1. Introduction

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV), a zoonotic arbovirus belonging to the

Phenuiviridae family was first detected in Kenya in 1930, and is associated with acute febrile illness in humans, and episodic abortions and juvenile mortality in livestock [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This mosquito-borne disease is a One health global threat that has caused extensive public health and economic devastations in Africa and the Middle East [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The epidemiology of RVFV disease is marked by large epidemics followed by inter-epidemic periods (IEPs) during which clinical disease in livestock and humans are rarely reported [

10]. While the disease has been well studied during epidemics documenting key geographic and ecological factors associated with disease occurrence, there is limited understanding of virus maintenance including enabling environmental and climatic factors, and burden of disease among livestock and humans during IEPs [

5,

6,

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These knowledge gaps hinder the establishment of effective surveillance, prevention strategies as well as adequate public health interventions and educational messaging.

The East Africa (EA) region has recently reported increasing frequency of small RVFV clusters in previously unaffected areas, associated with a combination of higher temperature and rainfall [

17]. The western highlands in Kenya and Uganda seem to have a particularly unique profile favorable for these RVF clusters [

18,

19]. With elevations exceeding 1200 and 1900 meters above sea level in Kenya and Uganda respectively, [

5,

17,

18,

19] these highlands are not among typical RVFV hotspots, which are characterized by low elevation (<500 meters above sea level), arid and semi-arid conditions, and susceptibility to flooding [

20].

Previous analysis of long-term climatic trends in EA region revealed an annual mean temperature increase of up to 0.12

° to 0.3°C per decade in parts of East Africa, indicating a rise in annual average temperatures of up to 1.2°C over the past 40 years, contributing to escalating frequency and severity of droughts in the arid and semi-arid lowlands [

17,

21,

22]. In the highlands of southwestern Uganda and Kenya, rising temperature accompanied by increasing rainfall trends were associated with significantly increasing frequencies of RVF clusters [

17]. This emerging evidence of increasing RVF disease activities in the highlands and other novel geographical settings suggests an increase in the spread of the virus and a greater risk of widespread RVF epidemics in the future. Here we investigated a cryptic RVF virus maintenance cycle existed in the EA highlands associated with sustained prevalence of RVFV in humans and livestock.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A prospective two-year hospital-based study was conducted on febrile patients between March 2022 and February 2024, followed by a 10-day community-based human-animal linked cross-sectional study among randomly selected households in August 2023 in Murang’a County, central Kenya. The objective was to investigate the seroprevalence of RVFV and factors associated with seropositivity in humans and livestock.

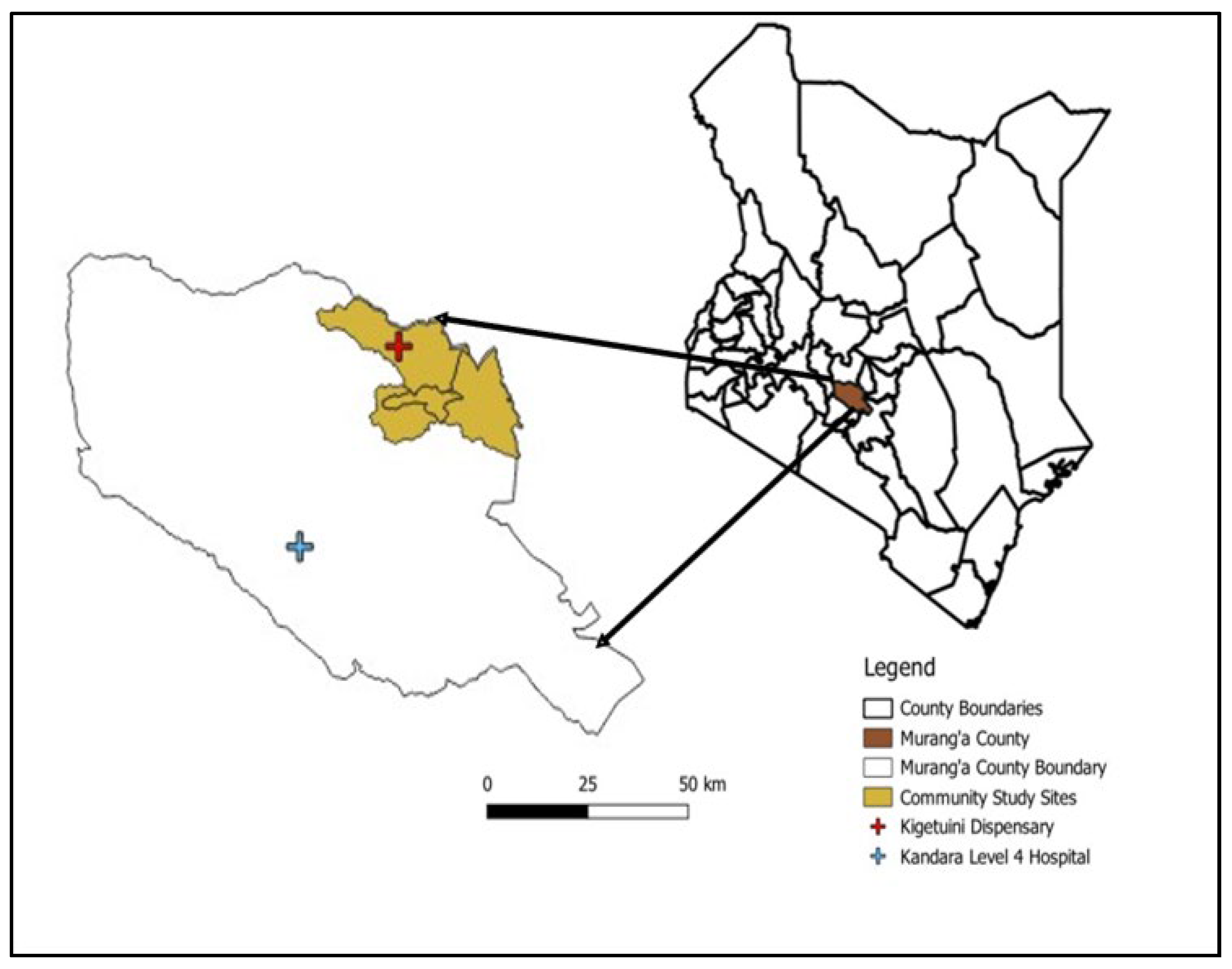

2.2. Study Area

Murang’a County, located in Kenya’s central highlands is a high-altitude region (

Figure 1) with elevations ranging from 914 to 3,353 meters above sea level, with most areas situated above 1,200 meters [

18]. Farming is the main economic activity, with 80% of the population cultivating both food (maize, bananas) and cash crops (tea, coffee). Livestock rearing and mining are also practiced [

18]. The hospital-based study was conducted at two healthcare facilities: Kandara Level III Sub-County Hospital and Kigetuini Level I dispensary, which were selected based on past reports of RVFV activity in Murang’a County. The cross-sectional human-animal study was conducted in Murang’a East sub-county, covering Gaturi, Mbiri, and Township wards. This site was purposively selected due to higher RVFV IgG seropositivity of febrile patients detected in the hospital study.

2.3. Sampling Method and Sample Size

Febrile patients aged ≥10 years seeking care at the facilities for undifferentiated acute fever (≥37.5°C, at presentation or reported in the past four weeks), unexplained bleeding, or a severe illness of unknown etiology lasting ≥7 days despite treatment were eligible. We included 20% of malaria-positive cases to account for the overlap in risk factors between malaria and RVFV. Patients with specific infections (e.g., upper respiratory or urinary tract infections) and those with reported blood clotting disorders were excluded. A minimum sample size of 707 participants per healthcare facility was estimated based on an 8% RVFV prevalence in hotspots, 80% power, 2% precision, and a 95% confidence level [

13].

A two-stage sampling approach was used in the community study. First, households were randomly selected, with the selection in each ward proportional to its population density. Within these households, individual livestock and humans served as the primary sampling units. Human participants were chosen at random, while livestock (cattle, sheep, and goats) were selected based on convenience. To identify study households, 350 random geographical coordinates in Murang’a East sub-county were generated using ArcGIS. This was based on a target sample size of 203, adjusted for a 30% decline rate and a 25% inaccessibility rate. Study teams used handheld GPS devices (Garmin eTrex

®) and assigned geocodes to locate points. The nearest household within 100 meters of each point was recruited. If no household was found or if the household head declined to participate, a backup point from a spare list was used. Assumed proportions were 5% for humans, 20.5% for cattle, and 5% each for sheep and goats (25). A design effect (D) of 1.3 was applied to the livestock sample size using the formula: D = 1 + (n−1) ρ, where ρ is the intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) and n is the average cluster size. For 2% precision and 95% confidence, we estimated minimum sample size of 203 humans, 145 cattle, and 264 each of sheep and goats [

19]. Both livestock (cattle, sheep, and goats) and non-livestock-owning households were eligible. For livestock-owning households, eligibility included owning at least one of the three livestock species (cattle, sheep, or goats), no history of RVFV vaccination, a consenting human. All ages of livestock were eligible, with a maximum of two animals per species. In non-livestock owning households, we sampled one consenting human, excluding children <1 year.

2.4. Participant Management

In the hospital-based study, participants who met the inclusion criteria were consented, given physical examination, and questionnaire administered, and a blood sample collected. Participants returned 4-6 weeks later for a convalescent blood draw and a follow-up data collection.

In the community study, once a household was selected and consented, individuals within that household were listed then assigned numbers and a randomization software was used to select the individual to be included in the study. Only one individual per household was selected. The respondent was consented, and a questionnaire was administered to capture demographic and potential risk factors data at individual and household level. For households with livestock the owner was consented, and a maximum of two animals of either cattle, goats, or sheep were conveniently selected and animal-level data was collected using a questionnaire. Blood samples were collected from both humans and livestock.

2.5. Data Collection

Febrile patients aged ≥10 years seeking care at the facilities for undifferentiated acute fever (≥37.5°C, at presentation or reported in the past four weeks), unexplained bleeding, or a severe illness of unknown etiology lasting ≥7 days despite treatment were eligible. We included 20% of malaria-positive cases to account for the overlap in risk factors between malaria and RVFV. Patients with specific infections (e.g., upper respiratory or urinary tract infections) and those with reported blood clotting disorders were excluded. A minimum sample size of 707 participants per healthcare facility was estimated based on an 8% RVFV prevalence in hotspots, 80% power, 2% precision, and a 95% confidence level [

13].

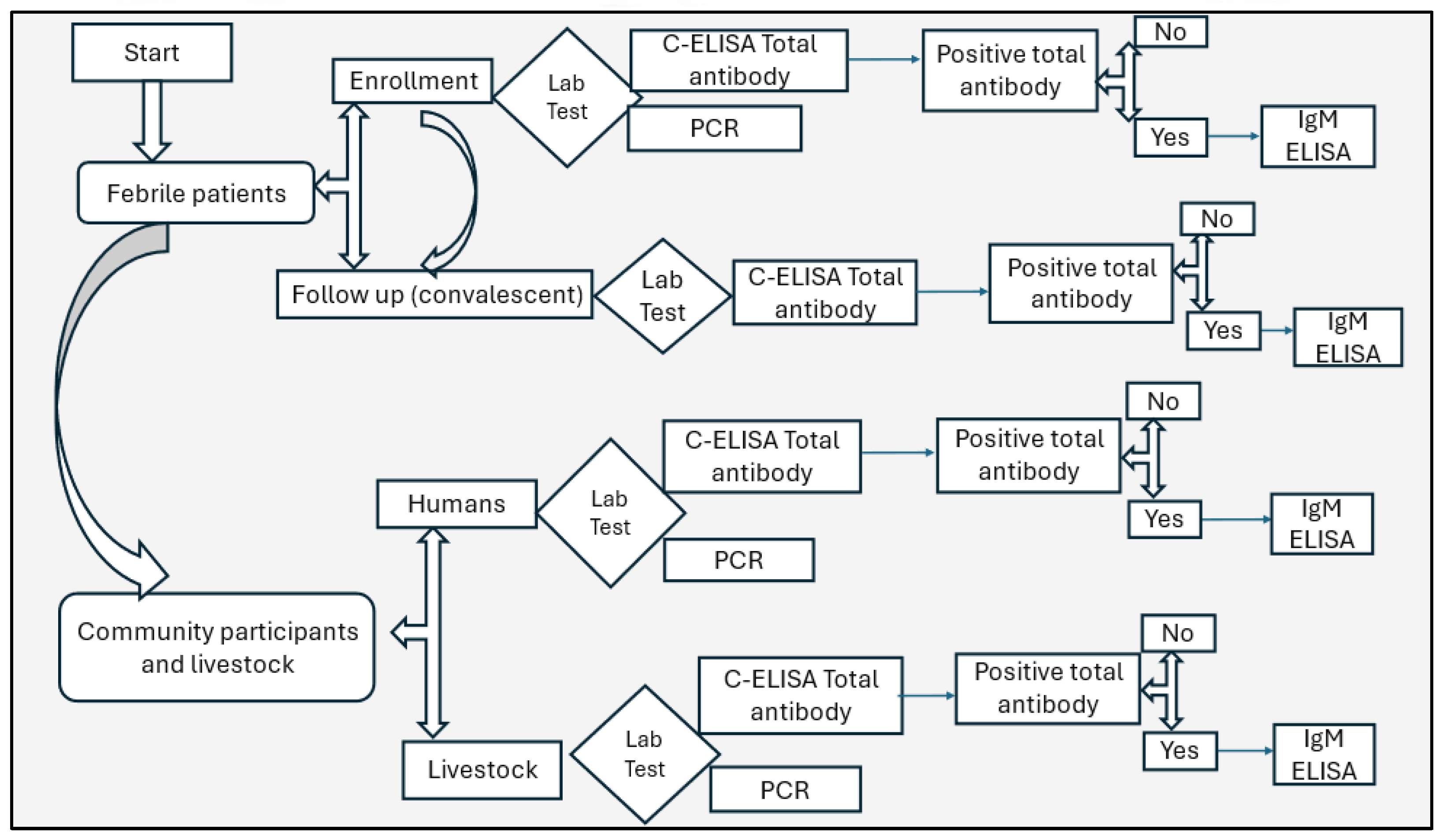

2.6. Sampling Collection and Testing

Four (4mL) of blood were collected from humans and six (6mL) from livestock using aseptic techniques into plain tubes. Samples were transported in cold chain (2-80 C) to the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) laboratory in Nairobi, centrifuged, sera, aliquoted into barcoded cryovials, and stored at -20°C. Samples were tested for RVFV total antibodies using competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (C-ELISA), IgM antibodies using IgM capture ELISA (for total antibodies positive only), and RVFV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR),

Figure 2.

2.7. Competitive Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (C-ELISA)

The detection of IgG and IgM antibodies against the nucleoprotein (NP) was carried out using a multi-species RVFV competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent commercial Assay (C-ELISA) from IDvet

® (Grabels, France). Briefly, sera were diluted serially in duplicates and added to 96-well polystyrene plates that were precoated with a recombinant RVFV-NP. Test samples and controls were then added to the microwells. The anti-NP antibodies in the serum formed an antigen-antibody complex which masked the NP epitopes. Peroxidase conjugated anti-NP antibodies were detected through substrate-based absorbance (optical density) reading using positive control as standard. Nucleoprotein-peroxidase conjugate (Po) was added to the microwells to bind free NP epitopes and form an antigen-conjugate-peroxidase complex. After washing away excess conjugate, the substrate solution was added and finally after incubating, the stop solution was added, and absorbance was measured. The results were interpreted using the cut-off threshold specified by the manufacturer. All samples were run in duplicate, and the test was valid if the mean value of the positive control optical density (ODPC) was less than 30% of the negative control (ODNC), given as ODPC/ODNC < 0.3 and if the mean value of the negative control optical density (ODNC) was greater than 0.7, given as ODNC > 0.7. All runs met these criteria, and indeterminate samples were considered negative. Test results were validated through duplicate assays. The IDvet kit reports diagnostic sensitivity and specificity rates of 98% and 100%, respectively [

24].

2.8. Specific IgM ELISA Detection

Febrile patients aged ≥10 years seeking care at the facilities for undifferentiated acute fever (≥37.5°C, at presentation or reported in the past four weeks), unexplained bleeding, or a severe illness of unknown etiology lasting ≥7 days despite treatment were eligible. We included 20% of malaria-positive cases to account for the overlap in risk factors between malaria and RVFV. Patients with specific infections (e.g., upper respiratory or urinary tract infections) and those with reported blood clotting disorders were excluded. A minimum sample size of 707 participants per healthcare facility was estimated based on an 8% RVFV prevalence in hotspots, 80% power, 2% precision, and a 95% confidence level [

13].

2.9. PCR Assay

The molecular analysis involved RT-PCR detection of viral RNA in serum samples using the QIAamp Viral Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, we used primers and probes targeting the G2 gene to extract and amplify RVFV RNA from sera using a TaqMan real-time RT-PCR assay. A 25-μL reaction mix was prepared with 12.5 μL of 2× RT-PCR buffer, 1 μL of 25× RT-PCR enzyme, 0.25 μL each of forward primer, reverse primer, and probe (all 40 µM), and 5.75 μL of nuclease-free water. This was followed by adding 5 microliters of RNA template and inclusion of RVFV-positive and negative controls. Amplification was performed on the Rotor-Gene® Q real-time PCR system with reverse transcription at 50°C for 30 minutes, Taq activation at 95°C for 15 minutes, and 45 PCR cycles at 94°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Samples with a cycle threshold ≤ 37 were considered positive.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized by mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were summarized by proportions. RVFV seroprevalence and its 95% confidence interval were estimated using the ‘epi.prev’ function in the EpiR package. The significance of factors associated with RVFV seropositivity was first determined using Fisher’s χ2 with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. Logistic regression was used for univariable analysis to identify variables of interest based on prior studies and biological plausibility (

Supplementary Table S2). Variables with a p-value <0.2 in univariable regression and other variables that did not fulfill this criterion, but where an association with RVFV IgG seemed likely due to biological reasons were included in the multivariable analysis. The variables were then evaluated using a backward stepwise elimination and validated with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Explanatory variables were considered confounders if removing them from the model altered the coefficients of other significant variables by 30% or more. Serological status (positive or negative anti-RVFV IgG ELISA) was the dependent variable. Separate logistic regression models were developed for livestock and humans using the ‘glm’ function in the lme4 R package. All analyses were performed with R version 4.1.0 [

25].

2.11. Ethical Approval

The study received ethical approval from the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI/SERU/CGHR/4169) and the Kenyatta National Hospital - University of Nairobi ethical review committee (P810/10/2022), the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation [NACOSTI/P/23/24072]. Before enrollment, adult human participants provided written informed consent. While parental consent was obtained for children aged 1-9 years and assent for children aged 10-17 years. Livestock protocol was reviewed and approved by the KEMRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval # KEMRI/ACUC/01.09.2021) and sampling consent obtained from livestock owners.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Human Participants

The study enrolled 1,750 human participants (1,468 febrile patients and 282 community members) with a median age of 37.1 (IQR: 25-49) years (

Table 1). Of all participants, 59.4% (n=1,040) attained primary level of education, 51.8% (n=906) were female, 35.9% (n=628) were engaged in farming, 10.5% (n=184) were students, 9.1% (n=160) were in formal employment and 43.1% (n=754) were involved in other occupation types (including business, transportation “boda boda” and informal employment). Most (79.2%) participants reported owning livestock including cattle (73.0%), goats (60.4%) and sheep (8.6%). Almost all (94.0%, n=1,645) participants reporting contact with livestock, including feeding (77.8%), handling of raw meat during cooking (57.9%), and cleaning animal barns (57.9%), (

Table 1).

3.2. Characteristics of Livestock

We sampled 706 animals in the community cross-sectional study, including 38.4% (n=271) cattle, 49.0% (n=346) goats, and 12.6% (n=89) sheep from 255 households (

Table 2). Majority 74.9% (n=529) of the animals were female while 67.2% (n=182) were adults.

3.3. Environmental Risk Factor Analysis

Although 62.3% (n=1,091) participants reported not using any mosquito prevention, 83.5% (n=1,461) reported presence of mosquitoes within their homesteads,

Supplementary Table S1. In addition, 45.5% (n=797) and 42.2% (n=738) participants reported residing near quarries and wildlife, respectively. The association between independent risk factors and RVFV seropositivity is shown in

Supplementary Table S1.

3.4. RVFV Prevalence in Humans

None of the sera from 1,468 febrile human patients, and 282 asymptomatic community members were positive for RVFV RNA by PCR. However, 34 of 1,705 (2.0%, 95% CI: 1.38–2.78) were positive for anti-RVF virus IgG antibodies (

Table 1). Butchers showed the highest seropositivity at 14.3%, (95% CI: 0.36–57.87), followed by farmers at 3.2% (95% CI: 1.96–4.88). As shown in

Table 1, participants reporting animal contact including birthing, herding, milking, and slaughtering showed significantly higher RVFV seropositivity (p<0.05). In addition, RVF seropositivity was significantly higher among participants residing near quarries, swamps, and wildlife. An important finding was that 4 of 1,468 (0.27%, 95% CI: 0.07–0.69) febrile participants followed up 4-6 weeks later showed four-fold increase in IgG levels, suggesting recent RVFV exposure. Although animals had higher seropositivity rates, there were no significant associations between the types of livestock kept, the contact with different livestock species, and human seropositivity, (

Supplementary Table S3). A univariate analysis was performed to assess whether animal seropositivity was associated with human RVFV seropositivity at the household level. The results indicated no significant association, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.85 (95% CI: 0.04–19.8, p = 0.4777).

3.5. RVFV Prevalence in Livestock

None of the sera from 706 livestock were positive for RVFV RNA by PCR. However, 4.4% (n=31, 95% CI: 3.00–6.17) were positive for anti-RVF virus IgG antibodies, while at herd level, 24 of the 255 herds (9.4%, 95% CI: 6.12–13.68) had at least one positive animal (

Table 2). Seropositivity was significantly different 8.1% (95% CI: 5.16–12.03, p<0.05) among cattle, 2.1% (95% CI: 0.95–3.89) among goats, while all sheep (n=89) were seronegative. Higher seropositivity (5.5%, 95% CI: 1.24–11.11) was observed in females than males 1.1% (95% CI: 0.14–4.02), and in adult (9.9%, 95% CI: 5.97–15.18) than young 4.5% (95% CI: 5.16–12.03) animals.

3.6. Multivariable Analysis of Human Risk Factors of RVFV Seropositivity

The multivariable model fitted to the human data identified age, sex, animal contact and proximity to quarries as significant predictors for RVFV seropositivity (

Table 3). The model showed an increase in the odds of RVFV exposure with being male (aOR:4.77, 95% CI: 2.08–12.4, p:<0.001), and residing near a quarry (aOR:2.4, 95% CI: 1.08–5.72, p:0.038). Respondents who engaged in milking were 2.69 times more likely to test positive for anti-RVFV IgG (aOR:2.69, 95% CI: 1.23–6.36, p:0.017) while those who consumed raw milk were 5.24 more likely to be positive (aOR:5.24, 95% CI: 1.13–17.9, p:0.015).

3.7. Factors Associated with RVFV Seropositivity in Livestock

The multivariable model fitted to the animal data showed that small ruminants were 0.27 times less likely to be positive for RVFV IgG antibodies compared to cattle (aOR 0.27, 95% CI: 0.12–0.65, p:0.002). Breed, age, sex and herd size did not show any associations with RVFV seropositivity.

Table 4.

Regression analysis for factors associated with RVFV seropositivity among livestock (n=706) in Murang’a County, Kenya.

Table 4.

Regression analysis for factors associated with RVFV seropositivity among livestock (n=706) in Murang’a County, Kenya.

| Multivariable model |

|---|

| Characteristic |

Variable |

aOR |

95% CI1

|

p-value |

| Livestock species |

Cattle (Ref) |

— |

— |

|

| |

Small ruminants |

0.27 |

0.12, 0.60 |

0.002* |

| Breed distribution |

Cross (Ref) |

— |

— |

|

| |

Exotic |

1.79 |

0.57, 7.85 |

0.4 |

| |

Local |

2.28 |

0.64, 10.6 |

0.2 |

| Animal age |

Adult >12 months (Ref) |

— |

— |

|

| |

Young <12 months |

0.5 |

0.16, 1.24 |

0.2 |

| Sex |

Female (Ref) |

— |

— |

|

| |

Male |

0.29 |

0.05, 1.04 |

0.1 |

| Livestock herd size |

>5 animals (Ref) |

— |

— |

|

| |

1 — 5 animals |

0.6 |

0.27, 1.26 |

0.2 |

| aOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio, 1CI = Confidence Interval; *Statistically significant, |

4. Discussion

Although most highlands of East Africa lack the geo-ecological landmarks of RVF hotspots that are involved in historical RVF outbreaks in the East Africa region, recent studies have detected a growing number of small RVF disease cluster (<2 human and <5 livestock cases) in these highlands [

17,

26]. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate whether continuous cryptic RVF cycling occurred in a central highland of Kenya. The finding reported here document a seroprevalence of 4.4% in livestock, and 2.0% in humans, levels comparable to those observed in regional non-RVF hotspots [

16,

27,

28,

29,

30]. More importantly, we demonstrated evidence of recent RVFV exposure among 0.27% humans, illustrated by a fourfold increase in IgG antibodies in four febrile patients, and 2.4% among young livestock (<12 months old), suggesting recurrent RVFV exposure in the area associated with cryptic circulation of the virus.

The significant human risk factors associated with RVFV exposure were consumption of raw milk (aOR=5.24), sex (aOR=4.77), contact with animals (aOR=2.69), and residing near a quarry (aOR=2.4). These factors highlight the pathways through which RVFV primarily spreads, confirming that the long-held opinion that human-to-human transmission, if it occurs at all, has minimal public health significance. Despite limited data on milk’s infectious nature, recent studies have identified raw milk as a factor associated with RVFV exposure [

10,

31,

32]. Consumption of raw milk suggests an alternative potential transmission route that may not require direct livestock contact. These findings are consistent with previously documented epidemiological patterns of RVFV [

5,

6,

7,

11,

14,

33,

34].

Our results are consistent with some studies in Kenya showing similar seroprevalences during non-outbreak periods in other non-RVF hotspots, include the Lake Victoria region and in the Western Kenya highlands [

27]. The results contrast with studies from hyper-endemic regions with suitable habitat for RVFV vector survival. For instance, studies in Baringo, Isiolo, Tana River and Garissa, have found higher RVFV seroprevalence rates of 13 to 27%, which are likely due to higher force of infection and virus circulation [

5,

7,

14,

15,

33,

35,

36,

37]. These differences could be due to variations vector density ecologies that drive infection, low risk practices, lower rates of infection and sparse population demographics that minimize exposure risks [

34,

38]. The low seroprevalence observed may also be due to possible clustering of cases in areas not yet investigated or activity due to a less virulent viral lineage [

38].

A limitation of the study is our inability to correlate our serological (ELISA) findings with the confirmatory plaque reduction neutralization tests for RVFV (PRNT). However, previous studies have demonstrated comparable performances between ELISA and PRNT. The estimated diagnostic sensitivity of ELISA was 0.854 (95% Bayesian Credible Interval [BCI]: 0.655–0.991) and specificity was 0.986 (95% BCI: 0.971–0.998). In comparison, the PRNT test showed a sensitivity of 0.844 (95% BCI: 0.660–0.973) and specificity of 0.981 (95%BCI: 0.965–0.996), [

39].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights sustained RVFV seroprevalence among humans and livestock in central highlands of Kenya and identifies key risk factors for exposure. The findings confirm the existence of a cryptic RVFV maintenance cycle in this ecosystem, which requires further studies to understand the mosquito vectors involved, and impact of climatic variability on the process. Taken in the context of other findings reporting increasing RVFV disease activities in the highlands, it represents broader dispersal of the virus and greater risk of more widespread RVFV epidemics in future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Table S1. Environmental risk factors for RVFV seropositivity, Supplementary Table S2. Livestock risk factors for RVFV seropositivity and Supplementary Table S3. Predictor variables collected and their measurements.

Author Contributions

S.S., L.N., J.D., R.B., M.K.N.; conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing original draft and writing-review and editing; E.C., R.O., M.M.; M.M.; M.M., B.G., L.K., S.A., E.O., I.N., E.O., J.D., B.B., R.B., M.K.N.; supervision, writing-review, and editing. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the project was provided by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH), grants number U01AI151799 through the Centre for Research in Emerging Infectious Diseases-East and Central Africa (CREID-ECA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI/SERU/CGHR/4169) and the Kenyatta National Hospital - University of Nairobi ethical review committee (P810/10/2022), the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation [NACOSTI/P/23/24072]. Livestock protocol was reviewed and approved by the KEMRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval # KEMRI/ACUC/01.09.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Before enrollment, adult human participants provided written informed consent. While parental consent was obtained for children aged 1-9 years and assent for children aged 10-17 years. Livestock farmers gave a written consent before being interviewed, including consent for samples collected from their animals. Animal safety and welfare was ensured by using appropriate restraining methods (barley rope or halter methods) and observance of aseptic techniques when bleeding cattle, sheep and goats.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data used to support the findings of this study can be provided by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the collaborative support from the Ministries of Health and Agriculture in Kenya. Funding for the project was provided by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH), grants number U01AI151799 through the Centre for Research in Emerging Infectious Diseases-East and Central Africa (CREID-ECA). We acknowledge Silvia Situma’s training support from the NIH/Fogarty International Center’s D43 training grant # D43TW011519 to Washington State University and University of Nairobi (UON), and UON’s Building Capacity for Writing Scientific Manuscripts (UANDISHI) Program supported by the American People through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Daubney, R, and JR Hudson. 1931. “Enzootic Hepatitis or Rift Valley Fever. An Un-Described Virus Disease of Sheep, Cattle and Man from East Africa.”.

- Ikegami, Tetsuro, and Shinji Makino. 2011. “The Pathogenesis of Rift Valley Fever.” Viruses 3 (5): 493–519.

- Manore, C. A., and B. R. Beechler. 2015. “Inter-Epidemic and between-Season Persistence of Rift Valley Fever: Vertical Transmission or Cryptic Cycling?” Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 62 (1): 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Mroz, Claudia, Mayada Gwida, Maged El-Ashker, Mohamed El-Diasty, Mohamed El-Beskawy, Ute Ziegler, Martin Eiden, and Martin H. Groschup. 2017. “Seroprevalence of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Livestock during Inter-Epidemic Period in Egypt, 2014/15.” BMC Veterinary Research 13 (1): 87. [CrossRef]

- Murithi, RM, P Munyua, PM Ithondeka, JM Macharia, A Hightower, ET Luman, RF Breiman, and M Kariuki Njenga. 2011. “Rift Valley Fever in Kenya: History of Epizootics and Identification of Vulnerable Districts.” Epidemiology & Infection 139 (3): 372–80.

- Nanyingi, Mark O., Peninah Munyua, Stephen G. Kiama, Gerald M. Muchemi, Samuel M. Thumbi, Austine O. Bitek, Bernard Bett, Reese M. Muriithi, and M. Kariuki Njenga. 2015. “A Systematic Review of Rift Valley Fever Epidemiology 1931-2014.” Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 5:28024. [CrossRef]

- Clark, Madeleine HA, George M Warimwe, Antonello Di Nardo, Nicholas A Lyons, and Simon Gubbins. 2018. “Systematic Literature Review of Rift Valley Fever Virus Seroprevalence in Livestock, Wildlife and Humans in Africa from 1968 to 2016.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 12 (7): e0006627.

- Bron, Gebbiena M., Kathryn Strimbu, Hélène Cecilia, Anita Lerch, Sean M. Moore, Quan Tran, T. Alex Perkins, and Quirine A. ten Bosch. 2021. “Over 100 Years of Rift Valley Fever: A Patchwork of Data on Pathogen Spread and Spillover.” Pathogens 10 (6): 708. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2018. “2018 Annual Review of Diseases Prioritized under the Research and Development Blueprint.” 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2018/02/06/default-calendar/2018-annual-review-of-diseases-prioritized-under-the-research-anddevelopment-blueprint.

- Glanville, William A. de, James M. Nyarobi, Tito Kibona, Jo E. B. Halliday, Kate M. Thomas, Kathryn J. Allan, Paul C. D. Johnson, et al. 2022. “Inter-Epidemic Rift Valley Fever Virus Infection Incidence and Risks for Zoonotic Spillover in Northern Tanzania.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 16 (10): e0010871. [CrossRef]

- Wright, Daniel, Jeroen Kortekaas, Thomas A. Bowden, and George M. Warimwe. 2019. “Rift Valley Fever: Biology and Epidemiology.” The Journal of General Virology 100 (8): 1187–99. [CrossRef]

- Nyakarahuka, Luke, Jackson Kyondo, Carson Telford, Amy Whitesell, Alex Tumusiime, Sophia Mulei, Jimmy Baluku, et al. 2023. “A Countrywide Seroepidemiological Survey of Rift Valley Fever in Livestock, Uganda, 2017.” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 109 (3): 548–53. [CrossRef]

- Nyakarahuka, Luke, Annabelle de St Maurice, Lawrence Purpura, Elizabeth Ervin, Stephen Balinandi, Alex Tumusiime, Jackson Kyondo, et al. 2018. “Prevalence and Risk Factors of Rift Valley Fever in Humans and Animals from Kabale District in Southwestern Uganda, 2016.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 12 (5): e0006412. [CrossRef]

- Mbotha, D., B. Bett, S. Kairu-Wanyoike, D. Grace, A. Kihara, M. Wainaina, A. Hoppenheit, P.-H. Clausen, and J. Lindahl. 2018. “Inter-Epidemic Rift Valley Fever Virus Seroconversions in an Irrigation Scheme in Bura, South-East Kenya.” Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 65 (1): e55–62. [CrossRef]

- Gerken, Keli N., A. Desirée LaBeaud, Henshaw Mandi, Maïna L’Azou Jackson, J. Gabrielle Breugelmans, and Charles H. King. 2022. “Paving the Way for Human Vaccination against Rift Valley Fever Virus: A Systematic Literature Review of RVFV Epidemiology from 1999 to 2021.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 16 (1): e0009852. [CrossRef]

- Grossi-Soyster, Elysse, Justin Lee, Charles King, and A. Labeaud. 2019. “The Influence of Raw Milk Exposures on Rift Valley Fever Virus Transmission.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 13 (March):e0007258. [CrossRef]

- Situma, Silvia, Luke Nyakarahuka, Evans Omondi, Marianne Mureithi, Marshal Mutinda Mweu, Matthew Muturi, Athman Mwatondo, et al. 2024. “Widening Geographic Range of Rift Valley Fever Disease Clusters Associated with Climate Change in East Africa.” BMJ Global Health 9 (6). [CrossRef]

- Murang’a County. 2022. “Murang’a County Annual Development Plan 2022/2023.” Murang’a County Government. https://repository.kippra.or.ke/handle/123456789/3736.

- Budasha, Ngabo Herbert, Jean-Paul Gonzalez, Tesfaalem Tekleghiorghis Sebhatu, and Ezama Arnold. 2018. “Rift Valley Fever Seroprevalence and Abortion Frequency among Livestock of Kisoro District, Southwestern Uganda (2016): A Prerequisite for Zoonotic Infection.” BMC Veterinary Research 14 (1): 271. [CrossRef]

- Kariuki Njenga, M., and Bernard Bett. 2019. “Rift Valley Fever Virus—How and Where Virus Is Maintained During Inter-Epidemic Periods.” Current Clinical Microbiology Reports 6 (1): 18–24. [CrossRef]

- UNEP. 2021. “UNEP Climate Action Note | Data You Need to Know.” November 9, 2021. https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/climate-action/what-we-do/climate-action-note/state-of-the-climate.html.

- Kilavi, Mary, Dave MacLeod, Maurine Ambani, Joanne Robbins, Rutger Dankers, Richard Graham, Helen Titley, Abubakr A. M. Salih, and Martin C. Todd. 2018. “Extreme Rainfall and Flooding over Central Kenya Including Nairobi City during the Long-Rains Season 2018: Causes, Predictability, and Potential for Early Warning and Actions.” Atmosphere 9 (12): 472. [CrossRef]

- Harris, Paul A., Robert Taylor, Brenda L. Minor, Veida Elliott, Michelle Fernandez, Lindsay O’Neal, Laura McLeod, et al. 2019. “The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners.” Journal of Biomedical Informatics 95 (July):103208. [CrossRef]

- Kainga, Henson, Marvin Collen Phonera, Elisha Chatanga, Simegnew Adugna Kallu, Prudence Mpundu, Mulemba Samutela, Herman Moses Chambaro, et al. 2022. “Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Rift Valley Fever in Livestock from Three Ecological Zones of Malawi.” Pathogens 11 (11): 1349. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. “R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.” 2021. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Wang, Zekun, Shaojun Pei, Runze Ye, Jingyuan Chen, Nuo Cheng, Mingchen Zhao, Wuchun Cao, and Zhongwei Jia. 2024. “Increasing Evolution, Prevalence, and Outbreaks for Rift Valley Fever Virus in the Process of Breaking Geographical Barriers.” Science of The Total Environment 917:170302. [CrossRef]

- Cook, Elizabeth Anne Jessie, Elysse Noel Grossi-Soyster, William Anson de Glanville, Lian Francesca Thomas, Samuel Kariuki, Barend Mark de Clare Bronsvoort, Claire Njeri Wamae, Angelle Desiree LaBeaud, and Eric Maurice Fèvre. 2017. “The Sero-Epidemiology of Rift Valley Fever in People in the Lake Victoria Basin of Western Kenya.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11 (7): e0005731. [CrossRef]

- LaBeaud, A Desiree, Eric M Muchiri, Malik Ndzovu, Mariam T Mwanje, Samuel Muiruri, Clarence J Peters, and Charles H King. 2008. “Interepidemic Rift Valley Fever Virus Seropositivity, Northeastern Kenya.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 14 (8): 1240.

- M. S. Kumalija et al., “Detection of Rift Valley Fever virus inter-epidemic activity in Kilimanjaro Region, Northeastern Tanzania,” Glob Health Action, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 1957554, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sindato, Calvin, Esron D Karimuribo, Francesco Vairo, Gerald Misinzo, Mark M Rweyemamu, Muzamil Mahdi Abdel Hamid, Najmul Haider, Patrick K Tungu, Richard Kock, and Susan F Rumisha. 2022. “Rift Valley Fever Seropositivity in Humans and Domestic Ruminants and Associated Risk Factors in Sengerema, Ilala, and Rufiji Districts, Tanzania.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 122:559–65.

- Grossi-Soyster, Elysse, Justin Lee, Charles King, and A. Labeaud. 2019. “The Influence of Raw Milk Exposures on Rift Valley Fever Virus Transmission.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 13 (March):e0007258. [CrossRef]

- Sumaye, Robert David, Emmanuel Nji Abatih, Etienne Thiry, Mbaraka Amuri, Dirk Berkvens, and Eveline Geubbels. 2015. “Inter-Epidemic Acquisition of Rift Valley Fever Virus in Humans in Tanzania.” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 9 (2): e0003536. [CrossRef]

- Linthicum, Kenneth J., Seth C. Britch, and Assaf Anyamba. 2016. “Rift Valley Fever: An Emerging Mosquito-Borne Disease.” Annual Review of Entomology 61:395–415. [CrossRef]

- Muturi, Mathew, Athman Mwatondo, Ard M. Nijhof, James Akoko, Richard Nyamota, Anita Makori, Mutono Nyamai, et al. 2023. “Ecological and Subject-Level Drivers of Interepidemic Rift Valley Fever Virus Exposure in Humans and Livestock in Northern Kenya.” Scientific Reports 13 (1): 15342. [CrossRef]

- Tigoi, Caroline, Rosemary Sang, Edith Chepkorir, Benedict Orindi, Samuel Okello Arum, Francis Mulwa, Gladys Mosomtai, et al. 2020. “High Risk for Human Exposure to Rift Valley Fever Virus in Communities Living along Livestock Movement Routes: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Kenya.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 14 (2). [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Abdala, Mathew Muturi, Athman Mwatondo, Jack Omolo, Bernard Bett, Solomon Gikundi, Limbaso Konongoi, et al. 2020. “Epidemiological Investigation of a Rift Valley Fever Outbreak in Humans and Livestock in Kenya, 2018.” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103 (4): 1649–55. [CrossRef]

- Mosomtai, Gladys, Magnus Evander, Per Sandström, Clas Ahlm, Rosemary Sang, Osama Ahmed Hassan, Hippolyte Affognon, and Tobias Landmann. 2016. “Association of Ecological Factors with Rift Valley Fever Occurrence and Mapping of Risk Zones in Kenya.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases: IJID: Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 46 (May):49–55. [CrossRef]

- Bett, Bernard, Johanna Lindahl, and Grace Delia. 2019. “Climate Change and Infectious Livestock Diseases: The Case of Rift Valley Fever and Tick-Borne Diseases.” In The Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers: Investigating the Business of a Productive, Resilient and Low Emission Future, edited by Todd S. Rosenstock, Andreea Nowak, and Evan Girvetz, 29–37. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bronsvoort, Barend M. C. de, Jean-Marc Bagninbom, Lucy Ndip, Robert F. Kelly, Ian Handel, Vincent N. Tanya, Kenton L. Morgan, Victor Ngu Ngwa, Stella Mazeri, and Charles Nfon. 2019. “Comparison of Two Rift Valley Fever Serological Tests in Cameroonian Cattle Populations Using a Bayesian Latent Class Approach.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science 6 (August). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).