Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chronic Infection of F. nucleatum, Colonized in Mice Gingival Tissue

2.2. Alveolar Bone Resorption and Bacterial Genomic DNA in the Distal Organs

2.3. NanoString Analysis of miRNA in F. nucleatum-Infected Mandibles

2.4. Identification of Differentially Expressed (DE) miRNAs

| miRs /(FC) |

p-value | Reported Functions | Target genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-361 -5p (1.3) | 0.0311 | Downregulated in the 13 types of cancer, including CRC [44]. Upregulated in-stable coronary heart disease, acute coronary heart syndrome [45]. | 16 (E.g., Ctbp2, Tfam, Nol7) |

| miR-26a-5p -5p (1.23) | 0.0008 | Downregulated in the gingiva of periodontitis patients [46]. Associated with cardiovascular diseases [47]. | 426 (e.g., Kpna2, Nus1, Rgs17) |

| miR193a -3p (1.21) | 0.0150 | Downregulated in plasma and salivary exosomes of Chronic periodontitis patients [48]. Downregulated in the P. gingivalis-LPS-treated human periodontal ligament cells [49]. Upregulated miR-193 improved cardiac function, and attenuated myocardial injury, inflammation, and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in septic mice [50]. Dysregulated in Pancreatic cancer [51]; colorectal cancer [52]; endometrial cancer [53]. A novel biomarker for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis [54]. Downregulated in the microbiota-mediated ulcerative colitis [55]. | 8(e.g., Gla, Ifngr2, Metap2) |

| miR-126 -5p (1.2) | 0.0308 | Upregulated miR in T. denticola-induced periodontitis [37]. Preventing alveolar bone resorption in diabetic periodontitis [56]. Upregulated miR in the gingiva of PD patients [57]. Associated in colorectal cancer [58]; promoting chemoresistance of ovarian cancer cells [59]. Upregulated in coronary artery ectasia patients [60]. Upregulated in thoracic aorta aneurism patients [61]. Reported as a molecular target for myocardial infarction treatment [62]. Reported as a poultry meat quality and food safety marker miRNA [63]. | 55 (e.g., Gfpt1, H2-D1, Il10rb, Kras) |

|

miR-324 -5p (1.18) |

0.0164 | Downregulated in the gingival tissue of periodontitis patients [64]. Reported as a therapeutic-miR in cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, brain tumors, and hepatocellular carcinoma [65]. Human cases with heart failure have reported AUC for miR-324-5p and are considered as a diagnostic miR [66]. Downregulated in osteoporosis patients [67]. | 12 (E.g., Zfp295, Zscan12, Kcnk6) |

|

miR-24-3p (1.17) |

0.0160 | Downregulated in the unstimulated saliva of chronic periodontitis patients [48]. Reported as a defensive miR against periodontal inflammation [68]. A diagnostic marker for multiple cancers [69]. | 375 (e.g., Oxt, Chrna1, Birc5) |

| miR-99b -5p (1.14) | 0.0120 | Downregulated in the gingiva of periodontitis patients [64]. Upregulated in the P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis [36]. Downregulated in the saliva of chronic periodontitis patients [48]. Upregulated in M. tuberculosis-infected murine dendritic cells [70]. Novel chemosensitizing miRNAs in high-risk neuroblastoma [71,72]. Associated in the cancer conditions to ovaries [73]; prostate [74]; colorectal [75]; gastric [76]; liver [77]; and lungs [78]. | 4 (E.g., Comp, Grik3, Slc35d2) |

| miRs /FC |

p-value | Reported Functions | Target genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| let-7a-5p (1.28) |

0.0011 | Downregulated in T. denticola-induced periodontitis [37]. Downregulated in the saliva of patients with aggressive periodontitis [79]. Upregulated in gingival tissue of chronic periodontitis patients [80]. IL-13 a cytokine essential for allergic lung diseases is regulated by mmu-let-7a-5p [81]. Downregulated in bronchial biopsy of severe Asthma patients [82]. | 28 (e.g., Lin28a, IL6, Hoxa9) |

| miR-127 -3p (1.28) | 0.0217 | Upregulated in T. forsythia-induced rodent periodontitis models [38]. Upregulated in the inflamed primary human gingival fibroblasts [83]. Upregulated in the human advanced carotid atheroma [84]. May play an important role in acute myocardial injury [85]. Tumor suppressor miRNA in triple-negative breast cancer cells [86]. | 10 (E.g., Rtl1, Gpi1, Ghdc) |

| miR-361 -5p (1.19) | 0.0357 | Reported in 8 weeks analysis study | |

|

miR-345 -5p (1.16) |

0.0034 | Reliable biomarker in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma [87]. Acting as an anti-inflammatory miRNA in mice with allergic rhinitis [88]. Reported as a protective miRNA during gestational diabetes mellitus subjects [89]. | 10 (e.g., Ccdc127, Eaf1, Atic) |

| let-7f-5p (1.16) |

0.0298 | Upregulated in human periodontitis gingival tissue [57]. Potential biomarker for abdominal aortic aneurysm [90]. Involvement in the pathogenesis of SLE-lupus nephritis [91]. | 16 (e.g., Atp2b2, Ifnar1, Nf2). |

| miR-99b -5p (1.15) | 0.0299 | Reported in 8 weeks analysis study | |

| miR-218 -5p (1.15) | 0.0333 | Upregulated in the T. forsythia-induced rodent periodontitis models [38]. Downregulated in the gingival fibroblasts and is essential for myofibroblast differentiation [92]. Upregulated in the inflamed gingiva [93]. Reduced expression was observed in the atherosclerosis cohort and considered a clinical marker for atherosclerosis [94]. Downregulated in smokers without airflow limitation and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [95]. | 20 (e.g., Epg5, Prdm1, Bsn, Eno2) |

2.5. DE miRNAs and Functional Pathway Analysis

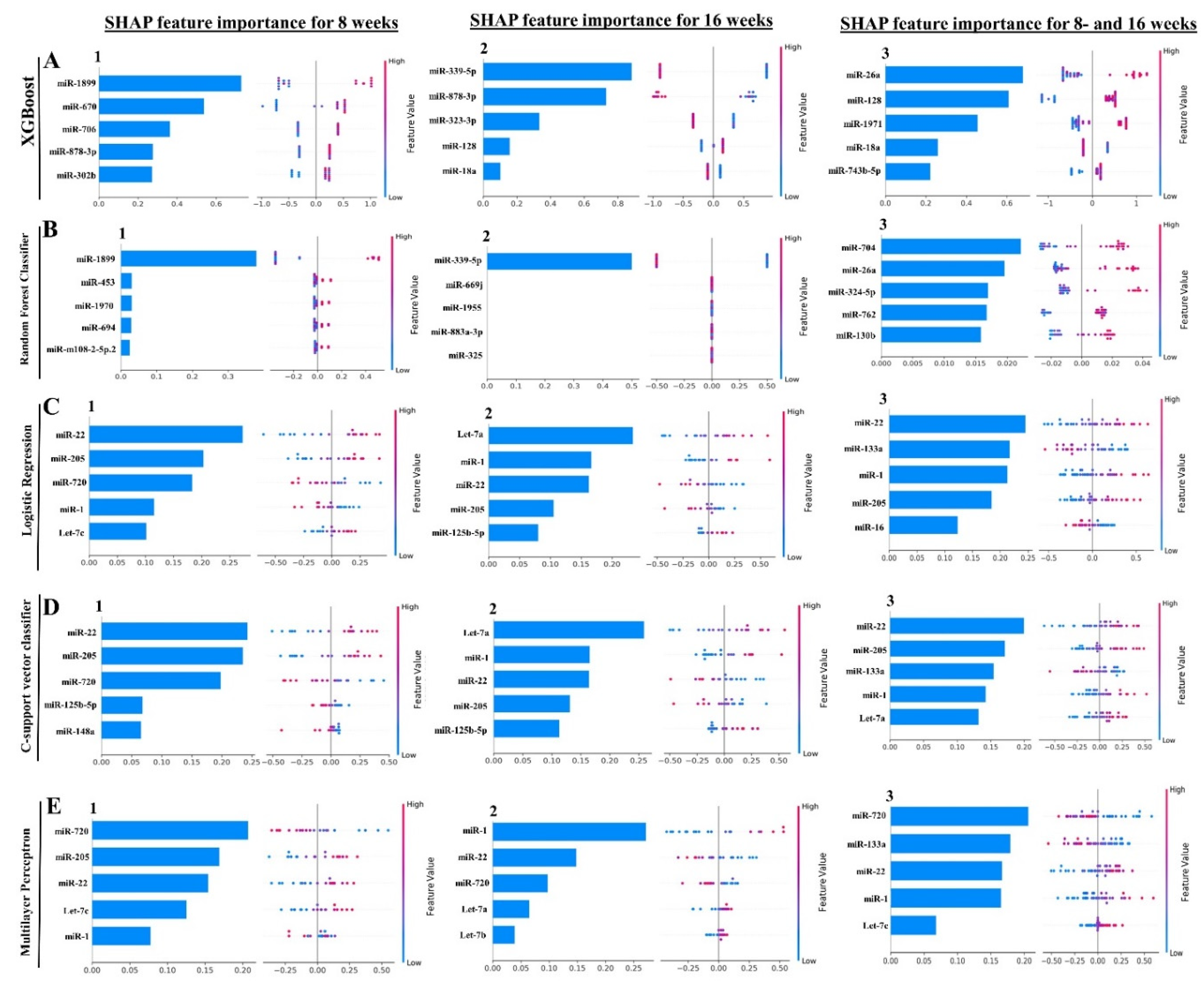

2.6. Machine Learning Analysis of NanoString miRNA Copies

| miRNA (Feature Rank) |

ML Model | MIMAT# | Target Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Weeks Analysis | |||

| mirR-22 (1) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000531 | Upregulated in periodontal disease and obesity [97]. |

| miR-205 (2) | LR, SVC, MLP | MIMAT0000238 | Downregulated in chronic periodontitis patients [98,99]. |

| miR-720 (3) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0003484 | Novel miRNA regulating the differentiation of Dental pulp cells [100]. |

| miR-1899 (1) | XGB, RFC | MIMAT0007869 | |

| 16 Weeks Analysis | |||

| let-7a-5p (1) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000521 | Downregulated in aggressive periodontitis patients [79]. Promotes the osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [101]. |

| miR-1 (2) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000123 | Noninvasive biomarker for breast cancer [102]. Upregulated in patients with myocardial infarction [103]. |

| miR-22 (3) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000531 | Shown in the 8 weeks analysis |

| miR-205 (4) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000238 | Shown in the 8 weeks analysis |

| miR-125b-5p (5) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000135 | Associated with osteogenic differentiation [104]. Overlapping miRNA between periodontitis and Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [105]. |

| miR-339-5p (1) | XGB, RFC | MIMAT0000584 | Most predictive periodontal miRNA in the T. forsythia-induced mice periodontitis [38]. |

| 8- and 16 Weeks Analysis | |||

| miR-22 (1) | LR, SVC | MIMAT0000531 | Shown in the 8 weeks analysis |

| miR-133a (2) | LR, MLP | MIMAT0000145 | Upregulated in the T. denticola-induced mice periodontitis [37]. |

| miR-1 (4) | SVC, MLP | MIMAT0000123 | Shown in the 16 weeks analysis |

| miRNA Feature Rank | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | miRNA | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 weeks | miR-22 | LR, SVC | MLP | |||

| miR-205 | LR, SVC, MLP | |||||

| miR-720 | MLP | LR, SVC | ||||

| miR-1 | LR | MLP | ||||

| let-7c | MLP | LR | ||||

| miR-125b-5p | SVC | |||||

| miR-148a | SVC | |||||

| miR-1899 | XGB, RFC | |||||

| miR-670 | XGB | |||||

| miR-706 | XGB | |||||

| miR-878-3p | XGB | |||||

| miR-302b | XGB | |||||

| miR-453 | RFC | |||||

| miR-1970 | RFC | |||||

| miR-694 | RFC | |||||

| miR-m108-2-5p.2 | RFC | |||||

| 16 weeks | let-7a-5p | LR, SVC | MLP | |||

| miR-1 | MLP | LR, SVC | ||||

| miR-22 | MLP | LR, SVC | ||||

| miR-205 | LR, SVC | |||||

| miR-125b-5p | LR, SVC | |||||

| miR-720 | MLP | |||||

| let-7b | MLP | |||||

| miR-339-5p | XGB, RFC | |||||

| miR-878-3p | XGB | |||||

| miR-323-3p | XGB | |||||

| miR-128 | XGB | |||||

| miR-18a | XGB | |||||

| 8 and 16 weeks |

miR-22 | LR, SVC | MLP | |||

| miR-133a | LR, MLP | SVC | ||||

| miR-1 | LR | SVC, MLP | ||||

| miR-205 | SVC | LR | ||||

| miR-16 | LR | |||||

| miR-720 | MLP | |||||

| let-7a-5p | SVC | |||||

| let-7c | MLP | |||||

| miR-26a-5p | XGB | RFC | ||||

| miR-128 | XGB | |||||

| miR-1971 | XGB | |||||

| miR-18a | XGB | |||||

| miR-743b-5p | XGB | |||||

| miR-704 | RFC | |||||

| miR-324-5p | RFC | |||||

| miR-762 | RFC | |||||

| miR-130b | RFC | |||||

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Models, Ethical Statement, and Grouping

4.2. Bacterial Strain, Culture, and Mice-Oral Administration

4.3. DNA Isolation and Molecular Detection of Bacteria Genome

4.4. Measurement of Alveolar Bone Resorption (ABR)

4.6. Bioinformatics Analysis

4.7. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

4.8. Multiple Machine Learning (ML) Model Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krieger, M.; AbdelRahman, Y.M.; Choi, D.; Palmer, E.A.; Yoo, A.; McGuire, S.; Kreth, J.; Merritt, J. Stratification of Fusobacterium nucleatum by local health status in the oral cavity defines its subspecies disease association. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolstad, A.I.; Jensen, H.B.; Bakken, V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Microbiol Rev 1996, 9, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Cugini, M.A.; Smith, C.; Kent, R.L., Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol 1998, 25, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol 2015, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolenbrander, P.E.; London, J. Adhere today, here tomorrow: oral bacterial adherence. J Bacteriol 1993, 175, 3247–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolenbrander, P.E. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu Rev Microbiol 2000, 54, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersole, J.L.; Feuille, F.; Kesavalu, L.; Holt, S.C. Host modulation of tissue destruction caused by periodontopathogens: effects on a mixed microbial infection composed of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Microb Pathog 1997, 23, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settem, R.P.; El-Hassan, A.T.; Honma, K.; Stafford, G.P.; Sharma, A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Tannerella forsythia induce synergistic alveolar bone loss in a mouse periodontitis model. Infect Immun 2012, 80, 2436–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velsko, I.M.; Chukkapalli, S.S.; Rivera-Kweh, M.F.; Chen, H.; Zheng, D.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Gangula, P.R.; Lucas, A.R.; Kesavalu, L. Fusobacterium nucleatum Alters Atherosclerosis Risk Factors and Enhances Inflammatory Markers with an Atheroprotective Immune Response in ApoE(null) Mice. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0129795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W.; Ikegami, A.; Rajanna, C.; Kawsar, H.I.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.; Sojar, H.T.; Genco, R.J.; Kuramitsu, H.K.; Deng, C.X. Identification and characterization of a novel adhesin unique to oral fusobacteria. J Bacteriol 2005, 187, 5330–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yamada, M.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.G.; Han, Y.W. FadA from Fusobacterium nucleatum utilizes both secreted and nonsecreted forms for functional oligomerization for attachment and invasion of host cells. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 25000–25009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/beta-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Baik, J.E.; Lagana, S.M.; Han, R.P.; Raab, W.J.; Sahoo, D.; Dalerba, P.; Wang, T.C.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer by inducing Wnt/beta-catenin modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Rep 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Q.; Gao, Q.; Mehrazarin, S.; Tangwanichgapong, K.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Robinson, S.; Liu, Z.; Zangiabadi, A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum secretes amyloid-like FadA to enhance pathogenicity. EMBO Rep 2021, 22, e52891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, J.E.; Li, L.; Shah, M.A.; Freedberg, D.E.; Jin, Z.; Wang, T.C.; Han, Y.W. Circulating IgA Antibodies Against Fusobacterium nucleatum Amyloid Adhesin FadA are a Potential Biomarker for Colorectal Neoplasia. Cancer Res Commun 2022, 2, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W.; Shi, W.; Huang, G.T.; Kinder Haake, S.; Park, N.H.; Kuramitsu, H.; Genco, R.J. Interactions between periodontal bacteria and human oral epithelial cells: Fusobacterium nucleatum adheres to and invades epithelial cells. Infection and immunity 2000, 68, 3140–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, F.Q.; Johnson, L.; Roberts, J.; Hung, S.C.; Lee, J.; Atanasova, K.R.; Huang, P.R.; Yilmaz, O.; Ojcius, D.M. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection of gingival epithelial cells leads to NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent secretion of IL-1beta and the danger signals ASC and HMGB1. Cell Microbiol 2016, 18, 970–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Jaaback, K.; Boulton, A.; Wong-Brown, M.; Raymond, S.; Dutta, P.; Bowden, N.A.; Ghosh, A. Fusobacterium nucleatum: An Overview of Evidence, Demi-Decadal Trends, and Its Role in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Various Gynecological Diseases, including Cancers. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Qiu, H.; Hong, K.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, B. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes proliferation in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma via AHR/CYP1A1 signalling. FEBS J 2023, 290, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehr, K.; Nikitina, D.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Steponaitiene, R.; Thon, C.; Skieceviciene, J.; Schanze, D.; Zenker, M.; Malfertheiner, P.; Kupcinskas, J.; et al. Microbial composition of tumorous and adjacent gastric tissue is associated with prognosis of gastric cancer. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Ikenaga, N.; Nakata, K.; Luo, H.; Zhong, P.; Date, S.; Oyama, K.; Higashijima, N.; Kubo, A.; Iwamoto, C.; et al. Intratumor Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes the progression of pancreatic cancer via the CXCL1-CXCR2 axis. Cancer Sci 2023, 114, 3666–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Cheng, Z.; Yin, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, F.; Jin, Y.; Yang, G. Airway Fusobacterium is Associated with Poor Response to Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2022, 15, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlvanna, E.; Linden, G.J.; Craig, S.G.; Lundy, F.T.; James, J.A. Fusobacterium nucleatum and oral cancer: a critical review. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Romano, F.; Aimetti, M.; Romandini, M. The Gum-Gut Axis: Periodontitis and the Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.F.; Shu, R.; Jiang, S.Y.; Liu, D.L.; Zhang, X.L. Comparison of microRNA profiles of human periodontal diseased and healthy gingival tissues. Int J Oral Sci 2011, 3, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.L.; Sullivan, J.C. Circulating cell-free micro-RNA as biomarkers: from myocardial infarction to hypertension. Clin Sci (Lond) 2022, 136, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.C.; Farh, K.K.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 2009, 19, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, A.; Min, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, S.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, S.; et al. MiR-1298-5p level downregulation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits autophagy and promotes gastric cancer development by targeting MAP2K6. Cell Signal 2022, 93, 110286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, J.; Ke, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Liao, Y.; Liang, F.; Mei, S.; Li, M.; et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells associated with syphilis. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davuluri, K.S.; Chauhan, D.S. microRNAs associated with the pathogenesis and their role in regulating various signaling pathways during. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1009901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, C.; Cruz, A.R.; Rodrigues Lopes, I.; Maudet, C.; Sunkavalli, U.; Silva, R.J.; Sharan, M.; Lisowski, C.; Zaldívar-López, S.; Garrido, J.J.; et al. Functional screenings reveal different requirements for host microRNAs in Salmonella and Shigella infection. Nat Microbiol 2020, 5, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, B.R.; Zhang, M.; Sonntag, W.E.; Drevets, D.A. Neuroinvasive Listeria monocytogenes infection triggers accumulation of brain CD8. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, T.; Tamizu, E.; Uno, S.; Uwamino, Y.; Fujiwara, H.; Nishio, K.; Nakano, Y.; Shiono, H.; Namkoong, H.; Hoshino, Y.; et al. hsa-miR-346 is a potential serum biomarker of Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease activity. J Infect Chemother 2017, 23, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindraja, C.; Vekariya, K.M.; Botello-Escalante, R.; Rahaman, S.O.; Chan, E.K.L.; Kesavalu, L. Specific microRNA Signature Kinetics in Porphyromonas gingivalis-Induced Periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindraja, C.; Jeepipalli, S.; Vekariya, K.M.; Botello-Escalante, R.; Chan, E.K.L.; Kesavalu, L. Oral Spirochete Treponema denticola Intraoral Infection Reveals Unique miR-133a, miR-486, miR-126-3p, miR-126-5p miRNA Expression Kinetics during Periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindraja, C.; Jeepipalli, S.; Duncan, W.; Vekariya, K.M.; Bahadekar, S.; Chan, E.K.L.; Kesavalu, L. Unique miRomics Expression Profiles in Tannerella forsythia-Infected Mandibles during Periodontitis Using Machine Learning. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindraja, C.; Kashef, M.R.; Vekariya, K.M.; Ghanta, R.K.; Karanth, S.; Chan, E.K.L.; Kesavalu, L. Global Noncoding microRNA Profiling in Mice Infected with Partial Human Mouth Microbes (PAHMM) Using an Ecological Time-Sequential Polybacterial Periodontal Infection (ETSPPI) Model Reveals Sex-Specific Differential microRNA Expression. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzeldemir-Akcakanat, E.; Sunnetci-Akkoyunlu, D.; Balta-Uysal, V.M.; Ozer, T.; Isik, E.B.; Cine, N. Differentially expressed miRNAs associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 28, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahid, M.A.; Rivera, M.; Lucas, A.; Chan, E.K.; Kesavalu, L. Polymicrobial infection with periodontal pathogens specifically enhances microRNA miR-146a in ApoE-/- mice during experimental periodontal disease. Infection and immunity 2011, 79, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravindraja, C.; Jeepipalli, S.; Duncan, W.D.; Vekariya, K.M.; Rahaman, S.O.; Chan, E.K.L.; Kesavalu, L. Streptococcus gordonii Supragingival Bacterium Oral Infection-Induced Periodontitis and Robust miRNA Expression Kinetics. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usui, M.; Onizuka, S.; Sato, T.; Kokabu, S.; Ariyoshi, W.; Nakashima, K. Mechanism of alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis - Periodontal bacteria and inflammation. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2021, 57, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Dong, P.; Xiong, Y.; Yue, J.; Ihira, K.; Konno, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Todo, Y.; Watari, H. MicroRNA-361: A Multifaceted Player Regulating Tumor Aggressiveness and Tumor Microenvironment Formation. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chang, G.; Cao, L.; Ding, G. Dysregulation of serum miR-361-5p serves as a biomarker to predict disease onset and short-term prognosis in acute coronary syndrome patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2021, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uttamani, J.R.; Naqvi, A.R.; Estepa, A.M.V.; Kulkarni, V.; Brambila, M.F.; Martinez, G.; Chapa, G.; Wu, C.D.; Li, W.; Rivas-Tumanyan, S.; et al. Downregulation of miRNA-26 in chronic periodontitis interferes with innate immune responses and cell migration by targeting phospholipase C beta 1. J Clin Periodontol 2023, 50, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildeberger, L.; Bueto, J.; Wilmes, V.; Scheiper-Welling, S.; Niess, C.; Gradhand, E.; Verhoff, M.A.; Kauferstein, S. Suitable biomarkers for post-mortem differentiation of cardiac death causes: Quantitative analysis of miR-1, miR-133a and miR-26a in heart tissue and whole blood. Forensic Sci Int Genet 2023, 65, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik Mohamed Kamal, N.N.S.; Awang, R.A.R.; Mohamad, S.; Shahidan, W.N.S. Plasma- and Saliva Exosome Profile Reveals a Distinct MicroRNA Signature in Chronic Periodontitis. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 587381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, A.; Zhao, S.; Wan, L.; Liu, T.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Liao, Z.; Fang, H. MicroRNA expression profile of human periodontal ligament cells under the influence of Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS. J Cell Mol Med 2016, 20, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Alexan, B.; Dennis, D.; Bettina, C.; Christoph, L.I.M.; Tang, Y. microRNA-193-3p attenuates myocardial injury of mice with sepsis via STAT3/HMGB1 axis. J Transl Med 2021, 19, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolimetti, G.; Pelisenco, I.A.; Eusebi, L.H.; Ricci, C.; Cavina, B.; Kurelac, I.; Verri, T.; Calcagnile, M.; Alifano, P.; Salvi, A.; et al. Dysregulation of a Subset of Circulating and Vesicle-Associated miRNA in Pancreatic Cancer. Noncoding RNA 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanram, S.; Klaewkla, N.; Pinyosri, P. Downregulation of Serum miR-133b and miR-206 Associate with Clinical Outcomes of Progression as Monitoring Biomarkers for Metastasis Colorectal Cancer Patients. Microrna 2024, 13, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dai, L.; Liu, J.; Ge, J. Expression of miR-128-3p, miR-193a-3p and miR-193a-5p in endometrial cancer tissues and their relationship with clinicopathological parameters. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2022, 68, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Liu, Z.; Sun, G. Diagnostic value of miR-193a-3p in Alzheimer's disease and miR-193a-3p attenuates amyloid-beta induced neurotoxicity by targeting PTEN. Exp Gerontol 2020, 130, 110814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, Q.; Shi, L.; Liang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Pang, W.; Hou, D.; Wang, C.; et al. MicroRNA-193a-3p Reduces Intestinal Inflammation in Response to Microbiota via Down-regulation of Colonic PepT1. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 16099–16115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Lai, W.; Song, L.; Deng, J.; Li, C.; Jiang, S. MicroRNA-126 regulates macrophage polarization to prevent the resorption of alveolar bone in diabetic periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol 2023, 150, 105686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragaite-Staponkiene, B.; Rovas, A.; Puriene, A.; Snipaitiene, K.; Punceviciene, E.; Rimkevicius, A.; Butrimiene, I.; Jarmalaite, S. Gingival Tissue MiRNA Expression Profiling and an Analysis of Periodontitis-Specific Circulating MiRNAs. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hu, S.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Teng, D.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Du, X. H3K27ac-activated LncRNA NUTM2A-AS1 Facilitates the Progression of Colorectal Cancer Cells via MicroRNA-126-5p/FAM3C Axis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Lv, X.; Liu, D.; Guo, H.; Yao, G.; Wang, L.; Liang, X.; Yang, Y. METTL3-mediated maturation of miR-126-5p promotes ovarian cancer progression via PTEN-mediated PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Cancer Gene Ther 2021, 28, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalim, Z.; Onrat, S.T.; Dural, I.E.; Onrat, E. Could Aneurysm and Atherosclerosis-Associated MicroRNAs (miR 24-1-5p, miR 34a-5p, miR 126-5p, miR 143-5p, miR 145-5p) Also Be Associated with Coronary Artery Ectasia? Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2023, 27, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekedi, A.; Rozhkov, A.N.; Shchekochikhin, D.Y.; Novikova, N.A.; Kopylov, P.Y.; Bestavashvili, A.A.; Ivanova, T.V.; Zhelankin, A.V.; Generozov, E.V.; Konanov, D.N.; et al. Evaluation of microRNA Expression Features in Patients with Various Types of Arterial Damage: Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Coronary Atherosclerosis. J Pers Med 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, H. MicroRNA-126-5p Facilitates Hypoxia-Induced Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury via HIPK2. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2022, 52, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baraldo, N.; Buzzoni, L.; Pasti, L.; Cavazzini, A.; Marchetti, N.; Mancia, A. miRNAs as Biomolecular Markers for Food Safety, Quality, and Traceability in Poultry Meat-A Preliminary Study. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baru, O.; Raduly, L.; Bica, C.; Chiroi, P.; Budisan, L.; Mehterov, N.; Ciocan, C.; Pop, L.A.; Buduru, S.; Braicu, C.; et al. Identification of a miRNA Panel with a Potential Determinant Role in Patients Suffering from Periodontitis. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 45, 2248–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadkhoda, S.; Hussen, B.M.; Eslami, S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. A review on the role of miRNA-324 in various diseases. Front Genet 2022, 13, 950162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.L.; Cameron, V.A.; Troughton, R.W.; Frampton, C.M.; Ellmers, L.J.; Richards, A.M. Circulating microRNAs as candidate markers to distinguish heart failure in breathless patients. Eur J Heart Fail 2013, 15, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, H.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Xia, J.; Yin, X. Identification of differentially expressed microRNAs in the bone marrow of osteoporosis patients. Am J Transl Res 2019, 11, 2940–2954. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, A.R.; Fordham, J.B.; Nares, S. miR-24, miR-30b, and miR-142-3p regulate phagocytosis in myeloid inflammatory cells. J Immunol 2015, 194, 1916–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Ding, K.; Zhang, W.; Hou, J. MiR-24-3p as a prognostic indicator for multiple cancers: from a meta-analysis view. Biosci Rep 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Kaul, V.; Mehra, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Tousif, S.; Dwivedi, V.P.; Suar, M.; Van Kaer, L.; Bishai, W.R.; Das, G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis controls microRNA-99b (miR-99b) expression in infected murine dendritic cells to modulate host immunity. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 5056–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, H.; Yang, J.; Dodson, E.; Nikolic, I.; Kamili, A.; Wheatley, M.; Deng, N.; Alexandrou, S.; Davis, T.P.; Kavallaris, M.; et al. miR-99b-5p, miR-380-3p, and miR-485-3p are novel chemosensitizing miRNAs in high-risk neuroblastoma. Mol Ther 2024, 32, 2031–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holliday, H.; Yang, J.; Dodson, E.; Nikolic, I.; Kamili, A.; Wheatley, M.; Deng, N.; Alexandrou, S.; Davis, T.P.; Kavallaris, M.; et al. miR-99b-5p, miR-380-3p, and miR-485-3p are novel chemosensitizing miRNAs in high-risk neuroblastoma. Mol Ther 2022, 30, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Wang, B.D. Combination of miR-99b-5p and Enzalutamide or Abiraterone Synergizes the Suppression of EMT-Mediated Metastasis in Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Gujrati, H.; Wang, B.D. Tumor suppressive miR-99b-5p as an epigenomic regulator mediating mTOR/AR/SMARCD1 signaling axis in aggressive prostate cancer. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1184186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Ye, M.; Wang, C.; Pan, J.; Wei, W.; Li, J.; et al. Exosomal miR-99b-5p Secreted from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Can Retard the Progression of Colorectal Cancer by Targeting FGFR3. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2023, 19, 2901–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Hou, N.; Guo, Q.; Song, T.; et al. Author Correction: MiR-99b-5p and miR-203a-3p Function as Tumor Suppressors by Targeting IGF-1R in Gastric Cancer. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Do, D.N.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen-Thanh, T.; Nguyen, H.T. Immune-related biomarkers shared by inflammatory bowel disease and liver cancer. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0267358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Luo, M.; Dai, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J. Serum exosomal microRNAs as predictive markers for EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Lab Anal 2021, 35, e23743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.H.; Lee, E.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, W.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.H. Differential expression of microRNAs in the saliva of patients with aggressive periodontitis: a pilot study of potential biomarkers for aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontal Implant Sci 2020, 50, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, P.; Koshy, T.; Lavu, V.; Ranga Rao, S.; Ramasamy, S.; Hariharan, S.; Venkatesan, V. Differential expression of microRNAs let-7a, miR-125b, miR-100, and miR-21 and interaction with NF-kB pathway genes in periodontitis pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 5877–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikepahad, S.; Knight, J.M.; Naghavi, A.O.; Oplt, T.; Creighton, C.J.; Shaw, C.; Benham, A.L.; Kim, J.; Soibam, B.; Harris, R.A.; et al. Proinflammatory role for let-7 microRNAS in experimental asthma. The Journal of biological chemistry 2010, 285, 30139–30149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijavec, M.; Korosec, P.; Zavbi, M.; Kern, I.; Malovrh, M.M. Let-7a is differentially expressed in bronchial biopsies of patients with severe asthma. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, Y.; Matsui, S.; Kato, A.; Zhou, L.; Nakayama, Y.; Takai, H. MicroRNA expression in inflamed and noninflamed gingival tissues from Japanese patients. J Oral Sci 2014, 56, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Hu, W.; Zou, S.; Ren, H.; Zuo, Y.; Qu, L. MiR-127-3p enhances macrophagic proliferation via disturbing fatty acid profiles and oxidative phosphorylation in atherosclerosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2024, 193, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Xia, Y.; Chen, H.; Yin, L.; Hu, K. Screening for Regulatory Network of miRNA-Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Prognosis-Related mRNA in Acute Myocardial Infarction: An in silico and Validation Study. Int J Gen Med 2022, 15, 1715–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh-Garcia, M.; Simion, C.; Ho, P.Y.; Batra, N.; Berg, A.L.; Carraway, K.L.; Yu, A.; Sweeney, C. A Novel Bioengineered miR-127 Prodrug Suppresses the Growth and Metastatic Potential of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, B.; Horvath, J.; Tar, I.; Kiss, C.; Marton, I.J. Salivary miR-31-5p, miR-345-3p, and miR-424-3p Are Reliable Biomarkers in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Han, M.; Jiang, L.; Liang, D.; Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, N. MicroRNA-345-5p acts as an anti-inflammatory regulator in experimental allergic rhinitis via the TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 86, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhuang, J. miR-345-3p serves a protective role during gestational diabetes mellitus by targeting BAK1. Exp Ther Med 2021, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, R.; Boytard, L.; Blervaque, R.; Chwastyniak, M.; Hot, D.; Vanhoutte, J.; Lamblin, N.; Amouyel, P.; Pinet, F. Let-7f: A New Potential Circulating Biomarker Identified by miRNA Profiling of Cells Isolated from Human Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Tsao, B.P.; Feng, X.; Sun, L. Reduced Let-7f in Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Triggers Treg/Th17 Imbalance in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Carter, D.E.; Leask, A. miR-218 regulates focal adhesion kinase-dependent TGFbeta signaling in fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell 2014, 25, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Na, H.S.; Jeong, S.Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Park, H.R.; Chung, J. Comparison of inflammatory microRNA expression in healthy and periodontitis tissues. Biocell 2011, 35, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wei, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, H. MicroRNA-218-5p regulates inflammation response via targeting TLR4 in atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023, 23, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conickx, G.; Mestdagh, P.; Avila Cobos, F.; Verhamme, F.M.; Maes, T.; Vanaudenaerde, B.M.; Seys, L.J.; Lahousse, L.; Kim, R.Y.; Hsu, A.C.; et al. MicroRNA Profiling Reveals a Role for MicroRNA-218-5p in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017, 195, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Peng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X. The Role of CREBBP/EP300 and Its Therapeutic Implications in Hematological Malignancies. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, R.; Nares, S.; Zhang, S.; Barros, S.P.; Offenbacher, S. MicroRNA modulation in obesity and periodontitis. J Dent Res 2012, 91, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wen, Y. miR-205 and HMGB1 expressions in chronic periodontitis patients and their associations with the inflammatory factors. Am J Transl Res 2021, 13, 9224–9232. [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin-Wasmer, C.; Guarnieri, P.; Celenti, R.; Demmer, R.T.; Kebschull, M.; Papapanou, P.N. MicroRNAs and their target genes in gingival tissues. J Dent Res 2012, 91, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, E.S.; Ono, M.; Eguchi, T.; Kubota, S.; Pham, H.T.; Sonoyama, W.; Tajima, S.; Takigawa, M.; Calderwood, S.K.; Kuboki, T. miRNA-720 controls stem cell phenotype, proliferation and differentiation of human dental pulp cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gao, J.; Chen, M.; Sun, Y.; Qiao, X.; Mao, H.; Guo, L.; Yu, Y.; Yang, D. Let-7a promotes periodontal bone regeneration of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell aggregates via the Fas/FasL-autophagy pathway. J Cell Mol Med 2023, 27, 4056–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Lin, Y.; Sheng, X.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Y.; Yin, W.; Zhou, L.; Lu, J. Serum miRNA-1 may serve as a promising noninvasive biomarker for predicting treatment response in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, F.; Seyed Mohammadzad, M.H. Up-Regulation of Cell-Free MicroRNA-1 and MicroRNA-221-3p Levels in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Coronary Angiography. Adv Pharm Bull 2021, 11, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Chu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, M.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Y. Effect of psoralen on the regulation of osteogenic differentiation induced by periodontal stem cell-derived exosomes. Hum Cell 2023, 36, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, L.; Xue, B.; Xi, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, S. Exploration of Shared Gene Signatures and Molecular Mechanisms Between Periodontitis and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Genet 2022, 13, 939751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Ding, Y.Q.; Bi, X.Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, P.X.; Zhang, L.L.; Ye, J.T. MicroRNA-99b-3p promotes angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis in mice by targeting GSK-3beta. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Cheon, E.J.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.A. MicroRNA-127-5p regulates matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression and interleukin-1beta-induced catabolic effects in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65, 3141–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, K.; Yan, L.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, J. Celastrol mitigates high glucose-induced inflammation and apoptosis in rat H9c2 cardiomyocytes via miR-345-5p/growth arrest-specific 6. J Gene Med 2020, 22, e3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, G. miR-324-5p promotes adipocyte differentiation and lipid droplet accumulation by targeting Krueppel-like factor 3 (KLF3). J Cell Physiol 2020, 235, 7484–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sheng, J.; Dong, A.; Zhang, M.; Cao, L. miR-345-5p regulates adipogenesis via targeting VEGF-B. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 17114–17121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, T.; Xie, F.; Zhong, P.; Hua, H.; Lai, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. MiR-345-5p functions as a tumor suppressor in pancreatic cancer by directly targeting CCL8. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 111, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Gui, S.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, M. Upregulation of miR-345-5p suppresses cell growth of lung adenocarcinoma by regulating ras homolog family member A (RhoA) and Rho/Rho associated protein kinase (Rho/ROCK) pathway. Chin Med J (Engl) 2021, 134, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Mattes, L.M.; Kuffer, S.; Unger, K.; Hess, J.; Bertlich, M.; Haubner, F.; Ihler, F.; Canis, M.; Weiss, B.G.; et al. MicroRNA expression patterns in oral squamous cell carcinoma: hsa-mir-99b-3p and hsa-mir-100-5p as novel prognostic markers for oral cancer. Head Neck 2019, 41, 3499–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, Y.; Martinez-Moreno, M.; Alonso, L.; Sanchez-Vencells, A.; Arranz, A.; Daga-Millan, R.; Sevilla-Movilla, S.; Valeri, A.; Martinez-Lopez, J.; Teixido, J. Regulation of miRNA expression by alpha4beta1 integrin-dependent multiple myeloma cell adhesion. EJHaem 2023, 4, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, C.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y. MicroRNA-let-7a inhibition inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory injury of chondrocytes by targeting IL6R. Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 2633–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandri, C.; Stamatopoulos, B.; Rothe, F.; Bareche, Y.; Devos, M.; Demeestere, I. MicroRNA profiling and identification of let-7a as a target to prevent chemotherapy-induced primordial follicles apoptosis in mouse ovaries. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.H.; Li, L.C.; Yang, S.F.; Tsai, C.F.; Chuang, Y.T.; Chu, H.J.; Ueng, K.C. MicroRNA Let-7a, -7e and -133a Attenuate Hypoxia-Induced Atrial Fibrosis via Targeting Collagen Expression and the JNK Pathway in HL1 Cardiomyocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, H. Overexpression of X chromosome-linked inhibitor of apoptosis by inhibiting microRNA-24 protects periodontal ligament cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced cell apoptosis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2016, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Mao, Y.; Kang, Y.; He, L.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xu, D.; Shi, L. MicroRNA-127 Promotes Anti-microbial Host Defense through Restricting A20-Mediated De-ubiquitination of STAT3. iScience 2020, 23, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Lu, Y.; He, Q.X.; Wang, H.; Li, B.F.; Zhu, L.Y.; Xu, Q.Y. The Role of MicroRNA, miR-24, and Its Target CHI3L1 in Osteomyelitis Caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J Cell Biochem 2015, 116, 2804–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Rivera, M.; Minot, S.S.; Bouzek, H.; Wu, H.; Blanco-Miguez, A.; Manghi, P.; Jones, D.S.; LaCourse, K.D.; Wu, Y.; McMahon, E.F.; et al. A distinct Fusobacterium nucleatum clade dominates the colorectal cancer niche. Nature 2024, 628, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, P.J.; Gemmell, E.; Hamlet, S.M.; Hasan, A.; Walker, P.J.; West, M.J.; Cullinan, M.P.; Seymour, G.J. Cross-reactivity of GroEL antibodies with human heat shock protein 60 and quantification of pathogens in atherosclerosis. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2005, 20, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukkapalli, S.S.; Velsko, I.M.; Rivera-Kweh, M.F.; Zheng, D.; Lucas, A.R.; Kesavalu, L. Polymicrobial Oral Infection with Four Periodontal Bacteria Orchestrates a Distinct Inflammatory Response and Atherosclerosis in ApoE null Mice. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0143291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.W.; Redline, R.W.; Li, M.; Yin, L.; Hill, G.B.; McCormick, T.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 2272–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 2012, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzink, J.L.; Sheenan, M.T.; Socransky, S.S. Proposal of three subspecies of Fusobacterium nucleatum Knorr 1922: Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum subsp. nov., comb. nov.; Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum subsp. nov., nom. rev., comb. nov.; and Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. vincentii subsp. nov., nom. rev., comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1990, 40, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavalu, L.; Sathishkumar, S.; Bakthavatchalu, V.; Matthews, C.; Dawson, D.; Steffen, M.; Ebersole, J.L. Rat model of polymicrobial infection, immunity, and alveolar bone resorption in periodontal disease. Infection and immunity 2007, 75, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukkapalli, S.S.; Ambadapadi, S.; Varkoly, K.; Jiron, J.; Aguirre, J.I.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Morel, L.M.; Lucas, A.R.; Kesavalu, L. Impaired innate immune signaling due to combined Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 deficiency affects both periodontitis and atherosclerosis in response to polybacterial infection. Pathog Dis 2018, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukkapalli, S.S.; Easwaran, M.; Rivera-Kweh, M.F.; Velsko, I.M.; Ambadapadi, S.; Dai, J.; Larjava, H.; Lucas, A.R.; Kesavalu, L. Sequential colonization of periodontal pathogens in induction of periodontal disease and atherosclerosis in LDLRnull mice. Pathog Dis 2017, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velsko, I.M.; Chukkapalli, S.S.; Rivera-Kweh, M.F.; Zheng, D.; Aukhil, I.; Lucas, A.R.; Larjava, H.; Kesavalu, L. Periodontal pathogens invade gingiva and aortic adventitia and elicit inflammasome activation in alphavbeta6 integrin-deficient mice. Infect Immun 2015, 83, 4582–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindraja, C.; Sakthivel, R.; Liu, X.; Goodwin, M.; Veena, P.; Godovikova, V.; Fenno, J.C.; Levites, Y.; Golde, T.E.; Kesavalu, L. Intracerebral but Not Peripheral Infection of Live Porphyromonas gingivalis Exacerbates Alzheimer's Disease Like Amyloid Pathology in APP-TgCRND8 Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioce, M.; Rutigliano, D.; Puglielli, A.; Fazio, V.M. Butein-instigated miR-186-5p-dependent modulation of TWIST1 affects resistance to cisplatin and bioenergetics of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma cells. Cancer Drug Resist 2022, 5, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.; Cui, S.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xu, J.; Bao, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.; Zuo, H.; et al. miRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D222–D230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, I.S.; Zagganas, K.; Paraskevopoulou, M.D.; Georgakilas, G.; Karagkouni, D.; Vergoulis, T.; Dalamagas, T.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. DIANA-miRPath v3.0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, W460–W466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukkapalli, S.S.; Velsko, I.M.; Rivera-Kweh, M.F.; Larjava, H.; Lucas, A.R.; Kesavalu, L. Global TLR2 and 4 deficiency in mice impacts bone resorption, inflammatory markers and atherosclerosis to polymicrobial infection. Mol Oral Microbiol 2017, 32, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group/Bacteria/Weeks | Positive gingival plaque samples (n=10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks’ Time point | 16 weeks’ time point | |||

| 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | |

| Group I/ F. nucleatum ATCC 49256 [8 weeks] | 5/10a | 3/10 | 10/10 | --- |

| Group II/ Sham-infection [8 weeks] | 0/10 | NC | --- | --- |

| Group III/ F. nucleatum ATCC 49256 [16 weeks] | 6/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 | --- |

| Group IV/ Sham-infection [16 weeks] | 0/10 | NC | NC | 0/10 |

| Weeks/infection/sex | Upregulated miRNAs (p < 0.05) |

Downregulated miRNAs (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks – F. nucleatum-infected Vs 8 weeks – Sham infection (n = 10) |

7 (miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) | 2 (miR-362-3p, miR-720, miR-362-3p) |

| 8 weeks – F. nucleatum-infected female Vs male (n = 5) |

12 (miR-206, miR-210) | 12 (miR-376a, miR-350) |

| 16 weeks- F. nucleatum-infected Vs 16 weeks – sham infection (n = 10) |

7 (miR-361-5p, miR-99b-5p) | 13 (miR-323-3p, miR-488, miR-350) |

| 16 weeks – F. nucleatum-infected Female vs. male (n = 5) |

5 (miR-152, miR-125b-5p) | 14 (miR-375, miR-210, miR-376a, miR-362-3p) |

| 8 weeks – F. nucleatum-infected Vs 16 weeks F. nucleatum-infected (n = 10) |

14 (miR-133a, miR-22) | 47 (miR-323-3p, miR-1902) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).