Introduction

Sporadic colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent and deadliest malignancies in the world. This neoplasm is also recognized as a diet- and obesity-related disease [

1], which suggests, from one perspective, associations between appetite regulation and food intake and carcinogenesis processes, and, from another, the role of nutritional status in CRC patients’ prognosis. Namely, about 10-20% of patients with cancer die due to undernutrition rather than cancer itself [

2,

3], and malnutrition and sarcopenia were found to be associated with poor response to oncological treatment [

4]. Therefore, the regulation and balance of food intake in patients with CRC is very important. One of the organ systems that play a role in appetite regulation is the nervous system. Neuropeptides secreted from the central and peripheral systems, which includes the visceral nervous system, exhibit both anorexic (e.g., leptin) and orexigenic (e.g., orexin, neuropeptide Y [NPY], and ghrelin) effects. Moreover, neuropeptides also activate the molecular mechanism of cancer development and progression (metastases) through epigenetic and genetic (gene methylation) [

1,

5,

6], endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine [

7], as well as pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory pathways [

5]. These observations are supported by significant associations found between CRC and several nutrigenomic polymorphisms, namely: those involved in folate metabolism (e.g., methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase produced by MTHFR), lipid metabolism (e.g., apolipoprotein A-I [ApoA-I]), in oxidative stress (e.g., catalase) and inflammatory (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-alpha]) responses, as well as in the intake of some nutrients and nutraceuticals [

1].

NPY is an orexigenic (appetite stimulant) protein, belonging to the pancreatic polypeptide family (which also includes peptide YY and PP), and is widely expressed in the central nervous system [

8,

9,

10,

11]. NPY influences nutritional behavior, energy balance, obesity, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, emotional regulation, and stress response [

12]. In some populations, NPY polymorphisms are associated with increased food and alcohol consumption and thus potentially with obesity pathogenesis, food preference, and alcohol dependence [

13,

14]. Recent studies also show a potential role of NPY in the course of CRC [

15]. It was, for example, found that NPY regulates angiogenesis through paracrine activity [

7] and stimulates inflammatory-induced tumorogenesis through enhanced cell proliferation and downregulation of micro-RNA-375 (miR-375) [

5,

16,

17,

18,

19]. It was also shown that hypermethylated NPY circulating tumor DNA (meth-ctDNA), when analyzed by droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, may be useful as a biomarker of CRC metastasis and progression, allowing treatment reorientation at an earlier timepoint [

6,

10,

15,

20,

21,

22,

23], and was recommended as a means of last-line treatment with regorafenib in metastatic CRC patients [

10]. In CRC patients, progression-free survival was significantly shorter in patients with NPY DNA methylation compared to individuals without NPY gene methylation [

10,

22]. Serum NPY concentration was found to be lower in CRC patients, a decrease that was associated with tumor size (> 5 cm) and body weight loss (> 3 kg) [

22]. It was also found that NPY gene expression was higher in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue, independently of tumor stage [

24]; however, it should be stated that NPY gene activity was found to be associated with a reduced potential for the invasiveness of tumor cells in a concentration-dependent manner [

25].

In light of the above-cited evidence, we undertook our study to determine if there were associations between serum NPY concentration and nutritional status assessment, nutritional risk, and prognosis among patients undergoing surgery for CRC.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This prospective study with a 3-month follow-up involved 84 consecutive inpatients who underwent elective surgery between 2016 and 2019 due to primary CRC at our University Hospital. The exclusion criteria were lack of informed consent to participate in the study and the need for emergency surgery (e.g., due to bowel obstruction or hemorrhage). Oral nutritional supplements, immunonutrition, or pre-operative multimodal prehabilitation was not recommended before CRC surgery.

During their first day of admission, a medical history was obtained from each of the patients enrolled to the study and a physical examination was performed that included an assessment of anthropometric parameters of nutritional status and body composition (described in the subsection below). Data concerning tumor size, clinical and histopathological stages, as well as perioperative complications were also collected. After being discharged, the patients were invited to attend a follow-up visit 3 months after their operation. All the examinations performed during the baseline visit were repeated during the follow-up visit (not all were presented in detail). In a long-term follow-up (median; IQR: 1322; 930-1788 days; average 3.6 years), the patients’ survival status was checked during a telephone visit.

Parameters of Nutritional Status and Body Composition Assessment

The following parameters of nutritional and anthropometric status assessment were measured at baseline and at the 3-month follow-up visit: Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) (a score of 3 or more points indicating a risk of malnutrition-related complications); Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (

PG-

SGA) (a score of 5 or more points in the questionnaire indicating a risk of malnutrition-related complications); Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (a score in the range 17-23.5 in the questionnaire indicating a risk of malnutrition, and a score < 17 indicating malnutrition); body weight (kg); height (cm); body mass index (BMI) (kg/m

2) (measured as the ratio of body weight to the square of height [m]); waist circumference (WC) (cm); waist to hip ratio (WHR); waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) (measured as the ratio of WC [cm] to height [cm]); mid-arm circumference (MAC) (cm); calf circumference (cm); triceps skinfold thickness (TSF) (mm) and subscapular skinfold thickness (SST) (mm) (measured using the Harpenden MG-4800 manual skinfold caliper; BATY, UK); and the handgrip strength (HGS) (kg) of the dominant hand (measured using an electronic dynamometer; Kern, Germany). The established cut-off values for normal HGS were used: 16 kg for females and 27 kg for males [

26]. Body composition was determined using whole-body bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) with a TANITA BC 420 MA device (TANITA Corporation, Japan). The following BIA parameters were analyzed: fat mass (FM) (expressed as a percentage of total body weight [FM%] and as absolute mass in kg [FM, kg]); visceral adipose tissue (VAT) score (range 1-59, a level > 12 indicating abdominal adiposity); fat-free mass (FFM) (kg); skeletal muscle mass (SMM) (expressed as a percentage of total body mass [SMM%] and as absolute mass in kg [SMM, kg]); basal metabolic rate (BMR) (kcal); and metabolic age (MA) (years) [

27]. In BIA, established sarcopenia criteria were used: < 37% for males and < 31.5% for females [

26]. Moreover, because abdominal computed tomography (CT, Revolution HD, GE Healthcare, UK) was performed in every CRC patient before surgery (range of slice thickness: 1-5 mm), the regional densitometric quantification of skeletal muscle (SM) (attenuation limit -30 to 150 Hounsfield units [HU]), VAT (attenuation limit -150 to -50 HU) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), and their cross-sectional areas (CSA) at the third lumbar (L3) vertebra were manually selected using OsiriX software (Pixmeo SARL, Bernex, Switzerland) as specific regions of interest (ROI) [

28] and parameters of body composition.

Functional status, using, for example, Barthel, activities of daily living (ADL), and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) indices, was also established.

Biochemical Determinations

Blood samples were taken from the ulnar vein of each patient between 7 am and 8 am on the day of admission while they were in a fasting state. For all patients in the study, the following biochemical determinations were performed in the hospital’s diagnostic laboratory using standard methods: blood morphology with a detailed determination of white blood cell distribution (total lymphocyte count [TLC] and neutrophils), glucose, albumin, C-reactive protein, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The pre-operative Onodera Prognostic Nutritional Index (OPNI) was also calculated according to the following formula: [10

× blood albumin concentration (g/l)] + [0.005

× TLC (G/l)] [

29].

Serum NPY concentration was assessed using an immunoenzymatic ELISA kit from Cloud-Clone Corp. (cat. no. CEA607Hu, Katy, Tx, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum samples were centrifuged at a temperature of 4 oC with a spin speed of 3500 revolutions per minute. The serum sample was then stored at a temperature of -80 oC until determination.

Outcomes Measured

At the beginning of the study, blood NPY concentration was related to: initial values of nutritional status assessment parameters, including the SM, SAT and VAT CSA scans at L3; length of in-hospital stay (LOS) and occurrence of perioperative complications; and cancer advancement (WHO clinical stages I-IV). At a 3-month follow-up visit, as at baseline, nutritional and functional status questionnaires were completed and anthropometric parameters of nutritional status and BIA parameters of body composition obtained. In the long-term follow-up, patients’ survival was checked by a telephone visit, with a median follow-up period of 1322 days (IQR: 930-1788 days; average: 3.6 years).

Bioethics

The investigation was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research, after receiving permission from the local Bioethical Committee (No. KB 595/2015).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using the licensed version of the statistical software Statistica, version 13.3, developed by Tibco Software, Inc. (2017). The normal distribution of the study variables was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Depending on the type of variable distribution, the results were presented as the median; the interquartile range (IQR); the mean ± standard deviation; or n, %; and the statistical significance of differences between groups was verified using the Mann-Whitney U non-parametric test, Student’s t-test, or Chi2 test. The statistical significance level was set at a p-value < 0.05. A Kaplan-Meier curve was determined in the survival analysis.

Results

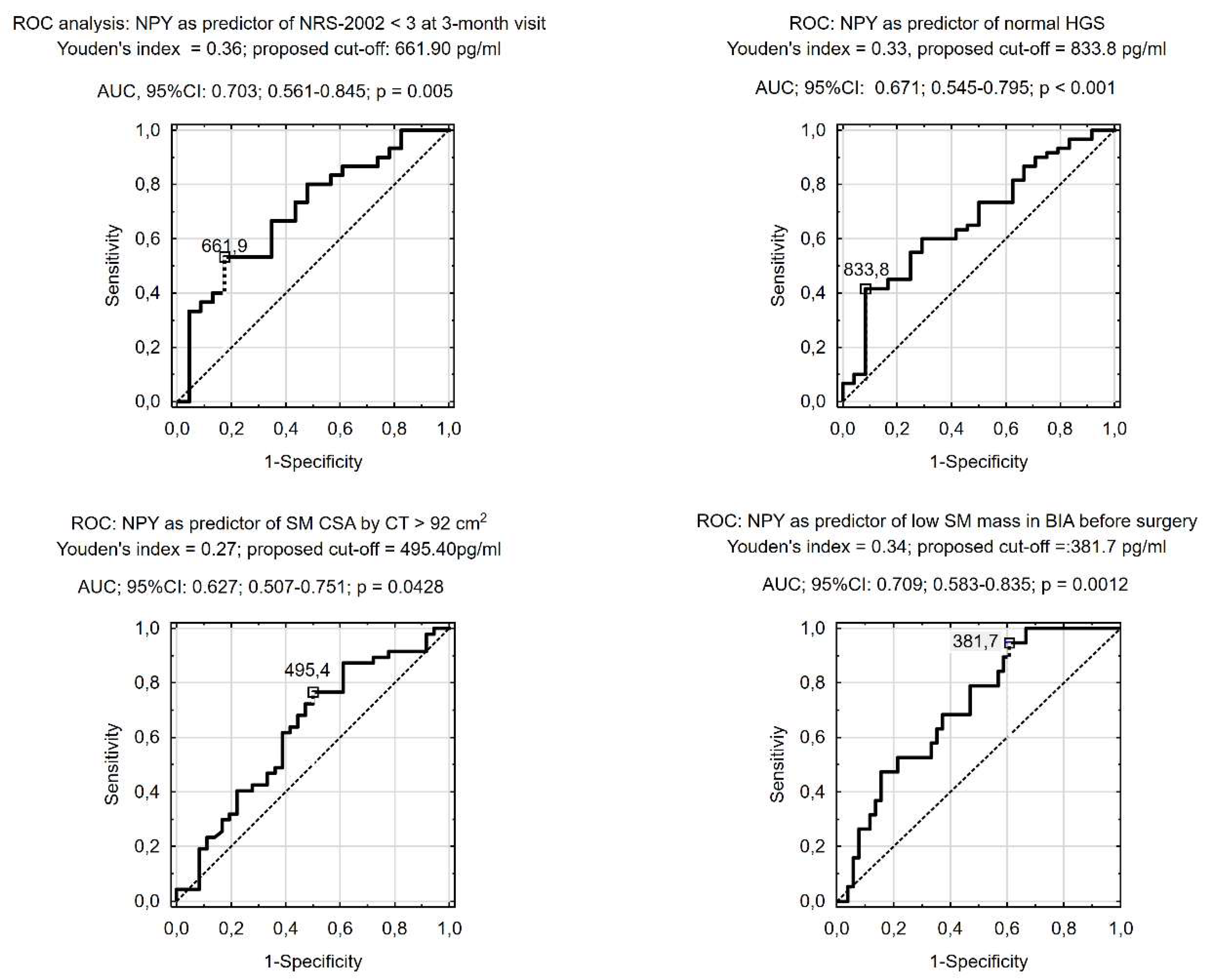

Prognostic Value of NPY (Receiver Operating Characteristic [ROC] Analysis)

In ROC analysis, serum NPY concentration was predictive of having normal HGS before surgery, SM CSA in CT slides at L3 ≥92 cm

2, and a sarcopenia diagnosis according to BIA criteria (i.e., percentage of SM < 37% in males and < 31.5% in females). We also found that low serum NPY concentration before CRC surgery was predictive of increased nutritional risk at the 3-month follow-up visit (

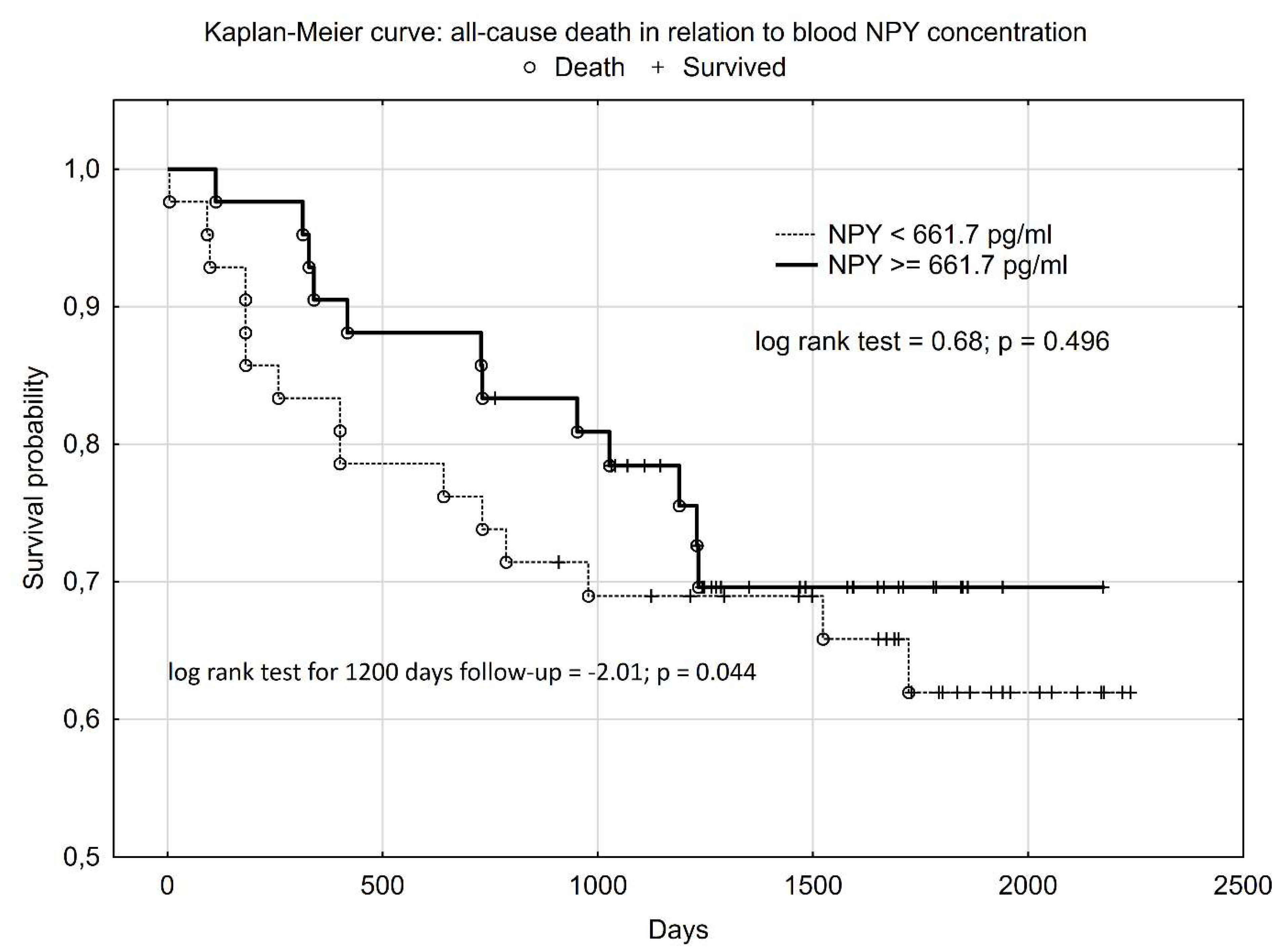

Figure 1). In Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, higher NPY serum concentration had a statistically significant influence on patients’ survival until 1200 days after CRC surgery (log rank test = -2.01; p = 0.044). However, when we performed analysis for the whole of the follow-up, the Kaplan-Meier curves overlapped and the statistically significant difference disappeared (log rank test = 0.68; p = 0.496) (

Figure 2).

Discussion

One of the significant factors influencing the prognosis of CRC patients undergoing surgery is their nutritional status and risk, as well as appetite and food intake. The early identification of patients threatened by death or by a worsening in nutritional risk and status after CRC surgery is very important because this offers the possibility of introducing preventive action, for example through personalized nutritional support. Therefore, the most important observation to emerge from our study is that patients with higher blood NPY concentration, which is orexigenic neuropeptide, had a greater probability of survival during the 1200 days after CRC surgery (

Figure 2). We found also that lower pre-operative serum NPY concentration (< 661.70 pg/ml) can help to identify patients at increased nutritional risk (NRS-2002 score ≥ 3) and with a deterioration in functional status at a 3-month visit after CRC surgery (

Figure 1), probably due to decreased appetite and food intake. Moreover, we also revealed that, compared to patients with low serum NPY concentration, those with higher serum NPY concentration, despite having a similar advancement of CRC, also had more favorable scores in the validated nutrition screening and assessment tools (MNA and PG-SGA), a lower percentage weight loss before surgery (

Table 1), three-times lower likelihood of all-cause perioperative complications (

Table 2), better functional status (Barthel and IADL scales) both before surgery and at the 3-month visit after CRC surgery, and higher SMM indices before surgery (e.g. SM CSA ≥ 92cm

2 at L3) and at the 3-month visit (calf circumference) (

Table 1).

To the best of our knowledge, our report is the first observation of better survival, lower likelihood of perioperative complications, and more favorable nutritional (NRS-2002 score < 3,

Figure 1) and functional outcomes being associated with higher serum NPY concentration in patients after CRC surgery. These favorable associations can be explained by the orexigenic activity of NPY [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

30], and the maintenance of NPY-dependent appetite and food intake in response to an increase in pre- and post-operative catabolism and energy demand.

The clinical importance of our observation is that identifying patients with lower serum NPY concentration is likely to be useful as biomarker in the early identification of patients with a lower survival probability, at increased risk of perioperative complications, at greater nutritional risk (3 months after surgery), and with a likelihood of unplanned weight loss, post-operative sarcopenia, low HGS, and deterioration in everyday functioning. The unfavorable prognosis of patients after CRC surgery being associated with abnormal scoring in nutritional risk scales (e.g., NRS-2002 score ≥ 3 or a low Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index) and a low calf circumference (

Table 1) was previously reported [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. These patients could potentially benefit from nutritional support and/or appetite improvement (e.g. thorough orexigenic substances supplementation) after surgery for CRC. Evidence was previously found that nutritional support using oral nutritional supplements improves patients’ prognosis, prevents post-operative weight and BMI loss, and post-operative sarcopenia, both when applied before surgery as multimodal prehabilitation [

35] and after CRC surgery [

36,

37].

Study limitations and Strength

As with the majority of studies, our analysis has some limitations that may reduce the strength of the conclusions obtained. The small number of patients included in our study and the one-center study design should be considered the main limitations. We did also not monitor food intake and appetite after patient’s discharge, as well as we did not confirm the associations between blood NPY concentration and CRC advancement. Nonetheless, the novelty of this study is unquestionably a strong point: to the best of our knowledge, in the first study worldwide to assess the role of NPY concentration in humans, we revealed the predictive role of higher serum NPY concentration in the identification of patients with a greater likelihood of survival, an almost three times lower risk of perioperative complications, and low nutritional risk (NRS-2002 score < 3) at a 3-month follow-up visit after surgery for CRC. Nevertheless, our observations need to be confirmed in large sample studies.

Conclusions

Higher serum NPY concentration was associated with low nutritional risk and more favorable patient nutritional and functional status both before and after CRC surgery, and almost three times lower risk of perioperative complications, and a greater likelihood of CRC patient’s survival during the 1200 days after CRC surgery. These observations show on the role of appetite and cells-differentiation regulation neuropeptides as prognostic biomarker potentially useful in identification of patients threatened in nutritional and functional status deterioration after CRC surgery.

Author’s contribution

of each author (authorship: e.g. etc.): Jacek Budzyński- study idea, design study, project supervision, practical performance, data collection, data analysis, statistical analysis, literature search, preparation primary version of manuscript, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript. Damian Czarnecki- data analysis, literature search, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Marcin Ziółkowski - data analysis, literature search, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Beata Szukay- data analysis, literature search, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Natalia Mysiak- data analysis, literature search, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Agata Staniewska- data analysis, literature search, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Małgorzata Michalska- laboratory determinations, data analysis, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Ewa Żekanowska- laboratory determinations, data analysis, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript Krzysztof Tojek- design study, project supervision, surgical treatment and management of patients, data collection, data analysis, critical review manuscript, acceptance of final version of manuscript.

Bioethics:

The investigation was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research, after receiving permission from the local Bioethical Committee (No. KB 595/2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Grants and funding

This study was supported by a grant from Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń for scientific research conducted by the Department of Vascular and Internal Diseases.

Conflicts of Interest statement

none declared.

Artificial Intelligence was not used for the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Caramujo-Balseiro S, Faro C, Carvalho L. Metabolic pathways in sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis: A new proposal. Med Hypotheses. 2021, 148, 110512.

- Beirer, A. Malnutrition and cancer, diagnosis and treatment Memo. 2021, 14, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli M, Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Hütterer E, Isenring E, Kaasa S, Krznaric Z, Laird B, Larsson M, Laviano A, Mühlebach S, Oldervoll L, Ravasco P, Solheim TS, Strasser F, de van der Schueren M, Preiser JC, Bischoff SC. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in cancer. Clin Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898-2913.

- Ali R, Baracos VE, Sawyer MB, Bianchi L, Roberts S, Assenat E, Mollevi C, Senesse P. Lean body mass as an independent determinant of dose-limiting toxicity and neuropathy in patients with colon cancer treated with FOLFOX regimens. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 607-616.

- Kasprzak A, Adamek A. The neuropeptide system and colorectal cancer liver metastases: Mechanisms and management. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 3494.

- Appelt AL, Andersen RF, Lindebjerg J, Jakobsen A. Prognostic value of serum NPY hypermethylation in neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020, 43, 9-13.

- Chakroborty D, Goswami S, Fan H, Frankel WL, Basu S, Sarkar C. Neuropeptide Y, a paracrine factor secreted by cancer cells, is an independent regulator of angiogenesis in colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2022, 127, 1440-1449.

- Wu Y, He H, Cheng Z, Bai Y, Ma X. The role of neuropeptide Y and peptide YY in the development of obesity via gut-brain axis. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2019, 20, 750-758.

- Tacad DKM, Tovar AP, Richardson CE, Horn WF, Keim NL, Krishnan GP, Krishnan S. Satiety associated with calorie restriction and time-restricted feeding: Central neuroendocrine integration. Adv Nutr. 2022, 13, 758-791.

- Sánchez ML, Rodríguez FD, Coveñas R. Neuropeptide Y peptide family and cancer: Antitumor therapeutic strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24, 9962.

- Fonseca ICF, Castelo-Branco M, Cavadas C, Abrunhosa AJ. PET imaging of the neuropeptide Y system: A systematic review. Molecules. 2022, 27, 3726.

- de Luis DA, Izaola O, Primo D, Aller R. Different effects of high-protein/low-carbohydrate versus standard hypocaloric diet on insulin resistance and lipid profile: Role of rs16147 variant of neuropeptide Y. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019, 156, 107825.

- Akel Bilgiç H, Gürel ŞC, Ayhan Y, Karahan S, Karakaya İ, Babaoğlu M, Dilbaz N, Uluğ BD, Demir B, Karaaslan Ç. Türkiye Örnekleminde Nöropeptit Y Geni (NPY) Promotor Polimorfizmleri ve Alkol Bağımlılığı Arasındaki İlişki [Relationship between alcohol dependence and neuropeptide Y (NPY) gene promoter polymorphisms in a Turkish sample]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2020, 31, 232-238.

- Kravchychyn ACP, Campos RMDS, Oliveira E Silva L, Ferreira YAM, Corgosinho FC, Masquio DCL, Vicente SECF, Oyama LM, Tock L, de Mello MT, Tufik S, Thivel D, Dâmaso AR. Adipocytokine and appetite-regulating hormone response to weight loss in adolescents with obesity: Impact of weight loss magnitude. Nutrition. 2021, 87-88, 111188.

- Thomsen CB, Hansen TF, Andersen RF, Lindebjerg J, Jensen LH, Jakobsen A Early identification of treatment benefit by methylated circulating tumor DNA in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920918472.

- Abualsaud N, Caprio L, Galli S, Krawczyk E, Alamri L, Zhu S, Gallicano GI, Kitlinska J. Neuropeptide Y/Y5 receptor pathway stimulates neuroblastoma cell motility through RhoA activation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 8, 627090.

- Ding Y, Lee M, Gao Y, Bu P, Coarfa C, Miles B, Sreekumar A, Creighton CJ, Ayala G Neuropeptide Y nerve paracrine regulation of prostate cancer oncogenesis and therapy resistance. Prostate. 2021, 81, 58–71.

- Sigorski D, Wesołowski W, Gruszecka A, Gulczyński J, Zieliński P, Misiukiewicz S, Kitlińska J, Iżycka-Świeszewska E. Neuropeptide Y and its receptors in prostate cancer: Associations with cancer invasiveness and perineural spread. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022, 149, 5803-5822.

- Lin ST, Li YZ, Sun XQ, Chen QQ, Huang SF, Lin S, Cai SQ Update on the role of neuropeptide Y and other related factors in breast cancer and osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12, 705499.

- Raunkilde L, Hansen TF, Andersen RF, Havelund BM, Thomsen CB, Jensen LH NPY gene methylation in circulating tumor DNA as an early biomarker for treatment effect in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 4459.

- Janssens K, Vanhoutte G, Lybaert W, Demey W, Decaestecker J, Hendrickx K, Rezaei Kalantari H, Zwanenpoel K, Pauwels P, Fransen E, Op de Beeck K, Van Camp G, Rolfo C, Peeters M. NPY methylated ctDNA is a promising biomarker for treatment response monitoring in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2023, CCR-22-1500.

- Chen ZG, Ji XM, Xu YX, Fong WP, Liu XY, Liang JY, Tan Q, Wen L, Cai YY, Wang DS, Li YH Methylated ctDNA predicts early recurrence risk in patients undergoing resection of initially unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241230752.

- Overs A, Flammang M, Hervouet E, Bermont L, Pretet JL, Christophe B, Selmani Z. The detection of specific hypermethylated WIF1 and NPY genes in circulating DNA by crystal digital PCR™ is a powerful new tool for colorectal cancer diagnosis and screening. BMC Cancer. 2021, 21, 1092.

- Garrigou S, Perkins G, Garlan F, Normand C, Didelot A, Le Corre D, Peyvandi S, Mulot C, Niarra R, Aucouturier P, Chatellier G, Nizard P, Perez-Toralla K, Zonta E, Charpy C, Pujals A, Barau C, Bouché O, Emile JF, Pezet D, Bibeau F, Hutchison JB, Link DR, Zaanan A, Laurent-Puig P, Sobhani I, Taly V A study of hypermethylated circulating tumor DNA as a universal colorectal cancer biomarker. Clin Chem. 2016, 62, 1129–1139.

- Ogasawara M, Murata J, Ayukawa K, Saiki I Differential effect of intestinal neuropeptides on invasion and migration of colon carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Lett. 1997, 119, 125–130.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019, 48, 16-31.

- Branco MG, Mateus C, Capelas ML, Pimenta N, Santos T, Mäkitie A, Ganhão-Arranhado S, Trabulo C, Ravasco P. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) for the assessment of body composition in oncology: A scoping review. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 4792.

- Feng Y, Cheng XH, Xu M, Zhao R, Wan QY, Feng WH, Gan HT. CT-determined low skeletal muscle index predicts poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7328.

- Budzyński J, Tojek K, Czerniak B, Banaszkiewicz Z. Scores of nutritional risk and parameters of nutritional status assessment as predictors of in-hospital mortality and readmissions in the general hospital population. Clin Nutr. 2016, 35, 1464-1471.

- Shibutani M, Kashiwagi S, Fukuoka T, Iseki Y, Kasashima H, Maeda K. Impact of preoperative nutritional status on long-term survival in patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer. In Vivo. 2023, 37, 1765-1774.

- Wang L, Wu Y, Deng L, Tian X, Ma J. Construction and validation of a risk prediction model for postoperative ICU admission in patients with colorectal cancer: Clinical prediction model study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 222.

- Tang W, Li C, Huang D, Zhou S, Zheng H, Wang Q, Zhang X, Fu J. NRS2002 score as a prognostic factor in solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: A real-world evidence analysis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2024, 25, 2358551.

- Zheng X, Shi JY, Wang ZW, Ruan GT, Ge YZ, Lin SQ, Liu CA, Chen Y, Xie HL, Song MM, Liu T, Yang M, Liu XY, Deng L, Cong MH, Shi HP Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index combined with calf circumference can be a good predictor of prognosis in patients undergoing surgery for gastric or colorectal cancer. Cancer Control. 2024, 31, 10732748241230888.

- Nakamura Y, Kawase M, Kawabata Y, Kanto S, Yamaura T, Kinjo Y, Ogo Y, Kuroda N. Impact of malnutrition on cancer recurrence, colorectal cancer-specific death, and non-colorectal cancer-related death in patients with colorectal cancer who underwent curative surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2024, 129, 317-330.

- Steffens D, Nott F, Koh C, Jiang W, Hirst N, Cole R, Karunaratne S, West MA, Jack S, Solomon MJ. Effectiveness of prehabilitation modalities on postoperative outcomes following colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024.

- Qin X, Sun J, Liu M, Zhang L, Yin Q, Chen S. The effects of oral nutritional supplements interventions on nutritional status in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2024, 30, e13226.

- Pi JF, Zhou J, Lu LL, Li L, Mao CR, Jiang L. A study on the effect of nutrition education based on the goal attainment theory on oral nutritional supplementation after colorectal cancer surgery. Support Care Cancer. 2023, 31, 444.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).