1. Introduction

The Robot Operating System (ROS, aka ROS 1) emerged in 2009 as the de facto standard ecosystem for developing robotics applications, including mobile robots, robotic arms, unmanned aerial systems, self-driving cars, quadruped robots, and space robots [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. ROS provides access to several open-source libraries, facilitating faster development of robotic systems and applications. Examples include gmapping from OpenSLAM [

4], Google Cartographer for SLAM [

6], OpenCV for image processing [

7], and the Point Cloud Library for 3D perception [

8]. Additionally, ROS abstracts low-level hardware interactions, allowing developers to focus on high-level robotics applications rather than dealing with complex hardware-specific implementations.

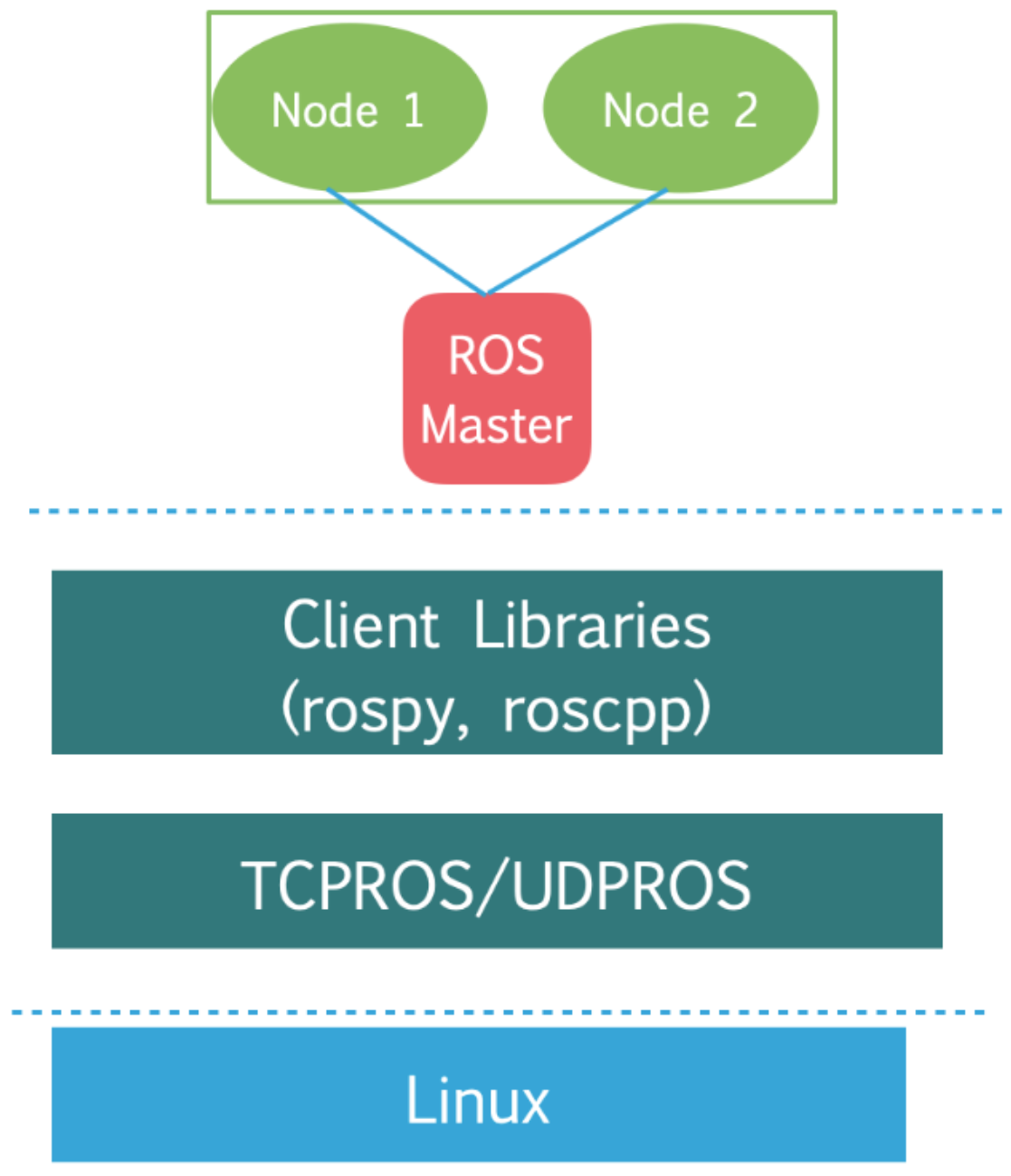

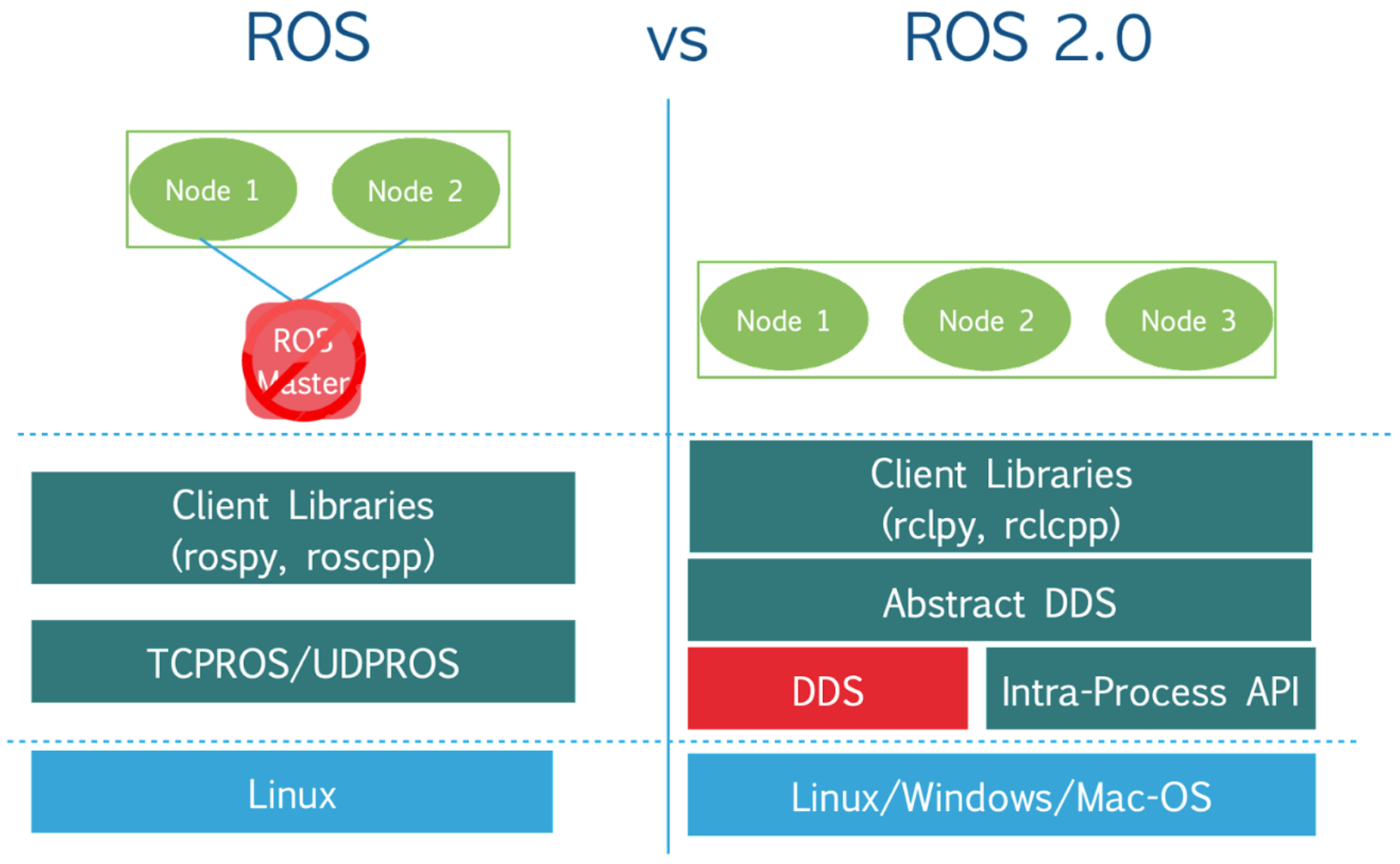

Despite its success, ROS 1 exhibits several limitations, including: (a) a single point of failure with the ROS Master Node, limiting scalability; (b) lack of built-in multi-robot support, as ROS was initially designed for single-robot applications; and (c) absence of real-time guarantees or Quality of Service (QoS) support, raising concerns about its reliability in safety-critical applications [

1]. In response, the Open Source Robotics Foundation (OSRF) initiated the development of ROS 2 to address these issues.

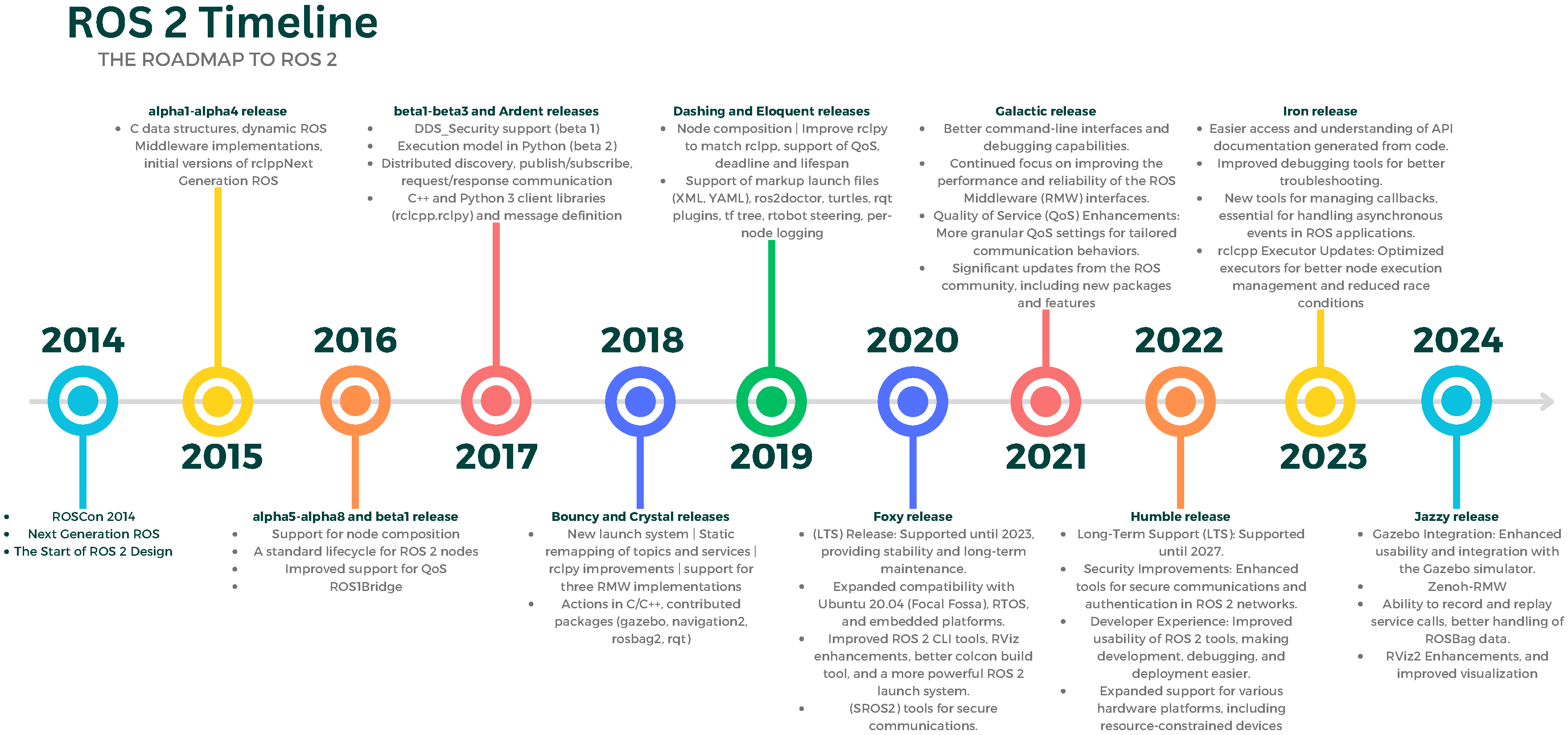

The first official ROS 2 release (Ardent Apalone) was launched in December 2017, with incremental improvements leading to feature parity with ROS 1 by 2023 as indicated in

Figure 1. However, despite these advancements, ROS 2 adoption has been slower than expected due to factors such as migration complexity, incomplete documentation, and industry hesitation in transitioning from ROS 1. While ROS 2 is expected to fully replace ROS 1 after the end-of-life (EOL) of ROS Noetic (

Figure 1 shows the road map to ROS 2 until the Jazzy distribution release.), the transition raises critical questions about its adoption, technical maturity, and real-world impact across different industries.

1.1. Research Questions and Objectives

While multiple reviews have explored specific subsystems of ROS 2—such as middleware, security, and real-time scheduling—there is currently no comprehensive survey that critically examines both the technical advancements and the practical adoption barriers of ROS 2. Additionally, research on the real-world use cases of ROS 2 across industries remains fragmented. To bridge this gap, this survey systematically investigates ROS 2’s technical foundations, adoption trends, and existing challenges by addressing the following key research questions:

- 1.

How does ROS 2 improve upon ROS 1 in terms of architecture, middleware efficiency, real-time performance, and security, and what are its current limitations?: This question critically examines DDS-based communication, real-time execution, security features, and middleware efficiency, identifying both strengths and bottlenecks, and is addressed in the part of this survey that presents a background coverage on ROS1 and ROS2.

- 2.

What are the key trends, challenges, and solutions in adopting ROS 2 across various academic research and industries, including autonomous vehicles, healthcare, agriculture, logistics, and industrial automation?: This question explores how ROS 2 is deployed in real-world applications, analyzing success stories, industry adoption barriers, and interoperability concerns.

- 3.

What are the key technical, industrial, and organizational challenges hindering a faster widespread adoption of ROS 2, and how can they be addressed?: This question investigates barriers such as middleware complexity, migration difficulties from ROS 1, lack of standardized industry support, and real-time performance concerns, while identifying potential solutions to accelerate adoption.

1.2. Methodology

To systematically examine the advancements and challenges of ROS 2, this survey follows a structured methodology grounded in systematic review principles. The research is guided by three key questions: (1) How does ROS 2 improve upon ROS 1 in architecture, middleware efficiency, real-time performance, and security, and what are its limitations? (2) What are the key trends, challenges, and solutions in adopting ROS 2 across industries such as autonomous vehicles, healthcare, and logistics? (3) What technical, industrial, and organizational factors hinder its widespread adoption, and how can they be addressed?

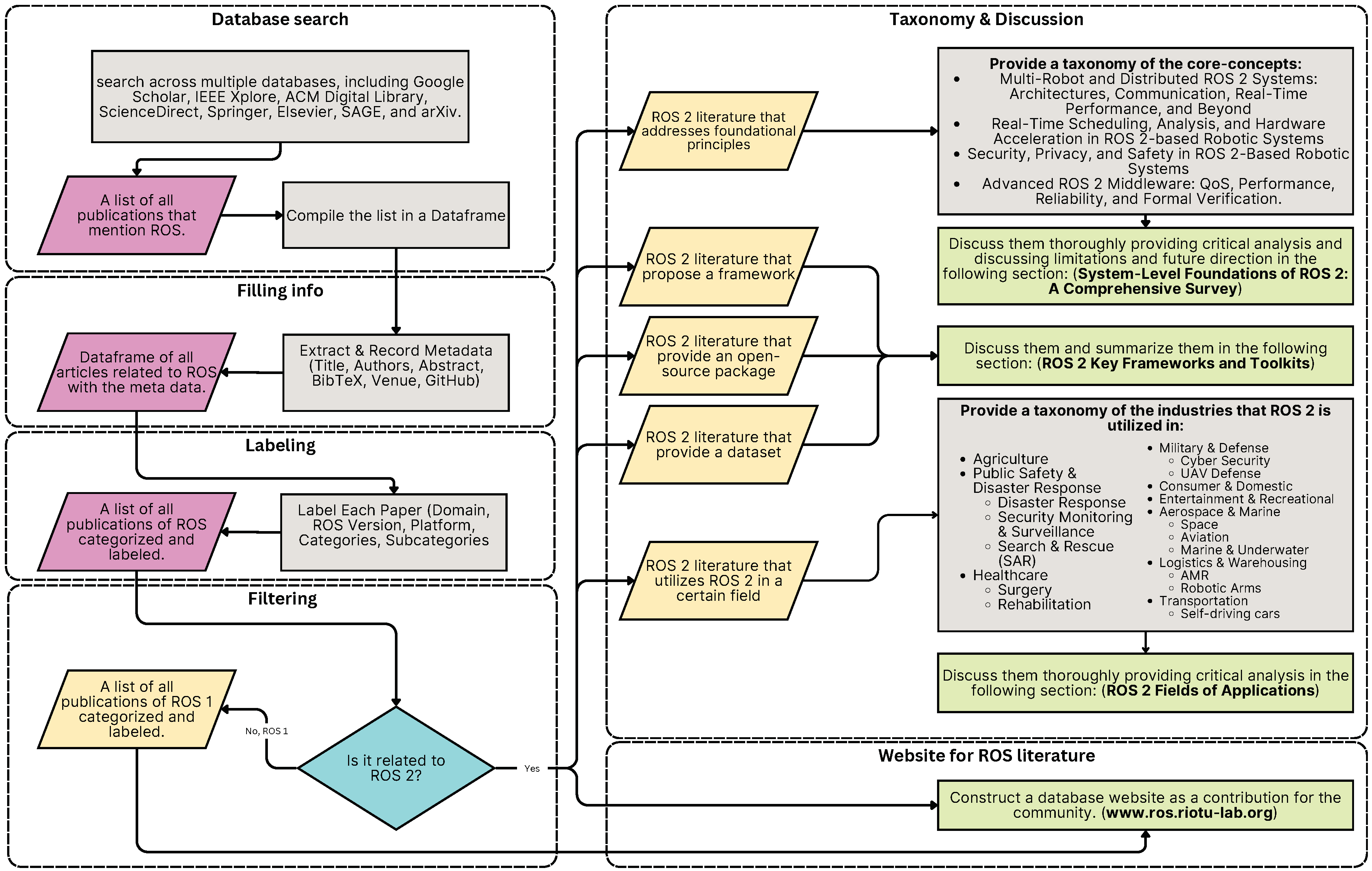

To systematically investigate these questions, we designed a structured review methodology consisting of data collection, filtering, classification, and analysis steps (see

Figure 2.

1.2.1. Data Collection and Sources

An extensive literature search was conducted across multiple academic databases, including Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, Springer, Elsevier, SAGE, and arXiv. The search terms included "ROS 2," "Robot Operating System 2," "ROS middleware," "ROS security," "ROS real-time," and other relevant keywords. No restrictions were placed on publication year to ensure coverage of both early-stage and recent research. Additionally, reference lists of selected papers were examined to capture relevant studies that may not have appeared in initial search results.

1.2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

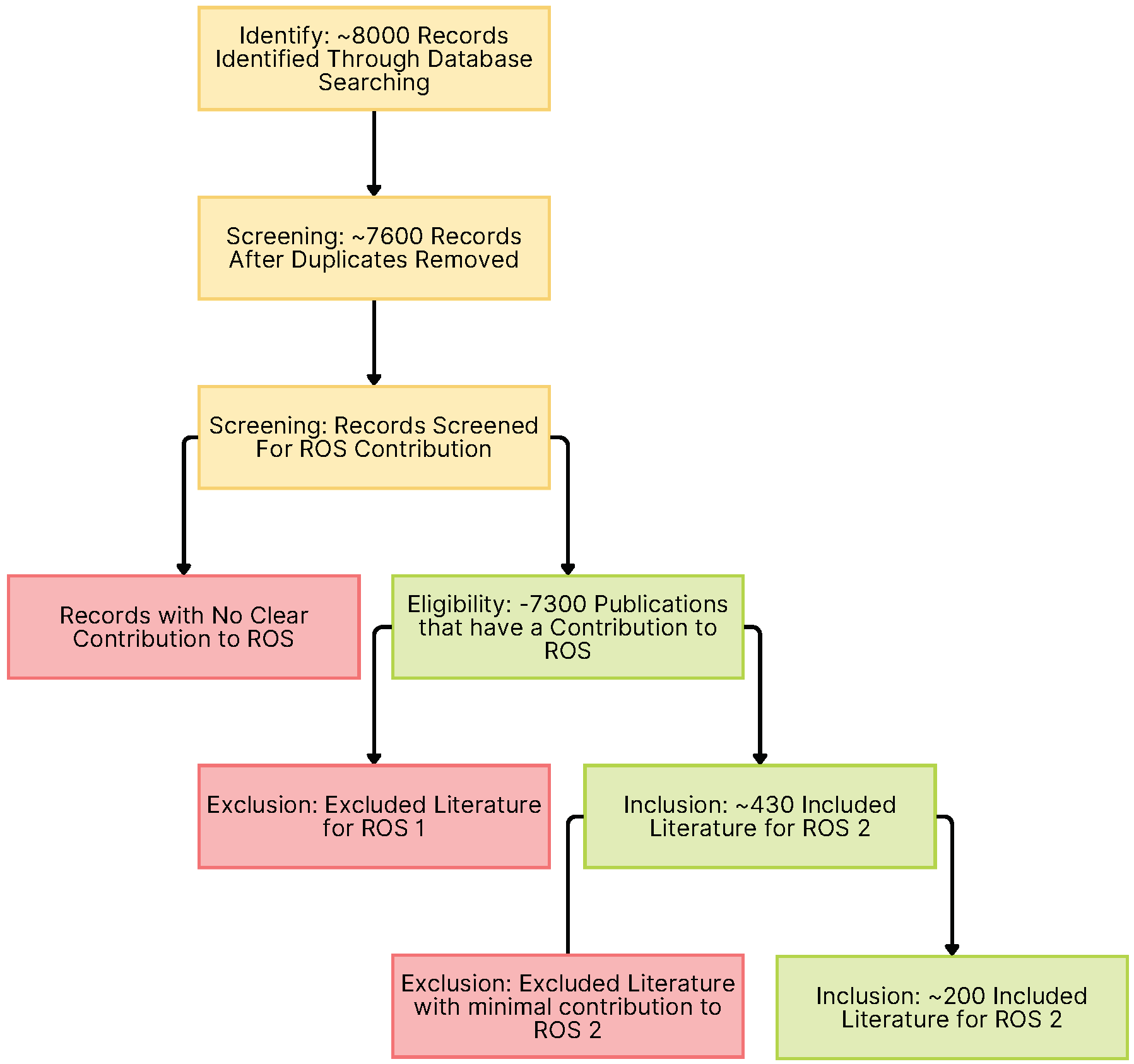

Figure 3 illustrates the rigorous filtering process that was applied to ensure the relevance and quality of the selected publications. The inclusion criteria were carefully designed to maintain high academic standards. First, studies that provided detailed discussions of ROS 2’s architecture, middleware, security, real-time performance, or adoption were included as they offer direct insights into the system’s capabilities. Comparative analyses between ROS 1 and ROS 2 were also incorporated to understand the evolutionary improvements and potential migration challenges. The review focused on peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and preprints from reputable sources to ensure scientific rigor. Additionally, research proposing new frameworks, tools, or open-source packages based on ROS 2 was included to capture innovative developments in the field. Empirical research evaluating ROS 2 performance in real-world applications was particularly valuable for understanding practical implementation challenges.

The exclusion criteria were equally stringent. Articles that merely mentioned ROS 2 without substantive discussion were excluded as they provided limited analytical value. Studies focusing exclusively on ROS 1 without addressing the transition to ROS 2 were omitted to maintain relevance to the current technological landscape. Non-peer-reviewed materials, such as blog posts, opinion pieces, and editorial notes, were excluded to ensure academic quality. Furthermore, duplicate records and papers lacking sufficient methodological details for reproducibility were removed to maintain the integrity of the analysis.

After applying these criteria, 7,371 ROS-related publications were retained, of which 435 were specifically focused on ROS 2.

1.2.3. Data Processing and Classification

Each of the 435 ROS 2 publications was systematically categorized to facilitate structured analysis. The classification framework encompassed multiple dimensions to ensure comprehensive coverage. The research domain classification examined various technical aspects, including multi-robot systems, security implementations, real-time scheduling mechanisms, middleware solutions, communication reliability protocols, and distributed systems architectures.

The robotic platform categorization covered a wide spectrum of applications, from aerial vehicles (UAVs) and ground vehicles (UGVs) to humanoid robots, industrial robots, and marine robotics systems. This classification helped identify platform-specific challenges and solutions. The application area analysis focused on key sectors such as healthcare, agriculture, autonomous navigation, logistics, and industrial automation, providing insights into domain-specific requirements and adaptations.

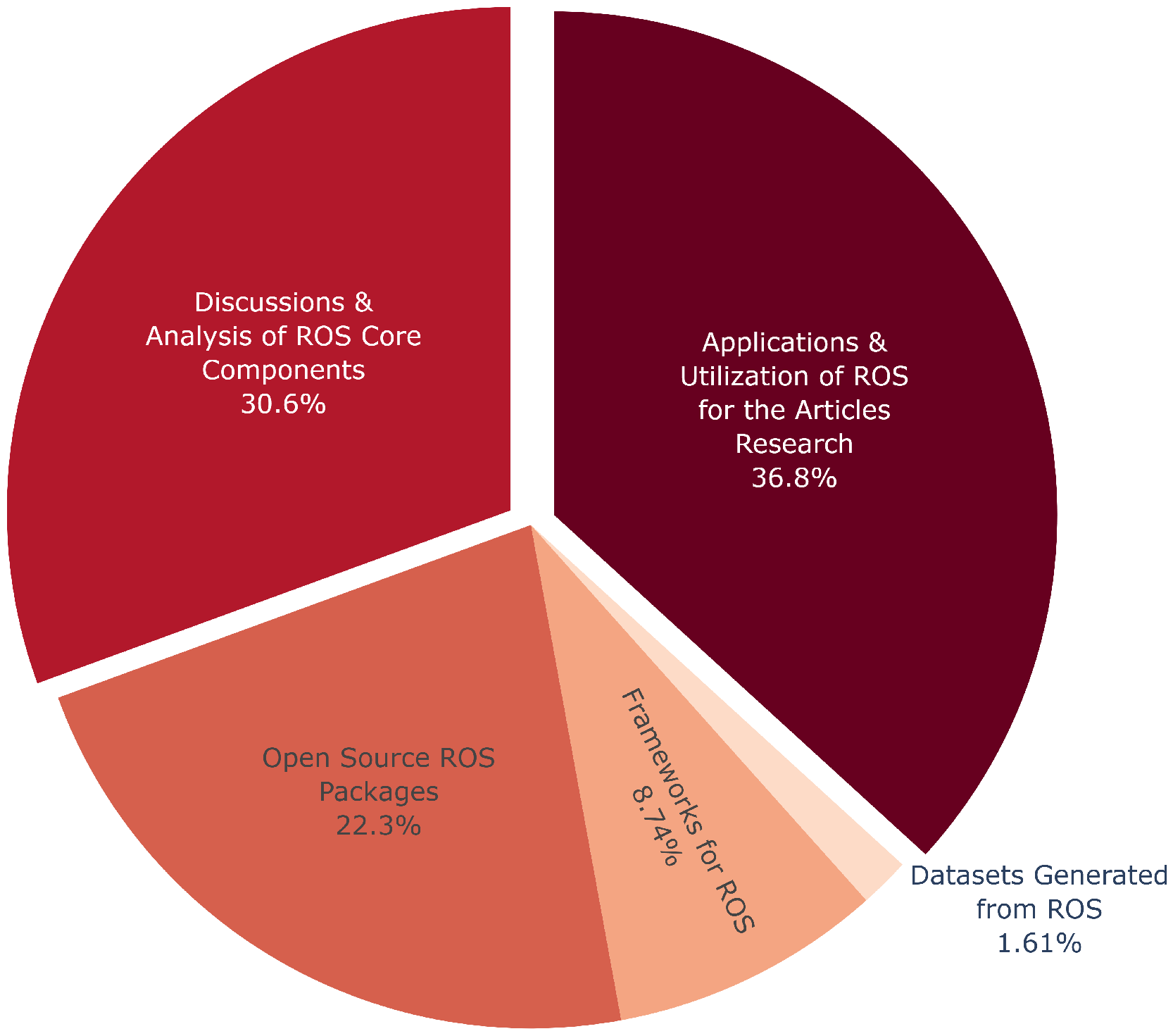

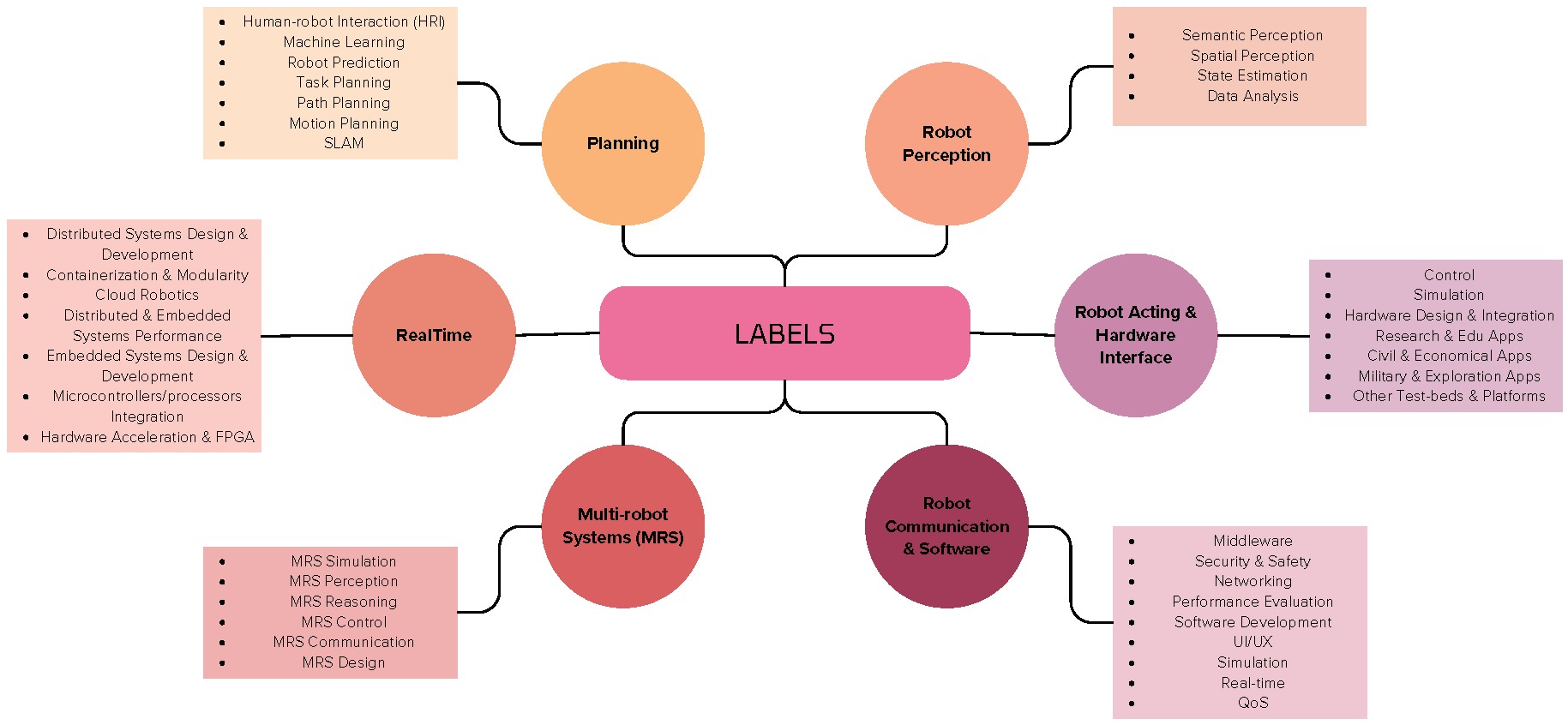

The contribution type classification that is shown in

Figure 4 provided another important analytical dimension. Papers discussing fundamental aspects of ROS 2, such as architecture, security, and middleware improvements, were categorized as core component analyses. Research focused on developing new libraries, simulators, or infrastructure enhancements was classified under framework development. Studies contributing publicly available software tools or frameworks were categorized as open-source packages. Application-focused research utilizing ROS 2 for specific problem domains, such as autonomous vehicles or industrial robotics, formed a distinct category. Publications presenting sensor datasets or benchmarking data collected using ROS 2 were classified as dataset contributions.

To ensure accuracy and consistency, categorization was performed independently by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion and consensus.

1.2.4. Analysis and Synthesis

Following the classification, the literature was systematically mapped to specific sections of the survey. The technical advancements section (

Section 3) provides a comprehensive analysis of improvements in middleware implementations, real-time processing capabilities, and security features. This is followed by an examination of industry-specific applications (

Section 4), which explores ROS 2 adoption across different fields while identifying both success stories and implementation challenges. The challenges and adoption barriers section (

Section 5) presents a detailed analysis of critical factors such as scalability limitations, migration difficulties, and real-time performance constraints.

Additionally, a thematic analysis was conducted to identify emerging trends in ROS 2 research, highlighting areas requiring further exploration. This analysis revealed patterns in development approaches, common challenges, and potential future directions for the ROS 2 ecosystem.

1.2.5. Open-Source Database for Reproducibility

To enhance transparency and accessibility, all processed data have been compiled into a publicly available ROS 2 literature database at /

https://www.ros.riotu-lab.org. This database allows filtering by research domain, ROS version, and robotic platform, ensuring continued research contributions. Metadata such as citation counts, publication venues, and GitHub links are included to facilitate further analysis. The database serves as a valuable resource for researchers and practitioners working with ROS 2, providing a comprehensive overview of current research and development efforts in the field.

1.3. Related Surveys

The body of literature on ROS 2 has grown significantly, with various surveys addressing specific aspects of this robotic operating system. While these studies contribute valuable insights, their focus has often been narrow and fragmented, leaving critical gaps in the overall understanding of ROS 2’s ecosystem. This subsection critically examines prior surveys, their methodologies, and the limitations that our work seeks to address. A summarized comparison is presented in

Table 1.

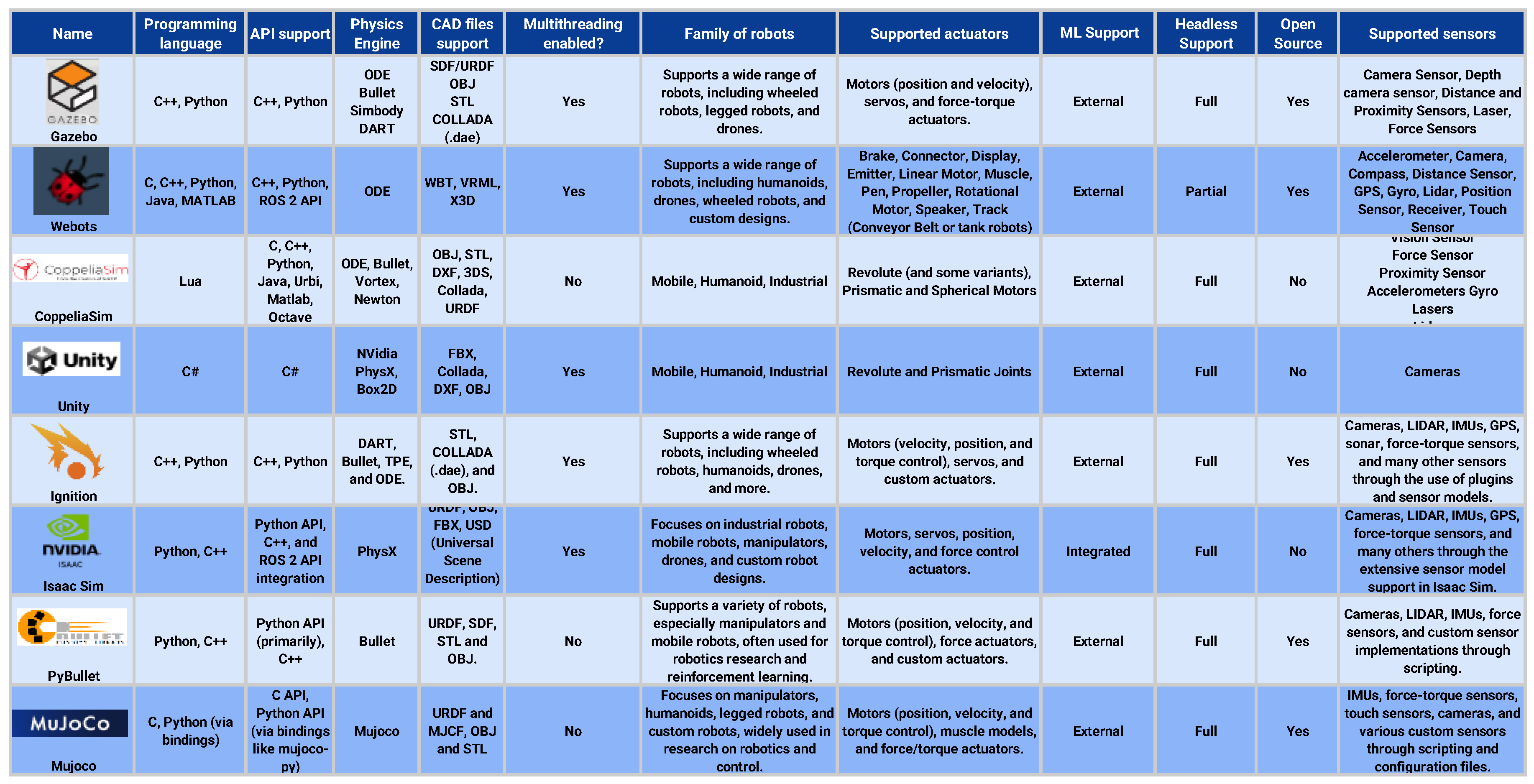

Several noteworthy surveys have explored ROS 2 from different perspectives. Audonnet et al. [

9] conducted a systematic comparison of simulation frameworks for robotic arm manipulation but did not address broader middleware or real-time concerns. Zhang et al. [

10] reviewed distributed robotic systems within the edge-cloud continuum, emphasizing ROS 2’s role in decentralized architectures. However, this study was technology-focused and did not evaluate adoption barriers, security risks, or performance trade-offs. Similarly, Macenski et al. [

11] provided a detailed review of mobile robotics algorithms within ROS 2, focusing on navigation strategies while neglecting middleware advancements and security challenges.

Other studies have examined specific technical challenges within ROS 2. Choi et al. [

12] explored priority-driven real-time scheduling, addressing deterministic execution but without considering its integration into multi-robot systems. Macenski et al. [

13] provided an overview of ROS 2’s design, architecture, and applications, though the discussion lacked empirical validation of performance metrics. DiLuoffo et al. [

14] emphasized security concerns, advocating for improved cryptographic measures but failing to assess real-world security implementations. Alhanahnah [

15] investigated software quality in ROS through static analysis but did not extend the discussion to ROS 2’s modular improvements.

Despite these contributions, existing surveys exhibit several methodological gaps. Many are domain-specific, lacking a holistic analysis that spans multiple research areas. Some fail to apply systematic literature review principles, relying on selective paper collections without clear inclusion-exclusion criteria. Moreover, prior studies rarely integrate empirical benchmarks, making it difficult to assess the actual performance impact of proposed solutions. Additionally, while ROS 2’s evolution over time is crucial for understanding its maturity, few surveys offer longitudinal analyses of adoption trends.

This survey aims to address these gaps by providing a comprehensive, systematic review of ROS 2 research across multiple dimensions: middleware advancements, real-time capabilities, security, modularity, and industry adoption. Unlike prior studies, we introduce a curated, publicly accessible database of ROS and ROS 2 literature, categorizing publications by research domain, robotic platform, industry focus, and contribution type. By synthesizing insights across different fields, we present a broader and more interconnected understanding of ROS 2, highlighting key challenges and emerging research directions that have not been adequately covered in previous surveys. Furthermore, by systematically analyzing these dimensions, this survey addresses our research questions regarding how ROS 2 improves upon ROS 1, what factors influence its adoption across industries, and what barriers hinder its widespread deployment. Through this structured investigation, we aim to provide a clearer roadmap for researchers and practitioners seeking to enhance ROS 2’s capabilities and accelerate its integration into real-world robotic systems.

1.4. Contributions

This survey systematically examines ROS 2, addressing three key research questions: (1) How does ROS 2 improve upon ROS 1 in terms of architecture, middleware efficiency, real-time performance, and security? (2) What are the key trends, challenges, and solutions in adopting ROS 2 across various industries? (3) What barriers hinder its widespread deployment, and how can they be addressed? Our main contributions are as follows:

- 1.

A Systematic Review of ROS 2 Research – To answer RQ1, we conduct a structured analysis of middleware advancements, real-time scheduling, security, modularity, and multi-robot systems. By comparing ROS 2’s improvements over ROS 1, we highlight enhancements in communication (DDS), real-time constraints, and security mechanisms, while identifying unresolved technical challenges.

- 2.

Empirical Assessment of Adoption Trends and Challenges – Addressing RQ2, we evaluate the adoption of ROS 2 in industries such as autonomous vehicles, healthcare, industrial automation, and logistics. We identify key drivers (e.g., modularity, improved middleware) and major barriers (e.g., migration complexity, deterministic execution issues, and security risks) that impact real-world scalability.

- 3.

Mapping the ROS 2 Ecosystem – Supporting RQ2 and RQ3, we analyze open-source frameworks, libraries, and tools, assessing their adoption, technical maturity, and gaps in the ecosystem. By investigating influential GitHub repositories and industrial contributions, we highlight areas requiring further development.

- 4.

A Publicly Accessible ROS 2 Literature Database – To address RQ3, we introduce a curated, open-access database categorizing ROS 2 research by domain, robotic platform, industry, and contribution type, enhancing reproducibility and guiding future advancements.

By bridging theoretical insights with real-world applications, this survey provides a structured roadmap to accelerate ROS 2 adoption and development.

1.5. Paper Structure

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of ROS and ROS 2, outlining their development history, core functionalities, and key differences.

Section 3 presents a comparative analysis of ROS 1 and ROS 2, highlighting architectural improvements in middleware, real-time performance, and security.

Section 4 explores critical research areas within ROS 2, including security, real-time capabilities, multi-robot systems, and communication frameworks, offering insights into ongoing advancements and challenges.

Section 5 reviews the diverse applications of ROS 2 across industries such as autonomous systems, healthcare, and logistics.

Section 6 discusses ROS 2 frameworks, toolkits, and notable open-source contributions, examining their role in system development and adoption.

Section 7 introduces the curated ROS 2 literature database, analyzing key trends and research directions.

Finally,

Section 8 summarizes the survey’s findings, and highlights the survey’s answers to the research questions.

3. ROS vs. ROS 2

While

Section 2 explored the architectural advancements of ROS 2, this section focuses on the non-architectural differences that impact its usability, flexibility, and adoption. These differences span programming language support, execution models, transformation handling, navigation frameworks, security mechanisms, and platform compatibility.

This section directly contributes to Research Question 1 by further analyzing how ROS 2 improves upon ROS 1 beyond its core architecture. Understanding these enhancements provides insights into developer experience, system interoperability, and practical deployment considerations, all of which influence ROS 2’s suitability for real-world robotic applications. Through this analysis, we highlight how these refinements collectively enhance performance, security, scalability, and cross-platform support, further strengthening ROS 2’s position as the next-generation standard for robotic software development.

3.1. Programming Languages (C++ and Python Differences)

In ROS 2, both C++ and Python programming languages are embraced, but their utilization differs from ROS.

C++ in ROS 2: ROS 2 offers enhanced support for modern C++ features, including move semantics and lambda functions. This improved support leads to better performance and code readability in ROS 2 applications. Developers can leverage new language features and libraries that were previously unavailable in the older C++03 version. Notably, certain core libraries in ROS 2 have been upgraded to support C++14, expanding the range of modern C++ capabilities that can be utilized. These advancements empower developers to take full advantage of the latest features and functionalities offered by the C++ programming language.

Python in ROS 2: In contrast to ROS, which predominantly utilized Python 2, ROS 2 adopts Python 3 as its primary version. Consequently, ROS 2 packages are primarily written in Python 3. This transition allows developers to leverage recent Python enhancements, such as type hints and improved asyncio support. By aligning with the broader Python language community, ROS 2 enables seamless integration with other Python-based tools and libraries. However, it’s important to note that compatibility updates are required for any existing Python 2 code intended for ROS 2 usage.

Language-Agnostic Communication Interfaces: One of the notable advancements in ROS 2 is the introduction of the Abstract DDS interface, a language-agnostic communication protocol. This protocol enables seamless interaction and communication between nodes written in different programming languages. With DDS, nodes can exchange messages and information efficiently, regardless of whether they are implemented in C++, Python, or any other supported language. This language-agnostic approach facilitates interoperability and collaboration among diverse robotic systems.

These disparities in language support between ROS and ROS 2 emphasize the significance of staying abreast of the latest language features and standards. By accommodating modern C++ and Python versions, ROS 2 empowers developers to fully capitalize on the latest advancements in these languages, enhancing the quality and efficiency of their robotic applications. Ultimately, the choice between C++ and Python hinges on the specific requirements of the target robotics system, and ROS 2’s language flexibility caters to diverse needs.

3.2. Executors

In ROS 2, executors play a pivotal role in managing the execution of tasks within a node’s lifecycle. They facilitate communication between nodes and ensure the execution of callbacks for incoming messages, services, and actions, significantly influencing the overall ROS 2 architecture.

ROS 2 encompasses three executor types each offering distinct characteristics and benefits:

SingleThreadedExecutor: This executor executes all callbacks within a single thread, employing a round-robin scheduling approach to ensure fairness between tasks. However, computationally intensive tasks may experience slower execution due to the shared thread among all tasks.

MultiThreadedExecutor: Designed to handle high workloads and computationally intensive tasks, this executor employs multiple threads to execute callbacks concurrently. While it provides improved performance, careful synchronization is necessary to avoid potential race conditions or deadlocks.

StaticSingleThreadedExecutor: This executor is similar to SingleThreadedExecutor but is specifically designed for nodes with a fixed set of entities (such as sensors, actuators, or other components) known during the compilation process. It optimizes runtime costs by scanning the structure of the node, including subscriptions, timers, service servers, and action servers, only once during node addition. Unlike other executors, it does not regularly scan for changes. Therefore, the StaticSingleThreadedExecutor is most suitable for nodes that create all their subscriptions, timers, and other entities during initialization and do not dynamically add or remove them during runtime. By eliminating the need for continuous scanning, it improves performance and efficiency in such static systems.

In contrast, ROS employs a " spinner " mechanism to manage callback execution within a node’s lifecycle. Two primary spinner types are available:

ros::spin(): This single-threaded spinner sequentially processes callbacks within a single thread until the node is shut down. It represents the simplest and most commonly used spinner in ROS.

ros::AsyncSpinner: This multi-threaded spinner concurrently processes callbacks using multiple threads, suitable for scenarios involving computationally intensive tasks or varying callback execution times.

While spinners in ROS serve a similar purpose to executors in ROS 2, the latter offers advanced features and greater flexibility in task execution, including the StaticSingleThreadedExecutor for static systems. Moreover, introducing the DDS middleware in ROS 2 necessitates a refined and adaptable approach to task execution, effectively addressed by the concept of executors.

Using executors in ROS 2 provides efficient task management and optimal utilization.

3.3. Transformations: tf vs tf2

The original library for managing transforms in RO), known as tf [

18], utilizes a static transform tree to outline the relationships between coordinate frames. However, tf exhibits certain limitations, including susceptibility to errors during concurrent multi-thread access to the transform tree and inefficiency when handling large trees.

In contrast, tf2, an advanced version, employs a more efficient data structure for the transform tree representation, enhancing both speed and robustness. It is designed to be thread-safe, thereby eliminating the risk of errors during simultaneous access by multiple threads.

A novel feature introduced in tf2 is the Buffer, a sophisticated data structure that oversees the transform tree. It offers APIs for querying transforms between coordinate frames, thereby increasing the versatility and usability of the system.

A significant distinction between tf and tf2 lies in their support for coordinate representations. While tf is limited to the XYZ Euler angle representation for rotations, tf2 supports multiple representations. These include quaternions, rotation matrices, and angle-axis representations, thereby offering a more comprehensive and flexible system for users.

Moreover, tf2 introduces several new features, including support for non-rigid transforms and the capability to interpolate between transforms. It also enhances debugging and visualization support, thereby simplifying the process of diagnosing issues with the transform tree.

To summarize, due to its superior performance, thread safety, and additional features, tf2 is the recommended library for managing transforms in ROS 2. Its design and functionality improvements over tf make it a more robust and efficient tool for managing coordinate frame relationships.

3.4. ROS 2 Navigation Stack: Main Features and Comparison with ROS 1

The ROS 2 Navigation Stack, also known as Navigation2, is a significant upgrade from the ROS 1 navigation stack, with several key features that enhance its functionality and usability. A comprehensive description of the ROS 2 Navigation Stack can be found in the following reference: [

19]. In what follows, we present a systematic and methodological comparison of the ROS 1 and ROS 2 navigation stacks:

Task Orchestration using Behavior Trees introduces the use of a behavior tree for task orchestration, a feature absent in ROS 1. This tree orchestrates planning, control, and recovery tasks, with each node invoking a remote server to compute one of these tasks using various algorithm implementations.

Modularity and Configurability: Navigation2 is designed to be highly modular and configurable, a marked improvement over ROS 1. It employs a behavior tree navigator and task-specific asynchronous servers, each of which is a ROS 2 node hosting algorithm plugin. These plugins are libraries dynamically loaded at runtime, allowing for unique navigation behaviors to be created by modifying a behavior tree.

Managed Nodes: ROS 2 introduces the concept of Managed Nodes, servers whose life-cycle state can be controlled. Navigation2 exploits this feature to create deterministic behavior for each server in the system, a feature not present in ROS 1.

Feature Extensions: Navigation2 supports commercial feature extensions, allowing users with complex missions to use Navigation2 as a subtree of their mission. This is a unique feature not found in ROS 1.

Multi-core Processor Utilization: Unlike ROS 1, Navigation2 architecture leverages multi-core processors and the real-time, low-latency capabilities of ROS 2. This allows for more efficient processing and faster response times.

Algorithmic Refreshes: Navigation2 focuses on modularity and smooth operation in dynamic environments. It includes the Spatio-Temporal Voxel Layer (STVL), layered costmaps, the Timed Elastic Band (TEB) controller, and a multi-sensor fusion framework for state estimation, Robot Localization. Each of these supports holonomic and non-holonomic robot types, a feature not as developed in ROS 1.

State Estimation: Navigation2 follows ROS transformation tree standards for state estimation, making use of modern tools available from the community. This includes Robot Localization, a general sensor fusion solution using Extended or Unscented Kalman Filters. This is a more advanced approach compared to ROS 1.

Quality Assurance: Navigation2 includes tools for testing and operations, such as the Lifecycle Manager, which coordinates the program lifecycle of the navigator and various servers. This manager steps each server through the managed node lifecycle: inactive, active, and finalized. This systematic approach to quality assurance is a significant upgrade from ROS 1.

Navigation2 builds on the successful legacy of ROS Navigation but with substantial structural and algorithmic refreshes. It is more suitable for dynamic environments and a wider variety of modern sensors, making it a more advanced and versatile navigation stack than its predecessor, ROS 1.

3.5. ROS 2 Security

The key difference in security between ROS and ROS 2 is that ROS 2 has been designed with security in mind from the ground up, whereas security was not a primary consideration in the initial development of ROS.

In ROS, security mechanisms such as authentication and encryption were not implemented by default, leaving systems vulnerable to potential security threats. However, ROS users could implement security measures manually by using third-party libraries and plugins.

ROS 2, on the other hand, has a built-in security framework that provides authentication, encryption, and access control by default. This framework enables ROS 2 to support secure communication between nodes and across networks, even when communicating with nodes that may not support security natively.

SROS2 (Secure ROS2) [

20] is a security extension for ROS 2 that provides additional security features beyond those provided by the ROS 2 security framework. SROS is designed to address some of the limitations of the ROS 2 security framework and to provide enhanced security for critical robotic applications. SROS provides a more flexible and configurable access control system than the default ROS 2 permission system, allowing administrators to define fine-grained access policies for topics, services, and nodes. This can help to ensure that sensitive data and resources are protected from unauthorized access.

Overall, by implementing SROS in ROS 2, users can benefit from additional security features that are not available in ROS. This can help to ensure the security and integrity of critical robotic applications while also providing a more flexible and configurable security solution that can be tailored to the specific needs of each application.

3.6. Comparison of Platform Support in ROS and ROS 2

ROS and its successor, ROS 2, are widely used frameworks for developing robotic systems. This section explores the level of support and compatibility with different operating systems in both frameworks. Specifically, we will examine the support for Windows, macOS, and Linux platforms, highlighting the advancements made in ROS 2.

Windows Support: When it comes to Windows support, ROS has experimental compatibility, while ROS 2 boasts more comprehensive and reliable support for Windows 10. The enhanced support in ROS 2 allows developers to leverage the framework more effectively on Windows machines, ensuring a stable and efficient environment for building robust robotic applications.

macOS Support: Both ROS and ROS 2 offer official support for macOS. However, ROS 2 surpasses its predecessor in terms of compatibility with the latest macOS versions. By capitalizing on the latest macOS features, such as the Metal graphics API, ROS 2 maximizes performance in specific applications. This advanced compatibility empowers developers to fully exploit the potential of macOS when constructing sophisticated robotics systems.

Linux Support: Both ROS and ROS 2 offer comprehensive support for Linux, with official support for various popular distributions. However, ROS 2 takes a more modular and flexible approach, making porting the framework to different Linux distributions and architectures easier. This flexibility is particularly advantageous in heterogeneous computing environments, allowing developers to deploy ROS 2 on various Linux systems.

The utilization of the DDS, which inherently possesses cross-platform capabilities, significantly facilitated the seamless compatibility of ROS 2 with Windows, macOS, and Linux. In contrast, ROS 1 relied on the specific TCPROS and UDPROS protocols, which were more tightly coupled with the Linux environment, limiting its cross-platform compatibility.

In this section, we have explored non-architectural advancements in ROS 2, focusing on improvements in programming language support, execution models, transformation handling, navigation frameworks, security mechanisms, and platform compatibility. These enhancements directly address Research Question 1, demonstrating how ROS 2 refines developer experience, flexibility, and cross-platform usability in ways that go beyond core architectural improvements. By adopting modern C++ and Python standards, improving execution models through advanced executors, strengthening security, and leveraging DDS for seamless cross-platform support, ROS 2 removes many limitations previously hindering its adoption in real-world applications.

However, while these enhancements improve usability and system design, meeting the stringent requirements of modern robotics—such as real-time execution, determinism, safety, and fault tolerance—requires deeper exploration at the system level. The next section delves into these advanced technical aspects by examining middleware optimizations, real-time scheduling, security, and multi-robot coordination. These foundational elements play a crucial role in ensuring that ROS 2 can support high-performance, safety-critical, and large-scale robotic deployments, ultimately shaping its future adoption in both research and industry.

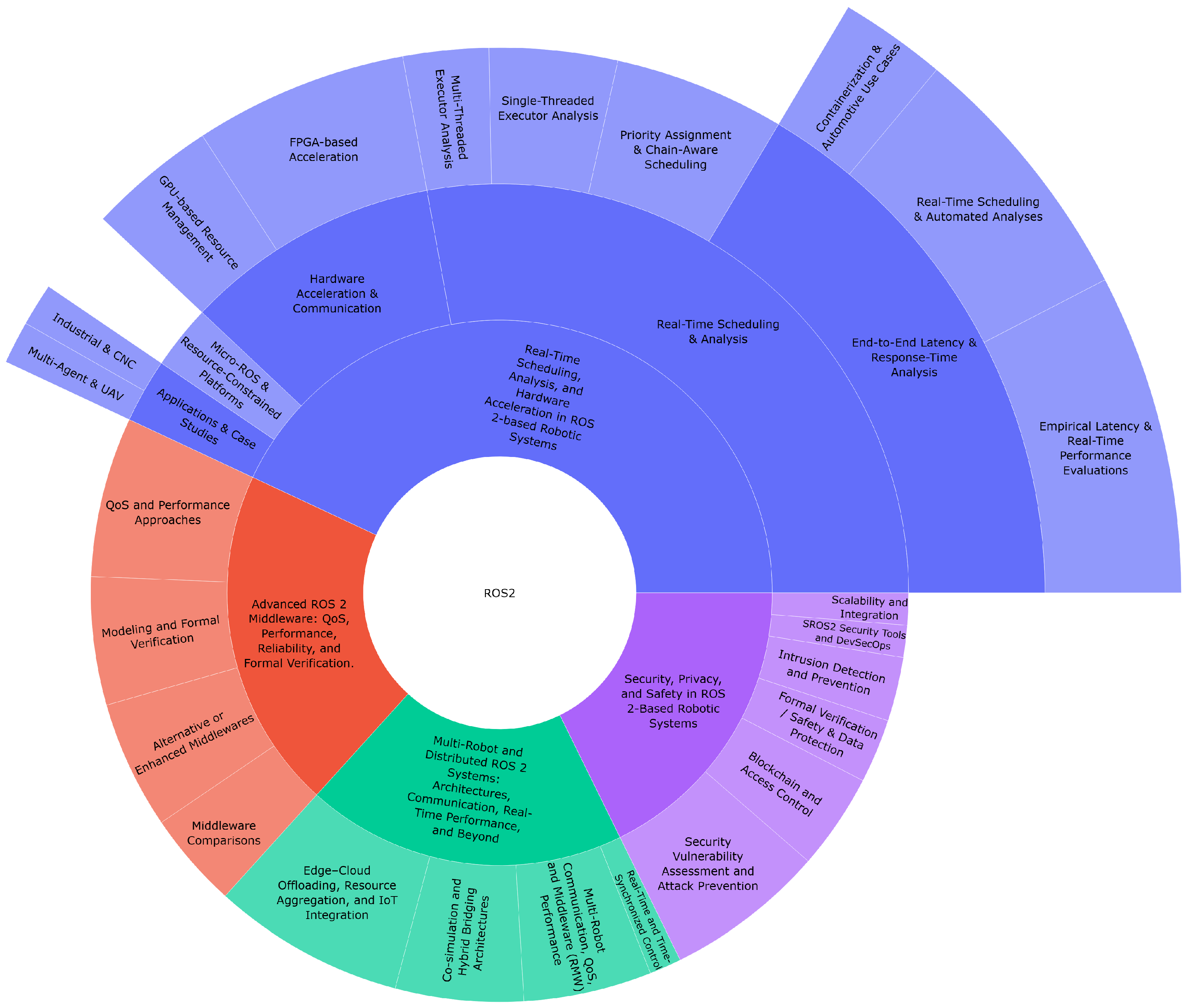

4. Advanced ROS 2: Technical Innovations, Deployments, and Adoption Challenges

This section offers a thorough analysis of key technical and practical facets in ROS 2, presenting four in-depth areas that collectively address all three research questions (

RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3). First, we examine

middleware innovations such as DDS-based QoS, zero-copy techniques, and formal verification (

RQ1), highlighting their growing presence in industrial sectors (

RQ2) and adoption barriers due to complexity and scalability concerns (

RQ3). Next, we focus on

real-time scheduling and hardware acceleration, demonstrating how advanced executors, FPGAs, and GPUs can enable near-deterministic performance (

RQ1) for mission-critical deployments (

RQ2), despite organizational and cost-related hurdles (

RQ3). We then explore

security, privacy, and safety in ROS 2, underscoring technical solutions and industry adoption patterns (RQ 1–2) while noting overhead and integration challenges (

RQ3). Finally, we review

multi-robot and distributed systems—from bridging methods to edge–cloud offloading—showcasing progress and the need for further standardization.

Figure 7 shows sunburst chart of literature taxonomy for those technical facets of ROS 2

4.1. Advanced ROS 2 Middleware

4.1.1. RQ1 – Technical Foundations and Innovations

DDS Backbone and QoS Strategies: ROS 2 builds on a DDS-based communication layer, enabling flexible

quality-of-service (QoS) configurations to address latency, reliability, and scheduling demands. As summarized in

Table 2, most works focus on leveraging or extending these QoS policies—such as

RELIABLE vs.

BEST_EFFORT,

KEEP_LAST vs.

KEEP_ALL, and deadline constraints—to match application needs, including real-time data fusion, sensor streaming, and distributed control [

22,

24,

25].

Because of DDS’s pluggable architecture,

alternative or enhanced middlewares have also emerged (e.g., Zenoh, Kafka/MQTT bridges) [

30,

32]. Researchers propose these solutions to optimize network usage in edge or wireless scenarios [

33].

Zero-Copy and Shared Memory Transport: In ROS 2, zero-copy and shared-memory transport mechanisms offer a significant performance boost by eliminating the need for serialization, thereby reducing overhead for large data payloads such as camera feeds or point clouds [

22,

23]. This approach allows nodes to access shared data directly, which can drastically reduce latency and improve throughput in high-bandwidth applications. However, leveraging these benefits comes with its own set of challenges: managing concurrency becomes more complex when multiple nodes access shared buffers, often requiring intricate synchronization strategies to prevent race conditions or data corruption [

21,

24]. Consequently, while zero-copy and shared-memory transports are promising, the ROS 2 community continues to explore robust solutions that balance high performance with safe, reliable data sharing in multi-node environments.

Modeling, Formal Verification, and Comparisons: In ROS 2, modeling, formal verification, and comparative performance studies play a crucial role in ensuring system robustness and efficiency. Researchers have increasingly adopted formal verification techniques—such as timed automata and model-checking frameworks—to rigorously establish properties like deadlock freedom, timely deadline adherence, and reliable end-to-end message delivery [

26,

28,

29]. These methods not only provide strong guarantees about system behavior but also help uncover subtle flaws that might be overlooked during traditional testing, albeit at the expense of increased modeling complexity and computational resources. Simultaneously, empirical studies that compare latency, throughput, and CPU usage under varied QoS settings or network conditions offer valuable insights into how different middleware configurations perform in real-world scenarios [

34,

35,

36], thereby guiding developers in optimizing ROS 2 deployments for diverse application needs.

Relevant Equations, Algorithms, and Results: Equations

1– illustrate typical metrics, such as:

while pseudo-code algorithms (Algorithms 1–6) demonstrate core middleware functionalities, ranging from real-time dataflow scheduling to safe zero-copy transfers (Sec.

Section 4.1). Reported testbed results show up to

lower latency in zero-copy scenarios [

22], though encryption overhead can inflate communication delays up to

or

[

25].

|

Algorithm 1:Real-Time Dataflow Scheduling |

- 1:

Initialize dataflow_graph, deadlines

- 2:

for each pipeline_stage in dataflow_graph do

- 3:

pipeline_stage.priority ← assign_priority(deadlines)

- 4:

end for - 5:

whilesystem_activedo

- 6:

for each stage in sorted_by_priority(dataflow_graph) do

- 7:

if stage.ready_to_run() then

- 8:

stage.execute()

- 9:

end if

- 10:

end for

- 11:

wait_for_next_cycle()

- 12:

end while |

|

Algorithm 2:Parallel Node Launch with Shared Memory |

- 1:

shared_mem_id←allocate_shared_pool(size=SM_SIZE)

- 2:

for each node_name in node_list do

- 3:

process ← spawn_node(node_name, shared_mem_id)

- 4:

set_affinity(process, core_map[node_name])

- 5:

add_to_supervisor(process)

- 6:

end for - 7:

start_supervisor() |

|

Algorithm 3:Safe Zero-Copy Transfer with Locking |

- 1:

procedurepublish_data(buffer) - 2:

lock(mutex_buffer)

- 3:

write_payload(buffer, new_data)

- 4:

set_ready_flag(buffer)

- 5:

unlock(mutex_buffer)

- 6:

notify_subscribers()

- 7:

end procedure

- 8:

proceduresubscribe_data(buffer) - 9:

if wait_for_ready(buffer) then

- 10:

lock(mutex_buffer)

- 11:

local_copy ← read_payload(buffer)

- 12:

clear_ready_flag(buffer)

- 13:

unlock(mutex_buffer)

- 14:

return local_copy - 15:

end if

- 16:

end procedure |

|

Algorithm 4:Mode Change for Real-Time Streams |

- 1:

procedureswitch_mode(current_mode, new_mode) - 2:

broadcast_pause(current_mode)

- 3:

wait_all_stages_stop(current_mode)

- 4:

reconfigure_params(new_mode)

- 5:

set_active_mode(new_mode)

- 6:

broadcast_resume(new_mode)

- 7:

end procedure |

|

Algorithm 5:Fault-Tolerant Node Heartbeat |

- 1:

Initialize node_status_map

- 2:

while true do ▹ Runs every HEARTBEAT_INTERVAL ms - 3:

for each node in node_list do

- 4:

send_heartbeat_request(node)

- 5:

end for

- 6:

collect_responses()

- 7:

for each node in node_list do

- 8:

if no_recent_response(node) then

- 9:

attempt_restart(node)

- 10:

log_fault_event(node)

- 11:

end if

- 12:

end for

- 13:

end while |

|

Algorithm 6:Distributed Service Discovery |

- 1:

procedurediscover_services

- 2:

local_cache ← local_discovery()

- 3:

peers ← get_peer_list()

- 4:

for each peer in peers do

- 5:

remote_list ← request_discovery(peer)

- 6:

merge(local_cache, remote_list)

- 7:

end for

- 8:

return local_cache - 9:

end procedure - 10:

procedure publish_services(my_services) - 11:

peers ←get_peer_list()▹ Make sure we have the peer list - 12:

for each peer in peers do

- 13:

send_service_list(peer, my_services)

- 14:

end for

- 15:

end procedure |

4.1.2. RQ2 – Industry Trends and Real-World Deployments

Although these middleware advances are grounded in academic research, many industrial domains have begun integrating specialized QoS and DDS features in real-world systems. For instance, large-scale autonomous vehicle platforms rely on robust QoS parameters to handle high-bandwidth LiDAR and camera data with minimal packet loss [

23]. In industrial automation, real-time data exchange and consistent reliability are critical for coordinating robotic arms or conveyor subsystems; this has prompted interest in formal verification approaches to ensure safe concurrency when nodes share memory [

27,

28].

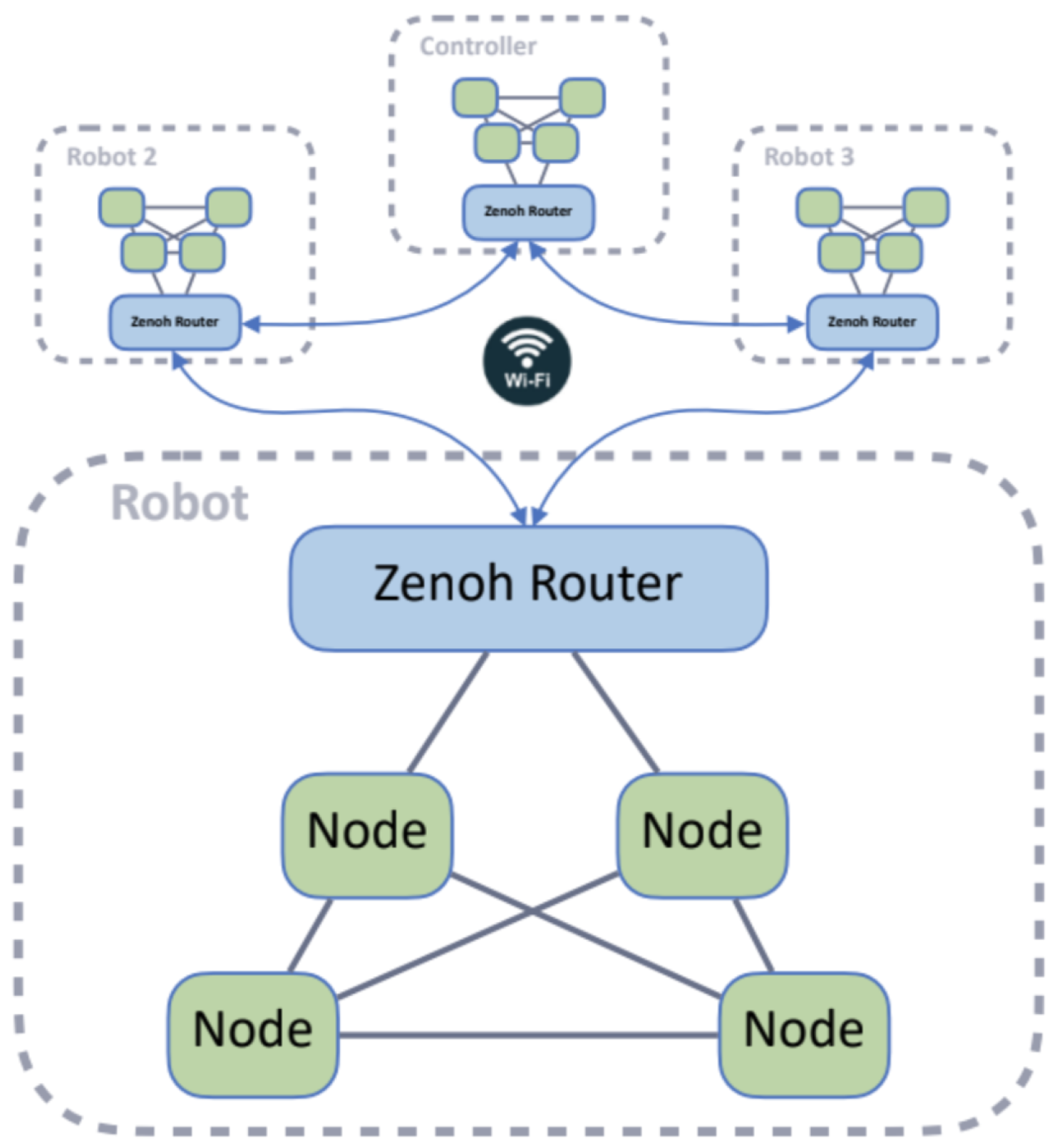

Adoption of Alternative RMWs and Legacy Interoperability: Some companies testing multi-robot fleets leverage

Zenoh-based RMW (see

Figure 8 for Zenoh architecture visualization) to reduce overhead in wireless or mobile deployments [

30]. By rethinking the traditional DDS discovery process, Zenoh advertises only resource interests—rather than the full set of publisher and subscriber details—thereby compressing discovery data and significantly reducing network traffic. Experimental results indicate that this approach can lower discovery overhead by up to 97% in worst-case scenarios, and even achieve reductions as high as 99.97% when combining resource generalization with warm start configurations. Moreover, Zenoh supports Internet-scale routing and peer-to-peer communication, integrating transparently into existing ROS 2 systems via the zenoh-plugin-dds. Meanwhile, bridging strategies (ROS 1–ROS 2 or DDS–MQTT) continue to emerge, as industry partners may still rely on legacy ROS 1 components or prefer to route select messages through an event-driven pipeline [

34]. These transitions reveal an ongoing trend of partial adoption, where advanced QoS or zero-copy features are applied selectively to high-throughput data channels while simpler or legacy topics remain unchanged.

Use Cases in Healthcare and Collaborative Robotics: Healthcare robotics highlights the need for

formal verification, especially in surgical or assistive systems with strict safety and reliability requirements [

29]. Collaborative robots in manufacturing also benefit from deterministic communication guaranteed by robust middleware setups, enabling safe human–robot coexistence under real-time constraints [

37].

4.1.3. RQ3 – Adoption Challenges and Future Solutions

Despite the technical promise, several hurdles limit broader industry uptake:

Technical Barriers: Middleware Complexity. DDS QoS parameters, concurrency control for zero-copy, and formal verification toolchains can be daunting. As

Table 3 indicates, a unified interface for memory-safe zero-copy under crash-fault conditions remains elusive [

24].

Organizational and Skill Gaps: Some organizations lack the in-house expertise to configure QoS or verify concurrency properties. In many real-world settings, default middleware settings remain unchanged—leading to suboptimal performance or, in the worst case, unintended reliability issues [

35].

Potential Solutions and Ongoing Efforts: Potential solutions and ongoing efforts in ROS 2 are taking a multi-pronged approach to address current challenges. One key direction is the move toward standardized QoS profiles and APIs, as initiatives within the ROS 2 community, such as those from the ROS 2 Working Groups, work to establish common presets for real-time, high-throughput, or secure applications—thereby reducing the guesswork involved in configuration. Additionally, there is growing interest in integrating formal verification tools directly into the build pipeline; embedding techniques like model-checking or timed automata analyses could streamline adoption and enhance system robustness, although scaling these methods remains a challenge [

28]. Moreover, efforts are underway to bring cutting-edge research into mainstream ROS 2 distributions. For instance, features like shared-memory transport have already begun to appear in newer releases, and future versions are expected to incorporate even more advanced HPC or fault-tolerant protocols [

32].

A broader consensus is that bridging these technical breakthroughs into official ROS 2 and DDS releases is essential for large-scale adoption. In particular, robust default configurations, improved documentation, and user-friendly tooling around zero-copy, QoS tuning, and formal verification would considerably lower adoption barriers for both academic labs and industrial teams.

4.2. Real-Time Scheduling and Hardware Acceleration in ROS 2

4.2.1. RQ1 – Technical Foundations and Innovations

Brief Overview and Taxonomy: Modern robotic applications often demand both deterministic behavior and high computational throughput. As shown in

Table 4, solutions in this domain can be categorized into

real-time scheduling & analysis,

hardware acceleration,

micro-ROS for constrained platforms, and

application-level case studies. A critical component is the choice and configuration of the

ROS 2 executor, which schedules callbacks under different threading or priority schemes [

38,

43], while hardware acceleration techniques (FPGA/GPU) target resource-intensive tasks [

60,

65].

Key Real-Time Scheduling Concepts: Compared to ROS 1’s single-threaded or round-robin executor, ROS 2 introduces multi-threaded executors and chain-aware priority assignment [

42,

45]. These approaches address end-to-end latencies through explicit priority mappings, specialized buffer management, and concurrency control. Empirical data show that naive round-robin scheduling can result in hundreds of milliseconds in worst-case latency; chain-based or priority-aware solutions reduce those latencies to tens or single digits of milliseconds [

46,

47].

Hardware Acceleration and Micro-ROS: Hardware acceleration strategies push heavy computations (e.g., computer vision, SLAM) to GPUs or FPGAs, reporting speedups between

and

[

61,

64]. Meanwhile, micro-ROS extends ROS 2 to microcontrollers [

68,

69], enabling real-time control loops on resource-constrained boards. Achieving deterministic performance in such systems typically hinges on specialized QoS setups, shared-memory optimizations, and tight integration of scheduling with hardware resources.

Equations and Algorithms Illustrating Real-Time Analysis: Numerous equations model end-to-end latency, scheduling interference, and buffer requirements [

43,

46]. A typical end-to-end latency formula might sum the callback execution (

) and interference (

) across a chain of nodes [

53] as shown in Eq.

4:

Likewise, hardware-acceleration speedups are often computed as

[

60], underscoring the gains from offloading. Algorithmic snippets 7–9 (e.g., multi-thread executors, aggregator nodes) frequently appear in studies proposing next-generation real-time frameworks [

40,

41].

where

is a callback’s execution time and

the scheduling interference.

|

Algorithm 7:Initial budget estimate |

- 1:

Input: set of executors

- 2:

for all executor without a budget do

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

end for - 6:

for all callback c with unbounded response times do

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

if then

- 10:

DegradeChain(c) ▹ example function call - 11:

else

- 12:

- 13:

end if

- 14:

end for - 15:

if no feasible partitioning for budgets found: degrade some chain |

|

Algorithm 8:Assignment improvement heuristic |

- 1:

Input: set of executors affecting response times - 2:

while (chain latency > goal) do

- 3:

for all do

- 4:

- 5:

end for

- 6:

Sort by decreasing d(e) - 7:

for all e in (in sorted order) do

- 8:

if then

- 9:

remove e from ; continue - 10:

end if

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

if (new partitioning is feasible) then

- 14:

candidate found; break inner loop - 15:

else

- 16:

▹ restore old value - 17:

end if

- 18:

end for

- 19:

if no candidate found: degrade chain - 20:

end while |

|

Algorithm 9:Waiting queue pool updating algorithm |

- 1:

Input: queue pool , old mapping , new mapping

- 2:

ifthen

- 3:

for do

- 4:

Add to

- 5:

end for

- 6:

end if - 7:

for all mapping do

- 8:

find such that and

- 9:

if then

- 10:

for all request in do

- 11:

if request. then

- 12:

Remove request from

- 13:

Insert request into (by timestamp ordering) - 14:

end if

- 15:

end for

- 16:

end if

- 17:

end for - 18:

ifthen

- 19:

for do

- 20:

Delete from

- 21:

end for

- 22:

end if |

Empirical Results and Performance Gains: Across the literature, specialized scheduling (priority- or chain-based) can yield up to

reductions in worst-case latency [

43], while GPU/FPGA acceleration brings 5–

speedups in vision or SLAM tasks [

65,

66]. Micro-ROS solutions can maintain

Hz control loops on low-power boards, provided that QoS settings limit packet loss [

69].

4.2.2. RQ2 – Industry Trends and Real-World Deployments

Industrial Automation and CNC: In industrial and CNC (computer numerical control) applications, real-time monitoring and rapid response are critical. Studies show that by combining priority-based executors and containerization, latencies below 1 ms can be achieved on production lines [

70]. Deployed systems often rely on

hardware accelerators to handle large sensor streams or complex inverse-kinematics calculations in real time.

Multi-Agent and UAV Deployments: For multi-agent robotics and UAV swarms, specialized scheduling ensures consistency in sensor fusion and flight control across distributed nodes [

71]. Edge or cloud offloading can reduce on-board CPU usage by up to 40% [

59], albeit at the cost of additional network latency. Container-based orchestration simplifies deployment of real-time containers, while micro-ROS extends basic flight-control loops onto small embedded hardware for distributed sensing.

GPUs, FPGAs, and Resource Mapping in Practice: Industrial integrators are also exploring hybrid CPU–FPGA solutions, especially in advanced manufacturing lines with machine vision or safety-critical controls [

63]. GPU-based pipelines appear in autonomous driving startups, where dense LiDAR or camera data must be processed at high frame rates [

66]. On the smaller scale, micro-ROS boards with real-time OS patches tackle simpler tasks (e.g., tactile sensors, low-level motor control).

4.2.3. RQ3 – Adoption Challenges and Future Solutions

Technical Barriers: Despite significant performance gains, multiple technical challenges hinder widespread real-time adoption. One major barrier is the complexity of executor concurrency; multi-threaded executors, while beneficial for performance, can incur substantial overhead if locks are not managed carefully [

40]. Additionally, the tuning of Quality of Service (QoS) parameters remains fragile. The reliance on vendor-specific DDS implementations, coupled with incomplete standardization, often forces trial-and-error configurations that undermine consistent real-time guarantees [

35]. Furthermore, the imperative for robust security introduces a conflict between performance and protection. Real-time constraints can be at odds with the overhead introduced by encryption or intrusion-detection measures, complicating the balance between securing data paths and maintaining optimal system performance [

57].

Industrial and Organizational Challenges: Industrial and organizational challenges are multifaceted. One major hurdle is the cost associated with specialized hardware; for instance, FPGAs, high-end GPUs, or real-time patched operating systems can be prohibitively expensive and often lead to vendor lock-in, thereby hindering broader adoption [

61]. Additionally, there is a noticeable lack of unified design practices across teams. This gap in expertise makes it difficult to seamlessly integrate real-time scheduling frameworks with high-performance computing acceleration, frequently resulting in implementations that are only partial or suboptimal.

Potential Solutions and Roadmap:Table 5 highlights several promising future directions. One potential solution is to encourage the ROS 2 community to adopt standard real-time QoS profiles. By using universal QoS presets for HPC or low-latency tasks, the configuration process can be simplified, reducing the guesswork that often hinders effective implementation. In addition, dynamic reconfiguration offers a compelling pathway forward. Techniques such as the partial reprogramming of FPGAs or automated container orchestration can enable adaptive real-time pipelines, as explored in [

63]. Enhancing security is another crucial aspect; integrating selective encryption or hardware-based enclaves can help protect critical data paths while incurring minimal performance overhead. Finally, easing the transition for industrial teams by consolidating tooling—such as using wizards and best-practice containers—can streamline the deployment of micro-ROS and edge offloading solutions, thereby accelerating the adoption of microcontroller-based or edge–cloud systems.

In conclusion, real-time scheduling and hardware acceleration in ROS 2 represents a powerful suite of solutions, yielding up to 2–80× improvements in end-to-end latency or throughput. Widespread adoption, however, remains tied to simplifying concurrency control, standardizing QoS, and addressing organizational or cost-related hurdles. By integrating these efforts under a cohesive roadmap (priority-based scheduling, hardware acceleration, micro-ROS, security integration), ROS 2 stands poised to meet the demanding performance needs of next-generation robotic platforms.

4.3. Security, Privacy, and Safety in ROS 2

4.3.1. RQ1 – Technical Foundations and Innovations

DDS-Based Security and Vulnerability Assessments: ROS 2 incorporates a DDS-based security model (SROS2) providing authentication, encryption, and access control at the transport layer. Yet, many deployments leave security partially configured, exposing nodes to replay attacks, unauthorized subscriptions, and malicious bridging [

14,

72,

73,

74]. Efforts to systematically analyze these vulnerabilities propose automated

attack surface assessments, revealing how default ROS 2 settings can be insufficient for mission-critical applications [

75].

Intrusion Detection and Prevention (IDP): Intrusion detection and prevention (IDP) in ROS 2 has garnered significant attention, with research increasingly leveraging domain-specific anomaly detection techniques and ensemble machine-learning classifiers to identify malicious or erratic behaviors in near-real-time [

76,

77]. These advanced methods allow the system to proactively halt suspicious actuator commands or block malicious topics, thereby reinforcing the overall integrity of the robotic network. Despite detection accuracies often exceeding 99%, a notable challenge lies in the high CPU and network overhead associated with these solutions, particularly as system scale increases [

76]. Ongoing research is focused on optimizing these approaches to ensure that the robust security provided does not come at the cost of significant performance degradation in large-scale ROS 2 deployments.

Blockchain and Advanced Access Control: In ROS 2, blockchain-based systems and attribute-based access control (ABAC) are emerging as promising solutions for secure multi-robot collaboration. These approaches enable the logging of command transactions and the enforcement of fine-grained, role-specific permissions, which not only enhances security but also provides a transparent audit trail for system actions [

78,

79,

80]. Event-driven blockchain architectures, in particular, offer a way to reduce latency overhead by triggering consensus only when necessary, rather than relying on an always-on consensus mechanism. However, while these innovations bring robust security features to ROS 2 deployments, scaling them to large, real-time robotic networks remains challenging due to inherent performance constraints that must be addressed to maintain operational efficiency.

Formal Verification and Safety: In ROS 2, formal verification and safety are pivotal for ensuring system reliability and compliance. Researchers employ formal methods—such as timed automata and privacy-centric graph analysis—to rigorously verify run-time safety, detect collisions, and guarantee the timely delivery of messages [

81,

82]. To address privacy concerns, privacy-protecting "sanitizer" nodes are integrated to filter or anonymize sensitive data, aligning ROS 2 systems with stringent compliance frameworks like GDPR. However, as verification efforts scale with system complexity, the resulting state-space growth and extended verification horizons can compromise real-time responsiveness, prompting ongoing research into more efficient, modular verification techniques that balance safety with performance.

Representative Equations and Overhead Considerations: Equations (

5)–() model aspects like attack probability, encryption overhead, security-induced latency, and detection probability across multiple intrusion detection modules:

These formulations underscore the trade-offs between strong security measures (encryption, access control, intrusion detection) and real-time performance constraints (latency, CPU usage).

4.3.2. RQ2 – Industry Trends and Real-World Deployments

Real-World Use Cases and Partial Deployments: Industry adoption of security, privacy, and safety features in ROS 2 remains fragmented. Many organizations still rely on default or minimal security settings, as robust encryption or blockchain-based logging can introduce latencies on the order of hundreds of milliseconds or add significant CPU overhead [

74]. Nevertheless, certain high-stakes environments (e.g., healthcare robotics, autonomous vehicles) are beginning to adopt advanced cryptographic or intrusion-prevention solutions to protect patient data or ensure collision-free navigation.

Use in Healthcare and Multi-Robot Collaboration: Healthcare robotics systems demand rigorous privacy protections for patient data while ensuring fault tolerance. Formal verification tools—such as those introduced by [

81]—are applied to critical tasks (e.g., surgical assistance) to prevent hazardous collisions or device malfunctions. Multi-robot fleets in industrial or logistics settings (e.g., automated forklifts, warehouse robots) demonstrate early implementations of access control frameworks (blockchain-based or ABAC) to restrict commands to authorized operators [

78].

Balancing Security and Real-Time Constraints: While advanced security is crucial for large-scale or safety-critical deployments, real-time system integrators often face overhead barriers. For example, selectively encrypting only mission-critical topics (rather than all topics) can substantially cut latency [

75], and advanced hardware-based approaches (TPM or secure enclaves) mitigate CPU overhead. However, such solutions are not yet widespread, indicating a cautious or partial adoption trend, especially among companies with legacy ROS 1 architectures or limited security expertise [

73].

4.3.3. RQ3 – Adoption Challenges and Future Solutions

Technical Barriers and Organizational Hurdles: Default ROS 2 configurations do not adequately secure large fleets, and the overhead of advanced security or blockchain frameworks remains high for many real-time workloads [

72]. The complexity of configuring role- or attribute-based access control, coupled with dynamic policy updates for multi-robot systems, frequently exceeds the skillsets of typical robotics teams. Meanwhile, formal verification remains computationally heavy once system topologies scale [

82].

Potential Solutions and Roadmap: Despite these obstacles, multiple paths forward exist. One promising solution is to implement selective or context-aware security measures, focusing on encrypting only the most sensitive topics and leveraging hardware accelerators such as TPM or HSM to reduce CPU overhead [

82]. In addition, large fleets demand robust, user-friendly tools for automated PKI and certificate management, facilitating key distribution, credential rotation, and the maintenance of cryptographic freshness [

78]. The development of evolving privacy graphs also offers a dynamic approach to tracking data flows as nodes change, ensuring compliance across fluctuating topologies. Finally, integrating intrusion detection tools—either by embedding IDP modules directly within ROS 2 distributions or via simple plugins—can help lower the barrier to real-time anomaly detection [

77].

Looking Ahead:Table 7 and

Table 6 summarize the key contributions, results, and open challenges. Future efforts to combine secure-by-default DDS configurations with lightweight intrusion detection, partial encryption, and formal safety checks may foster wider industry adoption. Nonetheless, bridging the gap between robust security guarantees and strict real-time performance remains an active research frontier—one that will likely require closer collaboration between robotics developers, security experts, and hardware vendors to achieve safe and privacy-compliant ROS 2 systems at scale.

4.4. Multi-Robot and Distributed ROS 2 Systems

4.4.1. RQ1 – Technical Foundations and Innovations

Masterless Architecture and Decentralized Discovery: In ROS 2, a significant departure from the ROS 1 master-based architecture is its embrace of a masterless design rooted in DDS, which enables decentralized discovery and flexible QoS configurations. This shift eliminates the single point of failure inherent in ROS 1, thereby enhancing fault tolerance and making the system more resilient in multi-robot or large-scale distributed deployments [

95]. Moreover, the masterless model allows nodes to dynamically join or leave the network without disrupting overall operations, which is particularly advantageous in unpredictable or variable network environments. However, while this decentralized approach offers greater scalability and robustness, it also introduces challenges related to managing network resources and maintaining consistent communication performance, especially under high-latency conditions or in lossy networks [

96].

Bridging, Co-Simulation, and Real-Time Coordination: Bridging, co-simulation, and real-time coordination are crucial components in facilitating seamless integration and operation across diverse robotic systems in ROS 2. Bridging solutions enable communication between ROS 1 and ROS 2 nodes—or even across different DDS/IoT layers—allowing for incremental migration and effective multi-robot coordination [

84,

86]. Co-simulation frameworks enhance this integration by combining physical system models with bridging logic, which helps manage challenges like system latencies, packet losses, and real-time QoS requirements [

85]. Moreover, many researchers are incorporating time-synchronized or velocity-aware bridging techniques to further reduce end-to-end latency, a critical factor in ensuring smooth and coordinated operation within distributed robotic swarms [

87].

Edge–Cloud Offloading and Specialized RMWs: In ROS 2, edge–cloud offloading and specialized RMWs serve as critical strategies for managing the computational and communication demands of distributed robotic systems. Offloading compute-intensive tasks, such as sensor fusion or large map building, to the edge or cloud can reduce a robot’s CPU usage by up to 40% [

59], thereby freeing local resources for real-time decision-making. However, this efficiency gain comes at the expense of increased network latency, which must be carefully managed to avoid compromising system responsiveness. Meanwhile, specialized RMW implementations like Zenoh are designed to perform well under challenging network conditions, such as in lossy or mobile environments, significantly enhancing communication reliability and overall performance in dynamic multi-robot settings [

93].

Equations and Algorithms: Typical formulas (Eqs. (

9)–()) model packet loss, overhead from offloading, and QoS balancing objectives. Algorithm 10 illustrates a velocity-aware adaptation that reduces latency and packet drops by dynamically tuning buffering windows.

|

Algorithm 10:Velocity-Aware Sliding Window in Multi-Robot Co-simulation. |

-

Require:

, netSimQueue Q, base window w, velocities

- 1:

Initialize

- 2:

while simulation not finished do

- 3:

- 4:

for each pair do

- 5:

- 6:

▹ Eq. () - 7:

Update netSimQueue Q with

- 8:

Evaluate , latency, throughput - 9:

end for

- 10:

end while |

4.4.2. RQ2 – Industry Trends and Real-World Deployments

Use in Large-Scale Industrial Fleets: Multiple industries, such as logistics, automotive manufacturing, and warehouse operations, integrate ROS 2 to orchestrate hundreds of robots or vehicles.

Hybrid bridging (ROS 1–ROS 2) remains common where legacy ROS 1 nodes must co-exist with new DDS-based systems [

57]. Edge or fog nodes in production lines aggregate real-time sensor data, offload compute workloads, and apply QoS balancing to maintain predictable cycle times [

88,

92].

Autonomous Vehicle and UAV Swarms: In autonomous vehicles, robust multi-sensor fusion demands high-throughput communication with minimal packet loss. Zenoh-based RMW solutions can outperform standard DDS in intermittent or wireless networks, such as UAV swarms operating over Wi-Fi or cellular links [

94]. Case studies suggest that carefully tuning DDS QoS (

KEEP_LAST,

RELIABLE) or leveraging co-simulation for mission planning can yield up to 30% lower latency [

85].

Integration with IoT and Cloud Platforms: ROS 2’s microcontroller-based integrations and bridging to IoT protocols (e.g., MQTT) facilitate real-time data collection in constrained devices [

89,

90]. Meanwhile, commercial cloud robotics frameworks (e.g., AWS RoboMaker, Microsoft Azure) use containerization and domain-partitioning approaches to host large multi-robot simulations or orchestrate distributed computational pipelines [

59,

91].

4.4.3. RQ3 – Adoption Challenges and Future Solutions

Technical Barriers: Despite demonstrable gains in scalability and resilience, several technical barriers impede full-fledged adoption. One significant challenge is discovery overhead; in large fleets of 50 or more robots, decentralized DDS discovery can become slow or inconsistent in high-latency networks [

95]. Additionally, complex QoS tuning poses a substantial hurdle. Advanced configurations required for network scheduling, velocity-aware bridging, and adaptive buffers are not well-documented for industrial contexts, making it difficult to optimize performance. Moreover, the coexistence of heterogeneous hardware—such as microcontrollers, GPUs, and specialized SoCs—introduces bridging overhead and concurrency issues, further complicating network management [

96].

Organizational and Standardization Gaps: Large-scale or cross-facility robotics programs often lack domain-specific guidelines for multi-domain discovery, hierarchical scheduling, or bridging best practices. Additionally, new RMW solutions like Zenoh are not yet officially standardized, causing reluctance among risk-averse enterprises [

93].

Proposed Solutions and Roadmap:Table 9 outlines key directions for addressing these barriers. One promising approach is the implementation of segmented DDS domains or hierarchical discovery mechanisms to effectively scale operations beyond 50 robots while reducing communication overhead. In parallel, developing adaptive QoS strategies for non-stationary networks—through on-the-fly reconfiguration or machine learning-based link-quality prediction—could further enhance network robustness. Moreover, the formal standardization of alternative RMWs, such as Zenoh, is essential for achieving robust adoption in heterogeneous systems. Finally, improving bridging efficiency for legacy and edge devices by leveraging lightweight bridging protocols or generating code that spans ROS,1 and ROS,2 stacks is critical to ensuring seamless integration across diverse hardware platforms.

Concluding Remarks: In summary, multi-robot and distributed ROS 2 systems can achieve significant gains in scalability, performance, and fault tolerance when carefully tuned. Edge–cloud offloading, velocity-aware bridging, and advanced QoS strategies each contribute to reducing latency and packet loss. Nonetheless, complexities in discovery, QoS tuning, and standardization remain obstacles for wider industrial deployment. Ongoing research on new RMW features (e.g., Zenoh) and next-generation capabilities (e.g., multi-domain discovery, hierarchical scheduling) is expected to shape the future of robust large-scale multi-robot networks in ROS 2.

4.5. Final Remarks

In summary, our exploration of ROS 2’s technical innovations and real-world deployments has addressed the core research questions driving this survey. Regarding RQ1, we have demonstrated how ROS 2’s enhanced middleware—including DDS-based communication, zero-copy techniques, and formal verification methods—provides significant improvements in performance, real-time execution, and security compared to ROS 1, while also highlighting persistent limitations in scalability and complexity.

For RQ2, this section has mapped emerging trends and industrial deployments across diverse domains—from autonomous vehicles and industrial automation to healthcare and multi-robot systems—illustrating both the transformative potential and the incremental nature of ROS 2 adoption.

Finally, concerning RQ3, we identified key technical, organizational, and standardization challenges that hinder rapid, widespread uptake, and proposed potential solutions such as standardized QoS profiles, integrated verification tooling, and streamlined bridging strategies.

Collectively, these discussions underscore the multifaceted evolution of ROS 2, setting the stage for further innovations and practical tool development.

7. ROS Database

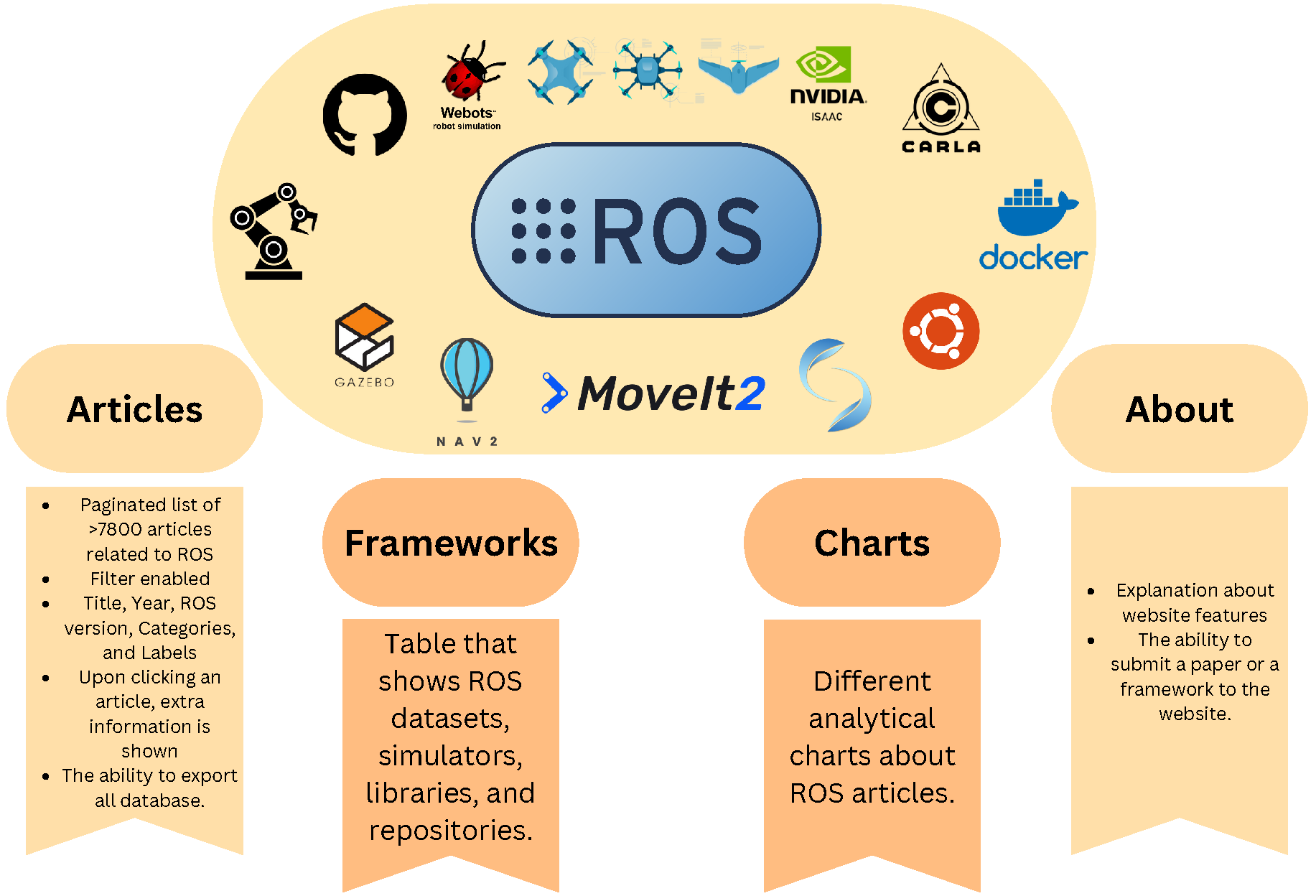

As part of this comprehensive survey on ROS 2, we have developed a dedicated

online database to centralize and analyze the growing body of ROS-related literature (

Figure 12). This platform goes beyond merely listing references—it enables rich

user interaction by supporting multi-level filtering, browsing, exporting, and community submission of both articles and frameworks. By offering dynamic visualizations and advanced search capabilities, the database allows users to identify key trends, understand industry-specific challenges, and explore innovative solutions in the adoption of ROS 2 across diverse fields such as autonomous vehicles, healthcare, agriculture, logistics, and industrial automation. In this section, we detail not only the data we have collected, but also

how users can interact with the database’s features to address these real-world application challenges outlined in RQ2.

7.0.0.20. 1) Articles Tab.

The database currently indexes 7,371 ROS-related articles, covering both ROS 1 and ROS 2. Users are presented with a paginated table where each entry displays the title, year of publication, and ROS version, along with detailed categorization that includes the category, subcategory, sub-subcategory, and various domain-specific labels such as UAV, dataset, self-driving car, or UUV. Additional metadata—like the abstract, DOI link, and GitHub repository when available—can be accessed on demand. A robust filtering and searching mechanism allows users to sort articles by year, category, platform type (e.g., UAV, UGV), or ROS version, facilitating the quick isolation of specific subsets, such as articles on ROS 2 combined with UAV swarms from 2022. For deeper insights, clicking an entry expands it to reveal key contributions, direct links to the paper, and any recorded notes regarding the experiments. Moreover, the export functionality enables users to download either the entire table or a filtered selection in CSV format, making it an excellent tool for meta-analyses or offline reference management.

7.0.0.21. 2) Frameworks Tab.

Another core feature is the aggregated Frameworks Tab, which compiles information on popular ROS frameworks, simulators, and libraries, as outlined in the schematic in

Figure 12. This table encompasses key ROS libraries—such as

Nav2,

MoveIt,2,

Rviz2,

PCL, and micro-ROS—as well as widely used simulators like Gazebo, Isaac Sim, Webots, and CARLA. It also features community packages from GitHub and curated ROS datasets, including examples like

GREENBOT [

263],

HawkDrive [

128], and

Swarm-SLAM [

269]. Each entry highlights the framework’s name, a brief description, its main domain focus, the corresponding GitHub link, and any relevant publications from our Articles Tab, providing users with a comprehensive overview of the ROS ecosystem.

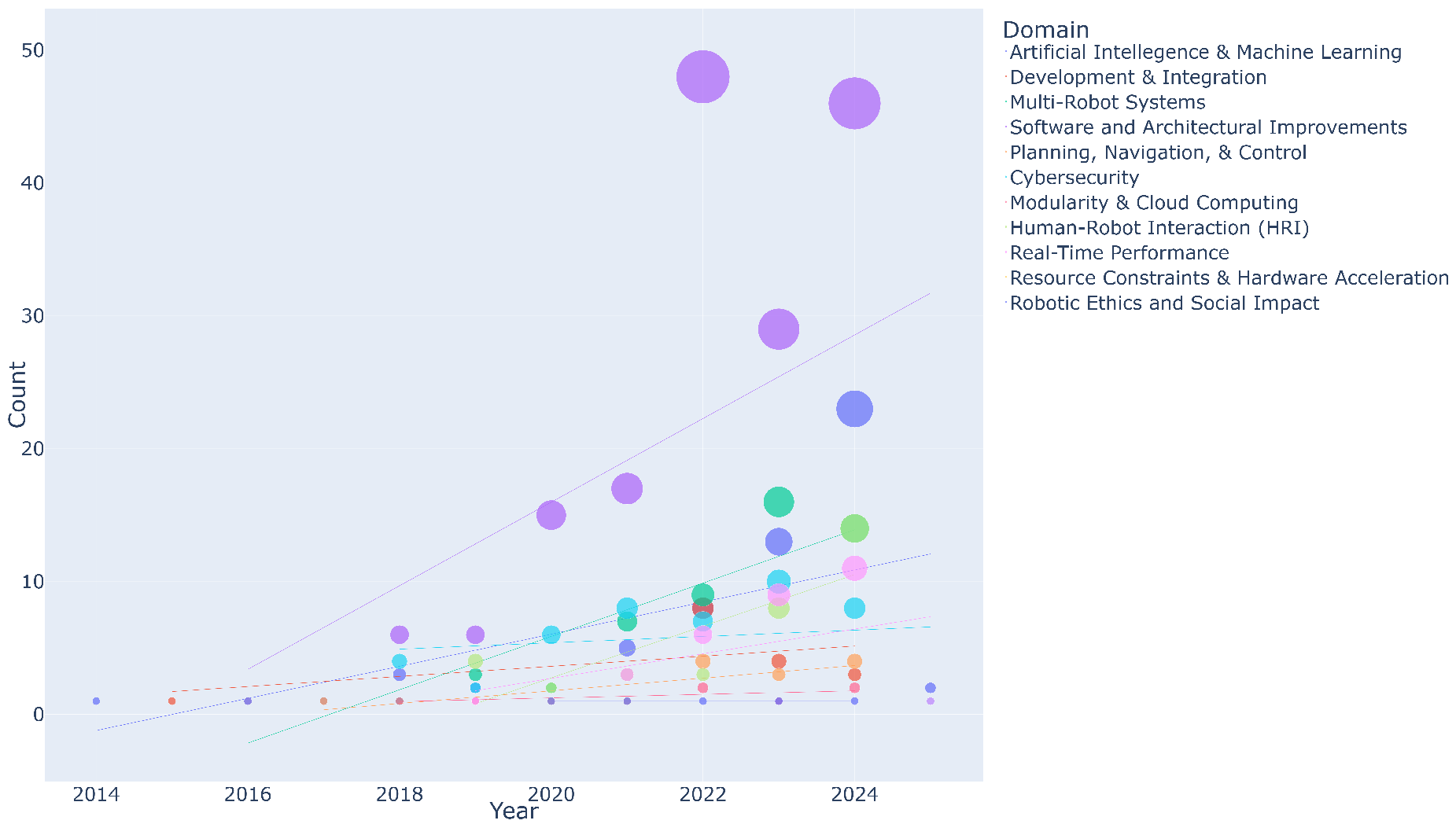

7.0.0.22. 3) Charts Tab.

The Charts Tab emphasizes the importance of visual analytics in understanding ROS research trends. It features a scatter plot that tracks publication counts over time, highlighting the yearly growth and the comparative usage between ROS 1 and ROS 2—as shown in

Figure 14. Additionally, a sunburst plot provides a detailed illustration of how ROS research is distributed across various sub-domains, such as Real-Time systems, Multi-Robot configurations, and Planning, mirroring the insights in

Figure 13. Complementing these, a bar chart outlines the different types of article contributions, offering users a comprehensive visual summary of the field’s landscape.

7.0.0.23. 4) About Tab.

Finally, the “About” section provides a comprehensive overview of the website’s features and additional resources. It offers a short explanation of functionalities such as article pagination, advanced filtering, interpretation of the frameworks table, and the usage of the various charts. Additionally, it details collaboration information regarding the survey’s creation, outlining the data-collection pipeline and the team behind the project. A user-friendly

submission portal is also available, enabling anyone to propose a new paper or framework by submitting metadata like title, year, relevant domain, and GitHub link, which is then reviewed by the curation team. Finally, the section includes explanatory plots that clarify the labels used in the first tab, as shown in

Figure 15.

7.0.0.24. Data Integrity and Growth.

With each new ROS 2 publication, we frequently update the database. Our curation pipeline scans major indexing services (IEEE Xplore, arXiv, MDPI, SpringerLink, etc.) for ROS-related papers, cross-checks with user submissions, and applies manual labeling. Thus, the database remains evolving—currently surpassing 7,371 entries (including both ROS 1 and ROS 2 works).

In summary, the online ROS database complements our survey by

facilitating direct engagement with the literature.

Figure 12 and the concept figures provided earlier illustrate how articles, frameworks, and analytics are interconnected for a seamless exploration of the ROS ecosystem.

8. Conclusion