Submitted:

10 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

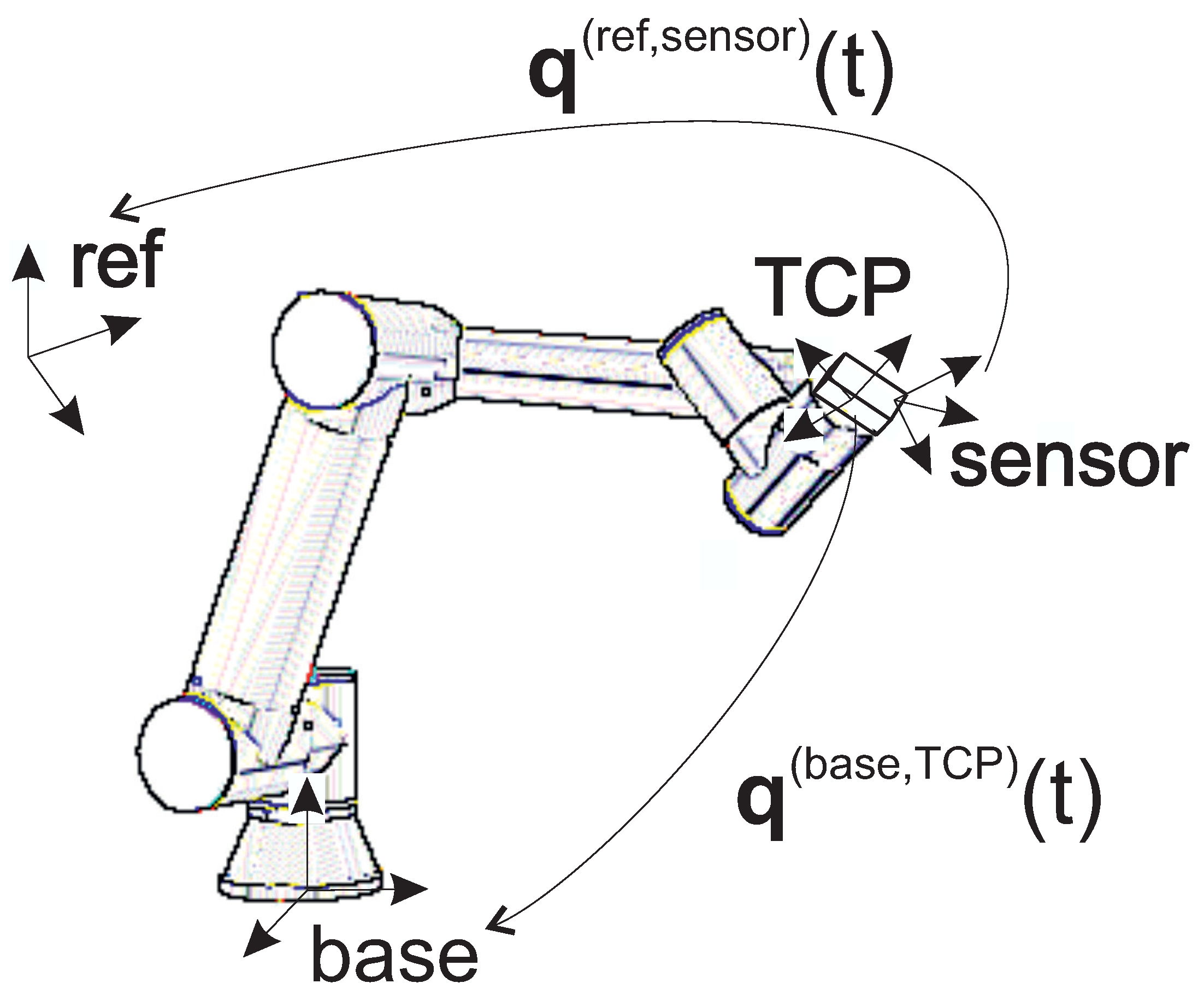

2. Problem Description

3. Calibration Method

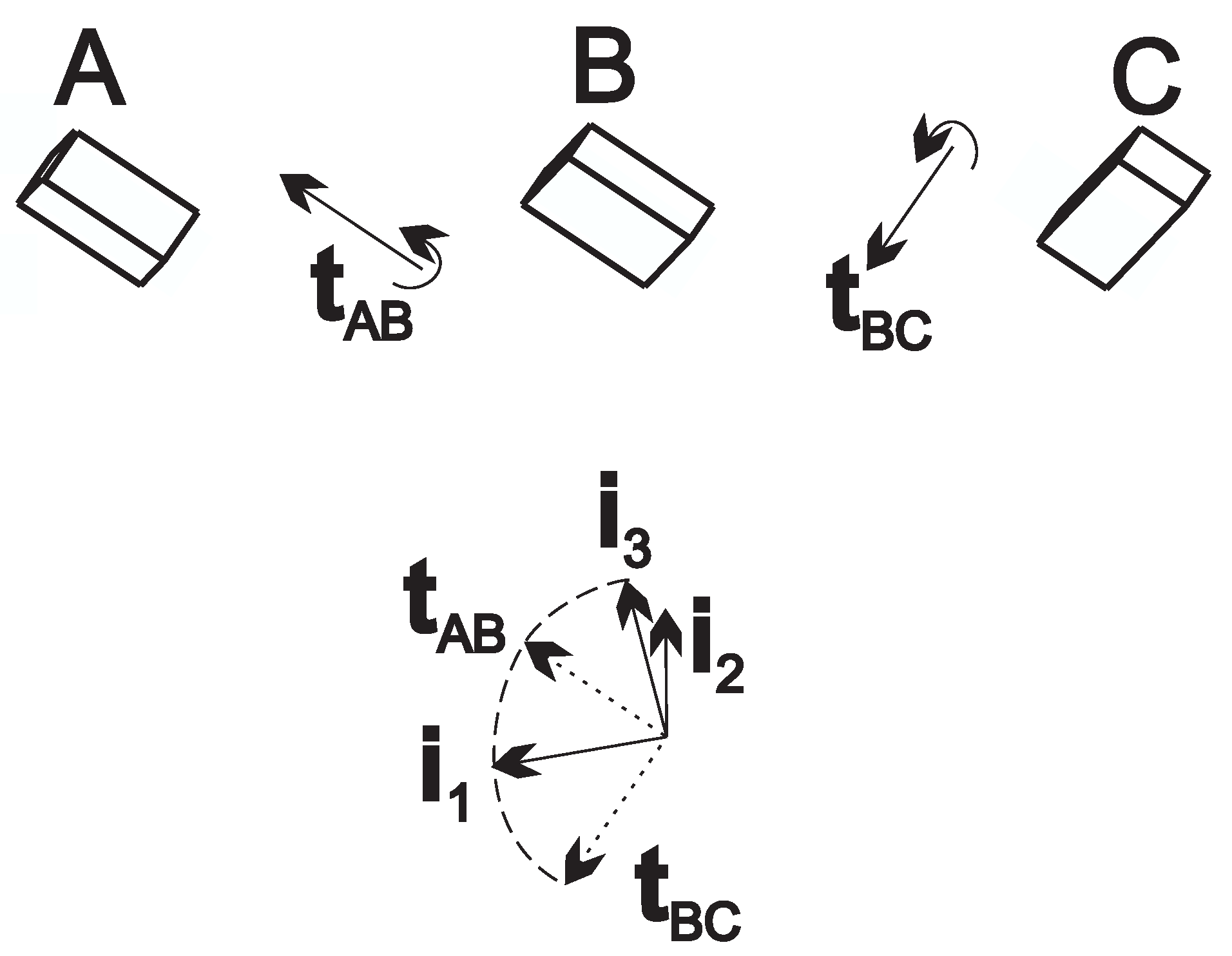

3.1. Initial Guess

3.2. Local Optimization

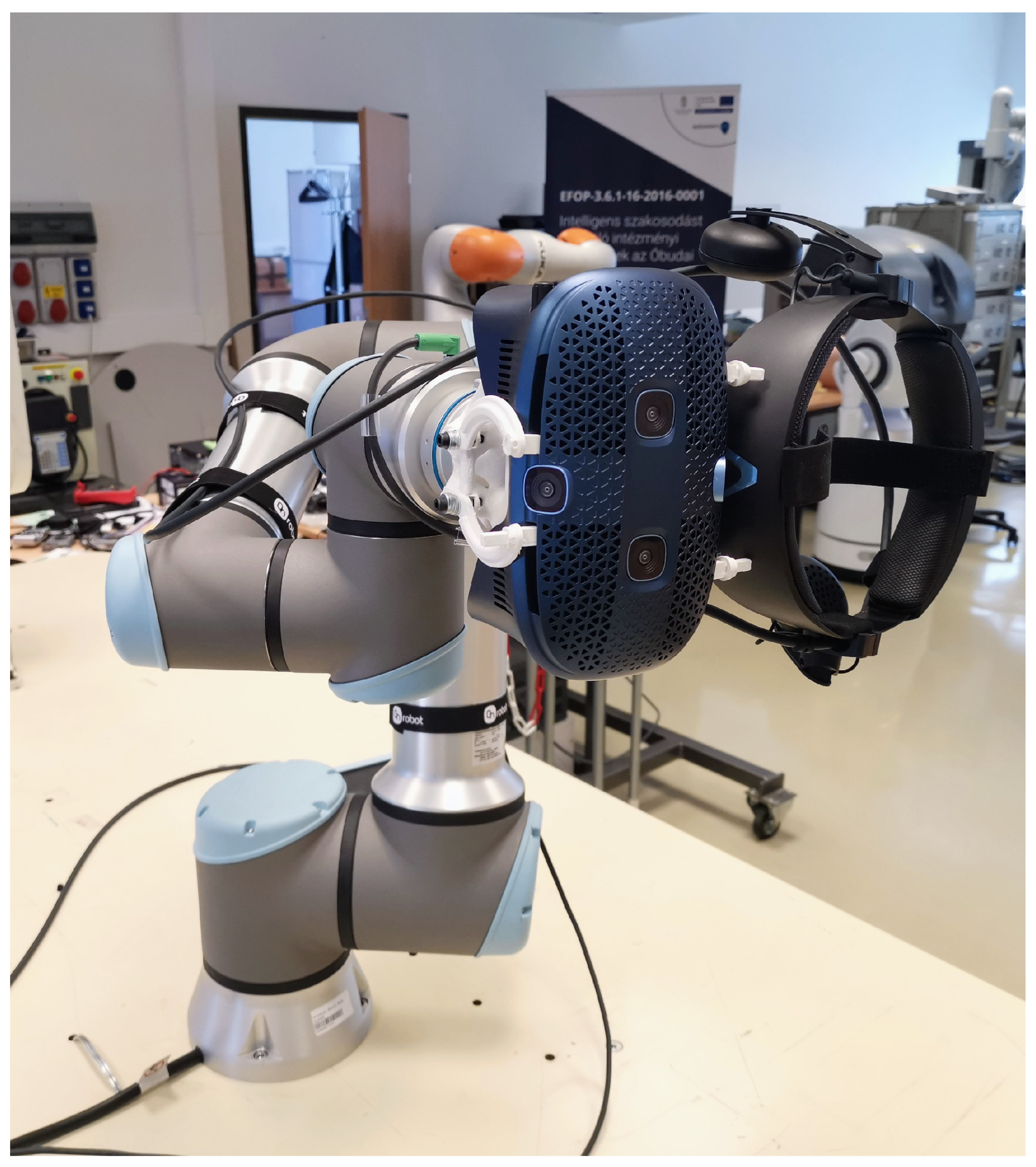

4. Experimental Demonstration

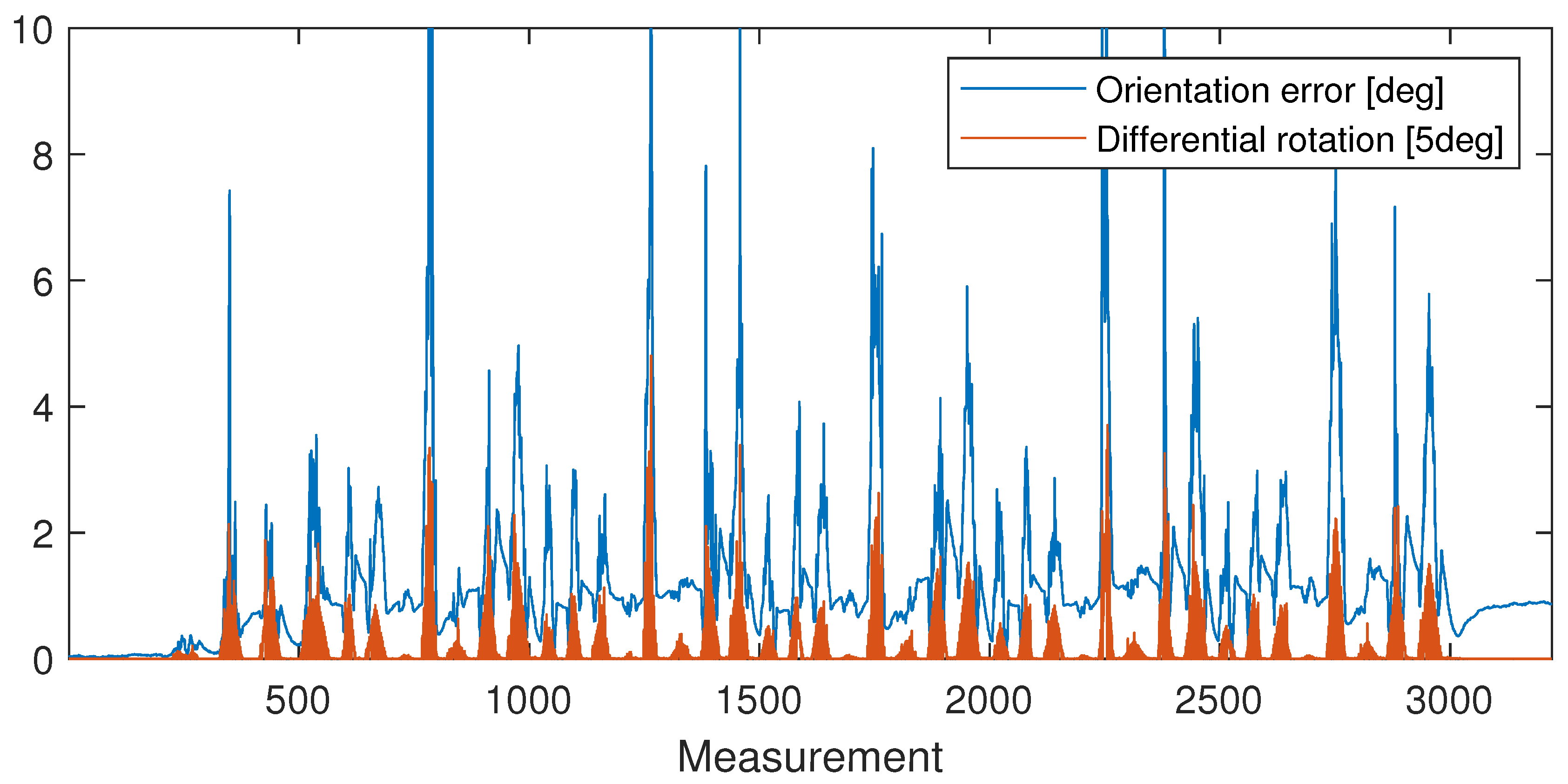

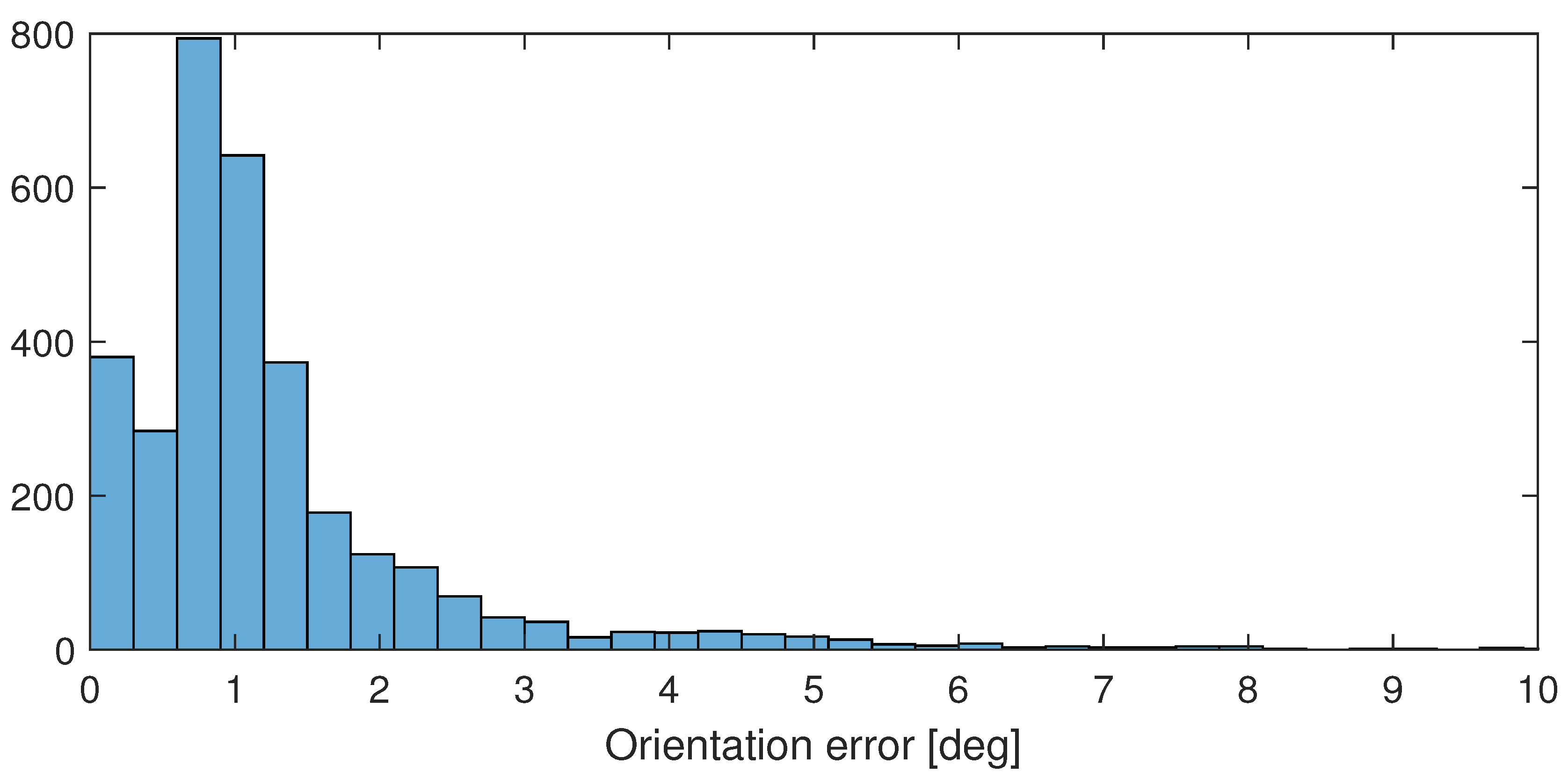

4.1. ICM20948 IMU with Disabled Magnetometer

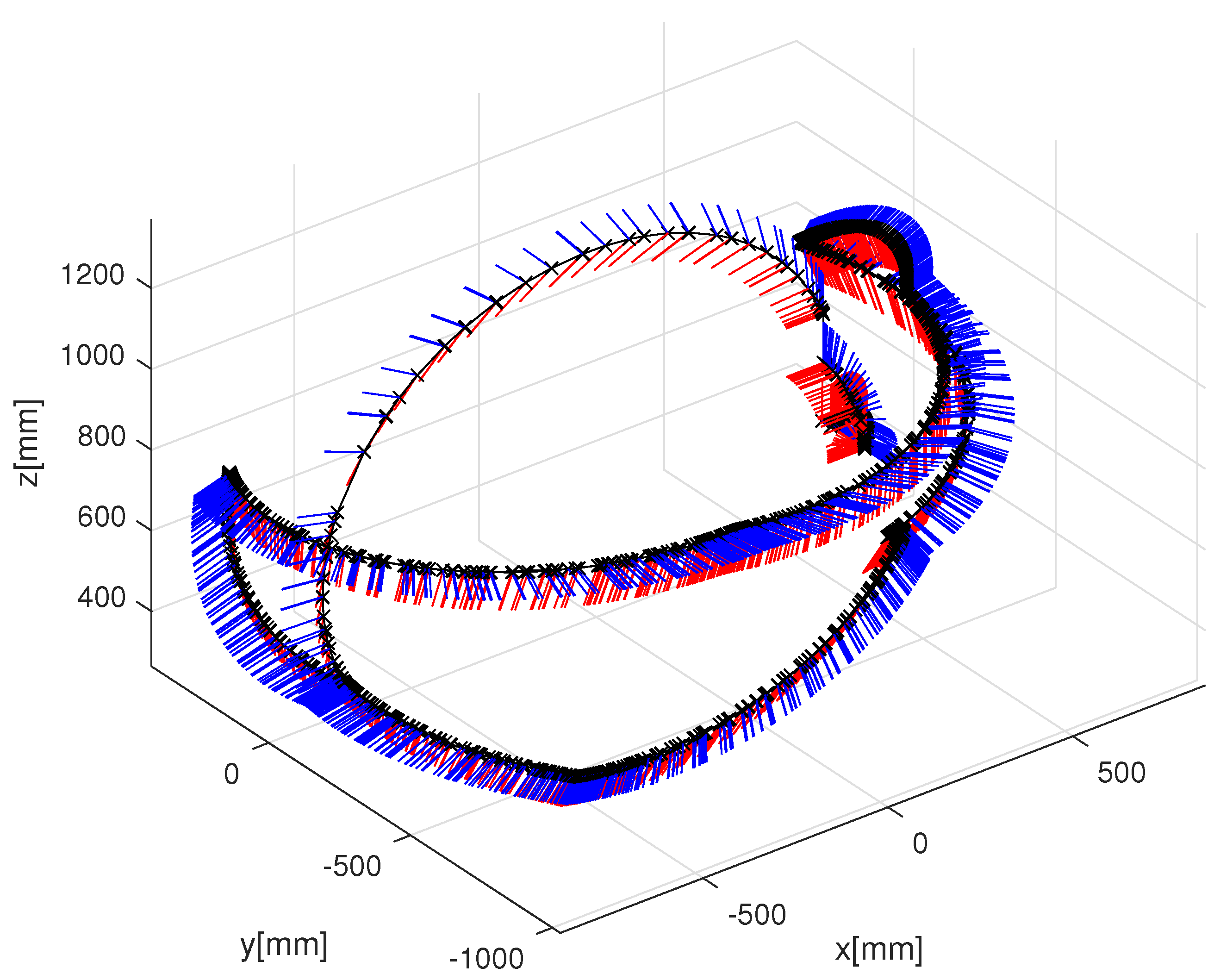

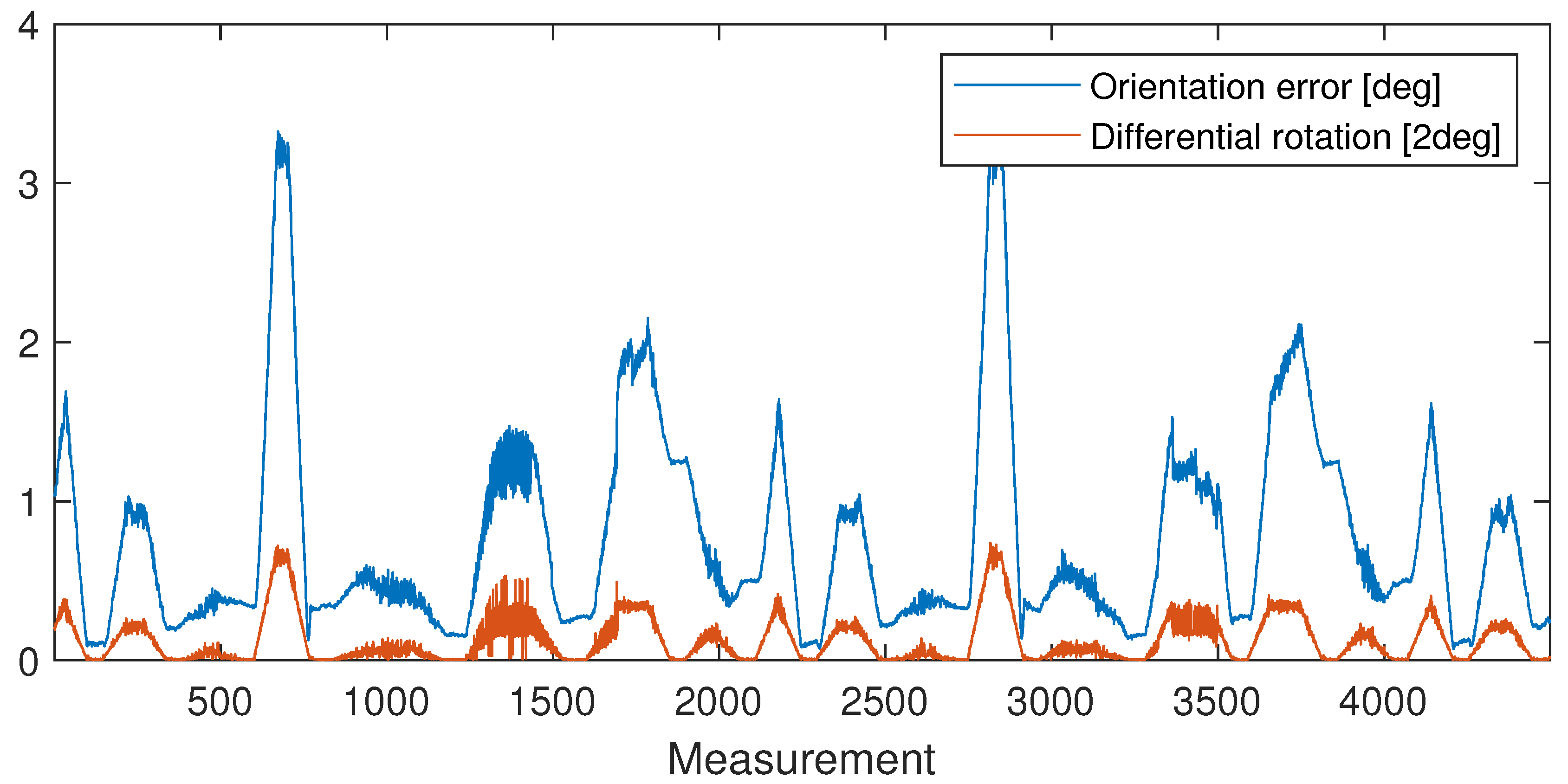

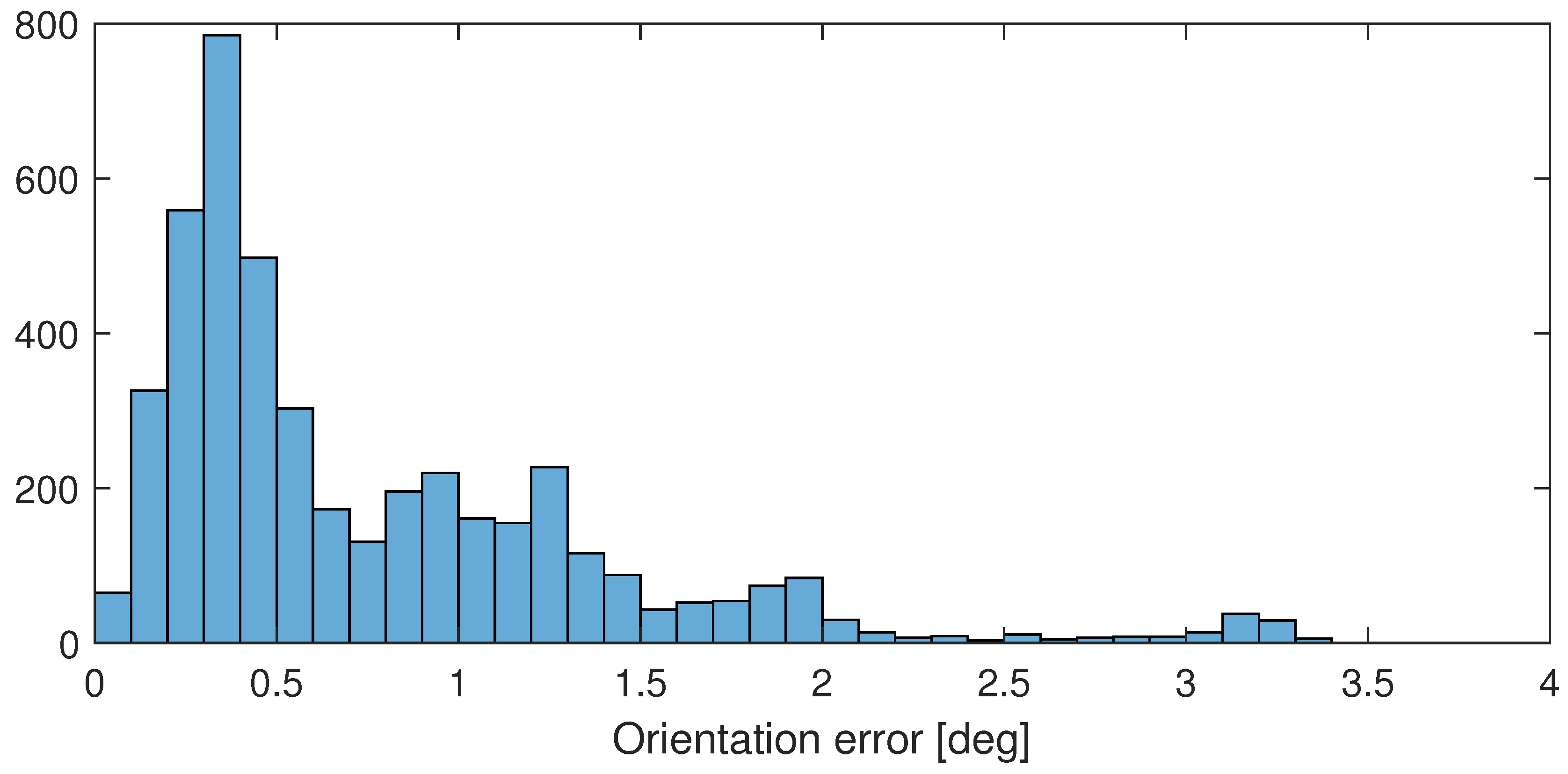

4.2. HTC VIVE (IMU and SLAM Sensor-Fusion Using 6 Cameras)

5. Future Work

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Appendix A

References

- Nijkamp, J.; Schermers, B.; Schmitz, S.; Jonge, C.S.d.; Kuhlmann, K.F.D.; Heijden, F.v.d.; Sonke, J.; Ruers, T.J. Comparing position and orientation accuracy of different electromagnetic sensors for tracking during interventions. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 2016, 11, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumiński, D.; Maik, M.; Walczak, K. Visualizing Financial Stock Data within an Augmented Reality Trading Environment. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica 2019, 16, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Xun, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, L.; Shi, Y. An orientation estimation algorithm based on multi-source information fusion. Measurement Science and Technology 2018, 29, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorkin, V.; Garcia-Fernandez, M.; González-Casado, G.; Li, M.; Rovira-Garcia, A. Assessment of noise of mems imu sensors of different grades for gnss/imu navigation. Sensors 2024, 24, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.J. Using microseismic events to improve the accuracy of sensor orientation for downhole microseismic monitoring. Geophysical Prospecting 2021, 69, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehorster, D.; Li, L.; Lappe, M. The accuracy and precision of position and orientation tracking in the htc vive virtual reality system for scientific research. I-Perception 2017, 8, 204166951770820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veen, S.M.v.d.; Bordeleau, M.; Pidcoe, P.E.; Thomas, J.S. Agreement analysis between vive and vicon systems to monitor lumbar postural changes. Sensors 2019, 19, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylcott, B.; Williams, K.R.; Hinderaker, M.; Lin, C. Comparison of htc vive™ virtual reality headset position measures to center of pressure measures. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2019, 63, 2333–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.M.; Lowndes, B.R.; Fortune, E.; Kaufman, K.R.; Hallbeck, M.S. Validation of inertial measurement units for upper body kinematics. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2017, 33, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vox, J.P.; Weber, A.; Wolf, K.I.; Izdebski, K.; Schüler, T.; König, P.; Wallhoff, F.; Friemert, D. An evaluation of motion trackers with virtual reality sensor technology in comparison to a marker-based motion capture system based on joint angles for ergonomic risk assessment. Sensors 2021, 21, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliley, K.; Kaufman, K.R.; Gilbert, B.K. Methods for validating the performance of wearable motion-sensing devices under controlled conditions. Measurement Science and Technology 2009, 20, 045802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.D.; Marvel, J.A.; Falco, J.A.; Hong, T.H. Measurement science for 6dof object pose ground truth. 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Robotic and Sensors Environments (ROSE) 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herickhoff, C.D.; Morgan, M.R.; Broder, J.; Dahl, J.J. Low-cost volumetric ultrasound by augmentation of 2d systems: design and prototype. Ultrasonic Imaging 2017, 40, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Kraft, M. The impact of the image feature detector and descriptor choice on visual slam accuracy. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 2015, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białecka, M.; Gruszczyński, K.; Cisowski, P.; Kaszyński, J.; Baka, C.; Lubiatowski, P. Shoulder Range of Motion Measurement Using Inertial Measurement Unit—Validation with a Robot Arm. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirking, B.; El-Gohary, M.; Kwon, Y. The feasibility of shoulder motion tracking during activities of daily living using inertial measurement units. Gait & Posture 2016, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero-Valencia, J.; Marquez-Viloria, D.; Castano-Londono, L.; Morantes-Guzmán, L. A low-cost platform based on a robotic arm for parameters estimation of Inertial Measurement Units. Measurement 2017, 110, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, J.; Isaksson, M.; McCormick, J.; Hensman, C. Validation of 3-Space Wireless Inertial Measurement Units Using an Industrial Robot. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuti, J.; Piricz, T.; Galambos, P. Method for Direction and Orientation Tracking Using IMU Sensor. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 10774–10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zhang, H.; San, H.; Sun, G.; Wu, D.D.; Wang, W. Kinematic calibration for industrial robots using articulated arm coordinate machines. International Journal of Modelling, Identification and Control 2019, 31, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsi, N.M.; Mata, M.; Harrison, C.S.; Semple, D. Autonomous robotic inspection system for drill holes tilt: feasibility and development by advanced simulation and real testing. 2023 28th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal Robots. Universal Robot UR16e. Available online: https://www.universal-robots.com/products/ur16-robot/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- TDK - InvenSense. ICM-20948 World’s Lowest Power 9-Axis MEMS MotionTracking Device. Available online: https://invensense.tdk.com/products/motion-tracking/9-axis/icm-20948/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Borges, M.; Symington, A.; Coltin, B.; Smith, T.; Ventura, R. HTC vive: Analysis and accuracy improvement. 2018 IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. on Int. Robots and Syst. (IROS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 2610–2615.

- Dempsey, P. The teardown: HTC Vive VR headset. Engin. & Tech. 2016, 11, 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Soffel, F.; Zank, M.; Kunz, A. Postural stability analysis in virtual reality using the HTC vive. Proc. of the 22nd ACM Conf. on Virtual Reality Soft. and Tech., 2016, pp. 351–352.

- József Kuti, Tamás Piricz, Pétert Galambos. OrientationSensorValidatinon-PublicData-MDPI-Sensors. Available online: https://github.com/ABC-iRobotics/OrientationSensorValidatinon-PublicData-MDPI-Sensors (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Sevensense Robotics, AG. Alphasense Position. Available online: https://www.sevensense.ai/product/alphasense-position (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Kilby, W.; Naylor, M.; Dooley, J.R.; Maurer Jr, C.R.; Sayeh, S. A technical overview of the CyberKnife system. Handbook of robotic and image-guided surgery 2020, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shepperd, S.W. Quaternion from rotation matrix. Journal of Guidance and Control 1978, 1, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).