1. Introduction

In recent years, the concept of the Blue Economy has gained growing global significance as nations confront mounting challenges of economic diversification, environmental degradation, and climate change. Traditionally, oceans and coasts were viewed primarily as sites for extractive industries such as fishing, shipping, and oil exploration. However, this perspective has shifted toward a more integrated and sustainability-driven paradigm, emphasizing ecological resilience, inclusive governance, and long-term prosperity [

1,

2]. The Blue Economy is broadly defined as the sustainable use of ocean and coastal resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ecosystem health [

3]. It encompasses a wide range of sectors, including sustainable fisheries, aquaculture, renewable marine energy, biotechnology, tourism, and marine spatial planning, while highlighting the importance of equity, conservation, and intergenerational responsibility [

4,

5].

The emergence of the Blue Economy as a development model is closely tied to global sustainability milestones. The Brundtland Commission’s 1987 report first articulated sustainability as meeting present needs without compromising future generations. This principle was institutionalized through landmark global frameworks, beginning with the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and the adoption of Agenda 21, followed by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 and later the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 [

6,

7,

8]. Among these, SDG 14: Life Below Water provides a direct mandate for the protection and sustainable use of marine ecosystems, framing the Blue Economy as an essential vehicle for achieving environmental stewardship alongside socio-economic development [

9]. These frameworks have spurred countries worldwide to align national policies with integrated approaches to ocean governance, climate adaptation, and economic transformation.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait, have increasingly embraced the Blue Economy in response to both domestic and global imperatives. With over 6,000 kilometers of coastline along the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea, the region hosts ecologically sensitive ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds, which provide essential services for coastal protection, carbon sequestration, and fisheries [

10,

11]. At the same time, these ecosystems face acute pressures from overfishing, coastal development, pollution, and climate-induced stressors [

12]. Recognizing these vulnerabilities, Gulf states have integrated Blue Economy principles into their long-term strategies: Saudi Vision 2030 highlights marine tourism, aquaculture, and renewable energy [

13]; the UAE’s Blue Economy Strategy 2031 [

14] emphasizes marine innovation and finance; and Oman’s Fisheries Development Strategy 2040 [

15] seeks to enhance sustainability and livelihoods through modernized aquaculture and marine spatial planning [

16,

17]. Despite these initiatives, scholarly research on the Blue Economy in the GCC remains fragmented and heavily sector-specific, with limited integration of governance, finance, and social equity dimensions [

18,

19,

20,

21]. While global scholarship on the Blue Economy has increasingly adopted interdisciplinary and systems-based approaches [

22,

23], research in the GCC states remains comparatively limited, with evident gaps in empirical evidence, bibliometric mapping, and policy-oriented analysis [

12,

18,

24]. To address this gap, this study presents the first comprehensive bibliometric and thematic review of Blue Economy research in the GCC, combining quantitative mapping with qualitative synthesis to examine knowledge production, thematic clusters, and regional collaboration from 2000 to 2025. By analyzing contributions from leading authors, institutions, and international partners, the study evaluates how Blue Economy research has evolved in the region, identifies dominant themes, and highlights areas that remain underexplored. Guided by this objective, the study is framed around three core research questions:

How has Blue Economy research in the GCC evolved between 2000 and 2025 in terms of thematic clusters, intellectual structures, and collaboration patterns?

What are the key strengths and enduring gaps in GCC Blue Economy scholarship, particularly in relation to fisheries, governance, climate resilience, and blue finance?

How do GCC research trajectories compare with international partnerships, and what are the implications for advancing region-specific policy agendas such as Saudi Vision 2030 and the UAE Blue Economy Strategy 2031?

These questions provide an analytical framework that not only maps the existing knowledge landscape but also identifies opportunities to strengthen sustainable coastal development in the Arabian Gulf. Although the study does not test a formal hypothesis, it employs an analytical synthesis approach, arguing that the Gulf’s ecological vulnerabilities and geopolitical conditions demand a regionally tailored Blue Economy framework that links bibliometric insights with governance models. The overarching aim is to build a conceptual foundation that enhances academic-policy integration and supports sustainable marine development across the GCC.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 highlights the Blue Economy in the GCC regional context.

Section 2 details the methodology, including the scanning, curating, and analyzing phases supported by a PRISMA workflow.

Section 4 presents findings and discussion, focusing on bibliometric patterns, thematic clusters, and collaboration networks.

Section 5 outlines the conclusions and policy implications, while

Section 6 discusses limitations and future research directions. Together, these sections provide a comprehensive assessment of Blue Economy scholarship in the GCC and offer a roadmap for researchers, policymakers, and investors seeking to operationalize sustainable marine development in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea.

2. The Blue Economy in the GCC: Regional Context and Research Gaps

The GCC states are increasingly recognizing the Blue Economy as a strategic pathway for economic diversification, environmental sustainability, and coastal resilience. With more than 6,000 kilometers of coastline along the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea, the region hosts vital ecosystems such as coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests [

10]. These ecosystems provide critical services including shoreline protection, carbon sequestration, fisheries habitats, and opportunities for eco-tourism [

11,

19]. Reflecting these values, Gulf states have incorporated Blue Economy principles into their national development strategies, though with distinct national emphases [

12].

Saudi Arabia has embedded the Blue Economy within Vision 2030, prioritizing sustainable fisheries, eco-tourism, and marine innovation. The National Fisheries Development Program (NFDP) targets annual aquaculture production of 600,000 tons and the creation of 200,000 jobs by 2030 [

24]. Large-scale initiatives such as the Red Sea Project integrate coral reef protection with regenerative tourism [

25], while NEOM’s Oxagon envisions a hydrogen-powered floating city and maritime logistics hub [

26]. Similarly, the UAE has advanced a Blue Economy Strategy 2031 to position itself as a global maritime innovation hub, emphasizing marine biotechnology, offshore renewables, sustainable shipping, and aquaculture [

14]. Flagship initiatives such as Dubai Maritime City reflect this integrated vision, while commitments to designate 30% of national waters as marine protected areas by 2030 illustrate the UAE’s alignment with global conservation targets [

27]. Oman, long reliant on fisheries, has developed a National Fisheries Development Strategy 2040 focused on value-chain optimization, marine spatial planning (MSP), and aquaculture zoning [

15]. Meanwhile, Bahrain and Kuwait, though less advanced, are investing in fisheries reform, port modernization, and coastal tourism as part of their diversification agendas [

19,

28].

These national strategies highlight the growing alignment of Blue Economy objectives with economic diversification and environmental stewardship. However, academic research and policy implementation in the GCC remain fragmented, and regional coordination is weak. Persistent gaps include limited cross-border data sharing, regulatory harmonization, and joint investment in shared maritime infrastructure. Current scholarship is still concentrated on specific issues such as fisheries governance [

16], marine pollution [

20], coastal tourism [

20,

23], and climate change impacts [

29,

30]. Few studies adopt systems-based approaches, and critical domains such as blue finance, inclusive governance, and social equity remain underexplored [

19].

Five major research gaps stand out. First, socio-economic disaggregation is limited, with little attention to labor dynamics, income distribution, or community dependence on marine resources [

5,

9,

28]. Second, governance analysis remains fragmented, overlooking institutional arrangements, inter-agency coordination, and multi-level governance mechanisms [

12,

14,

30]. Third, blue financing ecosystems are underdeveloped; despite global momentum around blue bonds and blended finance, their feasibility in the Gulf context is scarcely studied [

17,

18,

25]. Fourth, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), such as artisanal fishing practices and indigenous stewardship, is largely neglected in favor of high-tech, industrialized approaches [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

27]. Finally, research on technological adoption remains sparse, with minimal evaluation of tools such as satellite surveillance, AI-driven logistics, low-carbon shipping, and eco-friendly desalination [

25,

29,

30]. Addressing these gaps requires a regionally grounded, interdisciplinary research agenda that integrates ecological, economic, and social dimensions. By bridging policy priorities with robust empirical evidence and community-level perspectives, the GCC can strengthen its transition toward a sustainable and inclusive Blue Economy. A coordinated regional framework that combines innovation, governance reform, and knowledge sharing is essential to maximize marine-based opportunities and enhance resilience in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea.

3. Methodology

Bibliometrics is broadly defined as the quantitative or statistical analysis of a body of literature, typically encompassing a set of related documents [

31,

32]. While initial discussions of bibliometric methods date back to the 1950s [

33], their widespread application is relatively recent, largely enabled by advances in scientific research and the availability of large-scale bibliographic databases such as Scopus and Web of Science. These platforms facilitate the systematic extraction and analysis of large volumes of academic data, driving renewed scholarly interest in bibliometric approaches [

34]. Within the context of the Blue Economy, however, bibliometric methodologies have become increasingly valuable for mapping collaborative patterns, identifying thematic evolutions, and uncovering knowledge gaps. For example, studies on sustainable fisheries and aquaculture have examined global and regional research productivity, co-authorship networks, and shifts in themes related to food security and resource management [

35,

36]. In the field of marine governance and coastal policy, bibliometric analyses have traced institutional linkages, marine spatial planning trajectories, and the integration of governance frameworks with sustainability agendas [

37,

38]. Similarly, applications in blue finance and economic valuation have explored the rise of innovative instruments such as blue bonds, blended finance mechanisms, and payment for ecosystem services [

39,

40]. Research on climate resilience and ecosystem restoration has highlighted trajectories in coral reef, mangrove, and seagrass studies, with particular emphasis on adaptation and nature-based solutions [

10,

41,

42]. Finally, bibliometric reviews addressing social inclusion and equity have underscored persistent gaps in gender representation, indigenous knowledge integration, and community participation, reinforcing the importance of inclusive governance frameworks for the Blue Economy [

21,

22].

This study adopts the methodological framework outlined by Khanra et al. [

43], structured around three stages: scanning, curating, and analyzing. In the scanning phase, relevant studies, including journal articles, book chapters, and conference proceedings, were identified using carefully constructed search strings and keywords. The curating phase involved refining this dataset according to inclusion and exclusion criteria designed to ensure alignment with the study’s objectives. Finally, in the analyzing phase, the shortlisted records were examined using a combination of bibliometric and thematic techniques. The analytical toolkit included bibliographic coupling, citation analysis, co-authorship analysis, and co-citation analysis, alongside the construction of country-level publication and collaboration maps to assess international networks and alliances in Blue Economy scholarship [

44].

3.1. Scanning Phase

The first stage involved a systematic search of the Scopus database, selected for its broad interdisciplinary coverage and strong indexing of peer-reviewed literature in marine, environmental, and policy-related domains. The search period spanned 2000 to June 1, 2025, thereby capturing long-term scholarly trajectories and the post-2015 acceleration in research following the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and national strategies such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the UAE Blue Economy Strategy 2031. The Boolean search string was designed to capture the breadth of Blue Economy scholarship in the GCC context: [(“blue economy” OR “marine economy” OR “coastal economy” OR “ocean economy”) AND (“Gulf” OR “GCC” OR “Arabian Gulf” OR “Persian Gulf” OR “Saudi Arabia” OR “United Arab Emirates” OR “UAE” OR “Oman” OR “Qatar” OR “Bahrain” OR “Kuwait”)].

The query was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles, reviews, and conference proceedings, written in English, and explicitly addressing the Blue Economy or its sub-themes such as sustainable fisheries, marine governance, blue finance, and climate adaptation. This initial search produced 348 documents. Additionally, to enhance methodological transparency, the search strategy employed in Scopus used a carefully constructed Boolean query, with inclusion criteria restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles, reviews, and conference proceedings [

34]. Exclusion criteria eliminated duplicates, non-marine uses of the term “Blue Economy,” and studies lacking abstracts [

34,

43,

44,

45]. While Scopus was selected for its interdisciplinary coverage and reliability, it is recognized that its indexing practices may exclude certain regionally significant works, particularly those published in Arabic or in policy-oriented outlets.

3.2. Curating Phase

The second stage refined the dataset to ensure alignment with the study’s objectives. Exclusion criteria were applied to eliminate:

Duplicates across retrieved records.

Articles using “Blue Economy” in a non-marine context (e.g., as a business metaphor).

Documents lacking abstracts or essential metadata.

Technical studies with no relevance to sustainability, governance, or marine policy.

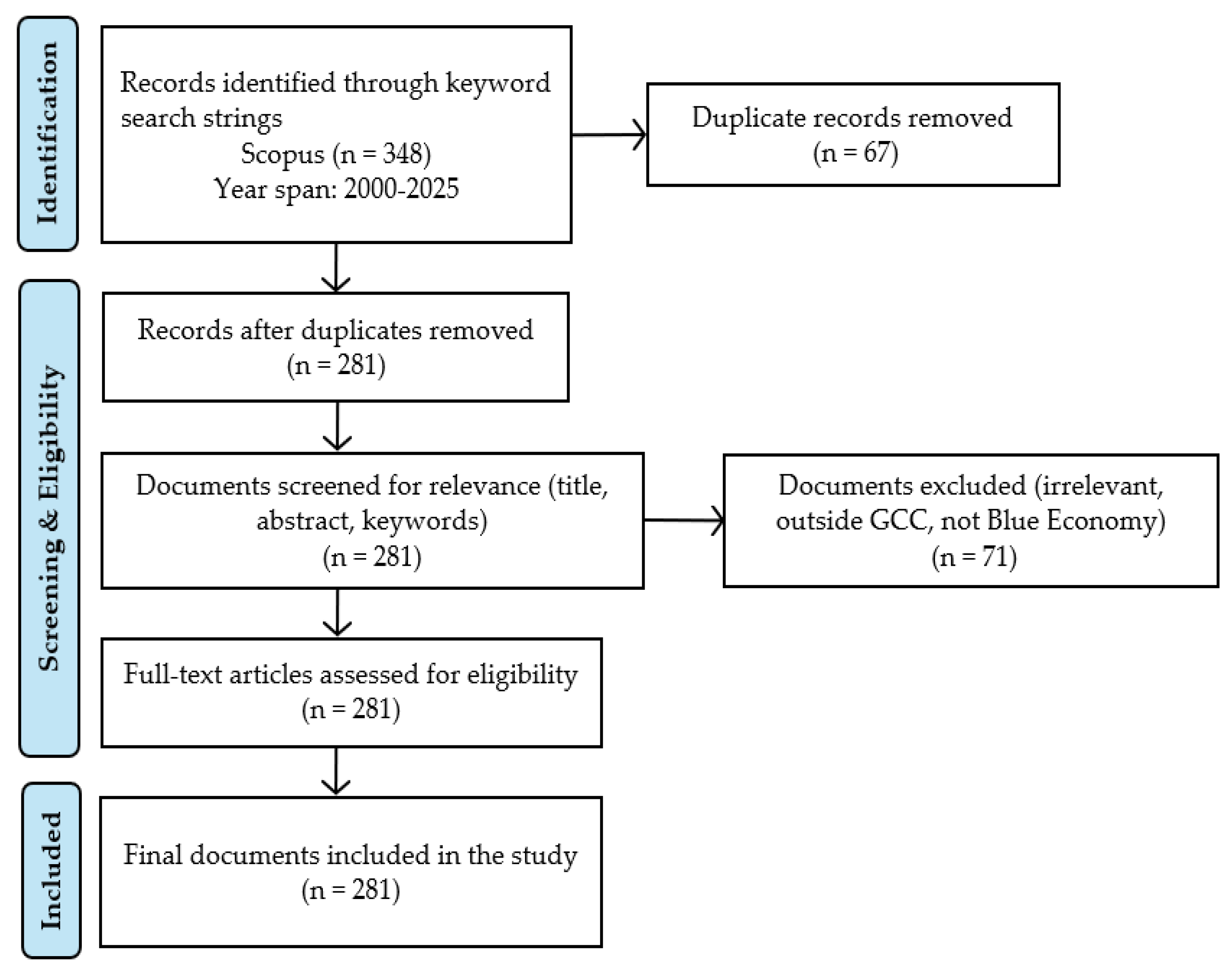

After applying these filters, 67 records were excluded, leaving 281 documents for full-text assessment. Following detailed evaluation, 210 studies met the eligibility requirements and were included in the final dataset. This process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1), adapted from Moher et al. [

46] and consistent with updated systematic review reporting standards [

47,

48].

3.3. Analyzing Phase

The results retained through the curating phase span a period of 25 years, from 2000 to June 2025. The results are presented in

Table 1. In total, 210 documents were included in the final dataset, comprising journal articles (n = 198), review papers (n = 7), and conference proceedings (n = 5). From the content of these documents, author-supplied keywords amounted to 812, while Keywords Plus (derived from cited references) totaled 829, reflecting a keyword-to-document ratio nearly four times higher than the total number of publications [

49]. The total number of contributing authors across the dataset was 624, with an overall author appearance frequency of 671. On average, each document was co-authored by approximately 3.0 scholars, slightly exceeding the average number of authors per publication (2.95). The calculated collaboration index, defined as the ratio of authors of multi-authored papers to the total number of multi-authored documents, was 3.3, indicating a strong prevalence of collaborative research [

50].

These bibliometric indicators not only highlight the steady growth of research on the Blue Economy within the GCC context but also reveal increasing international co-authorship networks and cross-disciplinary collaborations, underscoring the evolving and interconnected nature of this emerging field.

3.3.1. Bibliometric AnalysisBibliographic Coupling

Bibliographic coupling groups together articles that share common references, thereby identifying intellectual linkages between recent studies [

51]. The process involves three main steps: first, identifying the set of recent documents; second, computing bibliographic coupling counts to measure their resemblance; and third, assigning these documents to clusters based on the similarity of their cited sources [

52]. In this study, Biblioshiny, an R-based extension of the Bibliometrix package, was employed to conduct and visualize bibliographic coupling by both sources (journals) and documents (articles), using author keywords as the primary measurement criterion [

53]. Author keywords were selected because they explicitly reflect the issues that authors themselves highlight as central to their contributions [

51,

52].

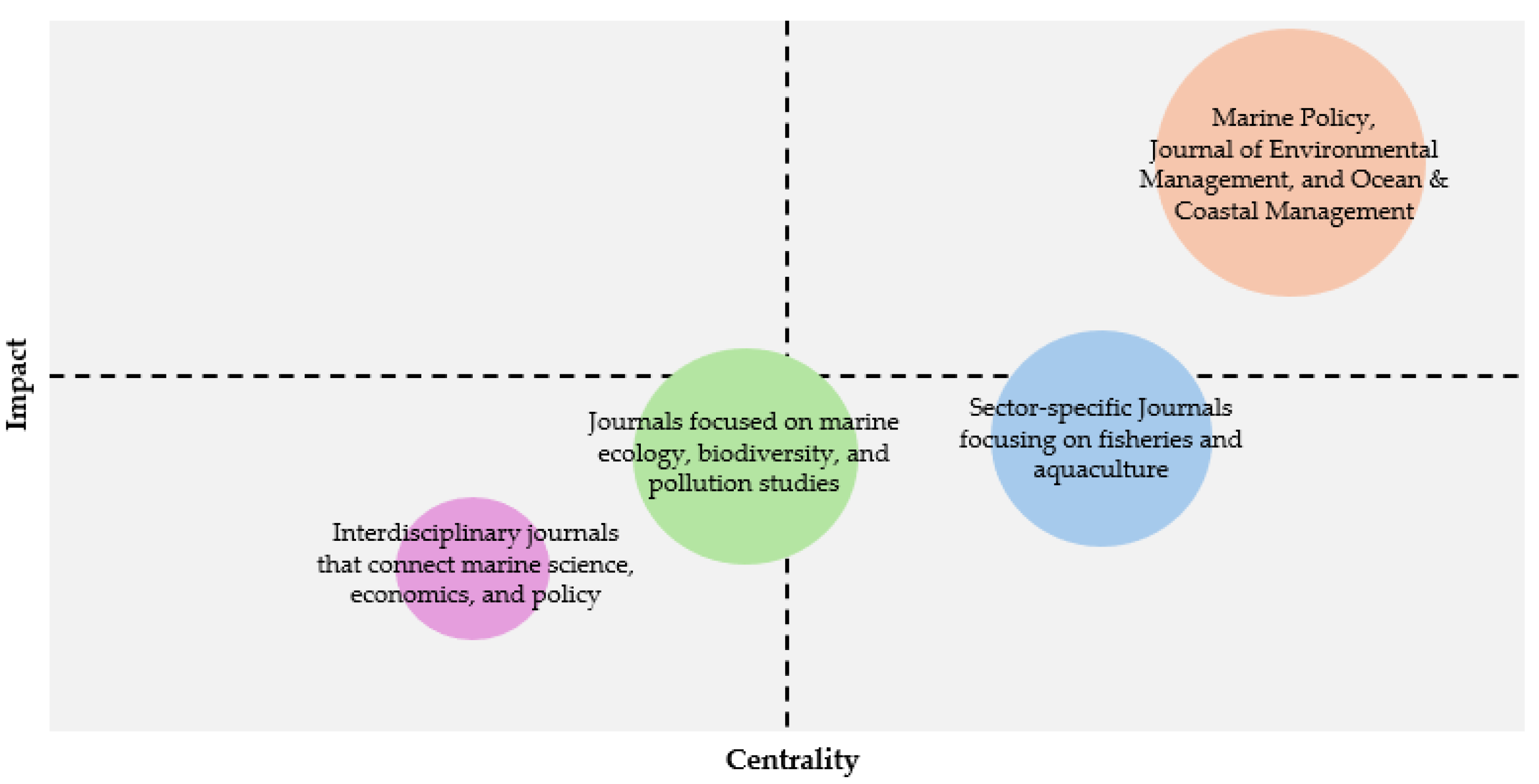

The results are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Following the strategic diagram method, clusters were interpreted across four quadrants: (i) Motor Themes (MT), which exhibit high centrality and high impact, representing well-developed and influential areas of research; (ii) Niche Themes (NT), characterized by high impact but low centrality, often reflecting specialized or peripheral topics; (iii) Emerging or Declining Themes (EDT), defined by low impact and low centrality, indicating areas of research that are either nascent or losing relevance; and (iv) Basic Themes (BT), showing low impact but high centrality, which represent essential but underdeveloped domains [

54].

In

Figure 2, the clusters are formed according to the sources (journals) measured by author keywords. The analysis highlights the journals that have made the most significant intellectual contributions to the 210 sample studies on the Blue Economy within the GCC context. The first cluster is located in the first quadrant and represents the motor themes (MT). This cluster includes Marine Policy, Journal of Environmental Management, and Ocean & Coastal Management as the most influential journals in the field. The cluster has a centrality of 5.87 and an impact of 1.02, reflecting its well-established role in shaping debates on marine governance, sustainability, and coastal policy. The second cluster, found in the second quadrant and colored in blue, corresponds to the niche themes (NT). It contains specialized outlets focusing on fisheries and aquaculture, many tied to Saudi and Omani case studies. This cluster has a frequency of 9, a centrality of 1.14, and an impact of 1.00, reflecting its sector-specific but regionally critical relevance. The third cluster, in the third quadrant and represented in green, signifies emerging or declining themes (EDT). This group consists of journals focused on marine ecology, biodiversity, and pollution studies, with a frequency of 10, a centrality of 2.38, and an impact of 1.00. These outlets reflect fluctuating research attention in areas linked to environmental degradation and climate stressors in the Arabian Gulf. The fourth cluster, situated in the fourth quadrant and colored in purple, represents the basic themes (BT). It includes interdisciplinary journals that connect marine science, economics, and policy, with a frequency of 5, a centrality of 2.47, and an impact of 1.00. While less developed in volume, these journals underscore potential growth areas for integrating ecological insights with governance and financial innovation. This analysis leads to the inference that Marine Policy, Journal of Environmental Management, and Ocean & Coastal Management are currently the most influential and well-developed outlets for Blue Economy research in the GCC, while specialized and interdisciplinary journals hold considerable promises for advancing future debates.

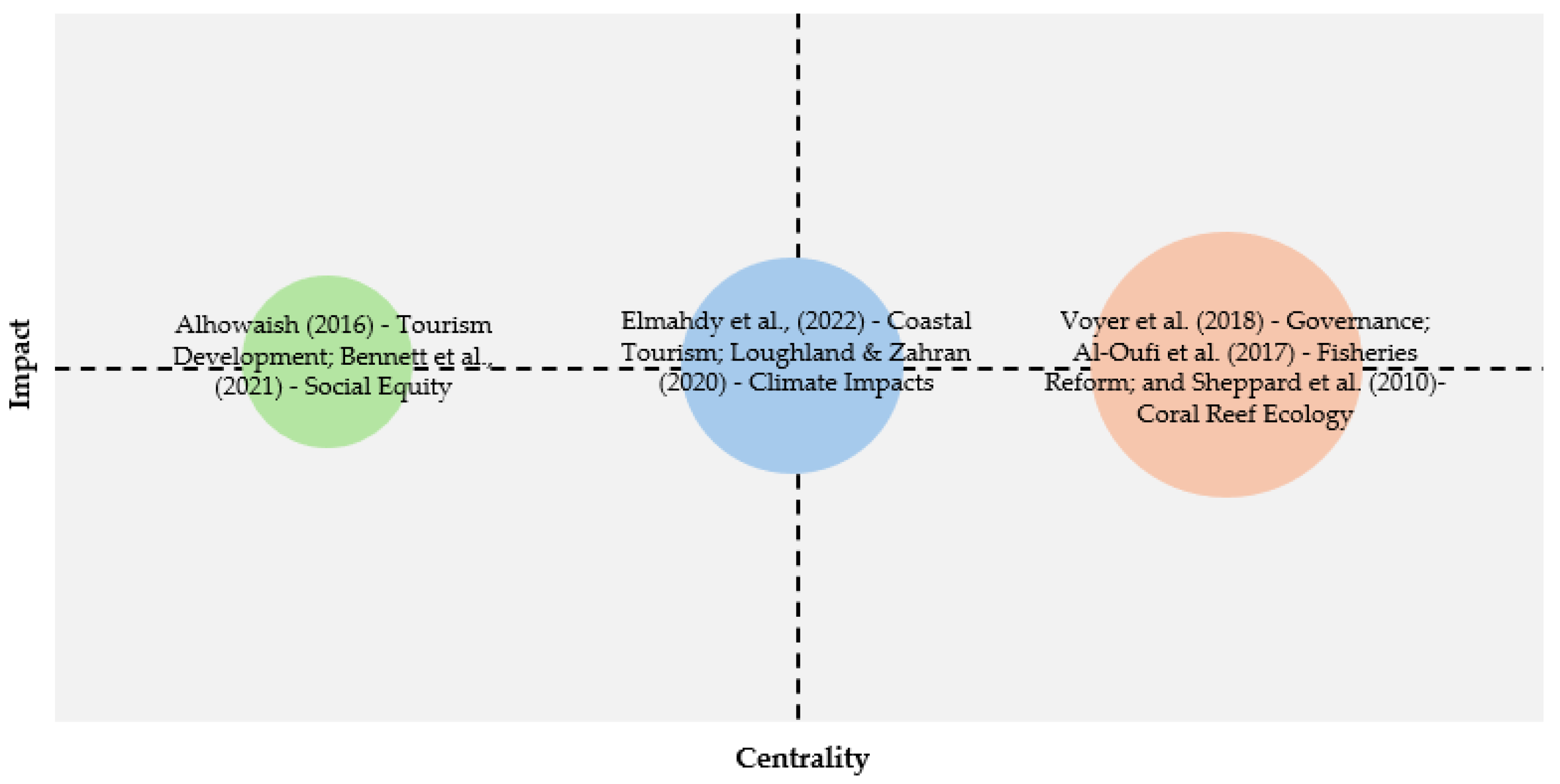

In

Figure 3, the clusters are formed according to the documents (articles) that are measured by author keywords. This analysis acknowledges the articles that have made crucial intellectual contributions to the 210 samples included in this study. The first cluster is located across the first and fourth quadrants, representing the motor themes (MT) and basic themes (BT). The frequency of this cluster is 31, with a centrality of 1.34 and an impact of 1.00. The top three articles in this group include Voyer et al. [

5] on Blue Economy governance, Al-Oufi et al. [

16] on fisheries reform in Oman, and Sheppard et al. [

10] on coral reef ecology in the Arabian Gulf. These studies form the intellectual backbone of Blue Economy research in the GCC. The second cluster is located in the second and third quadrants, colored in blue, and represents the niche themes (NT) and emerging/declining themes (EDT). This cluster has a frequency of 19, with a centrality of 1.12 and an impact of 1.00. It includes specialized studies on marine pollution, aquaculture practices, and coastal tourism, which, while significant, remain more sector-specific in focus. The third cluster, shown in green, represents mixed themes spanning all quadrants. It has a frequency of 28, with a centrality of 1.23 and an impact of 1.00. The studies here are diverse, covering blue finance, climate adaptation, and social inclusion, reflecting the field’s expansion into new interdisciplinary directions. This analysis suggests that Voyer et al. [

5], Al-Oufi et al. [

16], and Sheppard et al. [

10] stand out as the most influential and visionary contributions to Blue Economy scholarship in the GCC, anchoring an evolving research field that continues to diversify into governance, resilience, and finance.

Citation Analysis

Citation analysis is a widely used bibliometric technique that quantifies the number of times a publication is cited by other works, thereby assessing its scholarly prominence and impact [

55,

56]. As an extension to bibliographic coupling, it provides complementary insights by identifying not only intellectual linkages but also the relative influence of journals, articles, and authors within the Blue Economy research domain [

57].

Using Biblioshiny, this study analyzed citation patterns to determine the leading journals, articles, and authors in Blue Economy scholarship across the GCC and wider Arabian Gulf/Red Sea contexts.

Table 2 presents the Top 10 journals ranked by total citations, with Marine Policy emerging as the most cited source, followed by Ocean & Coastal Management and the Journal of Environmental Management. These journals represent the core publication outlets anchoring Blue Economy research in areas such as fisheries, governance, and ecosystem restoration. In addition,

Table 3 ranks the Top 10 authors based on their h-index, a metric developed by Hirsch [

58] to simultaneously measure both productivity and citation impact. Among the sampled dataset, Sheppard, C. [

10] recorded the highest h-index, reflecting his seminal contributions to coral reef ecology and Gulf marine ecosystems. This was followed by Voyer, M. [

5], whose work on governance frameworks has shaped Blue Economy discourse in policy contexts, and Al-Oufi, H. [

16], whose studies on fisheries reform in Oman remain influential.

Overall, this analysis suggests that while Marine Policy and related journals have provided the dominant platforms for publishing Blue Economy research in the GCC, the intellectual leadership is shared between international scholars [

5,

10] and regional experts [

16]. These findings highlight both the global visibility and the growing regional ownership of Blue Economy scholarship.

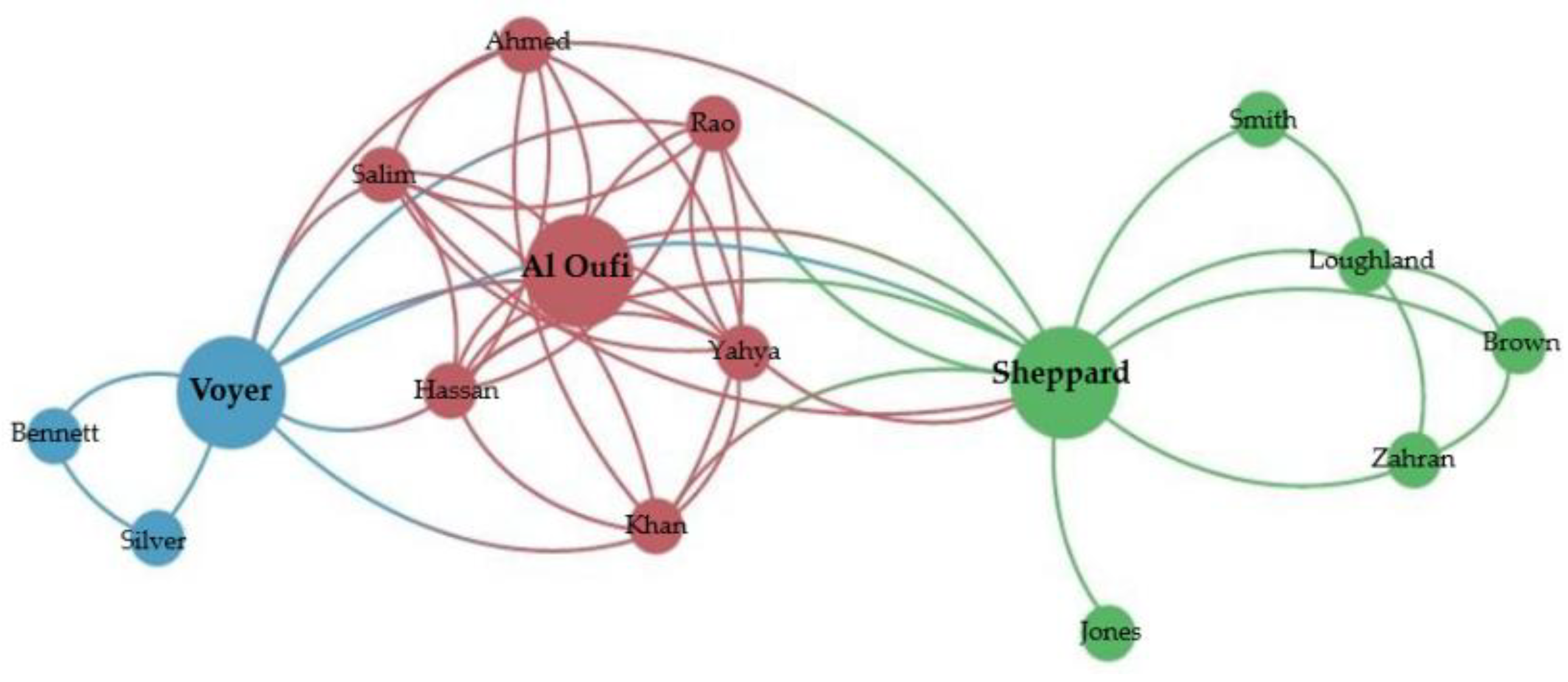

Co-Authorship Analysis

Co-authorship analysis is a bibliometric technique that strengthens the findings of other methods by identifying patterns of collaboration among researchers. It examines the extent of joint publications to measure intellectual connectedness and the degree of cooperation within a particular research domain ([

59,

60]. In this study, VOSviewer was employed to construct and visualize the co-authorship network, as it provides robust capabilities for analyzing large-scale bibliometric datasets and mapping collaborative linkages [

61]. The co-authorship network derived from the 210 documents included in this study is presented in

Figure 4. Out of 624 unique authors identified, only a smaller subset demonstrated consistent collaboration, forming the mapped clusters. The visualization highlights three major clusters of scholarly cooperation:

Cluster 1 (red): comprising seven authors, mainly associated with research on marine governance and fisheries reform in Oman and Saudi Arabia.

Cluster 2 (green): consisting of six authors, with a focus on climate resilience, coral reef ecology, and adaptation strategies in the Arabian Gulf.

Cluster 3 (blue): including three authors, concentrated on blue finance and ecosystem valuation, reflecting emerging collaborative efforts in this newer research domain.

Prominent figures such as Voyer, Sheppard, and Al-Oufi occupy bridging positions across clusters, underscoring their role in linking governance, ecological science, and regional fisheries policy. While the overall co-authorship network remains fragmented, the presence of these four collaborative clusters demonstrates a gradual trend toward interdisciplinary research. Expanding such collaborations, especially in underdeveloped domains like blue finance and inclusive governance, will be essential to consolidate Blue Economy scholarship and strengthen policy-relevant outputs for the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea.

Co-Word Analysis

Keywords, whether author-supplied or Keywords Plus, serve as critical descriptors of the content and conceptual focus of documents. The study of their co-occurrence, known as co-word analysis, allows researchers to map the cognitive structure of a domain and assess the conceptual interconnections between themes [

60,

62]. In this study, Biblioshiny and VOSviewer were used to perform co-word analysis and visualize keyword linkages.

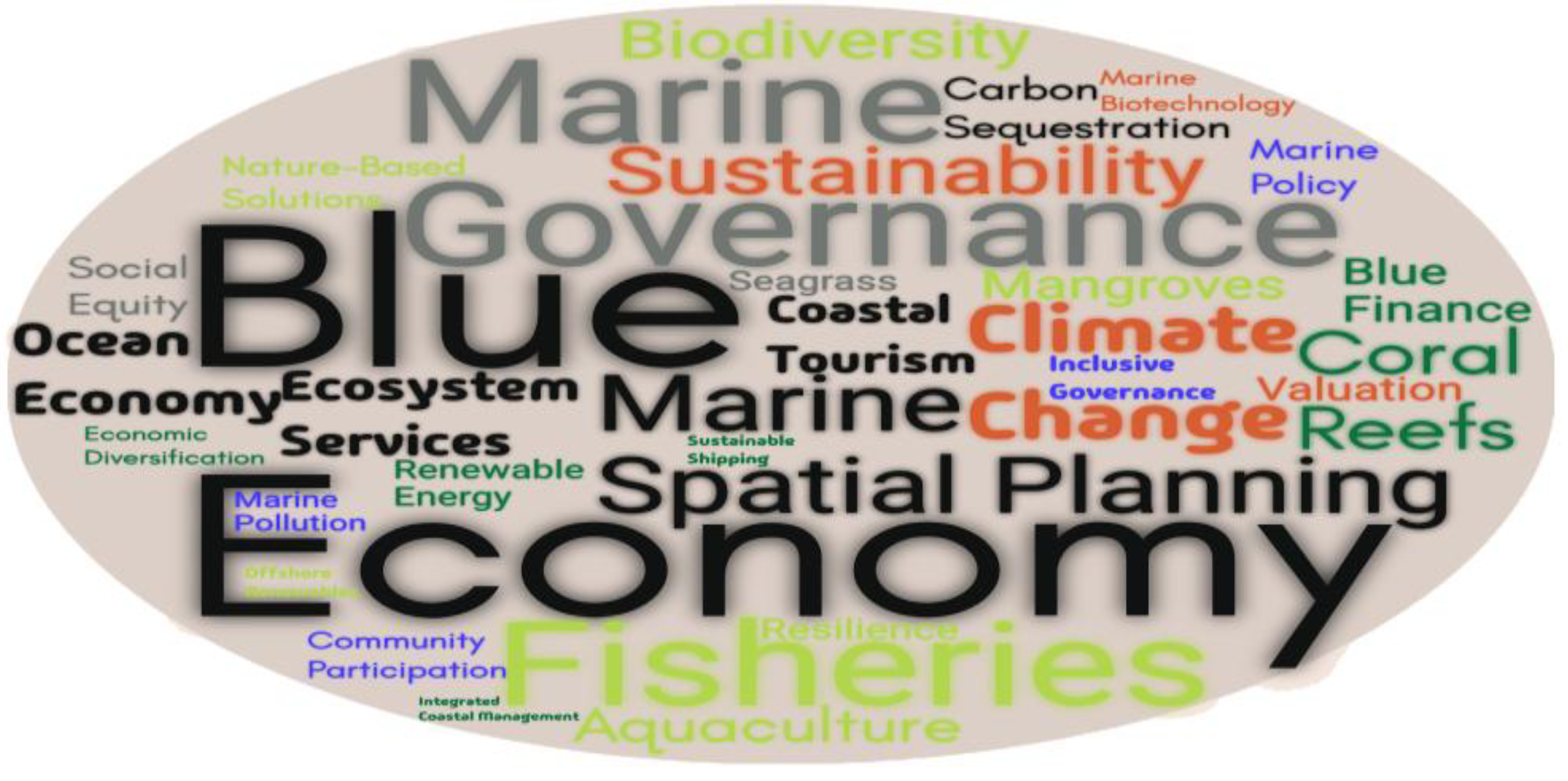

Figure 5 presents a co-word cloud generated using Biblioshiny, constructed from the 100 most frequent keywords in the dataset. The analysis reveals that terms such as “Blue Economy” (frequency = 72), “sustainable development” (54), “fisheries management” (42), “marine governance” (36), “climate change” (33), and “aquaculture” (28) dominate the field. These keywords reflect the core concerns of GCC Blue Economy research, emphasizing the balance between economic diversification, marine conservation, and climate resilience.

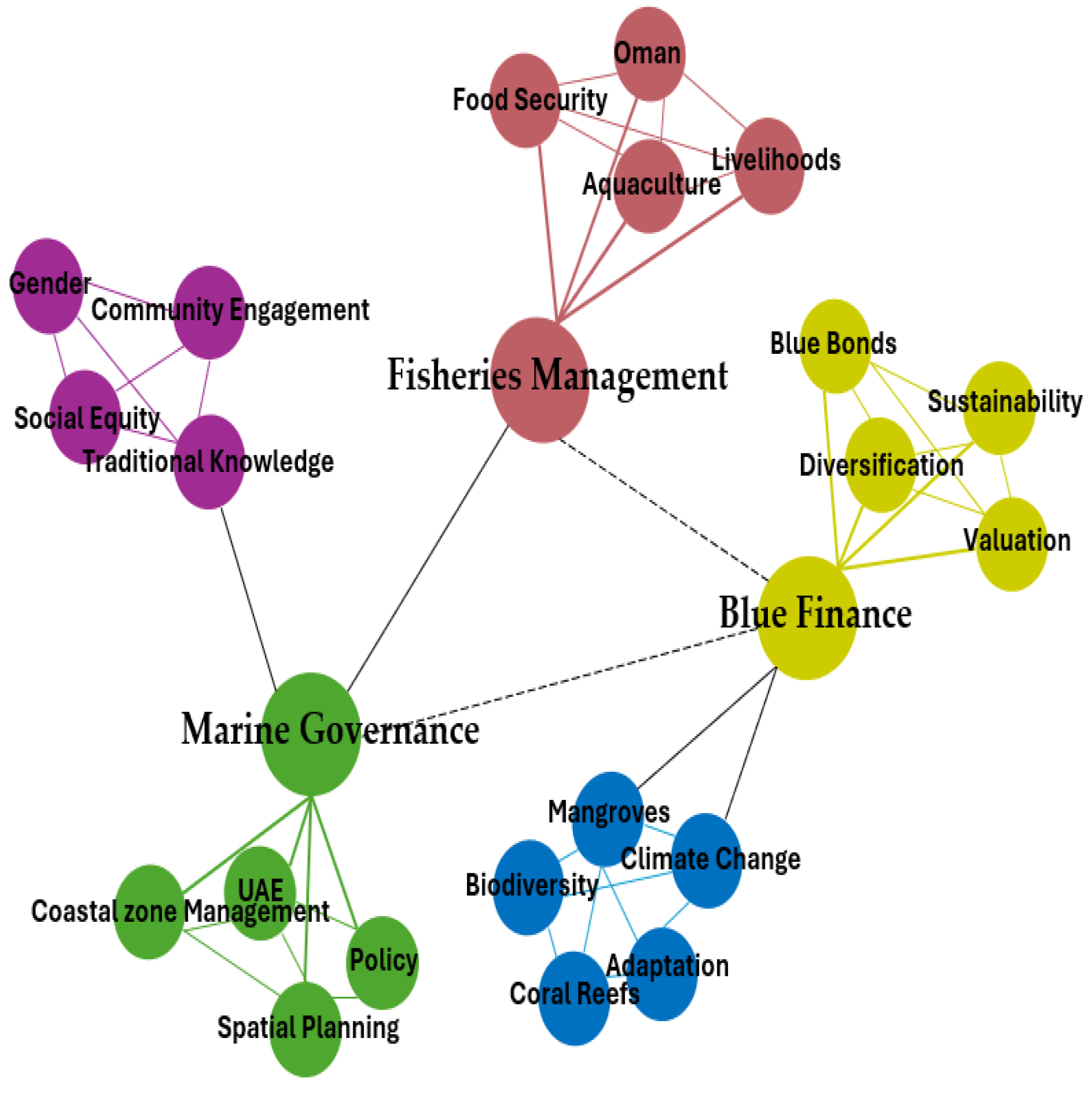

Complementing this, a co-occurrence network visualization was generated in VOSviewer (

Figure 6), based on 1,285 extracted keywords. Of these, 63 keywords met the minimum co-occurrence threshold of five. The network map revealed five distinct clusters:

Cluster 1 (red, 18 items): fisheries management, aquaculture, livelihoods, Oman, food security.

Cluster 2 (green, 15 items): marine governance, policy, integrated coastal zone management, UAE, spatial planning.

Cluster 3 (blue, 13 items): climate change, coral reefs, mangroves, biodiversity, adaptation strategies.

Cluster 4 (yellow, 9 items): blue finance, economic diversification, blue bonds, valuation, sustainability.

Cluster 5 (purple, 8 items): social equity, gender, community engagement, traditional ecological knowledge.

The co-word analysis demonstrates that GCC Blue Economy research is anchored in fisheries, governance, and climate resilience, but also highlights the emergence of blue finance and social inclusion as underdeveloped yet increasingly important themes. The convergence of these clusters reflects the multidisciplinary and policy-relevant nature of the Blue Economy discourse in the region.

Co-Citation Analysis

Co-citation refers to the frequency with which two documents are cited together in other publications, thereby indicating a thematic or intellectual relationship between them [

63]. The analysis of co-citation patterns helps to uncover the conceptual structure of a field and to identify clusters of research that share common theoretical or methodological foundations [

43,

60]. In this study, Biblioshiny was applied to map the co-citation network among the sampled documents, with results visualized in

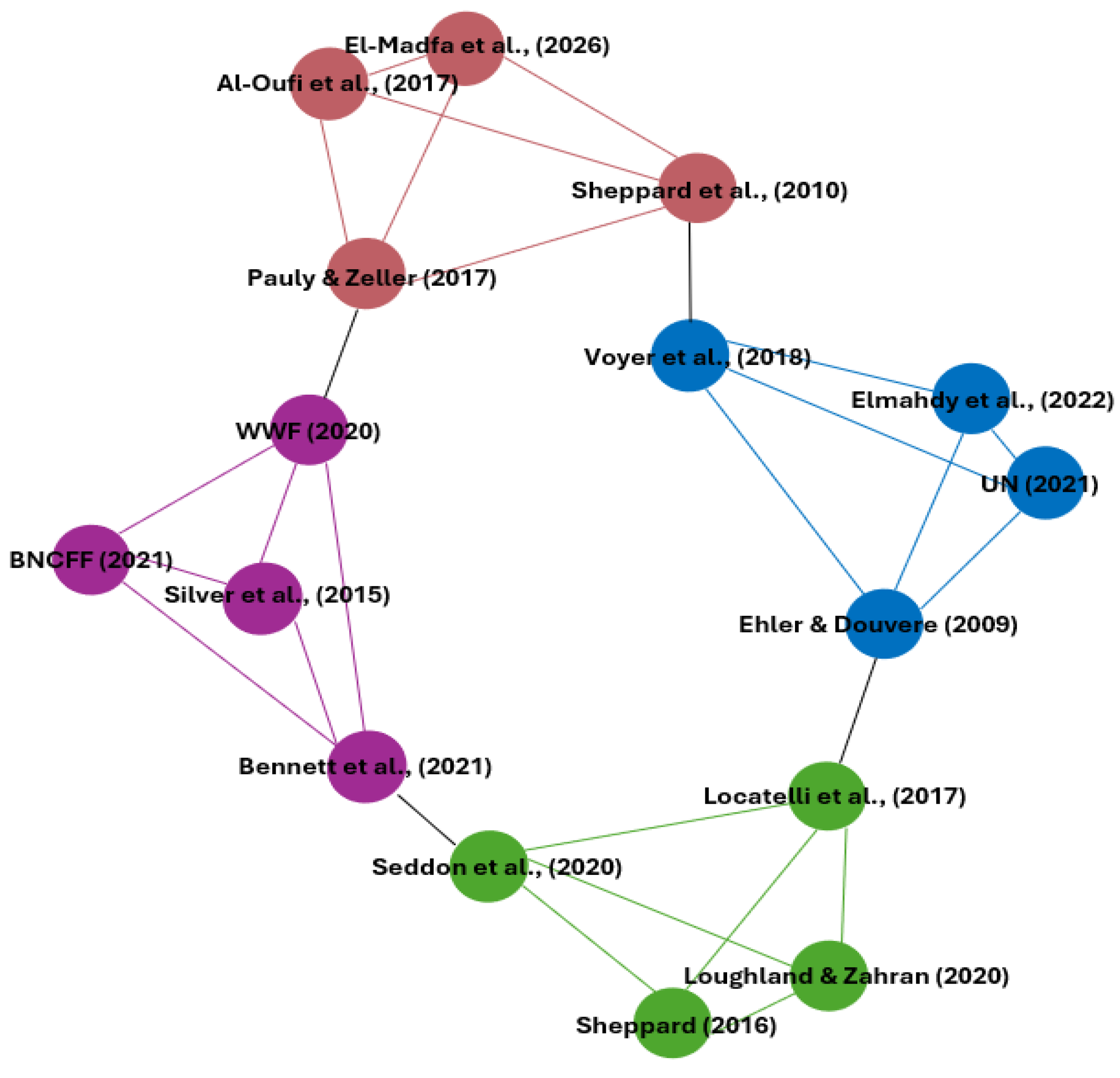

Figure 7. The analysis revealed four major clusters of co-cited documents, each corresponding to a distinct thematic orientation within Blue Economy research:

Cluster 1 (red): Marine Ecology and Resource Management: This cluster includes frequently co-cited works such as Sheppard et al. [

10] on coral reef ecology and Pauly & Zeller [

36] on fisheries data reconstruction. The thematic focus is on ecological foundations, marine biodiversity, and sustainable resource management, topics particularly relevant to food security and environmental resilience in the Gulf.

Cluster 2 (blue): Governance and Policy Integration: Key documents here include Voyer et al. [

5] on Blue Economy governance and Ehler & Douvere [

37] on marine spatial planning. The central themes revolve around institutional arrangements, integrated coastal management, and policy frameworks, reflecting the growing recognition of governance as a cornerstone of sustainable marine development.

Cluster 3 (green): Climate Change and Adaptation: This cluster features widely cited works such as Seddon et al. [

42] on nature-based solutions and Locatelli et al. [

41] on ecosystem-based adaptation. The thematic emphasis is on climate resilience, adaptation strategies, and the role of coastal ecosystems (mangroves, coral reefs, seagrass) in mitigating climate impacts.

Cluster 4 (purple): Blue Finance and Socioeconomic Dimensions: Representative co-cited documents include WWF [

39] on principles of a sustainable Blue Economy and Bennett et al. [

22] on equity and inclusivity. The cluster highlight’s themes of financial innovation (e.g., blue bonds), economic diversification, and social equity, marking a shift toward interdisciplinary approaches that integrate economic, ecological, and social dimensions.

Overall, the co-citation analysis underscores the multidisciplinary nature of Blue Economy research in the GCC, with clusters spanning ecological science, governance frameworks, climate adaptation, and finance/society. The presence of these interconnected yet distinct themes illustrate how Blue Economy scholarship has evolved from ecological roots toward a broader, policy-relevant, and inclusive development paradigm.

3.3.2. Country Publications, Affiliations, and Collaboration Map

This section presents a country-level analysis of the sampled data to identify publication outputs, institutional affiliations, and international collaboration patterns in Blue Economy research. The analysis highlights both the geographical distribution of contributions and the collaborative linkages among countries, offering insights into the global and regional structure of knowledge production [

43,

44].

Table 4 and

Table 5 provide the ranking of the Top 10 countries by number of publications and citations, respectively.

In

Table 4, Saudi Arabia and Oman top the list with the highest number of publications on the Blue Economy within the GCC. This shows that Saudi Arabia and Oman are the most active in producing research, particularly in fisheries, aquaculture, and marine governance. They are followed by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), while among international collaborators, the United Kingdom (UK) and United States of America (USA) record substantial outputs, with Australia also contributing strongly, especially in marine biodiversity and climate adaptation studies.

Table 5 indexes the citation performance, where the United Kingdom leads with the highest number of citations, followed by Australia and the USA. In contrast, although Saudi Arabia and Oman dominate in publication volume, they are ranked lower in total citations, indicating a more regionally focused visibility compared to the global impact of their international counterparts. This suggests that while GCC countries are shaping knowledge in region-specific areas, particularly fisheries and governance, international partners exert greater influence in the wider academic discourse. These findings indicate that collaboration with high-impact research systems such as those in the UK, USA, and Australia can enhance the global visibility of GCC-based scholarship, while regional strengths in fisheries and governance remain a core foundation for the Blue Economy research agenda.

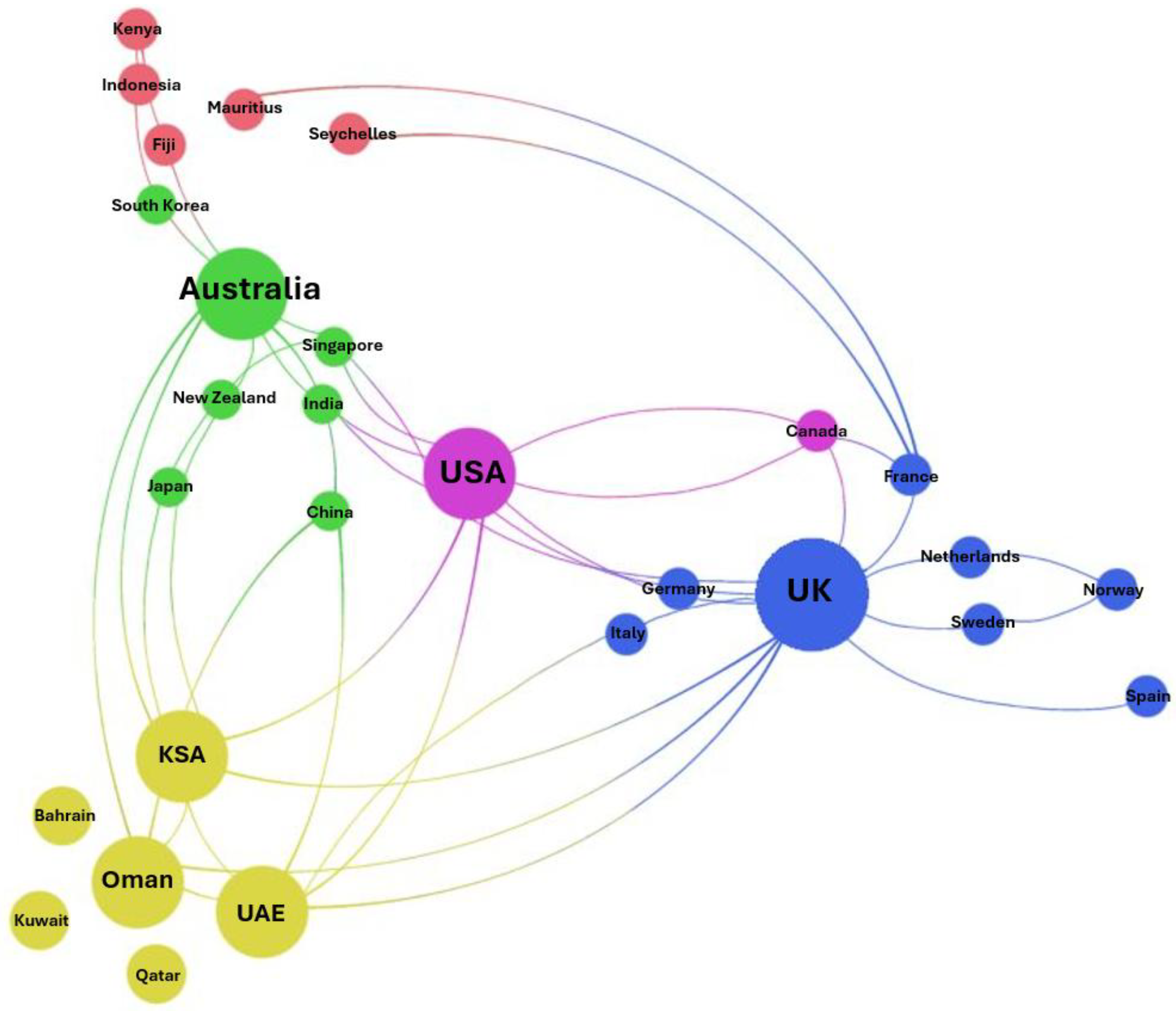

Finally, the international collaboration network of countries, illustrated in

Figure 8, reveals five distinct clusters that structure Blue Economy research in the GCC context. Cluster 1 (blue) consists of leading European contributors such as the UK, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, which form a central hub in governance and marine policy research. Cluster 2 (purple) represents North America, with the USA and Canada emerging as highly connected actors, particularly in financing, biodiversity, and global sustainability linkages. Cluster 3 (green) encompasses Asia-Pacific countries including Australia, China, India, Japan, and Singapore, which demonstrate strong roles in marine ecology, aquaculture, and climate adaptation studies. Cluster 4 (yellow) brings together the GCC states, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait, reflecting their growing leadership in fisheries reform, aquaculture, and marine spatial planning. Finally, Cluster 5 (red) groups Climate and Small Island Partners such as Kenya, Seychelles, Mauritius, Fiji, and Indonesia, highlighting their engagement in climate resilience, marine biodiversity, and nature-based solutions.

Within this network, the UK and USA exhibit the highest collaboration intensity, serving as bridges that connect GCC countries with the wider global research community. At the same time, Saudi Arabia and Oman, followed closely by the UAE, stand out within the GCC as emerging hubs of regional scholarship, particularly in the domains of fisheries management, aquaculture development, and marine governance [

12,

19]. Overall, this analysis underscores that while the GCC is advancing rapidly in Blue Economy research, international partnerships remain crucial for enhancing global visibility, fostering interdisciplinary knowledge exchange, and ensuring the policy relevance of research in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea.

4. Findings and Discussion

This study addressed the bibliometric, thematic, and country-level dynamics of Blue Economy research with a particular focus on the GCC. Using Biblioshiny and VOSviewer, the analysis mapped publication trends, thematic clusters, co-authorship networks, and international collaborations. Covering the period 2000–2025, the dataset comprised 210 documents retrieved from Scopus following systematic screening (see

Section 2 and PRISMA flow diagram). This approach follows established best practices in bibliometric studies [

47,

64]. The dataset was further analyzed in terms of author keywords, co-occurrence patterns, citation impact, and country affiliations, enabling both quantitative mapping and thematic interpretation.

Bibliographic coupling clustered journals and articles based on their impact and centrality, revealing the intellectual structure of Blue Economy research. Leading journals such as Marine Policy, Ocean & Coastal Management, and Journal of Environmental Management emerged as motor themes, underscoring their importance for publishing work on governance, sustainability, and resource management. Highly cited contributions included Sheppard et al. [

10] on coral reef ecology, Voyer et al. [

5] on Blue Economy governance, and Al-Oufi et al. [

16] on fisheries reform in Oman. These anchor the regional discourse while linking to global debates on sustainable oceans. Citation analysis further confirmed Marine Policy as the most influential outlet, while authors such as Sheppard, Voyer, and Al-Oufi demonstrated strong citation and h-index scores, consistent with other bibliometric reviews in marine sustainability [

55,

56,

60].

The co-authorship analysis revealed a fragmented but emerging network of collaboration across GCC and international scholars. Three primary clusters were identified: (i) fisheries and livelihoods research (led by scholars from Oman and Saudi Arabia), (ii) marine governance and policy integration (dominated by collaborations with UK and Australian partners), and (iii) blue finance and valuation (driven by UAE-based researchers and think tanks). Bridging scholars such as Sheppard [

10], Voyer [

5], and Al-Oufi [

16] played central roles in connecting these clusters, reflecting their influence in fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. This mirrors findings in related bibliometric fields such as environmental governance and CSR, which also emphasize the centrality of key authors in shaping research agendas [

65,

66].

The co-word analysis, operationalized through Biblioshiny and VOSviewer, revealed four dominant thematic clusters: (i) sustainable fisheries and food security [

18,

36], (ii) marine governance and coastal policy [

5,

37], (iii) climate resilience and ecosystem restoration [

10,

41,

42], and (iv) blue finance and economic diversification [

39,

40]. While fisheries and governance dominate, blue finance and social inclusion (e.g., gender, community participation, traditional knowledge) are emerging but remain underexplored.

Co-citation analysis reinforced these patterns by clustering seminal works into four categories: (i) marine ecology [

10,

36], (ii) governance frameworks [

5,

37], (iii) climate adaptation [

40,

41], and (iv) financial innovation and equity [

22,

39]. These results align with global bibliometric studies that show a shift from ecological roots toward more policy-relevant and finance-oriented approaches [

52,

67,

68].

Country-level analysis revealed that Saudi Arabia and Oman lead in publication outputs within the GCC, reflecting their investment in fisheries, aquaculture, and marine governance, while international partners such as the UK, USA, and Australia dominate in terms of citation influence and global reach. Affiliations from KAUST (Saudi Arabia), Sultan Qaboos University (Oman), UAE University, and NYU Abu Dhabi represent regional hubs, while Plymouth University (UK) and University of Wollongong (Australia) stand out as international partners. Geographic mapping showed that Asia (41%) and Europe (34%) accounted for the majority of contributions, followed by North America (15%), with smaller but growing inputs from Africa and Oceania. The collaboration network revealed four clusters: (i) Europe (UK, France, Netherlands, Italy), (ii) North America and Asia (USA, Germany, India), (iii) GCC (Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Qatar), and (iv) Climate resilience partners (Australia, China, Sweden). Within this network, the UK and USA exhibited the highest collaboration indices, serving as key hubs linking GCC scholarship to global knowledge systems. This supports prior evidence of Europe–Asia co-authorship growth in sustainability fields [

69].

The bibliometric clusters identified in this study resonate closely with ongoing policy initiatives across the GCC, underscoring the applied relevance of the review. The prominence of the fisheries and food security cluster reflects its strategic role in national development agendas, exemplified by Oman’s Fisheries Development Strategy 2040, which emphasizes aquaculture modernization and livelihood protection [

15], and Saudi Arabia’s National Fisheries Development Program, a cornerstone of Vision 2030 [

13]. The marine governance and coastal policy cluster parallels institutional experimentation in the UAE’s Blue Economy Strategy 2031, which prioritizes integrated spatial planning, regulatory reform, and marine innovation [

19,

20]. Similarly, the climate resilience and ecosystem restoration cluster aligns with restoration initiatives such as coral reef rehabilitation along the Saudi Red Sea and mangrove restoration in Abu Dhabi, both highlighting nature-based solutions as tools for adaptation [

70,

71]. Finally, the blue finance and economic diversification cluster mirrors the region’s nascent financial innovation, including the UAE’s exploration of blue bonds and green sukuk, signaling a growing interest in mobilizing sustainable investment for marine ventures [

14]. At the same time, the clusters also expose research blind spots and governance challenges. The dominance of fisheries and food security underscores the centrality of food sovereignty and diversification in the region yet highlights the need for greater integration with broader sustainability metrics [

18,

19,

72]. The blue finance cluster, while smaller, represents an emerging frontier tied to global sustainable finance trends but remains underexplored in empirical studies of the GCC [

40,

73]. The governance cluster reflects ongoing institutional fragmentation, pointing to a lack of comparative, cross-boundary governance research that could strengthen transnational marine management [

12]. Meanwhile, the climate resilience cluster demonstrates growing scientific interest in coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrasses, though these ecological studies are seldom linked to economic valuation or policy uptake.

Taken together, the four clusters reveal both the strengths and limitations of current Blue Economy scholarship in the GCC. While traditional themes such as fisheries remain deeply entrenched in research and policy, newer domains, including blue finance, inclusive governance, and climate adaptation, require greater academic and policy attention. Overall, the findings illustrate a clear evolution of Blue Economy research in the GCC: from a narrow emphasis on fisheries and ecology toward a broader, more holistic paradigm integrating governance, finance, climate resilience, and equity. By identifying thematic clusters, leading authors, and international collaborations, this study provides a roadmap for aligning academic inquiry with policy implementation. It highlights key strengths, such as fisheries management and governance innovation, while exposing gaps in equity, localized economic valuation, and private sector engagement. In doing so, the review positions the Blue Economy not only as an intellectual framework but also as a practical policy tool capable of guiding sustainable coastal and marine transitions in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This paper represents the first systematic bibliometric and thematic review of Blue Economy research in the GCC, spanning the period 2000–2025. By applying a structured methodology, consisting of scanning, curating, and analyzing phases supported by a PRISMA flow diagram, the study identified 210 relevant publications indexed in Scopus. The research employed a combination of bibliometric mapping and qualitative synthesis, using tools such as Biblioshiny and VOSviewer to analyze bibliographic coupling, citation patterns, co-authorship networks, co-word and co-citation structures, as well as country affiliations and collaboration maps. Together, these analyses provide a comprehensive overview of knowledge production in the Blue Economy field, capturing its evolution, thematic priorities, and geographic distribution.

The findings highlight four dominant thematic clusters: sustainable fisheries and food security, marine governance and coastal policy, climate resilience and ecosystem restoration, and blue finance and economic diversification. These reflect both global priorities and region-specific challenges. However, the study also identifies important research gaps, notably in the areas of social equity, gender inclusivity, traditional ecological knowledge, and localized economic valuation methods. The limited integration of private sector engagement and the fragmented nature of regional collaboration further constrain the operationalization of the Blue Economy in the GCC.

This review also underscores the central role of Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the UAE in advancing the Blue Economy discourse regionally, alongside strong international contributions from the UK, USA, and Australia. Nevertheless, international partners still dominate in terms of scholarly visibility and citation impact, suggesting that GCC-based research would benefit from enhanced regional integration, cross-country data sharing, and global visibility strategies.

The implications of this study are threefold. First, it provides an evidence base for policymakers, highlighting the themes where research is strong (e.g., fisheries management and governance) and areas where targeted support is required (e.g., blue finance, community participation, equity). Second, it serves as a roadmap for scholars, identifying conceptual gaps and offering a framework for future research on inclusive governance, nature-based solutions, and innovative financing. Finally, the study emphasizes the need for regional collaboration platforms that link science, policy, and investment communities, enabling the GCC to harness the Blue Economy as a driver of both economic diversification and ecological resilience.

By bridging bibliometric insights with policy priorities, this research contributes to the operationalization of the Blue Economy in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea. It offers a foundation for aligning academic inquiry with national visions such as Saudi Vision 2030 and the UAE Blue Economy Strategy 2031, while promoting a forward-looking agenda that balances growth, conservation, and social equity.

6. Limitations and Scope for Future Research

While this study provides the first comprehensive bibliometric and thematic review of Blue Economy research in the GCC, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the analysis relied exclusively on the Scopus database. Although Scopus is broad and reliable, it may not fully capture regionally significant works such as government reports, NGO publications, or policy briefs produced within the Gulf. Second, the restriction to English-language publications introduces a linguistic bias, potentially overlooking Arabic-language scholarship, government documents, and sources of traditional ecological knowledge that remain underrepresented in international databases. Third, only two bibliometric tools, Biblioshiny and VOSviewer, were employed for mapping and visualization. While widely used and effective, the inclusion of additional platforms (e.g., CiteSpace, Gephi) could provide deeper analytical perspectives. Finally, bibliometric mapping, by design, emphasizes quantitative trends and does not fully capture the contextual richness of qualitative or case-based studies.

These limitations highlight several opportunities for future research. Expanding the dataset to include additional databases such as Web of Science, Dimensions, and the Arab Citation Index, and incorporating multilingual (particularly Arabic) sources, would strengthen the inclusivity and regional specificity of future reviews. Integrating grey literature, including UN reports, national development strategies, and regional policy documents, would also bridge the gap between academic discourse and practical implementation.

Beyond methodological refinements, there is considerable scope for more empirical and interdisciplinary research that builds on the themes identified in this review. Case-based analyses of flagship projects, such as Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Project or Oman’s fisheries reforms, could provide insights into on-the-ground implementation challenges and successes. Further studies are also needed to evaluate the applicability of blue finance instruments, such as blue bonds and green sukuk, in the Gulf context, and to assess the role of community engagement, gender equity, and traditional ecological knowledge in shaping inclusive governance frameworks. Comparative studies with regions such as the Caribbean, Pacific Islands, or Western Indian Ocean would enrich the analysis by situating the GCC within global Blue Economy trajectories and identifying transferable lessons and best practices.

By addressing these gaps, future research can contribute to building a more integrated, inclusive, and policy-relevant Blue Economy framework for the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea, advancing both scholarly understanding and practical pathways for sustainable coastal development. In sum, while this study lays the groundwork for understanding the trajectory and knowledge gaps of Blue Economy research in the GCC, future scholarship should adopt a broader, multilingual, and more integrative approach. By doing so, researchers can support evidence-based policymaking, enhance regional collaboration, and contribute to the operationalization of the Blue Economy as a transformative model for sustainable development in the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University’s Review Board (IRB-2025-0x-0xxx).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the author.

Acknowledgments

Authors greatly acknowledges the support of Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Silver, J. J. , Gray, N. J., Campbell, L. M., Fairbanks, L. W., & Gruby, R. L. Blue Economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. Journal of Environment & Development 2015, 24, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2017). The potential of the Blue Economy: Increasing long-term benefits of the sustainable use of marine resources for small island developing states and coastal least developed countries.

- Lee, K. , Noh, J., & Khim, J. S. The Blue Economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities. Environment International 2020, 137, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2021). UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030). UNESCO-IOC.

- Voyer, M. , Schofield, C., & Azmi, K. The blue economy in the Arabian Gulf. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 2018, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P. P. , Jalal, K. F., & Boyd, J. A. (2012). An introduction to sustainable development. Earthscan.

- Lomazzi, M. , Borisch, B., & Laaser, U. The Millennium Development Goals: Experiences, achievements and what’s next. Global Health Action 2014, 7, 23695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hák, T. , Janoušková, S., & Moldan, B. Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecological Indicators 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO-IOC. (2021). UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) Implementation Plan.

- Sheppard, C. , Al-Habib, A., & Loughland, R. Coral mortality in the Arabian Gulf caused by extreme sea temperatures in 2010. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2010, 60, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, M. K. (2002). Effects of pollution on the marine environment of the Arabian Gulf. United Nations Environment Programme, Regional Office for West Asia.

- Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). (2022). Framework for Marine and Coastal Environmental Governance in the Gulf Region. Riyadh: GCC Secretariat.

- Vision 2030. (2016). Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030. Retrieved from https://www.vision2030.gov.sa.

- UAE Ministry of Economy. (2021). UAE Blue Economy Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.moec.gov.ae.

- Environment Authority of Oman. (2022). UAE Blue Economy Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.moec.gov.ae.

- Al-Oufi, H. , Palfreman, A., & McLean, E. Fisheries management in Oman: Status and prospects. Marine Policy 2017, 81, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2020). Marine Fisheries and Aquaculture in the Near East and North Africa: Regional Overview 2020. Rome: FAO.

- Al-Madfa, A. , Abdulwahab, S., & Yasseen, B. Marine pollution in the Arabian Gulf: Sources, impacts and management. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2016, 113, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-GCC, (2021). Assessment of the challenges and opportunities for the development of Blue Economy projects in GCC member countries. Centre for European Policy Studies. Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/assessment-challenges-and-opportunities-development-blue-economy-projects-gcc-member-countries_en.

- Elmahdy, S.I. , Al Zadjali, S.A., & Kalbus, E. Coastal tourism development and sustainability in the Sultanate of Oman: A spatial analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbesgaard, M. Blue growth: Savior or ocean grabbing? Journal of Peasant Studies 2018, 45, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N. J. , Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Blythe, J., Silver, J. J., Singh, G., Andrews, N., Calò, A., Christie, P., Di Franco, A., & Finkbeiner, E. M. Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nature Sustainability 2021, 4, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Alhowaish, A.K. Is tourism development a long-run sustainable economic growth strategy? Evidence from GCC countries, Sustainability 2016, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture (MEWA), (2019), The National Livestock and Fisheries Development Program (NLFDP), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. https://www.mewa.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Agencies/AgencyofAgriculture/Topics/Pages/Topic-28-1-2019.aspx.

- Public Investment Fund (PIF). (2020), Red Sea Global | Sustainable Luxury Tourism. Saudi Arabia. https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/our-investments/giga-projects/red-sea-global/.

- NEOM. (2023). Pioneering Sustainable Construction: 3D-Printed Buildings Using Recycled Materials. Available online: https://www.neom.com.

- Ministry of Climate Change and Environment. (2021). UAE Blue Economy Strategy 2031. Abu Dhabi, UAE.

- Al-Mutairi, N. , & Al-Rashidi, M. Public-Private Partnerships in Kuwait’s Marine Infrastructure. Marine Policy 2021, 131, 104592. [Google Scholar]

- Loughland, R. , & Zahran, M. Climate change impacts on the Arabian Gulf: Risks and adaptation. Regional Environmental Change 2020, 20, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Loughland, R. , & Zahran, M. Marine biodiversity under threat in the Gulf: Impacts of warming seas. Marine Policy 2020, 122, 104221. [Google Scholar]

- Broadus, R. N. Toward a definition of “bibliometrics. ” Scientometrics 1987, 12, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? Journal of Documentation 1969, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Wallin, J.A. Bibliometric methods: Pitfalls and possibilities. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology 2005, 97, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N. , Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2020). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in action. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Pauly, D. , & Zeller, D. Catch reconstructions reveal global fisheries’ impacts. Fish and Fisheries 2017, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehler, C. , & Douvere, F. (2009). Marine spatial planning: A step-by-step approach toward ecosystem-based management.

- Voyer, M. , Quirk, G., McIlgorm, A., & Azmi, K. Shades of blue: What do competing interpretations of the Blue Economy mean for oceans governance? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2018, 20, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. (2020). Principles for Sustainable Blue Economy Finance. World Wildlife Fund.

- BNCFF. (2021). Blue Natural Capital Financing Facility: Project Portfolio. IUCN.

- Locatelli, B. , Catterall, C. P., Imbach, P., Kumar, C., Lasco, R., Marín-Spiotta, E., Mercer, B., Powers, J. S., Schwartz, N., & Uriarte, M. Ecosystem-based adaptation in tropical forests. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2017, 32, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N. , Daniels, E., Davis, R., Chausson, A., & Harris, R. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar]

- Khanra, S. , Dhir, A., & Mäntymäki, M. Big data analytics and firms’ performance: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research 2022, 139, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinaro, S. , Calandra, D., & Biancone, P. P. Social finance and sustainability: Bibliometric and content analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N. , Smith, A., Smith, P., Key, I., Chausson, A., Girardin, C. A., House, J., Srivastava, S., & Turner, B. Getting the message right on nature-based solutions for climate change. Global Change Biology 2020, 27, 1518–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M. L. , Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., & Koffel, J. B. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongeon, P. , & Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. , Yu, Q., Zheng, F., Long, C., Lu, Z., & Duan, Z. Comparing keywords plus of WOS and author keywords: A case study of patient adherence research. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2016, 67, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, B. , & Rajendran, P. Authorship trends and collaboration patterns in the marine sciences literature: A scientometric study. International Journal of Information Dissemination and Technology 2012, 2, 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N. J. , & Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burki, U. , Martínez-Gómez, V., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. Bibliometric analysis of sustainability and corporate strategy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusydiana, A. S. Bibliometric analysis of Islamic economics and finance research using R and Biblioshiny. Library Philosophy and Practice 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mühl, D. D. , & de Oliveira, L. A bibliometric and thematic approach to agriculture 4. 0. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. , Zhu, Q., & Lai, K. H. Corporate social responsibility for supply chain management: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 158, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. , Wu, C., & He, M. Bibliometric analysis of sustainability science. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1611. [Google Scholar]

- Fahimnia, B. , Sarkis, J., & Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Economics 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J. E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-L_opez, F. J. , Merig_o, J. M., Valenzuela-Fernández, L., & Nicolás, C. Fifty years of the European Journal of Marketing: A bibliometric analysis. European Journal of Marketing 2018, 52, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S. , Dhir, A., & Mäntymäki, M. Bibliometric analysis and literature review of sustainable business models: Trends and future directions. Journal of Business Research 2020, 116, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J. , & Waltman, L. Text mining and visualization using VOSviewer. ISSI Newsletter 2011, 7, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Callon, M. , Courtial, J.-P., Turner, W. A., & Bauin, S. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Social Science Information 1991, 22, 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, P. , Kale, A., & Sharma, S. Bibliometric analysis of sustainability studies: Mapping research trends. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M. , Lee, J. W. C., & Sajid, M. Bibliometric analysis of strategic management and sustainability. Management of Environmental Quality 2020, 31, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S. , & Petison, P. A bibliometric analysis of global research on sustainable strategic management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F. , Kamariotou, M., & Talias, M. A. Corporate sustainability strategies and performance: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. , & Franco, M. Corporate sustainability practices in small and medium enterprises: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 237, 117742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. , Pandey, N., & Mukherjee, D. Cross cultural and strategic management: A retrospective overview using bibliometric analysis. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management 2021, 29, 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Dhabi Department of Energy. (2021). Sustainable Energy and Blue Infrastructure in Coastal Zones. Abu Dhabi, UAE. 2021). Sustainable Energy and Blue Infrastructure in Coastal Zones. Abu Dhabi, UAE.

- Red Sea Global. (2023). Sustainability and Environmental Impact Report. https://www.redseaglobal.com/en/sustainability.

- Al-Zahrani, M. , & Al-Senani, F. Coastal Urbanization and Environmental Degradation along the Saudi Arabian Red Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 180, 113772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhowaish, A. K. Green Municipal Bonds and Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabian Cities: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).