Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Identification of Patients

2.2. Data Abstraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Procedure Characteristics

3.2. Risk Factors of CNS Infections

3.3. CSF Features in Patients with CNS Infections

3.4. Microbiology of CNS Infections and Antibiotics Use

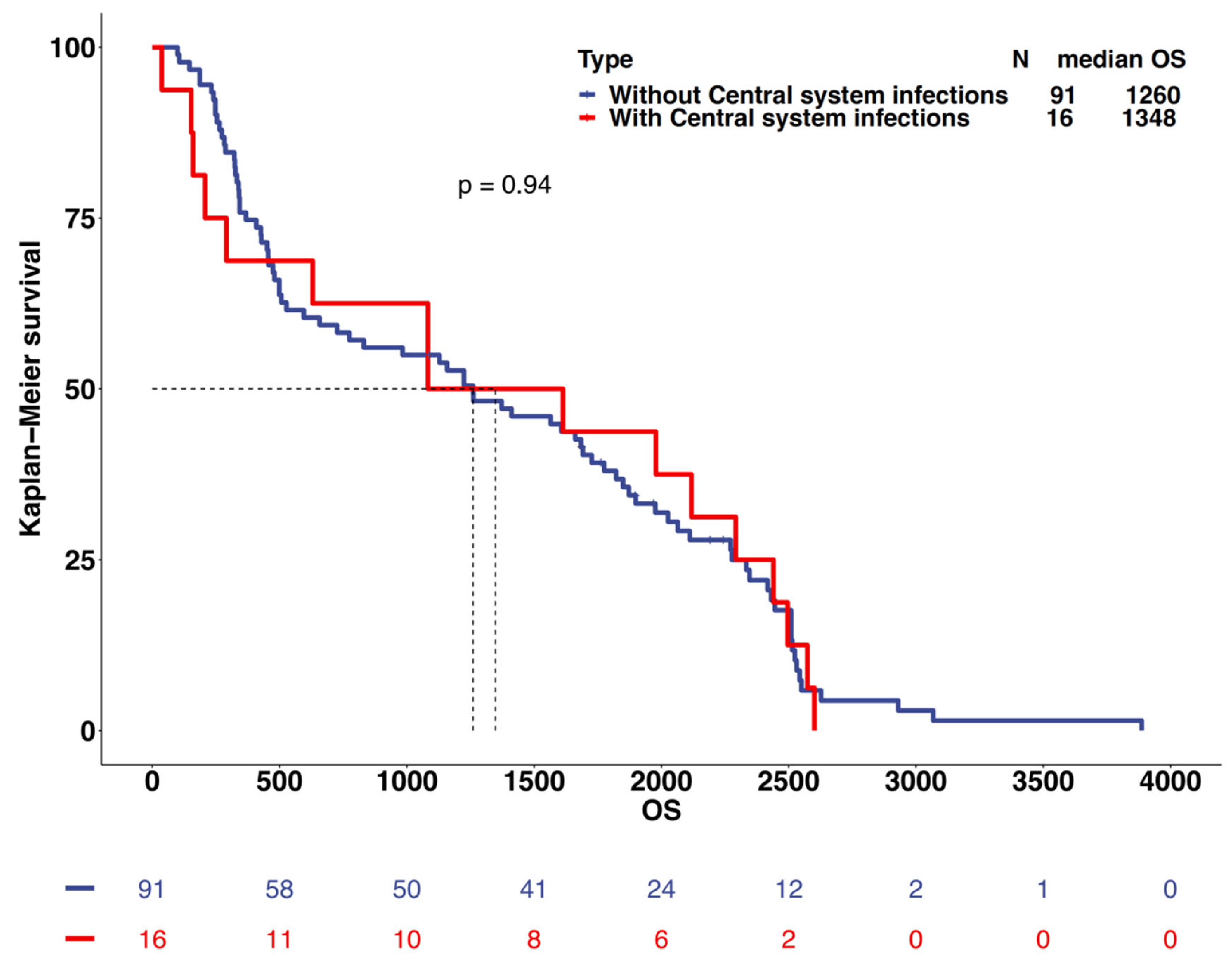

3.5. Survival Prediction

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of CNS Infections after Craniotomy for Gliomas

4.2. Risk Factors

4.3. The Characteristics of Cerebrospinal Fluid and the Use of Antibiotics

4.4. Survival Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Materials

References

- MC, R. M. EA, and F. FA, - Hospital-acquired meningitis in patients undergoing craniotomy: incidence. - Am J Infect Control. 2002 May;30(3):158-64. (- 0196-6553 (Print)): p. - 158-64. [CrossRef]

- AM, K. et al. - Risk factors for adult nosocomial meningitis after craniotomy: role of antibiotic. - Neurosurgery. 2006 Jul;59(1):126-33; discussion 126-33. (- 1524-4040 (Electronic)): p. - 126-33; discussion 126-33.

- McClelland S, r. and H. WA, - Postoperative central nervous system infection: incidence and associated factors. - Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jul 1;45(1):55-9. Epub 2007 May 21. (- 1537-6591 (Electronic)): p. - 55-9. [CrossRef]

- X, G. et al. - Clinical updates on gliomas and implications of the 5th edition of the WHO. - Front Oncol. 2023 Mar 14;13:1131642. eCollection, (- 2234-943X (Print)): p. - 1131642. [CrossRef]

- C, H. et al. - NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 2.2022. - J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023 Jan;21(1):12-20. (- 1540-1413 (Electronic)): p. - 12-20. [CrossRef]

- IS, K. et al. - Infections in patients undergoing craniotomy: risk factors associated with. - J Neurosurg. 2015 May;122(5):1113-9. Epub 2014 Oct, (- 1933-0693 (Electronic)): p. - 1113-9. [CrossRef]

- S, G. and H. R, - The Use of Adjunctive Steroids in Central Nervous Infections. - Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020 Nov 23;10:592017. (- 2235-2988 (Electronic)): p. - 592017.

- ML, D. et al. - Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. - N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 7;328(1):21-8. (- 0028-4793 (Print)): p. - 21-8. [CrossRef]

- KW, W. et al. - Post-neurosurgical nosocomial bacterial meningitis in adults: microbiology.

- TC, H. A. M, and D. MA, - CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria. - Am J Infect Control. 2008 Jun;36(5):309-32. (- 1527-3296 (Electronic)): p. - 309-32. [CrossRef]

- WM, T. et al. - CSF markers for diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in neurosurgical postoperative. - Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006 Sep;64(3A):592-5. (- 0004-282X (Print)): p. - 592-5. [CrossRef]

- O, M. et al. - Additive risk of surgical site infection from more than one risk factor following. - J Neurooncol. 2023 Apr;162(2):337-342. Epub 2023, (- 1573-7373 (Electronic)): p. - 337-342. [CrossRef]

- B, Y. et al. - Blood‒Brain Barrier Pathology and CNS Outcomes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. - Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Nov 11;19(11):3555. (- 1422-0067 (Electronic)): p. T - epublish. [CrossRef]

- RA, H. et al. - The role of pneumolysin in pneumococcal pneumonia and meningitis. - Clin Exp Immunol. 2004 Nov;138(2):195-201. (- 0009-9104 (Print)): p. - 195-201. [CrossRef]

- D, F. and W. GW, - Invasive Pneumococcal and Meningococcal Disease. - Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;33(4):1125-1141. (- 1557-9824 (Electronic)): p. - 1125-1141.

- EW, G. et al. - Pneumonia, Meningitis, and Septicemia in Adults and Older Children in Rural. - Clin Infect Dis. 2023 Feb 18;76(4):694-703. (- 1537-6591 (Electronic)): p. - 694-703. [CrossRef]

- C, Z. et al. - Simultaneous Detection of Key Bacterial Pathogens Related to Pneumonia and. - Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018 Apr 5;8:107. (- 2235-2988 (Electronic)): p. - 107. [CrossRef]

- A, R. et al. - Infant Escherichia coli urinary tract infection: is it associated with. - Arch Dis Child. 2022 Mar;107(3):277-281. (- 1468-2044 (Electronic)): p. - 277-281. [CrossRef]

- M, T. P. A, and C. N, - Question 1. How common is co-existing meningitis in infants with urinary tract. - Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):602-6. (- 1468-2044 (Electronic)): p. - 602-6. [CrossRef]

- SS, W. B. DN, and C. AT, - Prevalence of Concomitant Acute Bacterial Meningitis in Neonates with Febrile. - J Pediatr. 2017 May;184:199-203. Epub 2017 Feb, (- 1097-6833 (Electronic)): p. - 199-203. [CrossRef]

- J, N. et al. - Risk of Meningitis in Infants Aged 29 to 90 Days with Urinary Tract Infection: A. - J Pediatr. 2019 Sep;212:102-110.e5. Epub 2019, (- 1097-6833 (Electronic)): p. - 102-110.e5. [CrossRef]

- PL, A. et al. - Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection, Bacteremia, and Meningitis Among Febrile. - JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May 1;6(5):e2313354. (- 2574-3805 (Electronic)): p. - e2313354.

- LK, M. and H. DA, - Urinary Tract Infection: Pathogenesis and Outlook. - Trends Mol Med. 2016 Nov;22(11):946-957. Epub, (- 1471-499X (Electronic)): p. - 946-957. [CrossRef]

- GS, B. et al. - Tissue Immunity in the Bladder. - Annu Rev Immunol. 2022 Apr 26;40:499-523. (- 1545-3278 (Electronic)): p. - 499-523.

- PC, P. et al. - Rotating Gamma System Irradiation: A Promising Treatment for Low-grade Brainstem. - In Vivo. 2017 Sep-Oct;31(5):957-960. (- 1791-7549 (Electronic)): p. - 957-960. [CrossRef]

- Y, L. et al. - Expression of VEGF and MMP-9 and MRI imaging changes in cerebral glioma. - Oncol Lett. 2011 Nov;2(6):1171-1175. Epub 2011 Aug 17. (- 1792-1074 (Print)): p. - 1171-1175. [CrossRef]

- D, K. et al. - Technical principles in glioma surgery and preoperative considerations. - J Neurooncol. 2016 Nov;130(2):243-252. Epub 2016, (- 1573-7373 (Electronic)): p. - 243-252. [CrossRef]

- S, I. et al. - Tractography for Subcortical Resection of Gliomas Is Highly Accurate for Motor. - Cancers (Basel). 2021 Apr 9;13(8):1787. (- 2072-6694 (Print)): p. T - epublish. [CrossRef]

- JP, A. et al. - Inflammatory Monocytes and Neutrophils Regulate Streptococcus suis-Induced. - Infect Immun. 2020 Feb 20;88(3):e00787-19. Print 2020, (- 1098-5522 (Electronic)): p. T - epublish. [CrossRef]

- G, L. et al. - Cytokine and immune cell profiling in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with. - J Neuroinflammation. 2019 Nov 14;16(1):219. (- 1742-2094 (Electronic)): p. - 219. [CrossRef]

- M, D. et al. - Circulating monocytes engraft in the brain, differentiate into microglia and. - Brain. 2006 Sep;129(Pt 9):2394-403. Epub 2006 Aug 3. (- 1460-2156 (Electronic)): p. - 2394-403. [CrossRef]

- TJ, B. et al. - Salmonella Meningitis Associated with Monocyte Infiltration in Mice. - Am J Pathol. 2017 Jan;187(1):187-199. Epub, (- 1525-2191 (Electronic)): p. - 187-199. [CrossRef]

- JL, S. M. CR, and A. DJ, - Surgical Site Infection Prevention: A Review. - JAMA. 2023 Jan 17;329(3):244-252. (- 1538-3598 (Electronic)): p. - 244-252. [CrossRef]

- R, M. et al. - The safety and efficacy of dexamethasone in the perioperative management of. - J Neurosurg. 2021 Sep 24;136(4):1062-1069. Print, (- 1933-0693 (Electronic)): p. - 1062-1069. [CrossRef]

- KS, D. and K. PU, - Optimal Management of Corticosteroids in Patients with Intracranial Malignancies. - Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020 Jul 30;21(9):77. (- 1534-6277 (Electronic)): p. - 77. [CrossRef]

- HR, M. and B. SD, - Aseptic and Bacterial Meningitis: Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention. - Am Fam Physician. 2017 Sep 1;96(5):314-322. (- 1532-0650 (Electronic)): p. - 314-322.

- JM, C. et al. - Repeat lumbar puncture in adults with bacterial meningitis. - Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016 May;22(5):428-33. (- 1469-0691 (Electronic)): p. - 428-33. [CrossRef]

- OH, H.O. et al. - Development of a prediction rule for diagnosing postoperative meningitis: a. - J Neurosurg. 2018 Jan;128(1):262-271. Epub 2017, (- 1933-0693 (Electronic)): p. - 262-271. [CrossRef]

- HO, E. et al. - Clinical Infections, Antibiotic Resistance, and Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus. - Microorganisms. 2022 May 31;10(6):1130. (- 2076-2607 (Print)): p. T - epublish. [CrossRef]

- CR, H. et al. - Coagulase-negative staphylococcal meningitis in adults: clinical characteristics. - Infection. 2005 Apr;33(2):56-60. (- 0300-8126 (Print)): p. - 56-60. [CrossRef]

- R, S. et al. - Outcome following postneurosurgical Acinetobacter meningitis: an institutional. - Neurosurg Focus. 2019 Aug 1;47(2):E8. (- 1092-0684 (Electronic)): p. - E8. [CrossRef]

- CM, B. L.-W. KA, and K. SJ, - Meropenem: a review of its use in the treatment of serious bacterial infections. - Drugs. 2008;68(6):803-38. (- 0012-6667 (Print)): p. - 803-38. [CrossRef]

- GG, Z. et al. - Comparative review of the carbapenems.

- KS, Y. and C. EM, - Diagnosis of acute stroke. - Am Fam Physician. 2015 Apr 15;91(8):528-36. (- 1532-0650 (Electronic)): p. - 528-36.

- B, S. C. EY, and N. G, - Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis. - Am Fam Physician. 2021 Apr 1;103(7):422-428. (- 1532-0650 (Electronic)): p. - 422-428.

| Variable | No CNS Infections | CNS Infections | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Procedures | 276 | 61 | |

| Age(yrs) | 47.00 [33.75, 57.00] | 46.00 [34.00, 55.00] | 0.67 |

| Female Sex | 123 (44.57%) | 23 (37.70%) | 0.40 |

| BMI | 24.03 [20.29, 27.77] | 24.76 [21.03, 28.49] | 0.17 |

| Primary Glioma | 231 (83.70%) | 51 (83.61%) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (5.80%) | 2 (3.28%) | 0.63 |

| Comorbidities in Other Systems | 113 (40.94%) | 27 (44.26%) | 0.74 |

| Pre-op Radiotherapy | 40 (14.49%) | 12 (19.67%) | 0.41 |

| Pre-op Chemotherapy | 36 (13.04%) | 12 (19.67%) | 0.26 |

| Pre-op Steroid Use | 76 (27.54%) | 16 (26.23%) | 0.96 |

| Pre-op Concomitant Organ Infections | 3 (1.09%) | 3 (4.92%) | 0.13 |

| Pre-op Tumor Necrosis | 173 (62.68%) | 41 (67.21%) | 0.60 |

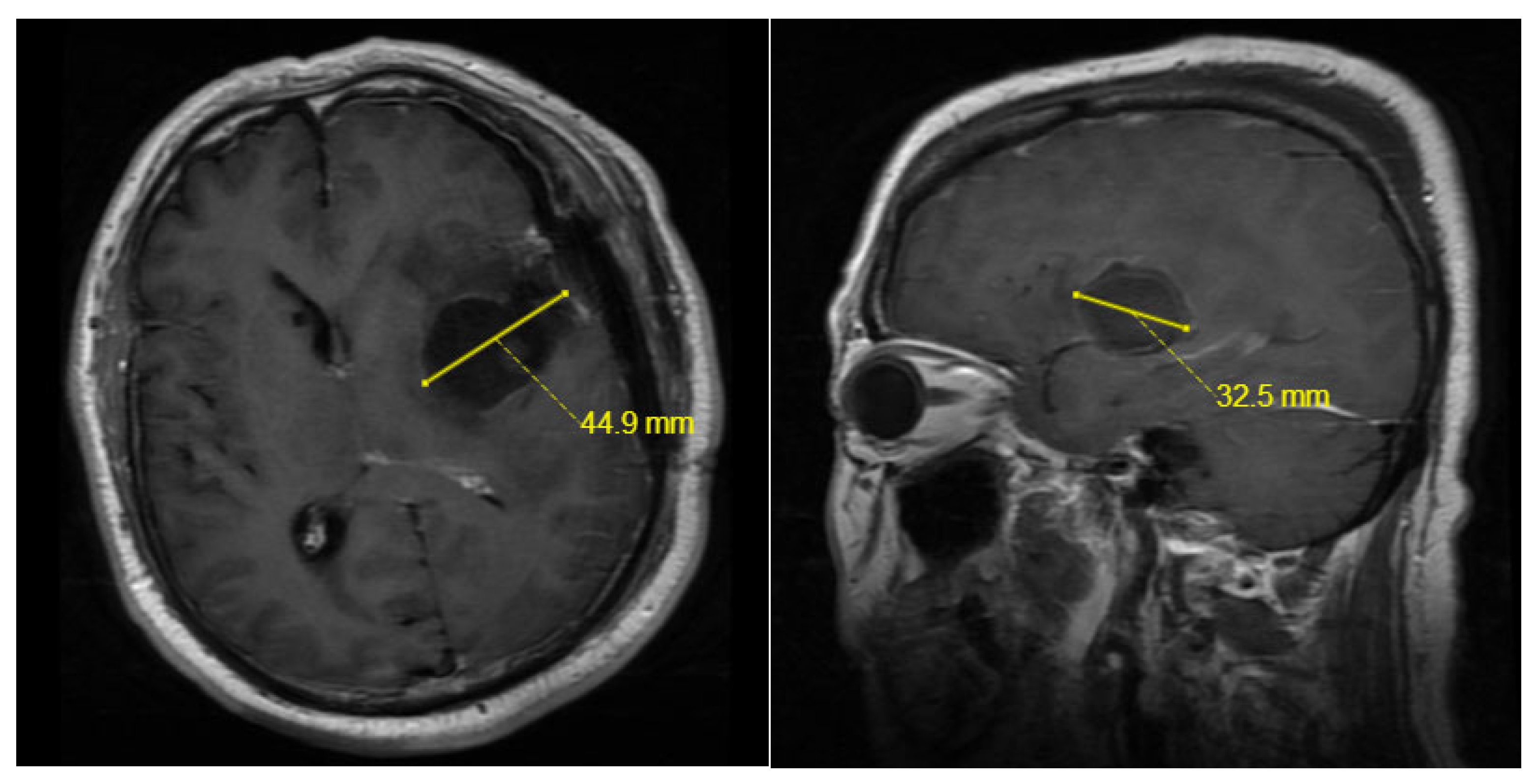

| Maximum Tumor Diameter(mm) | 41.60 [32.15, 55.00] | 49.50 [40.00, 60.00] | <0.01 |

| Surgery Duration(hours) | 5.00 [4.00, 6.30] | 5.50 [4.70, 7.00] | 0.01 |

| Ventricle Opened | 48 (17.39%) | 29 (47.54%) | <0.01 |

| Frontal/Ethmoid Opened | 18 (6.52%) | 4 (6.56%) | 1.00 |

| Tumor Cavity Catheter Insertion | 95 (34.42%) | 37 (60.66%) | <0.01 |

| External Drain Duration(days) | 0.00 [0.00, 1.00] | 1.00 [0.00, 3.00] | <0.01 |

| Post-op Other Systemic Infections | 10 (3.62%) | 11 (18.03%) | <0.01 |

| Post-op Seizures | 16 (5.80%) | 3 (4.92%) | 1.00 |

| Post-op Steroid Use | 254 (92.03%) | 59 (96.72%) | 0.31 |

| Post-op Maximum Cavity Diameter(mm) | 43.15 [33.77, 54.82] | 53.90 [46.90, 63.70] | <0.01 |

| Multiple Hospital Surgeries | 1 (0.36%) | 4 (6.56%) | <0.01 |

| Pre-op Blood Cell Tests | |||

| Absolute WBC Count (×10^9/L) | 6.20 [5.19, 7.74] | 6.53 [4.94, 8.17] | 0.57 |

| Absolute Lymphocyte Count(×10^9/L) | 1.74 [1.34, 2.22] | 1.68 [1.32, 2.12] | 0.38 |

| Lymphocyte % | 28.79 [18.92,38.66] | 27.20 [18.43,35.97] | 0.25 |

| Absolute Monocyte Count(×10^9/L) | 0.35 [0.28, 0.43] | 0.37 [0.30, 0.47] | 0.14 |

| Monocyte % | 5.60 [4.68, 6.50] | 6.30 [4.90, 6.90] | 0.03 |

| Absolute Neutrophil Count(×10^9/L) | 3.75 [2.83, 4.87] | 3.70 [2.89, 5.42] | 0.48 |

| Neutrophil % | 60.80 [54.05, 68.82] | 62.60 [56.00, 69.60] | 0.24 |

| Absolute Eosinophil Count (×10^9/L) | 0.09 [0.05, 0.15] | 0.08 [0.05, 0.14] | 0.76 |

| Eosinophil % | 1.50 [0.80, 2.50] | 1.50 [0.80, 2.60] | 0.94 |

| Absolute Basophil Count (×10^9/L) | 0.03 [0.02, 0.03] | 0.02 [0.02, 0.04] | 0.97 |

| Basophil % | 0.40 [0.30, 0.60] | 0.40 [0.20, 0.60] | 0.83 |

| Variable | OR | CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricle Opened | 2.97 | 1.54-5.71 | <0.01 |

| Post-op Other Systemic Infections | 4.03 | 1.34-12.14 | 0.01 |

| Post-op Maximum Cavity Diameter | 1.03 | 1.01-1.06 | 0.02 |

| Monocyte % | 1.19 | 1.01-1.41 | 0.04 |

| Tumor Cavity Catheter Insertion | 1.63 | 0.66-4.02 | 0.29 |

| External Drain Duration | 1.07 | 0.84-1.38 | 0.57 |

| Maximum Tumor Diameter | 1.00 | 0.97-1.02 | 0.72 |

| Surgery Duration | 0.96 | 0.81-1.15 | 0.66 |

| Multiple Hospital Surgeries | 8.10 | 0.73-89.54 | 0.09 |

| Variable | Median | IQR | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein(g/L) | 1.73 | [1.03, 3.06] | 0.15-0.45 |

| Glucose(mmol/L) | 2.7 | [1.90, 3.70] | 2.4-4.5 |

| Chloride(mmol/L) | 120 | [116.00, 122.00] | 120-132 |

| WBC(10^6/L) | 1478 | [467, 4204.25] | 0-8 |

| Multinucleated Cell % | 84.1 | [74.55, 90.83] | <70 |

| Bacteria | Sensitive Antibiotics | Resistant Antibiotics |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Gentamicin,Linezolid, Selectrin,Teicoplanin, Vancomycin |

Ciprofloxacin,Oxacillin, Erythromycin,Penicillin G |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Gentamicin,Linezolid, Vancomycin,Rifampicin, Selectrin,Teicoplanin |

Oxacillin,Penicillin G |

| Acinetobacter baumanii |

Minocycline,Tigecycline | Amikacin,Ceftazidime, Ciprofloxacin,Levofloxacin,Cefperazone-Sulbactam,Meropenem,Selectrin, Sulbactam-Ampicillin, Doxycycline,Cefepime, Imipenem,Tobramycin, Piperacillin-Tazobactam |

| Antibiotic Varieties | Frequency of Use(n=50) | Average Time of Use(days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | Vancomycin | 43 | 7.79 |

| Linezolid | 4 | 7.75 | |

| Gram-negative | Meropenem | 27 | 8.41 |

| Cefperazone | 17 | 6.88 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 6 | 6.83 | |

| Ceftazidime | 7 | 8.43 | |

| Common Antibiotic Combinations | Meropenem+ Vancomycin |

23 | 8.13 |

| Cefperazone+ Vancomycin | 8 | 6.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).