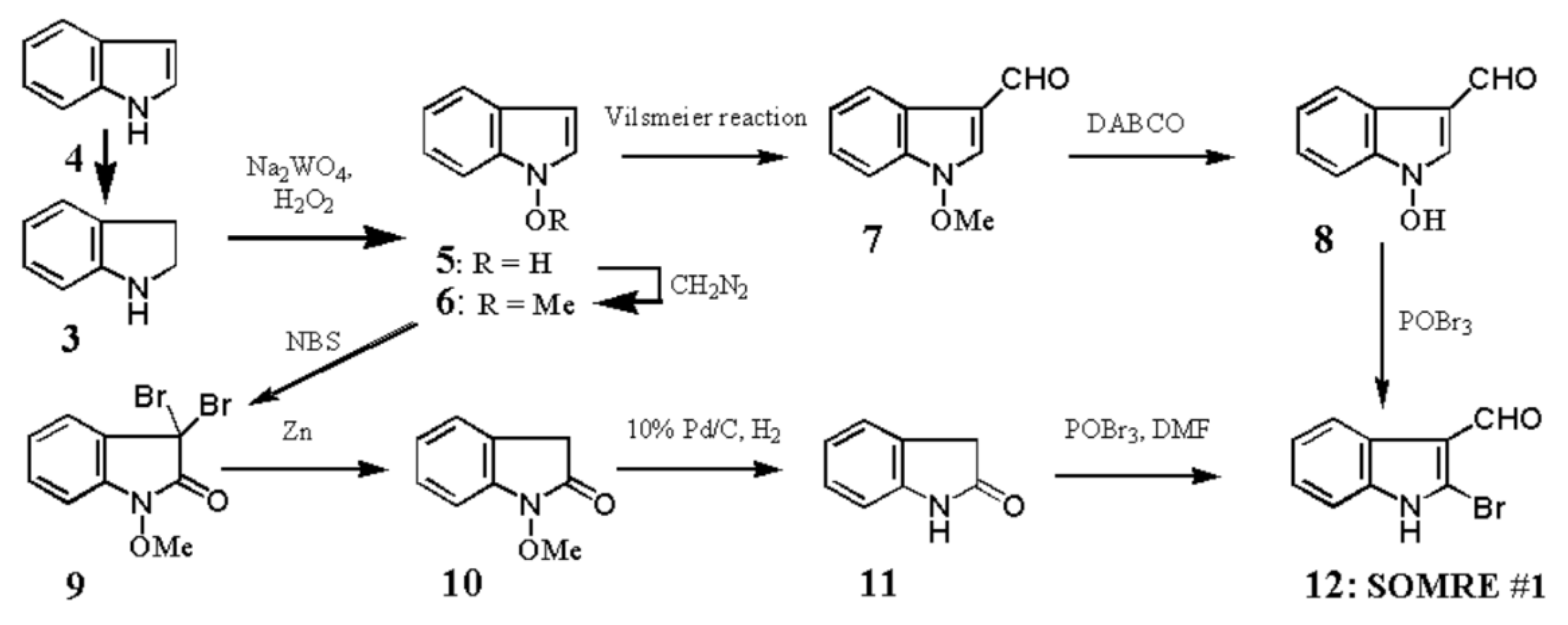

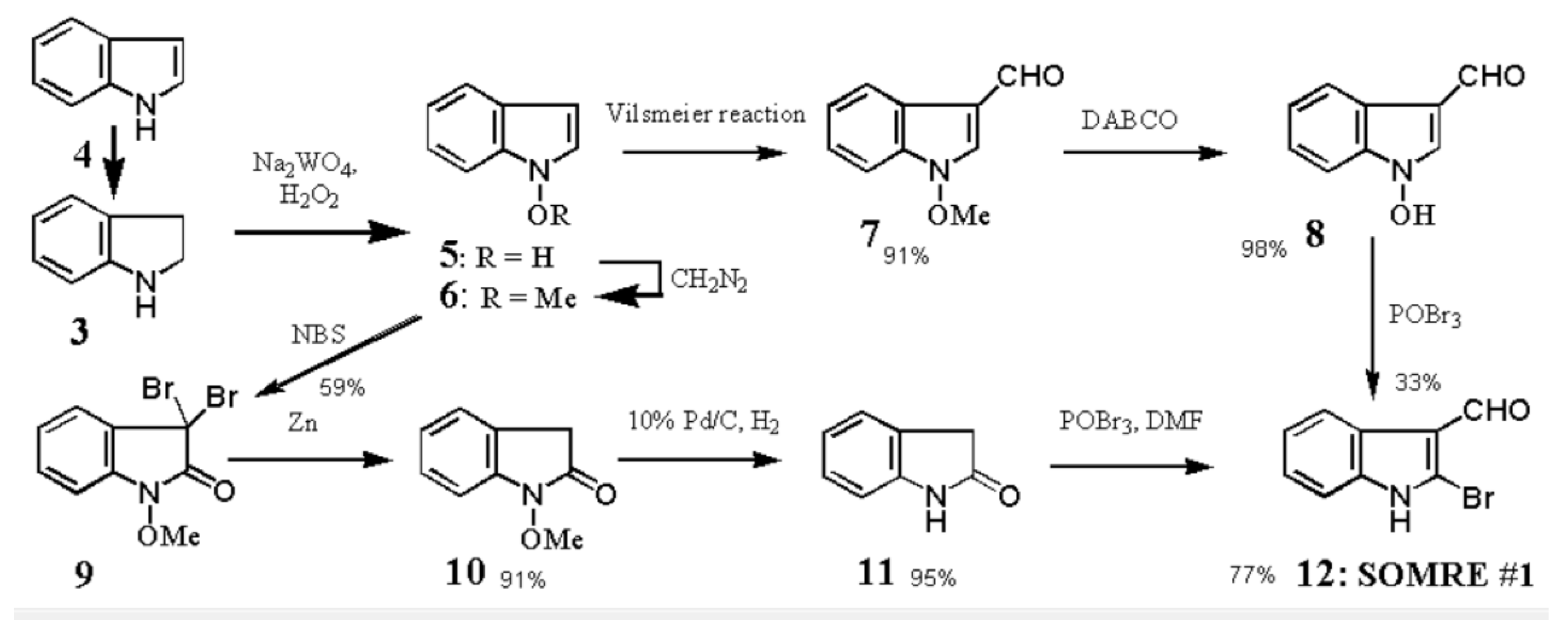

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of SOMRE #1 (12).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of SOMRE #1 (12).

1-Methoxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (7)[63] from 1-methoxyindole (6) — POCl

3 (8.4mL) was added to an ice cooled anhydrous DMF (31.0 mL) with stirring. A solution of

6 (12.341 g) in anhydrous DMF (10.0 mL) was added to the resultant viscous solution and stirring was continued at rt for 2 h. Then, crushed ice and 16% aq. NaOH (100 mL) were added to the reaction mixture and the whole was extracted with ether. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to give a crystalline solid. Recrystallization from ether-hexane afforded

7 (13.411 g, 91.3%) as colorless prisms.

7: mp 50.0–51.0 °C. IR (KBr): 2810,1660–1650, 1375, 1240 cm

-1.

1H-NMR (CCl

4) δ: 3.98 (3H, s), 6.81–7.31(3H, m, 7.52 (1H, s), 7.80–8.16 (1H,m), 9.57 (1H, s). MS

m/z: 175 (M

+):

Anal. Calcd. for C

10H

9NO

2·1/2H

2O: C, 66.84; H, 5.33; N, 7.80. Found: C, 67.04; H, 5.11; N, 7.89.

3,3-Dibromo-1-methoxy-2-oxindole (9) from 1-methoxyindole (6) — NBS (3.637 g, 20.43 mmol) was added to a solution of 6 (1.001g, 6.81 mmol) in t-BuOH (70 mL) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 30 min. After evaporation of the solvent, H2O was added to the residue. The whole was extracted with benzene. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a yellow solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CH2Cl2–hexane (2:1, v/v) to give 9 (1.281 g, 59%). 9: mp 73—75°C (pale yellow prisms, recrystallized from CH2Cl2–hexane). IR (KBr): 1745 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.06 (3H, s), 6.95 (1H, dd, J=7.7, 1.5 Hz), 7.15 (1H, br dt, J=1.5, 7.7 Hz), 7.34 (1H, br dt, J=1.5, 7.7 Hz), 7.56 (1H, dd, J=7.8, 1.5 Hz). MS m/z: 319, 321, and 323 (M+, 79Br and 81Br). Anal. Calcd for C9H7Br2NO2: C, 33.64; H, 2.18; N, 4.36. Found: C, 33.51; H, 2.09; N, 4.51.

1-Methoxy-2-oxindole (

10) from 9 — Zink powder (103.2 mg, 1.6 mmol) was added to a solution of

9 (50.5 mg, 0.16 mmol) in AcOH (5 mL) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. Unreacted Zn was filtered off and washed with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). H

2O was added to the combined washing and the filtrate. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with CH

2Cl

2 to give

10 (16.6 mg, 65%). Spectral data are identical with the authentic sample prepared according to our previous procedures.[

73]

2-Oxindole (11) from 10 — A solution of 10 (155.3 mg, 0.95 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was hydrogenated in the presence of 10% Pd/C (50 mg) at rt and 1 atm for 1 h. Catalyst was filtered off and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a crystalline solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CH2Cl2 to give 11 (120.4 mg, 95%), whose physical data were identical with the commercially available sample.

1-Hydroxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (8) from 1-Methoxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (7) — i) Method A:

DABCO (386.3 mg, 3.45 mmol) was added to a solution of

7[3,17] (61.2 mg, 0.35 mmol) in DMF–H

2O (3:1, v/v, 2 mL) and the mixture was heated at 100°C for 21 h with stirring. After addition of H

2O, the whole was made acidic (pH 4) with 6% HCl and extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a brown solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with CHCl

3–MeOH (97:3, v/v) to give

8 (55.0 mg, 98%).

8: mp 154—156 °C (decomp, pale yellow prisms, recrystallized from AcOEt-hexane). IR (KBr): 3107, 1616 (br), 1558 (br), 1516, 1309, 1238 cm

-1.

1H-NMR (DMSO-

d6) δ: 7.26 (1H, dt,

J=1.3, 7.3 Hz), 7.34 (1H, dt,

J=1.3, 7.3 Hz), 7.52 (1H, d,

J=7.3 Hz), 8.11 (1H, d,

J=7.3 Hz), 8.43 (1H, s), 9.84 (1H, s), 12.20 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D

2O).

Anal. Calcd for C

9H

7NO

2: C, 67.07; H, 4.38; N, 8.69. Found: C, 66.86; H, 4.37; N, 8.66.

ii) Method B: KI (2.753 g, 16.6 mmol) was added to a solution of 7 (32.3 mg, 0.19 mmol) in DMF–H2O (3:1, v/v, 4 mL) and the mixture was heated at 160°C for 24 h with stirring. After the same work-up as described in the method B, unreacted 7 (10.5 mg, 33%), 8 (0.7 mg, 3%), and 8 (16.3 mg, 55%) were obtained in the order of elution.

SOMRE #1 (2-Bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (12) from 2-Oxindole (11) — A solution of phosphorus tribromide (8.0 ml, 78.7 mmol) in anhydrous CHCl

3 (20 mL) was added dropwise to anhydrous DMF (30 mL) at 0 °C within 10 min with stirring. The mixture became viscous and then turned to yellow white solid. Although magnetic stirring bar stopped stirring, a solution of 2-oxindole (

11, 4.056 g, 30.5 mmol) in anhydrous CHCl

3 (60 mL) was added to the yellow white solid and the whole was immersed in an ultra sound bath for 1 h at rt and allowed to stand for 10 h. Again, the whole was immersed in an ultra sound bath for 1 h at rt. With ice cooling, H

2O (100 mL) was added to the reaction mixture and the yellow solid solved. The whole was then made slightly alkaline (pH 9) with 40% aqueous NaOH. After separation of organic layer, the water layer was extracted with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (9:1, v/v, 4 times, total 400 mL). The combined organic layer and the extract was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave crystals. Repeated recrystallization from MeOH afforded

12. Total yield : 5.281 g (77%).

12: mp 209.0–210.5°C[1b] (colorless needles, , recrystallized from MeOH, lit.[

67] mp 196—198°C). IR (KBr): 3100, 1645 cm

-1.

1H-NMR (DMSO-

d6) δ: 6.96–7.54 (3H, m), 7.88–-8.14 (1H, m), 9.82 (1H, s). MS

m/z: 223 and 225 (M

+,

79Br and

81Br).

Anal. Calcd for C

9H

6BrNO: C, 48.25; H,2.70; N, 6.25. Found: C, 48.26; H, 2.70; N, 6.35.

SOMRE #1 (2-Bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (12) from 1-Hydroxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (8) — A solution of 8 (27.6 mg, 0.17 mmol) in anhydrous THF (3 mL) was added to POBr3 (310.0 mg, 1.08 mmol) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 15 h. After addition of H2O, the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give 12 (12.6 mg, 33%) and 24 (5.3 mg, 21%) in the order of elution.

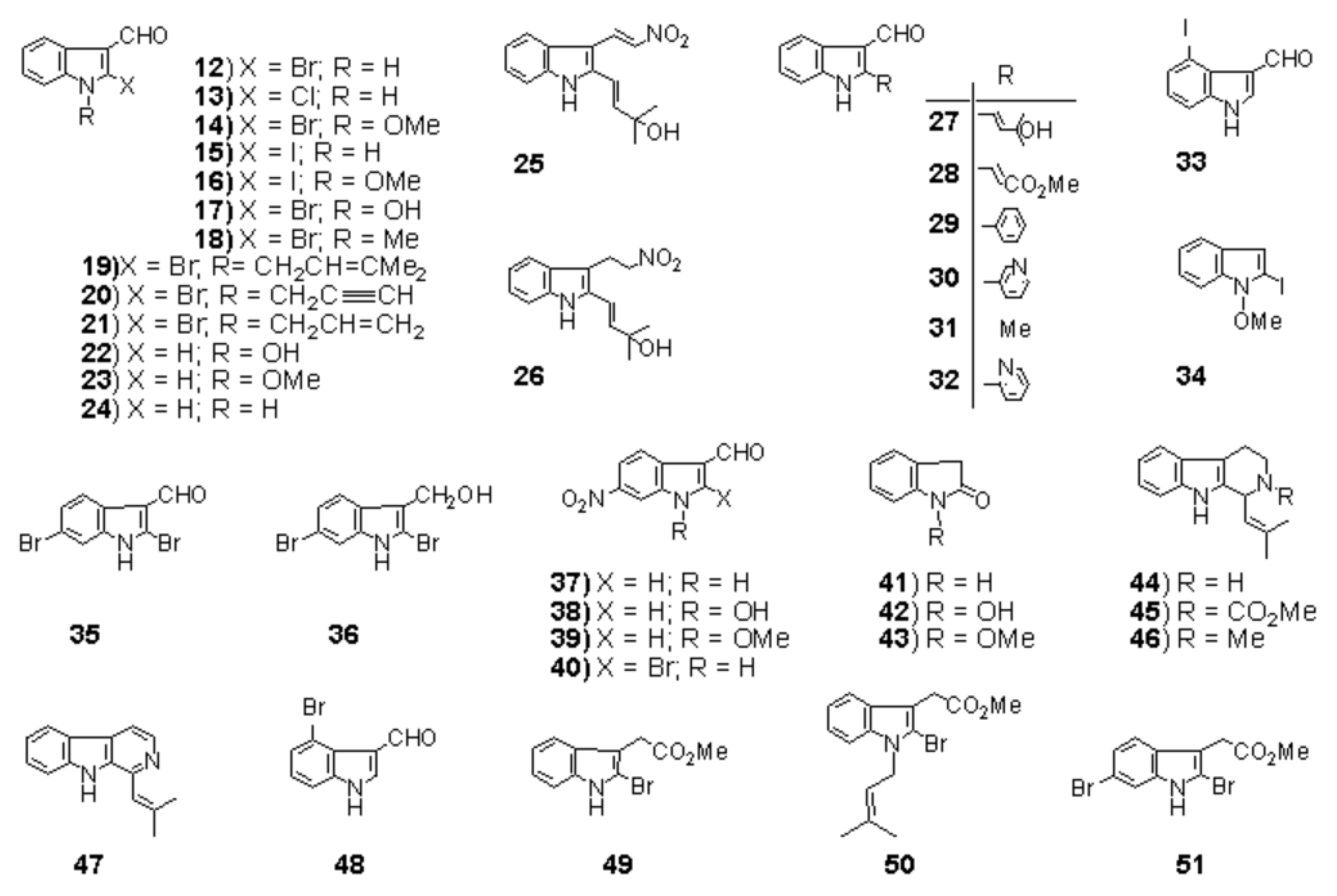

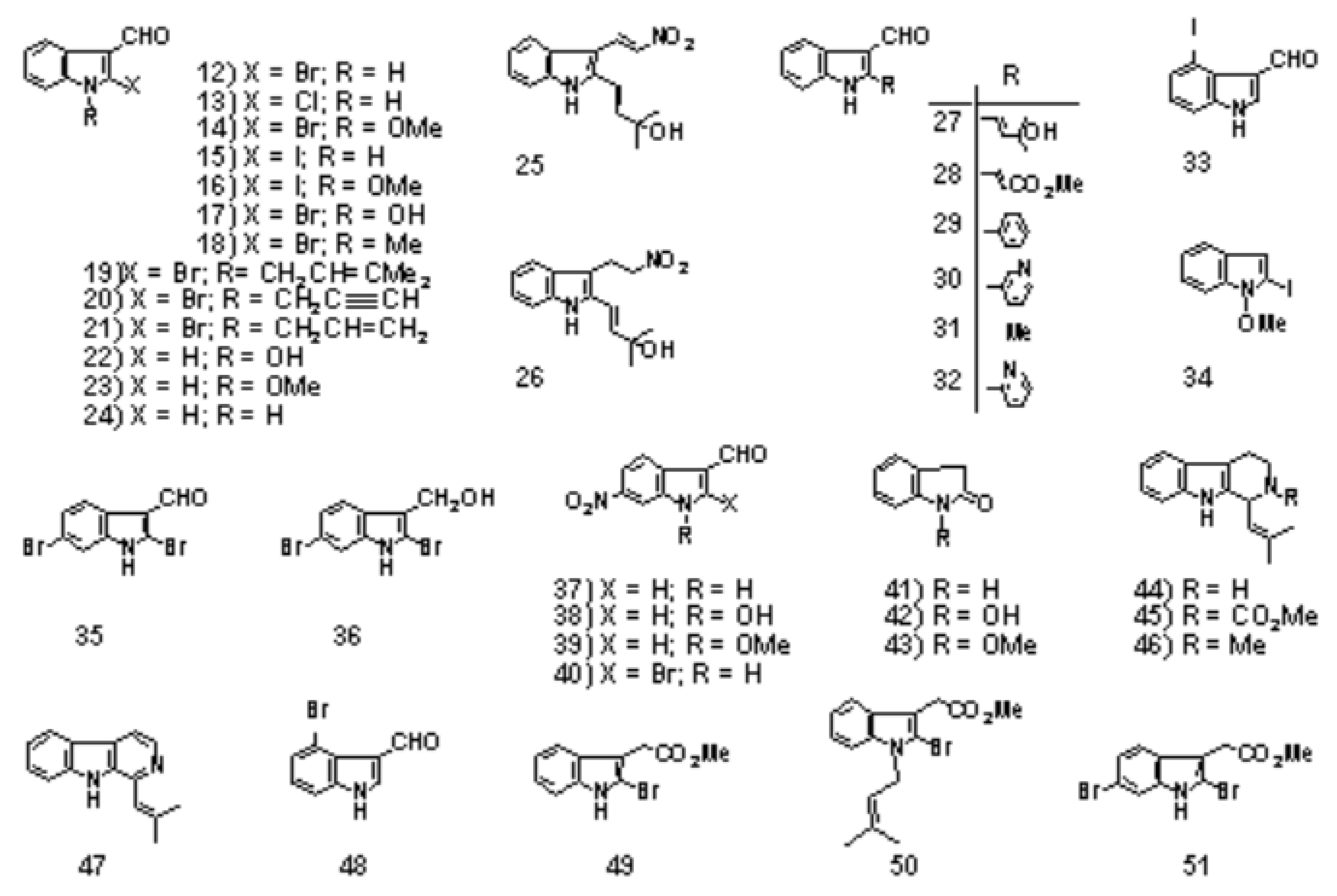

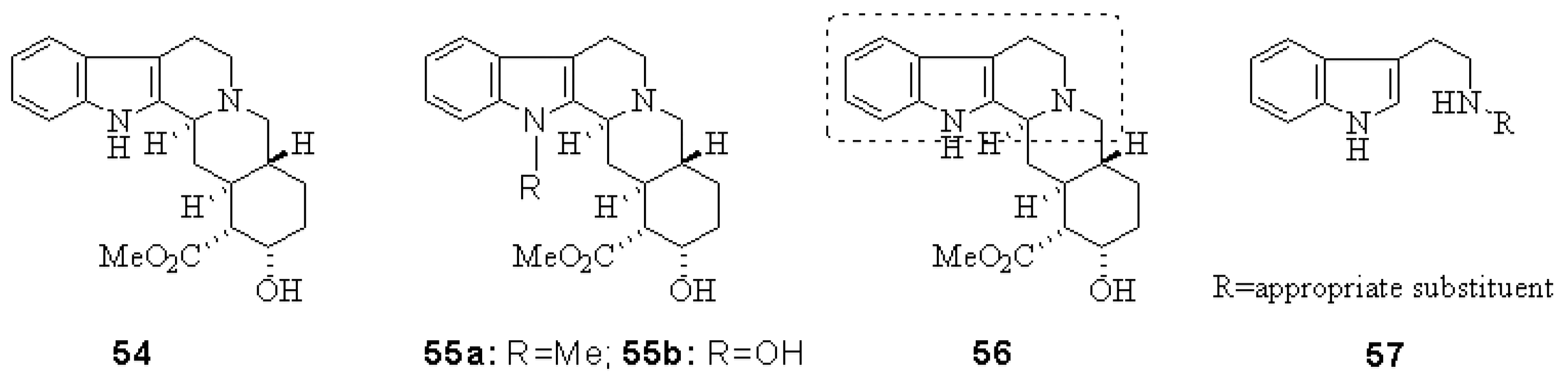

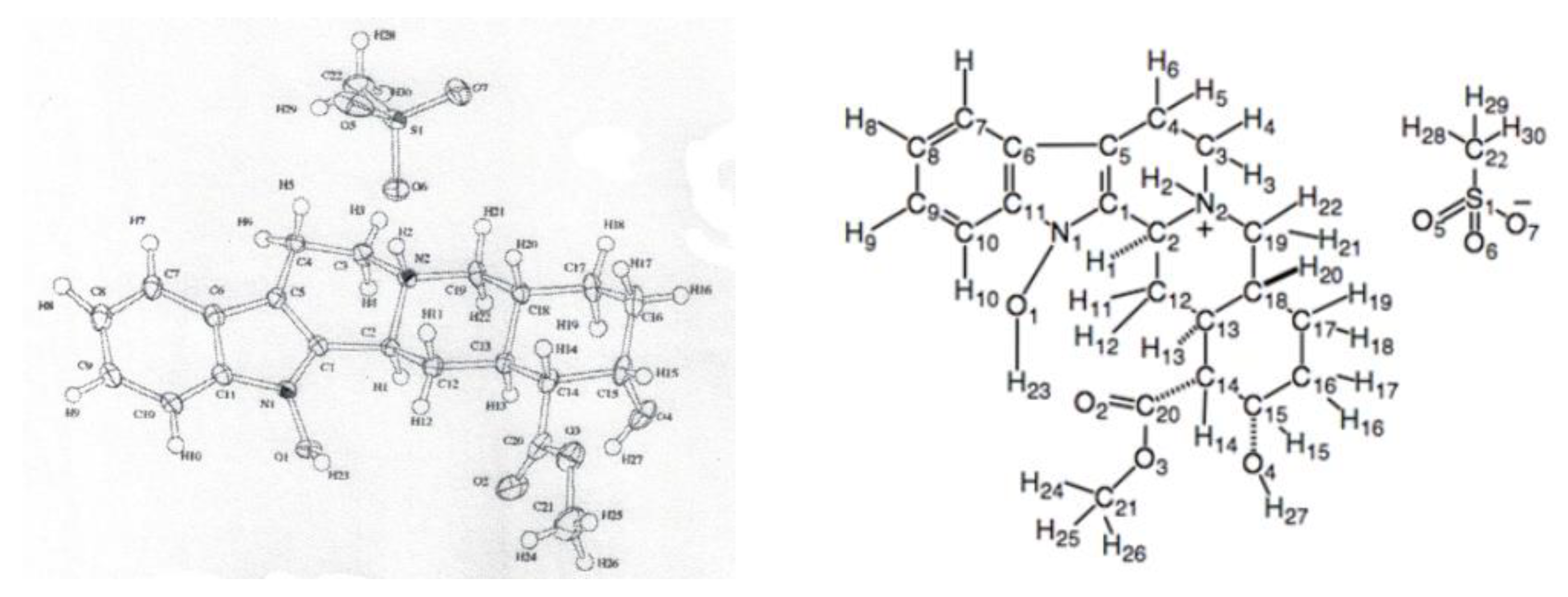

Figure 3.

SOMRE family compounds 12-51.

Figure 3.

SOMRE family compounds 12-51.

2-Chloroindole-3-carbaldehyde (13) from (8) — A solution of

8 (27.6 mg, 0.17 mmol) in anhydrous THF (3 mL) was added to POCl

3 (45.9 mg, 0.3 mmol) and DMF (22.0 mg, 0.3 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 5.5 h. The whole was made basic with 8% aqueous NaOH and extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with CH

2Cl

2 to give

13 (20.6 mg, 67%). Physical data were identical with those of the authentic sample.[

68]

2-Bromo-1-methoxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (14) from 1-Methoxy-2-oxindole (10)[

69] — Anhydrous DMF (9 mL) was added to a solution of POBr

3 (0.2 mL) in anhydrous CHCl

3 (6 mL) at 0°C and stirring was continued at rt for 15 min. To the resulting solution was added a solution of

10[70] (236.3 mg, 1.45 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) at 0°C and the mixture was stirred at rt for 12 h. The whole was made basic with 8% aqueous NaOH and extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:3, v/v) to give

14 (307.5 mg, 84%).

14: mp 97—98°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 1653 cm

-1.

1H NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 4.19 (3H, s), 7.31 (1H, ddd,

J=7.6, 7.3, 1.2 Hz), 7.36 (1H, ddd,

J=7.8, 7.3, 1.2 Hz), 7.45 (1H, dd,

J=7.8, 1.2 Hz), 8.32 (1H, dd,

J=7.6, 1.2 Hz), 9.98 (1H, s). MS m/z: 253 and 255 (M

+,

79Br and

81Br).

Anal. Calcd for C

10H

8BrNO: C, 47.27; H, 3.17; N, 5.51. Found: C, 47.02; H, 3.22; N, 5.33.

2-Iodoindole-3-carbaldehyde (15) from 12 — KI (1.144 g, 6.89 mmol) and CuI (659.5 mg, 3.46 mmol) were added to a solution of 12 (152.8 mg, 0.68 mmol) in DMF (15 mL) and the mixture was heated at 120°C for 48 h. After evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure, H2O was added to the residue. The whole was extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give an inseparable mixture (151.9 mg) of 12 and 15 in a ratio of 1:3.1 (1H-NMR analysis). The yields of 12 and 15 were calculated to be 29.8 mg (20%) and 122.1 mg (62%), respectively. To obtain 2 mg of pure 15, repeated HPLC and column-chromatography were required. 15: mp 224—226°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3138, 1639 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 7.19 (1H, td, J=7.5, 1.2 Hz), 7.22 (1H, td, J=7.5, 1.2 Hz), 7.42 (1H, dd, J=7.5, 1.2 Hz), 8.09 (1H, dd, J=7.5, 1.2 Hz), 9.72 (1H, s), 12.81 (1H, br s). High-resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C9H6INO: 270.9494. Found: 270.9478.

2-Iodo-1-methoxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (16) from 2-Iodo-1-methoxyindole (34) — POCl3 (0.2 mL, 2.15 mmol) was added to DMF (2 mL, 25.8 mmol) at 0°C and the stirring was continued at rt for 15 min. To the solution was added a solution of 34 (137.1 mg, 0.50 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) at 0°C and the mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h. The whole was made basic with 8% aqueous NaOH and extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under the reduced pressure to leave a solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:5, v/v) to give 16 (105.6 mg, 70%). 16: mp 132—134°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 1645 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.18 (3H, s), 7.29 (1H, t, J=7.3 Hz), 7.33 (1H, t, J=7.3 Hz), 7.46 (1H, d, J=7.3 Hz), 8.33 (1H, d, J=7.3 Hz), 9.79 (1H, s). MS m/z: 301 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C10H8INO2: C, 39.89; H, 2.68; N, 4.65. Found: C, 40.33; H, 2.87; 4.47.

2,6-Dibromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (35) with/without 2-Bromo-1-hydroxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (17) from 2-Bromo-1-methoxyindole-3-carbaldehyde (14) — i) Method A: BBr3 (2 mL, 21.2 mmol) was added to a solution of 14 (50.0 mg, 0.20 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) at 0°C and the mixture was refluxed for 21 h with stirring. The mixture was poured into an ice water and the whole was extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v) to give 35 (36.3 mg, 61%). 35: mp 269—270°C (decomp., colorless prisms, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3082, 1631 cm-1. 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ: 7.35 (1H, dd, J=8.5, 1.8 Hz), 7.56 (1H, d, J=1.8 Hz), 8.04 (1H, d, J=8.5 Hz), 9.91 (1H, s). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.41 (1H, dd, J=8.5, 1.2 Hz), 7.51 (1H, d, J=1.2 Hz), 8.17 (1H, d, J=8.5 Hz), 8.76 (1H, br s), 10.01 (1H, s). MS m/z: 301, 303, and 305 (M+ 79Br2, 79Br81Br, and 81Br2). Anal. Calcd for C9H5Br2NO: C, 35.68; H, 1.66; N, 4.62. Found: C, 35.64; H, 1.72; N, 4.57.

ii) Method B: BBr3 (4.0 mL, 42.3 mmol) was added to a solution of 14 (97.0 mg, 0.33 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (10 mL) at 0°C and the mixture was stirred at rt for 24 h. After the same work-up as described in the Method A, the crude product was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3 to give unreacted 14 (30.8 mg, 32%), 35 (18.2 mg, 16%), and 17 (12.7 mg, 14%) in the order of elution. 17: mp 192—194°C (decomp., colorless needles, recrystallized from AcOEt–hexane). IR (KBr): 1630 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CD3OD) δ: 7.27 (1H, dd, J=7.8, 7.3 Hz), 7.34 (1H, J=7.8, 7.3 Hz), 7.50 (1H, d, J=7.8 Hz), 8.16 (1H, d, J=7.8 Hz), 9.86 (1H, s). High-resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C9H679BrNO2: 238.9582. Found: 238.9579. Calcd for C9H681BrNO2: 240.9561. Found: 240.9556.

2-Bromo-1-methylindole-3-carbaldehyde (18) from 12 — A solution of MeI (969.2 mg, 6.83 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added to a mixture of 12 (1.07 g, 4.75 mmol), Bu4NBr (306.9 mg, 0.952 mmol), and K2CO3 (3.55 g, 25.7 mmol) in THF (60 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 5 h. After addition of brine, the whole was extracted with CH2Cl2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CH2Cl2 to give 18 (1.11 g, 98%). 18: mp 118—118.5°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from hexane). IR (KBr): 1638 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 3.84 (3H, s), 7.14—7.36 (3H, m), 8.14—8.36 (1H, m), 9.98 (1H, s). MS m/z: 237 and 239 (M+, 79Br and 81Br). Anal. Calcd for C10H8BrNO: C, 50.45; H, 3.39; N, 5.88. Found: C, 50.44; H, 3.35; N, 6.09.

2-Bromo-1-(3-methyl-2-buten-1-yl)indole-3-carbaldehyde (19) from 12 — A solution of prenyl bromide (1.06 g, 7.17 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added to a mixture of 12 (1.02 g, 4.54 mmol), Bu4NBr (300.8 mg, 0.933 mmol), and K2CO3 (3.57 g, 25.8 mmol) in THF (60 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 6 h. After the same work-up as described in the preparation of 18, 1.22 g (92%) of 19 was obtained. 19: 78.5—79°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from hexane). IR (KBr): 1650 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.75 (3H, d, J=1.2 Hz), 1.92 (3H, d, J=1.2 Hz), 4.83 (2H, d, J=7.0 Hz), 5.18 (1H, th, J=7.0, 1.2 Hz), 7.11—7.35 (3H, m), 8.15—8.39 (1H, m). 10.00 (1H, s). MS m/z: 291 and 293 (M+, 79Br and 81Br). Anal. Calcd for C14H14BrNO: C, 57.55; H, 4.83; N, 4.79. Found: C, 57.58; H, 4.84; N, 4.80.

2-Bromo-1-propargylindole-3-carbaldehyde (20) from 12 — A solution of propargyl bromide (826.6 mg, 6.95 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added to a mixture of 12 (1.00 g, 4.50 mmol), Bu4NBr (280.1 mg, 0.88 mmol), and K2CO3 (3.19 g, 23.1 mmol) in THF (40 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 22 h. After addition of brine, the whole was extracted with CH2Cl2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a crystalline solid, which was recrystallized from MeOH to give 20 (1.01 g) as colorless flakes. The mother liquor was subjected to p-TLC on SiO2 with CH2Cl2–hexane (3:2, v/v) as a developing solvent. Extraction of the band having an Rf value of 0.35—0.43 with CH2Cl2–MeOH (95:5, v/v) gave 20 (60.9 mg). Total yield of 20 was 1.07 g (91%). 20: mp 151.5—152.5°C. IR (KBr): 1636 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 2.37 (1H, t, J=2.5 Hz), 5.00 (2H, d, J=2.5 Hz), 7.14—7.54 (3H, m), 8.14—8.39 (1H, m), 10.00 (1H, s). MS m/z: 261 and 263 (M+, 79Br and 81Br). Anal. Calcd for C12H8BrNO: C, 54.98; H, 3.08; N, 5.34. Found: C, 54.82; H, 2.98; N, 5.47.

1-Allyl-2-bromoindole-3-carbaldehyde (21) from 12 — A solution of allyl bromide (108.0 mg, 0.89 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added to a mixture of 12 (100.3 mg, 0.45 mmol), Bu4NBr (29.3 mg, 0.09 mmol), and K2CO3 (307.8 mg, 2.23 mmol) in THF (6 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h. After the same work-up as described in the preparation of 18, 115.3 mg (98%) of 21 was obtained. 21: mp 87—88°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from CHCl3). IR (KBr): 1652 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.90 (2H, ddd, J=5.0, 1.8, 1.2 Hz), 5.23 (1H, dt, J=17.0, 1.8 Hz), 5.26 (1H, dt, J=10.5, 1.2 Hz), 5.94 (1H, ddt, J=17.0, 10.5, 5.0 Hz), 7.26—7.33 (3H, m), 8.31—8.34 (1H, m), 10.06 (1H, s). MS m/z: 263 and 265 (M+, 79Br and 81Br). Anal. Calcd for C12H10BrNO·1/4H2O: C, 53.65; H, 3.94; N, 5.21. Found: C, 53.84; H, 3.73; N, 5.21.

(E,E)-2-Methyl-4-[3-(2-nitrovinyl)indol-2-yl]-3-buten-2-ol (25) from 27 — NH4OAc (736.1 mg, 9.50 mmol) was added to a solution of 27 (435.7 mg, 1.90 mmol) in MeNO2 (26 mL) and the mixture was heated at 90°C for 4 h with stirring. After cooling to rt, the resulting precipitates (16, 406.1 mg) were collected by filtration and washed with MeOH. The filtrate and washings were combined and H2O was added. The whole was extracted with CH2Cl2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a crystalline solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CH2Cl2–MeOH (95:5, v/v) to give 25 (75.7 mg). Total yield of 25 was 481.8mg (93%). 25: mp 246.5—247°C (decomp., red needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3250, 1578, 1360 cm–1. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5) δ: 1.55 (6H, s), 7.02 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 7.26—7.59 (4H, m), 7.85—8.05 (1H, m), 8.52 (1H, d, J=13.2 Hz), 8.77 (1H, d, J=13.2 Hz). MS m/z: 272 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C15H16N2O3: C, 66.16; H, 5.92; N, 10.29. Found: C, 65.97; H, 5.89; N, 10.46.

(E)-2-Methyl-4-[3-(2-nitroethyl)indol-2-yl]-3-buten-2-ol (26) from 25 — NaBH4 (173.5 mg, 4.59 mmol) was added to a solution of 25 (206.0 mg, 0.76 mmol) in MeOH (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h. After addition of AcOEt, the whole was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give 26 (199.5 mg, 96%). 26: mp 122.5—123°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from benzene). IR (KBr): 3520, 3310, 1554, 1380 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CD3OD) δ: 1.23 (6H, s), 3.48 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 4.62 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 6.31 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 6.71 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 6.83—7.52 (4H, m). MS m/z: 274 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C15H18N2O3: C, 65.67; H, 6.61; N, 10.21. Found: C, 65.89; H, 6.58; N, 10.23.

E-2-(3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-1-butenyl)indole-3-carbaldehyde (27) from 12 — General Procedure: A solution of 12 (405.4 mg, 1.81 mmol), (3-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-butenyl)tributyltin (1.00 g, 2.81 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (42.3 mg, 0.19 mmol), and Bu4NCl (1.00 g, 3.61 mmol) in DMF (6 mL) was heated at 115—120°C for 3 h with stirring. After evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure, brine was added, and the whole was extracted with AcOEt–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (2:1, v/v) to give 27 (362.1 mg, 87%). 27: mp 194—195°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3165, 2975, 1614 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CD3OD) δ: 1.47 (6H, s), 6.75 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 7.02—7.48 (3H, m), 7.20 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 7.99—8.23 (1H, m), 10.18 (1H, s). MS m/z: 229 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C14H15NO2: C, 73.34; H, 6.59; N, 6.11. Found: C, 73.17; H, 6.60; N, 6.32.

Methyl (E)-3-(3-Formylindol-2-yl)acrylate (28) from 12 — In the general procedure for 27, 12 (102.2 mg, 0.46 mmol), 2-(methoxycarbonyl)vinyl tributyltin (254.2 mg, 0.68 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (12.1 mg, 0.05 mmol), and Bu4NCl (248.6 mg, 0.90 mmol) were used. After the same work-up as described in the preparation of 27, 70.2 mg (67%) of 28 was obtained. 28: mp 261—262°C. IR (KBr): 3050, 1703, 1628 cm–1. 1H-NMR (pyridine-d5) δ: 3.72 (3H, s), 6.95 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 7.25—7.49 (3H, m), 8.50 (1H, d, J=16.0 Hz), 8.59—8.77 (1H, m), 10.71 (1H, s). The NH proton signal was not observed. MS m/z: 229 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C13H11NO3: C, 68.11; H, 4.84; N, 6.11. Found: C, 67.89; H, 4.76; N, 6.04.

2-Phenylindole-3-carbaldehyde (29) from 12 — In the general procedure for 27, 12 (41.1 mg, 0.18 mmol), tetraphenyl tin (117.3 mg, 0.27 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (4.3 mg, 0.02 mmol), and Bu4NCl (97.7 mg, 0.35 mmol) were used. After the same work-up and column-chromatography as described in the preparation of 27, 29 (27.7 mg, 68%) and 12 (3.9 mg, 10%) were obtained in the order of elution. 29: mp 260.5—263°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3120, 1628 cm–1. 1H-NMR (pyridine-d5) δ: 7.18—7.90 (8H, m), 8.53—8.91 (1H, m), 10.25 (1H, s). MS m/z: 221 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C15H11NO: C, 81.43; H, 5.01; N, 6.33. Found: C, 81.51; H, 4.92; N, 6.35.

2-(3-Pyridyl)indole-3-carbaldehyde (30) from 12 — In the general procedure for 27, 12 (103.1 mg, 0.46 mmol), (3-pyridyl)trimethyl tin (221.0 mg, 0.91 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (9.7 mg, 0.04 mmol), and Bu4NCl (261.3 mg, 0.94 mmol) were used. After the same work-up and column-chromatography as described in the preparation of 27, 30 (39.1 mg, 38%), 31 (10.9 mg, 15%), and indole-3-carbaldehyde (5.5 mg, 8%) were obtained in the order of elution. 30: mp 246—246.5°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3430, 3130, 1628 cm–1. 1H-NMR (pyridine-d5) δ: 7.28—7.70 (4H, m), 8.14 (1H, ddd, J=8.0, 2.2, 1.8 Hz), 8.75—8.96 (2H, m), 9.27 (1H, dd, J=2.2, 0.8 Hz), 10.41 (1H, s). MS m/z: 222 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C14H10N2O: C, 75.65; H, 4.54; N, 12.61. Found: C, 75.48; H, 4.77; N, 12.50.

2-Methylindole-3-carbaldehyde (31) from 12 — In the general procedure for 27, 12 (467.8 mg, 2.09 mmol), tetramethyl tin (562.2 mg, 3.12 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (42.7 mg, 0.19 mmol), and Bu4NCl (1.34 g, 4.84 mmol) were used. After the same work-up and column-chromatography as described in the preparation of 27, 31 (130.0 mg, 39%) and indole-3-carbaldehyde (18.1 mg, 6%) were obtained in the order of elution. 31: mp 204—205°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3250, 1635 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CD3OD) δ: 2.63 (3H, s), 6.89—7.39 (3H, m), 7.79—8.12 (1H, m), 9.82 (1H, s). MS m/z: 159 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C10H9NO: C, 75.45; H, 5.70; N, 8.80. Found: C, 75.50; H, 5.62; N, 8.82.

2-(2-Pyridyl)indole-3-carbaldehyde (32) from 12 — In the general procedure for 27, 12 (100.5 mg, 0.45 mmol), (2-pyridyl)trimethyl tin (1.07 g, 4.43 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (10.9 mg, 0.05 mmol), and Bu4NCl (246.1 mg, 0.89 mmol) were used. After the same work-up and column-chromatography as described in the preparation of 27, unreacted 12 (21.4 mg, 21%), 32 (5.0 mg, 5%), 31 (0.5 mg, 1%), and indole-3-carbaldehyde (2.4 mg, 4%) were obtained in the order of elution. 32: mp 225.5—226.5°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3060, 1619 cm–1. 1H-NMR (pyridine-d5) δ: 7.12—7.70 (4H, m), 7.75 (1H, dd, J=7.5, 2.0 Hz), 8.70 (1H, dt, J=8.0, 1.0 Hz), 8.65—8.78 (1H, m), 8.78—8.98 (1H, m), 11.04 (1H, s). MS m/z: 222 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C14H10N2O: C, 75.65; H, 4.54; N, 12.61. Found: C, 75.42; H, 4.38; N, 12.83.

Hydroxy-6-nitroindole-3-carbaldehyde (38) from 1-Methoxy-6-nitroindole-3-carbaldehyde (39) — i) Method A: The formation of 38 in 90% yield by the reaction of 39 with DABCO was reported in the preceding paper.

ii) Method B: A solution of KI (960.0 mg, 5.78 mmol) in H2O (1 mL) was added to a solution of 39 (32.8 mg, 0.15 mmol) in DMF (3 mL), and the mixture was heated at 120°C for 36 h with stirring. After evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure, AcOEt was added to the residue. The same work-up of the organic layer as described in the Method A for 38, gave unreacted 39 (7.3 mg, 22%), 37 (1.1 mg, 4%), and 38 (17.9 mg, 58%) in the order of elution. 38 is identical with the authentic sample.72

2-Bromo-6-nitroindole-3-carbaldehyde (40) from 38 — POBr3 (529.4 mg, 1.85 mmol) was added to a solution of 38 (60.9 mg, 0.30 mmol) in anhydrous THF (4 mL) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 5 h. After evaporation of the solvent, H2O was added to the residue, and the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give 40 (65.3 mg, 82%) and 37 (6.2 mg, 11%) in the order of elution. 40: mp 296—298°C (decomp., colorless prisms, recrystallized from AcOEt). IR (KBr): 1631 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 8.12 (1H, dd, J=8.8, 1.6 Hz), 8.24 (1H, d, J=8.8 Hz), 8.27 (1H, d, J=1.6 Hz), 9.95 (1H, s). The proton at the 1-position did not appear. MS m/z: 268 and 270 (M+, 79Br and 81Br). Anal. Calcd for C9H5BrN2O3: C, 40.18; H, 1.87; N, 10.41. Found: C, 40.16; H, 1.93; N, 10.47.

2,6-Dibromoindol-3-ylmethanol (36) from 35 — NaBH4 (150.0 mg, 3.95 mmol) was added to a solution of 35 (65.2 mg, 0.22 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h. After evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure, AcOEt was added to the residue. The whole was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v) to give 36 (44.2 mg, 67%). 36: colorless oil. IR (film): 3398, 3213, 1614 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.48 (1H, br s), 4.80 (2H, s), 7.26 (1H, dd, J=8.5, 1.7 Hz), 7.43 (1H, d, J=1.7 Hz), 7.55 (1H, d, J=8.5 Hz), 8.18 (1H, br s). High-resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C9H779Br2NO: 302.8895. Found: 302.8915. Calcd for C9H779Br81BrNO: 304.8874. Found: 304.8852. Calcd for C9H781Br2NO: 306.8854. Found: 306.8829.

1-(2-Methyl-1-propenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline (44) from 26 — A solution of

26 (174.9 mg, 0.64 mmol) in THF (19.5 mL) was added to a mixture of Zn powder (897.2 mg, 13.7 mmol) [washed with 6% HCl (4 mL)] in 6% HCl (6.5 mL) at 0°C and the mixture was refluxed for 5 min with stirring. Unreacted Zn was filtered off and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was made basic by adding 8% aqueous NaOH and the whole was extracted with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with CHCl

3–MeOH–28% aq. NH

3 (46:2:0.2, v/v) to give

44 (22.5 mg, 50%).

44: mp 160—161°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from CH

2Cl

2, lit.,[

10] mp 158—159°C). IR (KBr): 3400, 1092 cm

–1.

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 1.82 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 1.88 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 2.65—2.89 (2H, m), 2.89—3.55 (2H, m), 4.83 (1H, br d,

J=9.5 Hz), 5.26 (1H, dt,

J=9.5, 1.2 Hz), 6.92—7.33 (3H, m), 7.33—7.53 (1H, m), 7.64 (1H, br s). MS

m/z: 226 (M

+).

Anal. Calcd for C

15H

18N

2·1/4H

2O: C, 78.05; H, 8.07; N, 12.13. Found: C, 78.47; H, 8.09; N, 11.84.

2-Methoxycarbonyl-1-(2-methyl-1-propenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline (45) from 44 — A solution of ClCO

2Me (38.6 mg, 0.41 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (1 mL) was added to a solution of

44 (54.0 mg, 0.24 mmol) and Et

3N (80.0 mg, 0.79 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (3 mL) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h. Saturated NaHCO

3 was added and the whole was extracted with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was recrystallized from MeOH to give

45 (47.5 mg) as colorless prisms. The mother liquor was subjected to p-TLC on SiO

2 with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (95:5, v/v) as a developing solvent. Extraction from the band having an

Rf value of 0.93—1.00 with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (95:5, v/v) gave

45 (10.3 mg). Total yield of

45 was 58.7 mg (85%).

45: mp 186—189°C (lit.,[

74] mp 180—181°C). IR (KBr): 3400, 3040, 1092 cm

–1.

1H NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 1.77 (3H, d,

J=1.4 Hz), 1.98 (3H, d,

J=1.4 Hz), 2.64—2.88 (2H, m), 2.88—3.37 (1H, m), 3.73 (3H, s), 4.39 (1H, d,

J=12.5 Hz), 5.30 (1H, d,

J=10.0 Hz), 5.88 (1H, d,

J=10.0 Hz), 6.91—7.32 (3H, m), 7.36—7.52 (1H, m), 7.59 (1H, br s). High-resolution MS

m/z: Calcd for C

17H

20N

2O

2: 284.1524. Found: 284.1526.

Borrerine (46) from 45 — LiAlH

4 (98.6 mg, 2.60 mmol) was added to a solution of

45 (46.3 mg, 0.16 mmol) in THF (8 mL) at 0°C and the mixture was refluxed for 5 h with stirring. After addition of MeOH and 10% aqueous Rochelle salt under ice cooling, the whole was extracted with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was subjected to p-TLC on SiO

2 with CHCl

3–MeOH–28% aq. NH

3 (46:5:0.5, v/v) as a developing solvent. Extraction from the band having an

Rf value of 0.74—0.90 with CHCl

3–MeOH–28% aq. NH

3 (46:5:0.5, v/v) gave

46 (28.2 mg, 70%).

46: mp 105—106°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from hexane, lit.[

10] mp 102—103°C). IR (KBr): 3200 cm

–1.

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 1.86 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 1.88 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 2.48—3.29 (4H, m), 4.05 (1H, dt,

J=9.5, 1.2 Hz), 5.18 (1H, br d,

J=9.5 Hz), 6.92—7.34 (3H, m), 7.34—7.63 (2H, m). High-resolution MS

m/z: Calcd for C

16H

20N

2: 240.1625. Found: 240.1630.

Vulcanine (47) from 44 — A solution of

t-BuOCl (42.4 mg, 0.39 mmol) in THF (1 mL) was added to a suspension of

44 (37.0 mg, 0.16 mmol) and powdered NaOH (32.1 mg, 0.80 mmol) in THF (4 mL) and the mixture was stirred at rt for 64 h. H

2O was added and the whole was extracted with AcOEt. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was subjected to p-TLC on SiO

2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) as a developing solvent. Extraction from the band having an

Rf value of 0.47—0.65 with AcOEt gave

47 (18.5 mg, 51%).

47: pale yellow oil. IR (CHCl

3): 1645, 1623, 1567, 1492, 1452, 1420, 1380, 1316, 1235 cm

–1.

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 2.00 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 2.01 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 6.60 (1H, t,

J=1.2 Hz), 7.28 (1H, ddd,

J=8.1, 6.4, 1.7 Hz), 7.51 (1H, ddd,

J=8.1, 1.7, 1.0 Hz), 7.53 (1H, ddd,

J=8.1, 6.4, 1.0 Hz), 7.82 (1H, d,

J=5.4 Hz), 8.11 (1H, d,

J=8.1 Hz), 8.46 (1H, d,

J=5.4 Hz), 8.57 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D

2O).

13C-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 20.5, 26.7, 111.9, 113.0, 119.0, 120.3, 121.6, 121.8, 128.8, 129.5, 134.0, 136.8, 140.7, 140.8, 143.8. UV

λmax (MeOH) nm (log

ε): 214 (4.36), 239 (4.49), 260 (sh, 4.23), 292 (4.14), 356 (3.79). MS

m/z: 222 (M

+), 207, 182, 103. High-resolution MS

m/z: Calcd for C

15H

14N

2: 222.1157. Found: 222.1154.

47·HCl: mp 189—192°C (yellow needles, recrystallized from Et

2O–MeOH, lit.,[

75] mp 103°C). IR (KBr): 3340, 1640, 1599, 1442, 761 cm

–1.

1H-NMR (CD

3OD) δ: 1.93 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 2.22 (3H, d,

J=1.2 Hz), 6.74 (1H, t,

J=1.2 Hz), 7.47 (1H, ddd,

J=8.1, 6.8, 1.0 Hz), 7.76 (1H, dt,

J=8.3, 1.0 Hz), 7.80 (1H, ddd,

J=8.3, 6.8, 1.0 Hz), 8.35 (1H, d,

J=6.4 Hz), 8.41 (1H, dt,

J=8.1, 1.0 Hz), 8.55 (1H, d,

J=6.4 Hz).

13C-NMR (CD

3OD) δ: 20.9, 26.6, 113.9, 114.2, 116.6, 121.5, 123.0, 124.1, 129.5, 133.1, 134.8, 135.2, 137.4, 145.4, 152.5.

Anal. Calcd for C

15H

14N

2·HCl·1/4H

2O: C, 68.44; H, 5.93; N, 10.64. Found: C, 68.51; H, 5.83; N, 10.68.

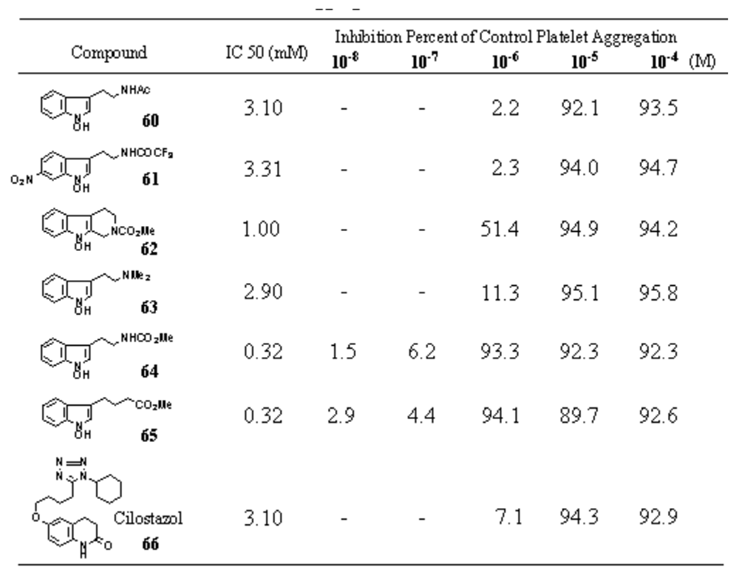

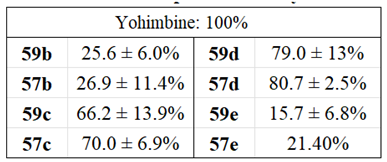

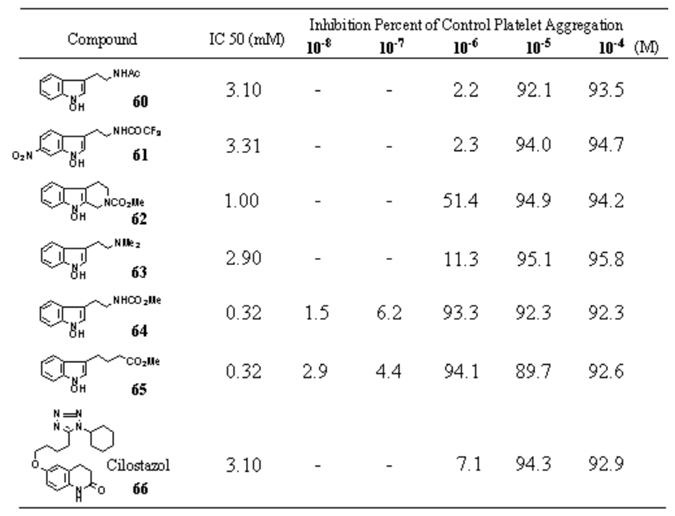

Table 28.

Effects of 1-Hydroxyindoles on Arachidonic Acid Induced Platelet Aggregation in Rabbit PRP 60-66.

Table 28.

Effects of 1-Hydroxyindoles on Arachidonic Acid Induced Platelet Aggregation in Rabbit PRP 60-66.

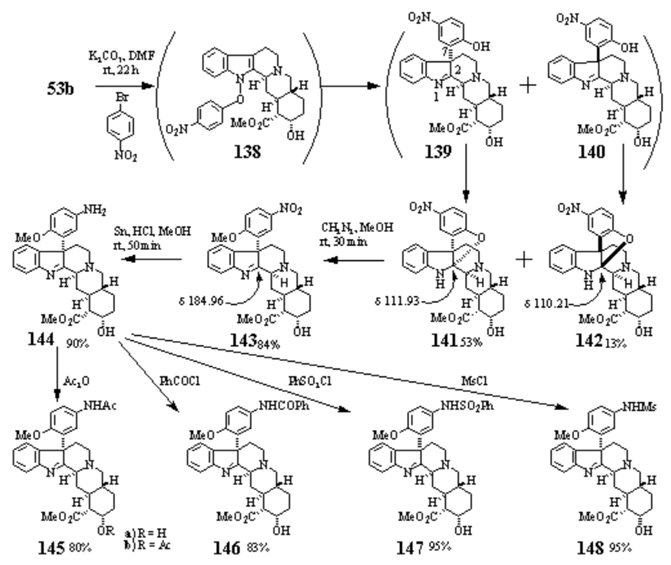

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of candidates of osteoporosis.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of candidates of osteoporosis.

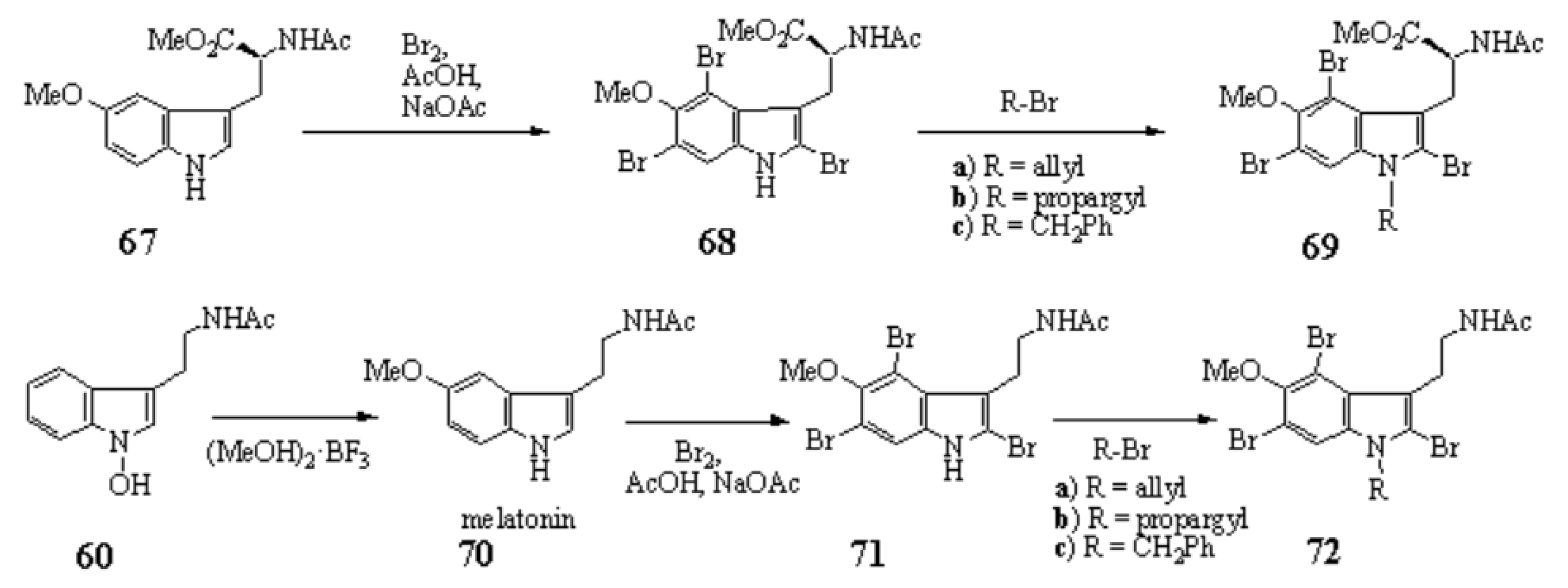

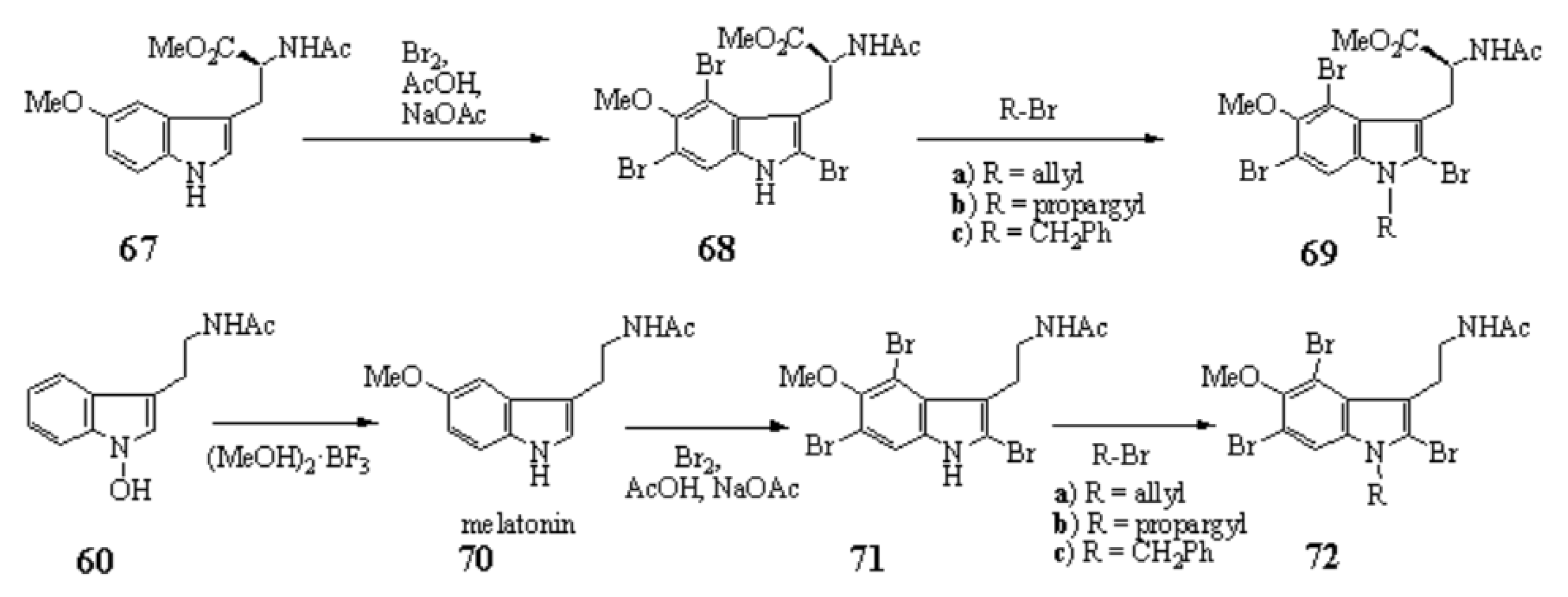

23.2. Tryptophan Derivatives:

Synthesis of (

S)-(+)-

N-acetyl-2,4,6-tribromo-5-methoxytryptophan methyl ester (68) from (

S)-(+)-

N-acetyl-5-methoxy tryptophan methyl ester (67) — To a solution of (

S)-(+)-

N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptophan methyl ester (67)[

84] (56.6 mg, 0.20 mmol) in 4.5 mL of AcOH was added a solution of Br

2 (1.0 mL, 0.59 mmol), separately prepared by dissolving 458.0 mg of Br

2 and 41.8 mg of NaOAc in 5.0 mL of AcOH, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. After the addition of 10% aqueous Na

2S

2O

2, the mixture was made alkaline by adding 40% aqueous NaOH under ice cooling and extracted with CHCl

3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a yellow solid, which was column-chromatographed on SiO

2 with CHCl

3–MeOH (99.5:0.5, v/v) to give an inseparable 1:2 mixture (28.4 mg) of (S)-(+)-N-acetyl-2,6-dibromo- and (S)-(+)-N-acetyl-2,4,7-tribromo--5-methoxytryptophan methyl ester, and 68 (53.7 mg, 52%) in the order of elution. 68: mp 198–199°C (colorless granules, recrystallized from AcOEt). IR (KBr): 3307, 1730, 1647, 1556, 1300, 1232, 1028 cm

-1.

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 1.88 (3H, s), 3.29 (1H, dd,

J = 9.8, 14.6 Hz), 3.58 (1H, dd,

J = 5.2, 14.6 Hz), 3.77 (3H, s), 3.88 (3H, s), 5.01 (1H, ddd,

J = 5.2, 8.6, 9.8 Hz, changed to dd,

J = 5.2, 9.8 Hz on addition of D

2O), 6.17 (1H, br d,

J = 8.6 Hz, disappeared on addition of D

2O), 7.37 (1H, s), 8.70 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D

2O). MS

m/z: 530 (M

+), 528 (M

+), 526 (M

+), 524 (M

+).

Anal. Calcd for C

15H

15Br

3N

2O

4: C, 34.19; H, 2.87; N, 5.32. Found: C, 34.24; H, 2.89; N, 5.18. Optical Rotation [α]

D26 +14.8° (DMSO, c 0.200). [α]

D27 +1.47° (MeOH, c 0.204). [α]

D28 +4.4° (CHCl

3, c 0.203).

Synthesis of (S)-(+)-N-acetyl-1-allyl-2,4,6-tribromo-5-methoxytryptophan methyl ester (69a) from 68 — To a solution of 68 (39.8 mg, 0.08 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 2.5 mL) was added K2CO3 (36.5 mg, 0.26 mmol) and allyl bromide (0.13 mL, d = 1.398, 1.51 mmol). After stirring at room temperature for 30 min, water was added to the reaction mixture. The whole was extracted with AcOEt. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a yellow oil. Purification by column-chromatography on SiO2 with CHCl3 to give 69a (42.4 mg, 99%). 69a: mp 191–192°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from AcOEt). IR (KBr): 3303, 1732, 1645, 1547, 1228, 1016 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.86 (3H, s), 3.34 (1H, dd, J = 9.8, 14.7 Hz), 3.62 (1H, dd, J = 5.4, 14.7 Hz), 3.74 (3H, s), 3.89 (3H, s), 4.75 (2H, m), 4.83 (1H, d, J = 17.1 Hz), 5.01 (1H, ddd, J = 5.4, 8.7, 9.8 Hz, changed to dd, J = 5.4, 9.8 Hz on addition of D2O), 5.19 (1H, d, J = 10.3 Hz), 5.86 (1H, tdd, J = 4.8, 10.3, 17.1 Hz), 6.12 (1H, br d, J = 8.7 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 7.41 (1H, s). MS m/z: 570 (M+), 568 (M+), 566 (M+), 564 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C18H19Br3N2O4: C, 38.12; H, 3.38; N, 4.94. Found: C, 37.97; H, 3.43; N, 4.86. Optical Rotation [α]D26 +13.8° (CHCl3, c 0.203).

Synthesis of (S)-(+)-N-acetyl-2,4,6-tribromo-5-methoxy-1-propargyltryptophan methyl ester (69b) from 68 — To a solution of 68 (23.6 mg, 0.04 mmol) in DMF (2.0 mL) was added K2CO3 (21.6 mg, 0.16 mmol) and propargyl bromide (0.08 mL, d = 1.335, 0.9 mmol). After stirring at room temperature for 30 min, water was added to the reaction mixture. The whole was extracted with AcOEt. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a pink oil. Purification by column-chromatography on SiO2 with CHCl3 to give 69b (23.9 mg, 94%). 69b: mp 284–285°C (decomp., measured with a sealed tube, colorless needles, recrystallized from CHCl3–MeOH). IR (KBr): 3284, 3224, 2114, 1724, 1647, 1552, 1230, 1016 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 1.82 (3H, s), 3.28 (1H, dd, J = 7.1, 14.9 Hz), 3.33 (1H, dd, J = 8.7, 14.9 Hz), 3.33 (1H, t, J = 2.4 Hz), 3.48 (3H, s), 3.80 (3H, s), 4.47 (1H, ddd, J = 7.1, 7.1, 8.7 Hz, changed to dd, J = 7.1, 8.7 Hz on addition of D2O), 5.13 (2H, dt, J = 2.4, 4.2 Hz), 8.02 (1H, s), 8.44 (1H, br d, J = 7.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O). MS m/z: 568 (M+), 566 (M+), 564 (M+), 562 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C18H17Br3N2O4: C, 38.26; H, 3.03; N, 4.96. Found: C, 38.11; H, 3.12; N, 4.83. Optical Rotation [α]D24 +7.7° (DMSO, c 0.202).

Synthesis of (S)-(+)-N-acetyl-1-benzyl-2,4,6-tribromo-5-methoxytryptophan methyl ester (69c) from 68 — To a solution of 68 (19.6 mg, 0.04 mmol) in DMF (1.5 mL) was added K2CO3 (18.0 mg, 0.13 mmol) and benzyl bromide (0.09 mL, d = 1.44, 0.7 mmol). After stirring at room temperature for 30 min, water was added to the reaction mixture. The whole was extracted with AcOEt–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a yellow oil. Preparative thin-layer chromatography was performed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH (99:1, v/v) as a developing solvent. Extraction of the band having an Rf value of 0.18 to 0.29 with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v) afforded 69c (22.0 mg, 96%). 69c: mp 226–227°C (colorless needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3298, 1732, 1643, 1550, 1414, 1230, 1018 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 1.80 (3H, s), 3.28 (1H, dd, J = 7.1, 14.4 Hz), 3.40 (1H, dd, J = 8.5, 14.7 Hz, appeared on addition of D2O), 3.47 (3H, s), 3.79 (3H, s), 4.55 (1H, ddd, J = 7.1, 7.1, 8.5 Hz, changed to dd, J = 7.1, 8.5 Hz on addition of D2O), 5.53 (2H, s), 6.96 (2H, d, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.25 (1H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.31 (2H, t, J = 7.1 Hz), 7.90 (1H, s) 8.45 (1H, d, J = 7.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O). MS m/z: 620 (M+), 618 (M+), 616 (M+), 614 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C22H21Br3N2O4: C, 42.82; H, 3.43; N, 4.54. Found: C, 42.69; H, 3.47; N, 4.56. Optical Rotation [α]D24 +8.3° (CHCl3, c 0.204)

-

1)

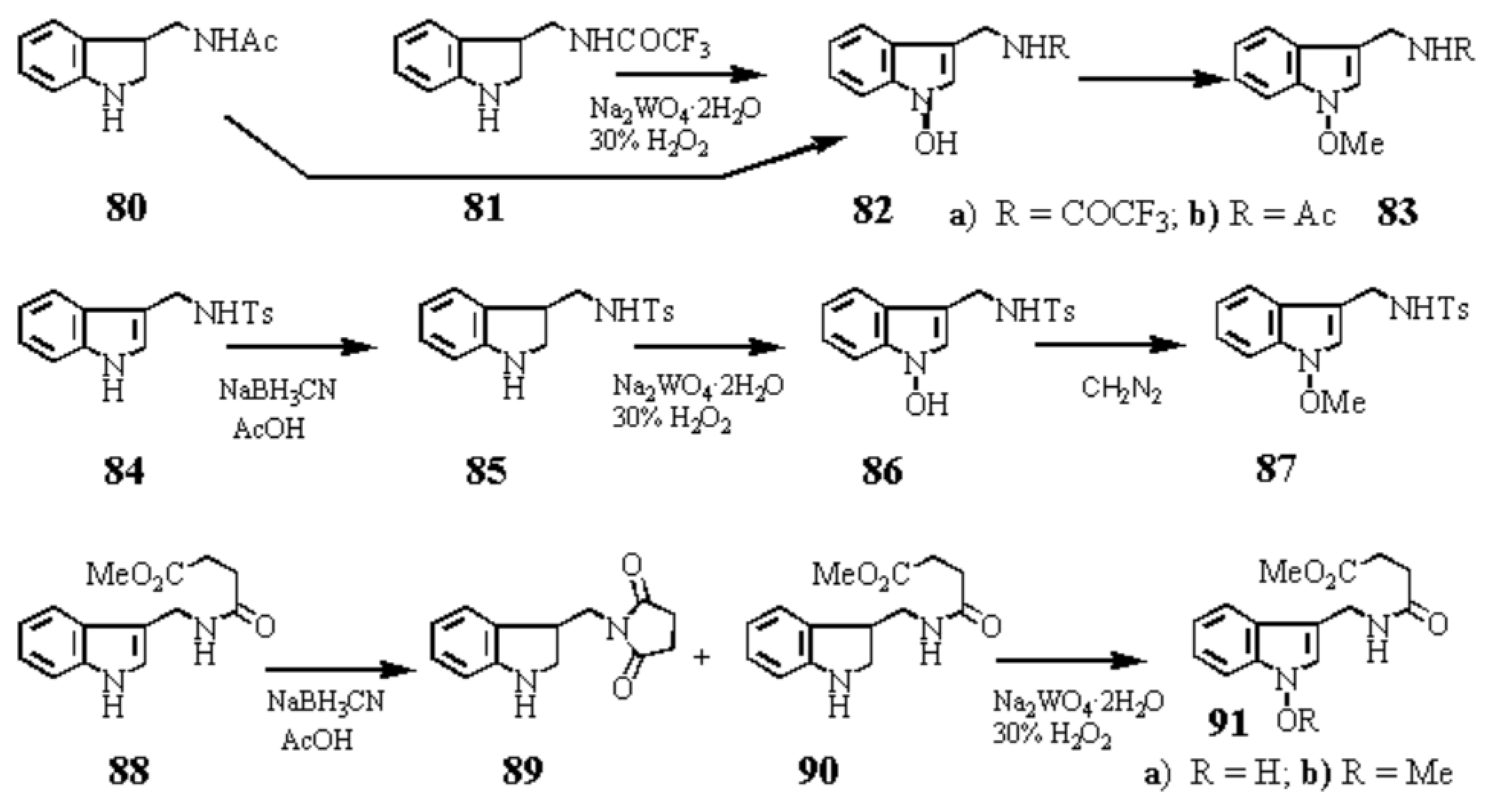

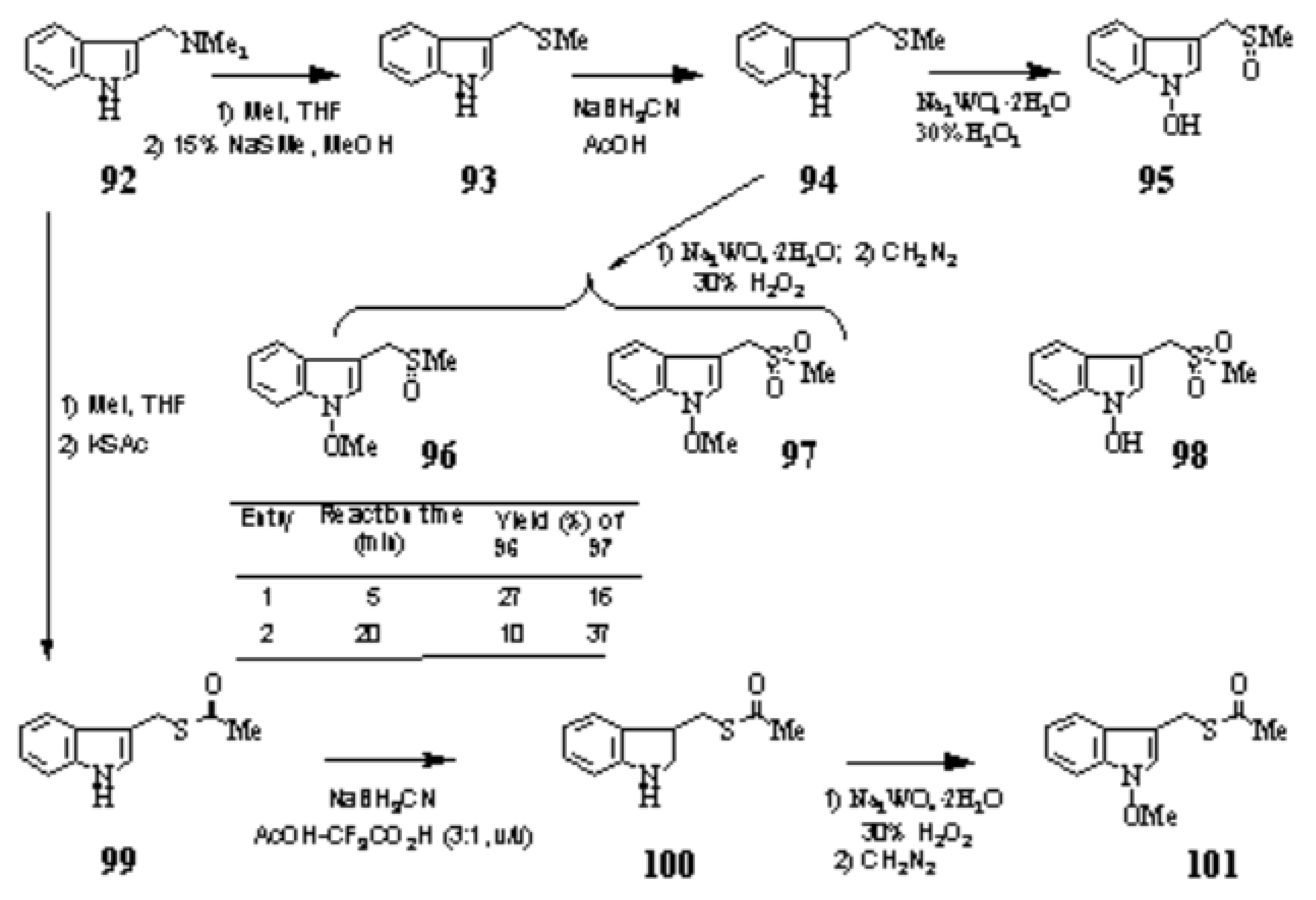

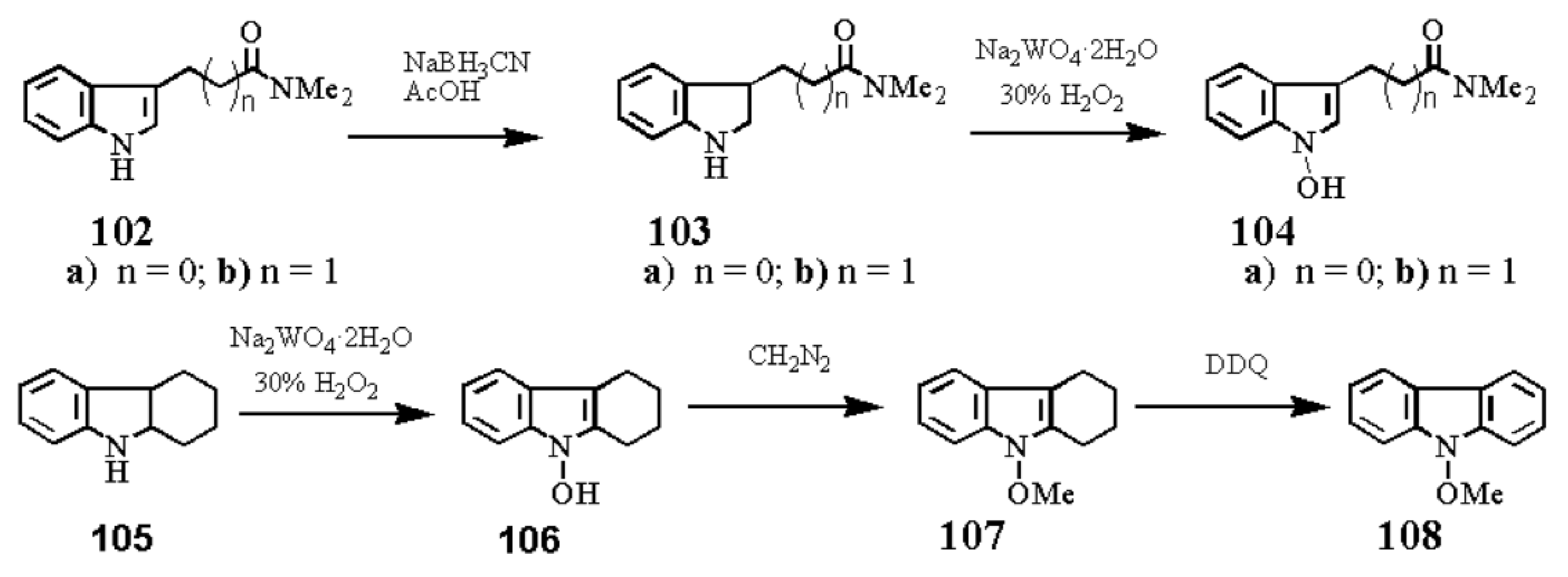

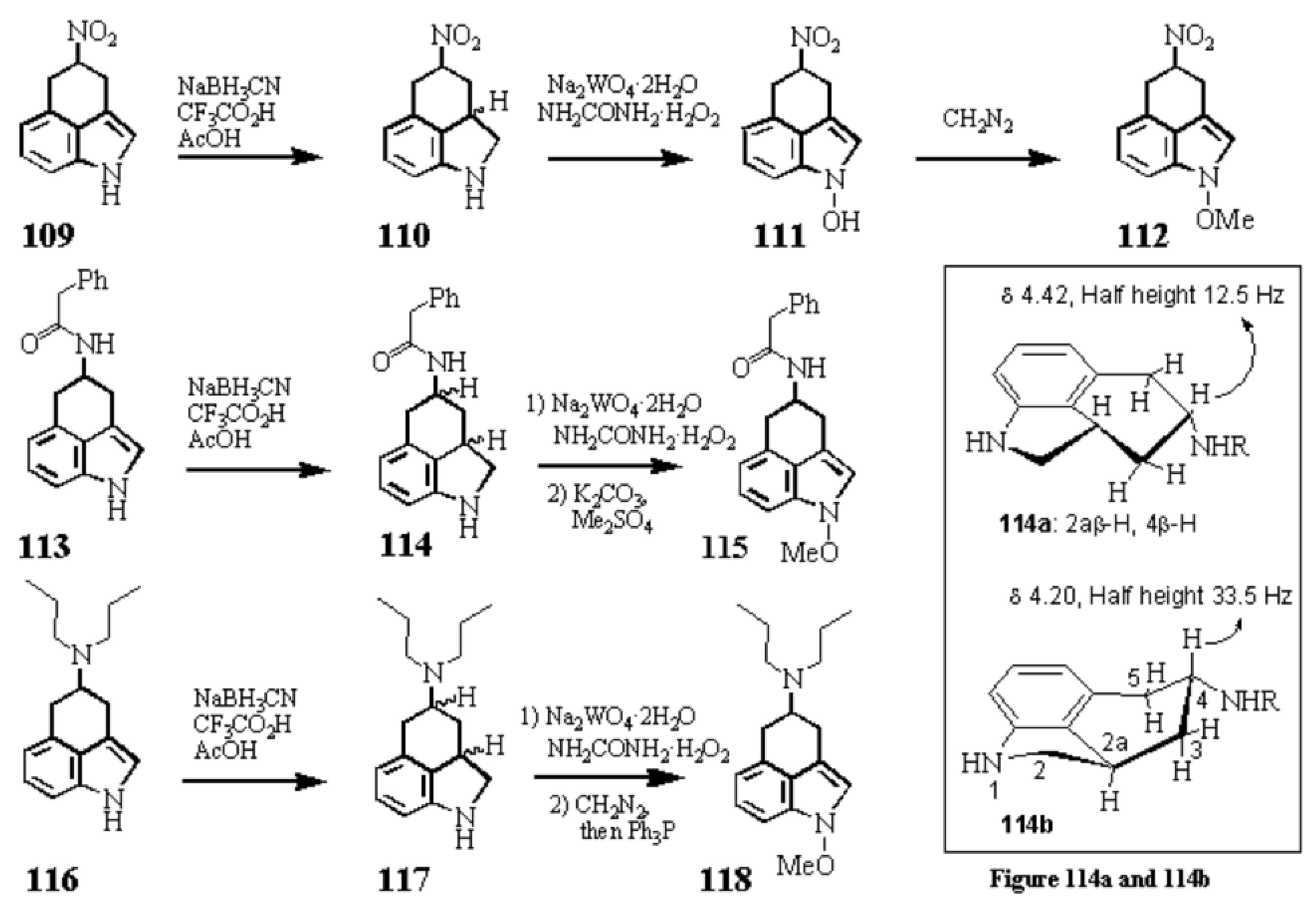

Tryptamine derivatives

Melatonin (70) from Nb-acetyl-1-hydroxytryptamine (60) — 50% (MeOH)2·BF3 (15.0 mL) was added to a solution of 60 (150.0 mg, 0.688 mmol) in MeOH (10.0 mL) under ice cooling, and the mixture was refluxed for 30 min with stirring. After evaporation of the solvent, the whole was made neutral by adding 8% NaOH under ice cooling and extracted with CH2Cl2–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CH2Cl2–MeOH (98:2, v/v) to give 70 (121.6 mg, 72%). 70 was identical with commercially available authentic sample in every spectral data.

2,4,6-Tribromomelatonin (71) from melatonin (70) — A 0.56 M solution of Br2 in AcOH (containing 1 mmol of NaOAc, 3.30 mL, 1.85 mmol) was added to a solution of 70 (144.5 mg, 0.62 mmol) in AcOH (12 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. After the addition of Na2S2O3 (1.0 mL) and H2O, the mixture was made basic with 40% NaOH under ice cooling and extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–MeOH (99:1, v/v) to give 71 (272.2 mg, 94%). 71: mp >300 °C (decomp., colorless powder, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3371, 3370, 1653, 1543, 1446, 1406, 1306, 1022 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.78 (3H, s), 2.97 (2H, t, J=7.3 Hz), 3.25 (2H, q, J=7.3 Hz), 3.77 (3H, s), 7.52 (1H, s), 7.89 (1H, br t, J=5.6 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 12.15 (1H, br t, J=7.3 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C13H13Br3N2O2: C, 33.29; H, 2.79; N, 5.97. Found: C, 33.27; H, 2.82; N, 5.85.

1-Allyl-2,4,6-tribromomelatonin (72a) from 2,4,6-tribromomelatonin (71) — General procedure. K2CO3 (31.1mg, 0.22 mmol) was added to a solution of 71 (30.2 mg, 0.064 mmol) in DMF (2.0 mL), and the mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. To the resultant mixture, allyl bromide (0.11 mL, 1.28 mmol) was added and stirred at rt for 1.5 h. After the addition of H2O, the mixture was extracted with AcOEt–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt to give 72a (31.0 mg, 95%). 72a: mp 142–143 °C (colorless fine needles, recrystallized from AcOEt–hexane). IR (KBr): 3284, 1633, 1562, 1456, 1412, 1298, 1018 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.93 (3H, s), 3.24 (2H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 3.58 (2H, q, J=6.6 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 4.76 (2H, dt, J=4.9, 1.7 Hz), 4.89 (1H, d, J=16.6 Hz), 5.20 (1H, d, J=10.3 Hz), 5.55 (1H, br t, disappeared on addition of D2O), 5.87 (1H, ddt, J=16.6, 10.3, 4.9 Hz), 7.4 (1H, s). Anal. Calcd for C16H17Br3N2O2: C, 37.75; H, 3.37; N, 5.50. Found: C, 37.75; H, 3.37; N, 5.42.

1-Propargyl-2,4,6-tribromomelatonin (72b) from 2,4,6-tribromomelatonin (71) — In the general procedure for the preparation of 72a, K2CO3 (31.9mg, 0.22 mmol), 71 (30.1 mg, 0.064mmol), and propargyl chloride (0.09 mL, 1.28 mmol) were used. After work–up, 31.6 mg (97%) of 72b was obtained. 72b: mp 199–200 °C (colorless fine needles, recrystallized from AcOEt–hexane). IR (KBr): 3286, 2117, 1628, 1558, 1456, 1435, 1410, 1294, 1018 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.93 (3H, s), 2.34 (1H, t, J=2.4 Hz), 3.23 (2H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 3.58 (2H, q, J=6.6 Hz), 3.89 (3H, s), 4.91 (2H, d, J=2.4 Hz), 5.54 (1H, br t, J=6.6 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 7.58 (1H, s). Anal. Calcd for C13H15Br3N2O2: C, 37.90; H, 2.98; N, 5.53. Found: C, 37.78; H, 3.00; N, 5.44.

1-Benzyl-2,4,6-tribromomelatonin (72c) from 2,4,6-tribromomelatonin (71) — In the general procedure for the preparation of 74a, K2CO3 (31.8mg, 0.30 mmol), 71 (40.1 mg, 0.086 mmol), and benzyl bromide (0.20 mL, 1.72 mmol) were used. After work–up, 40.3 mg (83%) of 72c was obtained. 72c: mp 218–219 °C (colorless fine needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3280, 1630, 1547, 1454, 1414, 1360, 1298, 1014 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.91 (3H, s), 3.26 (2H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 3.61 (2H, td, J=12.7, 6.6 Hz), 3.88 (3H, s), 5.36 (2H, s), 5.54 (1H, br t, J=6.6 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 7.01 (2H, d, J=6.6 Hz), 7.27-7.33 (3H, m), 7.39 (1H, s). Anal. Calcd for C20H19Br3N2O2: C, 42.97; H, 3.43; N, 5.01. Found: C, 42.76; H, 3.40; N, 4.86.

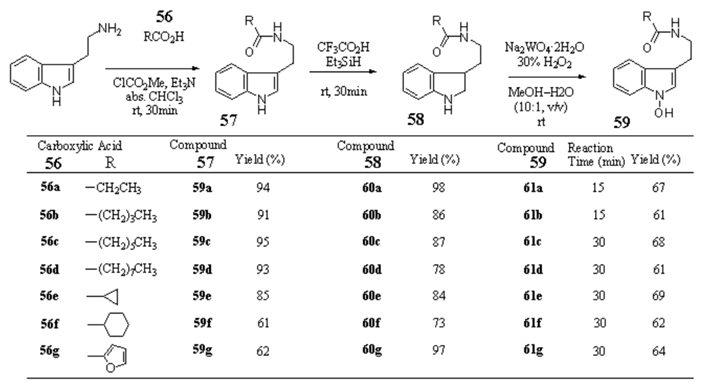

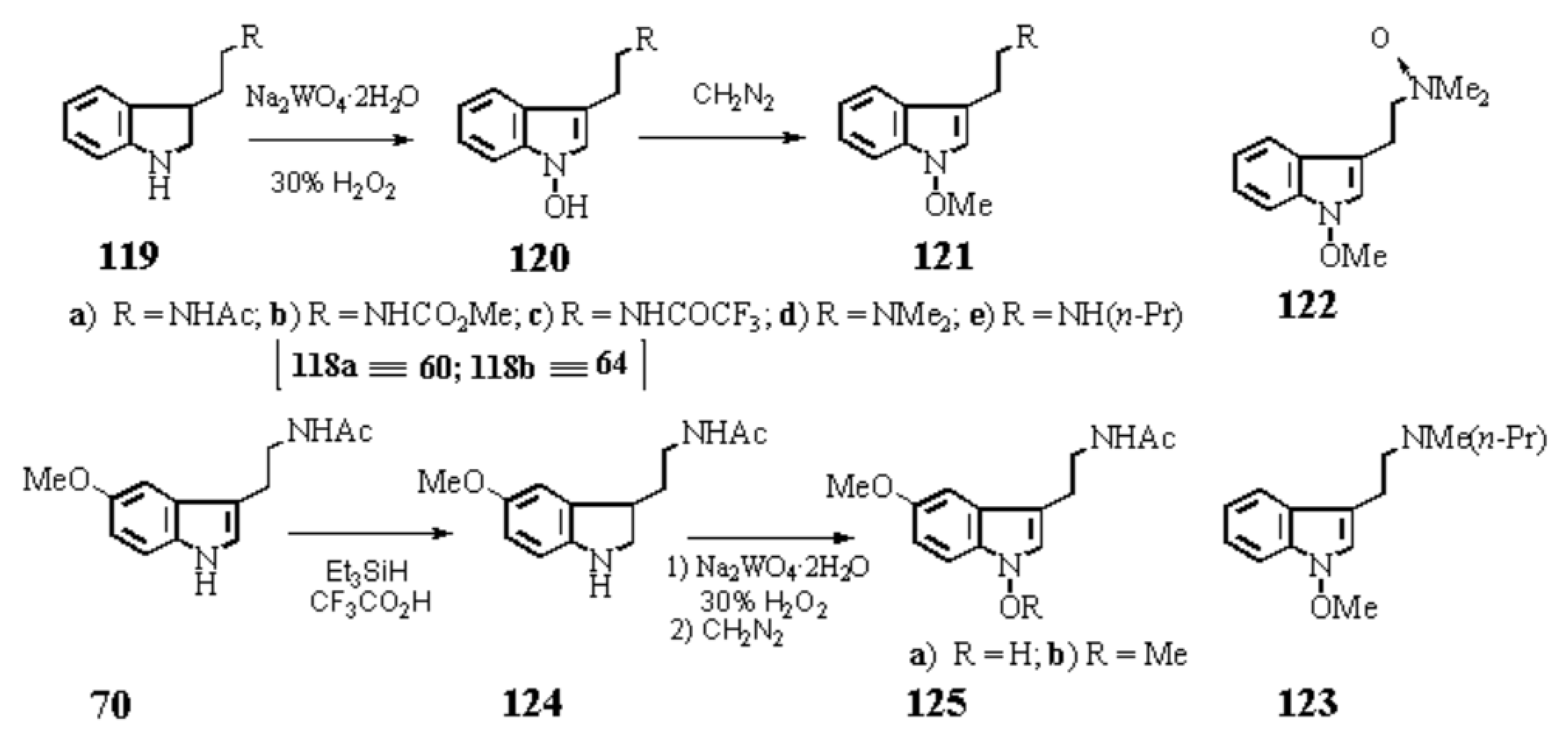

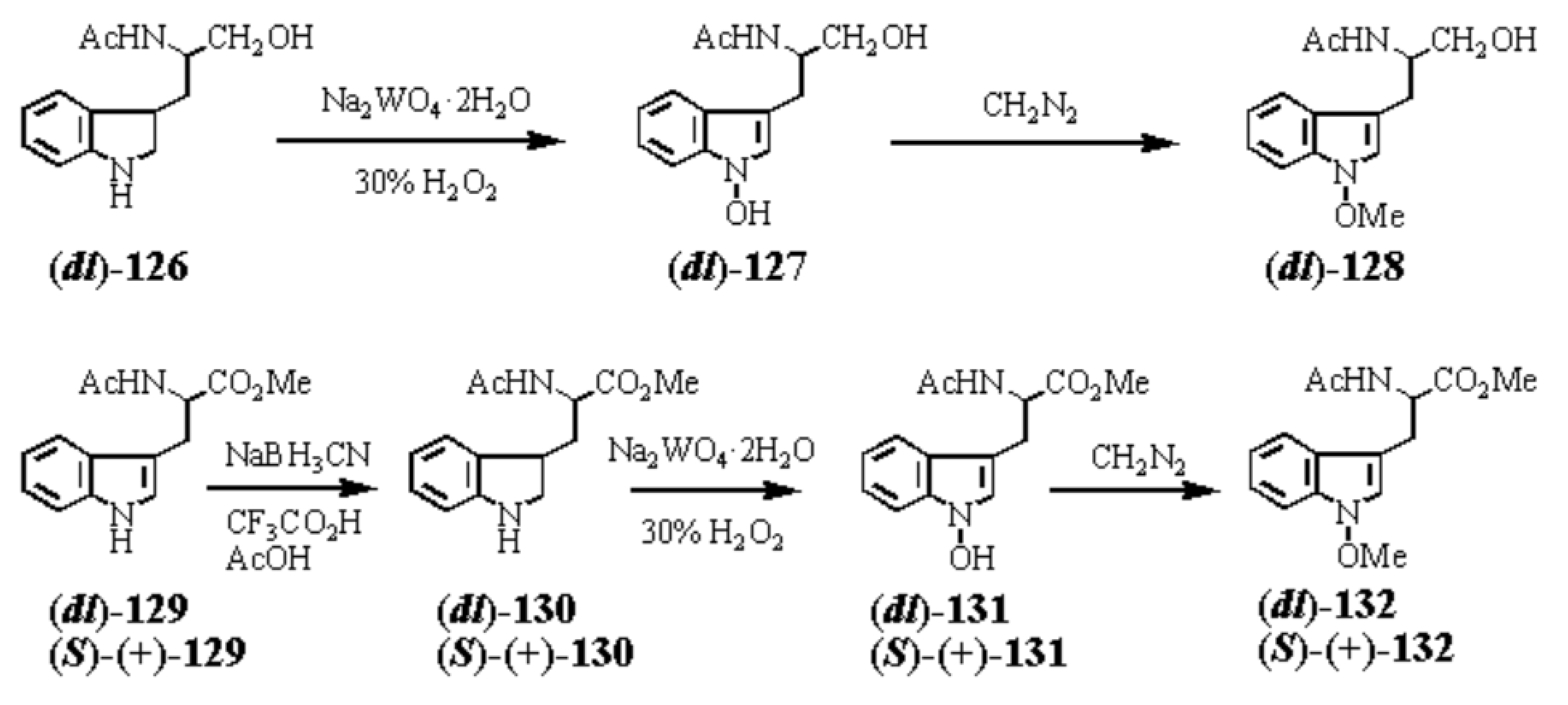

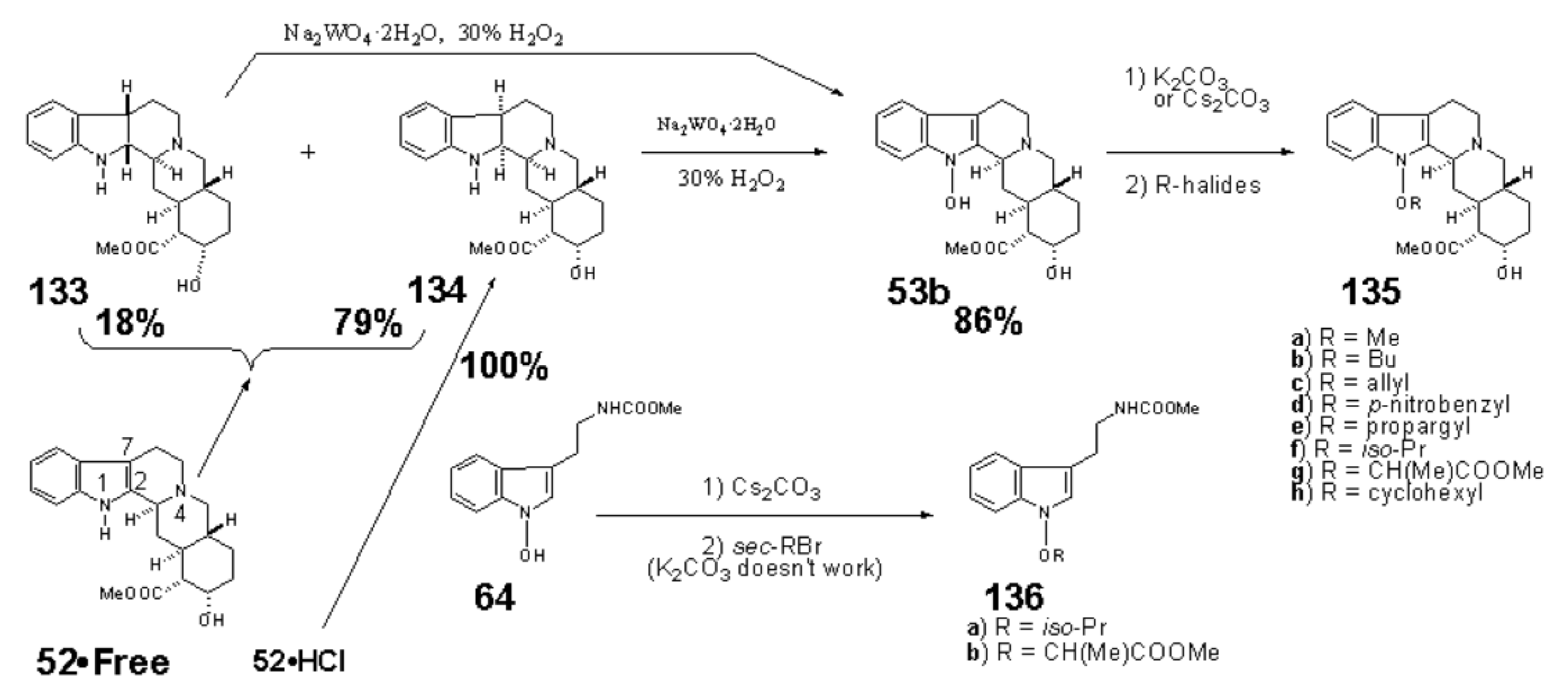

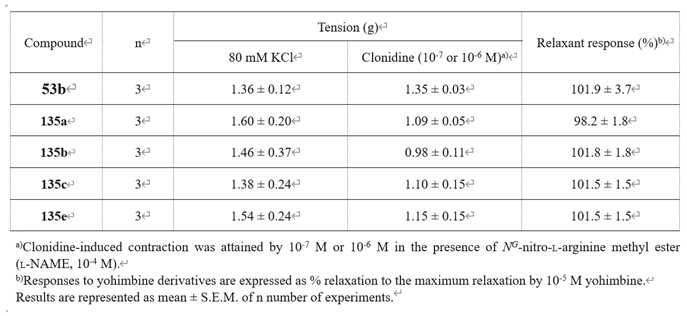

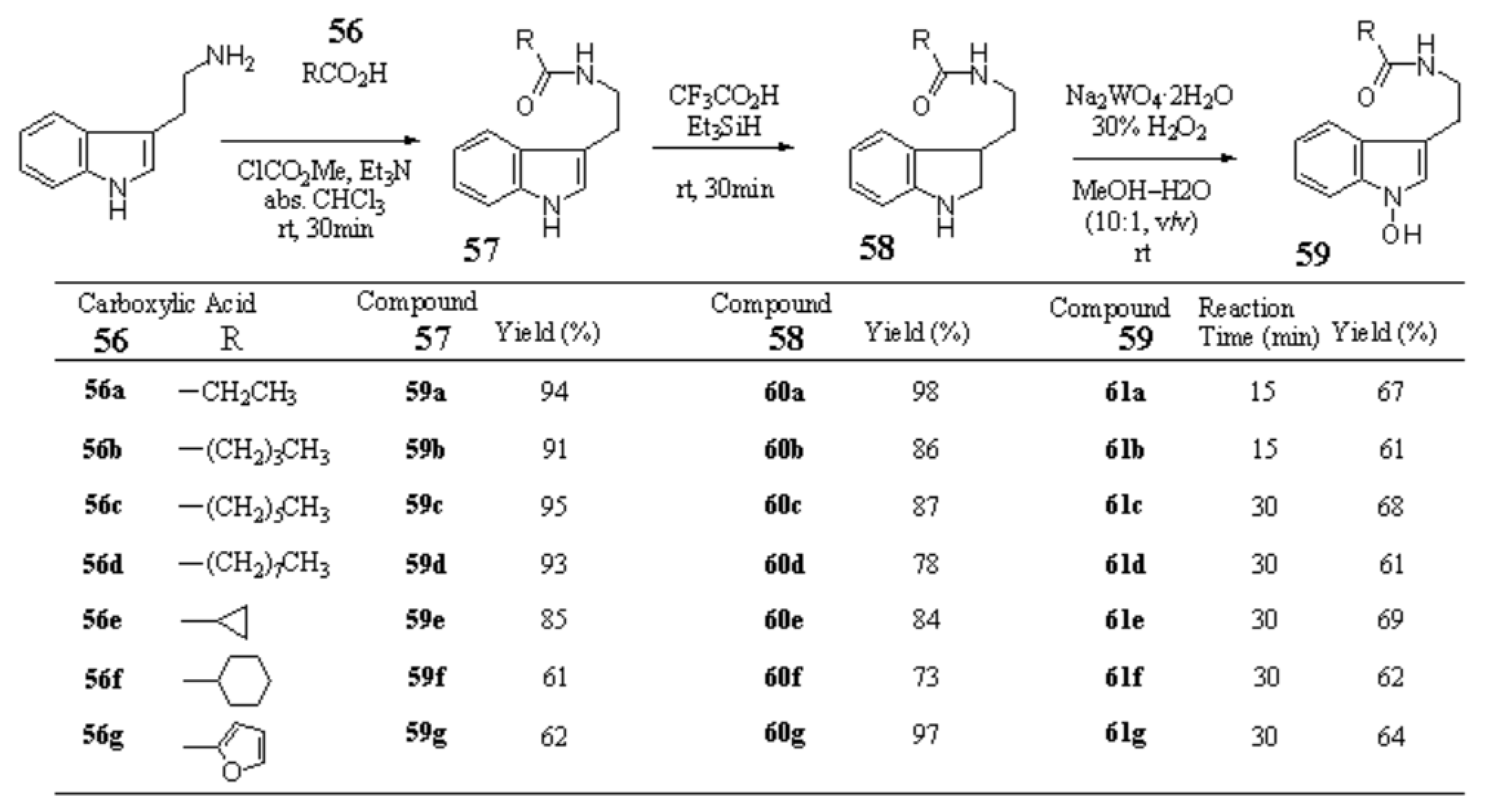

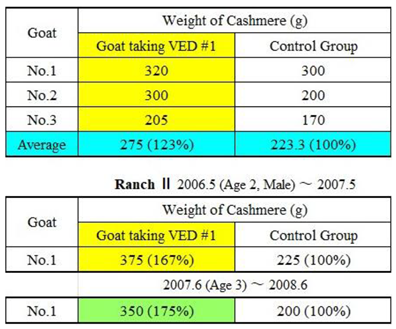

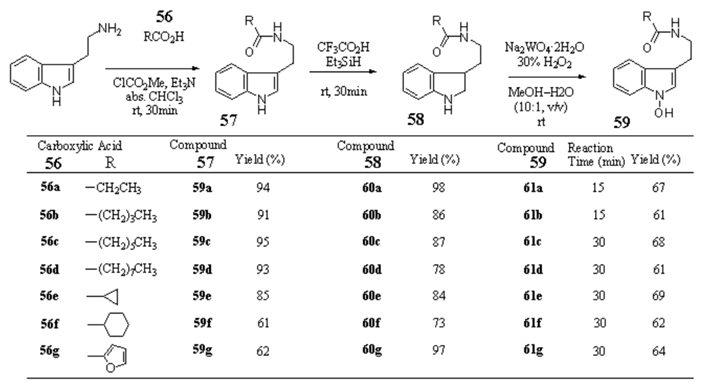

23-2. Synthesis of VED and related derivatives through 1-hydroxy tryptamines

Scheme 5 Synthesis of 1-hydroxy-Nb-acyltryptamines

Nb-Propionyl tryptamine (57a) from tryptamine — Et3N (1.89 mL, 13.6 mmol) and ClCO2Me (1.05 mL, 1.36 mmol) were added to a solution of propionic acid (913 mg, 12.3 mmol) in anhydrous CHCl3 (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. To the resulting mixture, tryptamine (2.17 g, 13.6 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at rt for 30 min. After addition of H2O the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a residue, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give 57a (2.51g, 94%). 57a: mp 88–89 °C (colorless fine needles, recrystallized from Et2O). IR (KBr): 3377, 1635, 1563, 1453, 1368, 1250 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.11 (3H, t, J=7.0 Hz), 2.14 (2H, q, J=7.6 Hz), 2.98 (2H, dt, J=6.6, 0.7 Hz), 3.61 (2H, q, J=6.6 Hz), 5.50 (1H, br s), 7.04 (1H, d, J=2.2 Hz), 7.13 (1H, ddd, J=7.8, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.21 (1H, ddd, J=7.8, 7.1, 1.2 Hz) 7.37 (1H, dt, J=7.8, 1.0 Hz), 7.61 (1H, ddd, J=7.8, 1.2, 0.7 Hz), 8.09 (1H, br s). MS m/z: 216 (M+). Anal. Calcd. For C13H16N2O·1/8H2O: C, 71.45; H, 7.50; N, 12.82. Found: C, 71.77; H, 7.34; N, 12.52.

Nb-Valeryl tryptamine (57b) from tryptamine — Et3N (1.57 mL, 11.3 mmol) and ClCO2Me (0.87 mL, 11.3 mmol) were added to a solution of valeric acid (1.05 g, 10.3 mmol) in anhydrous CHCl3 (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. To the resulting mixture, tryptamine (1.81 g, 11.3 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at rt for 30 min. After addition of H2O the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a residue, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (2:3, v/v) to give 57b (2.29g, 91%). 57b: mp 93–94 °C (colorless powder, recrystallized from AcOEt–hexane). IR (KBr): 3377, 3237, 2927, 1630, 1561, 1450 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.88 (3H, t, J=7.3 Hz), 1.26–1.34 (2H, m), 1.53–1.60 (2H, m), 2.11 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 2.98 (2H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 3.61 (2H, q, J=6.6 Hz), 5.56 (1H, br s), 7.04 (1H, s), 7.13 (1H, ddd, J=7.9, 7.0, 0.9 Hz), 7.22 (1H, ddd, J=7.9, 7.0, 0.9 Hz), 7.38 (1H, dt, J=7.9 Hz), 7.61 (1H, d, J=7.9 Hz), 8.09 (1H, br s). Anal. Calcd. For C15H20N2O: C, 73.73; H, 8.25; N, 11.47. Found: C, 73.48; H, 8.23; N, 11.42.

Nb-Heptanoyl tryptamine (57c) from tryptamine — Et3N (1.19 mL, 8.58 mmol) and ClCO2Me (0.66 mL, 8.58 mmol) were added to a solution of heptanoic acid (1.01 g, 7.80 mmol) in anhydrous CHCl3 (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. To the resulting mixture, tryptamine (1.37 g, 8.58 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at rt for 30 min. After addition of H2O the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a residue, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3 to give 57c (2.02 g, 95%). 57c: mp 97–98 °C (colorless powder, recrystallized from AcOEt–hexane). IR (KBr): 3410, 1632, 1565, 1457, 1425 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.87 (3H, t, J=7.3 Hz), 1.21–1.31 (6H, m), 1.57 (2H, quint, J=7.5 Hz), 2.10 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 2.98 (2H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 3.61 (2H, q, J =6.6 Hz), 5.52 (1H, br s), 7.04 (1H, d, J=2.2 Hz), 7.13 (1H, ddd, J= 8.1, 7.0, 1.0 Hz), 7.22 (1H, ddd, J= 8.1, 7.0, 1.0 Hz, 7.38 (1H, dt, J=8.1, 1.0 Hz) 7.61 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 8.08 (1H, br s). Anal. Calcd. For C17H24N2O: C, 74.96; H, 8.88; N, 10.29. Found: C, 74.80; H, 8.92; N, 10.26.

VED #1 [Nb-Nonanoyl tryptamine (57d)] from tryptamine — Et3N (0.99 mL, 7.09 mmol) and ClCO2Me (0.55 mL, 7.09 mmol) were added to a solution of nonanoic acid (1.02g, 6.45 mmol) in anhydrous CHCl3 (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. To the resulting mixture, tryptamine (1.14 g, 7.09 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at rt for 30 min. After addition of H2O the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave a residue, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:2, v/v) to give 57d (1.78g, 93%). 57d: mp 101–102 °C (colorless fine needles, recrystallized from CHCl3–hexane). IR (CHCl3): 2950, 1652, 1506, 1165 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.87 (3H, t, J=7.0 Hz), 1.22–1.31 (10H, m), 1.57 (2H, br quint, J=7.0 Hz), 2.10 (2H, t, J=7.6 Hz), 2.98 (2H, t, J=6.7 Hz), 3.61 (2H, q, J=6.7 Hz, collapsed to t , J=6.7 Hz on addition of D2O), 5.52 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 7.04 (1H, s), 7.13 (1H, ddd, J=8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.21 (1H, ddd, J=8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.38 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 7.61 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 8.09 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C19H28N2O: C, 75.96; H, 9.39; N, 9.33. Found: C, 75.66; H, 9.49; N, 9.24.

2,3-Dihydro-Nb-propionyltryptamine (58a) from 57a — A mixture of 57a (1.02 g, 4.74 mmol) and Et3SiH (1.89 mL, 11.9 mmol) in TFA (20 mL) was stirred at rt for 30 min. After evaporation of the solvent, the residue was made alkaline with 8% NaOH and extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH–28%NH4H (46:1:0.1, v/v) to give 58a (1.01 g, 98%). 58a: yellow viscous oil. IR (film): 3315, 2970, 1635, 1606, 1547, 1486, 1461 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.13 (3H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 1.78 (1H, dtd, J=13.6, 7.9, 6.0 Hz), 2.00 (1H, dddd, J=13.6, 7.9, 7.0, 5.0 Hz), 2.16 (2H, q, J=7.5 Hz), 2.82(1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 3.26–3.42 (4H, m), 3.72 (1H, t, J=8.8 Hz), 5.62 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 6.67 (1H, d, J=7.3 Hz), 6.75 (1H, td, J=7.3, 0.9 Hz), 7.05 (1H, br t, J=7.3 Hz), 7.10 (1H, d, J=7.3 Hz). HR–MS m/z: Calcd for C13H18N2O: 218.1419. Found: 218.1431.

2,3-Dihydro-Nb-valeryltryptamine (58b) from 57b — A mixture of 57b (102.1 mg, 0.42 mmol) and Et3SiH (0.17 mL, 1.05 mmol) in TFA (3.0 mL) was stirred at rt for 30 min. After evaporation of the solvent, the residue was made alkaline with 8% NaOH and extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH–28%NH4H (46:1:0.1, v/v) to give 58b (88.1 mg, 86%). 58b: yellow viscous oil. IR (film): 3290, 2930, 1640, 1605, 1552, 1484, 1461 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.91 (3H, t, J= 7.5 Hz), 1.33 (2H, sext, J=7.5 Hz), 1.59 (2H, quint, J=7.5 Hz), 1.73 (1H, dtd, J=13.6, 8.0, 6.1 Hz), 1.99 (1H, dddd, J=13.6, 8.0, 7.0, 5.0 Hz), 2.13 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 2.75 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 3.27–3.42 (4H, m), 3.72 (1H, t, J=8.6 Hz), 5.60 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 6.68 (1H, d, J=7.3 Hz), 6.75 (1H, td, J=7.3, 0.9 Hz), 7.05 (1H, br t, J=7.3 Hz), 7.11 (1H, d, J=7.3 Hz). HR–MS m/z: Calcd for C15H22N2O: 246.1732. Found: 246.1743.

Nb-Heptanoyl-2,3-dihydrotryptamine (58c) from 57c — A mixture of 57c (1.04 g, 3.82 mmol) and Et3SiH (1.52 mL, 9.54 mmol) in TFA (20 mL) was stirred at rt for 30 min. After evaporation of the solvent, the residue was made alkaline with 8% NaOH and extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (2:1, v/v) to give 58c (912.7 mg, 87%). 58c: pale yellow viscous oil. IR (film): 3310, 2960, 1634, 1606, 1544, 1484, 1461 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.88 (3H, t, J= 7.5 Hz), 1.25–1.34 (6H, m), 1.60 (2H, quint, J=7.5 Hz), 1.78 (1H, dtd, J=13.6, 7.9, 5.9 Hz), 1.99 (1H, dddd, J=13.6, 7.9, 7.1, 5.1 Hz), 2.12 (2H, t, J=7.7 Hz), 2.68 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 3.27–3.42 (4H, m), 3.72 (1H, t, J=8.6 Hz), 5.60 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 6.68 (1H, d, J=7.5 Hz), 6.75 (1H, td, J=7.5, 1.1 Hz), 7.05 (1H, br t, J=7.5 Hz), 7.10 (1H, d, J=7.5 Hz). HR–MS m/z: Calcd for C17H26N2O: 274.2045. Found: 274.2057.

2,3-Dihydro-Nb-nonanoyltryptamine (58d) from 57d — A mixture of 57d (1.10 g, 3.65 mmol) and Et3SiH (1.45 mL, 9.10 mmol) in TFA (20 mL) was stirred at rt for 30 min. After evaporation of the solvent, the residue was made alkaline with 8% NaOH and extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give 58d (862.4 mg, 78%). 58d: mp 41–42.5 °C (colorless powder, recrystallized from AcOEt–hexane). IR (KBr): 3300, 2935, 2870, 1638, 1546, 1486, 1465 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.84 (3H, t, J=7.0 Hz), 1.20–1.27 (10H, m), 1.45–1.57 (3H, m). 1.83 (1H, dtd, J=13.2, 7.6, 5.6 Hz), 2.04 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 3.05 (1H, ddd, J=9.3, 8.1, 2.2 Hz), 3.09–3.16 (3H, m), 3.54 (1H, td, J=8.6, 1.7 Hz), 5.40 (1H, br s, disappeared on addition of D2O), 6.47 (1H, d, J=7.5 Hz), 6.52 (1H, td, J= 7.5, 0.7 Hz), 6.90 (1H, br t, J=7.5 Hz), 7.00 (1H, d, J=7.5 Hz), 7.80 (1H, br t, J= 6.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C19H30N2O: C, 75.45; H, 10.00; N, 9.26. Found: C, 75.25; H,10.16; N, 9.24.

1-Hydroxy-Nb-propionyltryptamine (59a) from 58a — A solution of 30% H2O2 (1.11 g, 9.80 mmol) in MeOH (3.0 mL) was added to a solution of 58a (211.8 mg, 0.97 mmol) and Na2WO4·2H2O (64.1 mg, 0.19 mmol) in MeOH (7.0 mL) and H2O (1.0 mL) under ice cooling with stirring. Stirring was continued at rt for 15 min. After addition of H2O, the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH (99:1, v/v) to give 59a (150.2 mg, 67%). 59a: mp 132–133 °C (colorless fine prisms, recrystallized from CHCl3). IR (KBr): 3290, 3100, 2935, 1598, 1566, 1352 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.99 (3H, t, J=7.6 Hz), 2.06 (2H, q, J=7.6 Hz), 2.79 (2H, t, J=7.3 Hz), 3.30 (2H, td, J=7.3, 6.1 Hz, collapsed to t, J=7.3 Hz, on addition of D2O), 6.98 (1H, dd, J=8.0, 7.3 Hz), 7.13 (1H,dd, J=8.0, 7.3 Hz), 7.24 (1H, s), 7.32 (1H, d, J=8.0 Hz), 7.53 (1H, d, J=8.0 Hz), 7.84 (1H, br t, J=6.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 11.01 (1H, s, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C13H16N2O2: C, 67.22; H, 6.94; N, 12.06. Found: C, 66.94; H, 6.95; N, 12.02.

1-Hydroxy-Nb-valeryltryptamine (59b) from 58b — A solution of 30% H2O2 (2.37 g, 20.9 mmol) in MeOH (5.0 mL) was added to a solution of 58b (513.3 mg, 2.09 mmol) and Na2WO4·2H2O (138.0 mg, 0.42 mmol) in MeOH (20 mL) and H2O (2.5 mL) under ice cooling with stirring. Stirring was continued at rt for 15 min. After addition of H2O, the whole was extracted with CHCl3. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (1:1, v/v) to give 59b (331.2 mg, 61%). 59b: mp 114.5–115 °C (colorless powder, recrystallized from CHCl3). IR (CHCl3): 3125, 2922, 1649, 1513 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.86 (3H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 1.25 (2H, sext, J=7.4 Hz), 1.47 (2H, quint, J=7.4 Hz), 2.05 (2H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 2.78 (2H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 3,30 (2H, td, J=7.4, 6.1 Hz, collapsed to t, J=7.4 Hz, on addition of D2O), 6.98 (1H, ddd, J=8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.12 (1H, ddd, J=8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.23(1H, s), 7.32 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 7.53 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 7.86 (1H, br t, J=6.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 11.00 (1H, s, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C15H20N2O2: C, 69.20; H, 7.74; N, 10.76. Found: C, 69.17; H, 7.70; N, 10.68.

1-Hydroxy-Nb-heptanoyltryptamine (59c) from 58c — A solution of 30% H2O2 (461 4 mg, 4.07 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) was added to a solution of 58c (111.3 mg, 0.41 mmol) and Na2WO4·2H2O (27.3 mg, 0.08 mmol) in MeOH (4.0 mL) and H2O (0.5 mL) under ice cooling with stirring. Stirring was continued at rt for 30 min. After addition of H2O, the whole was extracted with CHCl3–MeOH (95:5, v/v). The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with AcOEt–hexane (2:1, v/v) to give 59c (79.8 mg, 68%). 59c: mp 83–83.5 °C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from CHCl3–hexane). IR (KBr): 3280, 2930, 1601, 1555, 1435, 1358, 1241 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.86 (3H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 1.21–1.29 (6H, m), 1.47 (2H, quint., J=7.5 Hz), 2.04 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 2.78 (2H, t, J=7.5 Hz), 3.29 (2H, td, J=7.5, 6.1 Hz, collapsed to t, J=7.5 Hz, on addition of D2O), 6.98 (1H, ddd, J= 8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.12(1H, ddd, J=8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.24 (1H, s), 7.32 (1H, dt, J=8.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.52 (1H, dt, J=8.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.86 (1H, br t, J=6.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 11.00 (1H, s, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C17H24N2O2: C, 70.80; H, 8.39; N, 9.71. Found: C, 70.73; H, 8.40; N, 9.64.

1-Hydroxy-Nb-nonanyltryptamine (59d) from 58d — A solution of 30% H2O2 (451.3 mg, 3.98 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) was added to a solution of 58d (119.3 mg, 0.40 mmol) and Na2WO4·2H2O (26.7 mg, 0.08 mmol) in MeOH (4.0 mL) and H2O (0.5 mL) under ice cooling with stirring. Stirring was continued at rt for 30 min. After addition of H2O, the whole was extracted with AcOEt. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave an oil, which was column-chromatographed on SiO2 with CHCl3–MeOH (99:1, v/v) to give 59d (75.8 mg, 61%). 59d: mp 82.5–83 °C (colorless powder, recrystallized from CHCl3–hexane). IR (CHCl3): 3155, 2915, 1648, 1510, 1457 cm-1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 0.86 (3H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 1.15–1.30 (10H, m), 1.47 (2H, quint., J=7.4 Hz), 2.03 (2H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 2.78 (2H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 3.30 (2H, td, J=7.4, 6.1 Hz, collapsed to t, J=7.4 Hz, on addition of D2O), 6.98 (1H, ddd, J= 8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz),7.12(1H, ddd, J=8.1, 7.1, 1.0 Hz), 7.24 (1H, s), 7.32 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 7.52 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 7.86 (1H, br t, J=6.1 Hz, disappeared on addition of D2O), 11.01 (1H, s, disappeared on addition of D2O). Anal. Calcd for C19H28N2O2: C, 72.11; H, 8.92; N, 8.85. Found: C, 72.09; H, 8.96; N, 8.85.

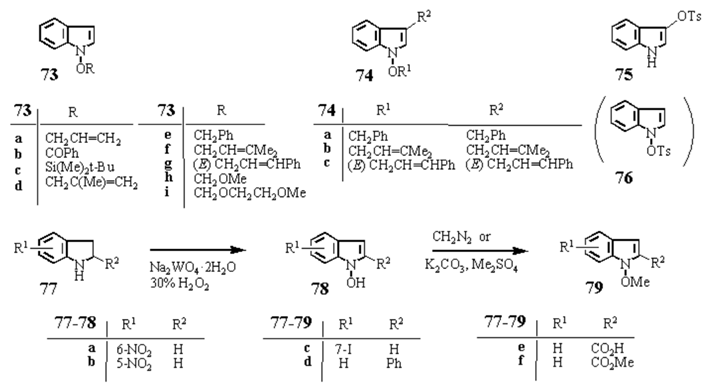

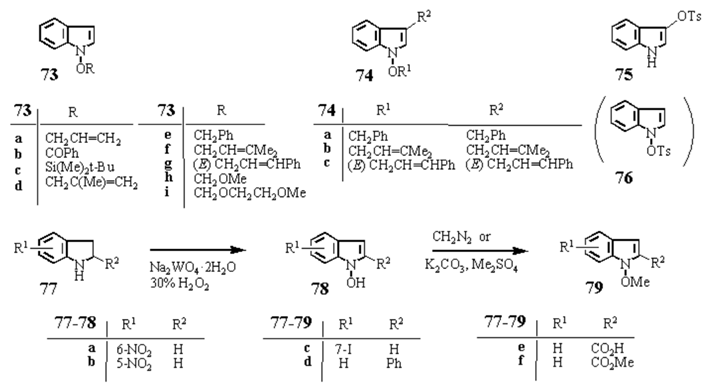

1-Allyloxyindole (73a) from (3) — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (611.6 mg, 1.85 mmol) in H2O (10.0 mL) was added to a solution of 3 (1.108 g, 9.29 mmol) in MeOH (20.0 mL). 30% H2O2 (10.561 g, 101.2 mmol) in MeOH (20.0 mL) was added to the resultant solution at 0 °C with stirring. After stirring for 15 min at rt (20 °C), K2CO3 (3.86 g, 27.8 mmol) and allyl bromide (3.313 g, 27.4 mmol) were added and stirred at rt for 1.5 h. Brine was added and the whole was extracted with CH2Cl2. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave oil, which was purified by column-chromatography on SiO2 with CH2Cl2–hexane (1:9, v/v) to give 73a (711.3 mg, 44%). 73a: colorless oil. IR (film): 3050, 1449, 1220, 740 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.67 (2H, dt, J=6.6, 1.2 Hz), 5.21 (1H, m), 5.35 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 5.86–6.25 (1H, m), 6.30 (1H, dd, J=3.5, 1.0 Hz), 6.94–7.61 (5H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C11H11NO: 173.0782. Found: 173.0811.

Scheme 7 Synthesis of 1-hydroxyindole derivatives (1)

1-Benzoyloxyindole (73b) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for

6, where Na

2WO

4·2H

2O (57.1 mg, 0.17 mmol) in H

2O (1.0 mL),

3 (103.0 mg, 0.86 mmol) in MeOH (8.0 mL), and 30% H

2O

2 (981.2 mg, 8.66 mmol) in MeOH (2.0 mL) were used. The reaction mixture was extracted with benzene and benzene layer was dried over Na

2SO

4. After filtering off Na

2SO

4, K

2CO

3 (583.3 mg, 3.89 mmol) and benzoyl chloride (483.2 mg, 2.59 mmol) were added to the benzene solution and stirred at rt for 1.5 h. H

2O was added and the whole was extracted with CH

2Cl

2. The extract was washed with brine, dried over Na

2SO

4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to leave oil, which was purified by column-chromatography on SiO

2 with CH

2Cl

2–hexane (3:7, v/v) to give

73b (100.8 mg, 49%).

73b: mp 55.5–56.0 °C (lit.[

64] mp 49–50 °C, pale brown needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 1767, 1600, 1446, 1323, 1236, 1184, 1075, 1039, 1012, 1002, 754, 729, 700 cm

-1. UV λ

maxMeOH nm (log ε): 217 (4.50), 265 (3.94), 293 (3.60).

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 6.53 (1H, d,

J=3.7 Hz), 6.96–7.35 (4H, m), 7.35–7.82 (4H, m), 8.21 (2H, dd,

J=8.2, 1.7 Hz). MS

m/z: 237 (M

+).

Anal. Calcd for C

15H

11NO

2: C, 75.94; H, 4.67; N, 5.90. Found: C, 75.85; H, 4.62; N, 5.84.

1-t-Butyldimethylsilyloxyindole (73c) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (75.9 mg, 0.23 mmol) in H2O (1.3 mL), 3 (136.9 mg, 1.15 mmol) in MeOH (10.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (1.304 g, 11.5 mmol) in MeOH (3.0 mL) were used. Silylation was carried out according to the method for 73b with K2CO3 (715.5 mg, 5.18 mmol) and t-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (520.2 mg, 3.45 mmol). After usual work-up and purification, 73c (133.1 mg, 47%) was obtained. 73c: colorless oil. IR (film): 1472, 1436, 1266, 1074, 1035, 836, 787, 739 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 0.23 (6H, s), 1.10 (9H, s), 6.31 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 7.01 (1H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 7.07 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 7.17 (1H, t, J=6.6 Hz), 7.31 (1H, d, J=6.6 Hz), 7.53 (1H, d, J=6.6 Hz). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C14H21NOSi: 247.1390. Found: 247.1376.

1-Methallyloxyindole (73d) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (26.7 mg, 0.08 mmol) in H2O (0.5 mL), 3 (48.0 mg, 0.40 mmol) in MeOH (4.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (461.7 mg, 4.0 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) were used. Methallylation was carried out with K2CO3 (253.3 mg, 1.80 mmol) and methallyl chloride (110.5 mg, 1.20 mmol). After usual work-up and purification, 73d (4.2 mg, 6%) was obtained. 73d: colorless oil. IR (film): 1653, 1450, 1323, 1222, 740 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.97 (3H, t, J=1.2 Hz), 4.60 (2H, s), 5.03 (2H, m), 6.32 (1H, dd, J=3.4, 0.7 Hz), 7.00–7.63 (5H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C12H13NO: 187.0972. Found: 187.0984.

1-Benzyloxyindole (73e) and 3-benzyl-1-benzyloxyindole (74a) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (60.3 mg, 0.18 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL), 3 (108.7 mg, 0.91 mmol) in MeOH (8.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (1.036 g, 9.13 mmol) in MeOH (2.0 mL) were used. Benzylation was carried out with K2CO3 (568.1 mg, 4.11 mmol) and benzyl bromide (483.2 mg, 2.74 mmol). After usual work-up and purification, 73e (96.0 mg, 47%) and 74a (14.7 mg, 5%) were obtained. 73e: colorless oil. IR (film): 1455, 1323, 1221, 1074, 1032, 756, 740, 697 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 5.15 (2H, s), 6.23 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 6.98 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 6.98–7.22 (2H, m), 7.22–7.44 (6H, m), 7.44–7.60 (1H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C15H13NO: 223.0996. Found: 223.0992. 74a: colorless oil. IR (KBr, film): 1494, 1450, 734, 695 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.00 (2H, s), 5.12 (2H, s), 6.11 (1H, s), 6.85–7.11 (14H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C22H15NO: 313.1465. Found: 313.1468.

1-Prenyloxyindole (73f) and 3-prenyl-1-prenyloxyindole (74b) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (61.9 mg, 0.19 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL), 3 (111.2 mg, 0.93 mmol) in MeOH (8.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (1.087 g, 10.1 mmol) in MeOH (2.0 mL) were used. Prenylation was carried out with K2CO3 (470.6 mg, 6.84 mmol) and prenyl bromide (380.2 mg, 0.51 mmol). After usual work-up and purification 73f (13.5 mg, 7%) and 74b (9.3 mg, 4%) were obtained. 73f: pale yellow oil. IR (film): 3050, 2980, 2930, 1670, 1450, 1324, 1222, 1075, 1030, 740 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.48 (3H, s), 1.68 (3H, s), 4.54 (2H, d, J=7.9 Hz), 5.44 (1H, t, J=7.2 Hz), 6.21 (1H, dd, 3.6, 1.0 Hz), 6.88–7.50 (5H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C13H15NO: 201.1153. Found: 201.1155. 74b: pale red oil. IR (film): 2980, 2920, 1666, 1612, 1447, 1375, 1088, 1008, 735 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 1.58 (3H, s), 1.74 (3H, s), 1.76 (6H, s), 3.38 (2H, dd, J=7.0, 1.0 Hz), 4.60 (2H, d, J=7.5 Hz), 5.28–5.61 (2H, m), 6.94–7.56 (5H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C18H23NO: 269.1753. Found: 269.1765.

1-Prenyloxyindole (73f) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (65.2 mg, 0.19 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL), 3 (116.4 mg, 0.98 mmol) in MeOH (9.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (1.143 g, 10.0 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) were used. Prenylation was carried out with NEt3 (1.4 mL, 9.8 mmol), (n-Bu)4NBr (32.3 mg, 0.10 mmol), and prenyl bromide (1.339 g, 8.71 mmol). After usual work-up and purification,73f (35.7 mg, 18%) was obtained.

1-Prenyloxyindole (73f) from 73c — A solution of prenyl bromide (112.2 mg, 0.72 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL), KOt-Bu (91.7 mg, 0.82 mmol), and a solution of (n-Bu)4NF·3H2O (120.6 mg, 0.34 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL) were added to a solution of 73c (75.4 mg, 0.37 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL) at rt. After usual work-up and purification, 73f (75.4 mg, 100%) was obtained.

1-Cinnamyloxyindole (73g) and 3-cinnamyl-1-cinnanyloxyindole (74c) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (57.9 mg, 0.17 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL). 3 (104.1 mg, 0.87 mmol) in MeOH (8.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (991.9 mg, 8.7 mmol) in MeOH (2.0 mL) were used. Cinnamylation was carried out with K2CO3 (544.6 mg, 3.91 mmol) and cinnamyl bromide (520.8 mg, 2.61 mmol). After usual work-up and purification, 73g (110.5 mg, 51%) and 74c (80.2 mg, 22%) were obtained. 73g: pale brown oil. IR (film): 3050, 3017, 2920, 1495, 1449, 1323, 1221, 1074, 1030, 965, 757, 738, 691 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.81 (2H, d, J=6.0 Hz), 6.31 (1H, dd, J=3.5, 1.0 Hz), 6.25–6.72 (2H, m), 6.96–7.60 (10H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C17H15NO: 249.1148. Found: 249.1150. 74c: pale yellow oil. IR (film): 3050, 3017, 2920, 1496, 1449, 964, 738, 692 cm–1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 3.58 (2H, dd, J=5.3, 1.0 Hz), 4.77 (2H, d, J=5.5 Hz), 6.13–6.72 (4H, m), 6.93–7.61 (15H, m). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C26H23NO: 365.1800. Found: 365.1789.

1-Methoxymethoxyindole (73h) from 3— Prepared according to the general method C for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (63.7 mg, 0.19 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL), 3 (115.1 mg, 0.96 mmol) in MeOH (10.0 mL), and urea·H2O2 compound (927.2 mg, 9.66 mmol) were used. Methoxymethylation was carried out with K2CO3 (2.403 g, 17.38 mmol), (n-Bu)4NBr (31.1 mg, 0.09 mmol), and methoxymethyl chloride (233.3 mg, 2.89 mmol) in benzene (1.0 mL). After usual work-up and purification, 73h (66.0 mg, 39%) was obtained. 73h: mp 27.0–27.5 °C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from hexane). IR (KBr): 2970, 1445, 1330, 1230, 1182, 1100, 1089, 1030, 920, 740 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 3.66 (3H, s), 5.17 (2H, s), 6.37 (1H, d, J=3.5 Hz), 7.11 (1H, t, J=7.4 Hz), 7.20–7.26 (3H, m), 7.42 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz), 7.58 (1H, d, J=7.9 Hz). MS m/z: 177 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C10H11NO2: C, 67.78; H, 6.26; N, 7.90. Found: C, 67.64; H, 6.33; N, 7.86.

1-Methoxymethoxyindole (73h) from 73c — A solution of methoxymethyl chloride (56.2 mg, 0.69 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL), KOt-Bu (91.2 mg, 0.81 mmol), and a solution of (n-Bu)4NF·3H2O (111.1 mg, 0.35 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL) were added to a solution of 73c (85.4 mg, 0.34 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL) at rt. After usual work-up and purification, 73h (59.7 mg, 98%) was obtained.

1-(2-Methoxyethoxymethoxy)indole (73i) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (61.4 mg, 0.19 mmol) in H2O (1.0 mL), 3 (111.1 mg, 0.93 mmol) in MeOH (9.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (1.073 g, 9.46 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) were used. Methoxyethoxymethylation was carried out with NEt3 (2.6 mL, 18.6 mmol), (n-Bu)4NBr (29.9 mg, 0.09 mmol), and 2-methoxyethoxymethyl chloride (1.038 g, 8.35 mmol). After usual work-up and purification, 73i (23.2 mg, 11%) and indole (2.2 mg, 2%) were obtained. 73i: colorless oil. IR (KBr): 2920, 2890, 1450, 1320, 1220, 1105, 1030, 920, 875, 845, 760, 740 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 3.41 (3H, s), 3.59–3.65 (2H, m), 3.93–3.99 (2H, m), 5.27 (2H, s), 6.36 (1H, dd, J=3.5, 1.0 Hz), 7.10 (1H, ddd, J=7.9, 6.9, 1.0 Hz), 7.22 (1H, ddd, J=8.3, 6.9, 1.0 Hz), 7.33 (1H, d, J=3.5 Hz), 7.42 (1H, dd, J=8.3, 1.0 Hz), 7.58 (1H, ddd, J=7.9, 1.0, 1.01 Hz). High resolution MS m/z: Calcd for C12H15NO3: 221.1050. Found: 221.1049.

1-(2-Methoxyethoxymethoxy)indole (73i) from 73c — A solution of 2-methoxyethoxymethyl chloride (98.8 mg, 0.79 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL), KOt-Bu (97.2 mg, 0.86 mmol), and a solution of (n-Bu)4NF·3H2O (125.8 mg, 0.39 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL) were added to a solution of 73c (94.9 mg, 0.38 mmol) in anhydrous THF (1.0 mL) at rt. After usual work-up and purification, 73i (83.3 mg, 98%) was obtained.

3-Tosyloxyindole (75) from 3 — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (559.6 mg, 1.69 mmol) in H2O (10.0 mL), 3 (1.009 g, 8.48 mmol) in MeOH (80.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (9.610 g, 84.8 mmol) in MeOH (20.0 mL) were used. Tosylation was carried out with K2CO3 (5.270 g, 38.2 mmol) and tosyl chloride (4.848 g, 25.5 mmol). After usual work-up and purification, 75 (252.2 mg, 10%) was obtained. 75: mp 112–114°C (colorless prisms, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 3390, 3120, 1595, 1453, 1370, 1190, 1175, 1090, 1063, 843, 812, 742, 723, 657, 555, 545, 503 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 2.41 (3H, s), 6.95–7.30 (8H, m), 7.75 (2H, d, J=8.3 Hz). MS m/z: 287 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C15H13NO3S: C, 62.70; H, 4.56; N, 4.87. Found: C, 62.70; H, 4.53; N, 4.72. 76 was not isolated because of its instant instability to change to 75.

1-Hydroxy-6-nitroindole (78a) from 77a — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (18.8 mg, 0.06 mmol), 77a (101.3 mg, 0.57 mmol) in MeOH (10.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (0.58 mL, 5.7 mmol) were used. After usual work-up and purification,78a (80.1 mg, 79%) was obtained. 78a: mp 153–155 °C (decomp., pale orange needles, recrystallized from CHCl3). IR (KBr): 3240, 1617, 1586, 1514, 1481, 1357, 1332, 1280, 1095, 1056, 863, 811, 751, 731 cm-1. UV λmaxMeOH nm (log ε): 264 (4.01), 321 (3.94), 361 (3.73). 1H-NMR (CDCl3–CD3OD. 95:5, v/v) δ: 6.43 (1H, d, J=3.3 Hz), 7.51 (1H, d, J=3.3 Hz), 7.61 (H, d, J=8.8 Hz), 7.95 (1H, dd, J=8.8, 2.1 Hz), 8.42 (1H, dd, J=2.1 Hz). MS m/z: 178 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C8H6N2O3: C, 53.94; H, 3.39; N, 15.72. Found: C, 54.03; H, 3.45; N, 15.73.

1-Hydroxy-5-nitroindole (78b) from 77b — Prepared according to the general method B, where Na2WO4·2H2O (81.6 mg, 0.25 mmol) in H2O (2.0 mL), 77b (202.9 mg, 1.23 mmol) in MeOH (20.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (1.26 mL, 12.3 mmol) were used. After usual work-up and purification, 77b (52.7 mg, recovery, 26%), 5-nitroindole (9.4 mg, 5%), and 78b (91.7 mg, 42%) were obtained. The mixture of 78b and 5-nitroindoe was successfully separated by column chromatography on Al2O3 with benzene–EtOAc (10:1, v/v). 78b: mp 175–176 °C (decomp., brown needles, recrystallized from CHCl3). IR (KBr, film): 1613, 1584, 1508, 1358, 1339, 756, 720 cm-1. UV λmaxMeOH nm (log ε): 254 (4.07), 275 (4.20), 331 (3.81). 1H–NMR (CDCl3–CD3OD, 95:5, v/v) δ: 6.45 (H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 7.52 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 7.60 (1H, d, J=8.9 Hz), 7.98 (1H, dd, J=8.8, 2.2 Hz), 8.38 (1H, br s). MS m/z: 178 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C8H6N2O3: C, 53.94; H, 3.39; N, 15.72. Found: C, 53.66; H, 3.37; N, 15.71.

1-Hydroxy-2-phenylindole (78d) from 2,3-dihydro-2-phenylindole (77d) — Prepared according to the general method B for

6, where Na

2WO

4·2H

2O (17.4 mg, 0.053 mmol),

77d (51.5 mg, 0.26 mmol) in 4.0 mL of MeOH, and 30% H

2O

2 (299.4 mg, 2.64 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) were used. The crude product was purified by p-TLC on SiO

2 with CH

2Cl

2–MeOH (98:2, v/v) as a developing solvent to afford

78d (30.9 mg, 56%).

78d: mp 174.0–175.0 °C (decomp., pale yellow needles, recrystallized from CHCl

3, lit.,[

65] mp 175 °C). IR (KBr): 2400, 1625, 1370, 756, 740, 683 cm

-1.

1H-NMR (10% CD

3OD in CDCl

3) δ: 6.52 (1H, s, C3–H, deuterated during measuring), 6.88–7.62 (7H, m), 7.68–7.92 (2H, m). MS

m/z: 209 (M

+). Identical with the authentic sample prepared from benzoin oxime.[

66]

1-Methoxy-6-nitroindole (79a) from 2,3-dihydro-6-nitroindole (77a) — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (9.0 mg, 0.027 mmol), 77a (44.8 mg, 0.27 mmol) in MeOH (3.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (309.7 mg, 2.73 mmol) were used. After methylation, usual work-up, and purification, 79a (31.3 mg, 60%) and 6-nitroindole (3.8 mg, 9%) were obtained. 79a: mp 90.0–91.0 °C (yellow needles, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 1613, 1584, 1508, 1358, 1339, 756, 720 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.17 (3H, s), 6.45 (1H, dd, J=3.4 and 1.0 Hz), 7.52 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 7.60 (1H, d, J=8.8 Hz), 7.98 (1H, dd, J=8.8, 2.2 Hz), 8.38 (1H, br d, J=2.2 Hz). MS m/z: 192 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C9H8N2O3: C, 56.25; H, 4.20; N, 14.58. Found: C, 56.21; H, 4.17; N, 14.73.

1-Methoxy-5-nitroindole (79b) from 2,3-dihydro-5-nitroindole (77b) — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (16.4 mg, 0.05 mmol), 77b (40.8 mg, 0.29 mmol) in MeOH (3.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (282.0 mg, 2.48 mmol) in MeOH (2.0 mL) were used. After methylation, usual work-up, and purification, 79b (23.2 mg, 49%), unreacted starting material (17.1 mg, 42%), and 5-nitroindole (1.1 mg, 3%) were obtained. 79b: mp 89.5–90.5 °C (yellow plates, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 1615, 1580, 1512, 1324, 1066, 737 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.14 (3H, s), 6.54 (1H, dd, J=3.6, 0.8 Hz), 7.38 (1H, d, J=3.6 Hz), 7.44 (1H, d, J=9.0 Hz), 8.12 (1H, dd, J=9.0, 2.1 Hz), 8.54 (1H, d, J=2.1 Hz). MS m/z: 192 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C9H8N2O3: C, 56.25; H, 4.20; N, 14.58. Found: C, 56.25; H, 4.17; N, 14.50.

7-Iodo-1-methoxyindole (79c) from 2,3-dihydro-7-iodoindole (77c) — Prepared according to the general method B for 6, where Na2WO4·2H2O (14.7 mg, 0.045 mmol), 79c (218.7 mg, 0.89 mmol) in MeOH (5.0 mL), and 30% H2O2 (303.6 mg, 2.68 mmol) in MeOH (4.0 mL) were used. After usual work-up and purification, 79c (62.6 mg, 26%), 7-iodoindole (9.9 mg, 5%), and unreacted starting material (117.5 mg, 54%) were obtained. 79c: mp 35.0–35.5 °C (colorless plates, recrystallized from hexane). IR (KBr): 1544, 1333, 1276, 1033, 948, 775 cm-1. 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 4.08 (3H, s), 6.31 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 6.82 (1H, t, J=7.6 Hz), 7.29 (1H, d, J=3.4 Hz), 7.54 (1H, dd, J=7.6, 1.0 Hz), 7.68 (1H, dd, J=7.6, 1.0 Hz). MS m/z: 273 (M+). Anal. Calcd for C9H8INO: C, 39.59; H, 2.95; N, 5.12. Found: C, 39.53; H, 2.99; N, 5.13.

1-Methoxy-2-phenylindole (79d) —

a) From 2,3-dihydro-2-phenylindole (77d); prepared according to the general method B for

6, where Na

2WO

4·2H

2O (17.7 mg, 0.054 mmol),

77d (52.3 mg, 0.27 mmol) in MeOH (4.0 mL), and 30% H

2O

2 (304.1 mg, 2.68 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) were used. After usual work-up and purification,

79d (40.0 mg, 67%) and 2-phenylindole (3.9 mg, 8%) were obtained.

79d: mp 47.0–48.0 °C (lit.[

15] mp 49–51 °C, pale yellow plates, recrystallized from MeOH). IR (KBr): 1597, 956, 760, 741 cm

-1.

1H-NMR (CDCl

3) δ: 3.73 (3H, s), 6.56 (1H, s), 7.00–7.66 (7H, m), 7.73–7.91 (2H, m).

Anal. Calcd for C

15H

13NO: C, 80.69; H, 5.87; N, 6.27. Found: C, 80.77; H, 5.91; N, 6.04.

b) From 1-Hydroxy-2-phenylindole (78d): ethereal CH2N2 (excess) was added to a solution of 78d (30.9 mg, 0.15 mmol) in MeOH (3.0 mL) with stirring at rt until the starting material was not detected on tlc monitoring. The crude product was purified by p-TLC on SiO2 with EtOAc–hexane (1:4, v/v) as a developing solvent to afford 79d (28.3 mg, 86%).