Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

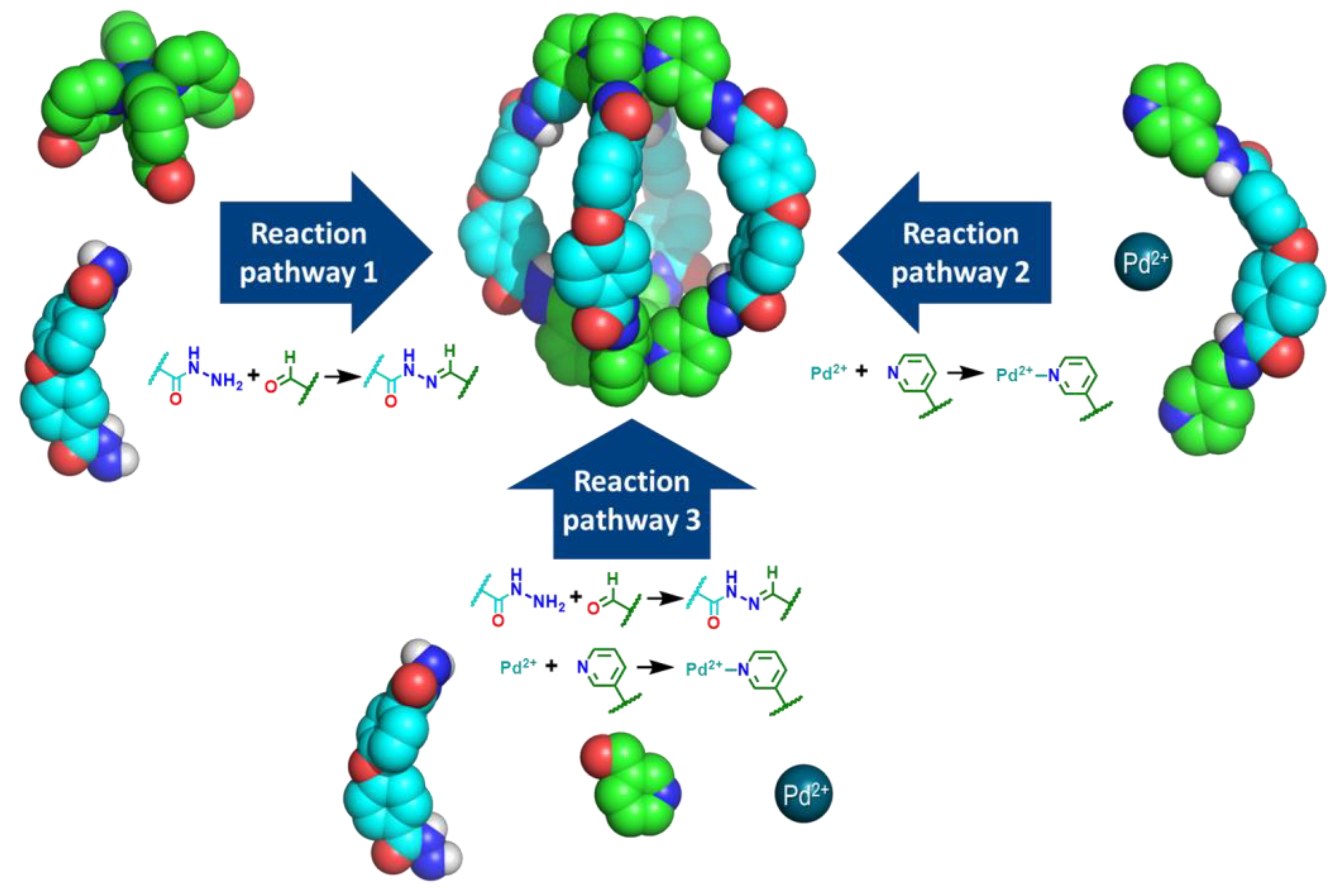

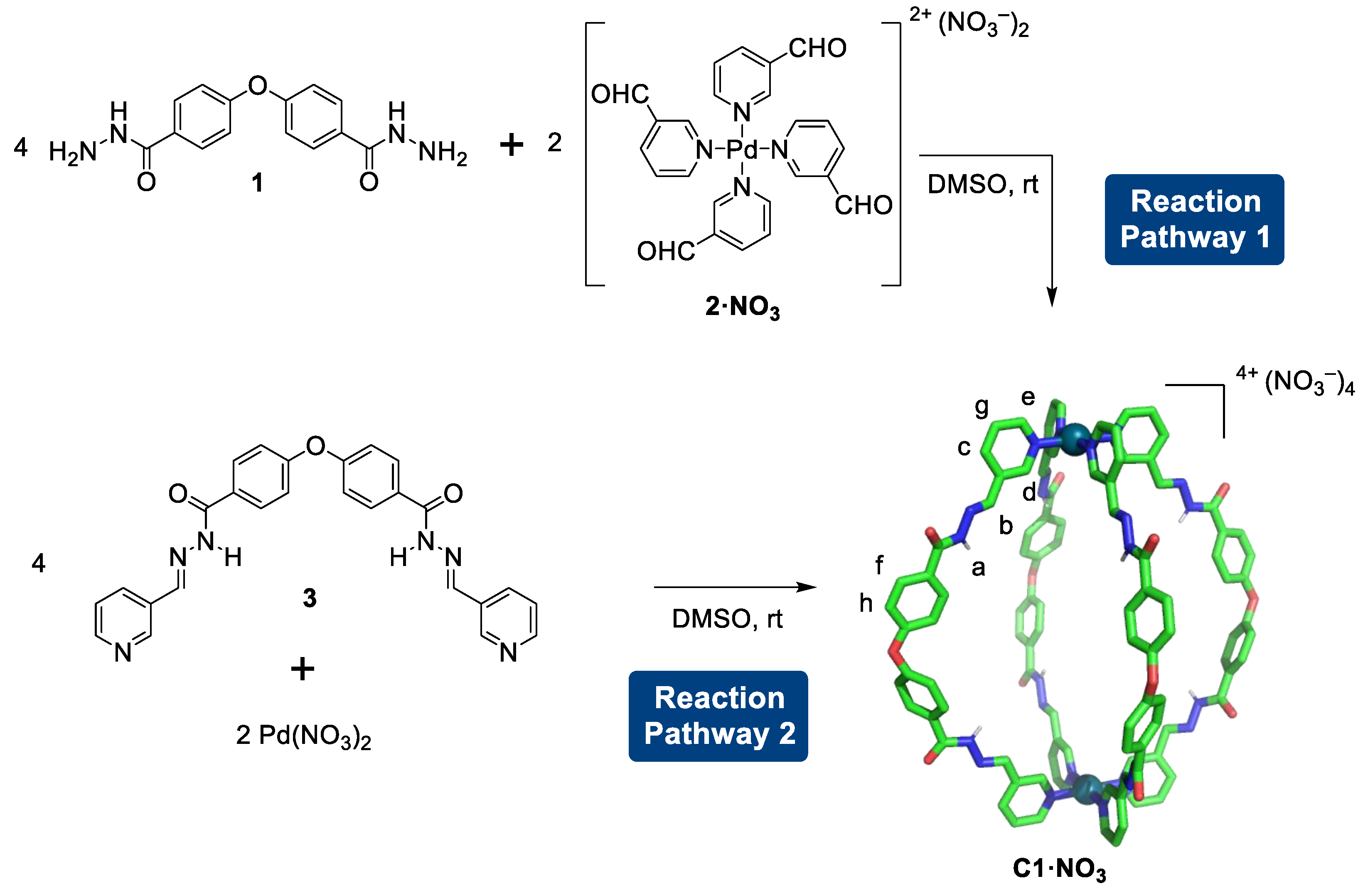

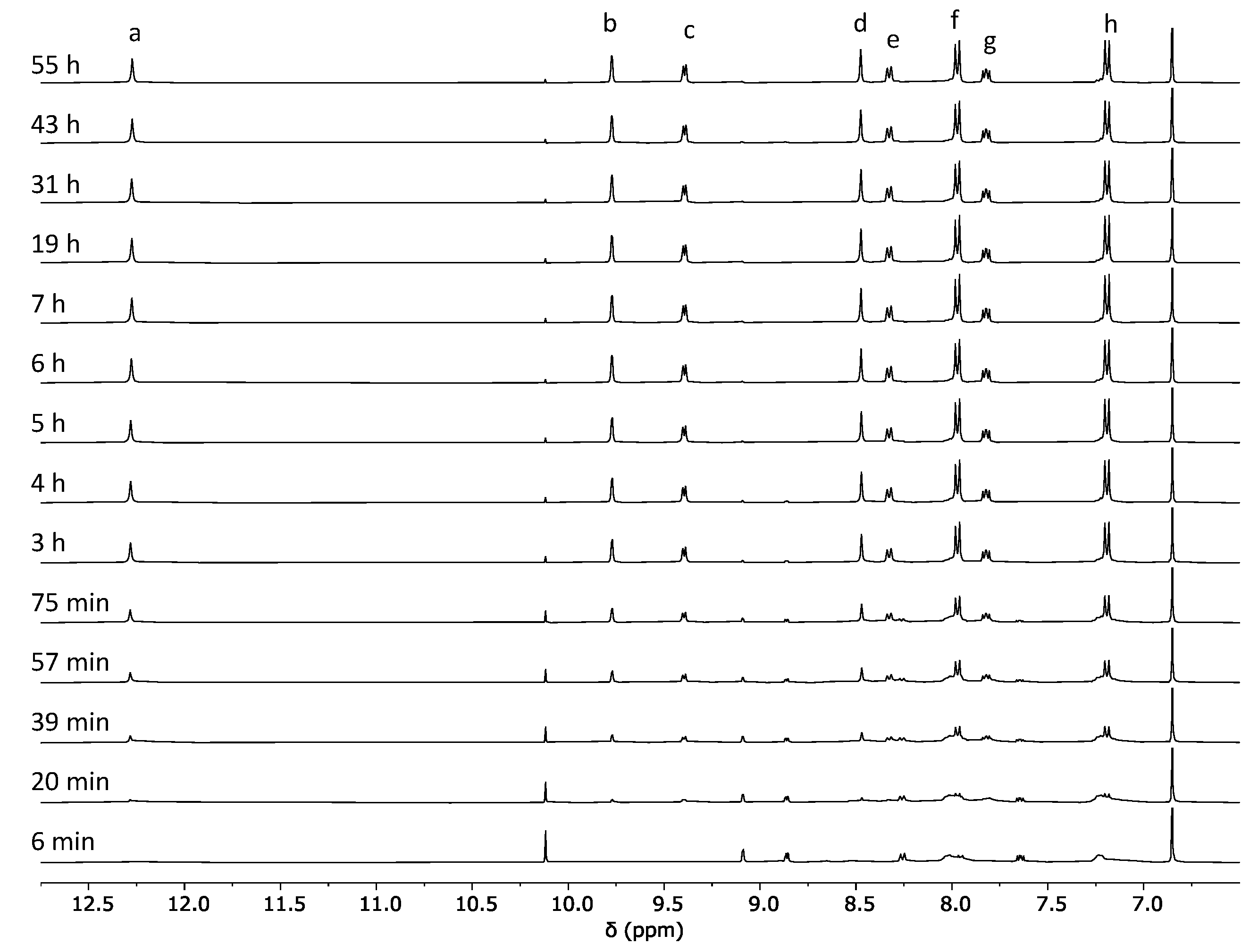

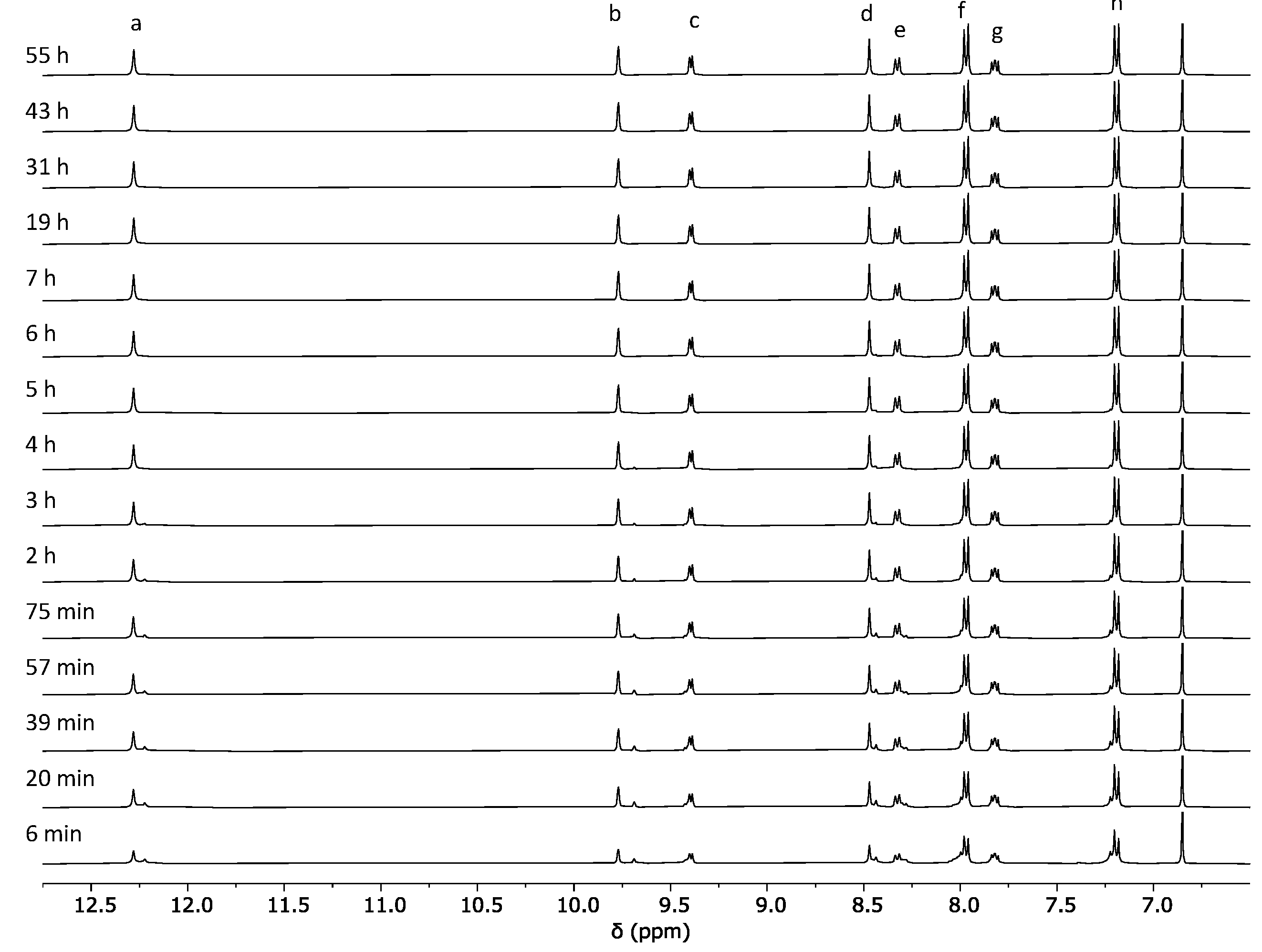

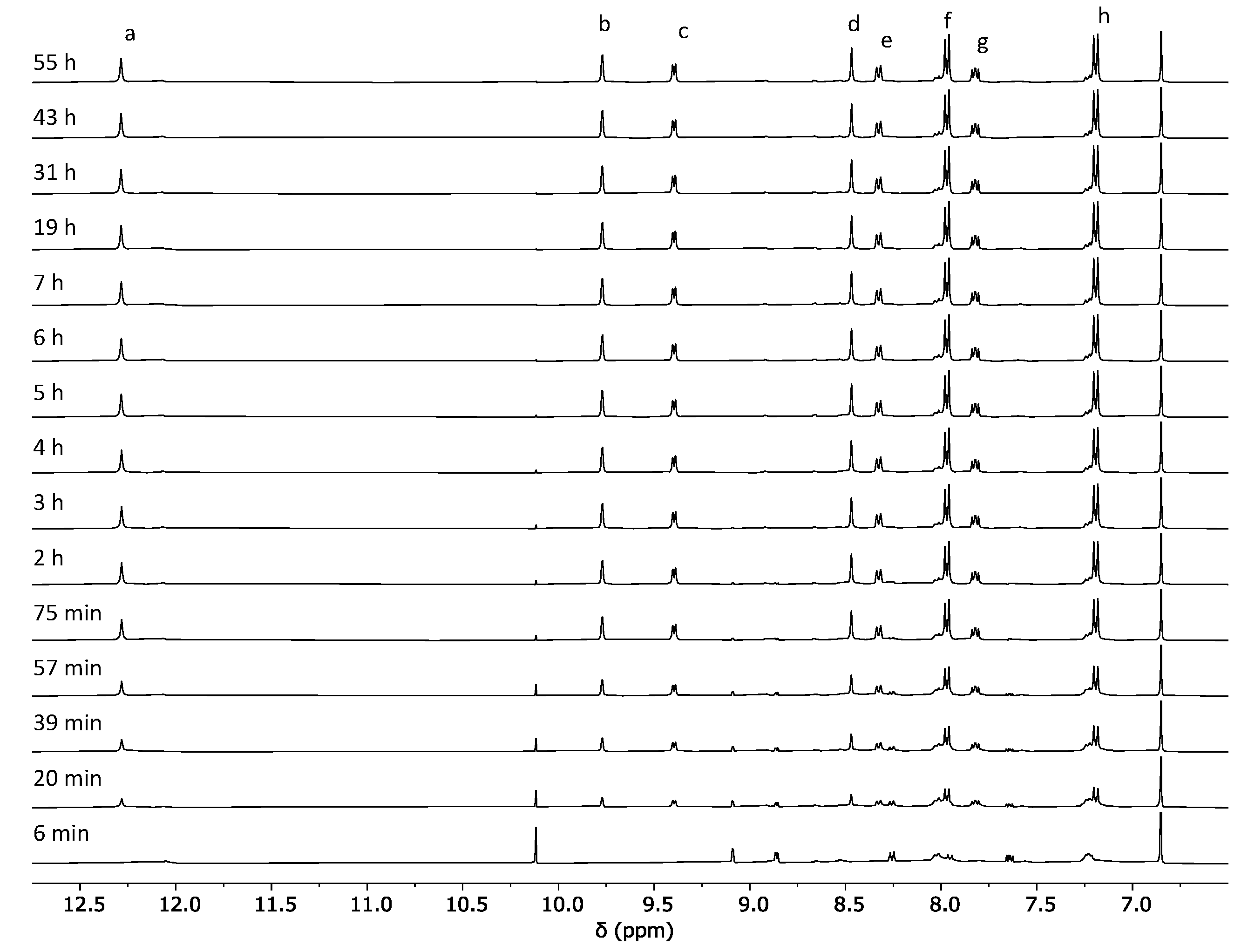

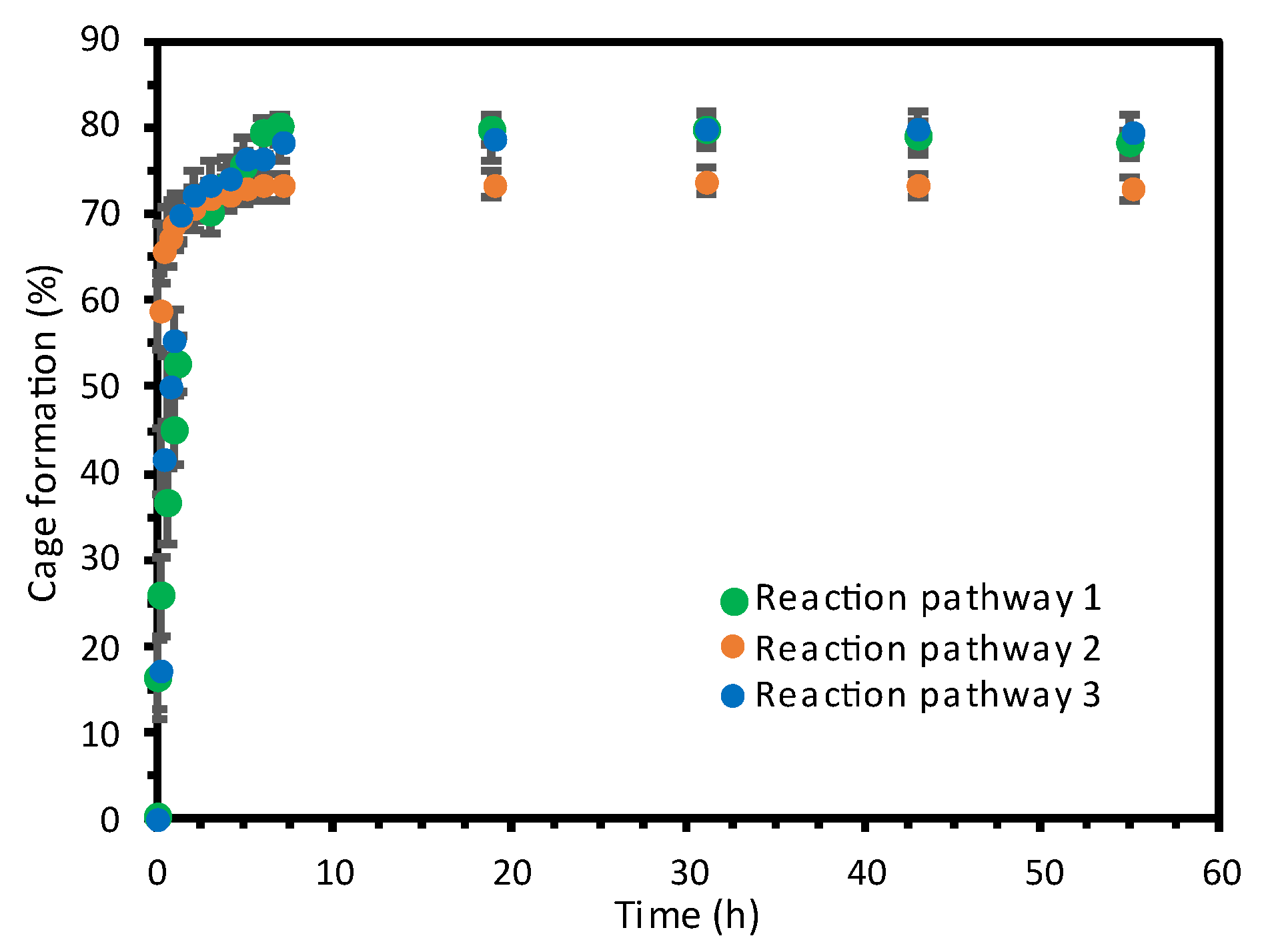

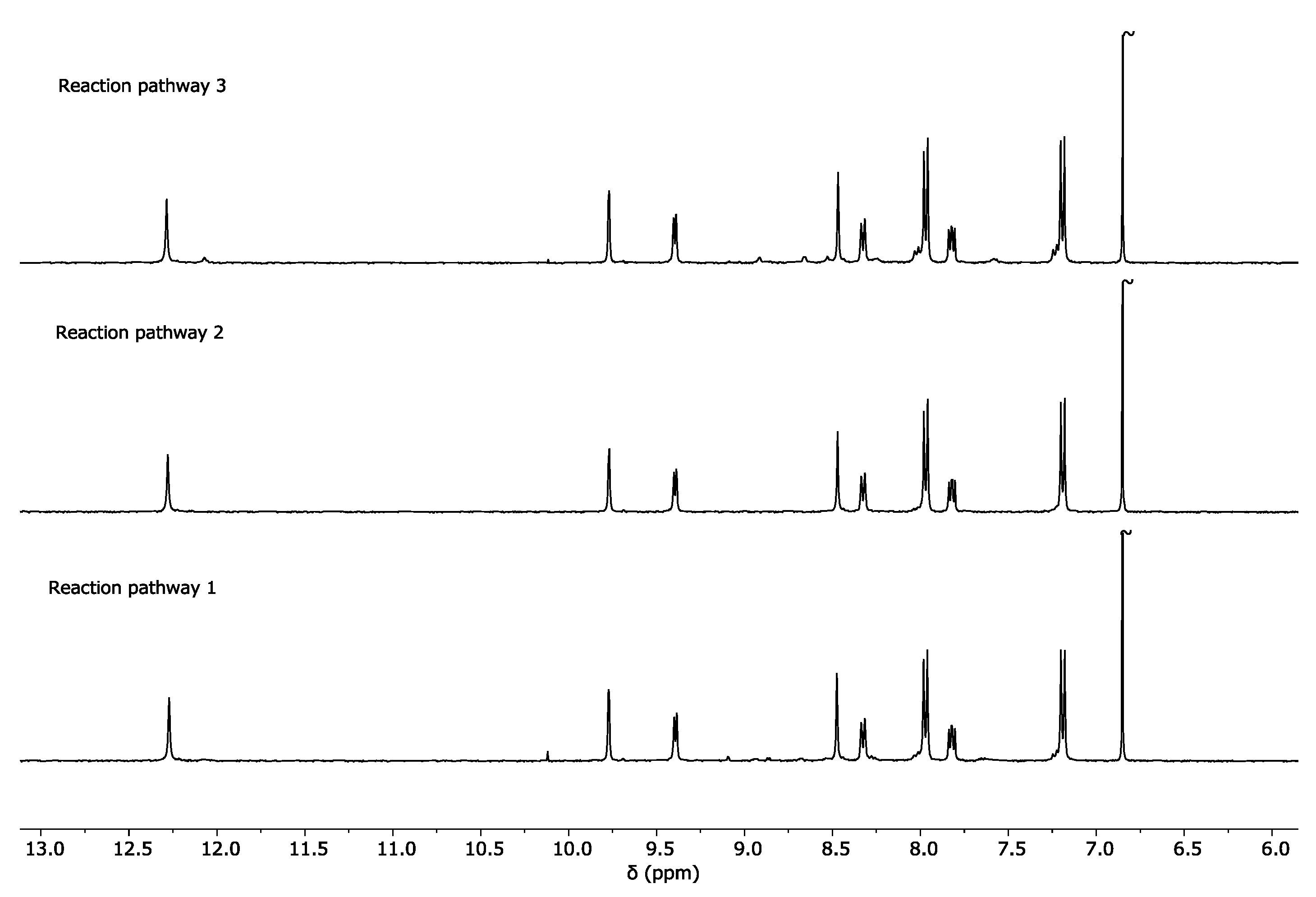

2.1. Self-Assembly Process of the PD2L4 Cage

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of Ligands and Cages

3.2. Cage Formation Kinetic Experiments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martí-Centelles, V.; Duarte, F.; Lusby, P. J. Host-Guest Chemistry of Self-Assembled Hemi-Cage Systems: The Dramatic Effect of Lost Pre-Organization. Isr. J. Chem. 2019, 59, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondelli, M.; Daranas, A. H.; Martín, T. Importance of Precursor Adaptability in the Assembly of Molecular Organic Cages. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 2113–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J. E. M. Developing Sophisticated Microenvironments in Metal-organic Cages. Trends Chem. 2023, 5, 717–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. E.; Jamieson, E. M. G.; White, L. E. M.; McTernan, C. T. Metal-Peptidic Cages—Helical Oligoprolines Generate Highly Anisotropic Nanospaces with Emergent Isomer Control. Chem 2024, 10, 2792–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Guan, Z.; Lin, H.; Yan, B.; Liu, K.; Zhou, H.; Fang, Y. Modeling the Enzyme Specificity by Molecular Cages Through Regulating Reactive Oxygen Species Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Ali, S. R.; Venkateswarulu, M.; Howlader, P.; Zangrando, E.; De, M.; Mukherjee, P. S. Self-Assembled Pd12 Coordination Cage as Photoregulated Oxidase-Like Nanozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18981–18989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montà-González, G.; Sancenón, F.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Martí-Centelles, V. Purely Covalent Molecular Cages and Containers for Guest Encapsulation. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 13636–13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percástegui, E. G.; Ronson, T. K.; Nitschke, J. R. Design and Applications of Water-soluble Coordination Cages. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 13480–13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C. J. T.; Hale, J.; Molinska, P.; Lewis, J. E. M. Supramolecular and Molecular Capsules, Cages, and Containers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, ASAP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Centelles, V.; Lawrence, A. L.; Lusby, P. J. High Activity and Efficient Turnover by a Simple, Self-Assembled Artificial "Diels-Alderase". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2862–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, J. M.; Rebek, J. Molecules in Confined Spaces: Reactivities and Possibilities in Cavitands. Chem. 2020, 6, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, A.; Puglisi, R.; Trusso Sfrazzetto, G. Catalysis inside Supramolecular Capsules: Recent Developments. Catalysts 2019, 9, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, L.-J. Metal–organic Cages: Applications in Organic Reactions. Chemistry 2022, 4, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskorz, T. K.; Martí-Centelles, V.; Spicer, R. L.; Duarte, F.; Lusby, P. J. Picking the Lock of Coordination Cage Catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 11300–11331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chen, L.-J. Metal–Organic Cages: Applications in Organic Reactions. Chemistry 2022, 4, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Lai, Z.; Long, Z.; He, Q. A Tetraphenylethylene-Based Superphane for Selective Detection and Adsorption of Trace Picric Acid in Aqueous Media. Supramol. Chem. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cognata, S.; Amendola, V. Recent Applications of Organic Cages in Sensing and Separation Processes in Solution. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 13668–13678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, D.; La Cognata, S.; Balduzzi, F.; Miljkovic, A.; Toma, L.; Amendola, V. A Smart Supramolecular Device for the Detection of t,t-Muconic Acid in Urine. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 15460–15465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludden, M. D.; Taylor, C. G. P.; Ward, M. D. Orthogonal Binding and Displacement of Different Guest Types Using a Coordination Cage Host with Cavity-Based and Surface-Based Binding Sites. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 12640–12650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, S.-M.; He, S.-S.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, C.-D.; Yu, S.; Jiang, W.; Yao, H.; Wang, L.-L.; Yang, L.-P. An Endo-functionalized Molecular Cage for Selective Potentiometric Determination of Creatinine. Chem. Sci. 2024, 14, 14791–14797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Lai, Z.; Long, Z.; He, Q. A Tetraphenylethylene-Based Superphane for Selective Detection and Adsorption of Trace Picric Acid in Aqueous Media. Supramol. Chem. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, S.-M.; He, S.-S.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, C.-D.; Yu, S.; Jiang, W.; Yao, H.; Wang, L.-L.; Yang, L.-P. An Endo-functionalized Molecular Cage for Selective Potentiometric Determination of Creatinine. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 14791–14797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, P. K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Purba, P. C.; Mukherjee, P. S. Coordination-induced Emissive Poly-nhc-derived Metallacage for Pesticide Detection. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 2569–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mal, P.; Breiner, B.; Rissanen, K.; Nitschke, J. R. White Phosphorus is Air-Stable within a Self-Assembled Tetrahedral Capsule. Science 2009, 324, 1697–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galan, A.; Ballester, P. Stabilization of Reactive Species by Supramolecular Encapsulation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1720–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ronson, T. K.; Zou, Y.-Q.; Nitschke, J. R. Metal–organic Cages for Molecular Separations. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M. A.; Cooper, A. I. The Chemistry of Porous Organic Molecular Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, S.; Zi, M.; Yuan, L. Recent Advances of Application of Porous Molecular Cages for Enantioselective Recognition and Separation. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ferreiro, M.; Gallagher, Q. M.; León, A. B.; Webb, M. A.; Criado, A.; Mosquera, J. Engineering a Surfactant Trap via Postassembly Modification of an Imine Cage. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 8920–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pacheco-Fernández, I.; Carpenter, J. E.; Aoyama, T.; Huang, G.; Pournaghshband Isfahani, A.; Ghalei, B.; Sivaniah, E.; Urayama, K.; Colón, Y. J.; Furukawa, S. Pore-networked Membrane Using Linked Metal-organic Polyhedra for Trace-level Pollutant Removal and Detection in Environmental Water. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, J.; Tang, M.; Zhang, M.; Hughes, R. P.; Staples, R. J.; Ke, C. Tripodal Organic Cages with Unconventional CH···O Interactions for Perchlorate Remediation in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 21723–21728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shui, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Yi, M.; You, Z.; Yang, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, B.; Bu, X.; Ma, S. Porous Organic Cage as an Efficient Platform for Industrial Radioactive Iodine Capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, e202411342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montà-González, G.; Ortiz-Gómez, E.; López-Lima, R.; Fiorini, G.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Martí-Centelles, V. Water-Soluble Molecular Cages for Biological Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montà-González, G.; Bastante-Rodríguez, D.; García-Fernández, A.; Lusby, P. J.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Martí-Centelles, V. Comparing organic and metallo-organic hydrazone molecular cages as potential carriers for doxorubicin delivery. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 10010–10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, A.; Woods, B.; Wenzel, M. The Promise of Self-Assembled 3D Supramolecular Coordination Complexes for Biomedical Applications. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 14715–14729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.-Y.; Pan, M.; Su, C.-Y. Metal-Organic Cages for Biomedical Applications. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 59, (3–4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.-T.; Yang, C.-Y.; Hu, L.-R.; Song, B.; Jin, T.; Jia, P.-P.; Ji, X.; Zheng, F.; Yang, H.-B.; Xu, L. Metallacages and Covalent Cages for Biological Imaging and Therapeutics. ACS Mater. Lett. 2023, 5, 1061–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Younus, H. A.; Chughtai, A. H.; Verpoort, F. Metal–organic Molecular Cages: Applications of Biochemical Implications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Feng, X.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Anticancer Agents Based on Metal Organic Cages. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 500, 215546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Nava, S.; De Jesús Valencia-Loza, S.; Percástegui, E. G. Protection and Transformation of Natural Products Within Aqueous Metal-organic Cages. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, L.; Alfonso, I.; Solà, J. Molecular Cages for Biological Applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9527–9540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, L.; Pérez, Y.; Carreira-Barral, I.; Bujons, J.; Bolte, M.; Bedia, C.; Solà, J.; Quesada, R.; Alfonso, I. Tuning pH-dependent Cytotoxicity in Cancer Cells by Peripheral Fluorine Substitution on Pseudopeptidic Cages. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montà-González, G.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Martí-Centelles, V. Requirements of Constrictive Binding and Dynamic Systems on Molecular Cages for Drug Delivery. Preprints 2024, 2024100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Mastalerz, M. Organic Cage Compounds-from Shape-Persistency to Function. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1934–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Stoddart, J. F. Emergent Behavior in Nanoconfined Molecular Containers. Chem. 2021, 7, 919–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, S.; Martí-Centelles, V.; Sakuma, Y.; Mashiko, T.; Kojima, T.; Nagashima, U.; Tachikawa, M.; Lusby, P. J.; Hiraoka, S. Quantitative Analysis of Self-Assembly Process of a Pd₂L₄ Cage Consisting of Rigid Ditopic Ligands. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Sanada, N.; Takeuchi, K.; Okazawa, A.; Hiraoka, S. Assembly of Six Types of Heteroleptic Pd2L4 Cages Under Kinetic Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 28061–28074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foianesi-Takeshige, L. H.; Takahashi, S.; Tateishi, T.; Sekine, R.; Okazawa, A.; Zhu, W.; Kojima, T.; Harano, K.; Nakamura, E.; Sato, H.; Hiraoka, S. Bifurcation of Self-assembly Pathways to Sheet or Cage Controlled by Kinetic Template Effect. Commun. Chem. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Centelles, V.; Pandey, M. D.; Burguete, M. I.; Luis, S. V. Macrocyclization Reactions: The Importance of Conformational, Configurational, and Template-Induced Preorganization. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8736–8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Centelles, V. Kinetic and thermodynamic concepts as synthetic tools in supramolecular chemistry for preparing macrocycles and molecular cages. Tetrahedron Lett. 2022, 93, 153676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Centelles, V.; Piskorz, T. K.; Duarte, F. CageCavityCalc (C3): A Computational Tool for Calculating and Visualizing Cavities in Molecular Cages. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 5604–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskorz, T. K.; Martí-Centelles, V.; Young, T. A.; Lusby, P. J.; Duarte, F. Computational Modeling of Supramolecular Metallo-organic Cages-Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 5806–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarzia, A.; Wolpert, E. H.; Jelfs, K. E.; Pavan, G. M. Systematic Exploration of Accessible Topologies of Cage Molecules via Minimalistic Models. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12506–12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T. A.; Gheorghe, R.; Duarte, F. cgbind: A Python Module and Web App for Automated Metallocage Construction and Host–Guest Characterization. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 3546–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcani, L.; Tarzia, A.; Szczypiński, F. T.; Jelfs, K. E. stk: An Extendable Python Framework for Automated Molecular and Supramolecular Structure Assembly and Discovery. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 214102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santolini, V.; Miklitz, M.; Berardo, E.; Jelfs, K. E. Topological Landscapes of Porous Organic Cages. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5280–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway, R. L.; Jelfs, K. E. High-throughput Approaches for the Discovery of Supramolecular Organic Cages. ChemPlusChem 2020, 85, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcconnell, A. J. Metallosupramolecular Cages: From Design Principles and Characterisation Techniques to Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 2957–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T. R.; Stang, P. J. Recent Developments in the Preparation and Chemistry of Metallacycles and Metallacages via Coordination. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7001–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, S. Design and Assembly of Porous Organic Cages. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 2261–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ullah, Z.; Stoddart, J. F.; Yavuz, C. T. Porous Organic Cages. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4602–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hilst, Q. V. C.; Pearcy, A. C.; Preston, D.; Wright, L. J.; Hartinger, C. G.; Brooks, H. J. L.; Crowley, J. D. A Dynamic Covalent Approach to [PtnL2n]2n+ Cages. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 4302–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisboa, L. S.; Riisom, M.; Dunne, H. J.; Preston, D.; Jamieson, S. M. F.; Wright, L. J.; Hartinger, C. G.; Crowley, J. D. Hydrazone- and Imine-containing [PdPtL4]4+ Cages: A Comparative Study of the Stability and Host–guest Chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 18438–18445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; John, R. P. Self-assembled Pd6l4 Cage and Pd4l4 Square Using Hydrazide Based Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Activity in Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling Reactions. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 12453–12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Engelhard, D. M.; Clever, G. H. Self-assembled Coordination Cages Based on Banana-shaped Ligands. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1848–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, S.; Tessarolo, J.; Clever, G. H. Increasing Structural and Functional Complexity in Self-assembled Coordination Cages. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 7269–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moree, L. K.; Faulkner, L. A. V.; Crowley, J. D. Heterometallic Cages: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Casini, A.; Kühn, F. E. Self-Assembled M2L4 Coordination Cages: Synthesis and Potential Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 275, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpik, G.; Walczak, A.; Gołdyn, M.; Harrowfield, J.; Stefankiewicz, A. R. Pd(II) Complexes with Pyridine Ligands: Substituent Effects on the NMR Data, Crystal Structures, and Catalytic Activity. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 14019–14029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, R.; Huc, I. Optimizing the Reversibility of Hydrazone Formation for Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2003, 942–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Emge, T. J.; Warmuth, R. Multicomponent Assembly of Cavitand-based Polyacylhydrazone Nanocapsules. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 9395–9405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzbicki, M.; Głowacka, A. A.; Szymański, M. P.; Szumna, A. A Chiral Member of the Family of Organic Hexameric Cages. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5200–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Qiu, F.; M. El-Sayed, E.-S.; Wang, W.; Du, S.; Su, K.; Yuan, D. Water-stable Hydrazone-linked Porous Organic Cages. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 13307–13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyle, E.; Mason, T.; Coote, M.; Izgorodina, E.; White, N. Robust Organic Cages Prepared Using Hydrazone Condensation Display Sulfate/hydrogenphosphate Selectivity in Water. ChemRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, J.-R.; Cao, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Hong, X.; Yang, C.; Li, H. Temperature-dependent Self-assembly of a Purely Organic Cage in Water. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3138–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-Y.; Liu, H.-K.; Wang, Z.-K.; Song, B.; Zhang, D.-W.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Z.-T. Olive-shaped Organic Cages: Synthesis and Remarkable Promotion of Hydrazone Condensation Through Encapsulation in Water. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 3943–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestrheim, O.; Schenkelberg, M. E.; Dai, Q.; Schneebeli, S. T. Efficient Multigram Procedure for the Synthesis of Large Hydrazone-linked Molecular Cages. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3965–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyle, É. M.; Goodwin, R. J.; Cox, C. J. T.; Smith, B. R.; Colebatch, A. L.; White, N. G. Expedient Decagram-Scale Synthesis of Robust Organic Cages That Bind Sulfate Strongly and Selectively in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 27127–27137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortón, P.; Wang, H.; Neira, I.; Blanco-Gómez, A.; Pazos, E.; Peinador, C.; Li, H.; García, M. D. “The Red Cage”: Implementation of Ph-responsiveness Within a Macrobicyclic Pyridinium-based Molecular Host. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, S. Self-Assembly Processes of Pd(II)- and Pt(II)-Linked Discrete Self-Assemblies Revealed by QASAP. Isr. J. Chem. 2019, 59, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppmeier, B. J.; Driessen, A. J.; Hehre, T. S.; Hehre, W. J.; Johnson, J. A.; Klunzinger, P. E.; Leonard, J. M.; Pham, I. N.; Pietro, W. J.; Jianguo, Y. Spartan ‘20, version 1.0.0 (Mar 8th 2021),Wavefunction Inc., 2011.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).