Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding and Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parida, A.K.; Das, A.B. Salt tolerance and salinity effects on plants: a review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2005, 60, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, T.J.; Coleman, T.D. Salinity tolerance in halophytes. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, T.J.; Coleman, T.D. Plant salt tolerance: adaptations in halophytes. Ann. Bot. 2015, 115, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.; Bhowmik, P.C.; Hossain, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Vara Prasad, M.N.; Ozturk, M.; Fujita, M. Potential use of halophytes to remediate saline soils. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, Volume 2014, Article ID 589341, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Shabala, S. Learning from halophytes: physiological basis and strategies to improve abiotic stress tolerance in crops. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcel, R.; Aroca, R.; Ruíz-Lozano, J.M. Salinity stress alleviation using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.; Bostan, N.; Nabgha-e-Amen; Maleeha, M.; Safdar, W. A critical review on halophytes: Salt tolerant plants. J. Medic. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 7108–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.M.; Buckley, D.P. Effects of salinity on gametophyte of Acrostichum aureum and A. danaefolium. Fern Gaz. 1986, 13, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, E.; Francisco, A.M.; Wingfield, R.; Casañas, O.L. Halofitismo en plantas de la costa Caribe de Venezuela: halófitas y halotolerantes. Acta Bot. Venez. 2008, 31, 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mehltreter, K. Phenology and habitat specificity of tropical ferns. In Biology and Evolution of Ferns and Lycophytes; Ranker, T.A., Haufler, C.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehltreter, K.; Palacios-Ríos, M. Phenological studies of Acrostichum danaeifolium (Pteridaceae, Pteridophyta) at a mangrove site on the Gulf of Mexico. J. Trop. Ecol. 2003, 19, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-A., J.; Orozco-O., N.; Rivera-Díaz, O. Los helechos y los licófitos del Caribe colombiano. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica XII. La Región Caribe de Colombia; Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, J.F.; Estrada, E.A.; Ortiz, L.F.; Urrego, L.E. Ecosystem-wide impacts of deforestation in mangroves. In The Urabá Gulf (Colombian Caribbean) Case Study. Internat. Scholar. Res. Network ISRN Ecol. Article ID 958709, 2012, Volume 2012, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Schüβler, A.; Schwarzott, D.; Walker, C. A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: phylogeny and evolution. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qiu, Y.-L. Phylogenetic distribution and evolution of mycorrhizas in land plants. Mycorrhiza 2006, 16, 299–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundrett, M.C.; Tedersoo, L. Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal symbiosis, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M.J. Molecular and cellular aspects of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant. Mol. Biol. 1999, 50, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappe, J.M. Phylogenetic and ecologic aspects of mycotrophy in the angiosperms from an evolutionary standpoint. In Ecophysiology of VA Mycorrhizal Plants; Safir, G.R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 1987; pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pressel, S.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Field, K.J.; Rimington, W.R.; Duckett, J.G. Pteridophyte fungal associations: current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Syst. Evol. 2016, 54, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, A.G. The occurrence of mycorrhizas in halophytes, hydrophytes and xerophytes, and of Endogone spores in adjacent soils. J. Gen. Microbial. 1974, 81, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, A.G. Effects of various soil environmental stresses on the occurrence, distribution and effectiveness of va mycorrhizae. Biotropica 1995, 8, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, J.; Arp, W.; van Diggelen, J.; van Esbroek, M.; Broekman, R.; Punte, H. Occurrence and ecological significance of vesicular arbuscular mycorrhiza in the salt marsh environment. Acta Bot. Neerl. 1986, 35, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Chaudhuri, S. Atypical root endophytic fungi of mangrove plant community of Sundarban and their possible significance as mycorrhiza. J. Mycopathol. Res. 1994, 32, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, B.; Kapoor, R.; Mukerji, K.G. Improved tolerance of Acacia nilotica to salt stress by arbuscular mycorrhiza, Glomus fasciculatum, may be partly related to elevated Kþ/Naþ ratios in root and shoot tissues. Microb. Ecol. 2007, 54, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D´Souza, J.; Rodrigues, B.F. Biodiversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) fungi in mangroves of Goa in West India. J. Forestry Res. 2013, 24, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, A.G.; Cofré, M.N.; García, I. Mycorrhizal simbiosis in salt-tolerance species and halophytes growing in salt affected soils of South America. In Mycorrhizal Fungi in South America; Pagano, M.C., Lugo, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lozano, J.M.; Azcón, R.; Gómez, M. Alleviation of salt stress by arbuscular-mycorrhizal Glomus species in Lactuca sativa plants. Physiol. Plant. 1996, 98, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Lozano, J.M.; Azcón, R. Symbiotic efficiency and infectivity of an autochthonous arbuscular mycorrhizal Glomus sp. from saline soils and G. deserticola under salinity. Mycorrhiza 2000, 10, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, M.; Rakshit, A. Arbuscular mycorrhiza: a versatile component for alleviation of salt stress. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2016, 15, 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Juniper, S.; Abbott, L. Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas and soil salinity. Mycorrhiza 1993, 4, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniper, S.; Abbott, L. Soil salinity delays germination and limits growth of hyphae from propagules of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 2006, 16, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Tam, N.F.-Y.; Xin, G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in two mangroves in South China. Plant Soil 2010, 331, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Xin, G.; Yang, Z.; Shi, S. Flooding greatly affects the diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi communities in the roots of wetland plants. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Kapoor, R.; Giri, B. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in alleviation of salt stress: a review. Ann. Bot. 2009, 104, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Lafet, A.A.H.; Miransari, M. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in alleviation of salt stress. In Use of Microbes for the Alleviation of Soil Stresses; Miransari, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Boughttas, S.; Hu, S.; Oh, S.H.; Sa, T. A meta-analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal effects on plants grown under salt stress. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, A.; Dilfuza, E.; Abd-Allah, E.F.; Hashem, A.; Kumar, A.; Ahmad, P. Salinity stress and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in plants. In Use of Microbes for the Alleviation of Soil Stresses; Miransari, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, E.R.; Johnson, C.R.; Koch, K.E. Accumulation of phosphorus, dry matter and betaine during NaCl stress of split-root citrus seedlings colonized with vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on zero, one or two halves. New Phytol. 1986, 104, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.; Zhang, F.S.; Li, X.L.; Tian, C.Y.; Tang, C.; Rengel, Z. Improved tolerance of maize plants to salt stress by arbuscular mycorrhiza is related to higher accumulation of soluble sugars in roots. Mycorrhiza 2002, 12, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Abdel-Fattah, G.M.; Eman, F.M.; Abb El-Aziz, M.H.; Shohr, A.E. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and spermine alleviate the adverse effects of salinity stress on electrolyte leankage and productivity of wheat plants. Phyton 2011, 51, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Fattah, G.M.; Abdul-Wasea, A.A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal application to improve growth and tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants grown in saline soil. Acta Physiol. Plant 2012, 34, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-S.; Zou, Y.-N.; He, X.-H. Contributions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to growth, photosynthesis, root morphology and ionic balance of citrus seedlings under salt stress. Acta Physiol. Plant 2010, 32, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Sarda Devi, T.; Gupta, S.; Kapoor, R. Mitigation of salinity stress in plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: current understanding and new challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, B.; Aroca, R.; Maathuis, F.J.M.; Barea, J.M.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi native from a Mediterranean saline area enhance maize tolerance to salinity through improved ion homeostasis. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

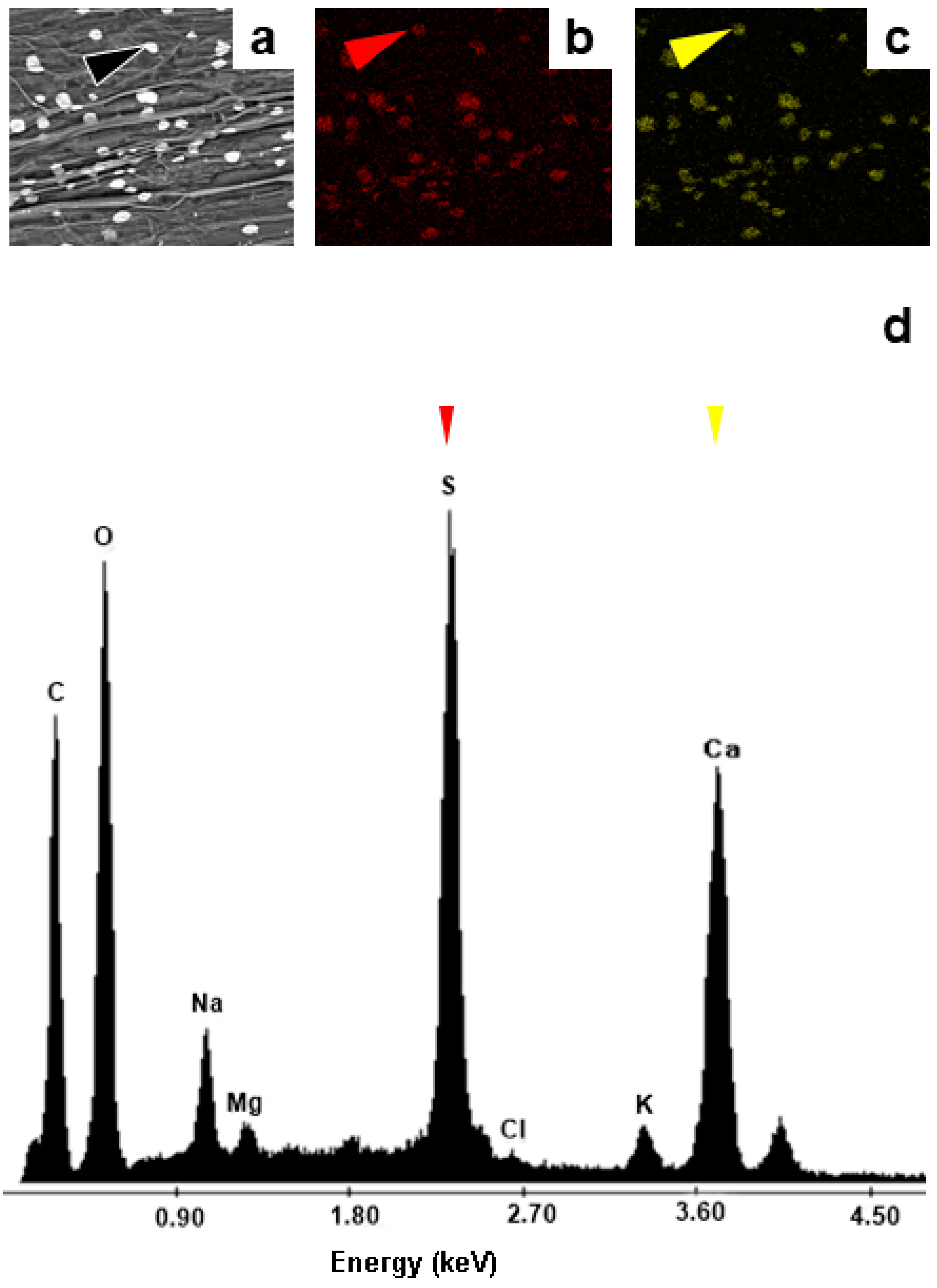

- Hammer, E.C.; Nasr, H.; Pallon, J.; Olsson, P.A.; Wallander, H. Elemental composition of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi at high salinity. Mycorrhiza 2011, 21, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.A.; Hammer, E.C.; Pallon, J.; Van Aarle, I.M.; Wallander, H. Elemental composition in vesicles of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, as revealed by PIXE analysis. Fungal Biol. 2011, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldan, B.; Janouŝka, S.; Hák, T. How to understand and measure environmental sustainability: Indicators and targets. Ecol. Indicators 2012, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, T.; Moldan, B.; Dahl, A. L. Editorial. Ecol. Indicators 2012, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, V.; Choudhary, M.; Kumar, P.; Kaswan, S.; Bajya, P. Green production strategies. In Encyclopedia of Food Security and Sustainability; Ferranti, P., Berry, E., Jock, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, B.; Ott, K.; Kenchington, R. Strong sustainability in coastal areas: a conceptual interpretation of SDG 14. Sust. Sci. 2017, 12, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.; Prasad Tollamadugu, N.V.K.V. Role of plant growth-promoting microorganisms as a tool for environmental sustainability. In Recent Developments in Applied Microbiology And Biochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; Volume 179, pp. 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, E.C.; Van Bael, S.A.; Clay, K.; Smith, M.K.H. Sulfur accumulation in gypsum-forming thiophores has its roots firmly in calcium. Estuaries Coasts 2022, 45, 1805–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Q.; Wang, Y.-H.; Song, Y.-B.; Dong, M. Formation and functions of arbuscular mycorrhizae in coastal wetland ecosystems: A review. Ecosys. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2144465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontalvo-Julio, F.A.; Tamaris-Turizo, C.E. Calidad del agua de la parte baja del río Córdoba (Magdalena, Colombia), usando el ICA-NSF. Intropica 2018, 13, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuettpelz, E.; Schneider, H.; Smith, A.R.; Hovenkamp, P....; Zhou, X.-M. A community-derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns. PPG I. J. Syst. Evol. 2016, 54, 563–603. [CrossRef]

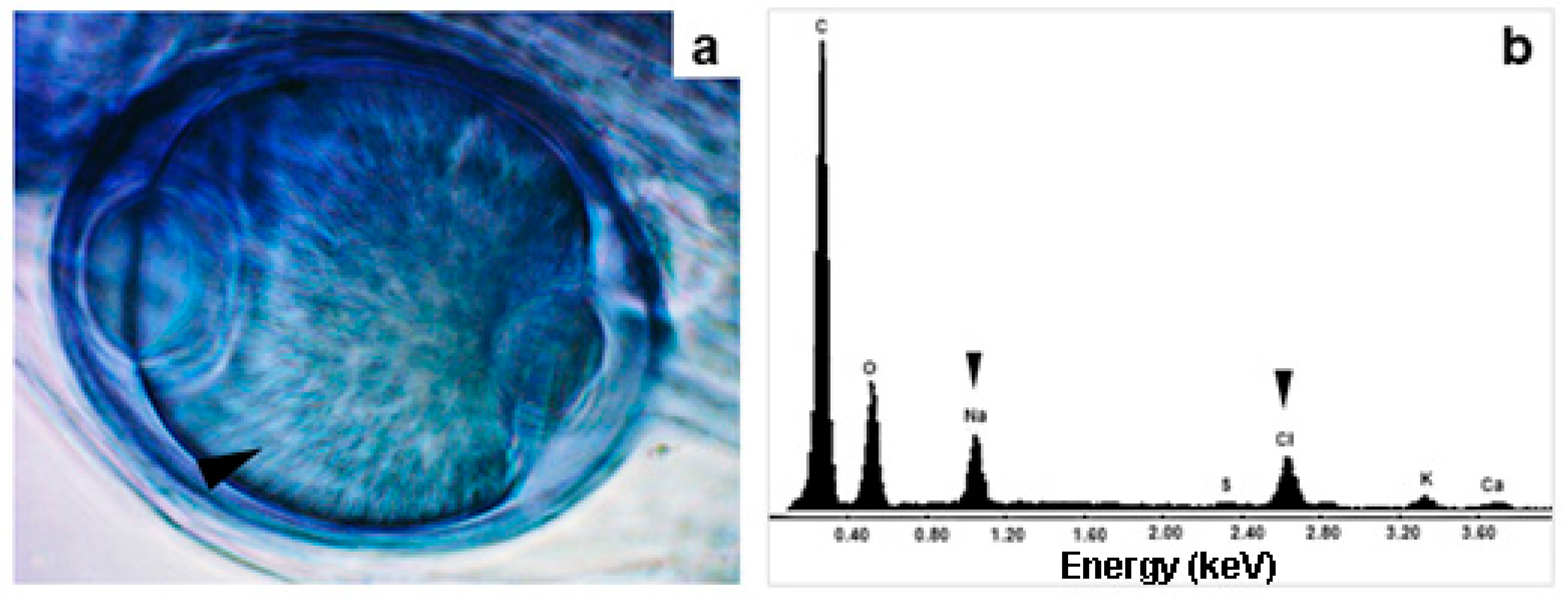

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedure of clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infections. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle, T.P.; Miller, M.H.; Evans, D.G.; Fairchild, G.L.; Swan, J.L. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, K.R.; Roy, S.; Sudheep, N.M. Assemblage and diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in mangrove plant species of the southwest coast of India. In Mangroves Ecology, Biology and Taxonomy; Metras, J.N., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, USA, 2011; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Bihari, K.M.; Sengupta, I. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in different salinity of mangrove ecosystem of Odisha, India. Adv. Plant Agric. Res. 2016, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelin, H.; Giri, B.; Kapoor, R. Contribution of Glomus intraradices inoculation to nutrient acquisition and mitigation of ionic imbalance in NaCl-stressed Trigonella foenum-graecum. Mycorrhiza 2012, 22, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, E.; Cuevas, E.; Popp, M.; Lugo, A.E. Soil salinity, sun exposure, and growth of Acrostichum aureum, the mangrove fern. Bot. Gaz. 1990, 151, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthus, E.; Wilkins, K.A.; Swarbreck, A.M.; Doddrell, N.H.; Doccula, F.G.; Costa, A.; Daviesa, J.M. Phosphate starvation alters abiotic-stress-induced cytosolic free calcium increases in roots. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 1754–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, T.; Jason Stevens, J.; Dixond, K.; Nathan Reida, N. Sulfur accumulation in gypsum-forming thiophores has its roots firmly in calcium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Veneklass, E.J.; Kuo, J.; Lambers, H. Physiological and ecological significance of biomineralization in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.J.; Mota, J.F.; Douglas, N.A.; Olvera, H.F.; Ochoterena, H. The ecology, assembly and evolution of gypsophile floras. In Plant Ecology and Evolution in Harsh Environments; Rajakaruna, N., Boyd, R.S., Harris, T.B., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, N.A.; Ali, A.M.; Mat, N. Alternative medicine from edible bitter plants of Besut, Malaysia. J. Agrobiotechnol. 2018, 9, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwumi, K.A.; Abam, E.O.; Oloyede, S.T.; Adeduro, M.N.; Adeogun, Y.A.; Uwagboe, J.E. Acrostichium aureum Linn: traditional use, phytochemistry and biological activity. Clin. Phytosci. 2022, 8, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedick, S.L. The Maya Forest: Destroyed or cultivated by the ancient Maya? PNAS 2010, 107, 953–954. www.pnas.org/content/107/3/953. [CrossRef]

- Hellmuth, N. Edible mangrove fern, Acrostichum aureum. Municipio de Livingston, Izabal, Guatemala. FLAAR (USA) and FLAAR. Mesoamérica (Guatemala). Wetlands 2022, series 3: rivers, lagoons, swamps, or ocean, Wetlands #17.

- Lara Rosales, Y.; Ocampo Castrejon, M.E. Ensayo etnobotánico de las Pteridofitas mexicanas. Tesis de Grado, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Iztapalapa, México, 1991.

- Jimenez Álvarez, S.E. Estado actual de conocimiento del uso de algunos de los helechos presentes en Colombia. Tesis de Grado, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Facultad de Ciencias, Carrera de Biología, Bogotá D. C., 7 julio de 2011.

- World Health Organization-WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/traditional-medicine-has-a-long-history-of-contributing-to-conventional-medicine-and-continues-to-hold-promise; WHO report, 2019 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Mofokeng, M.M.; Du Plooy, C.P.; Araya, H.T.; Amoo, S.O.; Mokgehle, S.N.; Pofu, K.M.; Mashela, P.W. Medicinal plant cultivation for sustainable use and commercialisation of high-value crops. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118, #12190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, O.; Singh, S.K.; Patel, D.K.; Gupta, S.; Tripathi, R.; Katekhaye, S. Cultivation, collection and processing of medicinal plants. In Bioactive Phytochemicals: Drug Discovery to Product Development; Ahmad, J., Ed.; Bentham Science Publishers: Saif Zone, Sharjah, U.A.E, 2020; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Cai, H.; Zhao, H.; Yan, Y.; Shi, J.; Chen, S.; Tan, M.; Chen, J.; Zou, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Xu, C.; Liu, X. Distribution patterns for metabolites in medicinal parts of wild and cultivated licorice. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 161, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, L.P.; Chen, B.D.; Hao, Z.P.; Wang, J.Y.; Huang, L.Q.; Yang, G.; Cui, X.M.; Yang, L.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, M.L.; Zhang, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and active ingredients of medicinal plants: current research status and prospectives. Mycorrhiza 2013, 23, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubek, S.; Blaszkowski, J. Medicinal plants as hosts of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes. Phytochem. Rev. 2009, 8, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.-L.; Zhang, M.-H.; Shi, Z.-Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, M.-G.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.-W.; Gao, J.-K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance active ingredients of medicinal plants: a quantitative analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1276918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cartabia, A.; Lalaymia, I.; Declerck, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Mycorrhiza 2022, 32, 221–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physico-chemical variables | Values |

|---|---|

| pH Electrical Conductivity (Ms/cm) |

5.45 |

| 3.08 | |

| N-NO2 (µg/L) | <LD* |

| N-NO3 (µg/L) | 2.5 |

| N-NH4 (µg/L) | <LD* |

| P-PO4 (µg/L) | 2.4 |

| Si-SiO4(µg/L) | 13916.1 |

| Pb (µg/L) | <LD* |

| Cd (µg/L | <LD* |

| Cr (µg/L) | <LD* |

| Cu (µg/L) | <LD* |

| Zn (µg/L) | 13.4 |

| Ni (µg/L) | <LD* |

| Fe (µg/L) | <LD* |

| Mn (mg/L) | 0.5 |

| Na (mg/L) | 240.3 |

| K (mg/L) | 4.6 |

| Mg (mg/L) | <LD* |

| Ca (mg/L) | 157.5 |

| Physico-chemical features texture | Values |

|---|---|

| 2 mm 1 mm |

3.3% |

| 11.5% | |

| 0.5 mm | 16.9% |

| 250 µm | 16.3% |

| 125 µm | 12.3% |

| 63 µm | 7.1% |

| ≤ 63 µm | 32.7% |

| Chemical composition | Values |

| OM ox (mg/g) | 179.5 |

| OM vol (mg/g) | 266.3 |

| Humidity (% H2O/wet weight) | 60.0 |

| N-NO3 (µg/g) | *< LD |

| N-NH4 (µg/g) | 23.4 |

| P-PO4 (µg/g) | *< LD |

| Cu (µg/g) | 7.8 |

| Zn (µg/g) | 56.7 |

| Fe (µg/g) | 20.4 |

| Mn (mg/g) | 248.2 |

| Na (mg/g) | 1.8 |

| K (mg/g) | 2.1 |

| Elements-K | Values* (% element/soil sample weight) |

|---|---|

| C K O K |

32.75± 2.16 |

| 32.18± 0.35 | |

| Na K | 1.75± 0.19 |

| Mg K | 0.62± 0.07 |

| Al K | 5.61± 0.33 |

| Si K | 18.43± 1.45 |

| S K | 0.41± 0.26 |

| Cl K | 0.60± 0.05 |

| K K | 1.05± 0.16 |

| Ca K | 3.91± 0.33 |

| Fe K | 2.71± 0.47 |

| AMF structures | Percentage of colonisation |

|---|---|

| %RL %HC |

57.93± 3.05 |

| 25.00± 10.64 | |

| %AC | 23.75± 24.62 |

| %VC | 9.29± 11.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).