This section will further explore the mental experience brought to people and the spiritual realm they are led into based on previous formal analysis of the image Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting. Combining the composition of the mural with different viewing perspectives, the second part of this section also discusses how Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting engages with the viewers through composition, thus constructing a realistic, vivid, divine, and vast realm of the Buddhas.

4.1. Spiritual Landscape Constructed by the Coexistence of “Three Religions in One”

The preaching Shakyamuni is one of the eight phases of Shakyamuni Buddha’s “Eight Phases to Realization” (Deng 2022). In his article, Deng mentioned that the beginning of the Avatamsaka Sutra describes in detail the solemn and glorious appearance of Shakyamuni presiding over a grand assembly, preaching to the Bodhisattvas, Vajrapanis, and various deities in a magnificent background (Deng 2022). The theme of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting is inspired by the preaching scene of Shakyamuni Buddha described in the Sutra, integrating elements of Tibetan Buddhism, Han Buddhism, and Taoism within its unique historical context. The splendid appearance of Shakyamuni Buddha in the Avatamsaka Sutra can only be realized through the heart, not simply with eyes. However, Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting expresses this invisible gathering in a visible form, solidifying the profoundness and intricacy of this magnificent scene in a way that transcends time and space. Thus, what has originally been invisible to the mortals has been reproduced as a glorious moment that can be admired by generations to come. Through the interaction between the artist, the physical image, and the audience of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, a spiritual landscape is constructed----a field of high energy flows, a harmonious blend of truth and secularism, a realm embracing diversity and equality of all beings, and a path that leads to the highest state of realization.

To begin with, the physical image of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting conveys a high-energy state that can be passed on to all its viewers, as the flow of dynamic lines throughout the image creates a powerful sense of liberation, as if inviting viewers to take part in a spiritual elevation. The artist has structured the whole picture with smooth and dynamic lines that seem light and soft but are full of strength. These lines carry the flow of spirituality within them and fill the entire space with endless flows of energy that start from nowhere, thus bringing the viewers into a supernatural space together with the divine figures. This intangible flow of energy that emanates from within the image allows viewers to feel a powerful surge of energy penetrating through their minds and bodies. This is a miraculous process of energy transmission from mind to mind, as viewers are not simply seeing the physical image with their eyes, but also intuitively feeling the spiritual resonance with Shakyamuni Buddha’s state of mind. When seeing the mural at first glance, the viewers may not systematically identify all the figures that are depicted, not to mention whether they are from Han Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, or Taoism. However, they are immediately enveloped by a solemn yet peaceful and harmonious atmosphere just by looking at the entire composition. It is through the coordination and mixture of various visual factors such as facial expressions, attires, decorations, dynamics, colors, and composition that the image is able to convey this highly energetic state of mind at a glance, opening up the minds of devout believers to the state of awareness which leads them to the point of enlightenment where they can commune with the Buddha.

Additionally, according to Deng's interview with a Buddhist in his article, different figures in Buddhism such as Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Arhats, etc., indicate the different states of life and the level of enlightenment of Buddhists. In Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, different figures of Buddhism convey different messages about their state of enlightenment. For example, the Buddha Shakyamuni and the surrounding Bodhisattvas display the highest state of enlightenment through their dignified and serene portraits, while the Taoist thunder gods above them show expressions of surprise, severity, or intimidation on their faces, which reflect a slightly lower level of enlightenment. The artist intentionally portrayed these different states of enlightenment when creating the mural, allowing viewers to resonate with their own spiritual states and find reflections of their inner selves within the image whether they are Buddhists or not.

Secondly, the image of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting demonstrates a harmonious blend of truth and secularism throughout its spiritual topography. The concept of "harmonious integration", commonly known as “Yuan Rong” in Chinese, is a unique concept in Chinese Buddhism. It describes a state of mutual dependence and harmony between things (Chen 2004), representing the great wisdom of the Buddha (Liu and Hu 2009). "Truth" refers to the absolute, transcendent world of Buddhism relative to the materialistic mundane world, whereas " secularism" corresponds to the worldly rules and desires that arise in reality. Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting is created by artists of various cultural backgrounds who may not have directly witnessed or experienced the events depicted in the Sutras. However, since art is made by the people and art comes from life, the various visual depictions of the Buddha’s assembly are also reflections of the different artists, sponsors, regions, cultural environment, society, and even politics in the specific periods in history when they were created, thus offering a visual insight to the rich tapestry of human experiences. These cultural and societal influences shape artists’ perceptions of such sacred events and thus the experience of the viewers through constructing a culturally specific image of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting. For example, the opulent and elaborate depictions of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Heavenly Kings, and other deities in the mural are representations of the religious assembly embedded with traces of the popular worldly aesthetics of its own historical background. The assembly of deities appears exceedingly luxurious, with embellishments resembling those made for royalty, presumably crafted to meet the expectations of the Mu family and aristocrats from other relevant cultures. However, this is not the true intent of Buddhism. The real intent of Buddhism is to help people approach the truth after showing them the impermanence of the mundane world. In Deng’s interview, the Buddhist tells us that Buddha represents an infinite state, and when he seeks to enlighten others, he does so based on the other person’s state of mind, manifesting an image of wealth and glory merely to show people’s worldly desire, but ultimately teaching them that wealth is not endurable, thus leading them to the path of enlightenment (Deng 2022). In Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, the image of Shakyamuni Buddha exudes an ethereal serenity, free from desire and thoughts after realizing the insight of the mundane world, which approaches the true essence of the awareness of the Buddha. The overall image captivates and overwhelms the viewer with its display of worldly splendor, while more importantly, it subtly conveys a profound, serene, powerful, eternal, and constant message behind the grand exterior scene. This is how the worldly aspects of Buddhism blend perfectly with the realm of truth that is behind the scene of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting. From another perspective, the image also reflects the attitude of the Mu family who sponsored the murals during its governance. The Mu family stayed devout to Tibetan Buddhism while being loyal to the Ming Dynasty and following the norms in Han culture, thus perfectly combining religious beliefs with their political strategy, which is also, in a sense, the "harmonious integration of truth and conventional reality".

Thirdly, within the context of the integration of Tibetan Buddhism, Han Buddhism, and Taoism, the creation and viewing of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting also constructs the Buddhist vision where "all beings are equal" and "all beings possess the nature of Buddha" (Yang 2005). When viewers from different cultural and religious background view Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, what they construct in their minds is a scene of the harmonious coexistence of the three religions, collectively engaging in a grand gathering for meditation and enlightenment. Terms such as “race” or “heterodoxy” have never found a foothold in Chinese culture, as Chinese Buddhism upholds the belief that all living beings possess Buddha nature and can become Buddhas, embracing the notion of "equality of all beings”. Consequently, followers of Han Chinese Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Taoism can all become Buddhas; everyone is a future Buddha, a potential Buddha. Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting guides people to a broad vision where all beings possess Buddha-nature, a spiritual realm filled with light and hope, where Buddha is there to deliver all sentient beings universally from torment. This allows every viewer, regardless of their differences, to progress on the path to Buddhahood at their own pace, whether fast or slow, directly or indirectly. Similarly, artists from different cultural backgrounds who co-created the mural must also have built such a wonderful vision of equality and harmony among all beings, sharing the practice towards enlightenment through their collaboration, exchange of ideas, and the intersection of their brushstrokes.

Finally, according to Huang Shishan's book Illustrating the True Form: The Visual Culture of Traditional Chinese Taoism, this section is also inspired by the intriguing idea of "image as text." According to Huang, images resemble a form of writing, and the "viewing" of images is also a way of decoding texts (Huang 2022). Within Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, every line, every piece of color, every drifting cloud, and every depiction of a deity seem to be the heavenly letters or characters coming from a divine celestial script, like cloud patterns condensed from the lively cosmic spirits at the beginning of the universe. These "cosmic scripts", to which the images in Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting correspond, possess their own spatial dimensions in the universe that can only be perceived spiritually. This spiritual landscape constructed by Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting is a "text" written in the spiritual realm that can be read by both the artist and the audience, embodying the essence of the universe and leading all beings into meditation and enlightenment.

Overall, the objective visual images in Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting and the spiritual images constructed by people are interrelated and merged, corroborating each other constantly. "An image is what it is expected and seen to be” (Huang 2022). From the painter's perspective, the existence of the physical image relies on their imagination and mental experience, thus the spiritual imagery constructed by the painter is faithfully reflected in the painting. From the viewer's perspective, the two-way communication between the physical image and the viewer enables the viewer to generate a spiritual landscape that engages in a dialogue with the painter’s spiritual image. Although the physical image of Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting is based on textual descriptions in the Sutra, it also reproduces a "cosmic script" of its own independent existence through the interaction between the artist, the mural, and the audience, constructing a spiritual landscape where enlightenment is attained through the flow of energy, the unity of truth and the mundane, and the inclusive vision of all lives being equal.

4.2. Interactive Relationship Between Composition and Viewing Perspective

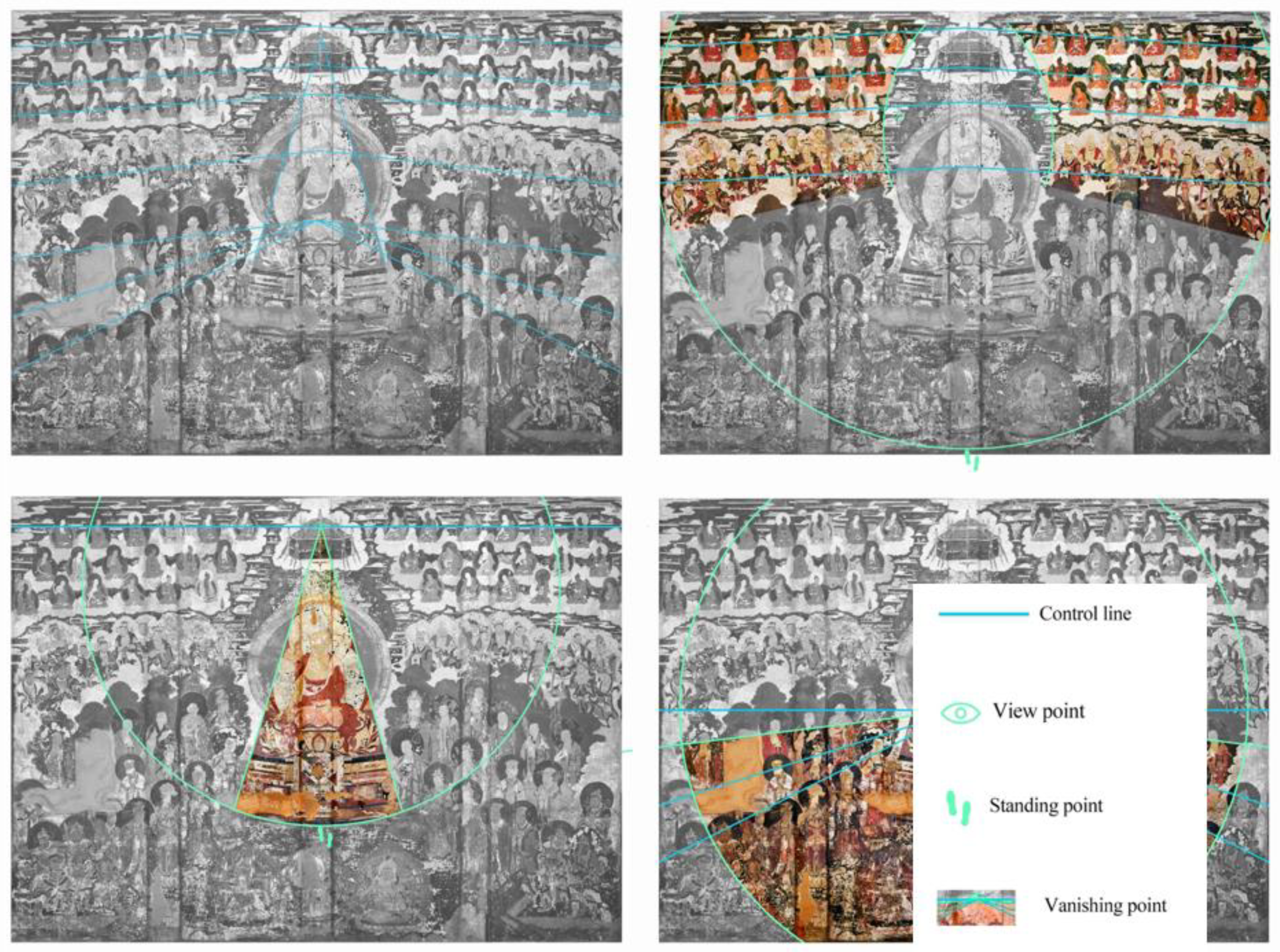

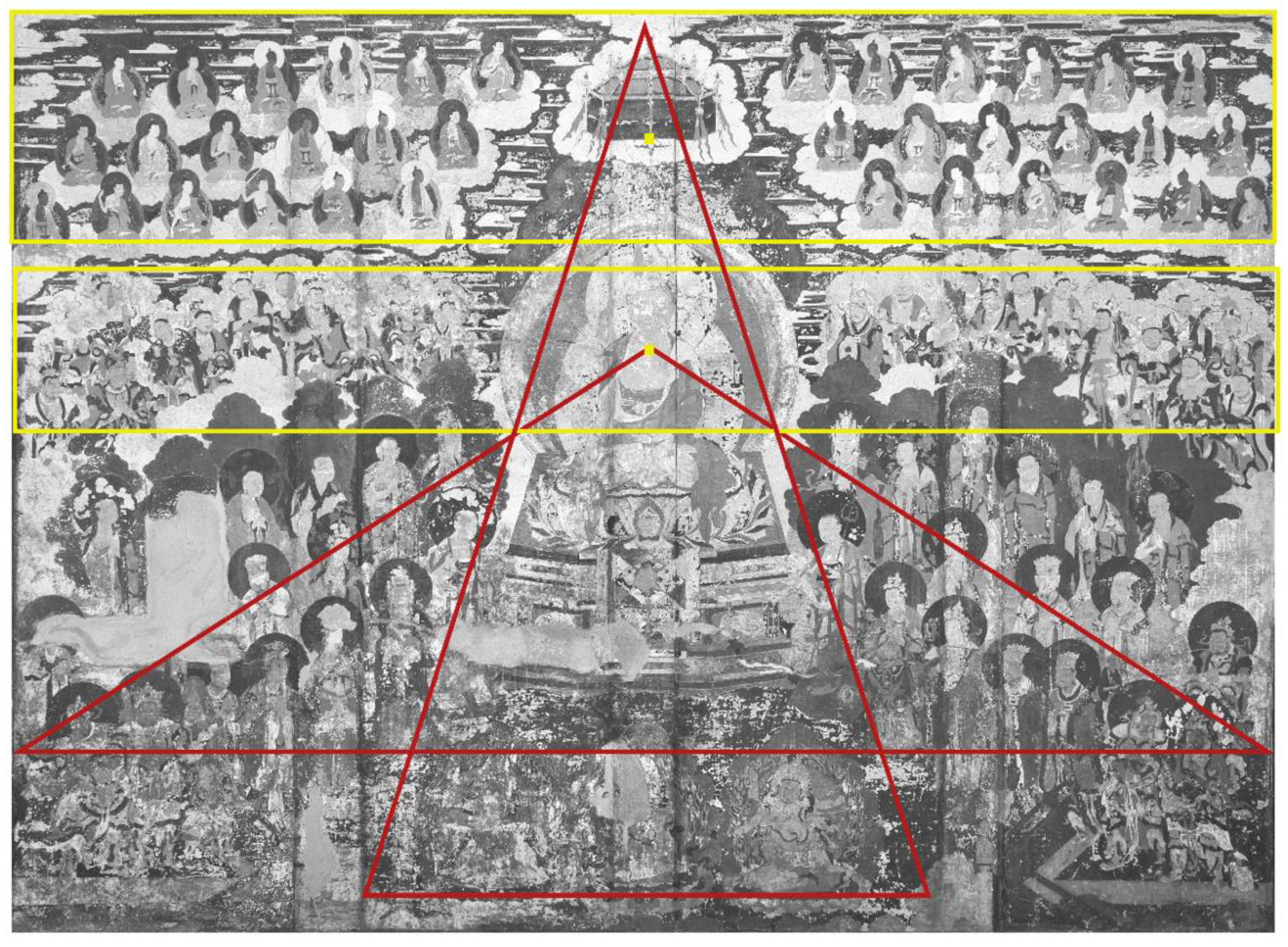

Sun Lei proposed the triangular structure of composition when analyzing the murals in the Mogao cave. This composition provides a stable view, breaking the originally parallel composition while forming a stable picture with multiple interconnected triangles, which makes the various contents in the mural more closely related (Sun 2024). When applied to

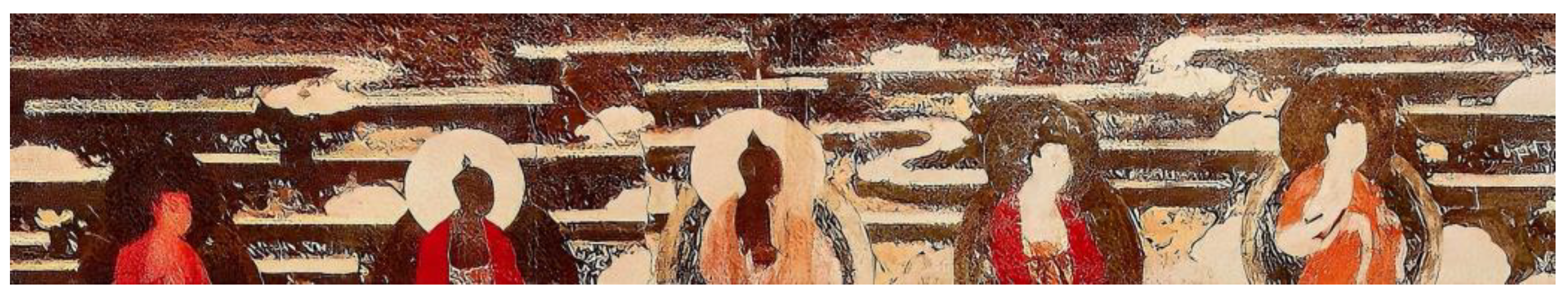

Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, the symmetrical composition has highlighted similar geometric features, mainly the rectangular and the triangular composition. The rectangular composition focuses on the upper half of the picture where groups of figures are located at a higher position behind Shakyamuni Buddha (

Figure 31). The steady layout of the rectangles ensures the stability of the composition and serves as an organized background to highlight the Shakyamuni in the foreground. The triangular composition is mainly shown in the central and lower parts of the picture, with the central one creating an upward trend that breaks the monotony of the upper rectangular composition, and the lower one depicting a group of deities tilted towards the central Buddha. The axisymmetric triangular structure is nested within the rectangular structure, breaking the parallel composition and creating a closer sense of connection between the figures and the central Buddha, thus highlighting his magnificence and solemnity throughout the viewing experience. The layered triangular composition also guides the viewers to enter the world of

Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting from the bottom of the image and gradually make their way to the top (

Figure 27).

As mentioned in

Section 3.3, the perspective method used in

Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting shows that the vanishing points are not concentrated on a single line of sight but instead move along as the triangular composition ascends from bottom to top. The concept of 'visual tiers’ is introduced to refer to multiple viewing points formed along the central axis as the vanishing points continuously rise through the composition (

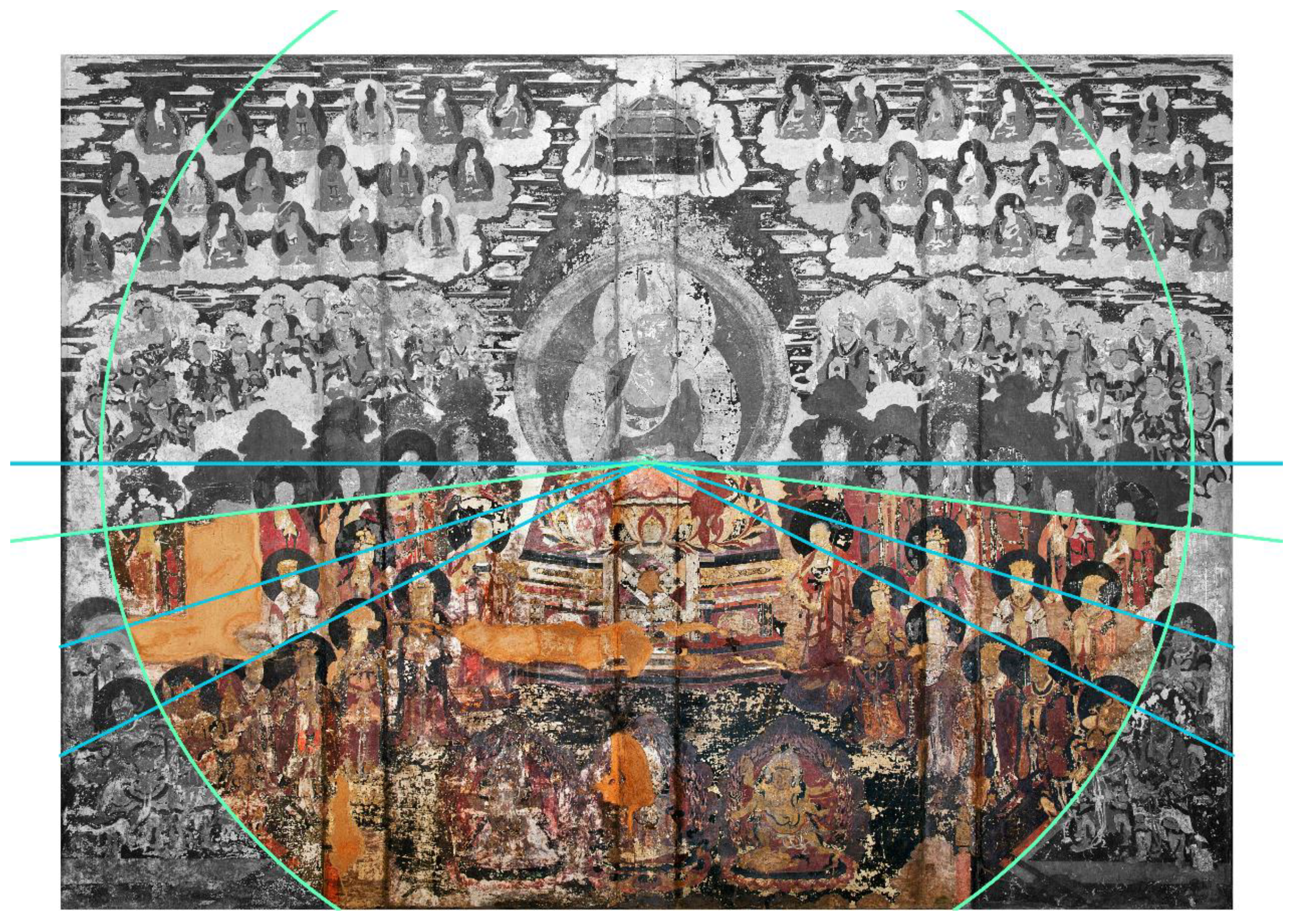

Figure 28). The ‘visual tiers’ in the picture is divided into three sections from the bottom to top. The first visual tier allows for an overhead view of the main deities around the central figure and shows a clear trend of distribution towards the center (

Figure 29). The second tier focuses on the main image of Shakyamuni Buddha including the lotus seat, the altar, and the canopy (

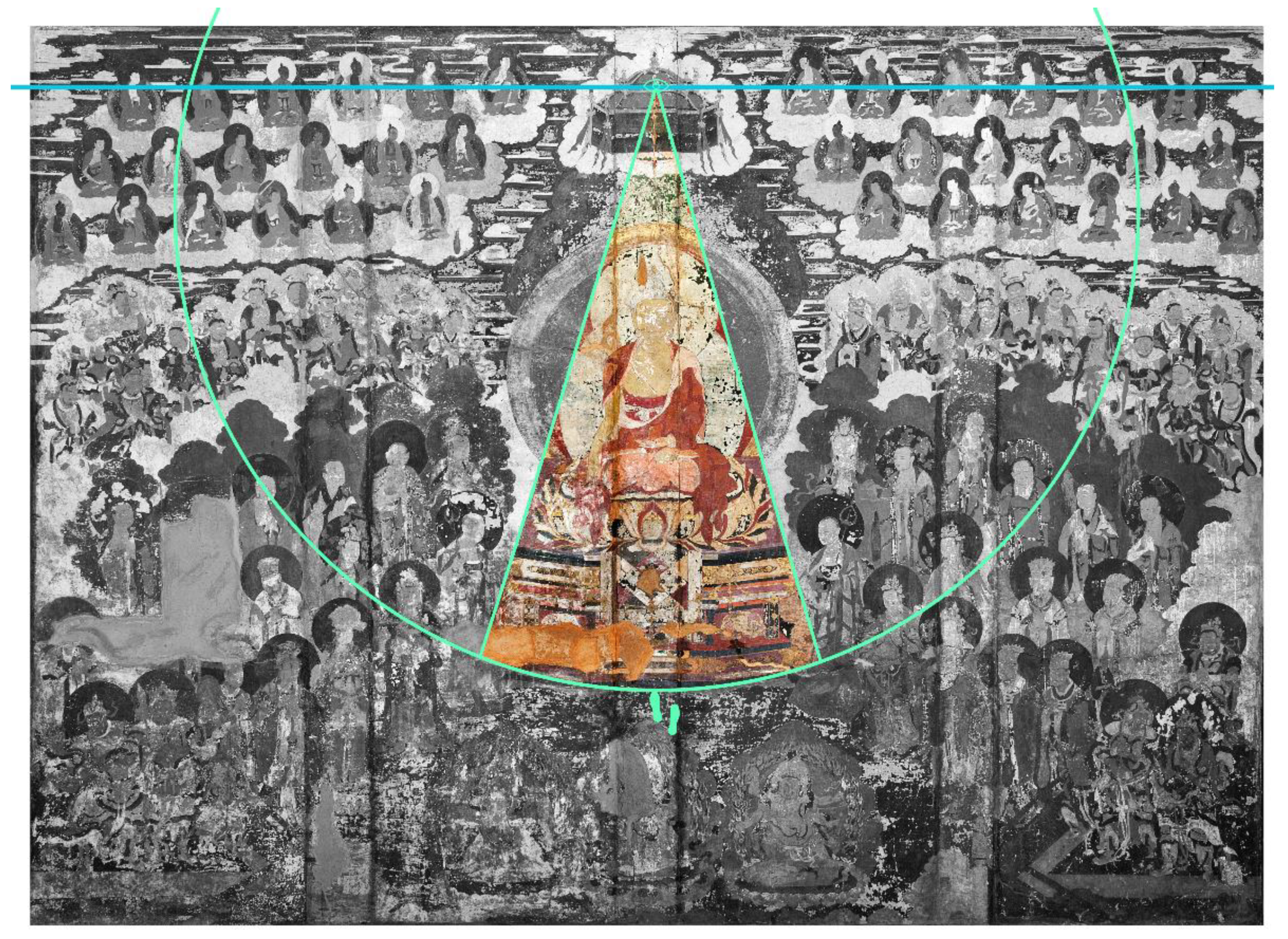

Figure 30). The vanishing point of this visual tier is at the top of the canopy, which allows for a maximum display of the different facets of the altar, making them visually compelling, while Shakyamuni himself is not subject to perspective distortion, thus enhancing the control of the main Buddha over the composition. The third viewing level focuses on the figures on either side of Shakyamuni Buddha at the top of the painting (

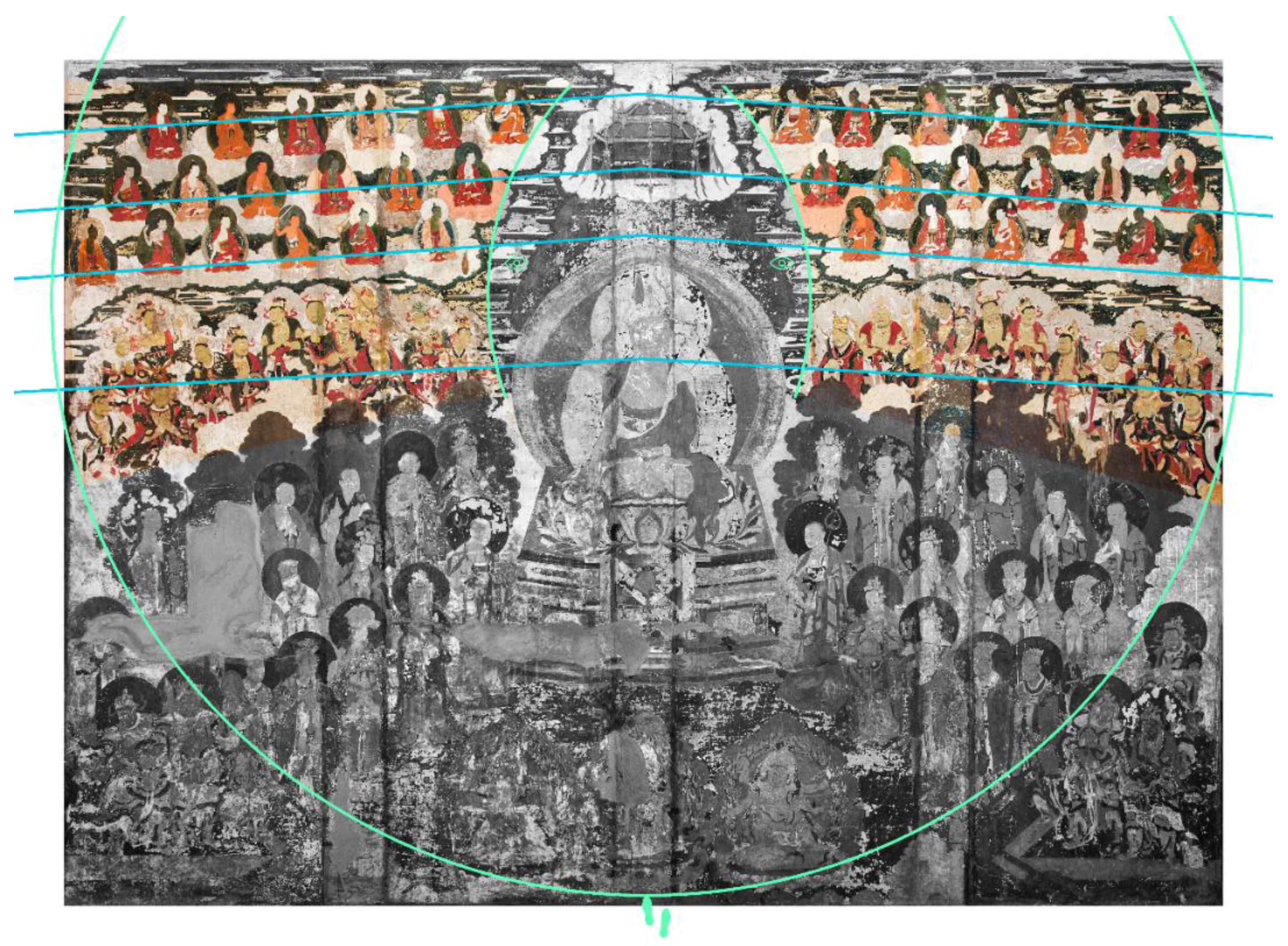

Figure 31). This viewing level does not have an actual vanishing point, with the figures aligned in a parallel way towards the center of the composition, creating an orderly background composition and emphasizing the central figure. If viewers were to physically enter the scene depicted in

Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting, they would advance along the central axis through these "visual tiers" and encounter multiple vanishing points that correspond to their changing standpoints. The use of "visual tiers" is another way to express the moving vanishing axes in the composition, and is helpful for viewers to better immerse themselves in the scenes depicted on the mural both visually and psychologically.

Figure 28.

Visual tiers’ in Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting.

Figure 28.

Visual tiers’ in Shakyamuni Buddha Sea Meeting.

Figure 29.

The first tier.

Figure 29.

The first tier.

Figure 30.

The second tier.

Figure 30.

The second tier.

Figure 31.

The third tier.

Figure 31.

The third tier.