1. Introduction

The cost and weight of sandwich materials are lower than that of single materials, and they have better mechanical properties and process properties, which are gradually being widely used. Typically, a sandwich construction has three sections: a top, middle, and bottom segment with a core located in the center and skins at the top and bottom, where the skins have the same material and thickness while the core can be made of almost any material or architecture.[1] The face sheets require high strength and the core requires light weight.[2] Because of their extraordinarily high stiffness-to-weight and strength-to-weight ratios,[3,4] sandwich plates are very often utilized in engineering settings like aerospace and automotive applications, naval vessels, ships, bridge construction and wind turbines.[5–7] Sandwich structures have many benefits, including the need for high-strength, lightweight materials and the ongoing discovery of new materials, which has led to their continual usage in structural design.[8] The conventional skins of constant stiffness composite laminates (CSCL) consist of straight fibers whose stiffness, such as elasticity and flexibility, remains uniform or constant in all directions in the plane of the material. While VSCL are typically made by carefully designing and arranging layers of different materials or by altering the path of reinforcing fibers (curvilinear fiber) in the construction.[9] It is obvious that a more flexible method of increasing a plate's rigidity can be achieved by using VSCL.[10] Researchers have recently used theoretical analysis, empirical and semi-empirical modelling, numerical simulations, and experimental testing to examine the mechanical properties of sandwich constructions. [11] Experimental data is typically used to verify the modelling,[12] while numerical simulations are preferred for their computational efficiency and rapid turnaround time.[13]

The foundation for VSCL has been laid by numerous academics using the statics analysis of CSCL sandwich plates. Kant et al.[14] have analyzed the fundamental frequency of CSCL laminates and sandwich plates and the solution method used is finite element. They used a higher–order refined theory as the basis for their modelling and as parametric inputs, they systematically changed the plate thickness, the ratio of core to skin thickness, and the boundary conditions. Furthermore, their investigation included a rigorous comparative analysis with established methods to demonstrate the precision and robustness of their chosen theory. Yuan et al.[15] looked at the vibration properties of conventional sandwich plates that are rectangular in shape, including the natural frequencies and modes, using the spline finite strip method and it was concluded that the techniques of single-plate analysis were not applicable to the structural analysis of most plat constructions. To lower the computational cost in the fundamental frequency prediction of sandwich plates and composite laminates, Mantari et al.[16] presented a simplified FSDT. Reducing the amount of unknowns in the modeling computations allows for the reduction of the number of degrees of freedom. Comparing the computational results with those of other computational models serves as verification of the method's accuracy.

The advent of advanced technologies ushered in a new era of VSCL plates and revolutionized the design landscape of composite plates. By manipulating the fiber orientation, VSCL plates offer improved mechanical properties by altering the stiffness distribution. Gürdal et al.[17] used a numerical model to solve static problems such as displacement field and overall stiffness of VSCL symmetric laminates. They pointed out that by choosing an appropriate starting and ending angle, the given loading conditions can be better considered and a certain stiffness can be achieved or possibly the buckling behavior can be improved. Lopes et al.[18] predicted various failure modes of VSCL plates in compression and simulated the first layer failure in post-buckling. Finite element modelling was used to predict the physical failure criteria for different modes of failure of the VSCL plates. Khani et al.[19] applied a new solution to incorporate the failure criteria for strength into the parameter space of the laminates. The numerical results showed an increase in strength compared with the quasi–isotropic construction. Akhavan et al.[20] analyzed the law of variation of fundamental frequencies and mode shapes with fiber orientation angles for VSCL laminates, third-order shear deformation theory (TSDT) was the modelling technique applied, and p-version finite elements were employed in the solution. Through data comparison, they explored some connections that exist between fiber orientation angles and fundamental frequencies.

Existing research on VSCL plates focuses on statics and has only investigated their dynamics to a limited extent, which warrants further research into their dynamics in future studies. Houmat[21] and Hachemi[22,23] are among the few scholars who have performed free vibration analysis of VSCL sandwich plates. Houmat’s modelling theory is three-dimensional elasticity theory, while Hachemi’s analysis is grounded in both layer-wise theory and HSDT. They both chose p-version finite elements as the solution method. By adjusting factors including fiber orientation angles, boundary conditions, and skin-to-core thickness ratios, the variation patterns of fundamental frequencies as well as other dynamic responses were examined, highlighting the benefits of VSCL sandwich plates in structural investigations.

Systems of partial differential equations that typically have difficult-to-find closed-form solutions characterize engineering challenges.[24] Consequently, engineers and researchers frequently turn to approximative numerical techniques to solve such systems. These methods include the finite element, the p-version finite element, the Rayleigh–Ritz methods, the finite volume method and so on. Bellman et al.[25] developed the differential quadrature technique (DQM) for solving partial differential equations. DQM has the advantage of having a smaller number of discrete points with higher computational accuracy. Liu[26] utilized Mindlin plate theory as the modelling theory and applied DQM to the investigation of rectangular plate buckling. Liew et al.[27] used DQM to conduct a static study of a rectangular plate on Winkler’s basis, utilizing FSDT as the modelling theory. This is the first successful application of DQM to thick–plate problems. Based on previous work, Liew et al. [28] applied the moving least squares differential quadrature (MLSDQ) to calculate and study the fundamental frequency of symmetric laminates of medium thickness and the modelling theory is FSDT. The free vibration problem of sandwich plates with functional grades on an elastic foundation was investigated by Fu et al.[29]. They employed DQM, and the modelling theory is NSDT. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet applied the DQM to the free vibration analysis of VSCL sandwich plates modelling by FSDT.

This work proposes an FSDT-based DQM approach to give a reasonably accurate and computationally cheap computer model for the free vibration analysis of VSCL sandwich structures. The plate consists of two VSCL skins and an isotropic core. Based on the FSDT, the governing equations were derived using the von Kármán strain–displacement relationship and Hamilton's principle. By applying the DQM, the fundamental frequencies of the sandwich plates were determined numerically, and the impacts of several parameters on the plate's vibration behaviour were examined.

This is how the remainder of the paper is structured. The modelling procedure and analytical method employed are stated in the second section. In the third section, numerical applications and discussion, encompassing both CSCL and VSCL sandwich plates, are presented. The last section summarizes the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Formulation

2.1. Geometric Description

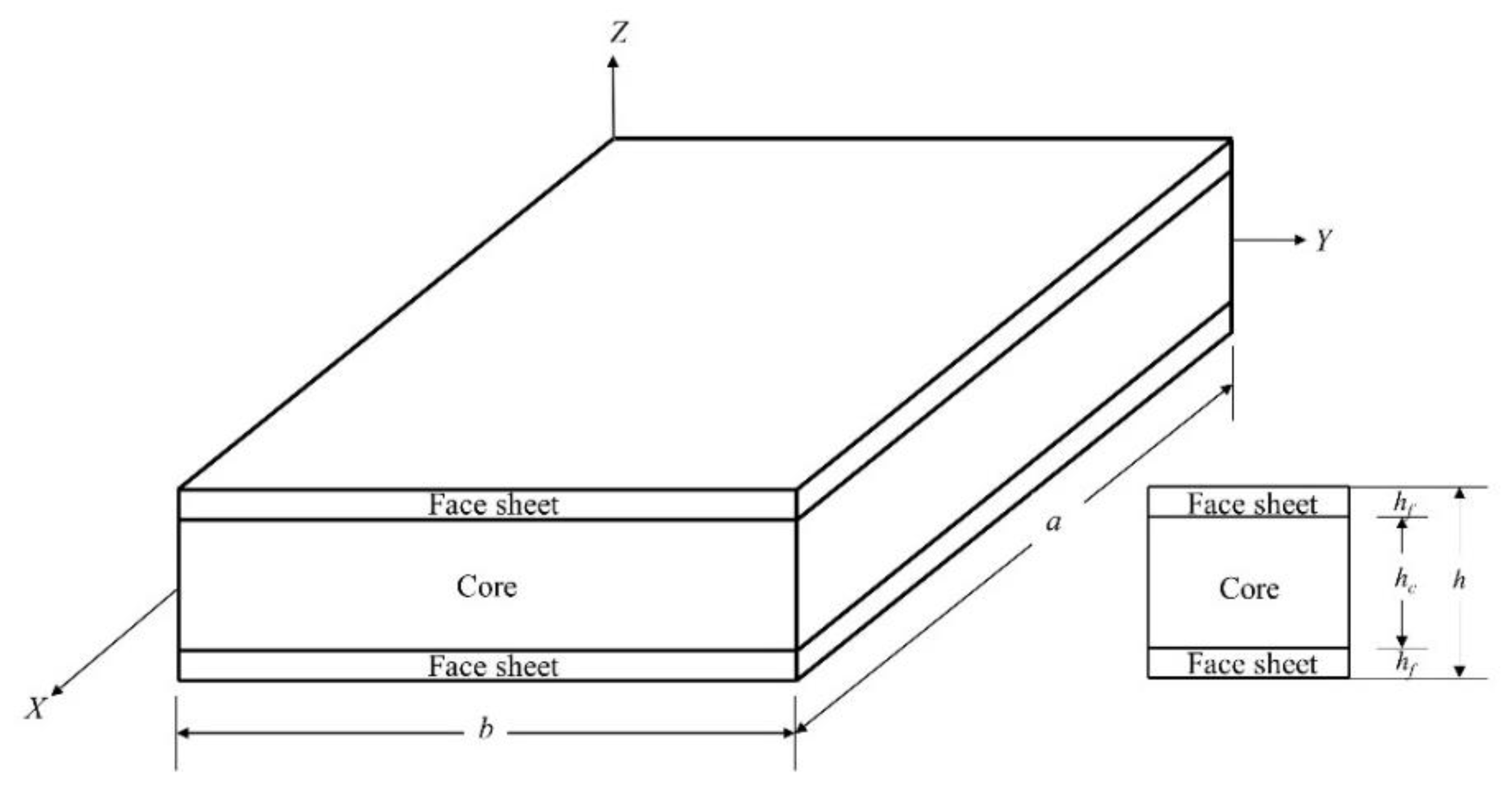

The geometrical design and parameterization of a sandwich plate with variable stiffness skins are displayed in

Figure 1. The upper and lower composite skins, every stratum of the skin consisting of single or laminated composite layers with curvilinear fibers, with a soft core in the centre, make up the entire plate. Assume that the dimensions of the plate are

a,

b, and

h, respectively, for length, breadth, and thickness. The total thickness

h can be decomposed into upper and lower skins

and intermediate core

. It is considered that every interface on the board is flawlessly integrated. Given that the entire plate consists of

N layers, the thickness of each single layer of the face sheet is

. The entire plate's Cartesian coordinate system is specified as

.

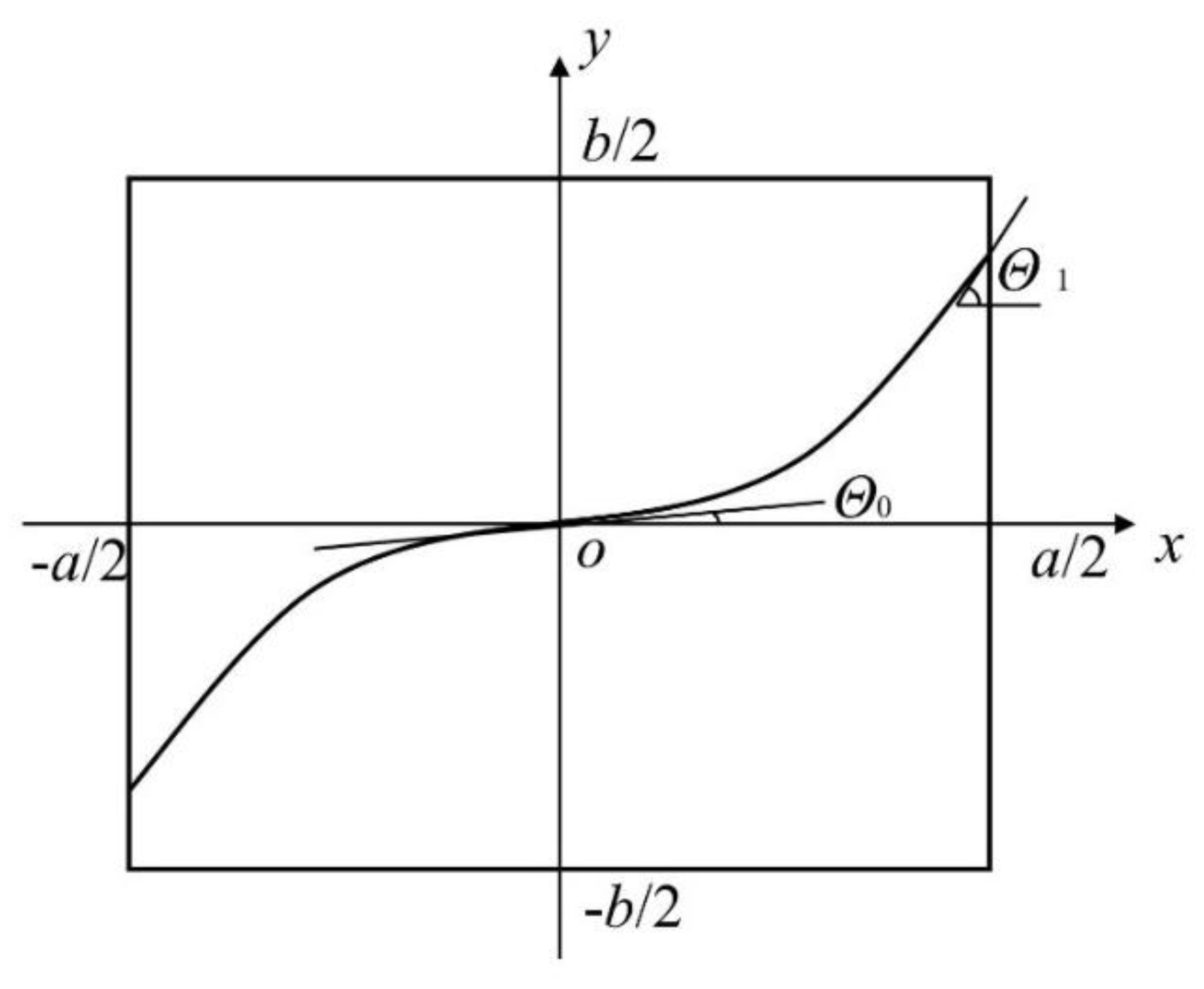

To simplify the definition, the point of central symmetry of the reference path is typically specified to be at the center of each individual layer of the skin, as illustrated in

Figure 2, and the Cartesian coordinate system is defined as

. Assuming that the angle of the fiber direction varies linearly along the x–direction, it is expressed mathematically as follows:[20]

where,

is the starting angle of the fiber, characterizing the angle between the tangent of the fiber curve at the center point and the

x–axis of the relative horizontal line, the fiber’s ending angle, or

, is the angle formed by the tangent of the fiber curve and the x-axis of the relative horizontal line at the location where the layer's outer boundary is

, and

is the plate length.

Integrating the above equation gives the reference path for the curvilinear fiber placement as follows:

2.2. Modelling Theory

Between the skin and core materials of sandwich plates, there are significant differences in stiffness and material properties, making the performance analysis of the sandwich structure quite intricate. As a result, the calculation model selected has a significant impact on how accurately the sandwich structure is calculated.[30] Transverse shear deformation is not taken into account by the classical laminated plate theory (CLPT), which is predicated on Kirchhoff's assumptions. Therefore, for plates of moderate thickness, CLPT's estimates on both static and dynamic analysis are biased.[31–34] For the purpose of this study's free vibration analysis of sandwich plates, the author employed the FSDT modelling theory,[35] which accounts for the impact of shear deformation.

Based on Kirchhoff’s first two assumptions, the third assumption was not considered. In case a symmetric sandwich plate is used, the vibrations in the transverse and in-plane directions are separated by the symmetry in the

z direction, and the in-plane deformation at

can be ignored. The displacement field has the following expression.[36]

where the displacements along the three coordinate axes are denoted by

u,

v, and

w, and the midplane of the plate rotates about the

x and

y axes at angles

and

, respectively.

According to the von Kármán strain–displacement relationship, the components of the linear strains can be expressed as follows:

Applying Hooke’s law and assuming plane stress, the stress components of the plate areas are obtained in the following way:

where

are given in the following way:

Where

where

,

, and

are the mechanical properties and

k = 5/6 is the shear correction factor used in this study. [37]

Hamilton's principle can be used to generate the moving equations in the following way:[35]

where

U is the strain form and

T is the kinetic form of energy, respectively.

The strain energy can be shown in the following way:

The kinetic energy can be shown in the following way:

The moving equations for the sandwich plate's free vibration may be acquired by substituting equations (4)–(7), (9) and (10) into equation (8):

where

.

2.3 Equation of Motion

The stress resultants

Mij and transverse shear force

Qij can be determined by integrating the stresses in each single layer along the direction of thickness.

Equation (11) can be substituted with equation (12) to assemble the following formulations for the governing equations of the sandwich plate's free vibration.

where

Aij and

Dij are the stretching and bending stiffnesses, respectively.

2.4. Differential Quadrature Method

DQM is essentially a differential equation in the function at each node of the derivative with the calculation of the region of all nodes at the function value of the weighted sum to replace.[25] The required differential equation's numerical solution can be found in the resultant system of equations. This is how DQM transforms the differential equation solution problem into the linear equation system solving problem.[38–40] Appendix I provides the specific implementation of this technique.

To simplify the calculation, for the DQM discretization of the moving equations, the expressions for the weighting coefficients were obtained:

The separating variables for the displacement terms (

w,

, and

) can be written in the following way:

where

is the vibration mode function,

and

are the rotational angles functions and

is the fundamental frequency of the sandwich plate.

To facilitate subsequent calculations and comparisons, the data are dimensionless as follows:

where

represents

at

x = 0 and

represents

at

x = 0.

Substituting equations (16)–(18) into equations (13)–(15) and performing a DQM discretization, the governing equations can be shown as follows:

where

To simplify the calculation, equations (19)–(21) can be stated more succinctly in the following way:

Similarly, the boundary conditions can be derived by discretization using the DQM

The solution of the specific matrix is given in the next section.

To find the basic frequencies, or eigenvalues, and the accompanying eigenvectors, all mesh points were divided into two groups: internal domain points and boundary points. The boundary points, indicated by {

b} in vector form, are situated at the plate's four edges. The domain points are the set of all remaining interior points and are denoted by {

d}. After substituting the boundary conditions into the governing equations, the following equation is obtained by dividing and rearranging the matrix according to the above division:

By eliminating the non–zero element

, equation (26) can be shown in the following way:

where

. The fundamental frequencies and amplitudes of the plate can be determined by solving equation (27) using the standard eigenvalue matrix.

2.5 Boundary Conditions

For the four edges—clamped, simply supported, and free—CCCC, SSSS, and FFFF can be utilized as the boundary conditions. Hybrid boundary conditions such as CSCS, CFCF, and CFFF were also used in this study. The following are the boundary condition phrases for each edge:

Substituting equation (12) into equation (30), gives the following:

Equations (28)–(30) can be combined to express the boundary conditions for a sandwich plate with hybrid boundary conditions.

After applying the DQM to discretize the above equations, the following equations can be got:

In this way, the specific matrix in equation (25) can be calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation and Convergence Studies

The validation and convergence investigations of the free vibration for VSCL sandwich plates using the DQM solution method are provided in this part. By comparing the results with other FSDT-based numerical solution solutions for currently available CSCL sandwich plates, the quantity of DQM grid points was ascertained. In the study, material I and material III in

Table 1. were used as the skins and the core, respectively.

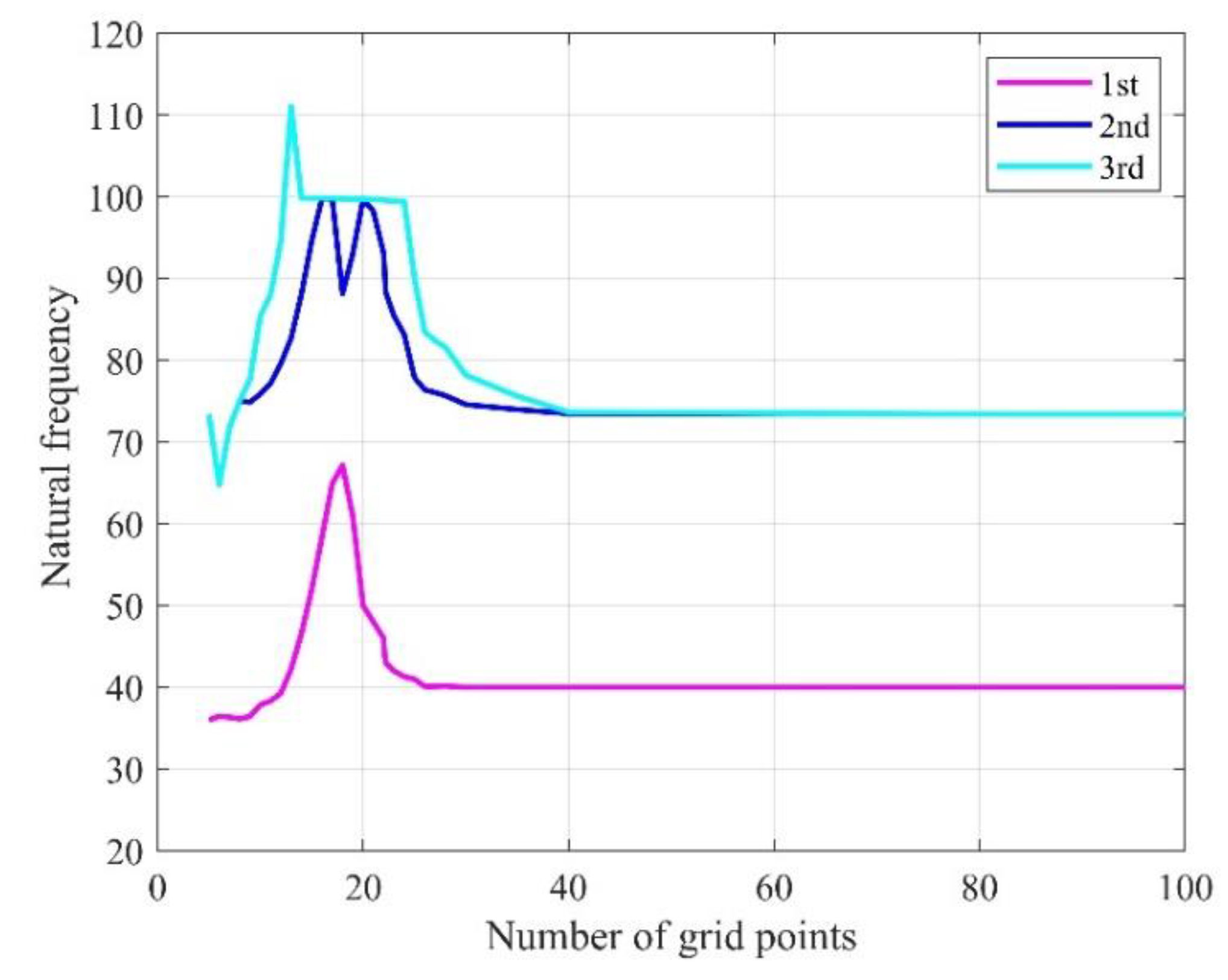

First, the quantity of grid points at which the natural frequency generated by this method might be stabilized is determined by selecting an anti–symmetric sandwich plate of [0/90/core/0/90] with the geometric parameters

a/b = 0.5,

a/h = 10, and

tc/tf = 10. With an increasing number of grid points,

Figure 3. displays the pattern of the sandwich plate's first three orders of natural frequency. It is evident that when the quantity of grid points rises, the frequency values' computation results typically yield steady results. It shows that the application of DQM to the problem in this study can provide convergent results.

The quantity of grid points in this investigation was selected as

when DQM was used. For comparison, various aspect ratios (

) and (

) were chosen, as shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

As is evident from Tables 2–3, the results of the DQM used in this study to calculate the composite sandwich plates are only slightly different from those of the references, indicating that the mechanical model and calculation method used in this study are correct. At the same time, only 38 × 38 grid points are used in this study, which enables high accuracy of the results. Regarding computation effectiveness, the current paper's approach is better.

3.2. Parameter Study

A parameter research of the free vibrations was carried out to enhance the vibratory behavior of the VSCL sandwich plates. The fundamental frequency of the sandwich plate was examined in relation to the fiber orientation angles, boundary conditions, number of layers, and core/skin thickness.

3.2.1. Fiber Orientation Angles

First, the effect of changes in the start and termination angles was investigated. In this section, a VSCL sandwich plate with four symmetric skins

is chosen as the object of investigation. Materials II in Table 1. were used as the face sheets and materials IV and VI in Table 1. were used as the two kinds of core, respectively. Among the two selected core materials, material VI is an aluminum honeycomb core.[42] The plate thickness

h = 0.1

a, the core thickness

, and each single layer were taken as

. For comparison, the first and second dimensionless natural frequencies

were chosen. The fiber orientation angles

and

are both varied from 0° to 90°. Both CCCC and SSSS boundary conditions were considered, and the results are listed in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, respectively.

Tables 4–7 reveal that the majority of fundamental frequencies typically rise with the increase of fiber orientation angle. A corresponding decrease in the natural frequency was observed when the fiber orientation angle reached the maximum value. Therefore, sandwich plates can be made stiffer by using curvilinear fibers with low curvatures. In certain instances, industry designers must alter the fundamental frequency to a greater or lesser value for the purpose of preventing resonance. This can be accomplished by using VSCL sandwich plates without having to change the size of the plate or constituent materials. The reason for this is that the natural frequency is sensitive to changes in fiber orientation in each layer.

3.2.2. Boundary Conditions

In order to investigate the first two fundamental frequencies at various fiber orientation angles, five boundary conditions were taken into consideration in this section. A comparative study between the CSCL and VSCL sandwich plates was also conducted. In this section, sandwich plates with single-ply skins

are chosen, and the fiber orientation angles

and

are varied from 0° to 70°. Materials II and V from Table 1. were used as the skins and the core, respectively. The plate thickness

, core thickness

, and each single layer were taken as

.

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12 present the results with five boundary conditions: CCCC, SSSS, CSCS, CFCF, and CFFF. The natural frequencies of the CSCL sandwich plates are bolded in these tables.

Tables 8–12 demonstrate that for the SSSS, CSCS, CFCF, and CFFF boundary conditions, the VSCL sandwich plate's natural frequency tends to grow when the ending angle increases, the situation is reversed for the CCCC. For CFCF and CFFF, the VSCL sandwich plate's fundamental frequency increased by 15.175% and 32.708%, respectively, when the ending angle was increased from 0° to 70°. Nonetheless, under SSSS and CSCS boundary circumstances, the VSCL sandwich plate's fundamental frequency dropped by 2.228% and 1.128%, respectively, when the endings angle is increased from 50° to 70°. According to the findings, the fundamental frequencies of the VSCL sandwich plates are affected by the fiber orientation angle as the curvilinear fiber’s curvature increases.

3.2.3. Number of Layers

This section looks into how the amount of layers affects sandwich plate’s fundamental frequency. Based on sandwich plates with single-ply skins

, the quantity of layers was raised, and sandwich plates with two-layer anti-symmetric skins

were selected. The thicknesses and mechanical properties were selected to match those mentioned in the preceding section. The results with five boundary conditions are listed in

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14,

Table 15,

Table 16 and

Table 17.

From Tables 13–17, it is clear that when increases, the fundamental frequency shifts. In the CCCC boundary condition, when rises from 0° to 10° and from 10° to 90°, the natural frequency falls and increases, respectively. Under the SSSS and CSCS boundary conditions, the natural frequency increases when increases from 0° to 60° and decreases from 60° to 90°. When the number of layers grows, the fundamental frequency for sandwich plates with anti-symmetric two-layer skins often rises as well.

When CCCC and CSCS were met, the fundamental frequencies of the VSCL sandwich plates were found to be greater than those of the CSCL sandwich plates. This was determined by comparing the fundamental frequencies of the two sandwich plates. Sandwich plate vibration properties can be considerably altered by the application of curvilinear fiber. For instance, when comparing to under the boundary conditions of SSSS and CCCC, the fundamental frequency of CSCL plates is zero, but the fundamental frequencies of VSCL plates are changed when increases from 40° to 50°.

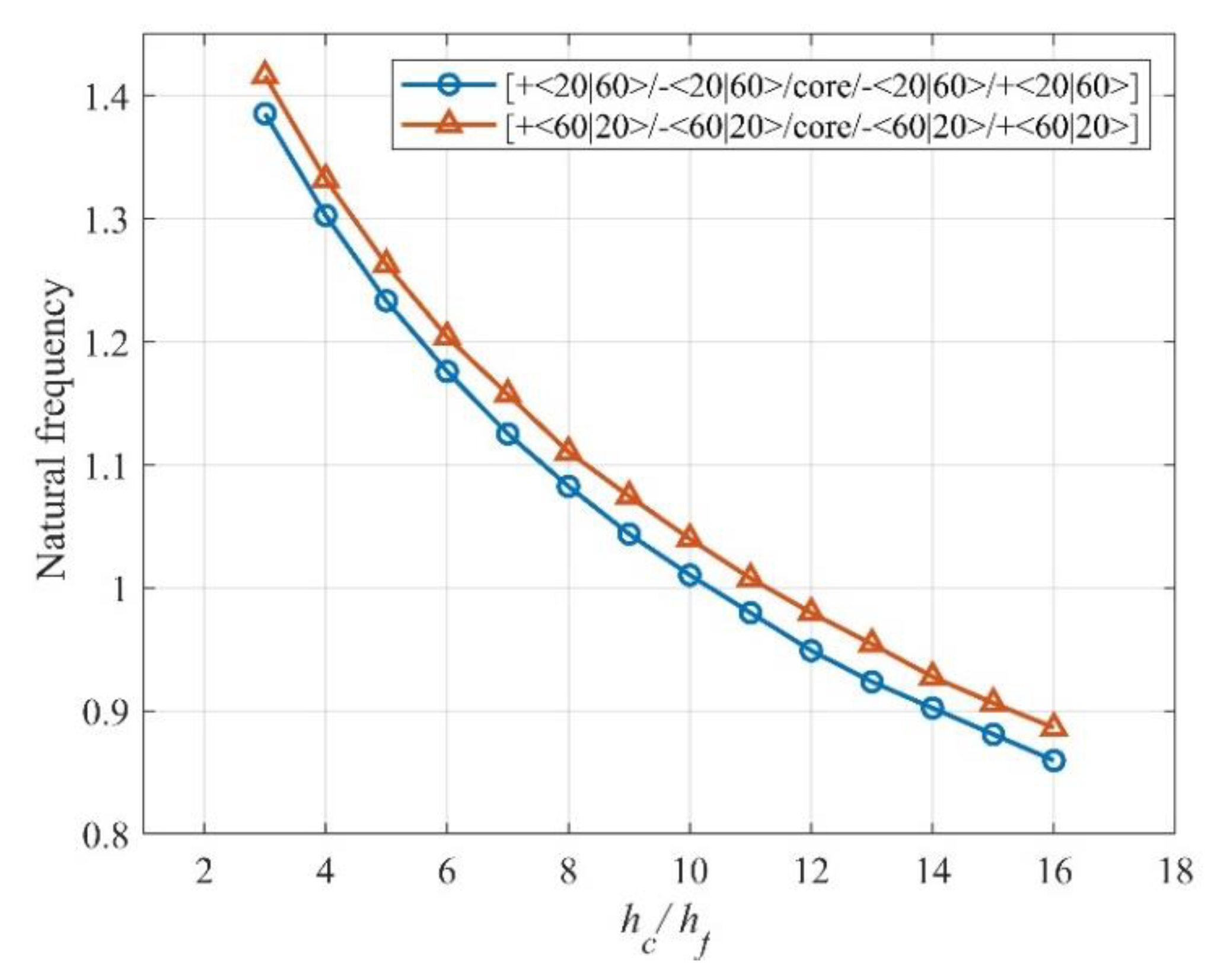

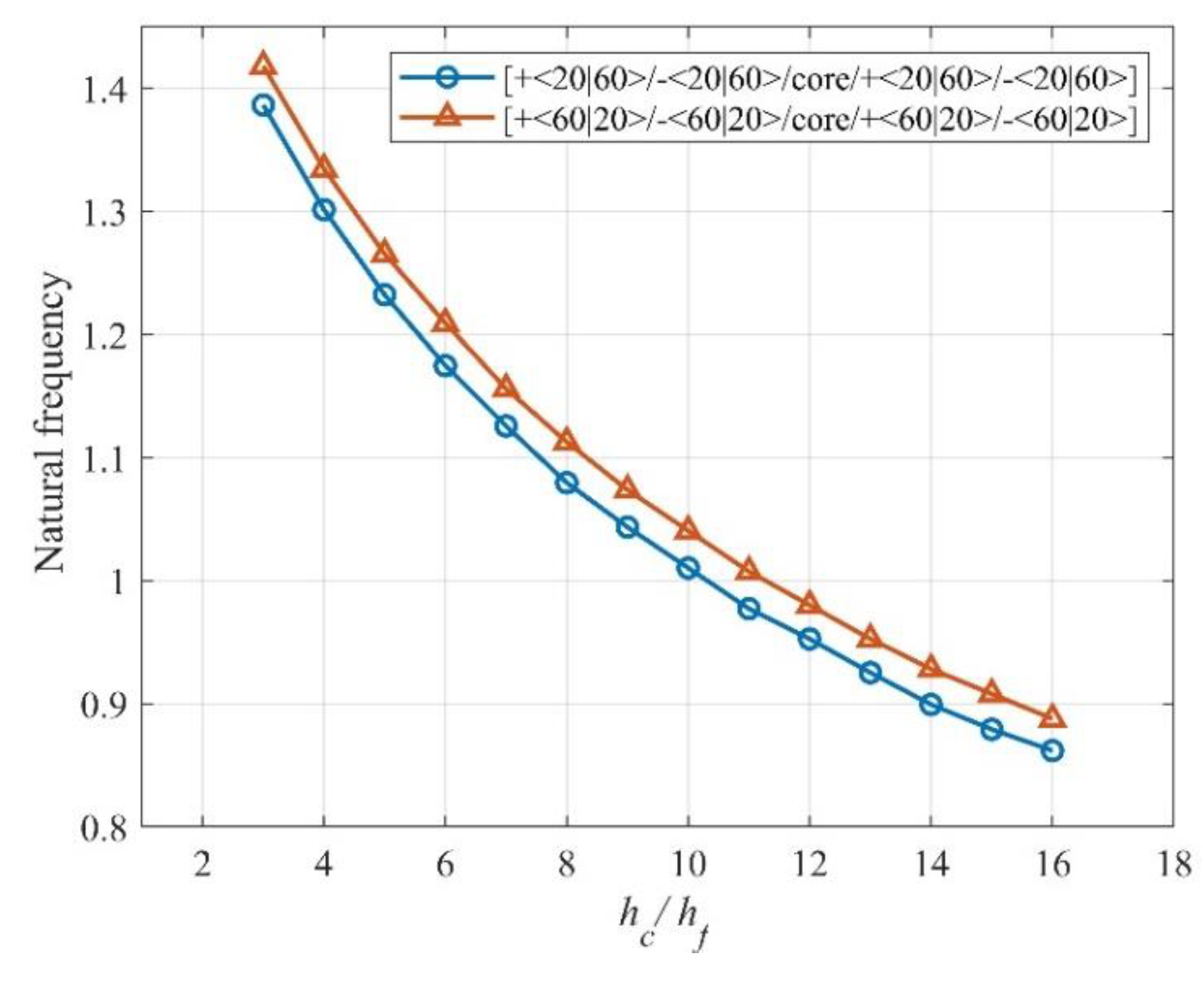

3.2.4. Core/Skin Thickness

Sandwich plates that are symmetric and anti-symmetric are used in this part to examine the connection between the fundamental frequency and the ratio of the core to skin. The skins and core were selected with the same thickness and mechanical characteristics as those in the preceding section, except for the plate thickness

. The core thickness/face sheet thickness,

hc /

hf, varied from 3 to 16 as variation parameters. The fundamental frequencies of

and

are chosen to study the variation rule and CSCS boundary condition is chosen. Changes in fundamental frequency with core/skin thickness ratio

are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

As shown in Figures 4 and 5, the VSCL sandwich plates exhibit the highest natural frequency at the lowest core/skin thickness ratio. The average decline in fundamental frequency from the greatest to the lowest point was 67%.

The findings of the aforementioned parametric study suggest that VSCL sandwich plates hold promise for aircraft panel design applications. By manipulating the starting and ending angles along with the curvature of the fiber reference path, these plates can potentially exhibit reduced lateral deformation, increased stiffness, and higher natural frequencies. Moreover, lower structural mass can be achieved under certain mechanical and environmental loading circumstances by using VSCL sandwich plates.

4. Conclusions

This study used FSDT in conjunction with DQM to examine the free vibration of sandwich plates with curvilinear fiber variable stiffness skins. In this study, the x-coordinate was supposed to fluctuate linearly with the fiber orientation angle. Compared with other numerical solution methods, the DQM is computationally inexpensive, converges quickly, and it is capable of precisely forecasting sandwich plate fundamental frequencies. The reduction or increase in the natural frequency when using VSCL face sheets was investigated and compared with that of CSCL face sheets. The impacts of fiber orientation angles, boundary conditions, number of layers, and core/skin thickness were investigated parametrically. Notably, the integration of higher-order theory and layer theory can enhance the accuracy of sandwich plate analysis, particularly when investigating thick plates. The computations used in this study allow for the following deductions.

1. In the vast majority of cases, as the fiber orientation angle increases, the fundamental frequency rises as well. The use of curvilinear fibers leads to VSCL sandwich plates with lower lateral deformations and higher natural frequencies.

2. The sandwich plate's natural frequency was impacted by the fiber orientation angle as the curvilinear fibers' curvature grew. The larger the angle of the center fiber was, the more rigid the curvilinear fiber became. The plate's rigidity can be raised by using low-curvature curvilinear fibers.

3. With an increase in layers came a rise in the sandwich plate's fundamental frequency. This also indicates that the fundamental frequency increases with rising plate thickness.

4. The VSCL sandwich plates exhibited greater natural frequencies in comparison to the CSCL sandwich plates when subjected to the CCCC and CSCS boundary conditions. As boundary restrictions get tighter, the frequency rises. Due to their increased ability to adapt to complex boundary circumstances, curvilinear fibers have higher fundamental frequencies than parallel fibers.

5. The frequency response was strongly impacted by the ratio of skin to core thickness. The natural frequency of the sandwich plate reached its maximum value at the lowest core–to-skin thickness ratio. The effect of adding more layers was in line with this trend.

The precise insights obtained from this study guide researchers seeking viable solutions and can serve as a foundation for further exploration into panel flutter in VSCL sandwich plates.

Author Contributions

Zhenyu Zhou: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing. Yi Liu: Conceptualization; Investigation; Supervision; Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Any continuously differentiable function

is taken on the interval

for a one-dimensional issue, divided by the interval

, and set

N mutually non–overlapping nodes,

, and according to the theory of interpolation,

where

is called the interpolating trial function.

Determine the

kth order derivative with respect to

x on both sides of equation (35) and substitute

to obtain the

kth order derivative of the function at node

xi

When

,

,

, equation (36) can be written as

where

is the weighting coefficient of the

kth–order

derivative of the function

. Equation (37) is the differential quadrature formula

for a one–dimensional function, and there is a recurrence relationship

between the weighting coefficients.

The formula demonstrates that the distribution, number

of sampling points, and order of the derivatives are the only factors that

affect the weighting coefficients. As such, the DQM's numerical accuracy is

typically highly sensitive to the partitioning of the grid points inside a

given domain. The Chebyshev–Gauss–Lobatto point distribution was chosen in the

form of grid spacing[43]

Extending to the two–dimensional problem, take any

continuously differentiable function

in a two–dimensional region and divide the solution

domain by a rectangular mesh. In both directions, the total amount of grid

points is denoted by

and

, respectively. To make the calculation simpler, the

same number of grid points are often utilized in both directions, i.e.,

.

Equation (40) is the differential quadrature formula

for a two–dimensional function, where and satisfy the

recurrence

relation.

References

-

Vinson J R The Behavior of Sandwich Structures of Isotropic and Composite Materials; Technomic: Lancaster, PA, 1999.

- Carrera, E.; Brischetto, S. A Survey with Numerical Assessment of Classical and Refined Theories for the Analysis of Sandwich Plates. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2009, 62, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, W.S.; Noor, A.K. Assessment of Computational Models for Sandwich Panels and Shells. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1996, 49, 155–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.K.; Burton, W.S.; Bert, C.W. Computational Models for Sandwich Panels and Shells. Appl. Mech. Rev. 1996, 49, 155–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osa-uwagboe, N.; Silberschimdt Vadim, V.; Aremi, A.; Demirci, E. Mechanical Behaviour of Fabric-Reinforced Plastic Sandwich Structures: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2023, 25, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, G.S.; von Klemperer, C.J.; Rowland, B.K.; Nurick, G.N. The Response of Sandwich Structures with Composite Face Sheets and Polymer Foam Cores to Air-Blast Loading: Preliminary Experiments. Eng. Struct. 2012, 36, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriruk, A.; Jack Weitsman, Y.; Penumadu, D. Polymeric Foams and Sandwich Composites: Material Properties, Environmental Effects, and Shear-Lag Modeling. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson J R Sandwich Structures. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2001, 54, 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Yaman, M.; Önal, T. Investigation of Dynamic Properties of Natural Material-Based Sandwich Composites: Experimental Test and Numerical Simulation. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2016, 18, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setoodeh, S.; Abdalla, M.M.; IJsselmuiden, S.T.; Gürdal, Z. Design of Variable-Stiffness Composite Panels for Maximum Buckling Load. Compos. Struct. 2009, 87, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, H.; Ribeiro, P. Aeroelasticity of Composite Plates with Curvilinear Fibres in Supersonic Flow. Compos. Struct. 2018, 194, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.; Ribeiro, P. A Layerwise P-Version Finite Element Formulation for Free Vibration Analysis of Thick Composite Laminates with Curvilinear Fibres. Compos. Struct. 2015, 120, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.M.; Ribeiro, P.; Dias Rodrigues, J.; Akhavan, H. Modal Analysis of a Variable Stiffness Composite Laminated Plate with Diverse Boundary Conditions: Experiments and Modelling. Compos. Struct. 2020, 239, 111974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, T.; Swaminathan, K. Analytical Solutions for Free Vibration of Laminated Composite and Sandwich Plates Based on a Higher-Order Refined Theory. Compos. Struct. 2001, 53, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.X.; Dawe, D.J. Free Vibration of Sandwich Plates with Laminated Faces. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2002, 54, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantari, J.L.; Ore, M. Free Vibration of Single and Sandwich Laminated Composite Plates by Using a Simplified FSDT. Compos. Struct. 2015, 132, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürdal, Z.; Olmedo, R. In-Plane Response of Laminates with Spatially Varying Fiber Orientations: Variable Stiffness Concept. AIAA J. 1993, 31, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.S.; Gürdal, Z.; Camanho, P.P. Variable-Stiffness Composite Panels: Buckling and First-Ply Failure Improvements over Straight-Fibre Laminates. Comput. Struct. 2008, 86, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, A.; Ijsselmuiden, S.T.; Abdalla, M.M.; Gürdal, Z. Design of Variable Stiffness Panels for Maximum Strength Using Lamination Parameters. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, H.; Ribeiro, P. Natural Modes of Vibration of Variable Stiffness Composite Laminates with Curvilinear Fibers. Compos. Struct. 2011, 93, 3040–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houmat, A. Three-Dimensional Solutions for Free Vibration of Variable Stiffness Laminated Sandwich Plates with Curvilinear Fibers. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2020, 22, 896–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachemi, M. Layer-Wise Solutions for Variable Stiffness Composite Laminated Sandwich Plate Using Curvilinear Fibers. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2022, 29, 5460–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachemi, M. Vibration Analysis of Variable Stiffness Laminated Composite Sandwich Plates. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2020, 27, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civalek, Ö. Free Vibration Analysis of Symmetrically Laminated Composite Plates with First-Order Shear Deformation Theory (FSDT) by Discrete Singular Convolution Method. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2008, 44, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R.; Casti, J. Differential Quadrature and Long-Term Integration. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1971, 34, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.L. Differential Quadrature Element Method for Buckling Analysis of Rectangular Mindlin Plates Having Discontinuities. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2001, 38, 2305–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Han, J.B.; Xiao, Z.M.; Du, H. Differential Quadrature Method for Mindlin Plates on Winkler Foundations. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1996, 38, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Huang, Y.Q.; Reddy, J.N. Vibration Analysis of Symmetrically Laminated Plates Based on FSDT Using the Moving Least Squares Differential Quadrature Method. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2003, 192, 2203–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Chen, Z.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X. Free Vibration of Functionally Graded Sandwich Plates Based on Nth-Order Shear Deformation Theory via Differential Quadrature Method. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2020, 22, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Pradyumna, S. A New C0 Higher-Order Layerwise Finite Element Formulation for the Analysis of Laminated and Sandwich Plates. Compos. Struct. 2015, 131, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushparaj, P.; Suresha, B. Free Vibration Analysis of Laminated Composite Plates Using Finite Element Method. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2016, 24, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarbi, M.O.; Tati, A.; Ounis, H.; Khechai, A. On the Free Vibration Analysis of Laminated Composite and Sandwich Plates: A Layerwise Finite Element Formulation. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2017, 14, 2265–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrate, S. Functionally Graded Plates Behave like Homogeneous Plates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2008, 39, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Nazemnezhad, R.; Hosseini-Hashemi, S. Natural Frequency Analysis of Functionally Graded Rectangular Nanoplates with Different Boundary Conditions via an Analytical Method. Meccanica 2015, 50, 2391–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.N. Mechanics of Laminated Composite Plates and Shells; Theory and Analysis.; FL: CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mindlin, R.D. Influence of Rotatory Inertia and Shear on Flexural Motions of Isotropic, Elastic Plates. J. Appl. Mech. 1951, 18, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, V.; Bert, C.W. On the Choice of Shear Correction Factor in Sandwich Structures. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2002, 4, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Yao, Q.; Yeo, K.S.; Zhu, Y.D. Numerical Analysis of Flow and Thermal Fields in Arbitrary Eccentric Annulus by Differential Quadrature Method. Heat Mass Transf. und Stoffuebertragung 2002, 38, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Ding, H.; Yeo, K.S. Solution of Partial Differential Equations by a Global Radial Basis Function-Based Differential Quadrature Method. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2004, 28, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozgar, M.R.; Shahverdi, H. Analysis of Nonlinear Fully Intrinsic Equations of Geometrically Exact Beams Using Generalized Differential Quadrature Method. Acta Mech. 2016, 227, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, J.M.; Pagano, N.J. Shear Deformation in Heterogeneous Anisotropic Plates. J. Compos. Mater. 1970, 37, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, K.; Afshari, H.; Aboutalebi, F.H. Vibration and Flutter Analyses of Cantilever Trapezoidal Honeycomb Sandwich Plates. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2019, 21, 2887–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C. Differential Quadrature and Its Application in Engineering; SpringerVerlag: London, 2000; ISBN 9783319069197. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Geometric configuration and Cartesian coordinate system of the sandwich plate.

Figure 1.

Geometric configuration and Cartesian coordinate system of the sandwich plate.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the fiber orientation angles.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the fiber orientation angles.

Figure 3.

First three orders of natural frequency with the increase of grid points.

Figure 3.

First three orders of natural frequency with the increase of grid points.

Figure 4.

Natural frequency to core/skin ratio hc/hf effect of the symmetric VSCL sandwich plate [+<20|60>/-<20|60>/core/-<20|60>/+<20|60>] and [+<60|20>/-<60|20>/core/-<60|20>/+<60|20>], CSCS.

Figure 4.

Natural frequency to core/skin ratio hc/hf effect of the symmetric VSCL sandwich plate [+<20|60>/-<20|60>/core/-<20|60>/+<20|60>] and [+<60|20>/-<60|20>/core/-<60|20>/+<60|20>], CSCS.

Figure 5.

Natural frequency to core/skin ratio hc/hf effect of the anti-symmetric VSCL sandwich plate [+<20|60>/-<20|60>/core/+<20|60>/-<20|60>] and [+<60|20>/-<60|20>/core/+<60|20>/-<60|20>], CSCS.

Figure 5.

Natural frequency to core/skin ratio hc/hf effect of the anti-symmetric VSCL sandwich plate [+<20|60>/-<20|60>/core/+<20|60>/-<20|60>] and [+<60|20>/-<60|20>/core/+<60|20>/-<60|20>], CSCS.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of the materials.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of the materials.

| |

Material |

E1(GPa) |

E2(GPa) |

G12(GPa) |

G13(GPa) |

G23(GPa) |

ν12

|

ρ(kg/m3) |

| Face sheets |

I |

131 |

10.34 |

6.895 |

6.205 |

6.895 |

0.22 |

1627 |

| |

II |

138 |

8.96 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

0.30 |

1 |

| Core |

III |

6.89×10-3

|

6.89×10-3

|

3.45×10-3

|

3.45×10-3

|

3.45×10-3

|

0.30 |

97 |

| |

IV |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.016 |

0.016 |

0.06 |

0.25 |

1 |

| |

V |

0.104 |

0.104 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.32 |

130 |

| |

VI |

0.057 |

0.328 |

0.056 |

1.115 |

2.2×10-3

|

0.406 |

335.762 |

Table 2.

The dimensionless fundamental frequency of anti–symmetric sandwich plate (a / b = 1, tc / tf = 10).

Table 2.

The dimensionless fundamental frequency of anti–symmetric sandwich plate (a / b = 1, tc / tf = 10).

| a/h |

Methods |

|

|

|

| Ref[14] |

Ref [16] |

Ref [41] |

Present |

| 2 |

5.2017 |

5.6114 |

5.6114 |

5.3246 |

| 4 |

9.0312 |

9.5447 |

9.5447 |

9.2547 |

| 10 |

13.8694 |

14.1454 |

14.1454 |

14.2559 |

| 20 |

15.5295 |

15.6124 |

15.6124 |

15.6742 |

| 30 |

15.9155 |

15.9438 |

15.9438 |

15.8596 |

| 40 |

16.0577 |

16.0655 |

16.0655 |

16.0028 |

| 50 |

16.1264 |

16.1229 |

16.1229 |

16.1256 |

| 60 |

16.1612 |

16.1544 |

16.1544 |

16.1698 |

| 70 |

16.1845 |

16.1735 |

16.1735 |

16.1752 |

| 80 |

16.1991 |

16.1859 |

16.1859 |

16.1872 |

| 90 |

16.2077 |

16.1944 |

16.1944 |

16.1966 |

| 100 |

16.2175 |

16.2006 |

16.2006 |

16.2369 |

Table 3.

The dimensionless fundamental frequency of anti–symmetric sandwich plate (tc / tf = 10, a / h = 10).

Table 3.

The dimensionless fundamental frequency of anti–symmetric sandwich plate (tc / tf = 10, a / h = 10).

| a/b |

Methods |

|

|

|

| Ref [14] |

Ref [16] |

Ref [41] |

Present |

| 0.5 |

39.4840 |

40.3559 |

40.1511 |

40.2645 |

| 1 |

13.8694 |

14.1454 |

14.1454 |

14.2559 |

| 1.5 |

9.4910 |

9.8376 |

9.7826 |

9.3789 |

| 2 |

10.1655 |

8.0759 |

7.9863 |

8.1679 |

| 2.5 |

6.5059 |

6.9340 |

6.8463 |

6.9473 |

| 3 |

5.6588 |

6.0727 |

5.9993 |

6.0227 |

| 5 |

3.6841 |

3.9929 |

3.9658 |

4.0763 |

Table 4.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material IV, CCCC.

Table 4.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material IV, CCCC.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

10 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

90 |

| 1 |

0 |

6.9527 |

6.9507 |

6.9469 |

6.9353 |

6.9234 |

6.9187 |

| |

10 |

6.9567 |

6.9714 |

6.9709 |

6.9563 |

6.9507 |

6.9457 |

| |

30 |

7.0264 |

7.0402 |

7.0410 |

7.0154 |

6.9912 |

6.9542 |

| |

50 |

9.3974 |

7.1262 |

7.1094 |

7.0565 |

7.0051 |

6.9721 |

| |

70 |

7.1675 |

7.1753 |

7.1462 |

7.0852 |

7.0095 |

6.9871 |

| |

90 |

7.0478 |

7.0756 |

7.0947 |

7.0678 |

7.0145 |

6.9923 |

| 2 |

0 |

8.9047 |

8.9219 |

8.9851 |

9.0576 |

9.1216 |

9.1347 |

| |

10 |

8.9209 |

8.9581 |

9.0495 |

9.1234 |

9.1876 |

9.2137 |

| |

30 |

9.0898 |

9.1422 |

9.2457 |

9.3088 |

9.2852 |

9.2943 |

| |

50 |

9.3519 |

9.4053 |

9.4747 |

9.3883 |

9.2260 |

9.2127 |

| |

70 |

9.5884 |

9.6095 |

9.4978 |

9.2751 |

9.0877 |

9.0622 |

| |

90 |

9.9746 |

9.9823 |

9.9946 |

9.8496 |

9.0347 |

9.0014 |

Table 5.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material IV, SSSS.

Table 5.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material IV, SSSS.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

10 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

90 |

| 1 |

0 |

6.3067 |

6.3409 |

6.4822 |

6.5774 |

6.5977 |

6.6124 |

| |

10 |

6.3272 |

6.3885 |

6.5296 |

6.6102 |

6.6269 |

6.6314 |

| |

30 |

6.4312 |

6.5006 |

6.6158 |

6.6561 |

6.6488 |

6.6572 |

| |

50 |

6.5537 |

6.5946 |

6.6688 |

6.6735 |

6.6101 |

6.6016 |

| |

70 |

6.5528 |

6.5856 |

6.6296 |

6.6106 |

6.5174 |

6.4174 |

| |

90 |

6.4736 |

6.5469 |

6.6026 |

6.5863 |

6.4936 |

6.4247 |

| 2 |

0 |

8.3372 |

8.3594 |

8.4891 |

8.6027 |

8.6967 |

8.7246 |

| |

10 |

8.3577 |

8.4062 |

8.5464 |

8.6607 |

8.7622 |

8.8451 |

| |

30 |

8.5293 |

8.601 |

8.7364 |

8.8492 |

8.8618 |

8.8924 |

| |

50 |

8.7891 |

8.8465 |

8.9353 |

8.9003 |

8.7389 |

8.7137 |

| |

70 |

8.9093 |

8.9362 |

8.8803 |

8.7339 |

8.5645 |

8.4547 |

| |

90 |

9.3178 |

9.3267 |

9.3756 |

9.3149 |

8.9146 |

8.8472 |

Table 6.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material VI, CCCC.

Table 6.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material VI, CCCC.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

10 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

90 |

| 1 |

0 |

11.0793 |

11.0781 |

11.0697 |

11.0648 |

11.0453 |

11.0357 |

| |

10 |

11.0771 |

11.0953 |

11.0914 |

11.0766 |

11.0756 |

11.0714 |

| |

30 |

11.1549 |

11.1668 |

11.1625 |

11.1398 |

11.1157 |

11.1047 |

| |

50 |

13.5267 |

11.2479 |

11.2376 |

11.1803 |

11.1316 |

11.1243 |

| |

70 |

11.2943 |

11.1749 |

11.3022 |

11.2033 |

11.2733 |

11.3478 |

| |

90 |

11.2223 |

11.2055 |

11.1914 |

11.1375 |

11.1398 |

11.2047 |

| 2 |

0 |

36.0282 |

36.0495 |

36.1104 |

36.1777 |

36.2433 |

36.2647 |

| |

10 |

36.0492 |

36.0856 |

36.1773 |

36.2468 |

36.3136 |

36.3224 |

| |

30 |

36.2157 |

36.266 |

36.3757 |

36.4304 |

36.4078 |

36.3924 |

| |

50 |

36.4774 |

36.5317 |

36.5965 |

36.5162 |

36.3525 |

36.2176 |

| |

70 |

36.7176 |

37.0954 |

36.7352 |

37.1054 |

36.6247 |

36.7341 |

| |

90 |

37.1175 |

36.3956 |

36.9743 |

36.2134 |

36.1622 |

36.1527 |

Table 7.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material VI, SSSS.

Table 7.

First and second natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, material II and material VI, SSSS.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

10 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

90 |

| 1 |

0 |

10.4352 |

10.4633 |

10.6112 |

10.7011 |

10.7187 |

10.7231 |

| |

10 |

10.4534 |

10.5097 |

10.6595 |

10.7313 |

10.7482 |

10.7513 |

| |

30 |

10.5547 |

10.6224 |

10.7407 |

10.7839 |

10.7782 |

10.7924 |

| |

50 |

10.6788 |

10.7174 |

10.7937 |

10.7974 |

10.7397 |

10.8043 |

| |

70 |

10.6768 |

10.7098 |

10.7523 |

10.7334 |

10.6432 |

10.6243 |

| |

90 |

10.5944 |

10.6674 |

10.7316 |

10.7103 |

10.6142 |

10.5378 |

| 2 |

0 |

35.4595 |

35.4859 |

35.6165 |

35.7305 |

35.8212 |

35.8934 |

| |

10 |

35.4812 |

35.5335 |

35.6683 |

35.7815 |

35.8853 |

35.9136 |

| |

30 |

35.6575 |

35.7275 |

35.8633 |

35.9785 |

35.9869 |

36.0034 |

| |

50 |

35.9093 |

35.9717 |

36.0571 |

36.0281 |

35.8644 |

35.9436 |

| |

70 |

36.0297 |

36.0617 |

36.0074 |

35.8588 |

35.6927 |

35.6219 |

| |

90 |

36.4395 |

36.4497 |

36.5019 |

36.4393 |

36.0425 |

35.9547 |

Table 8.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CCCC.

Table 8.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CCCC.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

| 1 |

0 |

39.6473 |

39.6247 |

39.6030 |

39.5948 |

| |

30 |

39.6313 |

39.3563 |

39.3423 |

39.3246 |

| |

50 |

39.5363 |

39.3478 |

39.2798 |

39.2636 |

| |

70 |

39.6216 |

39.5347 |

39.4298 |

39.4889 |

| 2 |

0 |

58.9473 |

59.7766 |

60.8274 |

61.2839 |

| |

30 |

58.8647 |

59.5879 |

59.3649 |

59.3278 |

| |

50 |

58.8897 |

59.8846 |

59.8808 |

59.2867 |

| |

70 |

58.9146 |

59.9078 |

59.2678 |

59.2475 |

Table 9.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, SSSS.

Table 9.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, SSSS.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

| 1 |

0 |

34.2142 |

35.0553 |

35.9351 |

35.1028 |

| |

30 |

34.1379 |

35.6275 |

35.9874 |

35.1498 |

| |

50 |

34.2378 |

35.4367 |

36.0994 |

35.7698 |

| |

70 |

34.5134 |

35.4793 |

35.8569 |

34.9646 |

| 2 |

0 |

54.0617 |

55.2244 |

56.8894 |

58.1559 |

| |

30 |

54.0024 |

56.2285 |

56.9712 |

57.1236 |

| |

50 |

54.3478 |

56.4783 |

57.0087 |

56.2863 |

| |

70 |

54.7369 |

56.8923 |

55.8963 |

55.1944 |

Table 10.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CSCS.

Table 10.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CSCS.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

| 1 |

0 |

37.5031 |

37.8185 |

38.4084 |

37.9751 |

| |

30 |

37.4231 |

37.3931 |

37.3647 |

37.2168 |

| |

50 |

37.3895 |

37.3678 |

37.3476 |

37.1678 |

| |

70 |

37.2336 |

37.1436 |

37.0247 |

36.8877 |

| 2 |

0 |

57.8964 |

58.7024 |

60.1376 |

58.7718 |

| |

30 |

57.6423 |

58.3142 |

59.1235 |

57.9871 |

| |

50 |

57.1278 |

58.1756 |

57.8934 |

57.9923 |

| |

70 |

56.5671 |

56.2726 |

56.3179 |

56.1968 |

Table 11.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CFCF.

Table 11.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CFCF.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

| 1 |

0 |

25.3726 |

25.8954 |

27.2084 |

29.2269 |

| |

30 |

25.7569 |

26.5778 |

27.5736 |

29.7863 |

| |

50 |

26.7126 |

27.1244 |

28.5534 |

29.9713 |

| |

70 |

28.5698 |

28.9347 |

29.5431 |

30.5653 |

| 2 |

0 |

31.2536 |

31.9102 |

33.0809 |

34.7477 |

| |

30 |

31.8534 |

33.8788 |

34.1746 |

34.3478 |

| |

50 |

32.4782 |

34.2378 |

34.3559 |

34.6023 |

| |

70 |

33.4789 |

34.2478 |

34.4823 |

34.6283 |

Table 12.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CFFF.

Table 12.

The first two natural frequencies of the VSCL sandwich square plate, CFFF.

| |

|

Θ1

|

|

|

|

| Mode |

Θ0

|

0 |

30 |

50 |

70 |

| 1 |

0 |

8.5298 |

8.7551 |

9.4121 |

11.3263 |

| |

30 |

9.1572 |

9.2474 |

10.0278 |

11.5621 |

| |

50 |

10.5317 |

10.6781 |

10.8187 |

12.4623 |

| |

70 |

12.2578 |

12.6712 |

12.9152 |

13.2824 |

| 2 |

0 |

16.6078 |

17.0308 |

17.8546 |

19.3829 |

| |

30 |

17.8254 |

18.3633 |

18.9512 |

19.4782 |

| |

50 |

18.2756 |

18.4278 |

19.6162 |

19.5172 |

| |

70 |

18.5627 |

18.6785 |

18.9245 |

19.1076 |

Table 13.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CCCC.

Table 13.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CCCC.

| |

|

Mode |

| Face sheets |

±<Θ0|Θ1> |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| CSCL |

<0|0> |

39.6465 |

58.9464 |

65.5382 |

79.5688 |

| |

±<10|10> |

39.7633 |

59.4381 |

65.2119 |

79.8171 |

| |

±<20|20> |

40.2143 |

60.7233 |

64.8844 |

80.4201 |

| |

±<30|30> |

40.7764 |

62.2097 |

64.6121 |

80.9608 |

| |

±<40|40> |

41.1206 |

63.3955 |

64.1663 |

81.2667 |

| |

±<50|50> |

41.1286 |

63.3893 |

64.1589 |

81.2711 |

| |

±<60|60> |

40.7783 |

62.2134 |

64.6091 |

80.9550 |

| |

±<70|70> |

40.2143 |

60.7233 |

64.8844 |

80.4201 |

| |

±<80|80> |

39.7633 |

59.4381 |

65.2119 |

79.8171 |

| |

±<90|90> |

39.6465 |

58.9464 |

65.5382 |

79.5688 |

| VSCL |

<0|0> |

39.6465 |

58.9464 |

65.5382 |

79.5688 |

| |

±<0|10> |

39.5995 |

59.0649 |

65.1865 |

79.4612 |

| |

±<0|20> |

39.6158 |

59.4321 |

64.7485 |

79.4525 |

| |

±<0|30> |

39.7611 |

59.9688 |

64.4655 |

79.6308 |

| |

±<0|40> |

39.9594 |

60.5895 |

64.2308 |

79.8756 |

| |

±<0|50> |

40.1837 |

61.2613 |

63.9596 |

80.1436 |

| |

±<0|60> |

40.4192 |

62.0193 |

63.5153 |

80.4052 |

| |

±<0|70> |

40.5387 |

62.6344 |

62.9034 |

80.5004 |

| |

±<0|80> |

40.6371 |

62.9314 |

63.5687 |

80.6479 |

| |

±<0|90> |

40.9426 |

63.2478 |

63.9742 |

80.9412 |

Table 14.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, SSSS.

Table 14.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, SSSS.

| |

|

Mode |

| Face sheets |

±<Θ0|Θ1> |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| CSCL |

<0|0> |

34.2107 |

54.0555 |

61.2997 |

74.7633 |

| |

±<10|10> |

35.0924 |

55.0091 |

61.6123 |

75.6645 |

| |

±<20|20> |

36.6785 |

56.8276 |

62.1063 |

77.1309 |

| |

±<30|30> |

37.9304 |

58.8233 |

62.2413 |

78.1959 |

| |

±<40|40> |

38.5861 |

60.7359 |

61.8691 |

78.8032 |

| |

±<50|50> |

38.5955 |

60.7358 |

61.8698 |

78.8023 |

| |

±<60|60> |

37.9282 |

58.8248 |

62.2369 |

78.1875 |

| |

±<70|70> |

36.6879 |

56.8271 |

62.1069 |

77.1257 |

| |

±<80|80> |

35.0924 |

55.0091 |

61.6123 |

75.6645 |

| |

±<90|90> |

34.2107 |

54.0555 |

61.2997 |

74.7633 |

| VSCL |

<0|0> |

34.2107 |

54.0555 |

61.2997 |

74.7633 |

| |

±<0|10> |

34.6226 |

54.4466 |

61.4801 |

75.1274 |

| |

±<0|20> |

35.4858 |

55.2652 |

61.8013 |

75.7836 |

| |

±<0|30> |

36.3912 |

56.1253 |

62.0164 |

76.4088 |

| |

±<0|40> |

37.1433 |

56.8983 |

62.0999 |

76.9914 |

| |

±<0|50> |

37.7003 |

57.7874 |

61.9965 |

77.5991 |

| |

±<0|60> |

38.0251 |

59.0446 |

61.4271 |

78.0214 |

| |

±<0|70> |

37.8989 |

59.7674 |

60.3035 |

77.7714 |

| |

±<0|80> |

38.3278 |

60.0235 |

60.7468 |

78.3712 |

| |

±<0|90> |

38.7412 |

60.7456 |

60.9312 |

78.9178 |

Table 15.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CSCS.

Table 15.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CSCS.

| |

|

Mode |

| Face sheets |

±<Θ0|Θ1> |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| CSCL |

<0|0> |

37.5024 |

57.8947 |

62.3989 |

77.0217 |

| |

±<10|10> |

37.8793 |

58.6101 |

62.5111 |

77.6454 |

| |

±<20|20> |

38.6935 |

60.1009 |

62.6884 |

78.6969 |

| |

±<30|30> |

39.4105 |

61.7087 |

62.6701 |

79.5307 |

| |

±<40|40> |

39.6738 |

62.2541 |

63.0058 |

79.9913 |

| |

±<50|50> |

39.4414 |

61.2449 |

63.7949 |

79.9937 |

| |

±<60|60> |

38.8023 |

59.6105 |

64.2041 |

79.5934 |

| |

±<70|70> |

37.8323 |

57.5893 |

64.3516 |

78.8537 |

| |

±<80|80> |

37.5264 |

57.1583 |

64.1025 |

78.4527 |

| |

±<90|90> |

37.2354 |

56.8524 |

63.9412 |

78.0278 |

| VSCL |

<0|0> |

37.5024 |

57.8947 |

62.3989 |

77.0217 |

| |

±<0|10> |

37.6643 |

58.1857 |

62.4688 |

77.2209 |

| |

±<0|20> |

38.0344 |

58.8009 |

62.5795 |

77.6296 |

| |

±<0|30> |

38.4568 |

59.4867 |

62.6558 |

78.0703 |

| |

±<0|40> |

38.8543 |

60.1697 |

62.6324 |

78.5416 |

| |

±<0|50> |

39.1992 |

60.9189 |

62.4429 |

79.0081 |

| |

±<0|60> |

39.3641 |

61.7311 |

61.8114 |

79.2853 |

| |

±<0|70> |

39.0592 |

60.2489 |

62.5273 |

79.1059 |

| |

±<0|80> |

38.8257 |

59.5672 |

62.0147 |

78.8521 |

| |

±<0|90> |

38.5178 |

59.1782 |

61.6871 |

78.2347 |

Table 16.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CFCF.

Table 16.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CFCF.

| |

|

Mode |

| Face sheets |

±<Θ0|Θ1> |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| CSCL |

<0|0> |

25.3703 |

31.2492 |

49.9557 |

56.6619 |

| |

±<10|10> |

25.5619 |

32.7302 |

50.2086 |

57.8003 |

| |

±<20|20> |

26.2851 |

35.1405 |

51.1297 |

59.5543 |

| |

±<30|30> |

27.5682 |

36.7949 |

52.8277 |

60.5013 |

| |

±<40|40> |

28.8566 |

37.6394 |

54.8188 |

59.5414 |

| |

±<50|50> |

29.7612 |

37.8786 |

56.4734 |

58.0694 |

| |

±<60|60> |

30.3433 |

37.5588 |

56.1658 |

57.6965 |

| |

±<70|70> |

25.3733 |

31.2523 |

49.9548 |

56.6652 |

| |

±<80|80> |

25.1247 |

31.0247 |

49.2178 |

56.1247 |

| |

±<90|90> |

25.0147 |

30.8563 |

48.3578 |

55.2357 |

| VSCL |

<0|0> |

25.3703 |

31.2492 |

49.9557 |

56.6619 |

| |

±<0|10> |

25.4315 |

31.5943 |

50.0411 |

56.9475 |

| |

±<0|20> |

25.6361 |

32.3863 |

50.2951 |

57.6348 |

| |

±<0|30> |

26.0476 |

33.3245 |

50.7796 |

58.5386 |

| |

±<0|40> |

26.7302 |

34.2974 |

51.5551 |

59.6346 |

| |

±<0|50> |

27.6357 |

35.2767 |

52.7227 |

60.9147 |

| |

±<0|60> |

28.6174 |

36.2144 |

54.3692 |

60.8805 |

| |

±<0|70> |

29.5493 |

36.8882 |

56.2009 |

59.7979 |

| |

±<0|80> |

29.8971 |

37.2567 |

58.1478 |

60.8941 |

| |

±<0|90> |

30.4526 |

37.8924 |

59.8654 |

61.7891 |

Table 17.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CFFF.

Table 17.

The first four natural frequencies of the VSCL and CSCL sandwich square plate, CFFF.

| |

|

Mode |

| Face sheets |

±<Θ0|Θ1> |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| CSCL |

<0|0> |

8.5282 |

16.5998 |

27.9785 |

30.2843 |

| |

±<10|10> |

8.6335 |

18.0326 |

28.2266 |

31.9156 |

| |

±<20|20> |

9.0336 |

20.3567 |

29.0842 |

35.0327 |

| |

±<30|30> |

9.8914 |

21.9399 |

30.6438 |

39.7197 |

| |

±<40|40> |

11.1856 |

22.6782 |

32.7076 |

47.1182 |

| |

±<50|50> |

12.6164 |

22.7131 |

35.0052 |

47.6474 |

| |

±<60|60> |

13.8076 |

22.0365 |

37.2562 |

44.5822 |

| |

±<70|70> |

14.5736 |

20.6705 |

38.9595 |

41.8909 |

| |

±<80|80> |

15.4788 |

22.6871 |

39.4871 |

47.8712 |

| |

±<90|90> |

16.2357 |

23.9745 |

40.8912 |

48.6812 |

| VSCL |

<0|0> |

8.5282 |

16.5998 |

27.9785 |

30.2843 |

| |

±<0|10> |

8.5626 |

16.8994 |

28.0598 |

30.7746 |

| |

±<0|20> |

8.6754 |

17.5511 |

28.3184 |

32.1932 |

| |

±<0|30> |

8.9182 |

18.3178 |

28.8461 |

34.7479 |

| |

±<0|40> |

9.3943 |

19.0856 |

29.7155 |

39.1078 |

| |

±<0|50> |

10.2252 |

19.8431 |

31.0342 |

44.8934 |

| |

±<0|60> |

11.4782 |

20.5674 |

32.9513 |

46.3146 |

| |

±<0|70> |

12.9179 |

21.1012 |

35.5303 |

35.5345 |

| |

±<0|80> |

13.6567 |

22.5481 |

36.7841 |

46.7812 |

| |

±<0|90> |

14.8455 |

23.4841 |

37.5984 |

48.6944 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).