Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

11 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining Recombinant sGn and sGc Antigens Expressed in Pichia Pastoris

2.1.1. Design of antigens based on the exposed regions of the Gn and Gc glycoproteins of ANDV

2.1.2. Expression and Purification of sGn Antigen in Pichia Pastoris Using Methanol Induction and Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) Precipitation

2.1.3. Co-Expression of sGn and sGc Antigens in Pichia Pastoris

2.1.4. Cell Disruption and Fractionation of Induced Yeast Clones to Measure the Expression of sGn and sGc

2.2. Pilot-scale expression, purification and characterization of sGn and sGc antigens in Pichia pastoris

2.2.1. Expression and Rupture of Recombinant sGn and sGc Antigens by Fermentation of Doubly Transformed Pichia Pastoris

2.2.2. Solubilization of Recombinant sGn and sGc Antigens

2.2.3. Purification of sGn and sGc by Metal Ion Affinity Chromatography (IMAC)

2.2.4. Refolding of sGn and sGc by Ultrafiltration

2.3. Immunological Validation of Recombinant Antigens

2.3.1. Vaccinal Formulations

- -

- Formulation 1: FIA + PBS (1:1)

- -

- Formulation 2: AlOH + PBS (1:1)

- -

- Formulation 3: sGn/sGc-FIA (20 µg) (1:1)

- -

- Formulation 4: sGn/sGc-AlOH (20 µg) (1:1)

2.3.2. Animals and Experimental Design

2.3.3. Blood Collection

2.3.4. Quantification of Total IgG Antibodies by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.3.5. Evaluation of the Cytokine Profile of Splenocytes

3. Results

3.1. Design, Expression and Purification of a Soluble Variant of the ANDV Gn Glycoprotein in Pichia Pastoris

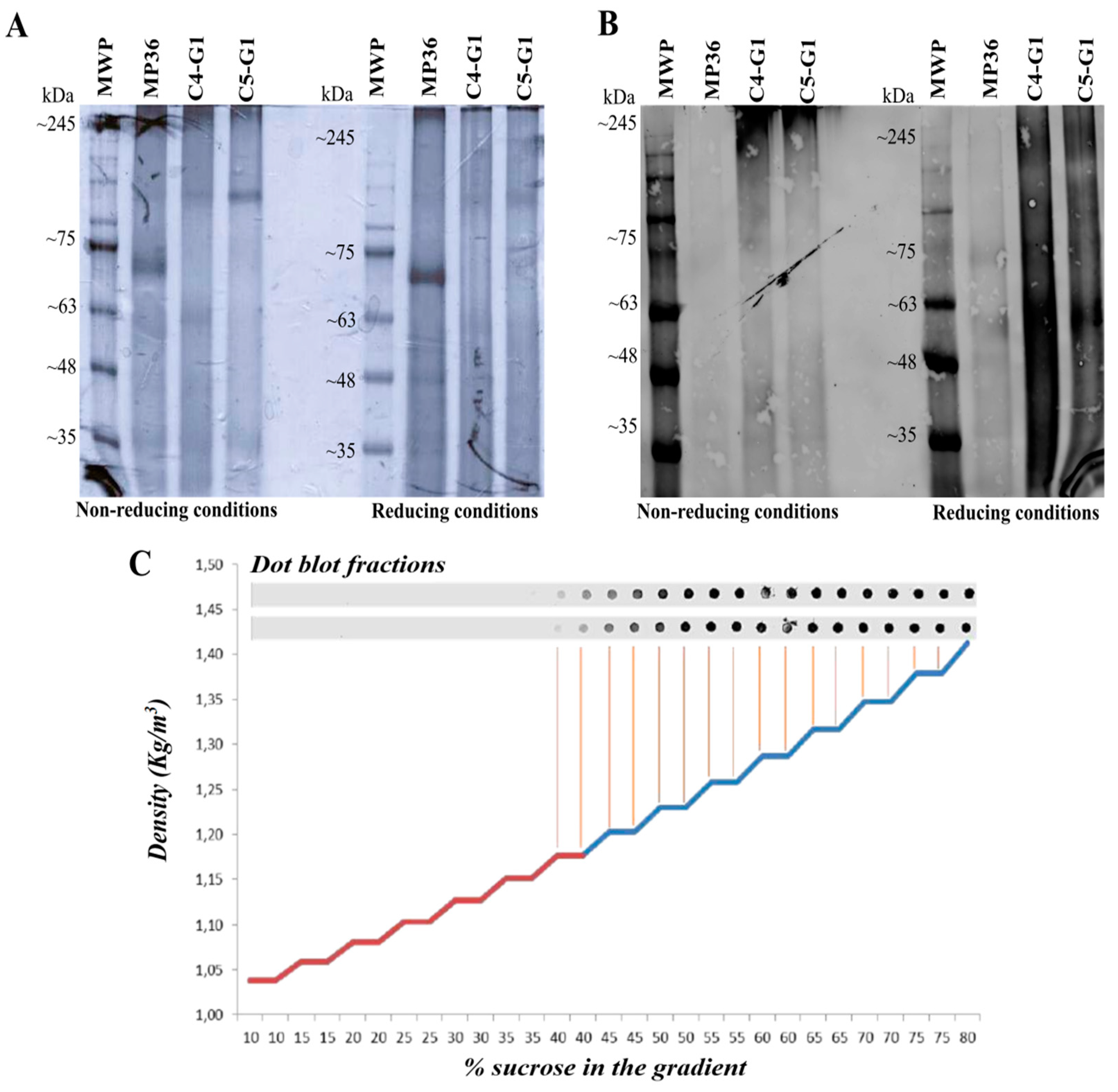

3.2. Design and Co-Expression of the Soluble Variant of the ANDV Gc Glycoprotein in the C4-G1 Pichia Pastoris Clone

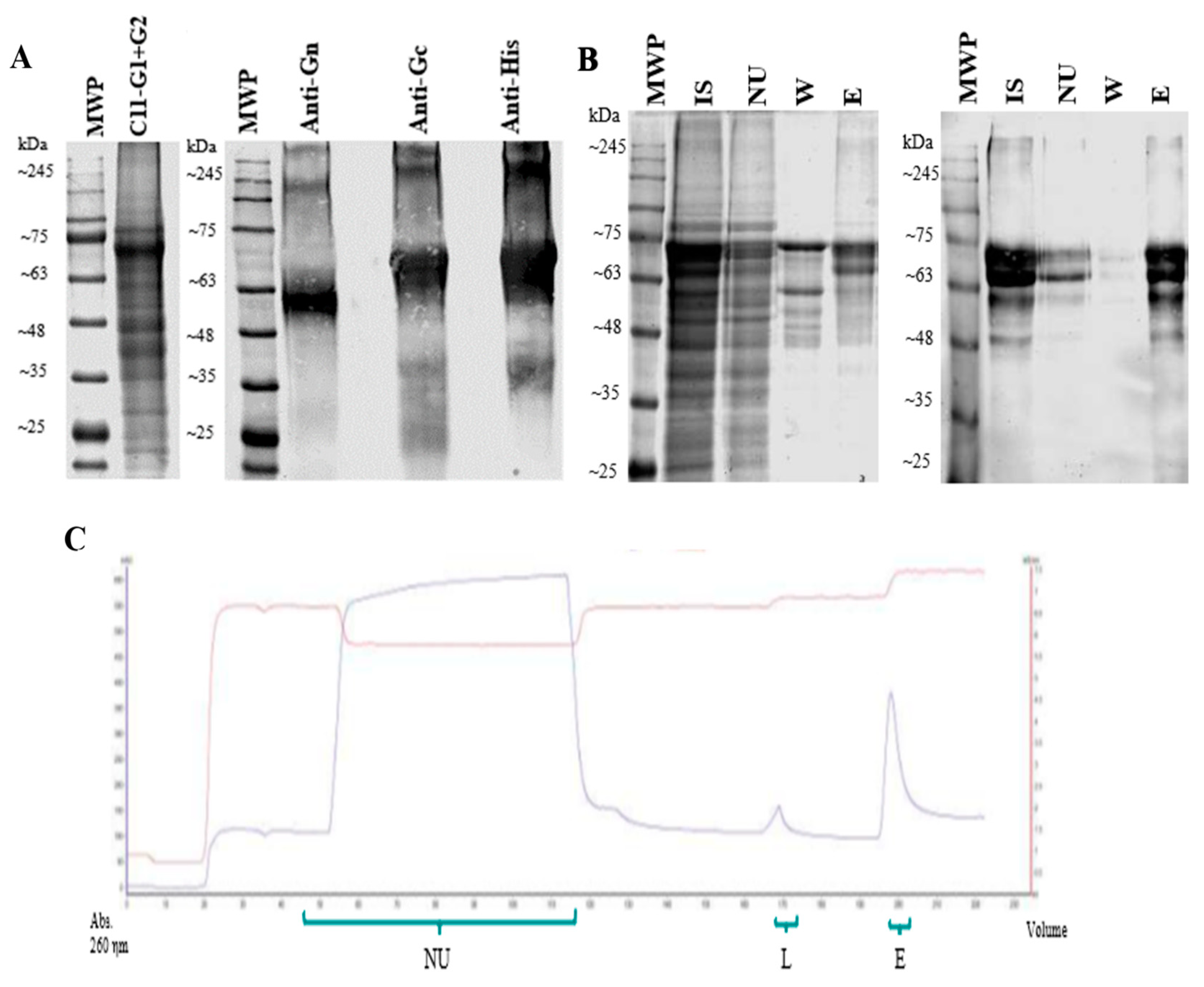

3.3. Production and Characterization of Recombinant sGn and sGc Antigens

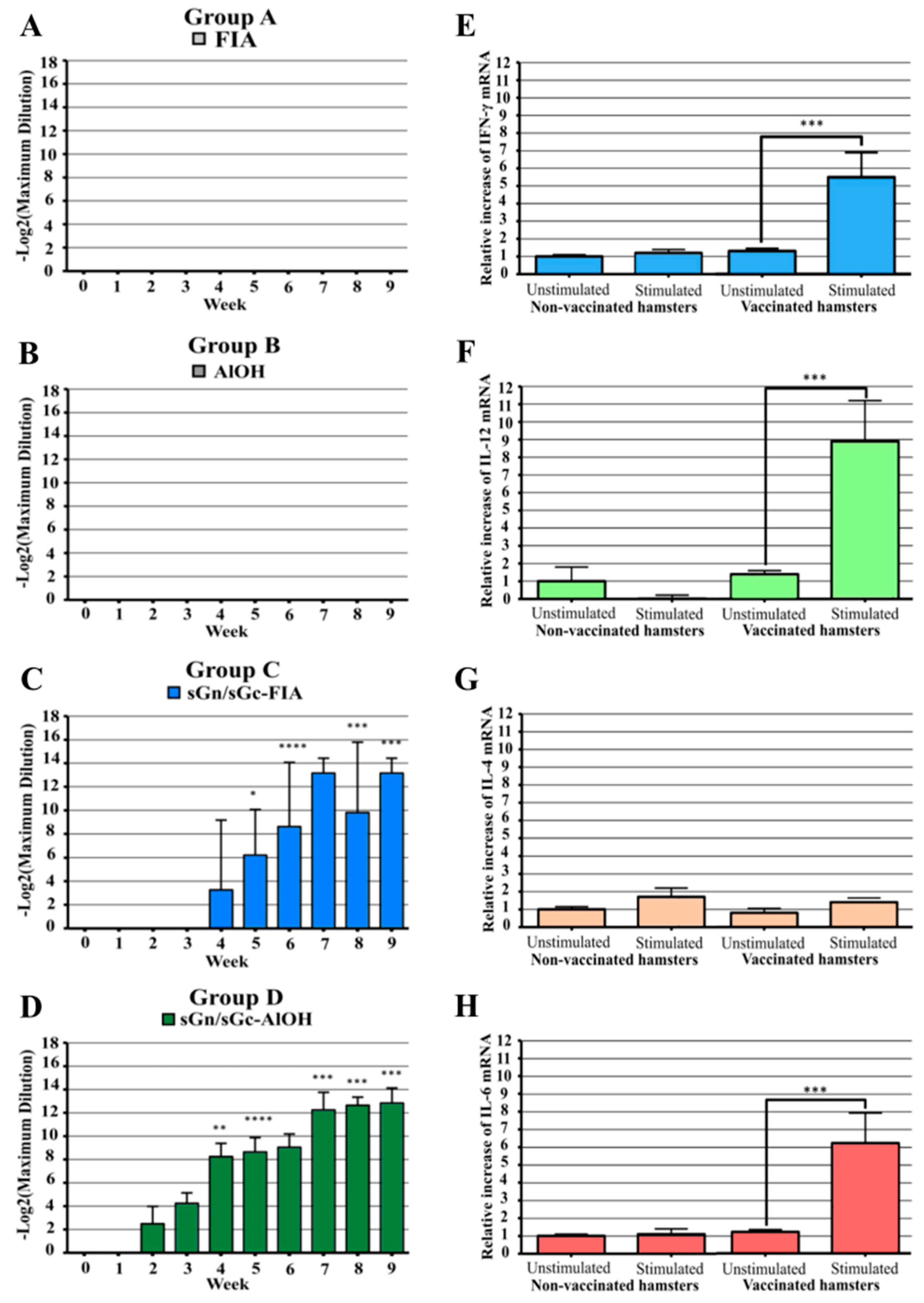

3.4. Evaluation of the Immunogenicity of Recombinant sGn-sGc Antigens in Syrian Hamsters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maes, P.; Alkhovsky, S.V.; Bào, Y.; Beer, M.; Birkhead, M.; et al. Taxonomy of the family Arenaviridae and the order Bunyavirales: update 2018. Springer-Verlag Wien: 2018; Vol. 163, pp 2295-2310.

- Martinez, V.P.; Bellomo, C.; San Juan, J.; Pinna, D.; Forlenza, R.; et al. Person-to-Person Transmission of Andes Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2005; Vol. 11, p 1848.

- Avšič-Županc, T.; Saksida, A.; Korva, M. ;. Hantavirus infections. Elsevier: 2019; Vol. 21, pp e6-e16.

- Bi, Z.; Formenty, P.B.H.; Roth, C.E. ;. Hantavirus Infection: a review and global update. 2008; Vol. 2, pp 003-023.

- Jonsson, C.B.; Hooper, J.; Mertz, G. ;. Treatment of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Elsevier: 2008; Vol. 78, pp 162-169.

- MacNeil, A.; Nichol, S.T.; Spiropoulou, C.F. ;. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Elsevier: 2011; Vol. 162, pp 138-147.

- McCaughey, C.; Hart, C.A. ;. Hantaviruses. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: 2000; Vol. 49, pp 587-599.

- Muranyi, W.; Bahr, U.; Zeier, M.; Van Der Woude, F.J. ;. Hantavirus infection. 2005; Vol. 16, pp 3669-3679.

- Vinh, D.C.; Embil, J.M. ;. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: a concise clinical review. 2009; Vol. 102, pp 620-625.

- Castillo, C.; Naranjo, J.; Sepúlveda, A.; Ossa, G.; Levy, H. ;. Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome Due to Andes Virus in Temuco, Chile: Clinical Experience With 16 Adults. Elsevier: 2001; Vol. 120, pp 548-554.

- Plyusnin, A.; Vapalahti, O.; Vaheri, A. ;. Hantaviruses: Genome structure, expression and evolution. Microbiology Society: 1996; Vol. 77, pp 2677-2687.

- Hepojoki, J.; Strandin, T.; Lankinen, H.; Vaheri, A. ;. Hantavirus structure - Molecular interactions behind the scene. Microbiology Society: 2012; Vol. 93, pp 1631-1644.

- Vaheri, A.; Strandin, T.; Hepojoki, J.; Sironen, T.; Henttonen, H.; et al. Uncovering the mysteries of hantavirus infections. Nature Publishing Group: 2013; Vol. 11, pp 539-550.

- Duehr, J.; McMahon, M.; Williamson, B.; Amanat, F.; Durbin, A.; et al. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against the Gn and the Gc of the andes virus glycoprotein spike complex protect from virus challenge in a preclinical hamster model. American Society for Microbiology: 2020; Vol. 11.

- Acuña, R.; Bignon, E.A.; Mancini, R.; Lozach, P.Y.; Tischler, N.D. ;. Acidification triggers Andes hantavirus membrane fusion and rearrangement of Gc into a stable post-fusion homotrimer. Microbiology Society: 2015; Vol. 96, pp 3192-3197.

- Brown, K.S.; Safronetz, D.; Marzi, A.; Ebihara, H.; Feldmann, H. ;. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus-Based Vaccine Protects Hamsters against Lethal Challenge with Andes Virus. American Society for Microbiology: 2011; Vol. 85, pp 12781-12791.

- Prescott, J.; Debuysscher, B.L.; Brown, K.S.; Feldmann, H. ;. Long-Term Single-Dose Efficacy of a Vesicular Stomatitis Virus-Based Andes Virus Vaccine in Syrian Hamsters. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: 2014; Vol. 6, pp 516-523.

- Safronetz, D.; Hegde, N.R.; Ebihara, H.; Denton, M.; Kobinger, G.P.; et al. Adenovirus Vectors Expressing Hantavirus Proteins Protect Hamsters against Lethal Challenge with Andes Virus. American Society for Microbiology: 2009; Vol. 83, pp 7285-7295.

- Brocato, R.; Josleyn, M.; Ballantyne, J.; Vial, P.; Hooper, J.W. ;. DNA Vaccine-Generated Duck Polyclonal Antibodies as a Postexposure Prophylactic to Prevent Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS). Public Library of Science: 2012; Vol. 7, p e35996.

- Custer, D.M.; Thompson, E.; Schmaljohn, C.S.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Hooper, J.W. ;. Active and Passive Vaccination against Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome with Andes Virus M Genome Segment-Based DNA Vaccine. American Society for Microbiology (ASM): 2003; Vol. 77, p 9894.

- Haese, N.; Brocato, R.L.; Henderson, T.; Nilles, M.L.; Kwilas, S.A.; et al. Antiviral Biologic Produced in DNA Vaccine/Goose Platform Protects Hamsters Against Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome When Administered Post-exposure. Public Library of Science: 2015; Vol. 9, p e0003803.

- Hooper, J.W.; Brocato, R.L.; Kwilas, S.A.; Hammerbeck, C.D.; Josleyn, M.D.; et al. DNA vaccine-derived human IgG produced in transchromosomal bovines protect in lethal models of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. American Association for the Advancement of Science: 2014; Vol. 6.

- Hooper, J.W.; Custer, D.M.; Thompson, E.; Schmaljohn, C.S. ;. DNA Vaccination with the Hantaan Virus M Gene Protects Hamsters against Three of Four HFRS Hantaviruses and Elicits a High-Titer Neutralizing Antibody Response in Rhesus Monkeys. American Society for Microbiology: 2001; Vol. 75, pp 8469-8477.

- Brocato, R.L.; Hooper, J.W. ;. Progress on the prevention and treatment of hantavirus disease. MDPI AG: 2019; Vol. 11.

- de Carvalho Nicacio, C.; Gonzalez Della Valle, M.; Padula, P.; Björling, E.; Plyusnin, A.; et al. Cross-Protection against Challenge with Puumala Virus after Immunization with Nucleocapsid Proteins from Different Hantaviruses. American Society for Microbiology: 2002; Vol. 76, pp 6669-6677.

- Martinez, V.P.; Padula, P.J. ;. Induction of protective immunity in a syrian hamster model against a cytopathogenic strain of andes virus. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: 2012; Vol. 84, pp 87-95.

- Yin, J.; Li, G.; Ren, X.; Herrler, G. ;. Select what you need: A comparative evaluation of the advantages and limitations of frequently used expression systems for foreign genes. Elsevier: 2007; Vol. 127, pp 335-347.

- Schmidt, F.R. ;. Recombinant expression systems in the pharmaceutical industry. Springer: 2004; Vol. 65, pp 363-372.

- Demain, A.L.; Vaishnav, P. ;. Production of recombinant proteins by microbes and higher organisms. Elsevier: 2009; Vol. 27, pp 297-306.

- Andersen, D.C.; Krummen, L. ;. Recombinant protein expression for therapeutic applications. Elsevier Current Trends: 2002; Vol. 13, pp 117-123.

- Duckert, P.; Brunak, S.; Blom, N. ;. Prediction of proprotein convertase cleavage sites. Oxford Academic: 2004; Vol. 17, pp 107-112.

- Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Von Heijne, G.; Krogh, A. ; A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. 1998.

- Petersen, T.N.; Brunak, S.; Von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. ;. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature Publishing Group: 2011; Vol. 8, pp 785-786.

- Gupta, R.; Brunak, S. ;. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. 2002; 10.1142/9789812799623_0029pp 310-322.

- Pichia Protocols. Cregg, J.M. Pichia Protocols. Cregg, J.M.,, Eds. Humana Press: 2007; Vol. 389.

- Engvall, E.; Perlmann, P. ;. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Pergamon: 1971; Vol. 8, pp 871-874.

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. ;. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Academic Press Inc.: 2001; Vol. 25, pp 402-408.

- Wong, M.L.; Medrano, J.F. ;. Real-Time PCR for mRNA Quantitation. Taylor & Francis: 2005; Vol. 39, pp 75-85.

- Beltrán-Ortiz, C.E.; Starck-Mendez, M.F.; Fernández, Y.; Farnós, O.; González, E.E.; et al. Expression and purification of the surface proteins from Andes virus. Academic Press: 2017; Vol. 139, pp 63-70.

- Ruusala, A.; Persson, R.; Schmauohn, C.S.; Pettersson, R.F. ;. Coexpression of the membrane glycoproteins G1 and G2 of Hantaan virus is required for targeting to the Golgi complex. Academic Press: 1992; Vol. 186, pp 53-64.

- Hepojoki, J.; Strandin, T.; Vaheri, A.; Lankinen, H. ;. Interactions and Oligomerization of Hantavirus Glycoproteins. American Society for Microbiology: 2010; Vol. 84, pp 227-242.

- Deyde, V.M.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Chase, J.; Otteson, E.W. ; ; St. Jeor, S.C.;. Interactions and trafficking of Andes and Sin Nombre Hantavirus glycoproteins G1 and G2. Academic Press: 2005; Vol. 331, pp 307-315.

- Cifuentes-Muñoz, N.; Salazar-Quiroz, N.; Tischler, N.D. ;. Hantavirus Gn and Gc Envelope Glycoproteins: Key Structural Units for Virus Cell Entry and Virus Assembly. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: 2014; Vol. 6, pp 1801-1822.

- Rissanen, I.; Stass, R.; Zeltina, A.; Li, S.; Hepojoki, J.; et al. Structural Transitions of the Conserved and Metastable Hantaviral Glycoprotein Envelope. American Society for Microbiology: 2017; Vol. 91.

- Sperber, H.S.; Welke, R.W.; Petazzi, R.A.; Bergmann, R.; Schade, M.; et al. Self-association and subcellular localization of Puumala hantavirus envelope proteins. Nature Publishing Group: 2019; Vol. 9, pp 1-15.

- Battisti, A.J.; Chu, Y.-K.; Chipman, P.R.; Kaufmann, B.; Jonsson, C.B.; et al. Structural Studies of Hantaan Virus. American Society for Microbiology: 2011; Vol. 85, pp 835-841.

- Acuña, R.; Cifuentes-Muñoz, N.; Márquez, C.L.; Bulling, M.; Klingström, J.; et al. Hantavirus Gn and Gc Glycoproteins Self-Assemble into Virus-Like Particles. American Society for Microbiology: 2014; Vol. 88, pp 2344-2348.

- Levanov, L.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, R.P.; Lundkvist, Å.; Vapalahti, O.; Plyusnin, A. ;. Defining of MAbs-neutralizing sites on the surface glycoproteins Gn and Gc of a hantavirus using vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotypes and site-directed mutagenesis. Microbiology Society: 2019; Vol. 100, pp 145-155.

- Li, S.; Rissanen, I.; Zeltina, A.; Hepojoki, J.; Raghwani, J.; et al. A Molecular-Level Account of the Antigenic Hantaviral Surface. Elsevier B.V.: 2016; Vol. 15, pp 959-967.

- Shi, X.; Elliott, R.M. ;. Analysis of N-Linked Glycosylation of Hantaan Virus Glycoproteins and the Role of Oligosaccharide Side Chains in Protein Folding and Intracellular Trafficking. American Society for Microbiology: 2004; Vol. 78, pp 5414-5422.

- Shental-Bechor, D.; Levy, Y. ;. Effect of glycosylation on protein folding: A close look at thermodynamic stabilization. National Academy of Sciences: 2008; Vol. 105, pp 8256-8261.

- Shental-Bechor, D.; Levy, Y. ;. Folding of glycoproteins: toward understanding the biophysics of the glycosylation code. Elsevier Current Trends: 2009; Vol. 19, pp 524-533.

- Hilleman, M.R. ;. Yeast recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Springer-Verlag: 1987; Vol. 15, pp 3-7.

- Barr, E.; Tamms, G. ;. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine. Oxford Academic: 2007; Vol. 45, pp 609-617.

- Chang, J.C.C.; Diveley, J.P.; Savary, J.R.; Jensen, F.C. ;. Adjuvant activity of incomplete Freund's adjuvant. Elsevier: 1998; Vol. 32, pp 173-186.

- O'Hagan, D.T.; Ott, G.S.; Van Nest, G.; Rappuoli, R.; Del Giudice, G. ;. The history of MF59® adjuvant: a phoenix that arose from the ashes. Taylor & Francis: 2013; Vol. 12, pp 13-30.

- Mbow, M.L.; De Gregorio, E.; Ulmer, J.B. ;. Alum's adjuvant action: grease is the word. Nature Publishing Group: 2011; Vol. 17, pp 415-416.

- Mbow, M.L.; De Gregorio, E.; Valiante, N.M.; Rappuoli, R. ;. New adjuvants for human vaccines. Elsevier Current Trends: 2010; Vol. 22, pp 411-416.

- Siddiqui, M.A.A.; Perry, C.M. ;. Human papillomavirus quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine (Gardasil®). Springer: 2006; Vol. 66, pp 1263-1271.

- Szarewski, A. ;. HPV vaccine: Cervarix. Taylor & Francis: 2010; Vol. 10, pp 477-487.

- Hooper, J.W.; Larsen, T.; Custer, D.M.; Schmaljohn, C.S. ;. A Lethal Disease Model for Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome. Academic Press: 2001; Vol. 289, pp 6-14.

- Milazzo, M.L.; Eyzaguirre, E.J.; Molina, C.P.; Fulhorst, C.F. ;. Maporal Viral Infection in the Syrian Golden Hamster: A Model of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome. Oxford Academic: 2002; Vol. 186, pp 1390-1395.

- Miao, J.; Chard, L.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. ;. Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study on Infectious Diseases. Frontiers Media S.A.: 2019; Vol. 10, p 457882.

- Dienz, O.; Rincon, M. ;. The effects of IL-6 on CD4 T cell responses. Academic Press: 2009; Vol. 130, pp 27-33.

- O'Garra, A. ;. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Cell Press: 1998; Vol. 8, pp 275-283.

- O'Garra, A.; Arai, N. ;. The molecular basis of T helper 1 and T helper 2 cell differentiation. Elsevier: 2000; Vol. 10, pp 542-550.

- Sieling, P.A.; Wang, X.H.; Gately, M.K.; Oliveros, J.L.; McHugh, T.; et al. IL-12 regulates T helper type 1 cytokine responses in human infectious disease. American Association of Immunologists: 1994; Vol. 153, pp 3639-3647.

- Zivcec, M.; Safronetz, D.; Haddock, E.; Feldmann, H.; Ebihara, H. ;. Validation of assays to monitor immune responses in the Syrian golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus). Elsevier: 2011; Vol. 368, pp 24-35.

- Kim, S.H.; Jang, Y.S. ;. The development of mucosal vaccines for both mucosal and systemic immune induction and the roles played by adjuvants. The Korean Vaccine Society: 2017; Vol. 6, pp 15-21.

- McElrath, M.J. ;. Adjuvants: Tailoring humoral immune responses. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: 2017; Vol. 12, pp 278-284.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, S. ;. Effect of vaccine administration modality on immunogenicity and efficacy. Informa Healthcare: 2015; Vol. 14, pp 1509-1523.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).