Submitted:

13 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

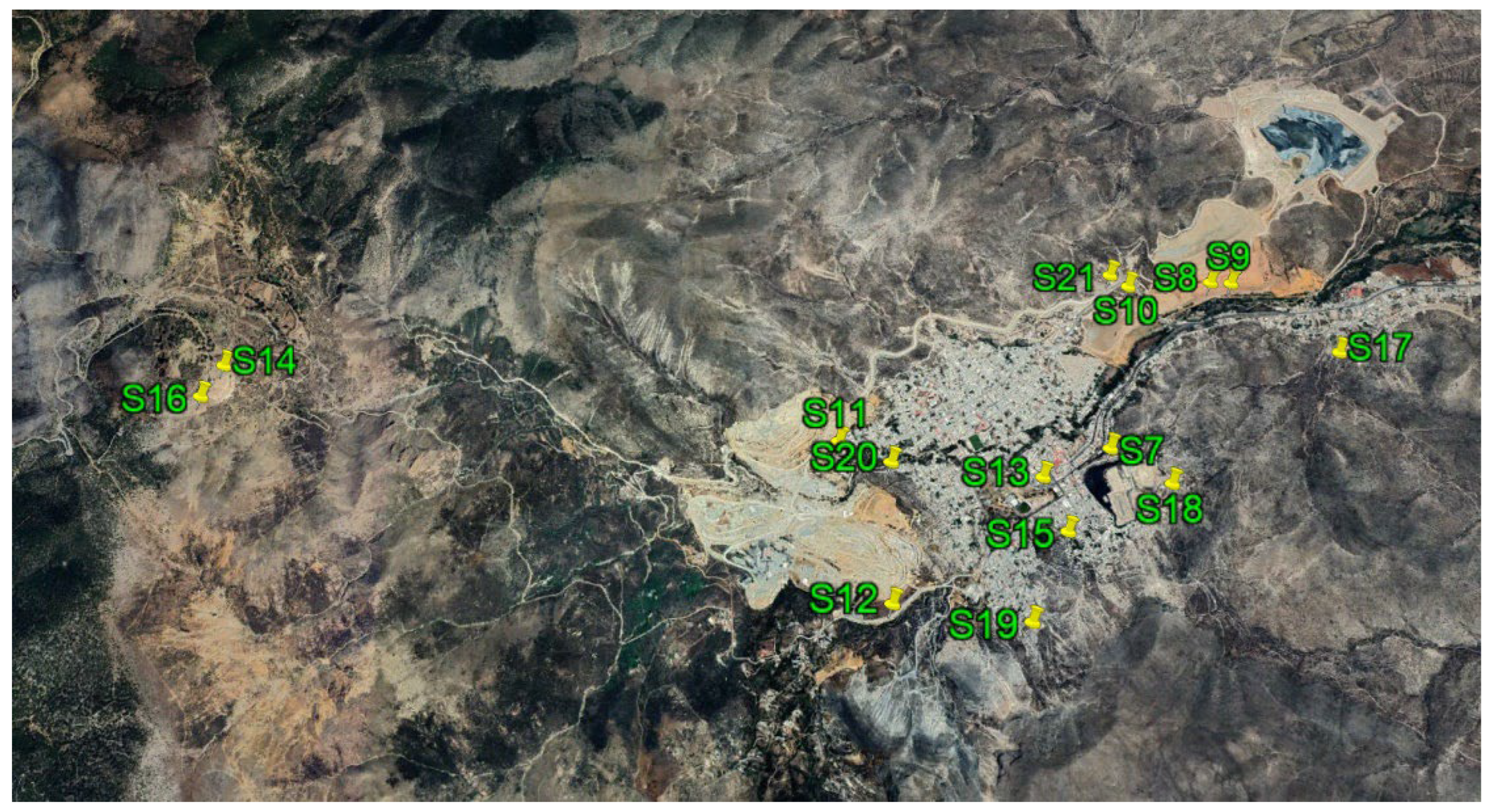

2.1. Study Area

| Sample | Type of sample | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | Mine tailings | 22º47'15"N 102°36.36"W |

| S2 | Mine tailings | 24°36'48"N 101°24'51"W | |

| S3 | Undisturbed soil | 22°46'52"N 102°32'42"W | |

| S4 | Undisturbed soil | 22°46'36"N 102°33'52"W | |

| S5 | Mine dump | 22°47'25"N 102°34'46"W | |

| S6 | Undisturbed soil | 22°79'31"N 102°55'53"W | |

| Zone B | S7 | Mine tailings | 24°37'12"N 101°24'40"W |

| S8 | Mine tailings | 24°37'16"N 101°24'30"W | |

| S9 | Mine tailings | 24°37'16"N 101°24'27"W | |

| S10 | Mine tailings | 24°37'15"N 101°24'45"W | |

| S11 | Undisturbed soil | 24°36'20"N 101°25'60"W | |

| S12 | Mine tailings | 24°36'49"N 101°25'37"W | |

| S13 | Mine tailings | 24°36'23"N 101°25'28"W | |

| S14 | Mine tailings | 24°36'43"N 101°25'20"W | |

| S15 | Mine tailings | 24°36'57"N 101°27'26"W | |

| S16 | Undisturbed soil | 24°37'17"N 101°24'48"W | |

| S17 | Undisturbed soil | 24°36'42"N 101°24'41"W | |

| S18 | Undisturbed soil | 24°36'46"N 101°25'28"W | |

| S19 | Undisturbed soil | 24°37'30"N 101°24'90"W | |

| S20 | Undisturbed soil | 22°46'54"N 102°36'50"W | |

| S21 | Mine tailings | 24°37'20"N 101°27'23"W |

2.2. Radioactivity Analysis.

| Group | Radionuclide Long half-life | Gamma emitting nuclide | Gamma-ray energy (keV) | Gamma-emitting nuclides included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 238U |

234Th 234mPa |

63.30 ± 0.02 1001.30 ± 0.02 |

238U, 234Th 234Pa, 234mPa |

| B | 230Th | 230Th | 67.67 ± 0.01 |

230Th |

| C |

226Ra 222Rn |

226Ra 214Pb 214Bi |

186.21 ± 0.01 351.932 ± 0.002 609.312 ± 0.007 1120.29 ± 0.01 1764.49 ± 0.01 |

226Ra, 222Rn 214Pb, 214Bi 210Tl |

| D | 210Pb | 210Pb | 46.539 ± 0.001 |

210Pb |

| E | 235U | 235U | 143.767 ± 0.003 163.356 ± 0.003 205.316 ± 0.004 |

235U series |

| F |

232Th 228Ra |

(-) 228Ac |

(-) 911.196 ± 0.002 |

232Th, 228Ra 228Ac |

| G |

228Th 220Rn |

224Ra 212Pb 208Tl |

(-) 238.632 ± 0.002 583.187 ± 0.002 |

228Th, 224Ra 220Rn, 212Pb 212Bi, 208Tl |

2.3. Chemical and Structural Characterization

2.4. pH in water and CaCl2

2.5. Impact Parameters for Heavy Metals

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Radioactivity Levels and Their Impact

| Sample | Group A 238U |

Group C 226Ra |

Group F 232Th |

Group G 228Th |

40K | 137Cs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 62.81 ± 1.44 | 165.48 ± 0.98 | 24.35 ± 0.55 | 23.94 ± 0.61 | 967.58 ± 13.11 | 0.68 ± 0.02 |

| S2 | 52.26 ± 1.48 | 259.98 ± 1.64 | 40.77 ± 0.92 | 48.22 ± 1.24 | 1356.02 ± 18.37 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | |

| S3 | 51.22 ± 1.18 | 171.46 ± 1.05 | 25.92 ± 0.58 | 27.49 ± 0.7 | 1123.12 ± 15.21 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | |

| S4 | 80.71 ± 1.49 | 303.45 ± 1.9 | 58.93 ± 1.32 | 69.26 ± 1.79 | 1348.26 ± 18.26 | 2.87 ± 0.08 | |

| S5 | 115.92 ± 2.33 | 124.26 ± 1.09 | 15.18 ± 0.49 | 14.92 ± 0.54 | 845.92 ± 16.56 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | |

| S6 | 86.79 ± 1.92 | 177.86 ± 1.1 | 24.92 ± 0.56 | 29.14 ± 0.75 | 812.99 ± 11.01 | 1.89 ± 0.05 | |

| Range | 51.22-115.92 | 124.26-303.45 | 15.18-58.93 | 14.92-69.26 | 812.99-1356.02 | 0.07-2.87 | |

| Mean | 74.95 | 200.42 | 31.68 | 35.5 | 1075.65 | 1.05 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 103.11 ± 2.10 | 259.98 ± 2.31 | 12.44 ± 0.28 | 9.64 ± 0.24 | 401.35 ± 5.44 | 0.58 ± 0.02 |

| S8 | 97.91 ± 1.98 | 259.98 ± 2.13 | 27.41 ± 0.62 | 26.69 ± 0.68 | 949.28 ± 12.86 | 2.10 ± 0.06 | |

| S9 | 59.41 ± 1.80 | 105.76 ± 0.62 | 9.66 ± 0.22 | 6.70 ± 0.16 | 324.17 ± 4.13 | 2.00 ± 0.06 | |

| S10 | 60.13 ± 1.54 | 242.20 ± 1.50 | 18.22 ± 0.41 | 13.49 ± 0.33 | 597.77 ± 8.10 | 1.07 ± 0.03 | |

| S11 | 87.11 ± 1.81 | 315.91 ± 2.05 | 37.02 ± 0.86 | 42.80 ± 1.14 | 1121.25 ± 15.69 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | |

| S12 | 120.25 ± 3.72 | 276.49 ± 1.72 | 23.97 ± 0.54 | 22.39 ± 0.57 | 732.21 ± 9.92 | 2.09 ± 0.06 | |

| S13 | 160.18 ± 2.99 | 292.74 ± 1.82 | 24.95 ± 0.56 | 22.94 ± 0.58 | 851.84 ± 11.54 | 0.57 ± 0.02 | |

| S14 | 152.28 ± 1.98 | 596.26 ± 3.86 | 15.72 ± 0.35 | 14.23 ± 0.36 | 354.92 ± 4.81 | 1.10 ± 0.03 | |

| S15 | 106.03 ± 2.09 | 308.47 ± 1.89 | 26.24 ± 0.57 | 27.11 ± 0.67 | 824.09 ± 10.73 | 2.12 ± 0.06 | |

| S16 | 112.86 ± 2.44 | 324.65 ± 1.63 | 30.14 ± 0.54 | 32.92 ± 0.67 | 1237.67 ± 13.28 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | |

| S17 | 95.43 ± 2.05 | 281.92 ± 2.01 | 23.19 ± 0.58 | 22.84 ± 0.65 | 658.66 ± 10.01 | 6.35 ± 0.21 | |

| S18 | 151.63 ± 2.52 | 503.49 ± 2.61 | 48.32 ± 0.88 | 57.07 ± 1.19 | 929.78 ± 10.20 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | |

| S19 | 99.94 ± 1.64 | 251.54 ± 1.07 | 43.49 ± 0.67 | 50.98 ± 0.90 | 1309.66 ± 12.11 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | |

| S20 | 120.99 ± 1.54 | 190.07 ± 0.79 | 31.63 ± 0.48 | 32.23 ± 0.56 | 1086.02 ± 10.04 | 2.10 ± 0.04 | |

| S21 | 82.55 ± 1.18 | 390.56 ± 2.52 | 44.97 ± 1.01 | 53.31 ± 1.37 | 1347.95 ± 18.26 | 0.59 ± 0.02 | |

| Range | 59.41-160.18 | 105.76-596.26 | 9.66-48.32 | 6.70-57.07 | 324.17-1347.95 | 0.14-6.35 | |

| Mean | 107.32 | 306.67 | 27.82 | 29.02 | 883.69 | 1.48 | |

|

World average |

Range | 16-110 | 17-60 | 11-64 | 140-850 | ||

| Mean | 35 | 35 | 30 | 400 |

| 238U (Bq kg-1) | 226Ra (Bq kg-1) | 232Th (Bq kg-1) | 40K (Bq kg-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work zone A | 75 | 200 | 35 | 1076 |

| This work zone B | 107 | 307 | 28 | 884 |

| Algeria | 30 | 50 | 25 | 370 |

| Egypt | 37 | 17 | 18 | 320 |

| Costa Rica | 46 | 46 | 11 | 140 |

| United states | 35 | 40 | 35 | 370 |

| China | 33 | 32 | 41 | 440 |

| Hong Kong | 84 | 59 | 95 | 530 |

| India | 29 | 29 | 64 | 400 |

| Japan | 29 | 33 | 28 | 310 |

| Kazakstan | 37 | 35 | 60 | 300 |

| Malaysia | 66 | 67 | 82 | 310 |

| Thailand | 114 | 48 | 51 | 230 |

| Armenia | 46 | 51 | 30 | 360 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 23 | 20 | 20 | 270 |

| Norway | 50 | 50 | 45 | 850 |

| Ireland | 37 | 60 | 26 | 350 |

| Switzerland | 40 | 40 | 25 | 370 |

| Bulgaria | 40 | 45 | 30 | 400 |

| Hungary | 29 | 33 | 28 | 370 |

| Poland | 26 | 26 | 21 | 410 |

| Romania | 32 | 32 | 38 | 490 |

| Russian Federation | 19 | 27 | 30 | 520 |

| Slovakia | 32 | 32 | 38 | 520 |

| Croatia | 110 | 54 | 45 | 490 |

| Greece | 25 | 25 | 21 | 360 |

| Portugal | 49 | 44 | 51 | 840 |

| World average | 40 | 37 | 36 | 369 |

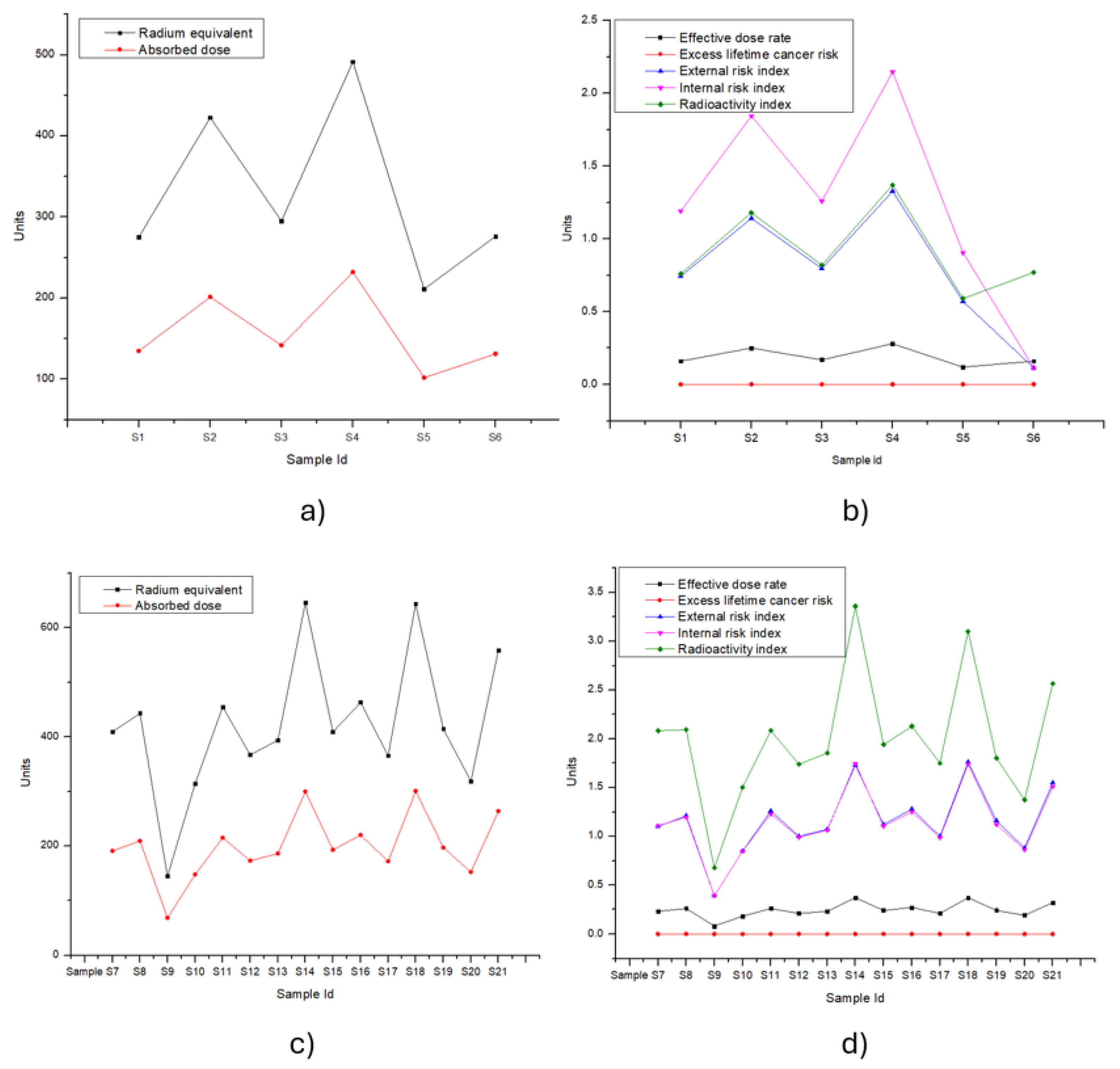

3.2. Contamination Assessment by Radionuclides

| Sample |

Raeq Bq kg-1 |

) nGy h-1 |

E mSv y-1 |

ELCR mSv |

Hex mSv y-1 |

Hin mSv y-1 |

Ri nGy h-1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 275.23 | 134.69 | 0.16 | 0.00065 | 0.744 | 1.191 | 0.76 |

| S2 | 422.70 | 201.28 | 0.25 | 0.00100 | 1.142 | 1.845 | 1.18 | |

| S3 | 295.01 | 141.70 | 0.17 | 0.00070 | 0.797 | 1.260 | 0.82 | |

| S4 | 491.53 | 232.01 | 0.28 | 0.00115 | 1.328 | 2.148 | 1.37 | |

| S5 | 211.11 | 101.85 | 0.12 | 0.00050 | 0.570 | 0.906 | 0.59 | |

| S6 | 276.10 | 131.13 | 0.16 | 0.00065 | 0.113 | 0.113 | 0.77 | |

| Range | 211.11-491.53 | 101.85-232.01 | 0.12-0.28 | 0.0005-0.0012 | 0.11-1.33 | 0.11-2.15 | 0.59-1.37 | |

| Mean | 328.61 | 157.11 | 0.19 | 0.0008 | 0.78 | 1.24 | 0.92 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 409.54 | 190.96 | 0.23 | 0.00095 | 1.107 | 2.082 | 1.10 |

| S8 | 443.37 | 209.10 | 0.26 | 0.00104 | 1.198 | 2.093 | 1.21 | |

| S9 | 144.54 | 68.22 | 0.08 | 0.00034 | 0.391 | 0.676 | 0.39 | |

| S10 | 314.28 | 147.83 | 0.18 | 0.00073 | 0.849 | 1.504 | 0.85 | |

| S11 | 455.18 | 215.07 | 0.26 | 0.00107 | 1.230 | 2.084 | 1.26 | |

| S12 | 367.14 | 172.75 | 0.21 | 0.00086 | 0.992 | 1.739 | 1.00 | |

| S13 | 393.86 | 185.77 | 0.23 | 0.00092 | 1.064 | 1.855 | 1.07 | |

| S14 | 646.07 | 299.77 | 0.37 | 0.00149 | 1.746 | 3.358 | 1.73 | |

| S15 | 409.45 | 192.73 | 0.24 | 0.00096 | 1.106 | 1.940 | 1.12 | |

| S16 | 463.06 | 219.81 | 0.27 | 0.00109 | 1.251 | 2.129 | 1.28 | |

| S17 | 365.80 | 171.72 | 0.21 | 0.00085 | 0.988 | 1.750 | 1.00 | |

| S18 | 644.18 | 300.57 | 0.37 | 0.00147 | 1.741 | 3.101 | 1.76 | |

| S19 | 414.57 | 197.09 | 0.24 | 0.00098 | 1.120 | 1.800 | 1.16 | |

| S20 | 318.92 | 152.20 | 0.19 | 0.00076 | 0.862 | 1.375 | 0.88 | |

| S21 | 558.67 | 263.81 | 0.32 | 0.00131 | 1.509 | 2.565 | 1.55 | |

| Range | 144.54-646.07 | 68.22-300.57 | 0.08-0.37 | 0.0003-0.0015 | 0.39-1.75 | 0.68-3.36 | 0.39-1.76 | |

| Mean | 423.24 | 199.16 | 0.24 | 0.001 | 1.14 | 2.00 | 1.16 |

3.3. Chemical and Structural Characterization

| Sample Id | pH Water | pH CaCl2 | Si | S | Fe | Ca | Al | Mg | Na | K | Ti | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 23 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.73 | - | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| S2 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 19 | 0.32 | 8.1 | 0.9 | 8.6 | 1.1 | 0.39 | 2.2 | 0.71 | 0.07 | |

| S3 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 21 | 0.15 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 2.2 | 0.34 | 0.29 | |

| S4 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 22 | 0.057 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 9.1 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 2.4 | 0.46 | 0.11 | |

| S5 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 25 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 8.0 | 0.67 | 0.25 | 1.5 | 0.14 | 0.27 | |

| S6 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 11 | 2.8 | 17 | 11 | 2.9 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.12 | - | |

| Mean | 7 | 6.3 | 20.16 | 1.48 | 6.46 | 3.8 | 6.15 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 1.57 | 0.3 | 0.15 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 19 | 15 | 1.0 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| S8 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 3.1 | 15 | 20 | 0.7 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| S9 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 8.7 | 3.1 | 15 | 19 | 0.7 | 0.29 | - | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |

| S10 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 21 | 14 | 1.1 | 0.24 | - | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| S11 | 8.3 | 7.6 | 16 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 5.4 | 0.7 | 0.68 | 1.8 | 0.27 | 0.18 | |

| S12 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 16 | 1.7 | 12 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.22 | |

| S13 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 11 | 1.9 | 14 | 18 | 1.4 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.05 | - | |

| S14 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 9.3 | 0.46 | 7.8 | 27 | 0.4 | 0.55 | - | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| S15 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 10 | 0.46 | 8.6 | 24 | 0.6 | 0.47 | - | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| S16 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 10 | 0.083 | 3.4 | 25 | 3.5 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 1.6 | 0.26 | - | |

| S17 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 3.2 | 0.036 | 1.0 | 40 | 1.1 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.04 | |

| S18 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 4.4 | 0.11 | 3.0 | 35 | 1.3 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.39 | - | 0.08 | |

| S19 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 8.8 | 0.11 | 3.3 | 27 | 2.8 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 0.09 | |

| S20 | 8.1 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 0.12 | 3.1 | 26 | 2.6 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 1.0 | 0.21 | 0.10 | |

| S21 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 22 | 0.25 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 9.2 | 1.9 | 0.22 | 2.8 | 0.54 | 0.08 | |

| Mean | 7.84 | 7.46 | 10.11 | 1.91 | 9.28 | 20.19 | 2.51 | 0.54 | 0.2 | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.07 |

| Sample Id | As | Cd | Cr | Ni | Pb | Se | Tl | U | Th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 180.08 ± 0.55 | 5.20 ± 0.65 | 24.44 ± 0.21 | 18.22 ± 0.14 | 533.74 ± 3.00 | 2.65 ± 0.06 | 1.20 ± 0.15 | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.80 ± 0.12 |

| S2 | 169.78 ± 0.43 | 0.54 ± 0.39 | 111.61 ± 0.28 | 41.23 ± 0.08 | 1465.76 ± 3.20 | 1.98 ± 0.03 | 3.20 ± 0.21 | 1.10 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | |

| S3 | 58.39 ± 0.16 | 0.15 ± 0.22 | 43.51 ± 0.07 | 14.13 ± 0.03 | 162.92 ± 0.32 | 2.46 ± 0.02 | 1.14 ± 0.12 | 1.39 ± 0.18 | 1.85 ± 0.20 | |

| S4 | 60.31 ± 0.28 | 0.08 ± 0.11 | 60.31 ± 0.28 | 24.57 ± 0.05 | 124.08 ± 0.36 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | |

| S5 | 82.27 ± 0.29 | 0.17 ± 0.24 | 28.61 ± 0.20 | 11.71 ± 0.10 | 101.26 ± 0.74 | 1.21 ± 0.04 | 1.40 ± 0.13 | 1.92 ± 0.25 | 1.10 ± 0.14 | |

| S6 | 23.01 ± 0.11 | 2.58 ± 0.14 | 149.41 ± 1.3 | 58.53 ± 0.45 | 0.23 ± 0.15 | 1.41 ± 0.02 | 1.50 ± 0.07 | 1.46 ± 0.07 | 1.21 ± 0.007 | |

| Range | 23.01-180.08 | 0.08-5.20 | 24.44-149.41 | 11.71-58.53 | 0.23-1465 | 0.55-2.65 | 0.85-3.20 | 0.72-1.92 | 0.17-1.85 | |

| Mean | 90.22 | 1.45 | 69.65 | 28.06 | 398 | 1.71 | 1.55 | 1.23 | 0.89 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 517.05 ± 1.8 | 1.39 ± 1.8 | 14.12 ± 0.04 | 21.51 ± 0.03 | 768.40 ± 2.60 | 14.58 ± 0.15 | 0.98 ± 0.12 | 6.68 ± 1.05 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| S8 | 200.37 ± 1.1 | 0.29 ± 0.17 | 7.89 ± 0.05 | 20.97 ± 0.11 | 87.54 ± 0.71 | 7.65 ± 0.15 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 5.37 ± 0.71 | 0.03 ± 0.005 | |

| S9 | 476.47 ± 2.0 | 0.35 ± 0.13 | 7.28 ± 0.03 | 12.45 ± 0.11 | 103.14 ± 0.24 | 5.43 ± 0.11 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 4.31 ± 0.19 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | |

| S10 | 457.19 ± 2.0 | 0.30 ± 0.13 | 5.98 ± 0.03 | 13.27 ± 0.05 | 98.42 ± 0.39 | 5.64 ± 0.08 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 4.55 ± 0.31 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | |

| S11 | 219.73 ± 0.3 | 0.29 ± 0.16 | 8.13 ± 0.05 | 27.27 ± 0.10 | 123.90 ± 0.51 | 9.91 ± 0.19 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 5.23 ± 0.45 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | |

| S12 | 183.21 ± 0.6 | 0.18 ± 0.24 | 14.50 ± 0.06 | 8.88 ± 0.04 | 59.44 ± 0.19 | 5.10 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.17 | 3.62 ± 0.60 | 3.34 ± 0.67 | |

| S13 | 135.41 ± 0.7 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 13.12 ± 0.06 | 9.91 ± 0.06 | 22.52 ± 0.15 | 3.36 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 2.95 ± 0.21 | 3.50 ± 0.29 | |

| S14 | 199.33 ± 1.4 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 6.17 ± 0.05 | 10.98 ± 0.07 | 50.93 ± 0.46 | 4.05 ± 0.11 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 3.71 ± 0.30 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | |

| S15 | 44.25 ± 0.1 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 1.78 ± 0.01 | 2.11 ± 0.01 | 224.19 ± 1.01 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 2.43 ± 0.08 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | |

| S16 | 340.74 ± 3.7 | 0.63 ± 0.24 | 2.77 ± 0.03 | 1.93 ± 0.02 | 345.83 ± 4.08 | 7.22 ± 0.06 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 3.03 ± 0.15 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | |

| S17 | 217.77 ± 1.6 | 6.12 ± 0.42 | 21.92 ± 0.18 | 16.37 ± 0.11 | 4.35 ± 3.58 | 3.32 ± 0.04 | 4.85 ± 0.33 | 3.04 ± 0.23 | 1.050 ± 0.008 | |

| S18 | 51.98 ± 0.28 | 2.37 ± 0.08 | 7.62 ± 0.03 | 5.28 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.60 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 0.170 ± 0.001 | |

| S19 | 182.49 ± 1.3 | 5.57 ± 0.41 | 13.09 ± 0.13 | 13.78 ± 0.14 | 2.58 ± 2.64 | 2.70 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 2.26 ± 0.16 | 0.390 ± 0.003 | |

| S20 | 141.25 ± 0.5 | 4.09 ± 0.29 | 13.95 ± 0.07 | 12.36 ± 0.06 | 1.88 ± 0.84 | 2.64 ± 0.04 | 1.26 ± 0.07 | 1.85 ± 0.13 | 0.970 ± 0.004 | |

| S21 | 153.87 ± 1.0 | 5.36 ± 0.29 | 13.94 ± 0.08 | 13.15 ± 0.07 | 3.23 ± 2.32 | 2.70 ± 0.03 | 3.57 ± 0.15 | 1.85 ± 0.11 | 0.620 ± 0.004 | |

| Range | 44.3-517.7 | 0.1-6.1 | 1.7-21.9 | 1.9-27.3 | 0.8-768 | 1.1-14.6 | 0.1-4.8 | 1.1-6.7 | 0.003-3.50 | |

| Mean | 234.7 | 1.8 | 10.2 | 12.7 | 126 | 5.1 | 0.96 | 3.5 | 0.70 | |

| Agricultural/residential/commercial use | Mean | 22 | 37 | 280 | 1600 | 400 | 390 | 5.2 | ||

| Industrial use | Mean | 260 | 450 | 510 | 20000 | 800 | 5100 | 67 |

| Sample Id | Oxides | Carbonates | Silicates | Hydroxides | Other compounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | LiAlSiO4 | CaF2 | |

| S2 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | KAlSi3O8Na(AlSi3O8)Na0.3(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2.H2OCaAl2Si2O84H2O | ||||

| S3 | SiO2 | CaCO3 | K(Al,Fe)Si2O8Ca0.88S0.12Al1.77Si2.23O8KAlSi3O8Na0.3(Al,Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2.H2O | |||

| S4 | SiO2 | (Na0.98Ca0.02)(Al1.02Si2.98O8)K(Al4Si2O9(OH)3)K4Al4Si12O32 | ||||

| S5 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | KAlSi3O8KAl2Si3AlO10(OH)2 | |||

| S6 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3KAlSi3O8Ca0.88S0.12Al1.77Si2.23O8 | CaSO4 | ||

| Zone B | S7 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3K(Al Fe)Si2O8 | CaSO4 | |

| S8 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3 | CaSO4 | ||

| S9 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3 | CaSO4 | ||

| S10 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3 | CaSO4 | ||

| S11 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | K(Al Fe)Si2O8Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3(Na,Ca)Al(Si,Al)3O8 | CaSO4 | ||

| S12 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | K(Al Fe)Si2O8Ca3(Al1. 3325Fe0. 6675)Si3O12 | CaSO4 | ||

| S13 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3Ca0.88S0.12Al1.77Si2.23O8 | CaSO4 | ||

| S14 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3 | |||

| S15 | SiO2, Fe2O3 | CaCO3 | Ca3Fe1.88(SiO4)3 | |||

| S16 | SiO2 | CaCO3 | K(Al Fe)Si2O8KAl2Si3AlO10(OH)2 (Mg Al)5(Si Al)8O20(OH)28H2OCa0.88S0.12Al1.77Si2.23O8K(AlSi3O8)Ca3Al2(SiO4)2(OH)4 | |||

| S17 | SiO2 | CaCO3 | Ca3Al2SiO6CaMg3(SiO4)3 | |||

| S18 | SiO2 | CaCO3 | Ca3Al2(SiO4)2(OH)4CaAl2Si2O8K(AlSi3O8) | Fe(OH)3 | ||

| S19 | SiO2 | CaCO3 | Ca2.964(Al1.026Fe0.974)Si2.979O11.844(OH)0.156KAl4(Si Al)8O10(OH)4H2OCa0.88S0.12Al1.77 Si2.23O8 | |||

| S20 | SiO2 | CaCO3 | Ca0.88S0.12Al1.77Si2.23O8KAl4(Si Al)8O10(OH)4H2OCa2.964(Al1.026Fe0.974)Si2.979O11.844(OH)0.156Ca2Al2SiO6(OH)2 | |||

| S21 | SiO2 | KAl2Si3AlO10(OH)2Al2Si2O5(OH)4CaAl2Si7O18.7.5H2O(Mg Fe Al)6(Si Al)4O10(OH)8KAlSi3O8 |

3.4. Contamination Assessment by Heavy Metal

| Sample Id | As | Cd | Cr | Ni | Pb | Se | Tl | U | Th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 12.71 | 5.51 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 8.07 | 4.68 | 1.41 | 0.28 | 0.08 |

| S2 | 5.47 | 0.26 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 10.13 | 1.60 | 1.72 | 0.20 | 0.01 | |

| S3 | 4.92 | 0.19 | 0.61 | 0.26 | 2.94 | 5.18 | 1.6 | 0.65 | 0.22 | |

| S4 | 1.58 | 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.31 | 1.51 | 0.78 | 0.8 | 0.25 | 0.01 | |

| S5 | 9.34 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 2.46 | 3.42 | 2.66 | 1.21 | 0.18 | |

| S6 | 1.18 | 1.98 | 1.28 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 1.81 | 1.28 | 0.41 | 0.09 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 7.94 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 2.53 | 5.60 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.01 |

| S8 | 2.75 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 2.63 | 0.07 | 0.41 | <0.01 | |

| S9 | 8.3 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 2.37 | 0.07 | 0.42 | <0.01 | |

| S10 | 7.96 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 2.45 | 0.06 | 0.44 | <0.01 | |

| S11 | 2.73 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 3.08 | 0.08 | 0.36 | <0.01 | |

| S12 | 5.98 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 4.16 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.16 | |

| S13 | 2.95 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 1.83 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.11 | |

| S14 | 3.72 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 1.89 | 0.08 | 0.38 | <0.01 | |

| S15 | 1.48 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.61 | 0.94 | 0.08 | 0.45 | <0.01 | |

| S16 | 10.35 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.25 | 5.48 | 0.09 | 0.51 | <0.01 | |

| S17 | 16.73 | 7.05 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.07 | 6.38 | 6.21 | 1.30 | 0.12 | |

| S18 | 13.58 | 9.29 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 9.97 | 1.08 | 1.53 | 0.06 | |

| S19 | 15.89 | 7.27 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 5.88 | 0.85 | 1.09 | 0.05 | |

| S20 | 11.18 | 4.86 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 5.22 | 1.66 | 0.81 | 0.11 | |

| S21 | 12.96 | 6.78 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 5.68 | 5.01 | 0.87 | 0.08 |

| Sample Id | As | Cd | Cr | Ni | Pb | Se | Tl | U | Th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 3.00 | 1.79 | -2.47 | -2.49 | 2.35 | 1.56 | -0.17 | -2.49 | -4.30 |

| S2 | 2.92 | -1.48 | -0.27 | -1.31 | 3.80 | 1.14 | 1.24 | -1.89 | -6.08 | |

| S3 | 1.38 | -3.32 | -1.63 | -2.85 | 0.63 | 1.45 | -0.24 | -1.55 | -3.09 | |

| S4 | 0.31 | -4.17 | -1.16 | -2.05 | 0.24 | -0.72 | -0.67 | -2.34 | -6.55 | |

| S5 | 1.87 | -3.13 | -2.24 | -3.12 | -0.05 | 0.42 | 0.06 | -1.08 | -3.84 | |

| S6 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.15 | -0.80 | -8.81 | 0.65 | 0.15 | -1.47 | -3.70 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 4.52 | -0.11 | -3.26 | -2.25 | 2.87 | 4.02 | -0.46 | 0.72 | -5.84 |

| S8 | 3.15 | -2.35 | -4.10 | -2.28 | -0.26 | 3.09 | -2.20 | 0.41 | -9.01 | |

| S9 | 4.40 | -2.10 | -4.21 | -3.03 | -0.03 | 2.59 | -2.55 | 0.09 | -10.61 | |

| S10 | 4.34 | -2.34 | -4.50 | -2.94 | -0.09 | 2.65 | -2.78 | 0.17 | -12.42 | |

| S11 | 3.29 | -2.38 | -4.05 | -1.90 | 0.24 | 3.46 | -1.89 | 0.37 | -9.34 | |

| S12 | 3.03 | -3.04 | -3.22 | -3.52 | -0.82 | 2.50 | -0.51 | -0.16 | -2.24 | |

| S13 | 2.59 | -4.09 | -3.36 | -3.36 | -2.22 | 1.90 | -1.95 | -0.46 | -2.17 | |

| S14 | 3.15 | -3.99 | -4.45 | -3.22 | -1.04 | 2.17 | -2.38 | -0.12 | -10.15 | |

| S15 | 0.98 | -1.93 | -6.24 | -5.60 | 1.09 | 0.31 | -3.31 | -0.74 | -13.94 | |

| S16 | 3.92 | -1.26 | -5.60 | -5.72 | 1.72 | 3.00 | -2.98 | -0.42 | -12.59 | |

| S17 | 3.27 | 2.03 | -2.62 | -2.64 | -4.59 | 1.88 | 1.84 | -0.42 | -3.91 | |

| S18 | 1.21 | 0.66 | -4.15 | -4.27 | -6.99 | 0.76 | -2.44 | -1.95 | -6.51 | |

| S19 | 3.02 | 1.89 | -3.37 | -2.89 | -5.34 | 1.59 | -1.20 | -0.84 | -5.34 | |

| S20 | 2.65 | 1.45 | -3.27 | -3.05 | -5.80 | 1.55 | -0.10 | -1.13 | -4.02 | |

| S21 | 2.77 | 1.84 | -3.27 | -2.96 | -5.02 | 1.58 | 1.40 | -1.13 | -4.66 |

| Sample Id | As | Cd | Cr | Ni | Pb | Se | Tl | U | Th | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone A | S1 | 12.01 | 5.2 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 7.62 | 4.42 | 1.33 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| S2 | 11.32 | 0.54 | 1.24 | 0.61 | 20.94 | 3.30 | 3.55 | 0.41 | 0.02 | |

| S3 | 3.89 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 2.33 | 4.10 | 1.27 | 0.51 | 0.18 | |

| S4 | 1.85 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 1.77 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.30 | 0.02 | |

| S5 | 5.48 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 1.45 | 2.01 | 1.56 | 0.71 | 0.10 | |

| S6 | 1.53 | 2.58 | 1.66 | 0.86 | <0 | 2.35 | 1.67 | 0.54 | 0.12 | |

| Zone B | S7 | 34.47 | 1.39 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 10.98 | 24.30 | 1.09 | 2.48 | 0.03 |

| S8 | 13.36 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 1.25 | 12.74 | 0.33 | 1.99 | <0 | |

| S9 | 31.76 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 1.47 | 9.06 | 0.26 | 1.60 | <0 | |

| S10 | 30.48 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 1.41 | 9.40 | 0.22 | 1.68 | <0 | |

| S11 | 14.65 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 1.77 | 16.52 | 0.40 | 1.94 | <0 | |

| S12 | 12.21 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.85 | 8.50 | 1.06 | 1.34 | 0.32 | |

| S13 | 9.03 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 5.60 | 0.39 | 1.09 | 0.33 | |

| S14 | 13.29 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.73 | 6.75 | 0.29 | 1.38 | <0 | |

| S15 | 2.95 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 3.20 | 1.87 | 0.15 | 0.90 | <0 | |

| S16 | 22.72 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 4.94 | 12.03 | 0.19 | 1.12 | <0 | |

| S17 | 14.52 | 6.12 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 5.54 | 5.39 | 1.12 | 0.10 | |

| S18 | 3.47 | 2.37 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 2.54 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.02 | |

| S19 | 12.17 | 5.57 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 4.51 | 0.65 | 0.84 | 0.04 | |

| S20 | 9.42 | 4.09 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 4.40 | 1.40 | 0.69 | 0.09 | |

| S21 | 10.26 | 5.36 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 4.49 | 3.97 | 0.68 | 0.06 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Compliance with ethical statement

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Milenkovic, B.; Stajic, J.M.; Gulan, L.; Zeremski, T.; Nikezic, D. Radioactivity levels and heavy metals in the urban soil of Central Serbia. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2015, 22, 16732–16741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Extent of Environmental Contamination by Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM) and Technological Options for Mitigation; Viena, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mitwally, E.M.A.; Yu, B.S. Assessment of radiological hazard indices caused by 238U, 232Th, 226Ra and 40K radionuclides of heavy minerals on Taiwanese beach sands, stream sediments, and surrounding rocks: implications for radiometric fingerprinting of the environmental impact. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2023, 332, 4847–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSCEAR. Sources and effects of ionizing radiation, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation; New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Izgagin, V.S.; Zhukovsky, M.V.; Onishchenko, A.D.; Yarmoshenko, I.V.; Pyshkina, M.D. Gamma-radiation exposure by natural radionuclides in residential building materials on example of nine Russian cities. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 2023. [CrossRef]

- Karunakara, N.; Rao, C.; Ujwal, P.; Yashodhara, I.; Kumara, S.; Ravi, P.M. Soil to rice transfer factors for 226Ra, 228Ra, 210Pb, 40K and 137Cs: A study on rice grown in India. J Environ Radioact 2013, 118, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICRP, Protection Against Radon-222 at Home and at Work, 1994. https://www.icrp.org.

- Song, P.; Xu, D.; Yue, J.; Ma, Y.; Dong, S.; Feng, J. Recent advances in soil remediation technology for heavy metal contaminated sites: A critical review. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 838, 156417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, M.D.; Rucandio, M.I. Sequential extractions for determination of cadmium distribution in coal fly ash, soil and sediment samples. Anal Chim Acta 1999, 401, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarko, B.J.B.; Adomako, D.; Serfor-Armah, Y.; Dampare, S.B.; Adotey, D.; Akaho, E.H.K. Biomonitoring of atmospheric trace element deposition around an industrial town in Ghana. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2006, 75, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibikunle, S.B.; Arogunjo, A.M.; Ajayi, O.S. Characterization of radiation dose and soil-to-plant transfer factor of natural radionuclides in some cities from south-western Nigeria and its effect on man. Sci Afr 2019, 3, e00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, D.C. Trace Elements in Terrestrial Environments. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, Z. Soil heavy metal contamination and health risks associated with artisanal gold mining in Tongguan, Shaanxi, China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2017, 141, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonkwo, S.I.; Idakwo, S.O.; Ameh, E.G. Heavy metal contamination and ecological risk assessment of soils around the pegmatite mining sites at Olode area, Ibadan southwestern Nigeria. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 2021. [CrossRef]

- Olivarez, M.B.; Tovar, M.A.M.; Sánchez, J.V.; Betancourt, M.L.G.; Romero, F.M.; Arteaga, A.M.R.; Chávez, G.E.M.; Noreña, H.A.S.; Olivarez, M.B.; Tovar, M.A.M.; Sánchez, J.V.; Betancourt, M.L.G.; Romero, F.M.; Arteaga, A.M.R.; Chávez, G.E.M.; Noreña, H.A.S. Mobility of Heavy Metals in Aquatic Environments Impacted by Ancient Mining-Waste. Water Quality - Factors and Impacts. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Review of soil heavy metal pollution in China: Spatial distribution, primary sources, and remediation alternatives. Resour Conserv Recycl 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, S.A.; De La Torre, J.A.F.; Vega, M.M.; González, F.J.A.; Cabriales, J.J.P.; Soils, S.V.O.H.M.I. Sediments of “la Zacatecana” Lagoon, Mexico. Appl Environ Soil Sci 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Escareño-Juarez, E.; Jiménez-Barredo, F.; Gascó-Leonarte, C.; Barrado-Olmedo, A.I.; Vega, M. Baseline thorium concentration and isotope ratios in topsoil of Zacatecas State, Mexico. Chemosphere 2021, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaria del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, NOM-141-SEMARNAT-2003, Ciudad de Mexico, 2007.

- Murray, A.S.; Marten, R.; Johnston, A.; Martin, P. Analysis for naturally occuring radionuclides at environmental concentrations by gamma spectrometry. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry Articles 1987, 115, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Pacheco, E.; Suárez-Navarro, J.A.; Sánchez-González, S.M.; Suarez-Navarro, M.J.; Hernáiz, G.; García-Sánchez, A. A radiological index for evaluating the impact of an abandoned uranium mining area in Salamanca, Western Spain. Environmental Pollution 2020, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabiha-Javied; Tufail, M.; Asghar, M. Hazard of NORM from phosphorite of Pakistan. J Hazard Mater 2010, 176, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNSCEAR 2016 - Sources, Effects and Risks of Ionizing Radiation, New York, 2017.

- Eckerman, K.; Harrison, J.; Menzel, H.-G.; Clement, C.H. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 2007, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4972; Standard Test Methods for pH of Soils. West Conshohocken, PA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Ahmed, Z.; Seefat, S.M.; Alam, R.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Choudhury, T.R.; Begum, B.A.; Idris, A.M. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in sediment at the newly established tannery industrial Estate in Bangladesh: A case study. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 2022, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSCEAR. SOURCES AND EFFECTS OF IONIZING RADIATION; 2008; New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Agbalagba, E.O.; Avwiri, G.O.; Chad-Umoreh, Y.E. γ-Spectroscopy measurement of natural radioactivity and assessment of radiation hazard indices in soil samples from oil fields environment of Delta State, Nigeria. J Environ Radioact 2012, 109, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, U.; Younis, H.; Ullah, N.; Mehboob, K.; Ajaz, M.; Ali, M.; Hidayat, A.; Muhammad, W. Radionuclide concentrations in agricultural soil and lifetime cancer risk due to gamma radioactivity in district Swabi, KPK, Pakistan. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Secretaria del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA-2004, Ciudad de Mexico, 2007.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).