Submitted:

11 October 2024

Posted:

14 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

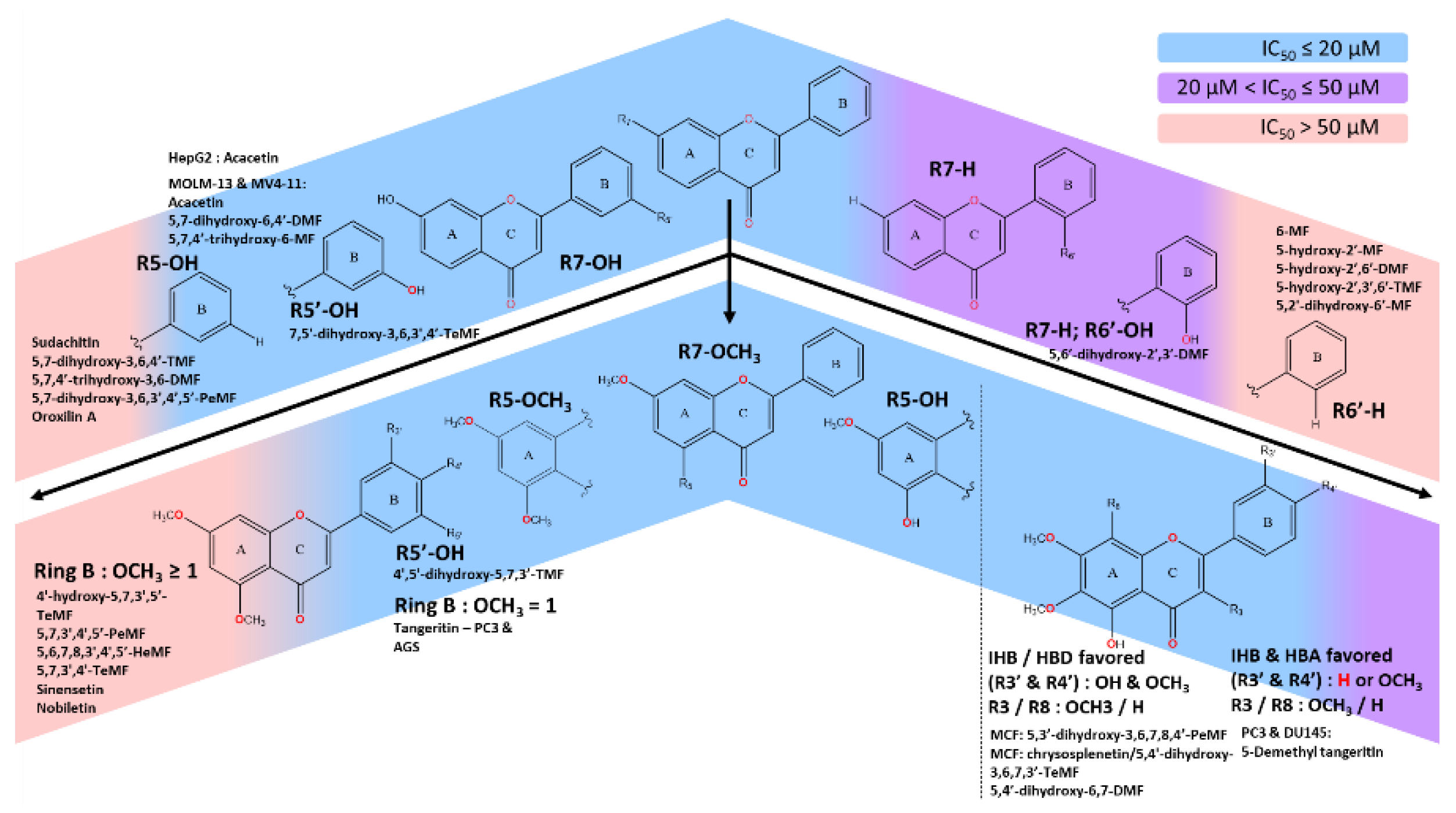

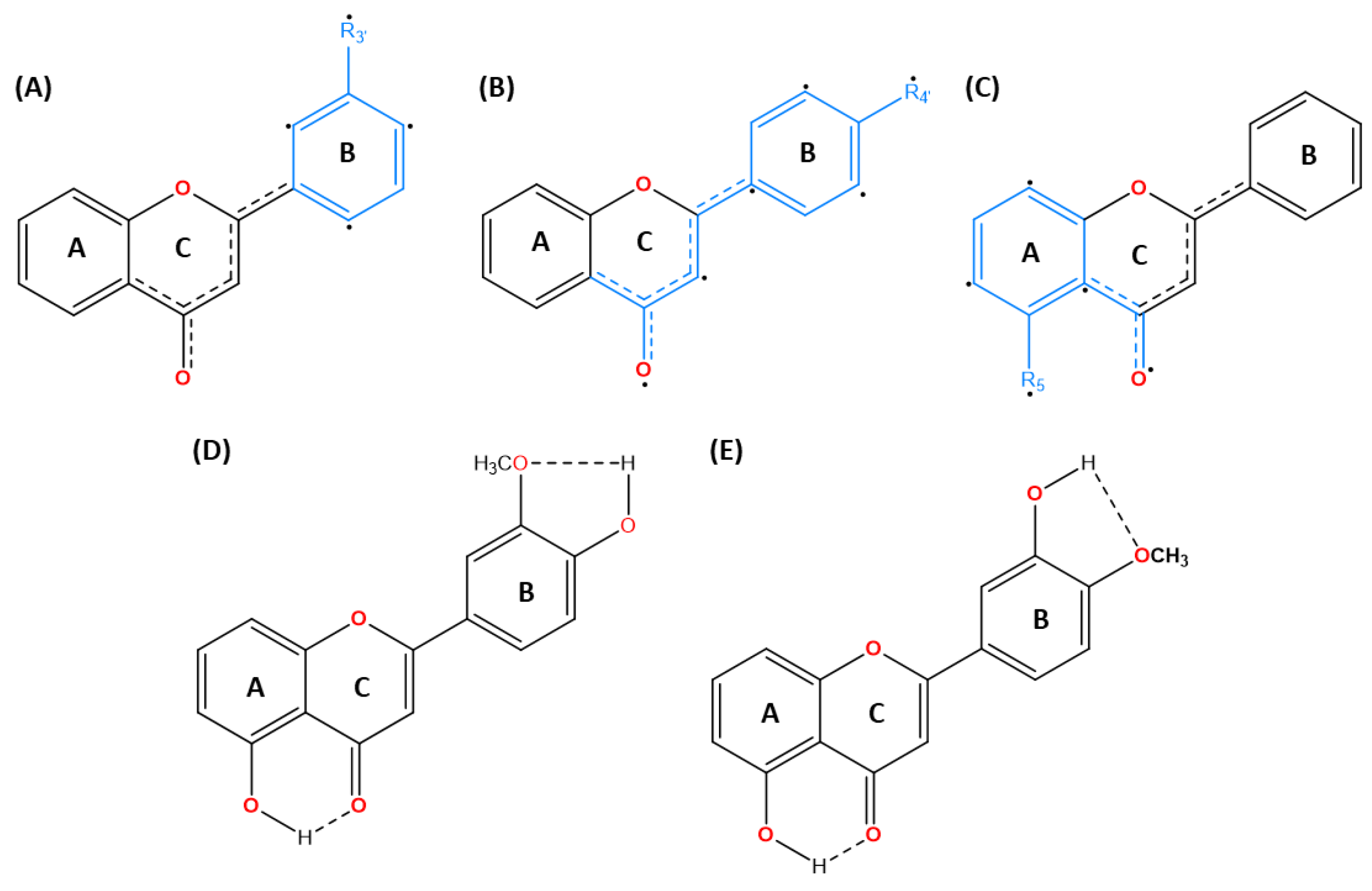

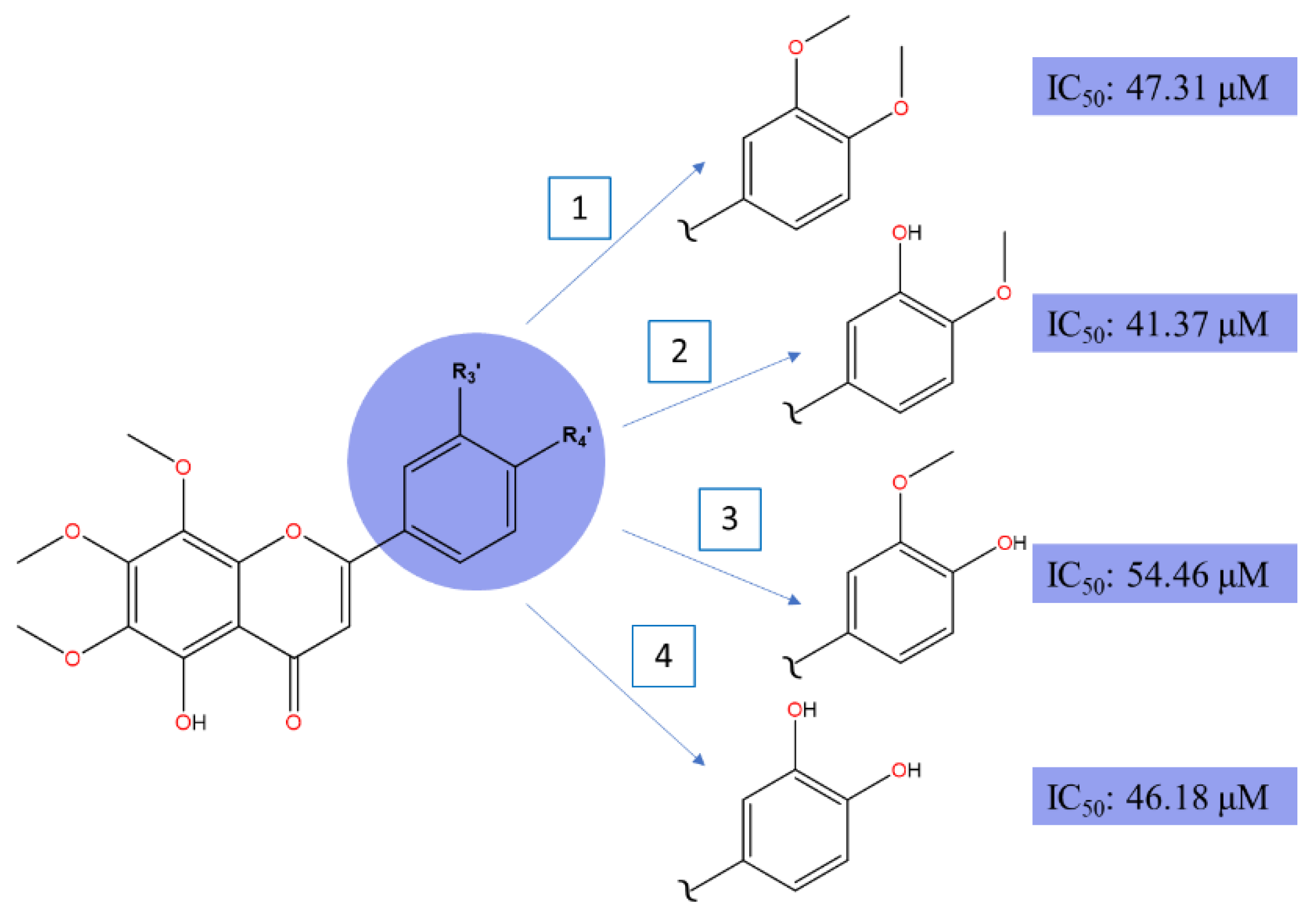

- With C5-OCH3, stronger IC50 could be achieved by either the presence of optimal polar region from -OH moieties or HBA strength of at least one -OCH3 on ring B. Having multiple methoxy moieties on ring B significantly deteriorates the IC50 of the scaffold on numerous cancer cell lines.

- C5-OH, in general, was the most favored to induce strong IC50, with a few exclusions. The established methoxylated backbone on ring A (C6,7 or 8) with the addition of both methoxy and hydroxy moieties in neighboring positions (C3’ & C4’) strengthens the IHB, HBD and HBA effect. Otherwise, the absence of hydroxy moieties on ring B could be offset by the single methoxylated substitution on the same ring. The C3-OCH3 could coalesce, dependent on cell types.

2. SAR and Mechanism of Anticancer Activity of Methoxyflavones Derivatives

2.1. Breast Cancer

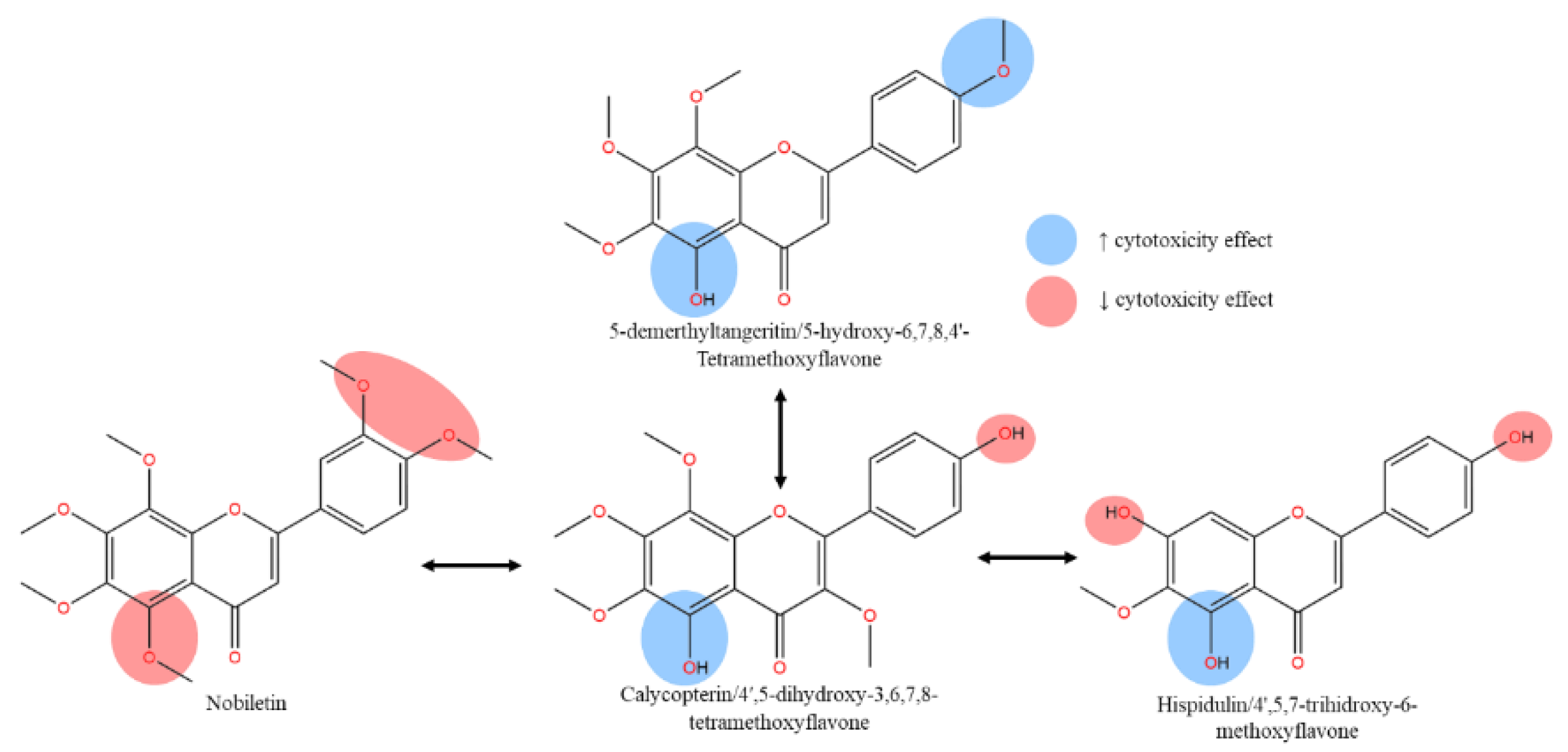

OH methoxyflavones scaffolds, influenced by the C5’-OH. As summarized in Figure 1, excessive methoxylated effect on ring B yielding negative IC50 result on cancer cell lines.

2.2. Prostate Cancer

2.3. Colon Cancer

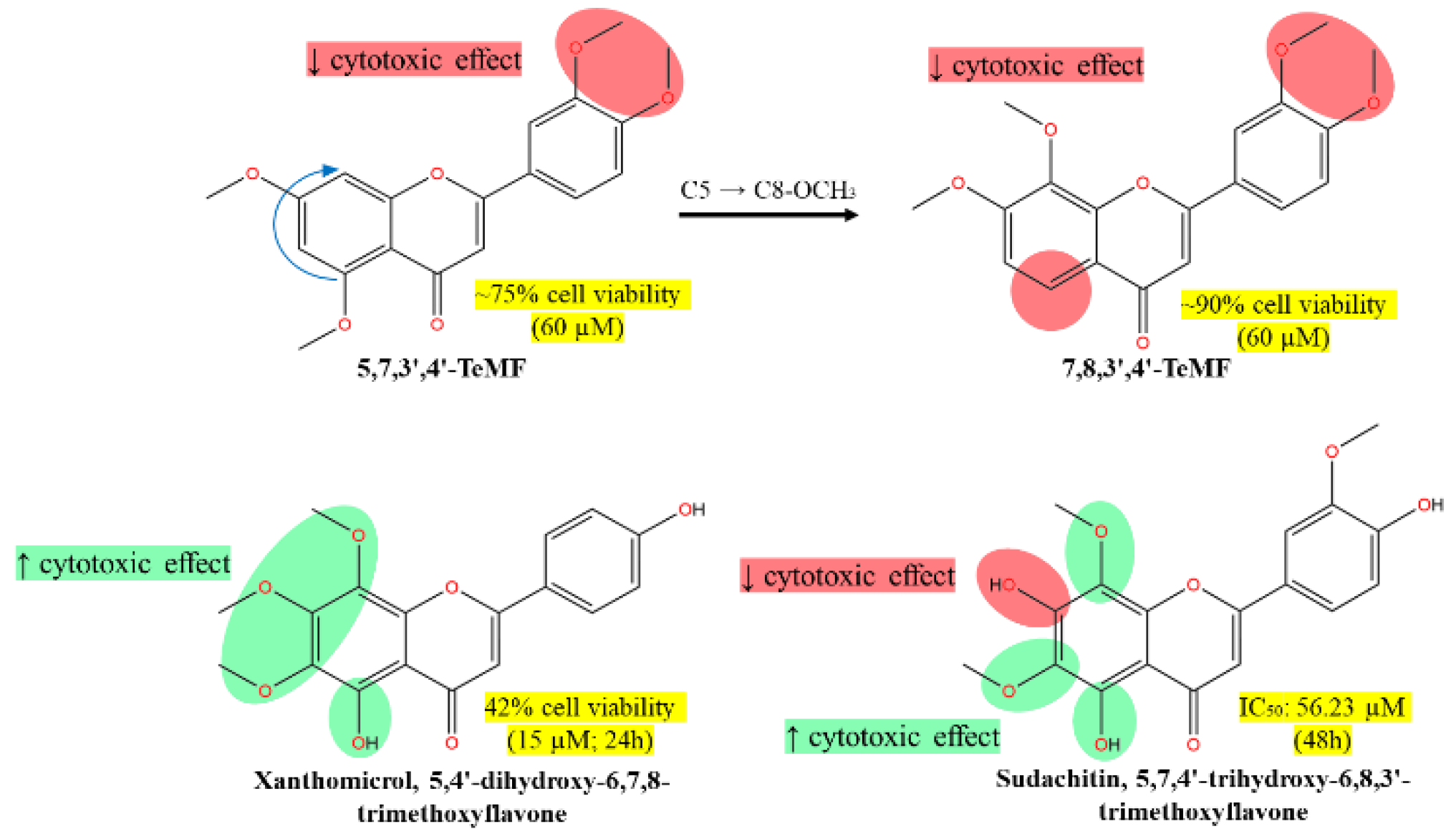

- 5,7,3',4'-TeMF at 60 µM resulting in 75% cell viability, highlighting its moderate cytotoxic effect.

- 7,8,3',4'-TeMF showing a slight reduction in cytotoxic efficacy with about 90% cell viability at the same concentration.

- Xanthomicrol (5,4'-dihydroxy-6,7,8-TMF) and sudachitin (5,7,4'-trihydroxy-6,8,3'-TMF) demonstrating enhanced cytotoxic effects with 42% cell viability at 15 µM and an IC50 of 56.23 µM at 48 hours, respectively.

- The arrows indicate the structural transitions between compounds, noting the shift from C5 to C8-OCH3 and the associated impact on cytotoxicity. Highlighted green regions emphasize the structural components correlated with increased cytotoxic effects, whereas red highlights denote areas associated with decreased effects. This visualization aids in understanding how specific structural modifications influence anticancer activity against HCT116 cells.

2.4. Liver Cancer

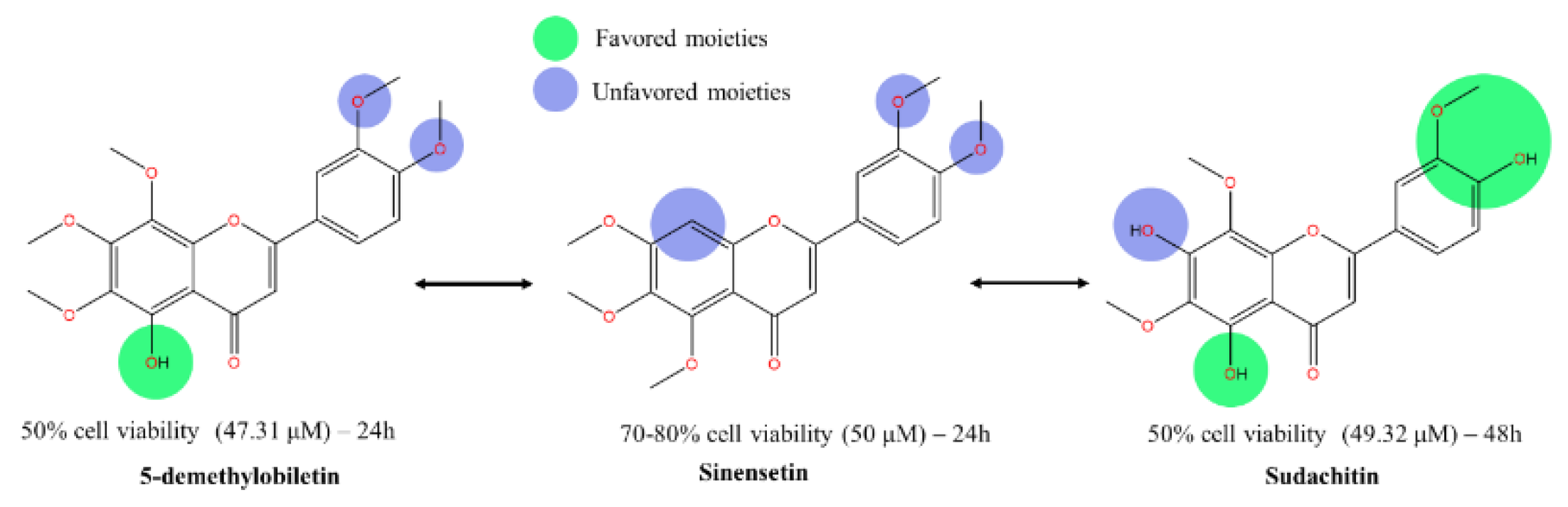

- Favored moieties (green) are indicated on structures where modifications have led to improved cytotoxic activity.

- Unfavored moieties (blue) are shown on structures where modifications have reduced cytotoxic effectiveness.

-

Each compound's impact on cell viability is quantified next to the respective molecular structure, with IC50 values provided:

- o

- 5-demethylnobiletin: 50% cell viability at 47.31 μM over 24 hours.

- o

- Sinensetin: 70-80% cell viability at 50 μM over 24 hours.

- o

- Sudachitin: 50% cell viability at 49.32 μM over 48 hours.

2.5. Acute & Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

- 5,7-dihydroxy-4'-MF (IC50: 9.1 & 6.8 µM)

- 5,4’-dihydroxy-6,7-DMF (IC50: 2.6 & 2.6 µM),

- 5,7-dihydroxy-6,4'-DMF (IC50: 5.9 & 7.9 µM) and

- 5,7,4’-trihydroxy-6-MF/Hispidulin (IC50: 7.0 & 6.8 µM),

2.5.1. Acute and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: C5-OH as a Promising Methoxyflavones’ Anticancer Backbone

2.5.2. Diverse Mechanisms in Different Cell Lines

2.5.3. Comparative Efficacy and Binding Preferences

2.5.4. Casticin's Distinct Cytotoxic Profile

2.6. Gastric Cancer

2.6.1. Physicochemical and SAR Insights

2.6.2. Molecular Interactions and Anticancer Effects

2.7. Skin Cancer

2.8. Oral Cancer

2.8.1. Structural Insights and SAR Analysis

2.8.2. Hydroxylation and its Impact

2.9. Bile duct and Pancreatic Cancer

2.10. Cervical and Ovarian cancer

2.10.1. Cervical Cancer and HPV Infection

2.10.2. Ovarian Cancer and Treatment Efficacy

3. Mechanism of Methoxy and Hydroxy Flavones Derivatives

3.1. Flavones modulate the apoptotic cell death pathway

3.2. Flavones-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest

3.3. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway

3.4. NF-κB Signaling

3.5. Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) cascades signaling

3.6. Autophagy in Cancer

3.7. ER-Stress-Induced Apoptosis By Flavone

3.8. Targeting Topoisomerase Enzymes In Highly Expressed Cancer Cells

3.9. Wnt-β-Catenin Pathway

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Lewandowski, W.; Lewandowska, H.; Golonko, A.; Świderski, G.; Świsłocka, R.; Kalinowska, M. Correlations between molecular structure and biological activity in "logical series" of dietary chromone derivatives. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0229477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutalib, M. A., Shamsuddin, A. S., Ramli, N. N. N., Tang, S. G. H., & Adam, S. H. (2023, May 1). Antiproliferative Activity and Polyphenol Analysis in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicon). https://malaysianjournalofmicroscopy.org/ojs/index.php/mjm/article/view/737.

- Roy, A.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Alghamdi, S.; Rajab, B.S.; Babalghith, A.O.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Islam, S.; Islam, R. Flavonoids a Bioactive Compound from Medicinal Plants and Its Therapeutic Applications. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodowska, K.M. Natural flavonoids: Classification, potential role, and application of flavonoid analogues Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Munir, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Khan, N.; Ghani, L.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. Important Flavonoids and Their Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules 2020, 25, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Garg, A.; Nagendra, C.; Reddy, A.M.; Biswas, R.; Natarajan, R.; Jaisankar, P. In-vitro and in-silico cholinesterase inhibitory activity of bioactive molecules isolated from the leaves of Andrographis nallamalayana J.L. Ellis and roots of Andrographis beddomei C.B. Clarke. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1301, 137406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.L.; Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, T.V.A.; Le, D.H. Potential antiaggregatory and anticoagulant activity of Kaempferia parviflora extract and its methoxyflavones. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 192, 116030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Z. Polymethoxylated flavone variations and in vitro biological activities of locally cultivated Citrus varieties in China. Food Chem. 2024, 463, 141047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Chen, S.; Lin, J.; Bian, J.; Huang, D. Anti-Inflammation Activity of Flavones and Their Structure–Activity Relationship. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7285–7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Ji, F.; Li, Z.; Bian, J. A review on flavones targeting serine/threonine protein kinases for potential anticancer drugs. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, S. C., & David, V. (2022). Characterization of analytes and matrices. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 179–205). [CrossRef]

- Nakhaee, S.; Ghasemi, S.; Karimzadeh, K.; Zamani, N.; Alinejad-Mofrad, S.; Mehrpour, O. The effects of opium on the cardiovascular system: a review of side effects, uses, and potential mechanisms. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Quispe, C.; Patra, J.K.; Singh, Y.D.; Panda, M.K.; Das, G.; Adetunji, C.O.; Michael, O.S.; Sytar, O.; Polito, L.; et al. Paclitaxel: Application in Modern Oncology and Nanomedicine-Based Cancer Therapy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ren, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, X.; Zhang, P.-C. Clinical development and informatics analysis of natural and semi-synthetic flavonoid drugs: A critical review. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 63, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Shahzad, N.; Kim, C.K. Structure-antioxidant activity relationship of methoxy, phenolic hydroxyl, and carboxylic acid groups of phenolic acids. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidiel, M.M.; Maisarah, A.; Khalid, K.; Ramli, N.N.; Tang, S.; Adam, S. Polymethoxyflavones transcends expectation, a prominent flavonoid subclass from Kaempferia parviflora: A critical review. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodi, D.; Ishihara, Y. The role of the methoxy group in approved drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 273, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, X.; Ruan, X.; Kong, L.; Wang, N.; Gao, W.; Wang, R.; Sun, Y.; Jin, M. A deep insight into the structure-solubility relationship and molecular interaction mechanism of diverse flavonoids in molecular solvents, ionic liquids, and molecular solvent/ionic liquid mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 385, 122359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Wu, D.; Yang, L.; Ye, H.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Z.; Tang, K. Exploring the Mechanism of Flavonoids Through Systematic Bioinformatics Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, D.; Pannala, A.; Sandeman, S.; Lloyd, A. Sustained and targeted delivery of hydrophilic drug compounds: A review of existing and novel technologies from bench to bedside. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 78, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Rathi, E.; Kumar, A.; Chawla, K.; Kini, S.G. Identification of DprE1 inhibitors for tuberculosis through integrated in-silico approaches. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, M.; G-Dayanandan, N.; Keshipeddy, S.; Zhou, W.; Si, D.; Reeve, S.; Alverson, J.; Barney, P.; Walker, L.; Hoody, J.; et al. Structure-Guided In Vitro to In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Optimization of Propargyl-Linked Antifolates. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, W. Drug metabolism in drug discovery and development. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Yao, Y.; Dun, B. Biotransformation of Flavonoids Improves Antimicrobial and Anti-Breast Cancer Activities In Vitro. Foods 2021, 10, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štellerová, D.; Michalík, M.; Lukeš, V. Methoxylated flavones with potential therapeutic and photo-protective attributes: Theoretical investigation of substitution effect. Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pan, M.-H.; Lo, C.-Y.; Tan, D.; Wang, Y.; Shahidi, F.; Ho, C.-T. Chemistry and health effects of polymethoxyflavones and hydroxylated polymethoxyflavones. J. Funct. Foods 2008, 1, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, M.; Andruniów, T.; Sroka, Z. Flavones’ and Flavonols’ Antiradical Structure–Activity Relationship—A Quantum Chemical Study. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaadia, L.; Bekkar, Y.; Benamira, M.; Lahmar, H. Predicting the antioxidant activity of some flavonoids of Arbutus plant: A theoretical approach. Chem. Phys. Impact 2020, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, D.J.; Sherman, W.; Tidor, B. Rational Approaches to Improving Selectivity in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1424–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.; Sager, C.P.; Ernst, B. Hydroxyl Groups in Synthetic and Natural-Product-Derived Therapeutics: A Perspective on a Common Functional Group. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 8915–8930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łodyga-Chruścińska, E.; Kowalska-Baron, A.; Błazińska, P.; Pilo, M.; Zucca, A.; Korolevich, V.M.; Cheshchevik, V.T. Position Impact of Hydroxy Groups on Spectral, Acid–Base Profiles and DNA Interactions of Several Monohydroxy Flavanones. Molecules 2019, 24, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiko, A.G.; Lapshina, E.A.; Zavodnik, I.B. Comparative analysis of molecular properties and reactions with oxidants for quercetin, catechin, and naringenin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 4287–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, L.A.; Da Silva, H.C.; De Almeida, W.B. Structural Determination of Antioxidant and Anticancer Flavonoid Rutin in Solution through DFT Calculations of 1H NMR Chemical Shifts. ChemistryOpen 2018, 7, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, A.; Sachithanandam, V.; Lalitha, P.; Elumalai, D.; Asha, R.N.; Jeyakumar, T.C.; Muthukumaran, J.; Jain, M.; Jayabal, K.; Mageswaran, T.; et al. Isolation and biological evaluation 7-hydroxy flavone fromAvicennia officinalisL: insights from extensivein vitro, DFT, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 41, 2848–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M.; Kaur, P.; Shukla, S.; Abbas, A.; Fu, P.; Gupta, S. Plant flavone apigenin inhibits HDAC and remodels chromatin to induce growth arrest and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells: In vitro and in vivo study. Mol. Carcinog. 2011, 51, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohod, S.M.; Kandhare, A.D.; Bodhankar, S.L. Gastroprotective potential of Pentahydroxy flavone isolated from Madhuca indica J. F. Gmel. leaves against acetic acid-induced ulcer in rats: The role of oxido-inflammatory and prostaglandins markers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 182, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J. C. S., De Oliveira, R. G., Silva, V. C., De Sousa, P. T., Jr, Violante, I. M. P., Macho, A., & De Oliveira Martins, D. T. (2018). Anti-inflammatory activity of 4′,6,7-trihydroxy-5-methoxyflavone from Fridericia chica (Bonpl.) L.G.Lohmann. Natural Product Research, 34(5), 726–730. [CrossRef]

- Phung, H.M.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Jung, K.; Kang, K.S. Protective Effect of Polymethoxyflavones Isolated from Kaempferia parviflora against TNF-α-Induced Human Dermal Fibroblast Damage. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Over, B.; McCarren, P.; Artursson, P.; Foley, M.; Giordanetto, F.; Grönberg, G.; Hilgendorf, C.; Lee, M.D.; Matsson, P.; Muncipinto, G.; et al. Impact of Stereospecific Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding on Cell Permeability and Physicochemical Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2746–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, A.; Millan, D.S.; Perez, M.; Wakenhut, F.; Whitlock, G.A. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding to improve membrane permeability and absorption in beyond rule of five chemical space. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinska-Roszak, D. Energy of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding in ortho-Hydroxybenzaldehydes, Phenones and Quinones. Transfer of Aromaticity from ipso-Benzene Ring to the Enol System(s). Molecules 2017, 22, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogianni, V.G.; Charisiadis, P.; Primikyri, A.; Pappas, C.G.; Exarchou, V.; Tzakos, A.G.; Gerothanassis, I.P. Hydrogen bonding probes of phenol –OH groups. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 11, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.J.; Mobli, M. An NMR, IR and theoretical investigation of 1H Chemical Shifts and hydrogen bonding in phenols. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2007, 45, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, W.L.; Okoso-Amaa, E.M.; Womack, C.L.; Vladimirova, A.; Rogers, L.B.; Risher, M.J.; Abraham, M.H. Summation Solute Hydrogen Bonding Acidity Values for Hydroxyl Substituted Flavones Determined by NMR Spectroscopy. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huque, F. T. T., & Platts, J. A. (2003). The effect of intramolecular interactions on hydrogen bond acidityElectronic supplementary information (ESI) available: summary of retrained regression using DFT methods. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 1(8), 1419–1424. [CrossRef]

- Carcache, P.J.B.; Eugenio, G.D.A.; Ninh, T.N.; Moore, C.E.; Rivera-Chávez, J.; Ren, Y.; Soejarto, D.D.; Kinghorn, A.D. Cytotoxic constituents of Glycosmis ovoidea collected in Vietnam. Fitoterapia 2022, 162, 105265–105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aamri, H.M.; Irving, H.R.; Bradley, C.; Meehan-Andrews, T. Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis responses in leukaemia cells following daunorubicin treatment. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şöhretoğlu, D.; Barut, B.; Sari, S.; Özel, A.; Arroo, R. In vitro and in silico assessment of DNA interaction, topoisomerase I and II inhibition properties of chrysosplenetin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotillo, W.S.; Tarqui, S.; Huang, X.; Almanza, G.; Oredsson, S. Breast cancer cell line toxicity of a flavonoid isolated from Baccharis densiflora. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyanabe, K.; Akiba, H.; Kuroda, D.; Nakakido, M.; Kusano-Arai, O.; Iwanari, H.; Hamakubo, T.; Caaveiro, J.M.M.; Tsumoto, K. Intramolecular H-bonds govern the recognition of a flexible peptide by an antibody. J. Biochem. 2018, 164, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vicente, J.; Lemoine, R.; Bartlett, M.; Hermann, J.C.; Hekmat-Nejad, M.; Henningsen, R.; Jin, S.; Kuglstatter, A.; Li, H.; Lovey, A.J.; et al. Scaffold hopping towards potent and selective JAK3 inhibitors: Discovery of novel C-5 substituted pyrrolopyrazines. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 4969–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Koga, Y.; Hikota, M.; Matsuki, K.; Murakami, M.; Kikkawa, K.; Fujishige, K.; Kotera, J.; Omori, K.; Morimoto, H.; et al. Design and synthesis of novel 5-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl)-4-aminopyrimidine derivatives as potent and selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors: Scaffold hopping using a pseudo-ring by intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5175–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettorre, A.; D’andrea, P.; Mauro, S.; Porcelloni, M.; Rossi, C.; Altamura, M.; Catalioto, R.M.; Giuliani, S.; Maggi, C.A.; Fattori, D. hNK2 receptor antagonists. The use of intramolecular hydrogen bonding to increase solubility and membrane permeability. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 1807–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, A.F.; Lightner, D.A. Influence of Conformation and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding on the Acyl Glucuronidation and Biliary Excretion of Acetylenic Bis-Dipyrrinones Related to Bilirubin. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilek, B.; Meltem, . Quercetin suppresses cell proliferation using the apoptosis pathways in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma cells in monolayer and spheroid model cultures. South Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 162, 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Lee, W.S.; Eun, S.Y.; Park, H.-S.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y.H.; Ryu, C.H.; Jung, J.M.; Hong, S.C.; Shin, S.C.; et al. Morin, a flavonoid from Moraceae, suppresses growth and invasion of the highly metastatic breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 partly through suppression of the Akt pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chung, J.-G.; Yang, J.-S.; Lu, H.-F.; Tsou, M.-F.; Wood, W.; Kuo, S.-J.; Chen, D.-R. Quercetin-induced apoptosis acts through mitochondrial- and caspase-3-dependent pathways in human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2009, 28, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongdeth, K.; Han, P.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.-A. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Natural and Non-Natural Polymethoxychalcones and Polymethoxyflavones. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2019, 55, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.d.A.; Sandim, V.; Fernandes, T.F.B.; Almeida, V.H.; Rocha, M.R.; Amaral, R.J.F.C.D.; Rossi, M.I.D.; Kalume, D.E.; Zingali, R.B. Proteomic Analysis of HCC-1954 and MCF-7 Cell Lines Highlights Crosstalk between αv and β1 Integrins, E-Cadherin and HER-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amić, D., Davidović-Amić, D., Bešlo, D. and Trinajstić, N. (2003). Structure-Radical Scavenging Activity Relationships of Flavonoids. Croatica Chemica Acta, 76(1), 55-61. https://hrcak.srce.hr/103057.

- Heijnen, C.; Haenen, G.; van Acker, F.; van der Vijgh, W.; Bast, A. Flavonoids as peroxynitrite scavengers: the role of the hydroxyl groups. Toxicol. Vitr. 2001, 15, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, D.; Đorović, J.; Petrović, V.; Avdović, E.; Marković, Z. Hydrogen atom transfer versus proton coupled electron transfer mechanism of gallic acid with different peroxy radicals. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2017, 123, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-Y.; Yang, J.-F.; Chen, Y.-B.; Guo, J.-L.; Li, S.; Wei, G.-J.; Ho, C.-T.; Hsu, J.-L.; Chang, C.-I.; Liang, Y.-S.; et al. Acetylation Enhances the Anticancer Activity and Oral Bioavailability of 5-Demethyltangeretin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, W.L.; Rummel, J.D.; Kastrapeli, N. Interactions of Genistein and Related Isoflavones with Lipid Micelles. Langmuir 2006, 22, 7175–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ren, X.; Patel, N.; Xu, X.; Wu, P.; Liu, W.; Zhang, K.; Goodin, S.; Li, D.; Zheng, X. Nobiletin, a citrus polymethoxyflavone, enhances the effects of bicalutamide on prostate cancer cellsviadown regulation of NF-κB, STAT3, and ERK activation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 10254–10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, J.; Opazo, J.; Mendoza, L.; Urzúa, A.; Wilkens, M. Structure-Activity and Lipophilicity Relationships of Selected Antibacterial Natural Flavones and Flavanones of Chilean Flora. Molecules 2017, 22, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Jia, Y.; Yu, X.; Mou, R.; Li, X. Hispidulin inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion by promoting autophagy via regulation of PPARγ activation in prostate cancer cells and xenograft models. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 85, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chen, K.; Tsai, C.; Tsai, F.; Huang, C.; Tang, C.; Yang, J.; Hsu, Y.; Peng, S.; Chung, J. Casticin inhibits human prostate cancer DU 145 cell migration and invasion via Ras/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathways. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfizadeh, R.; Sepehri, H.; Attari, F.; Delphi, L. Flavonoid Calycopterin Induces Apoptosis in Human Prostate Cancer Cells In-vitro. IJPR 2020, 19, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, R.; Bhagyaraj, E.; Tiwari, D.; Nanduri, R.; Chacko, A.P.; Jain, M.; Mahajan, S.; Khatri, N.; Gupta, P. AIRE promotes androgen-independent prostate cancer by directly regulating IL-6 and modulating tumor microenvironment. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, B.J.; Feldman, D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.C.; Shin, E.A.; Kim, B.; Kim, B.-I.; Chitsazian-Yazdi, M.; Iranshahi, M.; Kim, S.-H. Auraptene Induces Apoptosis via Myeloid Cell Leukemia 1-Mediated Activation of Caspases in PC3 and DU145 Prostate Cancer Cells. Phytotherapy Res. 2017, 31, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Hu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Shen, G. Curcumin induces apoptosis and protective autophagy in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells through iron chelation. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, ume11, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, O.; Turut, F.A.; Acidereli, H.; Yildirim, S. Cyclosporine-A induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells PC3 and DU145 via downregulation of COX-2 and upregulation of TGFβ. Turk. J. Biochem. 2018, 44, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-L.; Zhang, Y.-J.; He, L.-J.; Hu, C.-S.; Gao, L.-X.; Huang, J.-H.; Tang, Y.; Luo, J.; Tang, D.-Y.; Chen, Z.-Z. Demethylzeylasteral (T-96) initiates extrinsic apoptosis against prostate cancer cells by inducing ROS-mediated ER stress and suppressing autophagic flux. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’arrigo, G.; Gianquinto, E.; Rossetti, G.; Cruciani, G.; Lorenzetti, S.; Spyrakis, F. Binding of Androgen- and Estrogen-Like Flavonoids to Their Cognate (Non)Nuclear Receptors: A Comparison by Computational Prediction. Molecules 2021, 26, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousi, M.S.; Sepehri, H.; Khoee, S.; Farimani, M.M.; Delphi, L.; Mansourizadeh, F. Evaluation of apoptotic effects of mPEG-b-PLGA coated iron oxide nanoparticles as a eupatorin carrier on DU-145 and LNCaP human prostate cancer cell lines. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 11, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Marcoccia, D.; Narciso, L.; Mantovani, A.; Lorenzetti, S. Intracellular distribution and biological effects of phytochemicals in a sex steroid- sensitive model of human prostate adenocarcinoma. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, A.B.; Mir, H.; Kapur, N.; Gales, D.N.; Carriere, P.P.; Singh, S. Quercetin inhibits prostate cancer by attenuating cell survival and inhibiting anti-apoptotic pathways. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, S.-I.; Inenaga, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Tanaka-Mizota, C. Suppression of HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cell Motility by Polymethoxyflavones is Associated with Inhibition of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, F.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Xiao, H. Identification of Xanthomicrol as a Major Metabolite of 5-Demethyltangeretin in Mouse Gastrointestinal Tract and Its Inhibitory Effects on Colon Cancer Cells. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Tsao, E.-C.; Chen, Y.-T.; Wu, M.-J.; Ho, C.-T.; Yen, J.-H. 5-Demethylnobiletin Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Downregulates ID1 Expression, Modulates the NF-κB/TNF-α Pathway and Exerts Antileukemic Effects in AML Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieddu, M.; Pollastro, F.; Caria, P.; Salamone, S.; Rosa, A. Xanthomicrol Activity in Cancer HeLa Cells: Comparison with Other Natural Methoxylated Flavones. Molecules 2023, 28, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, S.; Li, D.; Zhao, D.; Ma, Y.; Ho, C.-T.; Huang, Q. Demethylnobiletin and its major metabolites: Efficient preparation and mechanism of their anti-proliferation activity in HepG2 cells. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2022, 11, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naróg, D.; Sobkowiak, A. Electrochemistry of Flavonoids. Molecules 2023, 28, 7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Ha, S.E.; Lee, H.J.; Rampogu, S.; Vetrivel, P.; Kim, H.H.; Venkatarame Gowda Saralamma, V.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, G.S. Sinensetin Induces Autophagic Cell Death through p53-Related AMPK/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma HepG2 Cells. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Nishi, M.; Morine, Y.; Yoshikawa, K.; Tokunaga, T.; Kashihara, H.; Takasu, C.; Wada, Y.; Yoshimoto, T.; Nakamoto, A.; et al. Polymethoxylated flavone sudachitin is a safe anticancer adjuvant that targets glycolysis in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S.-C.; Chen, L.-C.; Huang, H.-L.; Ngo, S.-T.; Wu, Y.-W.; Lin, T.E.; Sung, T.-Y.; Lien, S.-T.; Tseng, H.-J.; Pan, S.-L.; et al. Investigation of Selected Flavonoid Derivatives as Potent FLT3 Inhibitors for the Potential Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfwuaires, M.; Elsawy, H.; Sedky, A. Acacetin Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Lines. Molecules 2022, 27, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novatcheva, E.D.; Anouty, Y.; Saunders, I.; Mangan, J.K.; Goodman, A.M. FMS-Like Tyrosine Kinase 3 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021, 22, e161–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruglioni, M.; Crucitta, S.; Luculli, G.I.; Tancredi, G.; Del Giudice, M.L.; Mechelli, S.; Galimberti, S.; Danesi, R.; Del Re, M. Understanding mechanisms of resistance to FLT3 inhibitors in adult FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia to guide treatment strategy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2024, 201, 104424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Xu, B.; Qiu, Y. Low-frequency TP53 hotspot mutation contributes to chemoresistance through clonal expansion in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2020, 34, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skopek, R.; Palusińska, M.; Kaczor-Keller, K.; Pingwara, R.; Papierniak-Wyglądała, A.; Schenk, T.; Lewicki, S.; Zelent, A.; Szymański, Ł. Choosing the Right Cell Line for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, K.; Everaus, H. Established Human Cell Lines as Models to Study Anti-leukemic Effects of Flavonoids. Curr. Genom. 2016, 18, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandur, E.; Micalizzi, G.; Mondello, L.; Horváth, A.; Sipos, K.; Horváth, G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) Essential Oils Prepared at Different Plant Phenophases on Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS-Activated THP-1 Macrophages. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, S.; Bar-Natan, M.; Mascarenhas, J.O. JAKs to STATs: A tantalizing therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Rev. 2019, 40, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rosario, H.; Saavedra, E.; Brouard, I.; González-Santana, D.; García, C.; Spínola-Lasso, E.; Tabraue, C.; Quintana, J.; Estévez, F. Structure-activity relationships reveal a 2-furoyloxychalcone as a potent cytotoxic and apoptosis inducer for human U-937 and HL-60 leukaemia cells. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 127, 105926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chuang, C.-H.; Chin, H.-K.; Wu, M.-J.; Chen, P.-Y. Nobiletin Promotes Megakaryocytic Differentiation through the MAPK/ERK-Dependent EGR1 Expression and Exerts Anti-Leukemic Effects in Human Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) K562 Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Nuaimi, A.; Al-Hiari, Y.; Kasabri, V.; Haddadin, R.; Mamdooh, N.; Alalawi, S.; Khaleel, S. A Novel Class of Functionalized Synthetic Fluoroquinolones with Dual Antiproliferative - Antimicrobial Capacities. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cytotoxicity evaluation and the mode of cell death of K562 cells induced by organotin (IV) (2-methoxyethyl) methyldithiocarbamate compounds. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Chueh, F.; Peng, S.; Lin, C.; Kuo, C.; Huang, W.; Chen, P.; Way, T.; Chung, J. Combinational treatment of 5-fluorouracil and casticin induces apoptosis in mouse leukemia WEHI-3 cells in vitro. Environ. Toxicol. 2020, 35, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Cao, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, C. Polymethoxyflavones from citrus inhibited gastric cancer cell proliferation through inducing apoptosis by upregulating RARβ, both in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragi, C.; Muraleedharan, K. Hydrogen bonding interactions between Hibiscetin and ethanol/water: DFT studies on structure and topologies. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Júnior, R.G.; Marcoult-Fréville, N.; Prunier, G.; Beaugeard, L.; Filho, E.B.d.A.; Mourão, E.D.S.; Michel, S.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Almeida, J.R.G.d.S.; Grougnet, R.; et al. Polymethoxyflavones from Gardenia oudiepe (Rubiaceae) induce cytoskeleton disruption-mediated apoptosis and sensitize BRAF-mutated melanoma cells to chemotherapy. Chem. Interactions 2020, 325, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawa, J.W.; Jakimiuk, K.; Szoka, Ł.; Brzezinski, K.; Drozdzal, P.; Pałka, J.A.; Tomczyk, M. New Polymethoxyflavones from Hottonia palustris Evoke DNA Biosynthesis-Inhibitory Activity in An Oral Squamous Carcinoma (SCC-25) Cell Line. Molecules 2022, 27, 4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Lin, J.; Yu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Bi, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; et al. Nobiletin suppresses cholangiocarcinoma proliferation via inhibiting GSK3β. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5698–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Wu, P.; Liu, W.; Zhang, K.; Goodin, S.; Li, D.; Zheng, X. Nobiletin Inhibits Cell Growth, Migration and Invasion, and Enhances the Anti-Cancer Effect of Gemcitabine on Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ji, H.; Wang, Z.-W.; Zhu, X. Discovery of key genes as novel biomarkers specifically associated with HPV-negative cervical cancer. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 21, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Kundu, R. Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: The Cervical Cancer Hallmarks and Targets for Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narisawa-Saito, M.; Kiyono, T. Basic mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis: Roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Quan, Y.; Bai, Y.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y. The effect and apoptosis mechanism of 6-methoxyflavone in HeLa cells. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Quan, Y.; Yang, L.; Bai, Y.; Yang, Y. 6-Methoxyflavone induces S-phase arrest through the CCNA2/CDK2/p21CIP1 signaling pathway in HeLa cells. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 7277–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Sun, C.; Luo, N.; He, Y.; Chen, M.; Ding, S.; Liu, C.; Feng, L.; Cheng, Z. Wogonin Increases Cisplatin Sensitivity in Ovarian Cancer Cells Through Inhibition of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)/Akt Pathway. Med Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 6007–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., Kim, Y., Ji, Z., Kang, J., Wirianto, M., Paudel, K. R., Smith, J. A., Ono, K., Kim, J., Eckel-Mahan, K., Zhou, X., Lee, H. K., Yoo, J. Y., Yoo, S., & Chen, Z. (2022). ROR activation by Nobiletin enhances antitumor efficacy via suppression of IκB/NF-κB signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death and Disease, 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Zehra, B.; Ahmed, A.; Sarwar, R.; Khan, A.; Farooq, U.; Ali, S.A.; Al-Harrasi, A. Apoptotic and antimetastatic activities of betulin isolated from Quercus incana against non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, ume 11, 1667–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, W.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Q.; Gao, Y.; Lu, N. Oroxylin A suppresses ACTN1 expression to inactivate cancer-associated fibroblasts and restrain breast cancer metastasis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.; Lin, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Han, S.; Huang, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Nobiletin Induces Ferroptosis in Human Skin Melanoma Cells Through the GSK3β-Mediated Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 Signalling Pathway. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 865073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldar, S.; Khaniani, M.S.; Derakhshan, S.M.; Baradaran, B. Molecular Mechanisms of Apoptosis and Roles in Cancer Development and Treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 2129–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, S.; Wei, Z.; Yang, W.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. The role of BCL-2 family proteins in regulating apoptosis and cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 985363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell cycle regulation: p53-p21-RB signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Cao, J.; Lin, W.; Chen, H.; Xiong, X.; Ao, H.; Yu, M.; Lin, J.; Cui, Q. The Roles of Cyclin-Dependent Kinases in Cell-Cycle Progression and Therapeutic Strategies in Human Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duo, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ma, Z.; Farjudian, A.; Ho, W.Y.; Low, S.S.; Ren, J.; Hirst, J.D.; Xie, H.; et al. Discovery of novel SOS1 inhibitors using machine learning. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, U.R.; Todaro, G.J. Generation of New Mouse Sarcoma Viruses in Cell Culture. Science 1978, 201, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, M.; Lopez, A.; Lin, E.; Sales, D.; Perets, R.; Jain, P. Progress on Ras/MAPK Signaling Research and Targeting in Blood and Solid Cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Dong, X.; Yap, J.; Hu, J. The MAPK and AMPK signalings: interplay and implication in targeted cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Steelman, L.S.; Lee, J.T.; Shelton, J.G.; Navolanic, P.M.; Blalock, W.L.; A Franklin, R.; A McCubrey, J. Signal transduction mediated by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway from cytokine receptors to transcription factors: potential targeting for therapeutic intervention. Leukemia 2003, 17, 1263–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, L.M.; Chattopadhyay, M.; Li, Y.; Scarlata, S.; Lin, R.Z. Gαq binds to p110α/p85α phosphoinositide 3-kinase and displaces Ras. Biochem. J. 2006, 394, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Li, W.; Zou, D.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Wong, C.C. Transcription factors in colorectal cancer: molecular mechanism and therapeutic implications. Oncogene 2020, 40, 1555–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheau, O.; Tschopp, J. Induction of TNF Receptor I-Mediated Apoptosis via Two Sequential Signaling Complexes. Cell 2003, 114, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Sun, L.; Xu, F. NF-κB in Cell Deaths, Therapeutic Resistance and Nanotherapy of Tumors: Recent Advances. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, E.S.; El-Bsoumy, E.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Helal, M.A.; El-Magd, M.A.; Ahmed, S.A. Anti-inflammatory effect of methoxyflavonoids fromChiliadenus montanus(Jasonia Montana)growing in Egypt. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 5909–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.D.S.S.; Behrens, M.D.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Penedo, G.X.M.; Silva, A.R.; Gonçalves-De-Albuquerque, C.F. Flavonols and Flavones as Potential anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Compounds. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobeil, S.; Boucher, C.C.; Nadeau, D.; Poirier, G.G. Characterization of the necrotic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1): implication of lysosomal proteases. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbulan-Rosenthal, C.M.; Rosenthal, D.S.; Iyer, S.; Boulares, A.H.; Smulson, M.E. Transient Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of Nuclear Proteins and Role of Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase in the Early Stages of Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 13703–13712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Paskeh, M.D.A.; Mirzaei, S.; Gholami, M.H.; Zarrabi, A.; Hashemi, F.; Hushmandi, K.; Hashemi, M.; Nabavi, N.; Crea, F.; et al. Targeting autophagy in prostate cancer: preclinical and clinical evidence for therapeutic response. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; Hanif, E.A.M.; Chin, S.-F. Is targeting autophagy mechanism in cancer a good approach? The possible double-edge sword effect. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aziz, Y.S.A.; Leck, L.Y.W.; Jansson, P.J.; Sahni, S. Emerging Role of Autophagy in the Development and Progression of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Gibson, S.B. Regulation of Autophagy by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Implications for Cancer Progression and Treatment. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.-Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.-B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Cubillos-Ruiz, J.R. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 21, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Liang, M.-X.; Fei, Y.-J.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Tang, J.-H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress targeted therapy for breast cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, E.; Logue, S.E.; Healy, S.J.; Manie, S.; Samali, A. The role of the unfolded protein response in cancer progression: From oncogenesis to chemoresistance. Biol. Cell 2019, 111, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qu, L.; Meng, L.; Shou, C. Topoisomerase inhibitors promote cancer cell motility via ROS-mediated activation of JAK2-STAT1-CXCL1 pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakkala, P.A.; Penumallu, N.R.; Shafi, S.; Kamal, A. Prospects of Topoisomerase Inhibitors as Promising Anti-Cancer Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Lv, J.; Sun, D.; Huang, Y. Therapeutic strategies targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling for colorectal cancer (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koury, J.; Zhong, L.; Hao, J. Targeting Signaling Pathways in Cancer Stem Cells for Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, L.; Kril, L.M.; Begley, K.L.; Sviripa, V.M.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Lee, E.Y.; He, D.; et al. Potent Synergistic Effect on C-Myc-Driven Colorectal Cancers Using a Novel Indole-Substituted Quinoline with a Plk1 Inhibitor. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 1893–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Prostate cancer cell lines | C3 | C5 | C7 | C8 | C3’ | C4’ | IC50 (µM) / Cell viability (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC3 | H | OMe | OMe | OMe | H | OMe | 17.2 | [63] |

| H | OH | OMe | OMe | H | OMe | 11.8 | ||

| H | OMe | OMe | OMe | OMe | OMe | 80.0 | [65] | |

| VCaP | H | OMe | OMe | OMe | OMe | OMe | > 80% (120 µM) | |

| H | OH | OH | H | H | OH | >50% (50 µM) | [67] | |

| DU145 | OMe | OH | OMe | H | OH | OMe | < 80% (50 µM) | [68] |

| OMe | OH | OMe | OMe | H | OH | 235.0 | [69] | |

| LNCaP | OMe | OH | OMe | OMe | H | OH | 116.5 |

| Sample | IC50 (µM) / cell viability (%) | Reference | |

| PC3 | DU145 | ||

| Auraptene | <50% (120 µM) | <50% (120 µM) | [72] |

| Curcumin | <60% (50 µM) | <60% (50 µM) | [73] |

| Cyclosporine-A | 8.80 μM | 12.14 μM | [74] |

| Demethylzeylasteral (T-96) | 13.10 µM | 11.47 µM | [75] |

| Natural sources | Cancer | Cells | Treatment (hr) | IC50 / % cell viability (%, µM) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

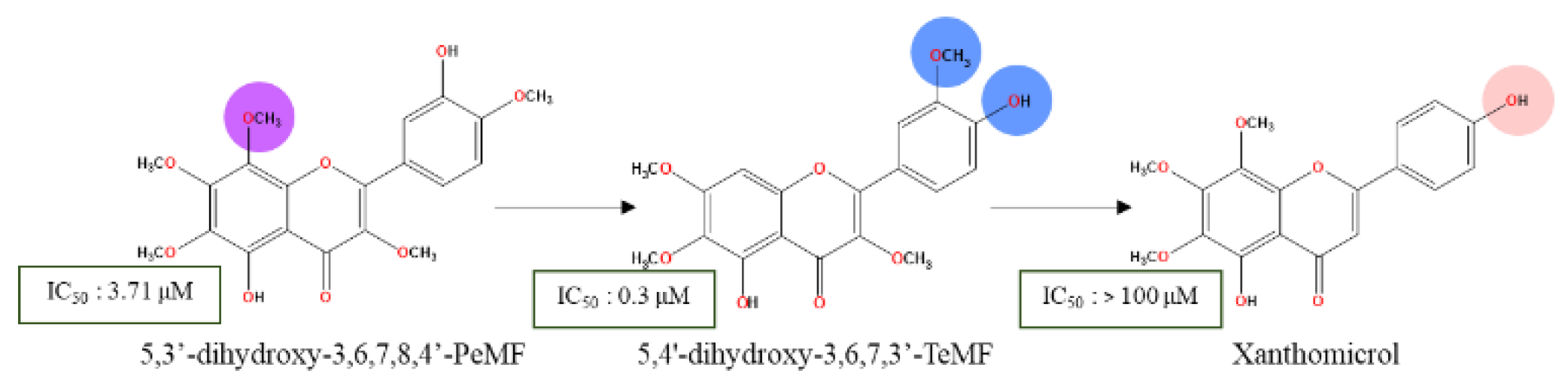

| 5,3’-dihydroxy-3,6,7,8,4’-PeMF | Glycosmis ovoidea Pierre | Breast | MCF-7 | 24 | 49.46 µM | [46] |

| 48 | 17.56 µM | |||||

| 72 | 3.71 µM | |||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 24 | 49.46 µM | ||||

| 48 | 49.46 µM | |||||

| 72 | 21.27 µM | |||||

| Nobiletin | Citrus sinensis / Citrus reticulata | Gastric | AGS | 48 | >20% (62.13 µM) | [102] |

| BGC-823 | >90% (100 µM) | |||||

| SGC-7901 | >90% (100 µM) | |||||

| CML | K562 | 48 | 82.49 µM | [98] | ||

| Prostate | VCaP | 48 | > 80% (100 µM) | [65] | ||

| PC3 | 48 | 80 - 100 µM | [63] | |||

| Pancreas | MIA PaCa-2 | 72 | 80% (120 µM) | [107] | ||

| PANC-1 | 72 | 20% (80 µM) | ||||

| Breast | MDA-MB-231 | 72 | 70% (10.04 µM) | [114] | ||

| Bile duct | TFK1 | 48 | Inactive | [82] | ||

| RBE | 48 | Inactive | ||||

| Compound | ||||||

| 5-demethylnobiletin | Citrus reticulata | Liver | HepG2 | 24 | 47.31 µM | [84] |

| AML | HL-60 | 48 | 85.7 µM | [98] | ||

| THP-1 | 32.3 µM | |||||

| U-937 | 30.4 µM | |||||

| HEL | 65.3 µM | |||||

| CML | K562 | 91.5 µM | ||||

| Gastric | AGS | >90% (100 µM) | [102] | |||

| BGC-823 | >90% (100 µM) | |||||

| SGC-7901 | >90% (100 µM) | |||||

| 5,7,4'-trihydroxy-6,8,3'-TMF / sudachitin | Citrus sudachi | Colon | HCT116 | 48 | 56.23 µM | [87] |

| HT-29 | 48 | 37.07 µM | ||||

| Liver | HepG2 | 48 | 49.32 µM | |||

| Bile duct | HuCCT1 | 48 | 53.21 µM | |||

| RBE | 48 | 24.1 µM | ||||

| Pancreas | MIA PaCa-2 | 48 | 43.35 µM | |||

| PANC-1 | 48 | 32.73 µM | ||||

| 5,6′-dihydroxy-2′,3′-DMF | Hottonia palustris | Oral | SCC-25 | 24 | 78.2 µM | [105] |

| 5,6′-dihydroxy-2′,3′-DMF | 48 | 40.6 µM | ||||

| 5-hydroxy-2′-MF | Inactive | |||||

| 5-hydroxy-2′,6′-DMF | Inactive | |||||

| 5-hydroxy-2′,3′,6′-TMF | Inactive | |||||

| 5,2'-dihydroxy-6'-MF | Inactive | |||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-4'-MF / acacetin | Robinia pseudoacacia | MOLM-13 | 72 | 9.1 µM | [88] | |

| 5,4’-dihydroxy-6,7-DMF | Quercus incana | 2.6 µM | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-6,4'-DMF / Pectolinarigenin | Artemisia capillaris | 5.9 µM | ||||

| 5,7,4’-trihydroxy-6-MF/ hispidulin | Artemisia capillaris | 7.0 µM | ||||

| 5,7,4’-trihydroxy-6-MF/hispidulin | Artemisia capillaris | MV4-11 | 6.8 µM | |||

| 5,4’-dihydroxy-6,7-DMF | Quercus incana | 2.6 µM | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-6,4'-DMF / Pectolinarigenin | Artemisia capillaris | 7.9 µM | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-4'-MF | Robinia pseudoacacia | 6.8 µM | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-3,6,4'-TMF | Gardenia oudiepe (Rubiaceae) | Skin | A2058 | 72 | 66.52% (10 µM) | [104] |

| 7,5'-dihydroxy-3,6,3',4'-TeMF | 72 | 42.86% (10 µM) | ||||

| 5,7,4’-trihydroxy-3,6-DMF | 72 | Inactive | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-3,6,3’,4’,5’-PeMF | 72 | Inactive | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-8-MF / wogonin | Scutellaria baicalensis | Ovarian | SKOV3 | 72 | 80% (20 µM) | [113] |

| OV2008 | ||||||

| SKOV3/DDP | ||||||

| C13* | ||||||

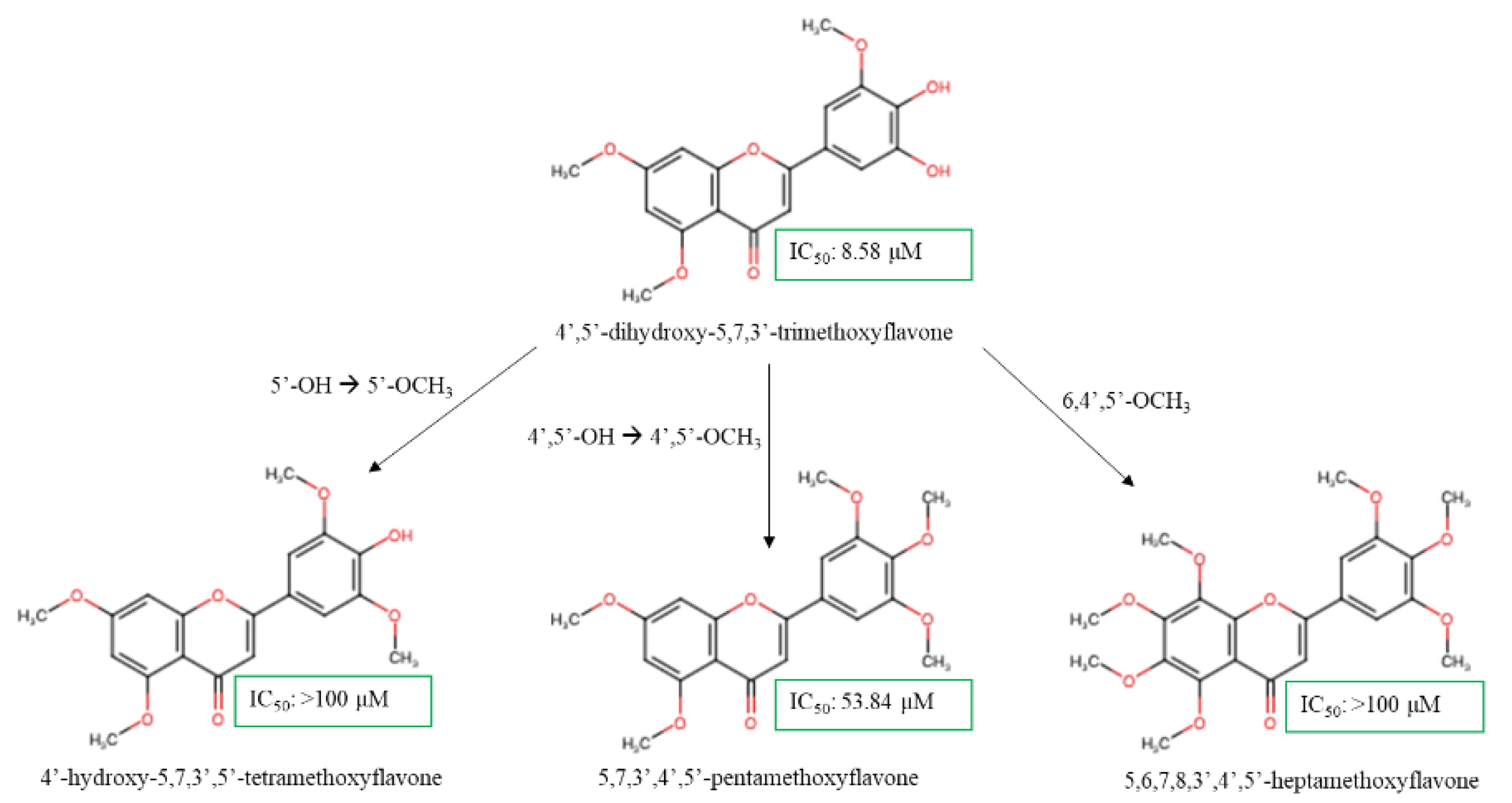

| 4',5'-dihydroxy-5,7,3'-TMF | Synthetic compound | Breast | HCC1954 | NA | 8.58 µM | [58] |

| 4'-hydroxy-5,7,3',5'-TeMF | >100 µM | |||||

| 5,7,3',4',5'-PeMF | 53.84 µM | |||||

| 5,6,7,8,3',4',5'-heptamethoxyflavone | >100 µM | |||||

| 5,6,7,8,4'-PeMF / tangeritin | Citrus reticulata | Prostate | PC3 | 48 | 17.2 µM | [63] |

| Gastric | AGS | 48 | <20% (33.57 µM) | [102] | ||

| BGC-823 | 48 | >90% (100 µM) | ||||

| SGC-7901 | ||||||

| 5,4'-dihydroxy-6,7,8-TMF/ xanthomicrol | Achillea erba-rotta subsp. moschata | Colon | HCT116 | 24 | 42% (15 µM) | [81] |

| Breast | MCF7 | 72 | > 100 µM | [49] | ||

| Cervical | Hela | 72 | > 100 µM | [83] | ||

| 6-MF | Pimelea decora | Cervical | Hela | 72 | 55.31 µM | [111,112] |

| C33A | 72 | 109.57 µM | ||||

| SiHa | 72 | 208.53 µM | ||||

| 5,3'-didemethylnobiletin | Citrus reticulata | Liver | HepG2 | 24 | 41.37 µM | [84] |

| 5,4'-didemethylnobiletin | 24 | 54.46 µM | ||||

| 5,3',4'-tridemethylnobiletin | 24 | 46.18 µM | ||||

| 5,7,3',4'-TeMF | Kaempferia parviflora | Colon | HCT116 | 72 | 75% (60 µM) | [80] |

| 7,8,3',4'-TeMF | Citrus reticulata | 72 | 90% (60 µM) | |||

| 5,4’-dihydroxy-3,6,7,8-TeMF/ calycopterin | D. kotschyi Boiss | Prostate | DU145 | 48 | 235 µM | [69] |

| LNCaP | 48 | 116.5 µM | ||||

| 5,4’-dihydroxy-6,7-DMF / cirsimaritin | Quercus incana | Lung | NCI-H460 | 24 | 26.23 µM | [115] |

| 5,3′-dihydroxy-6,7,4′-TMF / eupatorin | 24 | 37.50 µM | ||||

| 5,7-dihydroxy-6-MF / acacetin | Robinia pseudoacacia | Liver | HepG2 | 24 | 25 µM | [89] |

| 5,6,7,3',4'-PeMF / Sinensetin | O. aristatus leaves | HepG2 | 24 | 80% (50 µM) | [86] | |

| 5,7-dihydroxy-6-MF/ Oroxylin A | Scutellaria baicalensis | Breast | 4T1 | 24 | ~90% (40 µM) | [116] |

| 5,7,4’-trihydroxy-6-MF | Artemisia capillaris | Prostate | VCaP | 48 | NA | [67] |

| 5,4’-dihidroxy-3,6,7,3'-TeMF / chrysosplenetin | Artemisia annua L. | Breast | MCF | 72 | 0.3 µM | [48] |

| 5-hydroxy-6,7,8,4'-TeMF / 5-Demethyltangeritin | Citrus reticulata | Prostate | PC3 | 48 | 11.8 µM | [63] |

| 5,3’-dihydroxy-3,6,7,4’-TeMF / casticin | Dracocephalum kotschyi Boiss | Prostate | DU145 | 48 | >80% | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).