Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

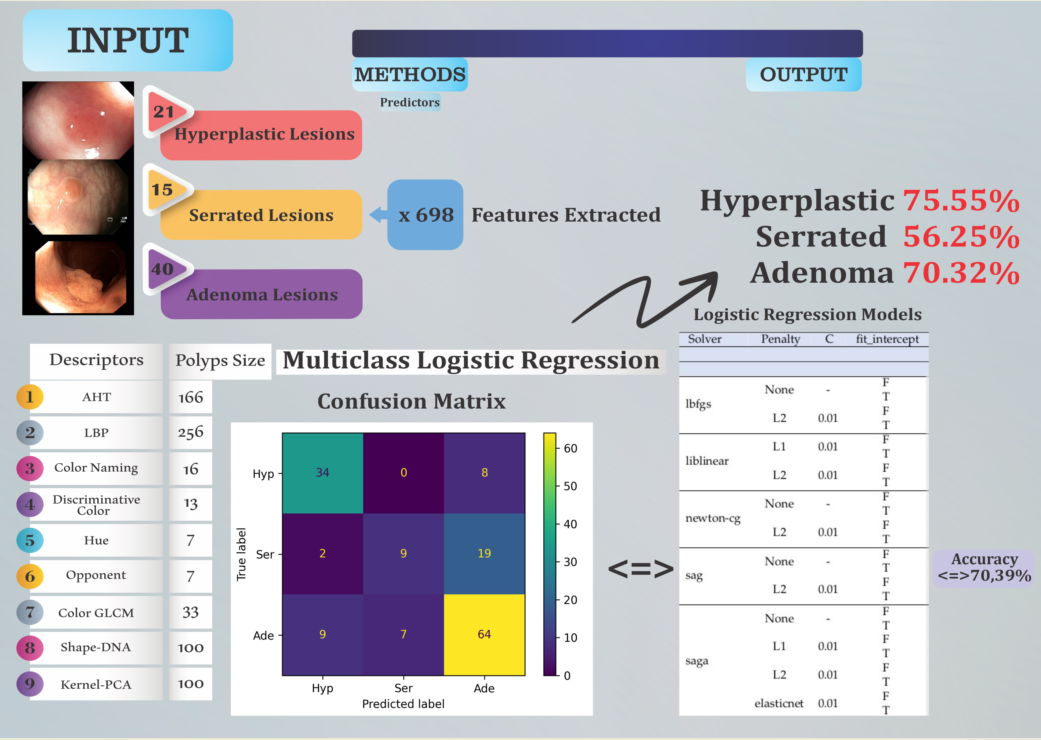

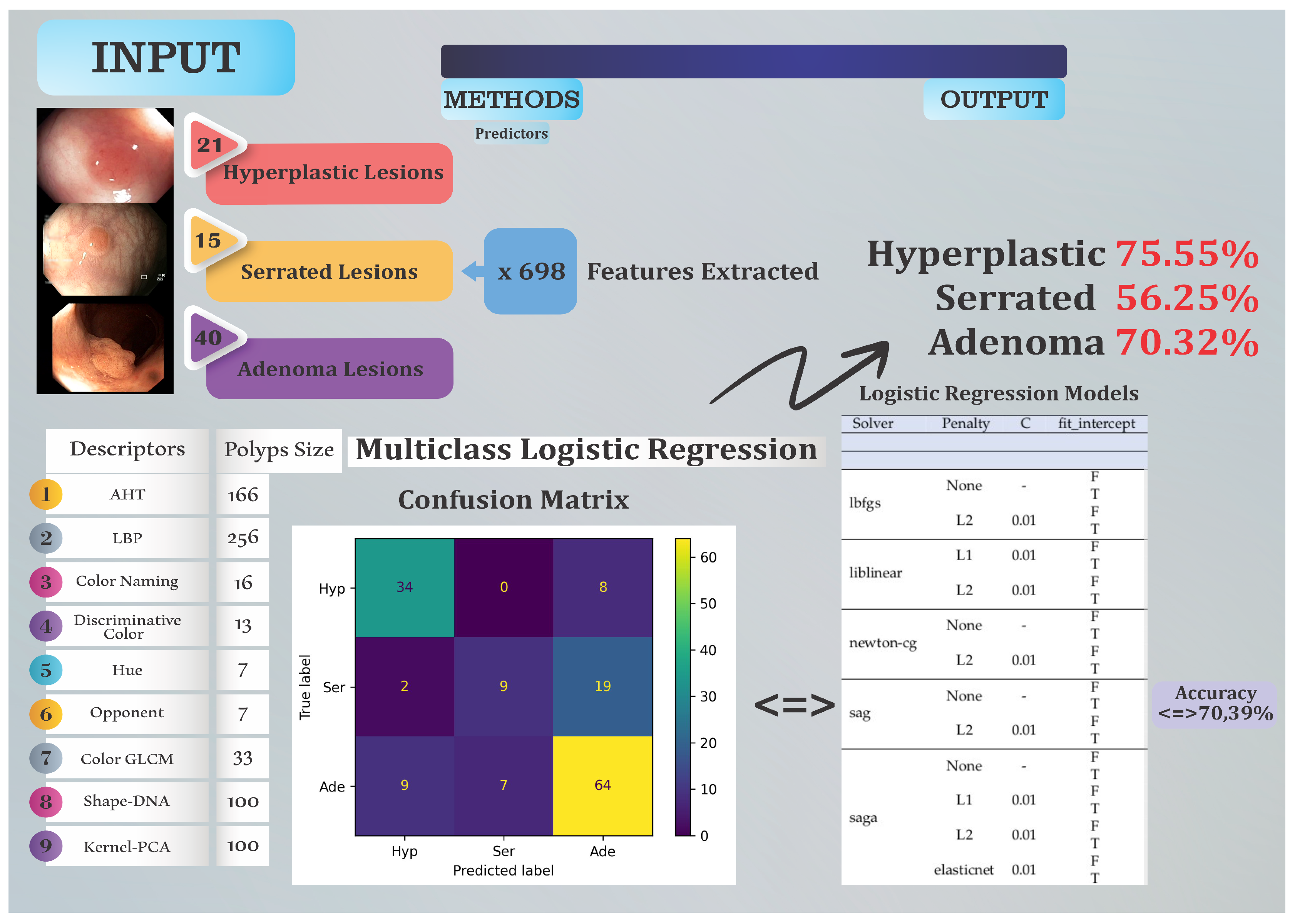

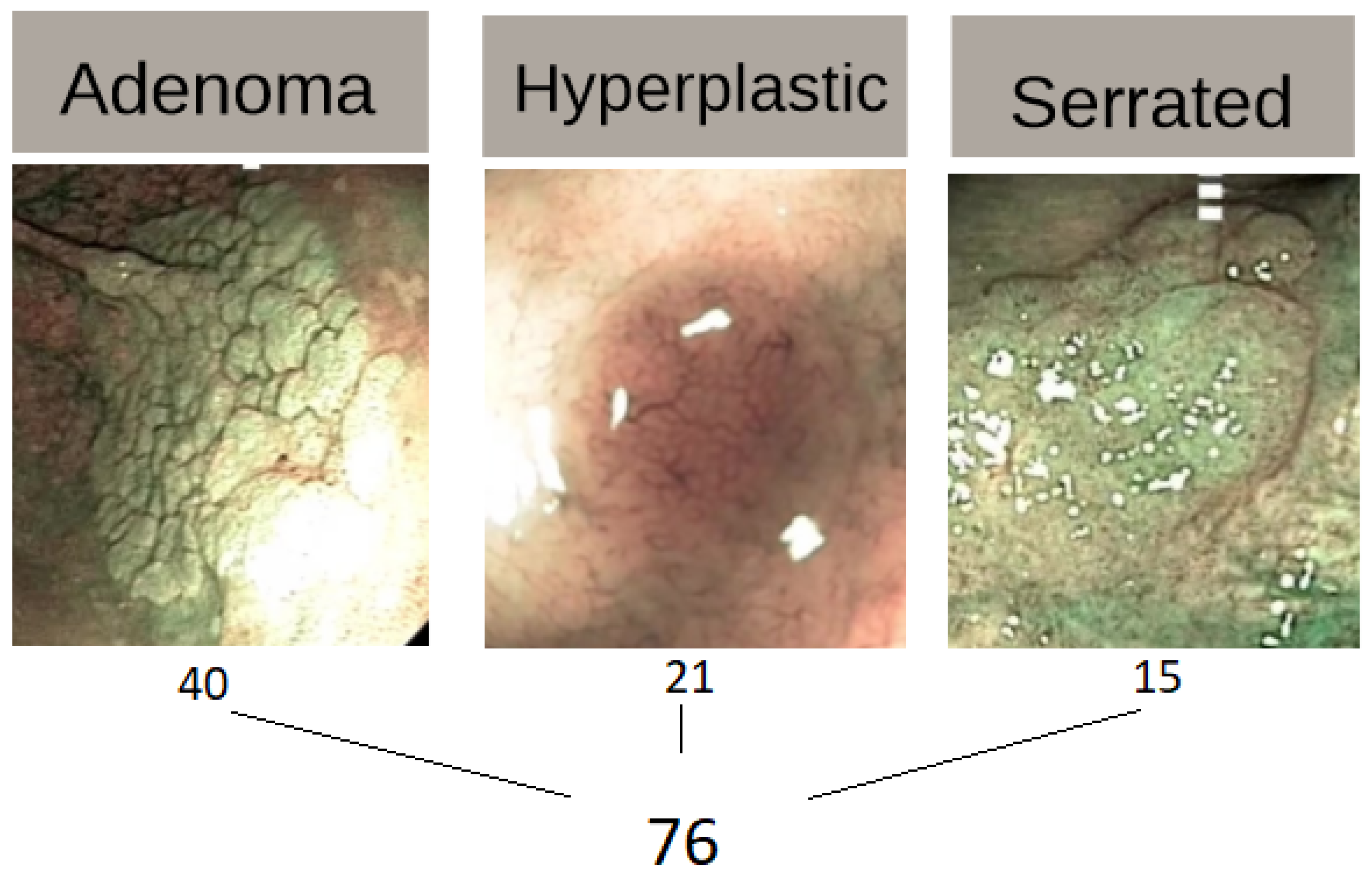

2.1. Colonoscopy Dataset

- 1st column: name of the lesion;

- 2nd column: class of lesion (hyperplastic - 1; serrated - 2; adenoma - 3);

- 3rd column: type of light used (one row with White Light (WL) and the other with Narrow Band Imaging (NBI), resulting in 152 rows instead of just 76);

- 4th column until the last one (701): features.

2.2. Feature Extraction

- Amplitude Histogram of Texture (AHT) - 166 features. This texture descriptor captures information about the distribution of amplitudes in images.

- Local Binary Patterns (LBP) - 256 features. This texture descriptor measures the local distribution of binary patterns in an image.

- Color Naming - 16 features. These represent descriptions of colors in images, classified into a predefined set of color names.

- Discriminative Color - 13 features. This descriptor captures information about dominant and discriminative colors in images.

- Hue - 7 features. These are characteristics describing the predominant color hues in the image.

- Opponent - 7 features. This descriptor refers to the representation of colors in an opponent color space.

- Color Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) - 33 features. This is a descriptor that analyzes the distribution of textures and contrasts in images.

- Surface Signatures with Shape-DNA - 100 features. This descriptor refers to the representation of object shapes in images using a DNA-based model.

- 3D Cloud Signatures with Kernel-Principal Component Analysis (PCA) - 100 features. This is a descriptor that performs a principal component analysis on a dataset in an implicitly defined feature space generated by a kernel.

- Within the output file, the first row contains the movie name associated with the image, and the second row contains the ground truth value associated with the image. This information can be useful in evaluating the performance of the models or algorithms used in the work.

- By using this output file, we have access to a detailed and multidimensional representation of the images, which can be used in various image analysis and recognition applications.

2.3. Methods

2.4. Performance Metrics

- , , are True for class A, class B, and class C, respectively.

- are False, that is class i is wrongly predicted as belonging to class j

3. Results and Discussion

- multi_class type: Determines the strategy for handling multi-class classification.

- solver: Specifies the algorithm to use for optimization.

- penalty: Indicates the type of regularization applied to prevent overfitting.

- C: Controls the trade-off between achieving a low training error and a low testing error.

- fit_intercept: Decides whether to include an intercept term in the model.

- max_iter: Sets the maximum number of iterations for the optimization algorithm to converge.

3.1. Comparison with Other Methods and Human Experts

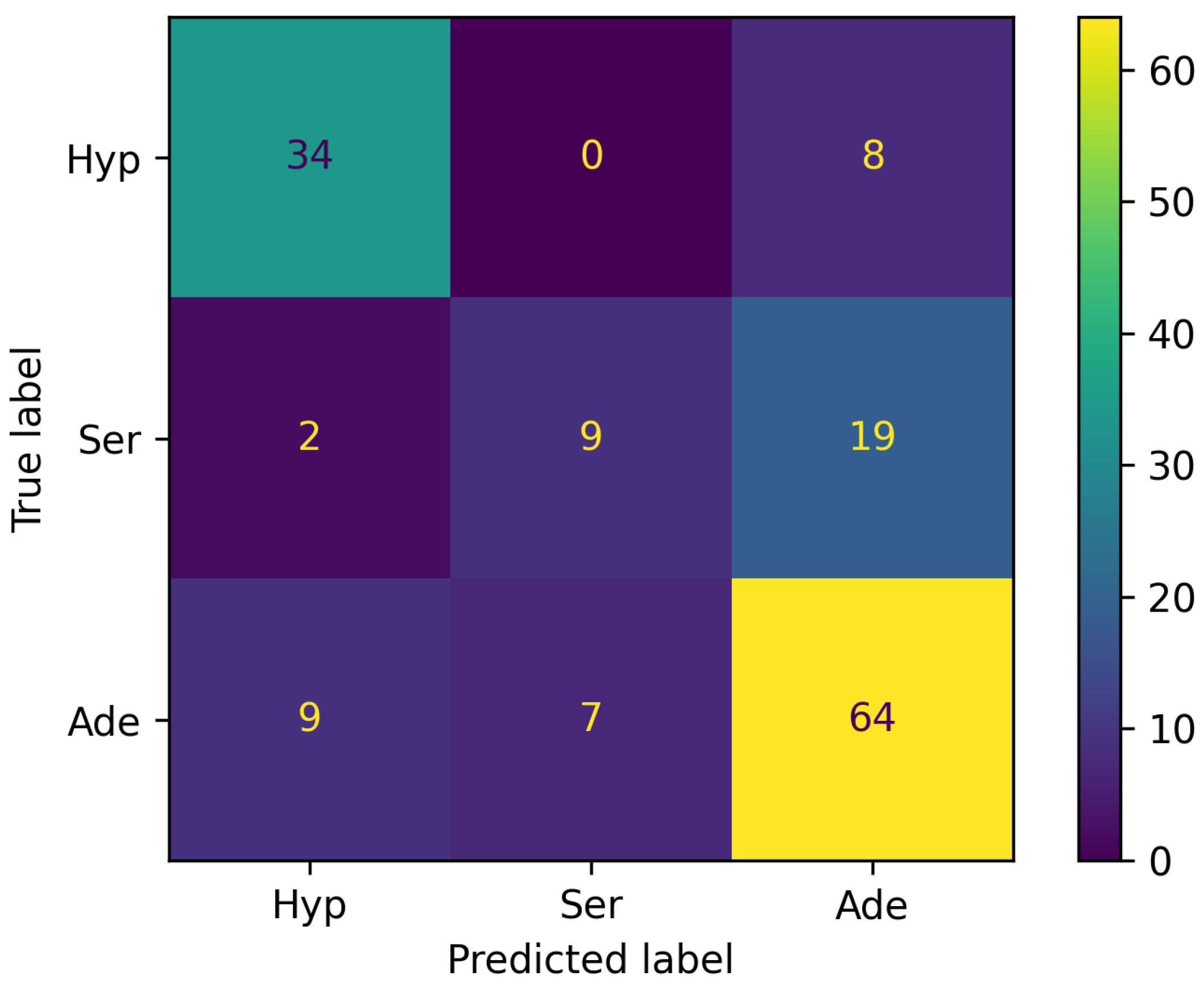

- (Hyp, Hyp): 34 — The model correctly predicted 34 instances as belonging to the Hyp class.

- (Hyp, Ser): 0 — The model incorrectly predicted 0 instances of the Hyp class as Ser.

- (Hyp, Ade): 8 — The model incorrectly predicted 8 instances of the Hyp class as Ade.

- (Ser, Hyp): 2 — The model incorrectly predicted 2 instances of the Ser class as Hyp.

- (Ser, Ser): 9 — The model correctly predicted 9 instances as belonging to the Ser class.

- (Ser, Ade): 19 — The model incorrectly predicted 19 instances of the Ser class as Ade.

- (Ade, Hyp): 9 — The model incorrectly predicted 9 instances of the Ade class as Hyp.

- (Ade, Ser): 7 — The model incorrectly predicted 7 instances of the Ade class as Ser.

- (Ade, Ade): 64 — The model correctly predicted 64 instances as belonging to the Ade class.

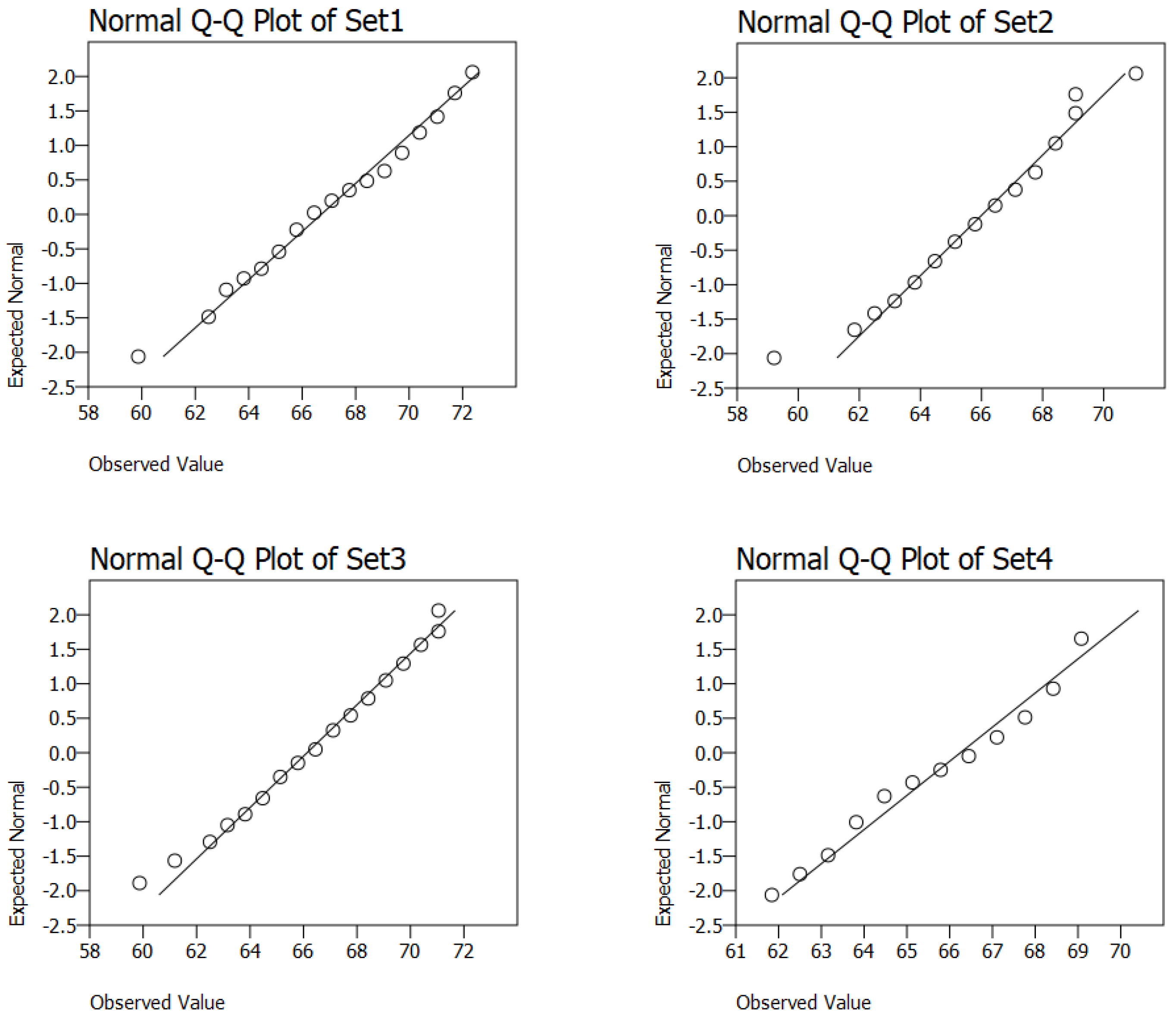

3.2. Statistical Analysis of the Best Models

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A cancer journal for clinicians 2018, 68, 394–424, Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Jul;70(4):313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Parsa, N.; Byrne, M.F. The role of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy. Seminars in Colon and Rectal Surgery 2024, 35, 101007, Technologic Advances in Colon and Rectal Surgery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, C.; Antonelli, G.; Bernhofer, S.; Hassan, C.; Hirata, D.; Iwatate, M.; Maieron, A.; Salvagnini, P.; Cherubini, A. REAL-Colon: A dataset for developing real-world AI applications in colonoscopy. ArXiv 2024. abs/2403.02163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xie, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Cai, J.; Xia, T.; Yang, H.; Yang, B.; Peng, H.; Bai, X.; Yan, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Long, H.; Wang, P.; Chu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Zeng, F. AI based colorectal disease detection using real-time screening colonoscopy. Precis Clin Med 2021, 4, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.S.; Piper, M.A.; Perdue, L.A.; Rutter, C.M.; Webber, E.M.; O’Connor, E.; Smith, N.; Whitlock, E.P. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016, 315, 2576–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Adadi, S.; Berrada, M. Gastroenterology Meets Machine Learning: Status Quo and Quo Vadis. Advances in Bioinformatics 2019, 2019, 1870975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, P.; Dooghaie Moghadam, A.; Eslami, P.; Aghajanpoor Pasha, M.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Mehrvar, A.; Nezami-Asl, A.; Iravani, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Zali, M.R. The role of artificial intelligence in colon polyps detection. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from Bed to Bench 2020, 13, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fati, S.M.; Senan, E.M.; Azar, A.T. Hybrid and Deep Learning Approach for Early Diagnosis of Lower Gastrointestinal Diseases. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdran, A.; Carneiro, G.; Gonzalez Ballester, M.A., Double Encoder-Decoder Networks for Gastrointestinal Polyp Segmentation; 2021; pp. 293–307. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Cha, Y.; Kim, J. Dual encoder–decoder-based deep polyp segmentation network for colonoscopy images. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELKarazle, K.; Raman, V.; Then, P.; Chua, C. Detection of Colorectal Polyps from Colonoscopy Using Machine Learning: A Survey on Modern Techniques. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Zorron Cheng Tao Pu, L.; Liu, Y.; Maicas, G.; Verjans, J.W.; Burt, A.D.; Shin, S.H.; Singh, R.; Carneiro, G. Chapter 15 - Detecting, localizing and classifying polyps from colonoscopy videos using deep learning. In Deep Learning for Medical Image Analysis (Second Edition), Second Edition ed.; Zhou, S.K.; Greenspan, H.; Shen, D., Eds.; The MICCAI Society book Series, Academic Press, 2024; pp. 425–450. [CrossRef]

- Mesejo, P.; Pizarro, D.; Abergel, A.; Rouquette, O.; Beorchia, S.; Poincloux, L.; Bartoli, A. Computer-Aided Classification of Gastrointestinal Lesions in Regular Colonoscopy. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2016, 35, 2051–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V, P.; A, C.K.; Mubarak, D.N. Texture Feature Based Colonic Polyp Detection And Classification Using Machine Learning Techniques. 2022 International Conference on Innovations in Science and Technology for Sustainable Development (ICISTSD), 2022, pp. 359–364. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, X.; Yuan, Y. Joint Polyp Detection and Segmentation with Heterogeneous Endoscopic Data. Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop and Challenge on Computer Vision in Endoscopy (EndoCV 2021): Co-located with the 18th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2021) 2021, 2886, 69–79.

- Galić, I.; Habijan, M.; Leventić, H.; Romić, K. Machine Learning Empowering Personalized Medicine: A Comprehensive Review of Medical Image Analysis Methods. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongo-Onkouo, A.; Ikobo, L.; Apendi, C.; Monamou, J.; Gaporo, N.; Gassaye, D.; Mouakosso, M.; Adoua, C.; Ibara, B.; Ibara, J. Assessment of Practice of Colonoscopy in Pediatrics in Brazzaville, Congo. Open Journal of Pediatrics 2022, 12, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lu, S.; Tang, Y.; Wang, D.; Sun, X.; Yi, J.; Liu, B.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. A Machine Learning-Based System for Real-Time Polyp Detection (DeFrame): A Retrospective Study. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9, 852553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gono, K.; Obi, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ohyama, N.; Machida, H.; Sano, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Hamamoto, Y.; Endo, T. Appearance of enhanced tissue features in narrow-band endoscopic imaging. Journal of biomedical optics 2004, 9, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z.; others. Convolutional neural network for the diagnosis of early gastric cancer based on magnifying narrow band imaging. Gastric Cancer 2020, 23, 126–132. [CrossRef]

- Patino-Barrientos, S.; Sierra-Sosa, D.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Castillo-Olea, C.; Elmaghraby, A. Kudo’s Classification for Colon Polyps Assessment Using a Deep Learning Approach. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- in the Paris Workshop, P. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: Esophagus, stomach, and colon. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2003, 58, S3–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, H.; Libânio, D.; Castro, R.; Ferreira, A.; Barreiro, P.; Boal Carvalho, P.; Capela, T.; Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Santos, C.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M. Reliability of Paris Classification for superficial neoplastic gastric lesions improves with training and narrow band imaging. Endoscopy international open 2019, 7, E633–E640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, Q.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, N.; Xie, H.; Lu, Y. Development and Validation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Prediction of Colorectal Polyps Based on Electronic Health Records. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincar, K.; Sima, I. Machine Learning algorithms approach for Gastrointestinal Polyps classification. International Conference on INnovations in Intelligent SysTems and Applications, INISTA 2020, Novi Sad, Serbia, August 24-26, 2020; Ivanovic, M.; Yildirim, T.; Trajcevski, G.; Badica, C.; Bellatreche, L.; Kotenko, I.V.; Badica, A.; Erkmen, B.; Savic, M., Eds. IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Fay, S.; Yung, D.; Ladabaum, U.; Kopylov, U. Artificial Intelligence–Assisted Colonoscopy in Real-World Clinical Practice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, F.; Silva, F.B.; Ribeiro, M.D.; Coimbra, M.T. Invariant Gabor Texture Descriptors for Classification of Gastroenterology Images. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2012, 59, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Weijer, J.; Schmid, C. Coloring Local Feature Extraction. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2006; Leonardis, A., Bischof, H., Pinz, A., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006; pp. 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; van de Weijer, J.; Khan, F.S.; Muselet, D.; Ducottet, C.; Barat, C. Discriminative Color Descriptors. 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2013, pp. 2866–2873.

- van de Weijer, J.; Schmid, C.; Verbeek, J.; Larlus, D. Learning Color Names for Real-World Applications. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2009, 18, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.; Zisserman, A. Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, 2 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M.; Peinecke, N.; Wolter, F.E. Laplace–Beltrami spectra as ‘Shape-DNA’ of surfaces and solids. Computer-Aided Design 2006, 38, 342–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Information Science and Statistics); Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 3 ed.; Prentice Hall, 2010.

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, R.H.; Lu, P.; Nocedal, J.; Zhu, C. A Limited Memory Algorithm for Bound Constrained Optimization. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 1995, 16, 1190–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Byrd, R.H.; Lu, P.; Nocedal, J. Algorithm 778: L-BFGS-B: Fortran subroutines for large-scale bound-constrained optimization. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 1997, 23, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.L.; Nocedal, J. Remark on “algorithm 778: L-BFGS-B: Fortran subroutines for large-scale bound constrained optimization”. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2011, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. Journal of Statistical Software 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.K.; Narasimhan, B.; Hastie, T. Elastic net regularization paths for all generalized linear models. Journal of Statistical Software 2023, 106, 1, Epub 2023 Mar 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Le Roux, N.; Bach, F. Minimizing finite sums with the stochastic average gradient. Mathematical Programming 2017, 162, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defazio, A.; Bach, F.R.; Lacoste-Julien, S. SAGA: A Fast Incremental Gradient Method With Support for Non-Strongly Convex Composite Objectives. Neural Information Processing Systems, 2014.

- Singh, D.; Singh, B. Feature wise normalization: An effective way of normalizing data. Pattern Recognition 2021, 122, 108307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F. and Varoquaux, G. and Gramfort, A. and Michel, V. and Thirion, B. and Grisel, O. and Blondel, M. and Prettenhofer, P. and Weiss, R. and Dubourg, V. and Vanderplas, J. and Passos, A. and Cournapeau, D. and Brucher, M. and Perrot, M. and Duchesnay, E.. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830.

- Iantovics, Enăchescu, C. Method for Data Quality Assessment Synthetic Industrial Data. Sensors 2022, 22, 1608. [CrossRef]

- Iantovics, L.B.; Rotar, C.; Nechita, E. A Novel Robust Metric for Comparing the Intelligence of Two Cooperative Multiagent Systems. Procedia Computer Science 2016, 96, 637–644, Knowledge-Based and Intelligent Information & Engineering Systems: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference KES-2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iantovics, L.B. Measuring Machine Intelligence Using Black-Box-Based Universal Intelligence Metrics. New Approaches for Multidimensional Signal Processing; Kountchev, R., Mironov, R., Nakamatsu, K., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Iantovics, L.B.; Dehmer, M.; Emmert-Streib, F. MetrIntSimil—An Accurate and Robust Metric for Comparison of Similarity in Intelligence of Any Number of Cooperative Multiagent Systems. Symmetry 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iantovics, L.B. Black-Box-Based Mathematical Modelling of Machine Intelligence Measuring. Mathematics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predicted P (1) | Predicted N (0) | |

|---|---|---|

| Real P (1) | TP | FN |

| Real N (0) | FP | TN |

| Predicted Class A | Predicted Class B | Predicted Class C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real Class A | |||

| Real Class B | |||

| Real Class C | |||

| Hyperparameter | Values Considered |

|---|---|

| data type | { non-normalised, normalised } |

| multi_class type | { multinomial, ovr } |

| solver | { lbfgs, liblinear, newton-cg, sag, saga } |

| penalty | { none, L1, L2, elasticnet } |

| C | { 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 } |

| fit_intercept | { False, True } |

| max_iter | { 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 1000, 5000, 10000 } |

| l1_ratio | { 0.5 } |

| Solver | Penalty | C | fit_intercept | Accuracy (Std Dev) [%] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OvR | Multinomial | ||||||

| non-Norm | Norm | non-Norm | Norm | ||||

| lbfgs | None | - | F | Not conv | Not conv | 61.18 (3.42) | Not conv |

| T | Not conv | Not conv | 66.45 3.42 | Not conv | |||

| L2 | 0.01 | F | 63.82 (2.87) | 52.63 (4.16) | 62.5 (3.89) | 52.63 (4.16) | |

| T | 63.82 (2.87) | 52.63 (4.16) | 61.84 (4.36) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| liblinear | L1 | 0.01 | F | 70.39 (3.89) | 27.63 (5.42) | ||

| T | 70.39 (3.89) | 27.63 (5.42) | |||||

| L2 | 0.01 | F | 63.16 (3.22) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| T | 63.16 (3.22) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||||

| newton-cg | None | - | F | 55.92 (10.59) | 45.39 (1.14) | 60.53 (4.92) | 36.84 (2.63) |

| T | 63.16 (1.86) | 40.79 (2.28) | 59.87 (5.05) | 42.76 (6.8) | |||

| L2 | 0.01 | F | 63.82 (2.87) | 52.63 (4.16) | 62.5 (3.89) | 52.63 (4.16) | |

| T | Not conv | 52.63 (4.16) | 63.82 (3.89) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| sag | None | - | F | 63.82 (2.18) | 40.13 (5.9) | 63.82 (1.14) | 38.16 (6.03) |

| T | 63.82 (2.18) | 42.11 (5.58) | 63.82 (1.14) | 40.79 (5.43) | |||

| L2 | 0.01 | F | 63.82 (2.18) | 52.63 (4.16) | 63.82 (1.14) | 52.63 (4.16) | |

| T | 63.82 (2.18) | 52.63 (4.16) | 63.82 (1.14) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| saga | None | - | F | 63.16 (4.16) | 44.08 (6.8) | 62.5 (2.18) | 41.45 (7.06) |

| T | 63.16 (4.16) | 43.42 (9.39) | 62.5 (2.18) | 44.08 (7.76) | |||

| L1 | 0.01 | F | 62.5 (3.89) | 27,63 (5.42) | 61.18 (1.14) | 27.63 (5.42) | |

| T | 62.5 (3.89) | 52.63 (4.16) | 61.18 (1.14) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| L2 | 0.01 | F | 63.16 (4.16) | 52.63 (4.16) | 62.5 (2.18) | 52.63 (4.16) | |

| T | 63.16 (4.16) | 52.63 (4.16) | 62.5 (2.18) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| elasticnet | 0.01 | F | 63.16 (4.92) | 27.63 (5.42) | 61.18 (1.14) | 27.63 (5.42) | |

| T | 63.16 (4.92) | 52.63 (4.16) | 61.18 (1.14) | 52.63 (4.16) | |||

| LR | Mesejo2016 | Human Expert | Human Beginner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc Mean | 70.39% | 65.00% | 58.42% | |

| Acc Max | 76.32% | 76.69% | - | - |

| Prec Hyp | 75.55% | 66.66% | 62.00% | 66.26% |

| Prec Ser | 56.25% | 69.23% | 52.20% | 51.54% |

| Prec Ade | 70.32% | 80.55% | 73.50% | 66.65% |

| Recall Hyp | 80.95% | 85.71% | 67.90% | 52.40% |

| Recall Ser | 30.00% | 60.00% | 63.75% | 44.70% |

| Recall Ade | 80.00% | 72.50% | 63.75% | 25.00% |

| F1 Hyp | 78.16% | 74.99% | 64.82% | 58.52% |

| F1 Ser | 39.13% | 64.29% | 57.40% | 47.88% |

| F1 Ade | 74.85% | 76.31% | 68.28% | 36.36% |

| macro_av Pre | 67.37% | 72.15% | 62.57% | 61.48% |

| macro_av Recall | 63.65% | 72.74% | 65.13% | 40.70% |

| macro_av F1 | 64.05% | 71.86% | 63.50% | 47.59% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).