Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.Nanostores’ Strategies

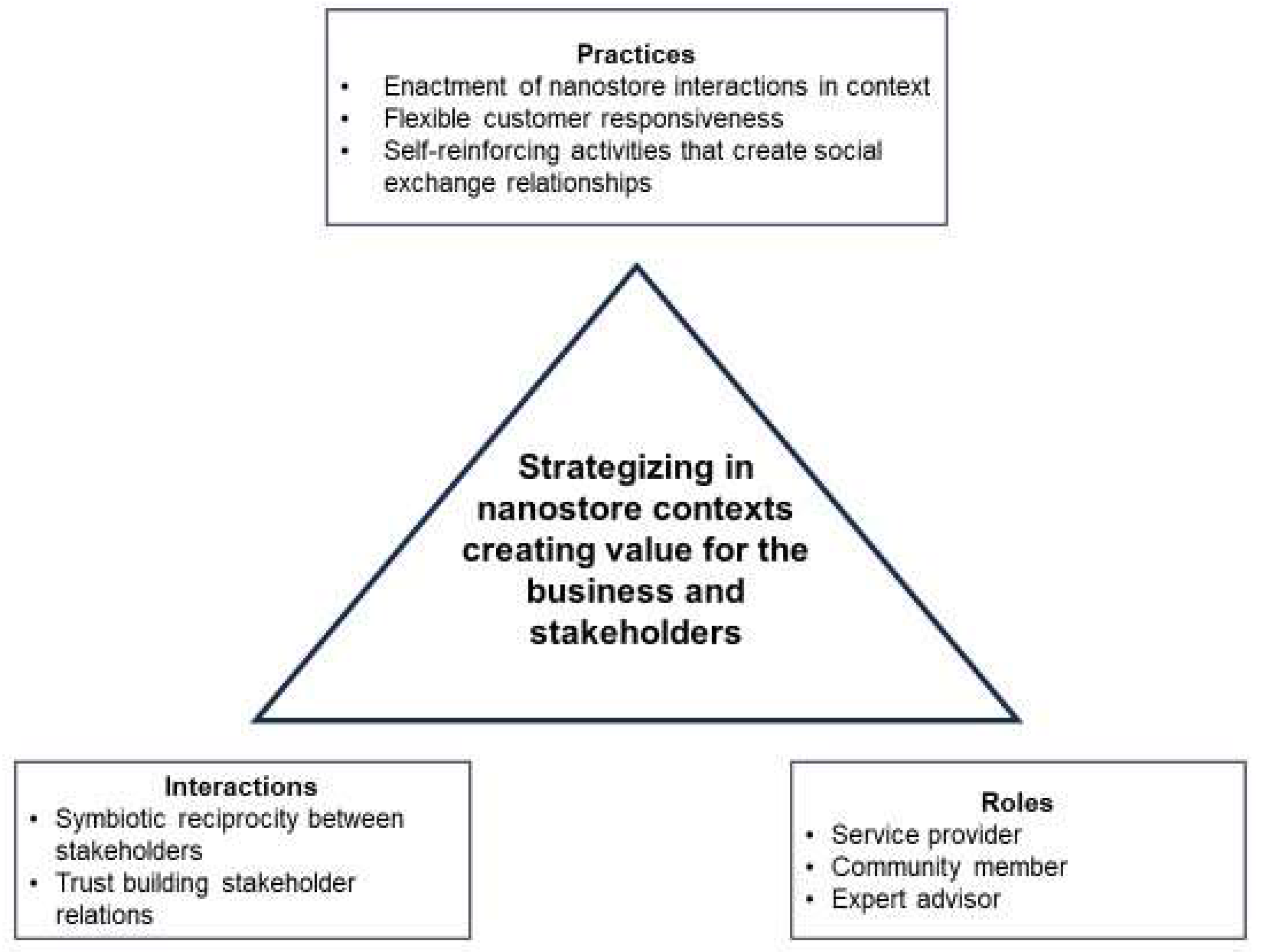

2.2. Strategizing in Nanostores

3. Methodology

- i.

- Input an initial prompt concerning conceptual clarification on nanostores as independent small grocery retailers in emerging countries to outline the general context and study topic;

- ii.

- Input an incremental prompt about nanostores’ strategy practices and ideation to enhance their competitiveness while positively impacting the sustainability of their communities in emerging countries. Gradually provide additional information and guidance to ChatGPT 3.5, if necessary. This stepwise input provided further background information or context;

- iii.

- Input an iterative refinement prompt based on the generated content to explore alternatives to nanostores’ strategies;

- iv.

- Obtain a comprehensive and contextualised final output by combining the incremental steps;

- v.

- Incorporate user feedback to refine the obtained responses for reporting, further exploration, clarification, or exemplification.

4. Results

- i.

-

Conceptual clarification. Confirm the GenAI tool understands the topic being discussed.

- a.

- In the context of grocery retail, what are nanostores?

- b.

- What is the meaning of nanostores' economic competitiveness in grocery retail landscapes?

- c.

- Referring to nanostores, what are sustainable practices in their local communities?

- d.

- What is an emerging country?

- ii.

-

Research question.

- a.

- What strategies can nanostores use to enhance their economic competitiveness in retail landscapes while implementing sustainable practices that positively impact their local communities in emerging countries?

- b.

- Incremental questions regarding exemplifications.

- iii.

-

Reflective use of GenAI tools

- a.

- What is the contribution of GenAI tools to strategy ideation and implementation for nanostores’ competitiveness and sustainability impact?

5. Discussion

- Efficient and sustainable operations. The GenAI tools suggest shop floor optimisation, inventory management, and digital technology integration. However, shop floor optimisation and technological adoption are topics little explored in the nanostore literature, which requires further investigation to maximise operations’ efficiency, product visibility and consumer experience [30,72,73,74]. In contrast, the literature focuses on inventory availability, strengthening personal relationships and supply collaboration in the community [27,28,29,30]. The tools also highlight sustainable practices such as energy saving, water conservation, and waste management. Nevertheless, little work exists in nanostores [15].

- Supplier collaboration, agreements, and local sourcing. This proposition, specifically local sourcing, requires further investigation as it is limitedly explored in the nanostore literature. There is a need to evaluate possible impacts on product prices and availability as local small producers may have uncompetitive production capabilities and cost structures [70]. Nevertheless, supply strategies provide the most numerous alternatives in the supply chain management and logistics literature regarding sourcing, distribution, transportation and supplier relationships [27,29,30,31,32].

- Community engagement. Building trust, social contributions and promoting local development, in which nanostores can become active members of communities. Literature in the field proposes similar alternatives to improve community connections and resilience and create a positive impact, making nanostores an integral part of their communities [13,29,36,76].

- Finally, regarding government-related strategies, the GenAI tools did not provide any suggestions in their answers.

5.1. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fransoo, J.C.; Blanco, E.; Mejia-Argueta, C. Reaching 50 Million Nanostores: Retail Distribution in Emerging Megacities; CreateSpace Independent Publisher Platform, 2017; ISBN 978-1-975742-00-3.

- Escamilla González Aragón, R.; C. Fransoo, J.; Mejía Argueta, C.; Velázquez Martínez, J.; Gastón Cedillo Campos, M. Nanostores: Emerging Research in Retail Microbusinesses at the Base of the Pyramid. Academy of Management Global Proceedings 2020, 161.

- Escamilla, R.; Fransoo, J.C.; Tang, C.S. Improving Agility, Adaptability, Alignment, Accessibility, and Affordability in Nanostore Supply Chains. Prod Oper Manag 2021, 30, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Espinosa, M.F.; Hernández-Arreola, J.R.; Pale-Jiménez, E.; Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Mejía Argueta, C. Increasing Competitiveness of Nanostore Business Models for Different Socioeconomic Levels. In Supply Chain Management and Logistics in Emerging Markets; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y., Mejía Argueta, C., Mattos, M.G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2020; pp. 273–298 ISBN 978-1-83909-333-3.

- Kin, B. Less Fragmentation and More Sustainability: How to Supply Nanostores in Urban Areas More Efficiently? Transportation Research Procedia 2020, 46, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Peredo, R.; Sánchez-Lara, B.; Gómez-Eguiluz, M. Nanostores’ Density and Geographical Location: An Empirical Study Under Urban Logistics Approach. In Technological and Industrial Applications Associated With Industry 4.0; Ochoa-Zezzatti, A., Oliva, D., Hassanien, A.E., Eds.; Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; Vol. 347, pp. 271–290 ISBN 978-3-030-68662-8.

- Chaniago, H. Understanding Purchase Motives to Increase Revenue Growth: A Study of Nanostores in Indonesia. Innovative Marketing 2021, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Rivera, D.; Mejía, G.; Tinjaca, L.; Cárdenas, N. Design of a Nanostores’ Delivery Service Network for Food Supplying in COVID-19 Times: A Linear Optimization Approach. In Production Research; Rossit, D.A., Tohmé, F., Mejía Delgadillo, G., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; Vol. 1408, pp. 19–32 ISBN 978-3-030-76309-1.

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Alanis-Uribe, A.; da Silva-Ovando, A.C. Learning Experiences about Food Supply Chains Disruptions over the Covid-19 Pandemic in Metropolis of Latin America. In Proceedings of the 2021 IISE Annual Conference; Ghate, A., Krishnaiyer, K., Paynabar, K., Eds.; 2021; pp. 495–500.

- Sharif, M.Z.; Albert, S.L.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Lopez, G.; Kuo, A.A.; Prelip, M.L.; Ortega, A.N.; Glik, D.C. Community Residents’ Beliefs About Neighborhood Corner Stores in 2 Latino Communities: Implications for Interventions to Improve the Food Environment. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 2017, 12, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, L. Sustainable Development and Food Retailing: UK Examples. In Food Retailing and Sustainable Development; Lavorata, L., Sparks, L., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2018; pp. 67–80 ISBN 978-1-78714-554-2.

- Coen, S.E.; Ross, N.A.; Turner, S. “Without Tiendas It’s a Dead Neighbourhood”: The Socio-Economic Importance of Small Trade Stores in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Cities 2008, 25, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A. A Cultural History of the Beloved Corner Shop. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200325-a-cultural-history-of-the-beloved-corner-shop (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Everts, J. Consuming and Living the Corner Shop: Belonging, Remembering, Socialising. Social & Cultural Geography 2010, 11, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Carvajal, D.; Gutierrez-Franco, E.; Mejia-Argueta, C.; Suntura-Escobar, H. Out of the Box: Exploring Cardboard Returnability in Nanostore Supply Chains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; LaGuardia, P.; Srinivasan, M. Building Sustainability in Logistics Operations: A Research Agenda. Management Research Review 2011, 34, 1237–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Saha, K.; Budhwar, P.; De, D. Adoption of Circular Economy Practices in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Evidence from Europe. International Journal of Production Economics 2022, 248, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkepatt, G.G.; Winterich, K.P.; Mittal, V.; Zinn, W.; Beitelspacher, L.; Aloysius, J.; Ginger, J.; Reilman, J. Sustainable Retailing. Journal of Retailing 2021, 97, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Arias-Portela, C.Y.; González De La Cruz, J.R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E. Experiential Learning for Circular Operations Management in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paswan, A.; Pineda, M. de los D.S.; Ramirez, F.C.S. Small versus Large Retail Stores in an Emerging Market—Mexico. Journal of Business Research 2010, 63, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, A.; Rosengren, S.; Perzon, J. Towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Gaps in Retail Organizations. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2023, 33, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolgast, H.; Halverson, M.M.; Kennedy, N.; Gallard, I.; Karpyn, A. Encouraging Healthier Food and Beverage Purchasing and Consumption: A Review of Interventions within Grocery Retail Settings. IJERPH 2022, 19, 16107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Jiménez, C.H.; Amador-Matute, A.; Parada López, J.; Zavala-Fuentes, D.; Sevilla, S. A Meta-Analysis of Nanostores: A 10-Year Assessment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd LACCEI International Multiconference on Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development (LEIRD 2022): “Exponential Technologies and Global Challenges: Moving toward a new culture of entrepreneurship and innovation for sustainable development”; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2022.

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.A.; Kandathil, G. Strategizing in Small Informal Retailers in India: Home Delivery as a Strategic Practice. Asia Pac J Manag 2020, 37, 851–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Reprint.; Capstone: Oxford, 2002; ISBN 978-1-84112-084-3.

- Monnagaaratwe, K.F.; Motatsa, K.W. Enhancing Business Competitiveness of Medium-Sized Food Produce Retailers through Supply Chain Management. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didonet, S.; Simmons, G.; Díaz-Villavicencio, G.; Palmer, M. The Relationship between Small Business Market Orientation and Environmental Uncertainty. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2012, 30, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.N.; Kundu, K.; Chaudhuri, H.R. Developing a Conceptual Model of Small Independent Retailers in Developing Economies: The Roles of Embeddedness and Subsistence Markets. AMS Rev 2016, 6, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.; Harris, K.; Leaver, D.; Oldfield, B.M. Beyond Convenience: The Future for Independent Food and Grocery Retailers in the UK. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2001, 11, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangvikar, B.; Kolte, A.; Pawar, A. Competitive Strategies for Unorganised Retail Business: Understanding Structure, Operations, and Profitability of Small Mom and Pop Stores in India. International Journal on Emerging Technologies 2019, 10, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Monnagaaratwe, K.F.; Mathu, K. Supply Chain Management as a Competitive Advantage for Grocery Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Mahikeng, South Africa. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, B. Operation Strategies for Nanostore in Community Group Buying. Omega 2022, 110, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Graham, M.; Taylor, K.; Mah, C.L. Corner Store Retailers’ Perspectives on a Discontinued Healthy Corner Store Initiative. Community Health Equity Research & Policy 2023, 43, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboush-Deloye, A.L.; Knight, M.A.; Bungum, N.; Spendlove, S. Healthy Foods in Convenience Stores: Benefits, Barriers, and Best Practices. Health Promotion Practice 2023, 24, 108S–111S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M.; Estrada, J.; Dyer, S.; Hennessey-Lavery, S.; Wakimoto, P.; Falbe, J. Healthy Retail as a Strategy for Improving Food Security and the Built Environment in San Francisco. Am J Public Health 2019, 109, S137–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinlocke, R.; Thomas-Hope, E. Characterisation, Challenges and Resilience of Small-Scale Food Retailers in Kingston, Jamaica. Urban Forum 2019, 30, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, 2015.

- D. E. Salinas Navarro Performance in Organisations, An Autonomous Systems Approach. Lambert Academic Publishing 2010.

- Luederitz, C.; Caniglia, G.; Colbert, B.; Burch, S. How Do Small Businesses Pursue Sustainability? The Role of Collective Agency for Integrating Planned and Emergent Strategy Making. Bus Strat Env 2021, 30, 3376–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.; Harrington, D.; Kelliher, F. Strategizing in the Micro Firm: A ‘Strategy as Practice’ Framework. Industry and Higher Education 2019, 33, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.; Harrington, D.; Kelliher, F. Exploiting Managerial Capability for Innovation in a Micro-Firm Context: New and Emerging Perspectives within the Irish Hotel Industry. European Journal of Training and Development 2013, 38, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R.; Stewart, N.D. Systemic Reflections on Environmental Sustainability. Syst. Res. 1998, 15, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskender, A. Holy or Unholy? Interview with Open AI’s ChatGPT. EJTR 2023, 34, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, A.; Bukoye, O.T.; O’Dea, C.; Kremantzis, M. The Influence of AI Text Generators on Critical Thinking Skills in UK Business Schools. Studies in Higher Education 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccardi, E.; Cila, N.; Speed, C.; Caldwell, M. Thing Ethnography: Doing Design Research with Non-Humans. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems; ACM: Brisbane QLD Australia, June 4 2016; pp. 377–387.

- Giaccardi, E.; Speed, C.; Cila, N.; Caldwell, M.L. Things as Co-Ethnographers: Implications of a Thing Perspective for Design and Anthropology. In Design Anthropological Futures; Smith, R.C., Vangkilde, K.T., Kjærsgaard, M.G., Otto, T., Halse, J., Binder, T., Eds.; Routledge: London ; New York : Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, Plc, [2016], 2020; pp. 235–248 ISBN 978-1-00-308518-8.

- Cila, N.; Giaccardi, E.; Tynan O’Mahony, F.; Speed, C.; Caldwell, M. Thing-Centered Narratives: A Study of Object Personas.; January 22 2015.

- Eriksson, P.; Kovalainen, A. Qualitative Methods in Business Research; 2nd edition.; SAGE: Los Angeles, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4462-7339-5.

- Rinaldo, R.; Guhin, J. How and Why Interviews Work: Ethnographic Interviews and Meso-Level Public Culture. Sociological Methods & Research 2022, 51, 34–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-W.; Giaccardi, E.; Chen, L.-L.; Liang, R.-H. “Interview with Things”: A First-Thing Perspective to Understand the Scooter’s Everyday Socio-Material Network in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems; ACM: Edinburgh United Kingdom, June 10 2017; pp. 1001–1012.

- Rudolph, J.; Tan, S.; Tan, S. ChatGPT: Bullshit Spewer or the End of Traditional Assessments in Higher Education? JALT 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Michel-Villarreal, R.; Montesinos, L. Using Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools to Explain and Enhance Experiential Learning for Authentic Assessment. Education Sciences 2024, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y. (Gina); Van Esch, P.; Phelan, S. How to Build a Competitive Advantage for Your Brand Using Generative AI. Business Horizons 2024, 67, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Innovation Management: A Preview of Future Research Developments. Journal of Business Research 2024, 175, 114542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, D.A. An Interview with ChatGPT About Health Care. Catalyst non-issue content 2023, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Karakose, T.; Demirkol, M.; Aslan, N.; Köse, H.; Yirci, R. A Conversation with ChatGPT about the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Education: Comparative Review Based on Human–AI Collaboration. EDUPIJ 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tülübaş, T.; Demirkol, M.; Özdemir, T.Y.; Polat, H.; Karakose, T.; Yirci, R. An Interview with ChatGPT on Emergency Remote Teaching: A Comparative Analysis Based on Human–AI Collaboration. EDUPIJ 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Michel-Villareal, R.; Montesinos, L. Designing Experiential Learning Activities with Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools for Authentic Assessment. Interactive Technology and Smart Education 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.; Horrocks, C. Interviews in Qualitative Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4129-1256-3. [Google Scholar]

- Köhn, A. Incremental Natural Language Processing: Challenges, Strategies, and Evaluation. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCompte, M.D.; Goetz, J.P. Problems of Reliability and Validity in Ethnographic Research. Review of Educational Research 1982, 52, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. The Academy of Management Review 1989, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E. Nanostores’ Competitiveness and Sustainability Impact on Communities in Emerging Countries, An Interview with ChatGPT 3.5 2024.

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E. Nanostores’ Competitiveness and Sustainability Impact on Communities in Emerging Countries, An Interview with Microsoft Copilot 2024.

- Korneeva, E.; Skornichenko, N.; Oruch, T. Small Business and Its Place in Promoting Sustainable Development. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 250, 06007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Cohen, M.; Lorek, S.; Schroeder, P. Transforming Systems of Consumption and Production for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Moving beyond Efficiency. Sustain Sci 2018, 13, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez-Ponce, E.; Clarke, A.; MacDonald, A. Business Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals through Community Sustainability Partnerships. SAMPJ 2021, 12, 1239–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.A.; Fillis, I.; Johansson, U. An Exploratory Study of SME Local Sourcing and Supplier Development in the Grocery Retail Sector. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 2005, 33, 716–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. 25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It. Harvard Business Review 2018, 25, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, E.; Lim, A.; Xu, J. Retail Store Layout Optimization for Maximum Product Visibility. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2023, 74, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirpara, S.; Parikh, P.J. Retail Facility Layout Considering Shopper Path. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2021, 154, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-de Miguel, J.-F.; Buil-López Menchero, T.; Esteban-Navarro, M.-Á.; García-Madurga, M.-Á. Proximity Trade and Urban Sustainability: Small Retailers’ Expectations Towards Local Online Marketplaces. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langellier, B.A.; Garza, J.R.; Prelip, M.L.; Glik, D.; Brookmeyer, R.; Ortega, A.N. Corner Store Inventories, Purchases, and Strategies for Intervention: A Review of the Literature. Calif J Health Promot 2013, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. Towards Marketplace Resilience: Learning from Trader, Customer and Household Studies in African, Asian and Latin American Cities. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 2020, 12, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sams, D.; Parker, J. The Perspective of Small Retailers on Sustainability: An Exploratory Study for Scale Development. In Let’s Get Engaged! Crossing the Threshold of Marketing’s Engagement Era; Obal, M.W., Krey, N., Bushardt, C., Eds.; Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 605–609 ISBN 978-3-319-11814-7.

- Mora-Quiñones, C.; Cárdenas-Barrón, L.; Velázquez-Martínez, J. ; Karla Gámez-Pérez The Coexistence of Nanostores within the Retail Landscape: A Spatial Statistical Study for Mexico City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Nanostore Strategies | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Operations |

|

[27] |

|

[28] | |

|

[29] | |

|

[30] | |

| Suppliers |

|

[29,31] |

|

[29] | |

|

[29] | |

|

[29] | |

|

[30] | |

|

[32] | |

|

[27] | |

|

[33] | |

| Customers |

|

[29] |

|

[29,31] | |

|

[20] | |

|

[30] | |

|

[30] | |

|

[27,31] | |

|

[27] | |

|

[34,35,36] | |

| Community |

|

[12,29] |

|

[36] | |

| Government |

|

[37] |

| Strategy Category | Nanostore strategy practices | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Operations | Energy efficiency and resource conservation: “Invest in energy-efficient appliances, lighting, and refrigeration systems to reduce energy consumption and lower operating costs. Implement water-saving measures and waste reduction strategies to minimize environmental impact.” | Energy-efficient lighting and appliances, insulation and sealing, energy-monitoring and management systems, renewable energy sources, water conservation measures, waste reductions and recycling, and reusable packaging and bagging. |

| Suppliers | Local sourcing and partnerships: “Source products locally from small-scale producers, farmers, and artisans to support the local economy and reduce transportation emissions. Establish partnerships with local suppliers to ensure a steady supply of high-quality goods.” | Partnerships with farmers' cooperatives, artisanal producers, community and school gardens, social enterprises, local breweries and wineries, and cultural/ethnic communities. |

| Customers | Diverse product offerings: “Offer a diverse range of products tailored to local preferences and needs, including staple foods, fresh produce, household essentials, and culturally relevant items. This enhances customer satisfaction and loyalty while promoting economic diversity.” | Fresh produce, staple foods, dairy and eggs, bakery and bread, meat and poultry, packed goods, snacks and beverages, household essentials, environmental-friendly products, cultural and ethnic foods, and seasonal and holiday items. |

| Affordable pricing and value proposition: “Maintain competitive pricing to attract customers from all socio-economic backgrounds. Emphasize the value proposition of nanostores, such as convenience, personalized service, and support for local communities, to differentiate from larger retailers.” | Basic essential bundles, daily deals and special offers, affordable meal kits, affordable private label brands, customer loyalty programs, convenient payment options, and free or discounted delivery services. | |

| Community | Community engagement and empowerment: “Engage with the local community through educational initiatives, workshops, and events focused on sustainability, health, and entrepreneurship. Empower residents by offering training programs, employment opportunities, and support for small businesses.” | Educational workshops and events, community garden sponsorships, youth employment programs, cultural celebrations, health and wellness programs, financial literacy programs, environmental clean-up and conservation efforts, and community outreach and advocacy. |

| Operations, customers, and suppliers | Technology integration: “Embrace technology to streamline operations, improve efficiency, and enhance customer experience. Implement digital payment systems, inventory management software, and online ordering platforms to increase convenience and accessibility.” | Point-of-sale systems, barcode scanners and inventory management software, digital payment solutions, online ordering platforms, automated reordering systems, digital marketing, customer feedback and reviews platforms, and remote monitoring systems. |

| Customers, suppliers, and community | Healthy lifestyle promotion: “Promote healthy eating habits and lifestyles by offering a variety of nutritious foods, promoting local produce, and providing information on healthy cooking and eating. Collaborate with healthcare providers and community organizations to raise awareness of health-related issues.” | Nutrition education workshops, healthy recipe demonstrations, fresh produce promotions, healthy snack options, labelling and signage, partnerships with health and wellness brands, and support for healthy habits. |

| Operations, customers, and suppliers | Waste reduction and recycling programs: “Implement recycling programs for packaging materials and encourage customers to bring their reusable bags and containers. Minimize food waste through smart inventory management, portion control, and donations to local charities.” | Comprehensive recycling stations, reusable packaging and bagging programs, food waste reduction strategies, composting initiatives, packaging material recycling, refill and reuse programs, electronics and battery recycling, and supplier packing reduction requests. |

| Customers, suppliers, and community | Social responsibility and ethical practices: “Operate ethically and transparently, adhering to fair labour practices, and supporting social causes that benefit the local community. Communicate values of social responsibility and environmental stewardship to customers and stakeholders.” | Fair labour practices, product quality and safety, ethical sourcing, and supply chain management, cultural sensitivity and inclusivity, transparency, and accountability, customer privacy and data protection, and promotion of social causes. |

| Operations, customers, and suppliers. | Adaptability and innovation: “Stay agile and responsive to changing market dynamics and consumer preferences. Innovate with new product offerings, services, or business models that align with sustainability goals and address emerging needs in the community.” | Agile pricing strategies, delivery and distribution innovation, product innovation and differentiation, continuous improvement, customer engagement and personalisation, adaptive store layout and design, and digital transformation and online presence. |

| Strategy Category | Nanostore strategy practices | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Operations | “Optimize Store Layout: Efficient use of space and attractive product displays can enhance the shopping experience and increase sales. Regularly updating the store layout based on customer preferences can keep the store appealing.” | Clear entrance and pathways, strategic product placement, eye-level displays, themed sections, end-cap promotions and featured presentations, checkout area optimisation, clear signage and labels, pleasant lighting and ambience, flexible shelving usage, customer flow analysis, and interactive displays. |

| “Energy Efficiency: Using energy-efficient lighting and appliances, and considering renewable energy sources like solar panels, can reduce energy consumption and costs.” | Led lighting, energy-saving appliances, smart thermostats, motion-sensor lighting, natural lighting, insulation and weatherproofing, solar panels, and window and door insulation. | |

| “Water Conservation: Installing water-saving fixtures and promoting water conservation practices can reduce water usage. Collecting rainwater for non-potable uses can also be beneficial.” | Low-flow fixtures, rain harvesting, water-efficient appliances, grey-water recycling, smart water meters, and water-saving landscaping. | |

| Suppliers | “Collaborate with Suppliers: Establishing strong relationships with suppliers can lead to better pricing, exclusive deals, and timely deliveries. Group purchasing with other nanostores can also help in negotiating better terms.” | Bulk purchasing agreements, exclusive product deals, joint promotions, consignment arrangements, shop training and support, shared logistics, feedback and product development, vendor inventory management, favourable credit terms, and waste reduction initiatives. |

| “Local Sourcing: Purchasing products from local farmers and producers can reduce transportation emissions and support the local economy. This also ensures fresher products for customers.” | Fresh produce, dairy products, baked goods, meat and poultry, craft beverages, hand-made goods, ham and honey, spices and condiments, eco-friendly products, cultural and traditional products, and flowers and plants. | |

| Customers | “Diversify Product Offerings: Expanding the range of products to include high-demand items and local specialties can attract more customers. Offering unique products that are not available in larger stores can create a niche market.” | Local and organic products, speciality foods, household essentials, seasonal products, prepared foods, health and wellness products, pet supplies, stationery and school supplies, eco-friendly products, cultural and religious items, technology accessories, and DIY and craft supplies. |

| “Enhance Customer Experience: Providing personalized service, loyalty programs, and community engagement activities can build strong customer loyalty. Understanding and catering to the specific needs of the local community is crucial.” | Personalised services, loyalty programmes, cleaned and organised store layout, customer feedback, convenient payment options, community events, online presence, home delivery services, special promotions and discounts, customer appreciation days, training staff, and a comfortable shopping environment. | |

| Community | “Community Engagement: Participating in or sponsoring local environmental initiatives, such as tree planting or clean-up drives, can strengthen community ties and promote sustainability.” | Local event support, workshops and classes, community boards, charity drives, school partnerships, health and wellbeing programmes, holiday celebrations, and support of local causes. |

| Operations and Community | “Waste Management: Implementing proper waste segregation and composting organic waste can minimize environmental impact. Partnering with local waste management services can enhance these efforts.” | Recycling, reuse, composting, waste source reduction, zero-waste initiatives, and support for waste-reduction community events. |

| Community and customers | “Promote Recycling and Reuse: Encouraging customers to bring their bags and containers, and reusing packaging materials can reduce waste. Setting up recycling bins for customers can also promote environmental responsibility.” | Reusable bags, recycling bins, packaging reuse, bottle returns, composting promotion, upcycling workshops, refill stations, customer environmental education, incentive programmes, and second-hand sales. |

| Operations and customers | “Leverage Technology: Implementing digital tools for inventory management, sales tracking, and customer relationship management can streamline operations and improve efficiency. Mobile payment systems can also enhance customer convenience.” | Point of sale systems, mobile payment solutions, inventory management software, customer relationship management tools, e-commerce platforms, social media marketing, digital loyalty programs, data analytics, cloud-based accounting software, and delivery and logistics apps. |

| ChatGPT 3.5 | Microsoft Copilot |

|---|---|

“Strategy Ideation

|

|

| Category | Summarised literature-based strategies | Summarised GenAI strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Operations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Suppliers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Customers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Community |

|

|

|

|

|

| Government |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).