Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Obtaining Celluloses

2.2.1. Cellulose from Agave Tequila Bagasse (ABP)

2.2.2. Cellulose from Corrugated Paperboard (CPB)

2.2.3. Commercial Cellulose (CC)

2.3. Chemical Properties of Celluloses

2.3.1. Kappa Number (KN)

2.3.2. Ash Content

2.3.3. Viscosity (µ) and Degree of Polymerization (DP)

2.3.4. Elementary Analyses

2.4. Morphology of Celluloses

2.4. Spectroscopy of Celluloses

2.4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR_ATR)

2.4.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.5. Calorimetric Properties of Celluloses

2.6. SMA Asphalt Mix

2.6.1. Schellenberg Drainage (D)

3. Results and Discussion

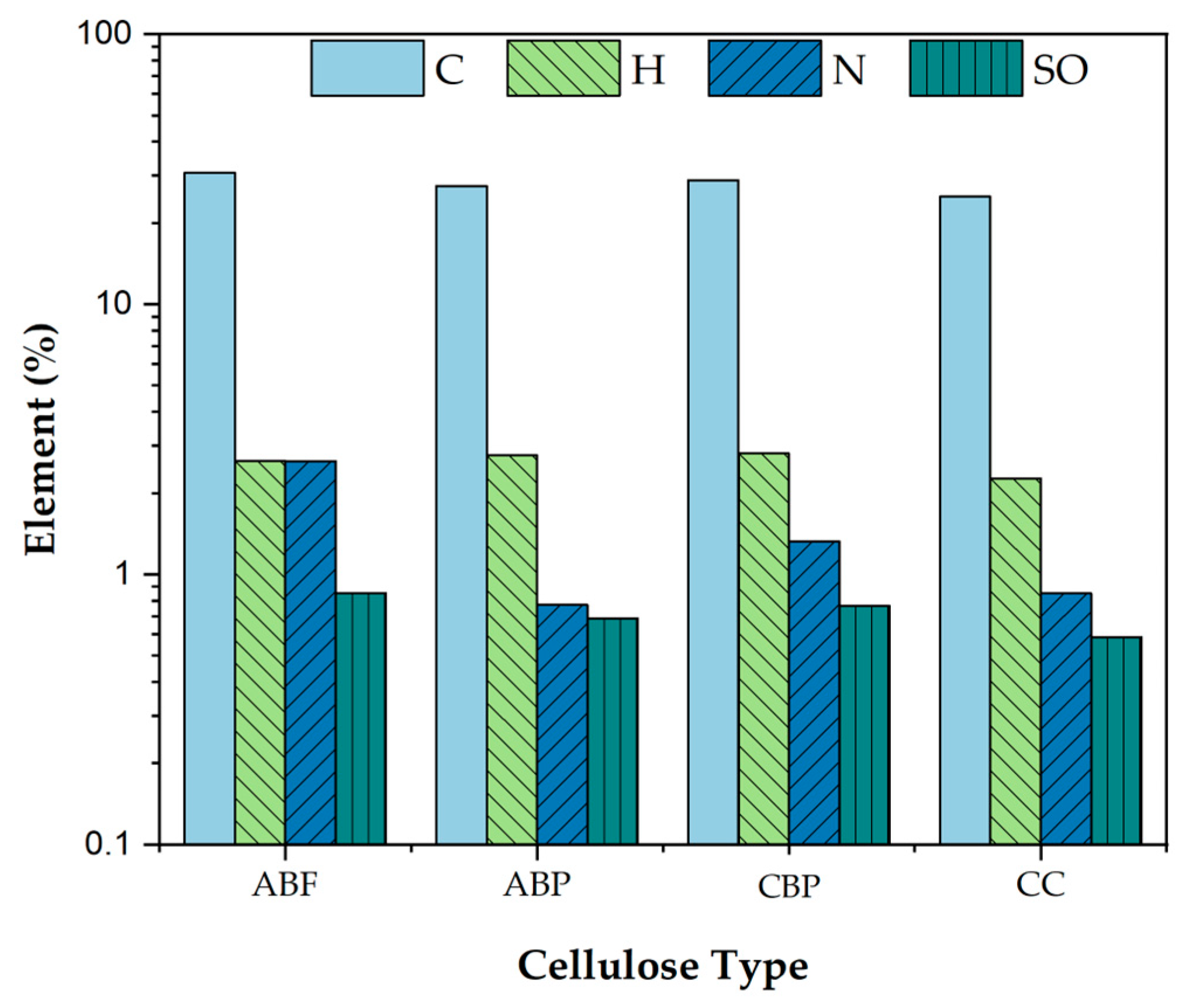

3.1. Chemical Properties of Celluloses

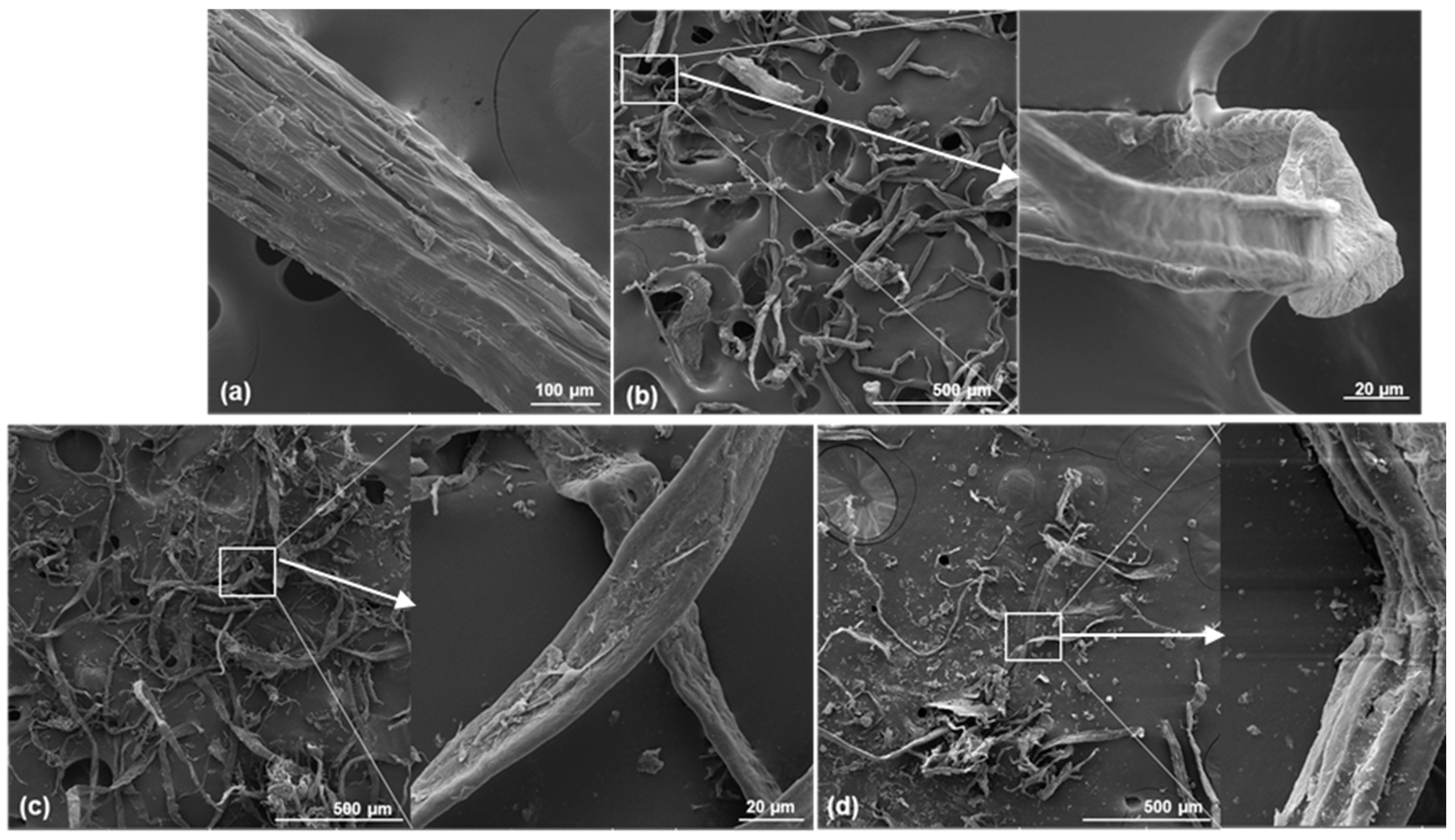

3.2. Morphology of Celluloses

3.3. Spectroscopy of Celluloses

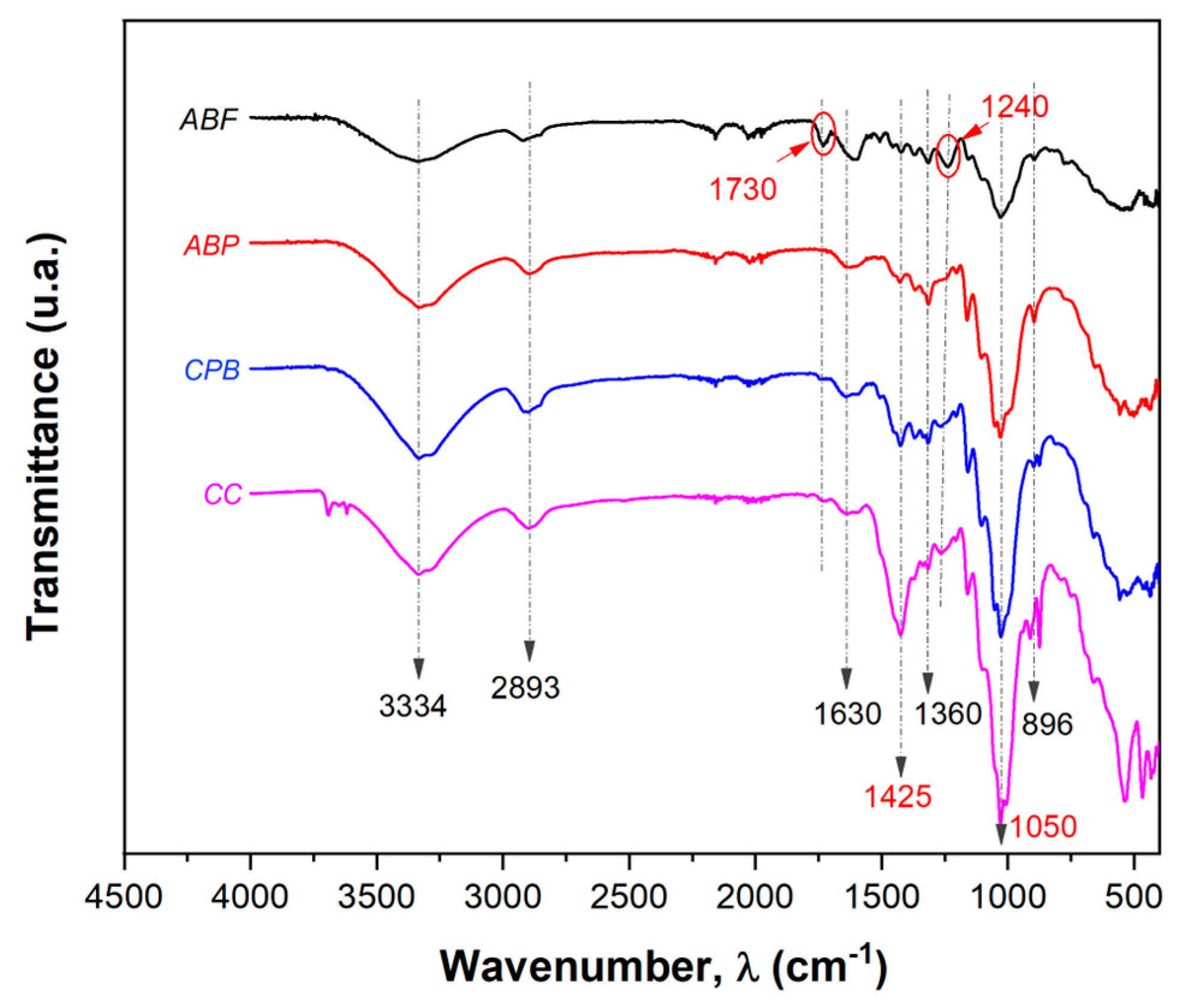

3.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR_ATR)

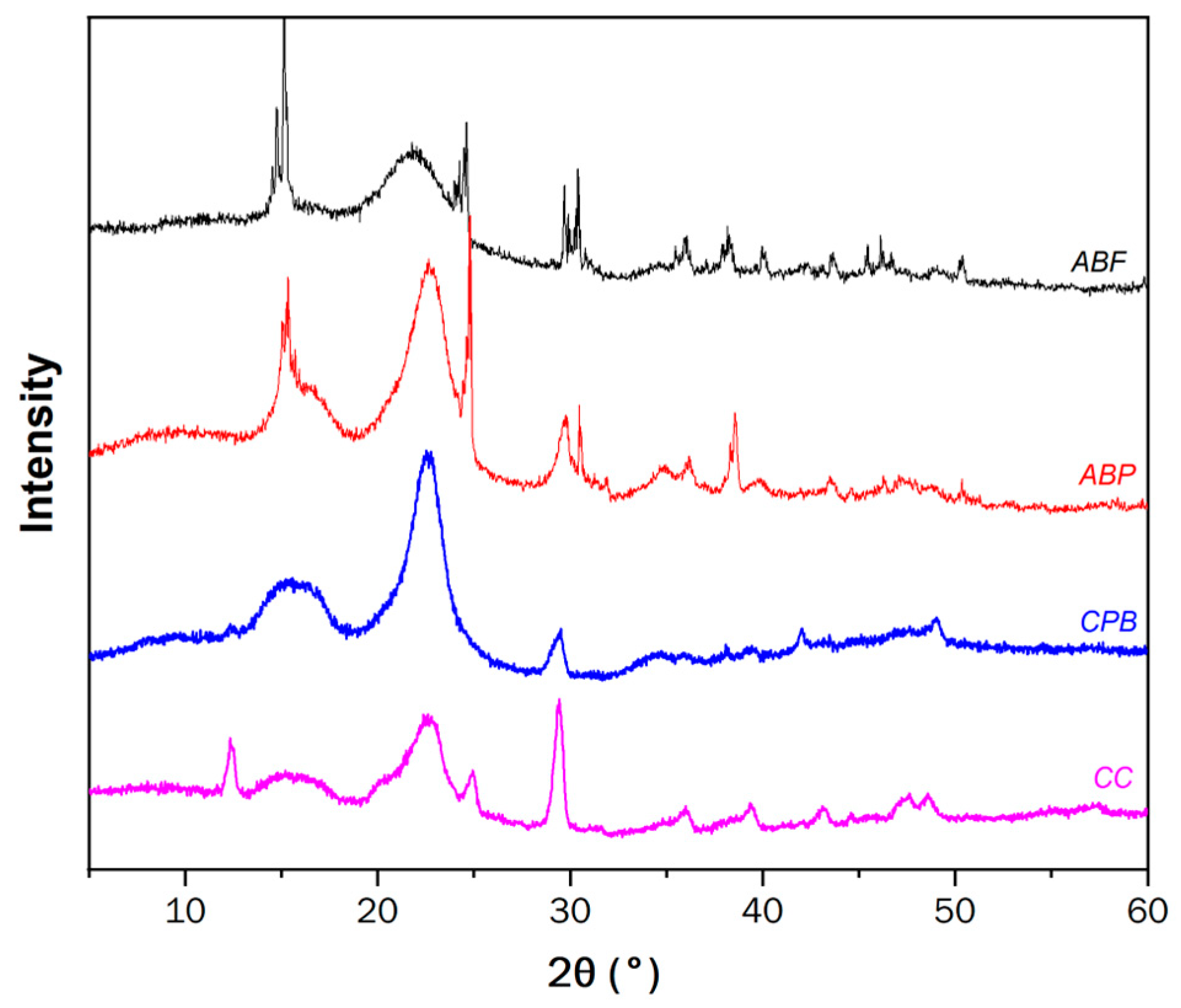

3.4. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

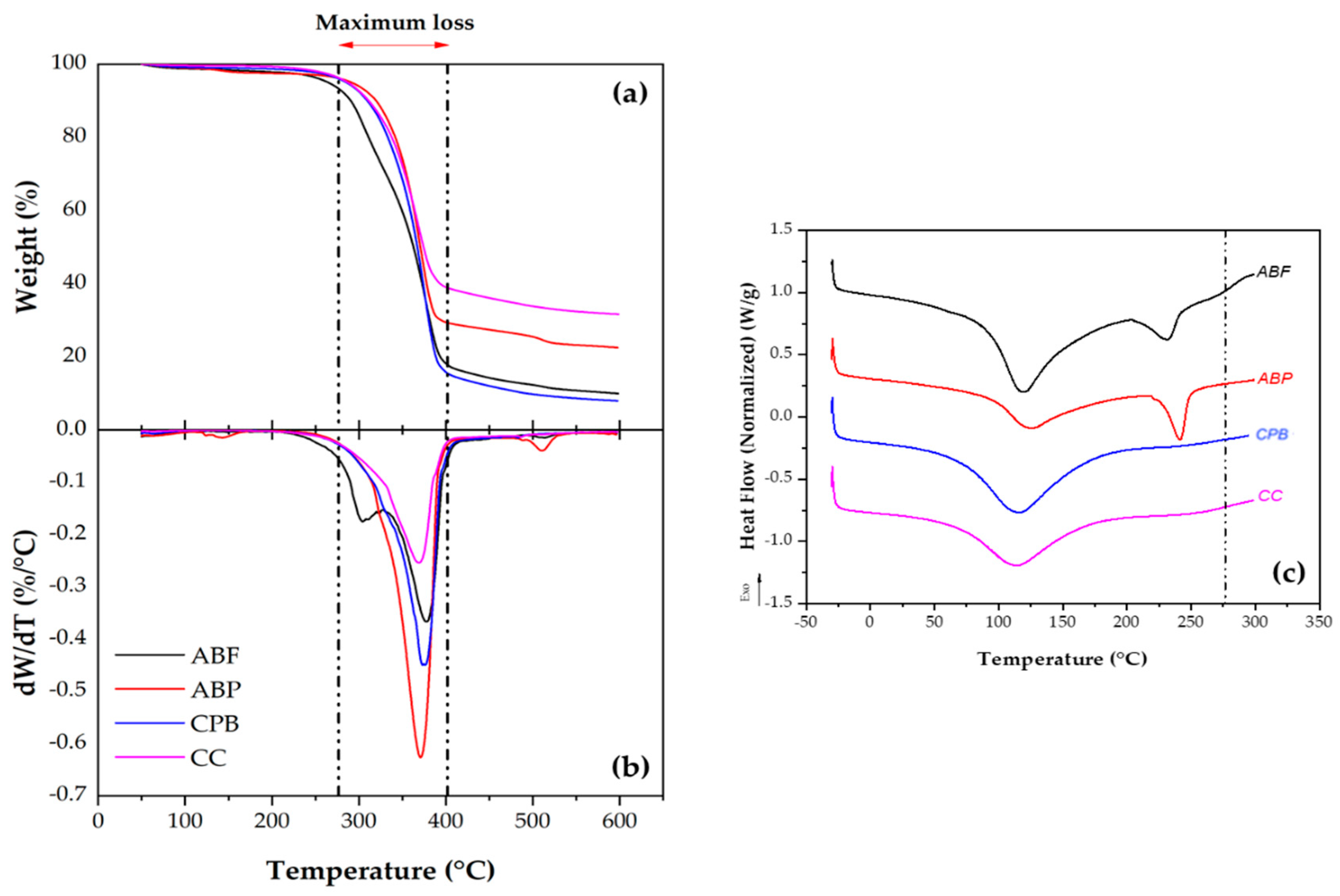

3.5. Calorimetric Properties of Celluloses

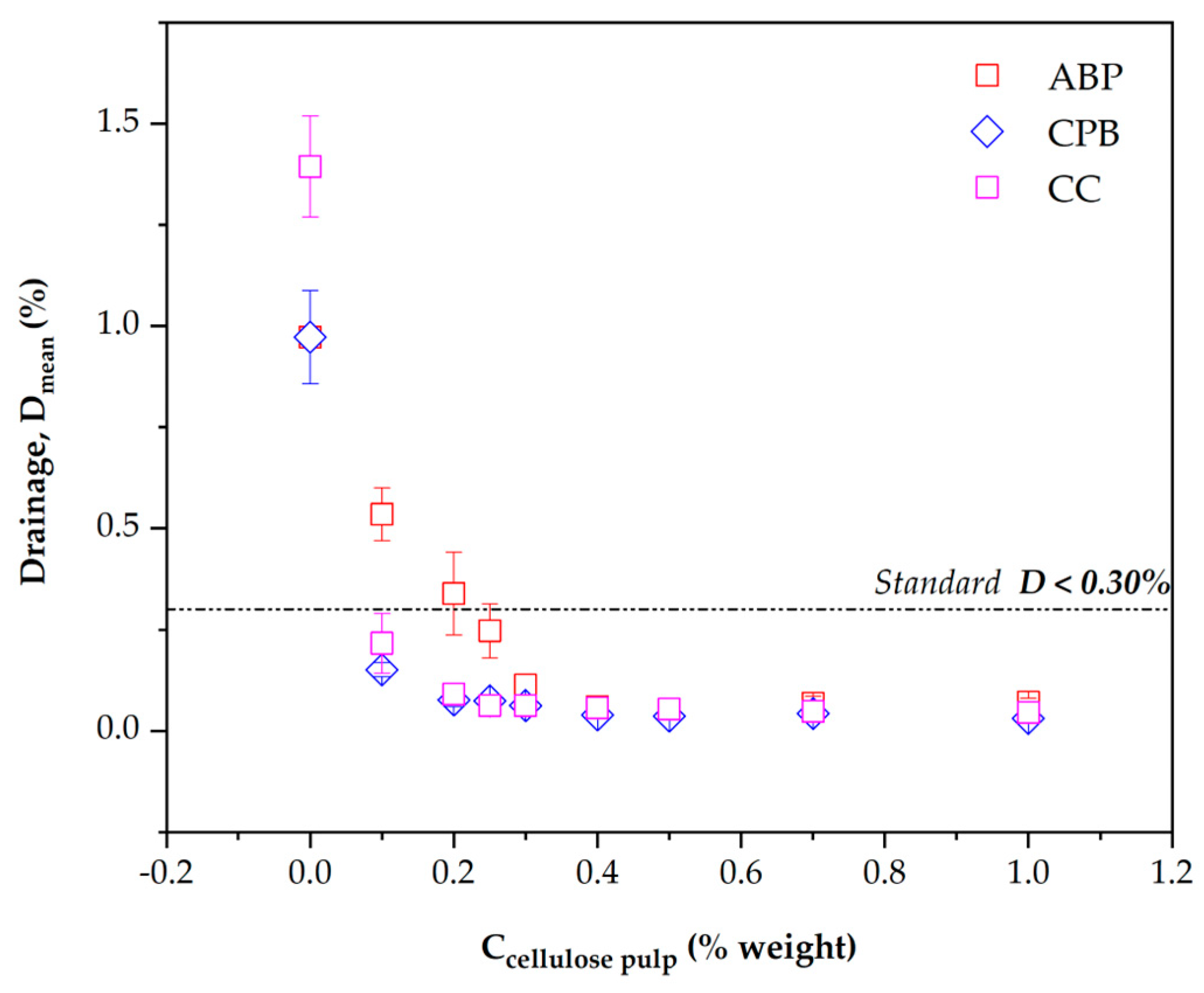

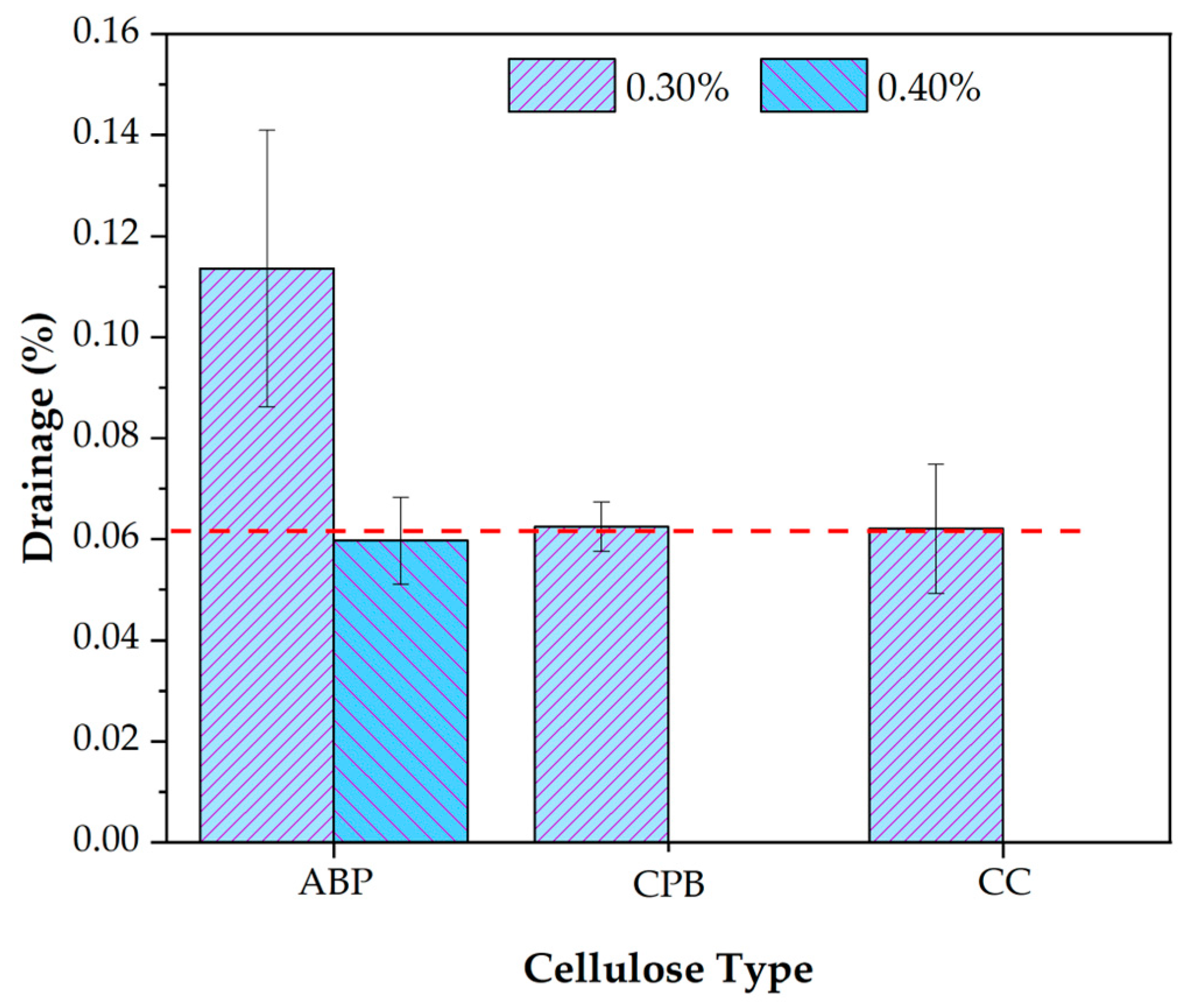

3.6. Schellenberg Drainage (D)

4. Conclusions

- Chemical Properties: The ash content and degree of polymerization were found to have no significant effect on the absorption of asphalt or in mitigating drainage in the asphalt mix. However, the Kappa Number, which is related to lignin content, and the nitrogen (N) content show a relationship. If the lignin content is very low, as observed in ABP cellulose, a higher concentration of cellulose is required to inhibit drainage effectively.

- Morphological Characteristics: The morphology of the celluloses revealed cylindrical longitudinal shapes, similar to filaments, with a parallel structure, some undulations, rough or corrugated texture, and varying filament diameters. This directly affects the absorption of asphalt, as it enhances adhesion between the fibers and the asphalt [33,44]. In this regard, ABP cellulose has a smoother fiber surface, lacking undulations, and features larger filament diameters. In contrast, CPB and CC celluloses exhibit more corrugation and smaller diameters, providing greater contact surface between the cellulose and the asphalt, which improves absorption and adhesion.

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Spectroscopy indicates that ABP, CPB, and CC celluloses exhibit similar spectral characteristics, with a prominent O-H stretching band at 3334 cm⁻¹, contributing to the formation of hydrogen bonds in the carbohydrate structure. C-H and C-O vibrations, associated with cellulose and hemicellulose, appear in all three celluloses at 2893 cm⁻¹. Water absorption is evident at 1630 cm⁻¹ in all three pulps. Lignin removal in ABP is shown by faint bands at 1730 cm⁻¹ (C=O) and 1240 cm⁻¹ (C-O), which are less noticeable in CPB and CC. Crystallinity bands at 896 cm⁻¹ and 1050 cm⁻¹ indicate the presence of β-glycosidic bonds, with intensification as pulping progresses, becoming more prominent in CPB and CC.

- Crystallinity Assessment: The crystallinity obtained from X-ray diffraction demonstrates evidence of crystallinity among the three celluloses. CPB has a crystallinity index (CI = 0.44) and percentage of crystallinity (%Cr = 64.2%), indicating that more than 60% of its structure is crystalline, which contributes to its greater strength and toughness. ABP presents a CI of 0.23 and %Cr of 56.4%, showing lower crystallinity compared to CPB. CC has the lowest values (CI = 0.17 and %Cr = 54.8%), suggesting low crystallinity, stiffness, and strength. This indicates that the pulping process affects the structural organization of cellulose, with CPB being the most crystalline and resistant. This observation is corroborated by the total crystallinity index (TCI) and is related to the degree of polymerization (DP), both of which are higher in CPB, followed by ABP, with CC cellulose exhibiting the lowest values.

- Performance as Drainage Stabilizers: CPB and ABP are excellent alternatives to CC cellulose for drainage stabilization, with CPB being the most effective at low concentrations. This effectiveness is attributed to its morphology—including roughness, waviness, filament length, orientation, and diameter, as described by Sahu and Gupta [49] —as well as its lignin content and degree of crystallinity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassani, A.; Taghipoor, M.; Karimi, M.M. A State of the Art of Semi-Flexible Pavements: Introduction, Design, and Performance. Constr Build Mater 2020, 253, 119196. [CrossRef]

- Thives, L.P.; Ghisi, E. Asphalt Mixtures Emission and Energy Consumption: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 72, 473–484.

- Solatiyan, E.; Bueche, N.; Carter, A. A Review on Mechanical Behavior and Design Considerations for Reinforced-Rehabilitated Bituminous Pavements. Constr Build Mater 2020, 257, 119483. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q. Hybrid Modification of Stone Mastic Asphalt with Cellulose and Basalt Fiber. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Oda, S.; Leomar Fernandes, J.; Ildefonso, J.S. Analysis of Use of Natural Fibers and Asphalt Rubber Binder in Discontinuous Asphalt Mixtures. Constr Build Mater 2012, 26, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, B.; Miranda, L.; Costa, A.; Sánchez, F.; Lanchas, S.; Expósito, S. Diseño de Mezclas SMA, Como Capa de Rodadura e Intermedia, Para Su Empleo En España; 2012;

- AASHTO M325 Standard Specification for Stone Matrix Asphalt (SMA). 2012.

- De la Cruz Analya, E. Estabilización de Mezclas Asfálticas Stone Mastic Asphalt Utilizando Fibras de Basalto Como Sustituto de Las Fibras de Celulosa, Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, Perú. Tesis de Maestría, 2019.

- Morán, D. Modelos de Biorrefinería-La Biorrefinería Lignocelulósica Available online: https://biorrefineria.blogspot.com/2016/04/modelos-de-biorrefineria-lignocelulosica.html.

- Sierra, E.; Alcaraz, J.; Valdivia, Á.; Rosas, A.; Hernández, M.; Vilvaldo, E.; Martínez, A. Bagazo de Agave: De Desecho Agroindustrial a Materia Prima En Las Biorrefinerías Available online: http://ciencia.unam.mx/leer/1112/bagazo-de-agave-de-desecho-agroindustrial-a-materia-prima-en-las-biorrefinerias-.

- Preciado Bolívar, C.A.; Sierra Martínez, C.E. Utilización de Fibras Desechas de Proceso Industriales Como Estabilizador de Mezclas Asfálticas SMA, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2013.

- Karimah, A.; Ridho, M.R.; Munawar, S.S.; Adi, D.S.; Ismadi; Damayanti, R.; Subiyanto, B.; Fatriasari, W.; Fudholi, A. A Review on Natural Fibers for Development of Eco-Friendly Bio-Composite: Characteristics, and Utilizations. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 13, 2442–2458. [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, M.R.; Madhu, P.; Jawaid, M.; Senthamaraikannan, P.; Senthil, S.; Pradeep, S. Characterization and Properties of Natural Fiber Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. J Clean Prod 2018, 172, 566–581. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Mittal, V. Polymer Composites with Functionalized Natural Fibers. Biodegradable and Biocompatible Polymer Composites: Processing, Properties and Applications 2018, 157–186. [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, R.M.; Mackiewicz-Talarczyk, M.; Barriga-Bedoya, J. New Emerging Natural Fibres and Relevant Sources of Information. Handbook of Natural Fibres: Second Edition 2020, 1, 747–787. [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, S.M.; Sheikhzadeh, M.; Hejazi, S.M. Fiber-Reinforced Asphalt-Concrete - A Review. Constr Build Mater 2010, 24, 871–877.

- Delgado-Ramírez, C.; Núñez-Palenius, H. Establecimiento de Agave (Agave Tequilana Weber Var. Azul) En Un Sistema de Inmersión Temporal (SIT). Jóvenes en la Ciencia 2015, 1, 54–59.

- Gallardo-Sánchez, M.A.; Hernández, J.A.; Casillas, R.R.; Vázquez, J.I.E.; Hernández, D.E.; Martínez, J.F.A.S.; Enríquez, S.G.; Balleza, E.R.M. Obtaining Soluble-Grade Cellulose Pulp from Agave Tequilana Weber Var. Azul Bagasse. Bioresources 2019, 14, 9867–9881. [CrossRef]

- Consejo Regulador del Tequila (CRT) Datos Estadísticos de Producción Total Available online: https://www.crt.org.mx/EstadisticasCRTweb/.

- González-García, Y.; González-Reynoso, O.; Nungaray-Arellano, J. Potencial Del Bagazo de Agave Tequilero Para La Producción de Biopolímeros y Carbohidrasas Por Bacterias Celulolíticas y Para La Obtención de Compuestos Fenólicos. eGnosis 2005, 3, 18.

- Hidalgo-Reyes, M.; Caballero-Caballero, M.; Hernández-Gómez, L.H.; Urriolagoitia-Calderón, G. Chemical and Morphological Characterization of Agave Angustifolia Bagasse Fibers. Bot Sci 2015, 93, 807. [CrossRef]

- Kestur G., S.; Flores-Sahagun, T.H.S.; Dos Santos, L.P.; Dos Santos, J.; Mazzaro, I.; Mikowski, A. Characterization of Blue Agave Bagasse Fibers of Mexico. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2013, 45, 153–161. [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T236 om-06 Kappa Number of Pulp. Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry. 2006, 10–14.

- TAPPI T211 om-85 Cenizas En Madera y Pulpa. Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry. 1985.

- TAPPI T230 om-19 Viscosity of Pulp (Capillary Viscometer Method). Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry. 2019, 27–33.

- ASTM D1795 Standard Test Method for Intrinsic Viscosity of Cellulose. ASTM International 2013, 1–6.

- Magaña-Orozco, M. Evaluación de Bagazo de Agave Como Agente Estabilizador de Asfalto En El Diseño de Una Mezcla SMA, Universidad de Guadalajara. Tesis de Licenciatura, 2022.

- Nikolaides, A.F. Bituminous Mixtures & Pavements VI; CRC Press.; 2015; ISBN 978-1-315-66816-1.

- Pérez-Pimienta, J.A.; López-Ortega, M.G.; Sanchez, A. Recent Developments in Agave Performance as a Drought-Tolerant Biofuel Feedstock: Agronomics, Characterization, and Biorefi Ning. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2017, 11, 732–748. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Namjoshi, S.A. Evaluation of Thermal Degradation Behavior of Cardboard Waste. In Intelligent Energy Management Technologies. Algorithms for Intelligent Systems: ICAEM 2019; Mohammad, S.U., Avdhesh, S., Kusum, L.A., Mukesh, S., Eds.; Springer Singapore.: Singapore, 2021; pp. 45–52.

- Valenzuela, A. A New Agenda for Blue Agave Landraces: Food, Energy and Tequila. GCB Bioenergy 2011, 3, 15–24. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, I.; Haider, Q.; Sharma, C. Characterization of Regenerated Cellulose Prepared from Different Pulp Grades Using a Green Solvent. Cellulose Chemistry and Technology 2019, 53, 643–653. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fa, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Chen, H. Investigation on Characteristics and Properties of Bagasse Fibers: Performances of Asphalt Mixtures with Bagasse Fibers. Constr Build Mater 2020, 248, 118648. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhan, H.; Yu, X.; Tang, W.; Xue, Q. Investigation of the Aging Behavior of Cellulose Fiber in Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement. Constr Build Mater 2021, 271. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, W.; Liu, W.; Yin, Y.; Cong, P. Investigation on the Characteristics and Effect of Plant Fibers on the Properties of Asphalt Binders. Constr Build Mater 2022, 338, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Rosli, N.A.; Ahmad, I.; Abdullah, I. Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals from Agave Angustifolia Fibre. Bioresources 2013, 8, 1893–1908. [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Suai, G. Extraction and Characterization of Nanocellulose from Xanthoceras Sorbifolia Husk. International Journal of Nanoscience and Nanoengineering 2015, 2, 43–50.

- Kathirselvam, M.; Kumaravel, A.; Arthanarieswaran, V.P.; Saravanakumar, S.S. Characterization of Cellulose Fibers in Thespesia Populnea Barks: Influence of Alkali Treatment. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 217, 178–189. [CrossRef]

- Robles, E.; Fernández-Rodríguez, J.; Barbosa, A.M.; Gordobil, O.; Carreño, N.L.V.; Labidi, J. Dataset on Cellulose Nanoparticles from Blue Agave Bagasse and Blue Agave Leaves. Data Brief 2018, 18, 150–155. [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, M.R.; Madhu, P.; Jawaid, M.; Senthamaraikannan, P.; Senthil, S.; Pradeep, S. Characterization and Properties of Natural Fiber Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. J Clean Prod 2018, 172, 566–581. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Hermosillo, A.B. Estudio de La Liberación Controlada de Rosa Bengala, Mediante El Uso de Hidrogeles Acrílicos Reforzados Con Celulosa Nanocristalina (CNC), 2020, Vol. 52.

- Kumar, A.; Singh Negi, Y.; Choudhary, V.; Kant Bhardwaj, N. Characterization of Cellulose Nanocrystals Produced by Acid-Hydrolysis from Sugarcane Bagasse as Agro-Waste. Journal of Materials Physics and Chemistry 2020, 2, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, F.; Colom, X.; Suñol, J.J.; Saurina, J. Structural FTIR Analysis and Thermal Characterisation of Lyocell and Viscose-Type Fibres. Eur Polym J 2004, 40, 2229–2234. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W. Laboratory Research of Optimum Fiber Content in SMA Mixture Based on High Temperature Performance. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 361–363, 1709–1712. [CrossRef]

- León-Fernández, V.; Rieumont-Briones, J.; Bordallo-López, E.; Gastón-Peña, C.; Chanfón-Curbelo, J. Caracterización Térmica , Estructural y Morfológica de Un Copolímero Base Celulosa. 2014, 45, 66–72.

- Aguilar-Penagos, A.; Gómez-Soberón, J.M.; Rojas-Valencia, M.N. Physicochemical, Mineralogical and Microscopic Evaluation of Sustainable Bricks Manufactured with Construction Wastes. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.L.; Frollini, E.; da Silva, C.G.; Wypych, F.; Satyanarayana, K.G. Characterization of Banana, Sugarcane Bagasse and Sponge Gourd Fibers of Brazil. Ind Crops Prod 2009, 30, 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Chandra, S.; Bose, S. Laboratory Investigations on SMA Mixes with Different Additives. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2007, 8, 11–18. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Gupta, M.K. Sisal (Agave Sisalana) Fibre and Its Polymer-Based Composites: A Review on Current Developments. Reinforced plastics and composites 2017, 36, 1759–1780. [CrossRef]

| Cellulose type | Kappa Number KN |

% lignin | % ash | Intrinsic Viscosity η (mL/g) |

Degree of Polymerization DP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABF | 118.17 ± 0.7 | 17.8 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | - | - | |

| ABP | 13.9 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 482.72 ± 14.22 | 692.60 ± 22.5 | |

| CPB | 67.0 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | 505.78 ± 0.68 | 729.23 ± 1.1 | |

| CC | 30.9 ± 2.4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 20.7 ± 0.1 | 302.36 ± 46.85 | 413.45 ± 70.7 |

| Wavenumber (λ) |

Area ratio (Aλ/Aλ896) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABF | ABP | CPB | CC | |

| 3334 | 9.50 ± 1.95 | 4.92 ± 0.23 | 4.50 ± 0.41 | 4.17 ± 0.39 |

| 2893 | 5.19 ± 0.24 | 2.82 ± 1.01 | 2.75 ± 0.85 | 1.73 ± 0.03 |

| 1730 | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.13 ± 0.08 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.03 |

| 1630 | 2.93 ± 0.39 | 0.67 ± 0.10 | 0.72 ± 0.06 | 0.33 ± 0.08 |

| 1425 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 0.66 ± 0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.10 | 2.53 ± 0.13 |

| 1360 | 0.70 ± 0.07 | 1.41 ± 0.08 | 1.27 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.01 |

| 1240 | 2.66 ± 0.21 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 0.75 ± 0.08 |

| 1050 | 8.09 ± 0.56 | 6.67 ± 0.04 | 5.95 ± 0.03 | 7.58 ± 0.07 |

| ABF | ABP | CPB | CC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCI= A1360/2893 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 0.72 ± 0.04 |

| IC | - | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.17 |

| %Cr | - | 56.44 | 64.18 | 54.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).