1. Introduction

In pressurized water reactor (PWR) nuclear power plants, the secondary neutron source (Sb-Be) produces tritium after irradiation [

1]. Tritium is radioactive and highly permeable, posing significant hazards to operators and the environment by contaminating reactor coolant and leading to hydrogen embrittlement of structural materials. Controlling tritium permeation and leakage is an essential issue in evaluating the radiation environment in PWRs.

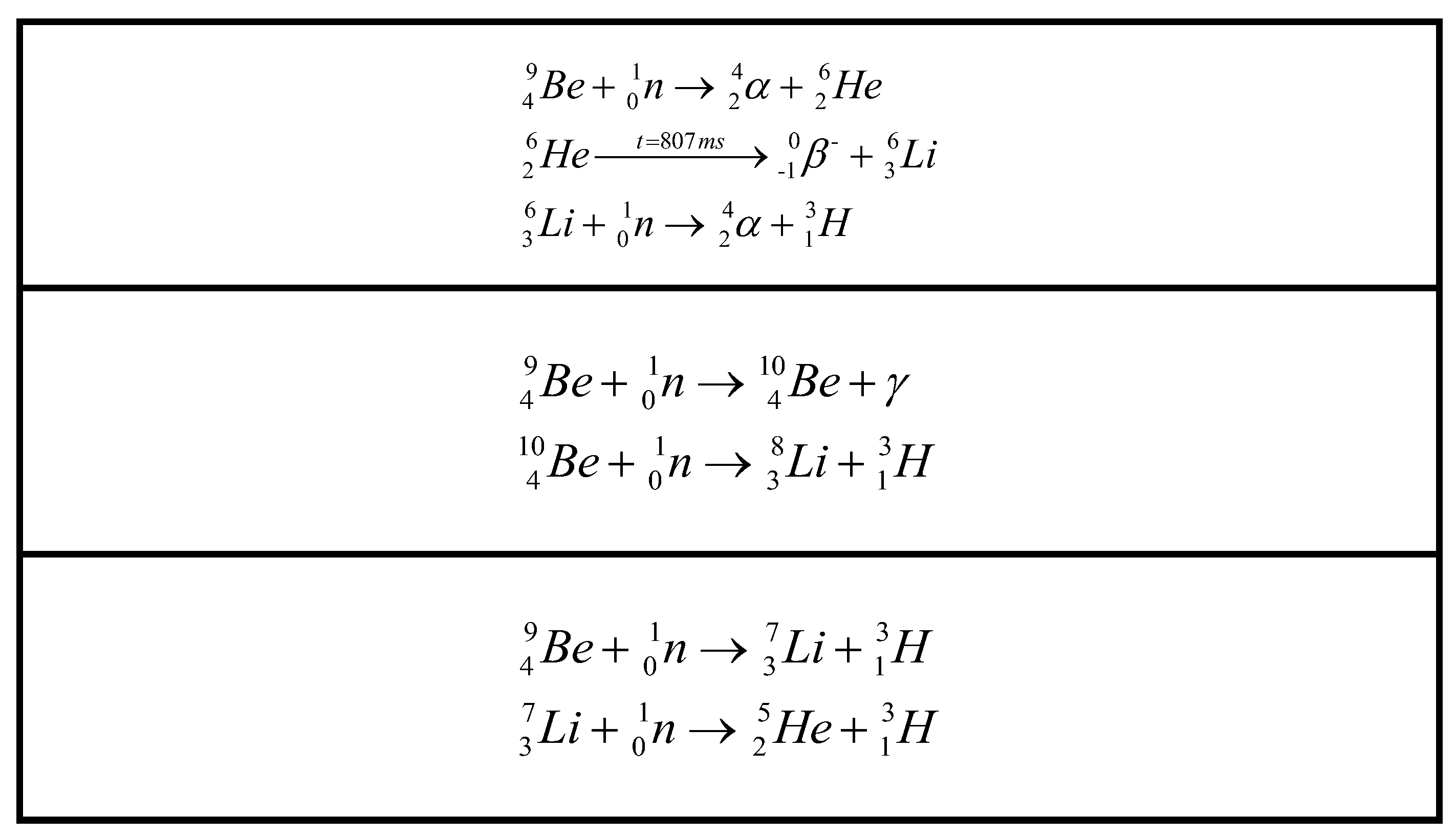

Tritium formation in secondary neutron source rods mainly occurs through three reactions, with the primary reaction occurring during reactor operation, as shown in

Figure 1. For a 900 MW power plant [

2] with a neutron flux of 3.5×10

14 n·cm

-2·s

-1 and neutron energy E ≥ 0.625 eV, each gram of Be in the core can produce approximately 2.47×10

12 atoms/s, including 2.30×10

12 helium atoms and 1.7×10

11 tritium atoms. Assuming all tritium remains in the rod, at the end of the secondary neutron source component's lifetime, the partial pressures of helium and tritium inside the rod could reach around 7 MPa and 0.5 MPa, respectively. However, in reality, the Sb-Be core cannot retain tritium, and the stainless steel cladding currently used allows high tritium permeability, leading to nearly all tritium produced by the Sb-Be core entering the coolant [

3]. In French 1300 MW and 1450 MW nuclear power plants, tritium from the secondary neutron source components accounts for about 20-40% of the tritium in the primary coolant system [

4]. Around 2000, the tritium produced by secondary neutron sources at Daya Bay accounted for approximately 10-20% of the annual emissions. Abnormal axial power shifts (AOA) in the core can also increase tritium production in secondary neutron source rods, as the axial power peak shifts towards the bottom, where the secondary neutron sources are located, resulting in increased tritium generation proportional to the neutron flux in the core. Implementing effective measures to trap tritium within the secondary neutron source rods is a viable strategy to reduce tritium release.

Tritium permeates by diffusion in the form of interstitial atoms and is able to pass through almost all metals with high permeability. Tritium permeability increases with increasing temperature and neutron flux. The permeability of hydrogen isotopes (hydrogen, deuterium, and tritium) in stainless steel at temperatures greater than 400℃ is 2 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than at room temperature. In addition, the permeability of stainless steel under irradiation in the reactor will be higher than that measured under the same temperature and pressure conditions in off-heap tests. For example, experimental results for 304 stainless steel indicate that at 570 °C, the permeability under irradiation conditions is three times higher than that under non-irradiation conditions [

5]. The slow growth of the oxide layer on the surface of stainless steel will lead to a decrease in permeability. For example, under irradiation conditions, a 0.01 vol.% oxide layer on 0.12C-18Cr-10Ni-Ti can reduce its permeability by around 100 times [

6]. The permeability of 316 stainless steel inside the stack is approximately 2 to 5 times higher than the permeability measured in external tests [

7].

Coating structural materials with a TPB layer of sufficient thickness, low tritium diffusion coefficient, and low surface recombination constant is one of the most effective practical methods to reduce tritium permeation while preserving the overall properties of the structural materials. The tritium permeation capability of a coating is generally evaluated using the PRF (tritium permeation reduction factor), defined as the ratio of tritium permeability in the substrate material to that in the coated substrate. A higher PRF indicates stronger tritium-permeation resistance. Al

2O

3 coatings are considered important candidates for tritium-permeation barriers due to their high PRF (up to 2-4 orders of magnitude) [

8], ease of preparation, and corrosion resistance. However, differences in thermal expansion coefficients between the substrate and coating materials can cause aluminum oxide coatings to peel off, posing a significant technical challenge. This can be addressed using composite coatings (e.g., Al

2O

3/FeAl, Al

2O

3/TiC, Al

2O

3/Cr

2O

3, Al

2O

3/SiC, Al

2O

3/TiB

2), which improve adhesion to the substrate, provide effective stress relief, and exhibit self-healing capabilities for microcracks. These enhancements increase the coating's resistance to spalling and introduce tritium diffusion traps, thereby improving tritium permeation resistance.

Aluminide coatings have been widely used as anti-corrosion coatings in conventional industries and the preparation techniques are well established. K. Stein [

9] prepared aluminide coatings on MANETs using the liquid hot dip aluminium technique to prepare aluminising coatings on MANET, obtaining hydrogen PRFs of 260-1000 at 300-470 °C. Benamatic [

10] prepared aluminized coatings on MANET using solid aluminizing technique and obtained hydrogen PRF of 2500~5000 °C in 400~500 °C. Fazio [

11] prepared aluminide coatings on MANET surfaces using spraying, low pressure plasma sputtering, and air plasma sputtering, respectively, with hydrogen PRFs of 1-3 orders of magnitude in the range of 350-500 °C. A. Perujo [

12] prepared aluminide coatings on MAET II using vacuum plasma sputtering with hydrogen PRFs of 2-3 orders of magnitude at 300~550 °C. Forcey [

10] prepared aluminide coatings on 316L and DIN 1.4914 by solid aluminising and obtained hydrogen PRFs of 2-4 orders of magnitude at 300~500 °C. Liu Xingzhao [

13] obtained PRFs of 300~400 after TiN plating on HR-1 by CVD. Forcey [

8] prepared TiN/TiC and Al

2O

3/TiN/TiC composite coatings on 316L surface by CVD method and found that the PRF of deuterium is only one order of magnitude at 250~450 °C. While Shang Changqi [

14] found the PRFs of TiC monolayer film and TiN+TiC composite film prepared on 316L surface by CVD method are 5~6 orders of magnitude at 200~600 °C. Yao Zhenyu [

15] prepared TiN+TiC+TiN and TiN+TiC+SiO₂ composite films on 316L stainless steel, wthch have the PRF of 4~5 and 4~6 orders of magnitude respectively at 200~600 °C, using the physical vapor deposition (PVD) method.

Zirconium-based alloys are also widely used in hydrogen storage and purification systems due to their strong affinity for tritium. Tritium formed from fuel fission is nearly entirely sealed in the fuel cladding as hydride, with only about 0.01% of tritium eventually leaking from nuclear power plants [

4]. Studies by Song Jiangfeng et al [

16] showed that Zr

2Fe alloy powder has a hydrogen absorption capacity of about 32% under 300°C and 1 bar conditions with a 2.5% H

2/Ar mixture. In 2000, the US Department of Energy designed a Tritium Producing Burnable Absorber Rod (TPBAR) using zirconium alloys as tritium-absorbing materials in 17×17 fuel assemblies [

17]. However, mature studies on the use of treated zirconium-based alloys as secondary neutron source tritium barriers in PWR environments are lacking. The impact of irradiation dose on the tritium-permeation performance of coatings or zirconium-based alloys, given the long service time of secondary source rods in reactors, is crucial for their application.

This study evaluates and selects tritium-permeation barriers with excellent performance through a series of tests on Cr2O3/Al2O3 coatings and zirconia. It examines the tritium-permeation performance of 316L stainless steel Cr2O3/Al2O3 coatings and zirconium alloy self-oxidation films before and after irradiation. The influence of factors such as irradiation, temperature, and deuterium partial pressure on the tritium-permeation performance of the coatings and oxidation films is assessed. Based on experimental results, the tritium-permeation behavior of coated stainless steel tubes and pre-oxidized zirconium alloy tubes is simulated, identifying key factors affecting the materials' tritium-permeation resistance.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Irradiation Tests

The tests primarily used an HVE 3MV tandem accelerator. Gold ions were chosen for irradiation because they are chemically inert and do not react with the material. Additionally, the concentration distribution and damage region of gold ions differ slightly near the surface, causing minimal impact on material composition. Using ions like Fe or Al, which are present in the material, for irradiation would interfere with microstructure and composition analysis and have a more significant impact on the material's phase structure, differing from actual neutron irradiation conditions, thereby not effectively simulating or evaluating the impact of neutron irradiation damage on the coatings, the test parameters are shown in

Table 1.

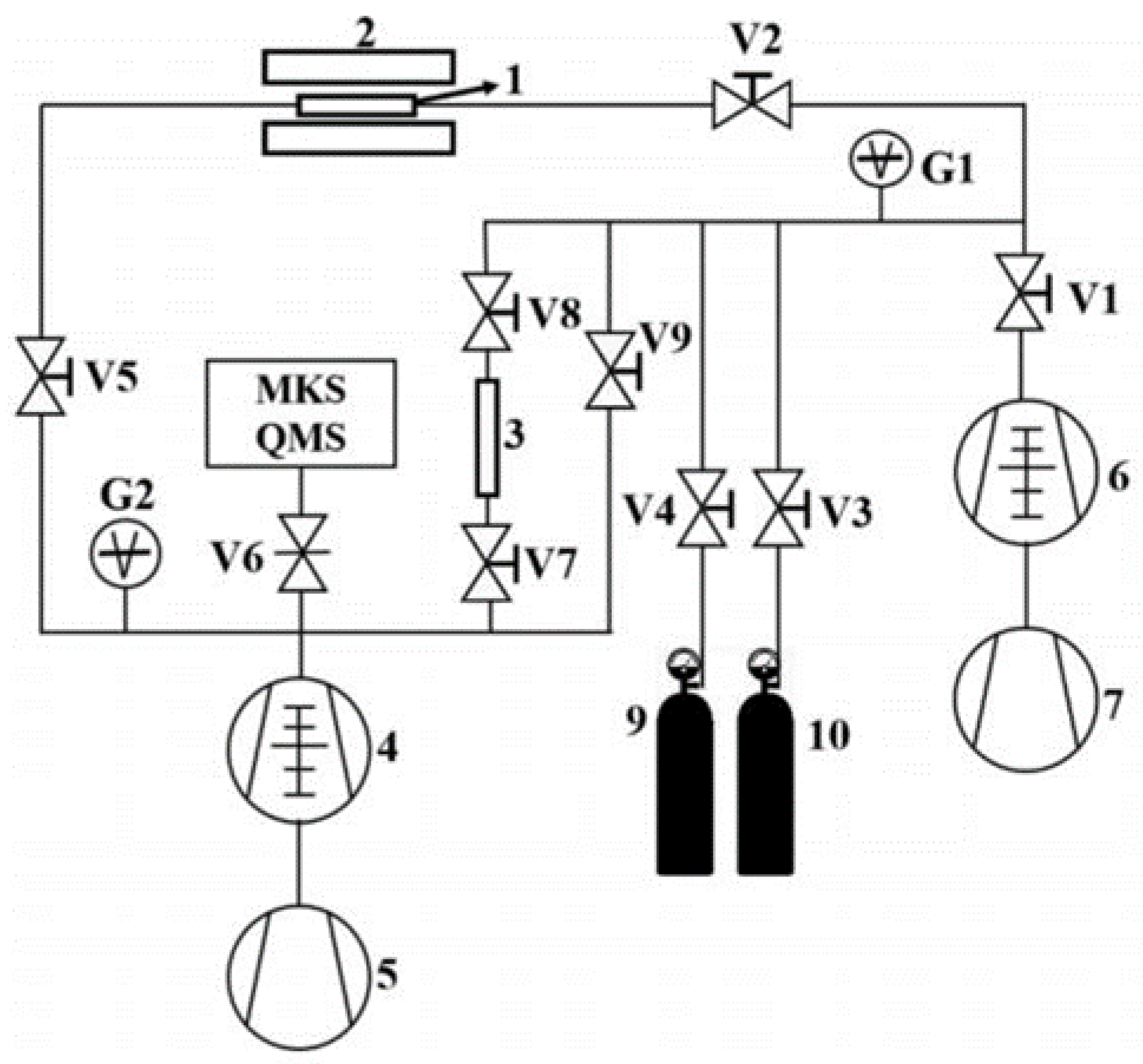

2.2. Gas Hydrogen Isotope Permeation (GDP) Test

Deuterium is used for permeation experiments. The structure of the experimental device used in this experiment is shown in

Figure 2.

The deuterium permeation test conditions for the coatings after irradiation are shown in

Table 2. At least one sample of each coating type is prepared for the permeation test under each set of irradiation parameters.

2.3. Microstructure Inspection

Microstructural analysis of the specimens before and after irradiation was carried out using FIB/TEM or SEM techniques. By correlating the lattice parameters, the information regarding dislocation densities was obtained, and precipitated phase structures, pore morphology, pore size distributions, and the total number of pores of each sample were counted within the measurement ranges.

FIB sample preparation was conducted using the FEI Helios NanoLab 600i equipment. The typical thickness of samples prepared by FIB is around 5 μm. The two advanced TEM devices FEI Talos F200X and FEI Tecnai G2 F20 were used to the microstructural analysis. To mitigate the risk of sample damage due to traditional mechanical polishing, all specimens intended for TEM analysis were prepared using FIB milling techniques, ensuring the samples met the required criteria for TEM examination.

The two TME devices were also employed to conduct high-resolution and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) analyses. These techniques enabled an in-depth characterization of the microstructure of irradiated coatings. The analyses provided detailed insights into features such as dislocations, phase distributions, and crystallographic orientations post-irradiation, thereby allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the material's properties and behaviors under irradiation conditions.

The surface and cross-section microstructure or topography of some samples were characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEEM) model Thermo Scientific Apreo 2c.

2.4. Nanoindentation Inspection

Nanoindentation tests were conducted on the samples before and after irradiation to assess the impact of irradiation on the mechanical properties of the coatings, specifically focusing on adhesion performance. the Nano Indenter G200 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used.The indenter used for the tests was a Berkovich diamond tip. The nanoindentation experiments employed two modes: Continuous Stiffness Measurement (CSM) and static mode.

The calculation of nanohardness was based on the Oliver-Pharr method, which allows for the determination of hardness and elastic modulus from the load-displacement data collected during the indentation process. To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the experimental results, each sample underwent multiple measurements (≥3 times) to assess the nanohardness values. This systematic approach helped to evaluate the impact of irradiation on the mechanical properties, particularly the adhesion strength of the coatings.

Figure 1.

Equations for tritium generation in the secondary neutron source rod.

Figure 1.

Equations for tritium generation in the secondary neutron source rod.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of deuterium permeation testing system: 1-Sample, 2-Furnace, 3-Standard Leak, 4-Ultra-high Vacuum System, 5-Mechanical Pump, 6-High Vacuum System, 7-Mechanical Pump, 9~10-Gas Cylinder, V1~9-Valves.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of deuterium permeation testing system: 1-Sample, 2-Furnace, 3-Standard Leak, 4-Ultra-high Vacuum System, 5-Mechanical Pump, 6-High Vacuum System, 7-Mechanical Pump, 9~10-Gas Cylinder, V1~9-Valves.

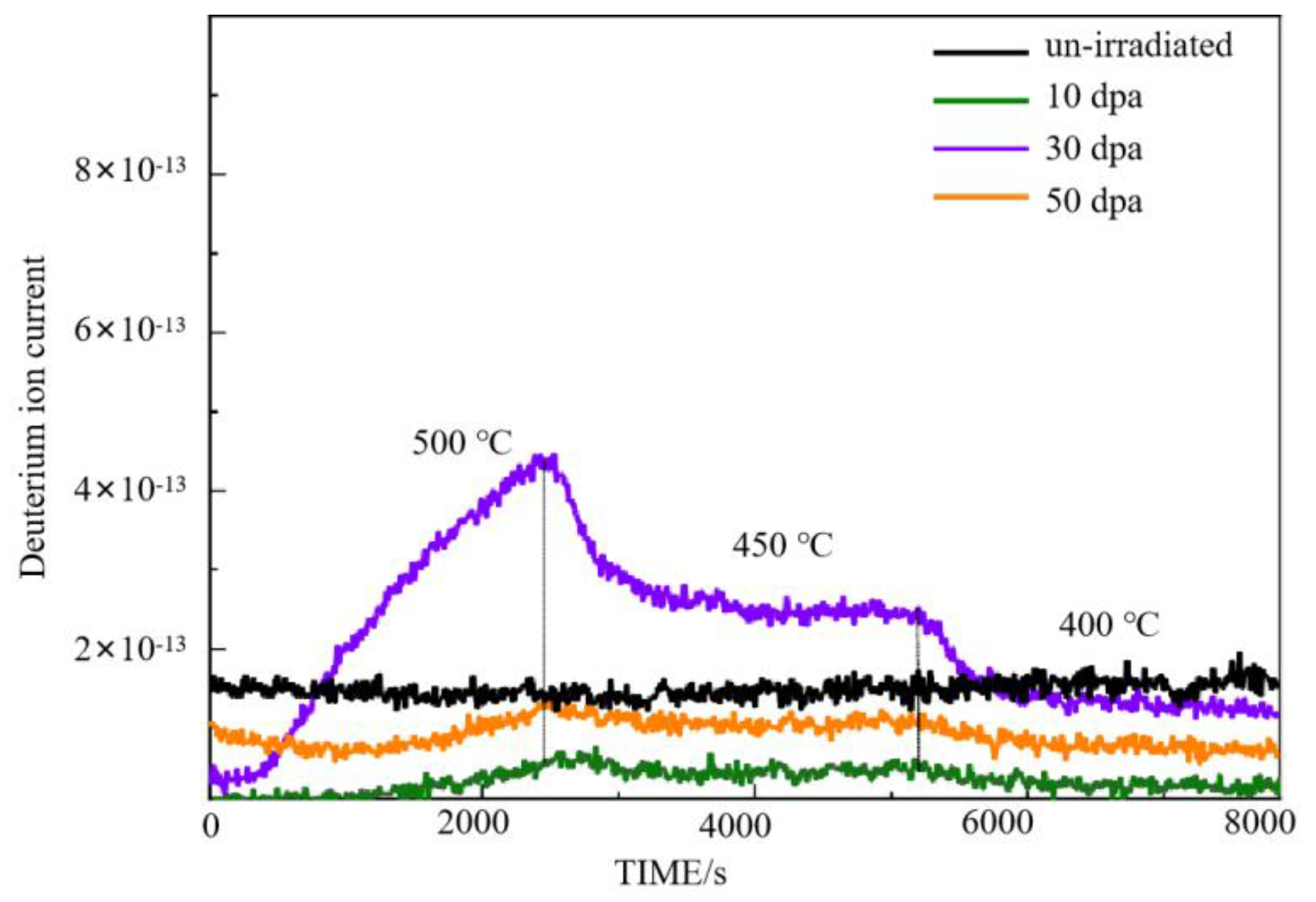

Figure 3.

Deuterium permeation curve of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composition coating after irradiation.

Figure 3.

Deuterium permeation curve of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composition coating after irradiation.

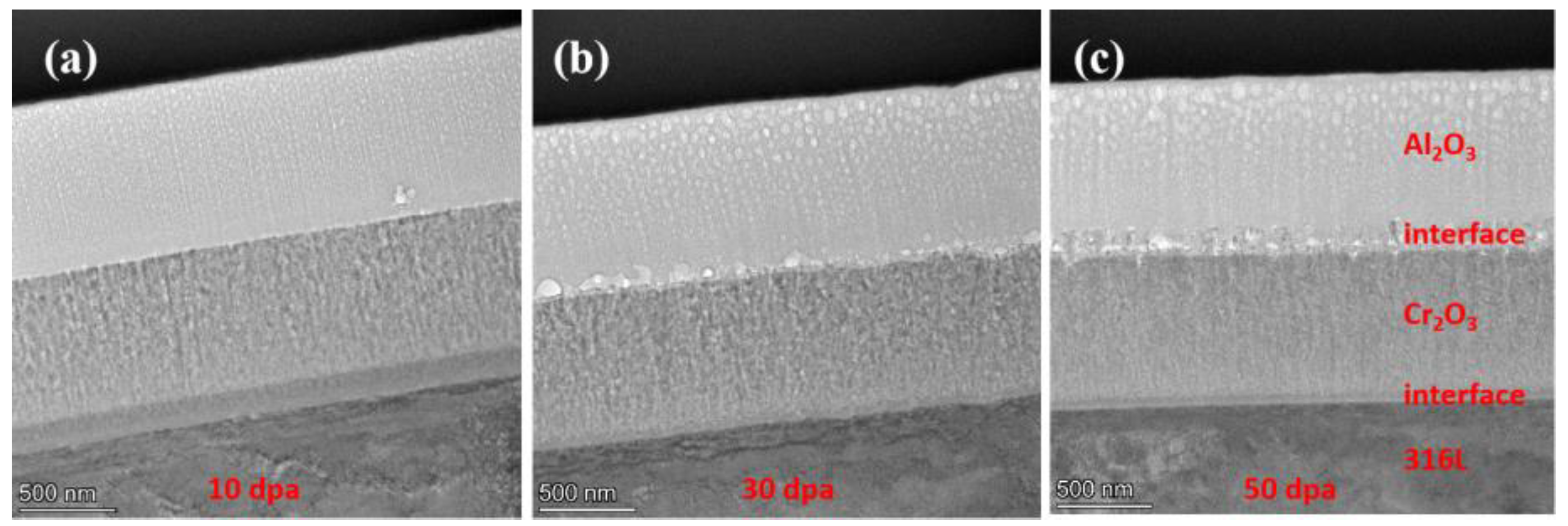

Figure 4.

Cross-section SEM image of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite coating.

Figure 4.

Cross-section SEM image of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite coating.

Figure 5.

Surface SEM image of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite coating.

Figure 5.

Surface SEM image of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite coating.

Figure 6.

Cross-section EDS image of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite coating.

Figure 6.

Cross-section EDS image of Cr2O3/Al2O3 composite coating.

Figure 7.

TEM cross-section image of irradiated coating and corresponding selected-area EDP: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Figure 7.

TEM cross-section image of irradiated coating and corresponding selected-area EDP: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Figure 8.

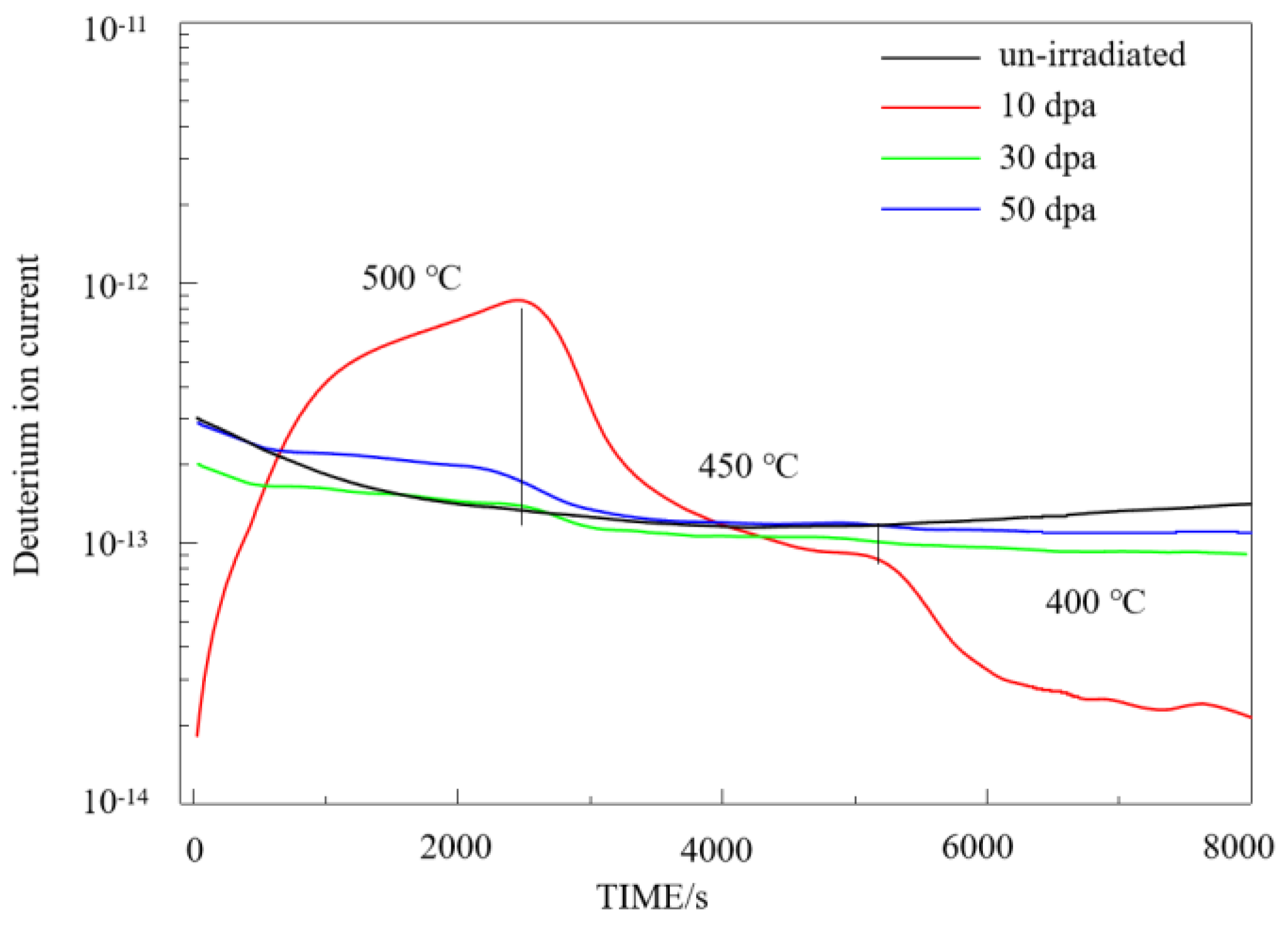

Deuterium permeation curve of irradiated pre-oxidation zirconium alloy.

Figure 8.

Deuterium permeation curve of irradiated pre-oxidation zirconium alloy.

Figure 9.

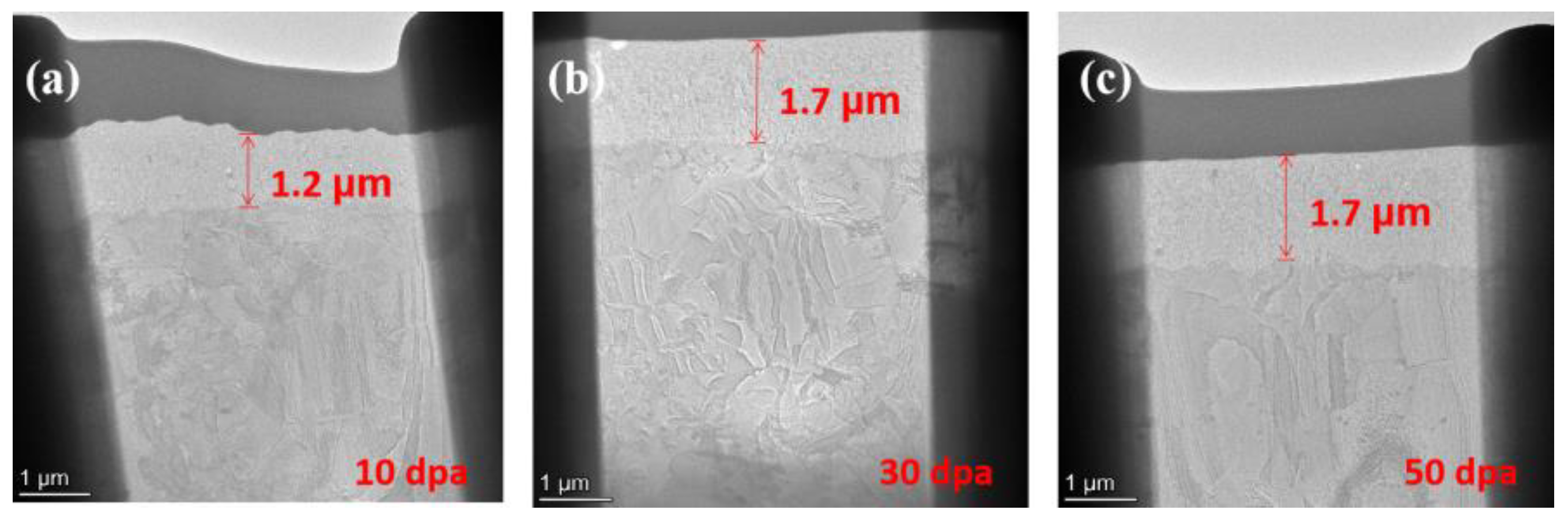

Cross-section SEM of pre-oxidation layer: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Figure 9.

Cross-section SEM of pre-oxidation layer: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Figure 10.

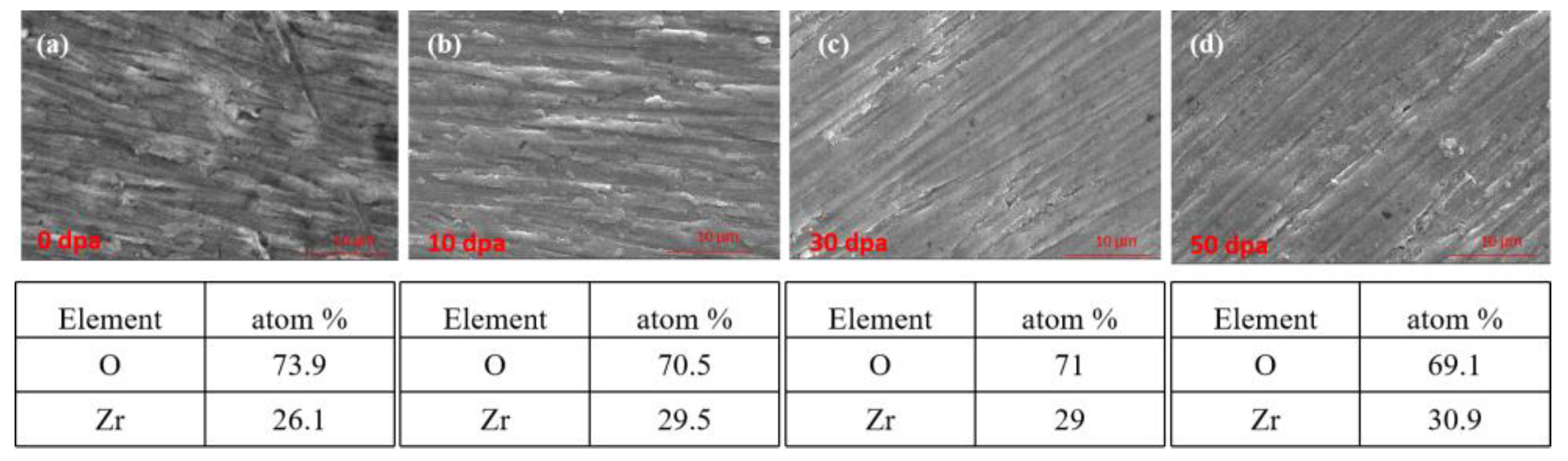

Surface SEM of pre-oxidation layer: (a) 0dpa, (b) 10dpa and (c) 30dpa (d) 50dpa.

Figure 10.

Surface SEM of pre-oxidation layer: (a) 0dpa, (b) 10dpa and (c) 30dpa (d) 50dpa.

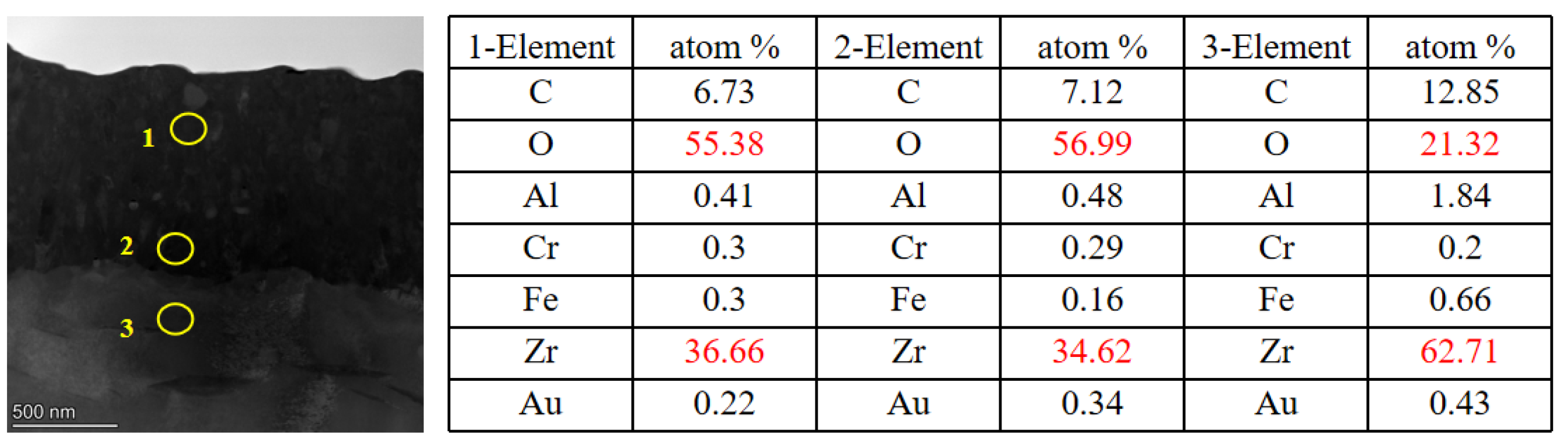

Figure 11.

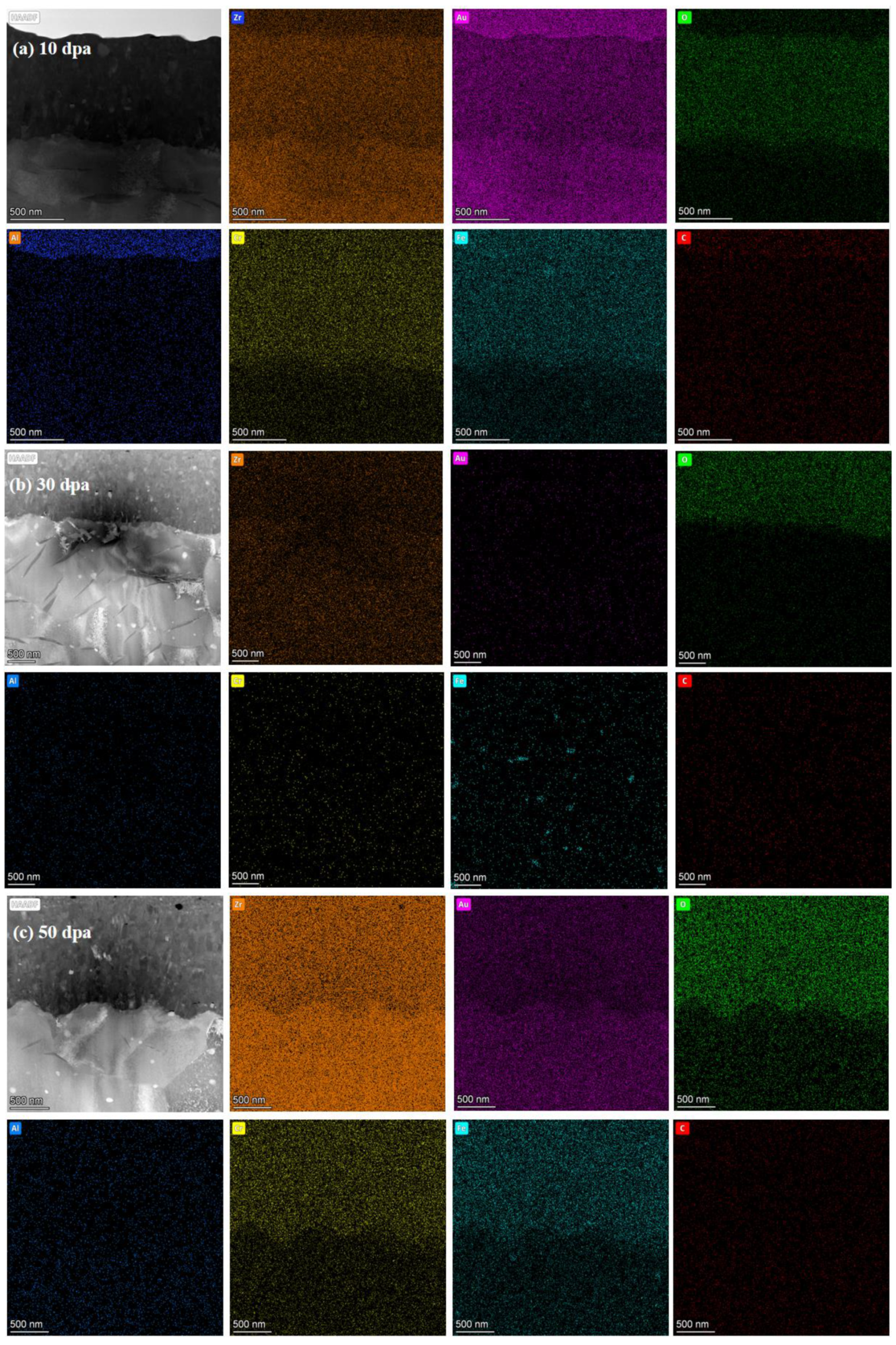

Cross-section EDS of pre-oxidation layer: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Figure 11.

Cross-section EDS of pre-oxidation layer: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

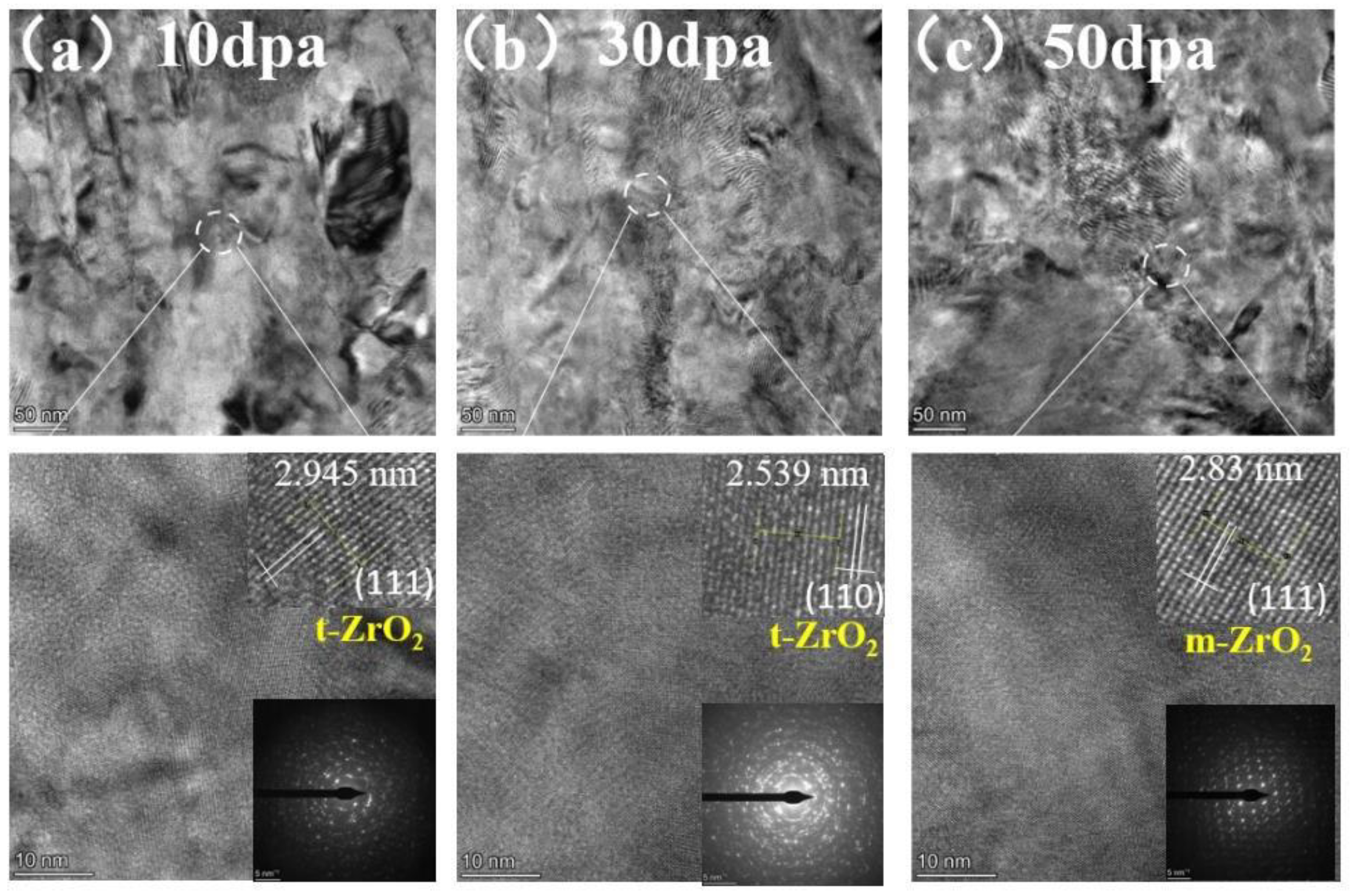

Figure 12.

TEM cross-section image of irradiated pre-oxidation layer and corresponding selected-area EDP: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Figure 12.

TEM cross-section image of irradiated pre-oxidation layer and corresponding selected-area EDP: (a) 10dpa, (b) 30dpa and (c) 50dpa.

Table 1.

Ion irradiation experimental parameter for coating samples.

Table 1.

Ion irradiation experimental parameter for coating samples.

| Ion type |

Irradiation temperature |

Radiation damage dose |

Particle beam flow parameters |

| Au |

450 °C |

10dpa, 30dpa, 50dpa |

Beam type: scanning beam mode; Beam half-height width: 1mm; Scanning area: 5cm x 5cm; Scanning frequency: 1kHz; Beam current inhomogeneity: <1%; Irradiation damage dose: real-time monitoring |

Table 2.

Deuterium permeation testing condition.

Table 2.

Deuterium permeation testing condition.

| Temperature |

Pressure |

| 500 °C |

100kPa |

500kPa |

| 450 °C |

100kPa |

500kPa |