Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Easy integration into real-time applications by reducing computational resources, computational burden, and the complexity of its start-up.

- Adaptability of the SOH estimator to changes in battery behavior according to different applications.

- Utilization of generally available battery datasheet parameters and low-cost instrumentation for parametric estimation and validation of online SOH estimation (as well as state-of-charge (SOC) estimation).

- Versatility in modeling different battery technologies, considering implementation cost and applicability to battery management and optimization systems in engineering and research.

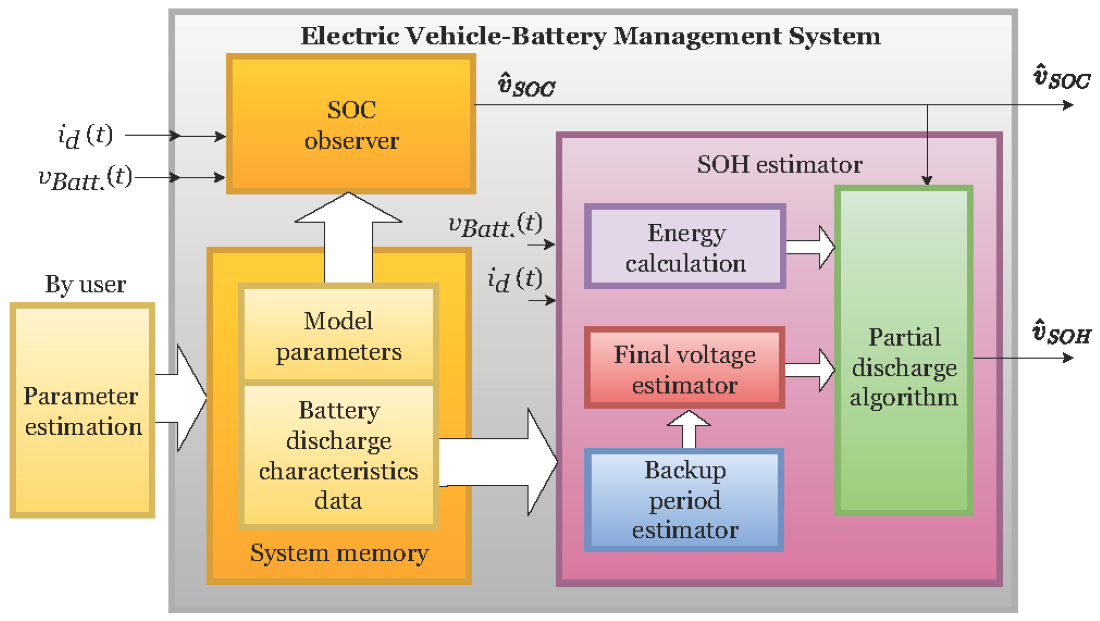

2. Proposed Real-Time SOH Estimator Based on a Partial Discharge Method

2.1. SOH Energy

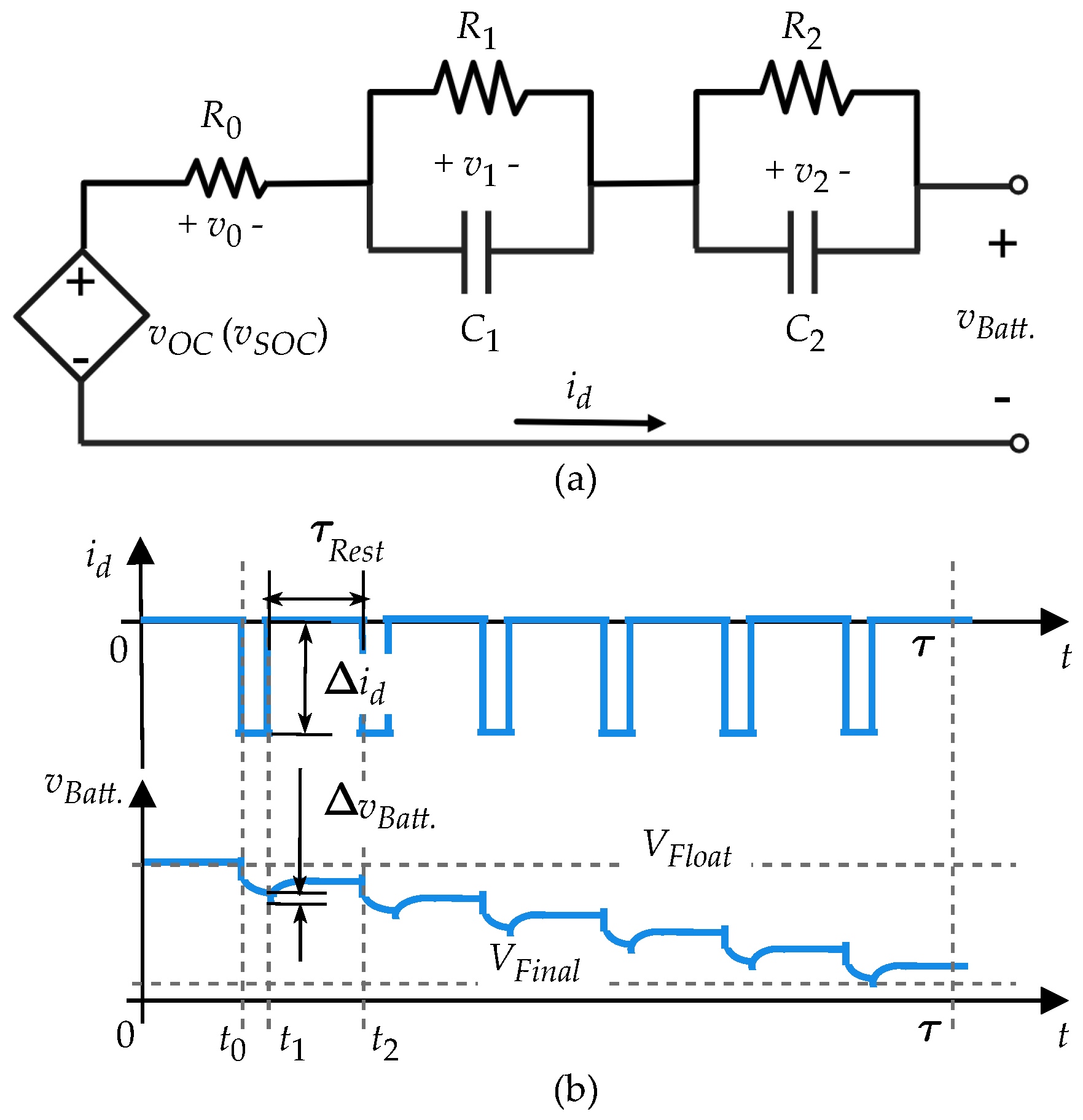

2.2. Partial Discharge Method

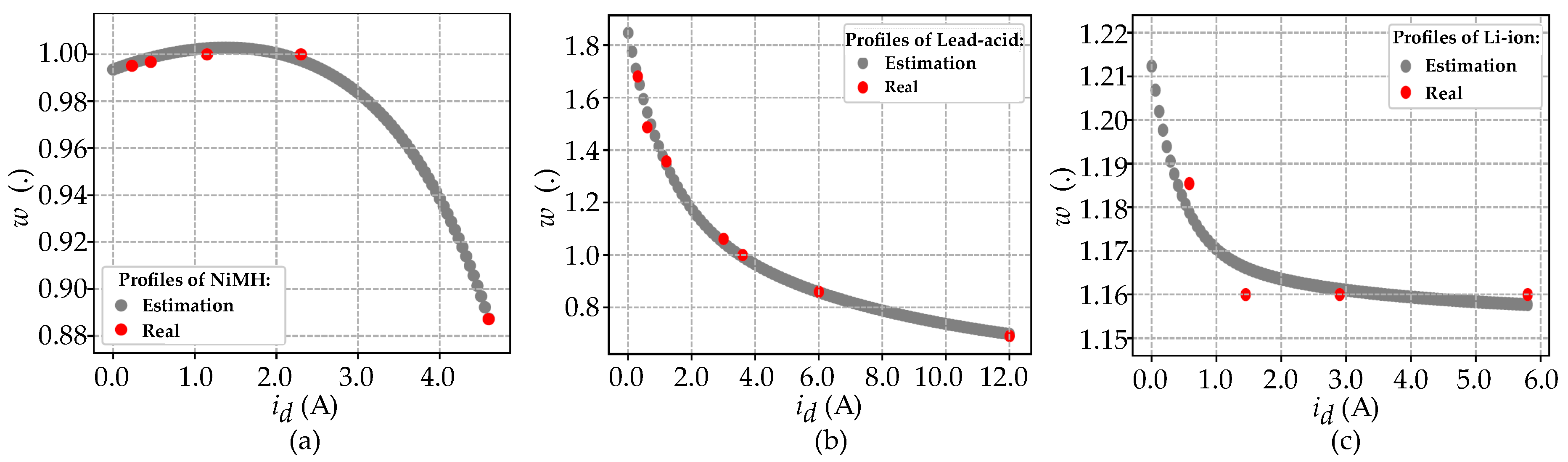

2.3. SOH Model Deduction

- A battery voltage level that indicates when the battery is fully charged and it is also used to indicate the battery voltage at the beginning of the discharge ; this value is defined as the float voltage and will be used as a constant because it is obtained from battery datasheet, and

- A battery voltage level that indicates when the battery is fully discharged (the battery voltage value at the end of the backup period ), which is known as the final voltage , and this voltage level changes for every constant current profile.

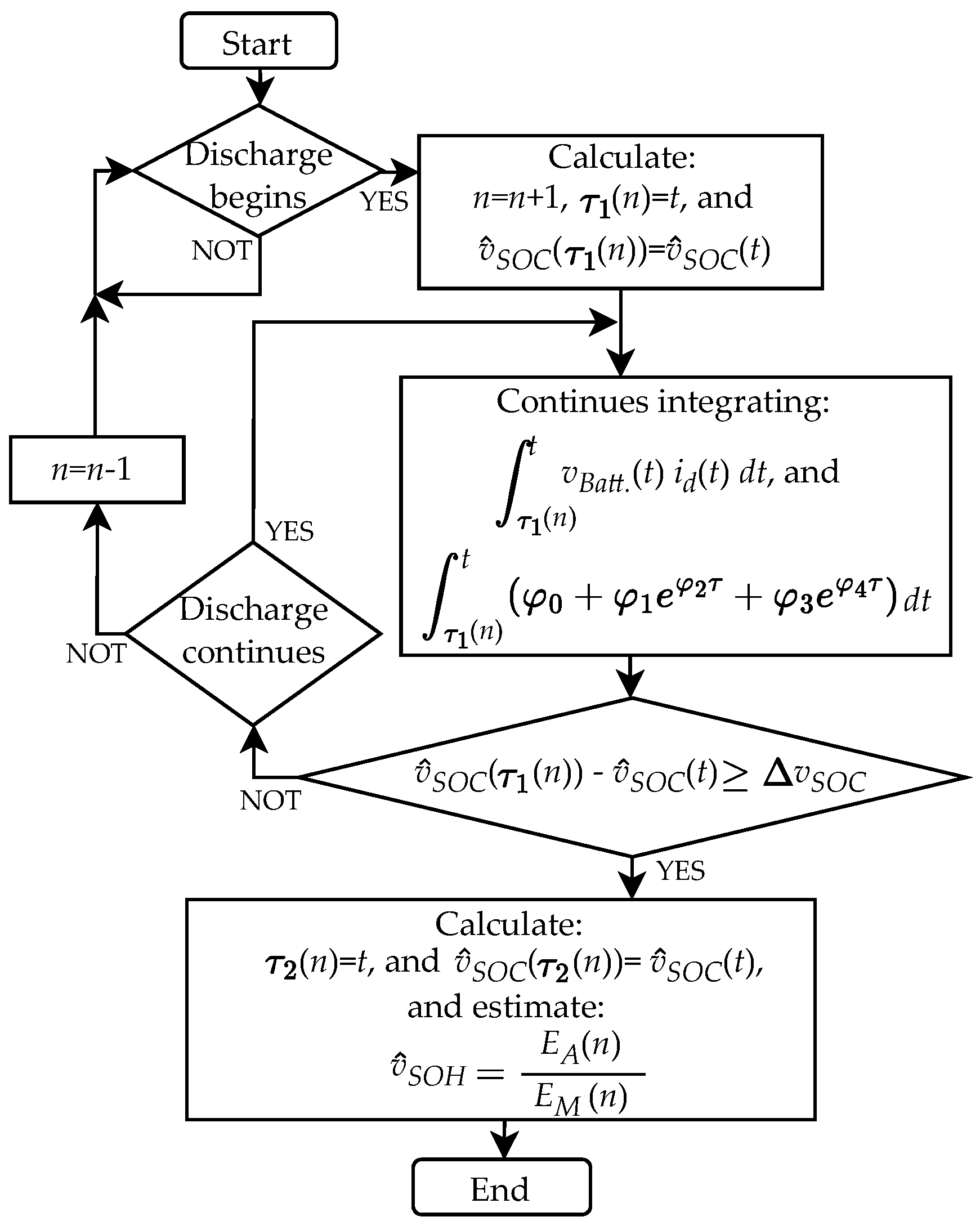

2.4. Algorithm for Real-Time SOH Estimation

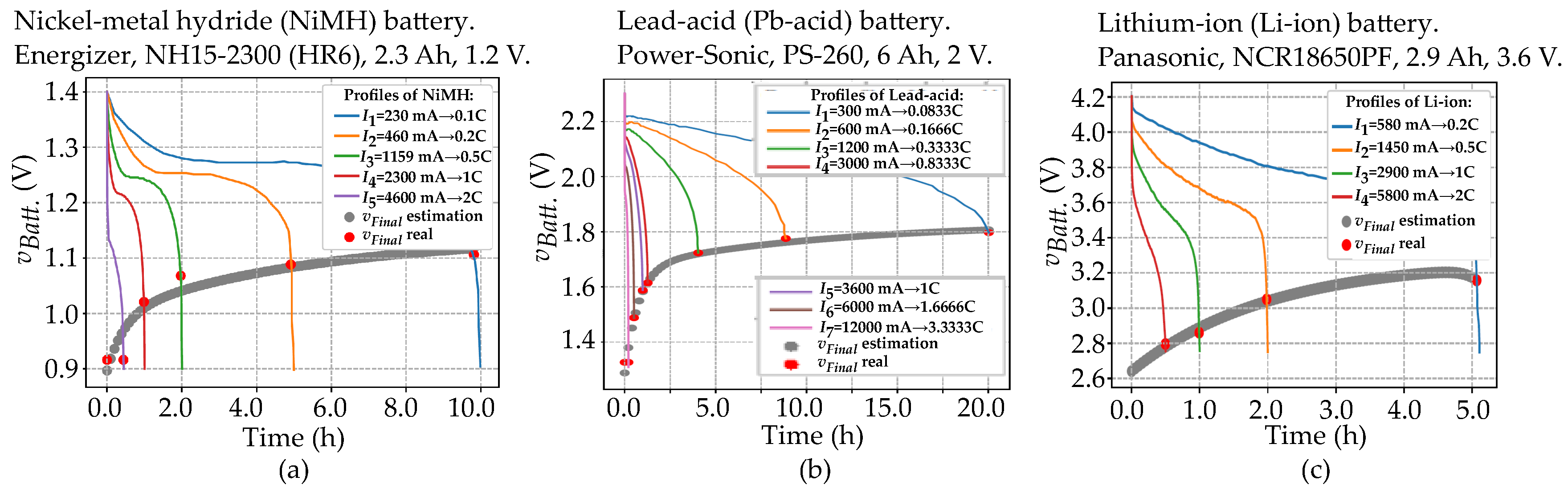

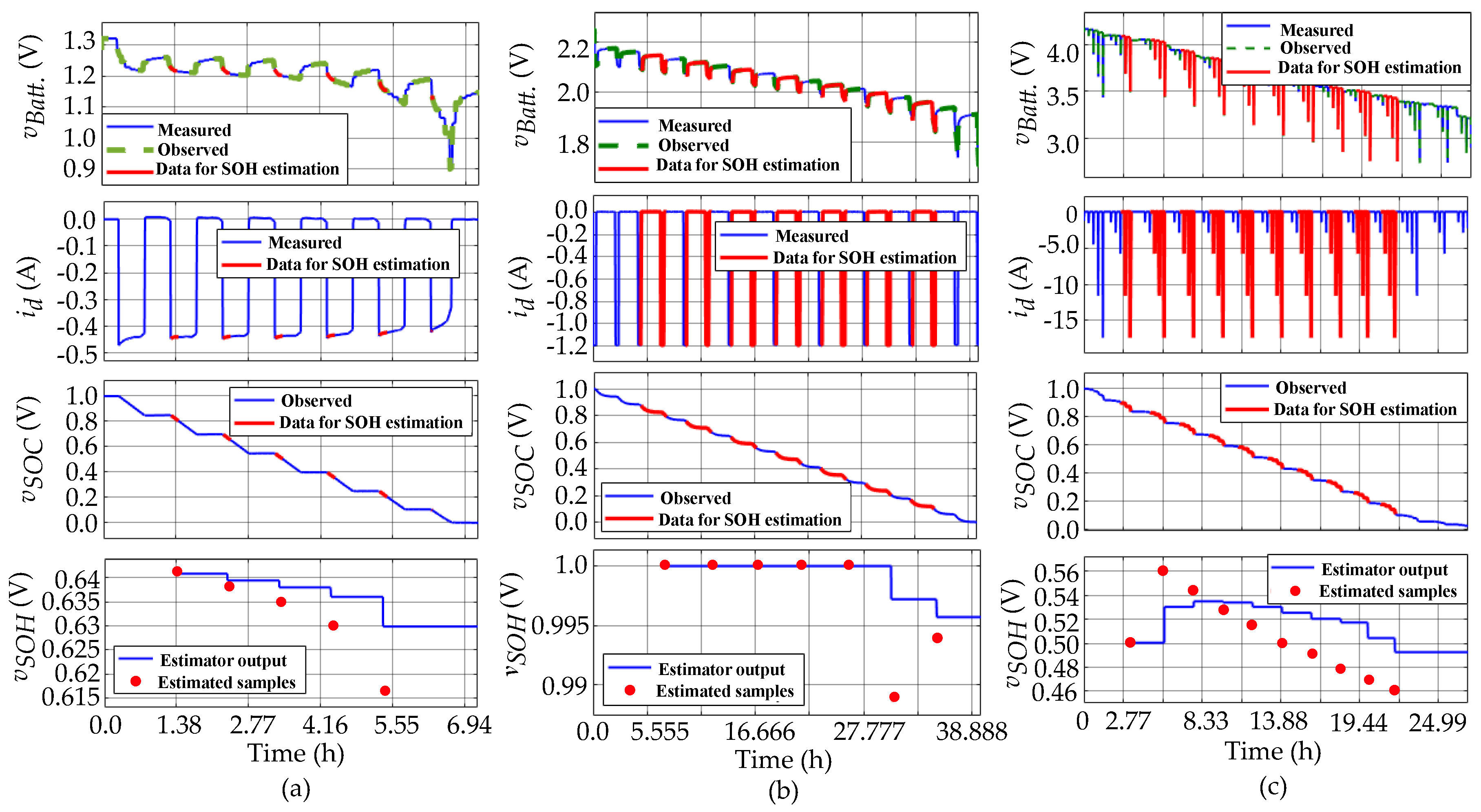

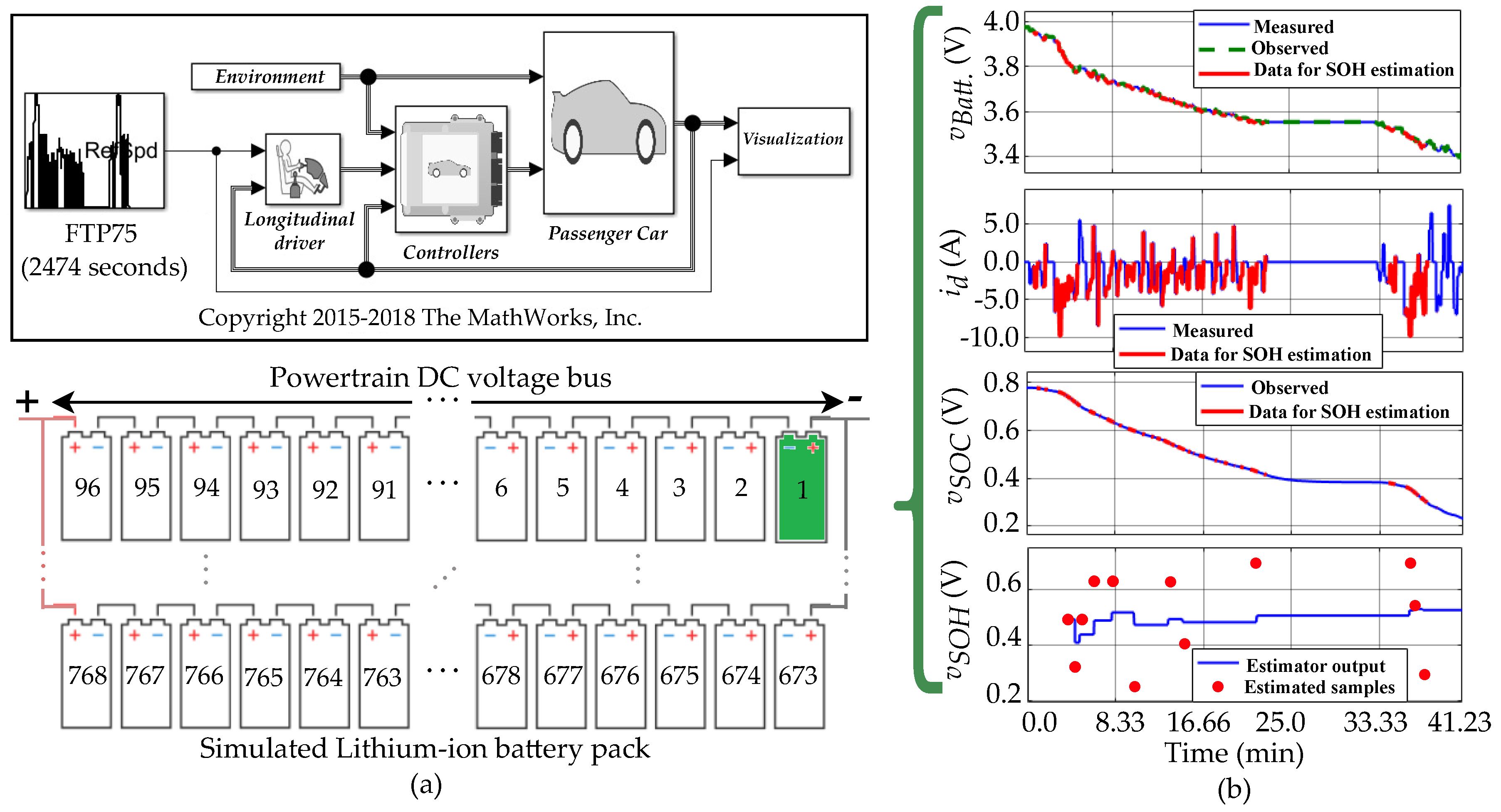

3. Test Results of the Proposed Method for Estimating SOH and SOC in Real-Time

- 1.

- An offline Simulink-MATLAB simulation is conducted to validate the SOH estimator, using the models of the three different battery technologies.

- 2.

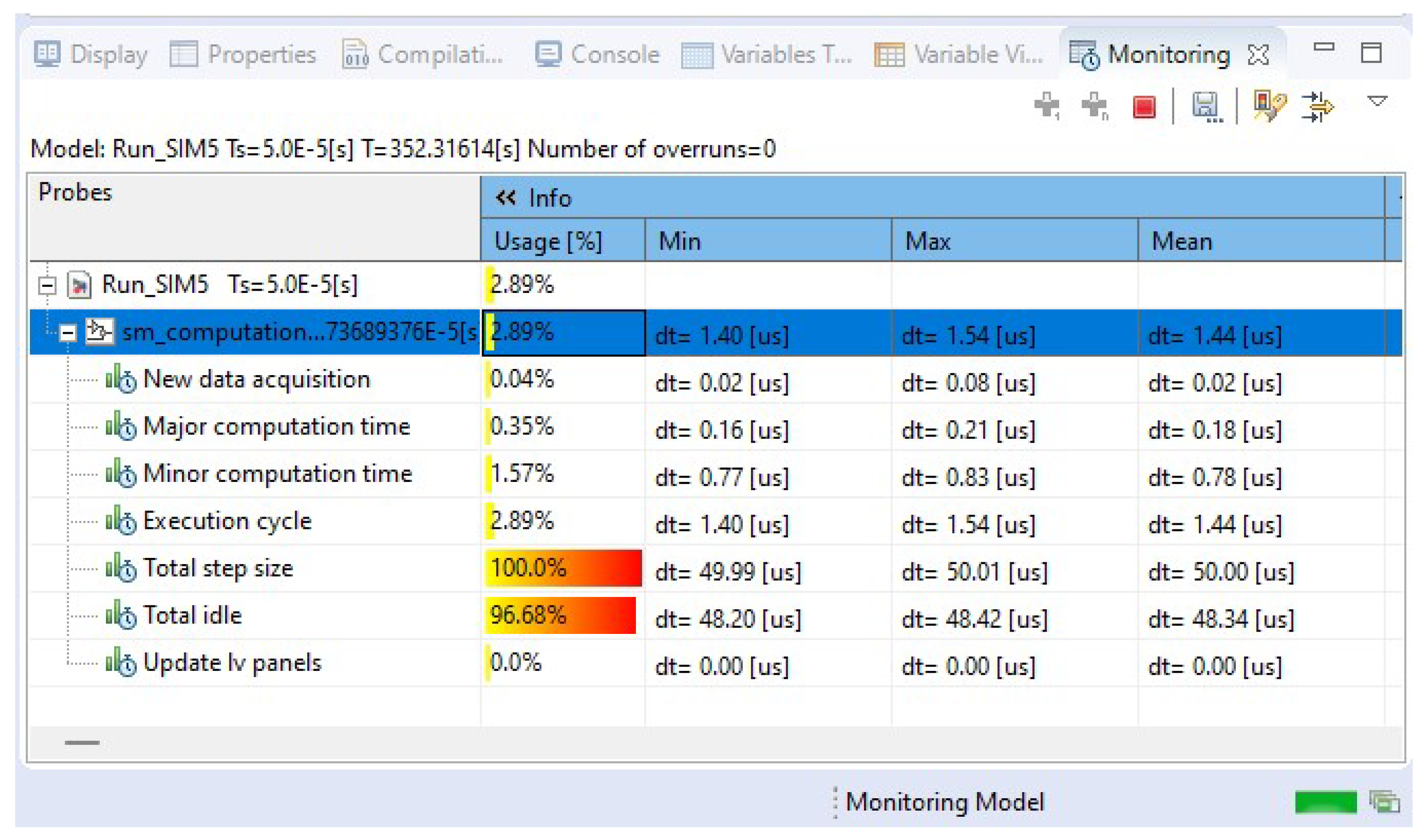

- A real-time simulation of an EV-BMS into the MIL environment on OPAL-RT is performed to validate the SOH estimation proposal by using the Lithium-ion battery model.

3.1. Simulation 1

3.2. Simulation 2

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| BMS | Battery Management Systems |

| CCM | Coulomb Counting Method |

| Com | Complex |

| DDM | Data-Driven Methods |

| DVA | Differential Voltage Analysis |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| ECM | Electrical circuit model |

| EVs | Electric Vehicles |

| EV-BMS | Electric Vehicles-Battery Management Systems |

| FL | Fuzzy Logic |

| GA | Genetic Algorithms |

| ICA | Incremental Capacity Analysis |

| IRM | Internal Resistance Measurement |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| Lim | Limited |

| Li-ion | Lithium-ion |

| Med | Medium |

| MIL | Model in loop |

| Mod | Moderately |

| NiMH | Nickel-methal hydride |

| OCV | Open-Circuit Voltage |

| Off | Offline |

| OM | Observer Methods |

| On | Online |

| Pb-acid | Lead-acid |

| PDM | Partial Discharge Method |

| PE | Peukert Equation |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SM | Shepherd’s Model |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| SOH | State of Health |

| UM | Ultrasonic Method |

References

- Hasan, M.K.; Mahmud, M.; Ahasan Habib, A.; Motakabber, S.; Islam, S. Review of electric vehicle energy storage and management system: Standards, issues, and challenges. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Peng, Q.; Che, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Teodorescu, R.; Widanage, D.; Barai, A. Transfer learning for battery smarter state estimation and ageing prognostics: Recent progress, challenges, and prospects. Advances in Applied Energy 2023, 9, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Rehm, M.; Karger, A.; Jossen, A. Capacity and degradation mode estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on partial charging curves at different current rates. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar, R.; Ramachandran, H.; Ali, S.H.M.; Jabbar, R. A Systematic Literature Review of State of Health and State of Charge Estimation Methods for Batteries Used in Electric Vehicle Applications. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Z.; He, J.; Yu, S. Lithium battery state-of-health estimation and remaining useful lifetime prediction based on non-parametric aging model and particle filter algorithm. eTransportation 2022, 11, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, G.; Zhen, D.; Gu, F.; Ball, A. A review on online state of charge and state of health estimation for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 5141–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. A review on health estimation techniques of end-of-first-use lithium-ion batteries for supporting circular battery production. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 94, 112406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, D.; Zhao, J.; Chu, Z.; Guo, D.; Eze, C.; Qu, X.; Lian, Y.; Burke, A.F. Battery health diagnostics: Bridging the gap between academia and industry. eTransportation 2024, 19, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamila, E.H.; Taoufik, N., A Review of the Estimation of State of Charge (SOC) and State of Health (SOH) of Li-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles. In Technical and Technological Solutions Towards a Sustainable Society and Circular Economy; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; chapter 1, pp. 519–541. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yan, Q.; Lin, F.; Yu, C.; Jiang, B.; Wei, X.; Yan, W.; Yang, Y. Advances in battery state estimation of battery management system in electric vehicles. Journal of Power Sources 2024, 612, 234781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, V.; Che, H.S.; Selvaraj, J.; Tey, K.S.; Lee, J.W.; Shareef, H.; Errouissi, R. State of Health (SoH) estimation methods for second life lithium-ion battery—Review and challenges. Applied Energy 2024, 369, 123542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, O.; Taskin, S.; Schaltz, E.; Acar Demirci, B. Review of battery state estimation methods for electric vehicles-Part II: SOH estimation. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, S.; Che, H.S.; Selvaraj, J.; Tey, K.S. State of health indicators for second life battery through non-destructive test approaches from repurposer perspective. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismero, A.; Nørregaard, K.; Johnsen, B.; Stenhøj, L.; Stroe, D.I.; Schaltz, E. Electric vehicle battery state of health estimation using Incremental Capacity Analysis. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.J.; Chen, K.C.; Su, T.W. Differential current in constant-voltage charging mode: A novel tool for state-of-health and state-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Energy 2024, 288, 129826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, A.M.; Şahin, M.E. Modeling and simulation of a series and parallel battery pack model in MATLAB/Simulink. Turk J. Electr Power Energy Syst 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.; Hasanien, H.; Alsaleh, I.; Ji, H.; Alassaf, A. State of health estimation of lithium-ion battery using dual adaptive unscented Kalman filter and Coulomb counting approach. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wen, C. An adaptive sliding mode observer for lithium-ion battery state of charge and state of health estimation in electric vehicles. Control Engineering Practice 2016, 54, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Lin, Q.; Huang, R. Non-Invasive Method-Based Estimation of Battery State-of-Health with Dynamical Response Characteristics of Load Surges. Energies 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Li, K.; Liang, F.; Yang, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. A novel state of health prediction method for battery system in real-world vehicles based on gated recurrent unit neural networks. Energy 2024, 289, 129918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lai, X.; Chen, Q.; Han, X.; Lu, L.; Ouyang, M.; Zheng, Y. Progress and challenges in ultrasonic technology for state estimation and defect detection of lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Materials 2024, 69, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camboim, M.; Moreira, A.; Rosolem, F.; Beck, R.; Arioli, V.; Omae, C.; Ding, H. State of health estimation of second-life batteries through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and dimensionality reduction. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 78, 110063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.J.; Chen, K.C. Using tens of seconds of relaxation voltage to estimate open circuit voltage and state of health of lithium ion batteries. Applied Energy 2024, 357, 122488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Tjahjowidodo, T.; Boulon, L.; Feroskhan, M. Framework for measurement of battery state-of-health (resistance) integrating overpotential effects and entropy changes using energy equilibrium. Energy 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C.; Liang, H.; Pecht, M. Energy state of health estimation for battery packs based on the degradation and inconsistency. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 3578–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEE. IEEE Recommended Practice for Maintenance, Testing , and Replacement of Vented Lead-Acid Batteries for Stationary Applications. IEEE Std 450-2002 2003, pp. 1–56. [CrossRef]

- Nejad, S.; Gladwin, D.; Stone, D. A systematic review of lumped-parameter equivalent circuit models for real-time estimation of lithium-ion battery states. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 316, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Izadian, A.; Anwar, S. Nonlinear Model Based Fault Detection of Lithium Ion Battery Using Multiple Model Adaptive Estimation. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2014, 47, 8546–8551, 9th IFACWorld Congress. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Rincon-Mora, G.A. Accurate electrical battery model capable of predicting runtime and I-V performance. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2006, 21, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energizer. Energizer NH15-2300 (HR6), 2024. Available online: https://data.energizer.com (Accessed on may, 2024).

- Mouser. PS-260 Rechargeable sealed Lead acid battery, 2024. Available online: https://www.mouser.com (Accessed on may, 2024).

- GmbH, S.P. Li-ion NCR18650P-H93VA, 2024. Available online: https://www.liontecshop.com (Accessed on may, 2024).

| Attributes / Methods | Desired | CCM | ICA, DVA |

PE, SM |

KF | OM | DDM | UM | EIS | OCV | IRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online/Off-line | On | On | On | On | On | On | On | On | On | Off | Off |

| For embedded systems | Easy | Easy | Mod | Lim | Mod | Mod | Com | Com | Com | Easy | Easy |

| Computational resources/burden | Low | Low | Med | Low | High | Med | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Calibration for start-up | Easy | Easy | Easy | Easy | Mod | Mod | Com | Com | Com | Easy | Mod |

| Charge/discharge description | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| For fault detection/diagnosis | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Design and implementation cost | Low | Low | Med | Low | Med | Low | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Used in reliable engineering | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Used in research & development | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| For management & optimization | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| Estimation with interval data | ✔ | ✔ |

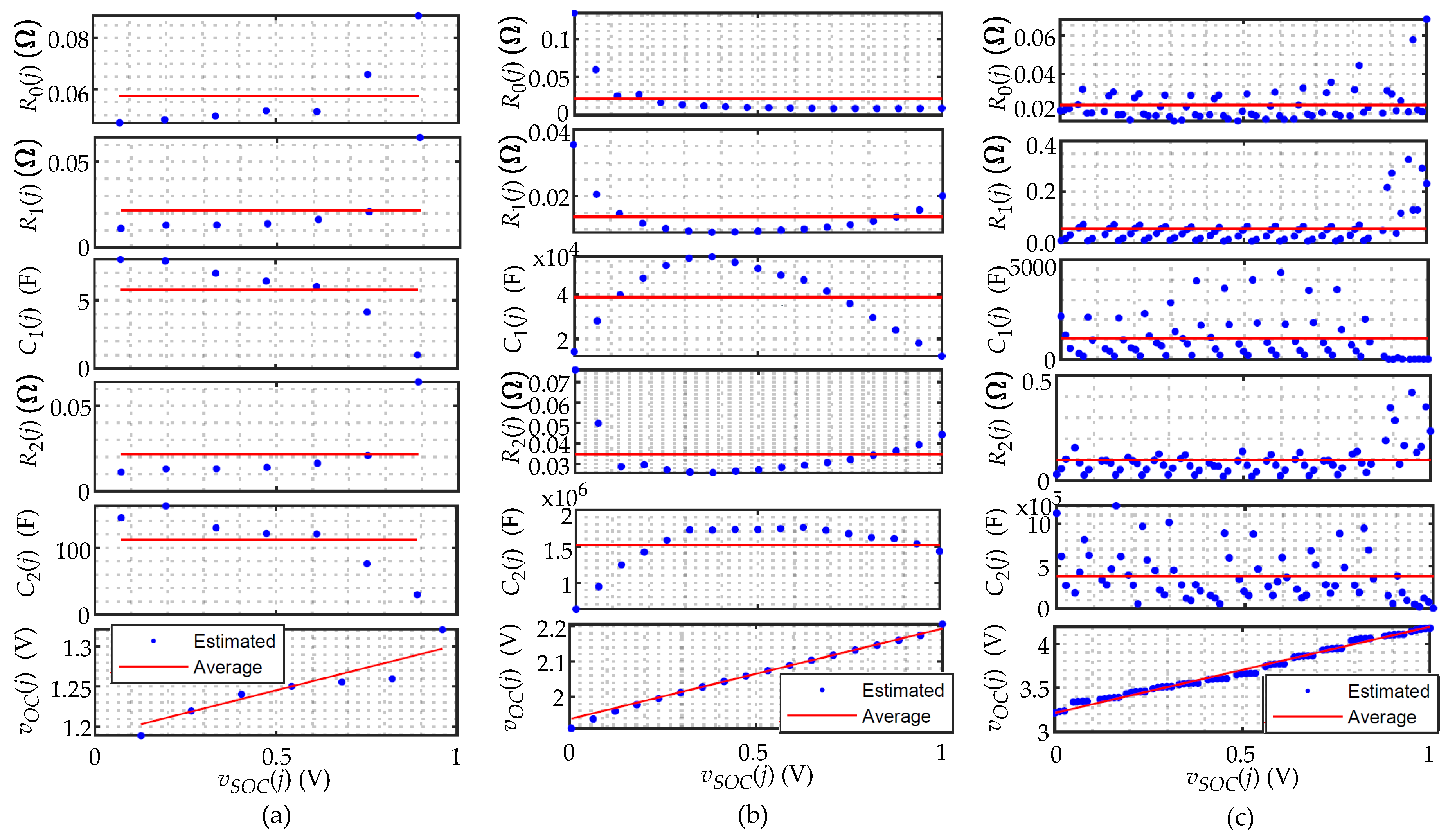

| Parameters and equations | Method and description |

|---|---|

|

Available capacitance: . |

Integral of the battery current method (in a full-discharge test): is in Farads [29], and are cycle number and temperature-dependent correction factors (dimension-less), respectively (they are ideally “1” because and temperature are considered constants each cycle), and is a constant equal to 3600 seconds per volt-hours. |

|

Internal resistance: . |

Current and voltage step (at in Figure 2): is in Ohms [18]. j represents the rest period number. is estimated by averaging the J resistance values obtained by the ratio between and (at the transition of to 0 A), at the begin of each j-th . |

|

Open-circuit voltage: . |

Linear function of the open-circuit voltage versus SOC voltage: (in Volts) is estimated by linear regression of J values of OCV obtained at the end of each j-th (at ). M and K are constants. |

|

RC parameters: . |

Linearized exponential regression (every and after a pulse): and are in Ohms, and are in Faradas [18]. The measured voltage data of each (between and ) is conditioned as a two-term exponential function. is the voltage value at the end of every (at ). The value of is obtained by the integral of the current at the j-th discharge segment. Coefficients a, b, c, and d are calculated by the Curve Fitting Toolbox in MATLAB [18]. RC parameters are estimated by the average of the J values of the j-th coefficients a, b, c, and d obtained at every j-th . |

| Battery data (math. symbol, and unit) | NiMH | Pb-acid | Li-ion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Voltage (, V) | 1.2 a | 2.0 b | 3.6 c |

| Float voltage (, V) | 1.4 a | 2.35 b | 4.2 c |

| Nominal Capacity (, Ah) | 2.3 a | 6.0 b | 2.7 c |

| Available Capacity (, Ah) | 1.448 | 6.592 | 1.339 |

| Equivalent available capacitance (, F) | 5212.8 | 23731.2 | 4820.4 |

| Internal resistance (, ) | 0.05744 | 0.02165 | 0.02430 |

| Transient resistance one (, ) | 0.02173 | 0.01380 | 0.05577 |

| Transient resistance two (, ) | 0.02175 | 0.03470 | 0.09786 |

| Transient capacitance one (, F) | 5.7635 | 38734.5258 | 1045.6885 |

| Transient capacitance two (, F) | 112.2328 | 1519282.831 | 379918.1737 |

| Slope of the linear OCV function (M, dimensionless) | 0.1133 | 0.2555 | 0.9755 |

| Constant of the linear OCV function (K, V) | 1.1886 | 1.9372 | 3.215 |

| Coefficient | NiMH | Pb-acid | Li-ion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41.9330 | 1.8965 | 2.6896 | |

| -39.5367 | 3.5968 | 7.2341 | |

| -93.7191 | 1.8965 | 2.6896 | |

| -3.0812 | 1.1941 | 1.0664 |

| Coefficients | NiMH | Pb-acid | Li-ion |

|---|---|---|---|

| (V) | 1.14 | 1.83 | 3.27 |

| (V) | -0.142 | -0.161 | -1.79 |

| (1/s) | -0.183 | -0.0914 | 5.25 |

| (V) | -0.102 | -0.384 | -0.630 |

| (1/s) | -2.07 | -1.31 | -0.500 |

| Coefficients | NiMH | Pb-acid | Li-ion |

|---|---|---|---|

| (·) | 1.04 | 1.14 | 1.16 |

| (·) | -0.00471 | -0.142 | 0.0148 |

| (1/A) | 0.748 | -0.183 | -0.345 |

| (·) | -0.0440 | -0.102 | 0.0418 |

| (1/A) | -0.376 | -2.07 | -2.30 |

| (A) | 2.30 | 3.60 | 2.7 |

| (h) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Data description | NiMH | Pb-acid | Li-ion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed battery voltage’s RMSE | 0.037747 | 0.01621 | 0.007452 |

| Expected SOH voltage (given by: ) | 0.629 (∼62.9 %) | 1.000 (∼100 %) | 0.495 (∼49.5 %) |

| used to estimate | 0.02 (∼2 %) | 0.07 (∼7 %) | 0.05 (∼5 %) |

| Data description | Li-ion |

|---|---|

| Observed battery voltage’s RMSE | 0.001671 |

| Expected SOH voltage (by: ) | 0.495 (∼49.5 %) |

| used to estimate | 0.01 (∼1 %) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).