Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Blue Economy and Maritime Security

- the interconnected nature of maritime security challenges;

- the liminality of maritime security – that is, that most maritime security problems cannot be understood nor addressed without a consideration of their linkages to challenges on land;

- the transnational nature of maritime security given that the sovereignty of the high seas is shared, with jurisdiction there being international in theory, but also varying depending on the given circumstances pertaining to a threat or incident; and

- that, by extension, the maritime domain is essentially cross-jurisdictional.

- While not rejecting the state as a security referent, it argues for the inclusion of other referents, most notably, individuals and communities.

- It recognizes that threats such as climate change, pandemics and financial crises are transnational in nature and require non-military responses.

- Given that threats have transborder implications, international multilateral cooperation is critical.

- Non-state actors and international institutions are seen as having important roles in the global governance of emerging threats.

Governmentality, ‘the International’, and Risk

‘‘In contrast to sovereignty, government has as its purpose not the act of government itself, but the welfare of the population, the improvement of its conditions, the increase of its wealth, longevity, health etc.’’Foucault ([1978] 1991:100)

“ ‘Discipline’ may be identified neither with an institution nor with an apparatus; it is a type of power, a modality for its exercise, comprising a whole set of instruments, techniques, procedures, levels of application, targets, it is a ‘physics’ or an ‘anatomy’ of power, a technology.” .Foucault 1977: p215

“By objectifying interdependent threats as risks, collective security can operate as an insurance regime; it can invert the meaning of threats, transforming them from obstacles into opportunities for regulation. Conceptualizing threats as risks means that threats no longer constitute discrete, absolute, and existential dangers emanating from an external enemy; rather, they represent serial, graduated, and calculated hazards stemming from the interconnected collective security ‘system’ itself.”

Method

| Title | Spatial remit | Focus | Publisher/date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue economy flagship. A briefing note for partnership. | African Continent | Prepared for Blue Economy Conference in Nairobi, Kenya, 26-28 November 2018. | African Development Bank Group, 2018 |

| 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime strategy (2050 aim strategy). | African Continent | Maritime strategy | African Union (2012) |

| Conference Report. African Ministerial Conference on the Environment. Seventeenth session | African Continent | Marine environment | AMCEN (2019). |

| Africa Blue Economy Strategy. Nairobi, Kenya. Strategy report and Annex’s 1-5 | African Continent | Blue Economy development | AU-IBAR, 2019. |

| Development of the AUDA-NEPAD Blue Economy Programme. Messages from Stakeholders | African Continent | Blue Economy development | AUDA-NEPAD 2019. |

| Introducing the sustainable blue economy finance principles | Global | Blue Economy finance | European Commission (2017). |

| Declaration of the sustainable blue economy finance principles. | Global | Blue Economy finance | European Commission (2018) |

| Sector plan for blue economy. State Department for Fisheries, Aquaculture and the Blue Economy, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation. | Kenya | Blue Economy development | Government of Kenya (2018). |

| High Level Panel For A Sustainable Ocean Economy, Western Indian Ocean (WIO) Regional Meeting. 2 – 3 December 2019, Mombasa, Kenya. Meeting Report | WIO Region | Blue Economy development | HLP, 2019. |

| A regional strategy for conserving marine ecosystems and fisheries of the Western Indian Ocean Islands Marine Ecoregion (WIOMER). | WIO Region | Marine environment | Indian Ocean Commission (IOC). 2010. |

| Building the Blue Economy in the Western Indian Ocean. 8th Conference of Parties Meeting for the Nairobi Convention, 22-24 June 2015 Mahé, Seychelles. Blue Economy and Oceans Governance Workshop | WIO Region | Blue Economy development | Kelleher, K. (2015). |

| Ministerial segment, Durban, South Africa, 14 and 15 November 2019. Advancing the blue/ocean economy in Africa | African Continent | Blue Economy development | AMCEN (2019) |

| Seychelles Blue Economy: Strategic Policy Framework and Roadmap. Charting the future (2018–2030). | Seychelles EEZ | Blue Economy development | Republic of Seychelles (2019). |

| Report On The Global Sustainable Blue Economy Conference. 26th – 28th November 2018, Nairobi, Kenya | Global / Africa | Blue Economy development | SBEC (2018) |

| The Nairobi Statement of Intent on Advancing the Global Sustainable Blue Economy. Sustainable Blue Economy Conference, Nairobi, Kenya | Global / Africa | Blue Economy development | SBEC (2018). |

| Unlocking the full potential of the blue economy: Are African Small Island Developing States ready to embrace the opportunities? Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | African continental islands | Blue Economy development | UNECA (2014) |

| Africa’s Blue Economy: A policy handbook. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | African Continent | Blue Economy development | UNECA (2016a) |

| The Blue Economy. Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | African Continent | Blue Economy development | UNECA (2016b) |

| Blue Economy, Inclusive Industrialization and Economic Development in Southern Africa. The 24th Session of the Inter-Governmental Committee of Experts (ICE) (Senior Government Officials) of Southern Africa. 18 – 21 September 2018, Balaclava, Mauritius. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | Southern Africa | Blue Economy development | UNECA (2020) |

| AFRICA’S BLUE ECONOMY: Opportunities and challenges to bolster sustainable development and socioeconomic transformation. Issue Paper produced for the Sustainable Blue Economy Conference. 26th – 28th November 2018, Nairobi, Kenya | African Continent | Blue Economy development | UNECA (2018) |

| Transformative Growth in Eastern Africa: Catalysts and Constraints. ECA-EA/ICE/21 | Eastern Africa | Regional Economic Development | UNECA (2017) |

| Green Economy in a blue world. Nairobi, Kenya | Global | Sustainable ocean development | UNEP (2012) |

| Report of the eighth conference of parties to the convention for the protection, management and development of the marine and coastal environment of the Western Indian Ocean (Nairobi Convention). Mahé, Seychelles. 22-24 June, 2015. | WIO Region | Marine environment | UNEP (2015) |

| Marine Spatial Planning of the Western Indian Ocean Blue Economy. UNEP/NC/FP/2017/4/Doc/13 | WIO Region | Spatial planning | UNEP (2017) |

| The Potential of the Blue Economy: Increasing Long-term Benefits of the Sustainable Use of Marine Resources for Small Island Developing States and Coastal Least Developed Countries. World Bank, Washington DC. | Global | Blue Economy development | World Bank (2017a) |

| The Ocean Economy in Mauritius: Making it happen, making it last. Washington DC, USA | Mauritius | Blue Economy development | World Bank Group (2017b) |

| Principles For a Sustainable Blue Economy. | Global | Blue Economy development | WWF (2017a) |

| Reviving The Western Indian Ocean Economy. Gland, Switzerland | WIO Region | Blue Economy development | WWF (2017) |

| Organisation | Expertise | Date of interview |

|---|---|---|

| International BE informants | ||

| 1. Association for Coastal Ecosystem Services (ACES) | Administering community accreditation and carbon credit sales | 05.11.2021 |

| 2. AU-IBAR* | Intergovernmental Agency | 03.05.21 Online |

| 3. AUDA-NEPAD | Blue Economy policy | 12.04.2021 Online |

| 4. Contact Group**** | Maritime security | 22.04.21 Online |

| 5. CORDIO East Africa | International ocean governance | 20.04.21 Online |

| 6. IGAD** | Regional Economic Community | 27.04.21 Online |

| 7. Independent Expert | International ocean governance | 08.04.21 Online |

| 8. Independent Expert | International ocean governance | 18.05.21 Online |

| 9. Indian Ocean Commission | Regional collaboration for ocean governance | 15.05.2021 Online |

| 10. Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) | International environmental policy coordination | 15.05.21 Online |

| 11. IOTC (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission) | International Fisheries Policy Coordination | 17.05.21 Online01.03.22 In person |

| 12. Nairobi Convention | International environmental policy coordination | 22.06.21 Online |

| 13. Plan Vivo | Accreditation body for carbon credits | 01.12.2021 |

| 14. RMIFC | Maritime crime and surveillance coordination | 27.05.2021 Online |

| 15. UNEPFI Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Initiative | Sustainable finance | 04.05.2021 Online |

| 16. WIOMSA (Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association) | Marine science and evidence-based policy | 04.05.2021 Online |

| 17. WWF | Sustainable finance | 18.05.2021 Online |

| Kenya cases | ||

| 18. Beach Management Unit | Community based fishery management | 18.12.2021 |

| 19. County Adminstration | Coastal fishery management in Lamu County | 4.11.21 and 20.12.21 |

| 20. Crab Shack | Community-led environmental cons4ervation and eco-tourism | 31.10.21 and 28.01.22 |

| 21. Debaso Creek Conservation Association (Prawn Shack) | Community-led environmental cons4ervation and eco-tourism | 30.10.21 |

| 22. EU Delegation, Kenya | GoBlue project and inter-County cooperation in Kenya | 08.12.21 |

| 23. Gazi Community Forest Association | Community-based resource management | 27.10.21 In person |

| 24. Go Blue project | Coastal blue economy development programme | |

| 25. Government of Kenya | Blue Economy policy | 17.11.21 In person |

| 26. Government of Kenya | Blue Economy policy | 16.03.22 In person |

| 27. Jumuiya ya Kaunti za Pwani | Policy coordination for coastal Counties in Kenya | 03.11.21 and 25.01.21 |

| 28. Kenya Wildlife Service, Watamu Marine National Park and Reserve | Wildlife governance and community engagement | 29.01.22 |

| 29. Kibuyuni Seaweed Cooperative | Seaweed farmers | 05.12.21 |

| 30. Kumbatia Seafood | Fish marketing start-up | 08.12.21 (in person), 16.12.21 (online), 27.01.22 |

| 31. Lamu County Government | Spatial Planning | 03.12.21 |

| 32. Lamu Environment Foundation | Community environmental conservation | 23.11.21 |

| 33. Lamu Marine Conservation Trust | Local marine conservation, eco-tourism and plastic waste management | 03.12.21 |

| 34. LAPSSET CDA | Port Development -spatial planning | 19.10.21 In person |

| 35. LAPSSET CDA | Port Development - community liaison | 16.03.22 In person |

| 36. LAPSSET CDA | Port Development – construction management | 02.12.21 In person |

| 37. Lobster fishers, Lamu | Artisanal fishing | Various, Oct/Nov 2021 |

| 38. Paté Marine Community Conservancy | Octopus fishers, Paté Island | 22.12.21 |

| 39. Paté Marine Community Conservancy | Community Conservancy leaders, Paté Island | 22.12.21 |

| 40. Paté Marine Community Conservancy | Marine Conservancy security staff, Paté Island | 22.12.21 |

| 41. Save Lamu | Community Action Group | 15.11.21, 25.11.21, and 24.12.21 |

| 42. Taka Taka Heroes | Community plastic waste collection and recycling | 23.12.21 |

| 43. Technical University of Mombasa | Blue economy innovation | 09.03.21 |

| 44. TNC (The Nature Conservancy), Kenya | Coastal resource conservation | 10.11.21 and 5.1.22online |

| 45. UNEP, Kenya programmes | Lamu port development | 21.10.21 |

| 46. WWF Kenya | Conservation management in Lamu County, Kenya | 29.10.21 |

| Seychelles cases | ||

| 47. Development Bank of Seychelles | Administration of Blue Bond finance | 21.02.22 |

| 48. Enterprise Seychelles Agency | Entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem | 01.03.22 |

| 49. Entrepreneur | Fishing post-harvest sector | 22.02.22 |

| 50. Fishing Boat Owners Association | Fishing sector | 24.2.22 In person |

| 51. Government of Seychelles | National fishery policy (SWIOFISH programme) | 17.02.22 Online |

| 52. Government of Seychelles | National fisheries operational administration | 24.02.22 |

| 53. Government of Seychelles | National BE Policy (group interview) | 14.04.21 Online23.02.22 In person |

| 54. Government of Seychelles | National policy development | 25.02.22 |

| 55. Government of Seychelles | Blue Economy Policy | 03.03.22 In person |

| 56. Government of Seychelles | Mascarene Joint Management Area coordination | 16.04.21 |

| 57. Government of Seychelles | Fisheries policy | 01.03.22 |

| 58. Government of Seychelles (NC representation) | International environmental policy coordination | 28.04.21 Online |

| 59. Government of Seychelles JMA*** | International environmental policy coordination | 16.04.21 Online |

| 60. Government of Seychelles, Department of Environment | Marine spatial planning and its implementation framework | 03.03.22 |

| 61. Government of Seychelles, Ministry of Internal Affairs | Maritime transnational organised crime | 29.04.2021 Online |

| 62. Independent Expert | Carbon accounting | 21.02.22 In person |

| 63. Independent expert | Seychelles fisheries management and aquaculture development | 03.03.22 |

| 64. Petroseychelles | State owned petrochemicals development agency | 25.02.22 |

| 65. SeyCCAT (Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust) | Community-led BE innovation | 16.03.22 |

| 66. SeyCCAT | Seagrass conservation and blue carbon | 17.03.22 |

| 67. SeyCCAT | Multistakeholder workshop regarding seagrass conservation and blue carbon | 23.02.22 |

| 68. Seychelles entrepreneurs | Meetings with BE entrepreneurs funded by SeyCCAT grants programme. | Feb/March 2022 |

| 69. The Guy Morel Institute | Entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem | 03.03.22 |

| 70. TNC (Seychelles) | Marine spatial planning | 16.03.22 |

| 71. TNC, Seychelles | Coastal resource conservation / Marine Spatial Planning | 16.02.22 In person |

| Organisation | Expertise | Code | Date of interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government of Seychelles, Ministry of Internal Affairs | Maritime transnational organised crime | GoS | 29.04.2021 |

| Indian Ocean Commission | Regional collaboration for ocean governance | IOC | 15.05.2021 |

| AUDA-NEPAD | Blue Economy policy | AUDA | 12.04.2021 |

| RMIFC | Maritime crime and surveillance coordination | RMIFC | 27.05.2021 |

Findings

Evolution of Maritime Security in the WIO

Spaces of Risk

- From piracy is LOW (an attack is unlikely).

- From conflict-related activity is MODERATE for KSA- and SLC-flagged vessels (an attack is possible but unlikely) and LOW for the others. The threat against vessels of any flag operating from or to ports operated by actors in the Yemen Conflict is considered MODERATE.

- From terrorism is LOW (an attack is unlikely)6”

| Area | Regime/Technlogy | Responsibilities |

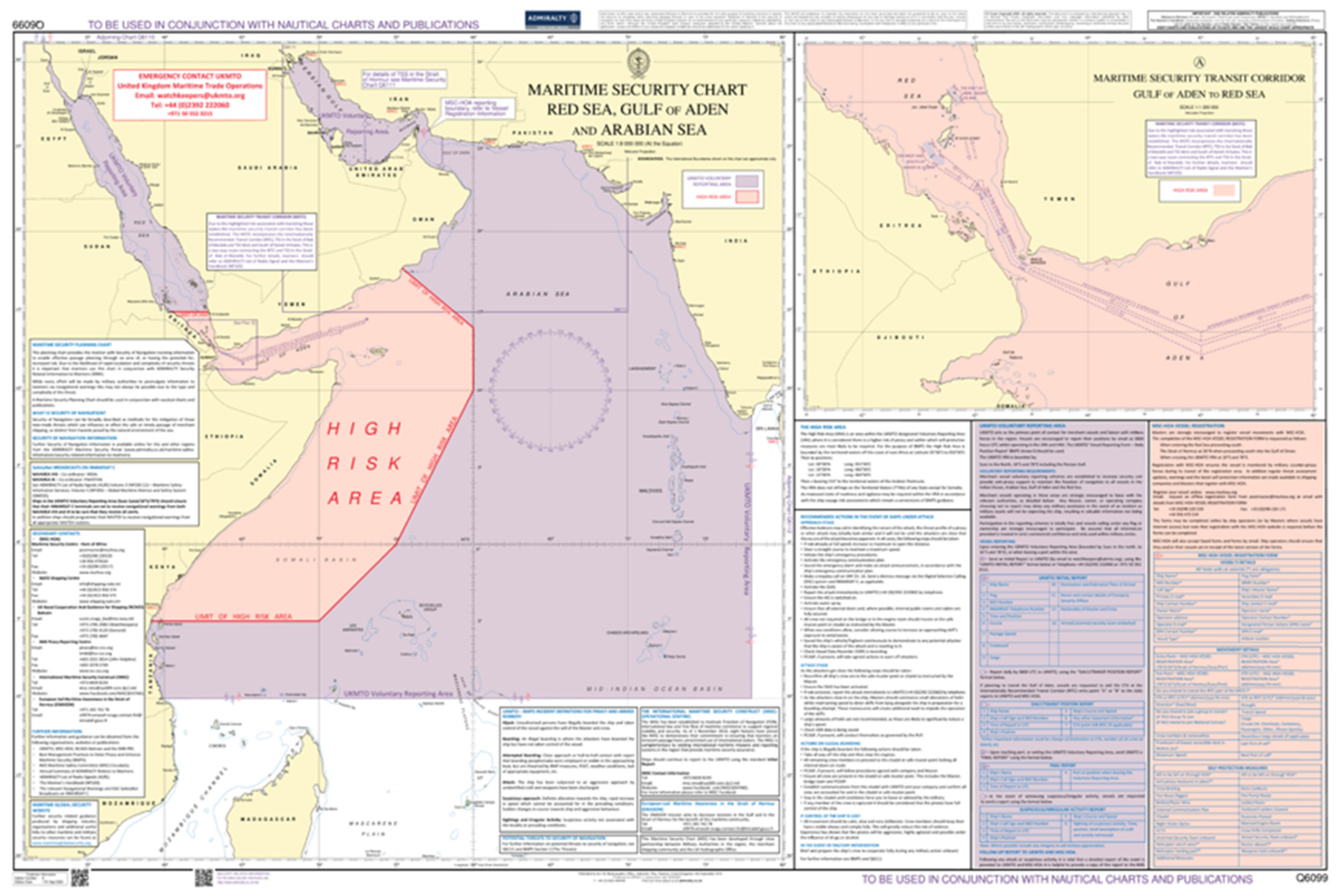

| Voluntary Reporting Area (VRA). The VRA represents the beginnings of a shift from Sovereign surveillance - naval powers patrolling the seas (CTF151) - to a system in which subjects (Merchant Vessels) start to discipline their own behaviours, by reporting on their movements, on perceived threats, and undertaking to respond to piracy risk reports and alerts. This space is created by naval powers in response to a widely dispersed threat of piracy, in which the subjects themselves are enrolled to contribute to the regime by gathering and sharing knowledge. | ● UKMTO Reporting regime – daily transit position, incidents and suspicious activity ● MSCHoA Registration scheme (itinerary and vulnerability related information) and issuance of risk assessment reports (combined intelligence from CMF, UKMTO and EU NAVFOR) by means of online platform ● Operationalised Maritime Security Transit Corridor (MSTC) through which vessel movements are coordinated by MSCHoA. Includes the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) through which group transits and national convoys may be offered ● CMF CTF151 Maritime Security Transit Corridor surveillance and protection ● UKHO Maritime Security Chart Q6099 |

● Combined Maritime Force (CMF) – security operations ● UK Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) – vessel monitoring and risk assessment ● Maritime Security Centre Horn of Africa (MSCHoA) – vessel monitoring and risk assessment (part of EU NAVFOR) ● Vessel owners / Masters – applying best management practices including reporting and on-board security measures |

| BMP High Risk Area8. In contrast to the VRA, this is an industry- (i.e. subject-) led initiative (its development led by IMO) with the clear aim to promote self-discipline amongst merchant vessels in such a way as to mitigate risks arising from piracy in line with strategy of Maritime Powers to combat the piracy risk and related threats to the global shipping industry. This space is constructed by the subjects, at the request of maritime powers (through UN Security Council resolution S/RES/1851 and Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, CGPCS). It responds to the specific threats of vessel capture and ransom, to crew safety, and of economic losses incurred in mitigating these risks. | The High Risk Area (HRA) is an industry defined area within the VRA where it is considered that a higher risk of attack exists, and additional security requirements may be necessaryBest Management Practices (to deter Piracy and Enhance Maritime Security in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea) should be applied by vessel owners and Masters, including: threat and risk assessment, planning, ship protection measures, reporting.Lists ‘common understandings’ (definitions) for use in reporting attacks and suspicious activity | Vessel owners / Masters – applying best management practices including reporting and on-board security measures |

| Joint War Committee Listed Area. This risk space is created by the insurance industry. It requires merchant vessels to notify insurance underwriters of intent to transit the specified area, which is similar but not exactly congruent with the HRA. The aim is to enable the insurers to mitigate their own underwriting risks in relation to piracy (theft, damage, ransom, harm to passengers and crew, operational losses) by imposing conditions upon the insured subject, either high premiums to reflect higher risk, or the implementation of mitigation measures, or some combination of the two. | The Listed Area is an area of perceived enhanced risk on behalf of insurance underwriters. Ships entering the area are required to notify their insurers. Mitigation measures apply on a case by case basis. | Vessel owners – notification of insurance underwriters and application of required mitigation actions |

- Widespread implementation of Best Management Practice (BMP).

- The embarkation of PAST [private armed security teams on vessels].

- The continued presence and monitoring of CMF, EU NAVFOR, other warships and maritime patrol aircrafts in the region.

- The prospect of a prison sentence for pirates.

- The adoption by former pirates of lower risk, yet profitable, criminal activities such as smuggling.

- Improvements in the capabilities and competence of Somali maritime security forces, such as the Somaliland Coast Guard.”

- The shipping industry ceases to fully implement BMP or embark PAST following an owner’s vessel risk assessment.

- There is a significant decrease in the presence of warships and local maritime security forces in the area.

- The decline in economic and political situation persists, further exacerbating poverty and instability in Somalia and the wider region due to COVID-19, famine, the ripple effects of flooding and locust infestation.”

A Blue Economy Shift….

New Maritime Security Architecture

Discussion

Spaces of Risk and Discipline Governmentality

“Continuing to be gravely concerned by the dramatic increase in the incidents of piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia in the last six months, and by the threat that piracy and armed robbery at sea against vessels pose to the prompt, safe and effective delivery of humanitarian aid to Somalia, and noting that pirate attacks off the coast of Somalia have become more sophisticated and daring and have expanded in their geographic scope, notably evidenced by the hijacking of the M/V Sirius Star 500 nautical miles off the coast of Kenya and subsequent unsuccessful attempts well east of Tanzania,”(S/RES/1851, 2008)

“Operating in these waters requires thorough planning and the use of all available information. The maritime threat environment is dynamic; the risks will not remain constant for subsequent visits. It is essential therefore, that Masters, Ship Security Officers and Company Security Officers carry out detailed Risk Assessments for each voyage to the region and for each activity within the region.

All vessels transiting the Gulf of Aden and Bab Al Mandeb should follow the guidance of BMP5 to the maximum extent possible and consider the use of embarked armed security. Recent piracy attacks in 2017 serve to emphasise the importance of robustly following this guidance.

Global Governmentality

“The EU understands that the oceans, and in particular the Indian Ocean, are not only a shared space but also a shared responsibility.…. Sustaining the progress made so far means that we need to support our partners in the Indian Ocean in building their own capacities.” Statement by M. Neven Mimica, EU Commissioner for International Cooperation and Development(IOC. 2019: 11)13

“The recent events [with three acts of piracy off the Somali coasts after five years of calm], reminded us that maritime insecurity remains a major challenge in the Western Indian Ocean. That is why we must not slacken our efforts.” In addressing a broad range of threats “The added value of the EU-financed MASE Programme lies in the fact that it is covering all aspects of maritime security and safety”. Statement by Hamada Madi, Indian Ocean Commission’s General-Secretary. April 201714

“you cannot push for developing the blue economy if the maritime security is not at a certain level…….so that is the main reason for the countries to join [the RMIFC]”.(IOC, 2021)

Panoptic Surveillance

“if we monitor .... then the vessels know that they are being monitored … so that will drastically reduce [illegal activity]...... all the challenges that we have in the oceans now [are included]”.(IOC, 2021)

Territorialisation of the Oceans

Conclusion

Disclosure statement

Acknowledgements

References

- Aalberts, T. E, and Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. (2014). Sovereignty at Sea: The Law and Politics of Saving Lives in Mare Liberum. Journal of International Relations and Development 17(4): 439–68.

- AU (2012). Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy. African Union.

- AU (2016) African Charter on Maritime Security and Safety and Development in Africa (Lomé Charter).

- AU (2019) Africa Blue Economy Strategy.

- AU-IBAR (2019). Africa Blue Economy Strategy. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Barbesgaard, M. (2018). Blue growth: savior or ocean grabbing? Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(1), 130–149. [CrossRef]

- Bohle, J. (2018). Hurricane-riskscapes and governmentality. Erdkunde, 2(June), 91–102.

- Bueger, C. (2015). What is maritime security? Marine Policy, 53, 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Beuger, C (2017). “Ocean Shield” Achieved its Mission. The Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com/blog/ocean-shield-achieved-its-mission.

- Bueger, C. (2018). Territory, Authority, Expertise: Global Governance and the Counter-Piracy Assemblage, European Journal of International Relations 24(3): 614-637.

- Bueger, C., & Edmunds, T. (2017). Beyond seablindness: A new agenda for maritime security studies. International Affairs, 93(6), 1293–1311. [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Anthony, M. (2016). Understanding Non-traditional Security. In An Introduction to Non-Traditional Security Studies: A Transnational Approach (pp. 1–14). Sage Publications, London. [CrossRef]

- Castel, R. (1991), ‘From Dangerousness to Risk’, in G. Burchell, C. Gordon and P. Miller, eds, The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Choi, Y. R. (2017). The Blue Economy as governmentality and the making of new spatial rationalities. Dialogues in Human Geography, 7(1), 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Dean, M (1999). Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. Sage.

- Elliot, A., & Holzer, G. S. (2009). The invention of ‘terrorism’ in Somalia: Paradigms and policy in US foreign relations. South African Journal of International Affairs, 16(2), 215–244. [CrossRef]

- Elmer, G (2012). Panopticon—discipline—control. In: Ball, K., Haggerty, K., & Lyon, D. (2012). Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies. [CrossRef]

- Environmental Justice Atlas. Toxic waste dumping, Somalia. Accessed July 2021 https://ejatlas.org/conflict/somalia-toxic-waste-dumping-somalia;

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 7(3), 161–173. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, Michel. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by A. Sheridan. Penguin.

- Foucault, M. ([1978] 1991) Governmentality. In: The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality, edited by Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon and Peter Miller. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Foucault, M. (1998) The Will to Knowledge: the history of sexuality volume 1 (London: Penguin Books), French original 1976.

- Foucault, M. (2007) Security, Territory, Population. Palmgrave Macmillan, UK. (Translated by Graham Burchell, Edited by Michel Senellart.

- Glaser SM, Roberts PM, Mazurek RH, Hurlburt KJ, and Kane-Hartnett L (2015) Securing Somali Fisheries. Denver, CO: One Earth Future Foundation. [CrossRef]

- Glaser SM, Roberts PM and Hurlburt KJ (2019) Foreign Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing in Somali Waters Perpetuates Conflict. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:704. [CrossRef]

- Glück, Z. (2015). Piracy and the Production of Security Space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 33(4):642-659.

- Guilfoyle, D. (2013). Prosecuting Pirates: The Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, Governance and International Law. Global Policy. 4 (1): 73-79.

- Hindess, B. (2005). Politics as Government : Michel Foucault’s Analysis of Political Reason. Alternatives, 30(4), 389–413.

- IMO (2009). The Code of Conduct concerning the Repression of Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in the Western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden (Djibouti Code of Conduct).

- IMO (2017). Jeddah Amendment to the Djibouti Code of Conduct 2017.

- IOC (2019). Maritime Security: Building the Future Together. Indian Ocean Commission.

- Innes, A. J., & Steele, B. J. (2012). Governmentality in Global Governance. The Oxford Handbook of Governance, (November), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, H. (2010). UN reform, biopolitics, and global governmentality. International Theory (2010), 2, 50–86. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J. (2009). Governmentality of what? populations, states and international organisations. Global Society, 23(4), 413–427. [CrossRef]

- Kellerman, M. G. (2011). Somali Piracy: Causes and Consequences. Inquiries Journal / Student Pulse, 3. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=579.

- Lambach, D. (2022). The Territorialization of the Global Commons : Evidence from Ocean Governance. Politics and Governance 10(3): 41–50.

- Larner, W., & Walters, W. (2004). Globalization as governmentality. Alternatives, 29, 495–514.

- Larsson, O. L. (2019). The governmentality of network governance: Collaboration as a new facet of the liberal art of governing. Constellations, 27(1), 111–126. [CrossRef]

- Lemke, T. (2019). Foucault’s Analysis of Modern Governmentality: A Critique of Political Reason. Verso Books. London, NY.

- Löwenheim, O. (2008). Examining the State: A Foucauldian perspective on international “governance indicators.” Third World Quarterly, 29(2), 255–274. [CrossRef]

- Malpas, J. (2012). Putting space in place: Philosophical topography and relational geography. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30(2), 226–242. [CrossRef]

- Methmann, C. (2013). The sky is the limit: Global warming as global governmentality. European Journal of International Relations, 19(1), 69–91. [CrossRef]

- Midlen, A. (2021). What is the Blue Economy? A spatialised governmentality perspective. Maritime Studies, 20(4), 423–448. [CrossRef]

- Midlen, A. (2023). Enacting the blue economy in the Western Indian Ocean : A ‘ collaborative blue economy governmentality .’ Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Mohabeer, R. and Sullivan de Estrada, K. (2019). Strengthening Maritime Security in the Western Indian Ocean. Ebene, Mauritius: IOC.

- Müller-Mahn, D. asnd Everts, J (2013). Riskscapes: the spatial dimensions of risk. In The Spatial Dimension of Risk. Routledge.

- Mythen, G., & Walklate, S. (2006). Criminology and terrorism: Which thesis? Risk society or governmentality? British Journal of Criminology, 46(3), 379–398. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, I. B., & Sending, O. J. (2007). “The international” as governmentality. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 35(3), 677–701. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, I. B. and Sending, O. J. (2010). Governing the Global Polity: Practice, Mentality, Rationality. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Obura, D. et al. (2017). Reviving the Western Indian Ocean Economy: Actions for a Sustainable Future. WWF International, Gland, Switzerland. 64 pp.

- Otto, L. (2020). Introducing Maritime Security: The Sea as a Geostrategic Space. In: Otto, L. (ed). (2020). Global challenges in maritime security: an introduction. Springer Nature, Switzerland.

- Russell, S., & Frame, B. (2013). Technologies for sustainability: A governmentality perspective. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 16(1–2), 91–106. [CrossRef]

- Silver, J. J., Gray, N. J., Campbell, L. M., Fairbanks, L. W., & Gruby, R. L. (2015). Blue Economy and Competing Discourses in International Oceans Governance. Journal of Environment and Development, 24(2), 135–160. [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, K. (2008). State Failure on the High Seas: Reviewing the Somali Piracy. FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency.

- Tardy (ed.) (2014). Fighting piracy off the coast of Somalia: Lessons learned from the Contact Group. EU Institute for Security Studies, Report 20.

- https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Report_20_Piracy_off_the_coast_of_Somalia.pdf.

- UNEP (2005). The State of the Environment in Somalia A Desk Study. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

- UN and World Bank (2007). Somali joint needs assessment : productive sectors and environment cluster report (Vol. 2) (English).

- UNODC (2010). The Globalization Of Crime: a transnational organized crime threat assessment. United Nations Office On Drugs And Crime. Vienna.

- Voyer, M., Quirk, G., McIlgorm, A., & Azmi, K. (2018a). Shades of blue: what do competing interpretations of the Blue Economy mean for oceans governance? 20(5), 595–616. [CrossRef]

- Voyer, M., Schofield, C., Azmi, K., Warner, R., McIlgorm, A., & Quirk, G. (2018b). Maritime security and the Blue Economy: intersections and interdependencies in the Indian Ocean. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14(1), 28–48. [CrossRef]

- Voyer, M., & van Leeuwen, J. (2019). `Social license to operate’ in the Blue Economy. RESOURCES POLICY, 62(February), 102–113. [CrossRef]

- Wambua, P. M. (2009). Enhancing regional maritime cooperation in Africa: The planned end state. African Security Review, 18(3), 45–59. [CrossRef]

- Walker, T (2020). The Successes and Struggles of Multilateralism: African Maritime Security and Strategy. In: Otto, L. (ed). (2020). Global challenges in maritime security: an introduction. Springer Nature, Switzerland.

- World Bank (2013). The Pirates of Somalia: Ending the Threat, Rebuilding a Nation. Washington.

| 1 | Securitisation refers to a process by which security is defined by political and cultural discourses, which may encompass any of a wide array of threats from traditional military, to crime, environment, famine etc. |

| 2 | Comprising signatories to the Nairobi Convention, one of a UNEP family of regional sea conventions established initially to collaborate on conservation of marine and coastal environments: Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Madagascar, Seychelles, France (Réunion and Mayotte), Comoros, Mauritius. |

| 3 | UN Sustainable Development Goal 14, ‘Life below water’. |

| 4 | An exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is an area of the ocean where a country has exclusive rights to the use and exploration of marine resources. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea established the concept of an EEZ in 1982. It stretches from the outer limit of the territorial sea (22.224 kilometres or 12 nautical miles from the baseline) out 370.4 kilometres (or 200 nautical miles) from the coast of the state in question, except where boundaries intersect. |

| 5 |

https://www.ifc.org.sg/ifc2web/app_pages/User/commonv2/commonIndexv7.cshtml Accessed August 2023. |

| 6 | Extract from IRTA 1st December 2020, issued by CMF and EU NAVFOR. |

| 7 | Interim Guidance on Maritime Security in the Southern Red Sea and Bab al-Mandeb https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Security/Documents/Maritime%20Security%20in%20The%20Southern%20Red%20Sea%20and%20Bab%20al-Mandeb.pdf. |

| 8 | Best Management Practices 5 https://www.ics-shipping.org/publication/bmp5-hi-res-needs-further-compression-not-clear-on-date-only-one-available-is-for-a-related-file/ Accessed June 2023. |

| 9 | |

| 10 |

https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/maritime-security-transit-corridor-mstc/ Accessed August 2023. |

| 11 | Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor. |

| 12 | Maritime Security Transit Corridor. |

| 13 | |

| 14 |

https://igad.int/mase-programme-a-regional-response-to-maritime-insecurity/ Accessed August 2023. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).