1. Introduction

Understanding the nature of consciousness has long been a significant challenge in both the scientific and philosophical realms. In recent years, the study of complexity has provided a new perspective on this age-old problem. Complexity science, which examines how interactions within a system give rise to collective behaviors, offers valuable tools for analyzing the dynamical regimes associated with different states of consciousness.

The human brain is a highly complex dynamical system, and various states of

consciousness—such as wakefulness, sleep, and altered states induced by meditation or substances—can be viewed through the lens of complexity. Chaotic dynamical systems, characterized by sensitivity to initial conditions and long-term unpredictability, serve as a fundamental model for understanding the brain’s complex behavior [

1,

2]. By employing measures from complexity science, these states can be quantified and analyzed in a rigorous manner. This dissertation aims to explore and apply several complexity measures to different dynamical regimes, with a particular focus on states of consciousness.

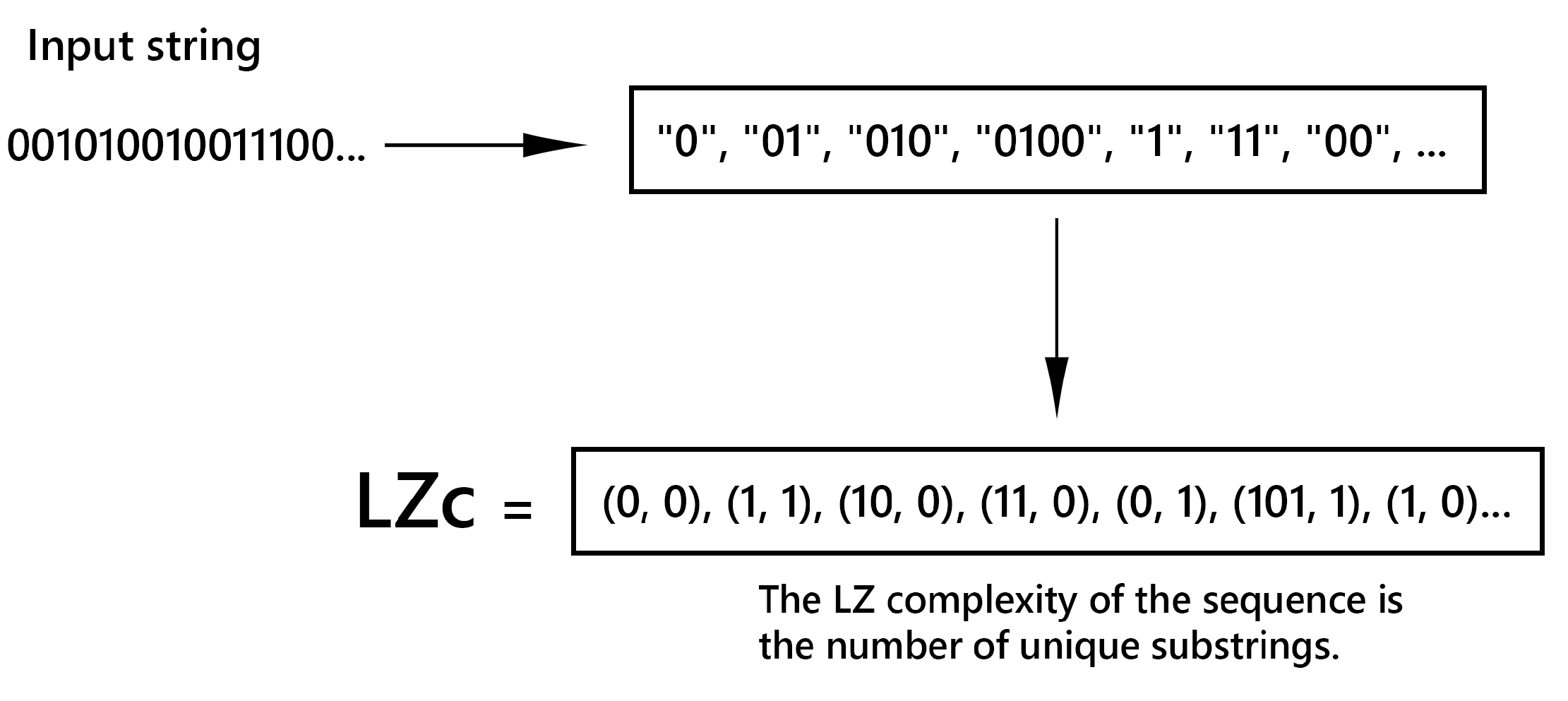

Complexity measures such as Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc), Statistical Complexity (SC), Approximate Entropy (ApEn), and Kolmogorov Complexity (KC) have been shown to differentiate between various states of consciousness. Lempel-Ziv complexity quantifies the compressibility of a sequence by identifying the number of distinct patterns or substrings within it[

3], with higher values indicating greater diversity and randomness in the sequence. Statistical complexity captures the structural complexity of a time series by evaluating the amount of information stored in the system [

4]. Approximate entropy assesses the regularity and unpredictability of fluctuations in a time series, focusing on the likelihood that similar patterns of observations will not be followed by additional similar observations [

5]. Kolmogorov complexity evaluates the complexity of a sequence based on the length of the shortest possible description (or program) that can produce the sequence, reflecting the inherent randomness and informational content of the sequence [

6].

Recent studies have demonstrated that global states of consciousness can be effectively differentiated using measures of temporal differentiation, which assess the number or entropy of temporal patterns in neurophysiological time series [

7]. Temporal differentiation refers to how varied a time series is over time. Typically, time series from unconscious states, such as general anesthesia and NREM sleep, display less temporal differentiation compared to those from awake states [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. These observations align with the entropic brain hypothesis, which posits that higher temporal differentiation correlates with richer and more diverse conscious experiences [

14,

15,

16,

17].

In parallel with these advances, Integrated Information Theory (IIT) has emerged as a leading theoretical framework for understanding consciousness. IIT posits that consciousness corresponds to the capacity of a system to integrate information, quantified by a measure known as

[

18].

represents the degree to which a system’s informational content is greater than the sum of its parts, reflecting the system’s ability to produce a unified, integrated experience [

19,

20]. Despite its conceptual elegance, the practical application of

is severely limited by the immense computational complexity required to calculate it in real-world systems like the human brain [

21,

22].

Given the challenges of directly measuring

, researchers have explored alternative methods to approximate the integrated information in the brain. The Perturbational Complexity Index (PCI) has been introduced as an empirical proxy for

[

10]. PCI is derived from the brain’s response to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and measures the complexity of the resulting EEG signals. By capturing both the integration and differentiation of neural activity, PCI aligns with the core principles of IIT and serves as a feasible measure of consciousness that can be applied across different states and clinical conditions.

Building on these foundations, this research seeks to investigate how these complexity measures vary across different dynamical regimes and how effectively they detect changes in both simulated and real-world data. It also explores their ability to distinguish between various sleep stages, revealing different aspects of brain dynamics. To achieve this, we utilize a range of models that represent different types of dynamical behavior: purely random data, the logistic map, and the multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) model.

Purely random data serves as a baseline model, representing a system with maximal entropy and minimal structure. This allows us to explore how complexity measures behave in the absence of deterministic patterns [

23,

24]. The logistic map is a simple yet powerful mathematical model that exhibits a wide range of behaviors, from periodic to chaotic, depending on the parameter settings [

25,

26]. It serves as a classic example of a chaotic system, making it an ideal candidate for testing how complexity measures respond to varying degrees of order and chaos. The multivariate autoregressive (MVAR) model is a more complex, data-driven approach that captures the relationships between multiple time series variables [

27,

28]. It is often used to model and analyze real-world systems like brain dynamics, offering a more realistic representation of how different brain regions interact over time.

The comparison of results from these models with those derived from real-world data is intended to assess the consistency and variability of these measures in practical applications. This approach contributes to a deeper understanding of consciousness through the interplay of complexity, information integration, and entropy.

1.1. Research Objectives

The primary aim of this research is to investigate the behaviours of complexity measures in different dynamical regimes and how these measures can be used to understand and differentiate between various states of consciousness. Specific objectives include:

Applying statistical, informational, and dynamical complexity measures to simulated and real-world data.

Examining the behavior of these measures in different dynamical regimes, such as chaotic and periodic systems.

Comparing the effectiveness of complexity measures in capturing the dynamical properties of the systems studied.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a mixed-methods approach to investigate the application of complexity measures in understanding different states of consciousness. The research involves both theoretical modeling and empirical data analysis. The methodology is divided into several key components, including the modeling of dynamical systems, computation of complexity measures, data generation, and analysis procedures, as well as the tools and software used.

3.2. Modeling Dynamical Systems

To explore the application of complexity measures, two types of dynamical systems were modeled: logistic maps and Multivariate Autoregressive (MVAR) models. These models help simulate different dynamical regimes and provide a basis for analyzing complexity.

3.2.1. Logistic Map

The logistic map is a simple yet powerful model that illustrates how complex, chaotic behavior can arise from very simple nonlinear dynamical equations. It is given by the recurrence relation:

where represents the population at generation n and r is a parameter that represents the growth rate.

3.2.2. Dynamics of the Logistic Map

Understanding the dynamics of the logistic map starts with examining its fixed points. These points occur where the state of the system remains unchanged over iterations, identified by setting . Solving the equation reveals two fixed points: and .

The stability of these fixed points is determined by the derivative of the logistic map function,

, evaluated at the fixed points. The derivative is given by:

For the fixed point at

, the derivative

. For the fixed point at

, the derivative

. A fixed point is considered stable if the absolute value of the derivative is less than 1.

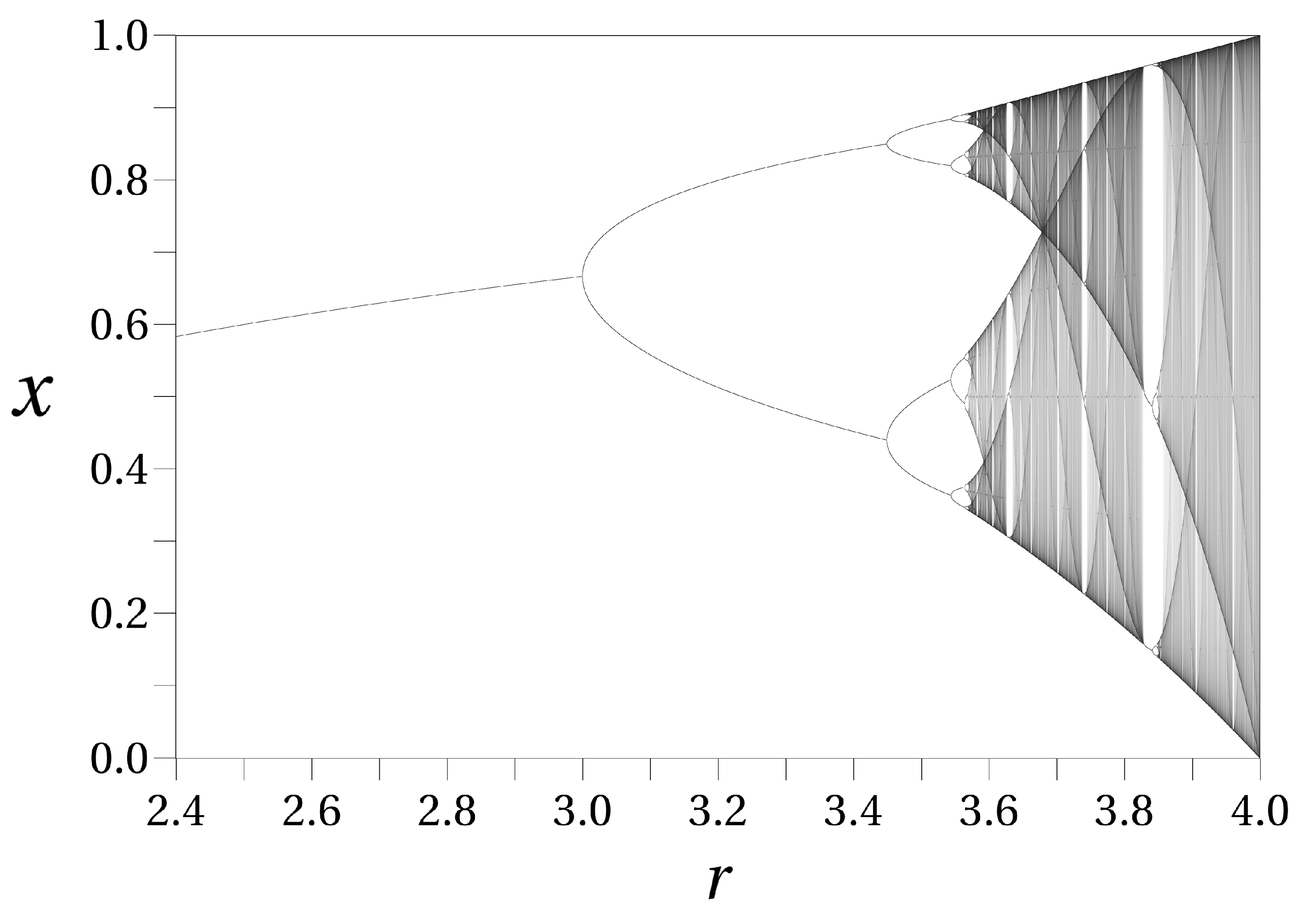

As the parameter

r increases, the logistic map undergoes a series of bifurcations, leading to changes in the system’s behavior. Initially, for small values of

r, the system exhibits a single stable fixed point. As

r increases further, the system transitions to periodic orbits, where the state of the system cycles through a set of values. Beyond a critical value of

r, the system enters a chaotic regime, characterized by aperiodic and unpredictable behavior. This progression can be visualized in (

Figure 4), which vividly illustrates the transition from order to chaos as

r is varied.

For small values of

r, the logistic map converges to a single stable fixed point, as shown by a single line in the bifurcation diagram. As

r increases, the system undergoes period-doubling bifurcations, transitioning from a stable fixed point to periodic orbits, with each bifurcation doubling the period of the orbit. This is observed in

Figure 4 as the single line splitting into two, then four, and so on. Beyond a critical value of

r (approximately

), the system enters a chaotic regime where the behavior becomes aperiodic and highly sensitive to initial conditions, resulting in a dense, complex structure in the bifurcation diagram. Within the chaotic regime, there are windows of periodicity where periodic behavior re-emerges, visible as isolated islands of periodicity in the chaotic region of the bifurcation diagram [

2,

32].

3.2.3. Lyapunov Exponent

The Lyapunov exponent is a crucial measure for characterizing the sensitivity to initial conditions in a dynamical system. It quantifies the average rate at which nearby trajectories diverge or converge in phase space [

1,

53,

54]. For the logistic map, the Lyapunov exponent provides insight into the presence of chaos.

The Lyapunov exponent

is defined as:

where

represents the

i-th iterate of the logistic map. To calculate

, the logistic map is iterated, and the logarithm of the absolute value of the derivative is summed at each step.

where

N is the total number of iterations (

See Appendix A.1 for extended derivation).

The Lyapunov exponent provides a quantitative measure of chaos:

If , the system is chaotic, indicating that small differences in initial conditions grow exponentially over time.

If , the system is stable, meaning that trajectories converge.

If , the system is on the boundary between stability and chaos.

3.2.4. Multivariate Autoregressive (MVAR) Models

Multivariate Autoregressive (MVAR) models are powerful tools for analyzing time series data, particularly in understanding the interactions and dependencies among multiple time series. These models are extensively used in fields such as neuroscience, economics, and meteorology to capture the dynamic relationships between variables over time [

28,

55,

56].

An MVAR model of order

p for a vector time series

is given by:

where:

is an n-dimensional vector representing the values of n variables at time t.

are coefficient matrices that capture the influence of past values of the variables on their current values.

p is the order of the model, indicating how many past time steps are included.

is an n-dimensional vector of error terms, assumed to be white noise.

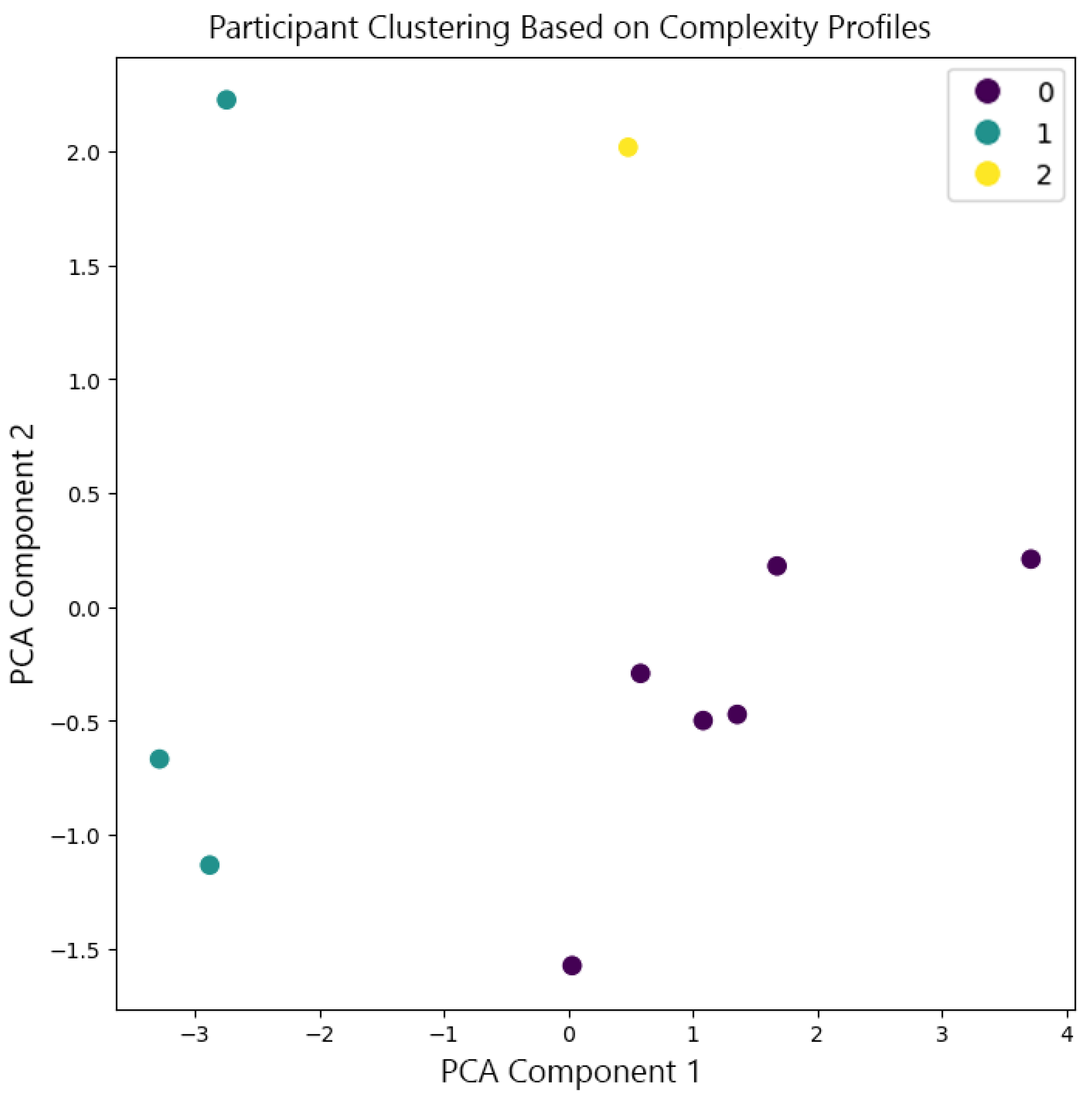

3.3. Statistical Complexity Algorithm

In general, statistical complexity is used to analyze time series data, helping to distinguish between different states or conditions of a system. Higher statistical complexity indicates that the system has a more structured and predictable behaviour, while lower complexity suggests a more random or less organized process.

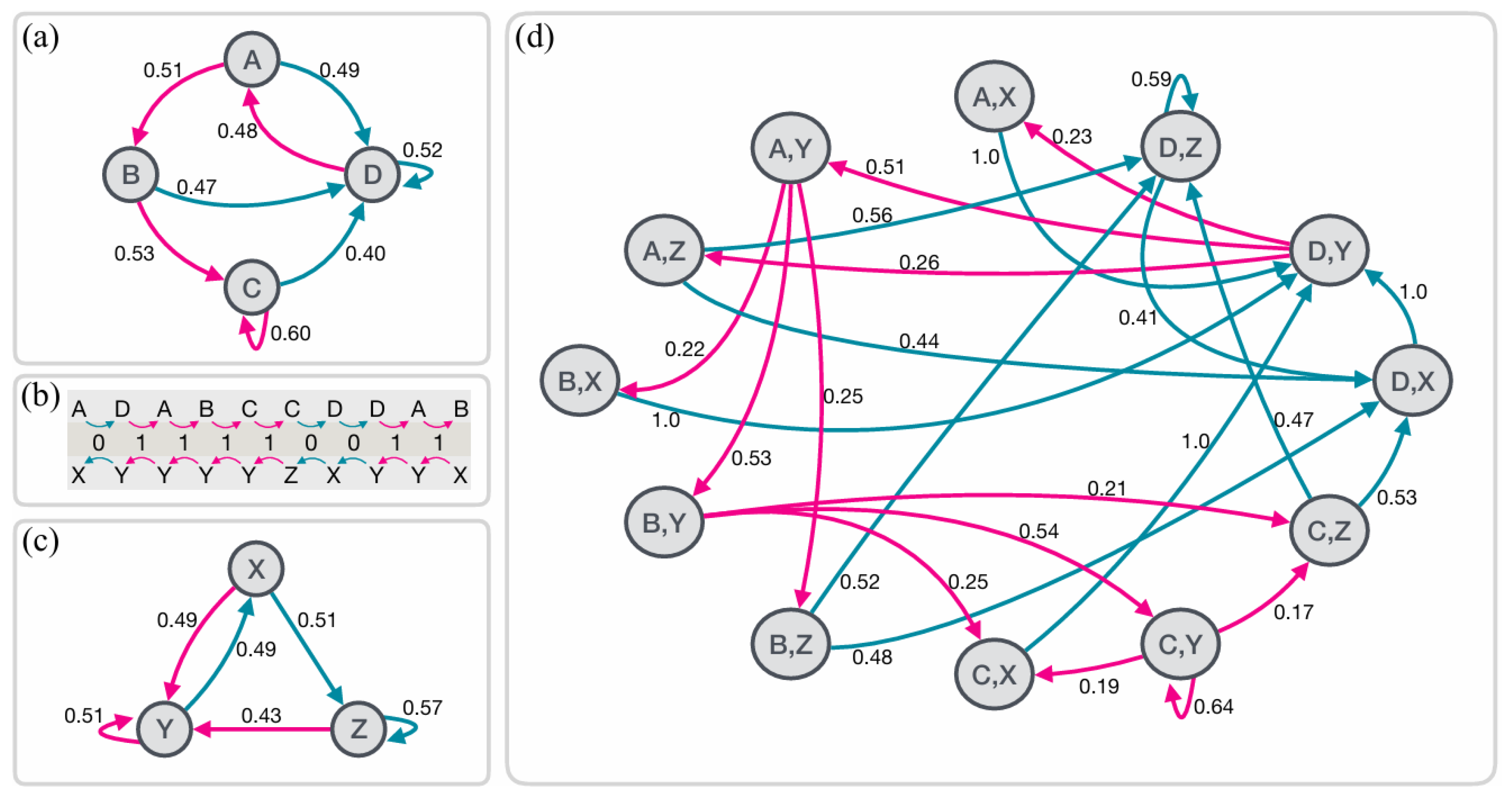

3.3.1. Construction of -Machines

The

-machine is a minimal and optimal model that encodes the statistical structure of a time series, providing a powerful method for analyzing the complexity of a process. It is constructed to capture all relevant temporal correlations in the data, enabling accurate prediction of future behavior based on past observations [

4].

The construction of an

-machine begins with the representation of the time series data,

, where each element

represents an observation at discrete time steps from a finite alphabet

A. The finite alphabet

A is a set of symbols that encode the possible states or observations in the system, such as

. For practical purposes, continuous data is first discretized by converting it into a sequence of symbols from this alphabet. Each symbol corresponds to a specific state or observation at a given time step [

4,

32]. This process facilitates handling and analyzing complex systems where observations occur sequentially over time.

The next step in constructing an

-machine is to partition the time series into past and future sequences, with the goal of predicting the future sequence based on the available past data. Causal states are defined by grouping together past sequences that share the same conditional probability distribution over future sequences. Formally, two histories,

and

, belong to the same causal state

if:

Where

denotes that two histories belong to the same causal state. In other words, if different past sequences lead to identical probabilistic predictions about the future, they are considered equivalent and belong to the same causal state (

Figure 1b). Thus, a causal state represents an equivalence class of past observations that cannot be further distinguished based on their potential to predict the future. This process is an iterative process that refines these causal states by examining the conditional probabilities of future outcomes based on past sequences [

31,

57,

58]. It starts with short past sequences and progressively considers longer sequences, splitting existing causal states whenever differences in future probability distributions are detected. The procedure continues until a stable set of causal states is achieved, capturing all relevant temporal correlations in the data up to a specified maximum memory length,

.

The resulting

-machine is represented as a directed graph, where nodes correspond to the identified causal states, and edges represent transitions between these states. Each edge is labeled with the probability of transitioning from one state to another, along with the symbol emitted during the transition [

31,

58]. This graph offers a framework for interpreting the system’s temporal evolution and the encoding of its complexity (

see Figure B1). The statistical complexity, represented by

, is then the probability distribution over these causal states:

where is the stationary probability of being in causal state . This complexity measure reflects the minimal amount of information required to optimally predict future behavior. Higher values of indicate a more complex and structured process, while lower values suggest simplicity or randomness.

The

-machine framework allows for the analysis of time series in both forward and reverse directions, enabling the study of temporal asymmetry. Temporal asymmetry refers to the difference in the statistical properties or informational structure of a time series when analyzed in the forward direction versus the reverse direction. Constructing

-machines for both time directions makes it possible to quantify differences in the information structure using measures such as causal irreversibility (

), which is the difference in statistical complexity between forward and reverse

-machines:

where

and

are the complexities of the forward and reverse

-machines, respectively. Another measure, crypticity (

d), quantifies the amount of hidden information required to synchronize the forward and reverse processes, representing additional complexity when accounting for bidirectional temporal correlations [

59]. These measures provide a nuanced understanding of the temporal structure of a process, distinguishing between different states, such as wakeful and anesthetized conditions, by examining how the informational complexity and temporal correlations manifest.

The

-machines framework offers several advantages in quantifying complexity. It captures both short-term and long-term correlations in the data, unlike traditional methods that often focus solely on pairwise correlations. Additionally, it distinguishes between true complexity and randomness by considering the minimal amount of information required for optimal prediction, offering a more nuanced understanding of the underlying process. Furthermore, the framework enables the study of temporal asymmetry, providing valuable insights into the directionality of information flow within complex systems [

4].

3.4. Lempel-Ziv Algorithm

The implementation of the Lempel-Ziv algorithm begins by binarizing the time series data. Each channel data is transformed using the

Hilbert Transform1 to obtain the instantaneous amplitude. A threshold, usually set as the mean absolute value of the analytic signal (median could also be used), is then applied to convert the continuous signal into a binary sequence.

After binarizing the data, the next step is to treat the resulting binary sequences as a matrix where each row corresponds to a channel and each column to a time point. The Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc) is then computed by concatenating these binary sequences and applying a Lempel-Ziv compression algorithm to the concatenated sequence. The complexity measure is proportional to the number of distinct binary subsequences identified in the sequence, reflecting the diversity of patterns in the data.

To normalize the Lempel-Ziv complexity, the raw complexity value is divided by the complexity of a randomly shuffled version of the binary sequence. This normalization ensures that the measure is scaled between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating greater complexity.

3.5. Approximate Entropy Algorithm

The Approximate Entropy (ApEn) algorithm is designed to quantify the complexity or irregularity of a time series by measuring the likelihood that similar patterns in the data remain similar when the length of the patterns is increased [

5]. A low ApEn value indicates a time series with high regularity (predictable patterns), while a high ApEn value suggests a more complex or unpredictable series. Approximate Entropy is calculated using the formula:

where

is the average natural logarithm of the proportion of vector pairs of length

m that remain close to each other within a tolerance

r (

See Appendix A.2 for Extended Derivation).

3.6. Kolmogorov Complexity Algorithm

Kolmogorov complexity measures the complexity of a string as the length of the shortest possible description that can produce that string. For a binary string

x, the Kolmogorov Complexity

is defined as:

where

U is a universal Turing machine,

p is a program (a finite binary string) that produces

x when run on

U, and

denotes the length of

p.

Since Kolmogorov Complexity is uncomputable, practical approximations often use data compression algorithms [

60,

61]. The idea behind using data compression algorithms as proxies is that the length of the compressed version of a string can serve as an estimate of its Kolmogorov complexity. In this study,

zlib compression is employed to estimate the complexity of a string.

zlib is a well-known compression library that uses the DEFLATE algorithm, which combines the LZ77 compression algorithm and Huffman coding. The LZ77 algorithm works by scanning the input data for repeated patterns or substrings and replacing them with shorter references to their previous occurrences. This effectively reduces the amount of redundant data. Huffman coding, on the other hand, is a technique that assigns shorter binary codes to more frequently occurring symbols and longer codes to less frequent symbols, based on their frequency in the data. Together, these two methods allow for efficient data compression.

When a string

x is compressed using

zlib, the DEFLATE algorithm first identifies repeated patterns within the string and replaces them with references. Then, Huffman coding further compresses the data by encoding the symbols in the string with variable-length binary codes. The compressed length of the string

x, denoted as

, is then used as an approximation of the Kolmogorov Complexity:

This method leverages the efficiency of zlib to compress the string, with the resulting compressed length serving as an indirect measure of the string’s algorithmic complexity. A shorter compressed length indicates that the string has a more regular, predictable structure, suggesting lower complexity. Conversely, a longer compressed length implies that the string is more random or lacks structure, reflecting higher complexity.

The effectiveness of zlib in approximating Kolmogorov Complexity comes from its ability to capture both redundancy and randomness in the data. Compressing the string with zlib indirectly measures how well the data can be represented by a shorter description, capturing the essence of Kolmogorov Complexity.

3.7. Software, Tools and Computational Resources

The implementation of the algorithms, along with the analysis of data, required the use of various software tools and computational resources. Python served as the primary programming language due to its versatility and extensive libraries for scientific computing and data analysis. MATLAB was also utilized for initial prototyping and verification of the algorithms, leveraging its extensive toolboxes and familiarity.

The analyses were conducted on high-performance computing (HPC) clusters and workstations equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 6800H processor with 8 cores (16 logical processors) running at 3.2 GHz, along with 16 GB of RAM. These computational resources ensured that the complex algorithms and large datasets were processed efficiently and within a reasonable timeframe.

3.8. Data Generation

3.8.1. Totally Random Data

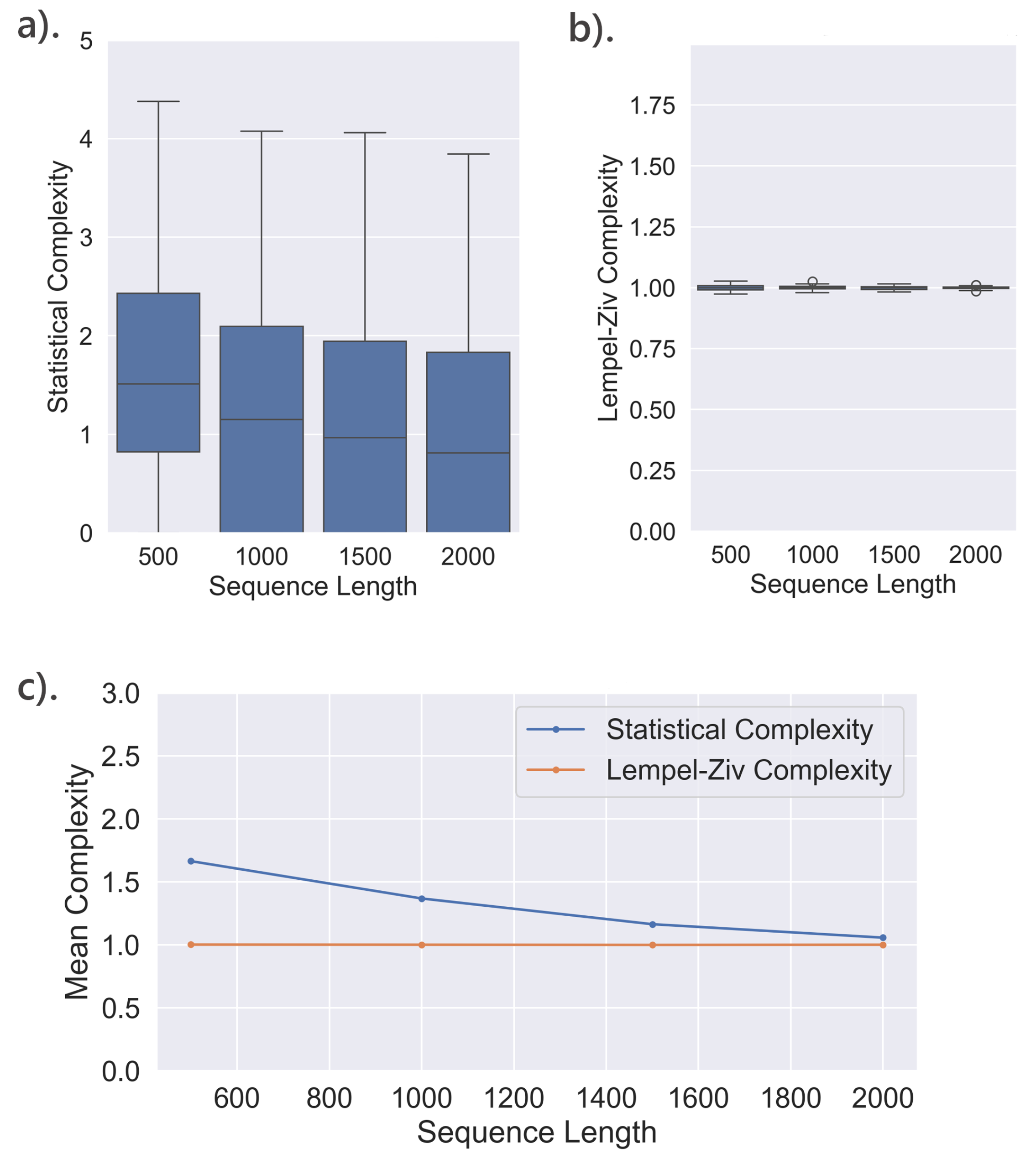

100 random binary time series, each with a length of 500, were initially generated using pseudo-random number generators to ensure they followed a uniform distribution. This step was crucial to simulating truly random data that could serve as a baseline for complexity measures. The generated random data were analyzed by computing both Statistical Complexity (SC) and Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc).

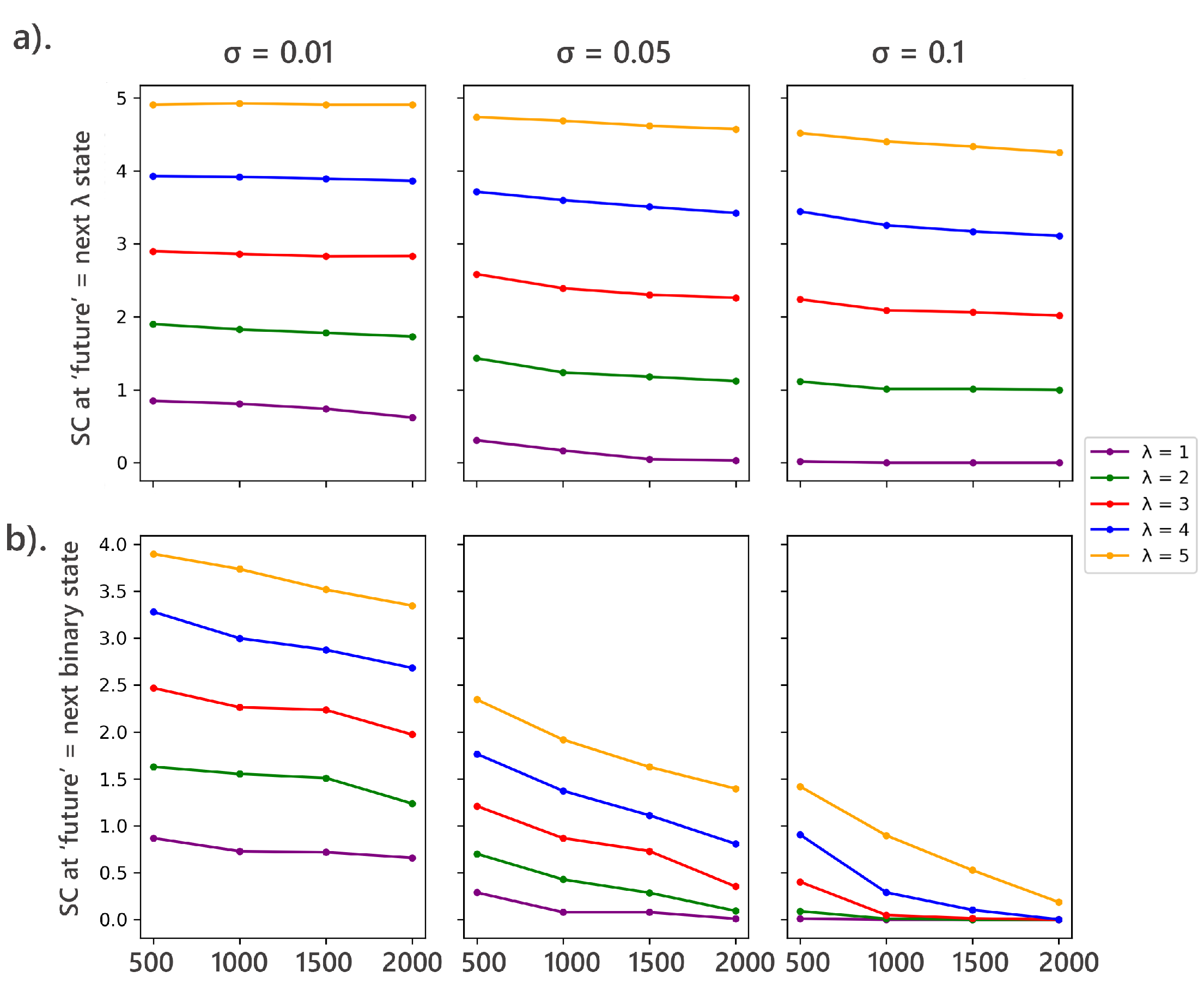

For each binary sequence, SC was calculated by varying the memory length () from 1 to 6. The future was defined as the next observations from the present, and the tolerance parameter () was varied as 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1. Through this analysis, it was observed that the optimal results were obtained with a memory length of and a significance level of .

Neural data are known to have long autocorrelations [

62], so it is advantageous to make

as large as possible. However, for limited-length time series,

must not be too large to ensure each state has a good chance to occur. The results indicated that the effect size grew with

within the range of values considered, reflecting the ability to capture more details of the dynamics and the increased range of values that SC can take.

This specific choice of provided a balance between capturing sufficient temporal correlations and avoiding unnecessary complexity in the model. Shorter memory lengths did not capture enough of the underlying structure in the data, as the -machines only captured short-term dependencies, which did not fully distinguish between random and structured signals. On the other hand, longer memory lengths introduced excessive noise. Similarly, the choice of allowed the model to distinguish meaningful causal states without overfitting. Lower values (e.g., 0.01) were too sensitive and detected too many subtle differences, potentially leading to overfitting, while higher values (e.g., 0.1) smoothed over important distinctions, reducing the model’s sensitivity.

3.8.2. Logistic Map Data

Logistic map data is generated by iterating the logistic map equation (see Eqn.(2)) for a range of r values. Both periodic and chaotic regimes are explored by varying r from 2.5 to 4.0. The initial condition is typically set to a value between 0 and 1. Varying amounts of white noise were added to the simulated data to examine the impact of noise.

This was done a bit differently for the classification of signals; sequences are generated with specific bifurcation parameters:

(periodic),

(weak chaos), and

(strong chaos). The random data generated in

Section 3.8.1 was used alongside these sequences. For each value of

r, sequences of lengths ranging from 200 to 2000 (in steps of 200) were produced, with each type of sequence having 50 samples. Uniform noise at a level of 10% was added to all sequences to simulate real-world conditions. These sequences were then binarized using the median as the threshold:

3.8.3. MVAR Model Data

Simulated data was generated using Multivariate Autoregressive (MVAR) models to create synthetic time series that mimic complex brain dynamics. The process involved generating initial random data for three time series, each with 1,000 observations, followed by fitting an MVAR model to this data.

The generalized connectivity matrix

A was specifically defined to reflect interactions among three variables. The matrix

A was structured as follows:

where each element in the matrix represents the strength of interaction between the variables across different time lags. The order of the MVAR model, p, was set to 1, meaning that only the immediate past state influences the current state.

The time-series data matrix was initialized with values drawn from a standard normal distribution, specifically with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, ensuring that the initial conditions reflected a random Gaussian process. This initialization captures the randomness and variability similar to what is observed in real-world systems.

The MVAR model was then iteratively applied to generate the time series data. Starting from the initial state defined by the random Gaussian values, each subsequent state was computed as a linear combination of the previous states, with the contributions from each past state weighted by the corresponding elements of the connectivity matrix A. For instance, if the initial state for a variable was set at a value drawn from a standard normal distribution (e.g., , , ), these values were then used to calculate the next state using the MVAR equation.

This process continued for a total of 1,500 time points, where the first 500 points served as a transient phase, allowing the system to stabilize into equilibrium. These initial points were subsequently discarded, and only the remaining 1,000 data points, which reflected the stable behavior of the system, were used for further analysis.

3.8.4. Sleep Data

These data are intracranial depth electrode recordings originally collected from 10 neurosurgical patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy, who were undergoing pre-surgical evaluation to localize epileptogenic zones [

13]. Depth electrodes (stereo-electroencephalography, SEEG) were stereotactically implanted into the patients’ brains, guided by non-invasive clinical assessments to ensure precise targeting of the epileptogenic areas and connected regions. The electrodes used were platinum-iridium, semi-flexible, multi-contact intracerebral electrodes, each with a diameter of 0.8 mm, a contact length of 1.5 mm, and an inter-contact distance of 2 mm, allowing for a maximum of 18 contacts per electrode.

The precise placement of the electrodes was verified post-implantation using CT scans, which were co-registered with pre-implant MRI scans to obtain accurate Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates for each contact. Alongside the iEEG recordings, scalp EEG activity was recorded using two platinum needle electrodes placed at standard 10-20 system positions (Fz and Cz) during surgery, with additional recordings of electrooculographic (EOG) activity from the outer canthi of both eyes and submental electromyographic (EMG) activity. Recordings were conducted using a 192-channel system (NIHON-KOHDEN NEUROFAX-110) with an original sampling rate of 1000 Hz. The data were captured in EEG Nihon Kohden format and referenced to a contact located entirely in the white matter. For the purpose of this analysis, the data were downsampled to 250 Hz to facilitate computational efficiency.

Data selection was carefully managed to ensure relevance and quality. Contacts were excluded if they were located within the epileptogenic zone, as determined by post-surgical assessment, or over regions with documented cortical tissue alterations, such as Taylor dysplasia. Additionally, contacts that exhibited spontaneous or evoked epileptiform activity during wakefulness or NREM sleep were excluded, as were contacts located in white matter.

The data were analyzed across four distinct states: wakeful rest (WR), early-night non-rapid eye movement sleep (eNREM), late-night non-rapid eye movement sleep (lNREM), and rapid eye movement sleep (REM). eNREM corresponded to the first stable NREM episode of the night, and lNREM to the last stable NREM episode, with both being in stage N3 sleep. After downsampling, the data were divided into 2-second segments, each of which underwent linear detrending, baseline subtraction, and normalization by standard deviation for each channel to ensure consistency across the dataset.

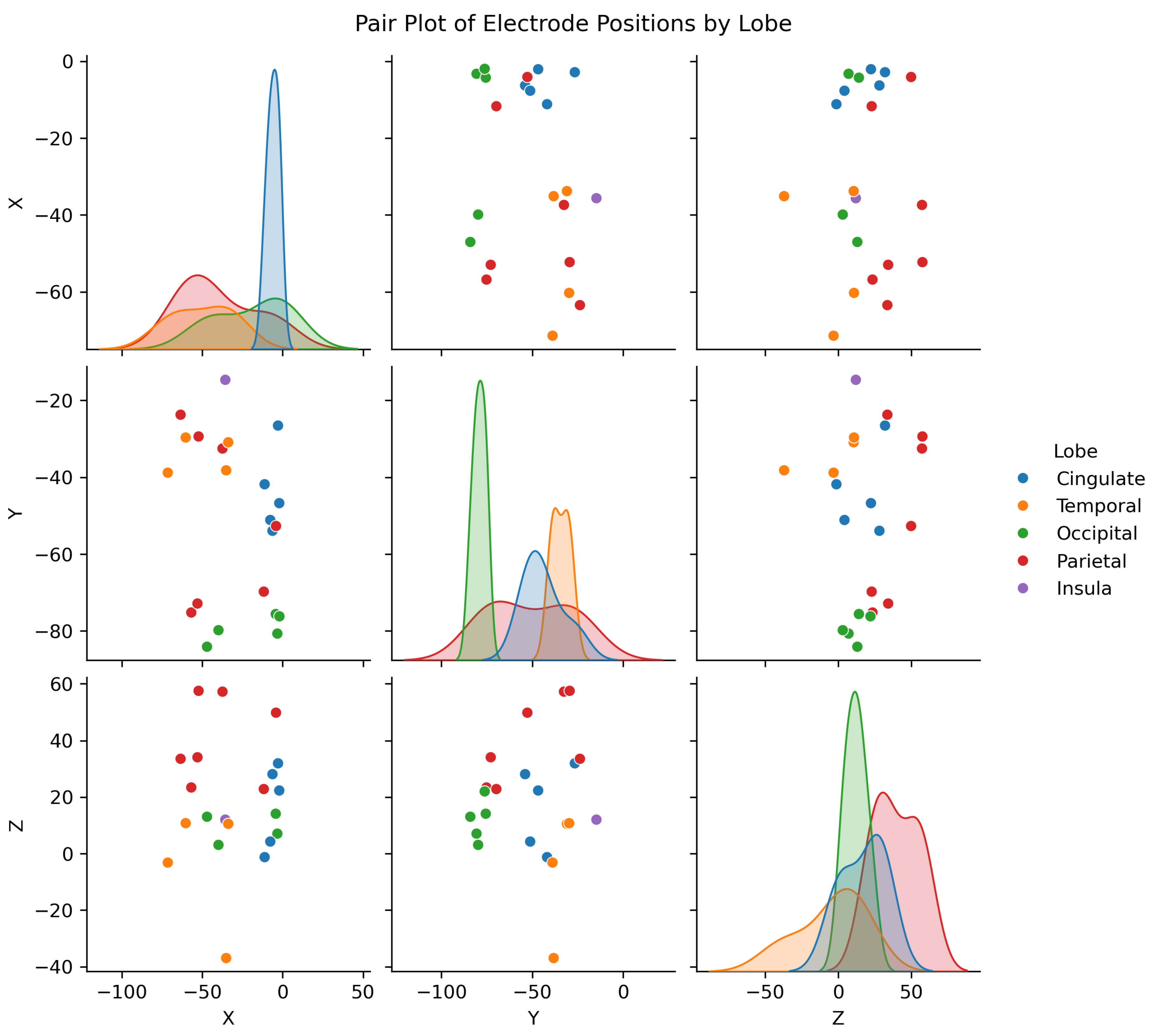

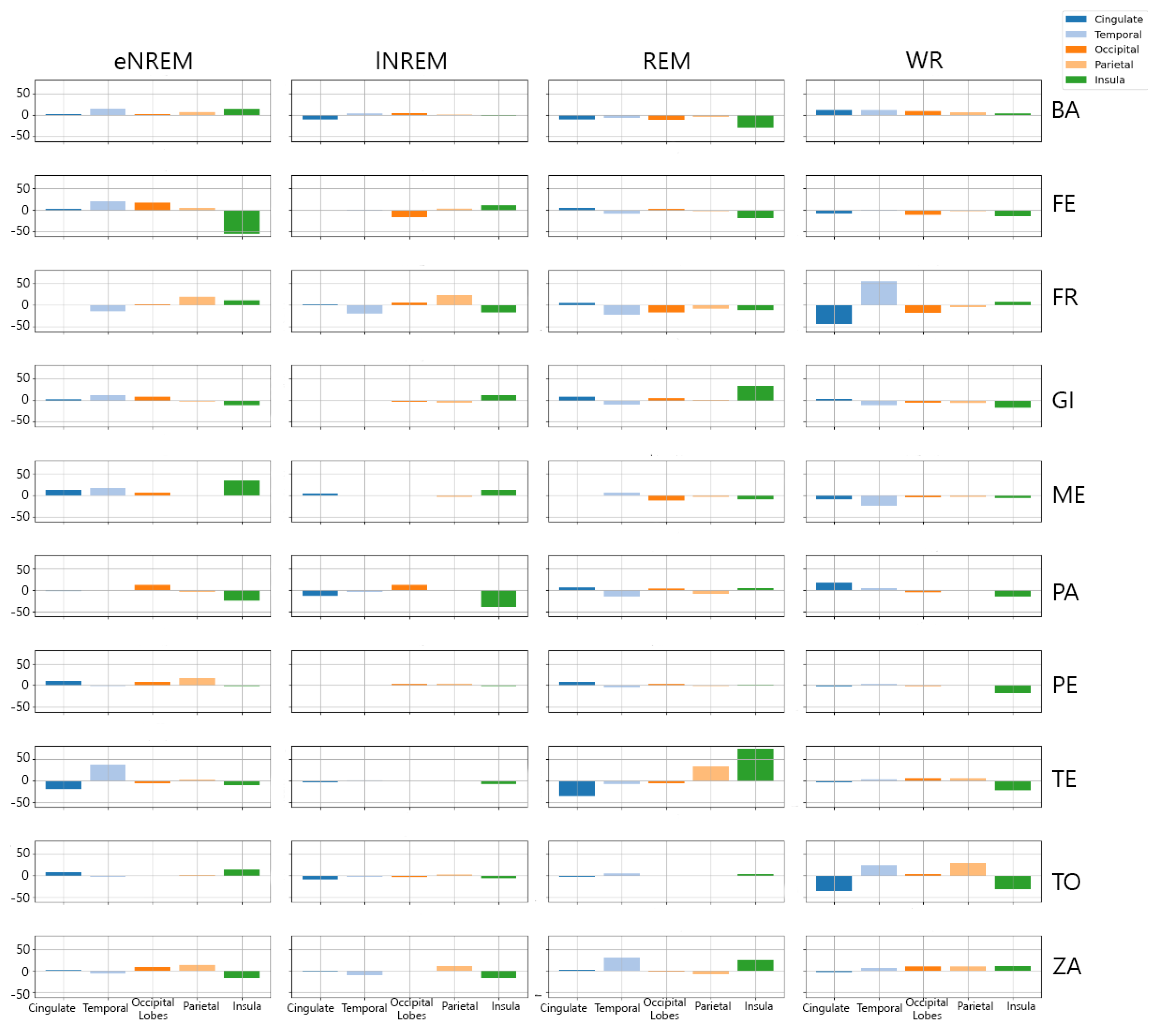

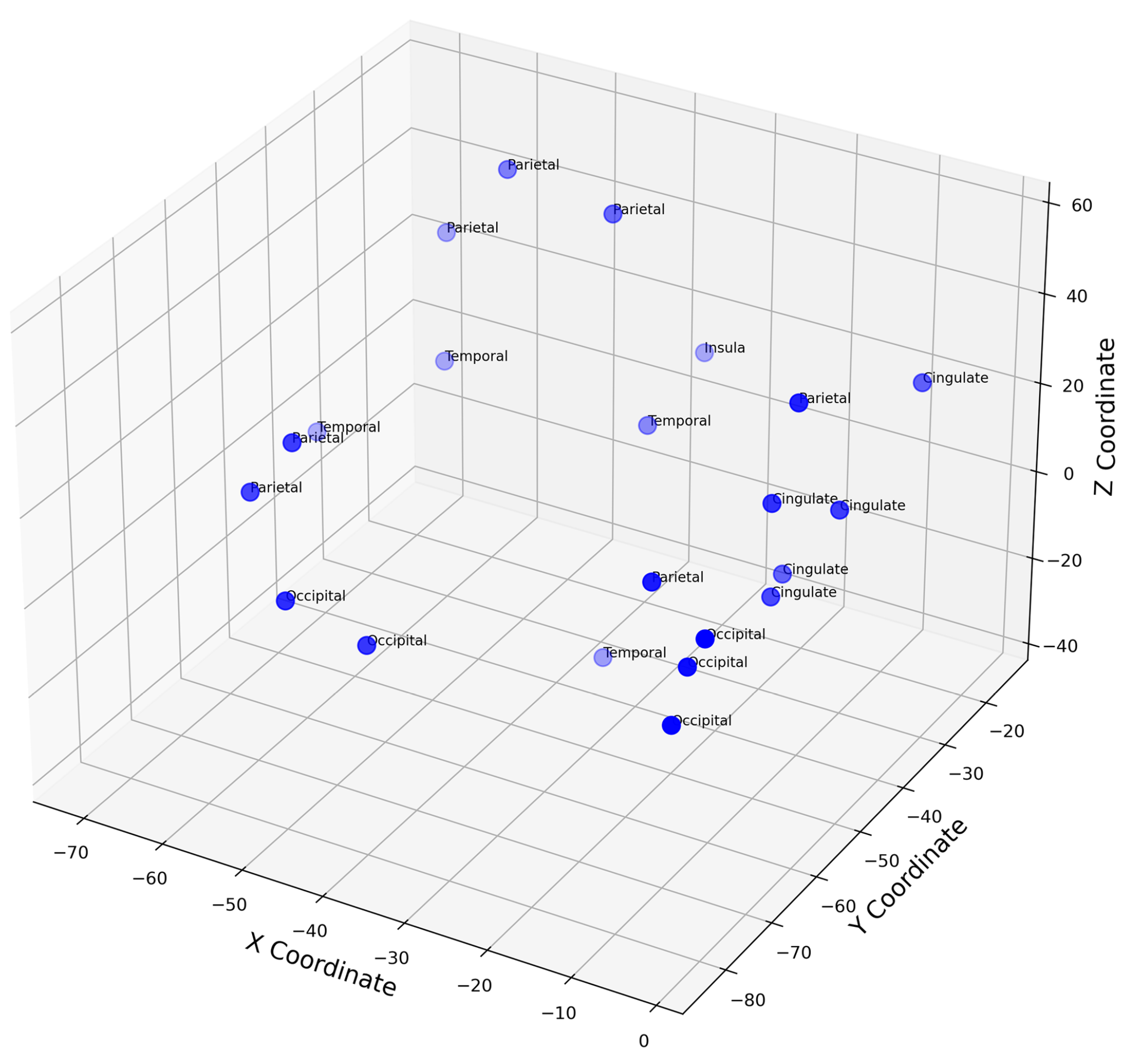

3.8.5. Source Localization of Signal

To estimate brain activity from the intracranial EEG (iEEG) signals, depth electrode recordings were directly analyzed, providing precise localization of electrical activity without the need for traditional source localization techniques used in scalp EEG. The iEEG data, captured from electrodes implanted in specific brain regions, was used to identify anatomical regions associated with different sleep stages. The spatial positions of these electrodes can be visualized in

Figure 5, which maps their locations in MNI coordinate space, highlighting clustering within specific brain areas.

Figure B2 in

Appendix B further explores the spatial distribution, showing pairwise relationships between X, Y, and Z coordinates by brain lobe and

Figure B6 provides a breakdown of the mean activity per lobe across participants and sleep states.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results: Random Data Analysis

The findings from the random data analysis provide valuable insights into the nature of complexity measures and their behavior across different conditions. Statistical Complexity (SC) tends to decrease as the sequence length increases. This trend aligns with the expectation that longer sequences, which are more likely to contain repeated patterns, will exhibit lower complexity due to reduced state space diversity. This behavior was consistent across different values of the memory length parameter and the tolerance parameter , indicating that SC is sensitive to the structure of the data and the nature of state prediction. Specifically, higher values, which account for more extended memory, resulted in higher SC values, reflecting a more extensive exploration of the state space. Conversely, higher values, which allow for more aggressive state merging, led to lower SC values, suggesting a simplified state distribution.

Lempel-Ziv Complexity (LZc), in contrast, maintained a fairly constant value close to 1 across different sequence lengths, highlighting its robustness against variations in data structure and length. This constancy is indicative of LZc’s ability to measure randomness consistently, as random sequences are expected to exhibit maximal entropy, thereby presenting a uniform measure of complexity. This stability suggests that LZc is less sensitive to the structure imposed by sequence length and more reflective of the inherent entropy within the data.

The divergence between SC and LZc complexity underscores their different sensitivities and the aspects of data they measure. SC’s decrease with increasing sequence length indicates a reduction in the complexity of the underlying system, as repeated patterns become more likely. On the other hand, LZc’s stability suggests that it effectively captures the randomness and entropy of the sequences, irrespective of their length.

The investigation into the effect of defining the "future" state in the sequences provided further insights. When the future was defined as the next binary state, SC decreased more significantly with increasing sequence length. This decrease suggests that predicting a single future state is less complex and requires less memory. Conversely, defining the future as the next

states resulted in higher initial SC values, with a more gradual decline in complexity as sequence length increased (

Figure 7). This scenario indicates a more challenging task, requiring more memory and capturing greater structural complexity, especially at higher

values.

In summary, the analysis of random data highlights the contrasting behaviors of SC and LZc complexity measures. SC’s sensitivity to repeated patterns and structures makes it suitable for detecting changes in system complexity, whereas LZc complexity’s robustness makes it reliable for identifying randomness.

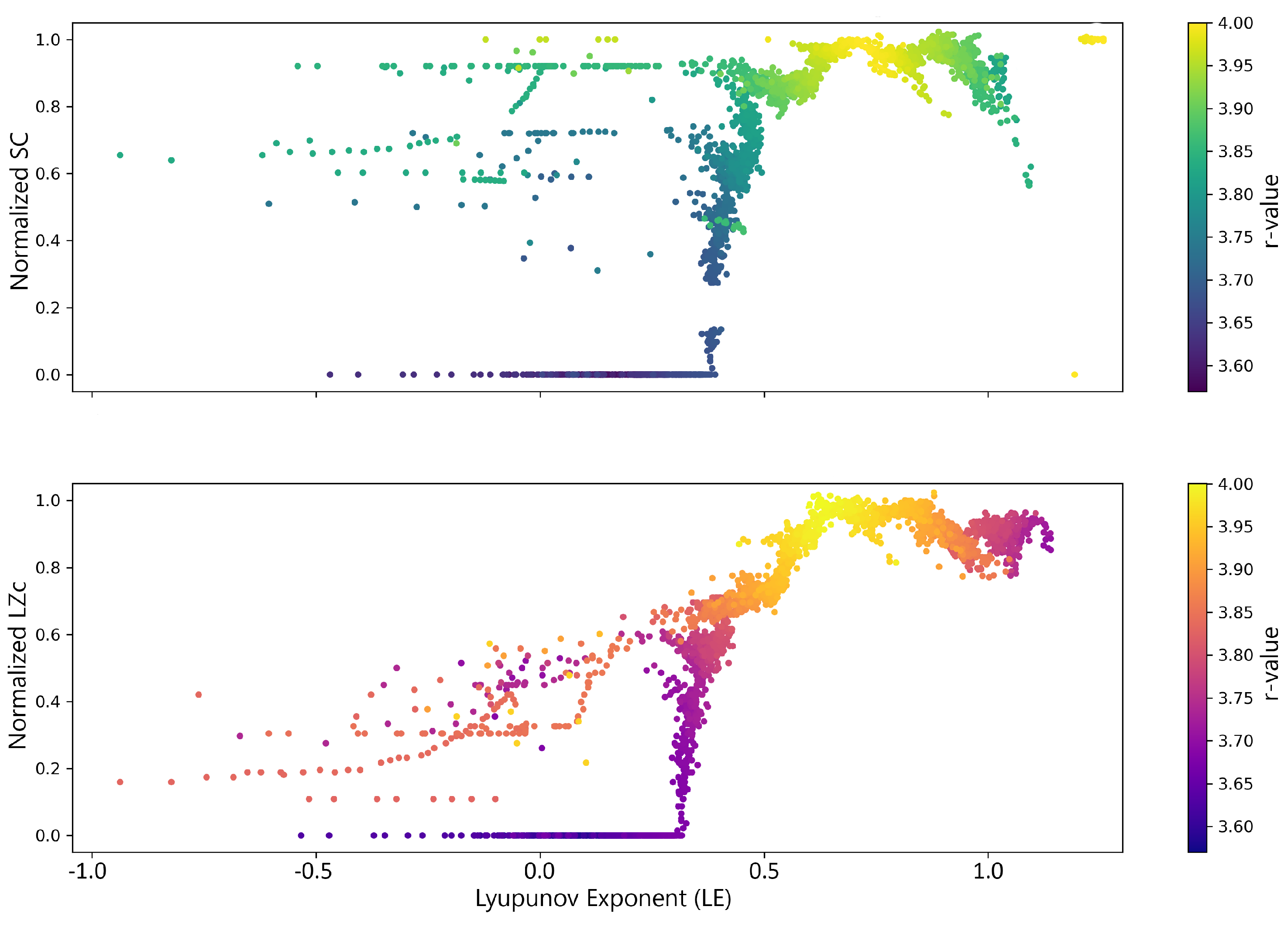

5.2. Interpretation of Results: Logistic Map Analysis

The results from the logistic map analysis provide significant insights into the behavior of the complexity measures across different dynamical regimes. SC and LZc complexity were computed across various parameters, including different noise levels and segment lengths. These measures revealed distinct behaviors under varying conditions (

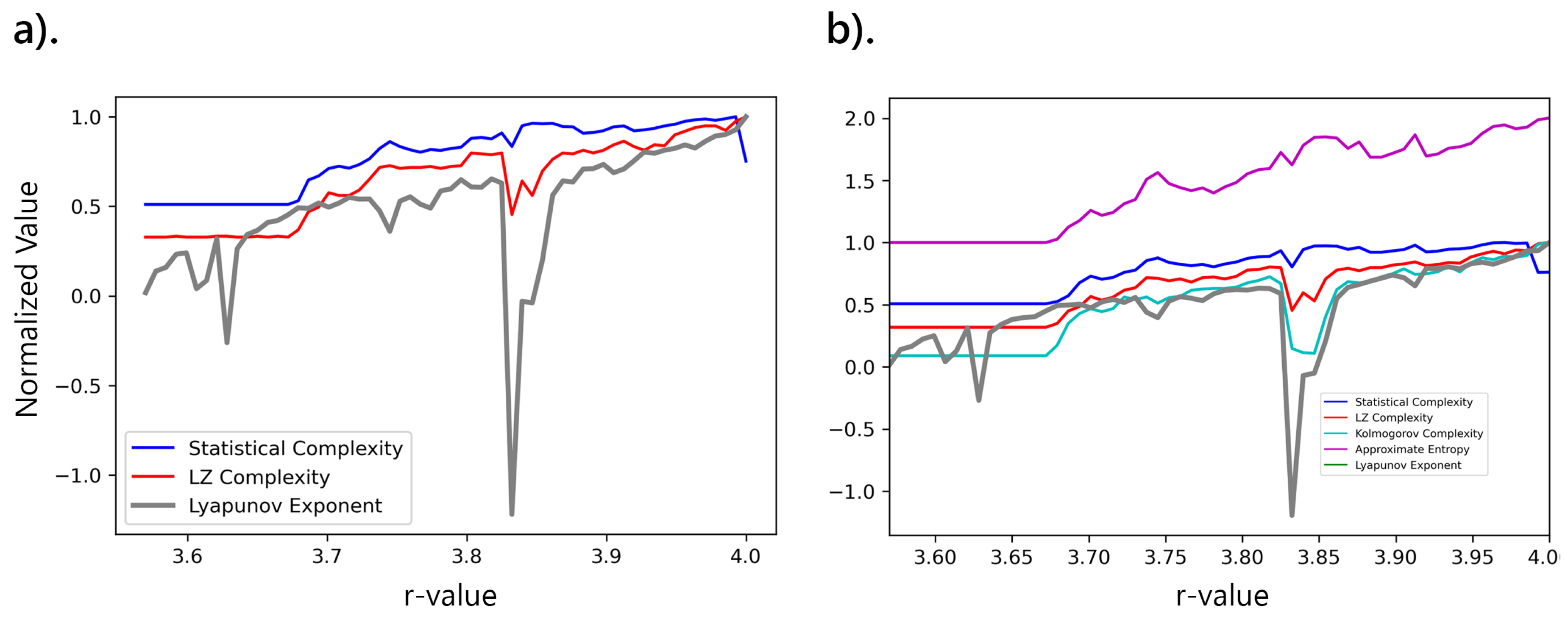

Figure 8a).

As the

r-value increases, the system transitions from stable fixed points to periodic oscillations, and finally to chaotic behavior. SC captures this increasing complexity as the system becomes less predictable and more chaotic. This behavior is similar to findings where the complexity of neural signals is higher in awake (non-anesthetized) states, indicative of a more complex, structured, and deterministic system [

4,

32]. LZc also increases as the

r-value increases but fluctuates, reflecting the increasing randomness in the system as it becomes chaotic. This suggests that while the system is becoming more complex in a Lempel-Ziv sense, this complexity is due to the random nature of chaotic behavior rather than structured, predictive patterns.

The logistic map is known to exhibit fully chaotic behavior at

. The sequence generated by the logistic map at

is maximally chaotic, effectively becoming aperiodic and non-repeating. SC is designed to measure the amount of structure and memory in a system. As the system becomes fully chaotic, it loses any underlying structure that SC would capture. Essentially, the system becomes so random that it no longer requires a complex model to describe it—predicting future states no longer benefits from knowing past states because they are effectively uncorrelated. This lack of structure and the unpredictability inherent in chaos leads to a sharp decline in SC. The system at this point is almost "too random" to be complex in the sense that SC measures, thus the sharp decline. However, LZc continues to increase because it measures the compressibility of the sequence. As the system becomes more chaotic and random, the sequence becomes less compressible, leading to higher Lempel-Ziv values. Random sequences are highly incompressible because they lack repeating patterns that Lempel-Ziv algorithms could use to compress the data [

3,

39]. Therefore, LZc peaks when the system is most chaotic, as the algorithm interprets the lack of compressibility as increased complexity.

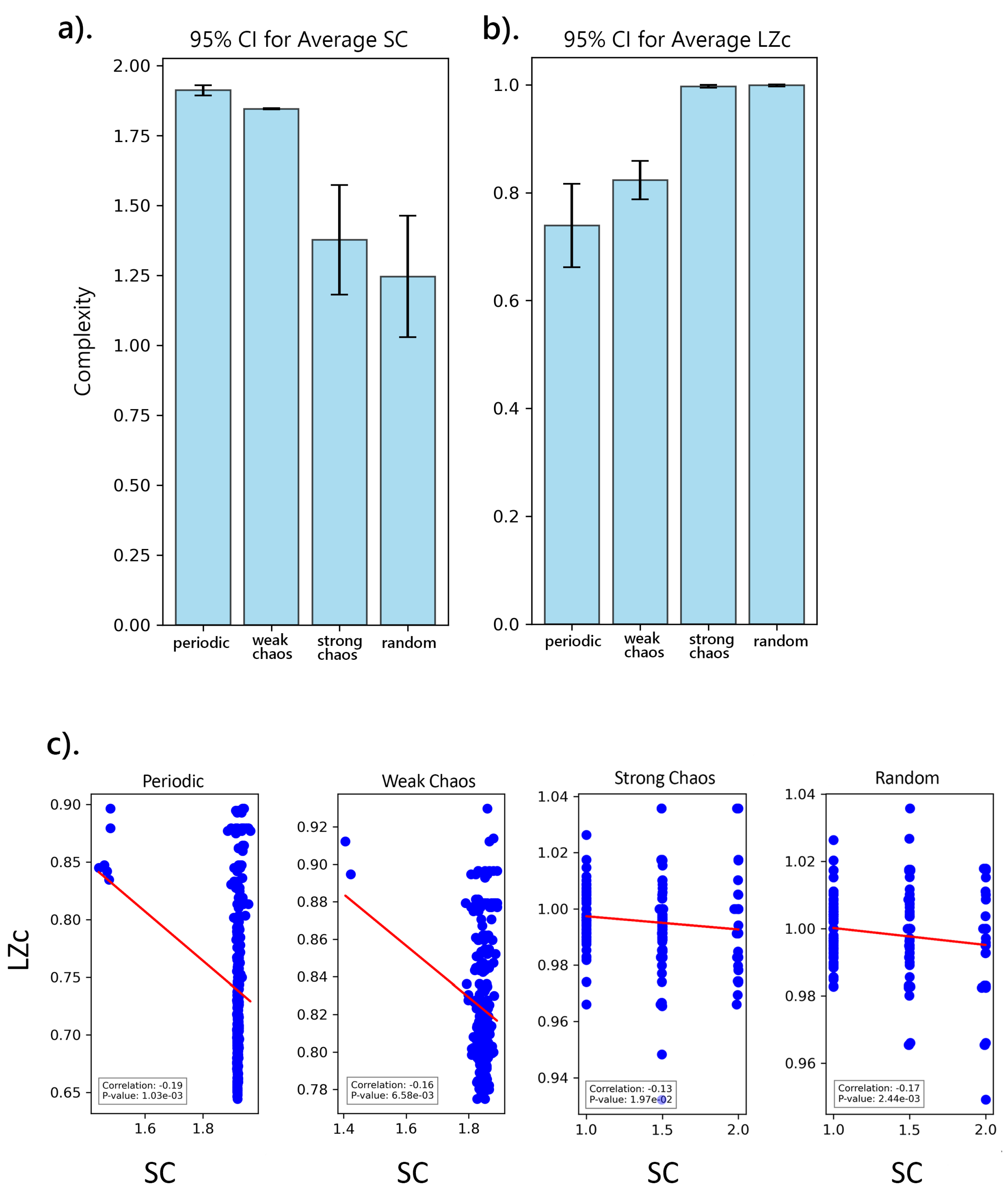

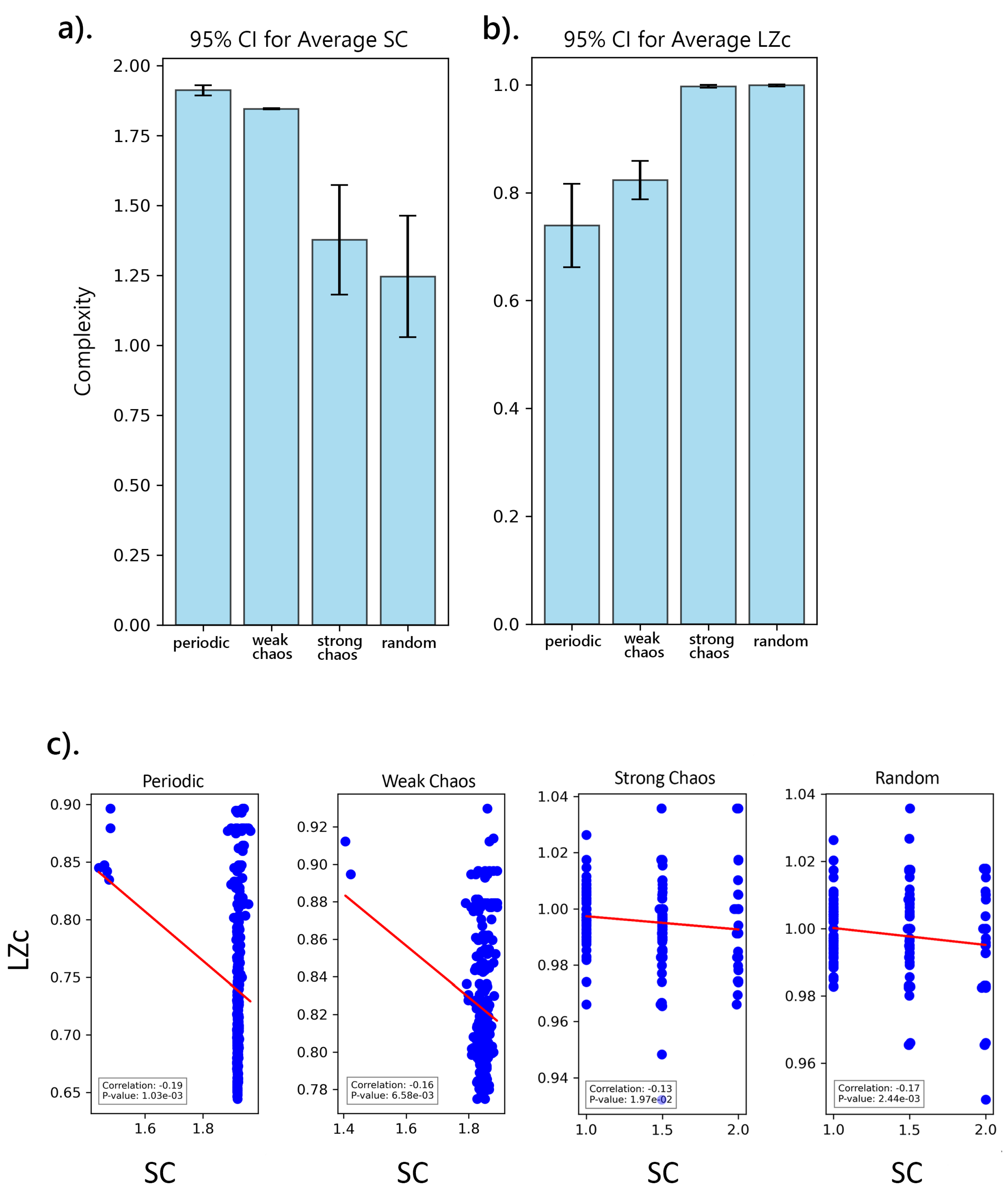

Additionally, the analysis across various dynamical behaviors—periodic, weak chaos, strong chaos, and random—revealed that SC is highest in periodic and weakly chaotic regimes, where structured, deterministic patterns are prevalent. In contrast, LZc increases with stronger chaos and randomness (

Figure 9(

a and

b)). This clearly demonstrates that SC primarily captures underlying structure and predictability within the data, rather than randomness. The negative correlations between LZc and SC across different regimes reflects the fundamental opposition between randomness and structure ((

Figure 9c). As sequences become more random, LZc increases because the data is harder to compress, while SC decreases as the underlying temporal structure and predictability are lost. LZc captures the randomness and entropy of the system, while SC measures the amount of information needed to predict future states. In more random regimes, the loss of temporal correlations reduces SC, whereas LZc rises due to the increased difficulty in describing the chaotic sequence. This inverse relationship highlights the trade-off between randomness and predictability in complex systems.

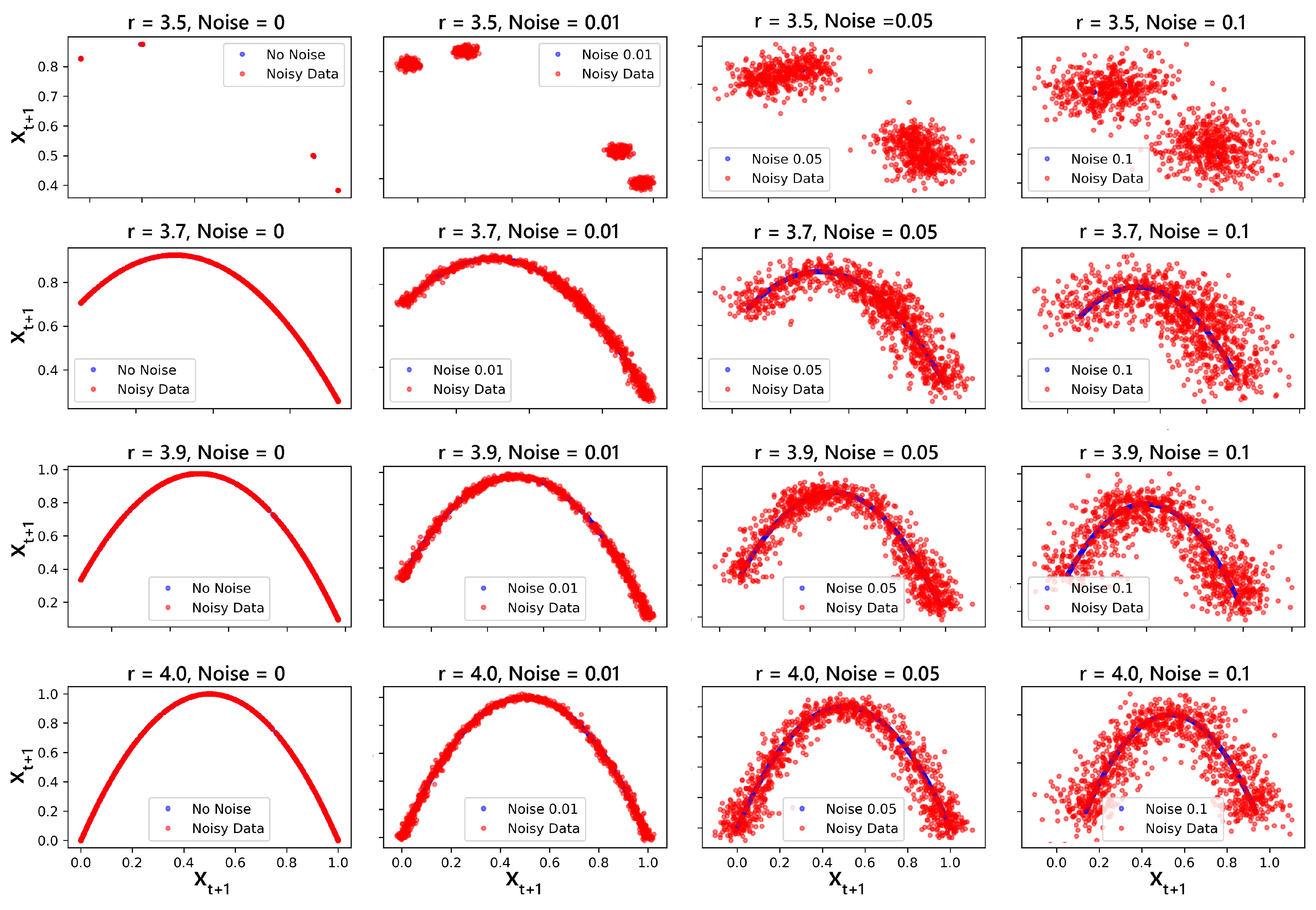

The introduction of noise was found to significantly influence the logistic map attractors, and thus the complexity. In

Figure 10, it is observed that as noise is introduced, the system’s behavior becomes less predictable, and the underlying structure becomes obscured by the fluctuations introduced by the noise. This makes it harder to identify the temporal correlations that SC relies on. The system becomes more random and less dependent on its previous states, hence requiring less information to describe its behavior, and therefore SC decreases. LZc remains relatively stable because the noise itself is random. Therefore, because the measure already accounts for randomness in the data, adding more noise does not significantly alter the level of compressibility.

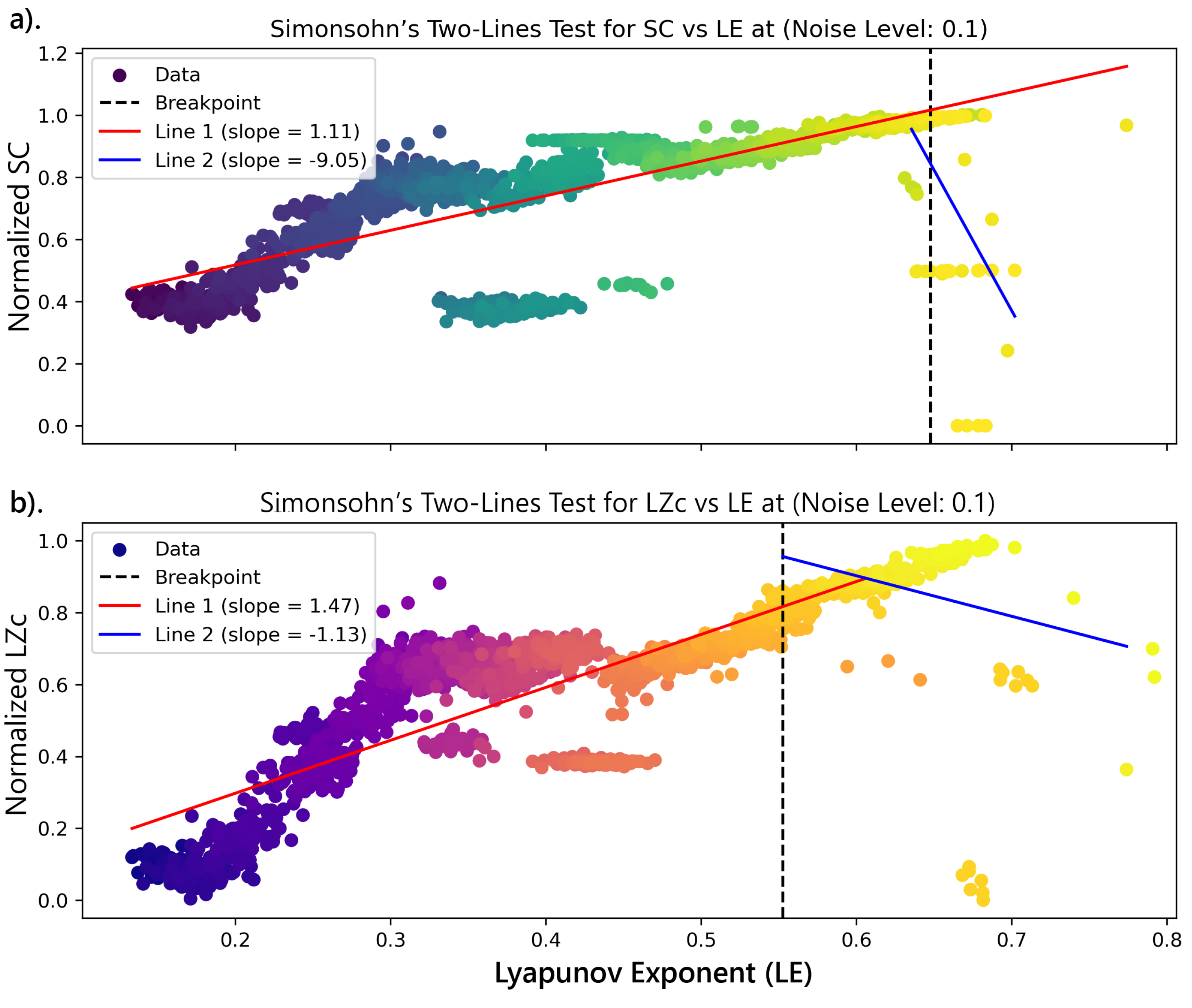

During conscious states, the brain operates near the edge-of-chaos criticality, enabling complex interactions and high information richness [

50,

51,

52]. In the analysis of complexity measures and chaoticity using the logistic map, the observed inverted U-shaped relationship (

Figure 12) mirrors this theoretical framework, with complexity measures peaking near specific chaotic conditions and then declining as the system moves further into chaos or stability.

As the system approaches the edge-of-chaos, SC increases because the system is in a critical state, balancing order and disorder, leading to intricate, structured patterns that are complex but still somewhat predictable. After crossing the edge-of-chaos into the fully chaotic regime (indicated by higher positive LE), SC begins to drop. This decrease happens because, in a highly chaotic system, the extreme unpredictability leads to a loss of structured, meaningful patterns, and the system behavior becomes more random, reducing the overall complexity of the structures. For LZc, as the system approaches the edge-of-chaos point, it increases due to rising randomness and new information. In the fully chaotic regime, LZc also decreases, albeit more gradually than SC, as the system becomes fully chaotic. This reflects that even in chaos, while new information is still being generated, the overall complexity in terms of randomness decreases as the system settles into a more homogeneous chaotic state.

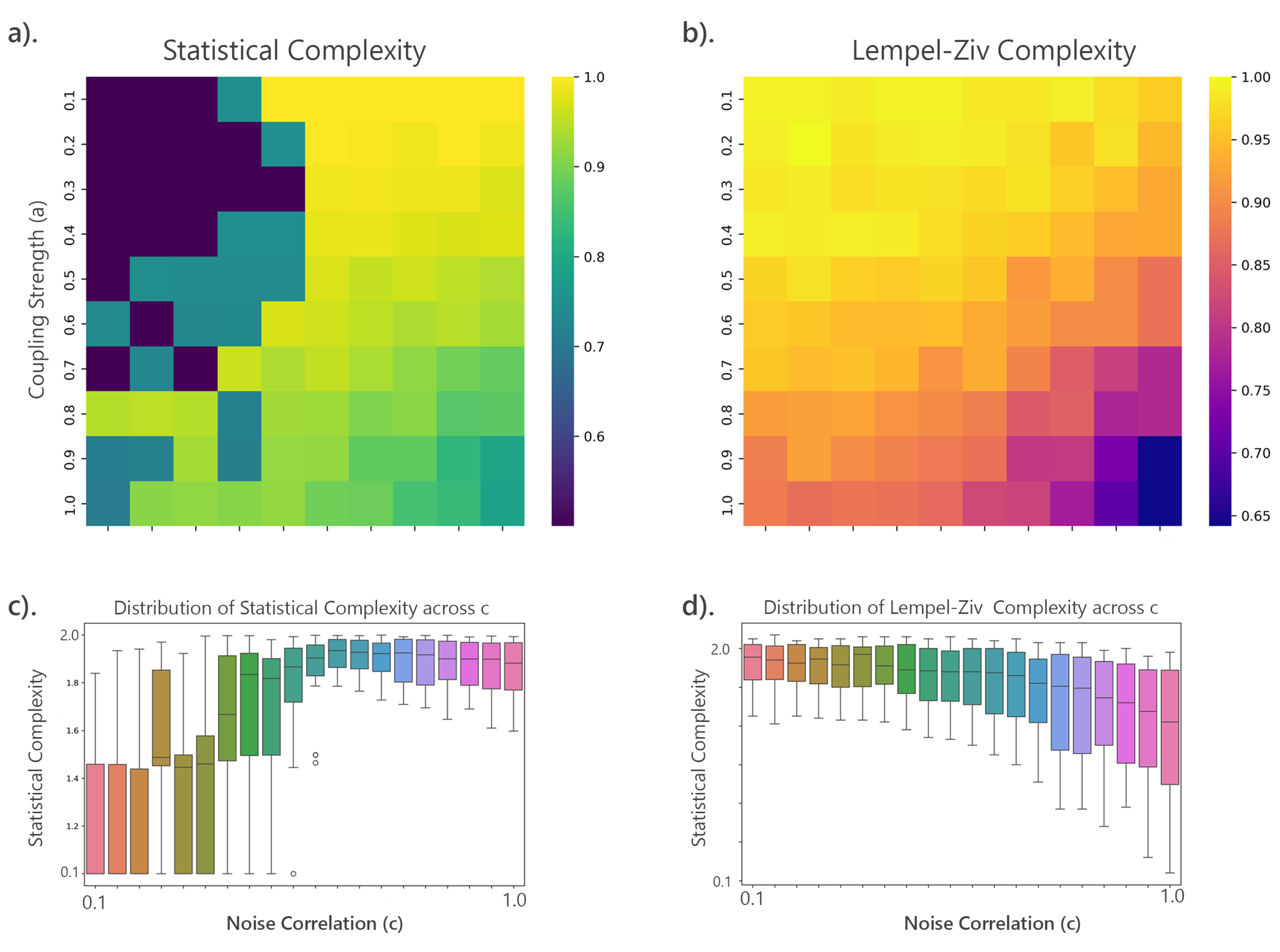

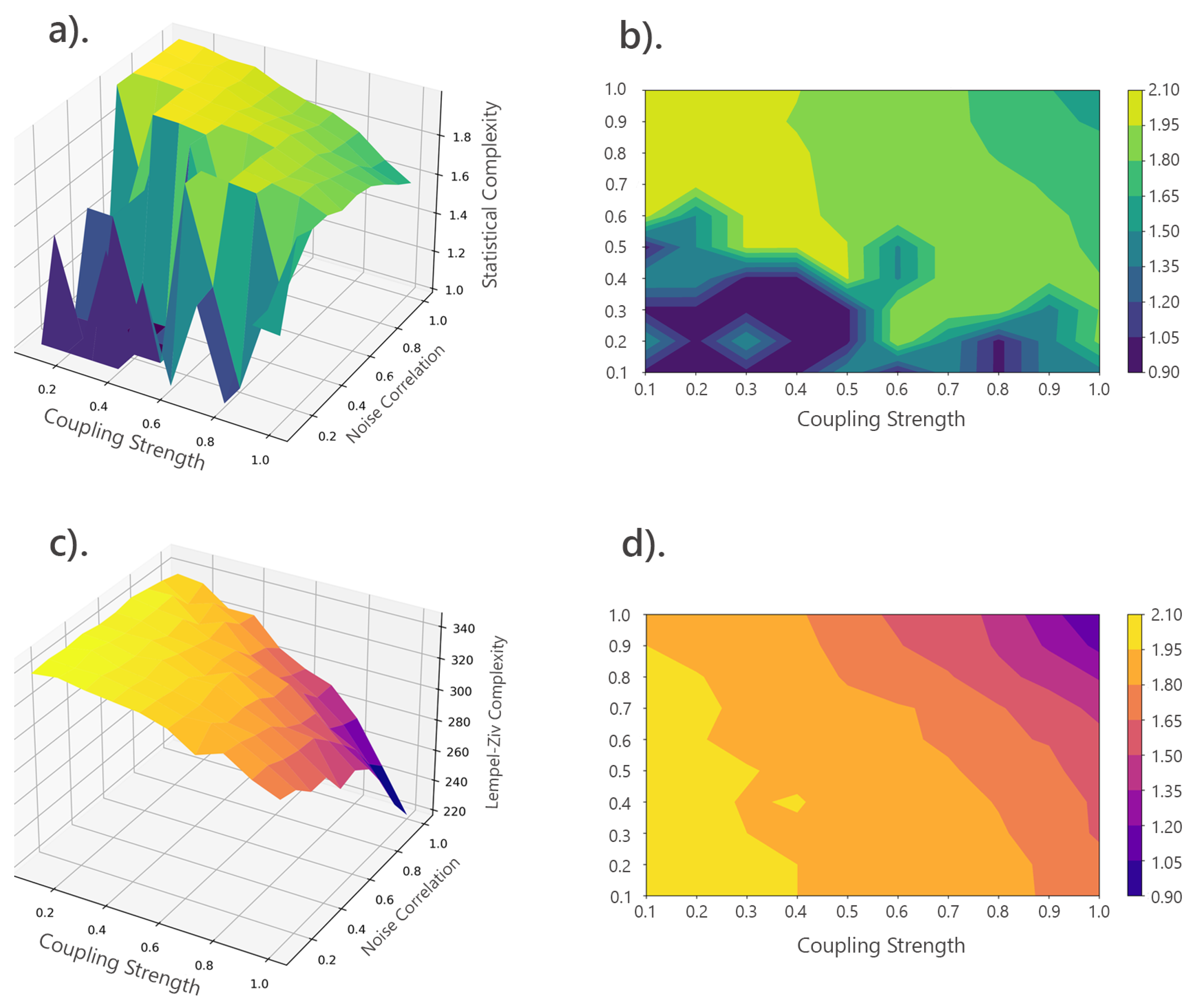

5.3. Interpretation of Results: MVAR Analysis

In the MVAR Model Analysis, the focus was on investigating the complexity of simulated data through the application of MVAR models and subsequent analysis of the residuals for complexity measures. SC and LZc revealed distinct patterns across varying MVAR parameters.

High SC values are observed where both coupling strength (a) and noise correlation (c) are either low or high. In regions where both a and c are low, the system retains more structure and predictability, which is captured by the higher SC values. This indicates that the system’s underlying dynamics are still coherent and well-structured. Interestingly, SC is also high when both a and c are high, suggesting that even when noise is high, the system still has some structured behavior that SC is sensitive to. This implies that SC captures more than just raw predictability—it is also sensitive to how the system processes complex interactions between noise and coupling strength. However, in intermediate ranges of coupling strength and noise correlation, SC values are low. This is because in these regions, the system is in a transition phase where the structure is neither fully predictable nor completely random, leading to lower SC values.

LZc, on the other hand, peaks in regions where the system is likely to exhibit complex but non-random behavior. This means that LZc can increase in non-random situations because it is sensitive not only to randomness but also to the intricacy of deterministic patterns that resist simple compression [

3,

29]. The low noise allows the coupling strength to dominate, leading to intricate patterns that are difficult to compress, thus leading to higher LZc complexity. When both noise and coupling strength are high, the system reaches a point where it becomes more structured in its unpredictability, leading to lower LZc. This suggests that LZc might capture the point where random noise and strong coupling create a more predictable chaotic pattern, which can still be compressed.

The MVAR model exhibits different forms of complexity depending on the interplay between coupling strength and noise correlation as shown in

Figure 13. The high SC in both low and high extremes of the parameter space implies that the system retains a significant amount of structure, even under high noise conditions, which could suggest resilience in the system’s dynamics. Whereas the LZc response indicates that while the system can become more complex and less predictable with increasing coupling strength and low noise, this complexity becomes more structured and less random when both parameters are high, leading to lower LZc complexity.

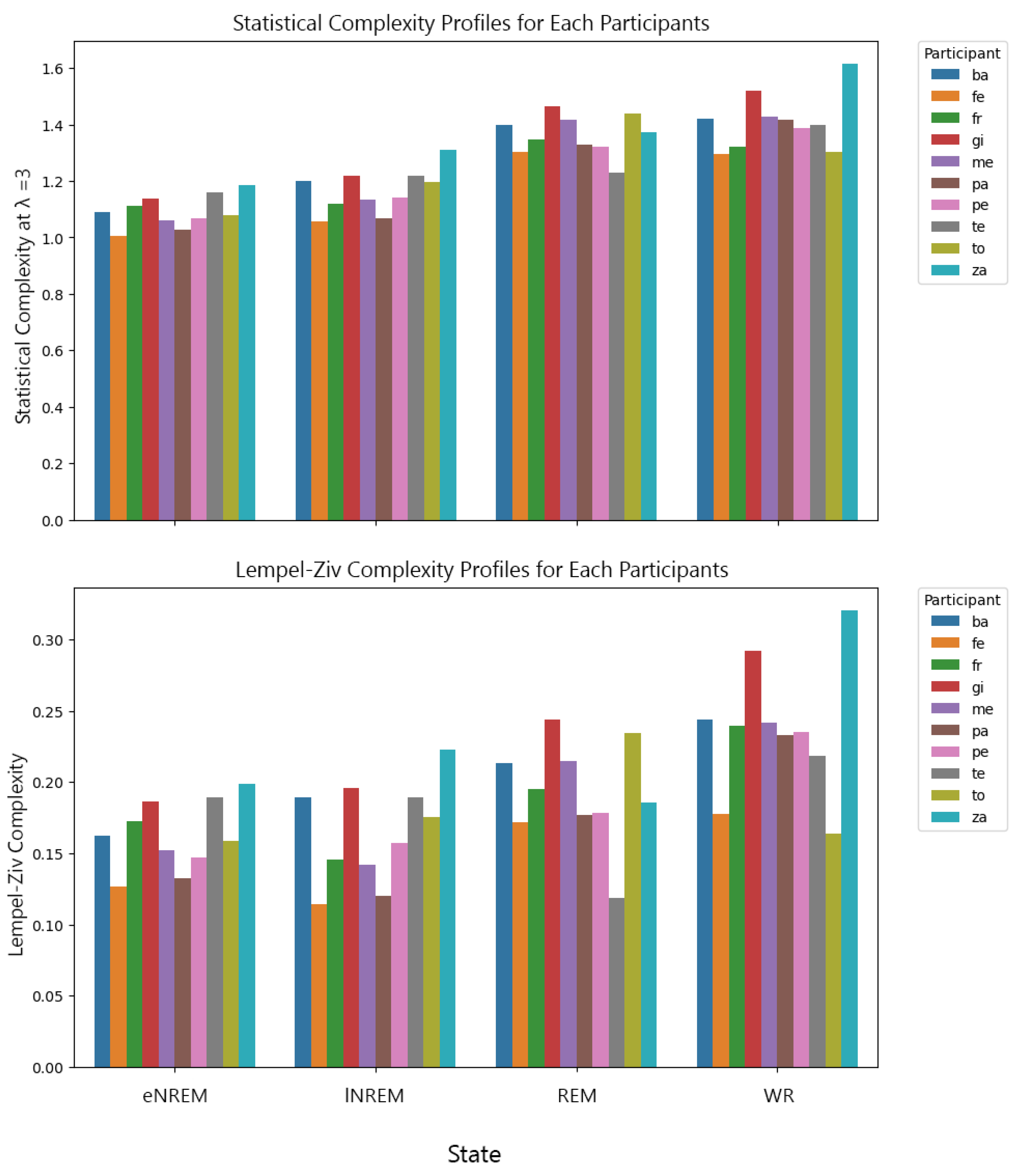

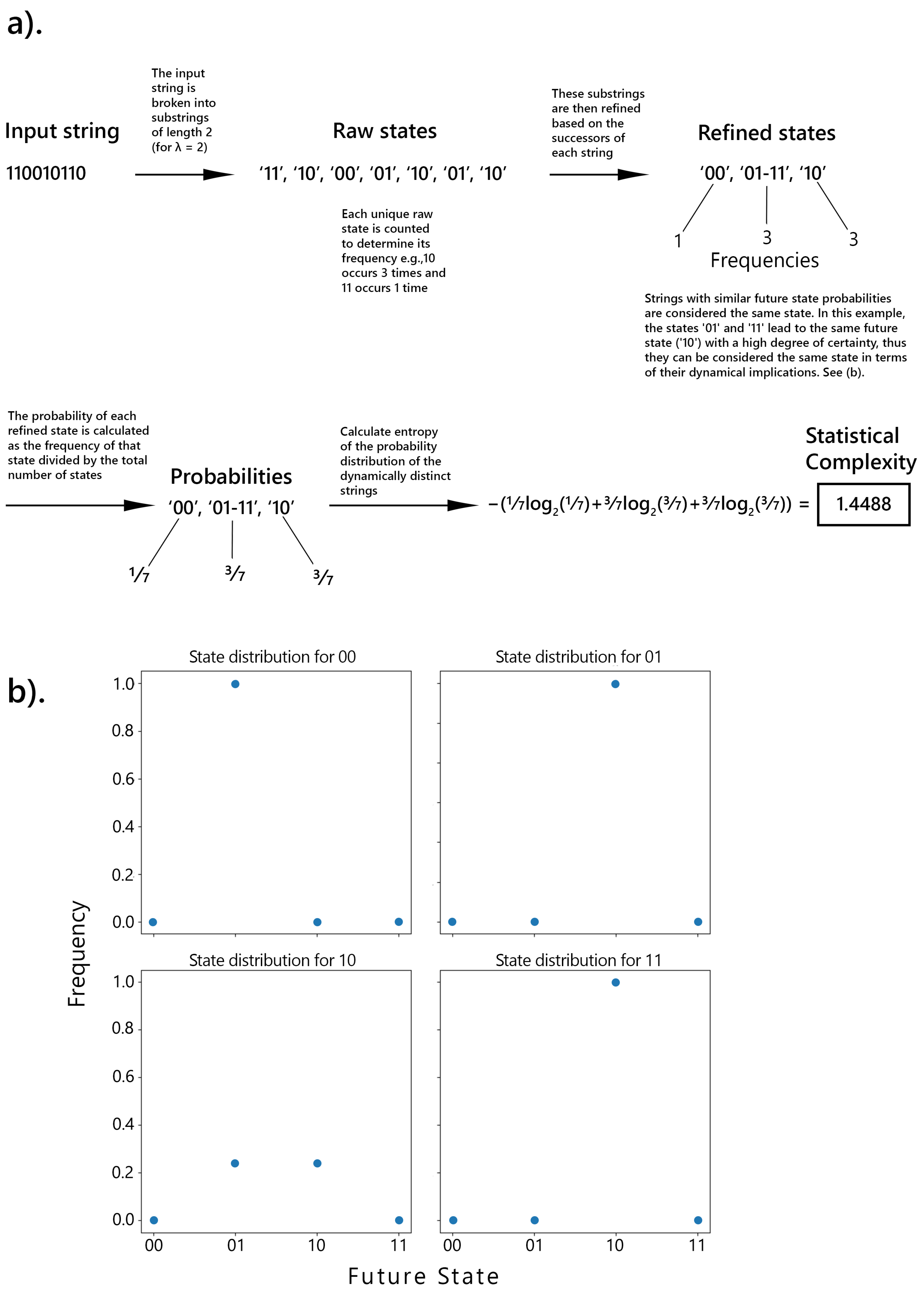

5.4. Interpretation of Results: Sleep Data

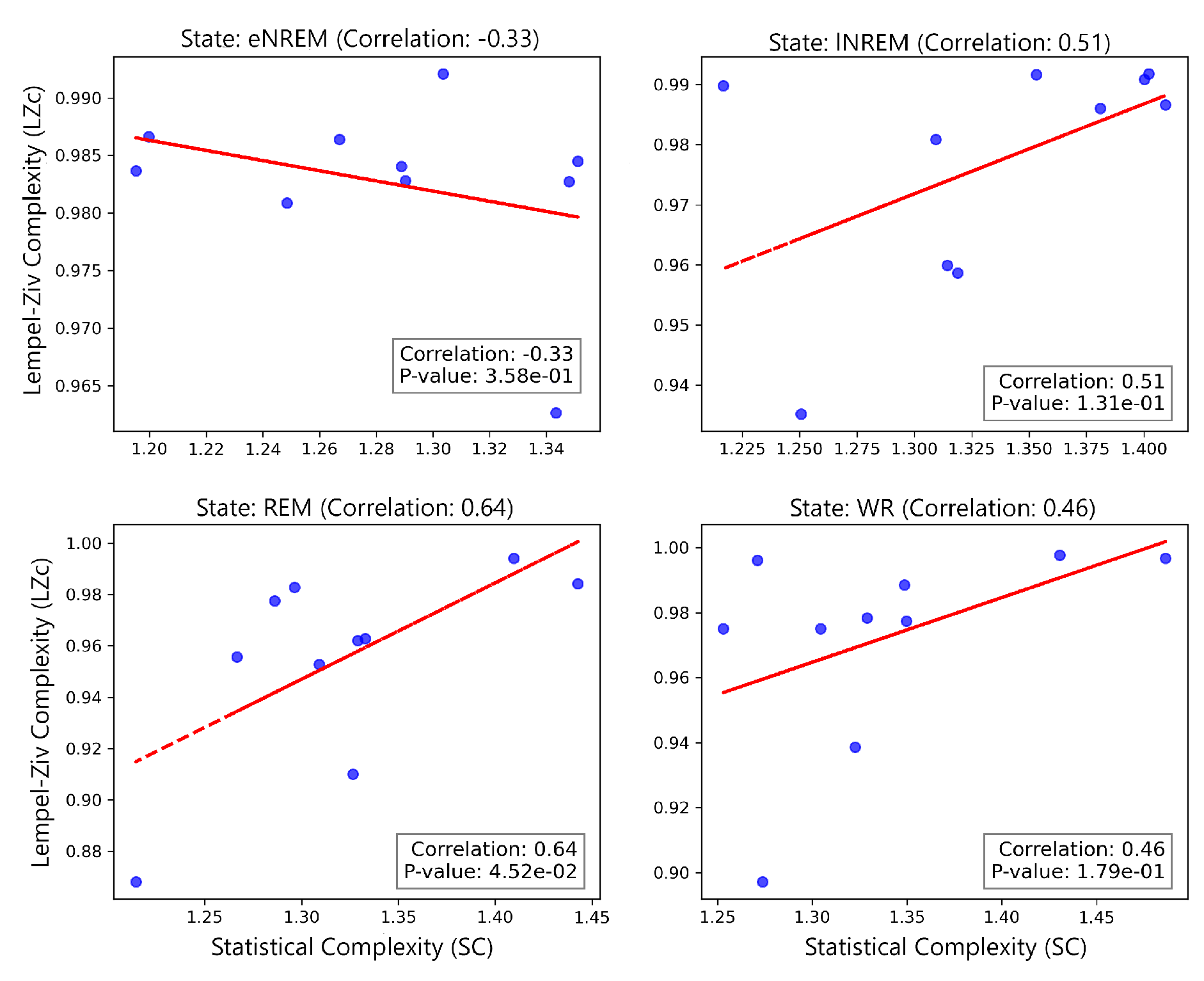

The analyses conducted on the sleep data aimed to evaluate the behavior of SC and LZc across different sleep stages including eNREM, lNREM, REM sleep, and wakeful rest (WR).

SC and LZc were consistently higher during WR and REM sleep, reflecting increased brain dynamical diversity during these states. SC is lowest during eNREM and increases toward wakeful rest. As the brain transitions to REM sleep and wakefulness, its capacity to process complex, temporally structured information increases. This means that there is an increase in the brain’s neural dynamical diversity in these stages [

13,

32]. This aligns with the findings from Munoz

et al. [

4], where higher SC was associated with more structured, awake states compared to the less structured, anesthetized states of Drosophila flies.

LZc also increases from eNREM to wakeful rest, albeit to a different degree compared to SC. This suggests that the brain signal becomes less compressible and more random as it transitions to more active states, which could be associated with higher temporal asymmetry. This also means that wakefulness involves more complex, temporally asymmetric information processing [

4].

The varying correlation strengths across different states between SC and LZc suggests that they are capturing different aspects of the dynamics, rather than entirely equivalent properties. This highlights the state-dependent nature of neural dynamics during sleep. Certain states may exhibit more deterministic or structured dynamics (leading to higher SC), while others might reflect more chaotic or random behavior (leading to higher LZc). The state-dependent nature of these correlations is indicative of different underlying neural processes that are active in each state [

4,

15].

The consequence of the difference in complexity observed between sleep stages is that different states of consciousness can be mapped to varying levels of brain entropy. These results contribute to the growing evidence that global states of consciousness can be differentiated using measures of signal diversity [

7,

64], supporting the entropic brain hypothesis, which posits that neurophysiological time series from unconscious states typically exhibit lower temporal differentiation compared to awake states [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

32,

37,

65]. In contrast, states induced by psychedelics like ketamine and psilocybin tend to show higher temporal differentiation [

14,

17,

32].

5.5. Implications for Complexity Science and Consciousness Research

The results from these analyses reveal crucial insights into complexity science and consciousness research. Statistical complexity (SC) and Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc) measures provide complementary perspectives on system behavior, with SC being sensitive to the structure and predictability of a system, and LZc reflecting its randomness and entropy.

SC and LZc respond differently to varying conditions, highlighting their distinct roles in capturing the dynamics of complex systems. For instance, in random data, SC decreases with increasing sequence length, reflecting reduced system complexity as patterns become more repetitive. Conversely, LZc remains stable, emphasizing its robustness in measuring inherent randomness regardless of sequence length. This divergence suggests that SC is more effective at detecting changes in complexity due to structural variations, while LZc consistently captures the system’s overall entropy.

In consciousness research, these complexity measures map distinct patterns of brain activity across different states of consciousness, such as sleep stages and wakefulness.[

7,

64] Higher SC and LZc during wakefulness and REM sleep indicate a brain state that is highly structured and dynamically varied, whereas lower complexity in deeper sleep stages aligns with reduced cognitive functions, akin to states of anesthesia. This pattern supports the entropic brain hypothesis.

The concept of temporal differentiation—how varied a time series is over time—and temporal asymmetry—differences in statistical properties when time is reversed—are key to understanding consciousness. High SC and LZc correlate with high temporal differentiation and asymmetry, characteristics of heightened consciousness, such as in wakefulness or under psychedelics [

4]. These states involve complex, directional information processing, making temporal differentiation and asymmetry potential markers of conscious awareness.

The MVAR Model analysis highlights SC as an indicator of system resilience, showing that SC remains high even under high noise or coupling strength, suggesting that complex systems can retain structure and predictability despite disturbances. This resilience might reflect the brain’s ability to maintain cognitive function under challenging conditions.

The logistic map analysis illustrates how systems transition from order to chaos, with SC declining sharply as the system becomes fully chaotic, losing structured complexity. LZc however increases, indicating heightened randomness. This transition can be likened to shifts in consciousness where the brain moves from organized to chaotic states, as seen in certain mental health conditions.[

66,

67,

68,

69]

Overall, these findings underscore the importance of SC and LZc in understanding the dynamics of complex systems and consciousness. They suggest that by tracking these measures, it may be possible to monitor and even modulate states of consciousness, offering valuable insights for both theoretical research and practical applications in neuroscience and mental health.

5.6. Limitations of the Study

While this study provides valuable insights into the application of complexity measures to different dynamical regimes and states of consciousness, several limitations should be acknowledged.

One limitation of statistical complexity is its behavior in relation to randomness. While theoretically, statistical complexity is expected to follow an inverted U-shape function relative to randomness, practical findings with finite data showed that it can appear maximal for highly random data. This necessitates supplementing the measure with an analysis of the number of states in the -machine, which decreases with increased randomness. Without this additional analysis, it is challenging to accurately interpret changes in statistical complexity, as they could result from shifts in the diversity of statistical interactions rather than merely the level of randomness.

The analysis of sleep data also has limitations. iEEG recordings are influenced by external factors like muscle movements and noise, which can affect complexity measures despite preprocessing. Additionally, iEEG captures only cortical activity, missing deeper brain structures involved in consciousness. The absence of a hypnogram prevents detailed analysis of how complexity measures change over time within each sleep state, limiting the ability to track transitions between states.

Moreover, the study’s cross-sectional design limits causal inferences between complexity measures and consciousness states. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore how complexity evolves over time and in response to interventions, offering deeper insights into brain complexity and consciousness.

In conclusion, while the study advances the understanding of complexity measures in neural data, these limitations highlight the need for further research to refine methodologies, improve findings’ robustness, and expand complexity measures’ applicability.

5.7. Future Research Directions

Future research could delve deeper into the roles of temporal asymmetry and temporal differentiation in distinguishing different states of consciousness. Exploring how these properties manifest, especially in altered states induced by psychedelics, may uncover new insights into the fundamental nature of consciousness and the brain’s information processing capabilities.

Another promising direction involves applying SC and LZc measures to clinical patients with neurological disorders. These complexity measures could potentially serve as biomarkers for disease progression or treatment response in conditions such as epilepsy, schizophrenia, and neurodegenerative diseases.

The application of SC and LZc measures also extends beyond neuroscience, offering valuable insights in fields like economics, ecology, and social sciences, where they could shed light on how complex systems maintain structure and adapt to changes. Additionally, integrating these complexity measures with machine learning techniques could enhance predictive modeling of consciousness states. For instance, machine learning models trained on SC and LZc data could predict transitions between different states of consciousness, providing tools for real-time monitoring and intervention in clinical settings.

Pursuing these research avenues will deepen our understanding of the principles that govern complexity across both natural and artificial systems, with significant implications for advancing the science of consciousness and other disciplines.

6. Conclusion

This work explored complexity measures across different datasets: random data, logistic map simulations, MVAR model simulations, and real-word data from iEEG recordings. The primary objective was to understand how these measures can reveal insights into the nature of consciousness and the dynamics of complex systems.

The findings of this dissertation underscore the utility of complexity measures in understanding the intricate dynamics of both theoretical models and real physiological data. The distinct behaviors of SC and LZc across different dynamical regimes and states of consciousness highlight their complementary nature in capturing various aspects of system complexity. SC effectively captures the minimal information required for optimal prediction, reflecting the degree of structured information processing and temporal correlations within the neural signals. This makes SC particularly adept at distinguishing between different levels of consciousness in the sleep data analysis for example, as it highlights the organized and complex activity associated with wakefulness compared to early night NREM sleep. Conversely, LZc measures the diversity of patterns within the data and tends to register higher complexity in more random processes, without accounting for temporal structure or correlations. While LZc provides insight into the variability of the neural signals, it is less sensitive to the structured information processing that characterizes conscious states.

In the context of consciousness research, these findings highlight the nuanced differences in brain dynamics across different states, from deep sleep to wakefulness. The observed increases in both SC and LZc during wakefulness and REM sleep indicate that these states are characterized by greater neural dynamical diversity, complexity, and temporal differentiation, aligning with higher levels of consciousness [

4,

13,

32,

41].

These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of how the brain transitions between different states of consciousness and the role that complexity plays in these processes. As we continue to explore the intricate relationship between complexity and consciousness, the use of these measures could provide valuable tools for advancing our knowledge in both theoretical research and practical applications, such as monitoring and potentially modulating states of consciousness in clinical settings.

Figure 1.

Statistical Complexity (SC) calculation example (for

and

).

a) demonstrates the segmentation of a binary string into substrings of length 2, followed by refinement based on the distribution of successor states. Substrings with highly similar successor distributions are combined into the same refined state. For example, ’01’ and ’11’ are grouped together as they both predict the next state with similar certainty (difference of 0.00, within the

threshold). This concept is further illustrated in

b), where the state distributions and transitions clarify the grouping process [

32].

Figure 1.

Statistical Complexity (SC) calculation example (for

and

).

a) demonstrates the segmentation of a binary string into substrings of length 2, followed by refinement based on the distribution of successor states. Substrings with highly similar successor distributions are combined into the same refined state. For example, ’01’ and ’11’ are grouped together as they both predict the next state with similar certainty (difference of 0.00, within the

threshold). This concept is further illustrated in

b), where the state distributions and transitions clarify the grouping process [

32].

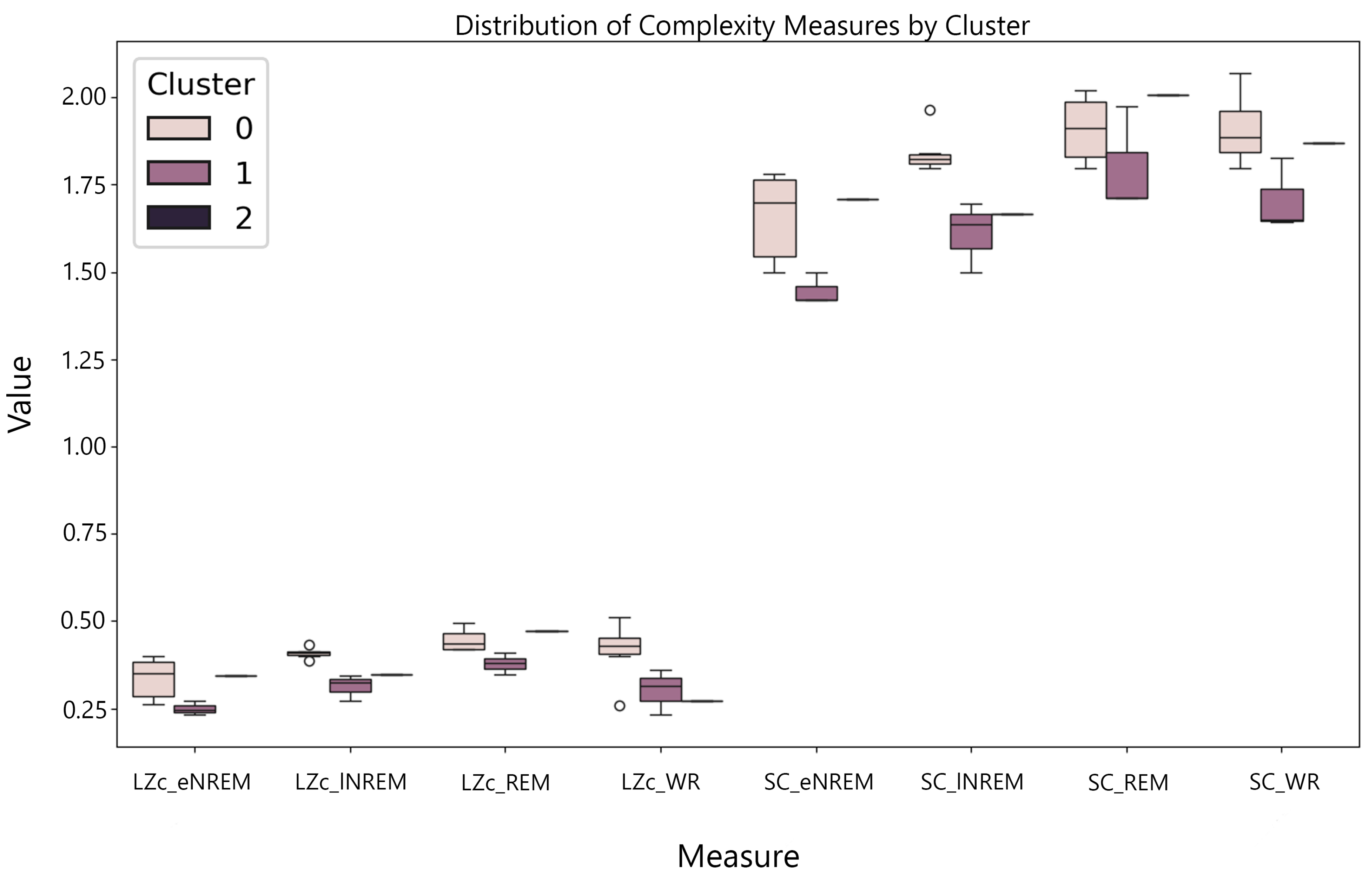

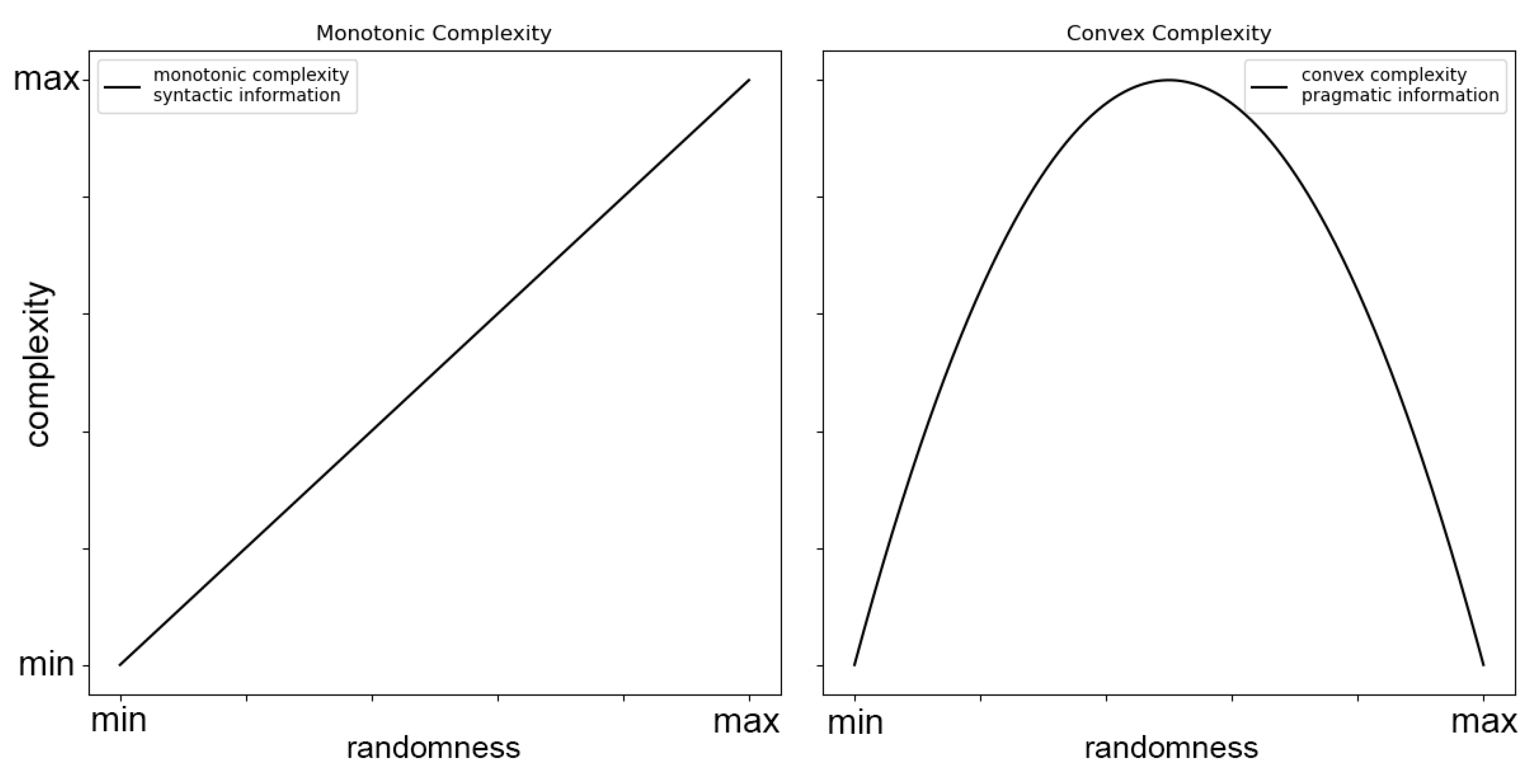

Figure 2.

Two classes of complexity measures: monotonic and convex. Monotonic complexity, related to syntactic information, increases with randomness. In contrast, convex complexity, associated with pragmatic information, peaks at intermediate levels of randomness and diminishes towards zero for both complete order and complete randomness, highlighting its dependence on meaningful structure [

33].

Figure 2.

Two classes of complexity measures: monotonic and convex. Monotonic complexity, related to syntactic information, increases with randomness. In contrast, convex complexity, associated with pragmatic information, peaks at intermediate levels of randomness and diminishes towards zero for both complete order and complete randomness, highlighting its dependence on meaningful structure [

33].

Figure 3.

Lempel-Ziv Complexity Computation Algorithm. From the start of the string, each character is analyzed and added to a "search string." If this search string is identical to a previously discovered string, the next character in the sequence is added to the search string. If it is not, the search string is added to the list of previously discovered strings, and then the search string is "reset" to an empty string before moving on to the next character in the sequence. This process repeats until the end of the sequence is reached.

Figure 3.

Lempel-Ziv Complexity Computation Algorithm. From the start of the string, each character is analyzed and added to a "search string." If this search string is identical to a previously discovered string, the next character in the sequence is added to the search string. If it is not, the search string is added to the list of previously discovered strings, and then the search string is "reset" to an empty string before moving on to the next character in the sequence. This process repeats until the end of the sequence is reached.

Figure 4.

Bifurcation Diagram of the Logistic Map. The attractor values for each value of r are shown along the corresponding vertical line. This diagram illustrates the transition from stable, periodic behavior to chaotic dynamics as r increases, showcasing the complex behavior inherent in the logistic map as a nonlinear system.

Figure 4.

Bifurcation Diagram of the Logistic Map. The attractor values for each value of r are shown along the corresponding vertical line. This diagram illustrates the transition from stable, periodic behavior to chaotic dynamics as r increases, showcasing the complex behavior inherent in the logistic map as a nonlinear system.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of electrode positions in MNI coordinate space, highlighting their clustering within specific brain areas.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of electrode positions in MNI coordinate space, highlighting their clustering within specific brain areas.

Figure 6.

Complexity measures vs sequence length a). Statistical Complexity for and : Average SC values decrease as sequence length increases. b). LZc is relatively stable across varying sequence lengths. c). Mean SC and LZc with varying sequence length

Figure 6.

Complexity measures vs sequence length a). Statistical Complexity for and : Average SC values decrease as sequence length increases. b). LZc is relatively stable across varying sequence lengths. c). Mean SC and LZc with varying sequence length

Figure 7.

Impact of ’Future’ State Definition on Statistical Complexity Across Sequence Lengths. In a), the future is defined as the next state, while in b), it is defined as the immediate next binary state. Each plot compares different memory lengths () and tolerance levels (), showing that complexity generally decreases with increasing sequence length, with more significant reductions at higher tolerance levels. The comparison reveals that predicting a single future state generally requires less memory, resulting in lower complexity, whereas predicting multiple future states involves greater structural richness, reflected in higher initial complexity values.

Figure 7.

Impact of ’Future’ State Definition on Statistical Complexity Across Sequence Lengths. In a), the future is defined as the next state, while in b), it is defined as the immediate next binary state. Each plot compares different memory lengths () and tolerance levels (), showing that complexity generally decreases with increasing sequence length, with more significant reductions at higher tolerance levels. The comparison reveals that predicting a single future state generally requires less memory, resulting in lower complexity, whereas predicting multiple future states involves greater structural richness, reflected in higher initial complexity values.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Complexity Measures and Lyapunov Exponent Across r-Values for the Logistic Map. The plots illustrate the behavior of various complexity measures—Statistical Complexity, Lempel-Ziv Complexity, Kolmogorov Complexity, and Approximate Entropy—along with the Lyapunov Exponent as functions of the r-value in the logistic map. Panel (a) shows the normalized values of Statistical Complexity, Lempel-Ziv Complexity, and the Lyapunov Exponent. Panel (b) includes additional comparisons with Kolmogorov Complexity and Approximate Entropy. The observed trends highlight the onset and development of chaos as r increases, with different complexity measures capturing distinct aspects of the system’s dynamics.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Complexity Measures and Lyapunov Exponent Across r-Values for the Logistic Map. The plots illustrate the behavior of various complexity measures—Statistical Complexity, Lempel-Ziv Complexity, Kolmogorov Complexity, and Approximate Entropy—along with the Lyapunov Exponent as functions of the r-value in the logistic map. Panel (a) shows the normalized values of Statistical Complexity, Lempel-Ziv Complexity, and the Lyapunov Exponent. Panel (b) includes additional comparisons with Kolmogorov Complexity and Approximate Entropy. The observed trends highlight the onset and development of chaos as r increases, with different complexity measures capturing distinct aspects of the system’s dynamics.

Figure 9.

95% confidence intervals for the averaged values of a) Statistical Complexity and b) Lempel-Ziv Complexity across different dynamical regimes of the logistic map: Periodic (), Weak Chaos (), Strong Chaos (), and Random. Statistical Complexity is more pronounced in the periodic and weak chaos regimes, capturing the underlying structure and predictability of the sequences. In contrast, Lempel-Ziv Complexity increases in strong chaos and random sequences, reflecting the higher levels of randomness and reduced compressibility in these behaviors c). Correlation between LZc and SC across Different Bifurcation Parameters. The strength and direction of the correlation vary between the regimes. Negative correlations are observed across all regimes, suggesting a potential inverse relationship between LZc and SC, with statistically significant p-values in most cases. The periodic and weak chaos regimes exhibit moderate negative correlations, while the strong chaos and random regimes show weaker correlations.

Figure 9.

95% confidence intervals for the averaged values of a) Statistical Complexity and b) Lempel-Ziv Complexity across different dynamical regimes of the logistic map: Periodic (), Weak Chaos (), Strong Chaos (), and Random. Statistical Complexity is more pronounced in the periodic and weak chaos regimes, capturing the underlying structure and predictability of the sequences. In contrast, Lempel-Ziv Complexity increases in strong chaos and random sequences, reflecting the higher levels of randomness and reduced compressibility in these behaviors c). Correlation between LZc and SC across Different Bifurcation Parameters. The strength and direction of the correlation vary between the regimes. Negative correlations are observed across all regimes, suggesting a potential inverse relationship between LZc and SC, with statistically significant p-values in most cases. The periodic and weak chaos regimes exhibit moderate negative correlations, while the strong chaos and random regimes show weaker correlations.

Figure 10.

Phase-space plots depicting the attractor structures of the logistic map for various values of the parameter r and different noise levels (0, 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1). The plots illustrate how the introduction of noise affects the system behavior, leading to a dispersion of the attractor points and increasing complexity. As the noise level increases, the attractors become more diffuse, indicating a transition from deterministic chaos to stochastic behavior, particularly evident in highly chaotic regions such as .

Figure 10.

Phase-space plots depicting the attractor structures of the logistic map for various values of the parameter r and different noise levels (0, 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1). The plots illustrate how the introduction of noise affects the system behavior, leading to a dispersion of the attractor points and increasing complexity. As the noise level increases, the attractors become more diffuse, indicating a transition from deterministic chaos to stochastic behavior, particularly evident in highly chaotic regions such as .

Figure 11.

Complexity vs Lyapunov Exponent for Logistic Map, Segment Length=1000.

Figure 11.

Complexity vs Lyapunov Exponent for Logistic Map, Segment Length=1000.

Figure 12.

Analysis of Complexity Measures with Lyapunov Exponent Using Simonsohn’s Two-Lines Test: (a) and (b) illustrate the relationship between Lempel-Ziv complexity and statistical complexity and the Lyapunov exponent in logistic map dynamics. Simonsohn’s two-lines test identifies a breakpoint in both cases. In a), the Lempel-Ziv complexity shows a consistent slight positive trend across the identified breakpoint. In b), the statistical complexity exhibits a change from a moderate positive relationship to a steep negative relationship at the breakpoint, suggesting a transition in the system behavior as chaoticity increases.

Figure 12.

Analysis of Complexity Measures with Lyapunov Exponent Using Simonsohn’s Two-Lines Test: (a) and (b) illustrate the relationship between Lempel-Ziv complexity and statistical complexity and the Lyapunov exponent in logistic map dynamics. Simonsohn’s two-lines test identifies a breakpoint in both cases. In a), the Lempel-Ziv complexity shows a consistent slight positive trend across the identified breakpoint. In b), the statistical complexity exhibits a change from a moderate positive relationship to a steep negative relationship at the breakpoint, suggesting a transition in the system behavior as chaoticity increases.

Figure 13.

Heatmaps of Complexity measures across coupling Strength and Noise Correlation in MVAR Models (a). High SC regions are observed where both coupling strength and noise correlation are either low or high, while low SC regions are found in intermediate ranges, suggesting a complex interplay between these parameters. (b) High LZc complexity found in regions with low noise correlation and moderate to high coupling strength, whereas low complexity occurs when both parameters are high. (c) and (d) illustrate the variability and distribution of SC and LZc complexities across different levels of noise correlation, highlighting the trends and the spread of complexity values within each range of noise correlation.

Figure 13.

Heatmaps of Complexity measures across coupling Strength and Noise Correlation in MVAR Models (a). High SC regions are observed where both coupling strength and noise correlation are either low or high, while low SC regions are found in intermediate ranges, suggesting a complex interplay between these parameters. (b) High LZc complexity found in regions with low noise correlation and moderate to high coupling strength, whereas low complexity occurs when both parameters are high. (c) and (d) illustrate the variability and distribution of SC and LZc complexities across different levels of noise correlation, highlighting the trends and the spread of complexity values within each range of noise correlation.

Figure 14.

The distribution of statistical complexity (SC) and Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc) as functions of coupling strength (a) and noise correlation (c) in the MVAR model. The SC plots ((a) and (b)) highlight significant variations in complexity, with notable peaks and troughs indicating areas of high and low complexity. In contrast, the LZc complexity plots ((c) and (d)) exhibit a smoother gradient, with a general trend of decreasing complexity as noise correlation increases. The contour maps provide a detailed view of the complexity landscapes, emphasizing the system’s non-linear dynamics and sensitivity to parameter changes.

Figure 14.

The distribution of statistical complexity (SC) and Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc) as functions of coupling strength (a) and noise correlation (c) in the MVAR model. The SC plots ((a) and (b)) highlight significant variations in complexity, with notable peaks and troughs indicating areas of high and low complexity. In contrast, the LZc complexity plots ((c) and (d)) exhibit a smoother gradient, with a general trend of decreasing complexity as noise correlation increases. The contour maps provide a detailed view of the complexity landscapes, emphasizing the system’s non-linear dynamics and sensitivity to parameter changes.

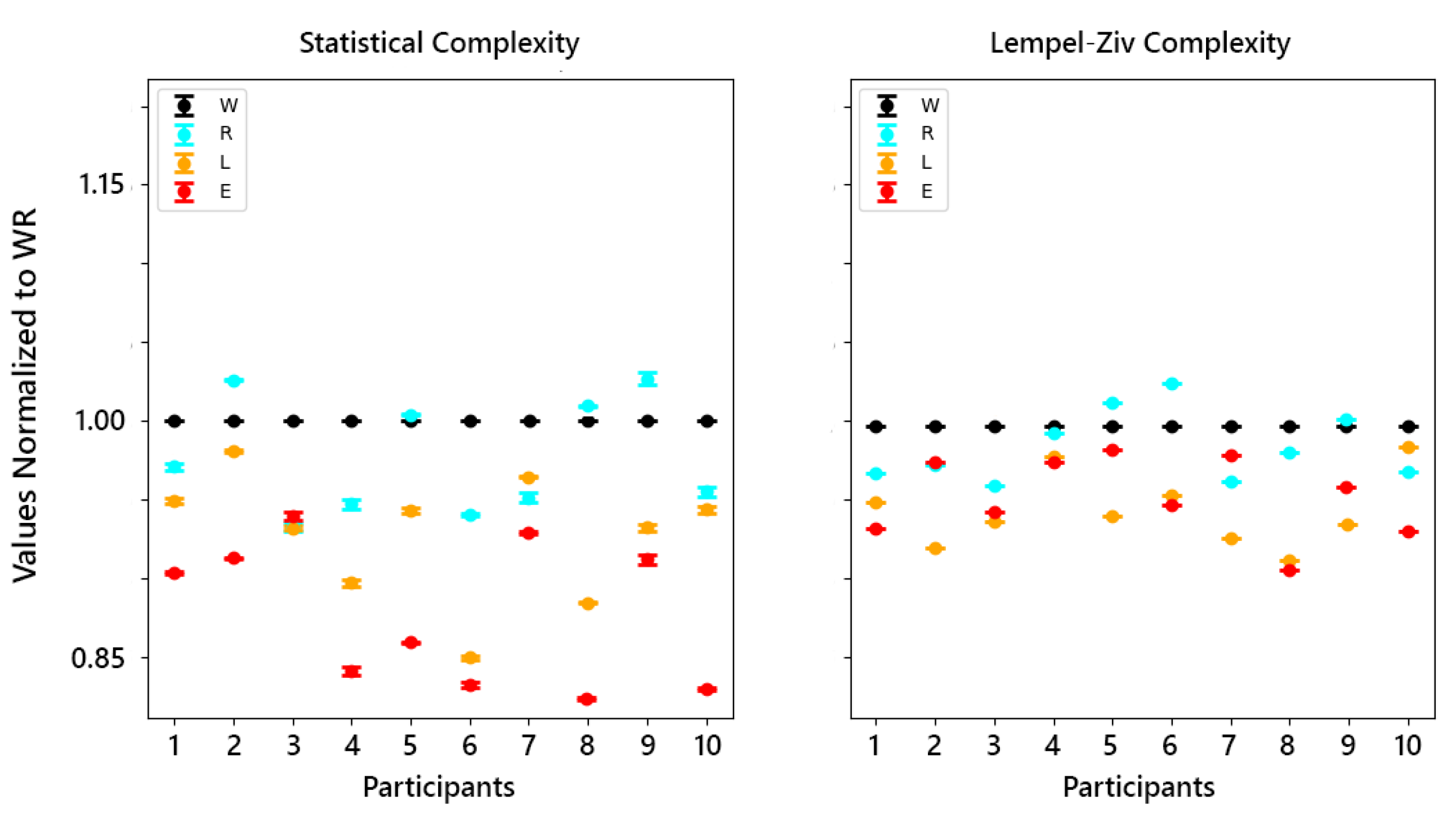

Figure 15.

Normalized values of Statistical Complexity (left panel) and Lempel-Ziv Complexity (right panel) across different states of consciousness (WR (W), REM (R), lNREM (L), eNREM (E)) for the 10 participants. The values are normalized to WR, allowing for comparison across different states. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) calculated across all 2-second segments within each state for each participant. The results show a noticeable decrease in complexity measures during eNREM and lNREM compared to WR, while REM sleep exhibits complexity levels closer to WR.

Figure 15.

Normalized values of Statistical Complexity (left panel) and Lempel-Ziv Complexity (right panel) across different states of consciousness (WR (W), REM (R), lNREM (L), eNREM (E)) for the 10 participants. The values are normalized to WR, allowing for comparison across different states. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) calculated across all 2-second segments within each state for each participant. The results show a noticeable decrease in complexity measures during eNREM and lNREM compared to WR, while REM sleep exhibits complexity levels closer to WR.

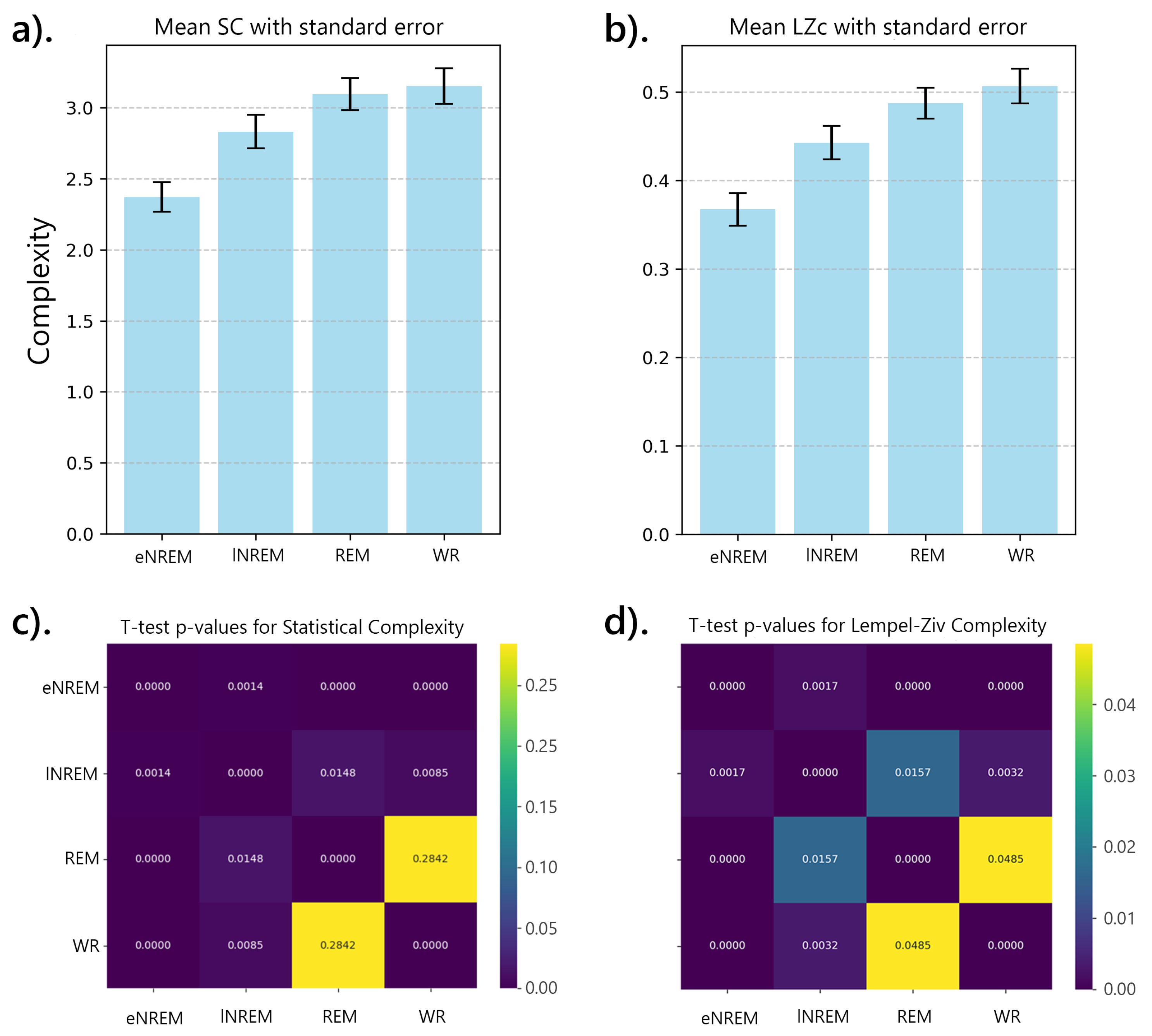

Figure 16.

Mean complexity measures with standard error across the sleep stages. a). displays the Grand Mean Statistical Complexity b).) shows the Grand Mean Lempel-Ziv Complexity for the same sleep stages. Statistical Complexity increases from eNREM to WR, with the most significant changes observed between early sleep and wakefulness. Lempel-Ziv Complexity also rises from eNREM to WR, reflecting increasing randomness and information content as the brain transitions from structured early sleep to more complex wakefulness. c). shows the heatmap of p-values from paired t-tests comparing Statistical Complexity across the sleep stages. d). displays the corresponding p-values for Lempel-Ziv Complexity. Significant differences () are indicated by darker shades, revealing clear distinctions between most stages, particularly between Early Night Sleep and other stages. Non-significant differences (), highlighted in yellow.

Figure 16.

Mean complexity measures with standard error across the sleep stages. a). displays the Grand Mean Statistical Complexity b).) shows the Grand Mean Lempel-Ziv Complexity for the same sleep stages. Statistical Complexity increases from eNREM to WR, with the most significant changes observed between early sleep and wakefulness. Lempel-Ziv Complexity also rises from eNREM to WR, reflecting increasing randomness and information content as the brain transitions from structured early sleep to more complex wakefulness. c). shows the heatmap of p-values from paired t-tests comparing Statistical Complexity across the sleep stages. d). displays the corresponding p-values for Lempel-Ziv Complexity. Significant differences () are indicated by darker shades, revealing clear distinctions between most stages, particularly between Early Night Sleep and other stages. Non-significant differences (), highlighted in yellow.

Figure 17.

Correlation Between SC and LZc Across Different Sleep States. Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicate varying relationships between SC and LZc in these states, highlighting that SC and LZc capture distinct aspects of neural complexity, with stronger correlations observed in certain states, reflecting differences in the underlying dynamics of the sleep states.

Figure 17.

Correlation Between SC and LZc Across Different Sleep States. Pearson’s correlation coefficients indicate varying relationships between SC and LZc in these states, highlighting that SC and LZc capture distinct aspects of neural complexity, with stronger correlations observed in certain states, reflecting differences in the underlying dynamics of the sleep states.

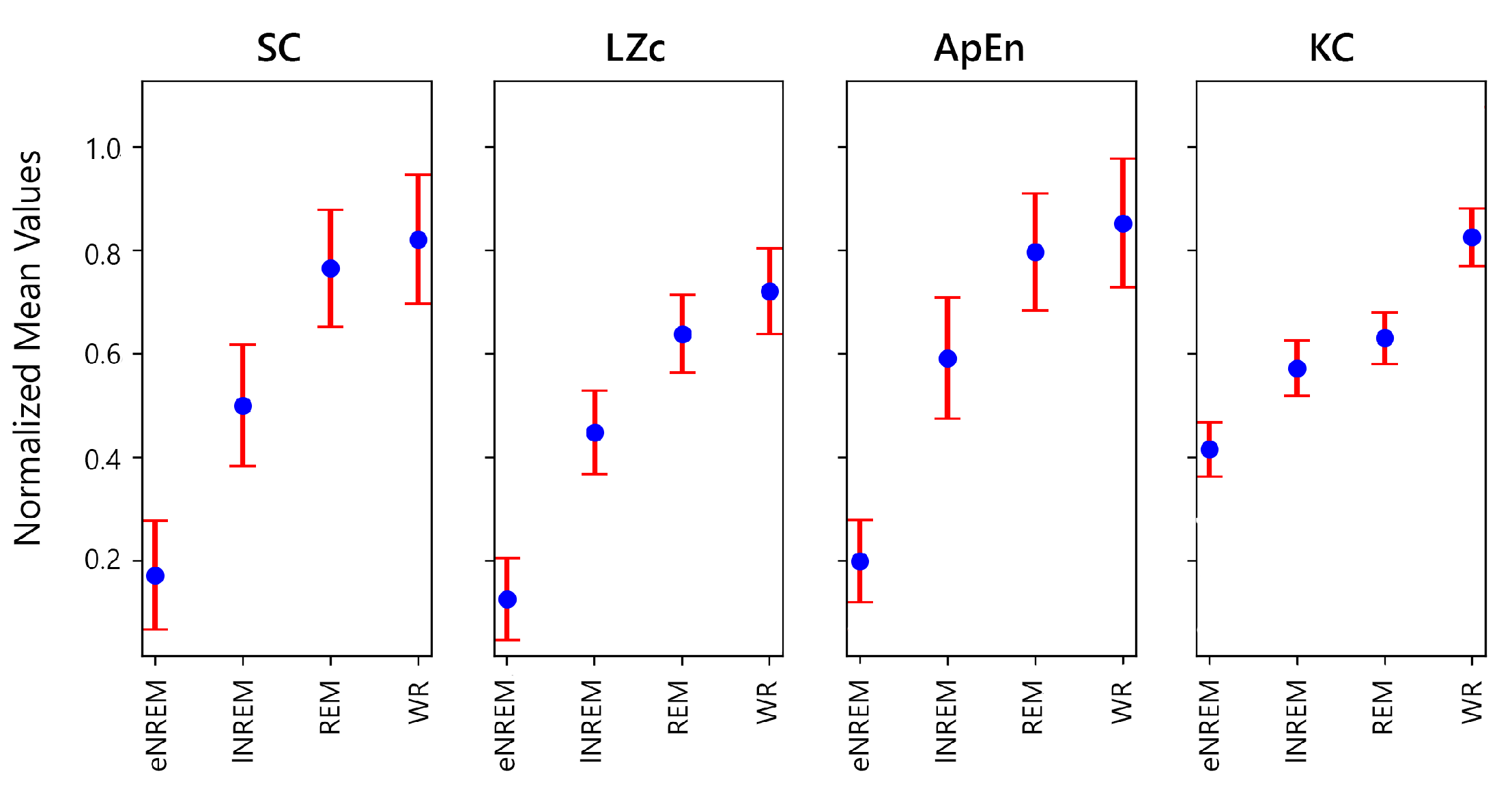

Figure 18.

Comparison of Mean Complexity Measures with Standard Error Across Sleep Stages for Statistical complexity (SC), Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc), Approximate entropy (ApEn) and Kolmogorov complexity (KC). The error bars represent the standard error of the mean, providing a clear visual summary of how complexity measures vary across states. For all four measures, there is a general increase from eNREM state to the WR state, suggesting a trend towards higher complexity as the brain becomes more active.

Figure 18.

Comparison of Mean Complexity Measures with Standard Error Across Sleep Stages for Statistical complexity (SC), Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZc), Approximate entropy (ApEn) and Kolmogorov complexity (KC). The error bars represent the standard error of the mean, providing a clear visual summary of how complexity measures vary across states. For all four measures, there is a general increase from eNREM state to the WR state, suggesting a trend towards higher complexity as the brain becomes more active.

Table 1.

SC Cohen’s d results (, )

Table 1.

SC Cohen’s d results (, )

| |

lNREM |

REM |

WR |

| eNREM |

1.24 |

1.99 |

2.03 |

| lNREM |

|

0.69 |

0.80 |

| REM |

|

|

0.14 |

Table 2.

LZc Cohen’s d results

Table 2.

LZc Cohen’s d results

| |

lNREM |

REM |

WR |

| eNREM |

1.21 |

2.00 |

2.20 |

| lNREM |

|

0.73 |

0.99 |

| REM |

|

|

0.31 |

Table 3.

Results of Simonsohn’s Two-Lines Test of a U-Shaped Relationship

Table 3.

Results of Simonsohn’s Two-Lines Test of a U-Shaped Relationship

| |

Regression Line 1 |

|

Regression Line 2 |

| SC |

|

|

|

| LZc |

|

|

|

Table 4.

Performance of Complexity Measures in distinguishing Sleep States

Table 4.

Performance of Complexity Measures in distinguishing Sleep States

| Complexity |

E vs. L |

E vs. R |

E vs. W |

L vs. R |

L vs. W |

R vs. W |

| SC |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| LZc |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| KC |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| ApEn |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |