Submitted:

19 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

1.1. Research questions

- (i)

- Is there a long or short run relationship between agriculture and economic growth?

- (ii)

- What policy recommendations and policy measures could help enhance agricultural sector productivity to further unlock its diversification potential and take advantage of regional and international economic integration?

1.2. Research objectives

1.3. Hypothesis

- H0: Agricultural sector growth does not have significant impact on economic growth in Angola; and

- Ha: Agricultural sector growth has significant impact on economic growth in Angola.

1.4. Significance of the research

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Generic studies

2.2. Specific African Economies

3. RESEARCH STRUCTURE AND METHODOLOGY

3.1. Data sources, estimation period and econometric tool

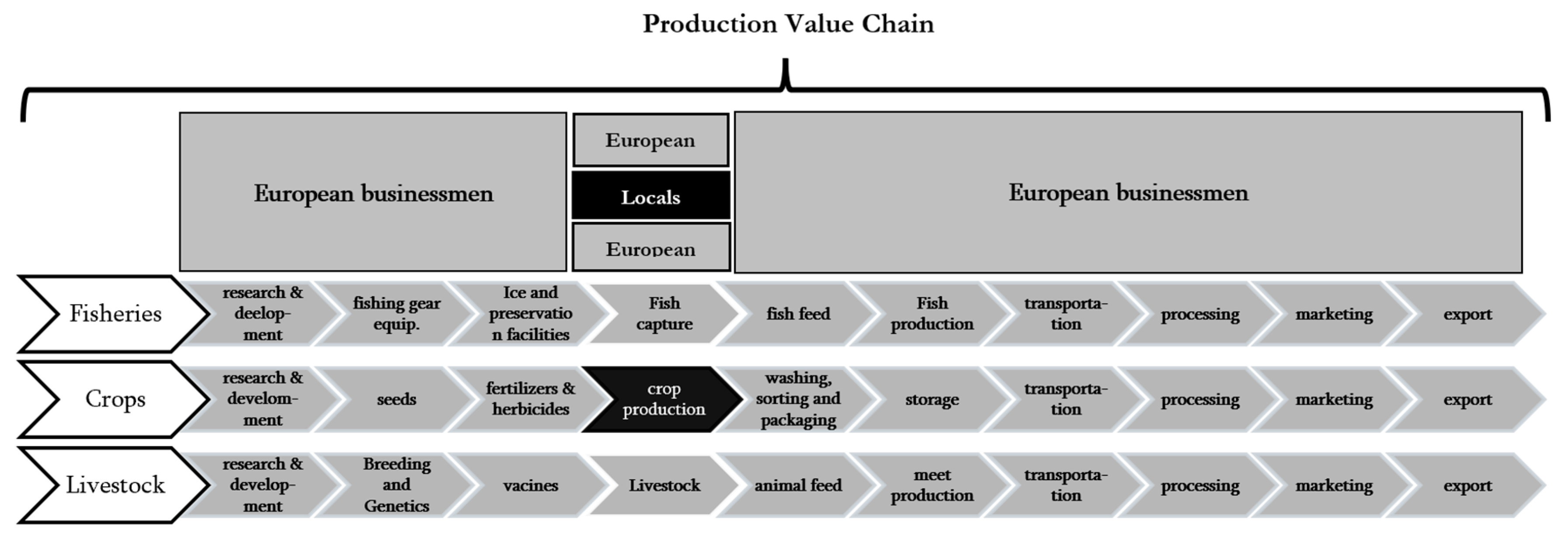

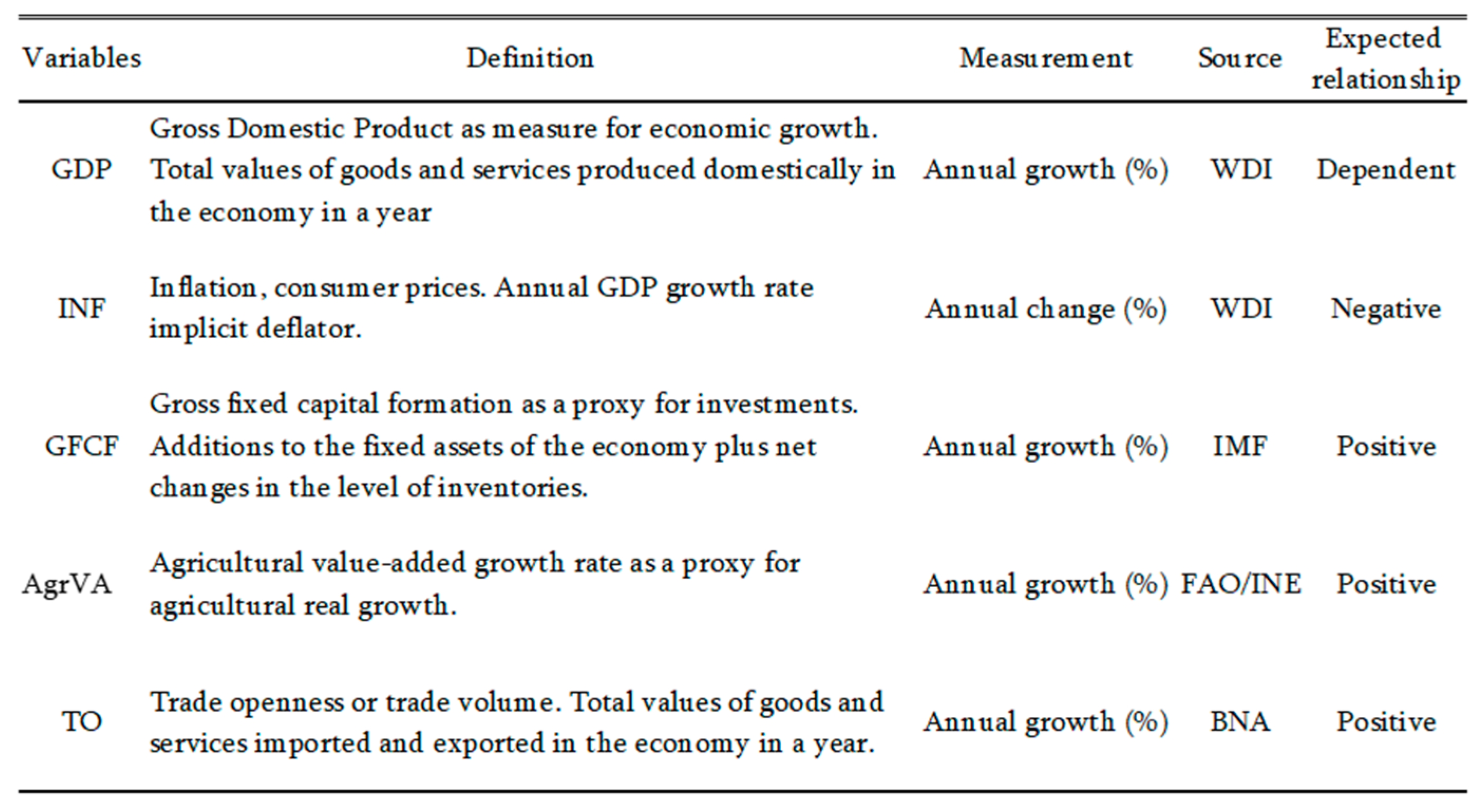

3.2. Determination of variables

3.3. Research methodology and model design

- (i)

- Conducting a unit root tests (ADF) to check the stationarity of each time series variable. For the test the basic equation applied involves estimating the following regression model (Nkoro & Uko, 2016, p. 72):

- (ii)

- selecting the optimal lag length for the ARDL model, using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and specifying the long-run ARDL model equation:

- (iii)

- estimating short-run relationship adding the error correction term, which is that of the long-term regression but lagged from a period;

- (iv)

- performing the bounds testing for cointegration and estimating the long-run relationship as well as the short-run dynamics using the error correction model (ECM);

- (v)

- Conducting a series of diagnostic tests to validate the model, namely

- a.

- Normality of residuals (Jarque-Bera test)

- b.

- Multicollinearity test

- c.

- Serial correlation test (Breusch-Godfrey LM test)

- d.

- Heteroscedasticity (Breusch-Pagan test)

- e.

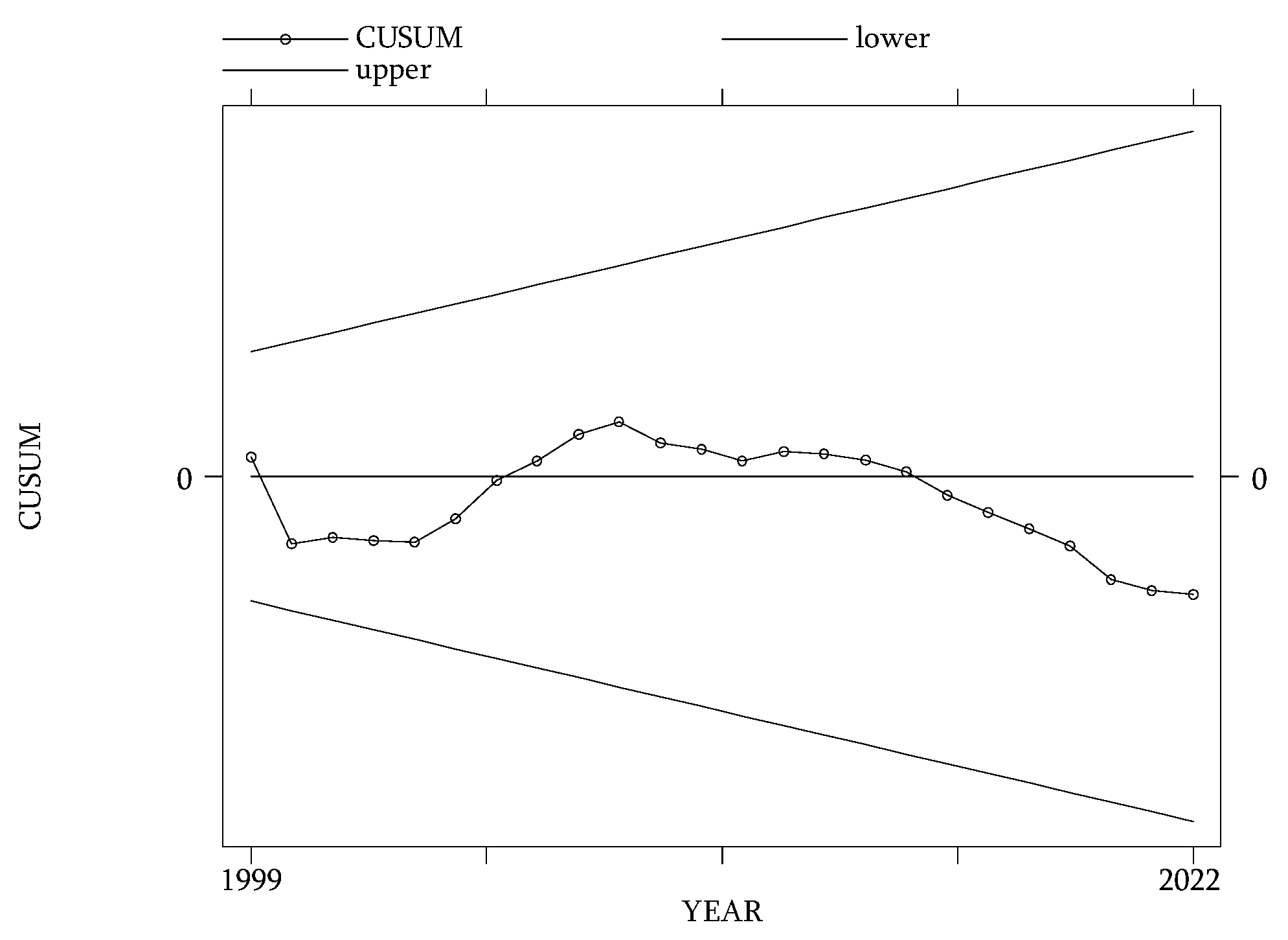

- Stability (CUSUM test)

- f.

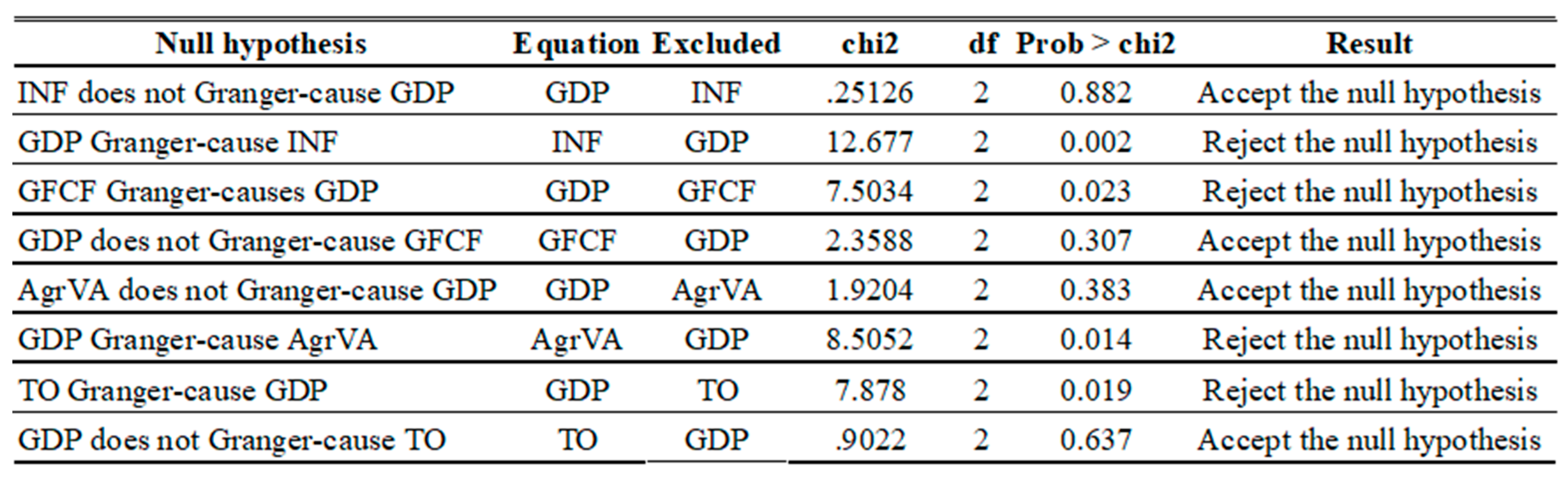

- Granger causality test

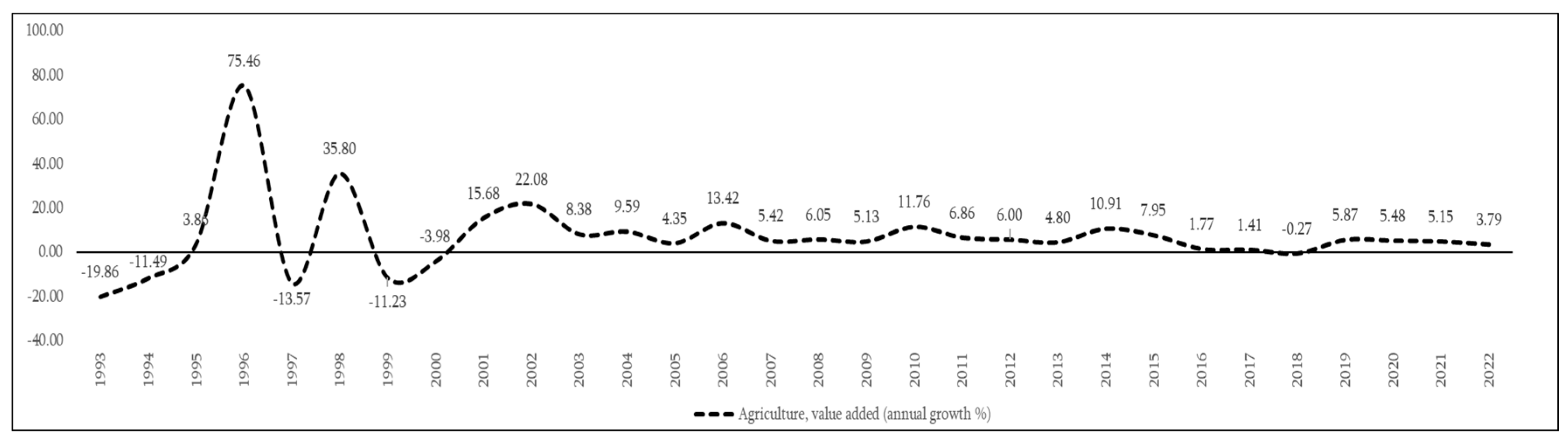

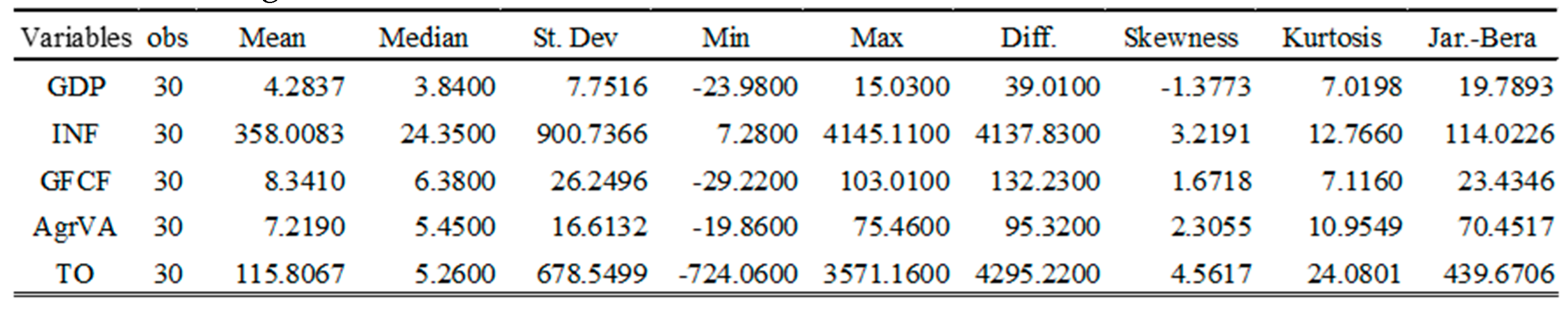

4. DATA ANALYSIS, RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Optimal lag selection

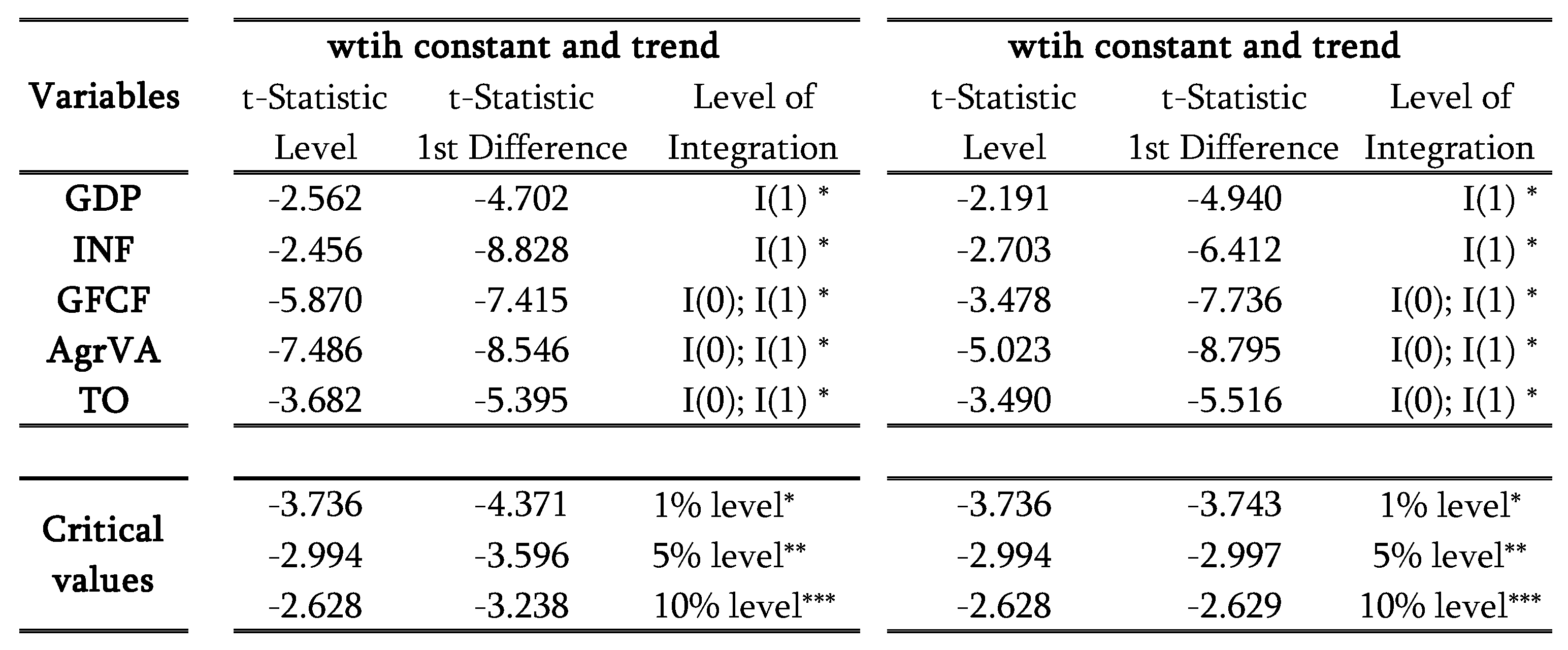

4.2. Unit root tests

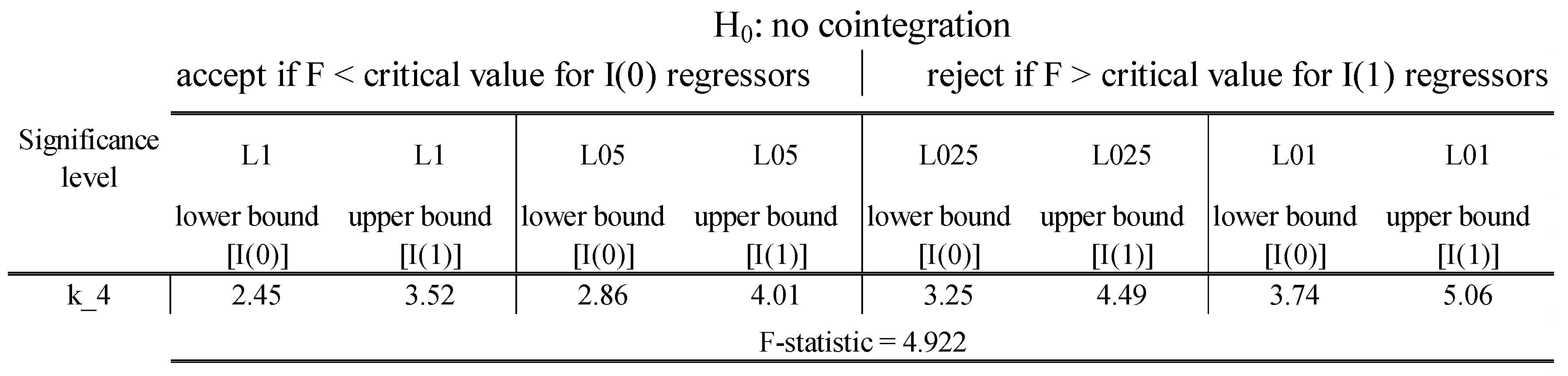

4.3. ARDL bound tests results for Cointegration

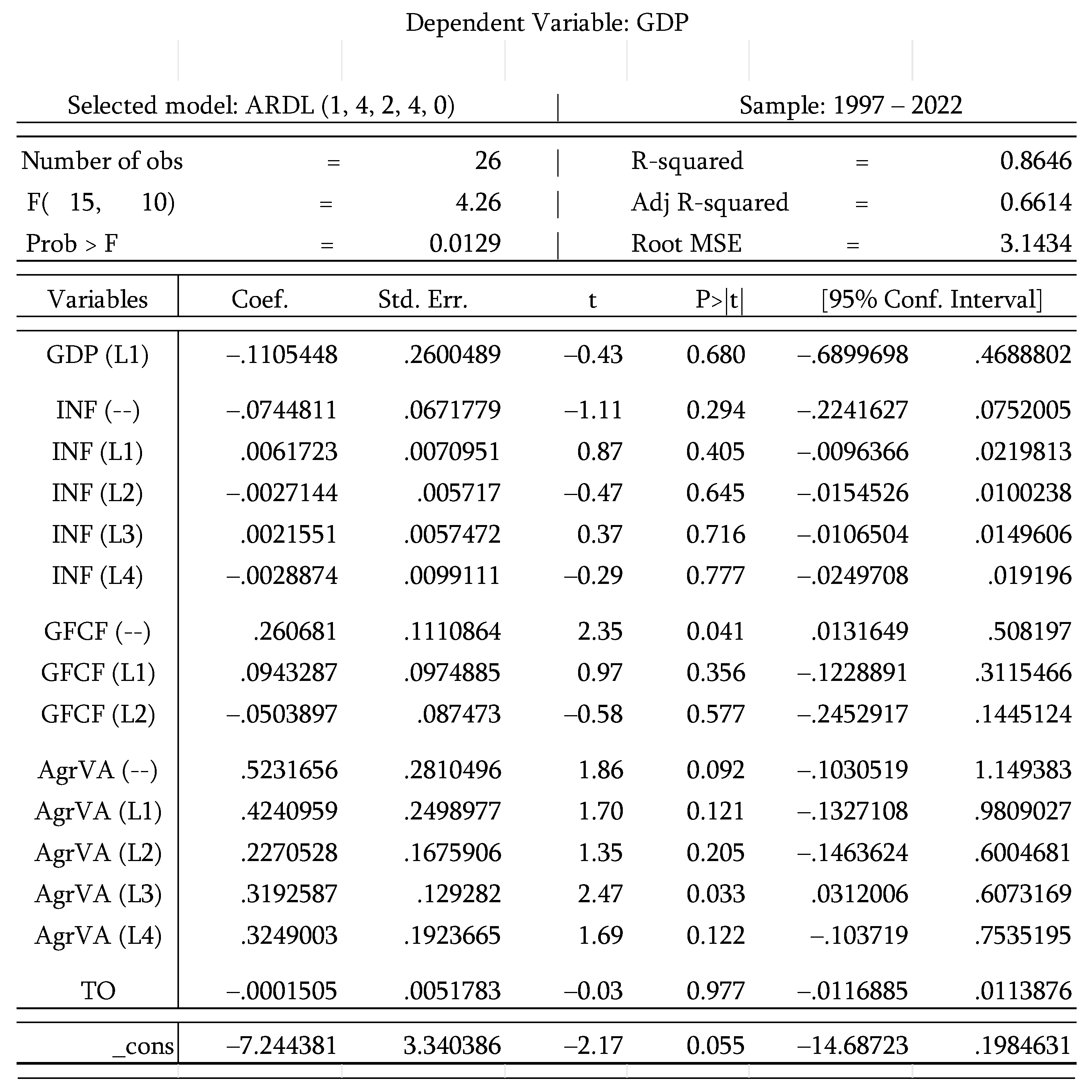

4.4. ARDL model estimation results

4.4.1. Long-run relationship

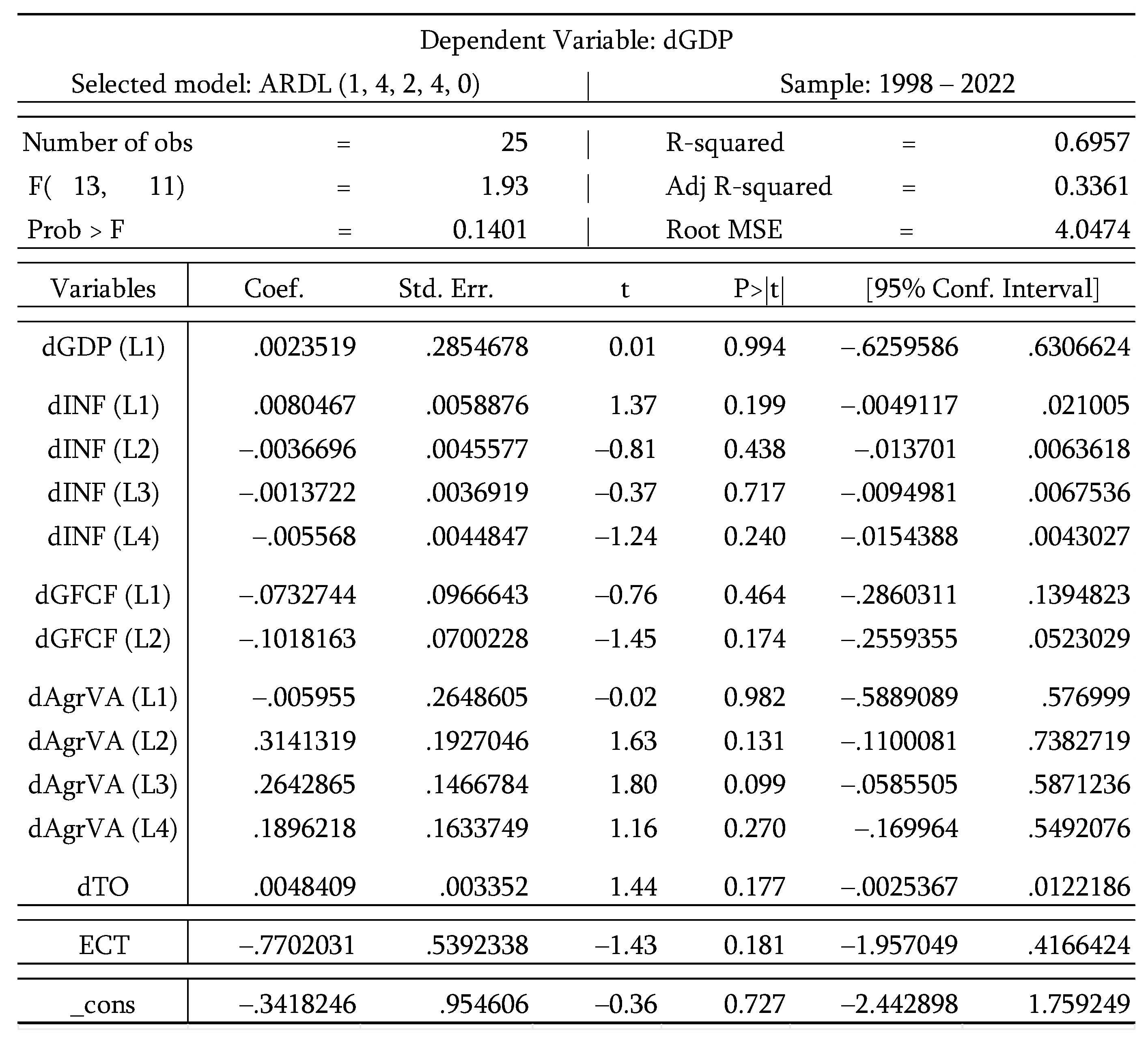

4.4.2. Short-run relationship

4.5. Diagnostic tests results

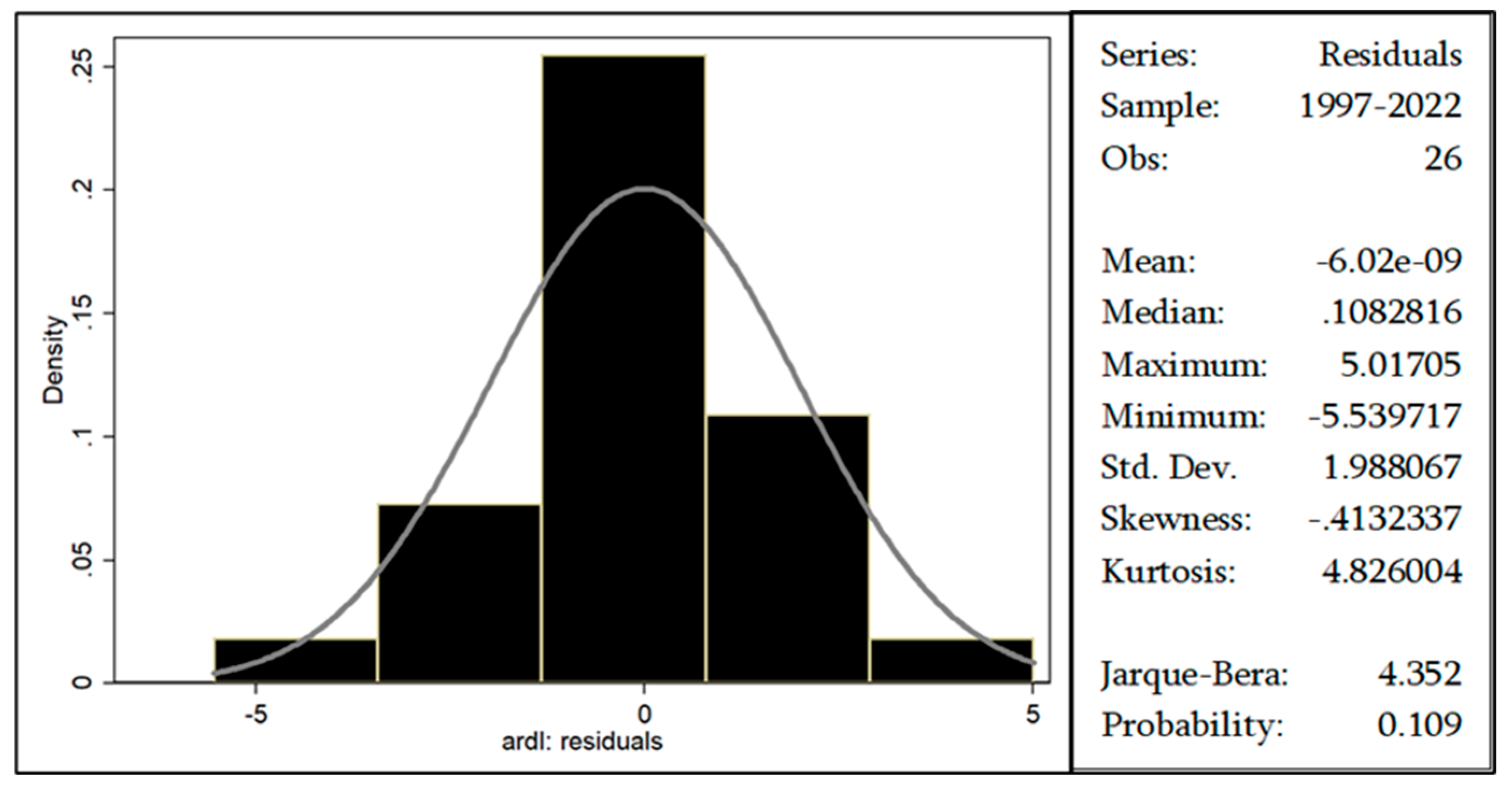

4.5.1. Normality tests

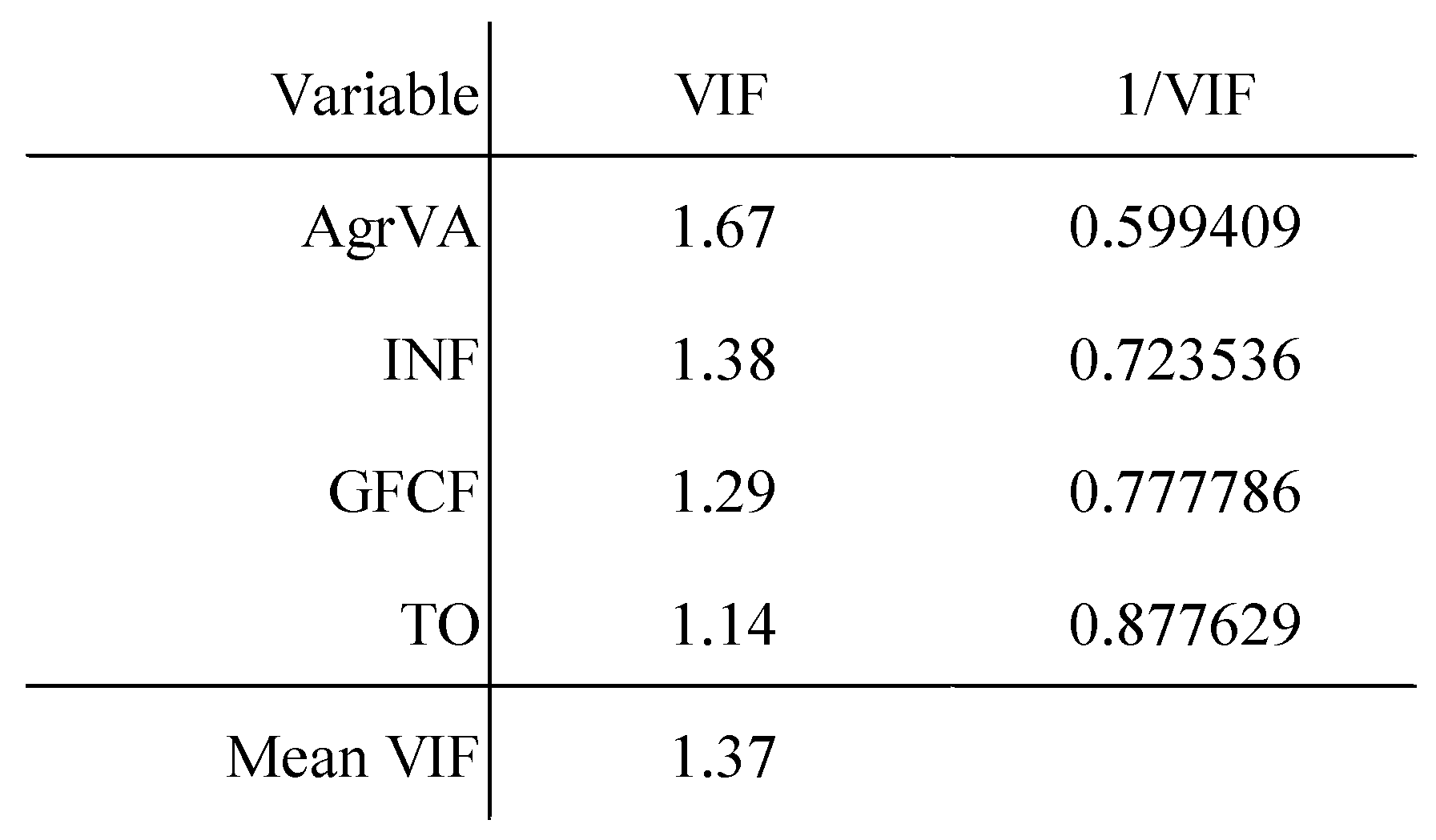

4.5.2. Multicollinearity test

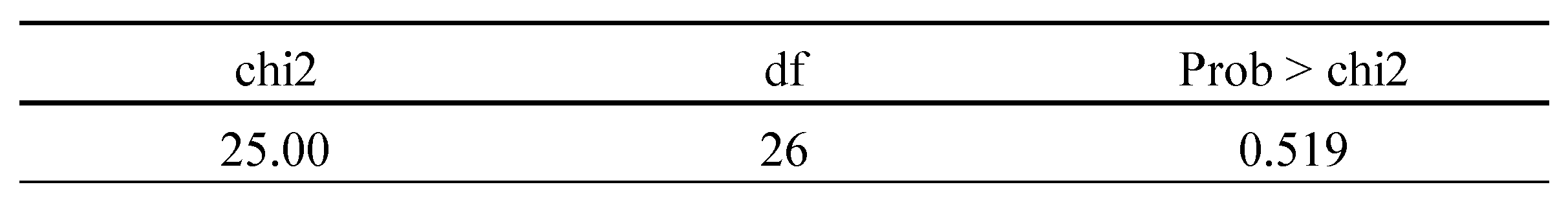

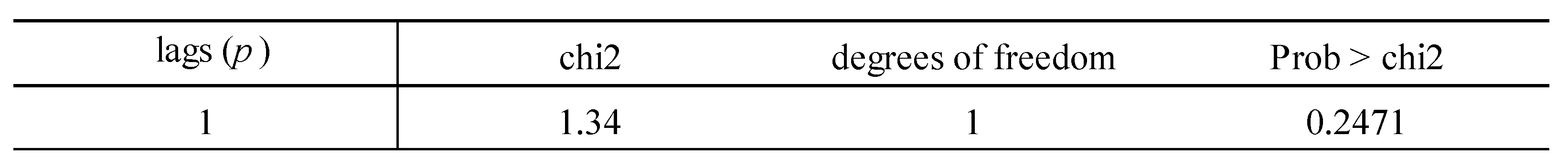

4.5.3. Autocorrelation test

4.5.4. Heteroscedasticity test

4.5.5. Stability tests

4.6. Causality analysis results

4.7. Discussion

5. CONCLUSIONS

5.1. Summary conclusions

5.2. Policy recommendations

5.3. Accomplishment of research objectives

- (1)

- “Is there a long or short run relationship between agriculture and economic growth?”

- (2)

- “What policy recommendations could help enhance agricultural sector productivity?”

5.4. Limitations of the research

References

- Akram, W., Hussain, Z., Sabir, H., & Hussain, I. (2008). Impact of agriculture credit on growth and poverty in Pakistan. European Journal of Scientific Research, 23, 243–251.

- Awan, A., & Aslam, A. (2015). Impact of Agriculture Productivity on Economic Growth: A Case Study of Pakistan. Global Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), 57-71.

- Awokuse, T., & Xie, R. (2015). Does Agriculture Really Matter for Economic Growth in Developing Countries? Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie, 63(1), 77-99.

- Badibanga, T., & Ulimwengu, J. (2020). Optimal investment for agricultural growth and poverty reduction in the Democratic Republic of Congo a two-sector economic growth model. Applied Economics, 52(2), 135-155.

- Bakari, S., & Abdelhafidh, S. (2018). Structure of Agricultural Investment and Economic Growth in Tunisia: An ARDL Cointegration Approach. Economic Research Guardian, Weissberg Publishing, 8(2), 40-64.

- Bakari, S., & El Weriemmi, M. (2022). Causality between Domestic Investment and Economic Growth in Arab Countries. MPRA Paper No 113079.

- Barro, R. (1991). Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407-443.

- Caetano Joao, M. (2005). Ekonomika angolského zemědělství. Caetano Joao, M., Jelinek, P., Knitl, A. (eds.) Lusofonní Afrika 1975-2005 África Lusófona. Ústav mezinarodních vztahů, 107-117.

- Caetano Joao, M., & Castro, A. (2023). The Impact of Agricultural Credit on the Growth of the Agricultural Sector in Angola. Sustainability, 15(20), No 14704.

- Christiaensen, L., Demery, L., & Kuhl, J. (2011). The (Evolving) Role of Agriculture in Poverty Reduction—An Empirical Perspective. Journal of Development Economics, 96, 239-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.10.006.

- Diao, X., Hazell, P., & Thurlow, J. (2010). World Development, 38(10), 1375-1383.

- Dilolwa, C. (2000). Contribuição à História Económica de Angola, (2nd ed.). Nzila.

- FAO (2023a). Gross domestic product and agriculture value added 2012–2021: Global and regional trends. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief 64. Acceded online: 14/06/2024:https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/c6828277-8ca4-43e4-9033-c28d488d1083/content.

- Gollin, D., Parente S., & Rogerson, R. (2002). The Role of Agriculture in Development. American Economic Review, 92(2), 160-164.

- Izuchukwu, O. (2011). Analysis of the Contribution of Agriculture Sector on the Nigerian Economy Development. World Review of Business Research, 1, 191-200.

- Johnston, B., & Mellor, J. (1961). The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development. The American Economic Review, 51, 566-593.

- Lewis, W. (1954). Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor. The Manchester School, 22, 139-191. [CrossRef]

- Matahir, H. (2012). The empirical investigation of the nexus between agricultural and industrial sectors in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(8), 225-230.

- Mellor, J. (1995). Agriculture on the road to industrialization. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Moussa, A. (2018). Does Agricultural Sector Contribute to the Economic Growth in Case of Republic of Benin? Journal of Social Economics Research, 5(2), 85-93.

- Msuya, E. (2007). The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Agricultural Productivity and Poverty Reduction in Tanzania. MPRA paper No 3671.

- Odetola, T., & Etumnu, C. (2013). Contribution of Agriculture to Economic Growth in Nigeria. The 18th Annual Conference of the African Econometric Society, Accra, Ghana, 1-29.

- Oyakhilomen, O., & Zibah, R. (2014). Agricultural Production and Economic Growth in Nigeria: Implication for Rural Poverty Alleviation. The Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, 53(3), 1-17.

- Phiri, J., Malec, K., Majune, S., Appiah-Kubi, S., Gebeltová, Z., Maitah, M., Maitah, K., & Abdullahi, K. (2020). Agriculture as a Determinant of Zambian Economic Sustainability. Sustainability, MDPI, 12(11), 1-14.

- Runganga, R., & Mhaka, S. (2021). Impact of Agricultural Production on Economic Growth in Zimbabwe. MPRA Paper No 106988.

- Sala-i-Martin, X. (1997) I Just Ran Two Million Regressions. American Economic Review, 87(2), 178-183.

- Sanyang, M. (2018). Does Agriculture have an Impact on Economic Growth? Empirical Evidence from the Gambia. European Journal of Business and Management, 10(24), 88-99.

- Schultz, T. (1964). Transforming Traditional Agriculture. Yale University Press.

- Sertoğlu, K., Ugural, S., & Bekun, F. (2017). The contribution of agricultural sector on economic growth of Nigeria. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(1), 547-552.

- Tiffin, R., & Irz, X. (2006). Is Agriculture the Engine of Growth? Agricultural Economics, 35, 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Timmer, P. (1988). The Agriculture Transformation. Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 1. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

- Valdés, A., & Foster, W. (2010). Reflections on the Role of Agriculture in Pro-Poor Growth. World Development, 38(10), 1362-1374.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).