1. Introduction

1.1°. The overarching objective of optimal

structural design theory is to identify a structure that optimizes a specific

mechanical characteristic, while adhering to the prescribed constraints. In the

classical optimal design problem, there is a single decision-maker, or

"designer," who must consider the shapes, sizes, material properties,

and mutual positions of structural members. These parameters are referred to as

design parameters. Additionally, the conditions of exploitation and external

actions on the structure must be defined.

The scalar and vector problems are commonly studied

in structural optimization. The goal of scalar design optimization is to select

the values of the design variables, given various constraints, so that a single

objective function reaches an extreme value. A characteristic feature of such

multi-criteria optimization problems is the occurrence of objective conflict,

i.e. none of the feasible solutions allows the simultaneous minimization of all

objectives, or the individual solutions of each individual objective function

differ. Consequently, multiobjective optimization deals with all kinds of

conflicting problems, (Eschenauer, Koski, & J., 1990), Sect. 1.2. In the

current context, the scalar optimization formulation is represented by an

antagonistic game formulation. Analogously, the vector optimization formulation

corresponds to the bi-matrix game. Each of the two players has its own payoff

matrix. These concepts will be discussed in detail later.

1.2°. Game theory is a framework for understanding

situations of conflict and cooperation between rational decision makers. It

builds on the ideas of mainstream decision theory and economics, which say that

people act rationally when they choose actions that maximize their payoff,

given the constraints they face. The field of game theory is primarily

concerned with the logical foundations of decision-making processes in

situations where the outcome is contingent upon the actions of two or more

autonomous agents. A crucial aspect of such scenarios is that each

decision-maker possesses only partial control over the resulting outcomes. The

phrase "the theory of interdependent decision-making" more accurately

encapsulates the core tenets of the theory. Game theory pertains to situations

wherein the options at the disposal of each decision-maker and their potential

consequences are clearly delineated, and each decision-maker exhibits

consistent preferences regarding the prospective outcomes. The primary

objective of game theory is to identify solutions to games. Matrix games are

two-person games with the finite strategy sets and matrix-based pay-off

function zero. The coefficients of the pay-off matrix are the given, fixed

values. Matrix game is zero-sum game which means when strategies of row and

column player are fixed, the sum of pay-offs for the two players is zero. The

most important theorem in matrix game is the Neumann’s minimax theorem (von

Neumann, Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele., 1928). Neumann’s theorem was

proved using Brouwer’s fixed point theorem. Another proof from 1944 was based

on dual linear programming (von Neumann & Morgenstern, Theory of Games and

Economic Behavior, 2004). A solution is defined as a set of criteria that

delineates the decision to be made and the subsequent outcome that will be

reached if the decision-makers adhere to the established rationality criteria.

One potential approach to structural optimal design can be formulated as

follows: external actions are suboptimal in that they result in the greatest

stress intensity, maximal deflection, or highest level of fracture. In game

theory, the term "payoff function" is typically used in place of the

"aim function," which is the goal of the optimal design problem. Game

theory is concerned with analyzing conflict situations in which the

participants are conscious and rational beings trying to achieve a certain

goal. However, in many cases, one of the participants cannot be considered a

conscious individual with preferences and goals. Consequently, the other

players cannot assume that this participant will behave rationally.

1.3°. The application of game theory to the optimal

design is a long-standing field of study (Banichuk, On the game theory

approach to problems of optimization of elastic bodies, 1973), (Greiner, Periaux, Emperador, Galván, & Winter, 2017), (Holmberg, Thore, & Klarbring,

2017). It has been demonstrated (Kobelev, On a game approach to optimal

structural design., 1993) that the role of the payoff function in ensuring

integral compliance can be expressed in terms of the minimal eigenvalue of the

inverse operator of the system (continual case) or the response matrix

(discrete case). This is a fundamental characteristic of the game, and it is

therefore referred to as the upper game value. A game-theoretic approach to

robust topological optimization with uncertain loading is illustrated using

three different games for the design of both two-dimensional and three-dimensional

structures (Thore, Alm Grundström, & Klarbring, 2020), (Thore,

Holmberg, & Klarbring, 2017).

1.4°. For optimization purposes, the payoff matrix

is modified by the player “designer” acting according to the

"cardinal" strategy. The alteration is made in favor of the player

who receives the winnings. Once the "substratum" game has commenced,

it is no longer possible to modify the payout matrix. The degrees of freedom of

the "cardinal" players are known under the same names as those used

in classical structural optimization. The degrees of freedom of the

"cardinal" players are identified as "control functions" or

"design parameters." In the event that there is only one

"cardinal" player, no conflict of interests arises. In the event that

there are multiple "cardinal" players with disparate interests, a

situation of conflict may arise. The aforementioned conflict gives rise to the

"superstratum" game on the upper level. This scenario is typical in

the field of engineering. For example, the objective of the system designer is

to achieve the optimal performance of the system. The production designer seeks

to implement the system in the most effective and cost-efficient manner. The

operating ecology manager aims to ensure the lowest emission level during the

system's operational phase. The production ecology manager recognizes the

necessity of reducing emissions during the manufacturing stage. Ultimately, the

customer strives to minimize the system's overall cost and operational

expenses. However, these objectives are not always aligned, leading to

potential conflicts among the "cardinal players."

1.5°. The term "stratified game" can be

more easily defined by reference to the concept of matrix games. The typical

game formulations utilize a fixed game matrix. The objective of the game is to

identify the optimal strategies for the players given the predefined and

unchanging game matrix. In light of the aforementioned statements, the term

"stratified game" is defined as a game formulation with a

controllable value. In a stratified game, the elements of the matrix are

predefined functions of the design parameters. Accordingly, the value of the

game is a function of the design parameters. The value of the game is the

result of the lower-level (substratum) game task for each fixed set of design

parameters. The determination of the maximum value of the game value as a

function of the design parameters is the upper-level (superstratum) task. For

upper-level task the methods of optimization or control theories are applied.

The occurrence of these two levels leads to the term "stratified

game."

The mentioned line of reasoning can be applied to

diverse optimization problems that involve multiple levels of decision-making.

To illustrate, lawmakers can be considered the "superstratum" of a

social game. The actions of the superstratum players shape the governing

equations of the game, such as those related to taxation or ecological laws.

Meanwhile, the players in the "substratum" adhere to the legislation

that defines their objectives and the associated modus vivendi.

1.6°. There is a fundamental difference between the

concepts of game theory in social sciences and operations theory on the one

hand, and in engineering and natural sciences on the other. The difference lies

in the understanding of the resource limits of the game players.

The total resources in social sciences and

operations theory are the linear sum of the partial resources of each player.

For example, the bank account represents the total amount of money of the

player. Each operation is the linear addition of some amount of money. It is

possible to look at this function from the point of view of functional

analysis. In functional analysis and related areas of mathematics, a sequence

space is a vector space whose elements are infinite sequences of real or

complex numbers. norm is a norm on the space of -integrable functions (Werner, 2018). These are

special cases of spaces for the counting measure on the set of

natural numbers. The most important sequence spaces in analysis are the spaces, which consist of sequences summable to the

-th power, with the p-norm. -norm denotes the norm on the space of -summable sequences. Each element of the sequence

is the transaction to or from the account. That is, the actual state of the

account is the linear sum of sequences. The power in the sequences that arise in the usual game

theory of the social sciences is one. The summation of probabilities in the

decision-making theory is linear per definition as well. The corresponding game

theory with linearly summed resources is fully established in well-known works (von Neumann, Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele., 1928)(von Neumann & Morgenstern,

Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, 2004)(Tadelis, 2013) (Fernandez,

Monroy, & Puerto, 1988) and does not require revision or extension.

The application of game-theoretic methods to

problems of a physical nature presents a different situation. The total

resources in Engineering and Science are the quadratic sum of the partial

resources of each player. The Euclidean norm, standard norm, or 2-norm is a

vector norm commonly used in science and engineering. In two- and

three-dimensional Euclidean space, the Euclidean norm corresponds to the visual

length or magnitude of a vector and can be calculated using the Pythagorean

theorem. More generally, the Euclidean norm is also defined for real and

complex vector spaces of arbitrary finite dimension, and is then the norm

derived from the standard scalar product. For example, the total energy of

vibration, which is composed of a sequence of vibrational modes. From the

viewpoint of sequence space concept, each element of the sequence is energy of

a vibrational mode. The total energy is the quadratic sum of the partial

energies of each mode. That is, the total energetic resource is the quadratic

sum of sequences. The power in the sequences arising in the common game theory

for engineering and science is two. The possible applications of quadratic

sequences to the quadratic estimation of energy are numerous. The Poynting

vector represents the directional energy flux (the energy transfer per unit

area, per unit time) or power flux of an electromagnetic field. The intensity

of an electromagnetic wave is the average of the squares of the sinusoidal

functions for each mode. Quadratic summation of sequences is widely used in natural

sciences and is used to evaluate the energy of seismic waves, the energy of

wind and ocean currents, to calculate the elastic deformation energy of

external excitations. In light of the application of game theory in

engineering, it is necessary to revisit the concept of resource limitation,

which should be revised from a linear summation to a quadratic one.

1.7°. In summary, the tasks of the study and the

central ideas for their solution are the following:

The fundamental premise of this study is that the probability distribution governing nature's "choice" of states remains unknown. Statistical decision theory addresses decision-making scenarios where these probabilities, whether objective or subjective, are pertinent factors.

In classical structural optimization, the "cardinal" players are responsible for assuming the role of “design parameters” or "control functions". If the number of design freedoms is finite, one speaks about “design parameters”. For the continuous design freedom, the "control functions" are involved according to Pontryagin's maximum principle (Geering, 2007). In actual context, the "cardinal" players modify the governing equations and payoff functions in the game formulations (Eschenauer, Koski, & J., 1990). In structural optimization, the "cardinal" players are responsible for determining the coefficients of the governing equations. In essence, their function is to establish the rules of engagement, which may result in conflict between certain players. In the context of the stratified game approach, the "cardinal" players form the "superstratum", or the upper level of the game. The "cardinal payers" are designated as "designers" due to their capacity to alter, for instance, the coefficients of matrices in matrix games with the objective of attaining a superior value for the game.

Furthermore, other participants act in accordance with the governing equations, which are determined by the "cardinal" players. In the context of the stratified game approach, the "ordinal" players represent the "substratum." "Ordinal" players are permitted to make decisions within their respective stratum, but they are unable to impact the governing equations. The “ordinal” payers could be referred to as “nature” or “operators”. Certain "ordinal" participants represent the external forces. These external factors are typically referred to as "nature." For the sake of clarity, it may be more appropriate to refer to Nature's strategies as "states" rather than strategies. Such games are therefore classified as "games against nature." (Szép & Forgó, Games against nature., 1985) . The remaining "ordinal" participants aim to offset the impact of "nature" in order to mitigate potential risks or to achieve the most favorable outcome. (Kobelev, On a game approach to optimal structural design., 1993) For the sake of clarity, these participants will henceforth be referred to as "operators" and “nature”. In the case of antagonistic matrix game, the payout matrix is only relevant for “operators”. The role of “cardinal players” is inherited from the common optimization formulations.

The conflict between the two "ordinal" players, namely "nature" and "operators" is studied for the linearly summed resources using the common principles of game theory (Tadelis, 2013). This case is typical for interdependent decision making in operational research and social games.

The application of game formulations for problems of engineering and natural sciences assumes the quadratically summed resources of the ordinal players. The solution of matrix and bi-matrix games with the quadratically summed resources is essential for application of game-theoretical approach to the engineering and physical tasks.

1.8°. The following summarizes the results of the

current study:

In the matrix game, there is a single payoff matrix. From the perspective of optimization theory, there is a single objective function. In consequence, the optimization problem is of a scalar nature. This value represents the goal function of the matrix game. At the low-level (substratum level), the win of “nature” is the loss of the “operator” This game is antagonistic, with a single goal function. Theory of quadratically constrained matrix and bi-matrix games is presented in

Section 2 and

Section 3.

The solution of the stratified matrix game is presented in

Section 2. In a bi-matrix game, payoff matrices are employed. From the perspective of optimization theory, there are two distinct goal functions. The optimization problem is of vector type. These goal functions are derived from the solution of a bi-matrix game. The equilibrium between the interests of "nature" and "operator" results in a solution to the game at the lower level. The designer determines the optimal value for the goal function in accordance with the methods of vector optimization. The solution of the stratified bi-matrix game is presented in

Section 3.

In

Section 4 the results of the aforementioned sections are generalized for self-adjoint positive definite differential operators. The optimization of elastic energy was selected as an example of optimization task with closed form of solution. Action of “Nature” is the external load. The load that results in the greatest structural response among all permissible loads, represents the strategy of “nature” in low-level task. The upper value of the game could be determined in all cases. The third player, “designer” acts on the upper-level. “Designer” determines the optimal value for the aforementioned goal function, manipulating the “design variables”. Designer optimizes the upper value, creating the stiffer structural element for the most dangerous action of “nature”. The corresponding examples are given in Sections 4 to 7.

For special type of game with the stored energy, the value of the game is shown to be equal to the eigenvalue of structural matrix. The optimal strategies of the "operator" and "nature" are uniquely determined. In the simplest formulation, the resources of “operator” are limited to zero. In this case, there is no opposite reaction to all possible actions of “nature” on the lower level. In this case, the role of the opposite player takes the cardinal player, “designer”. The "designer" modifies the coefficients of the payoff matrix, while "nature" alters both the left and right vectors of the payoff function

The application of the aforementioned considerations to structural optimization problems will be discussed in the following sections. The

Section 5 and

Section 6 demonstrate the applications of the developed technique for the structural optimization problems with the continuous control functions. In

Section 5, the beam is subjected to arbitrary bending efforts, and the designer determines the optimal beam shape for resisting these forces. In

Section 6, the rod is subjected to arbitrary twist moments, and the designer determines the optimal design of the twisted bar, ensuring the greatest stiffness.

Section 7 presents a mathematical analysis of the solutions presented in

Section 5 and

Section 6, employing the tools of inequalities theory to elucidate the underlying mathematical principles of the PARETO and NASH fronts.

2. Antagonistic Matrix Stratified Games

2.1°. This section contains basic information from

the theory of finite antagonistic (matrix) games. The existence theorem of the

equilibrium situation in the class of mixed strategies, the properties of

optimal mixed strategies, and methods for solving matrix games are

well-established areas of research.

The study of game theory commences with the most

basic static model: a matrix game in which two players engage, the set of

strategies available to each player is finite, and the gain of one player is

equal to the loss of the other. System

where and are nonempty sets and the function , is called an antagonistic stratified game in

normal form. The elements and are called the strategies of ordinal players 1 and

2 respectively in the game , the elements of the Cartesian product (i.e., the pair of strategies where and ) are situations, and the function is the win function of player 1. The payoff of

player 2 in situation is assumed to be equal to ; therefore, the function is also is called the win function of the game itself, and the game is called a zero-sum game.

Thus, using the accepted terminology, to define a

game it is necessary to define the sets of strategies of the ordinal players 1 and 2, and also the

winning function , defined on the set of all situations .

The stratified game is interpreted as follows. Ordinal players

simultaneously and independently choose strategies . In the substratum game, the ordinal player 1

then receives a payoff equal to , and ordinal player 2 receives The elements are called the strategies of cardinal players in

the stratified game .

In a stratified game, the elements are referred to as the strategies of cardinal

players. The superstratum game pertains to the strategies for cardinal players that ensure the maximal and minimal values of the

substratum payoff function. When there is only one cardinal player, the

superstratum game reduces to the optimization problem. In contrast, when there

are two or more cardinal players, their interests may be in opposition,

resulting in what is known as an antagonistic game. The total payoff for both

ordinal players on the lower level is zero. The goal function on the upper

level is the payoff of an ordinal player, e.g. the "operator". This

objective function is modified by the "designer" at the upper level.

2.2°. The following definition is proposed:

Antagonistic games in which both ordinal players possess finite strategy sets

are designated as substratum matrix games.

In the matrix game, ordinal player 1 is assumed to

have only strategies. The set of strategies available to the

first ordinal player, , must be ordered, that is, a one-to-one

correspondence must be established between and . The same process must be repeated for the second

ordinal player, with and . The sets and are then ordered in a one-to-one correspondence

with . and , respectively, where and are finite sets of cardinalities and , respectively.

The substratum matrix game

is thus completely defined by the matrix

, where

is defined as follows:

This is the rationale behind the name of the game,

which is derived from the aforementioned matrix. In this instance, the game is realized as follows: Player 1 selects a row, , and player 2 (simultaneously with player 1 and

independently of him) chooses a column,. Ordinal player 1 then receives a payoff, , and ordinal player 2 receives. In the event that the payoff is a negative

number, it constitutes an actual loss for the ordinal player.

We denote the substratum game with win matrix by and refer to it as an game, in accordance with the dimensions of the

matrix with the fixed values of strategies for

cardinal players .

2.3°. The question of optimal behavior of players

in an antagonistic game is worthy of consideration. It is reasonable to

conclude that a situation in the game is optimal if deviating from it is not favorable for any of the players. Such a situation is referred to as an equilibrium, and the optimality principle based on the construction of an equilibrium situation is known as the equilibrium principle.

For an equilibrium situation to exist in the substratum game

, it is necessary and sufficient that there exist a minimax and a maximin:

and the equality is satisfied:

The Eq. (03b) establishes a connection between the equilibrium principle and the minimax and maximin principles in an antagonistic game. Games in which equilibrium situations exist are called well-defined games. Therefore, this theorem establishes a criterion for a well-defined game and can be reformulated as follows. For a game to be well defined, it is necessary and sufficient that there exist and in Eq. (03) and the equality in minimax is satisfied.

If there exists an equilibrium situation, then the minimax is equal to the maximin, and according to the definition of the equilibrium situation, each player can communicate his optimal (maximin) strategy to the opponent and neither player can get an additional benefit from it.

2.4°. Now suppose that there is no equilibrium situation in the substratum game

. Since a random variable is characterized by its distribution, we will further identify a mixed strategy on the set of pure strategies of ordinal players. Thus, the mixed strategy

of ordinal player 1 in the substratum game is an

-dimensional vector, which is constrained by the following equation:

where the

norm in the real vector space

is defined as:

Similarly, the mixed strategy y of player 2 is an

-dimensional vector:

The positive natural number determines the class of the game. It should be noted that the numbers and are not required to be equal in all cases.

2.5°. If

, the values

and

are the probabilities of choosing pure strategies

and

, respectively, when ordinal players use mixed strategies

and

. Let us denote by

and

the sets of mixed strategies of the first and second players, respectively. It is easy to see that the set of mixed strategies of each player is a compact in the corresponding finite-dimensional Euclidean space (a closed, bounded set). A mixed set represents an extension of the pure strategy space available to the player. An arbitrary matrix game is well defined within the class of mixed random strategies. The von Neumann theorem of matrix games states, that

in the case every matrix game has an equilibrium situation within the context of mixed strategies (Tadelis, 2013). The cited literature provides an overview of the methods used to evaluate the game values. The setting

is typical for the application of game theory fields of economics, political science, and the social sciences. This setting reflects the fact that the mixed strategy for ordinal players is simply a probability distribution over their pure strategies. The probability of any event must be positive, and the total probability of all events must be one. Consequently, any mixed strategy must adhere to the following conditions:

2.6°. If

, the values

and

are the Euclidian coordinates of vector strategies

,

of the ordinal players. The Euclidean length of a vector

in the real vector spaces

and

are given by their Euclidean norms:

As illustrated in the aforementioned examples, this scenario is typical in the game formulations of engineering and physical applications. In such applications, the module of actions for the ordinal players are restricted. The modules of strategy vectors are less or equal than one:

With the definitions (04) and /25), the pay-off function of the matrix game on the lower substratum level reads:

The Lagrangian combines the pay-off function (09) with the constraints (08), taken with the non-negative multipliers

:

For the pay-off function (09) with the conditions (08), the equilibrium state

satisfies the equations:

The resolution of the Eq. (11) reads:

The left sides of Eqs. (12) contain two auxiliary matrices:

The matrix

is

square Hermitian matrix. The matrix

is

square Hermitian matrix. If follows from Theorem 2.8, Sect. 2.4, (Zhang, 2011), that both matrices

and

have the same nonzero eigenvalues, counting multiplicity. The matrices

and

are positive-semidefinite (Theorem 7.3, Sect. 7.1, (Zhang, 2011)). The number of zero eigenvalues of

and

is at least

. Let

is the matrix with the smallest dimensions of

and

. In other words,

Generally saying, the matrix

is positive-semidefinite. The eigenvalues of the matrix

are:

If , then the matrices are equal = and have the same set of eigenvalues.

If

is positive definite, the number of its zero eigenvalues is exactly

. The eigenvalues of the positive definite matrix

are:

From Eq. (12) follows, that

. Finally,

Consequently, every matrix quadratic game has the equilibrium situations within the context of mixed strategies. In the case of , each equilibrium situation possesses one of the game values (14).

2.7°. In this section, the solution (14) to the substratum matrix game with constrained actions (Eqs. (04), (06), (08)) is identified. The objective of the superstratum task is to determine the optimal solution for the "designer" by searching for the extremal value of (14) through manipulation of the design variables.

3. Bi-Matrix Stratified Games

3.1°. In game theory, a bi-matrix game is defined as a simultaneous game for two players, each of whom has a finite set of possible actions. Such a game can be represented by two matrices: matrix

, which outlines the payoffs for ordinal player 1, and matrix

, which outlines the payoffs for ordinal player 2. The substratum bi-matrix game deals with two

matrices

and

, which elements depend parametrically upon the design vector

of cardinal players. For the fixed values of strategies for cardinal players

, the win of the first and second ordinal player are correspondingly:

The mixed strategies of both ordinal players in the substratum level of game are vectors, which are constrained by the following equations:

3.2°. Well known, that for the bi-matrix game has an equilibrium in randomized strategies (Lemke & Howson, 1964), (Szép & Forgó, Bimatrix games, 1985), (Denardo, 2011) Thus, the linear case does not require further investigation.

3.3°. In the vector case

, the substratum bi-matrix game has an equilibrium solution, which reduces to the generalized eigenvalue problem (Parlett, 1998). We study the following bi-matrix game:

According to the generalized Rayleigh-Ritz quotient method (Wilkinson, 1965), this optimization problem can be restated as:

The Lagrangian for (17) reads:

where

,

are the Lagrange multipliers. Equating the derivatives of

to zero gives:

The resolution of the Eq. (20) reads:

The symmetric semi-positive matrices in (21) are the following:

For briefness, the auxiliary matrix

will be defined. This matrix represents the matrix with the smallest dimensions of

and

. In other words,

The

are the eigenvectors and the

are the non-zero eigenvalues of the symmetric semi-positive matrix

:

The eigenvalues depend parametrically upon the strategies for cardinal players

and the parameter

of Eq. (20):

The eigenvectors

are the functions of these parameters as well. The parameter

plays the role of Lagrange multiplier. It parametrizes the front of the bi-matrix game. If the second player fixes its payoff in Eq. (17) to

, the value of the Lagrange multiplier

follows from this constraint. If Eq. (17) displays a maximization problem, the eigenvector is the one with the largest eigenvalue of the matrix

:

.

Alternatively, if Eq. (17) is a minimization problem, the eigenvector is the one with the smallest eigenvalue

The payoff of the first player satisfies the inequalities:

This solves the substratum bi-matrix game problem for the ordinal players on the lower, substratum level in the vector case .

Based on the substratum game value, the superstratum problem optimizes the eigenvalue in accordance with the goals of the cardinal players:

If there is only one cardinal player, namely a "designer", finding the extremum in the above equation is a common optimization task. In the actual context, there is only one cardinal player involved, which reduces the extremum search to a common task of mathematical programming.

In general, finding the extremum in the above equation can be a game optimization task, depending on the number of cardinal players involved. If there is no conflict between these players, finding the extremum is a standard optimization. Studying this is beyond the scope of the current manuscript.

3.4°. This section presents the solution (24) to the substratum bi-matrix game with constrained actions (Eqs. 16). The objective of the superstratum task is to identify the optimal solution for the "designer" by searching for the extremal value of (24) through variation of the design variables.

4. Optimization Games with one “Cardinal Player”

4.1°. In the most basic formulation, the resources available to the "operator" are limited to zero. In this case, there is no opposite reaction to all possible actions of "nature" on the lower level. In this case, the role of the opposite player is assumed by the cardinal player, "designer." The "designer" modifies the coefficients of the payoff matrix, while "nature" alters both the left and right vectors of the payoff function. In this formulation, it is possible to solve the game problem in the case of the continuous system. The results of the

Section 3 can be generalized for self-adjoint positive definite differential operators using the technique of control theory (Geering, 2007).

The mechanical system described by the equilibrium equations is to be considered in the following form:

The self-adjoint positive definite operator describes the state of the system. In Eq. (25), is the scalar function of state variables and is the scalar function of the external loads of player “nature”. All values are determined in some domain . In one-dimensional case, the domain could be thought as an open interval.

In structural optimization, there are definite “ordinal players”. These players can change the strategy in course of the game playing, such that these players will be referenced as the “ordinal players”. In the simplest case, there is one “ordinal player”. The vector of “nature” loads should belong to a set of admissible external loads:

Besides the “ordinal players”, there is another player. This player will be referenced as “cardinal player”. The “cardinal player” owns the constructional “design variables”. The differential operator

. depends upon the shape of two- or three-dimensional structural element. For example, the function

describes the mechanical properties along the length of the element. This is the unknown scalar or vector function. Thus, the coefficients of operator depend on

:

As usual, the certain isoperimetric conditions restrict the possible designs. For example, the total volume of the element could be restricted:

The pay-off functional is the functional of design and loads of both players:

This functional characterizes the essential mechanical characteristic of the structure, for example, compliance, period of vibration, maximal stress, etc. Putting it roughly, the natural aim of the “pilot” and “designer” is to minimize the functional for all possible actions of “nature”.

The upper and lower game values are defined as follows:

The minimax theorem states that, in general,

If the upper value of the game is equal to the lower value, the common value of minimaxes

and

is called the value of the game:

In this manuscript, the pay-off functional will be the stored elastic energy of the structural element (Reddy, 2002). This functional has the physical meaning of integral compliance). Thus, the game with the pay-off functional (29)

In Eq. (33) the symbol

stays for the bilinear form, or scalar product, satisfying:

The solution to equation (25) may be expressed in the following form:

For the purposes of this analysis, the restriction (26) will be assumed in quadratic form:

In Eq. (35), the operator

is the symbolical inverse of the

operator.

4.2°. Following the substitution of (35) into Eq. (33), the bi-linear payoff functional is expressed as follows:

The objective is to reduce the stored energy (38), given the restricted resources (36).

The expression

stays for the average elastic energy, which cause the stochastic actions of “nature” under the stochastic compensating action of “operator”. The determination of the minimal value of the game

is reduced to an ordinary optimization problem with the unknown design function

. The optimization game with the stored elastic energy as the payoff function could be referred to as a "compliance game."

Using the variational property of eigenvalues (Courant & Hilbert, 2004), one can obtain the equivalent expression:

In Eq. (39a),

is the minimal eigenvalue of the operator

:

is the maximal eigenvalue of the operator

:

The formulas (40a) and (40b) manifest in the sense of strategies of „nature“

. For the symmetric game both strategies match. The strategy of both concurrent players is given by the eigenvector of operator

, which corresponds to its eigenvalue

:

In other words, this is the load that results in the greatest structural response among all permissible loads, satisfying condition (36). Consequently, at least the upper value of the game could be determined in all cases. The application of the aforementioned considerations to structural optimization problems will be discussed in the following sections.

5. Game Formulation for the Beam Subjected to Arbitrary Bending Moments

5.1°. In the classical game theory, the games played over the unit square are considered as a generalization of matrix games. The pay-off function in "game played over the unit square" is thus defined on the unit square (Szép & Forgó, Games played over the unit square, 1985). In this case, a single continuous variable was retained for each individual due to the limitations imposed on the strategies of each player:

A comparable interpretation will be made from the perspective of game theory with regard to the optimization tasks involving an infinite number of design parameters for each player. Instead of vectors , ascend the functions . In lieu of the pay-off function, the pay-off functional emerges.

5.2°. Consider the beam of a certain cross-section. The beam, or rod is placed horizontally along x axis. The beam is subjected to an external load

distributed perpendicularly to a longitudinal axis of the element. The applied transverse load

is

a priori unknown. When a transverse load is applied on it, the beam deforms and stresses develop inside it. According to the Euler–Bernoulli theory of slender beams, the equation describing beam deflection can be presented as (Kobelev, Optimization of Compressed Rods with Sturm Boundary Conditions, 2023):

is the Young's modulus,

is the area moment of inertia of the cross-section,

is the internal bending moment in the beam. The quantity

in the above equation stays for the bending stiffness of the beam. The bending moment

is two times continuously differentiable function on

The area moment of inertia of the cross-section is given by the relation:

where

is the shape exponent,

is the shape factor. The shape factor depends on the cross-sectional shape. The admissible cross-sectional area of the rod is the scalar function:

The function is two times continuously differentiable. The cross-sectional area

plays the role of the strategy of “designer”. The shape exponent

takes the values of 1, 2 and 3 (Banichuk, Introduction to Optimization of Structures, 1990). In all these cases the game will be convex and both players have the pure strategies. The case

corresponds to a similar variation of the form of the cross-section. The areas, area moment of inertia and shape factors for the similar variation of the form of the cross-section

are shown in

Table 1. These formulas are valid for both a horizontal and a vertical axis through the centroid, and therefore are also valid for an axis with arbitrary direction that passes through the origin of the regular cross-sections. The

a priori unknown cross-sectional area

is the variable function along the span of the beam.

For brevity, the authors use for integral of an arbitrary function

the symbolization:

The boundary conditions must be prescribed as well. For the easiness, the rod is hinged at the end

and clamped at the end

. The boundary conditions are (Biezeno & Grammel, 1956):

5.3°. The pay-off functional

is the integral distortion of the structural element. Reasonably is to express the integral distortion as the double stored elastic energy

:

The game problem is defined exactly as already presented for the general

status quo. There are two active ordinal players, “nature” and “operator”, who behave recurrently and stochastically. The player (“nature”) can apply an arbitrary admissible external load

in order to affect the maximal elastic energy

. Due to the symmetry of game, the “operator” applies the opposite moments

, which compensate the deformation caused by “nature”. The total efforts of the “nature” and “operator” are restricted:

Admissible is any effort of “nature” and “operator”, which is a continuously differentiable function, satisfies (43) and certain boundary conditions. Because the quadratic norm (43) is restricted, the sign of the moment plays statistically no role. The game will be symmetric in sense of Nash (Nash, 1951)

The third player, (“designer “) attempts to select the most appropriate shape , which will guarantee the smallest deformation energy during the exploitation of the structural element. Once completed, the design remains unaltered over the period of exploitation. That’s why the “designer” is considered as the “passive” player, contrarily to the both other players, “nature” and “operator”.

The stiffest design corresponds to the minimal integral measure of deformation, which is presented by the stored energy

. The “designer” attempts to withstand the deformation are also limited. Namely, material volumes of all competing designs of the rods lesser than the certain, fixed volume of material

:

The conflict leads to the antagonistic game formulation of the optimization task. This game is referred to as the functional game, because the values of the game depend on the function

.According (4.23), the optimal value of game in mixed strategies is equal to:

The symbol

in (45) signifies the minimal eigenvalue of the game of the ordinary differential equation:

with the boundary conditions:

The optimization game with the minimal eigenvalue as the pay-off function could be referred to as “eigenvalue game”. From (45) and (46) follows, that the maximization of the upper value of the game reduces to the maximization of the minimal eigenvalue:

The cross-section for the Nash equilibrium state will be designated with the capital letter

, leaving the small letter

for any admissible cross-section function. The optimal cross-section presents the strategy for the active players. In other words, the beam with the thickness distribution

possesses the guaranteed stiffness:

The eigenvalue problem (46a), (46b) is self-adjoint. The conditions (46b) are of the Sturm type; see (Zettl, 2005). There exists an infinite set of eigenvalues, all eigenvalues are real and positive and can be arranged as a monotonic sequence, and each eigenvalue is simple:

The Rayleigh's quotient is:

In Eq. (50a), the admissible functions are all functions, having piecewise continuous first derivatives, satisfying the boundary conditions (46b). In the Rayleigh's quotient stays the admissible moment of both active players: .

Among all admissible strategies of „nature”, the most favorable strategy set for “nature” is

. This choice delivers the minimal value for the Rayleigh's quotient:

The favorable strategy set which minimizes Rayleigh's quotient, increases according to (45) the energy of deformation from (42b) under its condition (43).

The “designer” has the opposite task. The necessity of “designer” is to minimize the energy of deformation for all admissible

under his condition (44). This task is equivalent to the maximization of the Rayleigh's quotient with the restriction (43) (Lewis & Overton, 1996), (Henrot, 2006). The Lagrangian functional is the sum of (50b) and (44):

Here

represents the Lagrange multiplier of the variational calculus problem. The variation of the Hamiltonian functional reads:

The nullification of the derivative

leads to the necessary optimality condition. The strategies in the state of Hash equilibrium are

,

, and consequently:

From the viewpoint of the „designer”, the thickness distribution must satisfy the necessary optimality condition (51).

From the Noether’s viewpoint, the Hamiltonian functional is the Noether’s. The stationarity of Noether’s charge expresses the equilibrium of the opposite interests of both players. The condition (51) symbolizes the Noether’s current, which should be constant along the span of the structural element in the equilibrium situation of game. From the viewpoint of “designer”, the beam with the thickness distribution guarantees the highest effectiveness for the most unfavorable effort of the opposite player (“operator”).

5.4°. The next task is to determine the Nash equilibrium strategies for the “designer”

and for the „nature“

. For briefness of formulas, we put temporarily

. The governing equation is the nonlinear ordinary differential equations of the second order:

In each of Eqs. (52) to (62),

signifies the minimal eigenvalue (49) in the Nash equilibrium point:

The boundary conditions (41) could be proved to be optimal for boundary conditions of the Sturm type. The equilibrium conditions of the game task are equivalent to the necessary optimality condition for a column’s Euler buckling load (Cox & Overton, 1992). The substitution of Eq. (51) into (52) gives:

The solution of the boundary value problem (41), (53) determines the strategy of „nature“

. With this solution, highest possible eigenvalue (52) and, consequently, the upper value of the game have to be evaluated:

The dependent variable

and independent variable

of the equation (53) are to be exchanged. In the new variables

, the Eq. (53) turns into the Emden-Fowler equation:

The Emden-Fowler equation (54) has the following parameters:

The closed-form solution outcomes for an arbitrary acceptable value of the shape exponent

. The general solution of Eq. (54) for

is:

The symbols and stay for the integration constants. The integration constants are to evaluated from the solution of the nonlinear transcendental equations. To avoid the solutions of the nonlinear equations, the authors prefer the symmetry sights. Specifically, the sense of the constant is the moment on the end :

.

Due to the symmetry the equations with respect to the point

, the function

must be an even function of the variable

. This condition fixes the relation between integration constants:

With this value, the integral (56) evaluates in the closed form. For the shape exponent

and

, the solution reads with Eq. (A.15) as:

,

,

The Eq. (57a) presents the axial coordinate

as the function of the new independent parameter

. For

the hypergeometric function from Eq. (57b) expresses in terms of elementary functions

(Table 2). The solution is bulky and is omitted for briefness. According the boundary conditions (41), the dimensionless moment

vanishes on the hinged end:

. From this condition, the length of the rod could be determined as the function of an unknown integration constant

. Because the length

of the rod is known, the unknown constant

evaluates from the solution of the equation:

From its solution, the integration constant

follows as:

Table 2.

Expressions for axial coordinate as the function of for and .

Table 2.

Expressions for axial coordinate as the function of for and .

|

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

In its turn, the integral of the cross-area results from Eq. (A.15) and

To find the volume of the element, the authors evaluate the proper integral of the cross-section area

For all values of

, higher that one, the volume of the optimal structural element will be:

The authors define one another constant that was referred above as a total stiffness

of the structural element. The total stiffness

of the beam expresses as an integral of the moment of inertia of the cross-sections along the length

of the beam. To find the total stiffness of element in the Nash equilibrium state, the authors evaluate another proper integral. From Eq. (A.15), follows the integral of the energy density

as:

According to Eq. (60), the elastic energy density is constant over the length of the structural element.

Finally, the eigenvalue

equals in the Nash equilibrium point to:

The Eq. (59). (60), (61) characterize the principal mechanical properties in the Nash equilibrium state.

Table 3.

Stored elastic energy and volume for Nash equilibrium

Table 3.

Stored elastic energy and volume for Nash equilibrium

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

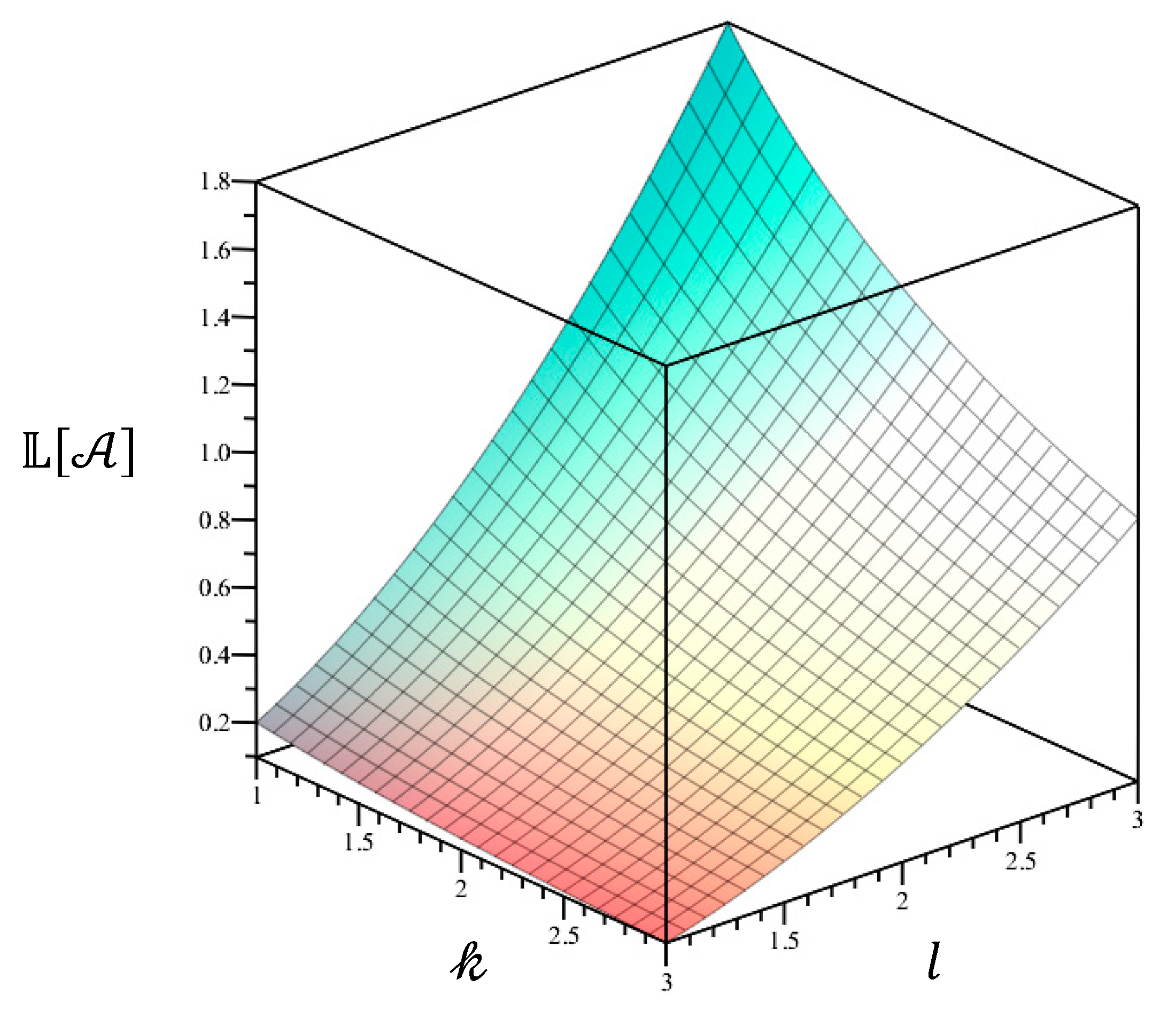

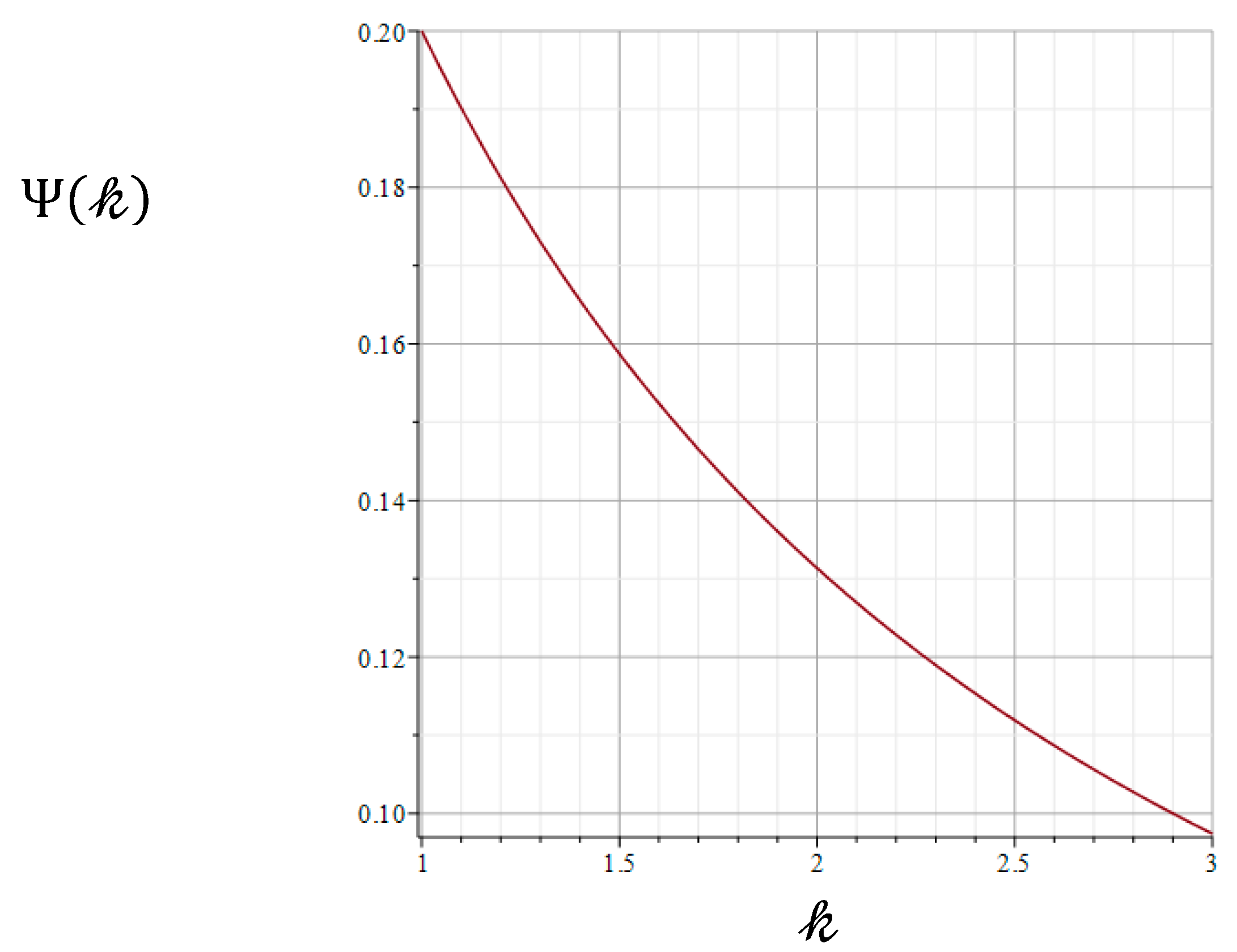

For the state of Nash equilibrium, the eigenvalue depends on the known constants:

is the dimensionless function (

Figure 1):

5.5°. Our next task is to establish the relation between the eigenvalues

and

. In the convex case

, the relation could be rigorously proved as the certain isoperimetric inequality. For this purpose, the lowest eigenvalues for two different thickness functions

and

are the minimal values of the two corresponding Rayleigh's quotients:

The Rayleigh's quotients are the functionals of functions

and

or

correspondingly. The functions

or

are assumed in this section to be fixed. The function

is an arbitrary admissible function, which is differentiable and satisfies boundary conditions (41). The critical points of a functional is that point where the functional attains a minimum (or maximum) in the presence of constraints (Kesavan, 2022). We therefore examine conditions when a functional attains a minimum. For the thickness function

the critical point of the Rayleigh's quotient

is the eigenfunction

. To the eigenfunction

corresponds the lowest eigenvalue

. The guarantees, that:

Analogously, for the thickness function

the critical point of the Rayleigh's quotient

is the eigenfunction

. To this function corresponds the lowest eigenvalue

:

The right sides of the equations (63a) and (63b) must be compared. In order to state the desired isoperimetric inequality, the following auxiliary inequality have to be approved:

The numerators of the fractions to the left and right of the auxiliary inequality (64a) are identical. The denominators (64a) are, however, different. Thus, the denominators should be compared. The inequality for denominators, that has to be proven, reads:

At this point, the optimality condition (51) with

will be used:

Namely, the substitution of the optimality condition (51) into (64b) delivers the inequality for

:

The equality in (65) takes place only for . The validity of the yet suspected inequality (65) follows directly from the Hölder inequality (A.13). Consequently, from (A.11) and (A.13) follows the inequality for denominators (65) and finally the desired inequality (63).

Combining (63) and (65) delivers:

Consequently, it was proved that for all arbitrary

the eigenvalue is less than

:

The equality in Eq. (66) attained only for the optimal beam, which has the optimal shape and the maximal possible volume of material . For shape exponent , the game is convex. Generally, the game will be convex for any convex function .

Finally, the beam, that obeys the necessary optimality conditions (51), delivers the lowest possible upper value of the game:

Consequently, the value of functional game

for the optimal distribution of thickness

is lower than the pay-off functional (distortion energy) for an arbitrary distribution of thickness

of the same volume:

If the volume of an arbitrary thickness distribution is lower, follows the stronger inequality:

The relations (67a), (67b) and (67c) solve the “superstratum” game with the undefined, but constrained (43) bending moment function. From the viewpoint of “designer”, the optimal distribution of thickness guarantees the best compromise for the most unfavorable for the “designer” action of “nature”. This compromise is the equilibrium in the functional game.

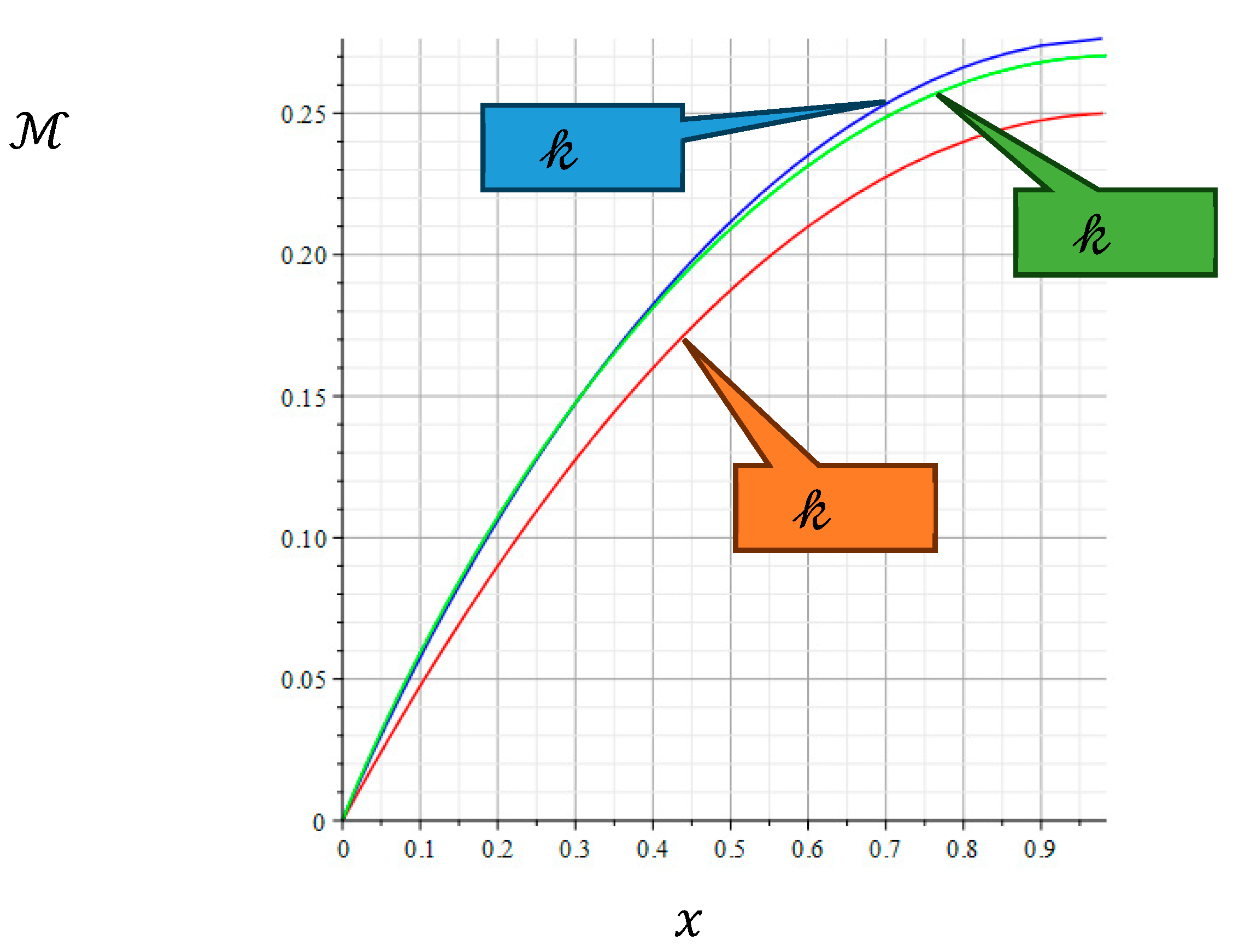

Figure 3.

as function of length and shape factor

Figure 3.

as function of length and shape factor

5.6°. In

Section 5, the beam is subjected to arbitrary bending efforts, and the designer determines the optimal beam shape for resisting these forces

6. Game Formulation for the Rod Subjected to Arbitrary Torque

6.1°. Consider the rod with the circular cross section, subjected to the positive distributed torque along its axis. The torque distribution is arbitrary, but the quadratic integral of the torque is fixed:

The governing equation for this problem is similar to Eq. (45), but the order is twice lower (Kobelev, Stability Optimization of Twisted Rods, 2023). In this case, the symbol

in (45) signifies the minimal eigenvalue of the game of the ordinary differential equation:

with the boundary conditions:

The optimal cross-section will be designated with the capital letter

, leaving the small letter

for any admissible cross-section function. The optimal cross-section presents the strategy for the “nature”. In other words, the rod with the thickness distribution

possesses the guaranteed stiffness:

The eigenvalue problem (68a), (68b) is self-adjoint. The conditions (68b) are again of the Sturm type. Once again, there is an infinite set of simple eigenvalues, all eigenvalues are real and positive and can be arranged as a monotonic sequence:

The Rayleigh's quotient is:

In Eq. (70a), the admissible functions are all functions, having piecewise continuous first derivatives, satisfying the boundary conditions (68b). In the Rayleigh's quotient stays the admissible twist of “nature”: .

6.2°. Among all admissible strategies of “nature”, the most favorable strategy set for “nature” is

. This choice delivers the minimal value for the Rayleigh's quotient:

The favorable strategy set which minimizes Rayleigh's quotient, increases according to (65) the energy of deformation from (62b) under its condition (63).

The “designer” has the opposite task. The necessity of “designer” is to minimize the energy of deformation for all admissible

under his condition (64). This task is equivalent to the maximization of the Rayleigh's quotient with the restriction (63). The Lagrangian functional is the sum of (70b) and (64):

Here

represents the Lagrange multiplier of the variational calculus problem. The variation of the Lagrangian functional reads:

The nullification of the derivative

leads to the necessary optimality condition. The strategies in the state of Hash equilibrium are

,

, and consequently:

From the viewpoint of the “designer”, the thickness distribution must satisfy the necessary optimality condition (71). Remarkably, that the equilibrium conditions of the game task are equivalent to the necessary optimality condition for the twist divergence of a wing (McIntosh, Weisshaar, & Ashley, 1969), (Battoo, 1999).

6.3°. The next task is to determine the Nash equilibrium strategies for the “designer”

and for the „nature“

. For briefness of formulas, we put temporarily

. The governing equation is the nonlinear ordinary differential equations of the second order:

In each of Eqs. (72) to (82),

signifies the minimal eigenvalue (69) in the Nash equilibrium point:

The substitution of Eq. (71) into (72) gives:

The solution of the boundary value problem (68), (73) determines the strategy of „nature“

. The dependent and independent variables of the equation (73) are to be exchanged. In the new variables, the Eq. (73) turns into the Emden-Fowler equation:

The Emden-Fowler equation (74) has the following parameters:

The closed-form solution outcomes for an arbitrary value of the shape exponent

. The solution of (76) reads with Eq. (A.15) as:

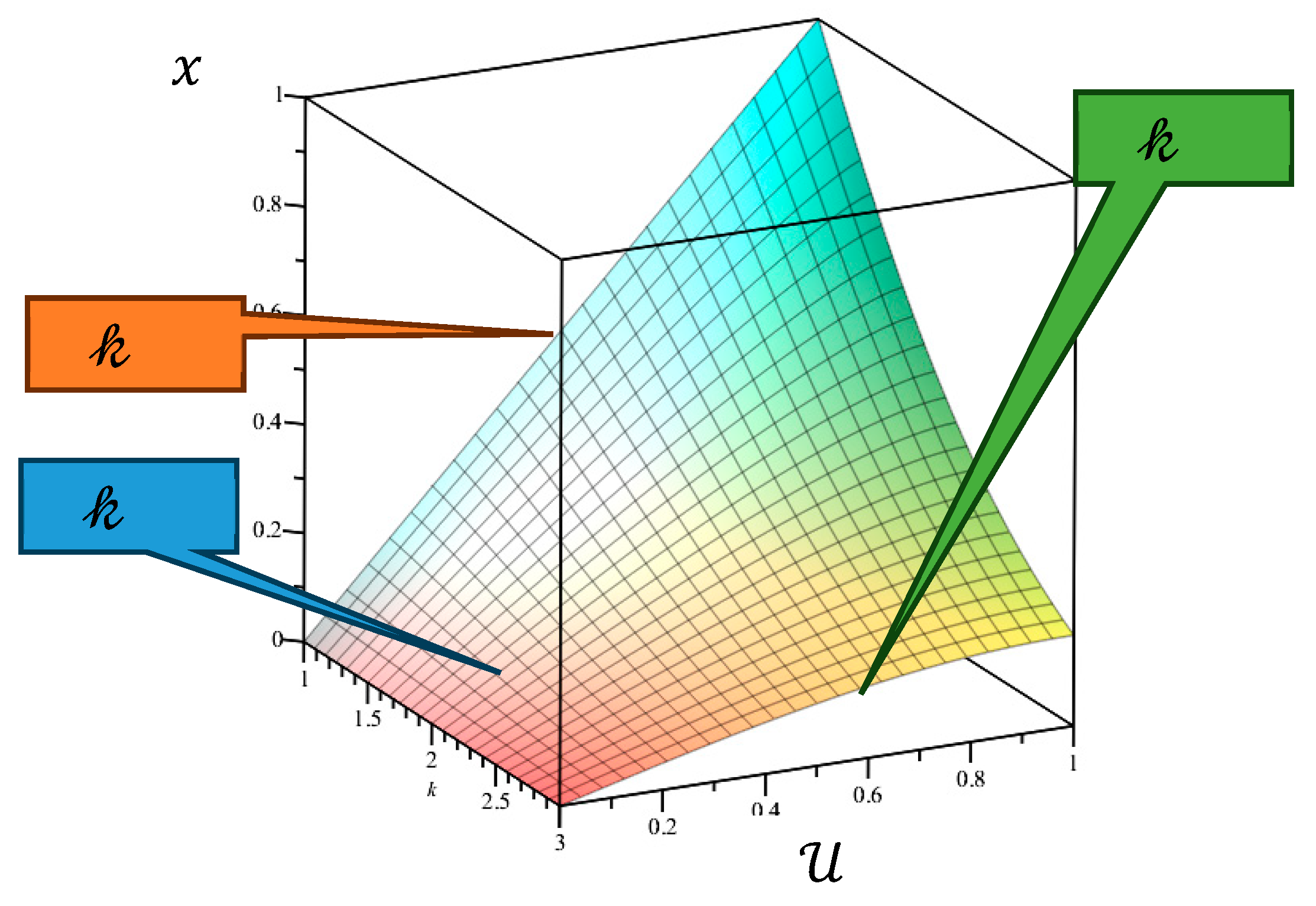

Figure 4.

Optimal shapes of twisted rods for the Nash equilibrium states.

Figure 4.

Optimal shapes of twisted rods for the Nash equilibrium states.

The Eq. (77) presents the axial coordinate as the function of the independent parameter . For the hypergeometric function from Eq. (77) expresses in terms of elementary functions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Expressions for axial coordinate as the function of for ,

Table 4.

Expressions for axial coordinate as the function of for ,

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

1 |

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

6.4°. The next task is to establish the relation between the eigenvalues

and

. In the convex case

, the relation could be rigorously proved as the certain isoperimetric inequality. For this purpose, the lowest eigenvalues for two different thickness functions

and

are the minimal values of the two corresponding Rayleigh's quotients:

The Rayleigh's quotients are the functionals of functions

and

or

correspondingly. The functions

or

are assumed in this section to be fixed. The function

is an arbitrary admissible function, which is differentiable and satisfies boundary conditions (61). The critical points of a functional is that point where the functional attains a minimum (or maximum) in the presence of constraints. We therefore examine conditions when a functional attains a minimum. For the thickness function

the critical point of the Rayleigh's quotient

is the eigenfunction

. To the eigenfunction

corresponds the lowest eigenvalue

. The guarantees, that:

Analogously, for the thickness function

the critical point of the Rayleigh's quotient

is the eigenfunction

. To this function corresponds the lowest eigenvalue

:

The right sides of the equations (83a) and (83b) must be compared. In order to state the desired isoperimetric inequality, the following auxiliary inequality have to be approved:

The denominators of the fractions to the left and right of the auxiliary inequality (84a) are identical. The nominators (84a) are, however, different. Thus, the nominators should be compared. The inequality for nominators, that has to be proven, reads:

At this point, the optimality condition (71) with

will be used:

Namely, the substitution of the optimality condition (71) into (84b) delivers the inequality for

:

The equality in (85) takes place only for . The validity of the yet suspected inequality (85) follows directly from the Hölder inequality (A.14). Consequently, from (A.11) and (A.14) follows the inequality for nominators (85) and finally the desired inequality (83).

Combining (83) and (85) delivers:

Consequently, it was proved that for all arbitrary

the eigenvalue is less than

:

The equality in Eq. (86) attained only for the optimal beam, which has the optimal shape and the maximal possible volume of material . For shape exponent , the game is convex. Generally, the game will be convex for any convex function .

The rod, that obeys the necessary optimality conditions (71), delivers the lowest possible upper value of the game:

Consequently, the value of functional game

for the optimal distribution of thickness

is lower than the pay-off functional (distortion energy) for an arbitrary distribution of thickness

of the same volume:

If the volume of an arbitrary thickness distribution is lower, follows the stronger inequality:

The relations (87), (88) and (89) solve the “superstratum” game for the twisted beam with the undefined torque distribution.

6.5°. In

Section 6, the rod is subjected to arbitrary twist moments, and the designer determines the optimal design of the twisted bar, ensuring the greatest stiffness.

7. Nash and Pareto fronts

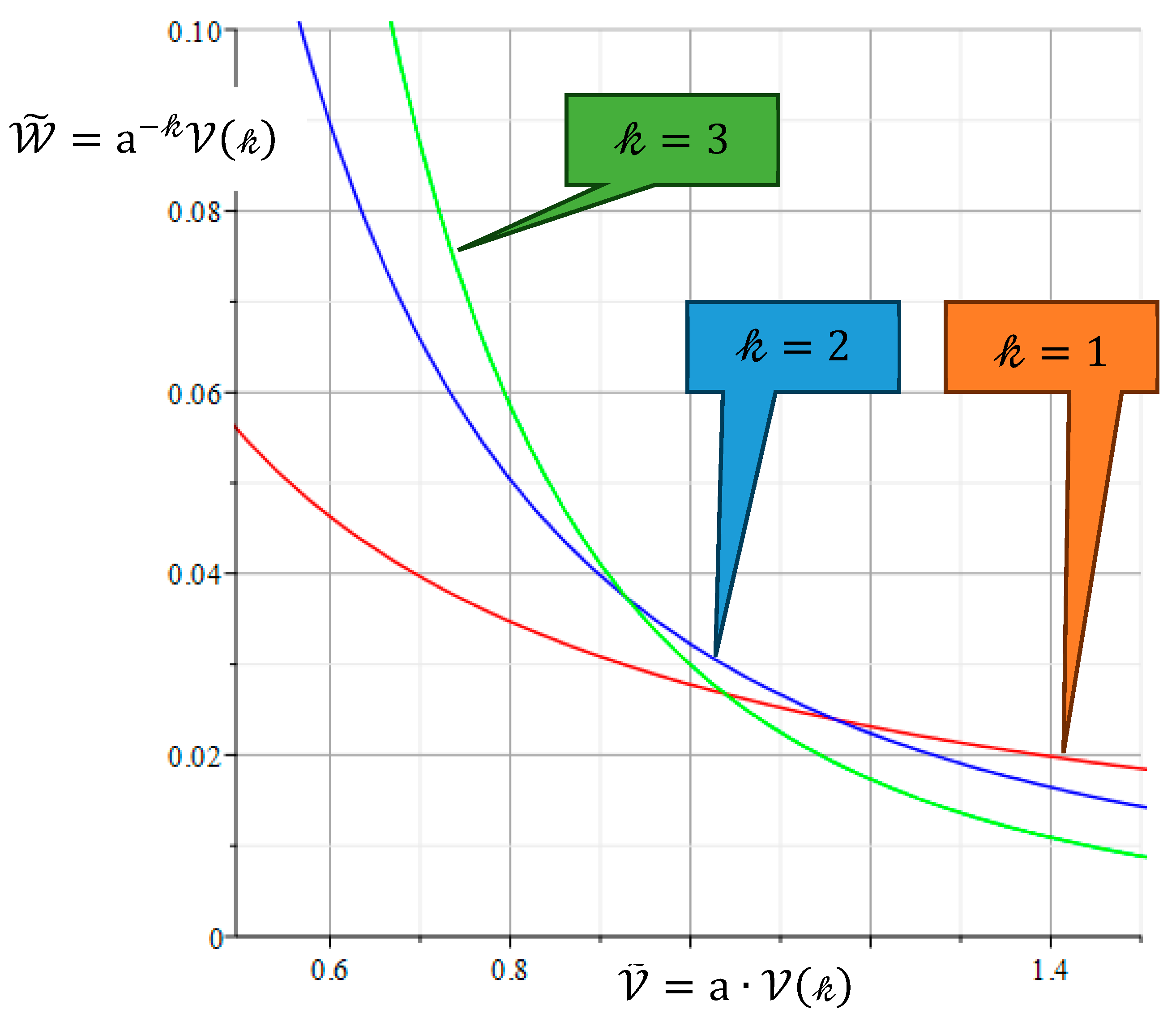

Pareto efficiency is a specific characteristic of multifunctional equilibrium. A situation is defined as efficient (Ehrgott, 2005), (Borm, Tijs, & van den Aarssen, 1988) or Pareto-optimal, if no entity can improve its satisfaction of needs through further activities without threatening any other entities. The central prerequisite for this state is perfect competition, without which the optimum cannot be realized in principle, as only this leads to the necessary equilibrium efforts (Fernandez, Monroy, & Puerto, 1988). Simply put, Pareto efficiency improvement makes at least one player better off, but no one worse off. Consequently, a strategy combination is called Pareto-efficient if no Pareto efficiency improvement is possible.

We examine the above solution from the viewpoint of inequalities theory and reveal the mathematical sense of the PARETO and NASH fronts (Monfared, Monabbati, & A Kafshgar, 2021). There exists the relation between objective functionals, which expresses as the isoperimetric inequality:

PARETO and NASH fronts were coincided in this case (Kobelev, Comment to the Article “Several Examples of Application of Nash and Pareto Approaches to Multiobjective Structural Optimization with Uncertainties” of N. V. Banichuk, F. Ragnedda, M. Serra, 2014). The fronts emerge as the equality case

Figure 5.

Pareto fronts for the states of Nash equilibrium for different shape factors.

Figure 5.

Pareto fronts for the states of Nash equilibrium for different shape factors.

Section 7 examines the solution of

Section 5 and

Section 6 from the perspective of inequalities theory, elucidating the mathematical significance of the PARETO and NASH fronts.

8. Conclusions

The premise of this study is that there is currently no definitive understanding of the factors that influence the states of nature. The game method for structural optimization problems can be applied in situations when the external loads are not definitively prescribed. Statistical decision theory is concerned with making decisions in the absence of precise probability information. The conflict between nature and operators (“ordinal players”) is examined through the lens of game theory (“substratum” game). The payout matrix is relevant for one ordinal player (“operator”) and the profit he makes if he employs his strategy while the second natural player (“nature”) is in a specific state. For greater accuracy, we propose referring to nature's strategies as states. The content of the consequent theory could be summarized as follows. In the matrix game there is a single pay-off matrix. From the viewpoint of the optimization theory, there is one goal function. Thus, the optimization problem is of scalar type. This goal function is the value of matrix game. The win of “nature” is the loss of “operator” as both players on the low-level. This game is antagonistic with only one goal function. The designer achieves the most appropriate value for this goal function.

In the bi-matrix game there are two pay-off matrices. From the viewpoint of the optimization theory, there are two goal functions. The optimization problem is of vector type. This goal functions come from the solution of bi-matrix game. The equilibrium state between interests of “nature” and “operator” results in the solution on game on the low-level. The designer achieves the most appropriate value for this goal function in accordance with the methods of vector optimization

The essence of the method is to identify the structure that optimally resists the worst external load. In the context of classical structural optimization, the "cardinal" players are tasked with assuming the role of "control functions." Similarly, the "cardinal" players are responsible for modifying the governing equations and payoff functions in the game formulations (“superstratum” game). If a relation between objective functionals, which could be expressed in terms of an isoperimetric inequality, exists, then the PARETO and NASH fronts coincide and emerge as the equality case of the isoperimetric inequality.

Funding

Nothing to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Replication of results

The numerical results presented in this document can be replicated using the methodology and formulations described here. The analytical expressions used in the examples are available upon request to the authors.

References

- Banichuk, N. V. (1973). On the game theory approach to problems of optimization of elastic bodies. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, Volume 37, Issue 6, p. 1042-1052. [CrossRef]

- Banichuk, N. V. (1990). Introduction to Optimization of Structures. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Battoo, R. (1999). An introductory guide to literature in aeroelasticity. . Aeronautical J., 103(1029):511-518. [CrossRef]

- Biezeno, C. B., & Grammel, R. (1956). Engineering Dynamics. London: Blackie.

- Borm, P., Tijs, S., & van den Aarssen, J. (1988). Pareto equilibria in multiobjective games. Tilburg : Tilburg University, School of Economics and Management. https://research.tilburguniversity.edu/en/publications/pareto-equilibria-in-multiobjective-games.

- Courant, R., & Hilbert, D. (2004). Methods of Mathematical Physics. https://doi/10.1002/9783527617210 : WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA,.

- Cox, S. J., & Overton, M. L. (1992). On the Optimal Design of Columns Against Buckling. SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis, Vol. 23, Iss. 2. [CrossRef]

- Denardo, E. (2011). A Bi-Matrix Game. Chapter 15,. In Linear Programming and Generalizations, International Series, Ser. Operations Research & Management Science 149, (pp. Springer Science+Business Media: Berlin. [CrossRef]

- Ehrgott, M. (2005). Multicriteria Optimization. Berlin Heidelberg, Springer-Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Eschenauer, H., Koski, J., & J., O. (1990). Multicriteria Design Optimization: Procedures and Applications. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

- Fernandez, F. R., Monroy, L., & Puerto, J. (1988). Multicriteria Goal Games. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, Vol. 99, No. 2, pp. 403-421, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1021726311384 .

- Geering, H. P. (2007). Optimal Control with Engineering Applications. NY, ISBN 978-3-540-69437-3: Springer.

- Greiner, D., Periaux, J., Emperador, J. M., Galván, B., & Winter, G. (2017). Game Theory Based Evolutionary Algorithms: A Review with Nash Applications in Structural Engineering Optimization Problems. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering,, Volume 24, Number 4, Page 703. [CrossRef]

- Henrot, A. (2006). Extremum Problems for Eigenvalues of Elliptic Operators. In Frontiers in Mathematics (pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-7643-7706-2). Basel: Birkhäuser. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, E., Thore, C., & Klarbring, A. (2017). Game theory approach to robust topology optimization with uncertain loading. Struct Multidisc Optim, 55, 1383–1397. [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, S. (2022). Nonlinear Functional Analysis: A First Course. Singapore: Springer.

- Kobelev, V. (1993). On a game approach to optimal structural design. Struct Multidisc Optimization, 6, 194-199. [CrossRef]

- Kobelev, V. (2014). Comment to the Article “Several Examples of Application of Nash and Pareto Approaches to Multiobjective Structural Optimization with Uncertainties” of N. V. Banichuk, F. Ragnedda, M. Serra. Mechanics Based Design of Structures and Machines, 42:1, 130-133. [CrossRef]

- Kobelev, V. (2023). Optimization of Compressed Rods with Sturm Boundary Conditions. In V. Kobelev, Fundamentals of Structural Optimization. Mathematical Engineering. (pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34632-3_5). Cham: Springer.

- Kobelev, V. (2023). Stability Optimization of Twisted Rods. In V. Kobelev, Fundamentals of Structural Optimization (pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34632-3_7 ). Cham: Springer.

- Lemke, C. E., & Howson, J. T. (1964). Equilibrium Points of Bi-Matrix Games. SIAM Journal, V. 12, pp. 413-423,.

- Lewis, A., & Overton, M. (1996). Eigenvalue optimization. Acta Numerica, 5:149-190. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, S. C., Weisshaar, T. A., & Ashley, H. (1969). Progress in Aeroelastic Optimization - Analytical Versus Numerical Approaches. AIAA Structural Dynamics and Aeroelasticity Specialist Conference, SUDAAR NO. 383. New Orleans: AIAA .

- Monfared, M. S., Monabbati, S. E., & A Kafshgar, R. (2021). Pareto-optimal equilibrium points in non-cooperative multi-objective optimization problems . Expert Systems with Applications , 114995. [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. (1951). Non-cooperative games. Annals of Mathematics. 2nd Ser., 54 (2): 286–295. JSTOR 1969529. [CrossRef]

- Parlett, B. N. (1998). The symmetric eigenvalue problem. Classics in Applied Mathematics, 20.

- Reddy, J. N. (2002). Energy Principles and Variational Methods in Applied Mechanics. Wiley.

- Szép, J., & Forgó, F. (1985). Bimatrix games. In J. Szép, & F. Forgó, Introduction to the Theory of Games. Mathematics and Its Applications, Vol 17 (pp.). Dordrecht: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Szép, J., & Forgó, F. (1985). Games against nature. In J. Szép, & F. Forgó, Introduction to the Theory of Games. Mathematics and Its Applications, vol 17. (pp.). Dordrecht: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Szép, J., & Forgó, F. (1985). Games played over the unit square. In J. Szép, & F. Forgó, Introduction to the Theory of Games. Mathematics and Its Applications, vol 17 (pp.). Dordrecht: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Tadelis, S. (2013). Game Theory. An Introduction. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Thore, C., Holmberg, E., & Klarbring, A. (2017). A general framework for robust topology optimization under load-uncertainty including stress constraints. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering,, Volume 319. [CrossRef]

- Thore, C.-J., Alm Grundström, H., & Klarbring, A. (2020). Game formulations for structural optimization under uncertainty. Int J Numer Methods Eng., 121: 165–185. [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. (1928). Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele. Math. Ann. , https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/BF01448847.pdf .

- von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (2004). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [CrossRef]

- Werner, D. (2018). Normierte Räume. In D. Werner, Funktionalanalysis. Springer-Lehrbuch. . Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Spektrum. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J. H. (1965). The algebraic eigenvalue problem, Volume 662. Oxford: Clarendon .

- Zettl, A. (2005). Sturm–Liouville Theory. Providence: American Mathematical Society.

- Zhang, F. (2011). Matrix Theory, Basic Results and Techniques. New York: Springer. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).