Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods

2.4. Evaluation of the Quality of Research

3. Results

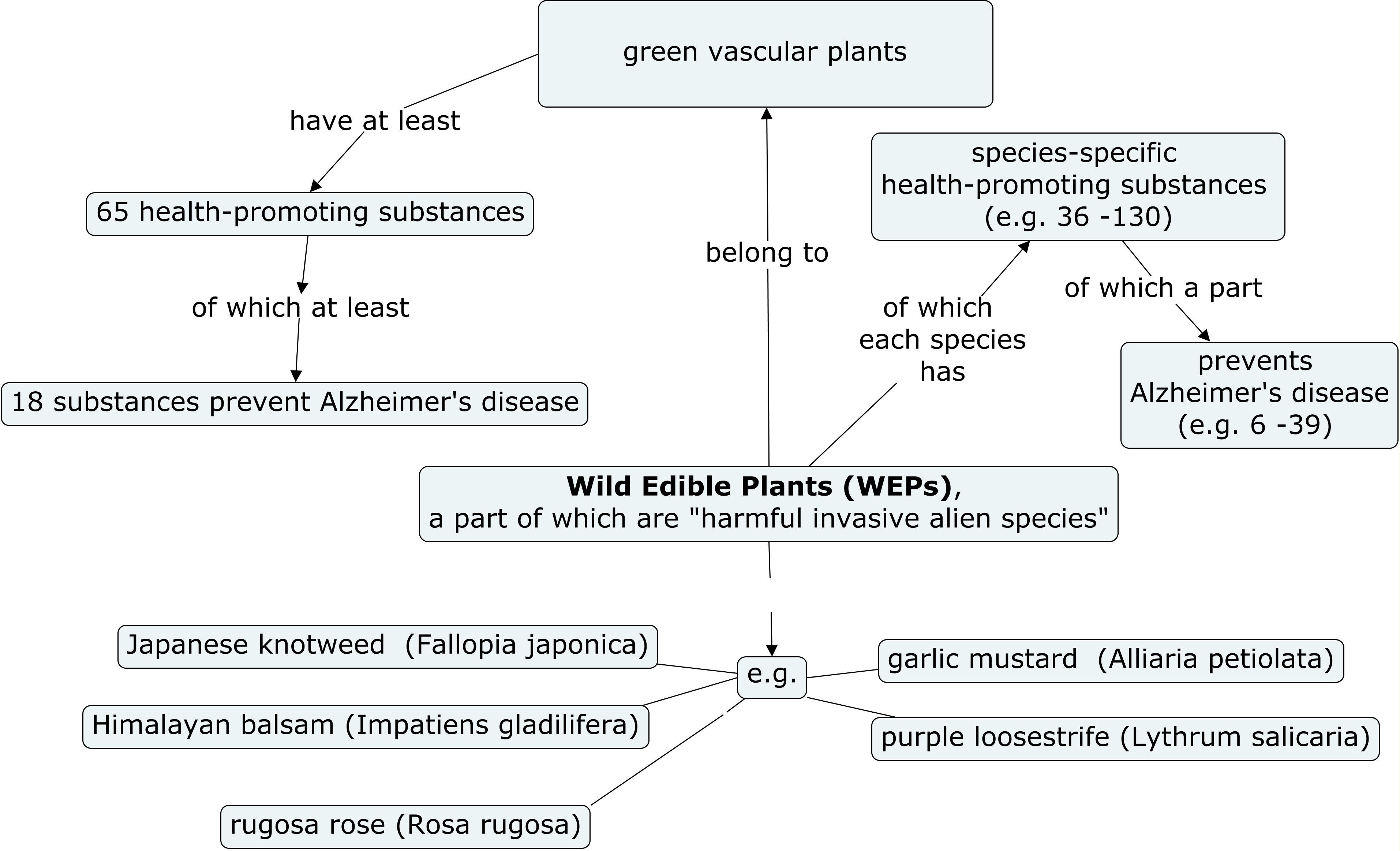

3.1. Research Question (1): How Did I Find 65 Health-Promoting Substances in All Green Vascular WEPs?

3.2. Research Question (2): How Many Alzheimer’s Disease-Preventing Health-Promoting Substances Do All Green Vascular Plants Have, According to Experimental Research?

3.3. How Many Species-Specific Health-Promoting Substances Do Five Selected WEPs Contain?

Discussion

- (1)

- According to Huang & Dudareva (2023), there are over 200 000 plant-specialized metabolites (phytochemicals) involved in plant defense, including terpenoids, alkaloids, glucosinolates, cyanogenic glucosides, phenylpropanoids, and fatty-acid derivatives. All of them except cyanogenic glucosides contain known health-promoting substances (Åhlberg 2019 - 2022b; Tahir & al. 2024).

- (2)

- According to Forterre (2024) and Huang & Dudareva (2023), plants and animals (including humans) have similar metabolic processes. This is why plant-specialized metabolites (phytochemicals) involved in plant defense often protect and promote human health and longevity.

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WEPs | Wild Edible Plants |

| GBIF | Global Biodiversity Information Facility |

References

- hlberg, M. K. (2019). Totuus syötävistä luonnonkasveista eli miksi uskallan syödä lähiluonnon kasveista kestävästi keräämääni ruokaa: OSA I: Tieteellisiä perusteita käytännönläheisesti. (Translated title of the contribution: The truth about wild edible plants - why I am not afraid of eating food that I have made about plants from the local nature that I have foraged sustainably.) Helsinki: Eepinen Oy.

- hlberg, M. K. (2020a). Local Wild Edible Plants (WEP). Practical conclusions from the latest research: Healthy food from local nature. Helsinki: Oy Wild Edibles Ab. International distribution: Amazon.com.

- hlberg, M. K. (2020b). Field guide to local Wild Edible Plants (WEP): practical conclusions from the latest research: healthy food from local nature. Helsinki: Oy Wild Edibles Ab. International distribution: Amazon.com.

- hlberg, M. K. A profound explanation of why eating green (wild) edible plants promotes health and longevity. Food Frontiers. 2021, 2, 240–267. [Google Scholar]

- hlberg, M. K. (2022a). Terveyttä lähiluonnosta [Health from local nature]. Helsinki: Readme. fi. (The book presents 75 common WEPs. Their health-promoting substances are in English.

- hlberg, M. K. (2022b). An update of Åhlberg (2021a): A profound explanation of why eating green (wild) edible plants promotes health and longevity. Food Frontiers 2022, 3, 366–379. [Google Scholar]

- hlberg, M. (2024). The number of health-promoting substances that all edible vascular plants contain compared to the total number of health-promoting substances of five Wild Edible Plants (WEPs). https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202410.1307/v1.

- hlberg, M. (2025). The number of health-promoting substances that all edible vascular plants contain compared to the total number of health-promoting substances of five Wild Edible Plants (WEPs).•. [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A. (2019). Chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Lythrum salicaria- A Review. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy 9(6), 51-59.

- Al-Yafeai, A.; Bellstedt, P.; Böhm, V. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Rosa rugosa Depending on Degree of Ripeness. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anžlovar, S.; Janeš, D.; Koce, J.D. The Effect of Extracts and Essential Oil from Invasive Solidago spp. and Fallopia japonica on Crop-Borne Fungi and Wheat Germination. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 58, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Rico, J.; Macías-León, F.J.; Alanís-García, E.; Cruz-Cansino, N.d.S.; Jaramillo-Morales, O.A.; Barrera-Gálvez, R.; Ramírez-Moreno, E. Study of Edible Plants: Effects of Boiling on Nutritional, Antioxidant, and Physicochemical Properties. Foods 2020, 9, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrington, A. Urban foraging of five non-native plants in NYC: Balancing ecosystem services and invasive species management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 58, 126896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrozi, A.P.; Shukri, S.N.S.; Murshid, N.M.; Shahzalli, A.B.A.; Ngah, W.Z.W.; Damanhuri, H.A.; Makpol, S. Alpha- and Gamma-Tocopherol Modulates the Amyloidogenic Pathway of Amyloid Precursor Protein in an in vitro Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Transcriptional Study. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 846459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Scher, J.M.; Speakman, J.-B.; Zapp, J. Bioactivity guided isolation of antimicrobial compounds from Lythrum salicaria. Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencsik, T. , & al. (2011). Total flavonoid, polyphenol, and tannin contents vary in some Lythrum salicaria populations. Natural Product Communications 6(10), 1417 – 1420. Vol. 6 No. 10 1417 – 1420.

- Blaevi, I. , & Masteli, J. Free and bound volatiles of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Croatica Chemica Acta 2008, 81, 607–613. [Google Scholar]

- Blazevic, I. , & Mastelic, J. (2008). Free and bound volatiles of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Croatica Chemica Acta 81 (4) 607-613.

- Blossey, B. , & al. Developing biological control of Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara and Grande (garlic mustard). Natural Areas Journal 2001, 21, 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Cámara, M. , & al. (2016). Wild edible plants are sources of carotenoids, fibre, phenolics, and non-nutrient bioactive compounds. In de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M., & Tardío, J. (Eds.) Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. ethnobotany and Food Composition Tables. New York: Springer, 187 – 205.

- Capurso, A. The Mediterranean diet: a historical perspective. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavers, P. , & al. ( 1979). The biology of Canadian weeds 35. Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara and Grande. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 59, 217–229.

- Cendrowski, A.; Ścibisz, I.; Mitek, M.; Kieliszek, M.; Kolniak-Ostek, J. Profile of the Phenolic Compounds ofRosa rugosaPetals. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-S.; Hsu, Y.-A.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Lin, E.-S.; Chang, C.-Y.; Chen, J.J.-Y.; Wu, M.-Y.; Lin, H.-J.; Wan, L. Fallopia Japonica and Prunella vulgaris inhibit myopia progression by suppressing AKT and NFκB mediated inflammatory reactions. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, E.; Deligiannidou, G.-E.; Kontogiorgis, C.; Giaginis, C.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Natural Functional Foods as a Part of the Mediterranean Lifestyle and Their Association with Psychological Resilience and Other Health-Related Parameters. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Mathieu, V.; Evidente, M.; Ferderin, M.; Banuls, L.M.Y.; Masi, M.; De Carvalho, A.; Kiss, R.; Evidente, A. Glanduliferins A and B, two new glucosylated steroids from Impatiens glandulifera, with in vitro growth inhibitory activity in human cancer cells. Fitoterapia 2016, 109, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coakley, S.; Petti, C. Impacts of the Invasive Impatiens glandulifera: Lessons Learned from One of Europe’s Top Invasive Species. Biology 2021, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, A.-A.; Baci, G.-M.; Dezsi, Ş.; Nap, M.-E.; Beteg, F.I.; Bonta, V.; Bobiş, O.; Caprio, E.; Dezmirean, D.S. New Approaches on Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) Bioactive Compounds and Their Potential of Pharmacological and Beekeeping Activities: Challenges and Future Directions. Plants 2021, 10, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunja, V.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Weber, N.; Jakopic, J.; Zupan, A.; Veberic, R.; Stampar, F.; Schmitzer, V. Fresh from the Ornamental Garden: Hips of Selected Rose Cultivars Rich in Phytonutrients. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, C369–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashbaldan, S. , & al. ( 2021). Distribution of triterpenoids and steroids in developing rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb.) accessory fruit. Molecules 26, 5158.

- Dawkins, E.; Derks, R.J.; Schifferer, M.; Trambauer, J.; Winkler, E.; Simons, M.; Paquet, D.; Giera, M.; Kamp, F.; Steiner, H. Membrane lipid remodeling modulates γ-secretase processivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M. , & Tardío, J. (Eds.) (2016) Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. ethnobotany and Food Composition Tables. New York: Springer.

- DeRango-Adem, E. & Blay, J. 2021. Does oral apigenin have real potential for a therapeutic effect in the context of human gastrointestinal and other cancers? Frontiers in Pharmacology 12, 681477.

- Dinică, R. , & al. (2010). Quantitative determination of polyphenol compounds from raw extracts of Allium, Alliaria, and Urtica genus. A comparative study. Journal of Faculty of Food Engineering, Ştefan cel Mare University – Suceava 9(4), 85 – 89.

- Dobreva, A.; Nedeltcheva-Antonova, D. Comparative Chemical Profiling and Citronellol Enantiomers Distribution of Industrial-Type Rose Oils Produced in China. Molecules 2023, 28, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, H, & al. (1990). Differences in fragrance chemistry between flower parts of Rosa rugosa Thunb. (Rosaceae). Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 39(1-2), 143-156.

- Dong, N.Q.; Lin, H.X. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, N.S.; Souza, C.d.S.; de Almeida, M.M.A.; da Silva, A.B.; dos Santos, B.L.; Silva, V.D.A.; De Assis, A.M.; da Silva, J.S.; Souza, D.O.; Costa, M.d.F.D.; et al. Neuroimmunomodulatory and Neuroprotective Effects of the Flavonoid Apigenin in in vitro Models of Neuroinflammation Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egebjerg, M. & al. 2018. Are wild and cultivated flowers served in restaurants or sold by local producers in Denmark safe for the consumer? Food and Chemical Toxicology 120, 129-142.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (2025). Alkaloid. https://www.britannica.com/science/alkaloid. Retrieved 14.2.2025.

- EU CONTAM (2017). Scientific opinion: Erucic acid in feed and food. EFSA Journal 2016; 14(11): 4593. The scientific opinion was adopted: on 21.9.2016, and the amended version was readopted on 5.4.2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2022a). Invasive alien species. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/invasivealien/list/index_en.htm.

- European Commission (2022b). Annex. List of invasive alien species of Union concern. Retrieved 10.2.2023, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?

- Feng, L.; Chen, C.; Li, T.; Wang, M.; Tao, J.; Zhao, D.; Sheng, L. Flowery odor formation revealed by differential expression of monoterpene biosynthetic genes and monoterpene accumulation in rose (Rosa rugosa Thunb.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M. , & al. (1958). Edible wild plants of eastern North America. New York: Harper & Row.

- Forterre, P. The Last Universal Common Ancestor of Ribosome-Encoding Organisms: Portrait of LUCA. J. Mol. Evol. 2024, 92, 550–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, T.; Motawia, M.S.; Olsen, C.E.; Agerbirk, N.; Møller, B.L.; Bjarnholt, N. Diversified glucosinolate metabolism: biosynthesis of hydrogen cyanide and of the hydroxynitrile glucoside alliarinoside in relation to sinigrin metabolism in Alliaria petiolata. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanty, A.; Grudzińska, M.; Paździora, W.; Paśko, P. Erucic Acid—Both Sides of the Story: A Concise Review on Its Beneficial and Toxic Properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF (2023). The distribution map of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is based on museum data and observations (538,402 occurrences). Retrieved 26.5.2023 from https://www.gbif.org/species/3188736.

- Girardi, J.P.; Korz, S.; Muñoz, K.; Jamin, J.; Schmitz, D.; Rösch, V.; Riess, K.; Schützenmeister, K.; Jungkunst, H.F.; Brunn, M. Nitrification inhibition by polyphenols from invasive Fallopia japonica under copper stress. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2022, 185, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, A. , & al. Erucic acid: a possible therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative diseases. Current Molecular Medicine published online 9.5. 2023.

- Grieve, M. (1959). A modern herbal. Volume 2. New York: Hafner Publishing.

- Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Recent advances in the medical applications of hemostatic materials. Theranostics 2023, 13, 161–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harborne, J.B. Arsenal for survival: secondary plant products. Taxon 2000, 49, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, P.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F. Plant Nutrition for Human Nutrition: Hints from Rice Research and Future Perspectives. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haribal, M.; Renwick, J.A.A. Seasonal and Population Variation in Flavonoid and Alliarinoside Content of Alliaria petiolata. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M. ,&al. ( 2022). Effects of intraspecific density and plant size on garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) sinigrin concentration. Biological Invasions 24, 3785–3797.

- Hill, S. 2024. Changing research policy and practice with evidence: the relationships between meta-research and its stakeholders. In Oancea, A. & al. (Eds.) 2024. Handbook of Meta-Research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 90–103.

- Hoover, A.A.; Wijesinha, G.S. Influence of pH and Salts on the Solubility of Calcium Oxalate. Nature 1945, 155, 638–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, P.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F. Plant Nutrition for Human Nutrition: Hints from Rice Research and Future Perspectives. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.-Q.; Dudareva, N. Plant specialized metabolism. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R473–R478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iancu, I. , & al. (2021). Phytochemical evaluation and cytotoxicity assay of Lythri herba extracts. ( 69(1), 51–58.

- Ivanova, T. , & al. (2023). Catching the green - diversity of ruderal spring plants traditionally consumed in Bulgaria and their potential benefit for human health. Diversity 15, 435.

- Jiang, B. , & al. Chemical constituents from Lythrum salicaria L. Journal of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015, 50, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Kalemba-Drożdż, M. , & Ciernia, A. Antioxidant and genoprotective properties of extracts from edible flowers. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2018, 58, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kallas, J. , (2023). Wild edible plants. Wild foods from foraging to feasting. Layton: Gibbs Smith.

- Kanmaz, O.; Şenel, T.; Dalfes, H.N. A Modeling Framework to Frame a Biological Invasion: Impatiens glandulifera in North America. Plants 2023, 12, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National list of harmful invasive alien species. (2023). Retrieved June 20, 2023, from Invasive Alien Species – Invasive Alien Species Portal (vieraslajit.fi).

- Katekar, V.P.; Rao, A.B.; Sardeshpande, V.R. Review of the rose essential oil extraction by hydrodistillation: An investigation for the optimum operating condition for maximum yield. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayahan, S.; Ozdemir, Y.; Gulbag, F. Functional Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Rosa Species Grown In Turkey. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2022, 65, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Li, M.-T.; Xu, S.; Ma, J.; Liu, M.-Y.; Han, Y. Advances for pharmacological activities of Polygonum cuspidatum - A review. Pharm. Biol. 2023, 61, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelager, A.; Pedersen, J.S.; Bruun, H.H. Multiple introductions and no loss of genetic diversity: invasion history of Japanese Rose, Rosa rugosa, in Europe. Biol. Invasions 2012, 15, 1125–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ko, H.J.; Jeon, S.J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.E.; Kim, H.N.; Woo, E.-R.; Ryu, J.H. The memory-enhancing effect of erucic acid on scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2016, 142, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. , & al. (2022). Variations in the antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties of different Rosa rugosa organ extracts. 12, 238.

- Kim, H. (2020). Metabolism in plants. Plants 9(7), 871, 1–4.

- Kim, H. , & al. (2022). Analysis of components in the different parts of Lythrum salicaria L.

- Journal of the Korean Herbal Medicine Society 37(5), 89-96.

- Kim, M.; Jung, J.; Jeong, N.Y.; Chung, H.-J. The natural plant flavonoid apigenin is a strong antioxidant that effectively delays peripheral neurodegenerative processes. Anat. Sci. Int. 2019, 94, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.W.; Kang, J.-H.; Jung, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Le Phan, T.H.; Namgung, H.; Seo, S.-Y.; Yoon, Y.S.; Oh, S.H. Allyl Isothiocyanate Protects Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury via NRF2 Activation by Decreasing Spontaneous Degradation in Hepatocyte. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewicka, E.; Piekarska-Radzik, L.; Milala, J.; Klewicki, R.; Sójka, M.; Rosół, N.; Otlewska, A.; Matysiak, B. Antagonistic Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Rosa rugosa Thunb. Pseudo-Fruit Extracts against Staphylococcus spp. Strains. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, D. , & Chen, G. (2021). The invasive species Alliaria petiolata threatens forest understories as it alters soil nutrients and microbial composition, thereby changing the local plant community. Journal of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science (2020) 94(1-2): 73–90.

- Kurita, D. , & al. (2016). Identification of neochlorogenic acid as the predominant antioxidant in Polygonum cuspidatum leaves. Italian Journal of Food Science 28, 25 – 31.

- Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Wojdyło, A.; Cebulak, T.; Hirnle, L.; Siewiński, M. UPLC-PDA-Q/TOF-MS identification of bioactive compounds and on-line UPLC-ABTS assay in Fallopia japonica Houtt and Fallopia sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) leaves and rhizomes grown in Poland. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 245, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, S. , & Oszmiański, J. Profile of bioactive compounds in the morphological parts of wild Fallopia japonica (Houtt) and Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) and their antioxidative activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 1436. [Google Scholar]

- Lachowicz, S. , & Oszmiański, J. Profile of bioactive compounds in the morphological parts of wild Fallopia japonica (Houtt) and Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) and their antioxidative activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 1436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Wang, C. Medicinal Components and Pharmacological Effects of Rosa rugosa. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2018, 12, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupoae, M. , & al. (2010). Quantification of carotenoids and chlorophyll leaf pigments from autochthones dietary. Food and Environment Safety - Journal of Faculty of Food Engineering, Ştefan cel Mare University – Suceava 9(4), 42 – 47.

- Maciąg, A.; Kalemba, D. Composition of rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa thunb.) hydrolate according to the time of distillation. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjiro, K. , & al. 2008. Effects of Rosa rugosa petals on intestinal bacteria. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 72(3), 773-777.

- Manayi, A. , & al. (2013). Cytotoxic effect of the main compounds of Lythrum salicaria L. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 68(9-10), 367-375.

- Manayi, A. , & al. (2014). Comparative study of the essential oil and hydrolate composition of Lythrum salicaria L. obtained by hydro-distillation and microwave distillation methods. Research Journal of Pharmacognosy 1(2), 33-38.

- Marrelli, A. , & al. (2020). A review of biologically active natural products from Mediterranean wild edible plants: benefits in the treatment of obesity and its related disorders. Molecules 25(3), 649.

- Martin, L.J.; Touaibia, M. Improvement of Testicular Steroidogenesis Using Flavonoids and Isoflavonoids for Prevention of Late-Onset Male Hypogonadism. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medveckienė, B. ,&al. Effect of harvesting in different ripening stages on the content of the mineral elements of rosehip (Rosa spp.) fruit flesh. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 467. [Google Scholar]

- Medveckienė, B. ,&al. Changes in pomological and physical parameters in rosehips during ripening. Plants 2023, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. ,&al. (2022). HPLC-DAD-MS identification and quantification of phenolic components in Japanese knotweed and American pokeweed extracts and their phytotoxic effect on seed germination. Plants 2022, 11, 3053. [Google Scholar]

- Milala, J. ,&al. Rosa spp. extracts as a factor that limits the growth of Staphylococcus spp. bacteria, a food contaminant. Molecules 2021, 26, 4590. [Google Scholar]

- Milanović, M. ,&al. ( 2020). Linking traits of invasive plants with ecosystem services and disservices. Ecosystem Services 42, 101072.

- Mira, S.; Nadarajan, J.; Liu, U.; González-Benito, M.E.; Pritchard, H.W. Lipid Thermal Fingerprints of Long-term Stored Seeds of Brassicaceae. Plants 2019, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molgaar, P. (1986). Food plant preferences by slugs and snails: a simple method to evaluate the relative palatability of the food plants. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 14(1), 113-121.

- Monari, S.; Ferri, M.; Montecchi, B.; Salinitro, M.; Tassoni, A. Phytochemical characterization of raw and cooked traditionally consumed alimurgic plants. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0256703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Paura, B.; Cozzolino, A.; de Falco, B. Edible Flowers Used in Some Countries of the Mediterranean Basin: An Ethnobotanical Overview. Plants 2022, 11, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattagh-Eshtivani, E.; Barghchi, H.; Pahlavani, N.; Barati, M.; Amiri, Y.; Fadel, A.; Khosravi, M.; Talebi, S.; Arzhang, P.; Ziaei, R.; et al. Biological and pharmacological effects and nutritional impact of phytosterols: A comprehensive review. Phytotherapy Res. 2021, 36, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.B.; Gao, W.; Li, L.; Niu, S.M.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Shi, L.S.; Fu, M.; Liu, F. Rose (Rosa rugosa)-flower extract increases the activities of antioxidant enzymes and their gene expression and reduces lipid peroxidation. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 83, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijat, D.; Lu, C.-F.; Lu, J.-J.; Abdulla, R.; Hasan, A.; Aidarhan, N.; Aisa, H. Spectrum-effect relationship between UPLC fingerprints and antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of Rosa rugosa. J. Chromatogr. B 2021, 1179, 122843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R. (2005) Chemical composition of hips essential oils of some Rosa L. species. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 60(5-6), 369-378.

- Nowak, R. Determination of ellagic acid in pseudofruits of some species of roses. 2007, 63, 289–92. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, R.; Olech, M.; Pecio, Ł.; Oleszek, W.; Los, R.; Malm, A.; Rzymowska, J. Cytotoxic, antioxidant, antimicrobial properties and chemical composition of rose petals. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 94, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech, M.; Nowak, R.; Pecio, Ł.; Łoś, R.; Malm, A.; Rzymowska, J.; Oleszek, W. Multidirectional characterisation of chemical composition and health-promoting potential of Rosa rugosa hips. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 31, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech, M. , & al. (2019). Polysaccharide-rich fractions from Rosa rugosa Thunb. —Composition and chemopreventive potential. Molecules, 24(7), 1354.

- Olech, M.; Cybulska, J.; Nowacka-Jechalke, N.; Szpakowska, N.; Masłyk, M.; Kubiński, K.; Martyna, A.; Zdunek, A.; Kaczyński, Z. Novel polysaccharide and polysaccharide-peptide conjugate from Rosa rugosa Thunb. pseudofruit – Structural characterisation and nutraceutical potential. Food Chem. 2022, 409, 135264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oancea, A. & al.(Eds.) 2024. Handbook of Meta-Research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Orzelska-Górka, J.; Szewczyk, K.; Gawrońska-Grzywacz, M.; Kędzierska, E.; Głowacka, E.; Herbet, M.; Dudka, J.; Biała, G. Monoaminergic system is implicated in the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside and protocatechuic acid isolated from Impatiens glandulifera Royle in mice. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 128, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, Y. Ethnobotanical review of traditional use of wild food plants in Japan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2024, 20, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paura, B. , & Marzio, P. (2022). Making a virtue of necessity: the use of wild edible plant species (also toxic) in bread making in times of famine according to Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (1766). Biology, 11(2).

- Pirvu, L.; Hlevca, C.; Nicu, I.; Bubueanu, C. Comparative studies on analytical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of a series of vegetal extracts prepared from eight plant species growing in Romania. JPC – J. Planar Chromatogr. – Mod. TLC 2014, 27, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarski, J. , & al. (2015). Lythrum salicaria L.—Underestimated medicinal plant from European traditional medicine. A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 170, 226-250.

- Prđun, S.; Flanjak, I.; Svečnjak, L.; Primorac, L.; Lazarus, M.; Orct, T.; Bubalo, D.; Rajs, B.B. Characterization of Rare Himalayan Balsam (Impatiens glandulifera Royle) Honey from Croatia. Foods 2022, 11, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem (2015) Description of alkaloids. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/alkaloid. Retrieved 14.2.2025.

- Rahman, M.; Khatun, A.; Liu, L.; Barkla, B.J. Brassicaceae Mustards: Traditional and Agronomic Uses in Australia and New Zealand. Molecules 2018, 23, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M. , & al. (2022). Rosa davurica Pall., Rosa rugosa Thumb., and Rosa acicularis Lindl. Originating from Far Eastern Russia: Screening of 146 Chemical Constituents in Three Species of the Genus Rosa. Applied Sciences, 12, 9401.

- Repsold, B.P.; Malan, S.F.; Joubert, J.; Oliver, D.W. Multi-targeted directed ligands for Alzheimer’s disease: design of novel lead coumarin conjugates. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2018, 29, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, V.L.; E Scanga, S.; Kolozsvary, M.B.; E Garneau, D.; Kilgore, J.S.; Anderson, L.J.; Hopfensperger, K.N.; Aguilera, A.G.; A Urban, R.; Juneau, K.J. Where Is Garlic Mustard? Understanding the Ecological Context for Invasions of Alliaria petiolata. BioScience 2022, 72, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Humagain, K.; Pearson, A. Mapping the purple menace: spatiotemporal distribution of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) along roadsides in northern New York State. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajna, N. Habitat Preference Within Its Native Range and Allelopathy of Garlic Mustard Alliaria petiolata. Pol. J. Ecol. 2017, 65, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, M. , & al. (2023). Diagnosing wild species harvest - resource use and conservation. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Seal, T.; Pillai, B.; Chaudhuri, K. EFFECT OF COOKING METHODS ON TOTAL PHENOLICS AND ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY OF SELECTED WILD EDIBLE PLANTS. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergio, L.; Boari, F.; Pieralice, M.; Linsalata, V.; Cantore, V.; Di Venere, D. Bioactive Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity of Some Wild Edible Greens as Affected by Different Cooking Treatments. Foods 2020, 9, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, Y.J.; Shin, M.K.; Jung, J.; Koo, B.; Jang, W. An in-silico approach to studying a very rare neurodegenerative disease using a disease with higher prevalence with shared pathways and genes: Cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy and Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 996698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. , & Gairola, S. (2023). Nutritional potential of wild edible rose hips in India for food security. In A. Kumar & al. (Eds.), Agriculture, Plant Life and Environment Dynamics (pp. 163–179). Springer, Singapore.

- Sirše, M. Effect of Dietary Polyphenols on Osteoarthritis—Molecular Mechanisms. Life 2022, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrypnik, L. , &al. Evaluation of the rose hips of Rosa canina L. and Rosa rugosa Thunb. as a valuable source of biological active compounds and antioxidants on the Baltic Sea coast. Polish Journal of Natural Sciences 2019, 34, 395–413. [Google Scholar]

- Srećković, N.; Stanković, J.S.K.; Matić, S.; Mihailović, N.R.; Imbimbo, P.; Monti, D.M.; Mihailović, V. Lythrum salicaria L. (Lythraceae) as a promising source of phenolic compounds in the modulation of oxidative stress: Comparison between aerial parts and root extracts. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Szablewski, T.; Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Szwajkowska-Michałek, L.; Krzyżaniak, M.; Świerk, D.; Cegielska-Radziejewska, R.; Krejpcio, Z. Antimicrobial Activities Evaluation and Phytochemical Screening of Some Selected Plant Materials Used in Traditional Medicine. Molecules 2022, 28, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulborska, A.; Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; Chwil, M. Micromorphology of Rosa rugosa Thunb. petal epidermis secreting fragrant substances. Acta Agrobot. 2012, 65, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šutovská, M.; Capek, P.; Fraňová, S.; Pawlaczyk, I.; Gancarz, R. Antitussive and bronchodilatory effects of Lythrum salicaria polysaccharide-polyphenolic conjugate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K.; Kalemba, D.; Komsta, Ł.; Nowak, R. Comparison of the Essential Oil Composition of Selected Impatiens Species and Its Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K.; Olech, M. Optimization of extraction method for LC–MS based determination of phenolic acid profiles in different Impatiens species. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 20, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K.; Bonikowski, R.; Maciąg-Krajewska, A.; Abramek, J.; Bogucka-Kocka, A. Lipophilic components and evaluation of the cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of Impatiens glandulifera Royle and Impatiens noli – tangere L. (Balsaminaceae). Grasas y Aceites 2018, 69, e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, K.; Kalemba, D.; Komsta, Ł.; Nowak, R. Comparison of the Essential Oil Composition of Selected Impatiens Species and Its Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, K. , & al. (2019b). SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL: Phenolic constituents of the aerial parts of Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae) and their antioxidant activities. Natural Product Research, 33(19).

- hretoğlu, D. , & al. Recent advances in chemistry, therapeutic properties and sources of polydatin. Phytochemistry Reviews 2018, 17, 973–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, F.; Ali, E.; Hassan, S.A.; Bhat, Z.F.; Walayat, N.; Nawaz, A.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Khan, M.R.; Aadil, R.M. Cyanogenic glucosides in plant-based foods: Occurrence, detection methods, and detoxification strategies – A comprehensive review. Microchem. J. 2024, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Ishizaki, M.; Kimira, Y.; Egashira, Y.; Hirai, S. Erucic Acid-Rich Yellow Mustard Oil Improves Insulin Resistance in KK-Ay Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallberg, S. , Lehmuskallio, E. & Lehmuskallio, J. 2023. The forager’s cookbook Flora. Helsinki: Superluonnollinen Oy.

- Thakur, M. , & al. (2020). Phytochemicals: Extraction process, safety assessment, toxicological evaluations, and regulatory issues. In B. Prakash (Ed.), Functional and Preservative properties of Phytochemicals (pp. 341-361).

- The Local Food-Nutraceuticals Consortium. (2005). Understanding local Mediterranean diets: A multidisciplinary pharmacological and ethnobotanical approach. 2005.

- Tong, X.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Sui, Y.; Shen, J.; Feng, J. Effects of antibiotics on nitrogen uptake of four wetland plant species grown under hydroponic culture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 10621–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunalier, Z.; Koşar, M.; Küpeli, E.; Çaliş, I.; Başer, K.H.C. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive activities and composition of Lythrum salicaria L. extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.N.; Winterhalter, P.; Jerz, G. Flavonoids from the flowers of Impatiens glandulifera Royle isolated by high performance countercurrent chromatography. Phytochem. Anal. 2016, 27, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volinia, P.; Mattalia, G.; Pieroni, A. Foraging Educators as Vectors of Environmental Knowledge in Europe. J. Ethnobiol. 2024, 44, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of medicinal plants from Rosa genus. 2022, 14, 187–209. [CrossRef]

- Wens, A. & Geuens, J. 2022. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of plant extracts against common phytopathogenic fungi. Journal of Bioscience and Biotechnology 11(1), 15-21.

- WFO (2023): World Flora Online. Published on the Internet; http://www.worldfloraonline.org. Accessed on: 27 May 2023.

- Wu, X. , & al. (2009). Are isothiocyanates potential anti-cancer drugs? Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 30, 501–512.

- Wu, Y.; Colautti, R.I. Evidence for continent-wide convergent evolution and stasis throughout 150 y of a biological invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J. ,&al. Chemical compounds, anti-aging and antibacterial properties of Rosa rugosa purple branch. Industrial Crops & Products 2022, 181, 114814. [Google Scholar]

- Zennie, T.M.; Ogzewalla, D. Ascorbic acid and Vitamin A content of edible wild plants of Ohio and Kentucky. Econ. Bot. 1977, 31, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, F.; Li, R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Liang, Q. Purification, characterization, antioxidant and moisture-preserving activities of polysaccharides from Rosa rugosa petals. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , & al. Novel functional food from an invasive species Polygonum cuspidatum: safety evaluation, chemical composition, and hepatoprotective effects. Food Quality and Safety 2022, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Sun, Y.; Luo, L.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C. Road to a bite of rosehip: A comprehensive review of bioactive compounds, biological activities, and industrial applications of fruits. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 136, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WEP species, aerial parts | Total number of health-promoting substances |

| Rosa rugosa petals | 195 (65+130) |

| Rosa rugosa hips | 165 (65+100) |

| Lythrum salicaria | 162 (65+97) |

| Fallopia japonica | 142 (65+77) |

| Impatiens glandulifera | 137 (65+72) |

| Alliaria petiolata | 101 (65+36) |

| WEP species, aerial parts | the number of substances preventing Alzheimer’s disease |

| Fallopia japonica | 57 (18+39) |

| Impatiens glandulifera | 46 (18+28) |

| Lythrum salicaria | 41 (18+23) |

| Rosa rugosa hips | 39 (18+21) |

| Rosa rugosa petals | 35 (18+17) |

| Alliaria petiolata | 24 (18+6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).