Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Viruses

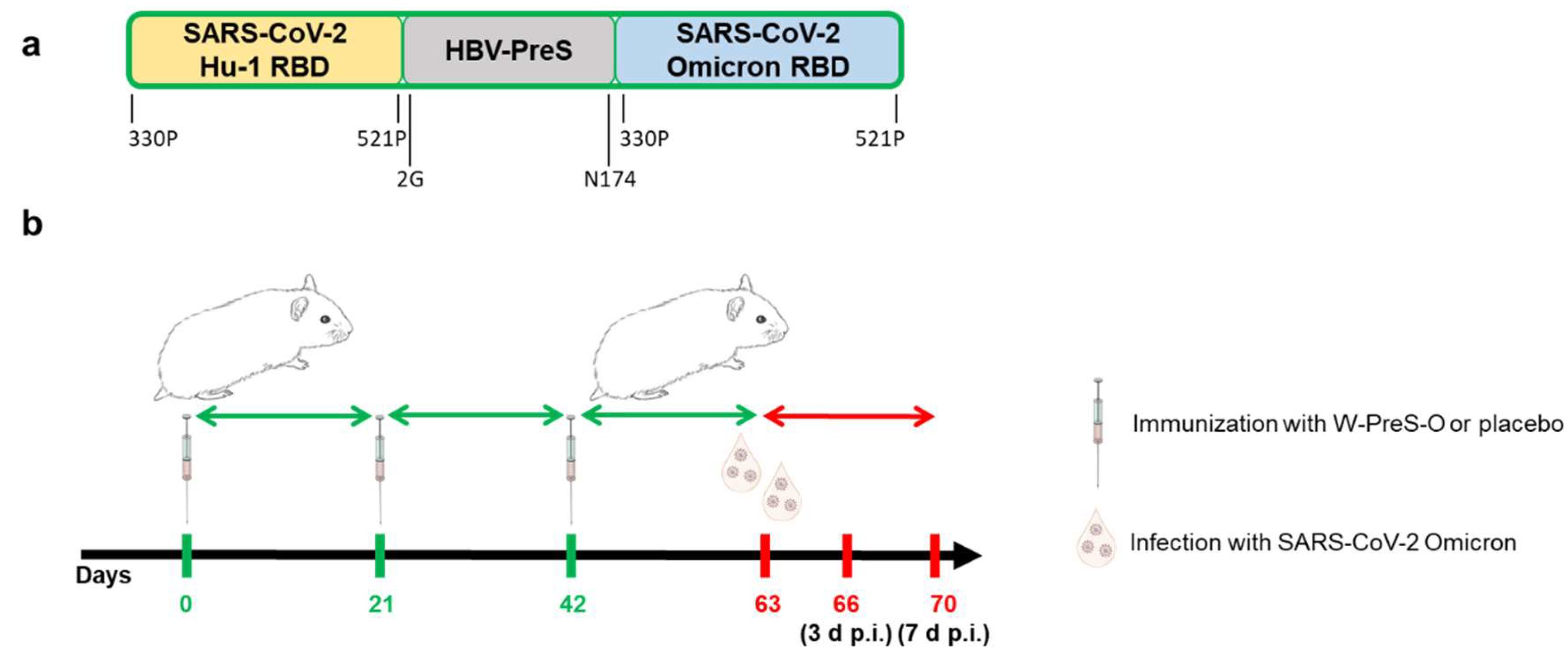

2.2. Immunization of Animals and Infection Model

2.3. Determination of Viral Loads

2.4. Virus Neutralization Test

2.5. Histological Examination

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

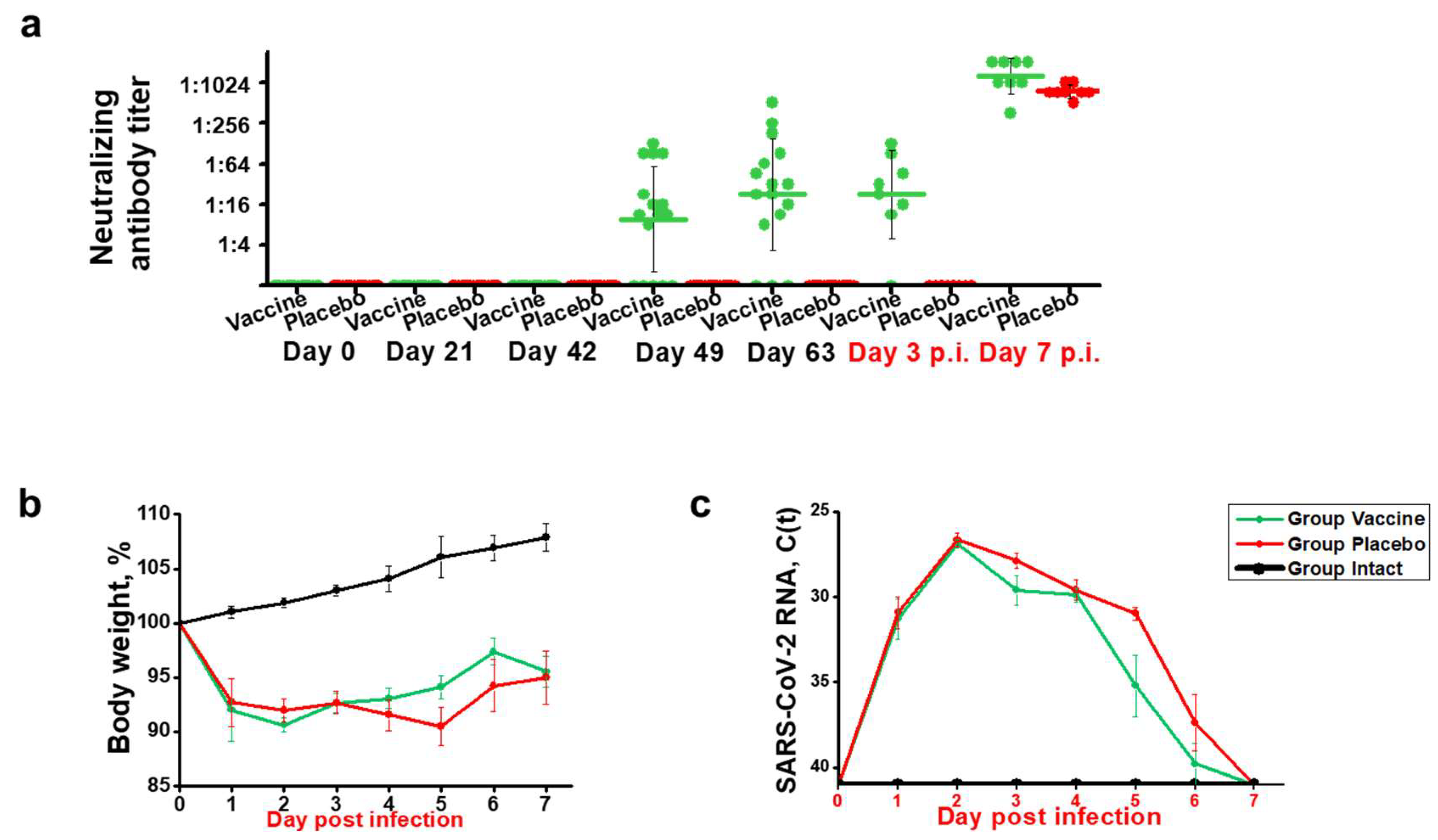

3.1. Immunization with W-PreS-O induces SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-Neutralizing Antibody Titers in Syrian Hamsters

3.2. Recovery after SARS-CoV-2 Infection was Faster in Animals Immunized with W-PreS-O than in Placebo-Treated Animals

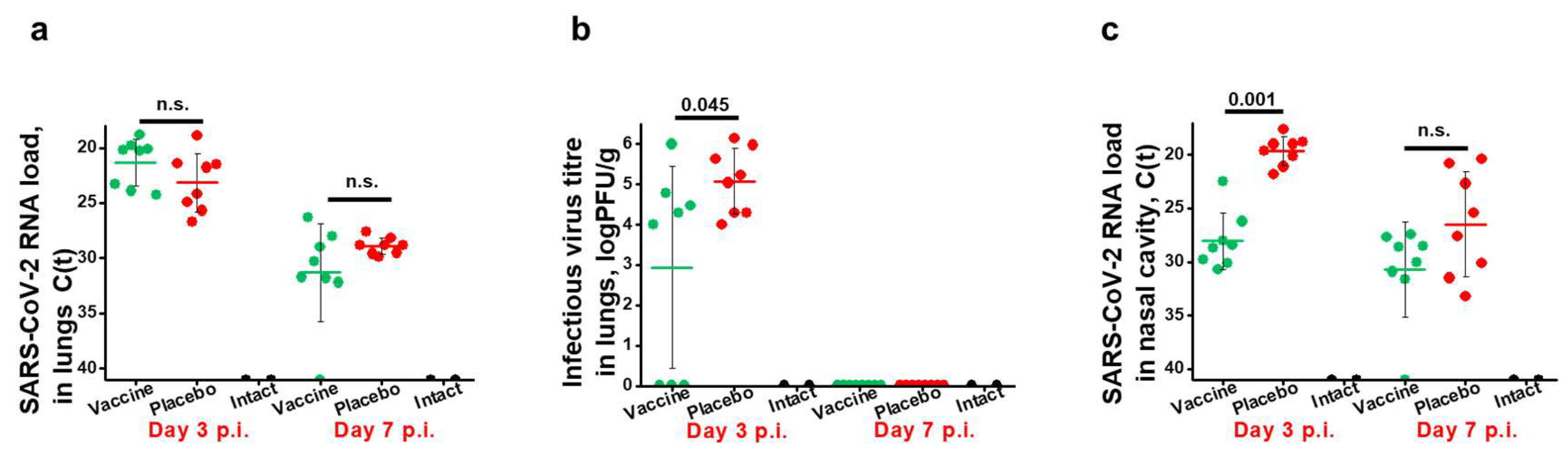

3.3. Effects of Vaccination with W-PreS-O on Viral Loads in the Upper and Lower Respiratory Tract and Presence of Infectious Virus in the Lungs of Infected Animals

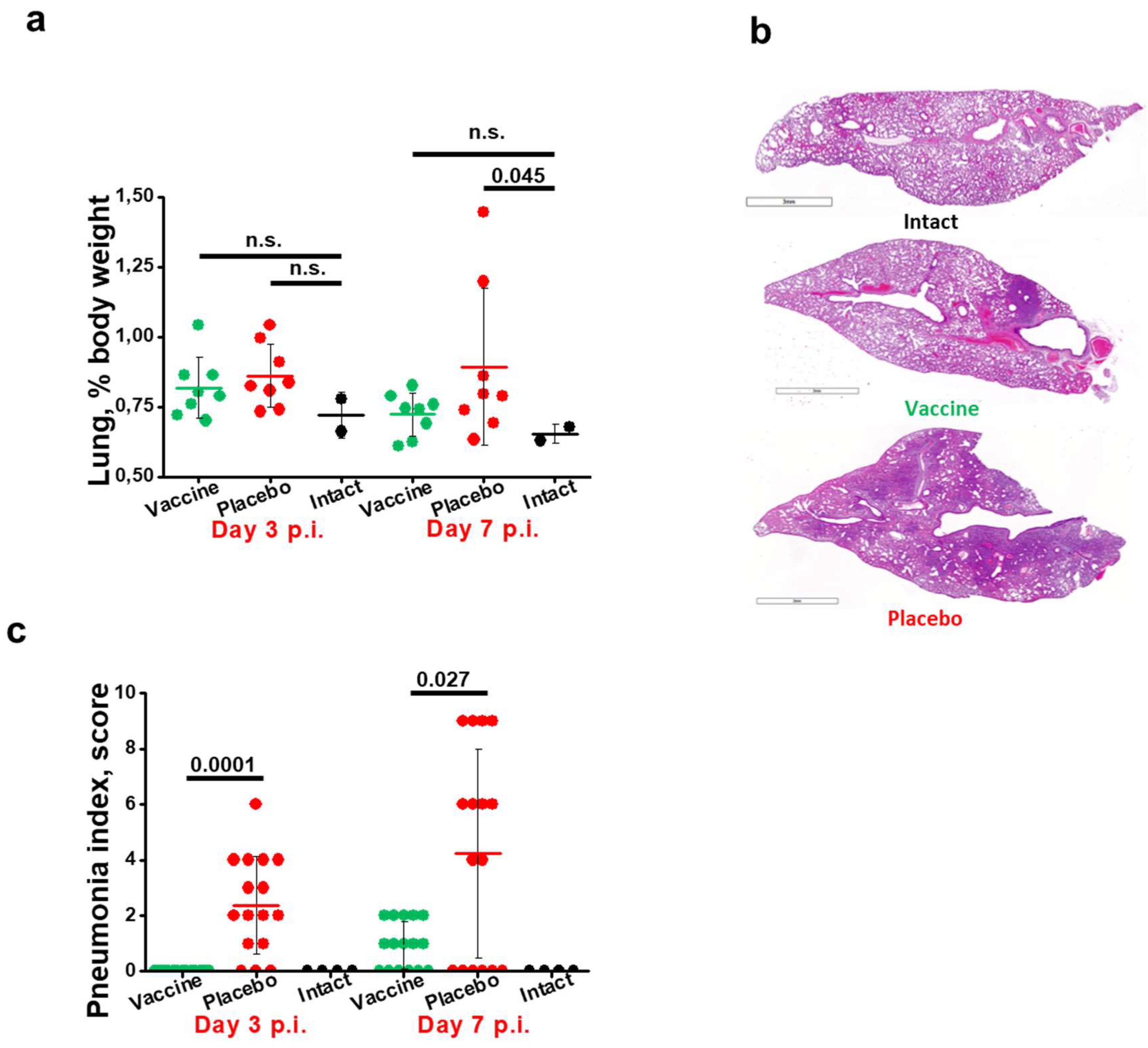

3.4. Immunization with W-PreS-O Strongly Protects against Lung Damage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.Q.; He, J.X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.L.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1708-1720. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Cao, Y.Y.; Lu, X.X.; Zhang, J.J.; Du, H.; Yan, Y.Q.; Akdis, C.A.; Gao, Y.D. Eleven faces of coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy 2020, 75, 1699-1709. [CrossRef]

- Nesteruk, I. Endemic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14841. [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, J.O.; Pakala, S.B.; Vestal, G.; Shilts, M.H.; Brown, H.M.; Bowen, S.M.; Strickland, B.A.; Williams, T.; Mallal, S.A.; Jones, I.D.; et al. COVID-19 severity from Omicron and Delta SARS-CoV-2 variants. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022, 16, 832-836. [CrossRef]

- Menni, C.; Valdes, A.M.; Polidori, L.; Antonelli, M.; Penamakuri, S.; Nogal, A.; Louca, P.; May, A.; Figueiredo, J.C.; Hu, C.; et al. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: A prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet 2022, 399, 1618-1624. [CrossRef]

- Fericean, R.M.; Oancea, C.; Reddyreddy, A.R.; Rosca, O.; Bratosin, F.; Bloanca, V.; Citu, C.; Alambaram, S.; Vasamsetti, N.G.; Dumitru, C. Outcomes of Elderly Patients Hospitalized with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron B.1.1.529 Variant: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [CrossRef]

- Nori, W.; Ghani Zghair, M.A. Omicron targets upper airways in pediatrics, elderly and unvaccinated population. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 12062-12065. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Ai, J.; Shen, L.; Lin, K.; Yuan, G.; Sheng, X.; Jin, X.; Deng, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. Identification of CKD, bedridden history and cancer as higher-risk comorbidities and their impact on prognosis of hospitalized Omicron patients: A multi-centre cohort study. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022, 11, 2501-2509. [CrossRef]

- Mongin, D.; Bürgisser, N.; Laurie, G.; Schimmel, G.; Vu, D.L.; Cullati, S.; Courvoisier, D.S. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 prior infection and mRNA vaccination on contagiousness and susceptibility to infection. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5452. [CrossRef]

- Bobrovitz, N.; Ware, H.; Ma, X.; Li, Z.; Hosseini, R.; Cao, C.; Selemon, A.; Whelan, M.; Premji, Z.; Issa, H.; et al. Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: A systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, 556-567. [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H.; Ye, Q. The emergence and epidemic characteristics of the highly mutated SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 2376-2383. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, L.B.; Foster, C.; Rawlinson, W.; Tedla, N.; Bull, R.A. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants BA.1 to BA.5: Implications for immune escape and transmission. Rev Med Virol 2022, 32, e2381. [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, P.; Tulaeva, I.; Borochova, K.; Kratzer, B.; Trapin, D.; Kropfmüller, A.; Pickl, W.F.; Valenta, R. Omicron: A SARS-CoV-2 variant of real concern. Allergy 2022, 77, 1616-1620. [CrossRef]

- Uemura, K.; Kanata, T.; Ono, S.; Michihata, N.; Yasunaga, H. The disease severity of COVID-19 caused by Omicron variants: A brief review. Ann Clin Epidemiol 2023, 5, 31-36. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; St Denis, K.J.; Hoelzemer, A.; Lam, E.C.; Nitido, A.D.; Sheehan, M.L.; Berrios, C.; Ofoman, O.; Chang, C.C.; Hauser, B.M.; et al. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell 2022, 185, 457-466.e454. [CrossRef]

- Wolter, N.; Jassat, W.; Walaza, S.; Welch, R.; Moultrie, H.; Groome, M.; Amoako, D.G.; Everatt, J.; Bhiman, J.N.; Scheepers, C.; et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in South Africa: A data linkage study. Lancet 2022, 399, 437-446. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Jian, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, J.; An, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; et al. Imprinted SARS-CoV-2 humoral immunity induces convergent Omicron RBD evolution. Nature 2023, 614, 521-529. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; He, Y.; Liu, H.; Shang, Y.; Guo, G. Potential immune evasion of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Omicron variants. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1339660. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S. Insight into SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant immune escape possibility and variant independent potential therapeutic opportunities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13285. [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; Robertson, D.L. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 162-177. [CrossRef]

- Zak, A.J.; Hoang, T.; Yee, C.M.; Rizvi, S.M.; Prabhu, P.; Wen, F. Pseudotyping Improves the Yield of Functional SARS-CoV-2 Virus-like Particles (VLPs) as Tools for Vaccine and Therapeutic Development. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Huang, H.; Yu, C.; Sun, C.; Ma, J.; Kong, D.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, S.; Lu, J.; et al. A spike-trimer protein-based tetravalent COVID-19 vaccine elicits enhanced breadth of neutralization against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants and other variants. Sci China Life Sci 2023, 66, 1818-1830. [CrossRef]

- Chau, E.C.T.; Kwong, T.C.; Pang, C.K.; Chan, L.T.; Chan, A.M.L.; Yao, X.; Tam, J.S.L.; Chan, S.W.; Leung, G.P.H.; Tai, W.C.S.; et al. A Novel Probiotic-Based Oral Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant B.1.1.529. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, P.; Kratzer, B.; Sehgal, A.N.A.; Ohradanova-Repic, A.; Gebetsberger, L.; Tajti, G.; Focke-Tejkl, M.; Schaar, M.; Fuhrmann, V.; Petrowitsch, L.; et al. Vaccine Based on Recombinant Fusion Protein Combining Hepatitis B Virus PreS with SARS-CoV-2 Wild-Type- and Omicron-Derived Receptor Binding Domain Strongly Induces Omicron-Neutralizing Antibodies in a Murine Model. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Blain, H.; Tuaillon, E.; Gamon, L.; Pisoni, A.; Miot, S.; Delpui, V.; Si-Mohamed, N.; Niel, C.; Rolland, Y.; Montes, B.; et al. Receptor binding domain-IgG levels correlate with protection in residents facing SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 outbreaks. Allergy 2022, 77, 1885-1894. [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, P.; Niespodziana, K.; Stiasny, K.; Sahanic, S.; Tulaeva, I.; Borochova, K.; Dorofeeva, Y.; Schlederer, T.; Sonnweber, T.; Hofer, G.; et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 requires antibodies against conformational receptor-binding domain epitopes. Allergy 2022, 77, 230-242. [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, P.; Ohradanova-Repic, A.; Valenta, R. Importance, Applications and Features of Assays Measuring SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.P.C.; Quadros, H.C.; Fernandes, A.M.S.; Gonçalves, L.P.; Badaró, R.; Soares, M.B.P.; Machado, B.A.S. An Overview of the Conventional and Novel Methods Employed for SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Measurement. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Caldera-Crespo, L.A.; Paidas, M.J.; Roy, S.; Schulman, C.I.; Kenyon, N.S.; Daunert, S.; Jayakumar, A.R. Experimental Models of COVID-19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 792584. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.K.; Lindsey, J.R.; Davis, J.K. Requirements and selection of an animal model. Isr J Med Sci 1987, 23, 551-555.

- Miao, J.; Chard, L.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study on Infectious Diseases. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2329. [CrossRef]

- Schaecher, S.R.; Stabenow, J.; Oberle, C.; Schriewer, J.; Buller, R.M.; Sagartz, J.E.; Pekosz, A. An immunosuppressed Syrian golden hamster model for SARS-CoV infection. Virology 2008, 380, 312-321. [CrossRef]

- Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Nakajima, N.; Ichiko, Y.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Noda, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study of Human Influenza Virus Infection. J Virol 2018, 92. [CrossRef]

- Frere, J.J.; Serafini, R.A.; Pryce, K.D.; Zazhytska, M.; Oishi, K.; Golynker, I.; Panis, M.; Zimering, J.; Horiuchi, S.; Hoagland, D.A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters and humans results in lasting and unique systemic perturbations after recovery. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14, eabq3059. [CrossRef]

- Sia, S.F.; Yan, L.M.; Chin, A.W.H.; Fung, K.; Choy, K.T.; Wong, A.Y.L.; Kaewpreedee, P.; Perera, R.; Poon, L.L.M.; Nicholls, J.M.; et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature 2020, 583, 834-838. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497-506. [CrossRef]

- Castellan, M.; Zamperin, G.; Franzoni, G.; Foiani, G.; Zorzan, M.; Drzewnioková, P.; Mancin, M.; Brian, I.; Bortolami, A.; Pagliari, M.; et al. Host Response of Syrian Hamster to SARS-CoV-2 Infection including Differences with Humans and between Sexes. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, A.; Chen, F.; Li, S.; Guan, X.; Lv, C.; Tang, T.; He, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 immunity in animal models. Cell Mol Immunol 2024, 21, 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, P.J.; Iida, S.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Maemura, T.; Kiso, M.; Scheaffer, S.M.; Darling, T.L.; Joshi, A.; Loeber, S.; Singh, G.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron virus causes attenuated disease in mice and hamsters. Nature 2022, 603, 687-692. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Ye, Z.W.; Liang, R.; Tang, K.; Zhang, A.J.; Lu, G.; Ong, C.P.; Man Poon, V.K.; Chan, C.C.; Mok, B.W.; et al. Pathogenicity, transmissibility, and fitness of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in Syrian hamsters. Science 2022, 377, 428-433. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, G. Omicron shots are coming-with lots of questions. Science 2022, 377, 1029-1030. [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, P.; Kratzer, B.; Tulaeva, I.; Niespodziana, K.; Ohradanova-Repic, A.; Gebetsberger, L.; Borochova, K.; Garner-Spitzer, E.; Trapin, D.; Hofer, G.; et al. Vaccine based on folded receptor binding domain-PreS fusion protein with potential to induce sterilizing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 variants. Allergy 2022, 77, 2431-2445. [CrossRef]

- Valenta, R.; Campana, R.; Niederberger, V. Recombinant allergy vaccines based on allergen-derived B cell epitopes. Immunol Lett 2017, 189, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, C.; Schöneweis, K.; Georgi, F.; Weber, M.; Niederberger, V.; Zieglmayer, P.; Niespodziana, K.; Trauner, M.; Hofer, H.; Urban, S.; et al. Immunotherapy With the PreS-based Grass Pollen Allergy Vaccine BM32 Induces Antibody Responses Protecting Against Hepatitis B Infection. EBioMedicine 2016, 11, 58-67. [CrossRef]

- Kärber, G. Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 1931, 162, 480-483. [CrossRef]

- Boon, J.; Soudani, N.; Bricker, T.; Darling, T.; Seehra, K.; Patel, N.; Guebre-Xabier, M.; Smith, G.; Suthar, M.; Ellebedy, A.; et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of XBB.1.5 rS vaccine against EG.5.1 variant of SARS-CoV-2 in Syrian hamsters. Res Sq 2024. [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.R.G.; Walker, J.L.; Scharton, D.; Rafael, G.H.; Mitchell, B.M.; Reyna, R.A.; de Souza, W.M.; Liu, J.; Walker, D.H.; Plante, J.A.; et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccine boosters against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariant BA.5 in male Syrian hamsters. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4260. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhou, R.; Tang, B.; Chan, J.F.; Luo, M.; Peng, Q.; Yuan, S.; Liu, H.; Mok, B.W.; Chen, B.; et al. A broadly neutralizing antibody protects Syrian hamsters against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron challenge. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3589. [CrossRef]

- van Doremalen, N.; Schulz, J.E.; Adney, D.R.; Saturday, T.A.; Fischer, R.J.; Yinda, C.K.; Thakur, N.; Newman, J.; Ulaszewska, M.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) or nCoV-19-Beta (AZD2816) protect Syrian hamsters against Beta Delta and Omicron variants. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4610. [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, P.J.; Uraki, R.; Kuroda, M.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Yamayoshi, S.; Ito, M.; Kawaoka, Y. Transmission and re-infection of Omicron variant XBB.1.5 in hamsters. EBioMedicine 2023, 93, 104677. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.D.; Mohandas, S.; Shete, A.; Sapkal, G.; Deshpande, G.; Kumar, A.; Wakchaure, K.; Dighe, H.; Jain, R.; Ganneru, B.; et al. Protective efficacy of COVAXIN® against Delta and Omicron variants in hamster model. iScience 2022, 25, 105178. [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.A.; Kissler, S.M.; Fauver, J.R.; Mack, C.; Tai, C.G.; Samant, R.M.; Connolly, S.; Anderson, D.J.; Khullar, G.; MacKay, M.; et al. Quantifying the impact of immune history and variant on SARS-CoV-2 viral kinetics and infection rebound: A retrospective cohort study. Elife 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).