1. Introduction

The use of internet services has grown exponentially in recent years [

1]. Accessibility has become widespread and affordable; for example, in the USA, the lowest cost of internet access is around

$20.00 per month [

2]. However, public access to free internet, although convenient, comes with security risks that should not be overlooked. As more people use email as a primary communication method between services, clients and organizations. More cybersecurity risks and attempts have risen too, even though there are many layers of security while using an email there is also a lot of threats that can really compromise sensible information if effective. Among these, phishing is one of the most prevalent tactics used by malicious actors to obtain sensitive or critical information [

3,

4]. Phishing attacks exploit social engineering techniques, manipulating victims to gain their trust and ultimately extract information. In 2023, these phishing attacks have caused a

$18.7 million financial loss due to several incidents according to different complaints [

5]. Such attacks often result in identity theft and unauthorized access to privileged accounts linked to the victim’s email or other compromised personal data. Despite the evolution of security and cybersecurity laws created internationally to avoid selling stolen consumer data this is something easily accessible nowdays[

6]. According to the 2023 Verizon Data Breach Investigation Report, social engineering attacks, such as phishing, now account for 12% of the most common cyberattacks. This technique was used in conjunction with other techniques such as stolen credentials and vulnerability exploits to compromise the security of an infrastructure. [

7].

Email serves as the entry point for accessing numerous online services, acting both as a communication tool and, in many cases, an authentication mechanism. This can be done by following easy steps while developing an app, making it easier to access it later when you have access to the linked account. This approach is highly popular nowadays due to the simplicity and convenience it offers [

8,

9]. But, since email access is typically password-protected, attackers can exploit weaknesses through dictionary attacks if sufficient user information is available. According to the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG), phishing attempts have surged in recent years, with over 1.02 million attacks recorded in the first quarter of 2022 alone [

10]. These attempts have also evolved in sophistication, extending beyond traditional methods to target users through social media, SMS, and other platforms [

11]. Phishing continues to grow rapidly as an efficient method for exploiting user trust and gaining unauthorized access to sensitive data.

Phishing attacks exploit social engineering by impersonating trusted entities such as banks, businesses, online stores, government agencies, and even healthcare organizations. In actuality, one of the most used methods to detect phishing in mail applications is by text processing and analyzing the content of these emails [

12,

13]. Advanced machine learning techniques such as CNNs have proven to be effective methods for detecting phishing emails and reducing false positives [

14]. By implementing this solution, we can drastically reduce the number of users who click on malicious links or provide personal information to phishers [

15]. Normally, this step prevents the possibility of being exposed to malware or spyware that can be injected into the user’s system, potentially leading to access to personal information or even full control of the system [

16]. By keeping the user and the phisher apart, we aim to ensure that users do not run unnecessary risks, thereby enhancing their overall online security [

17].

2. Objectives

Compare the performance of traditional models and transformer models in the email classification task for phishing and non-phishing labels, evaluating their efficacy using quantitative metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy.

Explore the enhancements brought by the implementation of transformer models in text classification tasks through an analysis of classification accuracy and their ability to process complex and diverse content.

Conduct a thorough analysis of the instances of failed classifications performed by both traditional models and transformer models. By identifying recurring patterns and root causes of errors, this objective aims to propose actionable improvements and refinements for future phishing detection methodologies, enhancing their effectiveness and reliability.

3. Related Work

Phishing, a social engineering attack that gained traction with the growth and adoption of the internet worldwide, has been the focus of numerous studies that approach this problem from various perspectives: user awareness, server- and client-side solutions, and deep analysis of the composition of phishing emails and their effectiveness against users. The following section will briefly explain these approaches by analyzing websites, links, and email content, with the objective of highlighting the differences and advantages of each popular method.

3.1. Analysis of Phishing Websites

This approach employs methodologies such as heuristic and machine learning methods with traditional models to detect phishing websites. Heuristic strategies determine whether a website is phishing based on its textual content by performing a comparative analysis with legitimate websites. The machine learning approach also examines the content and features of a website but relies on a pre-trained model for classification. Although significant results were found in these studies, they were limited due to the small sample size in the dataset [

18].

3.2. Analysis of Phishing URLs

This approach utilizes machine learning with traditional models to classify phishing URLs, considering features such as URL composition, anomaly detection, analysis of HTML and JavaScript scripts within the URL, and domain name analysis. Each of these studies demonstrated significant precision and effectiveness. It is anticipated that incorporating SDN and blockchain technologies will offer a different approach for detecting these URLs and achieving improved results [

19].

3.3. Analysis of The Content of Phishing Emails

In this study, phishing email detection is often considered a subcategory of spam detection, using publicly available or self-curated datasets to train traditional classification models, where Decision Trees and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) generally show the best results, depending on the training and testing datasets [

20,

21]. Another recently introduced approach is using Natural Language Processing (NLP) for lexical and orthographic analysis to categorize emails. Researchers also employ intent and sentiment analysis for categorization. One major challenge with this approach is the maximum number of tokens a transformer-based model can handle, which can be mitigated by splitting text into smaller sub-tokens; however, this can affect context and accuracy [

22].

Despite these advancements, the problem continues to evolve over time. This study aims to contribute to the foundation of phishing detection by conducting a comparative analysis between traditional and transformer-based models, with the goal of developing a comprehensive understanding of the most effective methods, parameters, and configurations for phishing detection, and to support ongoing efforts to enhance cybersecurity globally.

3.4. Deep Learning for Phishing Detection

One of the most effective implementations of phishing detection involves the use of deep learning models, as demonstrated by the study conducted by Altwaijry et al. This research compares Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) with architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), including Bidirectional GRUs, for phishing email detection. The 1D-CNNPD model, enhanced by adding recurrent layers, showed significant results on commonly used datasets such as Phishing Corpus and SpamAssassin [

23]. This approach shows notable improvements compared to traditional machine learning methods, which often face limitations when handling diverse phishing content.

3.5. Transformer Models for Phishing Detection

Phishing email detection with transformer models has gained prominence in recent years. These models excel at tasks involving the classification of text-heavy data such as emails. Transformer models like BERT and its variants are known for their high accuracy in identifying phishing emails. One study compared the performance of BERT with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for phishing email detection, achieving an impressive test accuracy of 96.1% for BERT. Atawneh and Aljehani explored deep learning models for phishing detection and developed a model combining BERT and LSTM, which achieved an outstanding 99.61% accuracy on a balanced dataset that included Enron emails as non-phishing examples [

24].

When exploring the applications of transformer models for classification tasks like phishing detection, certain models consistently stand out. For example, using BERT variants, Jamal et al. (2023) implemented spam and phishing email detection with transformer models like distilBERT and RoBERTa to reduce complexity while maintaining precision and accuracy. They achieved 98.7% precision and an overall accuracy of 98.3% [

25]. A noteworthy aspect of their study was the use of 8 epochs and an AdamW optimizer for each model.

Lastly, one of the most innovative approaches was introduced by Lee et al. (2020), who developed a prototype model specifically designed for detecting phishing and spam emails. CatBERT was created to resist adversarial attacks while maintaining accuracy [

26]. Although this model achieved 87% accuracy, its enhanced resilience to adversarial robustness makes it suitable for real-world implementation, even at the cost of a small reduction in accuracy.

From this exploration, it is evident that various approaches exist for phishing detection. Over the years, these methods have evolved. While heuristic methods like Decision Trees, KNN, and Support Vector Machines (SVM) have demonstrated moderate results, transformer models have gained popularity due to their ability to handle complex datasets and textual data from emails. Transformer models, particularly BERT and its variants, are now the preferred choice for phishing and email detection tasks due to their high accuracy and effectiveness in processing natural language and text classification. Although these models require higher computational resources compared to traditional methods, with refinements and a balanced performance, they are expected to become the mainstay of text classification and phishing detection in the future.

3.6. Datasets Used in Previous Investigations

During the preparations of this paper, it was started with an exploratory investigation in which there were two objectives. First, getting to know previous works and studies within this field and learning from them to be able to create a well-versed methodology of work. Second of all, to get to learn what datasets were used, what benign datasets they used for said studies, and how they performed in results. With this being said, the number of datasets achieved was 22, of which 10 had a previous article or small study via Kaggle in which they did an email classification task like phishing detection, fraud detection, or spam detection.

In these investigations, we can see the prevalent use of traditional models compared to transformer models. From these, we can mention Linear Regression with 94.08%, Sequential Search with 99.72%, Decision Trees with 96.77%, and Naive Bayes with 99.13%. These models showed to be effective and efficient in email classification tasks, and as said before, they have the benefit of being lightweight algorithms in terms of resources needed to use them. With this being said, even though the number of applications for transformer models is way lower compared to traditional models, it can be seen that overall RoBERTa has a recognizable appearance in the results obtained, showing that transformer models are well-versed in classification tasks that require contextual complexity, like phishing emails.

Table 1.

Performance of Different Models on Various Datasets.

Table 1.

Performance of Different Models on Various Datasets.

| Year |

Dataset Name |

Linear Regression |

Sequential |

Decision Trees |

Random Forest |

Naive Bayes |

CNN |

roBERTa |

| 2020 |

Email Classification |

94.08 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2023 |

Email Spam Classification |

0 |

86.2 |

0 |

0 |

79.87 |

0 |

78.57 |

| 2001 |

Enron Spam Data (No Code) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

95 |

0 |

0 |

| 2018 |

Fraud Email Dataset |

92 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

97 |

0 |

0 |

| 2023 |

Phishing Email Detection |

0 |

0 |

93.1 |

0 |

0 |

97 |

99.36 |

| 2023 |

Phishing-Mail |

0 |

0 |

92.82 |

0 |

0 |

99.03 |

96.81 |

| 2023 |

Pishing Email Detection |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2018 |

Pishing-2018 Monkey |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2019 |

Pishing-2019 Monkey |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2020 |

Pishing-2020 Monkey |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2021 |

Pishing-2021 Monkey |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2022 |

Pishing-2022 Monkey |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2018 |

Private-pishing4mbox |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2023 |

Spam (or) Ham |

0 |

99.72 |

0 |

0 |

96.9 |

0 |

0 |

| 2020 |

Spam Classification for Basic NLP |

0 |

81 |

96.77 |

0 |

98.49 |

0 |

98.33 |

| 2021 |

Spam Email |

0 |

96.67 |

97.21 |

0 |

99.13 |

0 |

0 |

| 2021 |

Spam_assasin |

0 |

0 |

98.6 |

98.87 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2024 |

Phishing Validation Emails Dataset |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2022 |

NLP Spam Ham Email Classification |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2022 |

Phishing Email Data by Type |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2023 |

Phishing-Mail |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

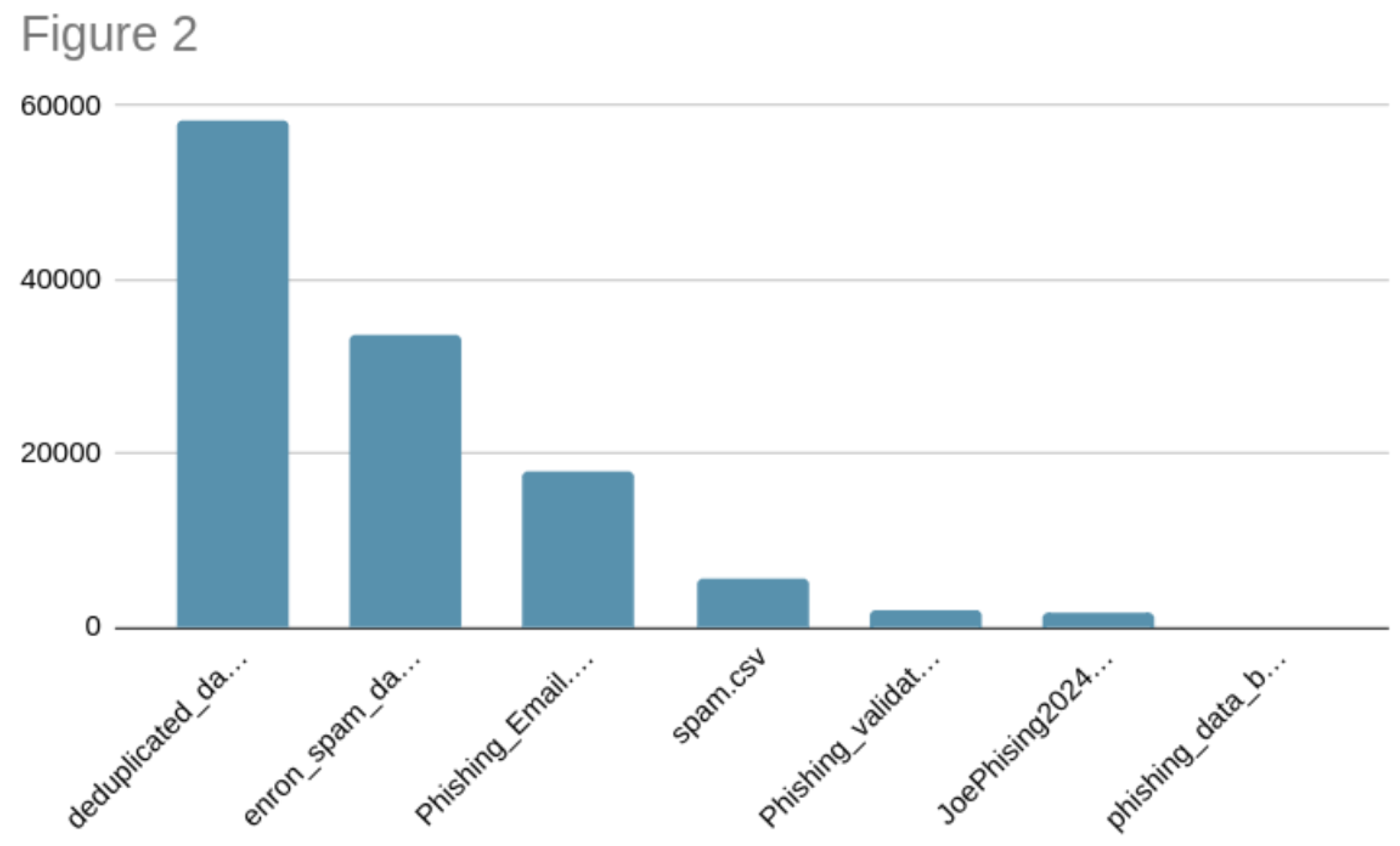

The data was collected manually from June 2023 to January 2024 from various online platforms, including posts about phishing on social media sites. This dataset consists of 119,148 emails, which were combined from multiple datasets and had their labels standardized in order to only include "phishing" and "not phishing" registries. To make this dataset more diverse, the Enron dataset was used to add a significant number of emails categorized as not phishing. This dataset is composed of the following datasets:

Phishing Email Detection

Phishing Email Data by Type

Email Spam Detection Dataset (classification)

Enron Spam Data

private-phishing4.mbox

phishing-2018 monkey

phishing-2019 monkey

phishing-2020 monkey

phishing-2021 monkey

phishing-2022 monkey

Phishing Email Data

self-promoted phishing data

phishing validation dataset

This dataset’s information and its source can be checked in more detail in

Appendix A.

This method is common in other studies, such as Sahingoz et al. (2019), where they consolidated a dataset between Phishtank and Enron to achieve more realistic results. They created a dataset to provide a realistic assessment of phishing. It is also important to highlight that Ugochukwu et al. (2023) emphasized the importance of utilizing recent phishing emails due to the evolution of phishing tactics over the years (2016-2023). This underscores the critical need to continually refresh datasets, allowing models to be trained with the most current phishing behaviors available.

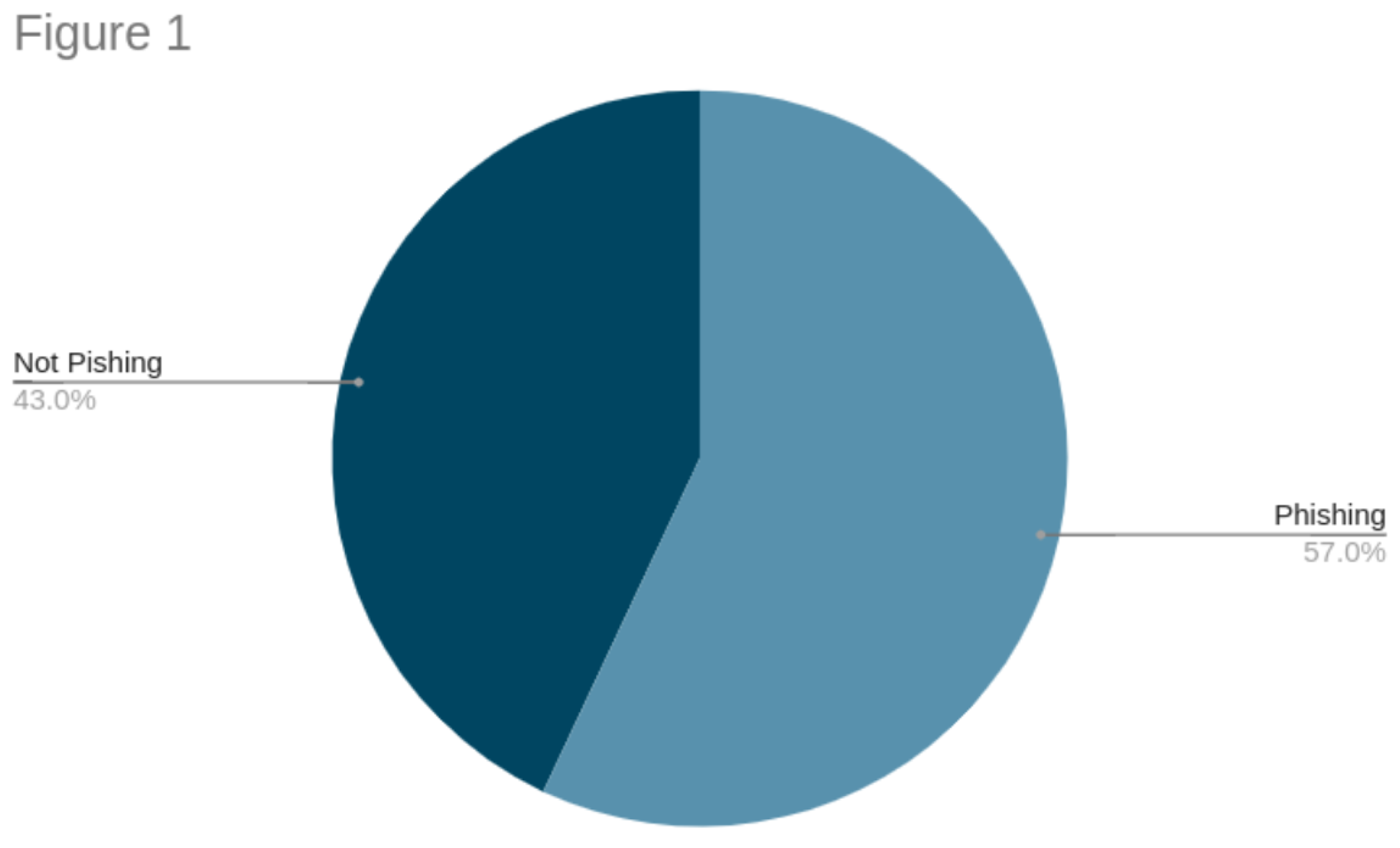

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the dataset. It can be observed that 57.0% of these emails are flagged as phishing, which is equivalent to 67,912 emails. The distribution of emails with their sources can be observed in

Figure 2.

The collected dataset is an important pillar for this investigation. In order to understand how this dataset was created and what data it contains, here is some statistical information for clarity (

Table 2).

4.2. Applied Models

Machine learning is a pivotal step in the advancement of artificial intelligence, enabling systems to learn, identify patterns, and make decisions with minimal human intervention. The creation of models is a fundamental aspect of this process, as it automates analytical model building, simplifying the use of these models to process complex datasets. Given that the main objective of this investigation is to compare traditional models and transformer models, it is essential to distinguish between them and understand their differences.

Traditional machine learning models, such as decision trees, support vector machines (SVMs), and neural networks, have been widely used for decades. These models were introduced at the foundation of artificial intelligence. Using statistical algorithms and data mining, the goal of these methods is to automatically detect patterns in data. This information can be used to make predictions about future data or classification. These models rely on well-established algorithms like linear regression, k-nearest neighbors (KNN), support vector machines (SVM), and ensemble methods like random forest and gradient boosting[

27,

28]. All these models have specific tasks they specialize in, even though they can be adapted and fine-tuned as needed.

For example, decision trees specialize in making decisions by considering previous data, using branches to separate decision pathways within the algorithm. SVM and linear regression are commonly used for classification tasks. The problem with these models is that they lack the ability to handle more complex problems, as they use numerical or statistical approaches and are less suited for tasks like natural language processing (NLP) and image processing[

29]. This makes transformer-based models especially useful for handling the evolving nature of phishing emails, which often adopt new tactics to bypass detection.

The traditional models used in this investigation are the following:

Logistic Regression: A linear model utilized for binary classification. It uses probability to determine if the given data can be classified into a particular label.

Random Forest: A model that uses decision trees for training and learning. After creating these decision trees, it utilizes predictions to improve the precision of the responses.

Support Vector Machine (SVM): A model that classifies data by determining which hyperplane best separates the classes in the feature space.

Naive Bayes: A statistical model that uses Bayes’ theorem with the assumption of independence between features. It works well with large datasets.

Transformer models, introduced in 2017, represent a significant advancement in the field of machine learning. They are a specific architecture of encoder-decoder models that utilize a unique attention mechanism to derive dependencies between input and output. Initially designed for tasks like language translation, transformer models have demonstrated remarkable versatility. The key innovation of transformers is their ability to use attention as the sole mechanism for understanding and generating sequences, which has proven particularly powerful for natural language processing (NLP) tasks.

One of the primary reasons for the rapid adoption and success of transformer models in various NLP tasks is their capability for transfer learning. Pretrained transformer models can quickly and efficiently adapt to new tasks with minimal additional training, often requiring only fine-tuning with a smaller dataset. This adaptability has allowed transformers to dominate numerous NLP leaderboards and extend their applicability beyond language tasks to areas such as computer vision, audio processing, and even complex games like chess and mathematical problem-solving.

The impact of transformer models on the field of machine learning has been profound, facilitated by the integration of these models into major AI frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow. Furthermore, the development and commercialization of libraries such as those provided by Hugging Face have made transformers accessible to a broad audience of researchers and practitioners[

30].

The transformer models used in this paper are the following:

BERT (bert-base-uncased): The BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) model is a pretrained model that utilizes bidirectional transformer logic, allowing it to analyze provided text data in both directions.

distilBERT (distilBERT-base-uncased): A compact version of BERT that maintains about 97% of its accuracy while consuming fewer resources.

XLNet (xlnet-base-cased): A model that generalizes BERT using permutation-based prediction, capturing dependencies without the constraint of conditional independence.

roBERTa (roBERTa-base): roBERTa (Robustly optimized BERT approach) is a variant of BERT that improves training logic, including more data and steps to enhance the robustness and precision of the model.

ALBERT (A Lite BERT): A lightweight version of BERT that reduces the model size through parameter sharing and embedding matrix factorization, maintaining high performance with fewer parameters.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Precision: Precision is the proportion of true positives among all the positive predictions. It measures the accuracy of the positive predictions made by the model.

Recall: Recall is the proportion of true positives among all the actual positive data. It measures the model’s ability to capture all the positive samples.

F1-Score: The F1-Score is obtained using both recall and precision. It provides a balanced measure considering both values, offering a single metric that reflects how well the model handled imbalanced data.

Accuracy: Accuracy is the proportion of correct predictions among all the predictions made by the model.

True Positive Rate (TPR): TPR is another term for recall. It represents the proportion of actual positives correctly identified by the model.

False Positive Rate (FPR): FPR represents the proportion of actual negatives incorrectly classified as positives by the model.

4.4. Experiment Setup

In this study, we approach phishing detection by analyzing the content of emails and training traditional models such as Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Naive Bayes, alongside transformer models such as distilBERT, BERT, XLNet, roBERTa, and ALBERT. The objective is to compare these results and determine which model (traditional or transformer) is most effective for this phishing classification task.

The compiled dataset was divided into training and evaluation splits. The training split consists of 30% of the dataset, which is 35,744 registries, while the remaining 70% of the dataset consists of 83,404 registries. This split was chosen to simulate a real-world scenario where the proportion of verified phishing emails can be really small in comparison to the whole dataset. This intentional choice aims to evaluate the learning effectiveness of models with limited training data. It also establishes a baseline for scenarios where correctly labeled phishing emails are scarcer, particularly in languages other than English. A series of 5 runs was performed for each model, the metrics were saved for each run. The averages are the ones presented and discussed in this document to ensure robustness and minimize the effects of variations in performance. It is important to note that no shuffle was applied during the train-test split to maintain the original order of the data. This ensures that each run uses the same split for training and evaluating, so that the variation in the metrics are only due to model’s performance and not to differences in the data distribution.

4.4.1. Data Pre-Processing

For traditional machine learning models, the data preprocessing involved the following steps:

Text Filtering: Special characters, non-alphabetic values, and unnecessary symbols were removed. Additionally, the text was normalized by converting all characters to lowercase.

Tokenization and Vectorization: The text was transformed using a two step process. First a Bag of Word (BoW) representation was created, where each value is converted into a fixed-length vector based on term frequencies in the vocabulary. After this step the terms frequencies were weigthed using TF-IDF(Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency). This technique assigns weights to words based on their frequency and relevance within the dataset, helping capture the importance of individual terms in the context of the entire corpus. The implementation uses scikit-learn’s TfidfVectorizer, which internally combines both BoW and TF-IDF transformations[

31].

For transformer models, the same initial text filtering process was applied. However, since tokenization was handled by the pre-trained HuggingFace Tokenizer, no additional preprocessing steps were necessary.

While one might consider using the same tokenization method across both systems for experimental consistency, we deliberately maintained distinct preprocessing pipelines for each approach based on their architectural differences. Traditional machine learning models like our TF-IDF based system are designed to work with simple word-level tokenization and bag-of-words representations, which form the foundation of their feature extraction process. In contrast, transformer models use subword tokenization like WordPiece, BPE or SentencePiece, that captures more nuanced semantic relationships and handles out-of-vocabulary words more effectively. Enforcing transformer tokenization on traditional systems would not only be computationally inefficient but could also introduce noise in the feature representation, as these systems aren’t designed to leverage the sophisticated token relationships that transformers utilize. Our methodology therefore evaluates each model type using its established best practices, providing a more realistic comparison of their practical performance capabilities[

32].

4.4.2. Traditional Machine Learning Model Parameters

To optimize the performance of the traditional models, a library for hyperparameter search was implemented using GridSearchCV. This process systematically tests combinations of hyperparameters and selects those that yield the best performance according to the evaluation metric, in this case, f1-macro.

The following outlines the models used and the parameters evaluated:

4.4.3. Transformer Model Parameters

-

Model Names:

- -

distilBERT-base-uncased

- -

bert-base-uncased

- -

xlnet-base-cased

- -

roBERTa-base

- -

alBERT-base-v2

-

Training Settings:

- -

Tokenizer: AutoTokenizer from Hugging Face’s transformers library.

- -

-

Dataset: EmailDataset class defined with:

- *

Texts and labels from the dataset.

- *

Tokenizer for encoding texts with special tokens, padding, and truncation.

- -

Optimizer: AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 2e-5.

- -

Device: Utilizes CUDA if available, otherwise CPU.

- -

Epochs: 3

-

Model Evaluation:

- -

Batch Size: 16 for both training and testing DataLoader.

- -

Loss Function: Cross-entropy loss.

- -

Metrics: Classification report with precision, recall, F1-score, and support.

4.5. Results and Discussion

4.5.1. Traditional Machine Learning for Phishing Email Detection

In this work, we evaluated the dataset using a range of traditional machine learning and transformer models for phishing detection, utilizing metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. Support Vector Machine (SVM) stood out from the other traditional models with the highest accuracy of 0.9876, exhibiting balanced precision, recall, and F1-scores in both phishing and non-phishing scenarios. Additionally, Random Forest and Logistic Regression performed quite well, exhibiting accuracy levels of 0.9802 and 0.9845, respectively, as well as somewhat lower but still excellent recall and precision scores. Naive Bayes was efficient, but its accuracy was lower at 0.9644 due to its lower recall for phishing scenarios.

Table 3.

Results for Traditional Models.

Table 3.

Results for Traditional Models.

| Model |

Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

Accuracy |

| Logistic Regression 6 |

Phishing |

0.9788 |

0.9850 |

0.9819 |

0.9845 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9888 |

0.9841 |

0.9864 |

|

| Random Forest |

Phishing |

0.9752 |

0.9787 |

0.9769 |

0.9802 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9840 |

0.9813 |

0.9827 |

|

| Support Vector Machine |

Phishing |

0.9820 |

0.9892 |

0.9856 |

0.9876 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9919 |

0.9864 |

0.9891 |

|

| Naive Bayes |

Phishing |

0.9831 |

0.9329 |

0.9573 |

0.9644 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9516 |

0.9880 |

0.9695 |

|

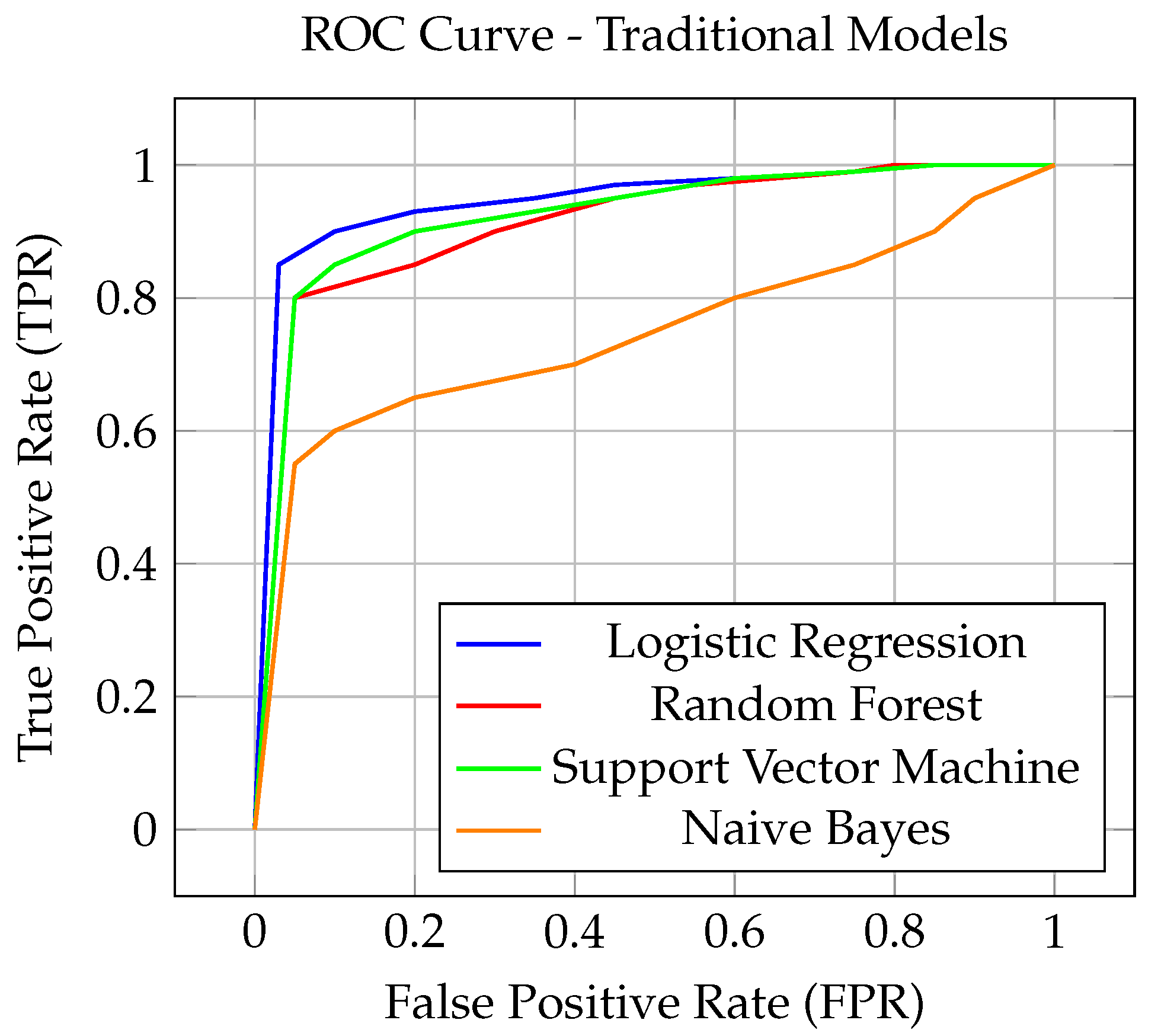

As seen in

Figure 3, the performance of traditional models shows clear differences in their ability to distinguish between phishing and non-phishing emails. Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machine exhibit similar behavior, maintaining a strong true positive rate (TPR) while keeping false positive rates (FPR) relatively low across various threshold values. Among these, Logistic Regression slightly edges out others in terms of maintaining a higher TPR with lower FPR, showcasing better sensitivity. However, Naive Bayes underperforms in comparison to the other models, showing higher variability in its FPR, despite maintaining competitive precision. This could be attributed to Naive Bayes’ strong assumptions about feature independence, which may not align as well with the dataset characteristics.

With these evaluations, we can infer that traditional models are capable of delivering high-performance results with their ability to generalize and simplify complex data structures. However, due to the cost-efficiency and easy implementation of these traditional models, the results are highly valuable in implementations where there may be a constraint on computational resources.

4.5.2. Transformer-Based Machine Learning for Phishing Email Detection

For transformer models, roBERTa-base demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving the highest accuracy of 0.9943, with high precision and recall scores for both classes. BERT-base-uncased followed with an accuracy value of 0.9911. distilBERT-base-uncased also performed significantly well, achieving an accuracy of 0.9899, while ALBERT-base-v2 had an accuracy of 0.9881. XLNet-base-cased followed closely, with an accuracy of 0.9884.

Table 4.

Results for Transformer Models.

Table 4.

Results for Transformer Models.

| Model |

Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-Score |

Accuracy |

| distilBERT-base-uncased |

Phishing |

0.9933 |

0.9890 |

0.9911 |

0.9899 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9853 |

0.9911 |

0.9882 |

|

| bert-base-uncased |

Phishing |

0.9947 |

0.9897 |

0.9922 |

0.9911 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9863 |

0.9929 |

0.9896 |

|

| xlnet-base-cased |

Phishing |

0.9828 |

0.9971 |

0.9899 |

0.9884 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9961 |

0.9768 |

0.9863 |

|

| roBERTa-base |

Phishing |

0.9928 |

0.9974 |

0.9951 |

0.9943 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9964 |

0.9903 |

0.9934 |

|

| alBERT-base-v2 |

Phishing |

0.9939 |

0.9853 |

0.9896 |

0.9881 |

| Not Phishing |

0.9806 |

0.9919 |

0.9862 |

|

One notable observation is the consistently high performance for all transformer models, with accuracy normally scoring above 0.9881 across all models. This suggests that transformer-based models, in particular BERT and its variants, are highly effective at distinguishing phishing from non-phishing emails.

Although distilBERT and ALBERT have slightly lower scores compared to the other models implemented in this study, with accuracy values of 0.9899 and 0.9881, these values should not be diminished. distilBERT, in particular, stands out since it is a distilled version of BERT, being about 60% faster than normal BERT while still managing to achieve a similar score. This trade-off between accuracy and speed of analysis makes it an excellent choice for implementations that need a lightweight model and can be easily deployed without requiring significant resources.

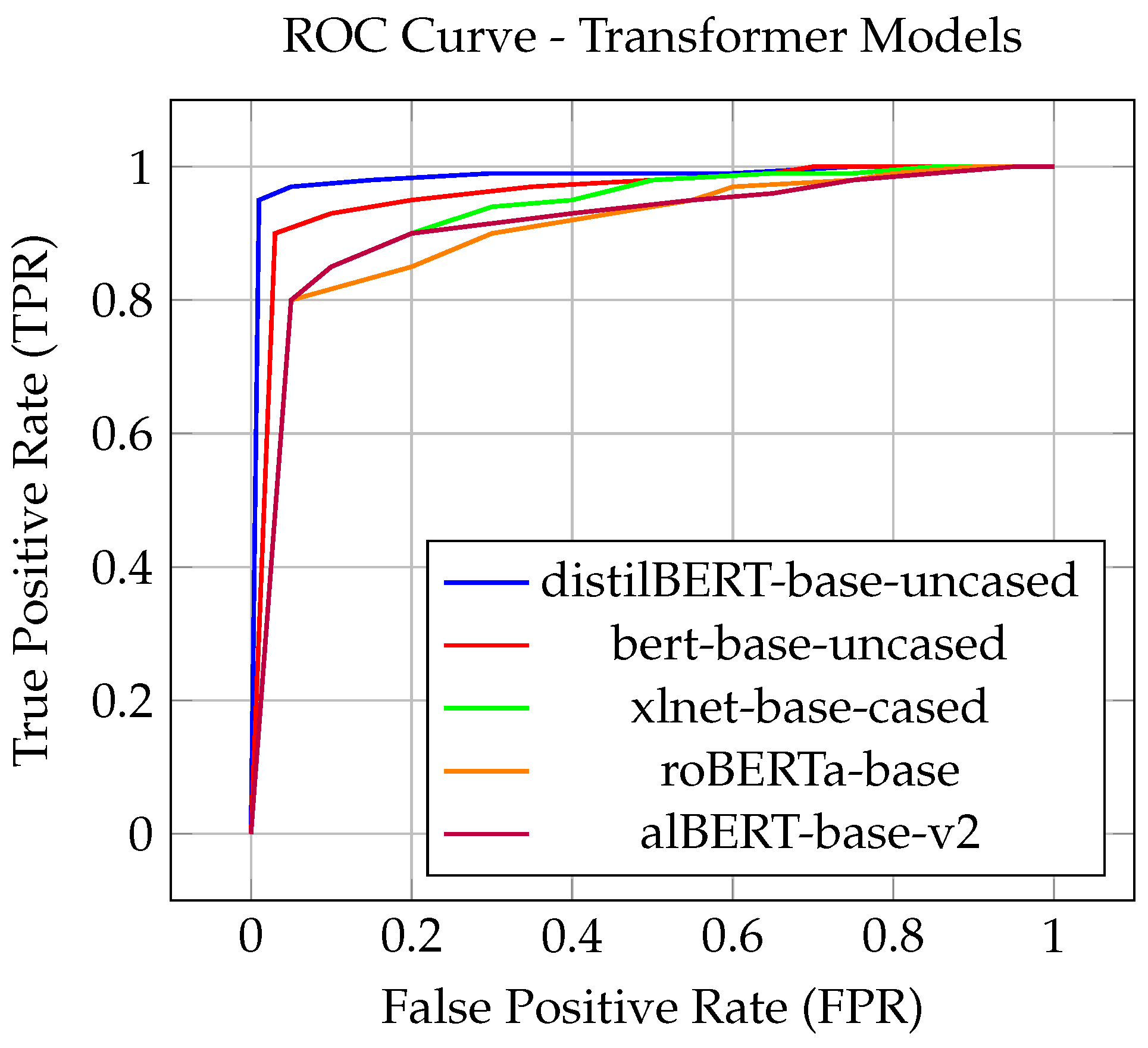

As shown in

Figure 4, it can be observed that distilBERT demonstrates a significant lead in comparison with other models by maintaining a high TPR and keeping the FPR relatively low. This indicates that it is able to classify phishing emails correctly with a low number of false positives. BERT also shows strong performance with slightly better values compared to the three remaining ones. roBERTa, which had the best overall accuracy in this test, shows worse ROC compared to distilBERT and BERT, suggesting that it has a higher value of false positives in comparison.

By understanding all the results and studying the intrinsic characteristics of each model, organizations can make an informed decision when selecting a model for phishing email detection, taking into account variables like accuracy, computational cost, and scalability.

4.6. Analysis of Failed Predictions

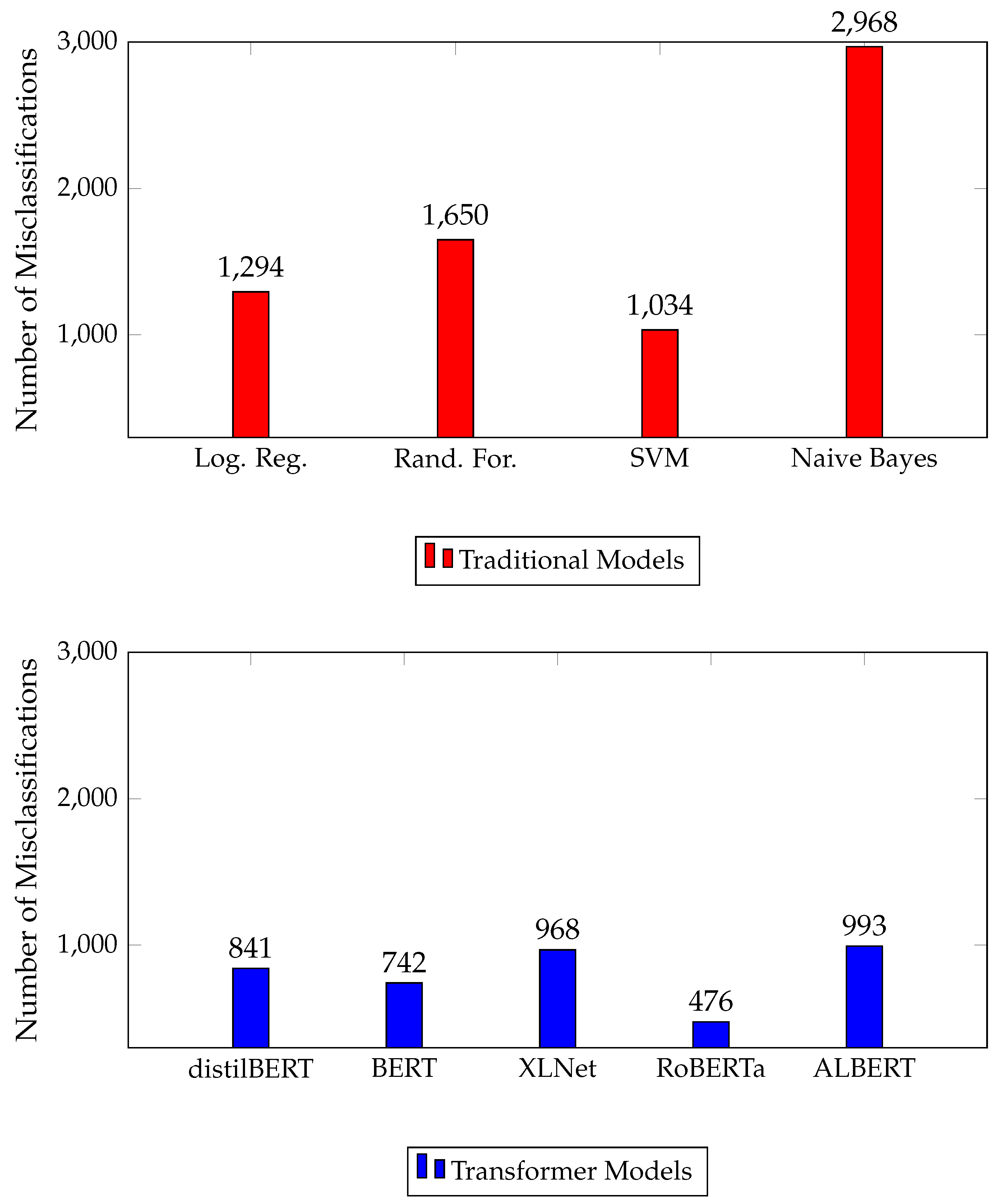

After taking into account the numerical values of the results obtained in these papers, we also saved all the failed predictions per model in CSV format for further analysis. These failed records were saved in a different file in order to analyze them in depth. In

Figure 5, we can see a summary of the obtained results in quantitative values of the misclassifications during the evaluation step of each model.

As it can be seen, there is a significant gap in efficiency and accuracy when comparing these results. Traditional machine learning models have an average of 1737 registries misclassified. On the other hand, transformer models have an average of 804 registries misclassified. With this information, we can infer that transformer models clearly outperform traditional models by having 53.7% fewer misclassifications. This reduction in failed predictions highlights the superior performance of transformer models, making them a reliable choice for email classification tasks.

4.6.1. Error Analysis for Traditional Model

After reviewing the failed prediction cases in the classification task for emails, there were some noticeable patterns that can impact its precision. First of all, grammatical errors and informal types of writing are often classified as non-phishing. This error happens due to the low weight of such words, misspells, and also the lack of context understanding for traditional models. Sentiment analysis techniques could improve the accuracy of text classification tasks like phishing detection.

Another factor that affects traditional models is the handling of HTML-formatted content, which is often detected as non-phishing. This pattern may be due to the lack of examples with similar content in the training dataset used, limiting the model’s ability to identify phishing emails that contain HTML code or malicious code.

Another important observation is that, in some cases, emails contained mixed-language content, where both English and other languages were used. The use of leetspeak (a form of writing where letters are replaced by symbols or numbers) also causes misclassification errors as non-phishing. This is also due to the lack of proper training for these variations.

As shown in the

Table 5 Traditional models struggle with grammatical errors, mixed languages, leatspeak, and HTML code in emails, highlighting the need of enhanced or fine-tuned datasets for training and parameter adjustments for these models to better detect these characteristics.

4.6.2. Error Analysis for Transformer Models

Even though transformer models have significantly more accuracy compared to traditional models, they still have a significant number of miscategorized emails. A recurring pattern is that the emails contained common words like “Click here” or “Password,” and these emails were wrongfully categorized as phishing emails. This only reflects how rigid a pattern-based classification approach is.

The use of leetspeak and phishing URLs also confuses transformer models, as they are not trained to detect this type of writing, leading to misclassification, as shown in

Table 6. Also, the use of HTML-based content is another issue that appears to be misclassified as non-phishing.

Lastly, emails with formal or lengthy formats, including multiple line breaks, are often classified as phishing, suggesting that the model might have learned presentation or layout patterns that do not necessarily represent fraudulent intent. It would be essential to add these last points in a greater number of registries for the training dataset so they could better reflect the current phishing methods and behavior.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

5.1. Conclusion

In this paper, we conducted an investigation centered in the detection of phishing emails via traditional models and transformer models used in machine learning. Achieve this by doing an exhaustive analysis of a created email dataset by collecting other diverse existing email datasets. We evaluated the effectiveness of various traditional models such as Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM, NB, and transformer models such as distilBERT, BERT, XLNet, roBERTa and ALBERT, using metrics like precision, recall, F1-Score and global precision.

Our analysis was based on a dataset consisting of 119,148 English-language email samples, which we strengthened by incorporating examples from various public sources. The results revealed that transformer models significantly outperformed traditional models. For example, roBERTa achieved the highest accuracy at 0.9943, with a high F1-score of 0.9951 for phishing detection, demonstrating its superiority in identifying phishing emails accurately. In contrast, traditional models like Logistic Regression and Random Forest showed slightly lower performance, with Logistic Regression achieving an accuracy of 0.9808 and an F1-score of 0.9832 for phishing detection.

XLNet and BERT also performed very well among transformer models, with accuracy of 0.9884 and 0.9911, respectively. In comparison, traditional models like SVM, with an accuracy of 0.9876, were still effective but did not match the precision of transformer models. The lowest-performing traditional model, Naive Bayes, had an accuracy of 0.9644 and struggled particularly with recall, misclassifying many phishing emails.

In our error analysis, we identified several patterns that traditional models struggle with. Grammatical errors, mixed-language content, and leatspeak were often classified as non-phishing, while HTML code and phishing URLs were not accurately detected. Transformer models showed similar difficulties with phishing URLs and certain formal email formats, leading to misclassifications. Addressing these weaknesses is crucial for improving the model’s performance.In summary this investigation demonstrates the effectiveness of transformer models in phishing detection and underscores the importance of detailed email content analysis to protect users from cyber threats.

5.2. Future Work

To further improve the results obtained in this study, future models should incorporate sentiment analysis techniques to detect social engineering tactics and to better understand the emotional tone and intent behind the email content. By identifying these elements, sentiment analysis could enhance the models ability to detect benign emails from phishing attempts. Improving the precision by being context-aware

Taking in account the results of this study, we propose developing a specialized NLP model for phishing detection. This model would take advantage of the transformer models and the inherited text processing techniques to accurately identify and filter phishing attempts text given information. We think that training a model that has good use of resources and has a significant preciseness can be applied and protect users from the ever-evolving phishing threat.

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A. Datasets Analized in This Paper

References

- Laudon, K.; Traver, C. E-commerce 2023: Business, Technology, Society; Pearson, 2023.

- Cellucci, N.; Moore, T.; Salaky, K. How Much Does Internet Cost Per Month?, 2024. Accessed: 2024-9-15.

- Al-Mashhadi, H.M.; Alabiech, M.H. A survey of email service; attacks, security methods and protocols. International Journal of Computer Applications 2017, 162.

- Tariq, U.; Ahmed, I.; Bashir, A.K.; Shaukat, K. A Critical Cybersecurity Analysis and Future Research Directions for the Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3). 2023 Internet Crime Report. https://www.ic3.gov/AnnualReport/Reports/2023_IC3Report.pdf, 2023. Accessed: 2024-08-25.

- Brody, R.G.; Mulig, E.; Kimball, V. PHISHING, PHARMING AND IDENTITY THEFT. Academy of Accounting & Financial Studies Journal 2007, 11.

- Verizon. 2023 Data Breach Investigations Report. https://www.verizon.com/about/news/2023-data-breach-investigations-report, 2023. Accessed: 2024-08-25.

- Altulaihan, E.; Alismail, A.; Hafizur Rahman, M.M.; Ibrahim, A.A. Email Security Issues, Tools, and Techniques Used in Investigation. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Google Developers. Authentication overview. https://developers.google.com/workspace/guides/auth-overview, n.d. Accessed: 2024-08-25.

- Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG). Phishing Activity Trends Report, Q1 2022. https://docs.apwg.org/reports/apwg_trends_report_q1_2022.pdf, 2022. Accessed: 2024-08-25.

- Naqvi, B.; Perova, K.; Farooq, A.; Makhdoom, I.; Oyedeji, S.; Porras, J. Mitigation strategies against the phishing attacks: A systematic literature review. Computers & Security 2023, 132, 103387. https://. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N. Social engineering as an evolutionary threat to information security in healthcare organizations. Jurnal Administrasi Kesehatan Indonesia Volume 2020, 8.

- Chanti, S.; Chithralekha, T. A literature review on classification of phishing attacks. International Journal of Advanced Technology and Engineering Exploration 2022, 9, 446–476. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S. Phishing Email Detection Using CNN.

- Alam, M.N.; Sarma, D.; Lima, F.F.; Saha, I.; Ulfath, R.E.; Hossain, S. Phishing Attacks Detection using Machine Learning Approach. 2020 Third International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT), 2020, pp. 1173–1179. [CrossRef]

- Milletary, J.; Center, C.C. Technical trends in phishing attacks. Retrieved December 2005, 1, 3–3.

- Hera, J. Phishing Defense Mechanisms: Strategies for Effective Measurement and Cyber Threat Mitigation 2024.

- Tang, L.; Mahmoud, Q.H. A survey of machine learning-based solutions for phishing website detection. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2021, 3, 672–694. [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.S.; Balasubaramanian, S.; Al-Kaabi, A.S.; Sharma, B.; Chowdhury, S.; Mehbodniya, A.; Webber, J.L.; Bostani, A. Analysis of the performance impact of fine-tuned machine learning model for phishing URL detection. Electronics 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.; Kaur, A.; Myneni, S. A review of generative models in generating synthetic attack data for cybersecurity. Electronics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D.; Nasiopoulos, D.K. Next-generation spam filtering: Comparative fine-tuning of LLMs, NLPs, and CNN models for email spam classification. Electronics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S.; Gaber, T.; Vadera, S.; Shaalan, K. A systematic literature review on phishing email detection using natural language processing techniques. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 65703–65727. [CrossRef]

- Atawneh, S.; Aljehani, H. Phishing Email Detection Model Using Deep Learning. Electronics 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Newaz, I.; Jamal, M.K.; Hasan Juhas, F.; Patwary, M.J.A. A Hybrid Classification Technique using Belief Rule Based Semi-Supervised Learning. 2022 25th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), 2022, pp. 466–471. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, K.; Hossain, M.A.; Mamun, N.A. Improving Phishing and Spam Detection with DistilBERT and RoBERTa. arXiv preprint 2023, [2311.04913]. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Saxe, J.; Harang, R. CATBERT: Context-Aware Tiny BERT for Detecting Social Engineering Emails, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CR/2010.03484].

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, 2006.

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2 ed.; Springer: New York, 2009.

- Batutin, A. Choose Your AI Weapon: Deep Learning or Traditional Machine Learning? https://shelf.io/blog/choose-your-ai-weapon-deep-learning-or-traditional-machine learning, 2023. Accessed: 2024-09-19.

- Amatriain, X.; Sankar, A.; Bing, J.; Bodigutla, P.K.; Hazen, T.J.; Kazi, M. Transformer models: an introduction and catalog, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2302.07730].

- learn Developers, S. TfidfVectorizer, 2024. Accessed: 2024-11-21.

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; Davison, J.; Shleifer, S.; von Platen, P.; Ma, C.; Jernite, Y.; Plu, J.; Xu, C.; Le Scao, T.; Gugger, S.; Drame, M.; Lhoest, Q.; Rush, A. Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations; Liu, Q.; Schlangen, D., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2020; pp. 38–45. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).