Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Tools

2.4. Piloting

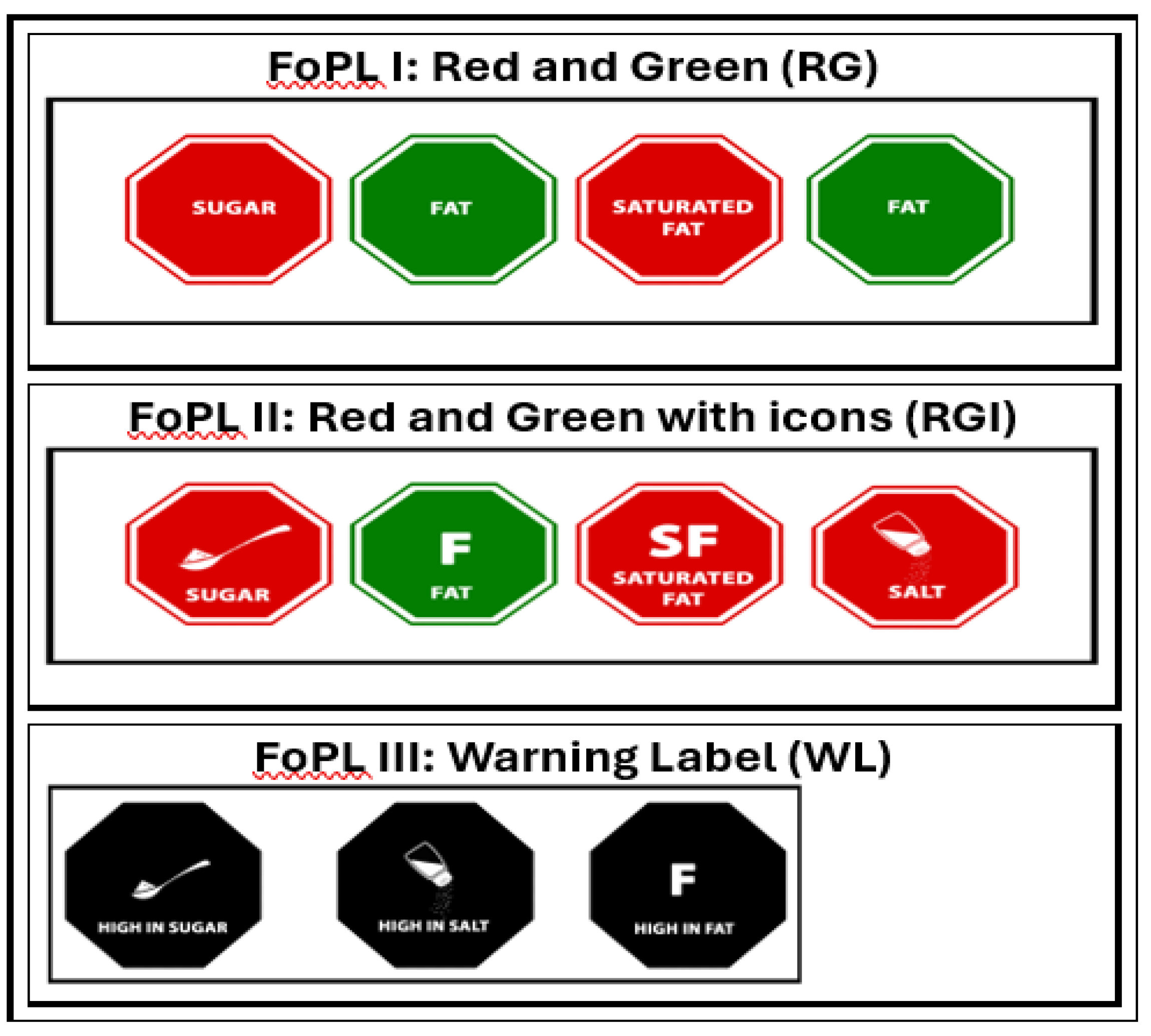

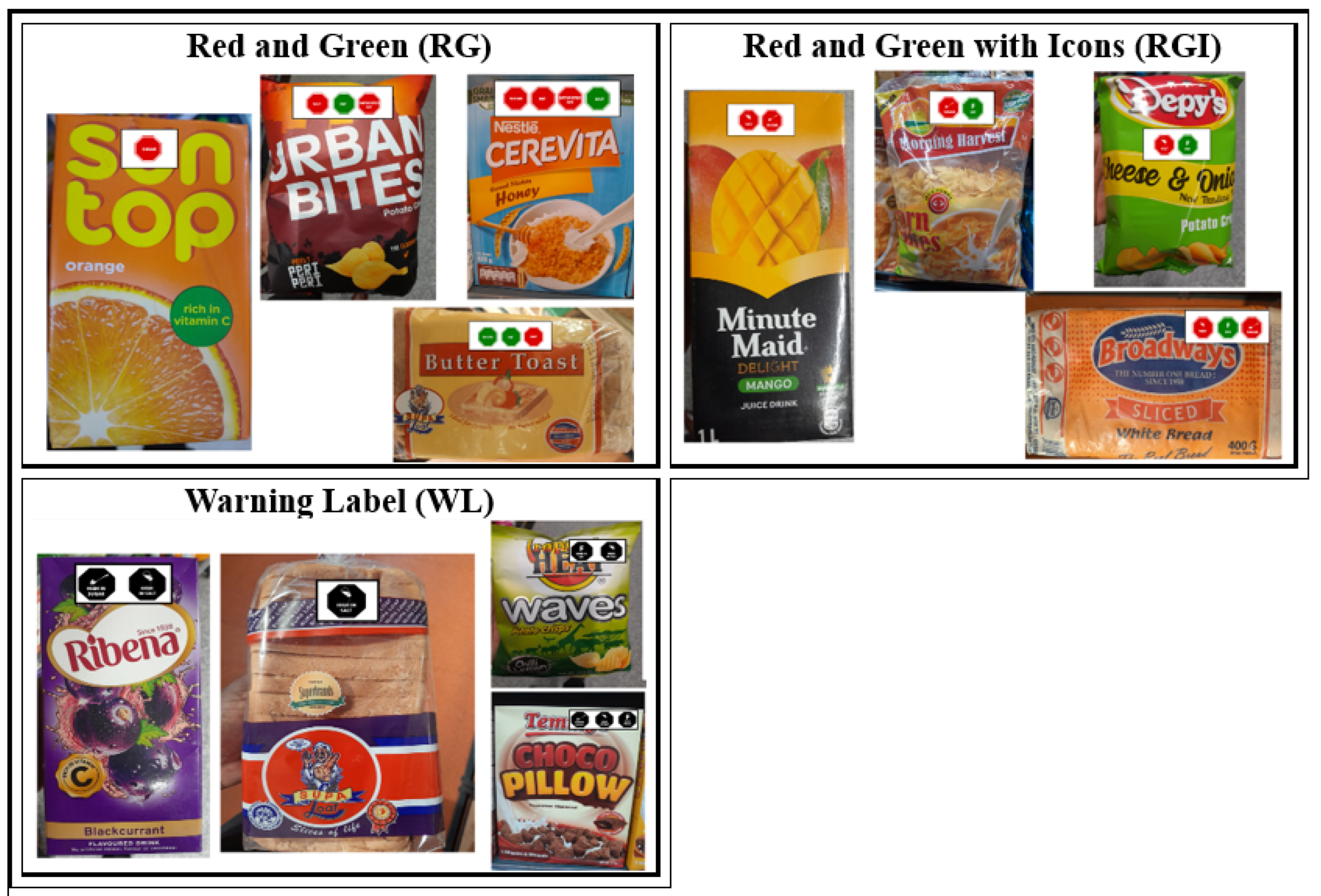

2.5. FoPL Prototypes Tested

2.6. FoPL’s Tested

2.7. FoPL Testing Procedures

2.8. Study Procedures

2.8.1. Focus Group Discussions

2.8.2. Data Collection

2.8.3. Ethical Considerations

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Socio-Demographics

3.2. Themes

3.3. Visibility and Memorability

3.4. Comprehensibility

3.5. Potential Effectiveness

3.6. Cultural Appropriateness

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix 1: Focus Group Discussion Guide

References

- Ministry of Health, K. National Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases [Internet]. 2021. Available online: www.health.go.ke.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease 2021 Findings from the GBD 2021 Study. 2021;

- Elizabeth L, Machado P, Zinöcker M, Baker P, Lawrence M. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 30;12(7):1955. [CrossRef]

- Crosbie E, Gomes FS, Olvera J, Rincón-Gallardo Patiño S, Hoeper S, Carriedo A. A policy study on front–of–pack nutrition labeling in the Americas: emerging developments and outcomes. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas. 2023 Feb;18:100400. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Implementing Nutrition Labelling Policies; A review of contextual factors. 2021.

- Muller L, Ruffieux B. What Makes a Front-of-Pack Nutritional Labelling System Effective: The Impact of Key Design Components on Food Purchases. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 19;12(9):2870. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children Fund. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: A “How-to” Guide for Countries. 2021.

- Vargas-Meza J, Jáuregui A, Pacheco-Miranda S, Contreras-Manzano A, Barquera S. Front-of-pack nutritional labels: Understanding by low- And middle-income Mexican consumers. PLoS One. 2019 Nov 1;14(11). [CrossRef]

- Méjean C, Macouillard P, Péneau S, Hercberg S, Castetbon K. Perception of front-of-pack labels according to social characteristics, nutritional knowledge and food purchasing habits. Public Health Nutr. 2013 Mar 27;16(3):392–402. [CrossRef]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007 Sep 16;19(6):349–57. [CrossRef]

- Bopape M, Taillie LS, Frank T, Murukutla N, Cotter T, Majija L, et al. South African consumers’ perceptions of front-of-package warning labels on unhealthy foods and drinks. PLoS One. 2021 Sep 27;16(9):e0257626. [CrossRef]

- Temple NJ, Fraser J. Food labels: A critical assessment. Nutrition. 2014 Mar;30(3):257–60. [CrossRef]

- Dana LM, Chapman K, Talati Z, Kelly B, Dixon H, Miller C, et al. Consumers’ Views on the Importance of Specific Front-of-Pack Nutrition Information: A Latent Profile Analysis. Nutrients. 2019 May 23;11(5):1158. [CrossRef]

- Grunert KG, Wills JM, Fernández-Celemín L. Nutrition knowledge, and use and understanding of nutrition information on food labels among consumers in the UK. Appetite. 2010 Oct;55(2):177–89. [CrossRef]

- Machín L, Aschemann-Witzel J, Curutchet MR, Giménez A, Ares G. Does front-of-pack nutrition information improve consumer ability to make healthful choices? Performance of warnings and the traffic light system in a simulated shopping experiment. Appetite. 2018 Feb;121:55–62. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha A, Cullerton K, White KM, Mays J, Sendall M. Impact of front-of-pack nutrition labelling in consumer understanding and use across socio-economic status: A systematic review. Appetite. 2023 Aug;187:106587. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Ouyang Y, Yin X, Bai J, Zhang R, Zhang J, et al. Consumers’ Perceptions of the Design of Front-of-Package Warning Labels—A Qualitative Study in China. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 13;15(2):415. [CrossRef]

- Roberto CA, Ng SW, Ganderats-Fuentes M, Hammond D, Barquera S, Jauregui A, et al. The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling on Consumer Behavior and Product Reformulation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2021 Oct 11;41(1):529–50. [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew S, Jongenelis MI, Lakshmi JK, Johnson C, Mahajan P, Praveen D, et al. Developing and testing front-of-pack nutrition labels in India: An experimental study. Food Qual Prefer. 2023 Dec;112:105025. [CrossRef]

- Jones A, Neal B, Reeve B, Ni Mhurchu C, Thow AM. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling to promote healthier diets: current practice and opportunities to strengthen regulation worldwide. BMJ Glob Health. 2019 Dec;4(6):e001882. [CrossRef]

- de Morais Sato P, Mais LA, Khandpur N, Ulian MD, Bortoletto Martins AP, Garcia MT, et al. Consumers’ opinions on warning labels on food packages: A qualitative study in Brazil. PLoS One. 2019 Jun 26;14(6):e0218813. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz DC, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving Cultural Appropriateness in Health Promotion Programs: Targeted and Tailored Approaches. Health Education & Behavior. 2003 Apr 1;30(2):133–46. [CrossRef]

- Becker MW, Bello NM, Sundar RP, Peltier C, Bix L. Front of pack labels enhance attention to nutrition information in novel and commercial brands. Food Policy. 2015 Oct;56:76–86. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. State of play of WHO guidance on Front-of-the-Pack labelling. 2021.

| County | Region | Number of participants | SES | Urban-rural location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nairobi | Langata | 11 | Mid-high | Urban |

| Embakasi | 23 | Low | Urban | |

| Mombasa | Mvita | 10 | Mid-high | Urban |

| Kisauni | 22 | Low | Rural | |

| Kisumu | Kisumu Central | 24 | Mid-high | Urban |

| Nyando | 12 | Low | Rural | |

| Garissa | Garissa Township | 20 | Mid-high | Urban |

| Fafi | 15 | Low | Rural |

| Variables | Nairobi (N=34) | Kisumu (N=36) | Mombasa (N=32) | Garissa (N=35) | Total (N=137) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 17 (50.0%) | 18 (50.0%) | 16 (50.0%) | 20 (57.1%) | 71 (51.8%) |

| Female | 17 (50.0%) | 18 (50.0%) | 16 (50.0%) | 15 (42.9%) | 66 (48.2%) |

| Age category | |||||

| 18 - 29 years | 17 (50.0%) | 16 (44.4%) | 19 (59.4%) | 22 (62.9%) | 74 (54.0%) |

| 30 - 50 years | 17 (50.0%) | 20 (55.6%) | 13 (40.6%) | 13 (37.1%) | 63 (46.0%) |

| Education level | |||||

| No Primary school | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (14.3%) | 5 (3.6%) |

| Primary school | 8 (23.5%) | 12 (33.3%) | 2 (6.2%) | 4 (11.4%) | 26 (19.0%) |

| Secondary | 12 (35.3%) | 10 (27.8%) | 6 (18.8%) | 18 (51.4%) | 46 (33.6%) |

| College/University | 14 (41.2%) | 13 (36.1%) | 23 (71.9%) | 7 (20.0%) | 57 (41.6%) |

| Postgraduate school | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (3.1%) | 1 (2.9%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| Parent or caregiver for children aged below 18? | |||||

| No | 6 (17.6%) | 4 (11.1%) | 18 (56.2%) | 29 (82.9%) | 57 (41.6%) |

| Yes | 28 (82.4%) | 32 (88.9%) | 14 (43.8%) | 6 (17.1%) | 80 (58.4%) |

| Main decision-maker for food purchases | |||||

| No | 9 (26.5%) | 3 (8.3%) | 9 (28.1%) | 22 (62.9%) | 43 (31.4%) |

| Yes | 25 (73.5%) | 33 (91.7%) | 23 (71.9%) | 13 (37.1%) | 94 (68.6%) |

| Main buyer of food | |||||

| Yes | 21 (61.8%) | 29 (80.6%) | 23 (71.9%) | 13 (37.1%) | 86 (62.8%) |

| Shared responsibility | 13 (38.2%) | 7 (19.4%) | 6 (18.8%) | 12 (34.3%) | 38 (27.7%) |

| Not the main buyer | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (9.4%) | 10 (28.6%) | 13 (9.5%) |

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|

Colour |

| Shape | |

| Text | |

| Memorability | |

|

Ease of understanding |

| Purpose and audience of symbol | |

| Clarity and confusion | |

| Label message | |

|

Shift on purchase intention |

| Effect of symbol on diet related NCDs | |

|

Cultural appropriateness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).