Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

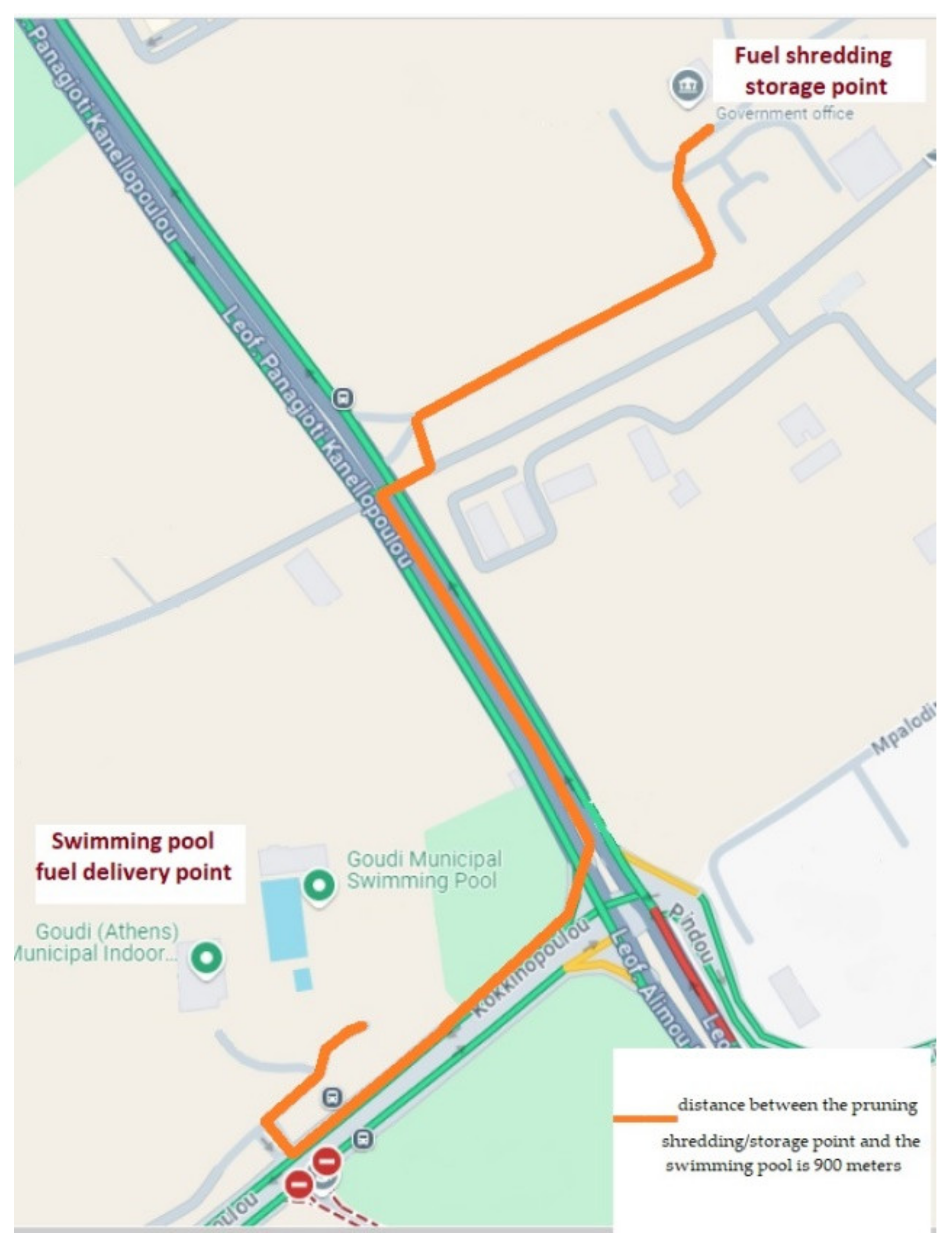

2.2. Methodological Approach to Biomass Boiler Unit Assessment in the Goudi Municipal Swimming Pool Area

2.2.1. Technical Information Equipment Description

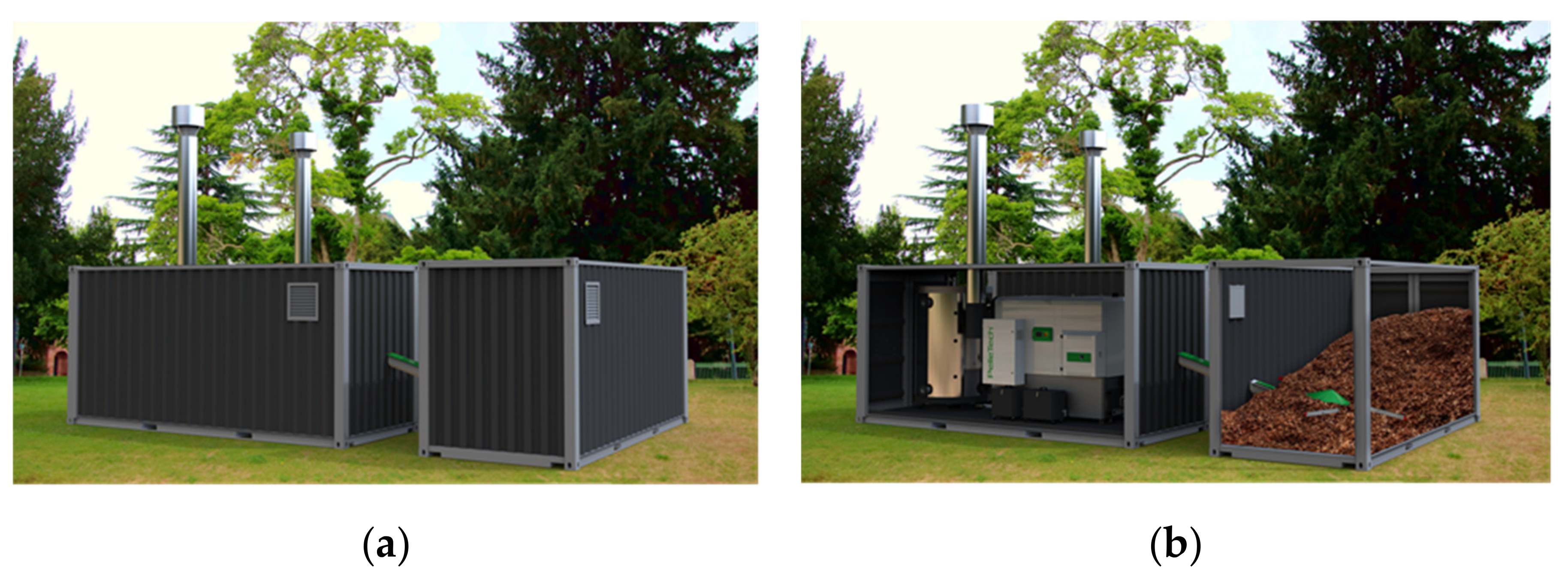

- 2 × Containerized Pelletech IDRO 500 (Figure 3)

- Fuel supply system for wood chips boiler with back burn return protection diaphragm

- Automatic ash extraction system

- Automatic ignition with hot air blower

- WiFi modem + 4heat up App

- Automatic exchanger cleaning system

- Spring core agitator fuel feeding system

- Inertia tank

- Circulation Pump, Valves and pipes for boiler-inertia tank connection

- Flue gas duct

- Containerized woodchip fuel silo of 37.5 m3 fuel capacity

- Integrated Electrostatic Precipitator

2.2.2. Technical Information: Equipment Specifications for the Pelletech IDRO 500 Biomass Boiler

- Combines the advantages of a revolutionary multi-level reciprocating grate system that allows the combustion of biomass even with increased humidity up to 40%.

- Very high efficiency rate of up to 94.6% thanks to the triple flue gas path, integrated impellers, and fully controlled combustion conditions with independent dual air supply (primary and secondary).

- Fully automated operation with automatic ignition, cleaning cycles, and ash removal.

- Variable power according to the conditions of the space and the ability to memorize and select combustion parameters according to the type of fuel.

- Excellent combustion and proper fuel utilization without losses achieved through the use of a lambda sensor.

- Combustion chamber made of heavy-duty steel lined with refractory concrete for long life.

- Extremely low pollutant emissions, as shown in Table 3.

2.3. Methodological Approach to Biomass Boiler Unit Assessment in the Goudi Municipal Swimming Pool Area

Energy Production and Biomass Economic Considerations

-

Pieces wood from prunings of urban trees:

- Pieces originating from the tree trunk.

- Entire tree - pieces from all aboveground parts of the biomass of a tree

- Pieces of residues: From branches, bark, etc.

- Pieces of twigs

- Pieces from non-processed wood residues, recycled wood, and from the remains of pruning

- Pieces from cutting residues, from the leftovers of sawmills

- Thinnings from periodic forest thinning/cycle pruning of forest pieces from the respective energy crops.

2.4. Methodology for Energy Consumption

2.4.1. Biomass Fuel Mass Requirements Calculation

Energy Required from Biomass

Biomass Fuel Mass Calculation

Operational Expenditure (OPEX) Calculation for the Biomass System

Operational Expenditure (OPEX) Calculation for the Natural Gas System

Financial Metrics: NPV, IRR, and Payback Period

-

Net Present Value (NPV) is calculated by discounting future savings to the present value [29,33]:Where:St = Annual savings in year t,r = Discount rateI0 = Initial investmentN = Service life of the biomass system

-

Payback Period is the time required to recover the initial investment through annual savings [29]:Where:I0 = Initial capital investment,S0 = First-year savings = Annual Operating Cost of Natural Gas System−Annual Operating Cost of Biomass System

4. Results

4.1. Biomass Fuel Mass Requirements

4.2. Operational Expenditure (OPEX)

4.2.1. Operational Expenditure (OPEX) for the Biomass System

4.2.2. Operational Expenditure (OPEX) for the Natural Gas System

4.2.3. Comparison of Operational Expenditures

4.3. Financial Metrics Calculation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Legislative Frameworks and Waste Management Regulations

- Council Directive 1999/31/EC: Defines biodegradable waste as waste capable of undergoing aerobic or anaerobic decomposition, including garden and food waste, cardboard, and paper.

- Directive 2018/851 of the European Parliament and Council (May 30, 2018): Amends Directive 2008/98/EC on waste. It emphasizes waste management practices that enhance environmental protection, human health, and the sustainable use of resources, promoting the circular economy’s principles.

- Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste: Outlines a hierarchical approach to waste management, focusing on prevention, minimization, reuse, recycling, recovery, and disposal.

- Greek Government Gazette 2706/B΄/2015: Provides guidance for the creation of Operational Plans for Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) management, in alignment with Council Directive 1999/31/EC. These plans are integrated into the Regional Waste Management Plans.

- National Waste Management Plan (NWMP): Formulated under Articles 22 and 35 of Law 4042/2012, its main goal is the high-level protection of health and the environment. The plan was ratified by the Greek Government under Decision 49/15.12.2015 (Government Gazette 174A). The New National Waste Management Plan (ESDA 2020-2030) sets targets for source-separation of Green/Garden Waste, aiming for 50% by 2025 and 60% by 2030.

- European Waste Catalogue (EWC): As described in the Annex of Decision 2000/532/EC, amended by several decisions (2001/118/EC, 2001/119/EC, and 2001/573/EC), the EWC systematically classifies waste using specific codes for better management and compliance with European regulations.

| Classification of Plant Residues According to the European Waste Catalogue (EWC) | |

|---|---|

| EWC Code | Description and Origin of Waste |

| 02 01 07 | Waste from forestry |

| 20 01 38 | Wood waste other than those containing hazardous substances, falling under category 20 01 37 |

| 20 02 01 | Biodegradable waste from green areas, public parks, and private gardens |

| 20 02 02 | Soil and stones |

| 20 03 03 | Street-cleaning residues |

- 7.

- Ministerial Decision 198/2013: Published in the Greek Government Gazette B 2499/4-10-2013, this decision specifies the requirements for solid biomass fuels for non-industrial use, which must comply with ELOT standards EN 14961 and EN 15234.

- 8.

- Promotion of Recycling Bill: Incorporates Directives 2018/851 and 2018/852, modernizing landfill fees effective from January 1, 2021, with incremental increases per tonne of waste to discourage landfilling and achieve a landfill rate of less than 10% by 2030.

- 9.

- Law 5037/2023 (Article 79): Establishes sustainability criteria for biomass fuels used in energy production installations, requiring a nominal thermal capacity of at least 20 MW for solid biomass fuels and 2 MW for gaseous biomass fuels to meet environmental goals.

Appendix B: Total Number of Each Tree Species in the Municipality of Athens

| Municipal community | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Total |

| Ailanthus altissima | 103 | 151 | 634 | 587 | 94 | 96 | 155 | 1820 |

| Agave americana | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Acacia spp. | 39 | 39 | 12 | 66 | 14 | 9 | 52 | 231 |

| Albizia julibrissin | 10 | 23 | 82 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 23 | 158 |

| Vitis vinifera | 3 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 19 | |||

| Prunus dulcis | 1 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| Quercus ilex | 25 | 67 | 6 | 1 | 99 | |||

| Araucaria Araucana | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 9 | ||

| Quercus spp. | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Brachychiton acerifolius | 443 | 138 | 747 | 170 | 200 | 64 | 386 | 2148 |

| Broussonetia papyrifera | 2 | 1 | 6 | 9 | ||||

| Acacia farnesiana | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |||

| Jacaranda sp. | 173 | 80 | 23 | 9 | 19 | 54 | 21 | 379 |

| Yucca spp. | 24 | 25 | 73 | 14 | 9 | 15 | 30 | 190 |

| Gleditschia tricanthos | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 16 | ||

| Grevillea robusta | 8 | 2 | 39 | 2 | 6 | 57 | ||

| Laurus nobilis | 117 | 14 | 70 | 25 | 8 | 39 | 19 | 292 |

| Olea europaea | 352 | 1627 | 783 | 406 | 1087 | 321 | 1590 | 6166 |

| Eucalyptus sp. | 20 | 28 | 47 | 45 | 59 | 15 | 22 | 236 |

| Euonymus spp. | 7 | 7 | ||||||

| Hibiscus syriacus | 649 | 942 | 316 | 103 | 279 | 69 | 312 | 2670 |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Casuarina spp. | 134 | 2 | 39 | 64 | 16 | 45 | 300 | |

| Camellia spp. | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||||

| Juglans regia | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Cedrus spp. | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| Koelreuteria paniculata | 235 | 54 | 33 | 390 | 121 | 60 | 157 | 1050 |

| Pinus pinea | 35 | 11 | 4 | 50 | ||||

| Cercis siliquastrum | 268 | 140 | 291 | 138 | 123 | 113 | 523 | 1596 |

| Cotoneaster spp. | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Cupressus sp. | 27 | 132 | 131 | 34 | 43 | 33 | 109 | 509 |

| Populus spp. | 94 | 59 | 21 | 57 | 71 | 71 | 159 | 532 |

| Populus alba | 39 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 29 | 93 |

| Populus nigra | 1 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 12 | |||

| Populus x canadensis | 1 | 3 | 14 | 18 | ||||

| Ligustrum sp. | 878 | 391 | 270 | 400 | 761 | 996 | 390 | 4086 |

| Vitex agnus-castus | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Magnolia spp. | 5 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 23 | |||

| Melia azedarach | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 10 | |||

| Morus sp. | 2788 | 2407 | 1042 | 1316 | 3743 | 1808 | 3808 | 16912 |

| Eriobotrya japonica | 11 | 7 | 27 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 66 | |

| Bougainvillea spp. | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Citrus aurantium | 3027 | 3081 | 2317 | 2126 | 3001 | 1876 | 4338 | 19766 |

| Washigtonia filifera | 4 | 32 | 86 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 151 |

| Parkinsonia aculeata | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Syringa vulgaris | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Pinus spp. | 47 | 64 | 27 | 65 | 808 | 9 | 165 | 1185 |

| Pinus sylvestris | 18 | 36 | 4 | 19 | 77 | |||

| Pinus nigra | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Pinus halepensis | 5 | 26 | 32 | 1 | 30 | 31 | 125 | |

| Nerium oleander | 242 | 323 | 325 | 152 | 328 | 303 | 319 | 1992 |

| Platanus spp. | 61 | 95 | 53 | 9 | 11 | 100 | 329 | |

| Platanus orientalis | 100 | 129 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 33 | 267 | |

| Platanus occidentalis | 8 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 15 | 38 | ||

| Prunus cerasifera | 63 | 16 | 48 | 6 | 19 | 22 | 103 | 277 |

| Buxus spp. | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Pyracantha spp. | 8 | 35 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 66 | ||

| Rhamnus spp. | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Pseudoacacia robinia | 252 | 360 | 117 | 366 | 110 | 161 | 140 | 1506 |

| Punica granatum | 4 | 20 | 2 | 7 | 33 | |||

| Sophora japonica | 3091 | 2632 | 1270 | 1384 | 2118 | 3234 | 2094 | 15823 |

| Ficus carica | 8 | 6 | 19 | 14 | 6 | 13 | 17 | 83 |

| Acer negundo | 264 | 370 | 172 | 124 | 283 | 153 | 13 | 1379 |

| Pistacia lentiscus | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Ficus spp. | 11 | 14 | 31 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 75 |

| Phoenix spp. | 8 | 14 | 47 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 98 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Ulmus sp. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 23 | 29 | ||

| Photinia spp. | 2 | 11 | 2 | 15 | ||||

| Chamaerops humilis | 9 | 2 | 1 | 12 | ||||

| Ceratonia siliqua | 31 | 75 | 39 | 50 | 25 | 161 | 77 | 458 |

| Ptaeroxylon obliquum | 8 | 55 | 43 | 18 | 29 | 40 | 39 | 232 |

| Schinus molle | 37 | 44 | 38 | 4 | 15 | 3 | 141 | |

References

- Y. Li, L. W. Zhou, and R. Z. Wang, “Urban biomass and methods of estimating municipal biomass resources,” 2017, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directive 2008/98/EC on waste (Waste Framework Directive). 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- S. Kumar, J. K. Bhattacharyya, A. N. Vaidya, T. Chakrabarti, S. Devotta, and A. B. Akolkar, “Assessment of the status of municipal solid waste management in metro cities, state capitals, class I cities, and class II towns in India: An insight,” Waste Management, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 883–895, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- G. Tchobanoglous, “Handbook of Solid Waste Management,” Springer eBooks, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- European Union, Directive (EU) 2018/851 on Waste Management. 2018.

- R. Day, G. Walker, and N. Simcock, “Conceptualising energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework,” Energy Policy, vol. 93, pp. 255–264, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Banja M, Monforti-Ferrario F, Bódis K, Jäger-Waldau A, and Taylor N, “Renewable energy deployment in the European Union,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jäger-Waldau, “Snapshot of photovoltaics-March 2017,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 9, no. 5, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Sjödin and D. Henning, “Calculating the marginal costs of a district-heating utility,” Appl Energy, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 1–18, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Pedersen, “Task 32 Biomass Combustion Final Task Report,” 2019.

- Municipal District Heating Company of Amindeo (D.H.C.A.) – ΔΕΤΕΠA. Available online: https://detepa.gr/dhca/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Pelletech, “Small scale remote heating,” 2023.

- “Biomass boiler in a primary school, Lehovo Greece.”. Available online: https://detepa.gr/2016/12/08/%CE%B5%CE%BA%CE%BA%CE%AF%CE%BD%CE%B7%CF%83%CE%B7-%CE%BB%CE%B5%CE%B9%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%85%CF%81%CE%B3%CE%AF%CE%B1%CF%82-%CE%BC%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AC%CE%B4%CE%B1%CF%82-%CE%BA%CE%B1%CF%8D%CF%83%CE%B5%CF%89/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Samoukatsidis Bros. G.P. and Camino Design, “Biomass boilers - energy fireplaces - foundries,” 2021. Available online: www.pelletech.gr.

- K. G. Aravossis, A. Mitsikas, and K. Aravossis, A techno economic assessment of waste management scenarios in Attica-Greece. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326958310.

- Climatic Data by City - METEOGRAMS, Hellenic National Meteorological Service (HNMS). Available online: http://www.emy.gr/emy/el/climatology/climatology_city (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) and Municipality of Athens, “Investigation of the optimal integrated biowaste management system in the Municipality of Athens with the aim of their utilization,” Jul. 2017.

- ΕΜAΚ. Available online: https://www.fisikolipasma.gr/emak (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Municipality of Athens, “Part I of the Climate Action Plan,” 2022.

- F. Meisel and N. Thiele, “Where to dispose of urban green waste? Transportation planning for the maintenance of public green spaces,” Transp Res Part A Policy Pract, vol. 64, pp. 147–162, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi, Y. Ge, J. Chang, H. Shao, and Y. Tang, “Garden waste biomass for renewable and sustainable energy production in China: Potential, challenges and development,” 2013, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Pelletech. Available online: https://newsite.pelletech.gr/product/ecd63403b5c3dtnjwoib/Biomass/Woodchips%20integrated%20hot%20water%20production%20system%20IDRO%20150-500/eca9wj00/eca6ajrq# (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2015/ 1189 - of 28 April 2015 - implementing Directive 2009/ 125/ EC of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to ecodesign requirements for solid fuel boilers. 2015.

- BS EN 303-5:2021+A1:2022 | 30 Nov 2023 | BSI Knowledge. Available online: https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/heating-boilers-heating-boilers-for-solid-fuels-manually-and-automatically-stoked-nominal-heat-output-of-up-to-500-kw-terminology-requirements-testing-and-marking-2?version=standard (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- R. Saidur, E. A. Abdelaziz, A. Demirbas, M. S. Hossain, and S. Mekhilef, “A review on biomass as a fuel for boilers,” Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- B. Velázquez-Martí, M. Sajdak, I. López-Cortés, and A. J. Callejón-Ferre, “Wood characterization for energy application proceeding from pruning Morus alba L., Platanus hispanica Münchh. and Sophora japonica L. in urban areas,” Renew Energy, vol. 62, pp. 478–483, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Development of a biowaste collection and management network in the Municipality of Athens, MIS 5053881, OPS Call 3658. Available online: https://www.ymeperaa.gr/erga/perivallon/entakseis-ypodomes/aksonas-14/diaxeirisi-evd-ep-ymeperaa/1139-anaptyksi-diktyou-syllogis-kai-diaxeirisis-vioapovliton-sto-dimo-athinaion-mis-5053881-ops-prosklisis-3658 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ministry of Development | Central website of the Ministry of Development. Available online: https://www.mindev.gov.gr/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- R. A. Brealey, S. C. Myers, Franklin. Allen, and Alex. Edmans, Principles of corporate finance, 14th Ediition. McGraw Hill, 2023.

- S. Van Loo and J. Koppejan, The Handbook of Biomass Combustion and Cofiring. London: earthscan, 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237079687.

- T. Gregory. Hicks, Standard handbook of engineering calculations. Tyler G. Hicks, editor. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1972.

- K. Braimakis, A. Charalampidis, and S. Karellas, “Techno-economic assessment of a small-scale biomass ORC-CHP for district heating,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 247, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. A. . Ross, Randolph. Westerfield, J. F. . Jaffe, B. D. . Jordan, and Kelly. Shue, Corporate finance, 13thEdition ed. McGraw Hill LLC, 2022.

- E. F. Brigham and M. C. Ehrhardt, Financial Management: Theory and Practice. Thomson South-Western, 2021.

- Natural Gas Greek energy company. Available online: https://www.fysikoaerioellados.gr/commodity/ti-einai-to-fysiko-aerio/#section-4 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- ECB interest rates. Available online: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/statistics/financial-markets-and-interest-rates/ecb-interest-rates (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- HELLENIC REPUBLIC HELLENIC STATISTICAL AUTHORITY, “CONSUMER PRICE INDEX: August, annual inflation 3.0%,” Sep. 2024.

- M. Hiloidhari, M. A. Sharno, D. C. Baruah, and A. N. Bezbaruah, “Green and sustainable biomass supply chain for environmental, social and economic benefits,” Biomass Bioenergy, vol. 175, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 final. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- R. Figueiredo, M. Soliman, A. N. Al-Alawi, and M. J. Sousa, “The Impacts of Geopolitical Risks on the Energy Sector: Micro-Level Operative Analysis in the European Union,” Economies, vol. 10, no. 12, Dec. 202. [CrossRef]

- Z. Vazifeh, F. Mafakheri, and C. An, “Biomass supply chain coordination for remote communities: A game-theoretic modeling and analysis approach,” Sustain Cities Soc, vol. 69, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Du, J. Calautit, P. Eames, and Y. Wu, “A state-of-the-art review of the application of phase change materials (PCM) in Mobilized-Thermal Energy Storage (M-TES) for recovering low-temperature industrial waste heat (IWH) for distributed heat supply,” May 01, 2021, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- S. Guo et al., “Mobilized thermal energy storage: Materials, containers and economic evaluation,” Dec. 01, 2018, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

| Systems for the Management of Biowaste and Plant Residues | ||

| System | Description | Characteristics |

| Landfill Sites (ΧΥΤA) | Disposal of waste in designated sites, either legally or illegally | Possibility of biogas recovery |

| Aerobic Biological Treatment - Composting | Composting systems, which can be centralized, open, or closed type | Includes household composting |

| Anaerobic Digestion | Biological process for the pre-treatment and post-treatment of organic load | Anaerobic biological treatment |

| Aerobic Biodrying | Process to remove moisture from plant residues, reducing volume and generating bio-thermal energy | Moisture removal, volume reduction, bio-thermal energy development |

| Gasification | Thermal process for the treatment of garden waste | Thermal processing primarily for garden waste |

| Incineration | Process that involves burning waste | Effectiveness depends on thermal or energy recovery |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Conductivity | 1.97±1.25 | mS cm⁻¹ |

| Total Solids (TS) | 63.59±6.25 | % w.w. |

| Volatile Solids (VS) | 78.62±9.52 | % TS |

| pH | 6.20±0.36 | - |

| Moisture | 36.51±6.25 | % w.w. |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | 48.33±5.36 | % TS |

| Total Nitrogen (TN) | 1.01±0.22 | % TS |

| Density | 0.19±0.05 | gr cm⁻³ w.w. |

| Organic Nitrogen (Norg) | 0.94±0.24 | % TS |

| Nitrate Nitrogen (NO₃-N) | 0.00±0.00 | % TS |

| Ammoniacal Nitrogen (NH₄-N) | 0.02±0.03 | % TS |

| Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio (TOC/TN) | 52.48±18.03 | - |

| PelleTech Idro 500 emission and efficiency test report | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Values | Directive Requirements |

| Rated nominal output | 499 kW | |

| Partial load output (30%) | 149 kW | |

| CO at 10% O2 | 33 mg/Nm3 | 500 mg/Nm3 |

| OGC at 10% O2 | <1 mg/Nm3 | |

| Dust at 10% O2 | 11 mg/Nm3 | 40 mg/Nm3 |

| NOx at 10% O2 | 162 mg/Nm3 | 200 mg/Nm3 |

| Efficiency (NCV) | 94.6 % | 88% |

| Partial load Efficiency | 92.5 % | |

| Useful Efficiency (CGV) | 84.7 % | |

| Seasonal space heating energy efficiency | 81% | |

| PelleTech Idro 500 equipment, installation and annual maintenance costs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| References | Components | Costs € | Operating maintenance costs € |

| PelleTech offer | Containerized biomass boilers PelleTech Idro 500 | 330,000.00 | 7,700.00 |

| Mulberry and Sophora Japonica) | |

|---|---|

| Parameters | Values |

| Mulberry | 17,127.62 kJ kg -1 |

| Sophora Japonica | 17,970.49 kJ kg -1 |

| Average woodchip fuel GCV | 17,549.05 kJ kg -1 |

| Calculation of woodchip fuel cost | |

|---|---|

| Parameters | Values |

| Shredding process | 45€/t |

| Boiler refueling costs | 1.37€/t |

| Total | 46.37€/t |

| Swimming pool annual thermal energy consumption and cost for year 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Thermal Energy consumption kWhth | Thermal Energy consumption MWhth | Natural Gas Monthly Cost € |

Natural Gas Price per Mwh [€/MWh] |

| Jan 2021 | 476,247.36 | 476.25 | 23,619.17 | 49.59 |

| Feb 2021 | 376,690.63 | 376.69 | 20,133.72 | 53.45 |

| Mar 2021 | 386,073.18 | 386.07 | 19,421.85 | 50.31 |

| Apr 2021 | 239,453.34 | 239.45 | 12,240.57 | 51.12 |

| May 2021 | 61,183.21 | 61.18 | 3,309.81 | 54.10 |

| Jun 2021 | 23,428.71 | 23.43 | 1,453.08 | 62.02 |

| Jul 2021 | 21,177.80 | 21.18 | 1,435.79 | 67.80 |

| Aug 2021 | 17,792.28 | 17.79 | 1,354.93 | 76.15 |

| Sep 2021 | 121,807.12 | 121.81 | 9,678.34 | 79.46 |

| Oct 2021 | 333,984.64 | 333.98 | 34,345.31 | 102.83 |

| Nov 2021 | 401,502.10 | 401.50 | 51,787.05 | 128.98 |

| Dec 2021 | 548,280.43 | 548.28 | 67,707.24 | 123.49 |

| Total | 3,007,620.28 | 3,000.62 | 246,486.86 | |

| Swimming pool annual thermal energy consumption and cost for year 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Thermal Energy consumption kWhth | Thermal Energy consumption MWhth | Natural Gas Monthly Cost € |

Natural Gas Price per Mwh [€/MWh] |

| Jan 2022 | 561,024.61 | 561.02 | 68,108.43 | 121.40 |

| Feb 2022 | 551,020.31 | 551.02 | 65,108.43 | 118.16 |

| Mar 2022 | 523,784.70 | 523.78 | 49,994.83 | 95.45 |

| Apr 2022 | 264,574.71 | 264.57 | 33,982.36 | 128.44 |

| May 2022 | 139,380.15 | 139.38 | 16,640.34 | 119.39 |

| Jun 2022 | 38,136.85 | 38.13 | 4,258.61 | 111.67 |

| Jul 2022 | 37,604.16 | 37.60 | 4,466.42 | 118.77 |

| Aug 2022 | 32,031.55 | 32.03 | 5,746.04 | 179.39 |

| Sep 2022 | 75,198.83 | 75.19 | 18,047.82 | 240.00 |

| Oct 2022 | 313,913.34 | 313.91 | 53,475.48 | 170.35 |

| Nov 2022 | 427,320.82 | 427.32 | 60,525.57 | 141.64 |

| Dec 2022 | 475,751.41 | 475.75 | 69,608.74 | 146.31 |

| Total | 3,439,741.44 | 3,439.74 | 449,963.07 | |

| Swimming pool annual thermal energy consumption and cost for year 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Thermal Energy consumption kWhth | Thermal Energy consumption MWhth | Natural Gas Monthly Cost € |

Natural Gas Price per Mwh [€/MWh] |

| Jan 2023 | 561,854.05 | 561.85 | 87,441.81 | 155.63 |

| Feb 2023 | 540,608.22 | 540.60 | 56,742.86 | 104.96 |

| Mar 2023 | 462,621.16 | 462.62 | 43,812.04 | 94.70 |

| Apr 2023 | 401,036.06 | 401.03 | 33,803.11 | 84.29 |

| May 2023 | 286,359.61 | 286.35 | 23,007.55 | 80.34 |

| Jun 2023 | 86,367.32 | 86.36 | 6,054.39 | 70.10 |

| Jul 2023 | 34,798.03 | 34.79 | 2,437.07 | 70.30 |

| Aug 2023 | 45,111.18 | 45.11 | 3,052.57 | 67.67 |

| Sep 2023 | 131,398.66 | 131.39 | 6,568.17 | 49.99 |

| Oct 2023 | 207,614.35 | 207.61 | 15,322.32 | 73.80 |

| Nov 2023 | 301,976.88 | 301.97 | 25,048.82 | 82.95 |

| Dec 2023 | 479,750.05 | 479.75 | 39,943.26 | 83.26 |

| Total | 3,539,495.57 | 3,539.49 | 343,233.97 | |

| Swimming pool average annual thermal energy consumption for 2021 – 2023 period | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Thermal Energy consumption kWhth | Thermal Energy consumption MWhth | Annual Cost of Natural Gas € |

| 2021 | 3,007,620.28 | 3,000.62 | 246,486.86 |

| 2022 | 3,439,741.44 | 3,439.74 | 449,963.07 |

| 2023 | 3,539,495.57 | 3,539.49 | 343,233.97 |

| Average | 3,328,952.60 | 3,328.95 | 346,561.30 |

| Operational expenditure for natural gas heating system and average natural gas price of period 2021-2023 | |

|---|---|

| Parameters | Value € |

| Annual natural gas Fuel cost (Table 10) | 346,561.30 |

| Boiler Annual Maintenance Costs (market research) | 1,500.00 |

| Total | 348,061.30 |

| Operational expenditure for natural gas heating system and natural gas price of April 2024 | |

|---|---|

| Parameters | Value € |

| Annual natural gas Fuel cost (Eq. 14) | 203,332.42 |

| Boiler Annual Maintenance Costs (market research) | 1,500.00 |

| Total | 204,832.42 |

| Woodchip fuel cost for the production of the average annual thermal energy requirements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Unit | Value | |

| Capital investment | € | 330.000,00 | [Table 4] |

| Equity financing of Biomass project | % | 100 | |

| Equipment service life (Ν) | years | 15 | |

| Discount rate (r) | % | 3,65 | [36] |

| Consumer price index (CPI) | €/t | 3.0 | [37] |

| Description | Total investment cost (€) |

Operation Expenditure (OPEX) (€) |

Annual operating cost reduction (€) |

Percentage of operating cost reduction (%) |

Net present value (NPV) (€) |

Internal rate of return (IRR) (%) | Payback period (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing system average natural gas prices 2021-2023 |

– | 348,061.30 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Existing system Current natural gas prices (April 2024) |

– | 204,832.42 | 143,228.88 | 41.15 | – | – | – |

| Biomass System compared to average natural gas prices 2021-2023 | 330,000.00 | 46,789.91 | 301,271.39 | 86.55 | 3,843,646.60 | 94.29 | 1.10 |

| Biomass System compared to April 2024 natural gas prices | 330,000.00 | 46,789.91 | 158,042.51 | 77.15 | 1,859,433.20 | 50.73 | 2.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).