1. Introduction

Concrete, with its excellent mechanical properties and durability, is one of the most widely used materials in the construction industry. However, its high density and the environmental impact of its production have prompted the search for more sustainable and lightweight alternatives. In this context, lightweight concrete has emerged as a promising solution, not only allowing for a reduction in structural weight without significantly compromising its mechanical properties but also reducing the environmental impact of construction.

The use of organic materials as lightweight agents and stabilizers in concrete is a trend under increasing exploration. Among these, nopal mucilage and aloe vera stand out for their adhesive properties and ability to improve the workability of concrete [

1,

2]. Mucilage, a natural polysaccharide, acts as a binding agent and contributes to water retention, which is crucial for concrete curing [

3]. On the other hand, Aloe vera has demonstrated properties that enhance the plasticity and strength of concrete and offer antimicrobial benefits that can prolong the material's lifespan [

4,

5].

Beyond the benefits above, including organic materials in lightweight concrete positively impacts environmental sustainability. Reducing the carbon footprint and using renewable resources are critical in mitigating climate change [

2,

6,

7,

8]. Specifically, expanded clay and tuff, used as lightweight agents, not only decrease the weight of concrete but also improve its thermal and acoustic insulation, contributing to the energy efficiency of buildings [

9,

10].

In previous works, materials were crushed to obtain particles of suitable size for use in concrete mixtures. Granulometric analyses, density tests, and chemical composition studies were conducted using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) [

1,

5]. Extracts were obtained from fresh plants through dehydration and cold extraction processes. Their rheological and chemical properties were analyzed, determining their viscosity and polysaccharide content [

2,

3].

Based on these material characteristics, several concrete mixtures were formulated by substituting specific percentages of coarse aggregate with volcanic tuff and expanded clay. The mixtures were prepared with varying proportions of nopal mucilage and aloe vera extract as additives [

6,

10].

Concrete samples were cured and tested at different ages (7, 14, and 28 days) using a hydraulic press to measure their compressive strength [

9,

11]. The density and specific weight of fresh and hardened concrete were determined to evaluate the lightweight effect of the materials used [

12,

13]. Slump and water retention tests were performed to assess the workability and behavior of the concrete during curing [

4,

5]. Some studies conducted life cycle assessments (LCA) to determine the environmental impact of concrete mixtures, considering the reduction of CO

2 emissions and the use of renewable materials [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

According to the literature, adding nopal mucilage and aloe vera significantly increased the compressive strength of lightweight concrete. Samples incorporating these additives showed an increased strength of 15-20% compared to control mixtures without additives [

2,

4]. The partial replacement of conventional aggregates with volcanic tuff and expanded clay reduced the concrete density by 25-30%, considerably reducing structural weight without adversely affecting mechanical properties [

9,

10].

Mixtures with nopal mucilage and aloe vera exhibited better workability and water retention, facilitating curing and reducing surface cracks [

1,

3]. Improvements in the thermal and acoustic insulation properties of lightweight concrete were observed, especially in mixtures that included expanded clay. This suggests potential energy-efficient construction applications [

9,

13]. Sustainability assessments indicated a significant reduction in the carbon footprint of lightweight concrete mixtures due to using renewable materials and a decrease in the required cement [

6,

14].

Combining expanded clay, tuff, and organic stabilizers such as nopal mucilage and aloe vera presents an innovative solution for the construction industry. This approach addresses the need for lighter and more sustainable materials and offers improvements in concrete's physical and mechanical properties, such as higher compressive strength and better durability [

11,

13]. The present research aims to evaluate the performance of these combinations, providing a scientific basis for their practical application in the construction sector.

2. Materials and Methods

This study collected 2.8 kg of nopal and 2.3 kg of aloe vera. These materials were cleaned and cut into quadrangular elements measuring 1 to 2 cm on each side. Each material was macerated in water for 24 hours at a 1:10 (kg/L) ratio of distilled water. After this period, the organic materials were ground and filtered, recovering the supernatant containing the extract. This viscous liquid product was left to stand for 24 hours. The extracted mucilage and aloe vera were evaluated for extract concentration in the maceration solution through liquid-liquid extraction. 80 mL aliquots were taken, and 40 mL of ethyl acetate (Merck, reagent grade) were added. Three washes were performed in a separation funnel, recovering the organic material and adding anhydrous sodium sulfate (Merck, reagent grade) to eliminate moisture residues. Subsequently, the solvent was evaporated, and the amount of organic material in the mixture was determined by gravimetry. This procedure was performed in triplicate, and the concentration of nopal mucilage extract was 1035.42 ± 27.88 mg/L, while the aloe vera extract concentration was 526.25 ± 11.92 mg/L.

The fine aggregate and substitute aggregates (river sand, expanded clay, and tuff) were characterized according to standard procedures to determine moisture content [

23], water absorption capacity [

22], density, and bulk density [

24]. Based on the obtained information (

Table 1), the mix design was carried out using the ACI method.

Table 2 shows the proportions determined using this methodology. For each mix mentioned in

Table 3, three cylindrical specimens of 15 cm diameter and 30 cm height were produced. The specimens were cured by total immersion for nine days.

Once the mixes were prepared and the lightweight concrete specimens obtained, they were subjected to various characterization tests. The fresh concrete consistency test was used to determine its consistency and viability, verifying that the correct amount of water had been added to the mix. This test was conducted according to ASTM C143.

In the water absorption test by immersion, the volume of a sample in both wet and dry states was determined by calculating the amount of water absorbed by the difference in weights. The specimens were submerged in water for seven days, weighed, left to stand for 24 hours at room temperature, and dried in an oven at 75°C for 24 hours to accelerate the drying process. The compression test evaluated the material's behavior under a compressive load, measuring deformation, stress, and strain variables. The results were used to verify that the concrete mix met the specified strength requirements for the determined structure. This test was performed according to ASTM C39 using a CONTROLS Automax Model C13C04 machine.

Using Image J software, a HiView 1600x digital microscope was used to analyze the concrete morphology and obtain images, which were later used to determine its fractal dimension. For measuring thermal properties, the KD2 Pro equipment with a dual-needle sensor was employed, measuring thermal conductivity (K, [W/(mK)]), thermal resistivity (ρ, [°C(cm/W)]), volumetric heat capacity (C, [MJ/(m3*K)]), and thermal diffusivity (D, [mm2/s]).

3. Results and Discussion

Table 3 shows the absorption, bulk density, and slump test results.

According to the results, the LCAT mixture (Cement-Sand-Water-Tuff) has a bulk density of 1612.14 kg/m³, a water absorption of 4.501%, and a slump of 2 cm. These values indicate that this mixture has moderate water absorption and adequate consistency with an acceptable slump. In contrast, the LCNT mixture (Cement-Sand-Nopal Mucilage-Tuff) shares the same bulk density as LCAT (1612.14 kg/m³) but has slightly higher water absorption (4.509%) and a slump of 0 cm, suggesting a drier and less workable mix. This behavior was also observed in the LCNAE mixture (Cement-Sand-Nopal Mucilage-Expanded Clay) with a bulk density of 1706.46 kg/m³ and water absorption of 4.897%.

The LCST mixture (Cement-Sand-Aloe Vera-Tuff) has a higher bulk density than the previous ones (1632.26 kg/m³) and significantly high water absorption (11.472%). Its slump is described as "spreads," indicating a very fluid consistency, possibly too liquid to maintain shape. The LCAAE mixture (Cement-Sand-Water-Expanded Clay) has the highest bulk density of all the mixtures (1803.28 kg/m³) and a water absorption of 6.252%. The observed slump is also described as "spreads," suggesting that the expanded clay, in combination with water, produces a very fluid mixture [

25,

26,

27].

The LCSAE mixture (Cement-Sand-Aloe Vera-Expanded Clay) has a bulk density of 1657.41 kg/m³ and the lowest water absorption (4.2 %); however, its 2 cm slump suggests good workability and consistency.

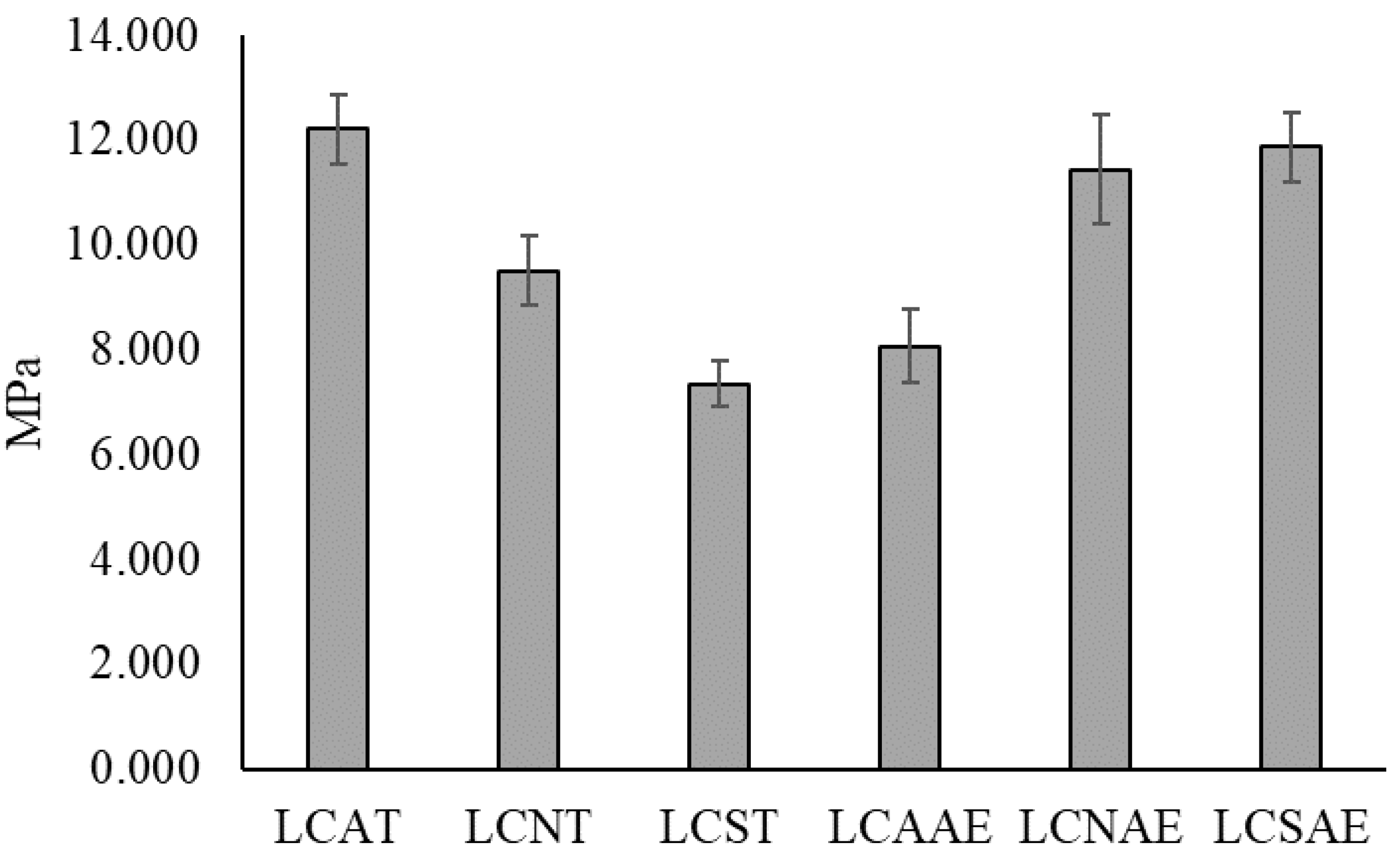

Figure 1 shows the results of the compressive strength test. It can be observed that the LCAT mixture, composed of cement, sand, water, and tuff, presents the highest compressive strength with a value of 12.207 MPa. This indicates that this mixture has a solid and robust structure, suitable for applications requiring high strength. In contrast, the LCNT mixture, incorporating nopal mucilage instead of water, has a compressive strength of 9.503 MPa. Although this value is lower than LCAT, the mixture still provides considerable strength, but adding nopal mucilage appears to reduce strength compared to using water.

The LCST mixture, using aloe vera instead of water, presents a strength of 7.343 MPa, the lowest among the mixtures containing tuff. Incorporating aloe vera weakens the mixture, making it less suitable for applications requiring high structural strength. On the other hand, the LCAAE mixture, including expanded clay instead of tuff, shows a compressive strength of 8.063 MPa. Although this value is lower than LCAT, the mixture has moderate strength, suggesting that expanded clay with water forms a less resistant mixture than the combination of tuff and water [

27,

28,29].

The LCNAE mixture, using nopal mucilage and expanded clay, has a compressive strength of 11.447 MPa. This mixture shows high strength and is close to LCAT, indicating that nopal mucilage positively affects strength when combined with expanded clay. Finally, the LCSAE mixture, incorporating aloe vera and expanded clay, presents a strength of 11.870 MPa. Despite the presence of aloe vera, the combination with expanded clay results in a solid and robust mixture that is close in strength to LCAT and LCNAE.

Table 4 presents the results of the thermal characterization of the mixtures. The LCAT mixture shows properties indicating good thermal conductivity and heat storage capacity, making it suitable for applications requiring thermal stability. The LCNT mixture, on the other hand, exhibits higher thermal conductivity and diffusivity than LCAT, suggesting that including nopal mucilage enhances the concrete's ability to transfer heat [

27,

28].

The LCST mixture shows higher temperature, thermal conductivity, and heat capacity values, demonstrating that the aloe vera mixture is more efficient in heat transfer and storage, although with lower resistivity. The LCAAE mixture, which combines cement, sand, water, and expanded clay, shows high thermal diffusivity, indicating rapid heat transfer, albeit with lower heat capacity than the other mixtures. The LCNAE mixture, composed of cement, sand, nopal mucilage, and expanded clay, has higher resistivity and heat capacity, which, together with lower thermal conductivity, this mixture is more efficient in heat retention, although it transfers heat more slowly. Finally, the LCSAE mixture, similar to LCNAE, exhibits high resistivity and heat capacity with low thermal conductivity, indicating good heat retention [

7,

10,

27,

28].

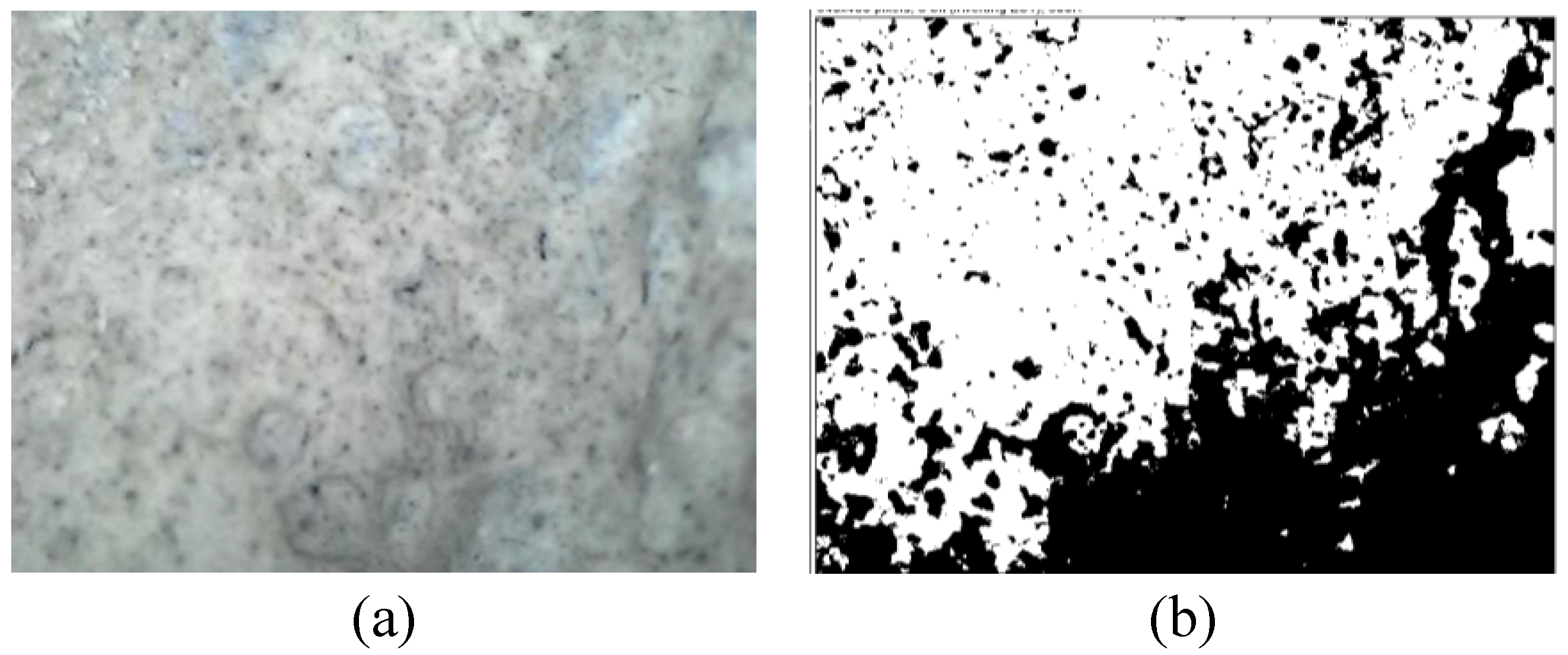

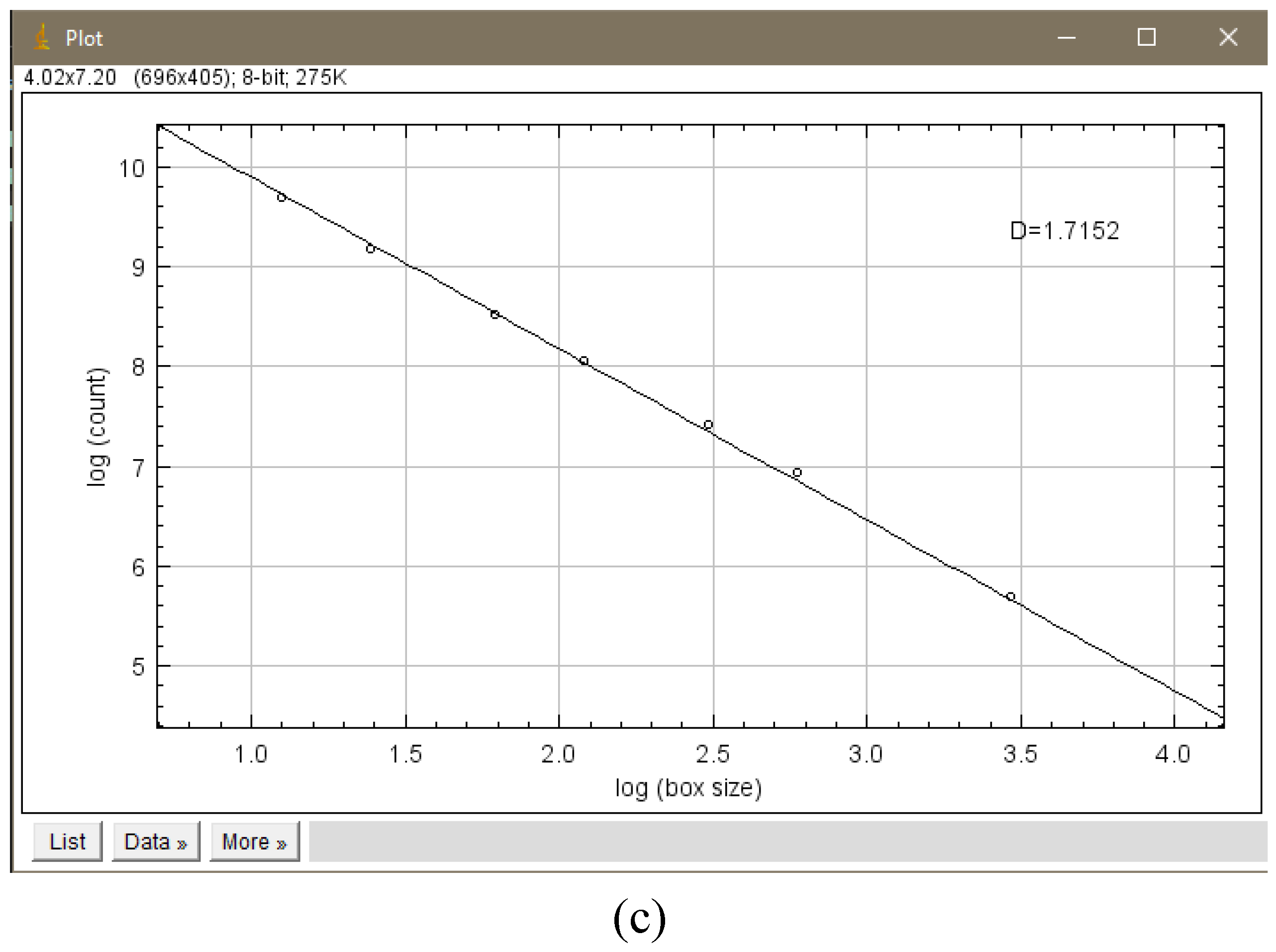

Micrographs obtained from the samples were used for a fractal dimension analysis to determine the probable homogeneity of the mixture components.

Figure 2 shows an example of the analysis performed for all specimens, and

Table 5 shows the fractal dimension values. The fractal dimension of the surface refers to the measure of the roughness or complexity of a material's surface and does not necessarily characterize its internal structure. However, the surface fractal dimension can be related to specific internal structure properties, especially in porous or heterogeneous materials, where surface complexity may reflect internal network characteristics.

The LCAT mixture (Cement-Sand-Water-Tuff) has a fractal dimension of 1.71787 ± 0.0024, indicating a relatively complex internal structure, which may contribute to its high compressive strength and good thermal stability. The LCNT mixture (Cement-Sand-Nopal Mucilage-Tuff) shows a higher fractal dimension compared to LCAT, suggesting a more complex and heterogeneous internal structure, possibly due to the incorporation of nopal mucilage, which can affect the material's internal distribution.

The LCST mixture (Cement-Sand-Aloe Vera-Tuff) shows a fractal dimension of 1.6907 ± 0.0039, the lowest among the tuff mixtures. This suggests a less complex internal structure, which could be related to its lower compressive strength. The LCAAE mixture (Cement, Sand, Water, Expanded Clay) has a fractal dimension of 1.7094 ± 0.0079. This slightly lower fractal dimension than LCAT indicates a moderately complex internal structure consistent with its intermediate compressive strength and thermal properties.

The LCNAE mixture (Cement-Sand-Nopal Mucilage-Expanded Clay) presents a fractal dimension of 1.7515 ± 0.0049. This high fractal dimension suggests a highly complex and heterogeneous internal structure, which may contribute to its high compressive strength and good heat retention. The LCSAE mixture (Cement-Sand-Aloe Vera-Expanded Clay) shows a fractal dimension of 1.7206 ± 0.0129. This fractal dimension, similar to LCAT's, indicates a complex and robust internal structure, reflected in its high compressive strength and good thermal properties.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated six concrete mixtures with different dosages of tuff, expanded clay, nopal mucilage, and aloe vera as lightweight and reinforcing agents. Physical and mechanical tests were conducted to determine if these elements can be used in the construction industry when lightweight concrete is required.

The results show that mixtures including aloe vera (LCST and LCSAE) exhibit extreme water absorption and consistency behaviors, with LCST being very fluid and LCSAE showing good workability. Mixtures with nopal mucilage (LCNT and LCNAE) tend to be drier and less workable. In contrast, mixtures with expanded clay (LCAAE and LCNAE) have higher bulk density and variations in consistency and water absorption.

Mixtures with water, such as LCAT and LCAAE, tend to have variable strength depending on the lightweight agent, either tuff or expanded clay. Mixtures that include nopal mucilage, such as LCNT and LCNAE, show improved strength when expanded clay is used instead of tuff. On the other hand, mixtures with aloe vera, LCST, and LCSAE exhibit a notable difference in strength, being considerably lower with tuff and higher with expanded clay. This suggests combining expanded clay with nopal mucilage or aloe vera can offer excellent compressive strength in lightweight concrete mixtures.

According to the literature, the lightweight concrete mixtures studied in this work present mechanical strength properties ranging from low to moderate in the following order:

LCST (Cement, Sand, Aloe Vera, Tuff): 7.343 MPa (Low strength)

LCAAE (Cement, Sand, Water, Expanded Clay): 8.063 MPa (Low strength)

LCNT (Cement, Sand, Nopal Mucilage, Tuff): 9.503 MPa (Low strength)

LCNAE (Cement, Sand, Nopal Mucilage, Expanded Clay): 11.447 MPa (Moderate strength)

LCSAE (Cement, Sand, Aloe Vera, Expanded Clay): 11.870 MPa (Moderate strength)

LCAT (Cement, Sand, Water, Tuff): 12.207 MPa (Moderate strength)

Stabilized concrete mixtures exhibit different thermal and physical properties depending on the lightweight and stabilizing agents used. Mixtures with nopal mucilage and aloe vera show variations in thermal conductivity and heat capacity, affecting their heat transfer and storage efficiency. Combining expanded clay and nopal mucilage or aloe vera can offer good heat retention and thermal stability in lightweight concrete mixtures.

The fractal dimension of stabilized concrete mixtures provides valuable information about the material's complexity and internal structure. Mixtures with nopal mucilage and aloe vera tend to show variations in fractal dimension, which can influence their mechanical and thermal properties. Combining expanded clay and nopal mucilage or aloe vera can result in a more complex internal structure and higher compressive strength.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.S.D. and D.M.G.; methodology, J.F.P.S., P.F.B. and D.M.G; formal analysis, J.F.P.S., and D.M.G.; investigation, R.R.G.V.; resources, E.J.S.D and A.P.P.; data curation, J.F.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.G.; writing—review and editing, J.F.P.S.; supervision, P.F.B.; project administration, E.J.S.D. AND A.P.P.; funding acquisition, E.J.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This work was developed thanks to the COTACYT project TAMPS-2023-01-05-01 and utilized infrastructure from the UAT INVEST 2023 project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Gómez, H.; Fernández, M.; Álvarez, P. Aloe vera in construction materials. J Eco-friendly Mater 2022, 41, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, L.; Pérez, J.; Torres, R. Organic stabilizers in concrete: A review. Mater Sci J 2021, 29, 300–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R.; Hernández, A.; Ruiz, F. Water retention properties of cactus mucilage. Adv Constr Mater 2020, 33, 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, G.; Gómez, L.; Martínez, D. Mechanical properties of aloe-stabilized concrete. Int J Struct Eng 2019, 27, 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, S.; Díaz, J.; García, E. Benefits of aloe in concrete mixtures. Constr Sci Rev 2021, 39, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, T.; Santos, M.; Jiménez, A. Sustainable building materials: An overview. Green Build J 2020, 22, 190–205. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, P.; Ruiz, S.; Díaz, J. Enhancing concrete with natural fibers. Constr Sci Technol J 2021, 39, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.; Smith, J.; Wilson, K. Reducing the carbon footprint in concrete production. Sustain Mater J 2019, 21, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, R.; Muñoz, A.; Silva, J. Acoustic insulation in lightweight concrete. J Build Acoust 2023, 38, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, C.; Vargas, L.; Morales, P. Thermal properties of lightweight aggregates. Energy Effic Constr 2022, 47, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, A.; Morales, J.; Ríos, C. Performance of natural additives in concrete. J Mater Civil Eng 2021, 31, 405–420. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.; Williams, B.; Smith, J. Innovations in concrete technology. J Mod Constr 2019, 32, 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, E.; Fernández, R.; Pérez, S. Durability of eco-friendly concrete. Constr Mater J 2022, 28, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Clark, R.; Davis, S. Environmental impact of lightweight concrete. Sustain Constr Res 2020, 45, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.; Johnson, M.; Lee, A. Green building materials: Trends and applications. Eco-Conscious Constr Rev 2020, 50, 320–335. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, A.; Pérez, L.; García, E. Lightweight concrete: A sustainable approach. Green Materials Res 2020, 44, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.; Johnson, M.; Davis, S. Advances in sustainable construction materials. Eco-Friendly Constr Rev 2020, 48, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, A.; Santos, H.; Jiménez, M. Environmental benefits of lightweight aggregates. J Green Constr 2021, 29, 310–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, C.; Silva, J.; Díaz, R. Innovations in eco-friendly construction materials. Sustain Eng J 2023, 37, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Brown, P.; Wilson, K. Lightweight concrete: Advances and challenges. J Constr Mater 2019, 34, 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Clark, R.; Brown, P. The future of lightweight concrete. J Mod Constr Mater 2021, 33, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Organismo Nacional de Normalización. NMX-C-166-ONNCCE: Contenido de agua por secado - Método de ensayo 2018, ONNCCE.

- Organismo Nacional de Normalización. NMX-C-164-ONNCCE: Determinación de la densidad relativa y absorción de agua del agregado grueso - Método de ensayo 2014, ONNCCE.

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D-698: Standard test method for laboratory compaction characteristics of soil using standard effort (600 kN-m/m³) 2021, ASTM.

- Santos, M.; López, J.; Fernández, T. The role of natural fibers in concrete. Mater Struct J 2022, 35, 180–195. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.; Morales, E.; Muñoz, A. Performance analysis of natural additives in concrete. J Civil Eng Mater 2022, 42, 210–225. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, R.; Martínez, L.; Gómez, H. Aloe vera as a sustainable concrete additive. Int J Green Build Mater 2022, 36, 180–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.; Brown, P.; Clark, R. Organic additives in construction. J Sustain Mater 2021, 26, 210–225. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).