Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

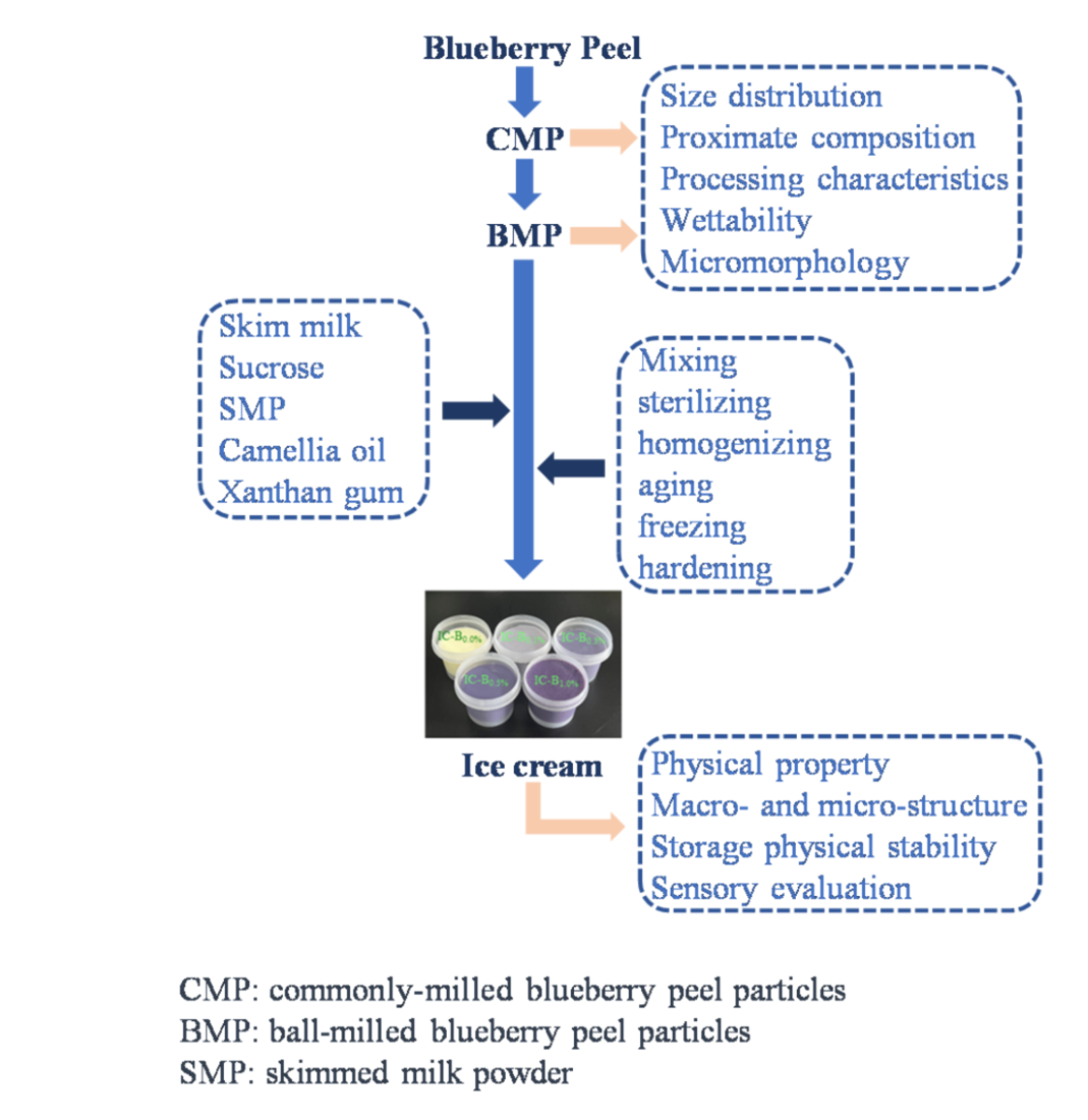

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

2.2. Preparation of blueberry peel particles

2.3. Property analysis of blueberry peel particles

2.3.1. Size distribution

2.3.2. Wettability

2.3.3. Micromorphology

2.3.4. Anthocyanin composition

2.4. Preparation of ice cream

2.5. Rheological behavior analysis of ice cream mix

2.6. Characteristic assessment of ice cream

2.6.1. Overrun, first dripping time, melting rate and firmness

2.6.2. Macro- and micro-structure observation

2.6.3. Storage physical stability

2.6.4. Sensory evaluation

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effects of ball-milling on physical properties of blueberry peel particles

3.1.1. Particle size distribution

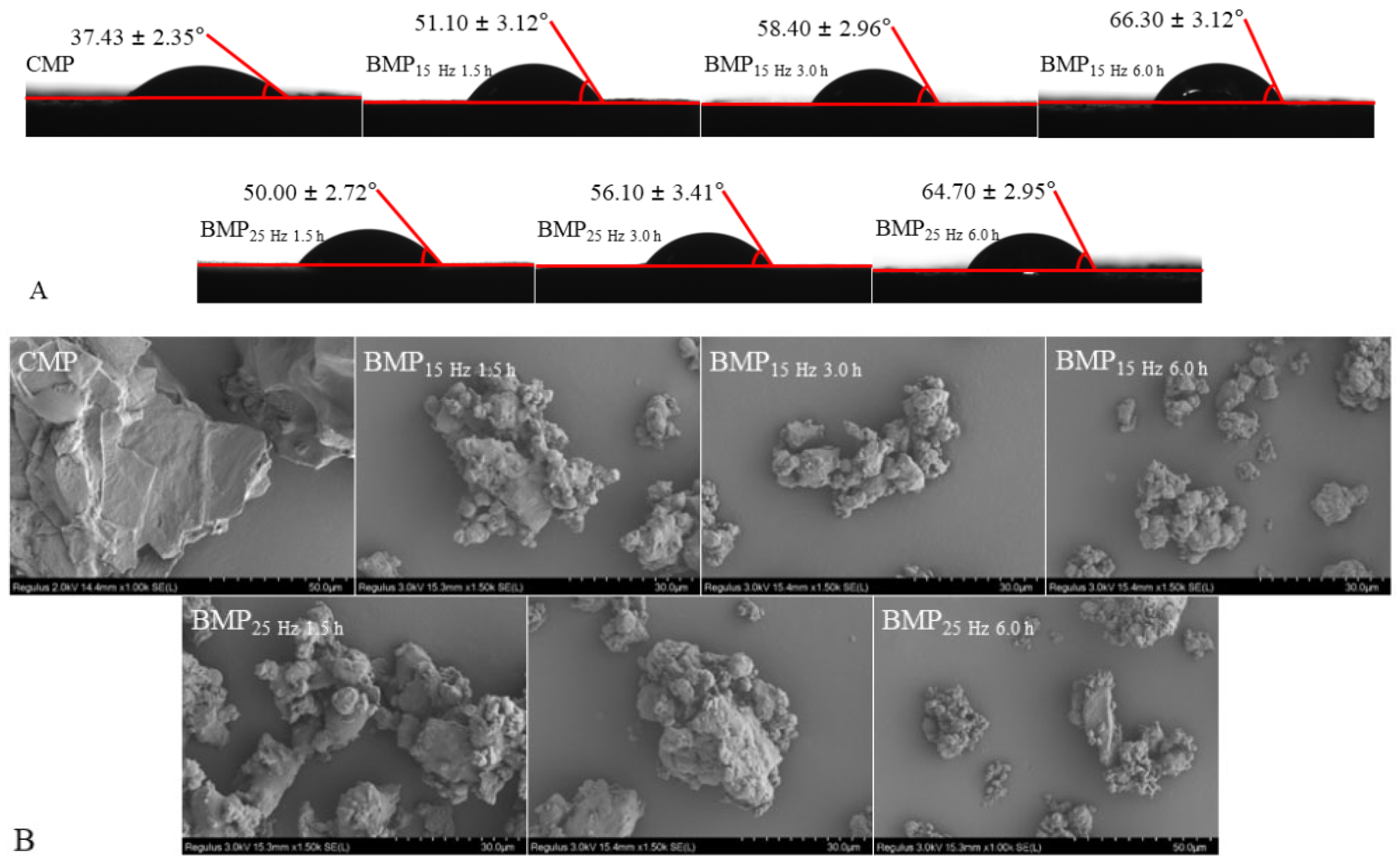

3.1.2. Surface properties

3.1.3. Microstructure

3.2. Effects of ball-milling on anthocyanin composition of blueberry peel particles

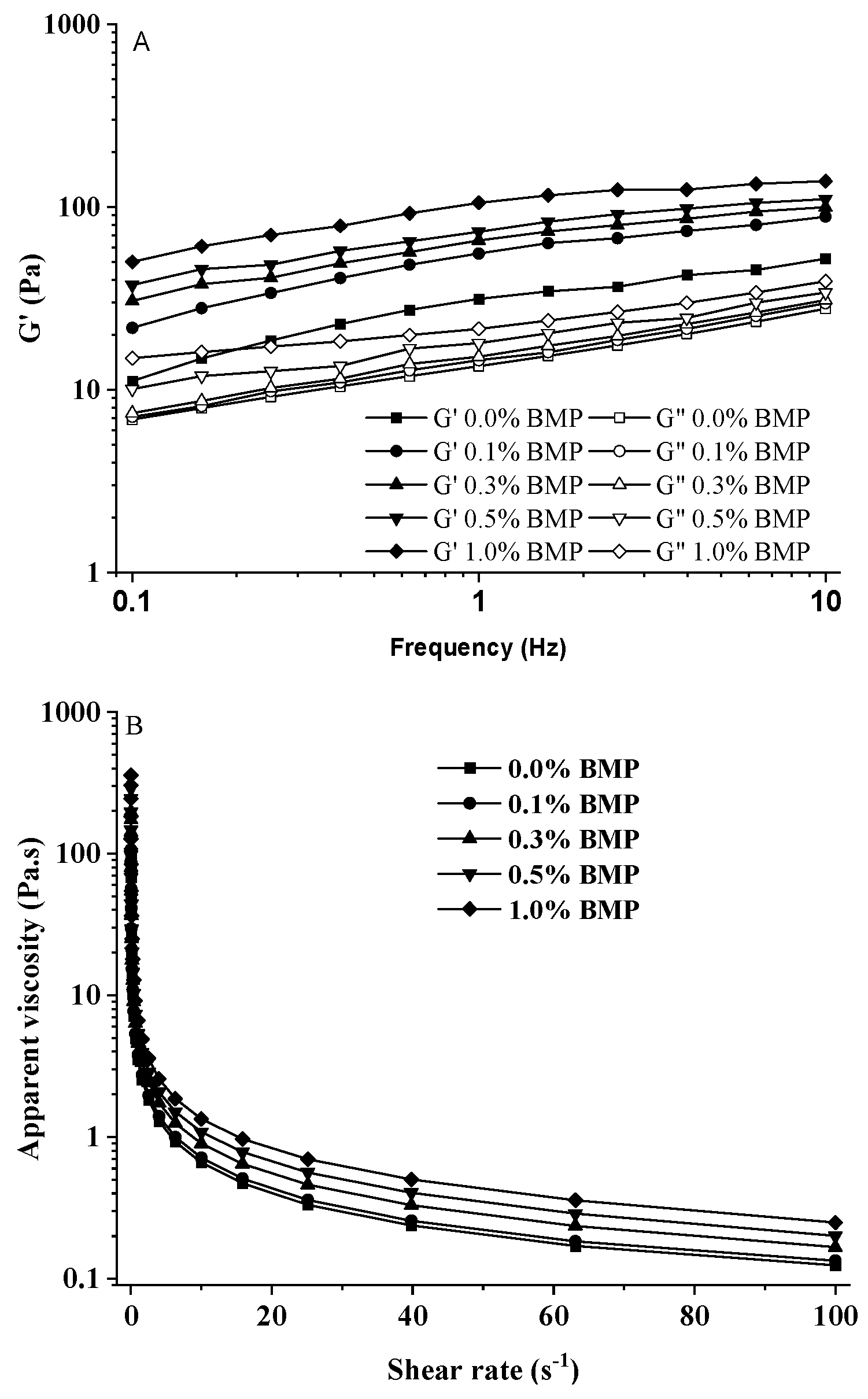

3.3. Effects of BMP on rheological behavior of ice cream mix

3.4. Effects of BMP on physico-chemical properties of ice cream

3.4.1. Overrun and firmness

3.4.2. Melting behavior

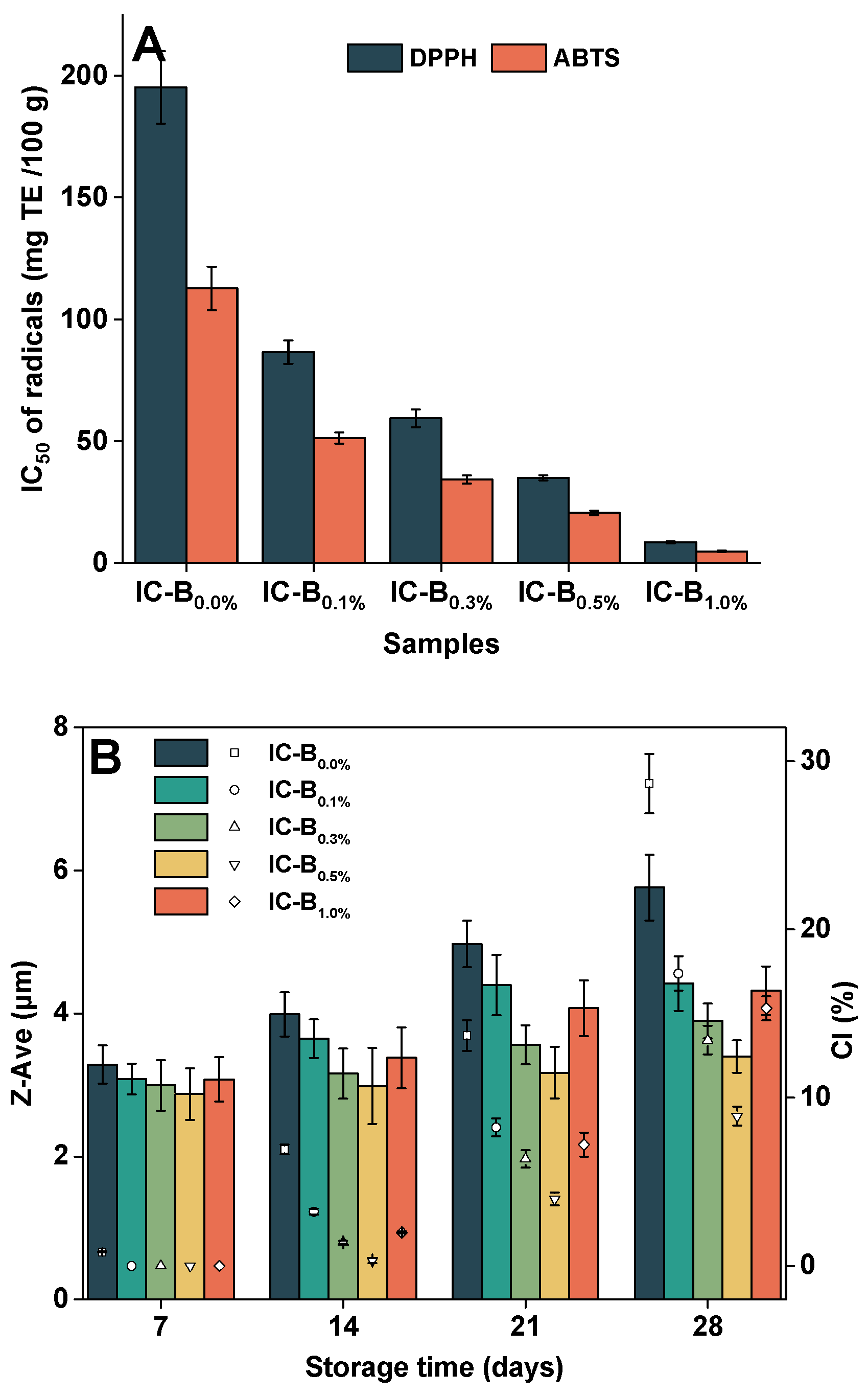

3.4.3. Antioxidant activities

3.5. Effects of BMP on storage stabilities of ice cream

3.5.1. Storage physical stability

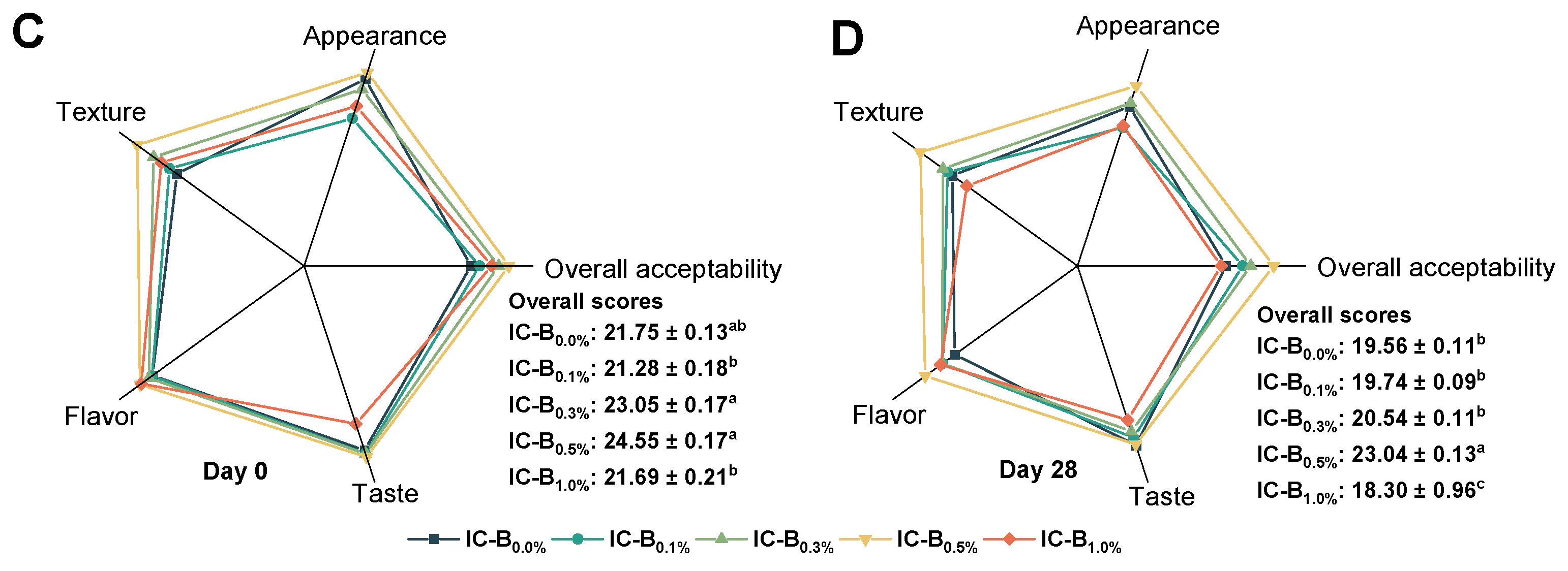

3.5.2. Sensory attributes

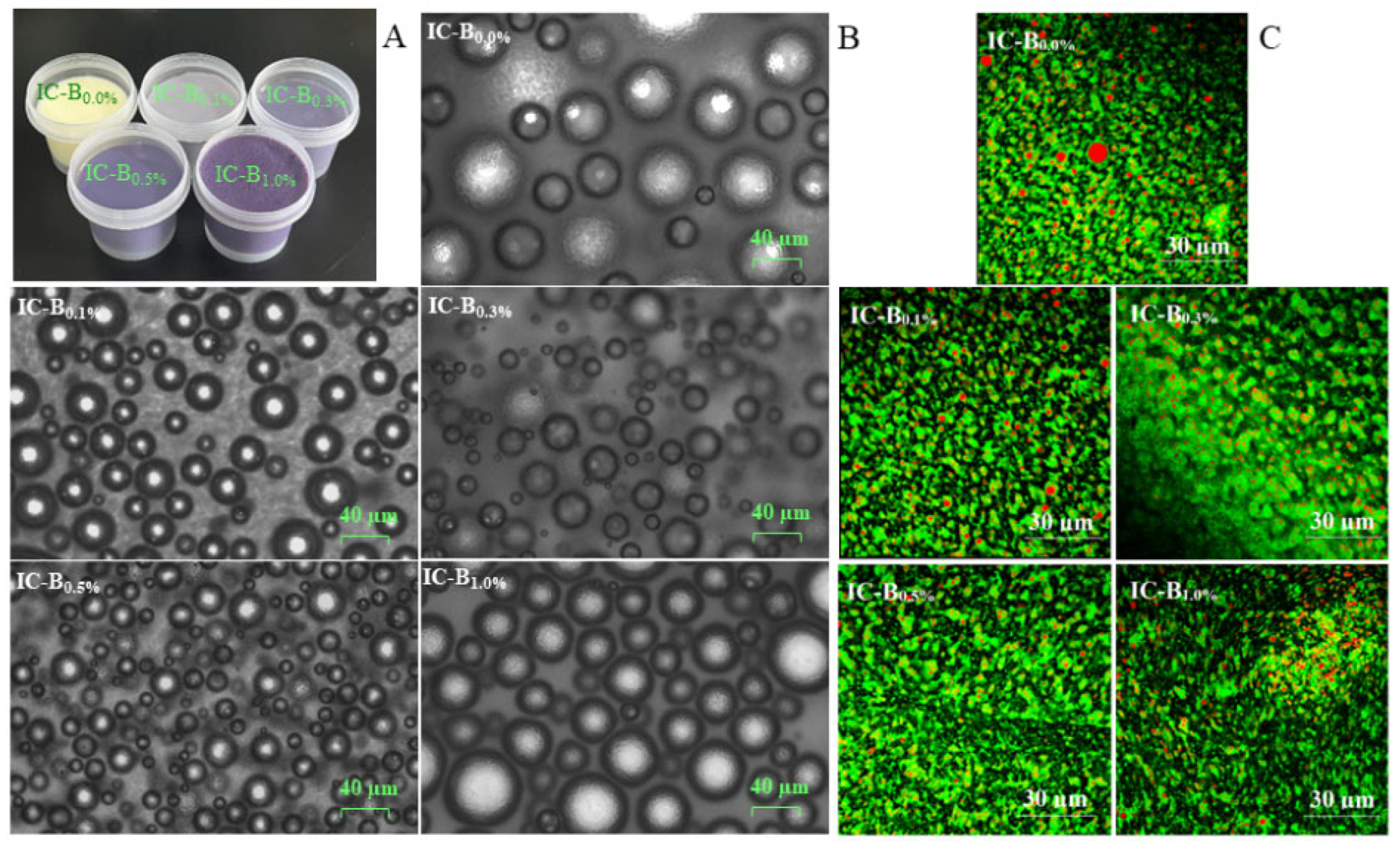

3.6. Effects of BMP on macro-and micro-structure of ice cream

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilbao-Sainz, C., Sinrod, A. J. G., Chiou, B. S., and McHugh, T. Functionality of strawberry powder on frozen dairy desserts. Journal of Texture Studies, 50: 556 - 563(2019). [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. W., Zhao, J. W., Tian, Y. Q., Jin, Z. Y., Xu, X. M., Zhou, X and Wang, J. P. Physicochemical properties of rice bran after ball milling. Journal of Food Process Preservation, 45: e15785(2021). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Mcclements, D., Wang, J., Zou, L., Deng, S., Liu, W., Yan, C., Zhu, Y. Q., Cheng, C., and Liu, C., M. Coencapsulation of (-) -epigallocatechin-3-gallate and quercetin in particle-stabilized w/o/w emulsion gels: controlled release and bioaccessibility. Journal of Agricultural and Food, 66(14): 3691 - 3699 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Ma, Y., Li, X., Yan, T., and Cui, J. Effects of milk protein-polysaccharide interactions on the stability of ice cream mix model systems. Food Hydrocolloids, 45: 327 - 336 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Chiang, L., Chen, S., and Yeh, A. Preparation of nano/submicrometer yam and its benefits on collagen secretion from skin fibroblast cells. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 60(50): 12332 - 12340(2012). [CrossRef]

- Dogan M, Kayacier A, Toker Ö S, Yilmaz M T, & Karaman S. (2013) Steady, dynamic, creep, and recovery analysis of ice cream mixes added with different concentrations of xanthan gum. Food Bioprocess Technol, 6:1420-1433. [CrossRef]

- Ewert, J., Schlierenkamp, F., Fischer, L., and Stressler, T. Application of a technofunctional caseinate hydrolysate to replace surfactants in ice cream. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 91(7): 1024 - 1031(2019). [CrossRef]

- Genovese A, Balivo A, Salvati A, Sacchi R. Functional ice cream health benefits and sensory implications. Food Research International 161 (2022) 111858. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Dou, J. Y., Li, D., and Wang, L. J. Effects of superfine grinding on properties of sugar beet pulp powder. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 87: 203 - 209(2018). [CrossRef]

- 10 Ismail, H. A., Hameed, A. M., Refaeym, M. M., Sayqal, A., and Aly, A. A. Rheological, physio-chemical and organoleptic characteristics of ice cream enriched with Doum syrup and pomegranate peel. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 13, 7346 - 7356(2020). [CrossRef]

- Javidi, F., Razavi, S. M. A., Behrouzian, F., and Alghooneh, A. The influence of basil seed gum, guar gum and their blend on the rheological, physical and sensory properties of low fat ice cream. Food Hydrocolloids, 52: 625 - 633(2016). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G. H., Ramachandraiah, K., Wu, Z. G., Li, S.J., and Eun, J.B. Impact of ball-milling time on the physical properties, bioactive compounds, and structural characteristics of onion peel powder. Food Bioscience, 36: 100630(2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, M. J., Deng, Y. Y., Pan, L. H., Luo, S. Z., & Zheng, Z. (2023). Comparisons in phytochemical components and in vitro digestion properties of corresponding peels, flesh and seeds separated from two blueberry cultivars. Food Science and Biotechnology, online. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Wang, L., Liu, Y., Wu, T., and Zhang, M. Fabricating soy protein hydrolysate/xanthan gum as fat replacer in ice cream by combined enzymatic and heat-shearing treatment. Food Hydrocolloids, 81: 39 - 47(2018). [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., and Huang, Q. Nano/submicrometer milled red rice particles-stabilized pickering emulsions and their antioxidative properties. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 68: 292 - 300(2019). [CrossRef]

- Luo, S. Z., Hu, X. F., Pan, L. H., Zheng, Z., Zhao, Y. Y., and Cao, L. L. Preparation of camellia oil-based W/O emulsions stabilized by tea polyphenol palmitate: Structuring camellia oil as a potential solid fat replacer. Food Chemistry, 276: 209 - 21(2019a). [CrossRef]

- Luo, S. Z., Hu, X. F., Jia, J. Y., Pan, L. H., Zheng, Z., Zhao, Y. Y. Mu D. D., Zhong, X. Y., and Jiang, S, T. Camellia oil-based oleogels structuring with tea polyphenol-palmitate particles and citrus pectin by emulsion-templated method: Preparation, characterization and potential application. Food Hydrocolloids, 95: 76 - 87(2019b). [CrossRef]

- Monié, A., Habersetzer, T., Sureau, L., David, A., Clemens, K., Malet-Martino, M., Perez, E., Franceschi, S., Balayssac, S., and Delample, M. Modulation of the crystallization of rapeseed oil using lipases and the impact on ice cream properties. Food Research International, 165, 112473(2023). [CrossRef]

- Moriano, M. E., and Alamprese, C. Organogels as novel ingredients for low saturated fat ice creams. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 86371e376(2017). [CrossRef]

- Muse, M. R., and Hartel, R. W. Ice cream structural elements that affect melting rate and hardness. Journal of Dairy Science, 87(1): 1 - 10(2004). [CrossRef]

- Pan, L., Wu, C., Luo, S., Luo, J., Zheng, Z., Jiang, S., Zhao, Y., and Zhong, X. Preparation and characteristics of sucrose-resistant emulsions and their application in soft candies with low sugar and high lutein contents and strong antioxidant activity. Food Hydrocolloids, 129, 107619(2022). [CrossRef]

- Pan, L. H., Wu, X. L., Luo, S. Z., He, Y. H., and Luo, J. P. Effects of tea polyphenol ester with different fatty acid chain length on camellia oil-based oleogels preparation and its effects on cookies properties. Journal of Food Science, 85(8): 2461 - 2469(2020). [CrossRef]

- Parvar, M. B., and Goff, H. D. Basil seed gum as a novel stabilizer for structure formation and reduction of ice recrystallization in ice cream. Dairy Sci. and Technol, 93: 273 - 285(2013).

- Samakradhamrongthai, R. S., Jannu, T., Supawan, T., Khawsud, A., Aumpa, P., and Renaldi, G. Inulin application on the optimization of reduced-fat ice cream using response surface methodology-sciencedirect. Food Hydrocolloids, 119: 106873(2021).

- Sayar, E., Şengül, M., and Ürkek, B. Antioxidant capacity and rheological, textural properties of ice cream produced from camel's milk with blueberry. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 64(3): e16346(2022).

- Şentürk, G., Akın, N., Göktepe, Ç. K., and Denktaş, B. The effects of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) and jujube fruit (Ziziphus jujube) on physicochemical, functional, and sensorial properties, and probiotic (Lactobacillus acidophilus DSM 20079) viability of probiotic ice cream. Food Science and Nutrion, 1 - 13(2024).

- Soukoulis, C., Lebesi, D., and Tzia, C. Enrichment of ice cream with dietary fibre: Effects on rheological properties, ice crystallisation and glass transition phenomena. Food Chemistry, 115, 665 - 671(2009). [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, L., Wojdylo, A., and Sendra, E. Antioxidant activity and protein-polyphenol interactions in a pomegranate (Punka granatum l.) yogurt. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 , 6417 - 6425(2014).

- Tsevdou, M., Aprea, E., Betta, E., Khomenko, I., Molitor, D., Gaiani, C., Hoffmann, L., Taoukis, P.S., and Soukoulis, C. Rheological, textural, physicochemical and sensory profiling of a novel functional ice cream enriched with muscat de hamburg (Vitis vinifera L.) grape pulp and skins. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 12: 665 - 680(2019). [CrossRef]

- Utpott, M., Ramos de Araujo, R., Galarza Vargas, C., Nunes Paiva, A.R., Tischer, B., de Oliveira Rios, A., and Hickmann Flôres, S. Characterization and application of red pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) peel powder as a fat replacer in ice cream. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 44: e14420(2020). [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Cock, J., Serpa, A., Vélez, L., Gañán, P., Gómez Hoyos, C., Castro, C., Duizer, L.M., Goff, H.D., and Zuluaga, R. Influence of cellulose nanofibrils on the structural elements of ice cream. Food Hydrocolloids, 87: 204 - 213(2019).

- Wang, J., Zhang, M., Devahastin, S., and Liu, Y. P. Influence of low-temperature ball milling time on physicochemical properties, flavor, bioactive compounds contents and antioxidant activity of horseradish powder. Advanced Powder Technology, 31: 914 - 921(2020).

- Wang, S. Y., Camp, M. J., and Ehlenfeldt, M. K. Antioxidant capacity and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity in peel and flesh of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) cultivars. Food Chemistry, 132(4): 1759 - 1768(2012).

- Xiao, W., Zhang, Y., Fan, C., and Han, L. A method for producing superfine black tea powder with enhanced infusion and dispersion property. Food Chemistry, 214: 242 - 247(2017). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z. Q., Yang, X. Y., Zhao, W. W., Wang, Z. Z., and Ge, Q. Physicochemical properties of insoluble dietary fiber from pomelo (Citrus grandis) peel modified by ball milling. Journal of Food and Process Preservation, 46: e16242(2022). [CrossRef]

- Yang, T., and Tang, C. H. Holocellulose nanofibers from insoluble polysaccharides of okara by mild alkali planetary ball milling: Structural characteristics and emulsifying properties. Food Hydrocolloids, 115: 106625(2021). [CrossRef]

- Yoseffyan, M., Mahdian, E., Kordjazi, A., and Hesarinejad, M. A. Freeze-dried persimmon peel: A potential ingredient for functional ice cream. Heliyon 10, e25488(2024). [CrossRef]

- Yu, B., Zeng, X., Wang, L. F., and Regenstein, J. M. Preparation of nanofibrillated cellulose from grapefruit peel and its application as fat substitute in ice cream. Carbohydrate Polymers, 254117415(2021). [CrossRef]

- Zaaboul, F., Tian, T., Borah, P. K., and Bari. V. D. Thermally treated peanut oil bodies as a fat replacer for ice cream: Physicochemical and rheological properties. Food Chemistry, 436, 137630(2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Zhu, H., Zhang, G., and Tang, W. Effect of superfine grinding on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of red grape pomace powders. Powder Technology, 286: 838 - 844(2015). [CrossRef]

| Ingredients (g/100 g) | IC-B0.0% | IC-B0.1% | IC-B0.3% | IC-B0.5% | IC-B1.0% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skim milk | 64.75 | 64.65 | 64.45 | 64.25 | 63.75 |

| Sucrose | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Skimmed milk powder | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Camellia oil | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Xanthan gum | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| BMP15 Hz 1.5h | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Samples | D10 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D90 (μm) | D[4,3] (μm) | D[3,2] (μm) | Span | Φ (%) | SSA (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMP | 29.83 ± 3.37a | 210.28 ± 2.55a | 547.68 ± 31.34a | 256.90 ± 8.43a | 56.21 ± 0.51a | 2.46 ± 0.02c | 13.60 ± 0.00d | 0.11 ± 0.00e |

| BMP15 Hz 1.5h | 5.43 ± 0.06b | 23.12 ± 0.31b | 60.95 ± 1.44c | 29.25 ± 1.02d | 11.46 ± 0.13b | 3.04 ± 0.01b c | 81.73 ± 0.03c | 0.52 ± 0.01d |

| BMP15 Hz 3.0h | 4.01 ± 0.01c | 17.36 ± 0.05c | 50.95 ± 0.26d | 23.94 ± 0.31e | 8.90 ± 0.00c | 2.70 ± 0.02c | 92.38 ± 0.02ab | 0.67 ± 0.00b |

| BMP15 Hz 6.0h | 2.62 ± 0.16e | 15.00 ± 0.14e | 36.00 ± 0.88f | 12.39 ± 0.13g | 7.91 ± 0.28e | 2.40 ± 0.03 | 100.00 ± 0.01a | 1.01 ± 0.05a |

| BMP25 Hz 1.5h | 3.85 ± 0.25c | 17.64 ± 3.44c | 75.36 ± 6.12b | 80.60 ± 4.21b | 9.47 ± 0.76c | 4.05 ± 0.01a | 91.88 ± 0.02b | 0.63 ± 0.03bc |

| BMP25 Hz 3.0h | 3.70 ± 0.12cd | 16.18 ± 1.22cd | 48.75 ± 8.31d | 43.69 ± 0.97c | 8.84 ± 0.53cd | 2.78 ± 0.02bc | 94.43 ± 0.01a | 0.68 ± 0.04b |

| BMP25 Hz 6.0h | 3.54 ± 0.01d | 15.12 ± 0.11de | 39.92 ± 0.31e | 18.90 ± 0.38f | 8.49 ± 0.05d | 2.41 ± 0.02c | 96.12 ± 0.01a | 0.71 ± 0.00b |

| No | Anthocyanins | Retention time (min) | [M-H]-(m/z) | Fragment masses | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMP | BMP15 Hz 1.5h | CMP | BMP15 Hz 1.5h | ||||

| 1 | Cy | 16.83 | 16.84 | 287.05 | 449.11, 287.06 | 0.002b | 0.006a |

| 2 | Cy-3,5-O-dig | 1.99 | 1.99 | 611.16 | 463.12, 625.18, 301.07 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| 3 | Cy-3-O-gal/glu | 5.57 | 5.61 | 449.11 | 287.06 | 8.101 | 8.102 |

| 4 | Cy-3-O-ara | 6.57 | 6.59 | 419.10 | 287.06 | 2.245 | 2.245 |

| 5 | Cy-3-O-sop | 11.75 | 11.74 | 611.16 | 317.07 | 0.099 | 0.096 |

| 6 | Cy-3-O-rut | 13.05 | 13.07 | 595.17 | 287.06 | 0.015 | 0.014 |

| Total percentage | 10.467 | 10.469 | |||||

| 7 | Dp | 13.22 | 13.22 | 303.05 | 317.07 | 0.752 | 0.764 |

| 8 | Dp-3-O-(6''-p-coumaryl)-glu | 16.42 | 16.42 | 611.14 | 303.05 | 0.070 | 0.065 |

| 9 | Dp-3-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glu | 14.51 | 14.53 | 507.11 | 303.05 | 0.373 | 0.366 |

| 10 | Dp-3-O-ara | 13.22 | 13.21 | 435.09 | 303.05 | 0.397 | 0.396 |

| 11 | Dp-3-O-gal/glu | 12.23 | 12.21 | 465.10 | 303.05 | 1.869 | 1.872 |

| 12 | Dp-3-O-rha | 5.57 | 5.58 | 449.11 | 317.07 | 8.064 | 8.061 |

| 13 | Dp-3-O-rut | 1.99 | 1.99 | 611.16 | 317.07 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Total percentage | 11.530 | 11.529 | |||||

| 14 | Mv-3-O-(6''-acetyl)-gal/glu | 10.65 | 9.92 | 535.14 | 331.08, 493.13 | 1.883 | 1.885 |

| 15 | Mv-3-O-(6''-malonyl)-glu | 9.51 | 9.51 | 579.13 | 331.08, 493.13 | 0.138 | 0.135 |

| 16 | Mv-3-O-(6-O-p-coumaryl)-O-glu | 12.37 | 12.38 | 639.17 | 331.08 | 0.094 | 0.092 |

| 17 | Mv-3-O-ara | 8.15 | 8.16 | 463.12 | 331.08 | 15.248 | 15.248 |

| 18 | Mv-3-O-gal/glu | 7.42 | 7.43 | 493.13 | 331.08 | 24.630 | 24.633 |

| 19 | Mv-3,5-O-dig | 13.09 | 13.10 | 655.19 | 287.06 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Total percentage | 41.997 | 41.997 | |||||

| 20 | Pg | 9.07 | 9.06 | 271.06 | 301.07 | 0.001b | 0.003a |

| 21 | Pg-3,5-O-dig | 13.05 | 13.05 | 595.17 | 303.05 | 0.015 | 0.013 |

| 22 | Pg-3-O-gal/glu | 7.84 | 7.85 | 433.11 | 493.13, 331.08 | 1.297 | 1.296 |

| Total percentage | 1.313 | 1.312 | |||||

| 23 | Pn | 15.76 | 15.76 | 301.07 | 303.05 | 0.002b | 0.005a |

| 24 | Pn-3-O-(6''-acetyl)-gal/glu | 10.49 | 10.44 | 505.13 | 331.08 | 0.265 | 0.262 |

| 25 | Pn-3-O-ara | 7.84 | 7.85 | 433.11 | 301.07, 463.12 | 1.297 | 1.297 |

| 26 | Pn-3-O-gal/glu | 8.15 | 8.16 | 463.12 | 433.11, 271.06 | 15.248 | 15.249 |

| 27 | Pn-3-O-sop-5-O-glu | 8.89 | 8.88 | 787.23 | 271.06 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Total percentage | 16.814 | 16.814 | |||||

| 28 | Pt | 16.84 | 16.85 | 317.06 | 303.05 | 0.018b | 0.025a |

| 29 | Pt-3-O-rut-5-O-glu | 8.89 | 8.88 | 787.23 | 317.07, 479.12, 625.18 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| 30 | Pt-3-O-(6''-acetyl) gal/glu | 9.26 | 9.27 | 521.13 | 301.07 | 0.887 | 0.883 |

| 31 | Pt-3-O-(6''-malonyl)-glu | 14.86 | 14.88 | 565.12 | 317.07, 479.12 | 0.063 | 0.060 |

| 32 | Pt-3-O-gal/glu | 6.30 | 6.29 | 479.12 | 317.07, 479.12 | 8.581 | 8.585 |

| 33 | Pt-3-O-rut | 13.00 | 12.99 | 625.18 | 317.07, 479.12 | 0.212 | 0.212 |

| 34 | Pt-3-O-p-coumaroyl-O-glu | 16.65 | 16.66 | 625.15 | 317.07, 479.12 | 0.010a | 0.005b |

| 35 | Pt-3-O-ara | 5.57 | 5.59 | 449.11 | 301.07 | 8.101 | 8.101 |

| Total percentage | 17.874 | 17.872 | |||||

| Mixes | G′ (Pa s) | G′′ (Pa s) | Tanα | G* (Pa s) | η* (Pa s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-B0.0% | 31.42 ± 1.77e | 13.47 ± 0.78cd | 0.43 ± 0.02a | 34.19 ± 2.03c | 3.52 ± 0.21d |

| IC-B0.1% | 55.65 ± 3.12d | 14.53 ± 0.85c | 0.26 ± 0.01b | 27.52 ± 1.65c | 3.80 ± 0.23cd |

| IC-B0.3% | 65.79 ± 3.27bc | 15.19 ± 0.85c | 0.23 ± 0.01bc | 67.52 ± 4.13b | 4.59 ± 0.26c |

| IC-B0.5% | 73.33 ± 4.91b | 18.02 ± 1.13b | 0.25 ± 0.02b | 75.51 ± 4.64b | 5.38 ± 0.35b |

| IC-B1.0% | 105.53 ± 6.05a | 21.56 ± 1.26a | 0.20 ± 0.01c | 107.71 ± 6.51a | 6.68 ± 0.37a |

| Samples | Overrun (%) | Firmness (N) | First dripping time (min) | Melting rate (%/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-B0.0% | 32.99 ± 0.85c | 33.15 ± 2.16a | 14.16 ± 0.93c | 3.13 ± 0.82a |

| IC-B0.1% | 36.51 ± 2.01c | 25.97 ± 1.79b | 17.43 ± 0.89b | 2.84 ± 0.03b |

| IC-B0.3% | 38.75 ± 2.34b | 19.31 ± 1.44c | 18.54 ± 1.01a | 2.83 ± 0.08b |

| IC-B0.5% | 45.13 ± 3.06a | 19.03 ± 1.18c | 20.18 ± 1.07a | 2.71 ± 0.02b |

| IC-B1.0% | 38.22 ± 2.92ab | 24.41 ± 1.42b | 18.00 ± 1.10ab | 2.77 ± 0.11ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).