1. Introduction

Dung beetles, belonging to the family Scarabaeidae, play pivotal roles in various ecosystems worldwide. With an estimated 6,000 to 7,000 species, they are key agents of nutrient recycling, plant growth, seed dispersal and pest control, thereby contributing significantly to ecosystem functioning and biodiversity. These functions contributing to ecological health are particularly pronounced in livestock grazing environments. For example, it has been shown that

Onthophagus gazella enriches soil fertility through the process of burying dung [

1], and according to the meta-analysis, it has been revealed that dung beetles directly boost plant growth by an average of 17%, underscoring their integral role in sustaining environmental health and plant productivity [

2]. Additionally, the positive impact of the dung beetle,

Canthon pilularius, on forest ecosystems has been demonstrated by promoting the dispersal of plant seeds, thus contributing to the sustainability of plant communities [

3]. Further, the impact of

Onthophagus taurus and other Scarabaeidae species on controlling pest populations by burying dung highlights their value in natural and agricultural settings [

4].

Hence, the variety and presence of dung beetles may act as functional indicators for the health of ecosystems, suggesting their essential role in assessing environmental quality and stability [

5]. Despite their ecological importance, dung beetles face numerous threats, primarily from human activities. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to urbanization and agricultural expansion significantly affect their populations [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Braga et al. (2013) reported that in the Amazon region, dung beetle communities negatively affected species diversity, abundance, and biomass as a result of varying degrees of habitat disturbance [

7]. Given the dietary habits of dung beetles, which include consuming feces from various livestock, they can be adversely affected by chemicals remaining in the dung due to veterinary treatments such as the use of anthelmintics. Anti-parasitic compound like Ivermectin, widely used in livestock, can negatively impact dung beetle populations, affecting their communities, diversity, and survival [

11,

12,

13]. In addition, pesticides used in agriculture also have detrimental effects on the diversity and survival of dung beetles [

14,

15,

16]. In addition, climate change, driven by global warming, gradually impacts the life cycle, distribution diversity, and ecological functions of dung beetles, presenting challenges to their survival and the ecosystem services they provide [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Recognizing the vital ecological roles played by dung beetles and increasing threats to their habitats from human activities and climate change, the urgency for dung beetle conservation has prompted international efforts. Countries around the world are now implementing strategies aimed at protecting these insects, understanding that preserving dung beetle populations is integral to maintaining biodiversity and the health of ecosystems [

1,

24,

25].

The dung-rolling beetle,

Gymnopleurus mopsus is widespread in Mongolia and typically inhabits lowland grasslands predominantly grazed by cattle, sheep, and goats. It is also found in steppe, semidesert, and desert habitats across central, southern, and eastern areas of Mongolia [

26].

G. mopsus, was commonly found across South Korea in field livestock grazing areas until the 1970s. Since then,

G. mopsus has not been observed, leading to its designation as "Regionally Extinct" classified under "Class II Endangered Species" in South Korea [

27,

28,

29].

Once a developing country, South Korea has experienced rapid economic growth, which has been accompanied by a burgeoning interest in environmental protection, animal welfare, and the conservation of biodiversity. This heightened awareness has led to an increase in eco-friendly, free-range livestock farming practices. Such agricultural improvement has, in turn, expanded the habitats suitable for dung beetles, gradually improving the environmental conditions necessary for their survival. In contrast to the situation in South Korea, Mongolia presents a markedly different environmental habitat. Across the nation, extensive areas of eco-friendly pastures that do not employ anthelmintics or pesticides are prevalent. This practice provides an ideal habitat for G. mopsus, allowing the species to flourish.

In this study, we investigated the ecological restoration potential of the dung beetle G. mopsus, which has gone extinct in South Korea, by assessing the adaptability of the same species currently inhabiting Mongolia to the natural environment of South Korea. To achieve this, the life history of G. mopsus was monitored under the field conditions of South Korea, addressing the following questions: 1) What patterns are observed in the emergence timing after hibernation during the first year after introduction from Mongolia? 2) What is the survival rate of adult G. mopsus? 3) Do they exhibit normal reproductive behavior and produce F1 offspring? 4) What patterns are observed in the timing of hibernation entry for adult G. mopsus that have completed hibernation in Korea and the F1 offspring born in the same year? The answers to these scientific inquiries will offer insights for evaluating the potential for successful establishment of dung beetles, introduced from Mongolia to South Korea, when released into the natural environment of Korea.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dung Beetle Colony

Gymnopleurus mopsus dung beetles were introduced from Eastern Gobi region in Mongolia (Saikhandulaan, 44°58′18.76″N 110°05′53.51″E) on July to August 2019 because the genetic characteristics (Mitochondrial

COI sequences) between Mongolia populations of

G. mopsus and Korea populations shows an ancestral haplotype [

27,

30].

In July and August 2019, a total of 200 adult G. mopsus individuals were meticulously collected by hand in the Eastern Gobi region of Mongolia, specifically at coordinates 44°58′18.76″N latitude and 110°05′53.51″E longitude. After successfully completing the quarantine process for the G. mopsus imported from Mongolia to South Korea, they were then transported to the insect breeding room at the National Institute of Ecology, Research Center for Endangered species, where they were carefully raised and nurtured. The dung beetles were maintained in square plastic cages (measuring 460 mm × 319 mm × 244 mm in height, provided by KOMAX, Seoul, South Korea) covered with ventilated lid. Each plastic container was prepared with a substrate mixture to facilitate the ecological experiments. The substrate consisted of an equal ratio mixture of river sand and vermiculite (Verminuri, Green Fire Chemicals, Hongseong, South Korea). This mixture was added to the cages to a depth of 20 cm to provide sufficient volume for the activities of G. mopsus. The moisture content of the substrate was adjusted to approximately 7-10% to meet the natural humidity conditions using a data logger (HOBO, MX2307). The consistency of the substrate was monitored and maintained to ensure appropriate conditions throughout the study period. They were kept in a controlled laboratory environment with a temperature maintained at approximately 25±1°C, 70% relative humidity, and subjected to a 14-hour light to 10-hour dark (L:D) photoperiod cycle. Additionally, dung beetles were provided with fresh horse dung every two days. We collected horse dung from grazing land on Jeju Island (located at coordinates 33°25′18.28″N latitude and 126°29′30.50″E longitude), and to preserve its freshness during transportation, we used a large amount of ice packs. The dung was stored frozen at -24°C for a duration exceeding two weeks and thawed at room temperature as needed.

2.2. Field Cage

For the semi-field monitoring, the field cage was established at the Endangered Species Restoration Center located within the National Institute of Ecology in Yeongyang County, South Korea. The selected site was demarcated into rectangular plots measuring 2.2m by 4.2m. Excavation work was conducted to a depth of 60cm, followed by the installation of a 15mm thick plywood base to ensure a level and stable ground surface. To prevent rapid temperature fluctuation, 50mm thick styrofoam sheets were fitted at the bottom and along the sides of the excavated pits. Custom-manufactured steel cages, with dimensions of 2m (width) × 4m (length) × 2m (height), were then installed precisely within the prepared plots. To isolate the experimental environment from external biotic interference, the surfaces of the steel cages were lined with insect-proof mesh netting with a 1mm mesh size. The pit inside the steel cage was backfilled with river sand to bring the surface level to that of the surrounding ground. This experimental setting was intended to simulate natural ground conditions for the subjects of the experiment while allowing for controlled observation and monitoring of their behavior and interactions within the enclosure.

2.3. Overwintering and Spring Emergence

To induce a state of hibernation in the dung beetle population and align with the natural seasonal transitions, the laboratory rearing conditions were systematically altered starting in September 2019. From September 2nd to September 16th, the laboratory temperature was maintained at 22±1℃ with a 14:10 (L:D) photoperiod. From September 16 to September 30, the conditions were adjusted to 20±1℃ with a 12:12 (L:D) photoperiod. Subsequently, from September 30 to October 29, the temperature was set to 18±1℃ with a 10:14 (L:D) photoperiod. After confirming that all dung beetle individuals had entered hibernation under laboratory conditions, they were transferred to the pre-prepared field cage on October 29, 2019. The plastic container (460 mm × 319 mm × 244 mm in height) used to house the dung beetles under laboratory conditions was buried in a 40 cm deep pit inside the field cage. To facilitate aeration while preventing rapid temperature fluctuations, straw mats were placed over the container lids. An additional layer of sand, approximately 5 cm high, was added on top of the straw mats, followed by a 50mm thick styrofoam board, a 15mm wooden plywood sheet, and another layer of straw mats, in that order. This multilayered covering was designed to insulate the containers from extreme temperature changes and emulate the subterranean conditions conducive to hibernation.

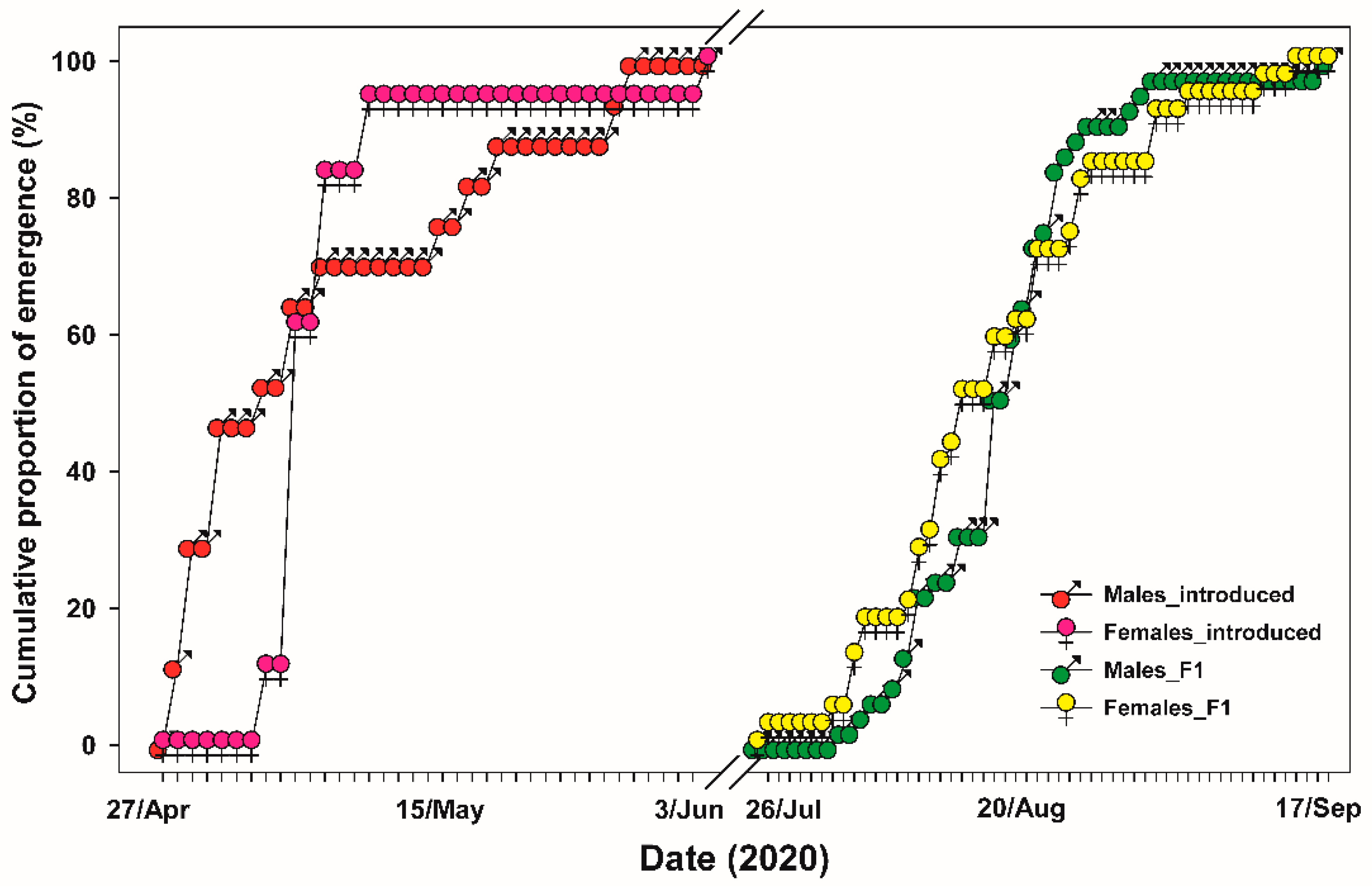

To monitor the post-hibernation emergence of the adult dung beetles, which comprised 34 individuals (17 females and 17 males) that hibernated within the containers, the insulation layers—consisting of styrofoam boards, wooden plywood, and straw mats—were removed on March 1, 2020. From this date, the beetles were provided with 200g of thawed horse dung that stored in freezer as feed three times a week at a consistent schedule of 1 PM to check for signs of emergence. The frequency of monitoring was increased to daily from 1 April onwards. The emergence of individuals from hibernation was determined by their activity outside of the containers. Once dung beetles were observed emerging and becoming active outside, the date was recorded, and after determining their sex, they were sequentially transferred in pairs to containers designated for life history monitoring. To discriminate sexes of

G. mopsus, we identified the protibial spur of adults whether is curved outward (female) and is curved downward (male) [

31]. Meteorological data, including air/soil temperature, humidity, and precipitation, were collected from the first week of November 2019 to the first week of November 2020 to document seasonal weather trends (file S1, Supplementary Online Material).

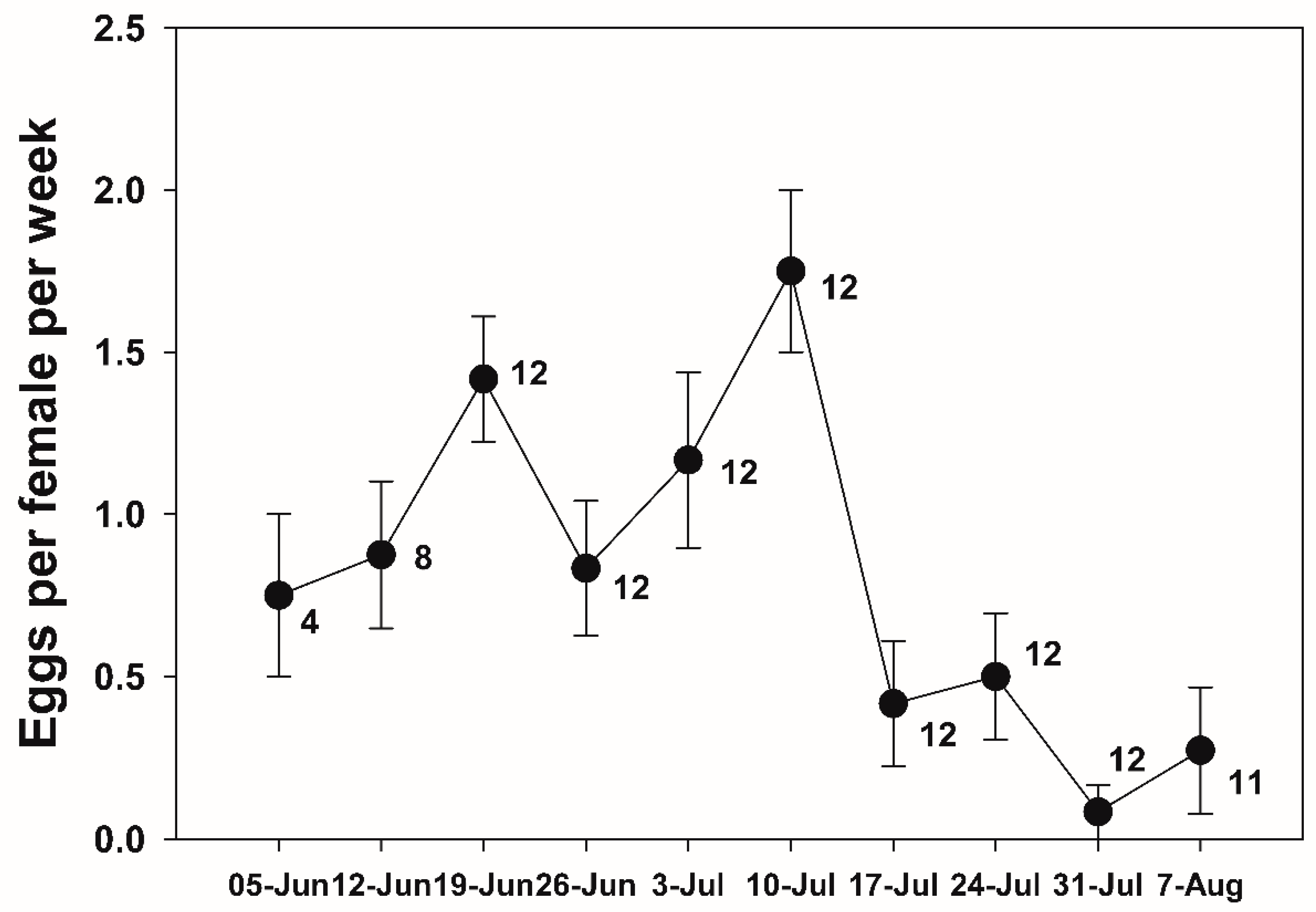

2.4. Survival and Reproduction Monitoring

The breeding behaviors of adult dung beetles, translocated from Mongolia to South Korea, were monitored post-hibernation under field cage conditions. For this purpose, cylindrical acrylic containers (20cm in diameter × 25cm in height) were filled with a 1:1 mixture of river sand and vermiculite to a depth of 20cm and embedded to be level with the ground within the field cages. Nylon lids (1mm mesh) were used for ventilation. The beetles that emerged from hibernation were sequentially paired and housed in these breeding monitoring containers, with a total of 17 pairs being monitored for survival. For the monitoring of oviposition, one pair out of the total 17 pairs of dung beetles was excluded from monitoring due to early mortality. Each container was supplied with 150g of room-temperature thawed horse dung three times a week between 1 PM and 2 PM, while monitoring for brood dung ball rolling behavior and survival. To minimize stress on the adult dung beetles, the collection of brood dung balls was conducted once a week, specifically on Fridays. During each collection, the number of brood balls and the date of collection were recorded. Each collected brood ball was buried at a depth of 7 cm in square plastic containers (measuring 65.4 mm × 65.4 mm × 98.2 mm in height, provided by SPL, Cat. No. 310075) filled to a height of 8 cm with river sand at a soil moisture content of approximately 7-10%. The tops of the containers were ventilated with nylon mesh.

2.5. Second Generation Emergence

For monitoring the emergence of second-generation adults from the brood balls, square plastic containers (65.4 mm × 65.4 mm × 98.2 mm, SPL) were filled to a height of 3cm with the same sand-vermiculite substrate and the brood balls were then placed, covering them up to 8cm with the substrate. The containers were buried to a depth of 8 cm to align with the surrounding soil level, and lids fitted with nylon mesh were used to prevent dung beetle escape and ensure ventilation. To protect against water accumulation inside the containers during rain, straw mats were placed over all containers. The containers in which dung beetle larvae were being reared were monitored three times per week. The duration of the developmental time of the dung beetles, from egg to adult stage, was estimated based on the time elapsed from the collection of the brood dung balls to the emergence of the adult beetles.

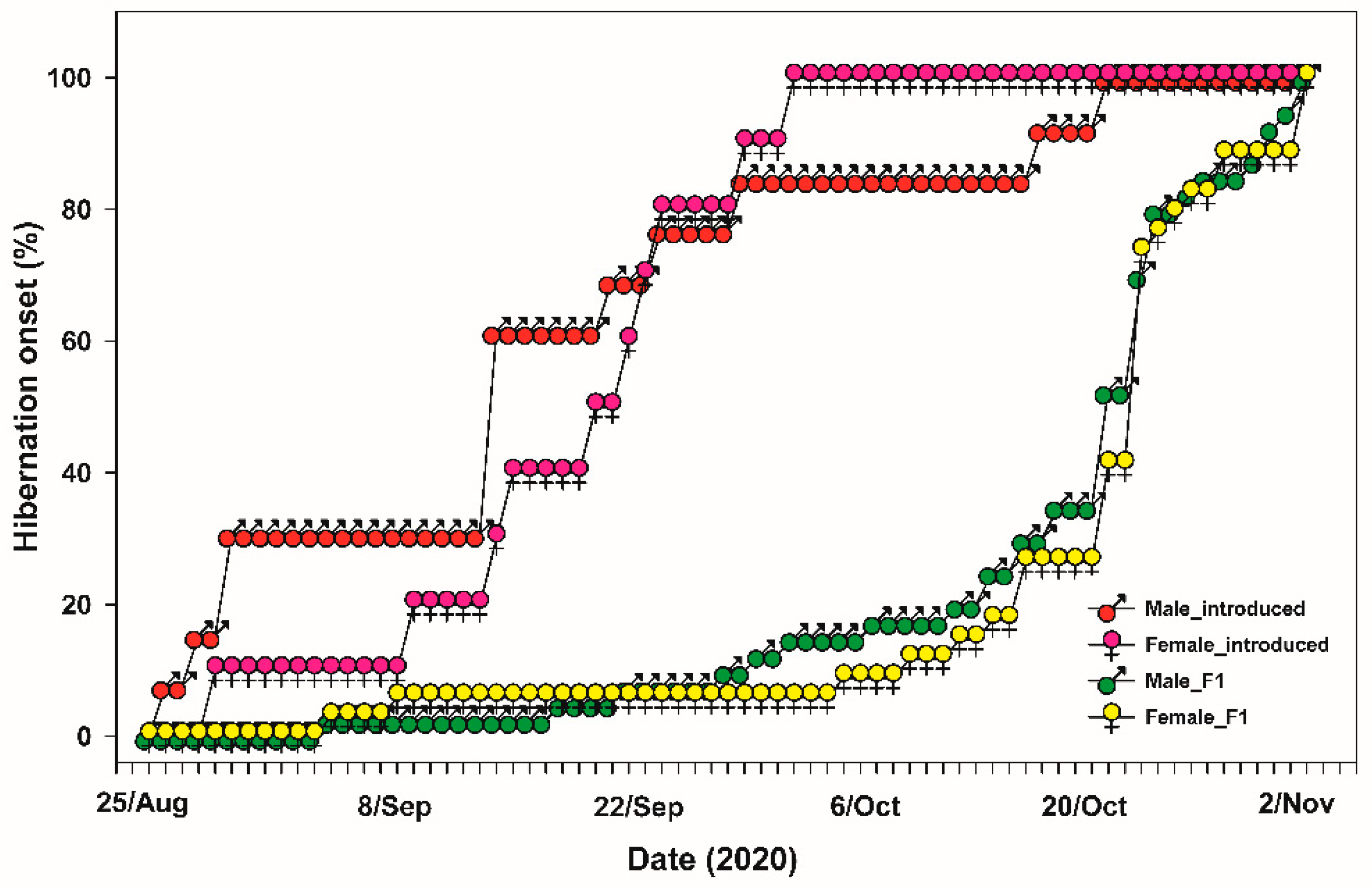

2.6. Hibernation Onset

To monitor the timing of hibernation entry, first-generation dung beetles that had completed breeding were housed in pairs, while the newly emerged second-generation adults were housed individually. The adults introduced from Mongolia were maintained under the same conditions and used for reproduction monitoring to observe their timing of entering hibernation. For the second-generation beetles that emerged in 2020, they were housed in square plastic containers (7.2cm × 7.2cm × 10cm, SPL) filled to a height of 7 cm with a 1:1 mixture of river sand and vermiculite. Second-generation beetles were fed 20g of horse dung three times a week while monitoring their hibernation onset. Throughout the monitoring period, an individual was considered to have entered hibernation if it remained inactive and did not emerge from its burrow for over two weeks, coupled with an absence of feeding activity. This criterion was equally applied to both generations.

2.7. Measurement of Adult Beetle and Brood Dung Ball

The body sizes of both first and second-generation adult dung beetles as well as the brood dung ball sizes were measured. For data collection, the body length and thorax width of the adult beetles, along with the length and width of the brood dung balls, were measured using a vernier caliper (EHC-150, EX-POWER). The size of adult beetles was measured at the time of their emergence. Similarly, the size of the brood dung ball was measured at the time of their first collection.

2.8. Data Analysis

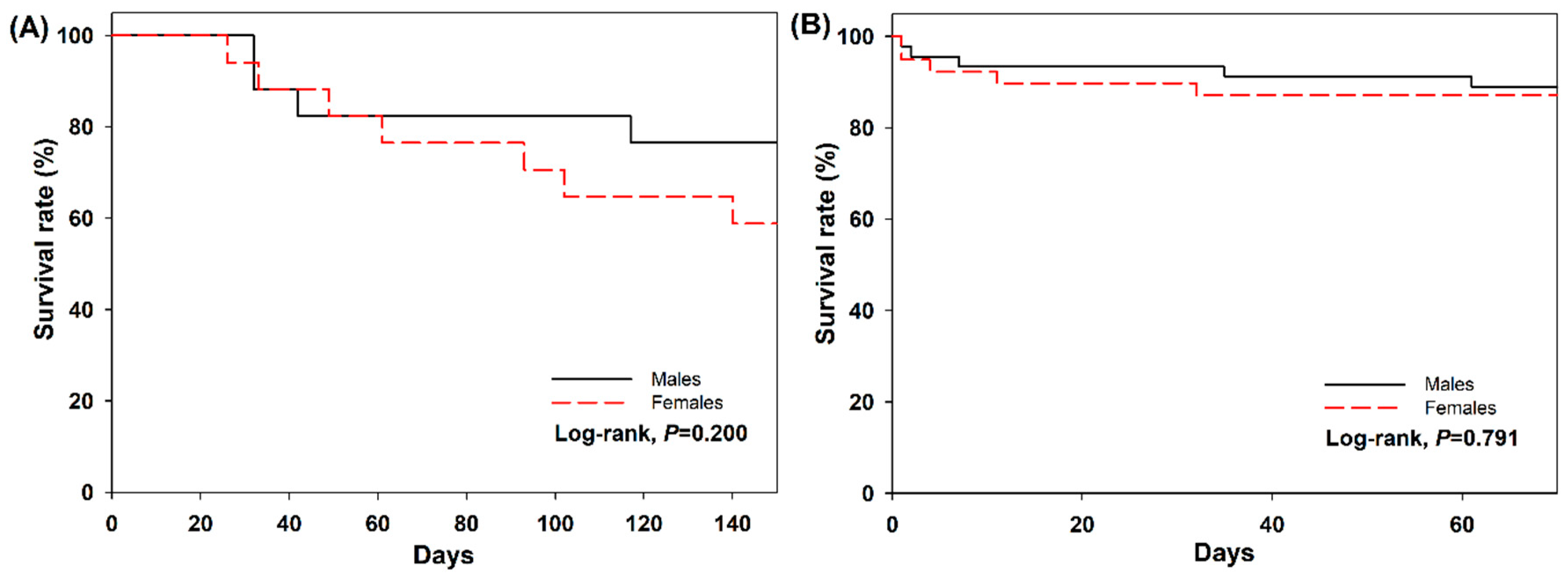

The collected data, including body size measurements and larval developmental times of dung beetles, were subjected to statistical analysis. We employed Student’s t-tests to compare means and identify any significant differences in these parameters. We used Shapiro-Wilk W tests to check for data normality and applied Levene’s tests to verify homogeneity across the dataset. For survival data, we utilized the Kaplan-Meier method to generate survival curves. This method allowed us to estimate the survival function from lifetime data, thereby providing a clear picture of survival rates over the course of the study. To further analyze survival data, significant differences between gender groups were examined using log-rank tests. This non-parametric test is effective in comparing survival distributions of two samples. By applying the log-rank test, we were able to determine if the survival rates significantly differed between male and female groups of G. mopsus over time. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA version 8.0 (Statsoft, USA).

4. Discussion

In this study,

G. mopsus adults introduced from Mongolia successfully hibernated through the spring following their arrival under Korean climatic conditions. Additionally, as demonstrated in our semi-field monitoring, the

G. mopsus that emerged from hibernation successfully mated, with each female producing approximately 6.8 offspring. In general, ball-rollers like

G. mopsus are known to produce relatively fewer offspring, investing significantly in offspring care. For example, females of several African species of Scarabaeus, including the ball-roller

Scarabaeus sacer, lay about 1-4 eggs during the breeding season [

32]. Therefore, our findings suggest a high potential for these beetles to adapt and thrive in Korea’s climatic conditions. These results are in line with those from previous studies demonstrating that dung beetles introduced from abroad can adapt and thrive in new environments [

33]. In the case of Australia, to manage pollution and pest outbreaks, such as biting flies, associated with dung accumulation in extensive livestock grazing areas, 43 species of dung beetles were introduced from overseas starting from the 1960s. Among them, 23 species successfully established themselves in the field environment [

4,

34]. Additionally, Australia is currently conducting Dung Beetle Ecosystem Engineers (DBEE) project, which involves importing dung beetle species such as

Onthophagus andalusicus and

Gymnopleurus sturmi from overseas. This project aims to identify species that can adapt effectively to the Australian grazing environment [

35]. Similarly, in the United States, to address pollution issues caused by dung in livestock pastures, 23 species of dung beetles were introduced from overseas. Among them, three species successfully adapted to and established themselves in the outdoor environments of the southern United States [

36].

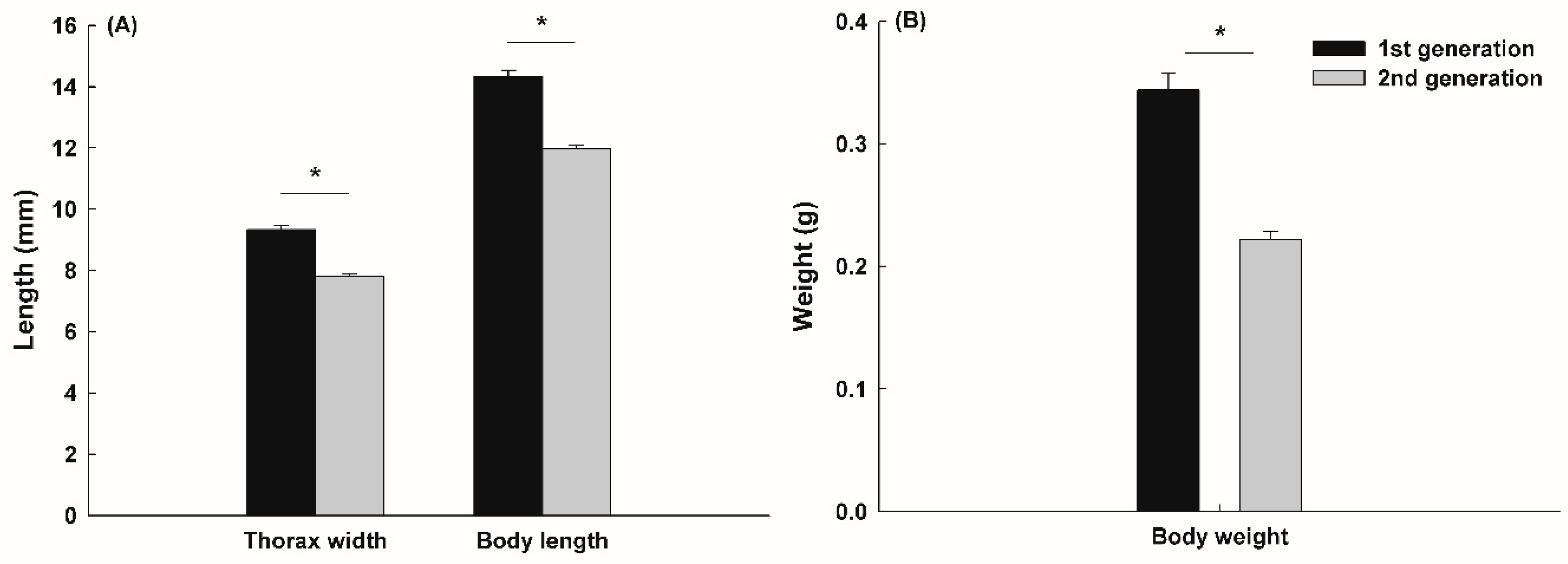

Our study showed that the second-generation

G. mopsus adults that emerged as adults in Korea exhibited smaller body sizes compared to the first-generation adults. We suppose that the reason second-generation

G. mopsus adults were smaller than the first generation is likely due to environmental stress experienced during the larvae’s development. In this study, the brood dung balls containing individual

G. mopsus larvae were managed in relatively small square plastic cages, approximately 0.4 liters in volume, which could have made it difficult to maintain stable environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity. Additionally, the plastic cages, except for the ventilated lids, restricted air circulation in other directions, potentially limiting the influx of oxygen necessary for growth. Moreover, the brood dung balls were maintained in soil at a relatively shallow depth of about 7cm within these cages, which could have also contributed to significant fluctuations in temperature due to the shallow depth. Generally, it is known across various insect species that adults emerge smaller when larvae are exposed to stress. Larvae of the lady beetle

Harmonia axyridis, when exposed to 33℃ during their third and fourth instar stages, emerged as adults that were smaller in size compared to larvae that were raised consistently at 20℃ [

37].

Additionally, the dung beetle

Onthophagus taurus, when exposed to high temperature fluctuations during the larval stage, emerged as adults approximately 14% smaller than those larvae raised under lower temperature fluctuations [

38]. In terms of oxygen limitation, a restricted oxygen supply during the larval phases of

Manduca sexta results in significantly smaller adult sizes compared to control groups [

39]. Therefore, further research is needed to test the growth conditions of

G. mopsus larvae within the brood dung balls under low environmental stress to better understand the factors influencing their development.

During the course of our semi-field monitoring, we observed that the second-generation of

G. mopsus adults entered hibernation later than the first-generation adults. This delay is often necessary for second-generation adults across various species, as they require additional time to accumulate the necessary energy reserves and undergo crucial physiological developments to survive the harsh winter conditions. This pattern of delayed hibernation in second-generation adults is not unique to

G. mopsus but is also observed in other beetle species. For instance, similar findings were reported in ground beetle species like

Harpalus affinis and

Pterostichus melanarius, where the first-generation adults entered hibernation earlier than the second generation [

40]. The second generation’s later emergence in the season necessitates extended periods to gather sufficient resources and complete their developmental processes, highlighting a vital adaptive strategy. This strategy ensures that despite their delayed development, these insects can still achieve optimal survival and reproductive success within the environmental constraints they face. In our study, the survival rate of the second-generation adults that entered hibernation later than the first generation was over 87%. This suggests that the delayed onset of hibernation did not negatively impact their adaptation to the field conditions in South Korea.

5. Conclusion

This study constitutes the first attempt to restore G. mopsus in South Korea, a species extinct in the wild, through the introduction of individuals from Mongolia. It provides fundamental rearing methods and semi-field ecological monitoring data that assess the potential for adaptation of G. mopsus to a new environment.

Our research findings indicate that

G. mopsus was capable of hibernating in South Korea’s field environment, and adults successfully can reproduce following hibernation, leading to the emergence of a second generation. However, these second-generation adults were smaller in body size compared to the first generation, suggesting that they experienced stress during larval development. Nevertheless, our results do not necessarily imply that

G. mopsus cannot adapt to field environments in South Korea. Ball-rolling dung beetles like

G. mopsus have the ability to mitigate stress by selecting optimal environments for larval development, as they actively bury their brood dung balls in locations that provide favorable conditions for larval growth [

41]. Follow-up studies are currently underway to enhance our understanding of the potential for Mongolian-introduced

G. mopsus to establish and thrive in the natural habitats of South Korea. These studies include more realistic field release experiments that are essential for assessing the species’ adaptability to local environmental conditions.