Submitted:

13 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables

2.4. Diagnostic Criteria

2.5. Data Collection and Measurements

2.6. Anthropometric Data and Blood Pressure Measurements

2.7. Ethics Considerations

2.8. Biochemistry

2.9. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

Standard Solutions

Sample Preparation

HPLC-MS Analysis

2.10. Biases

2.11. Sample Size

2.12. Quantitative Variables

2.13. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Gender-Specific Characteristics of Vitamins B in Relation to MS

3.2. Vitamins B and Risk of Hyperglycemia

3.3. Vitamins B and Parameters of Lipid Profile

3.4. Vitamins B and Risk of MS and Role of Co-Factors

4. Discussion

- Inclusion Criteria for Control Group: The inclusion criteria for the control group may have contributed to insufficient precision in delineating the differences between vitamin B levels and MS status. The control group comprised not only apparently healthy subjects but predominantly individuals who did not meet eligibility criteria for MS diagnosis. For instance, both groups include equal proportions of participants with overweight (50%).

- Reference Ranges for Vitamin B Levels: Our study faced constraints due to the lack of internationally available reference ranges for serum levels of vitamin B, as determined by mass spectrometry, both globally and specifically within Kazakhstan.

- Absence of Dietary Assessment: We did not investigate the dietary habits of participants, which could have enhanced the accuracy of our results by accounting for additional potential risk factors.

- Comorbidity Considerations: Information regarding thyroid disease as comorbidity was not collected in women without history of thyroid disorders. However, undiagnosed thyroid disorders may confound the association between riboflavin levels and the risk of MS, given that such conditions can lead to vitamin B2 deficiency. The prevalence of thyroid disorders is notably high in Kazakhstan, an area endemic for iodine deficiency.

- Lack of Data on Steatohepatitis: Data on the presence of steatohepatitis in obese participants were not available. This condition is also associated with vitamin B2 deficiency and could potentially interfere with the relationship between B2 levels and MS. Notably, steatohepatitis is reported to be more prevalent in Asian populations compared to their Caucasian counterparts.

- Dyslipidemia Considerations: We did not account for participants’ histories of statin use exceeding six months, which could impact LDL-C levels in the non-MS group.

- Measurement of Obesity: Obesity, a principal component of metabolic syndrome, was quantified solely through BMI and WC based on WHO and IDF criteria for European populations. Kazakhstan's adherence to European clinical guidelines regarding obesity, applicable across all ethnic groups, may not fully encapsulate the complexities surrounding the relationship between obesity and vitamin B levels, particularly in Asian populations including Kazakhs. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Kazakhs exhibit anthropometric similarities to Caucasians; however, there is currently a lack of data regarding visceral adiposity specific to this population. Such data could provide valuable insights into which diagnostic criteria for obesity would be most appropriate to apply in this context. The need for research addressing these gaps is imperative to enhance the accuracy and relevance of clinical assessments of obesity and its associated metabolic implications in the Kazakh population.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madan, K.; Paliwal, S.; Sharma, S.; Kesar, S.; Chauhan, N.; Madan, M. Metabolic syndrome: the constellation of co-morbidities, a global threat. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders) 2023, 23, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottillo, S.; Filion, K.B.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Pilote, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010, 56, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, G.L.; Kapral, M.K.; Fung, K.; Tu, J.V. Relation between age and cardiovascular disease in men and women with diabetes compared with non-diabetic people: a population-based retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2006, 368, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Li, X.; Adams, H.; Kubena, K.; Guo, S. Etiology of Metabolic Syndrome and Dietary Intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, S.H.; Kutmon, M.; de Kok, T.M.; Mariman, E.C.; van Baak, M.A.; Evelo, C.T.; Adriaens, M.E.; Arts, I.C. Stratifying cellular metabolism during weight loss: an interplay of metabolism, metabolic flexibility and inflammation. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Stanley, M.; Sellke, F.W.; Usheva, A. Altered Myocardial Energy Substrate Utilization in Metabolic Syndrome May Impact Pathways Involved in Contractile Dysfunction in Ischemic Myocardium. Circulation 2023, 148 (Suppl. S1), A17042–A17042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasun, P. Mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2020, 1866, 165838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahed, G.; Aoun, L.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Allam, S.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Bouferraa, Y.; Assi, H.I. Metabolic syndrome: updates on pathophysiology and management in 2021. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, J.A.; Coppotelli, G.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M.; Ross, J.M.; Sinclair, D.A. Mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whytock, K.L.; Pino, M.F.; Sun, Y.; Yu, G.; De Carvalho, F.G.; Yeo, R.X.; Vega, R.B.; Parmar, G.; Divoux, A.; Kapoor, N.; Yi, F. Comprehensive interrogation of human skeletal muscle reveals a dissociation between insulin resistance and mitochondrial capacity. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2023, 325, E291–E302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Dietz, W.H. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Jama 2002, 287, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakka, H.M.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Lakka, T.A.; Niskanen, L.K.; Kumpusalo, E.; Tuomilehto, J.; Salonen, J.T. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. Jama 2002, 288, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner-Lans, V.; Rubio-Ruiz, M.E.; Pérez-Torres, I.; de MacCarthy, G.B. Relation of aging and sex hormones to metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Experimental gerontology 2011, 46, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Barbagallo, M. The biology of the metabolic syndrome and aging. Current opinion in clinical nutrition & metabolic care 2016, 19, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoio, D.M.; Neufer, P.D. Lipid-induced mitochondrial stress and insulin action in muscle. Cell metabolism 2012, 15, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.J.; Grefte, S.; Keijer, J.; De Boer, V.C. Mito-nuclear communication by mitochondrial metabolites and its regulation by B-vitamins. Frontiers in physiology 2019, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Y.; Field, M.S. The roles of mitochondrial folate metabolism in supporting mitochondrial DNA synthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and cellular function. Current Developments in Nutrition 2020, 4, nzaa153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, A.; Legendre, F.; Appanna, V.D. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle: a malleable metabolic network to counter cellular stress. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2023, 58, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P.K.; Finley, L.W. Regulation and function of the mammalian tricarboxylic acid cycle. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragni, V.; Primiano, G.; Tummolo, A.; Cafferati Beltrame, L.; La Piana, G.; Sgobba, M.N.; Cavalluzzi, M.M.; Paterno, G.; Gorgoglione, R.; Volpicella, M.; Guerra, L. Personalized medicine in mitochondrial health and disease: molecular basis of therapeutic approaches based on nutritional supplements and their analogs. Molecules 2022, 27, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, N.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, N.; Singh, M.; Kant, R.; Kalyani, V. Effect of vitamin B6, B9, and B12 supplementation on homocysteine level and cardiovascular outcomes in stroke patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D. Associations of dietary vitamin B1, vitamin B2, niacin, vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and folate equivalent intakes with metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2020, 71, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satapathy, S.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Patro, B.K.; Khan, S.; Naik, S. Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A multi-arm randomized controlled clinical trial. Complementary therapies in medicine 2020, 53, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.Y.; Kim, J.H. Low riboflavin intake is associated with cardiometabolic risks in Korean women. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition 2019, 28, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, Z.; He, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Tan, W.; Rong, S. Association between Vitamin B and Obesity in Middle-Aged and Older Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2023, 15, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci, D.; Kutlucan, A.; Öztürk, S.; Karabulut, I.; Yildirim, H.A.; Celer, A.; Celbek, G.; Kara, I.H. Evaluation of vitamin B-12 level in middle-aged obese women with metabolic and non-metabolic syndrome: case-control study. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences 2012, 42, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beketova, N.A.; Pavlovskaya, E.V.; Kodentsova, V.M.; Vrzhesinskaya, O.A.; Kosheleva, O.A.; Sokolnikov, A.A.; Strokova, T.V. Biomarkers of vitamin status in obese school children. Voprosy Pitaniia 2019, 88, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consultation, W.E., 2008. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio. Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008, pp.8-11.

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; Hanssen, H. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension: Developed by the task force on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Endocrinology (ESE) and the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). European Heart Journal 2024, ehae178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo clinic laboratories. Test catalog. Available online: https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/overview (accessed on 02 September 2024).

- Kodentsova, V.M.; Vrzhesinskaya, O.A.; Spirichev, V.B. Fluorometric riboflavin titration in plasma by riboflavin-binding apoprotein as a method for vitamin B2 status assessment. Annals of nutrition and metabolism 1995, 39, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.; Zubair, M.; Ho, C.L.; McAnena, L.; McNulty, H.; Ward, M.; Lamers, Y. Plasma riboflavin concentration as novel indicator for vitamin-B2 status assessment: suggested cutoffs and its association with vitamin-B6 status in women. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2020, 79, E658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Qian, Y.; Shen, Q.; Yang, M.; Dong, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cui, X.; Ma, H. Metabolic and genetic markers improve prediction of incident type 2 diabetes: a nested case-control study in chinese. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2022, 107, 3120–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

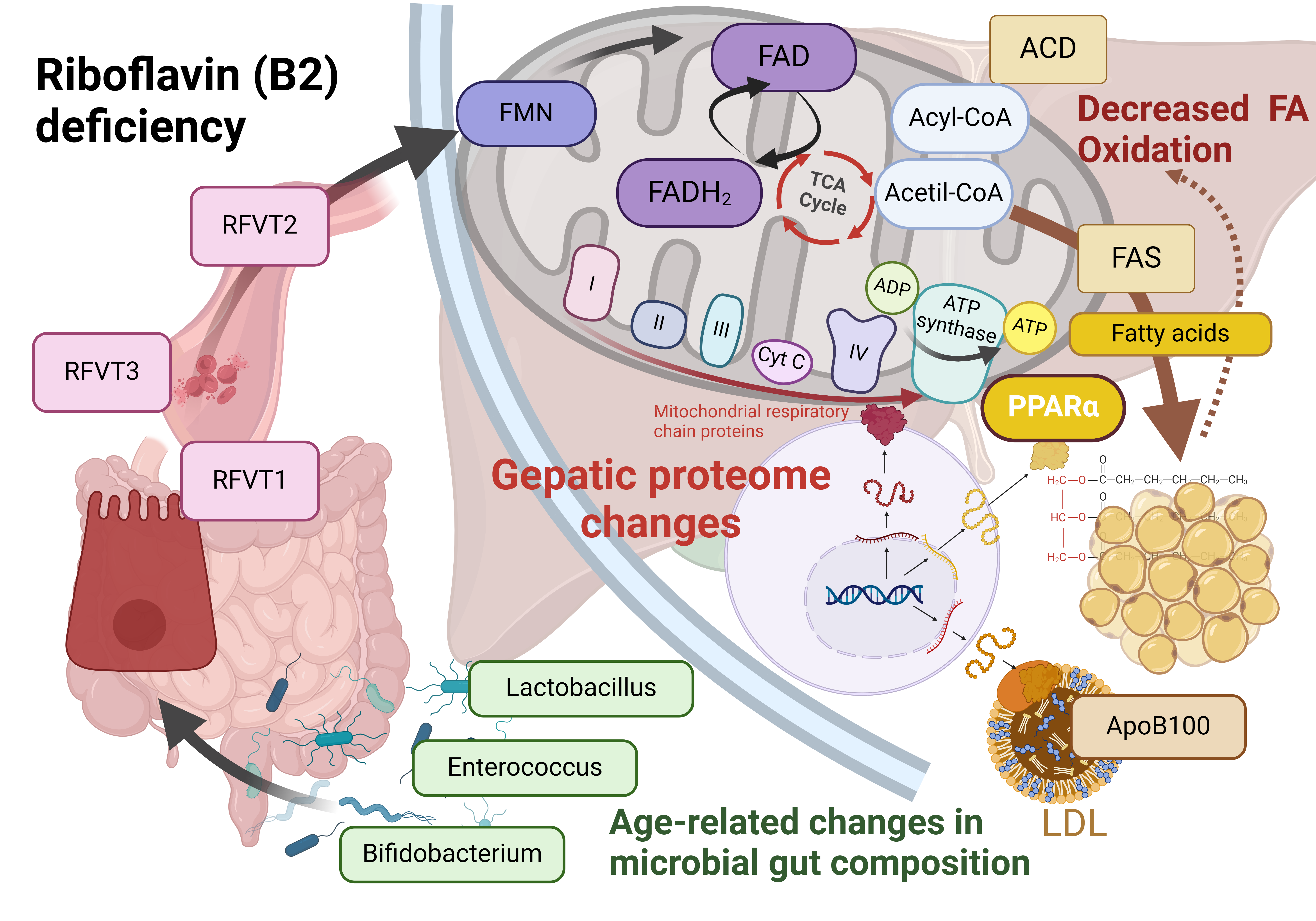

- Henriques, B.J.; Gomes, C.M. Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and mitochondrial energy. In Molecular Nutrition 2022, (pp. 225-244). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, S.; Yaplito-Lee, J. Riboflavin metabolism: role in mitochondrial function. J. Transl. Genet. Genom 2020, 4, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, C.; Dehlia, A.; Guthridge, M.A. New insights into the nutritional genomics of adult-onset riboflavin-responsive diseases. Nutrition & Metabolism 2023, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P.; Strippoli, V.; Fang, B.; Cimmino, L. B Vitamins and One-Carbon Metabolism: Implications in Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masschelin, P.M.; Saha, P.; Ochsner, S.A.; Cox, A.R.; Kim, K.H.; Felix, J.B.; Sharp, R.; Li, X.; Tan, L.; Park, J.H.; Wang, L. Vitamin B2 enables regulation of fasting glucose availability. Elife 2023, 12, e84077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bian, X.; Wan, M.; Dong, W.; Gao, W.; Yao, Z.; Guo, C. Effects of riboflavin deficiency and high dietary fat on hepatic lipid accumulation: a synergetic action in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrition & Metabolism 2024, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Xu, Q.; Guo, C.; Li, B. Riboflavin deficiency affects lipid metabolism partly by reducing apolipoprotein B100 synthesis in rats. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2019, 70, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, K.C.; Chew, Y.C.; Zempleni, J. Riboflavin deficiency impairs oxidative folding and secretion of apolipoprotein B-100 in HepG2 cells, triggering stress response systems. The Journal of nutrition 2005, 135, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, B.; Bosch, A.M. Clinical presentation and outcome of riboflavin transporter deficiency: mini review after five years of experience. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 2016, 39, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udhayabanu, T.; Karthi, S.; Mahesh, A.; Varalakshmi, P.; Manole, A.; Houlden, H.; Ashokkumar, B. Adaptive regulation of riboflavin transport in heart: effect of dietary riboflavin deficiency in cardiovascular pathogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2018, 440, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.; Tomar, S.K.; De, S. Lactic acid bacteria as a cell factory for riboflavin production. Microbial biotechnology 2016, 9, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slouha, E.; Rezazadah, A.; Farahbod, K.; Gerts, A.; Clunes, L.A.; Kollias, T.F. Type-2 diabetes mellitus and the gut microbiota: Systematic review. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, H.; Ren, J.; Ren, F.; Jin, J. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis A12 prevents obesityassociated dyslipidemia by modulating gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acid production and energy metabolism in high-fat diet-fed mice. Food & Nutrition Research 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, O.H.; Lee, M.; Bang, W.Y.; Nam, E.H.; Jeon, H.J.; Shin, M.; Yang, J.; Jung, Y.H. Bifidobacterium lactis IDCC 4301 exerts anti-obesity effects in high-fat diet-fed mice model by regulating lipid metabolism. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2023, 67, 2200385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, D.; Cui, X.; Ji, C. Vitamin B12 status and folic acid/vitamin B12 related to the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2022, 22, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, B.; Song, Y.; Lin, T.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Guo, H.; Chen, P.; Yang, Y. Vitamin B12 and risk of diabetes: new insight from cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT). BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2020, 8, e001423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MS | Non-MS | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 104 | 86 | |

| Age (yrs) Mean (SD) |

52.72 (7.10) | 49.94 (7.72) | 0.01 |

| Gender Male, n (%) Female, n (%) |

46 (57.50) 58 (52.73) |

34 (42.50) 52 (47.27) |

0.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) Male, mean (SD) Female, mean (SD) |

27.42 (4.49) 27.63 (6.73) |

24.52 (4.38) 23.56 (5.59) |

0.1 0.01 |

| WC (cm) Male, mean (SD) Female, mean (SD) |

111.44 (13.36) 102.17 (11.42) |

99.59 (12.15) 90.24 (9.88) |

0.0002 0.0001 |

| BPsyst (mmHg) Male, mean (SD) Female, mean (SD) |

131.96 (14.94) 128.27 (16.56) |

122.29 (13.07) 112.24 ± 17.69 |

0.004 0.0001 |

| BPdiast (mmHg) Male, mean (SD) Female, mean (SD) |

86.25 (10.19) 79.61 (10.14) |

80.09 (10.15) 71.61 (11.75) |

0.01 0.0005 |

| HR (bpm) Male, mean (SD) Female, mean (SD) |

75.44 (8.60) 73.78 (8.17) |

74.92 (9.03) 73.39 (9.22) |

0.8 0.8 |

| Smoking habit Yes, n (%) No, n (%) |

18 (26.47) 50 (73.53) |

39 (33.05) 79 (66.95) |

0.7 0.3 |

| HT Yes, n (%) No, n (%) |

35 (51.47) 33 (48.53) |

26 (22.04) 92 (77.96) |

0.0001 0.0001 |

| Antihypertensive therapy Yes, n (%) No, n (%) |

30 (44.12) 38 (55.88) |

16 (13.59) 102 (86.44) |

0.0001 0.0001 |

| Biochemistry parameters, mmol/L | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS, Mean (SD) |

Non-MS, Mean (SD) |

MS, Mean (SD) |

Non-MS, Mean (SD) |

|

| Creatinine | 96.22 (18.39) | 87.83 (17.14) | 65.65 (25.75) | 63.21 (13.62) |

| Glucose | 4.98 (2.00) | 4.52 (1.31) | 6.50 (2.99) | 4.57 (0.74)* |

| HbA1c, % | 6.27 (0.87) | 5.88 (0.57)* | 6.73 (1.63) | 5.72 (0.45)* |

| TC | 5.39 (1.05) | 5.05 (0.76) | 5.33 (0.98) | 5.08 (0.98) |

| HDL-C | 1.05 (0.28) | 1.25 (0.26)* | 1.25 (0.25) | 1.54 (0.27)* |

| LDL-C | 3.14 (0.87) | 3.31 (0.69) | 3.34 (0.77) | 3.21 (0.84) |

| TG | 3.59 (1.03) | 1.39 (0.69)* | 1.87 (1.09) | 1.04 (0.42)* |

| Vitamins B, ng/ml |

Observations | Log-transformed Mean (SD) | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2 | ||||

| Females | 110 | 0.75 (0.54) | 0.65, 0.85 | 0.042 |

| Males | 80 | 0.91 (0.52) | 0.79, 1.02 | |

| B3 | ||||

| Females | 106 | -1.03 (1.09) | -1.24, -0.83 | 0.122 |

| Males | 80 | -1.25 (0.78) | -1.42, -1.07 | |

| B6>2.16 | ||||

| Females | 110 | 0.62 (0.60) | 0.50, 0.73 | 0.003 |

| Males | 80 | 0.86 (0.52) | 0.75, 0.98 | |

| B9 | ||||

| Females | 109 | 2.72 (0.57) | 2.62, 2.83 | 0.052 |

| Males | 80 | 2.87 (0.49) | 2.77, 2.98 | |

| B12 | ||||

| Females | 91 | 0.39 (1.31) | 0.12, 0.67 | 0.364 |

| Males | 76 | 0.57 (1.18) | 0.30, 0.84 | |

| Vitamins B, ng/ml |

MS, n (%) | non-MS, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 (57.5) | 34 (42.5) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Range | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) |

Range | |

| B2 | 2.28 (1.72-2.96) |

2.69 (1.75) | 0.73-12.05 | 2.17 (1.83-3.61) |

3.22 (2.67) | 0.98 -12.88 |

| B3 | 0.26 (0.16-0.40) |

0.34 (0.29) | 0.61-1.39 | 0.27 (0.21-0.47) |

0.52 (1.06) | 0.11- 6.92 |

| B6 | 2.47 (1.71-3.22) |

2.56/1.07 | 0.25-6.25 | 2.53 (1.94-3.20) |

2.64 (1.14) | 0.29-5.74 |

| B9 | 18.25 (13.77-24.12) |

19.11/7.59 | 3.62-43.54 | 17.62 (12.55-22.68) |

19.63(10.56) | 3.05-50.07 |

| B12 | 1.55 (0.75-3.85) |

3.69/5.07 | 0.33-24.17 | 1.43 (0.73-4.59) |

3.71(4.70) | 0.87-15.82 |

| Vitamins B, ng/ml |

MS, n (%) | non-MS, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 (52.7) | 52 (47.3) | |||||

| Median (IQR) |

Mean (SD) |

Range | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) |

Range | |

| B2 | 2.20 (1.64-2.87) |

2.67 (1.86) | 0.56-11.42 | 1.89 (1.45-2.44) |

1.99 (0.80) | 0.46-4.87 |

| B3 | 0.28 (0.21-0.52) |

0.96/2.10 | 0.07-9.42 | 0.25 (0.17-0.44) |

0.71/1.45 | 0.81-7.77 |

| B6 | 2.05 (1.64-2.88) |

2.20/0.95 | 0.13-5.61 | 1.86 (1.45-2.27) |

1.98/0.85 | 0.75-4.95 |

| B9 | 16.13 (11.29-21.56) |

17.31/9.23 | 1.82-63.12 | 15.00 (11.68-18.60) |

15.70/6.29 | 4.18-38.00 |

| B12 | 1.25 (0.69-3.43) |

5.61/11.95 | 0.15-37.06 | 0.85 (0.56-1.49) |

1.87/2.97 | 0.18-15.82 |

| Vitamins, ng/ml |

OR for MS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted for | |||

| LDL-C≥3.3mmol/L | HDL-C≤1.03 mmol/L in males, ≤1.29 mmol/L in females |

TG≥1.7 mmol/L | ||

| B2≥2.15 | 1.79* | 1.82* | 1.84 | 1.59 |

| B3≥0.28 | 1.18 | 1.82* | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| B6≥2.16 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.61 | 1.22 |

| B9≥16.25 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 1.53 | 1.61 |

| B12≥1.21 | 1.80 | 1.76 | 2.0* | 1.70 |

| OR for MS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted for: (OR, 95%CI, p-value) | |||

| B2≥2.15 | B3≥0.28 ng/ml | B6≥2.16 ng/ml | B9≥16.25 ng/ml | B12≥1.21 ng/ml |

| 1.79* | 1.98* | 1.70 | 1.63 | 1.81 |

| 1.003, 3.19 | 1.09, 3.61 | 0.94, 3.08 | 0.84, 3.17 | 0.91, 3.63 |

| 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).